Sensorless Field-Oriented Control of a Low-Speed Six-Phase Induction Generator

Abstract

1. Introduction

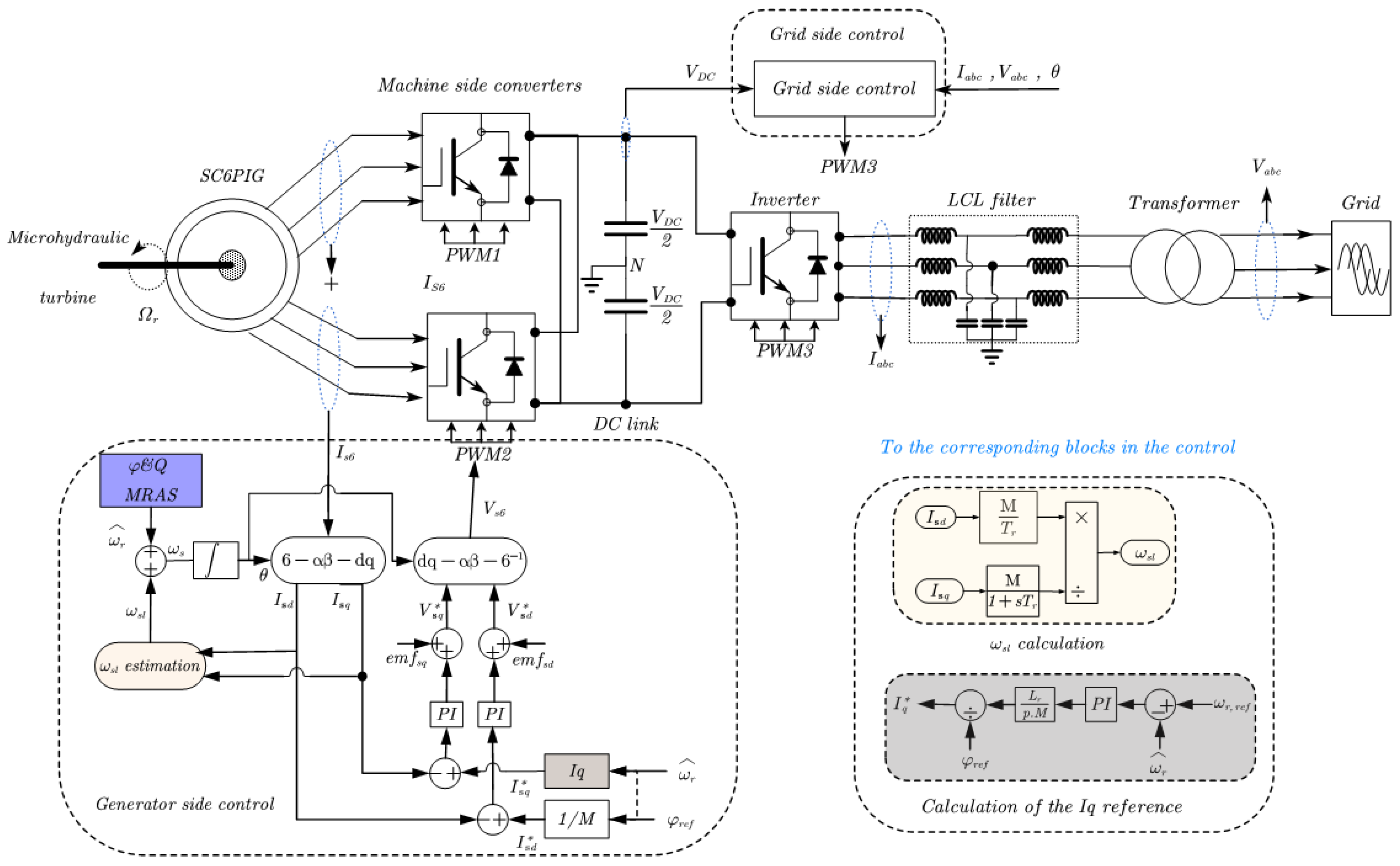

2. Modeling and Control of a Six-Phase Induction Generator (6PIG)

2.1. Modeling of the 6PIG

