Abstract

Driven by the global energy transition and carbon-neutrality goals, virtual power plants (VPPs) are expected to aggregate distributed energy resources and participate in multiple electricity markets while achieving economic efficiency and low carbon emissions. However, the strong volatility of wind and photovoltaic generation, together with the coupling between electric and thermal loads, makes real-time VPP scheduling challenging. Existing deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-based methods still suffer from limited predictive awareness and insufficient handling of physical and carbon-related constraints. To address these issues, this paper proposes an improved model, termed SAC-LAx, based on the Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) deep reinforcement learning algorithm for intelligent VPP scheduling. The model integrates an Attention–xLSTM prediction module and a Linear Programming (LP) constraint module: the former performs multi-step forecasting of loads and renewable generation to construct an extended state representation, while the latter projects raw DRL actions onto a feasible set that satisfies device operating limits, energy balance, and carbon trading constraints. These two modules work together with the SAC algorithm to form a closed perception–prediction–decision–control loop. A campus integrated-energy virtual power plant is adopted as the case study. The system consists of a gas–steam combined-cycle power plant (CCPP), battery storage, a heat pump, a thermal storage unit, wind turbines, photovoltaic arrays, and a carbon trading mechanism. Comparative simulation results show that, at the forecasting level, the Attention–xLSTM (Ax) module reduces the day-ahead electric load Mean Absolute Percentage Error () from 4.51% and 5.77% obtained by classical Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) models to 2.88%, significantly improving prediction accuracy. At the scheduling level, the SAC-LAx model achieves an average reward of approximately 1440 and converges within around 2500 training episodes, outperforming other DRL algorithms such as Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3), and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). Under the SAC-LAx framework, the daily net operating cost of the VPP is markedly reduced. With the carbon trading mechanism, the total carbon emission cost decreases by about 49% compared with the no-trading scenario, while electric–thermal power balance is maintained. These results indicate that integrating prediction enhancement and LP-based safety constraints with deep reinforcement learning provides a feasible pathway for low-carbon intelligent scheduling of VPPs.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Driven by global carbon-neutrality strategies and energy transition targets, power systems are rapidly evolving toward high penetration of renewable and distributed energy resources. VPPs have emerged as a key mechanism to aggregate heterogeneous distributed energy resources (DERs), controllable loads and storage, and to enable their coordinated participation in electricity and ancillary service markets, thereby enhancing system flexibility and economic efficiency [1,2].

Modern VPPs rely on advanced information and communication technologies (ICT) and AI-enabled energy management platforms to realize wide-area sensing, data acquisition and intelligent decision-making [3,4,5,6,7]. In particular, campus-scale integrated electric–thermal VPPs provide a representative scenario in which combined-cycle power plants, heat pumps, thermal storage and renewable units are jointly scheduled to meet coupled electric and thermal demands while interacting with the electricity and carbon markets [8,9]. However, the strong volatility of wind and photovoltaic generation, the coupling between multi-energy carriers, and the increasing penetration of demand-side resources pose significant challenges to real-time VPP scheduling under multiple physical and economic constraints [10].

1.2. Related Work: Forecasting and DRL-Based VPP Scheduling

At the forecasting level, Reference [11] provides a comprehensive review of intelligent load forecasting technologies for new power systems, covering classical statistical models, machine-learning approaches and a wide range of deep-learning architectures such as Convolutional Neural Networks, LSTM networks, GRUs, attention mechanisms and Transformer-based models. It shows that deep neural networks with multi-scale temporal modeling and attention can significantly improve forecasting accuracy under diverse operating scenarios and emphasizes the importance of multi-step prediction and scenario-specific feature design. In integrated energy systems, Reference [12] applies deep multitask learning to jointly forecast electricity, heat and gas loads in an industrial park, exploiting shared representations across multiple energy carriers to enhance prediction performance. For virtual power plants, Reference [13] develops a decision-support system based on bidirectional LSTM networks to improve long-term forecasting accuracy of VPP outputs. In addition, Reference [14] proposes an xLSTM-Informer model for urban parking-demand forecasting and verifies that extended LSTM variants combined with attention and sequence-to-sequence structures can better capture complex temporal patterns. These studies confirm the effectiveness of advanced recurrent and attention-enhanced architectures for load and renewable forecasting, and motivate the adoption of similar techniques in VPP scheduling frameworks. Reference [15] further reviews artificial-intelligence-based technologies for VPPs and points out that high-quality forecasts are a key enabler for intelligent dispatch.

At the scheduling level, deep reinforcement learning has been widely investigated for economic dispatch and energy management. Reference [16] proposes an optimal scheduling framework for integrated energy systems that combines deep-learning-based prediction models with DRL, demonstrating that improved forecasts can translate into lower operating costs. Reference [17] uses a DDPG algorithm to control energy storage and power distribution between two microgrids with continuous action spaces. Reference [18] applies DRL to the economic dispatch of a VPP in the Internet-of-Energy environment. Reference [19] introduces an improved PPO algorithm with reward-based prioritization to enhance training stability and exploration efficiency. Safety-oriented DRL algorithms for energy-system scheduling are developed in Reference [20], where operational risks and constraint satisfaction are explicitly considered. SAC is employed in Reference [21] to optimize the joint scheduling of electrical and thermal energy storage, leveraging entropy regularization and twin critic networks. For low-carbon and networked multi-energy systems, Reference [22] adopts a multi-agent SAC algorithm for coordinated energy management of networked microgrids. Game-theoretic and hierarchical DRL frameworks for VPP trading and multi-microgrid coordination are presented in References [23,24]. In the specific context of virtual power plants, Reference [25] develops an intelligent scheduling scheme based on deep reinforcement learning, where a VPP environment model is constructed and DRL agents are trained to coordinate distributed resources and participate in electricity markets. These works demonstrate the strong potential of DRL for handling high-dimensional state spaces and complex operating conditions in integrated energy systems, but most of them still rely on relatively simple state representations and treat physical constraints mainly through reward penalties or action clipping.

