Investigation of Hot Spot Migration in an Annular Combustor Using the SAS Turbulence Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Method

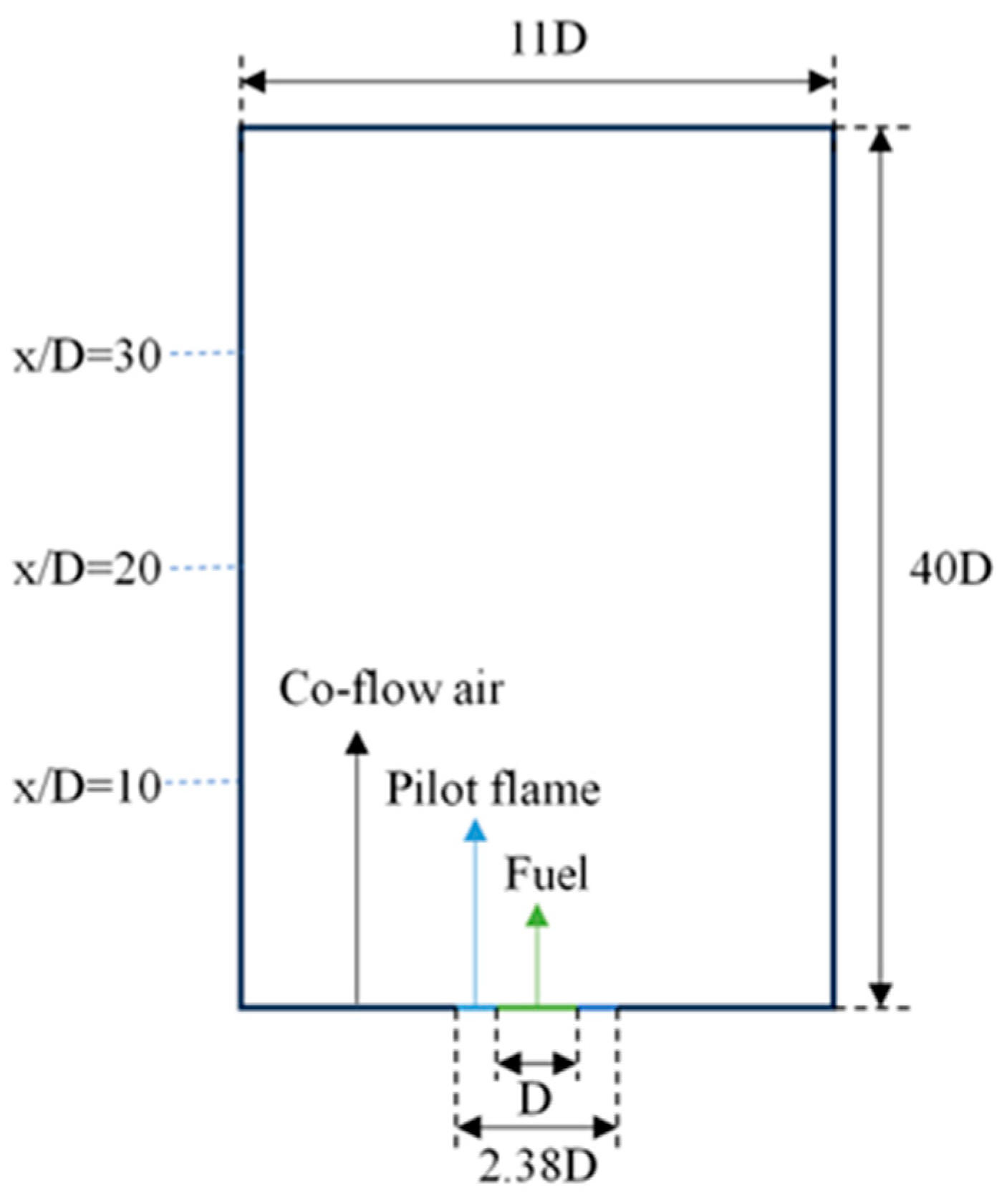

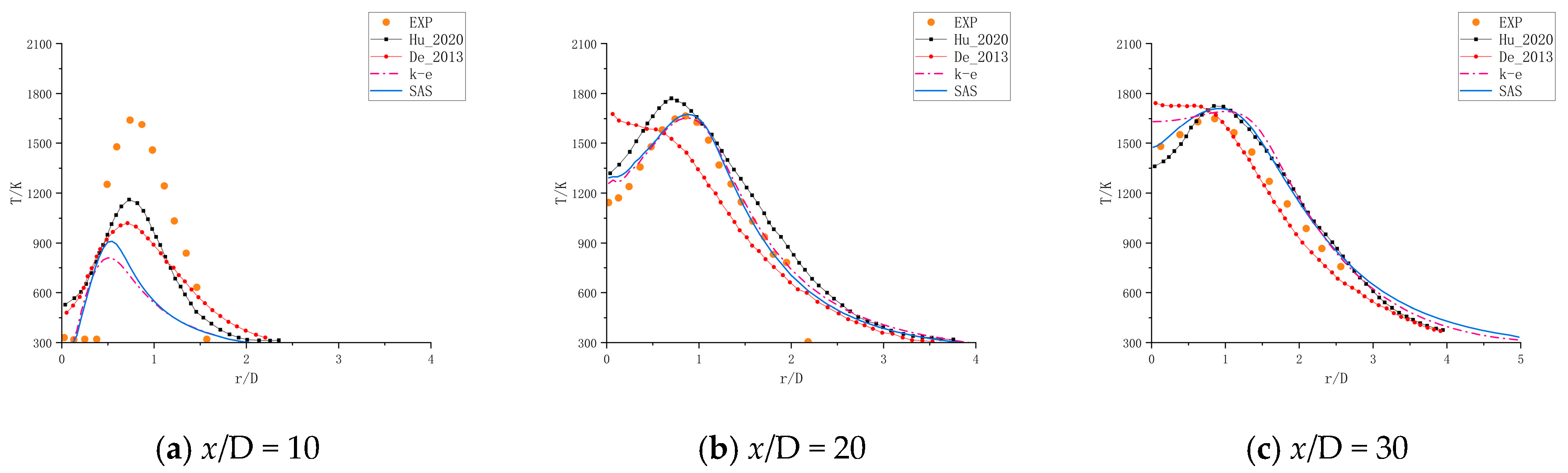

3. Validation of Numerical Simulation

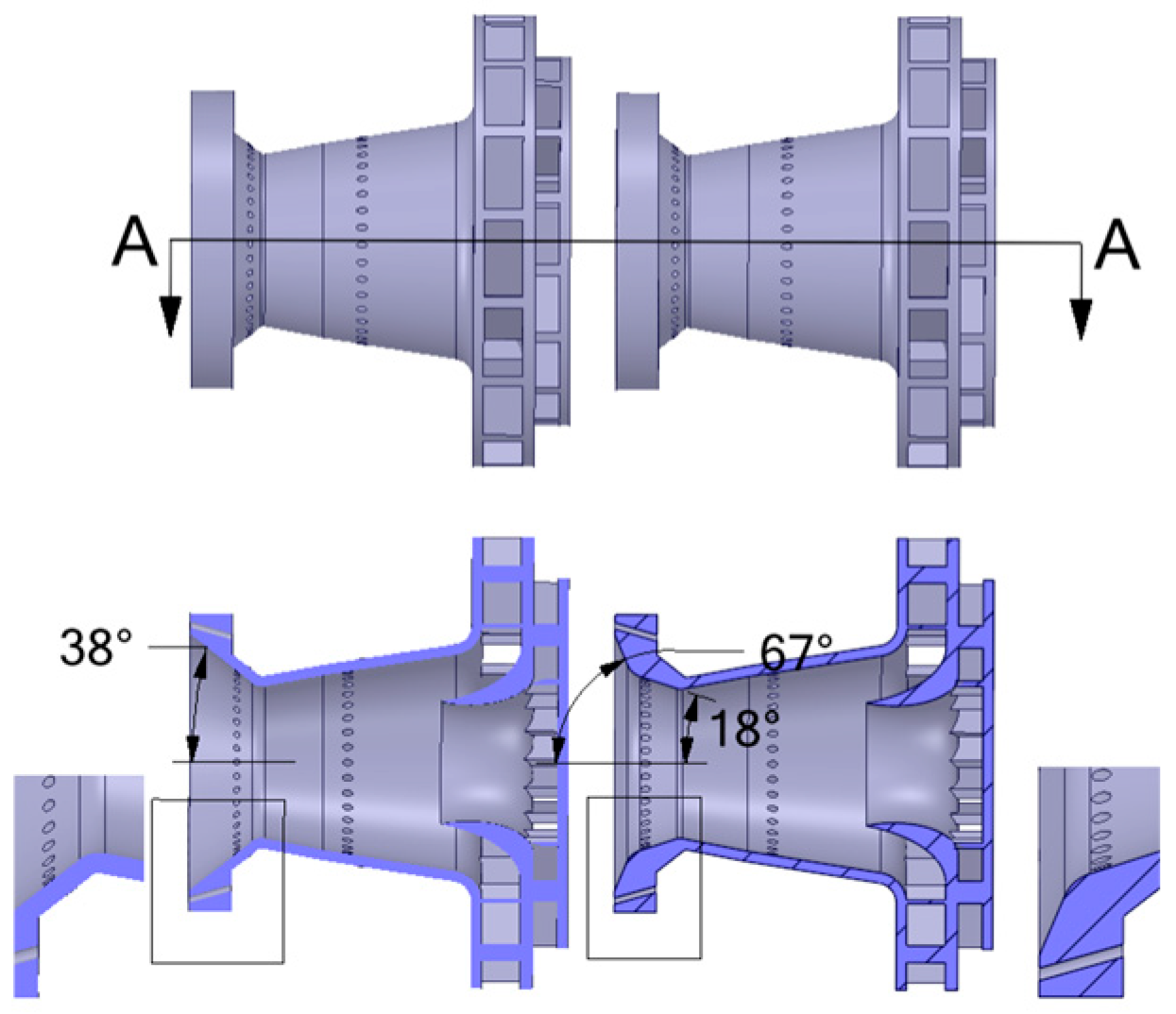

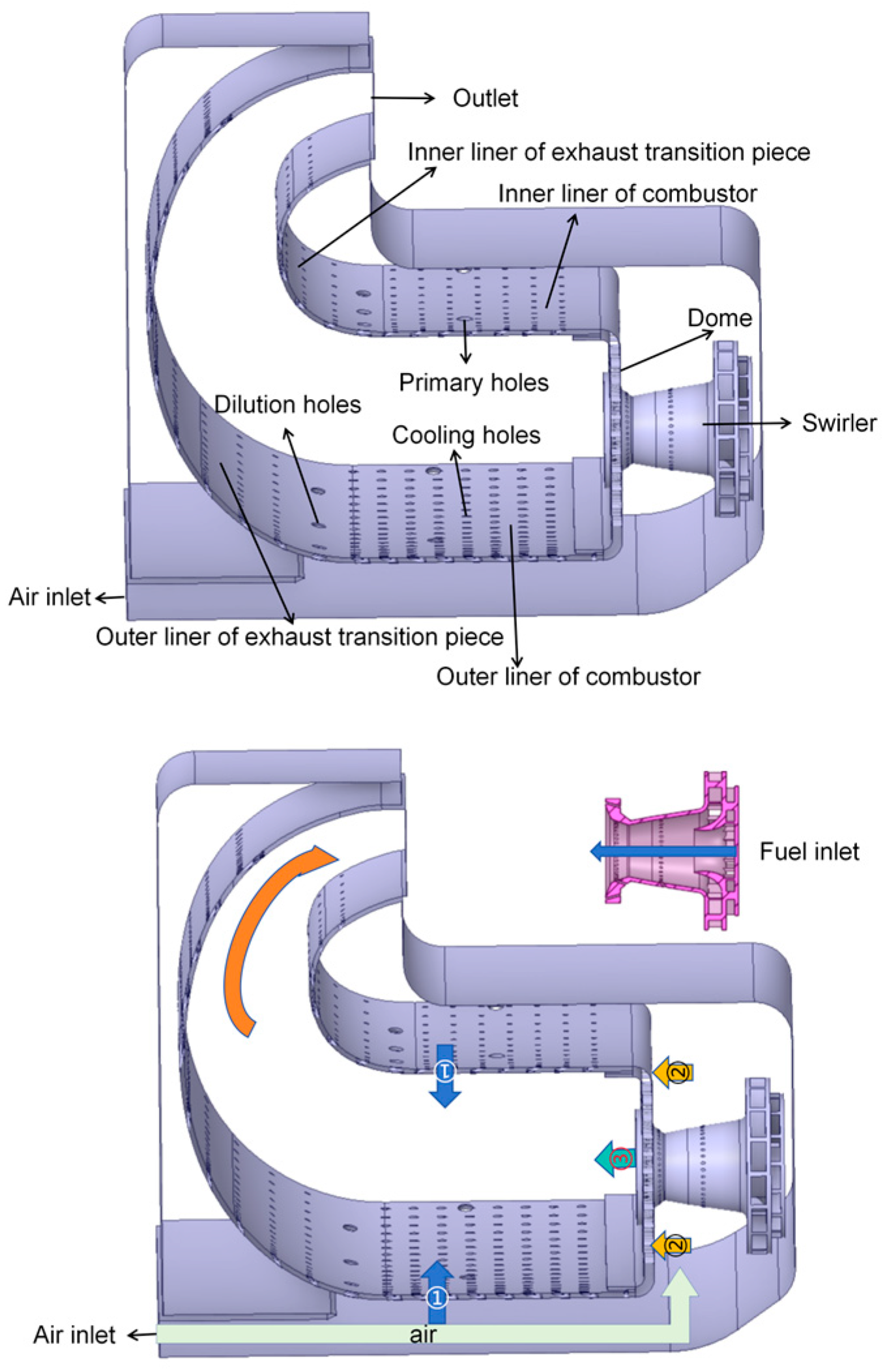

4. Numerical Simulation of a Practical Annular Combustor

4.1. Problem Description

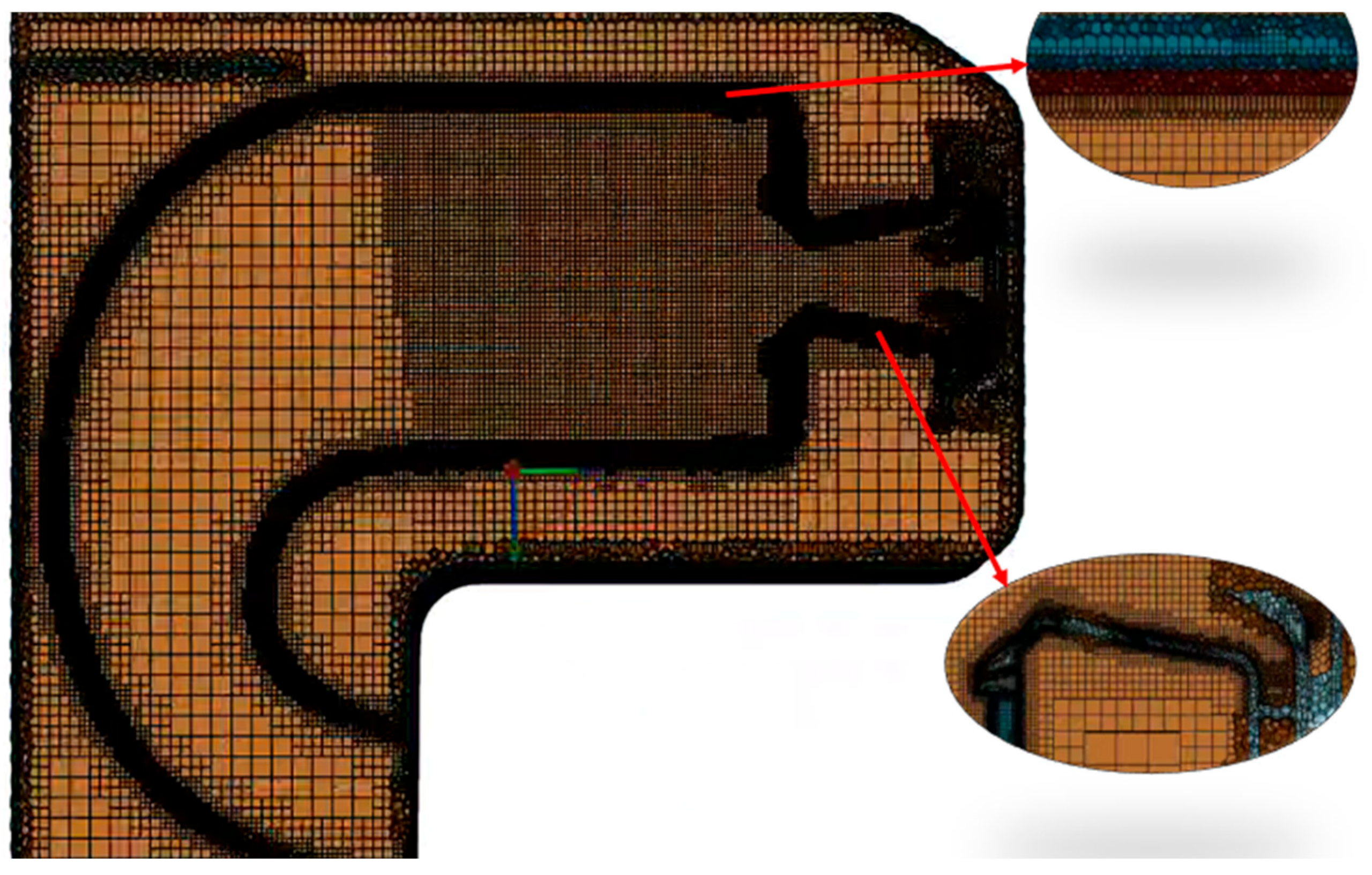

4.2. Simulation Setup and Mesh Generation

4.3. Results and Discussion

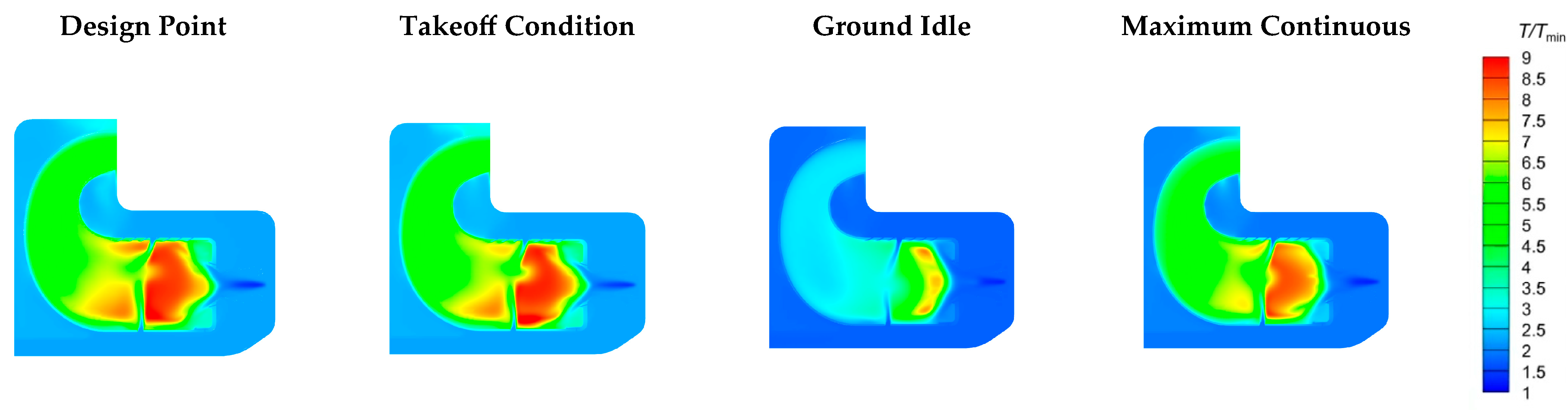

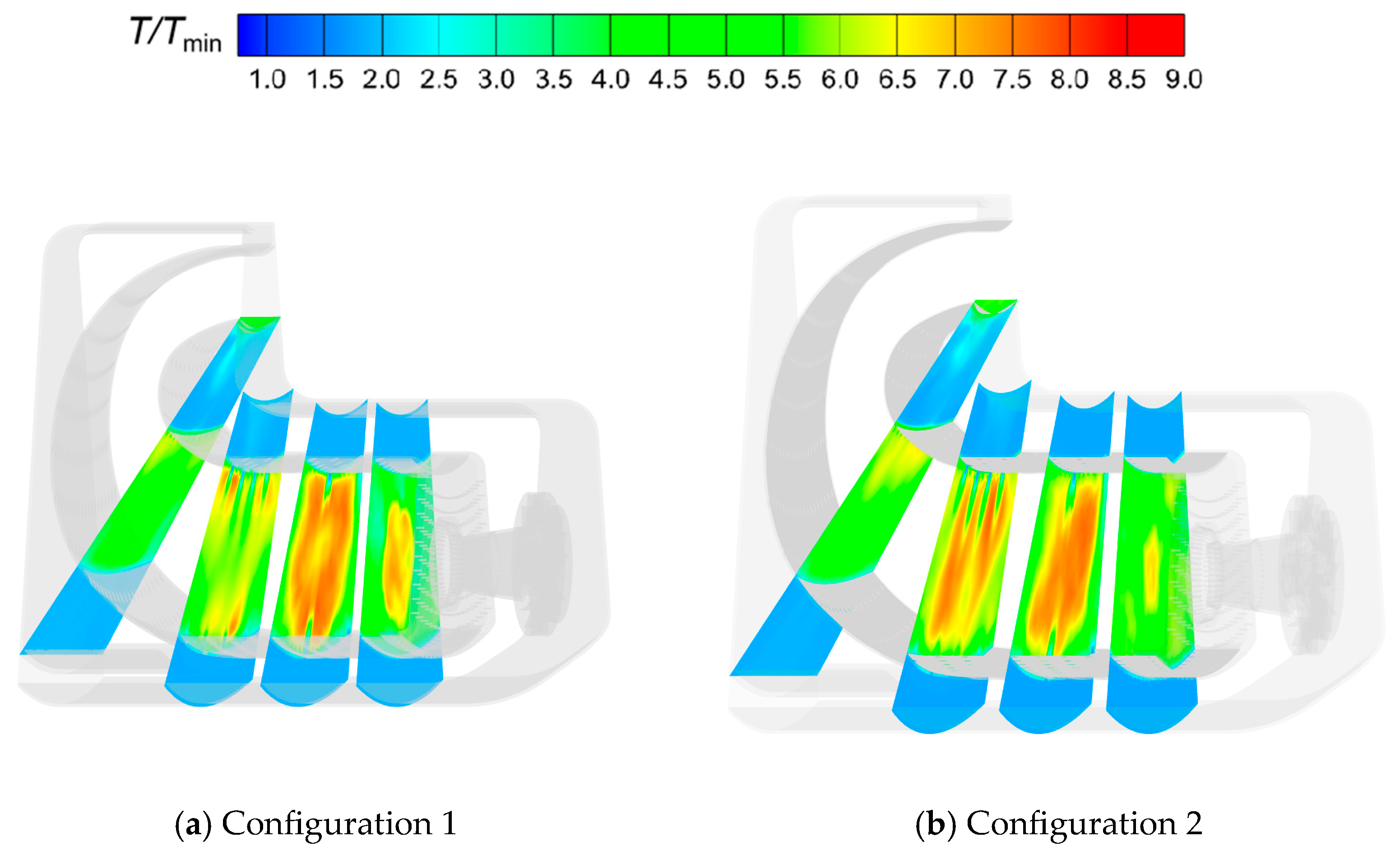

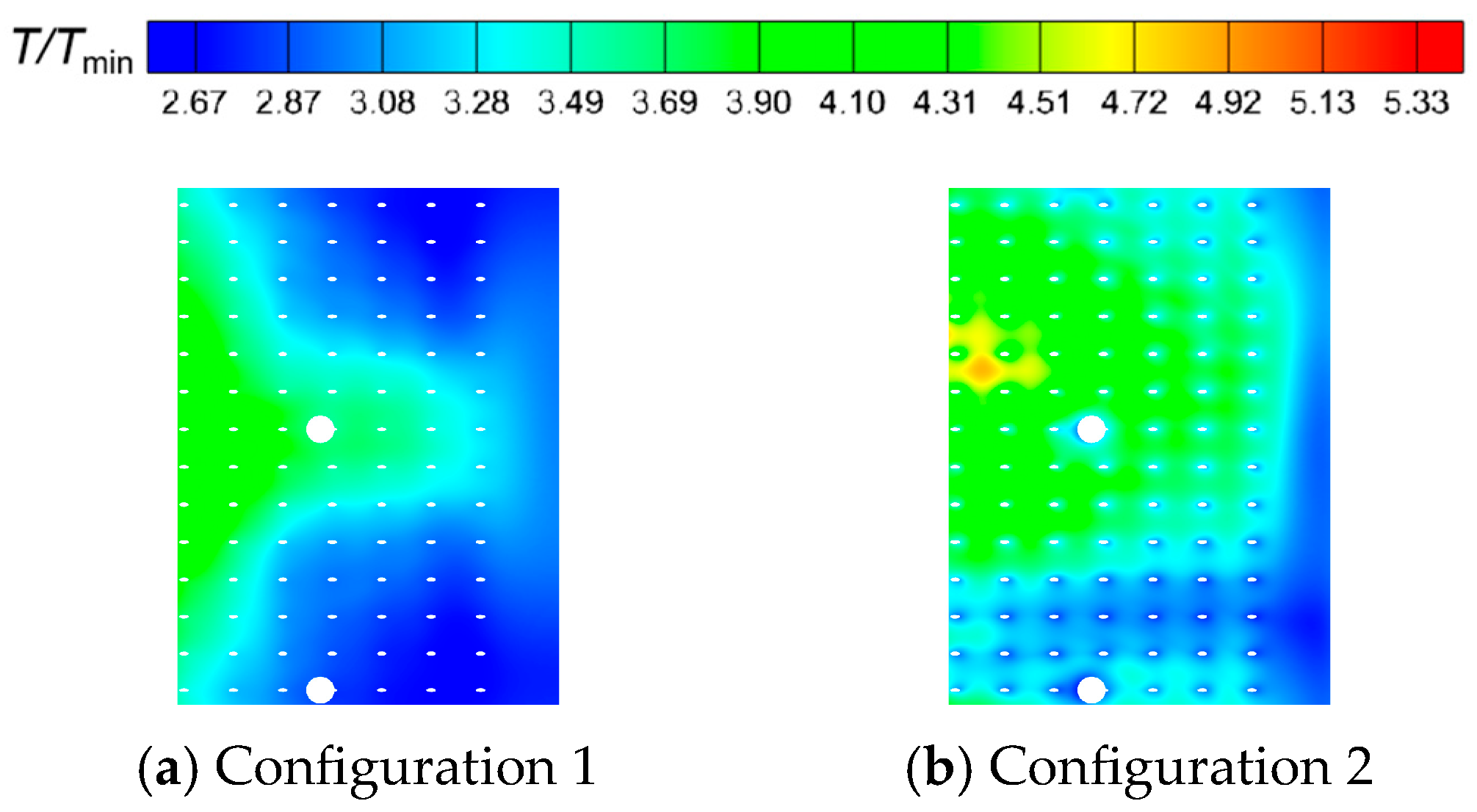

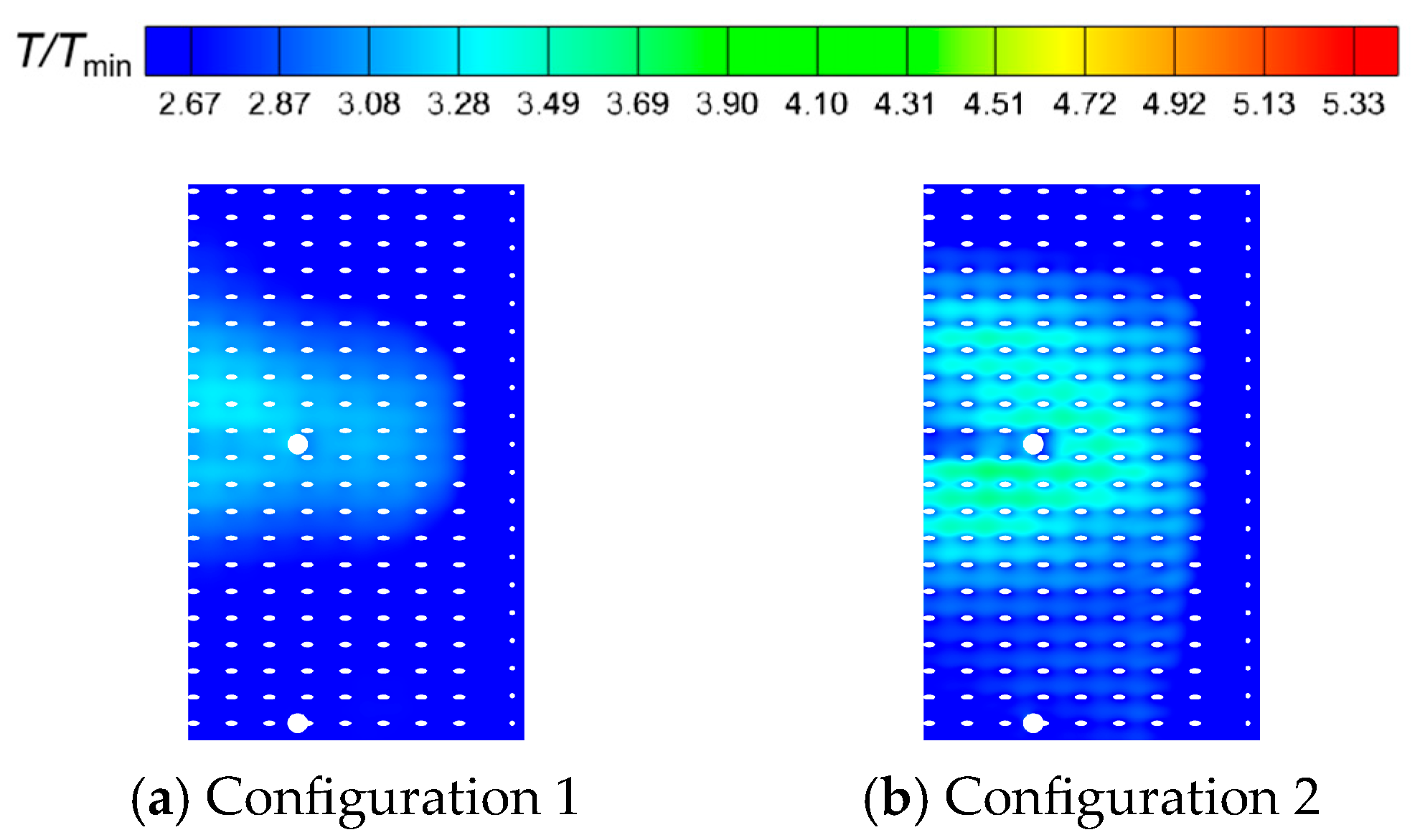

4.3.1. Temperature Distribution Under Different Operating Conditions

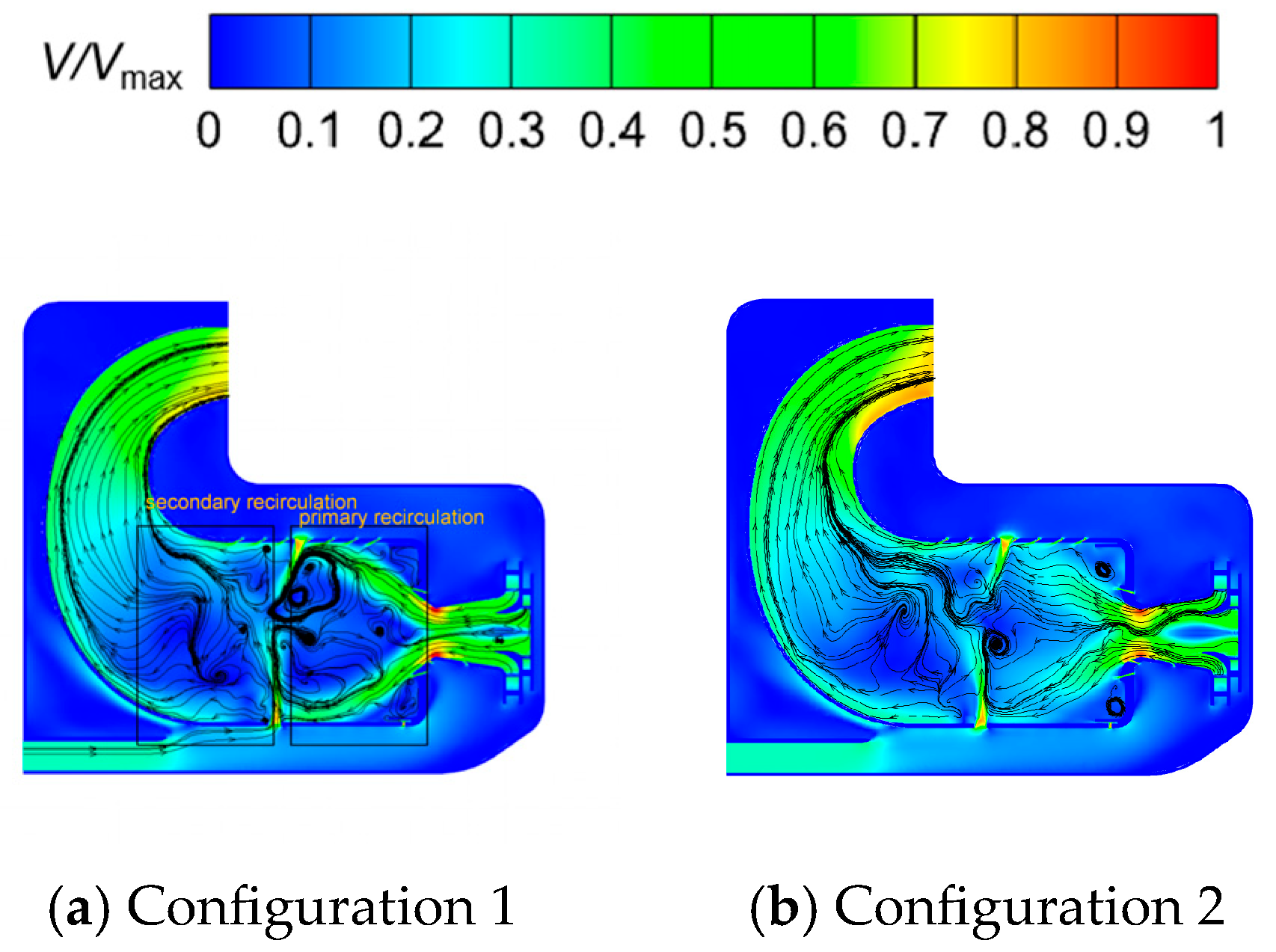

4.3.2. Time-Averaged SAS Analysis

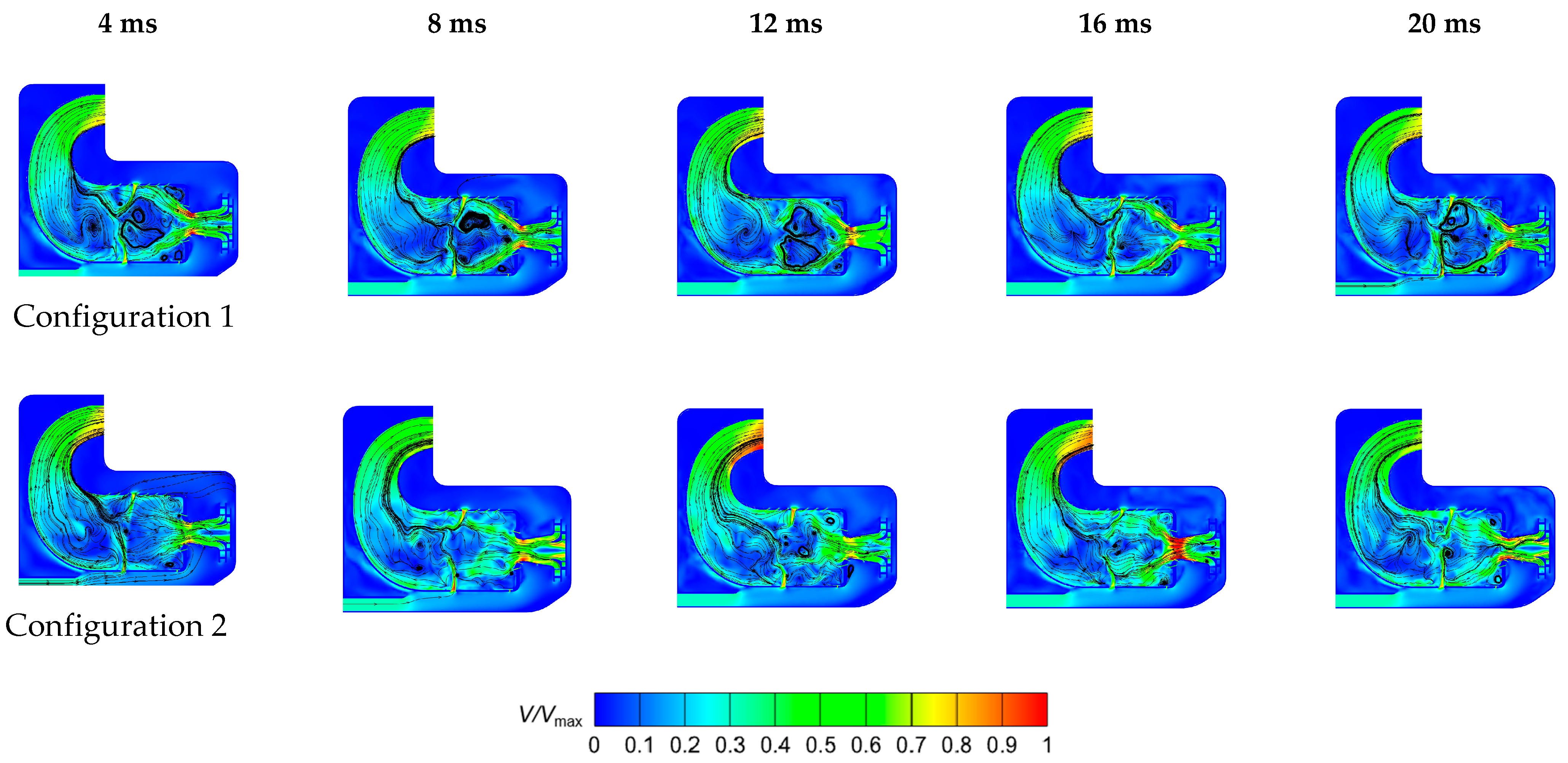

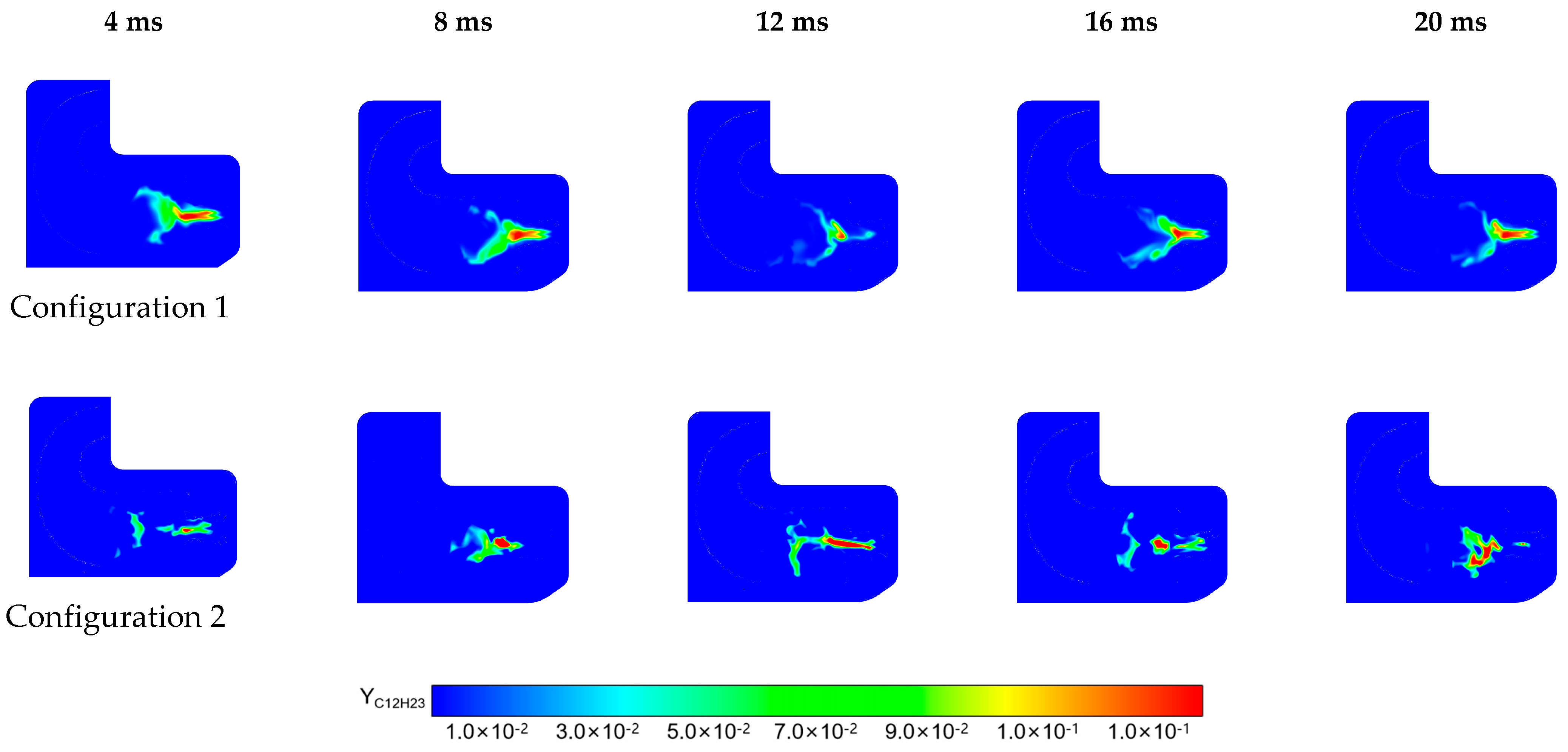

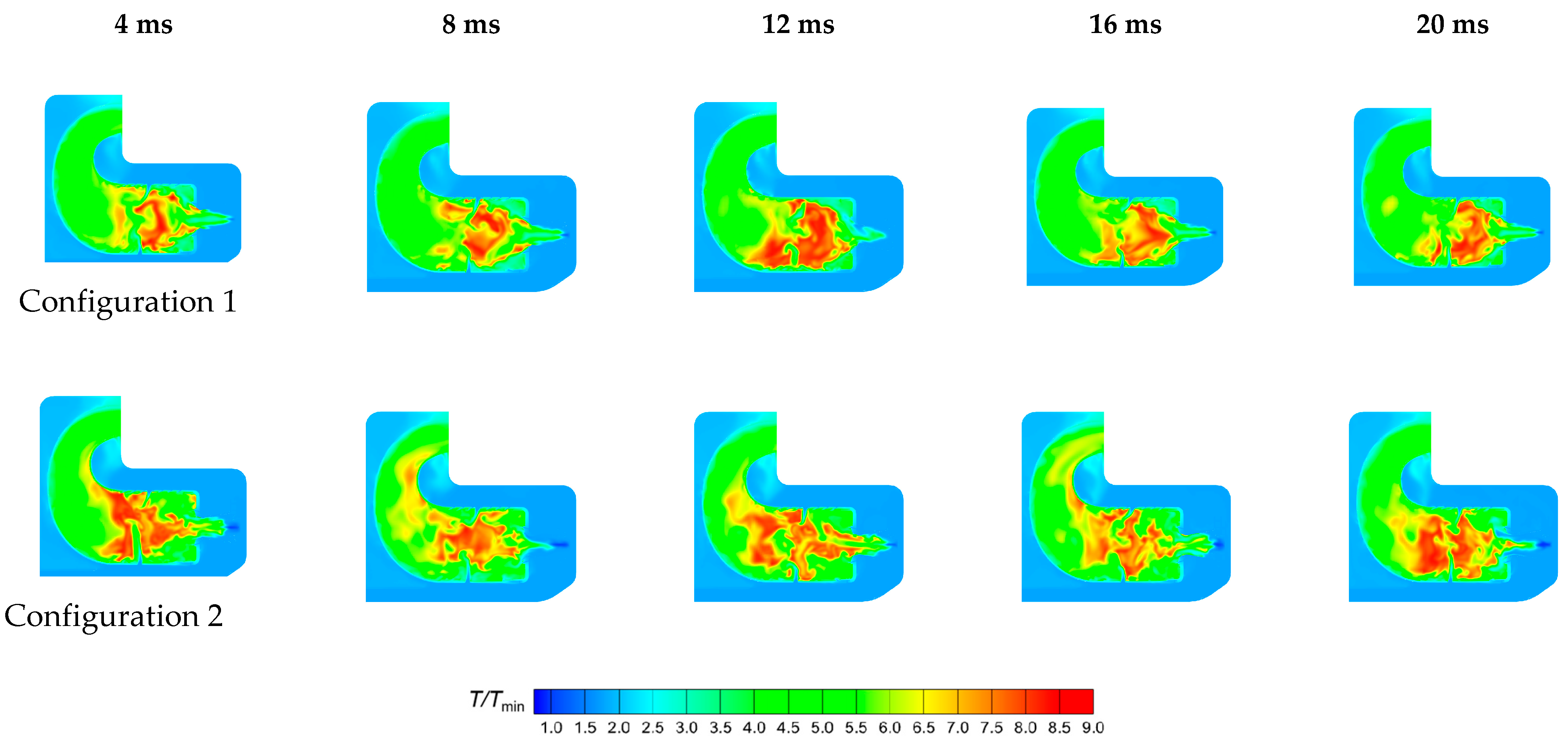

4.3.3. Instantaneous Analysis

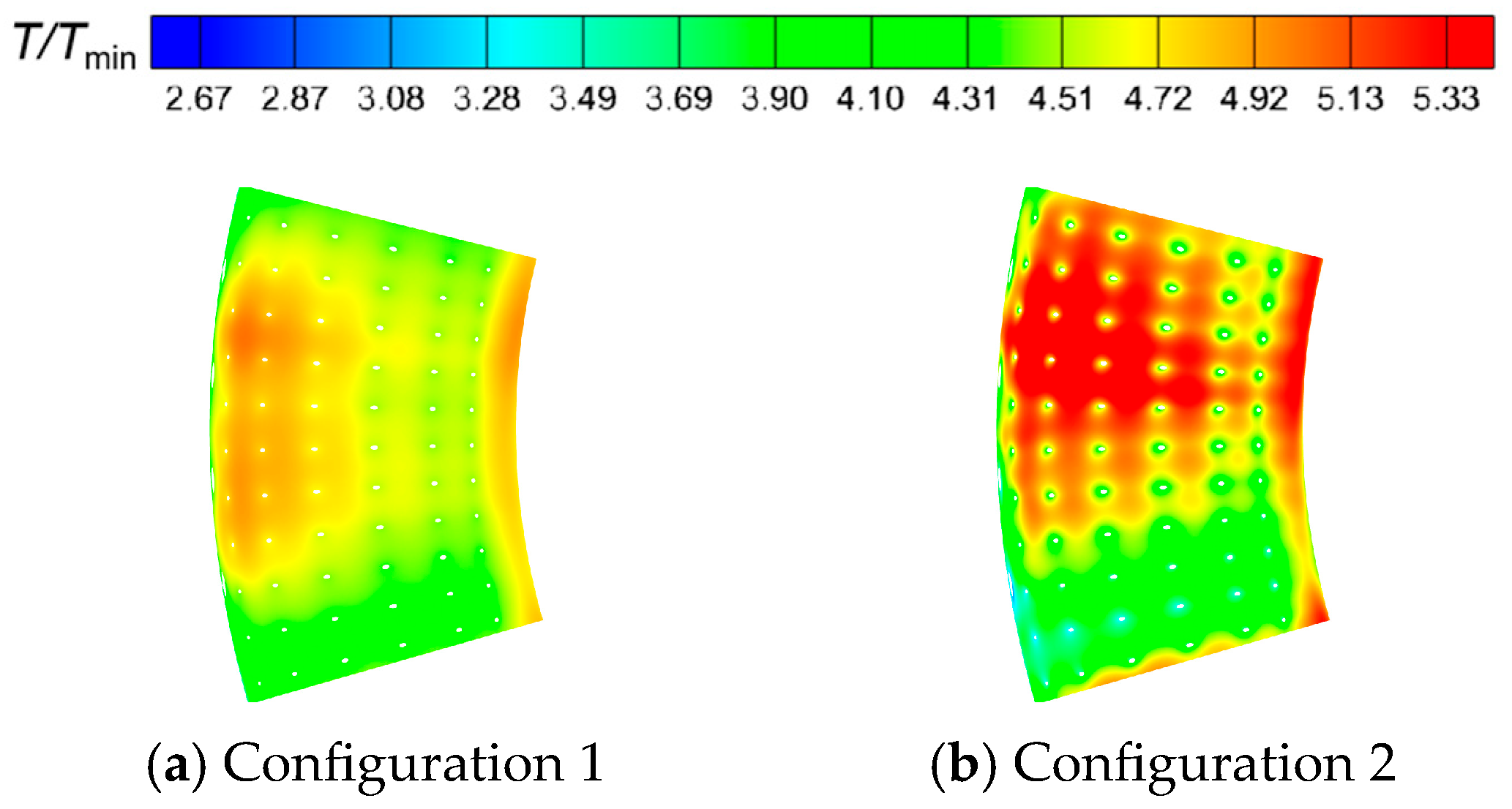

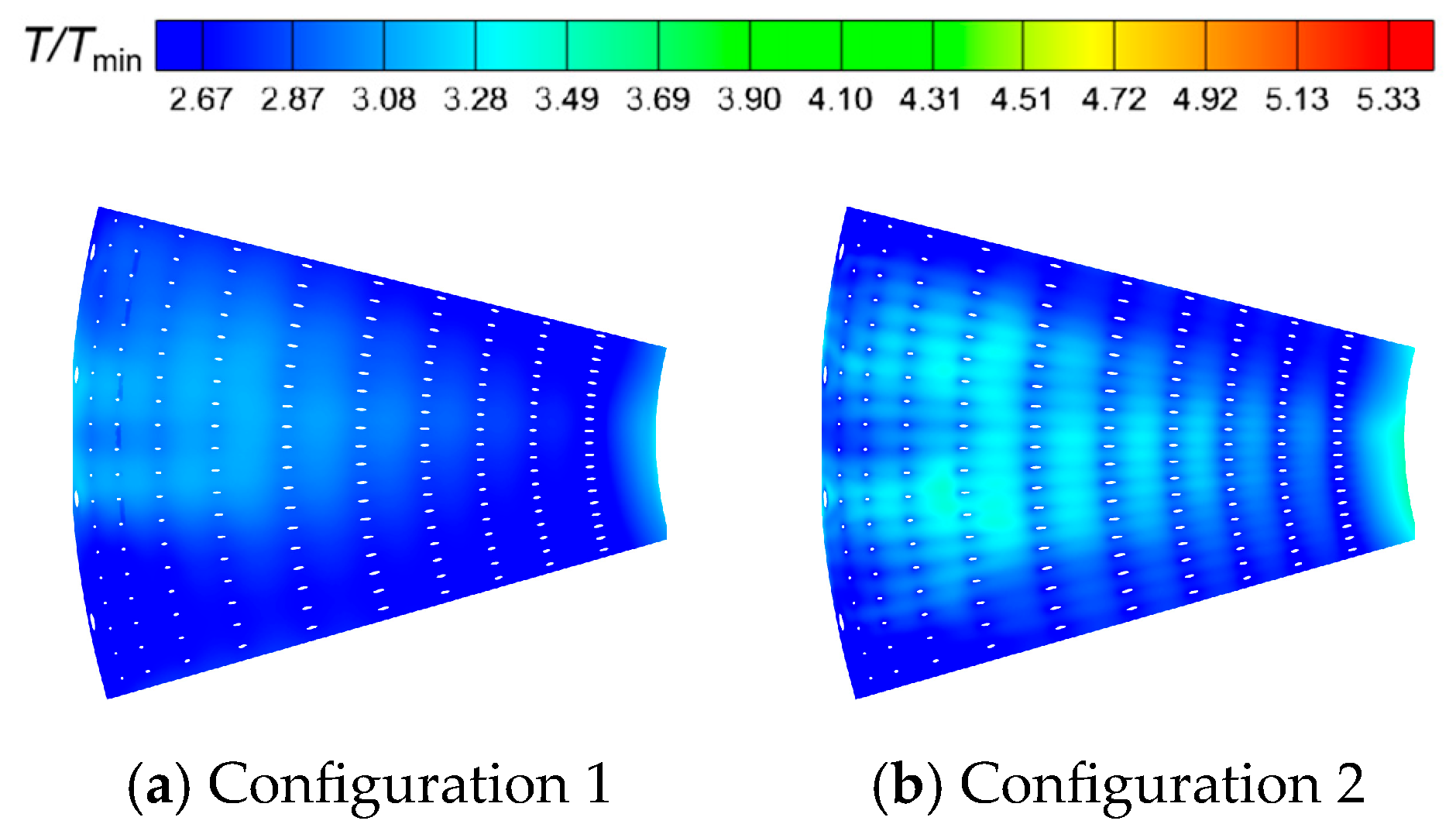

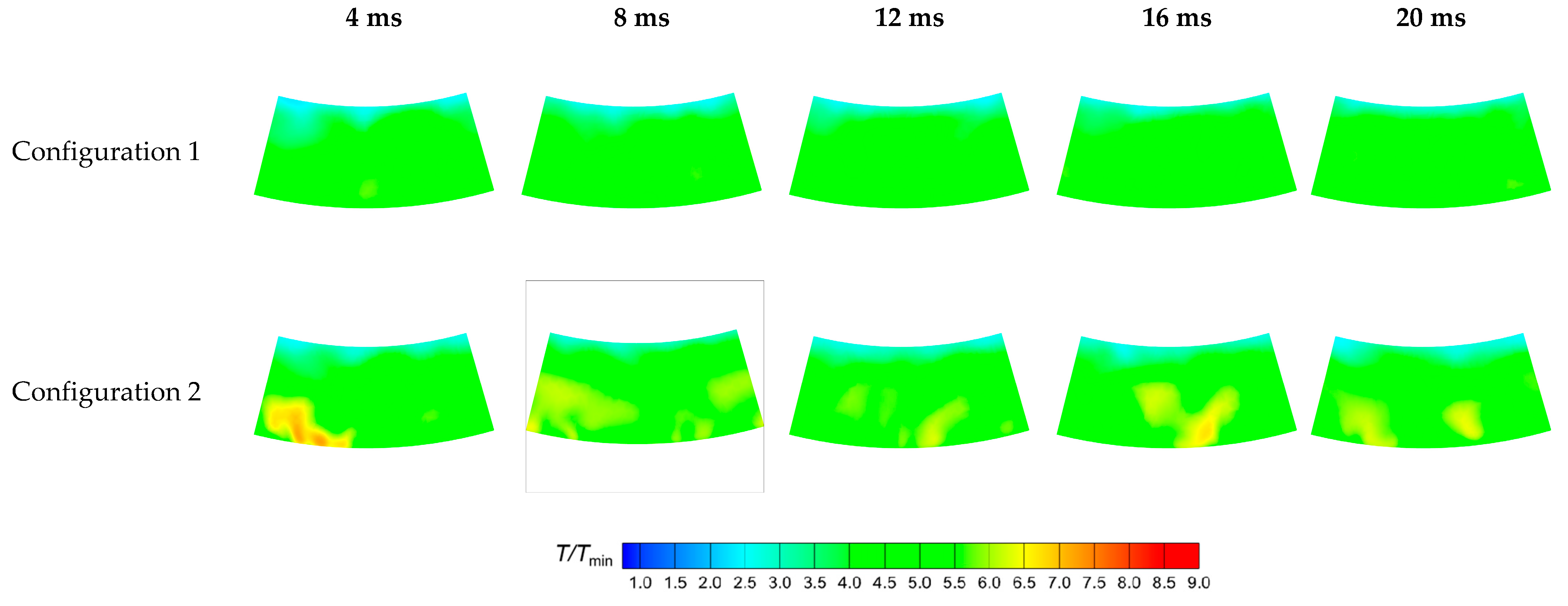

