Energy Costs and the Financial Situation of Farms in the European Union

Abstract

1. Introduction

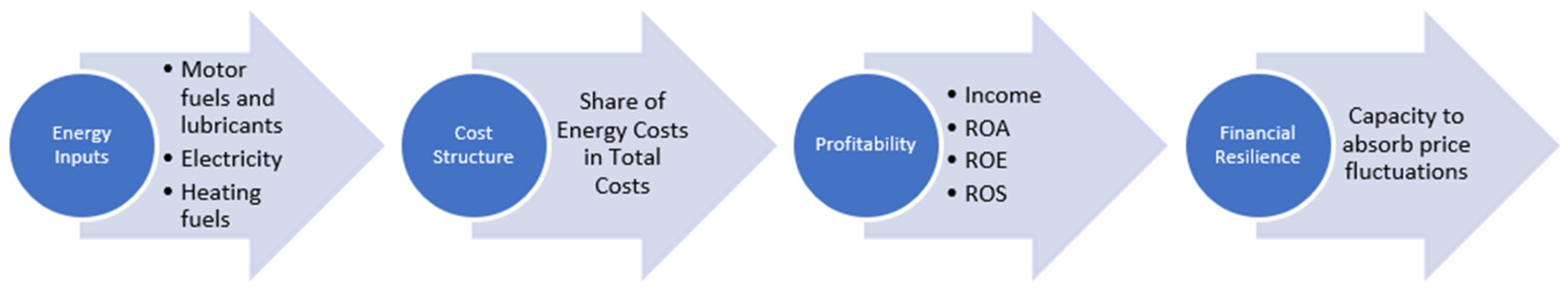

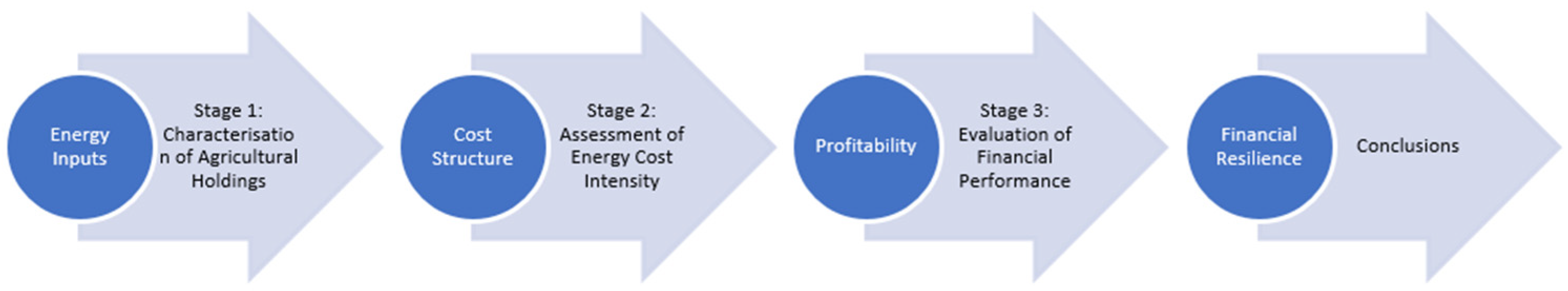

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Source and Scope

2.3. Analytical Stages and Indicators

2.4. Analytical Approach

2.5. Limitations

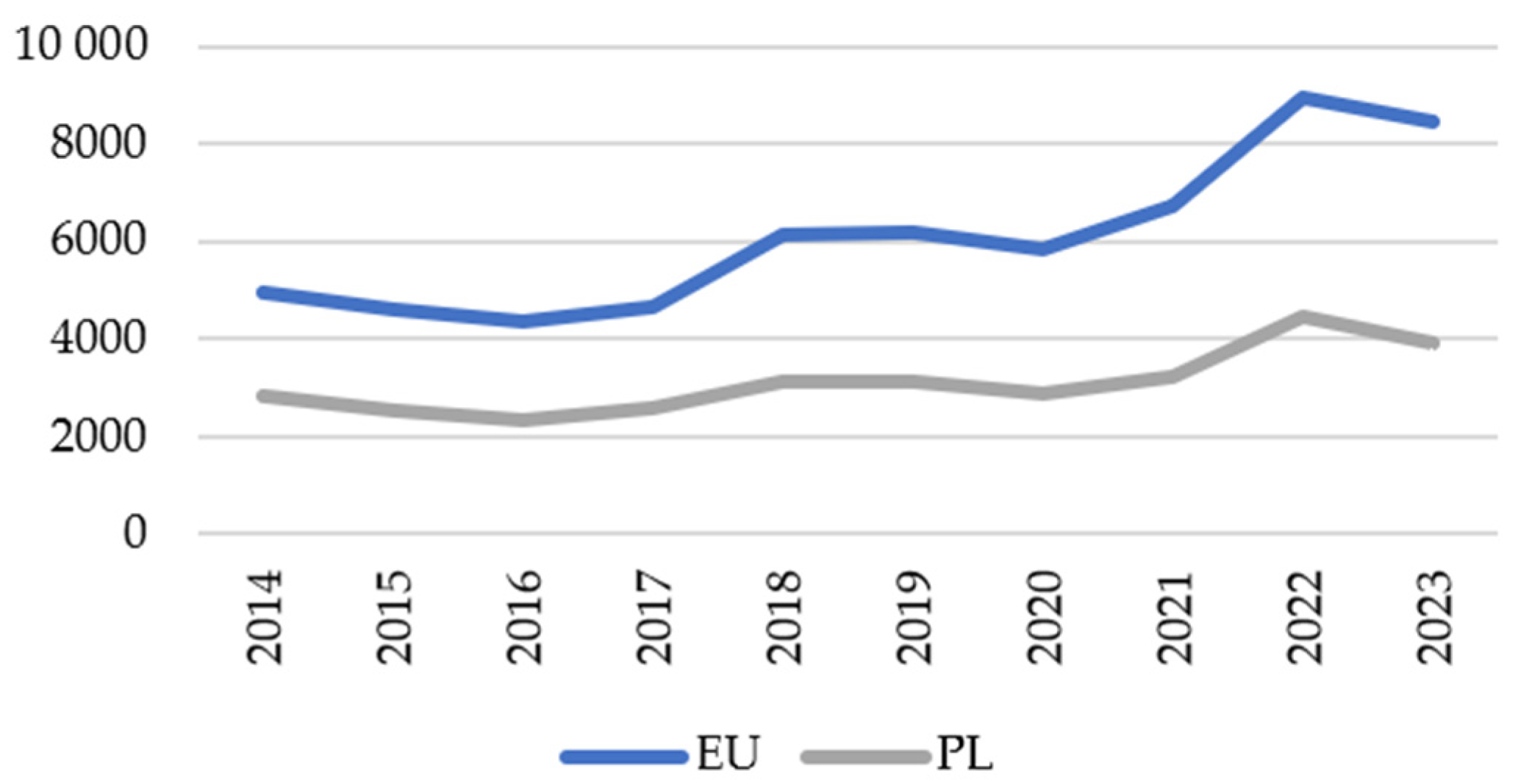

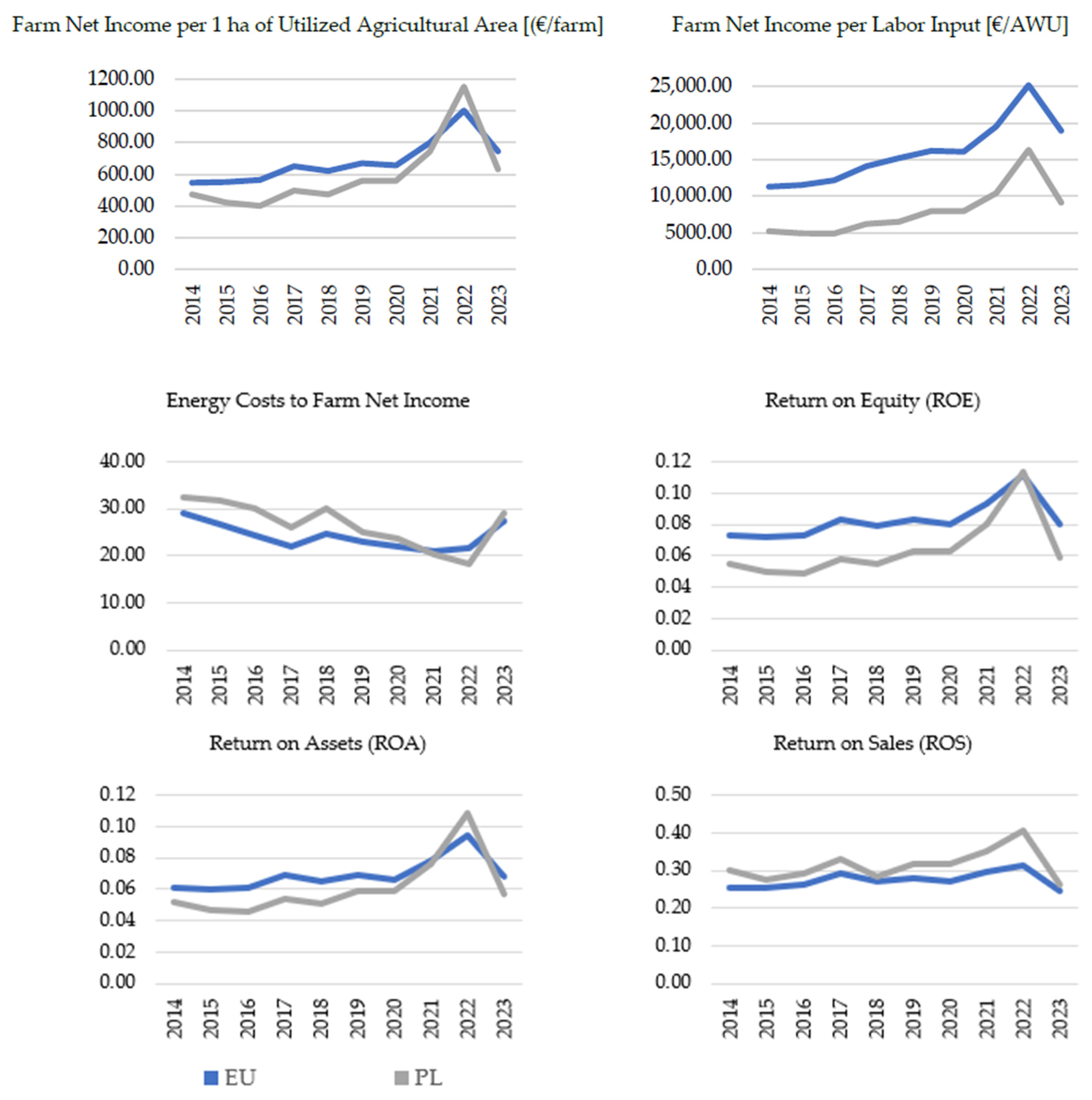

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| EU | European Union |

| UN | United Nations |

| FADN | Farm Accountancy Data Network |

| FSDN | Farm Sustainability Data Network |

| AWU | Annual Work Unit |

| ROE | Return on Equity |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| ROS | Return on Sales |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy |

Appendix A

| Description According to the FADN System | Category Explanation |

|---|---|