Several recent contributions attempt to couple forecasting modules with DRL-based scheduling. Reference [16] already integrates deep-learning-based prediction into a DRL-based scheduling framework for integrated energy systems, and Reference [24] designs a hierarchical DRL energy-management strategy that leverages predicted information for a VPP with multiple heterogeneous microgrids. However, as also reflected in the reviews [11,15], existing approaches often adopt a loosely coupled design: the forecasting block typically runs as an external module whose outputs are passed to the DRL agent in an aggregated or short-horizon form, while the Markov state does not explicitly encode multi-step prediction trajectories. In addition, physical and carbon-related constraints—such as electric/thermal balance, device operating limits and carbon trading rules—are usually handled indirectly by soft penalties in the reward function. There is still a lack of unified frameworks that (i) embed high-accuracy, multi-step forecasts directly into the DRL state to enhance predictive awareness and (ii) enforce power–heat balance, device limits and carbon-emission constraints through explicit feasibility projection inside the decision loop. These gaps motivate the SAC-LAx framework proposed in this paper, which integrates an Attention–xLSTM prediction module and an in-loop Linear Programming constraint module into the SAC algorithm to realize prediction-enhanced, constraint-aware scheduling for VPP.

1.3. Contributions of This Work

Compared with the above studies, the main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- Prediction-enhanced state representation: An Attention–xLSTM prediction module is designed to perform multi-step forecasting of electrical loads and renewable outputs. The predicted trajectories are concatenated with real-time measurements to form an augmented state vector, enabling the DRL agent to exploit both current and future information when learning the scheduling policy. Comparative experiments against classical LSTM and GRU predictors show that the Ax module significantly improves day-ahead electric-load forecasting accuracy.

- Constraint-aware DRL scheduling with in-loop LP projection: A Linear Programming constraint module is embedded between the SAC actor and the VPP environment. This module projects raw continuous actions onto a feasible set that simultaneously satisfies power and heat balance, device operating limits and carbon trading constraints, thus enforcing strict feasibility at every decision step instead of relying solely on reward penalties.

- Integrated evaluation on a campus-scale VPP with carbon trading: A realistic campus integrated energy system in Lingang, Shanghai, including a combined-cycle power plant, battery storage, heat pump, thermal storage, wind turbines, photovoltaic arrays and a carbon trading mechanism, is used as the case study. Simulation results demonstrate that SAC-LAx achieves faster convergence and higher average rewards than baseline DRL algorithms such as SAC, DDPG, TD3 and PPO, while reducing net operating cost and carbon emission cost and maintaining electric–thermal power balance under different operating scenarios.

Through the joint integration of prediction enhancement and in-loop LP-based constraint handling into the SAC framework, the proposed SAC-LAx model provides a practicable pathway toward low-carbon, intelligent scheduling of VPPs in the context of high renewable penetration and multi-energy coupling.

2. VPP System Modeling

2.1. Overview of the VPP

VPP is an intelligent scheduling and management platform that uses advanced information and communication technologies to aggregate DERs, flexible loads and storage devices into a unified controllable entity. Its main role is to improve energy efficiency and operational flexibility, while providing peak shaving, frequency regulation, reserve capacity and other ancillary services through market-based operation so that economic performance and system reliability can be achieved simultaneously.

In general, a VPP consists of dispersed energy units, an ICT infrastructure and a central control center. The energy units include photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, energy storage systems and electric vehicles. The ICT layer is responsible for real-time monitoring, data collection and communication, whereas the control center acts as the “brain” of the system, performing data analysis, optimization of resource scheduling and interactions with electricity markets. Functionally, a VPP can be viewed as a multi-layer architecture including an infrastructure layer, a perception–analysis layer, a decision–execution layer and a market participation layer, which together support DER aggregation, forecasting, optimal scheduling and market bidding.

Under high renewable penetration and coupled multi-energy flows, VPPs still face challenges such as uncertainty in generation and demand forecasts, strong coupling among devices and the computational burden of real-time optimization. To investigate these issues, this paper adopts the intelligent energy management project of a university campus in Lingang, Shanghai, as a representative case. The campus-scale wind–solar–thermal–storage VPP considered in this study is shown in Figure 1 and comprises a CCPP formed by a gas turbine and waste-heat boiler, a heat pump, photovoltaic arrays, wind turbines, battery storage and a thermal storage tank.

Figure 1.

Integrated energy VPP model architecture of the campus.

2.2. Physical Equipment Dynamic Models

To support optimization scheduling and policy training, the main components of the VPP are modeled in a unified manner. The model adopts a node–edge energy flow representation approach, following the principles of energy conservation and efficiency constraints. An example is illustrated as follows:

- Combined Cycle Power Plant

The CCPP takes natural gas as input and outputs both electric and thermal power, which can be expressed as

where and represent the electrical and thermal efficiencies, respectively.

- 2.

- Energy Storage System

The energy storage system must satisfy the energy conservation relationship:

where and denote the charging and discharging powers, and are the corresponding efficiencies, and is the energy stored at time .

To support optimal scheduling and policy training, the core components of the VPP adopt a unified modeling framework, which is constructed based on the principles of energy conservation and efficiency constraints through a node-edge energy flow representation approach. For other devices such as photovoltaic modules, wind turbines, heat pumps, and thermal storage tanks, their modeling logic is consistent with that of units like CCPPs and energy storage systems, all adhering to the core criteria of energy balance and efficiency orientation. This paper only presents the overall modeling framework, and the detailed quantitative formulations of specific devices can be derived in accordance with the unified logic.

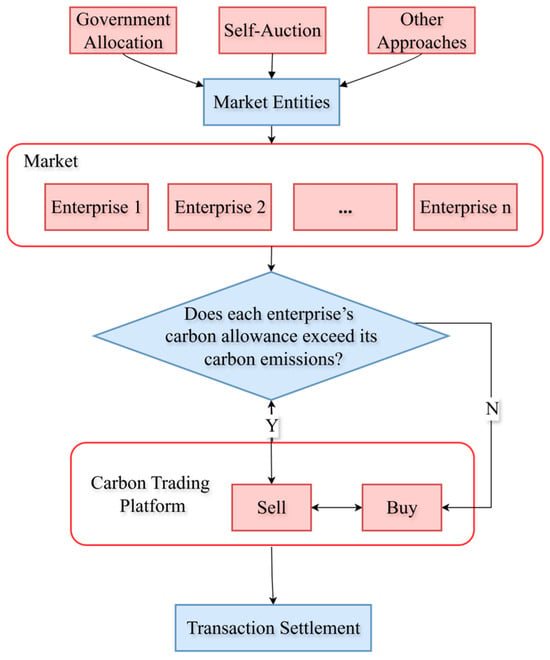

2.3. Carbon Trading Mechanism Modeling

The VPP optimizes energy utilization and reduces carbon emissions through the centralized management of distributed renewable resources such as solar and wind power, together with energy storage systems. In the carbon trading market, this emission reduction can be monetized as carbon credits or emission allowances, providing additional revenue for the VPP. Within this framework, the VPP acts as a flexible energy management platform that can freely trade emission rights in the carbon market. The overall process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Carbon trading mechanism.