4.3.4. Migration of Hot Spots on Wall Surfaces

5. Conclusions

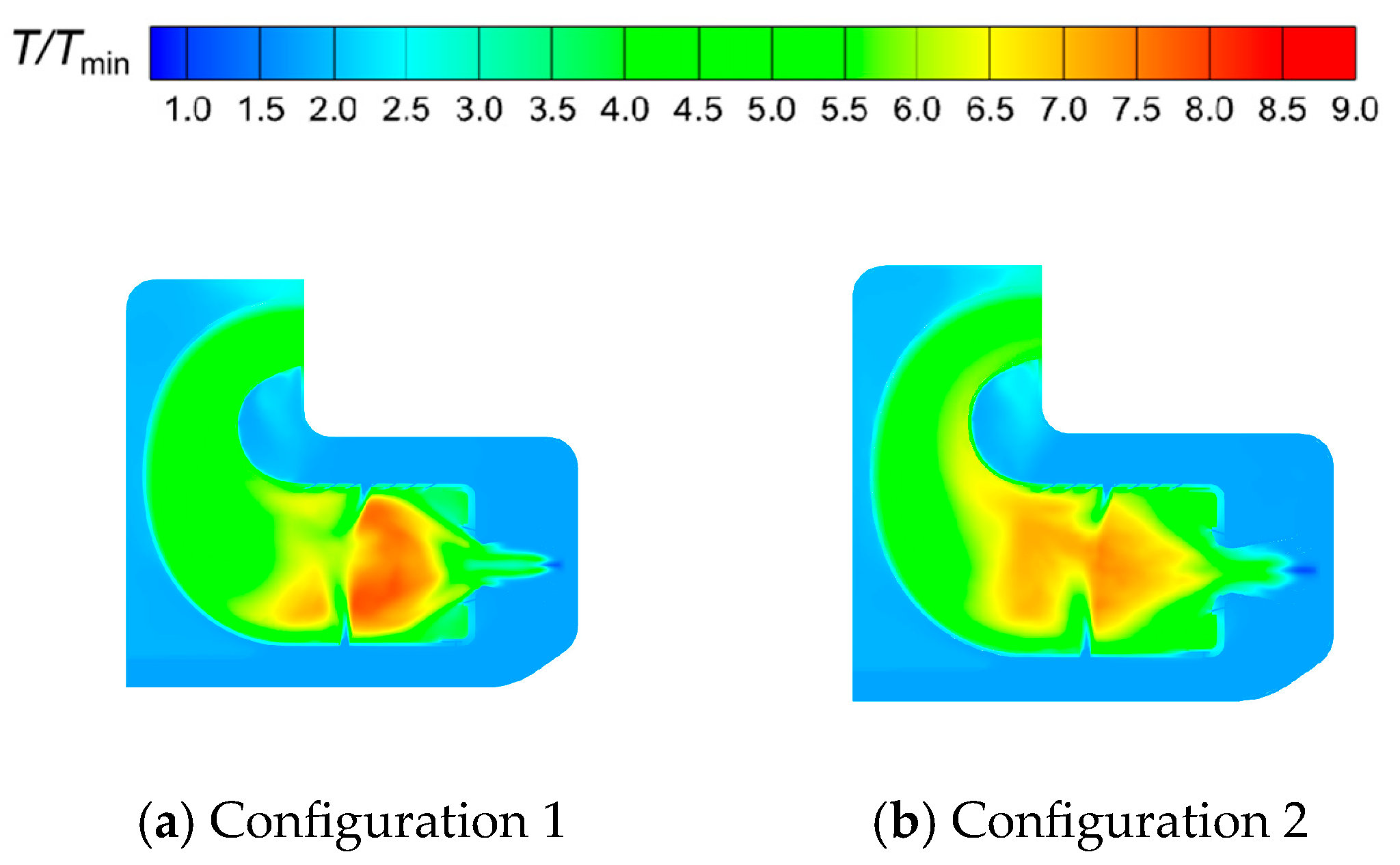

- In combustion chambers equipped with two different swirler configurations, the high-speed jets from the primary holes divide the high-temperature gas into two distinct regions. In the fluid domain, the high-temperature region in Configuration 1 is mainly concentrated within the primary recirculation zone, whereas in Configuration 2, high-temperature regions are extensively present in both the primary and secondary recirculation zones.

- In Configuration 1, the two symmetric vortex structures within the primary recirculation zone are more stable. Cool air entering through the cooling holes effectively envelops the high-temperature gas, resulting in lower hot spot temperatures on the combustor liner. In Configuration 2, fuel droplets and air exiting the swirler possess higher axial velocities. The vortex structures in the primary recirculation zone are less stable, and the jet from the primary holes induces strong disturbances in the fuel distribution, leading to higher wall temperatures.