2.2. Indirect Rotor Field-Oriented Control of the 6PIG

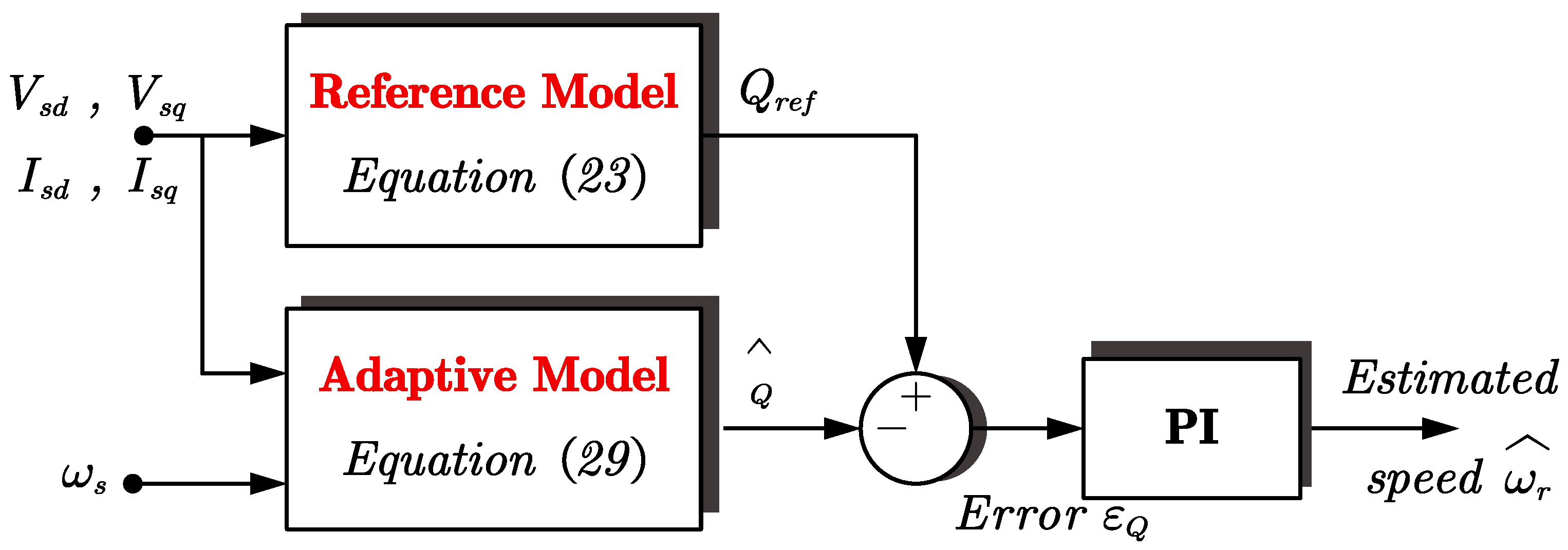

3. Sensorless Estimation Using Model Reference Adaptive System (MRAS)

3.1. Conventional Flux-Based MRAS

3.2. Reactive Power-Based MRAS for Enhanced Low-Speed Estimation

