A Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Electricity Fraud Detection: Integrating Isolation Forest and XGBoost for Real-World Utility Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Comprehensive feature engineering: Behavioral, temporal, and contextual descriptors (rolling statistics, change indicators, seasonal ratios, and peer-normalized metrics) tailored to tabular consumption data.

- Hybrid learning strategy: Integration of an unsupervised anomaly indicator with a high-performance supervised classifier to capture complementary signals of irregularity.

- Imbalance handling: Application of hybrid resampling/weighting and boundary-cleaning approaches suitable for rare-event detection.

- Operational evaluation: Beyond AUC/F1, we report customer-level precision/recall and perform threshold tuning aligned with inspection capacity.

- Interpretability: Importance analyses to expose which consumption dynamics drive alerts, supporting transparent and auditable decisions.

2. Related Work and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Data-Driven Electricity Theft Detection

2.2. Hybrid and Ensemble Methods

2.3. Mathematical Theoretical Basis

2.3.1. XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting)

- is the loss function (in this case, binary:logistic), which measures the discrepancy between the true value and the predicted value .

- represents the prediction for the i-th instance at iteration .

- denotes the new decision tree added at iteration t.

- is the regularization term that penalizes the model’s complexity.

- N represents the total number of samples in the dataset. Note that in the summation context of the approximation below, the index n is often used interchangeably to denote the number of instances.

- T is the number of leaves in the tree.

- represents the weight (or score) of leaf j.

- , (L2), and (L1) are regularization parameters that penalize trees with excessive depth or large leaf weights, thereby controlling overfitting and improving model generalization.

2.3.2. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection: Isolation Forest

2.3.3. Class Balancing with SMOTETomek

- SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique): Instead of simply duplicating existing instances, SMOTE generates new synthetic samples of the minority class. For a given minority instance , one of its k nearest neighbors is randomly selected, and a new synthetic point is created along the line segment connecting and :where is a random number uniformly distributed in the interval . This process increases the diversity and coverage of the minority class without replicating existing information, leading to a smoother feature space.

- Tomek Links: After applying SMOTE, Tomek Links are used to remove noise and ambiguous samples. A Tomek Link is a pair of instances from opposite classes that are each other’s nearest neighbors. The existence of such a pair typically indicates either noise or an overlapping region near the decision boundary. The instance belonging to the majority class is removed, resulting in a cleaner separation between classes and a more well-defined decision surface.

2.3.4. Evaluation Metrics

- Precision: Measures the proportion of positive predictions that were correct. This metric is particularly important when the cost of a False Positive is high.

- Recall (Sensitivity): Measures the proportion of actual positives correctly identified by the model. Recall is the most critical metric when the cost of a False Negative is high, as in fraud detection.

- F1-Score: Represents the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a balanced evaluation of the model’s performance across both metrics.

- AUC-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve): Measures the model’s ability to discriminate between the two classes. The ROC curve plots the True Positive Rate (Recall) against the False Positive Rate () across multiple decision thresholds. An AUC value of 1.0 indicates a perfect classifier, while a value of 0.5 corresponds to random performance.

2.4. Challenges and Research Gaps

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Framework

- Raw Data: The foundation of this project consists of annual datasets provided by a real power distribution utility in Peru (2019–2022), containing detailed electricity consumption records obtained from the official website of Osinergmin [15]. The available columns include: customer number, geographic location code (Ubigeo), tariff, category, off-peak active consumption, peak-hour active consumption, distribution substation, feeder, secondary substation, geographic coordinates, month, and year.An in-depth analysis revealed that the core attributes for modeling are the active energy consumption during peak hours and off-peak periods, as they directly capture customer consumption behavior. The customer number column uniquely identifies each consumer, while Ubigeo is used during the data-filtering stage to segment the dataset by region.Network topology attributes (distribution substation, feeder, and secondary substation) and geographic coordinates were excluded from the final model, reflecting a deliberate focus on consumption behavior rather than spatial or infrastructural characteristics.

