Machine Learning for Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Integrated with Energy Storage Systems: A Scientometric Analysis, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Process

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis Methodology

2.3. Research Design and Protocol for Systematic Review

- Explicitly addressed PV power forecasting in systems integrating an energy storage system (ESS) (i.e., PV–ESS context).

- Employed machine learning (ML) or artificial intelligence (AI) to perform the forecast.

- Were original, peer-reviewed research (journal articles or peer-reviewed conference papers).

- Were published in English or Spanish.

- Were published within the predefined time window (full corpus 2010–July 2025; analyses focused on recent years as specified in the protocol).

- Did not jointly address both PV forecasting and ESS integration/operation (e.g., PV forecasting without storage, or battery management without a forecasting component).

- Did not use ML/AI for forecasting (i.e., relied solely on physical/NWP or traditional statistical baselines without ML).

- Were secondary or non–peer-reviewed literature (reviews, book chapters, theses, patents, gray literature) or conference abstracts without a full peer-reviewed paper.

- Were published in languages other than English or Spanish.

- Were duplicates/multiple reports of the same study (only the most complete version was retained).

- Were outside the thematic scope on screening or failed full-text eligibility due to insufficient methodological detail, superficial use of ML, or no substantively relevant role for ESS.

- Were outside the temporal window defined for the review.

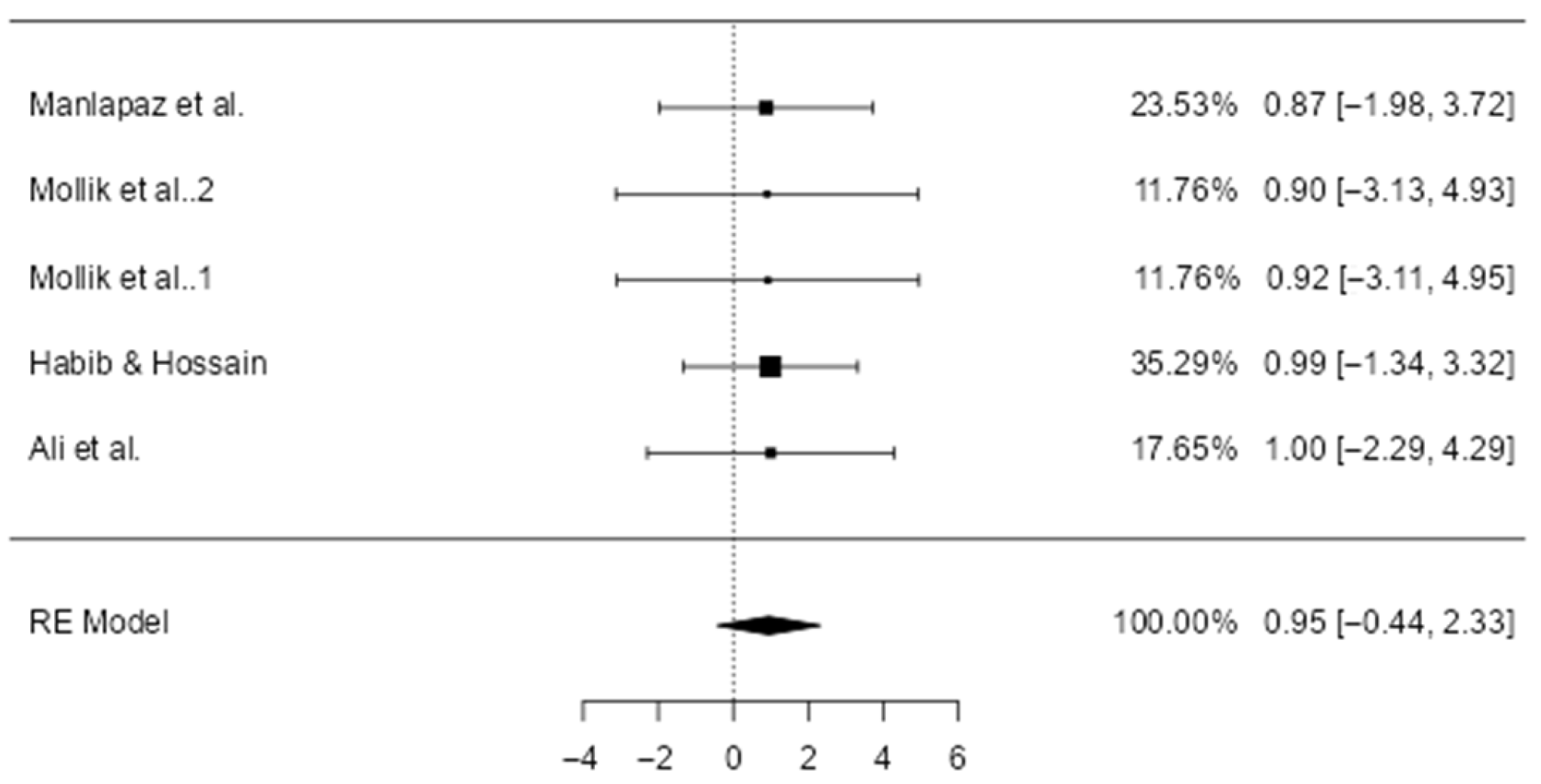

- Only studies that clearly reported the coefficient of determination (R2) as a forecasting performance metric were eligible for pooling (most otherwise-eligible papers reported heterogeneous metrics such as RMSE, MAE, MAPE, etc.). This yielded k = 5 studies in the effect analysis.

