Exploring the Links Between Clean Energies and Community Actions in Remote Areas: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

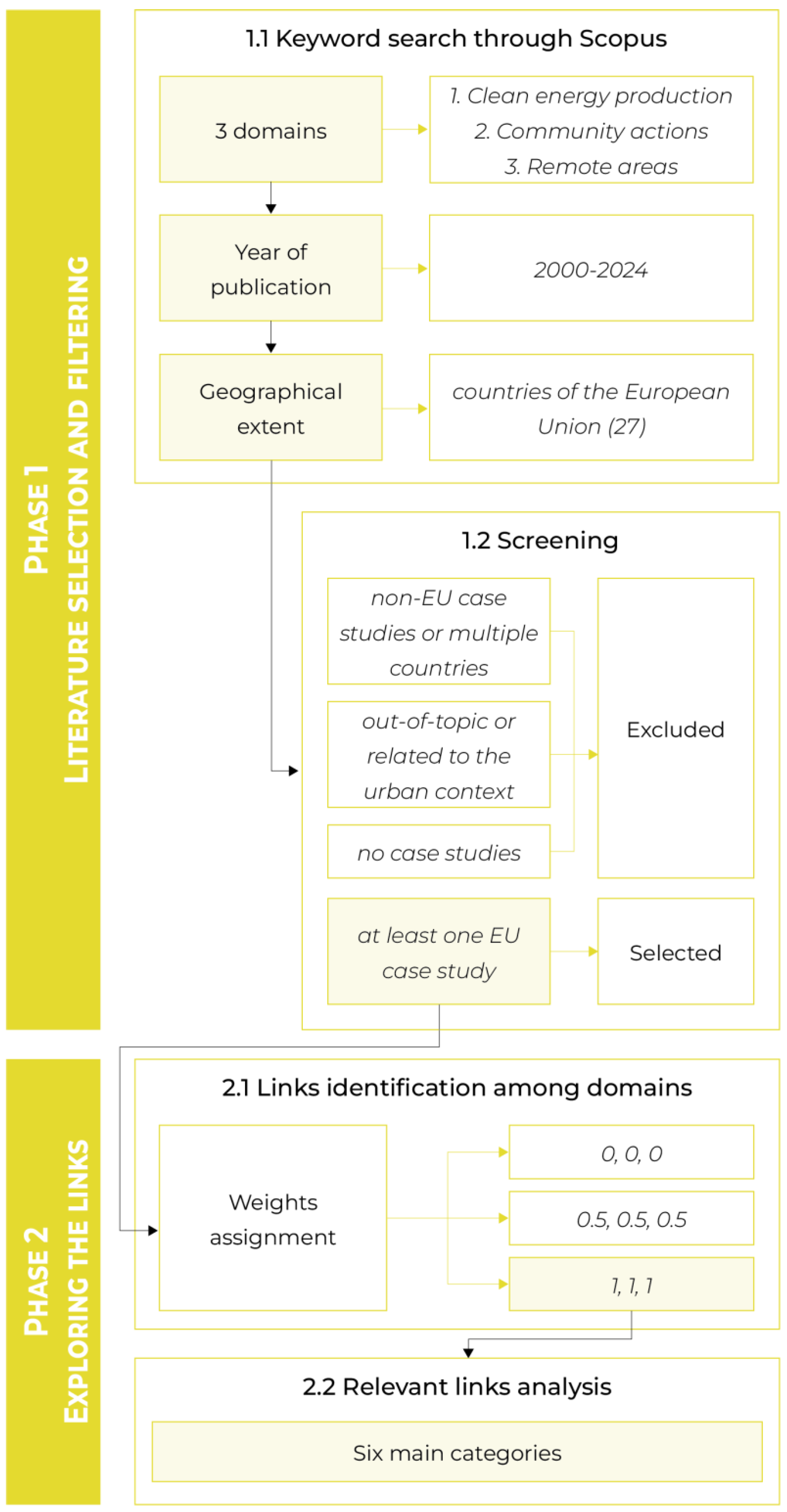

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Selection and Filtering

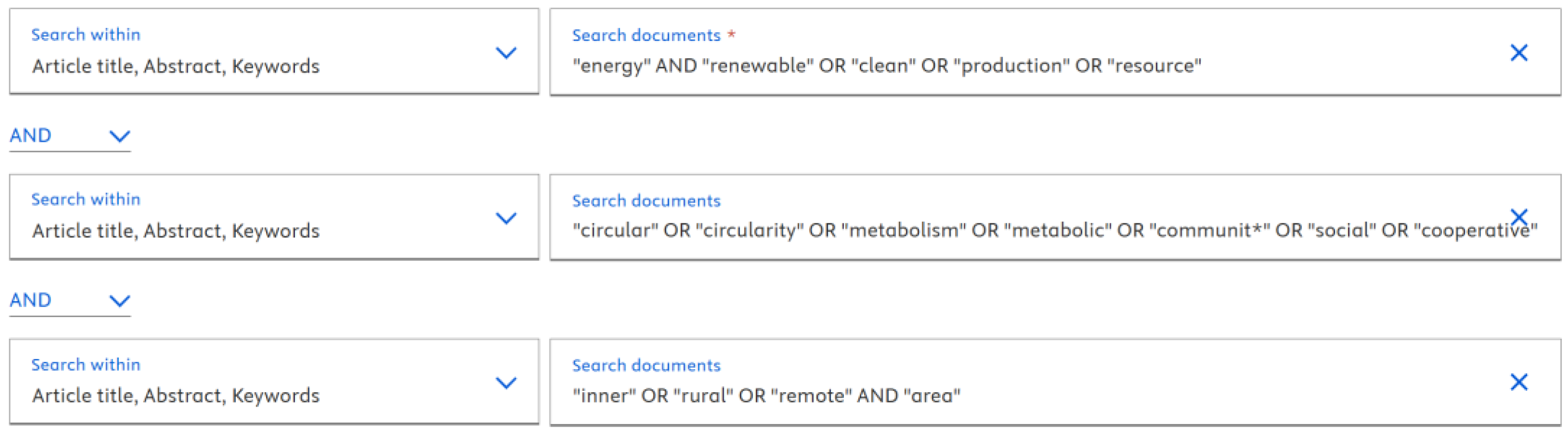

2.1.1. Keyword Search Through Scopus

2.1.2. Screening

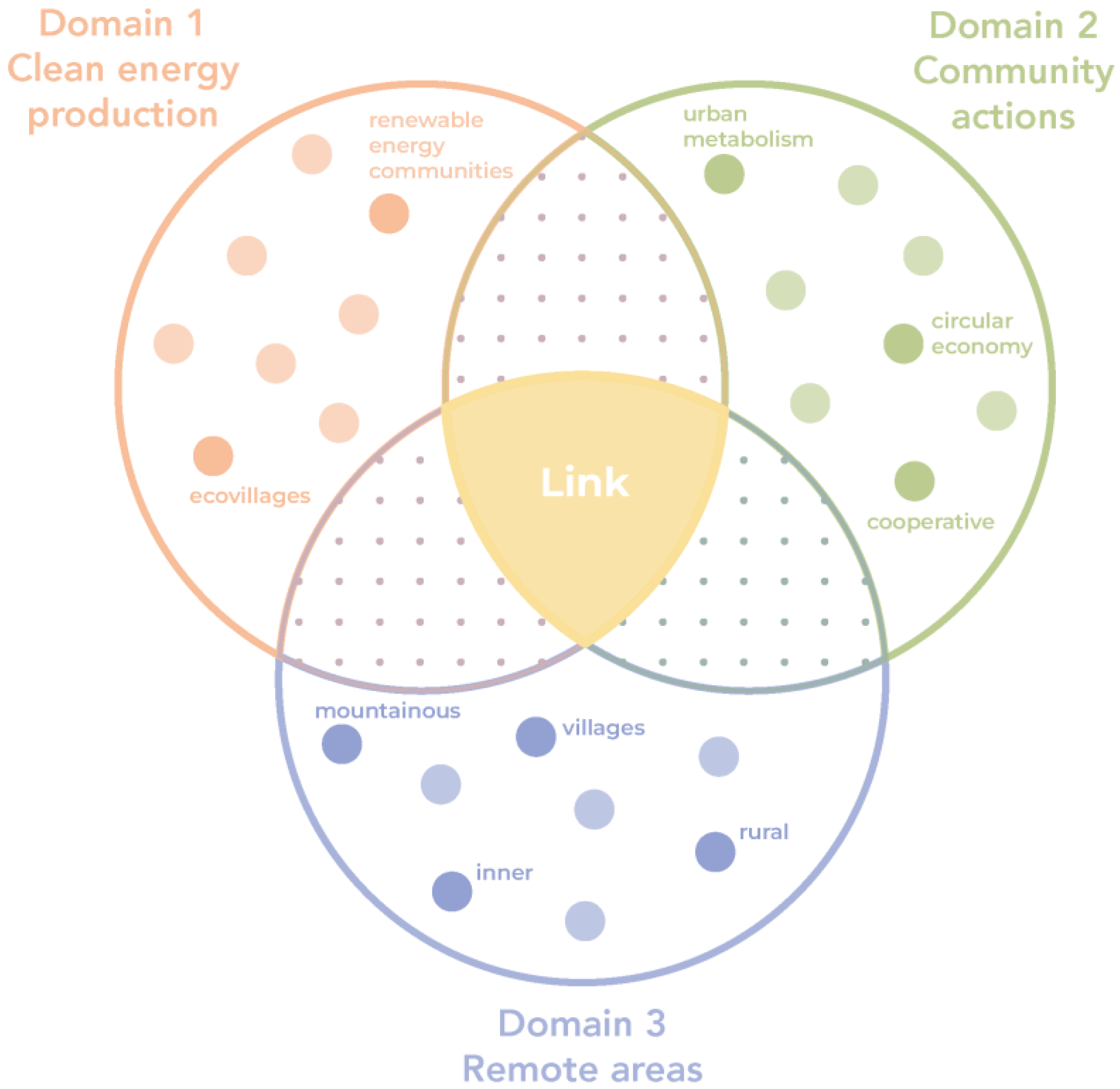

2.2. Exploring the Links

2.2.1. Links Identification Among Domains

2.2.2. Relevant Links Analysis

3. Results

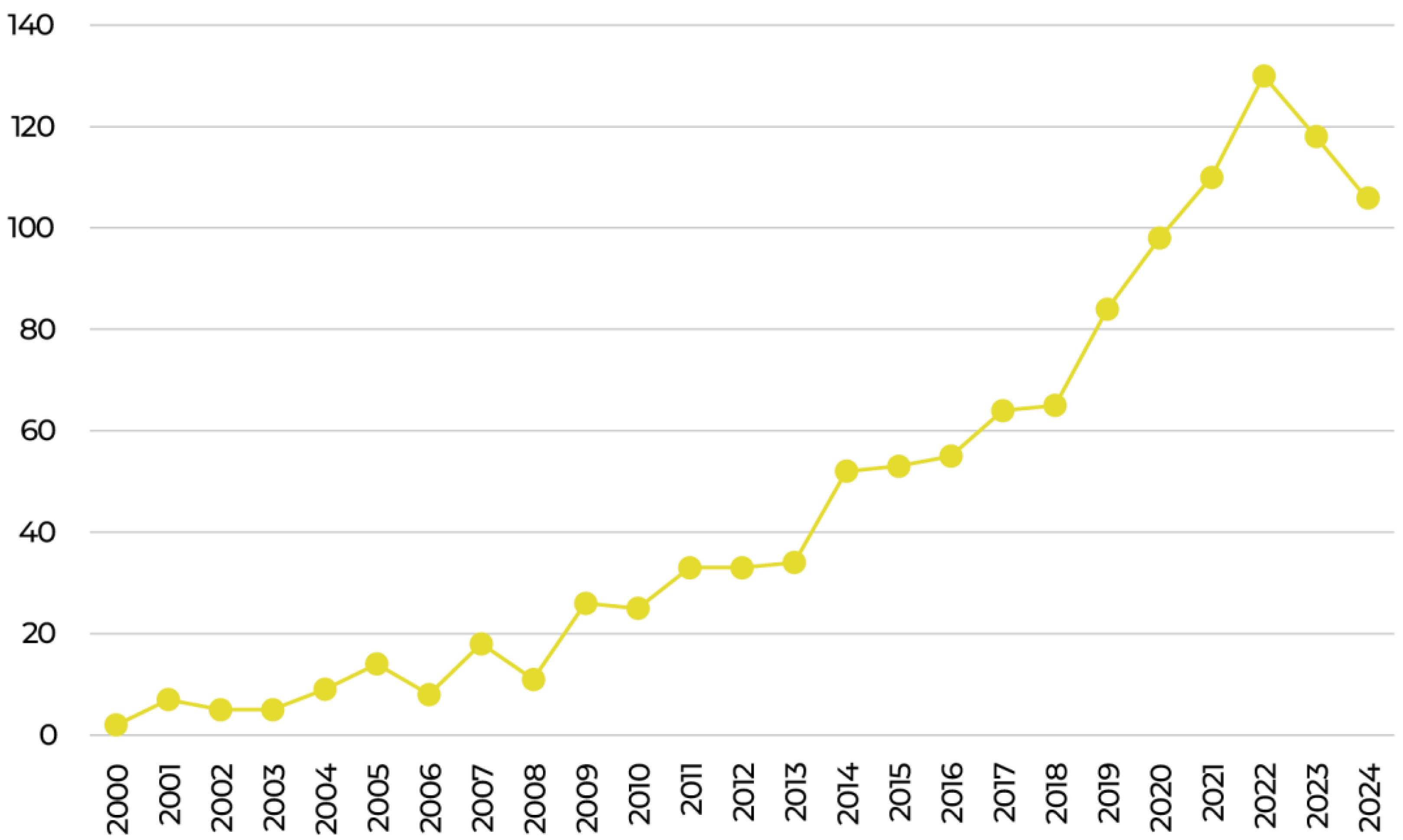

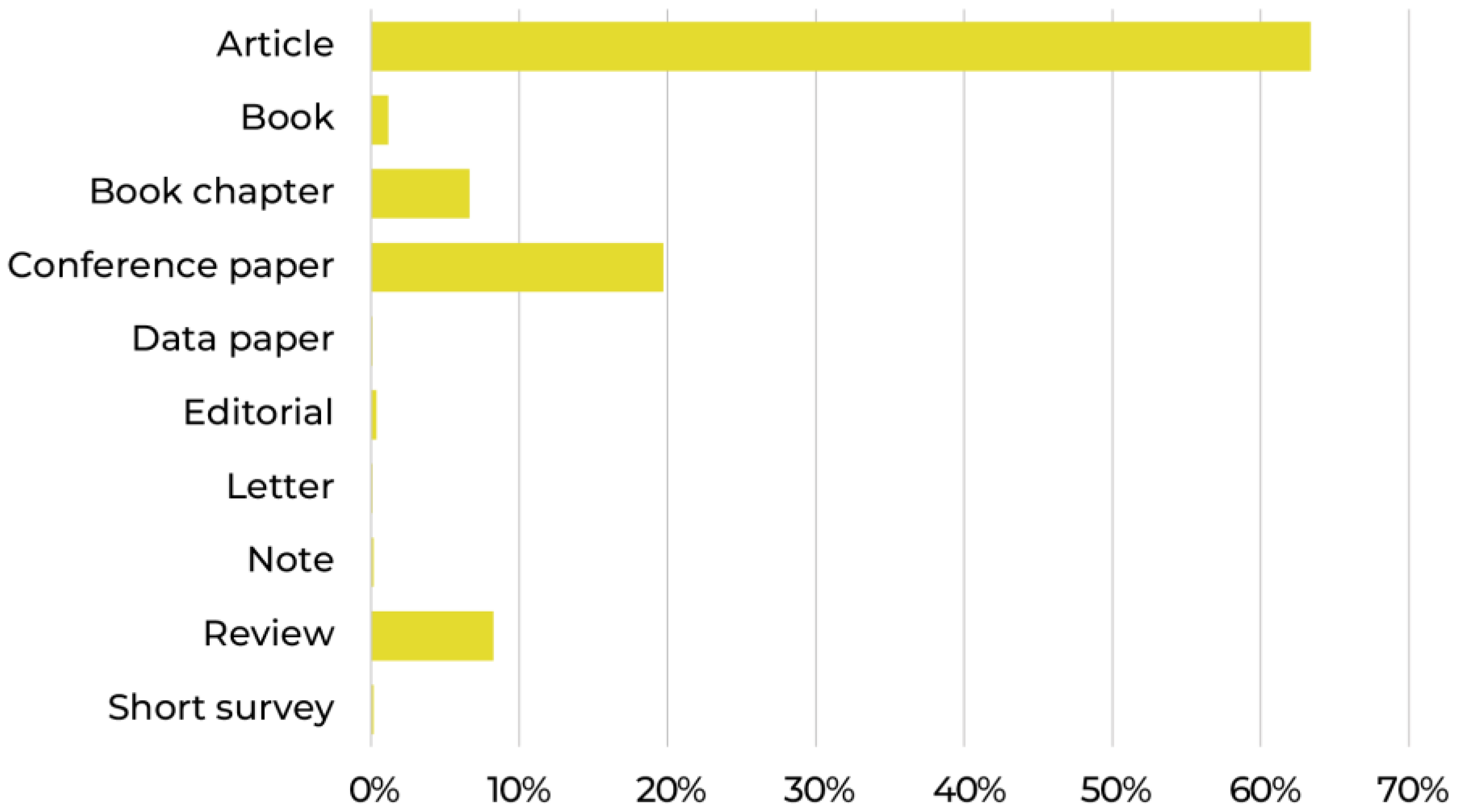

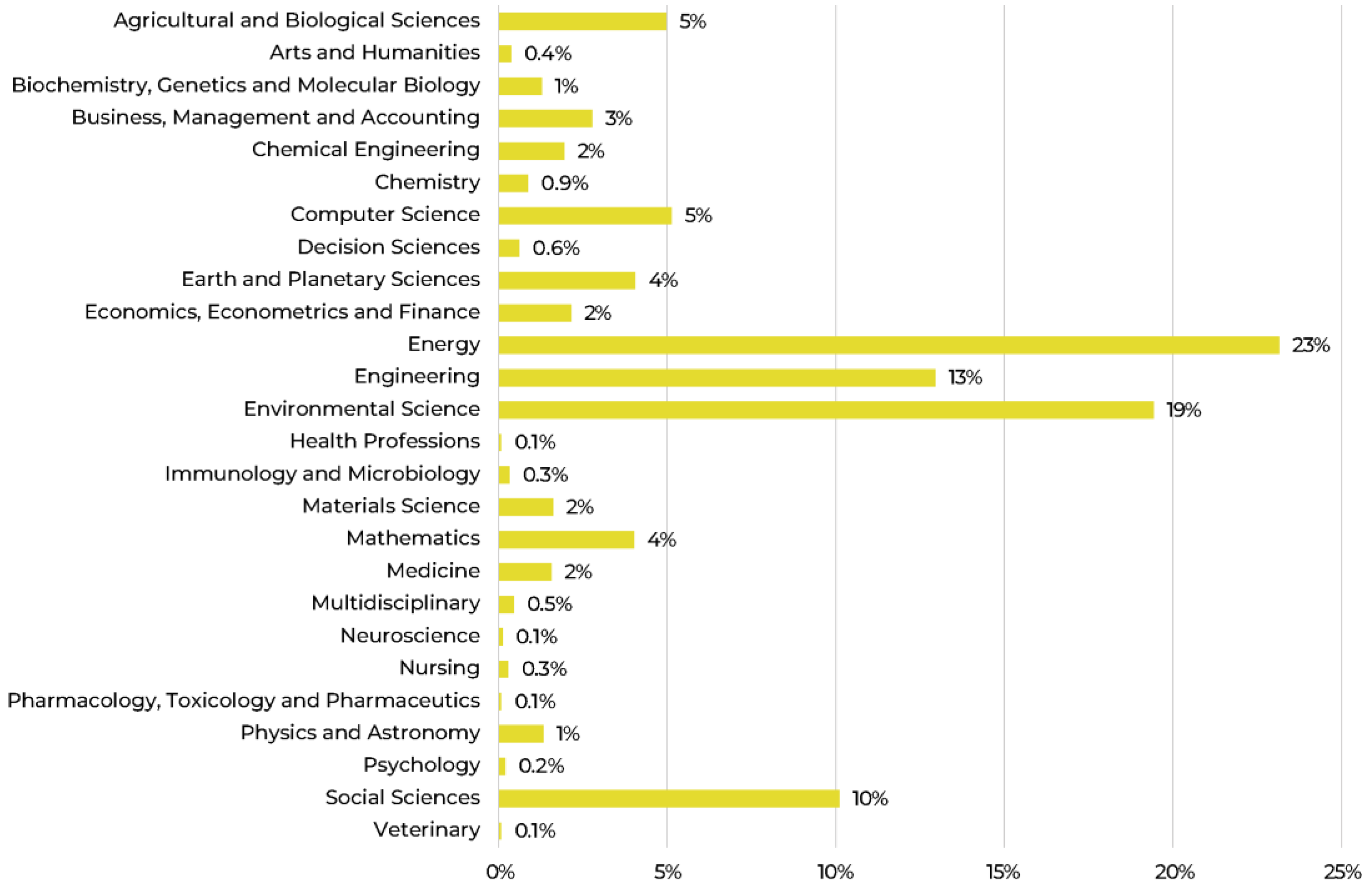

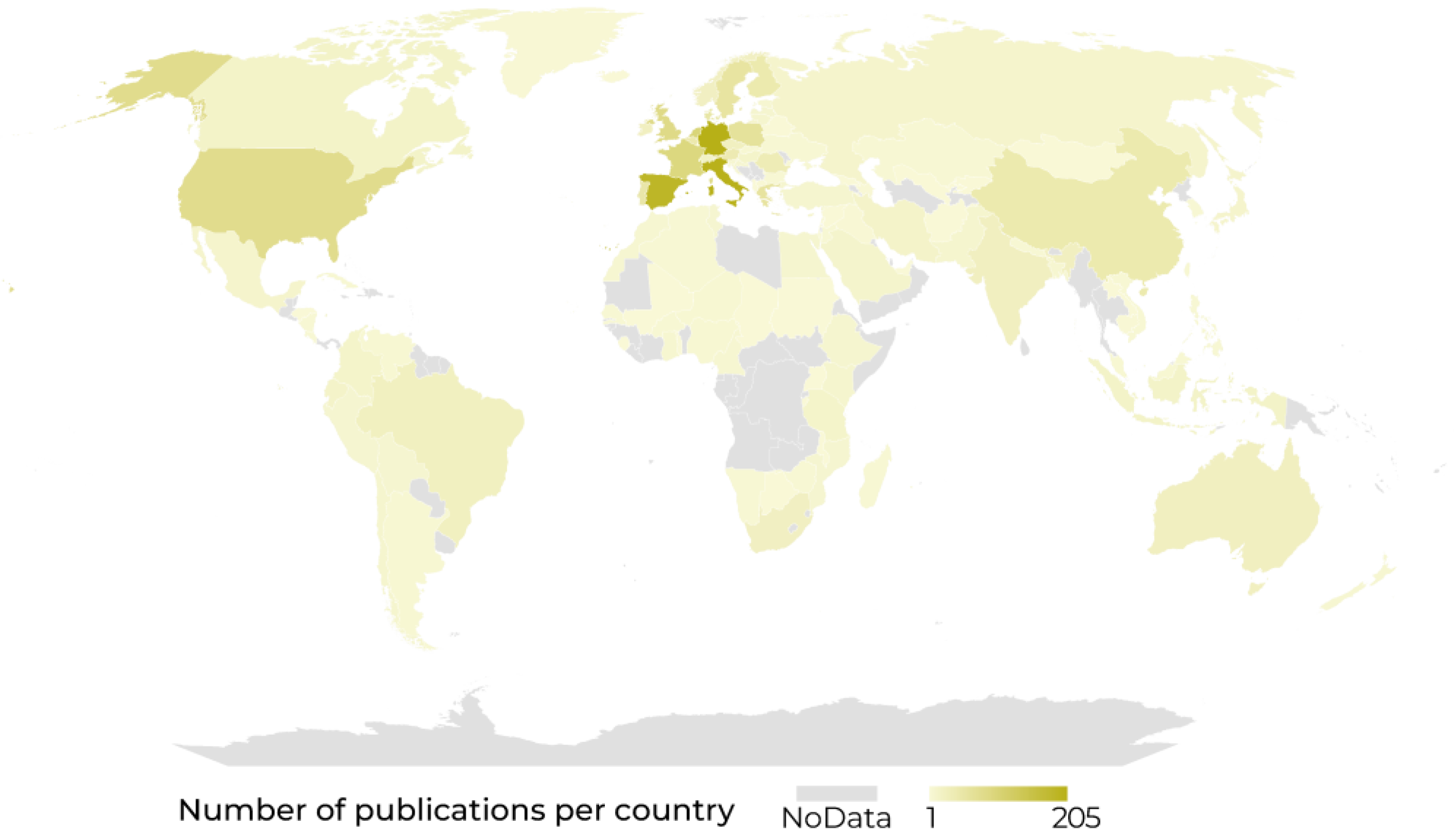

3.1. Overview of Selected and Filtered Literature

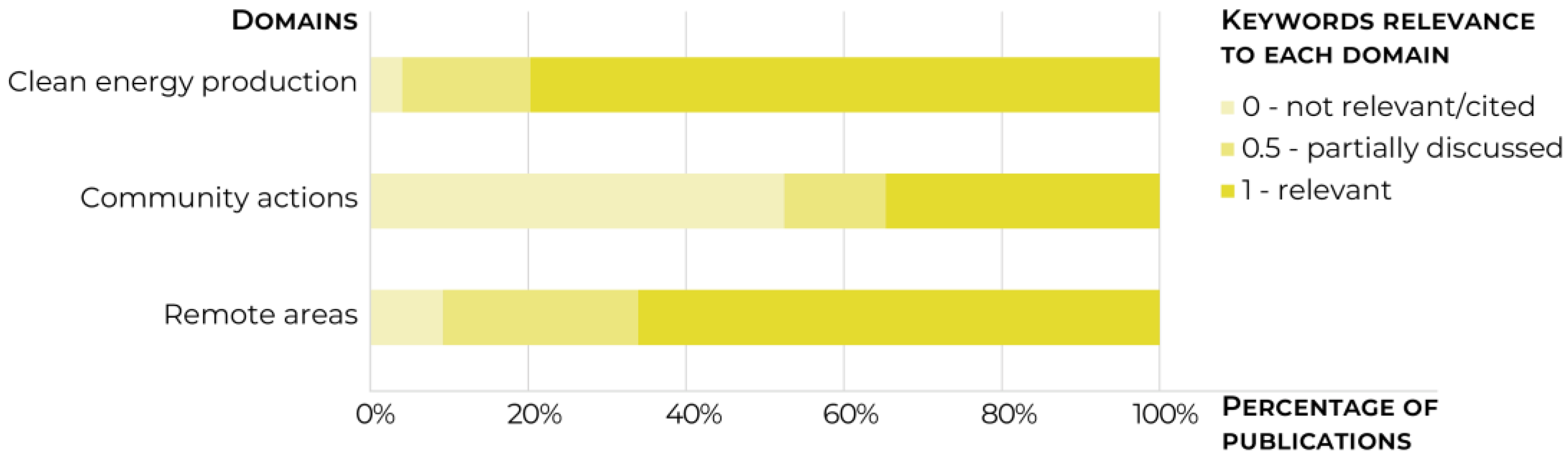

3.2. Links Identification

3.3. Insights from Relevant Links

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Willand, N.; Middlemiss, L.; Büchs, M.; Albala, P.A. Understanding essential energy through functionings: A comparative study across six energy poverty trials in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 118, 103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Inability to Keep Home Adequately Warm. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ilc_mdes01/default/table?lang=en). (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Koukoufikis, G.; Ozdemir, E.; Uihlein, A. Energy Poverty in the EU—2024 Status Quo; European Commission: Petten, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ACER. ACER’s Preliminary Assessment of Europe’s High Energy Prices and the Current Wholesale Electricity Market Design; ACER: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barrella, R.; Mora Rosado, S.; Romero, J.C. The 2022 energy and inflationary crises: Data, experiences and opinions of Spanish energy vulnerable households. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 121, 103961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F. Implications of poorly designed climate policy on energy poverty: Global reflections on the current surge in energy prices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 92, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemiss, L.; Stevens, M.; Ambrosio-Albalá, P.; Pellicer-Sifres, V.; van Grieken, A. How do interventions for energy poverty and health work? Energy Policy 2023, 180, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Thomson, H.; Cornelis, M.; Varo, A.; Guyet, R. Towards an Inclusive Energy Transition in the European Union: Confronting Energy Poverty Amidst a Global Crisis; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Thomson, H. Energy Vulnerability in the Grain of the City: Toward Neighborhood Typologies of Material Deprivation. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 695–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Rebelatto, B.G.; Salvia, A.L.; Rampasso, I.S.; Gatto, A.; Barrioz, V.; Aina, Y.A.; Hunt, J.D.; Anholon, R.; Ribeiro, P.C.C.; et al. Addressing energy poverty: Regional trends and examples of best practice. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 85, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Cheikh, N.; Ben Zaied, Y.; Nguyen, D.K. Understanding energy poverty drivers in Europe. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lloyd, B.; Liang, X.-J.; Wei, Y.-M. Energy poor or fuel poor: What are the differences? Energy Policy 2014, 68, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, E.; Barnes, A.; Power, M. Predictors of fuel poverty and the equity of local fuel poverty support: Secondary analysis of data from Bradford, England. Perspect. Public Health 2024, 144, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulucak, R.; Sari, R.; Erdogan, S.; Alexandre Castanho, R. Bibliometric Literature Analysis of a Multi-Dimensional Sustainable Development Issue: Energy Poverty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyprianou, I.; Serghides, D.K.; Varo, A.; Gouveia, J.P.; Kopeva, D.; Murauskaite, L. Energy poverty policies and measures in 5 EU countries: A comparative study. Energy Build. 2019, 196, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H.; Snell, C.; Bouzarovski, S. Health, Well-Being and Energy Poverty in Europe: A Comparative Study of 32 European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldron, R.; Sugrue, S.; Simcock, N.; Holloway, L. Precarious lives: Exploring the intersection of insecure housing and energy conditions in Ireland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 121, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiella, I.; Lavecchia, L. Energy poverty. How can you fight it, if you can’t measure it? Energy Build. 