| (SE005) Economic size (€’000/farm) | Economic size of holding expressed in 1000 euro of standard output (on the basis of the Community typology). |

| (SE025) Total Utilized Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | Total utilized agricultural area of holding. Does not include areas used for mushrooms, land rented for less than one year on an occasional basis, woodland and other farm areas (roads, ponds, non-farmed areas, etc.). It consists of land in owner occupation, rented land, land in share-cropping (remuneration linked to output from land made available). It includes agricultural land temporarily not under cultivation for agricultural reasons or being withdrawn from production as part of agricultural policy measures. It is expressed in hectares (10,000 m2). |

| (SE010) Total labor input (AWU/farm) | Total labor input of holding expressed in annual work units = full-time person equivalents. |

| (SE131) Total output (€/farm) | Total value of output of crops and crop products, livestock and livestock products and of other output, including that of other gainful activities (OGA) of the farms. Sales and use of (crop and livestock) products and livestock + change in stocks of products (crop and livestock) + change in valuation of livestock—purchases of livestock + various non-exceptional products. |

| (SE436) Total assets (€/farm) | Fixed assets + current assets. |

| (SE441) Total fixed assets (€/farm) | Agricultural land and farm buildings and forest capital + Buildings + Machinery and equipment + Breeding livestock, Intangible assets and other non-current assets. Closing valuation |

| (SE465) Total current assets (€/farm) | Non-breeding livestock + Circulating capital (Stocks of agricultural products + Other circulating capital). Closing valuation |

| (SE485) Total liabilities (€/farm) | Value at closing valuation of total of (long-, medium- or short-term) loans still to be repaid. |