2.4. Research Questions

2.5. Sources of Information and Dates

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

2.8. Synthesis and Analysis

2.9. Meta-Analysis Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Yearly Publications and Citations Trends

3.2. Top Leading Journals

3.3. Most Cited Publications

3.4. Research Trends and Future Directions

3.5. Systematic Review

3.5.1. Fundamentals of PV-BESS Hybrid Systems

3.5.2. Machine Learning Approaches for PV Generation Forecasting

Statistical and Regression Models

Classical Machine Learning Models

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)

Deep Learning Models for Time Series

3.5.3. ML/DL Models in Prediction, Grid Operation, Energy Control, and Battery Management with AI

3.6. Meta-Analysis

3.6.1. Weights for Analysis

3.6.2. Combined Effect

3.6.3. Heterogeneity

3.6.4. Publication Bias

3.6.5. Equivalence Tests (TOST)

4. Discussion

4.1. Superiority of ML/DL Models in PV

4.2. Future Directions for Improving the Forecast

4.3. Adaptive Control and Integrated Operation

4.4. Interpretability and Computational Efficiency

4.5. Extension to Other Technologies

4.6. Operational and Economic Implications of Forecasting Errors in PV–ESS

4.7. Forecasting Horizons and Their Operational Relevance in PV–ESS

4.8. Challenges in Integrating Machine Learning-Based Forecasting with Energy Storage System Control

4.9. Synthesis of Findings

4.9.1. Global Research Trends

4.9.2. Methodological Quality

4.9.3. Aggregated Model Performance

4.9.4. Gaps in ML–ESS Integration

4.10. Limitations

4.10.1. Methodological Limitations

4.10.2. Limitations of the Meta-Analysis

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Standardize benchmarks (reference datasets, common horizons, and unified metrics) to fairly assess different models and quantify their benefits for ESS integration.

- (2)

- Incorporate robustness and resilience criteria—e.g., performance under atypical events, missing data, and domain shift—alongside conventional average error metrics.

- (3)

- Close the forecast–action loop through deep reinforcement learning for adaptive charge/discharge management.

- (4)

- Deploy XAI techniques to enhance interpretability and operational acceptance among system operators.

- (5)

- Expand data availability in poorly instrumented sites through controlled synthetic data generation while maintaining bias auditing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network (a type of machine learning model) |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (a statistical time series model) |

| ARIMAX | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average with Exogenous variables |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System (refers specifically to battery-based ESS) |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| BR | Bayesian Regularization (an algorithm/training method for neural networks) |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network (a type of deep learning model) |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DoD | Depth of Discharge |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| EVCS | Electric Vehicle Charging Station |

| FFNN | Feed-Forward Neural Network |

| FL | Fuzzy Logic |

| FLC | Fuzzy Logic Controller |

| PV-ESS | Photovoltaic + Energy Storage System |

| REML | Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| UDDS | Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule |

| UPQC | Unified Power Quality Conditioner |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