- Data Consolidation: This stage focuses on transforming multiple annual files into a single, structured, and labeled dataset suitable for supervised learning. It comprises three main tasks: (a) Filtered by Geographic Location Code (Ubigeo) to retain only the consumers relevant to the study region; (b) concatenating the four annual datasets (2019–2022) into a unified database, while adding a new column (YEAR) to preserve temporal reference; and (c) correcting and standardizing columns whose data types or names were inconsistent across years (e.g., a field stored as a string in 2019 and as a float in 2020). After consolidation, the filtered list of customers is cross-referenced with an external registry of confirmed fraud cases. This comprehensive preprocessing step ensures data integrity and provides a solid foundation for robust and generalizable model training.

- Target Variable Definition and Data Splitting: This stage combines the creation of the target variable with the design of new, informative features derived from the raw consumption data. (a) Real database of confirmed fraud cases: The process begins by cross-referencing the main dataset with an external registry of confirmed fraudulent customers. This step ensures that the supervised learning task is grounded in verified cases rather than synthetic or inferred labels. It is acknowledged that the “Non-Fraud” class (0) likely contains undetected fraud cases, a scenario known as Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning. However, we rely on the utility’s verified ground truth for supervised training, assuming that the “Fraud” class (1) represents high-confidence positive labels. (b) Creation of the “fraud” label by cross-referencing customer lists: Each customer is assigned a binary label in the target variable (FRAUD), where “1” corresponds to a confirmed fraudulent consumer and “0” to a regular one. The resulting dataset is then stratified and divided into training and testing subsets while maintaining the class distribution, avoiding bias during model evaluation. In parallel, a feature engineering process is applied to enrich the dataset with behavioral indicators derived from consumption history. Moving averages over 3-, 6-, and 12-month windows, standard deviations, and cumulative consumption metrics are computed to capture temporal patterns and anomalies. These derived features transform raw measurements into higher-level representations of consumer behavior, enabling the learning algorithm to detect irregularities more effectively.

- Predictive Model Training: After the feature engineering process, the dataset is divided into two subsets: training and testing. During this stage, the machine learning algorithm learns to identify complex relationships between the engineered features (consumption patterns) and the target variable (FRAUD), optimizing its internal parameters to minimize prediction errors.

- (a)

- Application of the SMOTETomek technique: To mitigate the severe class imbalance—where fraudulent cases represent only a small fraction of all records—the hybrid SMOTETomek method is applied to the training data. This approach combines oversampling of the minority class (fraud) with undersampling of ambiguous boundary samples, producing a more representative and cleaner training set.

- (b)

- Training of the XGBoost classifier with balanced data: The rebalanced dataset is then used to train an XGBoost classifier, chosen for its high predictive performance, robustness, and ability to efficiently handle large tabular datasets. Through iterative boosting, the model learns non-linear decision boundaries that capture subtle behavioral differences between normal and fraudulent consumers, resulting in a strong and generalizable predictive model.

- Performance Evaluation and Analysis: Once the model has been trained, its real-world effectiveness is assessed using a separate testing set that contains data the model has never seen before. This stage is crucial to evaluate the model’s generalization capability—that is, its ability to perform reliably on new and unseen samples. The evaluation process is structured into three complementary analyses:

- (a)

- Testing on unseen data: The trained model generates predictions for each customer in the testing dataset, which are then compared with the true fraud labels. This direct comparison quantifies how well the model can distinguish between fraudulent and legitimate consumers under realistic operating conditions.

- (b)

- Threshold adjustment (0.6)–precision/recall trade-off: A decision threshold of 0.6 is applied to balance the trade-off between detection sensitivity and false-positive rate. Key evaluation metrics—including accuracy, precision (the proportion of correctly identified fraud cases among all predicted frauds), and recall (the proportion of actual fraud cases successfully detected)—are computed to assess the model’s overall effectiveness and practical viability in real deployment scenarios.

- (c)

- Feature importance analysis: Finally, a feature importance study is conducted to determine which variables contribute most significantly to fraud detection. This interpretability step not only validates the model’s learning process but also provides valuable insights into the behavioral and statistical indicators most associated with non-technical losses in electricity consumption.

3.2. Data Description and Preparation

3.3. Feature Engineering

- General Consumption Statistics per Customer:

- -

- CLIENT_AVG_CONS_FP: Average off-peak (FP) consumption per customer.

- -

- CLIENT_MEDIAN_CONS_FP: Median FP consumption per customer.