| (SE410) Gross Farm Income (€/farm) | Output—Intermediate consumption + Balance current subsidies and taxes. |

| (SE501) Net worth (€/farm) | Total assets—Liabilities. |

| (SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm) | Remuneration to fixed factors of production of the family (work, land and capital) and remuneration to the entrepreneur’s risks (loss/profit) in the accounting year. |

| (SE521) Net investment on fixed assets (€/farm) | Gross Investment on fixed assets—Depreciation. |

| (SE345) Energy (€/farm) | Motor fuels and lubricants, electricity, heating fuels. |

| Specification | Years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| EU | ||||||||||

| (SE005) Economic size (€’000/farm) | 62 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 99 |

| (SE025) Total Utilized Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | 31.2 | 31.7 | 31.9 | 32.4 | 40.1 | 40.2 | 40.3 | 40.4 | 41.2 | 41.7 |

| (SE010) Total labor input (AWU/farm) | 1.51 | 1.51 | 1.48 | 1.49 | 1.64 | 1.66 | 1.65 | 1.65 | 1.64 | 1.64 |

| (SE131) Total output (€/farm) | 66,953 | 68,553 | 68,499 | 72,504 | 92,021 | 96,855 | 97,176 | 108,183 | 132,018 | 127,340 |

| (SE436) Total assets (€/farm) | 281,931 | 292,827 | 297,215 | 304,212 | 380,432 | 389,932 | 398,758 | 413,700 | 439,996 | 458,940 |

| (SE441) Total fixed assets (€/farm) | 229,569 | 236,976 | 239,632 | 244,487 | 303,042 | 305,370 | 307,621 | 312,737 | 324,252 | 337,610 |

| (SE465) Total current assets (€/farm) | 52,362 | 55,851 | 57,583 | 59,725 | 77,390 | 84,562 | 91,137 | 100,962 | 115,744 | 121,330 |

| (SE485) Total liabilities (€/farm) | 48,132 | 51,462 | 51,892 | 52,395 | 66,716 | 67,409 | 67,969 | 69,453 | 71,414 | 73,030 |

| (SE501) Net worth (€/farm) | 233,799 | 241,365 | 245,323 | 251,817 | 313,717 | 322,523 | 330,788 | 344,247 | 368,581 | 385,910 |

| (SE410) Gross Farm Income (€/farm) | 35,617 | 36,606 | 37,396 | 40,716 | 50,161 | 52,994 | 52,858 | 59,104 | 69,954 | 62,352 |

| (SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm) | 17,053 | 17,427 | 18,006 | 21,026 | 24,900 | 26,898 | 26,495 | 32,211 | 41,255 | 31,013 |

| (SE521) Net investment on fixed assets (€/farm) | 268 | 595 | −450 | 304 | 1543 | 989 | 1454 | 2181 | 2812 | 3182 |

| Poland | ||||||||||

| (SE005) Economic size (€’000/farm) | 28 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 36 |

| (SE025) Total Utilized Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | 18.4 | 19.1 | 19.6 | 19.9 | 22.1 | 22.2 | 21.8 | 21.4 | 21.3 | 21.3 |

| (SE010) Total labor input (AWU/farm) | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| (SE131) Total output (€/farm) | 29,122 | 29,168 | 26,750 | 30,117 | 37,192 | 39,270 | 38,341 | 45,222 | 60,648 | 51,397 |

| (SE436) Total assets (€/farm) | 168,234 | 173,884 | 171,031 | 182,902 | 205,542 | 210,104 | 205,551 | 207,732 | 224,737 | 235,739 |

| (SE441) Total fixed assets (€/farm) | 151,017 | 156,335 | 152,983 | 163,126 | 182,813 | 185,987 | 182,157 | 181,552 | 190,400 | 204,110 |

| (SE465) Total current assets (€/farm) | 17,217 | 17,549 | 18,048 | 19,776 | 22,729 | 24,117 | 23,394 | 26,180 | 34,337 | 31,629 |

| (SE485) Total liabilities (€/farm) | 9622 | 10,701 | 10,013 | 10,421 | 14,296 | 13,606 | 12,208 | 10,794 | 9441 | 9367 |

| (SE501) Net worth (€/farm) | 158,612 | 163,183 | 161,017 | 172,482 | 191,247 | 196,498 | 193,343 | 196,938 | 215,297 | 226,372 |

| (SE410) Gross Farm Income (€/farm) | 15,635 | 15,350 | 14,870 | 17,342 | 19,159 | 20,972 | 20,619 | 24,269 | 33,180 | 22,919 |

| (SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm) | 8706 | 8039 | 7842 | 9910 | 10,457 | 12,379 | 12,145 | 15,855 | 24,482 | 13,408 |

| (SE521) Net investment on fixed assets (€/farm) | −1100 | −665 | −2254 | −1365 | −1127 | −763 | −1282 | −869 | −756 | −1567 |