To reflect the low-carbon constraints of system operation, this study incorporates both carbon emission quotas and carbon cost terms into the scheduling model. The total carbon emissions of the VPP are defined as the sum of emissions from all individual devices:

where is the carbon emission factor of device , and is its corresponding energy consumption.

When the total carbon emission exceeds the allocated carbon quota , the VPP must purchase additional carbon allowances, and the corresponding carbon cost can be expressed as

where denotes the carbon price coefficient.

This mechanism provides an economic incentive for the VPP to prioritize the dispatch of low-carbon energy sources, thereby achieving a coordinated balance between economic efficiency and environmental sustainability.

2.4. Objective Function and Constraints

The scheduling of a VPP requires a balance between economic efficiency, low-carbon operation, and market profitability. The comprehensive optimization objective constructed in this paper is formulated as

where represents the energy operation cost, denotes the carbon emission cost, and is the market revenue. The coefficients , , and are weighting factors reflecting the relative importance of each objective.

In particular, the term represents the carbon emission penalty associated with emissions from the CCPP, heat pump and other controllable devices, and is explicitly included in the total operating cost reported in the numerical results.

The main constraint conditions include the following:

- Power Balance

- 2.

- Thermal Balance

- 3.

- Device Boundary and Ramp Rate

- 4.

- Carbon Quota

- 5.

- Battery energy storage

The charging and discharging powers of the battery are bounded by

The state of charge (SOC) evolves according to

with the energy limits

where and denote the charging and discharging efficiencies of the battery, respectively.

- 6.

- Thermal storage tank

The charging and discharging heat powers of the thermal storage tank satisfy

The stored thermal energy dynamics are

with the bounds

where and are the charging and discharging efficiencies of the thermal storage, respectively.

- 7.

- Electric heat pump

The electrical input power of the heat pump is constrained by

The produced heat is related to the electrical input through the coefficient of performance (COP):

where is usually bounded as

- 8.

- Grid power trading

The power exchanged with the main grid is written as

where and denote the purchased and sold powers, respectively.

Their operating bounds are

In summary, the above model maintains conciseness while capturing the essential operational characteristics of the VPP. It establishes a solid foundation for developing a DRL-based scheduling algorithm that integrates both physical feasibility and economic efficiency.

3. Algorithm Design

To address the limitations of the conventional SAC algorithm—namely low sample efficiency, insufficient constraint modeling, and poor responsiveness to future load variations—this study proposes an improved algorithm termed SAC-LAx.

The proposed method integrates a Linear Programming-based feasible domain constraint module and an Attention–xLSTM prediction module, enabling the agent to achieve predictive perception and constraint-aware decision-making in multi-energy collaborative scheduling scenarios.

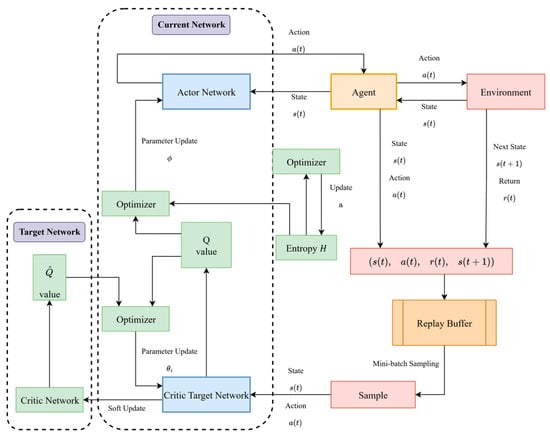

3.1. Overview of the SAC Algorithm

This study adopts the SAC algorithm as the foundational framework, as illustrated in Figure 3. By introducing an entropy regularization term while maximizing the expected return, SAC enhances the exploration capability of the policy. Moreover, the use of twin Critic networks and target networks effectively mitigates the overestimation problem of Q-values, thereby improving training stability, convergence speed, and sample efficiency.

Figure 3.

Framework of the SAC algorithm.

The core objective of the SAC algorithm is to maximize the following function:

where denotes the immediate reward at time , which is designed as the negative weighted sum of the operating cost, carbon cost and imbalance penalties minus the market revenue, consistent with the comprehensive objective function in (5). In this way, maximizing the cumulative reward is equivalent to minimizing the overall operation and carbon costs while maintaining system security. represents the policy entropy, and is a temperature coefficient used to balance exploration and exploitation.

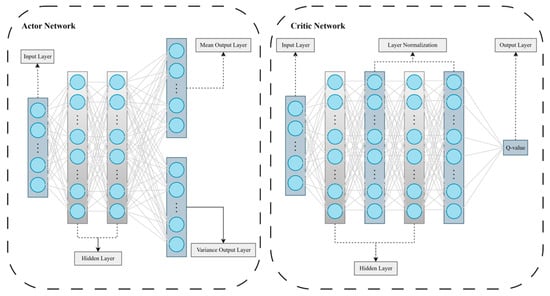

The algorithm adopts an Actor–Critic architecture, as illustrated in Figure 4, where the Actor is responsible for generating a continuous action distribution, and the Critic estimates the state–action value function. This study follows this structure and further enhances its functionality on this basis.

Figure 4.

Neural network structures of the Actor and Critic.

In the proposed VPP scheduling problem, the interaction between the agent and the environment is formulated as a Markov decision process (MDP). The state vector at time collects the aggregated electrical and thermal loads, wind and PV outputs, and electricity and gas prices, as well as the states of charge of the battery and thermal storage. These variables summarize the current operating condition of the VPP. The continuous action vector consists of the scheduled output of the gas turbine in the CCPP, the charging and discharging power commands of the battery, and the electrical input of the heat pump. All action variables are first normalized to the interval [−1, 1] and then linearly mapped to their physical operating ranges before being passed to the LP-constraint module and the VPP environment.

