Improvement of Fast Simulation Method of the Flow Field in Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Wind Farms and Consideration of the Effects of Turbine Selection Order

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

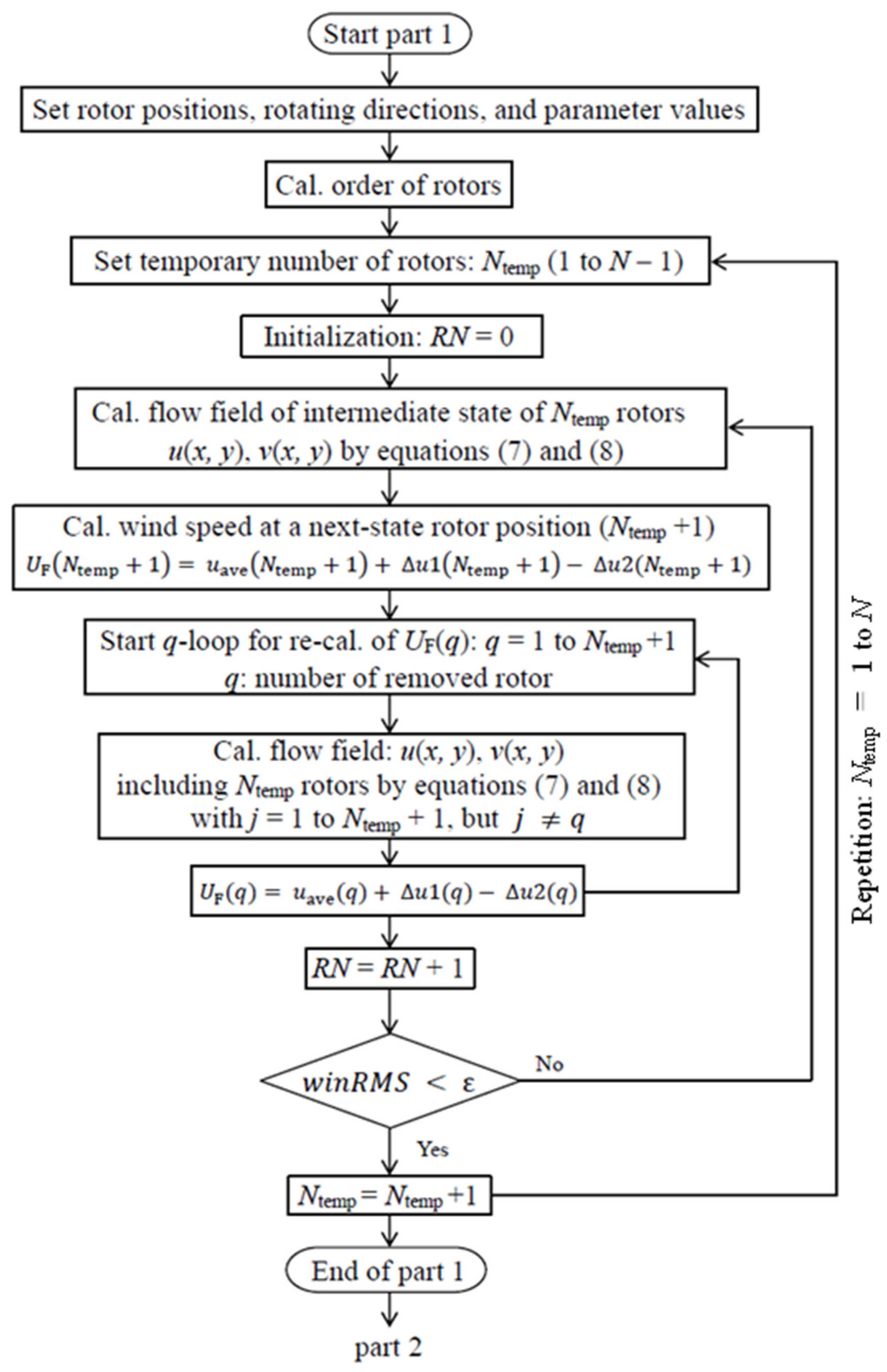

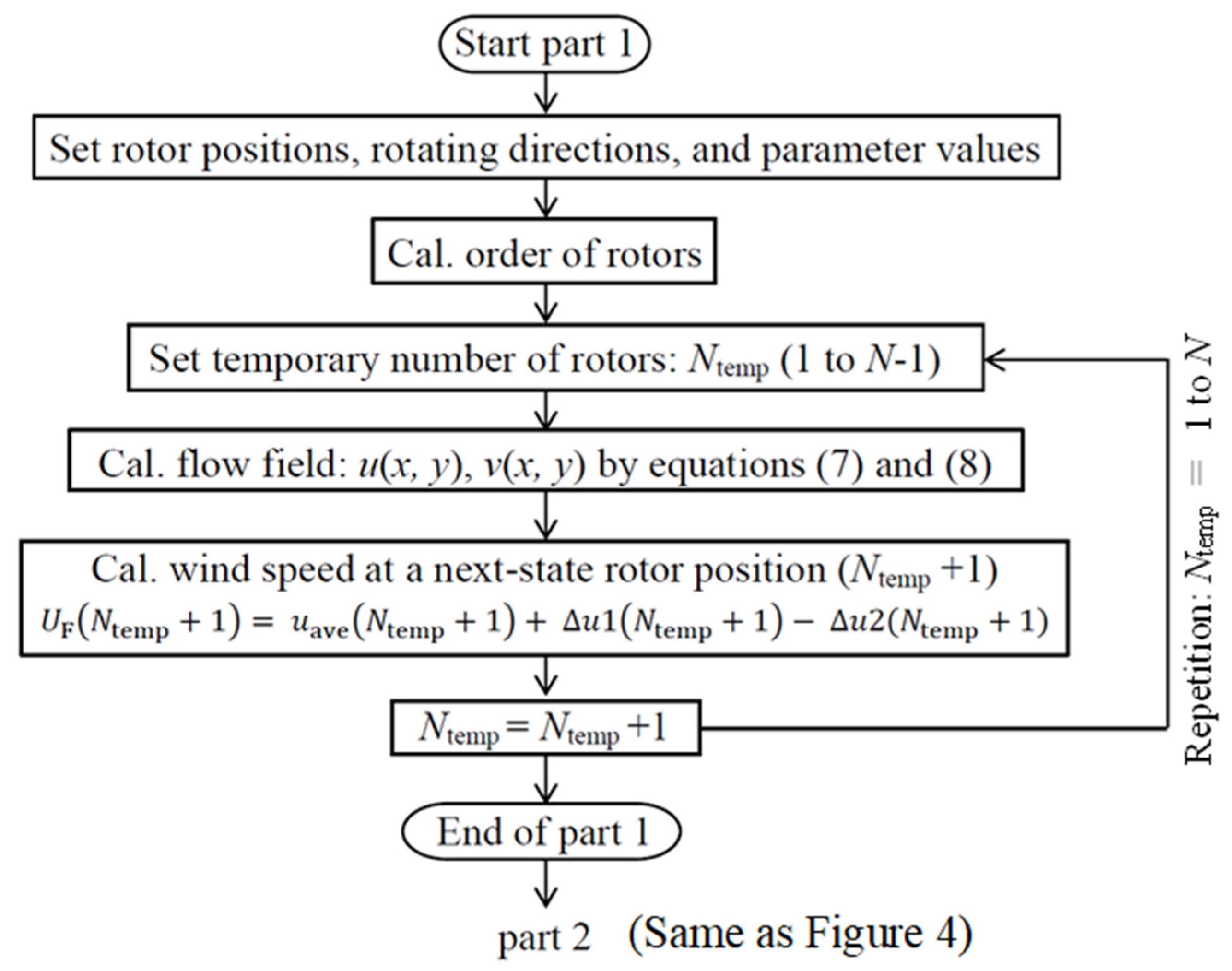