References

- Sulewski, P.; Wąs, A. Agriculture as Energy Prosumer: Review of Problems, Challenges, and Opportunities. Energies 2024, 17, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnepf, R. Energy Use in Agriculture: Background and Issues; CRS Report No. RL32677; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Qin, J.; Duan, W.; Zou, S.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Rosa, L. Global Energy Use and Carbon Emissions from Irrigated Agriculture. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołasa, P.; Wysokiński, M.; Bieńkowska-Gołasa, W.; Gradziuk, P.; Golonko, M.; Gradziuk, B.; Siedlecka, A.; Gromada, A. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Agriculture, with Particular Emphasis on Emissions from Energy Used. Energies 2021, 14, 3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.Y.; Zhongpan, Q.; Pengju, W. Agriculture-Related Energy Consumption, Food Policy, and CO2 Emission Reduction: New Insights from Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1099813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammini, A.; Pan, X.; Tubiello, F.N.; Qiu, S.Y.; Rocha Souza, L.; Quadrelli, R.; Bracco, S.; Benoit, P.; Sims, R. Emissions of Greenhouse Gases from Energy Use in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: 1970–2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, B.; Vandorou, F.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Vaiopoulos, K.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Manolakos, D.; Papadakis, G. Energy Use in Open-Field Agriculture in the EU: A Critical Review Recommending Energy Efficiency Measures and Renewable Energy Sources Adoption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (Eurostat). Agri-Environmental Indicator—Energy Use; Statistics Explained; European Union: Luxembourg, 2024.

- Bathaei, A.; Štreimikienė, D. Renewable Energy and Sustainable Agriculture: Review of Indicators. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghjoo, R.; Choobchian, S.; Abbasi, E. Unveiling Energy Security in Agriculture through Vital Indicators Extraction and Insights. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriani, F.; Gazzani, A. The Impact of the War in Ukraine on Energy Prices: Consequences for Firms’ Financial Performance. Int. Econ. 2023, 175, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Abbas, Q.; Sharif, M. Addressing Agricultural Energy Poverty to Enhance Farmers’ Profitability and Productivity: Policy Interventions for Global Food Security Challenges. Energy Policy 2025, 206, 114696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ryś-Jurek, R. Interdependence between Energy Cost and Financial Situation of the EU Agricultural Farms—Towards the Implementation of the Bioeconomy. Energies 2022, 15, 8853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryś-Jurek, R. On-Farm Production of Renewable Energy in 2014–2022. Energies 2024, 17, 5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, Y.; Khan, M.U.; Waseem, M.; Zahid, U.; Mahmood, F.; Majeed, F.; Sultan, M.; Raza, A. Renewable Energy as an Alternative Source for Energy Management in Agriculture. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 6915–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD). Off. J. Eur. Union 2013, L 347, 487–548. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2021/2115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 December 2021 establishing rules on support for CAP Strategic Plans drawn up by Member States under the CAP. Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, L 435, 1–186. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Excise Duties: Current Energy Tax Rules; Taxation and Customs Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- Markuszewska, I. Land consolidation as an instrument of shaping the agrarian structure in Poland: A case study of the Wielkopolskie and Dolnośląskie voivodeships. Quaest. Geogr. 2013, 32, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, D.G.; Dinu, T.A. Correlations between fragmentation of farms in the Republic of Poland, Romania and Moldova. Probl. World Agric. 2015, 15, 166–179. [Google Scholar]