2021, 233, 110692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridou, G.; Matsumoto, K.; Doumpos, M. Evaluating the energy poverty in the EU countries. Energy Econ. 2024, 140, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Laurence, H.; Bart, D.; Middlemiss, L.; Maréchal, K. Capturing the multifaceted nature of energy poverty: Lessons from Belgium. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 40, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowski, J.; Lewandowski, P.; Kiełczewska, A.; Bouzarovski, S. A multidimensional index to measure energy poverty: The Polish case. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2020, 15, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, I.; Ferreira, A.C.; Rodrigues, N.; Teixeira, S. Energy Poverty and Its Indicators: A Multidimensional Framework from Literature. Energies 2024, 17, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar Reaños, M.A.; Palencia-González, F.J.; Labeaga, J.M. Measuring and targeting energy poverty in Europe using a multidimensional approach. Energy Policy 2025, 199, 114518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, S.; Nock, D.; Qiu, Y.L.; Xing, B. Unveiling hidden energy poverty using the energy equity gap. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrella, R.; Romero, J.C. Unveiling Hidden Energy Poverty in a Time of Crisis. In Living with Energy Poverty. Perspectives from the Global North and South; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betto, F.; Garengo, P.; Lorenzoni, A. A new measure of Italian hidden energy poverty. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisfeld, K.; Seebauer, S. The energy austerity pitfall: Linking hidden energy poverty with self-restriction in household use in Austria. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 84, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, S.; Teschner, N. No heat, no eat: (Dis)entangling insecurities and their implications for health and well-being. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 336, 116252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Lindley, S.; Bouzarovski, S. The Spatially Varying Components of Vulnerability to Energy Poverty. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 1188–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardo, L.; Cortinovis, C.; Lucertini, G. Prejudices May Be Wrong: Exploring Spatial Patterns of Vulnerability to Energy Poverty in Italian Metropolitan Areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primc, K.; Slabe-Erker, R.; Majcen, B. Constructing energy poverty profiles for an effective energy policy. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Joint Research Centre; Shortall, R.; Mengolini, A. Energy Justice Insights from Energy Poverty Research and Innovation Experiences; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janikowska, O.; Generowicz-Caba, N.; Kulczycka, J. Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden. Energies 2024, 17, 5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2009/72/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 Concerning Common Rules for the Internal Market in Electricity and Repealing Directive 2003/54/EC. 2009. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/72/oj (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1563 of 14 October 2020 on Energy Poverty. C/2020/9600. 2020. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2020/1563/oj (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘Fit for 55’: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality. COM/2021/550 Final. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52021DC0550 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Commission. Communication From the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Tackling Rising Energy Prices: A Toolbox for Action and Support. COM/2021/660 Final. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52021DC0660 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Commission. Energy Poverty Advisory Hub. 2021. Available online: https://energy-poverty.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Decision (EU) 2022/589 of 6 April 2022 Establishing the Composition and the Operational Provisions of Setting Up the Commission Energy Poverty and Vulnerable Consumers Coordination Group. C/2022/2082. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32022D0589 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2023/2407 of 20 October 2023 on Energy Poverty. C/2023/4080. 2023. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2023/2407/oj (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Bouzarovski, S.; Thomson, H.; Cornelis, M. Confronting Energy Poverty in Europe: A Research and Policy Agenda. Energies 2021, 14, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaroiu, A.C.; Roscia, M.; Lazaroiu, G.C.; Siano, P. Review of Energy Communities: Definitions, Regulations, Topologies, and Technologies. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, F.; Guyet, R. The struggle of energy communities to enhance energy justice: Insights from 113 German cases. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoicka, C.E.; Lowitzsch, J.; Brisbois, M.C.; Kumar, A.; Ramirez Camargo, L. Implementing a just renewable energy transition: Policy advice for transposing the new European rules for renewable energy communities. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreño-Rodriguez, A.; Ramallo-González, A.P.; Chinchilla-Sánchez, M.; Molina-García, A. Community energy solutions for addressing energy poverty: A local case study in Spain. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity and Amending Directive 2012/27/EU (Recast). PE/10/2019/REV/1. 2019. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/944/oj (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Recast). PE/48/2018/REV/1. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/2001/oj/eng (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Guhl, F.; Zeigermann, U. Local heat transitions—A comparative case study of five bioenergy villages in Northern and Southern Germany. Z. Für Vgl. Polit. 2024, 18, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziolas, E.; Bournaris, T. Economic and Environmental Assessment of Agro-Energy Districts in Northern Greece: A Life Cycle Assessment Approach. BioEnergy Res. 2019, 12, 1145–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturo, A.; Petrucci, A.; Forzano, C.; Giuzio, G.F.; Buonomano, A.; Athienitis, A. Design and environmental sustainability assessment of energy-independent communities: The case study of a livestock farm in the North of Italy. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 8091–8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Fernández, C.; Peek, D. Connecting the Smart Village: A Switch towards Smart and Sustainable Rural-Urban Linkages in Spain. Land 2023, 12, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Z.; Prohászka, V.; Sallay, Á. The Energy System of an Ecovillage: Barriers and Enablers. Land 2021, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodzińska, K.; Błażejowska, M.; Brodziński, Z.; Łącka, I.; Stolarska, A. Energy Cooperatives as an Instrument for Stimulating Distributed Renewable Energy in Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, L.; Rancilio, G.; Radaelli, L.; Merlo, M. Renewable energy communities and mitigation of energy poverty: Instruments for policymakers and community managers. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 39, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramizaru, E.; Uihlein, A. Energy Communities: An Overview of Energy and Social Innovation, EUR 30083 EN. 2020. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a2df89ea-545a-11ea-aece-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Young, J.; Halleck Vega, S.M. What is the role of energy communities in tackling energy poverty? Measures, barriers and potential in the Netherlands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 116, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumo, F.; Maurelli, P.; Pennacchia, E.; Rosa, F. Urban Renewable Energy Communities and Energy Poverty: A proactive approach to energy transition with Sun4All project. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1073, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellou, E.; Hinsch, A.; Vorkapić, V.; Torres, A.-D.; Konstantopoulos, G.; Matsagkos, N.; Doukas, H. Lessons Learnt and Policy Implications from Implementing the POWERPOOR Approach to Alleviate Energy Poverty. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielig, M.; Kacperski, C.; Kutzner, F.; Klingert, S. Evidence behind the narrative: Critically reviewing the social impact of energy communities in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 94, 102859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukoufikis, G.; Schockaert, H.; Paci, D.; Filippidou, F.; Caramizaru, A.; Della Valle, N.; Candelise, C.; Murauskaite-Bull, I.; Uihlein, A. Energy Communities and Energy Poverty. The Role of Energy Communities in Alleviating Energy Poverty. 2023. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ca1e8f2a-98a5-11ee-b164-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Barroco Fontes Cunha, F.; Carani, C.; Nucci, C.A.; Castro, C.; Santana Silva, M.; Andrade Torres, E. Transitioning to a low carbon society through energy communities: Lessons learned from Brazil and Italy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, F.; Lowitzsch, J. Empowering Vulnerable Consumers to Join Renewable Energy Communities—Towards an Inclusive Design of the Clean Energy Package. Energies 2020, 13, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, P.; Pellegrini-Masini, G.; Klein, J. The Role of Community Energy Schemes in Reducing Energy Poverty and Promoting Social Inclusion: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2024, 17, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaValle, N.; Czako, V. Empowering energy citizenship among the energy poor. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, A.X.; Castaño-Rosa, R. Towards a Just Energy Transition, Barriers and Opportunities for Positive Energy District Creation in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbes, C.; Brummer, V.; Rognli, J.; Blazejewski, S.; Gericke, N. Responding to policy change: New business models for renewable energy cooperatives—Barriers perceived by cooperatives’ members. Energy Policy 2017, 109, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparisi-Cerdá, I.; Manso-Burgos, Á.; Ribó-Pérez, D.; Sommerfeldt, N.; Gómez-Navarro, T. Panel or check? Assessing the benefits of integrating households in energy poverty into energy communities. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 71, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Liang, F.; Pezzuolo, A. Renewable energy communities in rural areas: A comprehensive overview of current development, challenges, and emerging trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 484, 144336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Energy. 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/energy (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Adaptation Challenges and Opportunities for the European Energy System—Building a Climate-Resilient Low-Carbon Energy System; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2019. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions REPowerEU Plan. COM/2022/230 Final. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2022:230:FIN (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Tricarico, L. Community action: Value or instrument? An ethics and planning critical review. J. Archit. Urban. 2017, 41, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallent, N.; Hamiduddin, I.; Juntti, M.; Kidd, S.; Shaw, D. Introduction to Rural Planning: Economies, Communities and Landscapes, 2nd ed.; Glasson, J., Ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Ltd.: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fathullah, M.A.; Subbarao, A.; Muthaiyah, S. Methodological Investigation: Traditional and Systematic Reviews as Preliminary Findings for Delphi Technique. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231190747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkočiūnienė, V.; Vaznonienė, G. Smart Village Development Principles and Driving Forces: The Case of Lithuania. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, R.; Faria, P.; Vale, Z. Demand Response Programs Management in an Energy Community with Diversity of Appliances. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 239, 00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bux, C.; Cangialosi, F.; Amicarelli, V. Biomethane and Compost Production by Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Waste: Suggestions for Rural Communities in Southern Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrosio, G.; Magnani, N. District heating and ambivalent energy transition paths in urban and rural contexts. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebotari, S. Against all odds: Community-owned renewable energy projects in North-West Romania. ACME 2019, 18, 513–528. [Google Scholar]