However, the traditional SAC algorithm still exhibits several limitations when applied to integrated energy scheduling problems:

- It lacks the ability to predict future state variations, resulting in insufficient policy foresight;

- It struggles to maintain action feasibility under complex multi-energy constraints;

- It suffers from low sample efficiency in high-dimensional state spaces.

To address the above issues, this paper proposes an improved algorithm, SAC-LAx, which incorporates a prediction enhancement module and a linear constraint correction module into the standard SAC framework, thereby achieving prediction-driven and safety-constrained optimal scheduling.

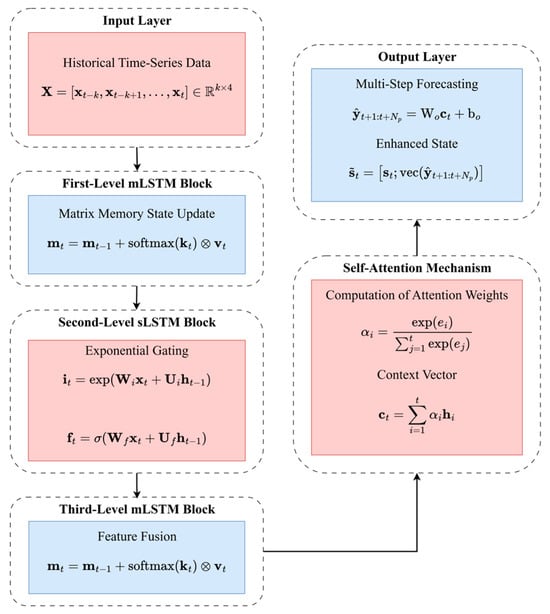

3.2. Prediction Enhancement Module

To enhance the algorithm’s capability of perceiving future states, an Attention–xLSTM prediction module is introduced. The xLSTM used in this work is an extended variant of the conventional LSTM, which enriches the gating and memory-update mechanism so that the network can capture long- and short-term dependencies at multiple temporal scales. Compared with standard LSTM, xLSTM alleviates issues such as limited ability to represent multi-scale temporal patterns, sensitivity to long-sequence vanishing gradients, and insufficient separation between trend and fluctuation components. As illustrated in Figure 5, the module adopts a three-layer stacked structure consisting of mLSTM–sLSTM–mLSTM, which achieves high-precision forecasting of electrical load and renewable generation through multi-scale temporal modeling and attention-based feature extraction.

Figure 5.

Architecture of the Attention–xLSTM prediction model.

The prediction results are encoded as an extended state vector:

where denotes the current environmental state, including aggregated electrical and thermal loads, renewable outputs, storage states and price signals; represents the -step-ahead predicted sequence of electric load and renewable generation provided by the Attention–xLSTM module; and is the prediction horizon length.

This extended state vector is subsequently used as the input to the SAC algorithm, enabling the agent to acquire anticipatory awareness of upcoming trends during training. Unlike the conventional SAC framework, which relies solely on instantaneous states, the proposed structure significantly enhances the foresight and training stability of the policy network. Under conditions of electricity price fluctuations and renewable generation uncertainty, this design facilitates proactive optimization of energy storage and load scheduling, thereby mitigating passive responses and improving overall operational adaptability.

3.3. Linear Programming Constraint Module

In continuous control scenarios of DRL, the actions output by the agent often fail to satisfy physical constraints such as electrical and thermal balance, storage capacity limits, and carbon emission quotas. To ensure the feasibility of control actions, this paper introduces a Linear Programming constraint module at the edge layer, which projects the raw actions onto the feasible domain to guarantee that the resulting control decisions remain physically valid.

Assume that the action vector output by the agent at time step is . After correction through the LP module, the feasible action is obtained. The constraint projection problem can be formulated as

where matrices and , and vectors and , represent the boundary and energy balance constraints of the system, respectively.

This module solves the projection problem in a convex optimization form, which ensures high computational efficiency, fast convergence, and numerical stability. The constraint-projected actions effectively guarantee that the control decisions satisfy all physical and safety constraints, thereby significantly reducing invalid exploration during the training process. In SAC-LAx, the LP constraint module is embedded inside the decision loop: at each time step, the raw action output by the Actor is first passed through the LP projection, and only the corrected feasible action is applied to the environment. As a result, both the next state and the reward are generated under LP-corrected actions during training and deployment, meaning that the policy is explicitly learned under constraint-aware dynamics rather than being adjusted in an offline post-processing stage.

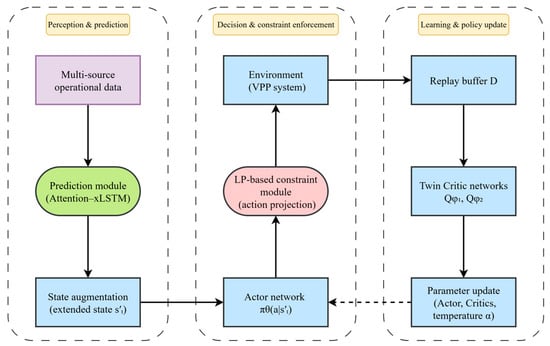

3.4. Overall Algorithm Framework

Figure 6 illustrates the overall framework of the proposed SAC-LAx algorithm. Built upon the conventional SAC architecture, SAC-LAx organizes the decision-making process into three tightly coupled stages: perception and prediction, decision and constraint enforcement, and learning and policy update. In the perception stage, multi-source operational data of the VPP, including loads, renewable generation, storage states and energy prices, are fed into the prediction module (Attention–xLSTM). The prediction outputs are then combined with the current measurements by the state-augmentation block to construct the extended state , which encodes both the present operating condition and the look-ahead information for the next few time steps.

Figure 6.

Overall framework of the SAC-LAx algorithm.