- -

- CLIENT_STD_CONS_FP: Standard deviation of FP consumption, indicating variability.

- -

- CLIENT_MIN_CONS_FP and CLIENT_MAX_CONS_FP: Minimum and maximum FP consumption per customer.

- -

- CLIENT_SUM_CONS_FP: Total FP consumption per customer.

- -

- CLIENT_COUNT_MONTHS: Number of months with available consumption records.

- -

- CLIENT_CV_CONS_FP: Coefficient of variation of FP consumption, a normalized measure of dispersion.

- Zero-Consumption Periods: CLIENT_ZERO_CONS_FP_MONTHS and CLIENT_PERCENT_ZERO_CONS_FP_MONTHS were created to quantify prolonged zero-consumption periods, which may indicate abnormal or fraudulent behavior.

- Customer Activity Duration: CLIENT_TIME_ACTIVE_TOTAL_MONTHS computes the total number of months the customer remained active in the records, based on the minimum and maximum consumption dates.

- Consumption Variations (Monthly and Yearly):

- -

- CLIENT_MONTHLY_CONS_FP_CHANGE_PCT: Monthly percentage variation in FP consumption relative to the previous month.

- -

- CLIENT_YOY_MONTHLY_CONS_FP_CHANGE_PCT: Year-over-year percentage variation in FP consumption for the same month. This feature is essential for isolating irregular behavior by compensating for natural annual consumption cycles. By comparing, for example, January 2021 with January 2020, the feature effectively removes expected seasonal effects—such as increased air-conditioning usage during warmer months—thereby enabling the model to detect deviations that genuinely depart from the customer’s normal seasonal pattern.

- Statistics of Monthly Consumption Variation per Customer: Features such as CLIENT_AVG_ABS_MONTHLY_CHANGE_PCT, CLIENT_STD_MONTHLY_CHANGE_PCT, CLIENT_MAX_MONTHLY_INCREASE_PCT, and CLIENT_MIN_MONTHLY_DECREASE_PCT quantify the customer’s consumption stability and fluctuation intensity.

- Category-Year Consumption and Variation Statistics: The average and median consumption, as well as the average absolute monthly variation, were calculated for each CATEGORIA and ANO, allowing comparisons between a customer’s behavior and that of peers within the same category and year.

- Category-Year Comparison Features:

- -

- CLIENT_CONS_FP_RATIO_TO_CAT_YEAR_AVG: Ratio of customer consumption to the category/year average.

- -

- CLIENT_CONS_FP_DIFF_FROM_CAT_YEAR_AVG: Difference between customer consumption and the category/year average.

- -

- CLIENT_CONS_FP_RATIO_TO_CAT_YEAR_MEDIAN: Ratio of customer consumption to the category/year median.

- -

- CLIENT_MONTHLY_CHANGE_ABS_PCT_DIFF_FROM_CAT: Difference between the customer’s absolute monthly variation and the category/year average.

- Rolling-Window Features:

- -

- CLIENT_ROLLING_3M_AVG_CONS_FP: 3-month rolling average of FP consumption.

- -

- CLIENT_ROLLING_6M_AVG_CONS_FP: 6-month rolling average of FP consumption.

- -

- CLIENT_ROLLING_12M_SUM_CONS_FP: 12-month rolling sum of FP consumption, useful for identifying annual trends.

- FP/HP Consumption Ratio: RAZAO_FP_HP represents the ratio between off-peak (FP) and peak-hour (HP) consumption. Abnormally high or low values may indicate meter tampering or measurement anomalies.

- Consecutive Low-Consumption Periods: MAX_CONSEC_LOW_10_CONS_FP and MAX_CONSEC_LOW_50_CONS_FP represent the maximum number of consecutive months in which the customer’s consumption was below 10% and 50% of their historical average, respectively—strong indicators of inconsistent or suspicious consumption.

- Minimum Non-Zero Consumption and Anomaly Flags:

- -

- CLIENT_MIN_NON_ZERO_CONS_FP: Minimum non-zero FP consumption recorded for the customer.

- -

- FLAG_CNS_FP_BELOW_HISTORIC_MIN_NON_ZERO: Flag indicating whether the current consumption is below the historical non-zero minimum.