References

- Benitez, I.B.; Singh, J.G. A comprehensive review of machine learning applications in forecasting solar PV and wind turbine power output. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2025, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.F.L.; de Mattos Neto, P.S.G.; Siqueira, H.V.; Santos, D.S.d.O., Jr.; Lima, A.R.; Madeiro, F.; Dantas, D.A.P.; Cavalcanti, M.d.M.; Pereira, A.C.; Marinho, M.H.N. Forecasting methods for photovoltaic energy in the scenario of battery energy storage systems: A comprehensive review. Energies 2023, 16, 6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalbiakhlua, K.; Deb, S.; Singh, K.R.; Datta, S.; Shuaibu, H.A.; Ustun, T.S. Deep learning based solar forecasting for optimal PV BESS sizing in ultra fast charging stations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, A.; Hanif, M.F.; Naveed, M.S.; Hassan, M.T.; Gul, M.; Husnain, N.; Mi, J. AI-Driven precision in solar forecasting: Breakthroughs in machine learning and deep learning. AIMS Geosci. 2024, 10, 684–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xue, B.; Li, B.; Zhu, J.; Song, W. Ensemble learning with support vector machines algorithm for surface roughness prediction in longitudinal vibratory ultrasound-assisted grinding. Precis. Eng. 2024, 88, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lv, J.; Lv, P.; Cheng, Y. Deep learning-based electricity theft detection for active distribution networks with high photovoltaic penetration. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 126, 110551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, W.; Chen, W.; Zhang, M. RTI-Net: Physics-informed deep learning for photovoltaic power forecasting. Renew. Energy 2025, 256, 124152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhao, M.; Hao, Y.; Ji, C. Real-time mooring tension prediction for a floating offshore photovoltaic system using a CNN-Bi-LSTM hybrid neural network. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 340, 122322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Deep Learning and Neural Networks: Decision-Making Implications. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondón-Cordero, V.H.; Montuori, L.; Alcázar-Ortega, M.; Siano, P. Advancements in hybrid and ensemble ML models for energy consumption forecasting: Results and challenges of their applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 224, 116095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathima, A.H.; Palanisamy, K. Optimization in microgrids with hybrid energy systems—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.K.; Crasta, H.R.; Kausthubha, K.; Gowda, C.; Rao, A. Battery monitoring system using machine learning. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.K.; Karmaker, A.K. Optimizing PV power utilization in standalone battery systems with forecast-based charging management strategy. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2025, 8, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bampoulas, A.; Pallonetto, F.; Mangina, E.; Finn, D.P. A Bayesian deep-learning framework for assessing the energy flexibility of residential buildings with multicomponent energy systems. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khortsriwong, N.; Boonraksa, P.; Boonraksa, T.; Fangsuwannarak, T.; Boonsrirat, A.; Pinthurat, W.; Marungsri, B. Performance of deep learning techniques for forecasting PV power generation: A case study on a 1.5 MWp floating PV power plant. Energies 2023, 16, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Feng, X.; Sun, Y.; Pan, R. Hybrid Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning Framework for Power Prediction and Optimization in Photovoltaic Storage Systems. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information Technologies and Electrical Engineering, Guangzhou China, 1–3 November 2024; pp. 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- Babay, M.-A.; Adar, M.; Chebak, A.; Mabrouki, M. Forecasting green hydrogen production: An assessment of renewable energy systems using deep learning and statistical methods. Fuel 2025, 381, 133496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksan, F.; Suresh, V.; Janik, P. Optimal capacity and charging scheduling of battery storage through forecasting of photovoltaic power production and electric vehicle charging demand with deep learning models. Energies 2024, 17, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.C.; Roy, A.K.; Sinha, N. GA based frequency controller for solar thermal–diesel–wind hybrid energy generation/energy storage system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2012, 43, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawoud, S.M.; Lin, X.; Okba, M.I. Hybrid renewable microgrid optimization techniques: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, D.-H. Federated reinforcement learning for energy management of multiple smart homes with distributed energy resources. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 18, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Choi, D.-H.; Kim, J. Cooperative management for PV/ESS-enabled electric vehicle charging stations: A multiagent deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 16, 3493–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husein, M.; Chung, I.-Y. Day-ahead solar irradiance forecasting for microgrids using a long short-term memory recurrent neural network: A deep learning approach. Energies 2019, 12, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kow, K.W.; Wong, Y.W.; Rajkumar, R.K.; Rajkumar, R.K. A review on performance of artificial intelligence and conventional method in mitigating PV grid-tied related power quality events. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Ye, Z.; Gao, Y.; Ye, Z.; Peng, Y.; Yu, N. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for voltage control with coordinated active and reactive power optimization. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 4873–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, D.-H. Energy management of smart home with home appliances, energy storage system and electric vehicle: A hierarchical deep reinforcement learning approach. Sensors 2020, 20, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarita, K.; Kumar, S.; Vardhan, A.S.S.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Saket, R.K.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Hossain, E. Power enhancement with grid stabilization of renewable energy-based generation system using UPQC-FLC-EVA technique. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 207443–207464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, D.-H. Reinforcement learning-based energy management of smart home with rooftop solar photovoltaic system, energy storage system, and home appliances. Sensors 2019, 19, 3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Sheikh, M.R.I.; Biswas, D.; Al Mamun, A.; Hossen, M.J. Optimizing Renewable Energy-Based Grid-Connected Hybrid Microgrid for Residential Applications in Bangladesh: Predictive Modeling for Renewable Energy, Grid Stability and Demand Response Analysis. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.X.; Lu, L.; Burnett, J. Weather data and probability analysis of hybrid photovoltaic–wind power generation systems in Hong Kong. Renew. Energy 2003, 28, 1813–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, H.; Maduabuchi, C.; Okoli, K.; Alobaid, M.; Alghassab, M.; Alsafran, A.S.; Makki, E.; Alkhedher, M. Latest advancements in solar photovoltaic-thermoelectric conversion technologies: Thermal energy storage using phase change materials, machine learning, and 4E analyses. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 1050785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Khan, S.Z. Assessment of renewable energy: Status, challenges, COVID-19 impacts, opportunities, and sustainable energy solutions in Africa. Energy Built Environ. 2022, 3, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, H.; Nassar, Y.F.; Hafez, A.; Sherbiny, M.K.; Ali, A.F.M. Optimal design and economic feasibility of rooftop photovoltaic energy system for Assuit University, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepe, İ.F.; Demirtaş, M.; Irmak, E.; Bayindir, R. Eco-friendly energy storage systems based demand side management for rural microgrid by dandelion optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 13th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Nagasaki, Japan, 9–13 November 2024; pp. 1657–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Cagigal, M.; Gutiérrez, A.; Monasterio-Huelin, F.; Caamaño-Martín, E.; Masa, D.; Jiménez-Leube, J. A semi-distributed electric demand-side management system with PV generation for self-consumption enhancement. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 2659–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, R.K. Smart Solar PV Inverters with Advanced Grid Support Functionalities; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khayyat, M.M.; Sami, B. Energy community management based on artificial intelligence for the implementation of renewable energy systems in smart homes. Electronics 2024, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, N.; Gupta, D.; Shanmugam, P.K.; Nersisson, R.; Gabriel, G.A.; Daniel, G.E. Deep-cycle battery sizing and strategic battery management in solar-EV systems using UDDS drive cycles with real-time environment. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 35350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elweddad, M.A.; Guneser, M.T. Intelligent energy management and prediction of micro grid operation based on machine learning algorithms and genetic algorithm. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2022, 12, 2002–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustono, I. State of Charge Prediction of Lead Acid Battery Using Transformer Neural Network for Solar Smart Dome 4.0. 2022. Available online: https://engrxiv.org/preprint/view/2606/version/3774 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Almughram, O.; Abdullah ben Slama, S.; Zafar, B.A. A reinforcement learning approach for integrating an intelligent home energy management system with a vehicle-to-home unit. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, I.; Salisu, S.; Mas’ud, A.A.; Musa, U.; Jabire, A.H.; Muhammad-Sukki, F.; Mas’ud, I.A. An Overview of Current Optimization Approaches for Hybrid Energy Systems Combining Solar Photovoltaic and Wind Technologies. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 4633–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, C.R.; Mani, G.; Stonier, A.A.; Peter, G.; Kumaresan, P.; Ganji, V. An extensive critique on expert system control in solar photovoltaic dominated microgrids. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2025, 19, e12875. [Google Scholar]