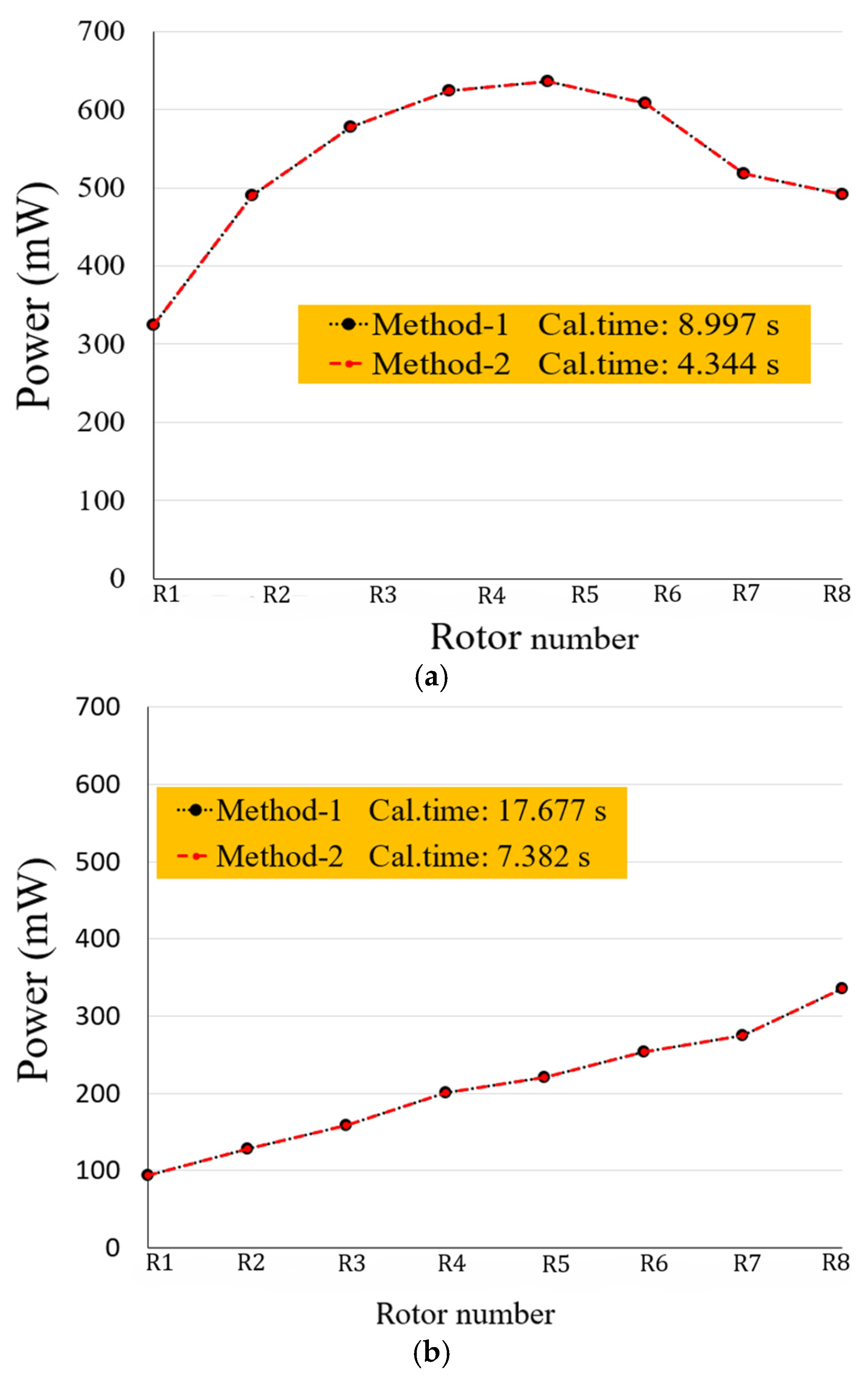

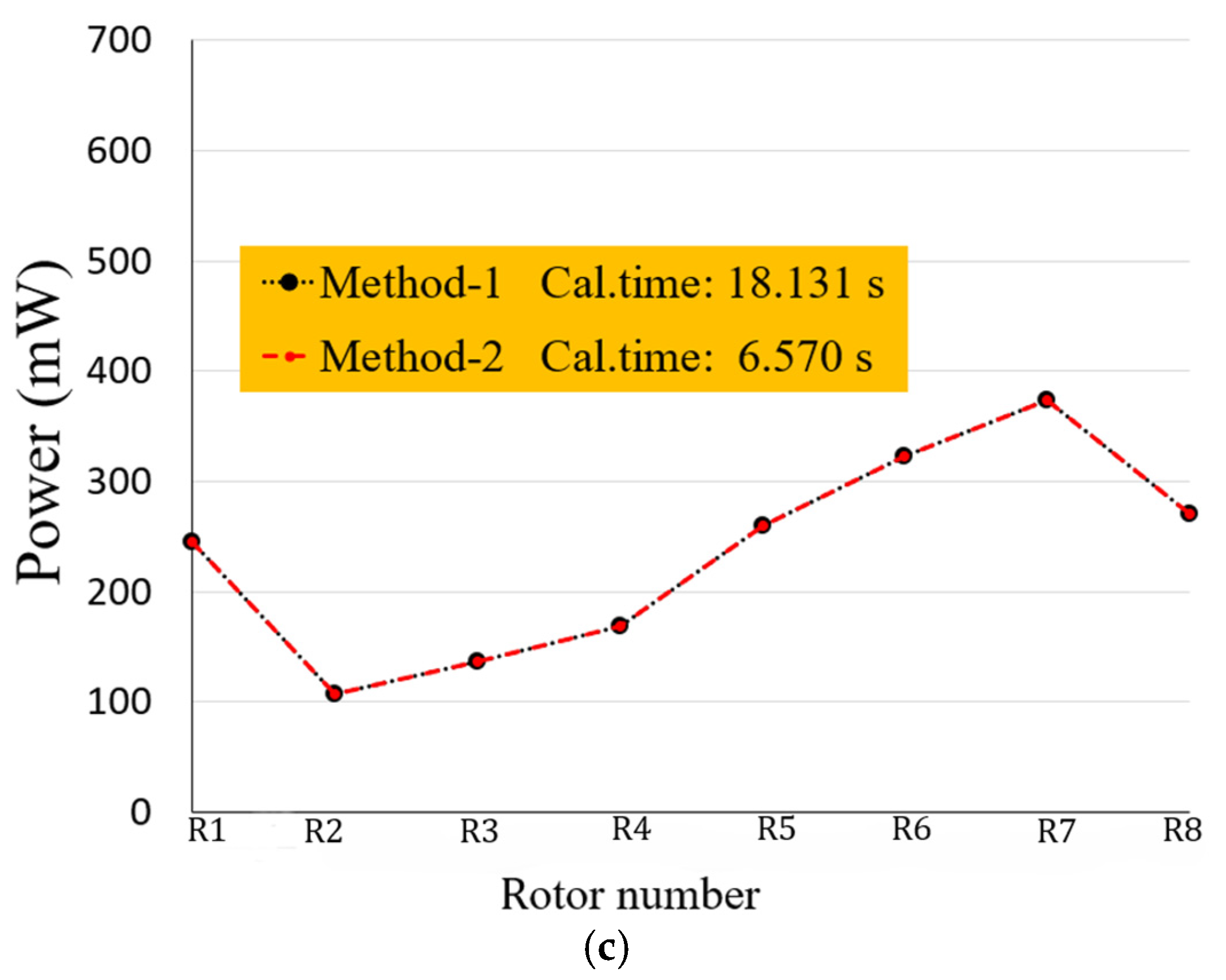

3.1. Comparison Between Method-1 and Method-2

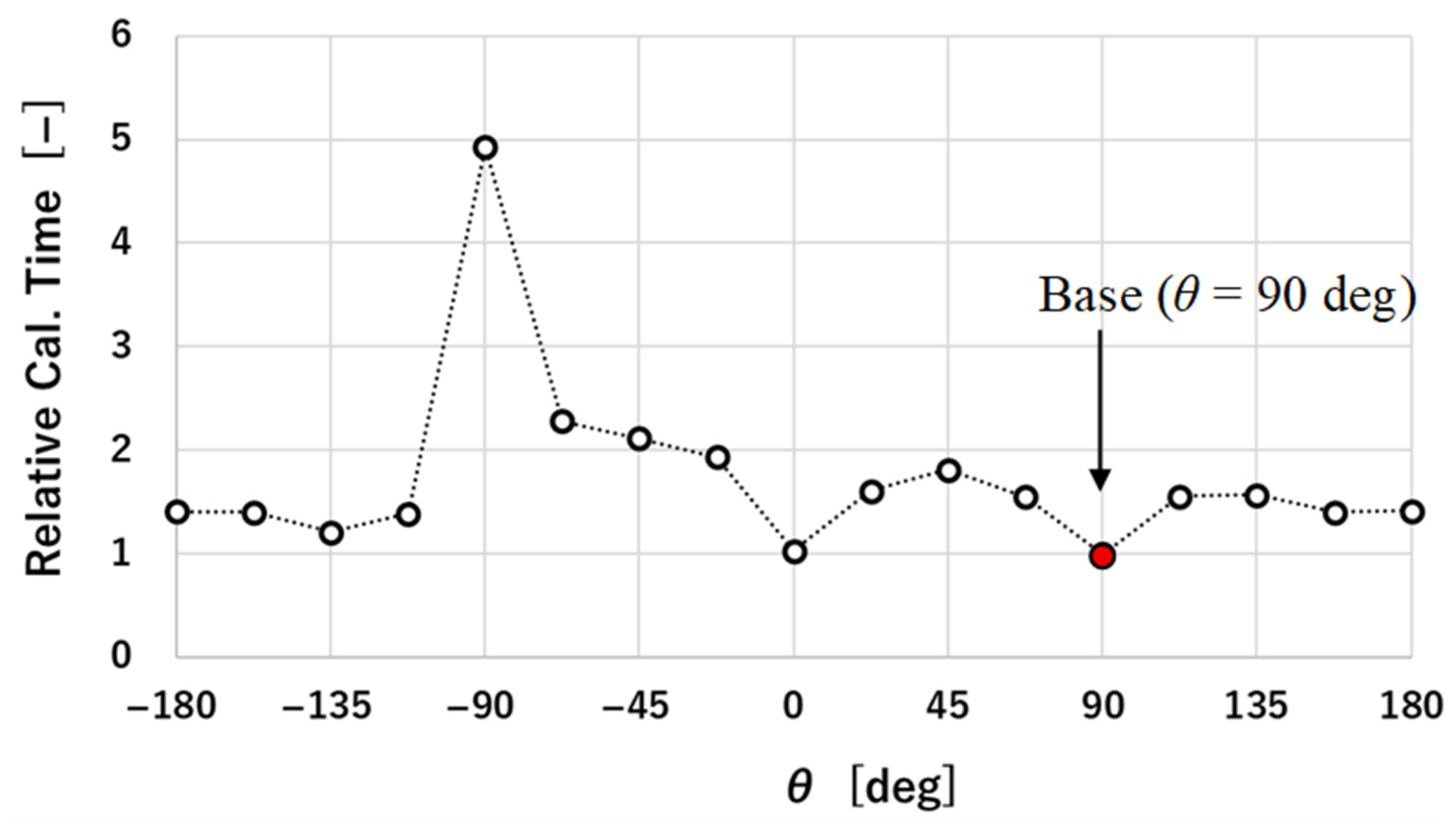

3.2. Effects of Calculation Order

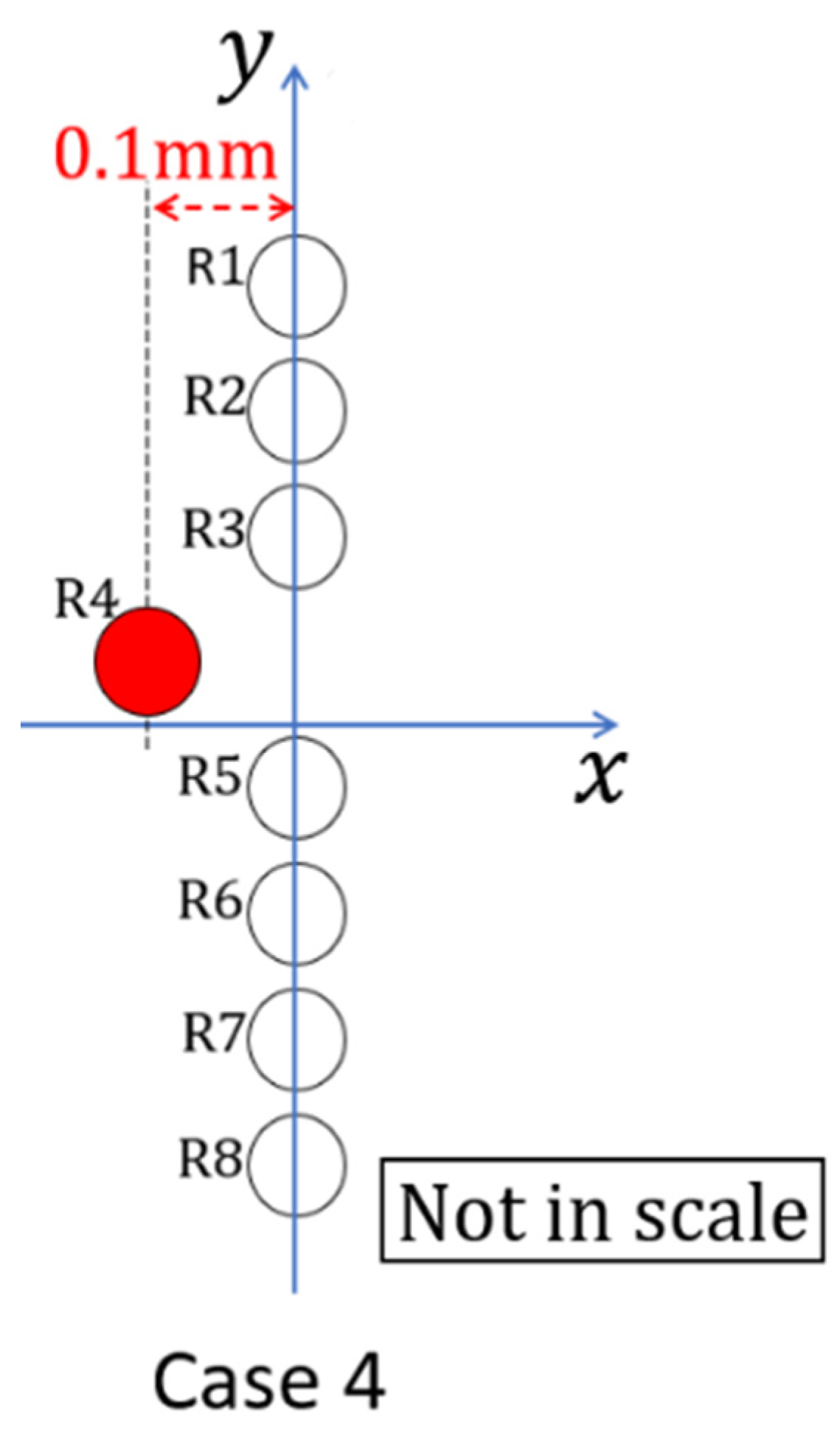

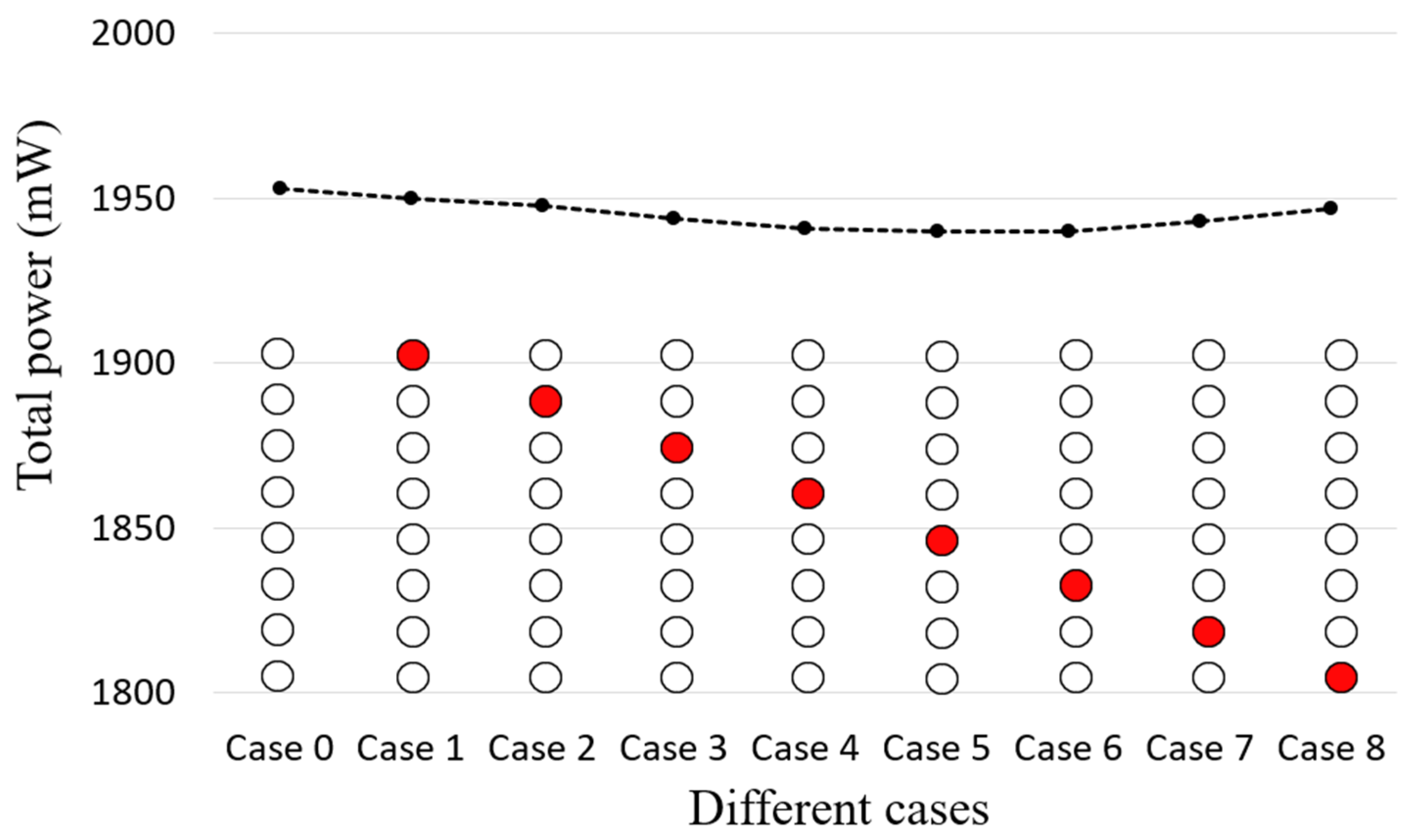

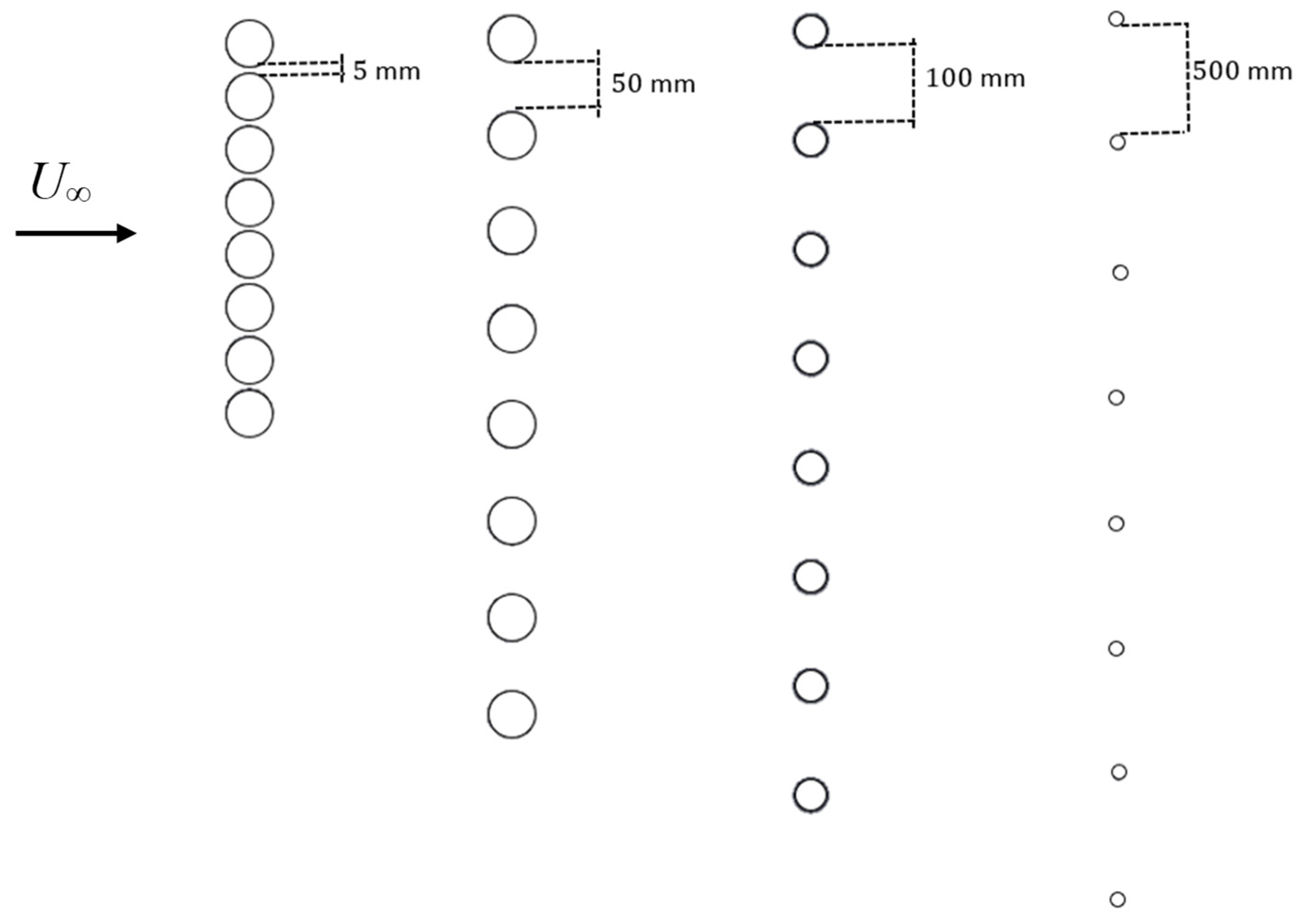