In the decision and constraint-enforcement stage, the actor network receives the extended state and generates a raw continuous action representing the scheduled outputs of key controllable devices. Before this action is applied to the VPP system, the LP-based constraint module solves the projection problem in (13) to obtain a feasible action that satisfies the power–heat balance, equipment limits and carbon-related constraints. The environment interacts only with , and returns the next extended state and the immediate reward . This design ensures that all executed actions are physically valid and that the policy is learned under constraint-aware dynamics rather than through offline post-processing.

In the learning and policy-update stage, the transition is stored in the replay buffer and repeatedly sampled to update the twin Critic networks and as well as the actor parameters and the temperature coefficient . The twin Critics evaluate the soft Q-values and provide target values for the entropy-regularized Bellman backups, while the actor is optimized to maximize the expected return plus entropy under the LP-corrected transitions. Through this iterative interaction–evaluation–update loop, SAC-LAx achieves a synergistic mechanism of “state augmentation–constraint correction–policy optimization”, enabling the VPP to obtain anticipatory, safe and economically efficient scheduling strategies in complex and uncertain operating environments.

4. Case Study and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

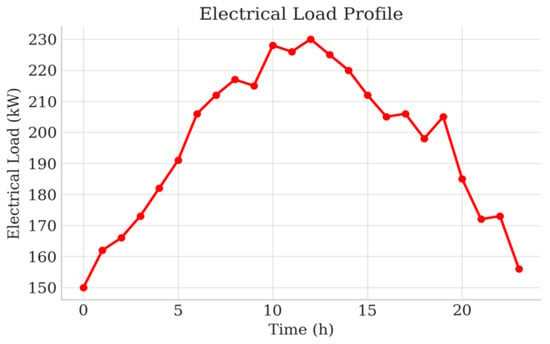

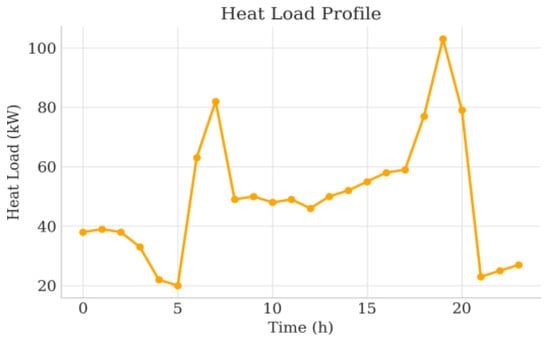

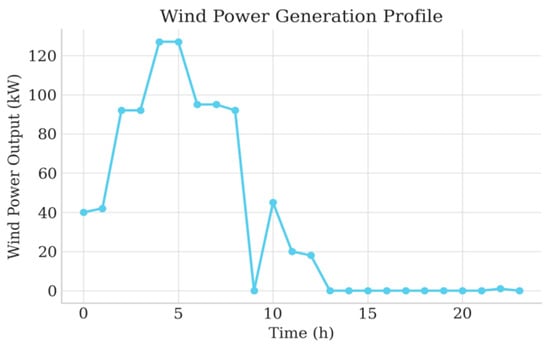

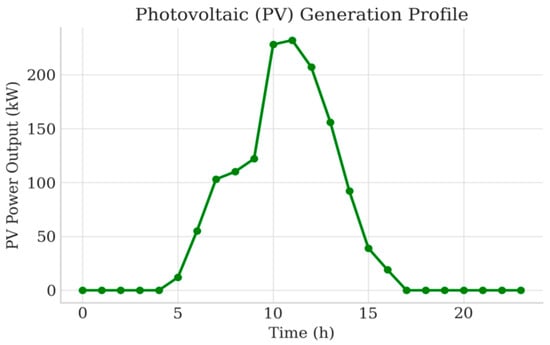

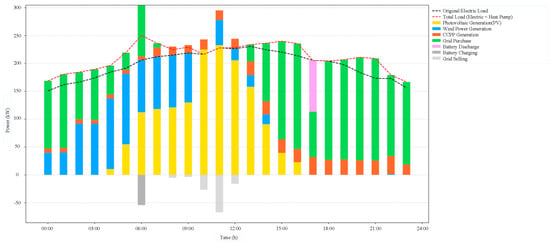

This case study is based on the integrated energy VPP of a university campus in Lingang, Shanghai. The scheduling horizon is 24 h with a time resolution of 1 h. The system configuration, including the CCPP, heat pump, battery, thermal storage tank, PV array and wind turbine, is summarized in Table 1, while the time-of-use electricity price and gas cost profiles are shown in Figure 7. The corresponding electrical and thermal loads and renewable generation profiles over a representative day are depicted in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11.

Table 1.

Equipment Parameters.

Figure 7.

Time-of-use electricity price and gas cost.

Figure 8.

Electrical load of the VPP.

Figure 9.

Thermal load of the VPP.

Figure 10.

Wind power output of the VPP.

Figure 11.

PV power output of the VPP.

All experiments in this study were implemented using Python 3.12.The deep reinforcement learning framework was developed based on Stable-Baselines3 (v2.6.0) and PyTorch (v2.5.1+cu118), while the simulation environment was constructed using Gym (v0.26.2). Data preprocessing and visualization were carried out using NumPy (v1.26.4), Pandas (v2.2.2), Matplotlib (v3.10.1), SciPy (v1.15.2), and Scikit-learn (v1.5.1).The virtual power plant modeling and optimization were conducted using Python with the PyPSA-based environment.

As illustrated in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, the electrical and thermal loads of the campus exhibit clear daily variations, and the outputs of wind turbines and PV panels show strong volatility and intermittency. Wind power fluctuates with wind speed, while PV generation is zero at night, increases in the morning, peaks around noon, and decreases as solar irradiance weakens. These characteristics indicate that the VPP scheduler must be robust against renewable fluctuations and possess sufficient predictive capability; otherwise, it will face higher risks of electricity shortages and expensive peak-period purchases.

The historical dataset used in this study consists of multi-month operational records of the campus VPP, including electrical and thermal loads, wind and PV outputs, and electricity and gas prices, sampled at 1 h intervals. All time-series variables are first cleaned to remove missing and obviously abnormal values, and then normalized to the range [0, 1] using min–max scaling before being fed into the neural networks. This normalization accelerates the convergence of the prediction and DRL models and avoids numerical imbalance among heterogeneous features.