- Odoi-Yorke, F.; Baah, B.; Kissi-Boateng, R.; Opoku, R.; Effah, F.B. Unlocking the potential of redundant energy from solar photovoltaic systems: Navigating global research trends, innovations, and future directions. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 6362–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokolo, S.C.; Obiwulu, A.U.; Okonkwo, P.C.; Orji, R.; Alsenani, T.R.; Mansir, I.B.; Orji, C. Machine learning and physics-based model hybridization to assess the impact of climate change on single-and dual-axis tracking solar-concentrated photovoltaic systems. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2025, 138, 103881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap Singh, A.; Kumar, Y.; Sawle, Y.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Malik, H.; Pedro García Márquez, F. Development of artificial Intelligence-Based adaptive vehicle to grid and grid to vehicle controller for electric vehicle charging station. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, D.; Josh, F.T. A comprehensive review on optimization and artificial intelligence algorithms for effective battery management in EVs. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Eng. Telecommun. 2023, 12, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakitalima, I.J.; Rizwan, M.; Kumar, N. Integrating Solar Photovoltaic Power Source and Biogas Energy-Based System for Increasing Access to Electricity in Rural Areas of Tanzania. Int. J. Photoenergy 2023, 2023, 7950699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, K.G.; Di Santo, S.G.; Monaro, R.M.; Saidel, M.A. Active demand side management for households in smart grids using optimization and artificial intelligence. Measurement 2018, 115, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewdornhan, N.; Chatthaworn, R. Predictive energy management for microgrid using multi-agent deep deterministic policy gradient with random sampling. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 95071–95090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlapaz, J.G.C.; Reyes, D.M.; Buensuceso, C.P.L.; Peña, R.A.S.; Parocha, R.C.; Macabebe, E.Q.B. Optimization and simulation of a grid-connected PV system using load forecasting methods: A case study of a university building. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1199, 12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadeeja, F.P.; Radha, M.; Vanitha, G.; Nirmala, D.M.; Mahendiran, R.; Vishnu, S.S. Daily Solar Power Prediction Using Machine Learning: A Model Wise Comparative Study. 2025. Available online: https://www.horizonepublishing.com/index.php/PST/article/view/8861 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Habib, M.A.; Hossain, M.J. Advanced feature engineering in microgrid PV forecasting: A fast computing and data-driven hybrid modeling framework. Renew. Energy 2024, 235, 121258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouili, O.; Hanine, M.; Louzazni, M.; Flores, M.A.L.; Villena, E.G.; Ashraf, I. Evaluating the impact of deep learning approaches on solar and photovoltaic power forecasting: A systematic review. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2025, 59, 101735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Kumar, D.; Ali, N.; Lehtonen, M. Optimal deep learning based aggregation of TCLs in an inverter fed stand-alone microgrid for voltage unbalance mitigation. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 210, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, R.M.; Islam, M.S.; Basher, E. Forecasting and optimization of a residential off-grid solar photovoltaic-battery energy storage system. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2025, 26, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokonuzzaman, M.; Rahman, S.; Hannan, M.A.; Mishu, M.K.; Tan, W.-S.; Rahman, K.S.; Pasupuleti, J.; Amin, N. Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm-based solar PV energy integrated internet of home energy management system. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Nayak, J.; Naik, B.; Abraham, A. Deep learning in electrical utility industry: A comprehensive review of a decade of research. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 96, 104000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, A.; Caputo, G.; Balog, I.; Fabozzi, S.; Adinolfi, G.; Pascarella, F.; Leanza, G.; Graditi, G.; Valenti, M. Machine learning and weather model combination for PV production forecasting. Energies 2024, 17, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.N.S.; Diaz, V.N.S.; Ando, O.H.; Ledesma, J.J.G. Analysis of the Technical Feasibility of Using Artificial Intelligence for Smoothing Active Power in a Photovoltaic System Connected to the Power System. Brazilian Arch. Biol. Technol. 2021, 64, e21210196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srilakshmi, K.; Sujatha, C.N.; Balachandran, P.K.; Mihet-Popa, L.; Kumar, N.U. Optimal design of an artificial intelligence controller for solar-battery integrated UPQC in three phase distribution networks. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarathkumar, T.V.; Goswami, A.K.; Khan, B.; Shoush, K.A.; Ghoneim, S.S.M.; Ghaly, R.N.R. Forecasting of virtual power plant generating and energy arbitrage economics in the electricity market using machine learning approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Obregon, J.; Park, H.; Jung, J.-Y. Multi-step photovoltaic power forecasting using transformer and recurrent neural networks. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 200, 114479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabawa, P.; Choi, D.-H. Safe deep reinforcement learning-assisted two-stage energy management for active power distribution networks with hydrogen fueling stations. Appl. Energy 2024, 375, 124170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzani, S.; Prakash, A.K.; Wang, Z.; Agarwal, S.; Pritoni, M.; Kiran, M.; Brown, R.; Granderson, J. Controlling distributed energy resources via deep reinforcement learning for load flexibility and energy efficiency. Appl. Energy 2021, 304, 117733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Guo, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, C.; Qiao, G.; Chaomurilige; Ding, Y. Interdependent design and operation of solar photovoltaics and battery energy storage for economically viable decarbonisation of local energy systems. Energy AI 2025, 20, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherri, M.; Tadepalli, S.; Otto, S.; Lenneman, A.; Babcock, N. Optimizing fault detection in battery energy storage systems through data-driven modeling. J. Energy Storage 2025, 121, 116466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugapriya, V.; Vidyasagar, S.; Raju, D.K. Post-fault voltage recovery and voltage instability assessment of DC microgrid with Deep Transfer-learning Convolution Neural Network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 239, 111234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Chaturvedi, D.K.; Ibraheem; Sharma, G.; Bokoro, P.N.; Kumar, R. Application of Twisting Controller and Modified Pufferfish Optimization Algorithm for Power Management in a Solar PV System with Electric-Vehicle and Load-Demand Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shern, S.J.; Sarker, M.T.; Ramasamy, G.; Thiagarajah, S.P.; Al Farid, F.; Suganthi, S.T. Artificial Intelligence-Based Electric Vehicle Smart Charging System in Malaysia. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Shao, S. Numerical assessment and optimization of photovoltaic-based hydrogen-oxygen Co-production energy system: A machine learning and multi-objective strategy. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y. An incremental photovoltaic power prediction method considering concept drift and privacy protection. Appl. Energy 2023, 351, 121919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraftabzadeh, S.M.; Colombo, C.G.; Longo, M.; Foiadelli, F. A day-ahead photovoltaic power prediction via transfer learning and deep neural networks. Forecasting 2023, 5, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnard, Q.; Ragot, N. Continual Learning for Time Series Forecasting: A First Survey. Eng. Proc. 2024, 68, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, C.; Laaksonen, H.; Redondo-Iglesias, E.; Pelissier, S. Aging aware adaptive control of Li-ion battery energy storage system for flexibility services provision. J. Energy Storage 2023, 57, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattarzadeh, S.; Padisala, S.K.; Shi, Y.; Mishra, P.P.; Smith, K.; Dey, S. Feedback-based fault-tolerant and health-adaptive optimal charging of batteries. Appl. Energy 2023, 343, 121187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, W.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Hussain, A.; Hu, E.; Zhang, J.; Mao, Z.; Chen, Z. State of health estimation and battery management: A review of health indicators, models and machine learning. Materials 2025, 18, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, R.; Dodge, J.; Smith, N.A.; Etzioni, O. Green ai. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greg, J. Quantization and Pruning Strategies for Energy-Efficient TinyML Models. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/395994840_Quantization_and_Pruning_Strategies_for_Energy-Efficient_TinyML_Models (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Popovic, G.; Spalevic, Z.; Jovanovic, L.; Zivkovic, M.; Stosic, L.; Bacanin, N. Optimizing lightweight recurrent networks for solar forecasting in tinyml: Modified metaheuristics and legal implications. Energies 2024, 18, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Park, J.; Na, S.-I.; Choi, H.S.; Bu, B.-S.; Kim, J. An analysis of battery degradation in the integrated energy storage system with solar photovoltaic generation. Electronics 2020, 9, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthisinghe, C.; Mickelson, E.; Kirschen, D.S.; Shih, N.; Gibson, S. Improved PV forecasts for capacity firming. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 152173–152182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, C.; Egging-Bratseth, R. Battery degradation: Impact on economic dispatch. Energy Storage 2024, 6, e588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grane, M.; Cornejo, M.; Hesse, H.; Jossen, A. Accounting for Subsystem Aging Variability in Battery Energy Storage System Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.04813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Botterud, A.; Zhang, K.; Ding, Q. Stochastic coordinated operation of wind and battery energy storage system considering battery degradation. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean. Energy 2016, 4, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfs, P.; Emami, K.; Lin, Y.; Palmer, E. Load forecasting for diurnal management of community battery systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean. Energy 2018, 6, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadis, P.; Ntomalis, S.; Atsonios, K.; Nesiadis, A.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Grammelis, P. Energy management and techno-economic assessment of a predictive battery storage system applying a load levelling operational strategy in island systems. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 2709–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Harrold, D.; Fan, Z.; Morstyn, T.; Healey, D.; Li, K. Deep reinforcement learning-based energy storage arbitrage with accurate lithium-ion battery degradation model. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4513–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz, A.; Grzebyk, D.; Ziar, H.; Isabella, O. Trends and gaps in photovoltaic power forecasting with machine learning. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantillo-Luna, S.; Moreno-Chuquen, R.; Celeita, D.; Anders, G. Deep and machine learning models to forecast photovoltaic power generation. Energies 2023, 16, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohani, A.; Sayyaadi, H.; Cornaro, C.; Shahverdian, M.H.; Pierro, M.; Moser, D.; Karimi, N.; Doranehgard, M.H.; Li, L.K.B. Using machine learning in photovoltaics to create smarter and cleaner energy generation systems: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Radzi, P.N.L.; Akhter, M.N.; Mekhilef, S.; Mohamed Shah, N. Review on the application of photovoltaic forecasting using machine learning for very short-to long-term forecasting. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leo, P.; Ciocia, A.; Malgaroli, G.; Spertino, F. Advancements and Challenges in Photovoltaic Power Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2025, 18, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, P.T. The heterogeneity statistic I 2 can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Source | Total Citation (TC) | Total Citation/Total Paper (TC/TP) | h_Index | g_Index | m_Index | Journal Impact Factor | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IEEE Access | 305 | 27.73 | 9 | 11 | 1.500 | 3.6 | USA |