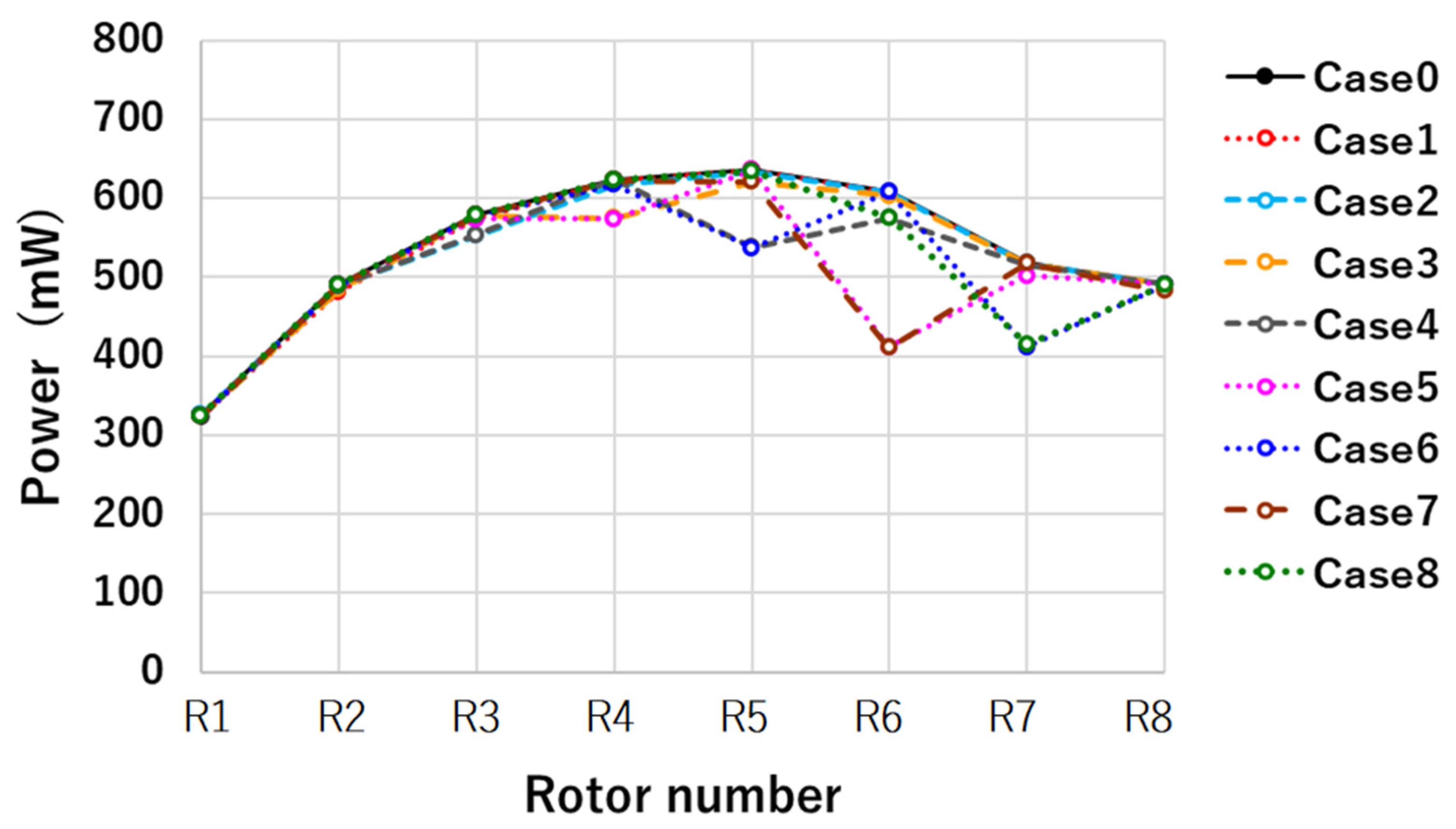

3.3. Sensitivity of Power Prediction to Layout

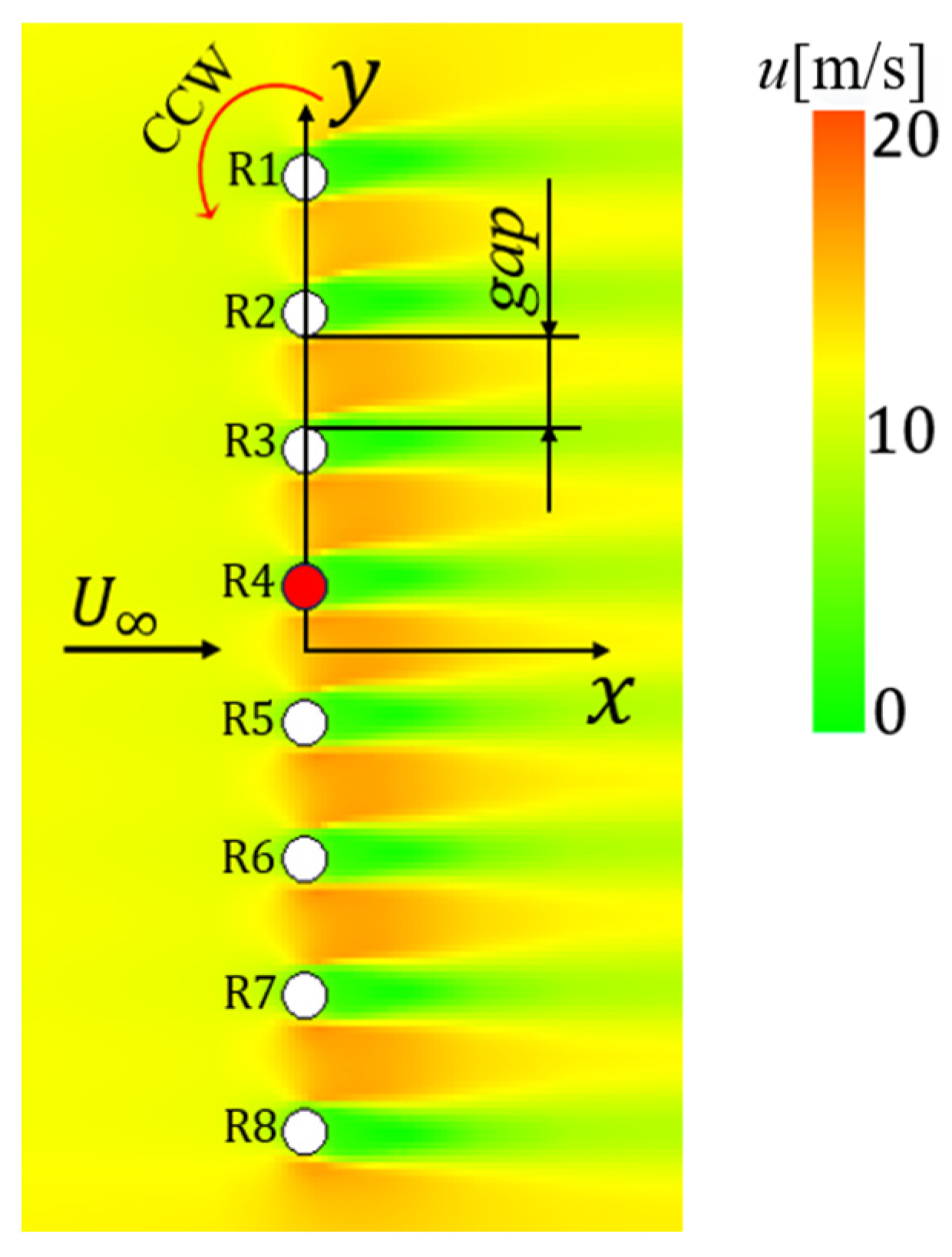

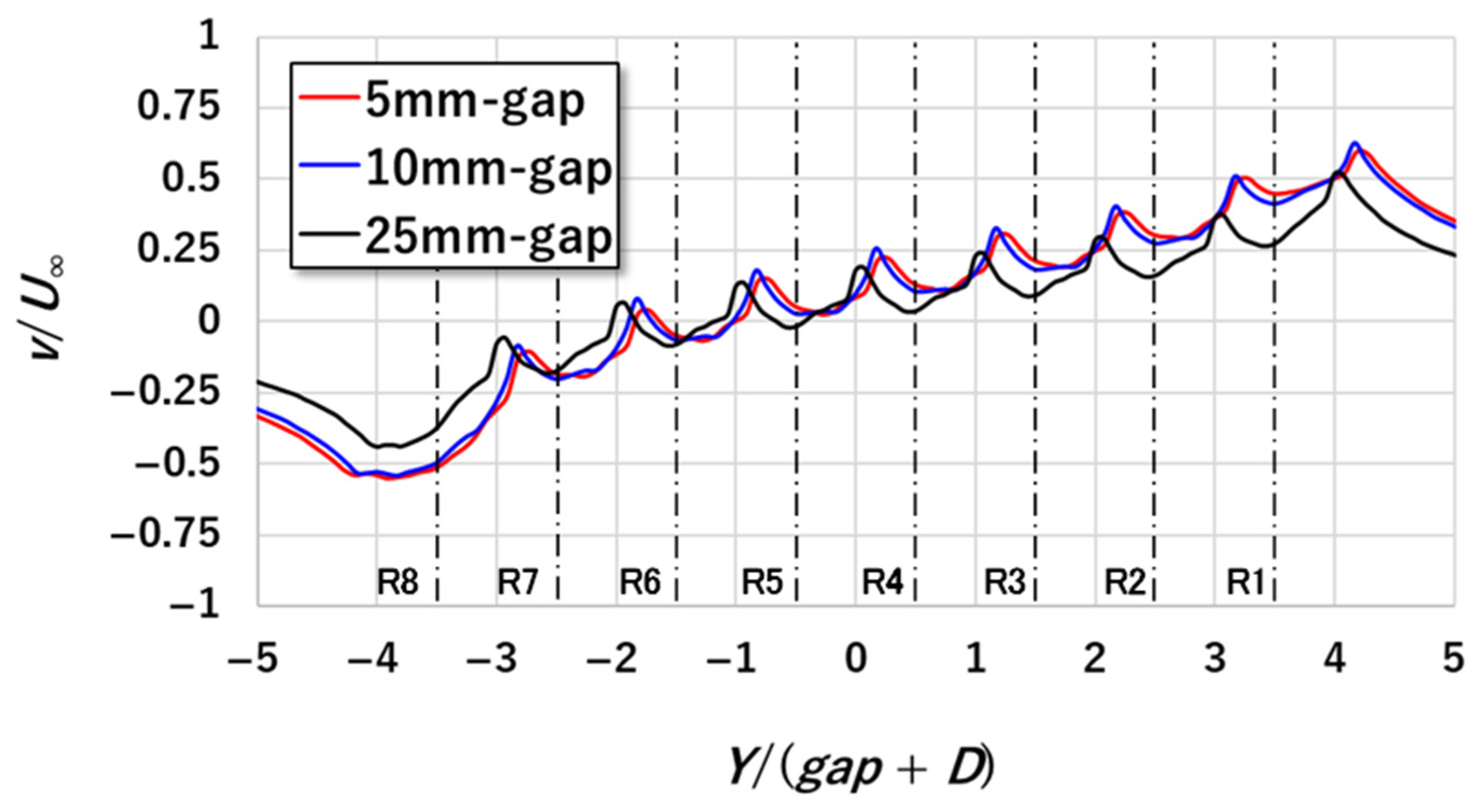

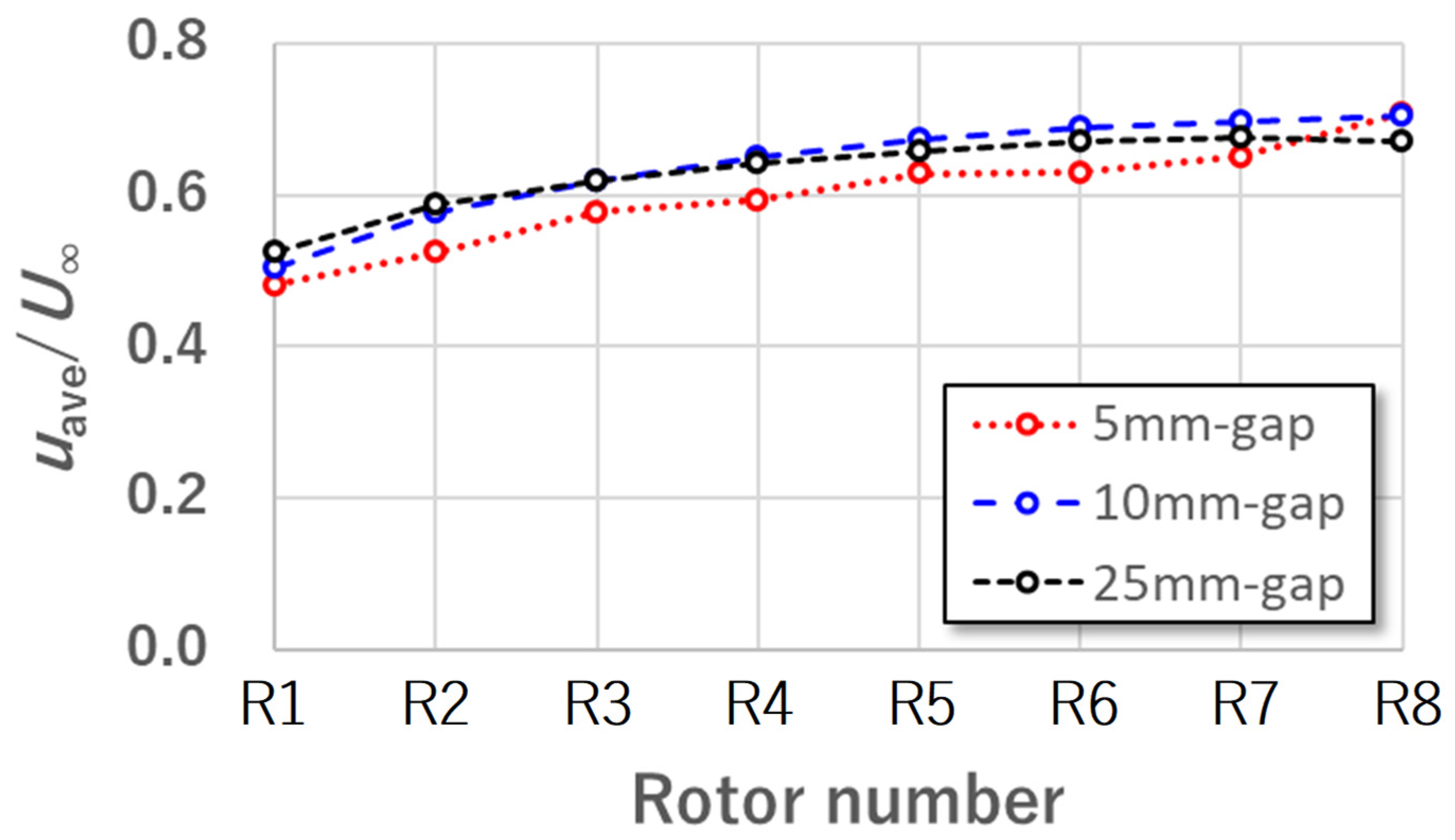

3.4. Gap Dependence of Rotor Power Prediction

4. Conclusions

- ✓

- Method-2 gave exactly the same results as method-1; however it reduced the calculation time by approximately 50–60%.

- ✓

- When the calculation order for the straight-line layout of the eight 2D-VAWT rotors was changed using method-2, the rotor output power was exactly the same, even though the calculation time differed depending on the calculation order.

- ✓

- The calculation order of the tandem layout of the eight rotors from the backward direction (from downstream to upstream) takes about five times as long as the calculation time from the forward order (from upstream to downstream).

- ✓

- When the inter-rotor spacing is small, the total output of the eight rotors can vary by up to 6% if the position of one rotor is changed by just a small distance (0.1 mm). The proposed method has very high sensitivity in a negative sense to the position of the wind turbines.

- ✓

- The power distribution of the eight rotors arranged in parallel in a straight line perpendicular to the main flow approached a constant that equals the power of an isolated single rotor when the inter-rotor distance is as much as ten times the diameter D. However, the power distribution showed relatively large power outputs near the center of the layout when the inter-rotor gap became smaller. For the smallest gap of 5 mm, the power showed uneven distribution.