4. Simulations and Experimental Results

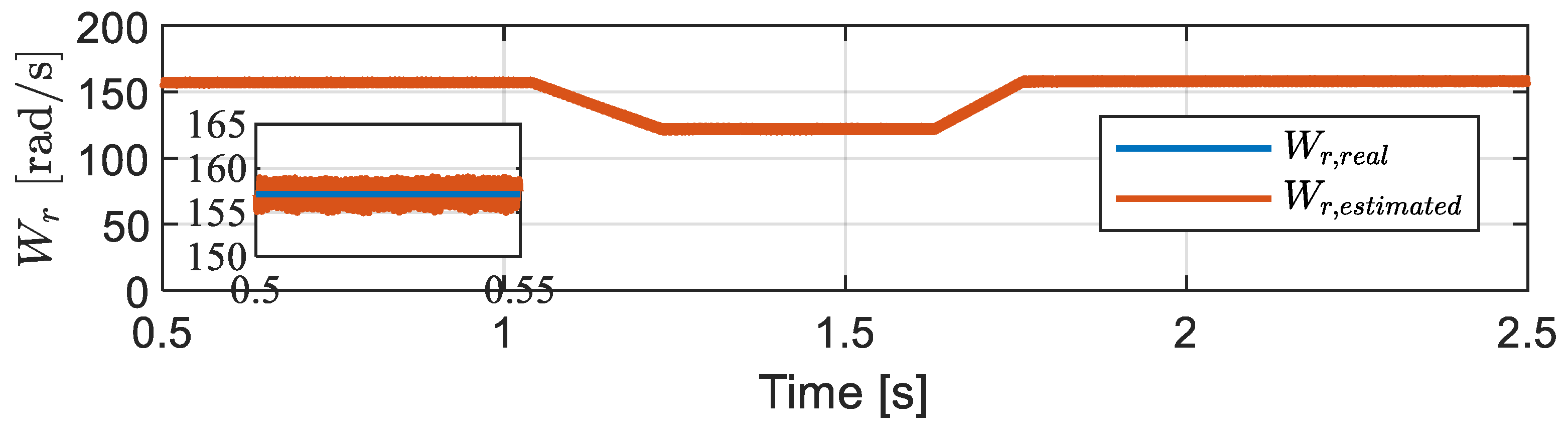

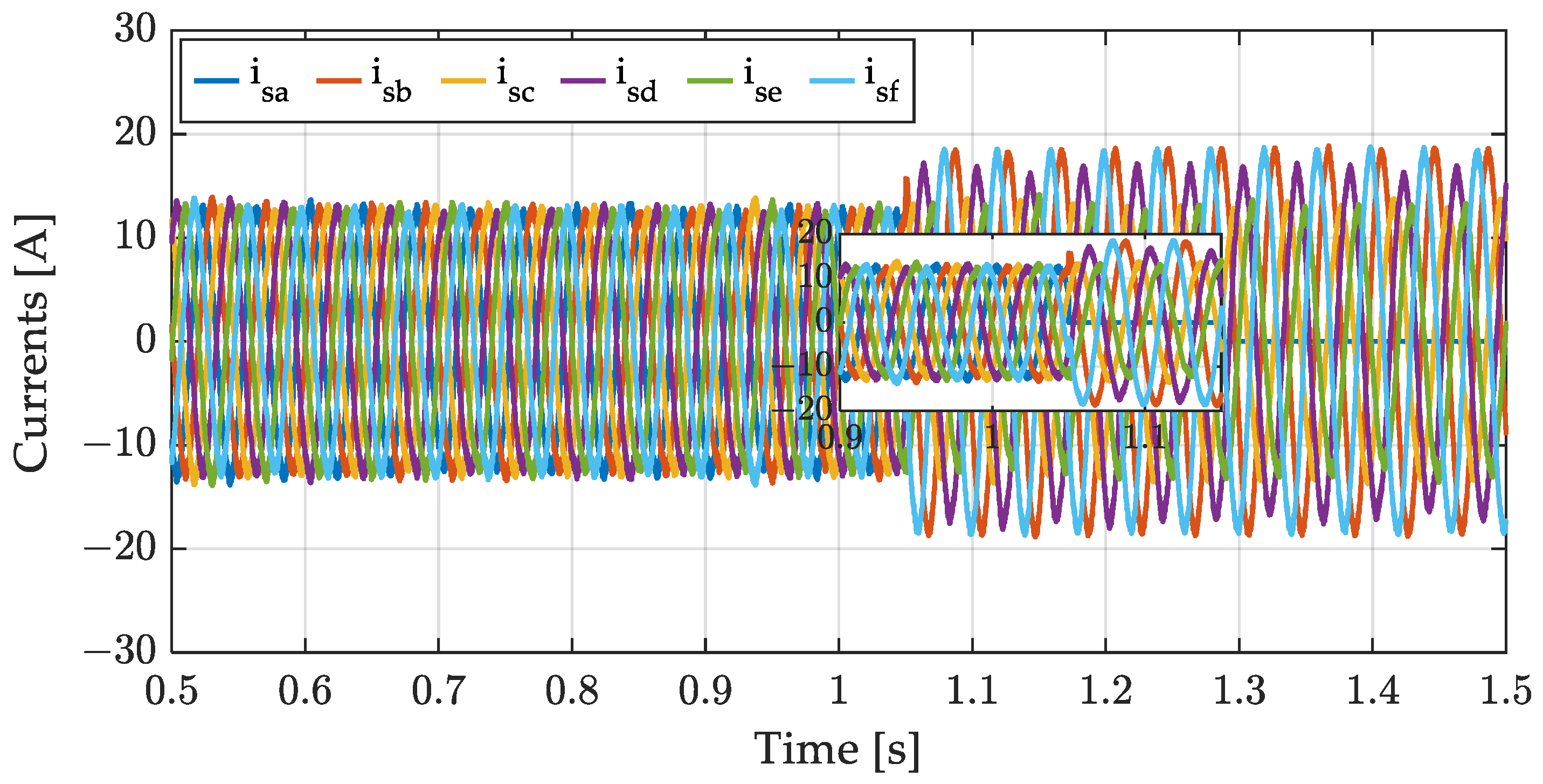

4.1. Simulations Results

- a.

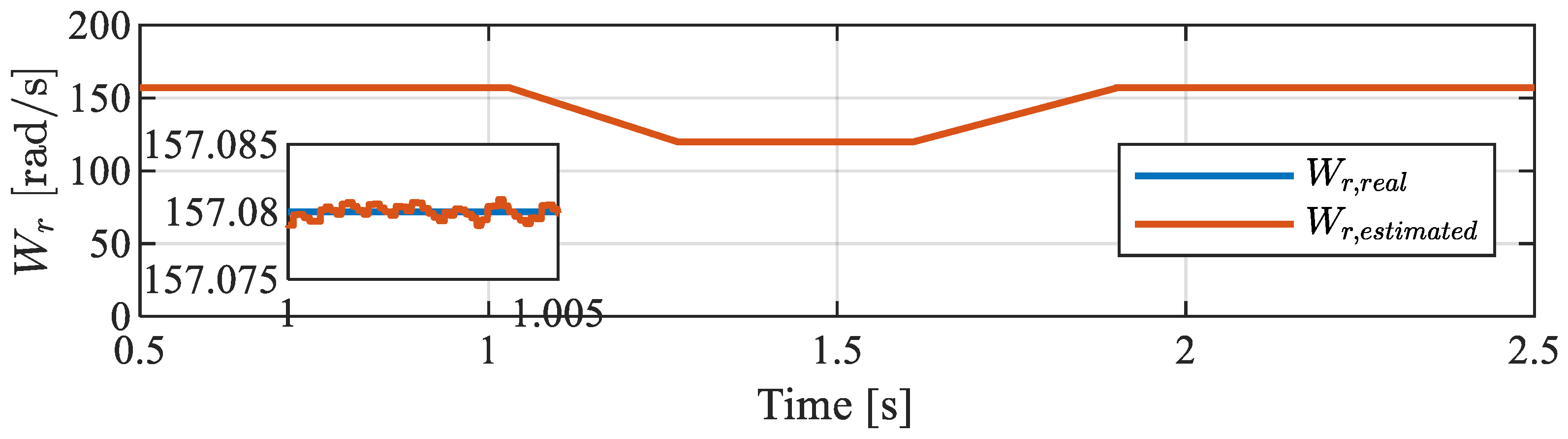

- Flux-based MRAS

- b.