- Grzelak, A. Accumulation of assets in farms covered by the FADN system in Poland. Management 2019, 23, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bórawski, P.; Dunn, J.W.; Bialczyk, W.; Harper, J.K.; Soroka, A.; Szymańska, E.J. Investments in Polish agriculture: How production factors shape conditions for environmental protection. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinambela, E.A.; Djaelani, M. Cost Behavior Analysis and Categorization. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2022, 2, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberholzer, M.; Ziemerink, J.E.E. Cost Behaviour Classification and Cost Behaviour Structures of Manufacturing Companies. Meditari Account. Res. 2004, 12, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, B. Cost Accounting: Theory and Practice, 14th ed.; PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Usul, H.; Olgun, E.B. An Analysis of Material Flow Cost Accounting in Companies Using Different Cost Accounting Systems. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajner, P.; Wieliczko, B. Energy Efficiency in Polish Farms. Energies 2024, 17, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędruchniewicz, A. Changes in Prices of Agricultural Inputs and Their Impact on Agricultural Production Costs in Poland. Zagadnienia Ekon. Rolnej/Probl. Agric. Econ. 2023, 374, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- FI-Compass. Agricultural Investment Support-Study on Financial Needs and Instruments in EU Agriculture; European Investment Bank/European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Martinho, V.J.P.D. Energy Consumption across European Union Farms: Efficiency in terms of farming output and utilized agricultural area. Energy 2016, 103, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2023/2674 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 November 2023 Amending Council Regulation (EC) No 1217/2009 as Regards Conversion of the Farm Accountancy Data Network into a Farm Sustainability Data Network, PE/53/2023/REV/1. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L 2023/2674, 1–20.

- Badach, E.; Szewczyk, J.; Lisek, S.; Bożek, J. Size Structure Transformation of Polish Agricultural Farms in 2010–2020 by Typological Groups of Voivodeships. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąs, A.; Tsybulska, J.; Sulewski, P.; Krupin, V.; Rawa, G.; Skorokhod, I. Energy Efficiency of Polish Farms Following EU Accession (2004–2021). Energies 2025, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Factsheet on 2014–2022 Rural Development Programme for Poland. February 2025. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-11/rdp-factsheet-poland_en_0.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- European Commission. Definitions of Variables Used in FADN Standard Results (RI/CC 1750); Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. Available online: https://fadn.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/RICC_1750_Standard_Results-v-Jun-2022.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- European Commission. Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) Public Database; Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available online: https://agridata.ec.europa.eu/extensions/FADNPublicDatabase/FADNPublicDatabase.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Kryszak, Ł.; Guth, M.; Czyżewski, B. Determinants of Farm Profitability in the EU Regions: Does Farm Size Matter? Agric. Econ.–Czech 2021, 67, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafraniec-Siluta, E.; Strzelecka, A.; Ardan, R.; Zawadzka, D. Financial Energy as a Determinant of Financial Security: The Case of European Union Farms. Energies 2025, 18, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafraniec-Siluta, E.; Strzelecka, A.; Ardan, R.; Zawadzka, D. Determinants of Financial Security of European Union Farms—A Factor Analysis Model Approach. Agriculture 2024, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysokiński, M.; Golonko, M.; Trębska, P.; Gromada, A.; Jiang, Q. Economic and Energy Efficiency of Agriculture in Poland Compared to Other European Union Countries. Acta Sci. Pol. Oeconomia 2020, 19, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulewski, P.; Majewski, E.; Wąs, A. The Importance of Agriculture in the Renewable Energy Production in Poland and the EU. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2017, 1, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczar, P.; Błażejczyk-Majka, L. Economic Efficiency versus Energy Efficiency of Selected Crops in EU Farms. Resources 2024, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, V.J.P.D. Five Models and Ten Predictors for Energy Costs on Farms in the European Union. Open Agric. 2025, 10, 20250441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of the Indicator | Categories Applied from the FADN System |

|---|---|

| Share of Energy Costs in Total Costs [%] | (SE345) Energy (€/farm)/(SE270) Total Inputs (€/farm) |

| Share of Energy Costs in Intermediate Consumption [%] | (SE345) Energy (€/farm)/(SE275) Total intermediate consumption (€/farm) |

| Energy Costs per 1 ha of Utilized Agricultural Area [€/ha] | (SE345) Energy (€/farm)/(SE025) Total Utilized Agricultural Area (ha/farm) |

| Energy Costs per Labor Input [€/AWU] | (SE345) Energy (€/farm)/(SE010) Total labor input (AWU/farm) |

| Energy Costs per Unit of Output | (SE345) Energy (€/farm)/(SE131) Total output (€/farm) |

| Energy Costs per Gross Farm Income | (SE345) Energy (€/farm)/(SE410) Gross Farm Income (€/farm) |