For the prediction module, the dataset is divided in chronological order into three subsets: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for out-of-sample testing. The Attention–xLSTM model is trained on the training set, with hyperparameters tuned on the validation set, and its final performance is evaluated on the test set using , and , as reported in Section 4.2. During VPP operation, a rolling-prediction strategy is adopted: at the beginning of each day, the trained Attention–xLSTM takes the latest historical measurements as input and generates multi-step forecasts of the next-day electrical and thermal loads and renewable outputs.

For the DRL scheduler, each episode corresponds to a 24 h dispatch horizon. The environment simulator uses the same normalized profiles of loads, renewable generation and prices, combined with the prediction outputs, to construct the state variables. During training, the prediction model is kept fixed, and the SAC-LAx agent interacts with the environment by repeatedly sampling episodes from the historical dataset. The reward function is defined based on the comprehensive cost in (5), so that maximizing the cumulative reward is equivalent to minimizing the weighted sum of energy cost, carbon cost and imbalance penalties while accounting for market revenues. Continuous action variables are normalized to [−1, 1] during training and then linearly mapped back to their physical operating ranges when interacting with the VPP model.

4.2. Forecasting Performance of the Prediction Module

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed prediction-enhancement module, this subsection compares the forecasting performance of four electric-load models: a classical LSTM network, a GRU network, a vanilla xLSTM model (used for ablation), and the proposed Attention–xLSTM model. All models are trained and tested on the same dataset and use identical input–output configurations and data splits, so that the performance differences can be attributed to the model architectures rather than experimental settings. The evaluation focuses on the electric load series, which is the most critical input for VPP scheduling.

Table 2 summarizes the forecasting accuracy of the four models in terms of mean absolute error (), root mean square error (), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (). The proposed Attention–xLSTM achieves the best performance across all three metrics.

Table 2.

Forecasting performance of different models for the electric load.

As shown in Table 2, the proposed Attention–xLSTM model consistently outperforms the classical LSTM, GRU, and the vanilla xLSTM used in the ablation study. The xLSTM structure itself is an improved variant designed to mitigate the limitations of standard LSTM in long-sequence modeling, while the introduction of the attention mechanism in Ax further enhances the representation of multi-scale temporal features. Overall, Attention–xLSTM achieves the best forecasting performance among all compared models in both the ablation study and horizontal algorithm comparison, providing more accurate and reliable look-ahead information for the subsequent SAC-LAx scheduling.

From the perspective of reinforcement learning, the prediction accuracy of the Attention–xLSTM module directly affects the quality of the extended state provided to the SAC-LAx agent. If the forecast errors are large, the predicted future trajectories of loads and renewable outputs may deviate significantly from the actual evolution, leading to biased actions such as over-charging or under-utilizing storage and consequently higher operating and carbon costs. By reducing the MAPE of load forecasting compared with LSTM, GRU and vanilla xLSTM, the proposed Ax model effectively mitigates this error propagation and provides more reliable look-ahead information for decision-making. In addition, the in-loop LP constraint and the entropy-regularized SAC framework further improve the robustness of the learned policy, so that moderate prediction errors do not cause infeasible or highly suboptimal dispatch actions.

4.3. Scheduling Performance Under Different Algorithms

To ensure the convergence and stability of the SAC-based scheduling strategy, the key training parameters are configured as summarized in Table 3. The DRL environment is constructed using the normalized historical profiles of loads, renewable generation and prices described in Section 4.1, together with the rolling predictions generated by the Attention–xLSTM module. Each episode corresponds to a 24 h dispatch horizon, and the SAC-LAx agent interacts with the environment by repeatedly sampling episodes from the historical dataset until convergence. The reward function is defined based on the comprehensive cost in (5), so that the learned policy directly reflects the trade-off among energy cost, carbon cost and imbalance penalties under realistic VPP operating conditions.

Table 3.

Key training parameter settings of the SAC algorithm.

To further quantify the scheduling performance of different DRL algorithms, we compare the conventional SAC, the SAC variant with LP constraints only (SAC-L), the proposed SAC-LAx, and three widely used baselines, namely PPO, DDPG and TD3. For each algorithm, training is carried out until convergence, and the performance indicators are computed over the test horizon. The key metrics include the convergence episode index, the long-term average reward, and the reward standard deviation, which jointly characterize the convergence speed, asymptotic performance, and training stability of each DRL algorithm.

As summarized in Table 4, SAC-LAx attains the highest average reward with relatively low reward variability and converges to its performance plateau at around 2500 episodes. SAC-L and SAC-LAx both achieve higher final rewards and smaller reward fluctuations than the vanilla SAC, demonstrating that enforcing feasibility via LP projection helps reduce oscillations and improve learning robustness. Although DDPG reaches a plateau very quickly, its asymptotic reward is much lower, indicating that the learned policy is clearly suboptimal. TD3 can eventually reach a reward level comparable to SAC-L, but it requires more training episodes and still exhibits noticeable fluctuations. PPO is able to approach the high-reward region as well, yet it does so very slowly and needs more than 8000 episodes to converge, making it substantially less sample-efficient than the proposed SAC-LAx.

Table 4.

Comparison of training performance under different DRL algorithms.

Figure 12 and Figure 13 illustrate the training reward curves of the considered DRL algorithms. Figure 12 compares the convergence trajectories of SAC, SAC-L and the proposed SAC-LAx under a unified reward mechanism, while Figure 13 shows the reward evolution of SAC-LAx against the benchmark algorithms PPO, DDPG and TD3. The detailed convergence speed, average reward and reward variability of these algorithms are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 12.

Comparison of reward curves before and after improvements of the SAC algorithm.

Figure 13.

Comparison of reward curves between SAC-LAx and other commonly used algorithms.

The power balance and heat balance results of the VPP on a typical day, solved by the SAC-LAx, are shown in Figure 14 and Figure 15, respectively.

Figure 14.

Power balance scheduling results of the VPP.

Figure 15.

Heat balance scheduling results of the VPP.