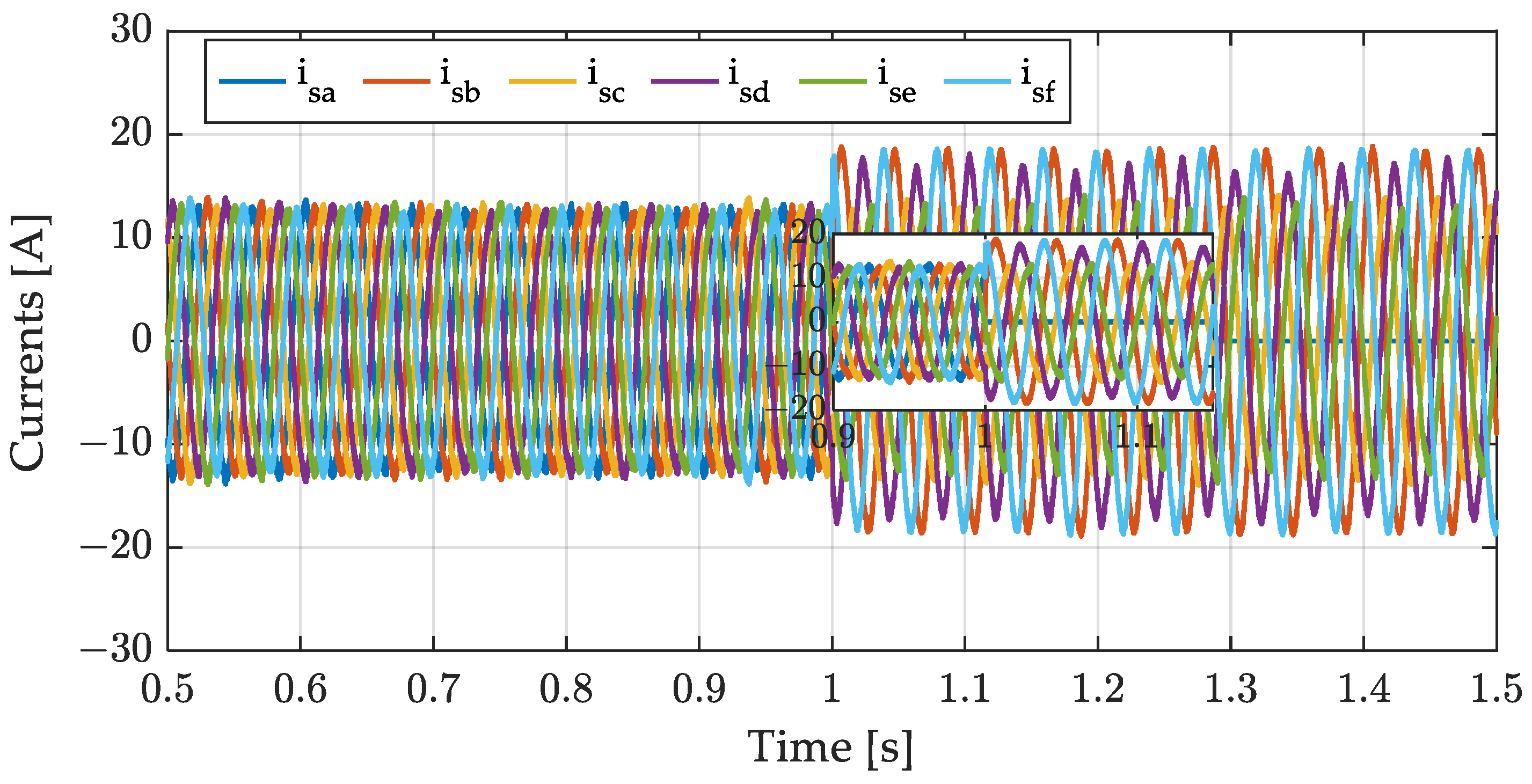

- Reactive power-based MRAS

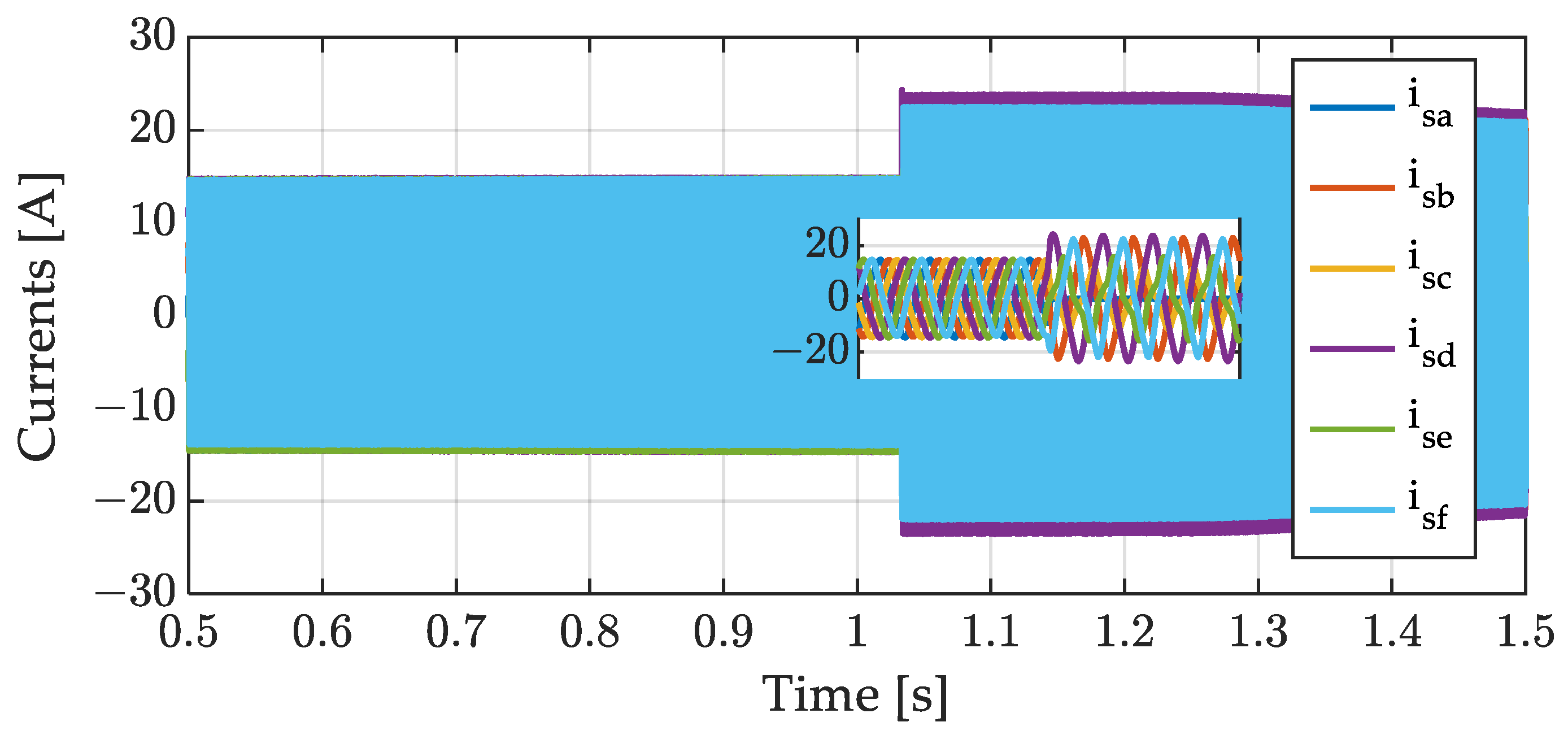