| Name of the Indicator | Categories Applied from the FADN System |

|---|---|

| Farm Net Income per 1 ha of Utilized Agricultural Area [(€/farm] | [(SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm)/(SE025) Total Utilized Agricultural Area (ha/farm)] × 100 |

| Farm Net Income per Labor Input [€/AWU] | [(SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm)/((SE010) Total labor input (AWU/farm)] × 100 |

| Energy Costs to Farm Net Income | (SE345) Energy (€/farm)/(SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm) |

| Return on Equity (ROE) | ROE = (SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm)/(SE501) Net worth (€/farm) |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | ROA = (SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm)/(SE436) Total assets (€/farm) |

| Return on Sales (ROS) | ROS = (SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm)/(SE131) Total output (€/farm) |

| Variable | Relevance in the Context of Financial Resilience to Energy Price Fluctuations | Assessment of Agricultural Holdings in Poland Compared to the European Union |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of agricultural holdings | ||

| (SE005) Economic size (€’000/farm) | Greater economic size increases resilience through economies of scale and a higher capacity to absorb rising energy costs. | negative |

| (SE025) Total Utilized Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | Larger utilized agricultural area enables diversification and the distribution of unit costs, thereby reducing the impact of energy price increases. | negative |

| (SE131) Total output (€/farm) | Higher production levels improve the ability to offset rising costs through increased revenues. | negative |

| (SE436) Total assets (€/farm) | Greater asset value reflects a higher investment potential and the ability to modernize towards improved energy efficiency. | negative |

| (SE501) Net worth (€/farm) | A higher share of own capital enhances the capacity for self-financing investments. | negative |

| (SE420) Farm Net Income (€/farm) | Higher income improves liquidity and flexibility in responding to rising energy costs. | negative |

| (SE521) Net investment on fixed assets (€/farm) | Positive net investment indicates ongoing modernization and improvements in efficiency, including energy efficiency. | negative |

| Energy characteristics | ||

| Share of Energy Costs in Total Costs [%] | Higher share indicates greater dependence on energy prices and lower financial resilience. | negative |

| Share of Energy Costs in Intermediate Consumption [%] | It reflects operational energy intensity; lower values indicate higher efficiency and adaptive capacity. | negative |

| Energy Costs per 1 ha of Utilized Agricultural Area [€/ha] | It defines the energy burden of production; lower energy costs per hectare improve competitiveness. | positive |

| Energy Costs per Labor Input [€/AWU] | It indicates the energy efficiency of labor; lower values suggest better mechanization and production organization. | positive |

| Energy Costs per Unit of Output | It measures the energy intensity of production; lower ratios increase profitability under rising energy prices. | negative |

| Energy Costs per Gross Farm Income | It specifies the share of energy costs in the farm’s gross value added; lower values denote greater economic efficiency. | negative |

| Financial Performance of Agricultural Farms | ||

| Farm Net Income per 1 ha of Utilized Agricultural Area [(€/farm] | Higher income per hectare increases the ability to maintain profitability despite rising energy prices. | negative |

| Farm Net Income per Labor Input [€/AWU] | It reflects labor productivity; higher values indicate greater resilience to increasing costs. | negative |

| Energy Costs to Farm Net Income | It shows the sensitivity of income to energy costs; lower values denote stronger financial resilience. | negative |

| Return on Equity (ROE) | It determines capital profitability; higher values may drive investments in energy-efficient technologies. | negative |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | It reflects asset utilization efficiency; higher values indicate greater financial stability. | negative |

| Return on Sales (ROS) | It measures profit margin; higher values potentially enhance resilience to energy cost fluctuations. | positive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strzelecka, A.; Szafraniec-Siluta, E.; Zawadzka, D. Energy Costs and the Financial Situation of Farms in the European Union. Energies 2025, 18, 6299. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236299

Strzelecka A, Szafraniec-Siluta E, Zawadzka D. Energy Costs and the Financial Situation of Farms in the European Union. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6299. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236299

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrzelecka, Agnieszka, Ewa Szafraniec-Siluta, and Danuta Zawadzka. 2025. "Energy Costs and the Financial Situation of Farms in the European Union" Energies 18, no. 23: 6299. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236299

APA StyleStrzelecka, A., Szafraniec-Siluta, E., & Zawadzka, D. (2025). Energy Costs and the Financial Situation of Farms in the European Union. Energies, 18(23), 6299. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236299