- Ciuła, J.; Sobiecka, E.; Zacłona, T.; Rydwańska, P.; Oleksy-Gębczyk, A.; Olejnik, T.P.; Jurkowski, S. Management of the Municipal Waste Stream: Waste into Energy in the Context of a Circular Economy—Economic and Technological Aspects for a Selected Region in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, C.; Coscia, J.; Adeyeye, K.; Gallagher, J. Energy security to safeguard community water services in rural Ireland: Opportunities and challenges for solar photovoltaics. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, B.; Monsberger, C.; Auer, H. A framework to estimate the large-scale impacts of energy community roll-out. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honvári, P.; Kukorelli, I.S. Examining the Renewable Energy Investments in Hungarian Rural Settlements: The Gained Local Benefits and the Aspects of Local Community Involvement. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 10, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, S. Wood energy production, sustainable farming livelihood and multifunctionality in Finland. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioakimidis, C.S.; Gutiérrez, I.A.; Genikomsakis, K.N.; Stroe, E.R.; Savuto, E. The use of district heating on a small Spanish village. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems, ECOS 2013, Guilin, China, 16–19 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiński, J.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Sołtysik, M. Analysis of the Economic Soundness and Viability of Migrating from Net Billing to Net Metering Using Energy Cooperatives. Energies 2024, 17, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Dakanali, E.; Dimopoulos, A.; Gyllis, Y. Energy Transition on Sifnos: An Approach to Economic and Social Transition and Development. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N.; Cittati, V.-M. Combining the Multilevel Perspective and Socio-Technical Imaginaries in the Study of Community Energy. Energies 2022, 15, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manniello, C.; Statuto, D.; Di Pasquale, A.; Giuratrabocchetti, G.; Picuno, P. Planning the Flows of Residual Biomass Produced by Wineries for the Preservation of the Rural Landscape. Sustainability 2020, 12, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manos, B.; Partalidou, M.; Fantozzi, F.; Arampatzis, S.; Papadopoulou, O. Agro-energy districts contributing to environmental and social sustainability in rural areas: Evaluation of a local public–private partnership scheme in Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, I.A. Can Renewable Energy Contribute to Poverty Reduction? A Case Study on Romafa, a Hungarian LEADER. In Evaluating the European Approach to Rural Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, C.; Mangano, G. Living Lab for the design and activation of energy communities in the inner areas. TECHNE—J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2023, 26, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, A.; Torre, A.; Bourdin, S. How do local actors coordinate to implement a successful biogas project? Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patkós, C.; Radics, Z.; Tóth, J.B.; Kovács, E.; Csorba, P.; Fazekas, I.; Szabó, G.; Tóth, T. Climate and Energy Governance Perspectives from a Municipal Point of View in Hungary. Climate 2019, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pato, L. Entrepreneurship and Innovation Towards Rural Development Evidence from a Peripheral Area in Portugal. Eur. Countrys. 2020, 12, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, G. Territorial and agro-energy projects in the WesternFrance: The role of farmers-leaders. Cybergeo 2015, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjola, I.; Puusa, A.; Iskanius, P. Potential of community of practice in promoting academia-industry collaboration: A case study. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Intellectual Capital Knowledge Management and Organisational Learning, ICICKM 2015, Bangkok, Thailand, 5–6 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roesler, T.; Hassler, M. Creating niches—The role of policy for the implementation of bioenergy village cooperatives in Germany. Energy Policy 2019, 124, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Porta, C.; Roldán-Blay, C.; Dasí-Crespo, D.; Escrivá-Escrivá, G. Optimising a Biogas and Photovoltaic Hybrid System for Sustainable Power Supply in Rural Areas. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, P.G.; Costa, C.N.; Charalambides, A.G. Environmental, Economical and Marketing Aspects of the Operation of a Waste-to-Energy Plant in the Kotsiatis Landfill in Cyprus. Waste Biomass Valorization 2013, 4, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, I.; Minervini, D. Performative connections: Translating sustainable energy transition by local communities. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 30, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebestyén, T.T.; Pavičević, M.; Dorotić, H.; Krajačić, G. The establishment of a micro-scale heat market using a biomass-fired district heating system. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchoń, A.A.; Zuba-Ciszewska, M. Functioning of Cooperatives within the Context of the Tasks of Communes (Especially Rural)—Selected Economic and Law Issues. Lex Localis—J. Local Self-Gov. 2020, 18, 901–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B. Community: A powerful label? Connecting wind energy to rural Ireland. Community Dev. J. 2016, 53, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkens, I.; Schmuck, P. Transdisciplinary Evaluation of Energy Scenarios for a German Village Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Sustainability 2012, 4, 604–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, J. Assessment of the chances for regional development through lignite deposits utilization in the light of statistical data comparisons. In Proceedings of the 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference, SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 27 June–6 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüste, A.; Schmuck, P. Bioenergy Villages and Regions in Germany: An Interview Study with Initiators of Communal Bioenergy Projects on the Success Factors for Restructuring the Energy Supply of the Community. Sustainability 2012, 4, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromek-Broc, K. The European Green Deal and Regionalisation: Italian and Polish Case Studies. In Regional Approaches to the Energy Transition; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinát, S.; Turečková, K. Local development in the post-mining countryside? Impacts of an agricultural ad plant on rural community. Geogr. Tech. 2016, 11, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balest, J.; Lucchi, E.; Haas, F.; Grazia, G.; Exner, D. Materiality, meanings, and competences for historic rural buildings: A social practice approach for engaging local communities in energy transition. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 863, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janota, L.; Vávrová, K.; Weger, J.; Knápek, J.; Králík, T. Complex methodology for optimizing local energy supply and overall resilience of rural areas: A case study of Agrovoltaic system with Miscanthus x giganteus plantation within the energy community in the Czech Republic. Renew. Energy 2023, 212, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A. Toward a Renewable and Sustainable Energy Pattern in Non-Interconnected Rural Monasteries: A Case Study for the Xenofontos Monastery, Mount Athos. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lode, M.L.; Felice, A.; Martinez Alonso, A.; De Silva, J.; Angulo, M.E.; Lowitzsch, J.; Coosemans, T.; Ramirez Camargo, L. Energy communities in rural areas: The participatory case study of Vega de Valcarce, Spain. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notariello, P.; Aruta, G.; Ascione, F.; Di Palma, B. Architectural Design and Sustainability of a New Rural Renewable Energy Community. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), Split, Croatia, 25–28 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazzi, S.; Ottani, F.; Parenti, M.; Parmeggiani, D.; De Luca, A.; Silvestro, M.G.; Spartà, A.; Tavani, F.; Fontana, P.; Martini, N.; et al. A student-driven multilevel approach for increasing energy sustainability of remote areas in the Emilia Romagna Apennines. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1106, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanos, A.; Koundouri, P.; Papadaki, L.; Pliakou, T.; Toli, E. Water for Tomorrow: A Living Lab on the Creation of the Science-Policy-Stakeholder Interface. Water 2022, 14, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codemo, A.; Ghislanzoni, M.; Prados, M.-J.; Albatici, R. Incorporating public perception of Renewable Energy Landscapes in local spatial planning tools: A case study in Mediterranean countries. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 170, 103358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnoni, S.; Bassi, A.M. Creating Synergies from Renewable Energy Investments, a Community Success Story from Lolland, Denmark. Energies 2009, 2, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGookin, C.; Mac Uidhir, T.; Gallachóir, B.Ó.; Byrne, E. Doing things differently: Bridging community concerns and energy system modelling with a transdisciplinary approach in rural Ireland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, E. Energy Self-Sufficiency of Smaller Rural Centers: Experimental Approaches. Buildings 2024, 14, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Arranz-Piera, P.; Olives, B.; Ivancic, A.; Pagà, C.; Cortina, M. Thermal energy community-based multi-dimensional business model framework and critical success factors investigation in the mediterranean region of the EU. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ißler, R.; Karpenstein-Machan, M.; Schnitzlbaumer, M.; Wilkens, I. Which concepts make Bioenergy villages sustainable? Business fields based on electricity, heat and fuel marketing. Berichte Uber Landwirtsch. 2022, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, J.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Sołtysik, M. The Effectiveness of Energy Cooperatives Operating on the Capacity Market. Energies 2021, 14, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, J.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Sołtysik, M. Determinants of Energy Cooperatives’ Development in Rural Areas—Evidence from Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopoulos, C.; Barral, M.A.; Ruiz, A.; Prados, M.-J.; Fidani, S.; Tsakoumis, G.; Charalampopoulou, V. Planning and engagement arenas for renewable energy landscapes, Paros Island example. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment (RSCy2020), Paphos, Cyprus, 16–18 March 2020; p. 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A. Biodiversity-Proof Energy Communities in the Urban Planning of Italian Inner Municipalities. In Geomatics for Environmental Monitoring: From Data to Services; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroziński, A. Analysis of the possibilities of energy cooperatives functioning in Polish environmental and legal conditions. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2023, 1, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, P.D.; Urbinati, A.; Kirchherr, J. Enablers of Managerial Practices for Circular Business Model Design: An Empirical Investigation of an Agro-Energy Company in a Rural Area. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 873–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vomero, M.; Leone, A.; Ripa, M.N. Renewables Energy Communities to Restore the City/Country Relationship: The Case of San Severo in the Apulia Region (Italy). In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications (ICCSA 2024), Hanoi, Vietnam, 1–4 July 2024; pp. 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabatzis, G.; Malesios, C. Pro-environmental attitudes of users and non-users of fuelwood in a rural area of Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 22, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodkowska-Miszczuk, J.; Kuziemkowska, S.; Verma, P.; Martinát, S.; Lewandowska, A. To know is to accept. Uncovering the perception of renewables as a behavioural trigger of rural energy transition. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2022, 30, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.; García-Riazuelo, Á.; Sáez, L.A.; Sarasa, C. Analysing citizens’ perceptions of renewable energies in rural areas: A case study on wind farms in Spain. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 12822–12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo, P.; García-Casarejos, N.; Salvador, M. Perceptions of local population on the impacts of substitution of fossil energies by renewables: A case study applied to a Spanish rural area. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Juśko, A.; Listosz, A.; Flisiak, M. Spatial and social conditions for the location of agricultural biogas plants in Poland (case study). E3S Web Conf. 2019, 86, 00036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagendijk, A.; Kooij, H.-J.; Veenman, S.; Oteman, M. Noisy monsters or beacons of transition: The framing and social (un)acceptance of Dutch community renewable energy initiatives. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, T.; Müller, K. Lusatia and the coal conundrum: The lived experience of the German Energiewende. Energy Policy 2016, 99, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Segura, F.J.; Frolova, M. How does society assess the impact of renewable energy in rural inland areas? Comparative analysis between the province of Jaén (Spain) and Somogy county (Hungary). Investig. Geográficas 2023, 80, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safonte, G.F.; Trapani, F. A theoretical and methodological framework for the analysis and measurement of environmental heritage at local level. Energy Procedia 2017, 115, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titov, A.; Kövér, G.; Tóth, K.; Gelencsér, G.; Kovács, B.H. Acceptance and Potential of Renewable Energy Sources Based on Biomass in Rural Areas of Hungary. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska-Dabrowska, M.; Świdyńska, N.; Napiórkowska-Baryła, A. Attitudes of Communities in Rural Areas towards the Development of Wind Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüste, A.; Schmuck, P. Social Acceptance of Bioenergy Use and the Success Factors of Communal Bioenergy Projects. In Sustainable Bioenergy Production—An Integrated Approach; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castán Broto, V. Introduction: Community Energy and Sustainable Energy Transitions. In Community Energy and Sustainable Energy Transitions: Experiences from Ethiopia, Malawi and Mozambique; Broto, V.C., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianegonda, A.; Favargiotti, S.; Ciolli, M. Rural–Urban Metabolism: A Methodological Approach for Carbon-Positive and Circular Territories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, P.; Battisti, L.; Larcher, F. Linking Multifunctionality and Sustainability for Valuing Peri-Urban Farming: A Case Study in the Turin Metropolitan Area (Italy). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süsser, D.; Kannen, A. ‘Renewables? Yes, please!’: Perceptions and assessment of community transition induced by renewable-energy projects in North Frisia. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilzing, M.; Vaselli, A.; van Herwaarden, D.J.H.; Walma, K.; Hommes, L.; Sanchis-Ibor, C. Contestations of energy transitions in peri-urban areas: The solar parks of the Vall d’Albaida (Spain). Belgeo 2023, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, M.; Badora, A.; Kud, K. Expectations of the Inhabitants of South-Eastern Poland Regarding the Energy Market, in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. Energies 2023, 16, 5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthaki, F.; Giannaraki, C.; Zafeiraki, E.F.; Kaldellis, J.K. Exploitation of Wave Energy Potential in Aegean Sea: Greece. In Mediterranean Green Buildings & Renewable Energy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickel, K.; Kröger, M.; Bruckmeier, K.; Engwall, Y. The Challenge of Evaluating Policies for Promoting the Multifunctionality of Agriculture: When ‘Good’ Questions Cannot be Addressed Quantitatively and ‘Quantitative Answers are not that Good’. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2009, 11, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsivelakis, M.; Bargiotas, D.; Daskalopulu, A.; Panapakidis, I.P.; Tsoukalas, L. Techno-Economic Analysis of a Stand-Alone Hybrid System: Application in Donoussa Island, Greece. Energies 2021, 14, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figaj, R.; Żołądek, M.; Homa, M.; Pałac, A. A Novel Hybrid Polygeneration System Based on Biomass, Wind and Solar Energy for Micro-Scale Isolated Communities. Energies 2022, 15, 6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardaras, G.; Kraia, T.; Chatzigavriel, S.; Chatzinikolaou, V.; Panopoulos, K.D. A novel hybrid renewable energy system for small decentralized communities. In European Biomass Conference and Exhibition Proceedings; 2023; pp. 530–532. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85174604528&partnerID=40&md5=3eaa1713e3933b96aee86b108c5cb798 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Kardaras, G.; Kraia, T.; Panopoulos, K.D.; Psimmenos, S.; Prosmitis, A.; Voutetakis, S. Life cycle assessment of a 30 MWth biomass district heating plant. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems (ECOS 2019), Wroclaw, Poland, 23–28 June 2019; pp. 3931–3942. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85083174728&partnerID=40&md5=3a2477a47edb466dcdbace0b33aad4fe (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Gandiglio, M.; Marocco, P.; Bianco, I.; Lovera, D.; Blengini, G.A.; Santarelli, M. Life cycle assessment of a renewable energy system with hydrogen-battery storage for a remote off-grid community. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 32822–32834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.; García-Riazuelo, Á.; Sáez, L.A.; Sarasa, C. Economic and territorial integration of renewables in rural areas: Lessons from a long-term perspective. Energy Econ. 2022, 110, 106005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, R.; Föhr, J.; Gyawali, A.; Ranta, T. Investment and Profitability of Community Heating Systems Using Bioenergy in Finland: Opportunities and Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, F.; Firmino, A.; Amado, M. Planning renewable energy in rural areas: Impacts on occupation and land use. Energy 2018, 155, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar, A. Agricultural Biogas—An Important Element in the Circular and Low-Carbon Development in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallanca, C. A New Renaissance for Small Towns through the Development of Territorial and Social Capital. ArcHistoR 2020, 13, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar]