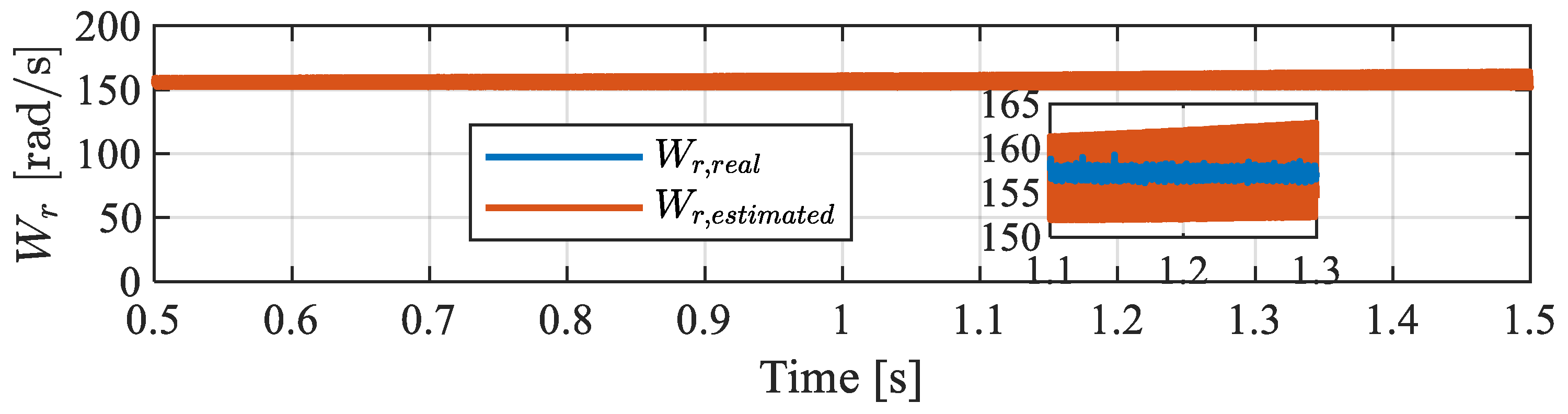

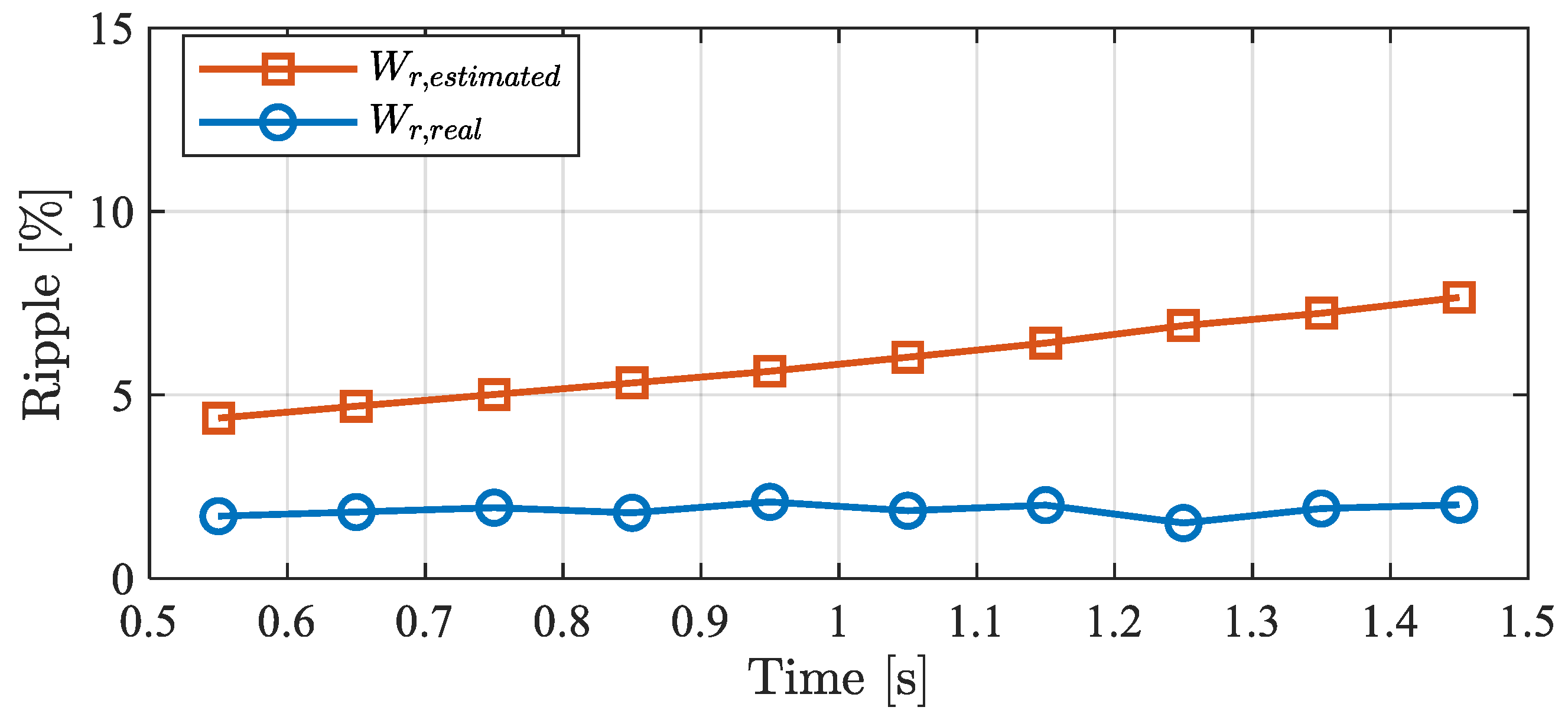

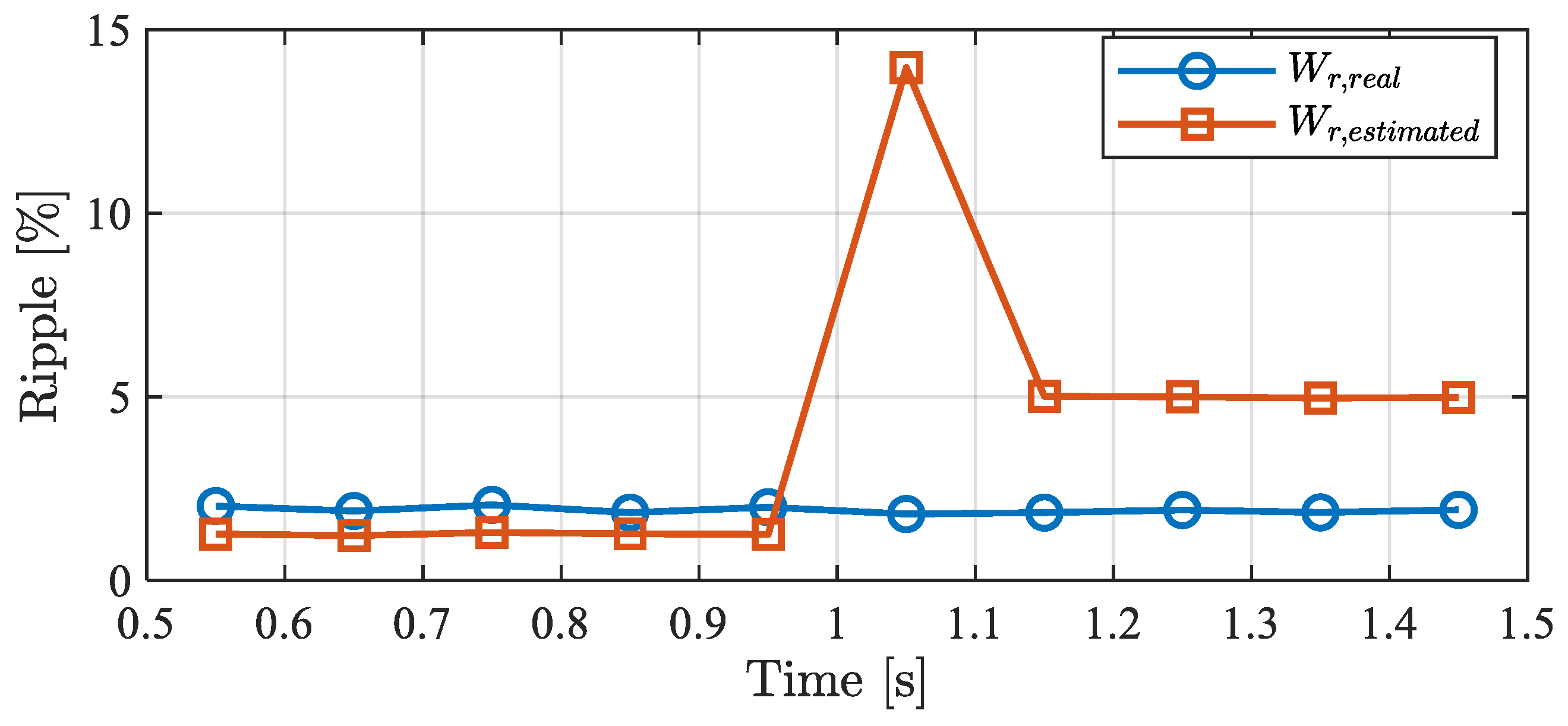