4.4. Impact of Carbon Trading and Scenario Analysis

To evaluate the economic impact of the prediction-enhanced scheduling strategy, Table 5 compares the main cost components of the VPP with and without the Ax-based prediction module. The results show that introducing the prediction module slightly reduces the total energy cost and the daily net operating cost. Specifically, the net total cost decreases from CNY 14,040.03 to CNY 14,032.35, mainly driven by a reduction in electricity purchase cost and a small increase in electricity sales revenue, while the natural gas and heat pump electricity costs remain within a similar range. Although the absolute difference at the scale of a single day is modest, it reflects a consistent improvement in operational efficiency under the same load and price conditions.

Table 5.

Cost comparison before and after algorithmic improvements.

Table 6 further investigates the effect of the carbon trading mechanism on emission costs. Under the proposed SAC-LAx scheduling, the total emission cost with carbon trading is CNY 129.32, compared with CNY 255.76 in the no-trading case, corresponding to a reduction of approximately 49%. This reduction mainly arises from the allocated carbon quotas for the CCPP, heat pump and battery, which allow part of the emissions to be offset at a lower cost. The emission quantities themselves remain almost unchanged between the two cases, indicating that the carbon trading mechanism primarily reshapes the economic burden associated with emissions rather than drastically altering the dispatch pattern.

Table 6.

Carbon emission costs of the VPP under different scenarios solved by SAC-LAx.

It should be noted that the above cost figures are obtained for a fixed historical day and a specific set of wind/PV and load trajectories. The main objective is to demonstrate the relative differences between scheduling strategies under identical conditions, rather than to provide a full statistical analysis over multiple datasets. The observed cost improvements at the daily scale are also influenced by the installed capacities of the VPP, the level of electricity and gas prices, and the limited elasticity of the test system. A more systematic assessment of the statistical significance of cost reductions, based on multiple typical days, seasons, regions and repeated training runs with different random seeds, will be carried out in future work.

In addition, the case study in this paper focuses on a representative operating scenario and the comparison between “with” and “without” carbon trading. Other important operating conditions—such as high- and low-renewable generation periods, extreme peak-load days, and alternative tariff structures—are not explicitly simulated here due to space and data constraints. Extending the proposed framework to these diverse scenarios will be an important direction for future research, in order to further examine the robustness and generalization capability of SAC-LAx in practical VPP applications.

The detailed power and heat balance results on the typical test day, shown in Figure 14 and Figure 15, confirm that the SAC-Lax-based scheduling strategy can satisfy the electric and thermal demand at each time step while respecting the operational constraints of the CCPP, battery, heat pump and thermal storage units.

4.5. Computational Complexity and Time Consumption

The proposed SAC-LAx framework combines the Attention–xLSTM prediction module, the SAC-based policy network and the LP-constraint module. From a computational perspective, the dominant cost in the prediction stage comes from the Ax model, whose complexity is comparable to that of a deep LSTM with several stacked layers. The DRL stage is dominated by the forward and backward passes of the Actor–Critic networks, as in conventional SAC, while the additional LP projection is formulated as a small-scale convex optimization problem with a moderate number of decision variables and linear constraints.

In this study, both the prediction model and the SAC-LAx agent are trained offline on historical data. The Attention–xLSTM is first trained to convergence using the training and validation sets, and then kept fixed during DRL training. The SAC-LAx agent is trained by repeatedly sampling 24 h episodes from the historical dataset until the reward curves stabilize, as illustrated in Section 4.3. Although the offline training of Ax and SAC-LAx requires more computation than that of conventional LSTM and SAC, respectively, it is performed only once for a given VPP configuration and can be executed on standard workstation hardware without real-time constraints.

During online operation, the computational burden of the proposed framework is much lower. At the beginning of each day, the trained Attention–xLSTM performs multi-step forecasting of loads and renewable outputs for the next 24 h, and each forward prediction pass only involves matrix multiplications and attention operations with negligible time compared to the one-hour scheduling interval. At every decision step, the SAC-LAx agent computes the raw action using a single forward pass of the Actor network, and the LP-constraint module solves a small convex projection problem to obtain a feasible action. The resulting online computation time is therefore easily compatible with practical VPP scheduling requirements, confirming the feasibility of applying the SAC-LAx framework in real-time or day-ahead dispatch scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposed an improved Soft Actor–Critic-based scheduling framework, SAC-LAx, for intelligent operation of virtual power plants under high renewable penetration and carbon-neutrality requirements. The framework combines an Attention–xLSTM prediction module with an in-loop Linear Programming constraint module, so that the DRL agent can simultaneously benefit from multi-step forecasting and safety-aware action correction while interacting with a detailed electric–thermal VPP model and a carbon trading mechanism.

The main findings can be summarized as follows.

- On the forecasting side, the Ax module significantly enhances the accuracy of day-ahead electric load prediction. Compared with classical LSTM and GRU models, the Ax-based predictor reduces the from 4.51% and 5.77% to 2.88%, providing a more reliable look-ahead state for the subsequent DRL scheduling layer.

- On the scheduling side, the proposed SAC-LAx algorithm improves both convergence behavior and policy quality. In the campus-scale integrated electric–thermal VPP case, SAC-LAx attains an average reward of about 1440 and converges within roughly 2500 training episodes, outperforming vanilla SAC and other popular DRL baselines such as DDPG, TD3 and PPO. The LP-constraint module effectively suppresses invalid exploration and enforces feasibility, while the Ax-based state augmentation accelerates learning and enhances stability.

- From the perspective of economic and environmental performance, the SAC-LAx framework reduces the daily net operating cost and, under the carbon trading mechanism, lowers the total carbon emission cost by about 49% compared with the no-trading scenario, while maintaining electric–thermal power balance. Although the absolute cost reduction per day appears modest, it translates into non-negligible annual savings and carbon-cost reductions for long-term VPP operation, demonstrating the practical value of integrating prediction enhancement and LP-based safety constraints into DRL-based scheduling.