| 2 | Applied Energy | 150 | 21.43 | 6 | 7 | 1.200 | 11.0 | United Kingdom |

| 3 | Energies | 269 | 29.89 | 6 | 9 | 0.857 | 3.2 | Switzerland |

| 4 | Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | 516 | 129 | 4 | 4 | 0.400 | 16.3 | United Kingdom |

| 5 | IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics | 367 | 91.75 | 3 | 4 | 0.500 | 9.9 | USA |

| 6 | Sensors | 250 | 83.33 | 3 | 3 | 0.429 | 3.5 | Switzerland |

| 7 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | 44 | 14.67 | 3 | 3 | 0.750 | 3.3 | Switzerland |

| 8 | Electric Power Systems Research | 19 | 9.5 | 2 | 2 | 0.500 | 9.9 | Netherlands |

| 9 | Energy and AI | 101 | 36.67 | 2 | 3 | 0.400 | 9.6 | Netherlands |

| 10 | Energy Reports | 51 | 12.75 | 2 | 4 | 0.500 | 5.1 | United Kingdom |

| Rank | Authors | Article Title | Source Title | Total Citation (TC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [21] | GA based frequency controller for solar thermal–diesel–wind hybrid energy generation/energy storage system | International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems | 490 |

| 2 | [22] | Hybrid renewable microgrid optimization techniques: A review | Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | 273 |

| 3 | [23] | Federated Reinforcement Learning for Energy Management of Multiple Smart Homes With Distributed Energy Resources | IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics | 186 |

| 4 | [24] | Cooperative Management for PV/ESS-Enabled Electric Vehicle Charging Stations: A Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach | IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics | 174 |

| 5 | [25] | Day-Ahead Solar Irradiance Forecasting for Microgrids Using a Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Network: A Deep Learning Approach | Energies | 172 |

| 6 | [26] | A review on performance of artificial intelligence and conventional method in mitigating PV grid-tied related power quality events | Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | 133 |

| 7 | [27] | Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Voltage Control With Coordinated Active and Reactive Power Optimization | IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid | 130 |

| 8 | [28] | Energy Management of Smart Home with Home Appliances, Energy Storage System and Electric Vehicle: A Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach | Sensors | 116 |

| 9 | [29] | Power Enhancement With Grid Stabilization of Renewable Energy-Based Generation System Using UPQC-FLC-EVA Technique | IEEE Access | 111 |

| 10 | [30] | Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy Management of Smart Home with Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic System, Energy Storage System, and Home Appliances | American Control Conference (ACC) | 107 |

| Feature | Photovoltaic System | BESS (Battery Storage) System | Off-Grid Configuration | On-Grid Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Function | Generating electricity from solar radiation [34,43]. | Store excess energy for later use and mitigate fluctuations [42,44]. | Supply energy autonomously without connection to the main power grid [41,43]. | Complement the grid supply, optimize costs and sell surpluses [31,45]. |

| Key Components | Photovoltaic modules (en. polySi), inverter, charge controller (MPPT) [46,47]. | Batteries (e.g., Lithium-Ion), Battery Management System (BMS), Bi-directional Converter [48,49]. | PV panels, BESS, backup generator (e.g., diesel or biogas), inverter for autonomous power without connection to the main power grid [41,42,50]. | PV panels, BESS (optional but recommended), grid-connected inverter, bi-directional meter [22,41]. |

| Dependency/Challenges | Highly dependent on weather conditions (irradiation, temperature, cloudiness) [22,31,43]. | It depends on the energy generated by the PV system or the grid for charging. Its lifespan is affected by charge/discharge cycles [40,42]. | Completely independent of the power grid. Reliability depends on system sizing and the availability of local resources [22,42]. | Grid-dependent for backup and energy sales. Vulnerable to grid outages, although the BESS can provide autonomy [43,44]. |

| Optimization Objective | Maximize energy generation through algorithms such as MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) [31,43,51]. | Optimize charge/discharge cycles to maximize service life and profitability, managing SOC and SOH [42,49]. | Ensure reliability of supply (e.g., minimize LPSP—Probability of Loss of Power Supply) and autonomy [45,50]. | Minimize energy costs (LCOE), maximize self-consumption and income from the sale of surpluses [22,31]. |

| Energy Flow | One-way: from the sun to the System [45]. It is managed by EMS for efficient use [41]. | Bidirectional: charging from PV/grid and discharging to loads/grid, managed by BMS and EMS [40,46,52]. | The flow is managed internally to meet local demand. Excess flow is stored or discarded [41,42]. | Bidirectional with the power grid: buying and selling energy [31,41]. |

| R | Objective | Methodology | Results | Context | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [42] | Predicting the State of Charge (SOC) of lead-acid batteries using neural networks for a solar drying system (Solar Smart Dome 4.0). | - Models: Transformer Neural Network, LSTM, GRU. Input data: Battery voltage, current and temperature. | - GRU was the most accurate model: MAE 0.642%, RMSE 0.885%, R2 99.88%. The Transformer model was faster to train but less accurate than LSTM and GRU. | Agricultural drying system in rural areas, powered by photovoltaic solar energy with battery storage. | It demonstrates the generalization capabilities of neural networks to predict SOC across different battery types and with limited data, which is vital for storage management. |

| [31] | Design and optimize a grid-connected residential microgrid with PV, wind turbines, and BESS, using ML to predict total renewable generation. | - Software: HOMER Pro version 3.16.2 for techno-economic optimization. ML model: Random Forest Regressor for forecasting. Input data: Irradiance, temperature, wind speed. | - Random Forest had high accuracy: R2 of 0.99996, MAE of 0.0122, RMSE of 0.0287 for total renewable power prediction. The optimal configuration (PV + WT + BESS + Grid) achieved a renewable fraction of 68.3% and a COE of $0.035/kWh. | Residential microgrid in Pabna, Bangladesh, to mitigate the impact of grid outages and reduce energy costs and emissions. | Integrates ML prediction directly into the design and optimization of a hybrid microgrid, validating its stability and economic viability in a real-world context with grid problems. |

| [66] | Develop a two-stage energy management framework for a hydrogen-power distribution network with PV-enabled hydrogen fueling stations (HFS). | - Stage 1: MISOCP optimization for daily scheduling of HFS, PV, OLTC and capacitor banks. - Stage 2: DRL (SAC algorithm) to reschedule the reactive power of PV systems and the power/hydrogen of HFS in real time. | - The two-stage frame was effective in maintaining stable operation of the PHCIES and maximizing HFS gains. The adaptive safety module in the DRL eliminated SOH and voltage violations during training. | Power-Hydrogen Integrated Energy System (PHCIES) with stand-alone PV systems and PV-enabled Hydrogen Fueling Stations (HFS). | It proposes a hybrid approach that combines classical optimization and secure DRL for the complex management of multi-energy systems (electricity and hydrogen), ensuring safe and profitable operations. |