4.2. Experimental Results

- a.

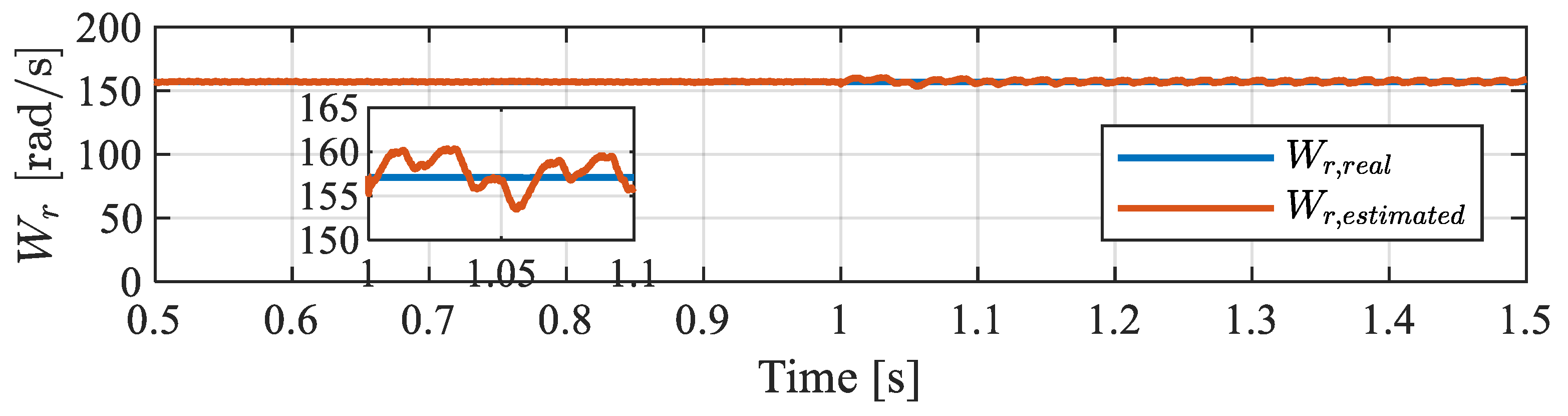

- Flux-based MRAS

- b.