- The temperature distribution at the outlet of Configuration 1 is relatively uniform, with no obvious hot spots. In Configuration 2, the axial extent of high-temperature gas within the combustion chamber is larger, making hot spots at the outlet more pronounced. These hot spots primarily occur within the inner half of the outlet region and migrate circumferentially.

- A larger swirler outlet diffusion angle promotes the formation of wide, low-momentum recirculation zones, which benefits flame stabilization and the development of a broad high-temperature region. The resulting lower outlet velocity leads to milder mixing, with hot spots located closer to the inner liner of combustor. Conversely, a smaller diffusion angle favors the generation of a compact, high-velocity central jet. Near the center axis, local high-temperature, strong recirculation zones form, and the interaction between the high-speed jet and surrounding low-speed gas creates intense shear layers, enhancing turbulence and accelerating mixing, which shifts hot spots closer to the jet region.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, Z.; Guo, H.; Gong, S.; Xu, H. Novel ceramic layer materials for thermal barrier coatings. J. Aeronaut. Mater. 2018, 38, 10–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Li, R. Current status and development of thermal barrier coatings for aero-engine turbine blades. Ordnance Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 47, 121–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Lavallée, Y.; Hess, K.U.; Kueppers, U.; Cimarelli, C.; Dingwell, D.B. Volcanic ash melting under conditions relevant to ash turbine interactions. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ding, K.; Dai, H. Failure analysis and reliability assessment of a type of aero-engine combustion chamber thermal barrier coatings. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 53, 103886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingel, C.; Binder, N.; Bousquet, Y.; Boussuge, J.F.; Buffaz, N.; Le Guyader, S. Influence of RANS Turbulent Inlet Set-Up on the Swirled Hot Streak Redistribution in a Simplified Nozzle Guide Vane Passage: Comparisons with Large-Eddy Simulations. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2022: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 13–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Gupta, S.; Kuo, T.W.; Gopalakrishnan, V. RANS and Large Eddy Simulation of Internal Combustion Engine Flows—A Comparative Study. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2014, 136, 051507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, Z. Numerical prediction of heat transfer characteristics on a turbine nozzle guide vane under various combustor exit hot-streaks. Heat Transf. 2021, 51, 976–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, C.J. Large-eddy simulations for internal combustion engines—A review. Int. J. Engine Res. 2011, 12, 421–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R.; Egorov, Y. The Scale-Adaptive Simulation Method for Unsteady Turbulent Flow Predictions. Part 1: Theory and Model Description. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2010, 85, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreini, A.; Bacci, T.; Insinna, M.; Mazzei, L.; Salvadori, S. Modelling strategies for the prediction of hot streak generation in lean burn aeroengine combustors. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 79, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, Y.; Menter, F.R.; Lechner, R.; Cokljat, D. The Scale-Adaptive Simulation Method for Unsteady Turbulent Flow Predictions. Part 2: Application to Complex Flows. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2010, 85, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.; Kuntz, M.; Bender, R. A Scale-Adaptive Simulation Model for Turbulent Flow Predictions. In Proceedings of the 41st Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, Nevada, 6–9 January 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounder, J.D.; Kourmatzis, A.; Masri, A.R. Turbulent piloted dilute spray flames: Flow fields and droplet dynamics. Combust. Flame 2012, 159, 3372–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, R.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.P. Large Eddy Simulation of a Turbulent Dilute Ethanol Flame Using the Two-Phase Spray Flamelet Generated Manifold Approach. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2022, 197, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Kim, S.H. Large eddy simulation of dilute reacting sprays: Droplet evaporation and scalar mixing. Combust. Flame 2013, 160, 2048–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Kai, R.; Kurose, R.; Gutheil, E.; Olguin, H. Large eddy simulation of a partially pre-vaporized ethanol reacting spray using the multiphase DTF/flamelet model. Int. J. Multiphase Flow 2020, 125, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inlet Conditions | Value |

|---|---|

| Bulk velocity of jet (m/s) | 60 |

| Liquid mass flow rate at jet exit (g/s) | 1.167 |

| Vapor fue flow rate at jet exit (g/min) | 0.083 |

| Temperature estimated at jet exit (K) | 293 |

| Carrier mass flow rate (g/s) | 6.267 |

| Equivalent ratio at jet exit | 0.1 |

| Parameter | Design Point | Takeoff Condition | Ground Idle | Maximum Continuous |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet air pressure | 1.000 | 0.965 | 0.376 | 0.907 |

| Inlet air temperature | 1.000 | 0.996 | 0.771 | 0.839 |

| Total airflow | 1.000 | 0.977 | 0.454 | 0.933 |

| Liner airflow | 1.000 | 0.977 | 0.456 | 0.932 |

| Fuel flow rate | 1.000 | 0.942 | 0.265 | 0.862 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, N.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Qiu, S.; Tang, Z.; Cui, J. Investigation of Hot Spot Migration in an Annular Combustor Using the SAS Turbulence Model. Energies 2025, 18, 6330. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236330

Liu N, Zeng Q, Wang L, Hu C, Qiu S, Tang Z, Cui J. Investigation of Hot Spot Migration in an Annular Combustor Using the SAS Turbulence Model. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6330. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236330

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ningfang, Qi Zeng, Liang Wang, Chang Hu, Sihuai Qiu, Zhuo Tang, and Jiahuan Cui. 2025. "Investigation of Hot Spot Migration in an Annular Combustor Using the SAS Turbulence Model" Energies 18, no. 23: 6330. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236330

APA StyleLiu, N., Zeng, Q., Wang, L., Hu, C., Qiu, S., Tang, Z., & Cui, J. (2025). Investigation of Hot Spot Migration in an Annular Combustor Using the SAS Turbulence Model. Energies, 18(23), 6330. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236330