- ✓

- Two mean velocities, uave (streamwise) and vave (perpendicular), at each rotor center were investigated. However, no behavior was observed that could explain the fluctuation in the power distribution obtained at the minimum inter-rotor gap. It is possible that the local gradient of the streamwise velocity component in the direction perpendicular to the main flow caused the uneven power distribution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCW | Counter Clockwise |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| HAWT | Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine |

| RE | Renewable Energy |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| RN | Repetition Number |

| VAWT | Vertical Axis Wind Turbine |

| WF | Wind Farm |

| temp | Temporary |

| 2D | Two Dimensional |

| 3D | Three Dimensional |

References

- Rajagopalan, R.G.; Rickerl, T.L.; Klimas, P.C. Aerodynamic interference of vertical axis wind turbines. J. Propul. Power 1990, 6, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschivoiu, I. Wind Turbine Design: With Emphasis on Darrieus Concept; Ploytechnic International Press: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2002; pp. 199–226. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Wind_Turbine_Design.html?id=sefVtnVgso0C (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Whittlesey, R.W.; Liska, S.; Dabiri, J.O. Fish schooling as a basis for vertical axis wind turbine farm design. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2010, 5, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiri, J.O. Potential order-of-magnitude enhancement of wind farm power density via counter-rotating vertical axis wind turbine arrays. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2011, 3, 043104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanforlin, S.; Nishino, T. Fluid dynamic mechanisms of enhanced power generation by closely spaced vertical-axis wind turbines. Renew. Energy 2016, 99, 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebzadeh, S.; Rezaeiha, A.; Montazeri, H. Towards optimal layout design of vertical-axis wind-turbine farms: Double rotor arrangements. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 226, 113527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.T.; Mahak, M.; Tzanakis, I. Numerical modelling and optimization of vertical axis wind turbine pairs: A scale up approach. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.E.; Danao, L.A.M.; Cluster, V.V.A.W.T. Varying VAWT cluster Configuration and the effect on individual rotor and overall cluster performance. Energies 2021, 14, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergaerde, A.; De Troyer, T.; Kluczewska-Bordier, J.; Parneix, N.; Silvert, F.; Runacres, M.C. Wind tunnel experiments of a pair of interacting vertical-axis wind turbines. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1037, 072049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergaerde, A.; De Troyer, T.; Standaert, L.; Kluczewska-Bordier, J.; Pitance, D.; Immas, A.; Silvert, F.; Runacres, M.C. Experimental validation of the power enhancement of a pair of vertical-axis wind turbines. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodai, Y.; Tokuda, H.; Hara, Y. Experiments on interaction between six vertical-axis wind turbines in pairs or trios. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2767, 072003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosetti, G.; Poloni, C.; Diviacco, B. Optimization of wind turbine positioning in large windfarms by means of a genetic algorithm. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1994, 51, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.S.; Gonzalez Rodriguez, A.G.; Mora, J.C.; Santos, J.R.; Payan, M.B. Optimization of wind farm turbines layout using an evolutive algorithm. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 1671–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Day, J.; Neumann, F. A fast and effective local search algorithm for optimizing the placement of wind turbines. Renew. Energy 2013, 51, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, H.; Lin, L.; Koo, P. Wind turbine layout optimization using multi-population genetic algorithm and a case study in Hong Kong offshore. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2015, 139, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, H.; Lu, L. Optimization of wind turbine layout position in a wind farm using a newly-developed two-dimensional wake model. Appl. Energy 2016, 174, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, H.; Gao, X. Investigation into spacing restriction and layout optimization of wind farm with multiple types of wind turbines. Energy 2019, 168, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Song, M.X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.F. Wind turbine layout optimization with multiple hub height wind turbines using greedy algorithm. Renew. Energy 2016, 96, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, G. A novel method for wind farm layout optimization based on wind turbine selection. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 193, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Leonardi, S.; Churchfield, M.; Moriarty, P. A Comparison of Actuator Disk and Actuator Line Wind Turbine Models and Best Practices for Their Use. In Proceedings of the 50th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting Including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, Nashville, TN, USA, 9–12 January 2012; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Han, S.; Liu, Y. Multiple wind turbine wakes modeling considering the faster wake recovery in overlapped wakes. Energies 2019, 12, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Agarwal, R. Optimal placement of horizontal- and vertical-axis wind turbines in a wind farm for maximum power generation using a genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 5th International Conference on Energy Sustainability, Washington, DC, USA, 7–10 August 2011; pp. 2033–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamalek, A.; Runacres, M.C.; De Troyer, T. Effect of turbulence on the performance of a pair of vertical-axis wind turbines. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2265, 022098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzaro, D.; Bedon, G.; Pisinger, D. Vertical axis wind turbine layout optimization. Energies 2023, 16, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tavernier, D.; Ferreira, C.; Li, A.; Paulsen, U.S.; Madsen, H.A. Towards the understanding of vertical-axis wind turbines in double-rotor configuration. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1037, 022015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadani, L.N. Vertical axis wind turbines in cluster configurations. Ocean Eng. 2023, 272, 113855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereu, R.; Federici, D.; Ferrari, G.; Schito, P.; Inzoli, F. Parametric numerical study of Savonius wind turbine interaction in a linear array. Renew. Energy 2017, 113, 1320–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranarote, J.; Hara, Y.; Furukawa, M.; Jodai, Y. Method to predict outputs of two-dimensional VAWT rotors by using wake model mimicking the CFD-created flow field. Energies 2022, 15, 5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C.R.; Starke, G.M.; Meneveau, C.; Gayme, D.F. A wake modeling paradigm for wind farm design and control. Energies 2019, 12, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Moral, M.S.; Ide, A.; Jodai, Y. Fast simulation of the flow field in a VAWT wind farm using the numerical data obtained by CFD analysis for a single rotor. Energies 2025, 18, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Jodai, Y.; Okinaga, T.; Furukawa, M. Numerical analysis of the dynamic interaction between two closely spaced vertical-axis wind turbines. Energies 2021, 14, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layout (θ) | Fixed Order | Cal. Time | Ave. Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0° | R1→R2→R3→R4→R5→R6→R7→R8 | 4.400 s | 0.534 W |

| R8→R7→R6→R5→R4→R3→R2→R1 | 6.161 s | ||

| R4→R5→R3→R6→R2→R7→R1→R8 | 5.223 s | ||

| 45° | R1→R2→R3→R4→R5→R6→R7→R8 | 7.481 s | 0.208 W |

| R8→R7→R6→R5→R4→R3→R2→R1 | 5.138 s | ||

| −45° | R1→R2→R3→R4→R5→R6→R7→R8 | 9.069 s | 0.236 W |

| R8→R7→R6→R5→R4→R3→R2→R1 | 6.719 s |

| Case | Shifted Rotor |

|---|---|

| Case 0 | No shift |

| Case 1 | R1 |

| Case 2 | R2 |

| Case 3 | R3 |

| Case 4 | R4 |

| Case 5 | R5 |

| Case 6 | R6 |

| Case 7 | R7 |

| Case 8 | R8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moral, M.S.; Hara, Y.; Jodai, Y. Improvement of Fast Simulation Method of the Flow Field in Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Wind Farms and Consideration of the Effects of Turbine Selection Order. Energies 2025, 18, 6294. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236294

Moral MS, Hara Y, Jodai Y. Improvement of Fast Simulation Method of the Flow Field in Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Wind Farms and Consideration of the Effects of Turbine Selection Order. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6294. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236294

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoral, Md. Shameem, Yutaka Hara, and Yoshifumi Jodai. 2025. "Improvement of Fast Simulation Method of the Flow Field in Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Wind Farms and Consideration of the Effects of Turbine Selection Order" Energies 18, no. 23: 6294. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236294

APA StyleMoral, M. S., Hara, Y., & Jodai, Y. (2025). Improvement of Fast Simulation Method of the Flow Field in Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine Wind Farms and Consideration of the Effects of Turbine Selection Order. Energies, 18(23), 6294. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236294