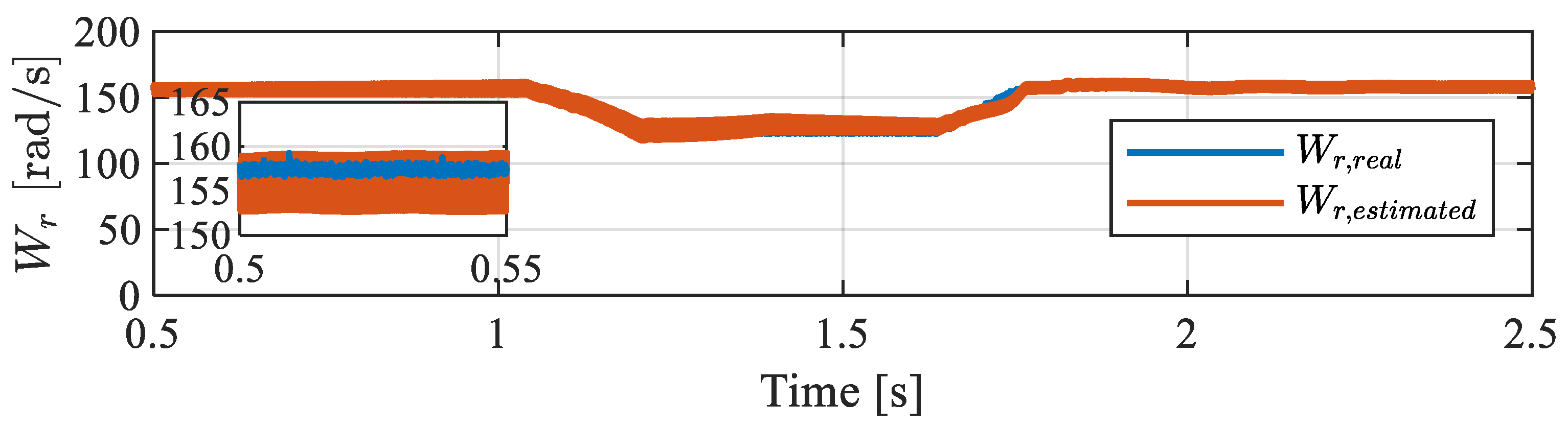

- Reactive power-based MRAS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SC6PIG | Squirrel Cage Six-Phase Induction Generator |

| 6PIG | Six-Phase Induction Generator |

| FOC | Field Oriented Control |

| IRFOC | Indirect Rotor Field Oriented Control |

| PWM | Pulse Width Modulation |

| VSI | Voltage Source Inverter |

| MRAS | Model Reference Adaptive System |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Square Error |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Rated power | 24 | kW |

| Rated torque | 2350 | Nm |

| Rated voltage | 230 | V |

| Rated speed | 125 | rpm |

| Rated current | 32.3 | A |

| Frequency | 25 | Hz |

| Number of pole pairs | 12 | - |

| Stator resistance Rs | 0.262 | Ჲ |

| Rotor resistance Rr | 0.64 | Ჲ |

| Stator inductance Ls | 0.0827 | H |

| Rotor inductance Lr | 0.0813 | H |

| Mutual inductance M | 0.0789 | H |

| Currents | Flux MRAS | Reactive Power MRAS |

|---|---|---|

References

- Li, L.; Lin, J.; Wu, N.; Xie, S.; Meng, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Review and outlook on the international renewable energy development. Energy Built Environ. 2022, 3, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katre, S.S.; Bapat, V.N. Review of Literature on Induction Generators and Controllers for Pico Hydro Applications. Int. J. Innov. Eng. Res. Technol. 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelwanis, M.I.; Rashad, E.M.; Taha, I.B.M.; Selim, F.F. Implementation and Control of Six-Phase Induction Motor Driven by a Three-Phase Supply. Energies 2021, 14, 7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemi-Rostami, M.; Rezazadeh, G.; Tahami, F.; Akbari Resketi, H.R. Fault-tolerant capability analysis of six-phase induction motor with distributed, concentrated, and pseudo-concentrated windings. Sci. Iran. 2024, 31, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigatos, G.; Abbaszadeh, M.; Sari, B.; Siano, P. Nonlinear Optimal Control for Six-Phase Induction Generator-Based Renewable Energy Systems. J. Energy Power Technol. 2023, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.K.; Husain, Z. Application of Novel Six-phase Doubly fed induction generator for Open Phases through Modeling and Simulation. IETE J. Res. 2023, 69, 3916–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milles, A.; Merabet, E.; Benbouhenni, H.; Colak, I.; Bensedira, N.; Debdouche, N.; Aggoune, M.-S.; Boukhalfa, G. Enhancing the backstepping control approach competencies for wind turbine systems using a dual star induction generator. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akrami, M.; Jamshidpour, E.; Baghli, L.; Frick, V. Application of Low-Resolution Hall Position Sensor in Control and Position Estimation of PMSM—A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacas, M. Sensorless Drives in Industrial Applications Advanced Control Schemes. Ind. Electron. Mag. IEEE 2011, 5, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, M.S.; Metwaly, M.K. Improved MRAS observer with rotor flux correction terms and FLC-based adaptive law for sensorless induction motor drives. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtz, J. Sensorless control of induction motor drives. Proc. IEEE 2002, 90, 1359–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Liu, S. Speed-Sensorless Vector Control Based on ANN MRAS for Induction Motor Drives. J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Inform. 2015, 19, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Das, S.; Syam, P.; Chattopadhyay, A.K. Review on model reference adaptive system for sensorless vector control of induction motor drives. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2015, 9, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C. Sensorless Speed Control Based on the Improved Q-MRAS Method for Induction Motor Drives. Energies 2018, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Kumar, B.; Chauhan, Y.K. ANN based RF-MRAS speed estimation of induction motor drive at low speed. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference of Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, India, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bielesz, D.; Kubatko, M.; Kirschner, Š.; Milata, J.; Šotola, V. Artificial neural network-based estimation for rotor-flux model reference adaptive system. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadasian, M.; Kianinezhad, R.; Betin, F.; Yazidi, A.; Lanfranchi, V.; Capolino, G.-A. Position control of faulted six-phase induction machine using genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the SDEMPED 2011—8th IEEE Symposium on Diagnostics for Electrical Machines, Power Electronics and Drives, Bologna, Italy, 5–8 September 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadasian, M.; Kiani, R.; Betin, F.; Lanfranchi, V.; Yazidi, A.; Capolino, G.A. Intelligent sensorless speed control of six-phase induction machine. In Proceedings of the IECON 2011—37th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Melbourne, Australia, 7–10 November 2011; pp. 4198–4203. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, K.; Maurya, R. A robust sensor-less field-oriented control of six-phase induction motor drive with reduced common mode voltage. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2025, 53, 1354–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurwati, T. Contribution to Fuzzy Logic Controller of Six-Phase Induction Generator for Wind Turbine Application. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Picardy Jules Verne, Amiens, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aroquiadassou, G.; Henao, H.; Capolino, G.A.; Boglietti, A.; Cavagnino, A. A simple circuit-oriented model for predicting six-phase induction machine performances. In Proceedings of the IECON 2006—32nd Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics, Paris, France, 6–10 November 2006; pp. 1441–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, E.; Bojoi, R.; Profumo, F.; Toliyat, H.; Williamson, S. Multiphase induction motor drives—A technology status review. Electr. Power Appl. IET 2007, 1, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghli, L. Modélisation et Commande de la Machine Asynchrone. 2020. Available online: https://www.baghli.com/dl/courscmde/cours_cmde_MAS.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Rashed, M.; Stronach, F.; Vas, P. A stable MRAS-based sensorless vector control induction motor drive at low speeds. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference, 2003. IEMDC’03, Madison, WI, USA, 1–4 June 2003; Volume 1, pp. 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Schauder, C. Adaptive speed identification for vector control of induction motors without rotational transducers. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1992, 28, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MRAS Methods | Flux-Based | Reactive Power-Based | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Healthy | Faulty | Healthy | Faulty |