- Stolarski, M.J.; Dudziec, P.; Krzyżaniak, M.; Olba-Zięty, E. Solid Biomass Energy Potential as a Development Opportunity for Rural Communities. Energies 2021, 14, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagini, B.; Bierbaum, R.; Stults, M.; Dobardzic, S.; McNeeley, S.M. A typology of adaptation actions: A global look at climate adaptation actions financed through the Global Environment Facility. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 25, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, T.-Z.; Salem, M.; Kamarol, M.; Das, H.S.; Nazari, M.A.; Prabaharan, N. A comprehensive study of renewable energy sources: Classifications, challenges and suggestions. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kożuch, A.; Cywicka, D.; Górna, A. Forest Biomass in Bioenergy Production in the Changing Geopolitical Environment of the EU. Energies 2024, 17, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. Possibility of utilizing agriculture biomass as a renewable and sustainable future energy source. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch-Michalik, M.; Gaworski, M. Agricultural vs forest biomass: Production efficiency and future trends in Polish conditions. Agron. Res. 2017, 15, 322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Belaid, A.; Guermoui, M.; Khelifi, R.; Arrif, T.; Chekifi, T.; Rabehi, A.; El-Kenawy, E.-S.M.; Alhussan, A.A. Assessing Suitable Areas for PV Power Installation in Remote Agricultural Regions. Energies 2024, 17, 5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, N.; Maruzzo, V.; Benesperi, I.; Bousquet, A.; Lushnikova, A.; Baricco, M.; Brunetti, F.; Ménézo, C.; Lartigau-Dagron, C.; Barbero, N. Opportunities for renewable energy sources in mountain areas and the Alps case. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 223, 115983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, Ž.; Đurin, B.; Dogančić, D.; Kranjčić, N. Hydro-Energy Suitability of Rivers Regarding Their Hydrological and Hydrogeological Characteristics. Water 2021, 13, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumse, S.; Bilgili, M.; Yildirim, A.; Sahin, B. Comparative Analysis of Global Onshore and Offshore Wind Energy Characteristics and Potentials. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onea, F.; Manolache, A.I.; Ganea, D. Assessment of the Black Sea High-Altitude Wind Energy. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Echevarria, A.; Irshad, N.; Rivera-Matos, Y.; Richter, J.; Chhetri, N.; Parmentier, M.J.; Miller, C.A. Ending the Energy-Poverty Nexus: An Ethical Imperative for Just Transitions. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2022, 28, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagna, L.; Radaelli, L.; Ricci, M.; Rancilio, G. Exploring the Complexity of Energy Poverty in the EU: Measure it, Map it, Take Actions. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, R.; Noble, B.; Poelzer, G.; Fitzpatrick, P.; Belcher, K.; Holdmann, G. Advancing local energy transitions: A global review of government instruments supporting community energy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 83, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, A.; Scandurra, G. The Multifaced Challenge to Tackle Energy Poverty: Outlook Scenarios for EU Countries. In Methodological and Applied Statistics and Demography III. SIS 2024. Italian Statistical Society Series on Advances in Statistics; Pollice, A., Mariani, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchi, P.; van Lierop, M.; Geneletti, D.; Stremke, S. Advancing the relationship between renewable energy and ecosystem services for landscape planning and design: A literature review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 35, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | References |