| [63] | Designing an AI controller for a UPQC integrated with a solar-battery system in three-phase distribution networks to improve power quality. | - AI Models: ANN trained with Soccer League algorithm (S-ANNC) for the shunt active power filter. FLC for the series active power filter. Synchronization Technique: STF-UVGM to eliminate the need for PLL. | - The S-ANNC controller outperformed GA, PSO, and GWO methods in decreasing THD, improving power factor, and mitigating voltage distortions. The system maintained constant DC link voltage during load/irradiation variations. | UPQC in three-phase distribution networks with PV and battery storage integration to mitigate power quality (PQ) problems. | It demonstrates the superiority of a hybrid AI controller (S-ANNC and FLC) for managing UPQC in systems with PV and storage, improving power quality without the need for traditional components such as PLLs. |

| Touzani [67] | Controlling distributed energy resources (DERs) through DRLs for load flexibility and energy efficiency in buildings. | - DRL Model: Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm for the integrated control of HVAC systems and electric battery storage with on-site PV generation. | - The DRL-based controller achieved cost savings of up to 39.6% compared to a rule-based baseline controller while maintaining similar thermal comfort. | Integrated control of HVAC systems and electric battery storage in the presence of on-site PV generation in commercial buildings. | Contribution: Implements and validates a DRL controller in a physical building for integrated DER management, demonstrating its effectiveness in reducing energy costs and managing load flexibility in a real-world environment. |

| Reference | Main Objective | Methodology and Models Used | Key Results and Performance Metrics | Input Data and Preprocessing | Limitations and/or Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [34] | Propose a long-term ML-based solar PV generation forecasting framework for effective operation of system operators. | - Model: ML framework based on regression analysis, comparing a standard base model with a proposed auxiliary cascade model. | - The proposed framework improves the accuracy of the Renewable Energy Forecast (REF) by incorporating observational variables along with the forecasting model. | - Input Data: GHI, DNI, ambient temperature, humidity, cloud variation, seasonal variation. | Contribution: The framework is vital for long-term forecast horizons, enabling better estimation of solar PV potential, which is crucial for planning large-scale storage systems. |

| [55] | Introduce a framework for forecasting short-term PV generation in isolated microgrids, based solely on solar irradiance data from remote weather stations. | - Hybrid Model: Two-stage Hybrid Data Linked Model (HDLM) architecture, which integrates a Layered Recurrent Neural Framework (LRNF) and a pattern identification network. Feature Engineering: Modified EMD (MEMD) and K-Means clustering. | - HDLM outperformed other models: MAE of 1.02, RMSE of 2.176, and R2 of 0.991. Computation time was reduced by 15% after feature selection. | - Input Data: Only solar irradiance data from a distant weather station. Preprocessing: MEMD for signal decomposition and feature generation. | Contribution: Demonstrates that highly accurate PV forecasting can be achieved for remote locations (microgrids) even with limited data (irradiance only), thanks to advanced feature engineering. |

| [56] | To conduct a systematic literature review on Deep Learning applications for solar PV forecasting. | - Methodology: Systematic review of 26 selected articles, analyzing DL architectures, preprocessing techniques, input features and evaluation metrics. | - LSTM was the most used algorithm (32.69%), followed by CNN (28.85%). Wavelet Transform (WT) was the most prominent data decomposition technique, and Pearson Correlation was the most used for feature selection. | - Most Common Input Features: Ambient temperature, pressure and humidity. Preprocessing Techniques: WT, VMD, K-Means, GANs. | Contribution: Provides a structured overview of the state of the art in solar forecasting with DL, identifying the most effective models and techniques and the persistent challenges such as model generalization and interpretability. |

| [61] | Investigate the benefits of combining an ML approach with PV energy forecasts generated by meteorological models. | - ML Models: Linear Model, LSTM, XGBoost, LightGBM. - Combined Approach: Uses forecasts from a numerical weather model (NWP) as input for the ML models. | - Linear models were the most effective, with an RMSE improvement of at least 3.7% in PV production forecasting compared to the reference methods. | - Input Data: PV production forecasts from reference models (BaselineP and BaselineD) and past production observations. | Contribution: Demonstrates that simple ML models, such as linear ones, can significantly refine and improve the forecasts of established physical models, even with limited data, which is useful for newly installed plants. |

| Kim [65] | Develop Transformer network variants (PVTransNet) for next-day hourly PV power forecasting. | - Models: Three Transformer variants (PVTransNet-E, PVTransNet-ED, PVTransNet-EDR) and LSTM base models. - PVTransNet-EDR combines LSTMs to improve input weather forecasts. | - PVTransNet-EDR outperformed all models: It reduced the MAE by up to 56.9% and improved the R2 by 0.7062 compared to a simple LSTM model. | - Input Data: Historical PV power generation, meteorological observations, weather forecasts, and solar geometry data. | Contribution: Introduces a specialized Transformer architecture that integrates a pre-trained LSTM model to improve the accuracy of PV generation forecasting, demonstrating the superiority of attention mechanisms for this task. |

| Khadeeja [54] | Predicting daily solar power generation using ML, with a focus on application to a newly installed solar plant with limited data. | - ML Models: Linear Regression, ARIMA, ANN, SVM, Random Forest, Decision Tree, GBM, LGBM, XGBM. | - ANN was the most effective model, achieving an RMSE of 274.84 kWh, MAE of 245.93 kWh and a MAPE of 5.26%. | - Input Data: Irradiance, humidity, minimum and maximum temperatures, and surface pressure. | Key Contribution: Demonstrates the feasibility of achieving accurate forecasts with a limited data set from a newly installed solar plant, a practical and underexplored scenario in the literature. |