Despite these promising results, several limitations remain and motivate future research. First, the case study is conducted on a single campus-scale VPP with typical daily profiles, and the cost improvements are evaluated under one fixed set of historical wind/PV and load trajectories. A formal statistical analysis of the cost reduction, based on multiple typical days, seasons, regions and repeated training runs with different random seeds, is left as future work. Second, the present study focuses on a representative operating scenario and on the comparison between “with” and “without” carbon trading. Other important operating conditions—such as high- and low-renewable generation periods, extreme peak-load days and alternative tariff structures—have not been explicitly simulated and will be further examined to assess the robustness of SAC-LAx under diverse system conditions. Third, the current work adopts a single-agent DRL formulation; in future, multi-agent VPP operation and coordination among multiple aggregators or microgrids could be modeled using multi-agent DRL to capture strategic interactions and network constraints. Finally, the present model considers day-ahead prices and a relatively simplified carbon trading scheme, incorporating real-time pricing uncertainty, demand response programs and more complex market rules, as well as adaptive or safe DRL mechanisms such as online parameter adaptation, risk-sensitive objectives or robust training against forecast errors, representing promising directions to further enhance the reliability and resilience of SAC-LAx in practical large-scale deployments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; Methodology, J.Z.; Software, J.Z.; Validation, J.Z.; Formal analysis, J.Z.; Data curation, K.Z.; Writing—original draft, J.Z.; Writing—review & editing, J.Z.; Supervision, Y.S.; Project administration, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, and the Article Processing Charge (APC) was borne by the authors personally.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to being internal data of the university, which involves exclusive information related to the institution’s research and is not suitable for public release.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

The main symbols and parameters used in this paper are summarized as follows:

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| Time index and length of one time step | ||

| (positive for import) | ||

| Charging/discharging efficiencies of the battery | – | |

| Natural gas price and carbon price | ||

| Total energy cost and carbon emission cost over the scheduling horizon | ||

| Net market revenue and overall net operating cost | ||

| – | ||

| – | ||

| Discount factor and entropy temperature coefficient in SAC | – |

References

- Jin, W.; Wang, P.; Yuan, J. Key Role and Optimization Dispatch Research of Technical Virtual Power Plants in the New Energy Era. Energies 2024, 17, 5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, W.-J.; Lin, Z.; Shamash, Y.A. Virtual Power Plants for Grid Resilience: A Concise Overview of Research and Applications. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Kaur, G. Artificial intelligence, Internet of Things, and communication networks. In Artificial Intelligence to Solve Pervasive Internet of Things Issues; Kaur, G., Tomar, P., Tanque, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Xhafa, F. Towards Artificial Intelligence Internet of Things (AIoT) and Intelligent Edge: The intelligent edge is where action is!: Editorial preface. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, Y.; Seshuraju, P.; Khaparde, S.A.; Joshi, R.K. Flexible Open Architecture Design for Power System Control Centers. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2011, 33, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozbehani, M.M.; Heydarian-Forushani, E.; Hasanzadeh, S.; Ben Elghali, S. Virtual Power Plant Operational Strategies: Models, Markets, Optimization, Challenges, and Opportunities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhou, B.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Mao, T.; Huang, X. Architecture and Function Design of Virtual Power Plant Operation Management Platform. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia (I&CPS Asia), Shanghai, China, 8–11 July 2022; pp. 1771–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Huang, H.; He, Y.; Xu, M.; Yang, Y.; Qiao, Y. Optimal scheduling method of virtual power plant based on model predictive control. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Energy, Power and Electrical Engineering (EPEE), Wuhan, China, 15–17 September 2023; pp. 1439–1443. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N.; Zhu, L.; Wang, B.; Fu, R.; Qi, L.; Jiang, X.; Sun, C. A Master–Slave Game-Based Strategy for Trading and Allocation of Virtual Power Plants in the Electricity Spot Market. Energies 2025, 18, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cao, B.; Sun, M.; Zhu, Y. Optimal scheduling strategy of virtual power plant based on bi-level master–slave game. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Power Engineering (ICPE), Shanghai, China, 13–15 December 2024; pp. 690–696. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Li, F.; Zhang, D.; Shan, L.; Zhu, H.; Du, P.; Jiang, M.; Goh, H.H.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Huang, C.; et al. Intelligent Load Forecasting Technologies for Diverse Scenarios in the New Power Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, C. Electricity, Heat, and Gas Load Forecasting Based on Deep Multitask Learning in Industrial-Park Integrated Energy System. Entropy 2020, 22, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadimi, R.; Goto, M. A Novel Decision Support System for Enhancing Long-Term Forecast Accuracy in Virtual Power Plants Using Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Networks. Appl. Energy 2025, 382, 125273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Z. Urban Parking Demand Forecasting Using xLSTM-Informer Model. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 80601–80611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, C. Review and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence Technology in Virtual Power Plants. Energies 2025, 18, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Wu, H.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. An Optimal Scheduling Framework for Integrated Energy Systems Using Deep Reinforcement Learning and Deep Learning Prediction Models. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 4620–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aklo, N.J.; Almousawi, A.Q.; Hammood, H.; Al-Ibraheemi, Z.A.M. Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient-Based Energy Storage Control and Distribution between Two Microgrids. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 13, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Guan, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, N.; Maharjan, S.; Ohtsuki, T. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Economic Dispatch of Virtual Power Plant in Internet of Energy. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6288–6301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhan, C.; Ren, X.; Lü, S. Proximal Policy Optimization with Reward-Based Prioritization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 283, 127659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Nian, X.; Deng, X.; Yang, Z. Optimal energy system scheduling based on safe deep reinforcement learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Electrical Automation and Artificial Intelligence (ICEAAI), Guangzhou, China, 10–12 January 2025; pp. 599–603. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Optimal Scheduling Strategy of Electricity and Thermal Energy Storage Based on Soft Actor-Critic Reinforcement Learning Approach. J. Energy Storage 2024, 92, 112084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Yan, L.; Dai, X.; Zhu, X.; Hagenmeyer, V.; Zhai, J. Low-Carbon Energy Management for Networked Multi-Energy Microgrids Using Multi-Agent Soft Actor-Critic Algorithm. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 43, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, G.W.; Gong, D.H.; Xuan, L.F.; He, F.W.; Wan, X.L.; Zhou, D.G. Bi-Level Game Strategy for Virtual Power Plants Based on an Improved Reinforcement Learning Algorithm. Energies 2025, 18, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; Chang, W.G.; Yang, Q. Deep reinforcement learning based hierarchical energy management for virtual power plant with aggregated multiple heterogeneous microgrids. Appl. Energy 2025, 382, 125333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Cui, W.; Li, G.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Tai, Y. Intelligent Scheduling of Virtual Power Plants Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 84, 861–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).