| Ripple (%) | 4.69 | 7.23 | 1.27 | 4.97 |

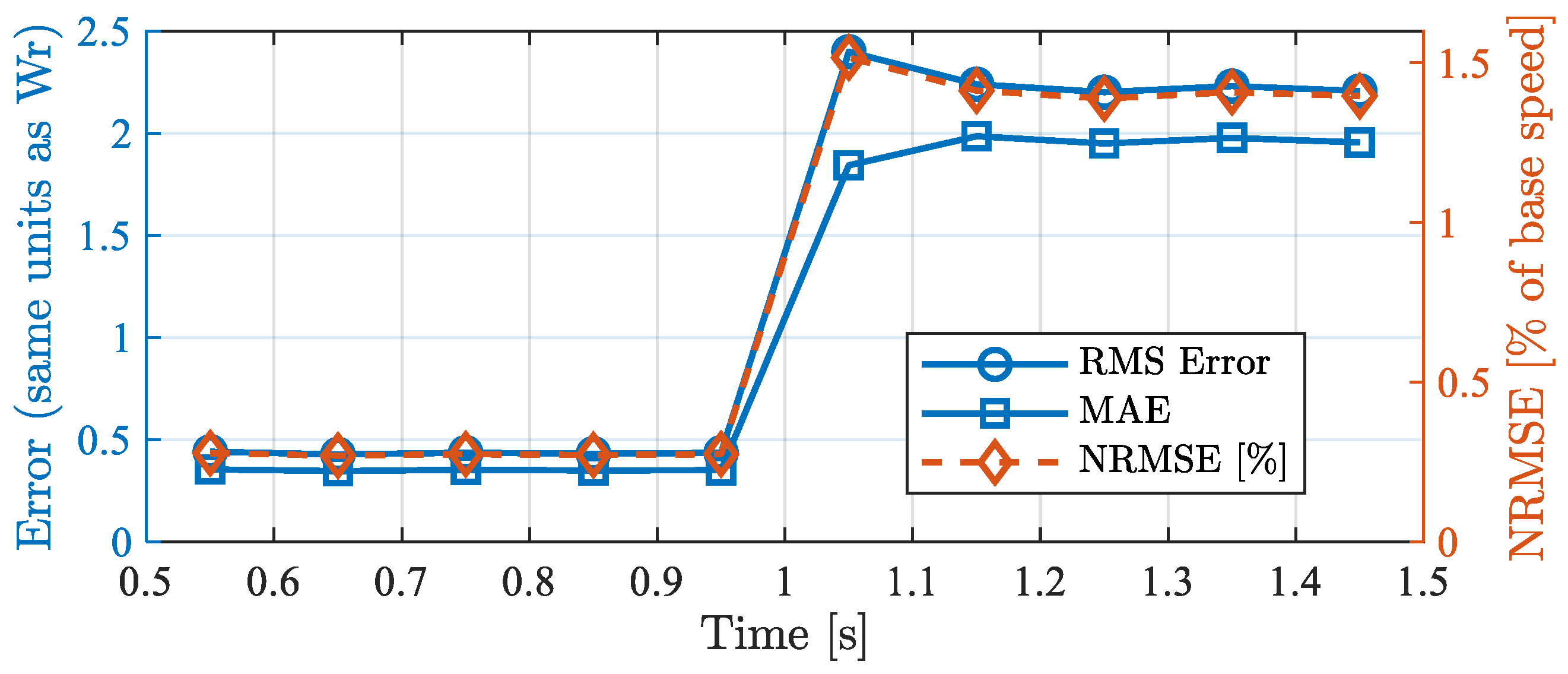

| MRAS Methods | Mode | Interval | RMS Error | NRMSE (% Base) | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux-based | Healthy | 0.5–1.0 s | 2.91 | 1.83 | 2.41 |

| Faulty | 1.0–1.5 s | 3.75 | 2.40 | 3.27 | |

| Reactive power-based | Healthy | 0.5–1.0 s | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.35 |

| Faulty | 1.0–1.5 s | 2.20 | 1.40 | 1.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouédraogo, M.; Yazidi, A.; Betin, F. Sensorless Field-Oriented Control of a Low-Speed Six-Phase Induction Generator. Energies 2025, 18, 6293. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236293

Ouédraogo M, Yazidi A, Betin F. Sensorless Field-Oriented Control of a Low-Speed Six-Phase Induction Generator. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6293. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236293

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuédraogo, Marius, Amine Yazidi, and Franck Betin. 2025. "Sensorless Field-Oriented Control of a Low-Speed Six-Phase Induction Generator" Energies 18, no. 23: 6293. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236293

APA StyleOuédraogo, M., Yazidi, A., & Betin, F. (2025). Sensorless Field-Oriented Control of a Low-Speed Six-Phase Induction Generator. Energies, 18(23), 6293. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236293