| Reference | Objective | Methodology | Results | Context | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | Determine the optimal sizing of deep-cycle batteries and manage their charging in real time in Solar-EV systems. | - Simulation Model: MATLAB/Simulink R2021a (version 9.10) with RTTM for real-time analysis. ML Models: Gradient Boosting, Random Forest Regression, ANN, SVM, Decision Tree, MLP, etc., to predict the DoD. | - Random Forest was the best DoD predictor, with an accuracy of 99.998%. Integrating MPPT and a PLL controller improved system efficiency and grid synchronization. | Charging electric vehicles (EVs) using a hybrid solar-grid system based on UDDS driving cycles. | Contribution: Provides an integrated framework for intelligent battery sizing and management for EVs, validated with a real-time hardware platform (RTTM) and optimized through a comprehensive comparison of ML models. |

| [49] | Provide a comprehensive analysis of intelligent control strategies and BMS methodologies in EV applications. | - Methodology: Literature review on optimization algorithms (GA, PSO) and ML (FFNN, SVM, RF, FL) for estimating the battery state (SOC, SOH). | - ML and DL algorithms have shown superior results in battery health estimation, although they require large, high-quality data sets and fast processors. | Battery management system (BMS) in electric vehicles (EVs), covering state estimation, cell balancing, fault diagnosis, and thermal control. | Contribution: Provides a comprehensive and critical review that classifies and evaluates various AI techniques for BMS, identifying their advantages, disadvantages, and implementation challenges in the context of EVs. |

| [72] | Investigate the role of AI in developing smart EV charging infrastructure in Malaysia. | - Methodology: A mathematical model was developed for an AI-based smart charging system. Technologies such as ML and predictive analytics for charging management were reviewed. | - The implemented AI-based smart charging system achieved 30% energy savings and 20.38% cost reduction compared to traditional methods. | Electric vehicle charging infrastructure (EVCS) in Malaysia, with a focus on smart charging, demand management, and renewable energy integration. | Contribution: Demonstrates, using a mathematical model and cost analysis, the quantitative benefits of AI for optimizing EV charging, improving efficiency, and supporting grid stability in a specific national context. |

| [48] | Develop an AI-based energy management controller for a DC microgrid-based EV charging station, with V2G and G2V capabilities. | - AI Model: ANN with an adaptive interaction algorithm for energy management. MPPT Control: ANFIS to maximize the power of the PV system. | - The ANN-based PMC controller reduced the DC bus voltage overshoot from 9.6% to 0%, the stabilization time from 1.18 s to 0.52 s, and the rise time from 0.27 s to 0.25 s, compared to a conventional controller. | Electric vehicle charging station (EVCS) based on a DC microgrid with a PV system, storage battery, and grid connection. It operates in V2G and G2V modes. | Contribution: Proposes and validates an adaptive ANN controller for bidirectional power management in an EVCS, significantly improving DC bus stability and power management efficiency. |

| [73] | Developing an off-grid PV-based hydrogen and oxygen co-production system using ML and multi-objective optimization. | - ML models: Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and Weighted Average Surrogate (WAS) to establish a surrogate model between the design variables and the optimization objectives. - Optimization algorithms: POGCEA and RVGEA. | - The optimized system increased hydrogen production by 16.80% and PEM electrolysis efficiency by 12.08% compared to the initial solution. | Off-grid hydrogen and oxygen co-production system consisting of PV-BESS-PEM for continuous and stable hydrogen production around the clock. | Contribution: Proposes a methodological framework that integrates ML models and multi-objective optimization algorithms for the design and operation of green hydrogen production systems, maximizing both production and efficiency. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodriguez-Aburto, C.; Montaño-Pisfil, J.; Santos-Mejía, C.; Morcillo-Valdivia, P.; Solís-Farfán, R.; Curay-Tribeño, J.; Morales-Vargas, A.; Vara-Sanchez, J.; Gutierrez-Tirado, R.; Vigo-Roldán, A.; et al. Machine Learning for Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Integrated with Energy Storage Systems: A Scientometric Analysis, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 6291. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236291

Rodriguez-Aburto C, Montaño-Pisfil J, Santos-Mejía C, Morcillo-Valdivia P, Solís-Farfán R, Curay-Tribeño J, Morales-Vargas A, Vara-Sanchez J, Gutierrez-Tirado R, Vigo-Roldán A, et al. Machine Learning for Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Integrated with Energy Storage Systems: A Scientometric Analysis, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6291. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236291

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodriguez-Aburto, César, Jorge Montaño-Pisfil, César Santos-Mejía, Pablo Morcillo-Valdivia, Roberto Solís-Farfán, José Curay-Tribeño, Alberto Morales-Vargas, Jesús Vara-Sanchez, Ricardo Gutierrez-Tirado, Abner Vigo-Roldán, and et al. 2025. "Machine Learning for Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Integrated with Energy Storage Systems: A Scientometric Analysis, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis" Energies 18, no. 23: 6291. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236291

APA StyleRodriguez-Aburto, C., Montaño-Pisfil, J., Santos-Mejía, C., Morcillo-Valdivia, P., Solís-Farfán, R., Curay-Tribeño, J., Morales-Vargas, A., Vara-Sanchez, J., Gutierrez-Tirado, R., Vigo-Roldán, A., Vega-Ramos, J., Casazola-Cruz, O., Pilco-Nuñez, A., & Arroyo-Paz, A. (2025). Machine Learning for Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Integrated with Energy Storage Systems: A Scientometric Analysis, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. Energies, 18(23), 6291. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236291