|---|---|

| Assessment | [78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110] |

| Barriers and gaps | [78,82,97,111,112] |

| Implementation | [113,114,115,116,117,118] |

| Management and Planning | [108,119,120,121,122,123] |

| Modeling | [92,105,122,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132] |

| Public opinion | [103,110,112,120,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143] |

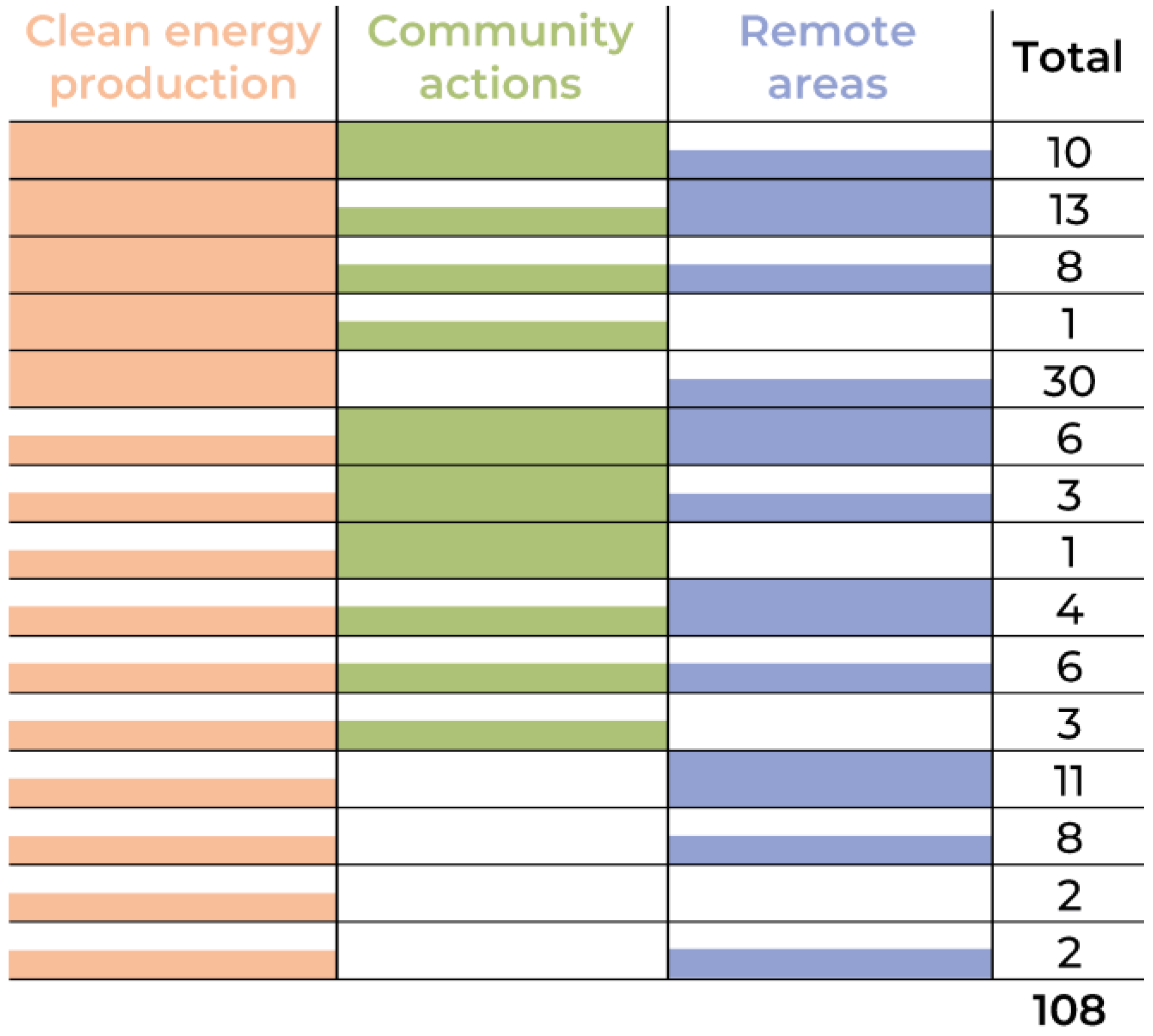

| Step | Number of Records |

|---|---|

| 1.1 Keyword search through Scopus | |

| 3 domains + Year of publication | 4422 |

| Geographical extent | 1127 |

| 1.2 Screening | |

| Non-EU case studies or multiple countries | 494 |

| Out-of-topic or related to the urban context | 135 |

| No case studies | 208 |

| At least one EU case study | 286 |

| Duplicates | 4 |

| 2.1 Links identification among domains | |

| Second round screening | |

| Non-EU case studies or multiple countries | 496 |

| Out-of-topic or related to the urban context | 153 |

| No case studies | 208 |

| At least one EU case study | 266 |

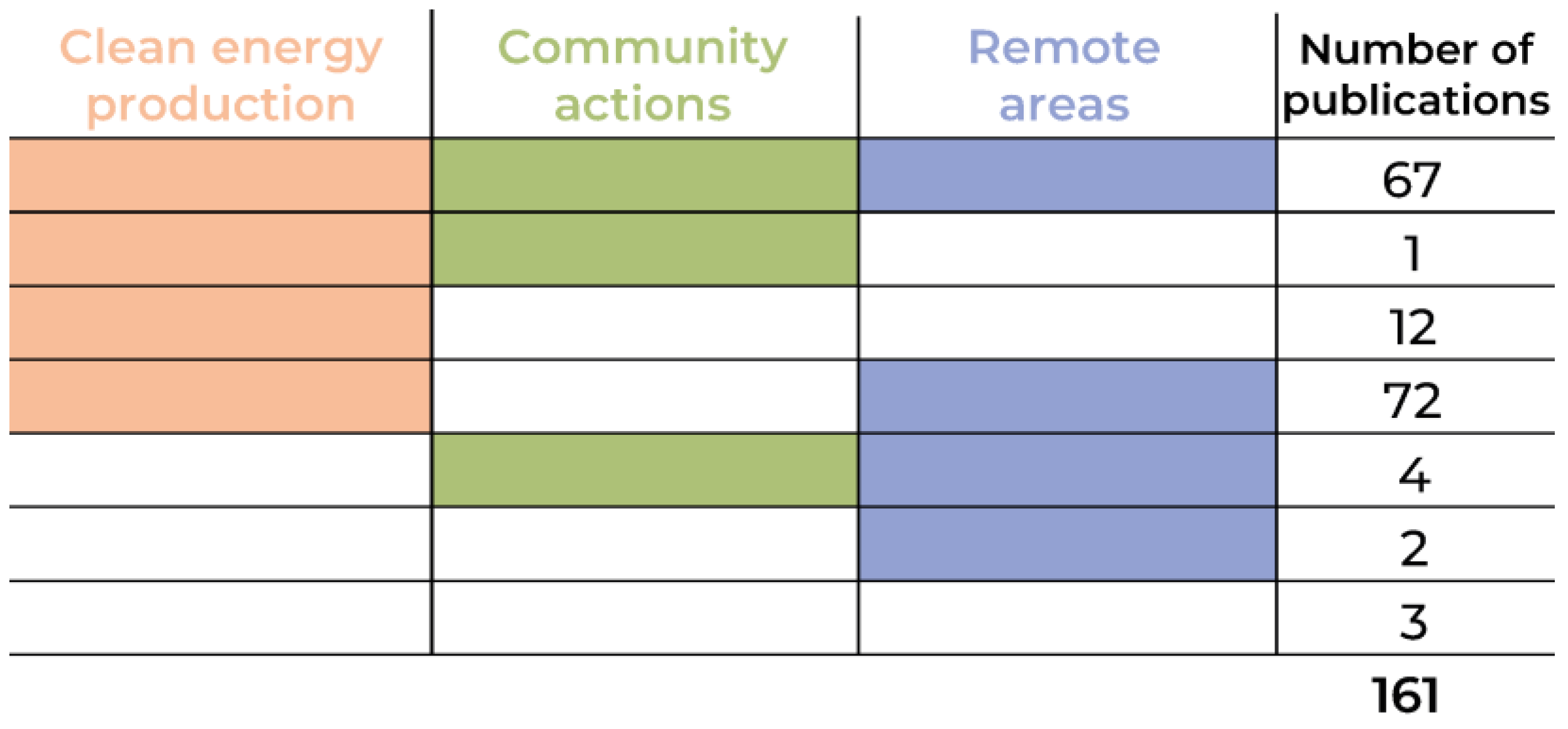

| Weights assignment | |

| 1, 1, 1 | 67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Longo, A.; Basso, M.; Lucertini, G.; Zardo, L. Exploring the Links Between Clean Energies and Community Actions in Remote Areas: A Literature Review. Energies 2025, 18, 6350. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236350

Longo A, Basso M, Lucertini G, Zardo L. Exploring the Links Between Clean Energies and Community Actions in Remote Areas: A Literature Review. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6350. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236350

Chicago/Turabian StyleLongo, Alessandra, Matteo Basso, Giulia Lucertini, and Linda Zardo. 2025. "Exploring the Links Between Clean Energies and Community Actions in Remote Areas: A Literature Review" Energies 18, no. 23: 6350. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236350

APA StyleLongo, A., Basso, M., Lucertini, G., & Zardo, L. (2025). Exploring the Links Between Clean Energies and Community Actions in Remote Areas: A Literature Review. Energies, 18(23), 6350. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236350