- -

- FLAG_CNS_FP_NEAR_ZERO_AND_UNUSUAL: Flag indicating whether the consumption is near zero and abnormally low compared to the customer’s historical average.

- Isolation Forest Anomaly Score: An Isolation Forest model was applied to generate an anomaly score (ANOMALY_SCORE_ISO). This unsupervised algorithm is effective for outlier detection in datasets with few anomalies, such as fraud detection. The features used as input were CNS_ACT_FP, CLIENT_MONTHLY_CONS_FP_CHANGE_PCT, and CLIENT_CONS_FP_RATIO_TO_CAT_YEAR_AVG. The parameter contamination=’auto’ allows the algorithm to estimate the proportion of outliers, while n_estimators=100 ensures robust performance. Crucially, this approach acts as a stacking mechanism: the Isolation Forest model acts as an unsupervised feature extractor, outputting a score based on the average path length required to isolate an observation. This score is then fed as a high-level input feature into the supervised XGBoost model, allowing the final classifier to benefit from global anomaly patterns captured by the Isolation Forest.

- One-Hot Encoding for TARIFA and Conversion of CATEGORIA: The categorical variable TARIFA was transformed using one-hot encoding, producing binary columns such as TARIFA_COMERCIAL (Commercial Tariff) and TARIFA_RESIDENCIAL (Residential Tariff), enabling the model to interpret nominal information effectively. These categories capture the main customer segments, allowing the model to differentiate between residential usage patterns and commercial load profiles, which typically exhibit different fraud signatures.

- Final Cleaning of NaN and Infinite Values: Prior to modeling, all remaining numeric columns containing NaN or infinite values (e.g., from divisions by zero) were replaced with zeros. Columns such as ANO, MES, mes_ano, and one-hot encoded tariff columns were excluded from this step, as their values were already consistent.

3.4. Target Variable Definition and Feature Selection

3.5. Train/Test Split and Class Imbalance Treatment

- SMOTETomek: The SMOTETomek method from the imblearn.combine library was adopted as the primary resampling strategy. This hybrid approach combines oversampling of the minority class through SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) with noise reduction using Tomek Links. SMOTE synthetically generates new samples for the minority class by interpolating between existing ones, whereas Tomek Links remove pairs of samples (one from each class) that are too close to each other, thereby refining the decision boundary.

- -

- The oversampling ratio was defined as smote_target_sampling_strategy = 0.1, meaning that the minority class was expanded to reach 10% of the majority class size.

- -

- The k_neighbors parameter in SMOTE was dynamically set to minority_count_train - 1 when the minority class contained very few samples, preventing errors during neighbor generation.

- -

- The framework implements a robust fallback mechanism to ensure pipeline stability:

- Check Minority Class Count: Before applying resampling, the system checks the number of available minority class samples.

- Validation: If the count is less than 6 samples (the minimum required for default k-nearest neighbors in SMOTE), the SMOTETomek step is skipped.

- Fallback Activation: In such cases, the pipeline defaults to calculating and applying the scale_pos_weight parameter in XGBoost, which balances the loss function weights without synthesizing new data.

- scale_pos_weight (Fallback): When SMOTETomek failed or was disabled, the scale_pos_weight parameter in XGBoost was computed and applied. This parameter penalizes misclassification of minority-class samples during training, effectively compensating for class imbalance by assigning higher importance to positive (fraudulent) instances. Its value was calculated as majority_class_count/minority_class_count.

3.6. Model Architecture

- learning_rate = 0.05: Controls the step size at each boosting iteration, helping to prevent overfitting. Smaller values typically require more estimators but can lead to a more stable and generalizable model.

- max_depth = 5: Sets the maximum depth of each decision tree, controlling model complexity and preventing overfitting.

- min_child_weight = 3: Specifies the minimum sum of instance weights (Hessians) required in a child node. Higher values make the algorithm more conservative, reducing the likelihood of fitting noise in the training data.

- subsample = 0.7: Defines the fraction of training samples used to grow each tree, which helps reduce variance and overfitting.

- colsample_bytree = 0.7: Specifies the fraction of features (columns) to be randomly sampled for each tree, further reducing model variance.

- gamma = 0.2: Minimum loss reduction required to make an additional partition in a leaf node. Larger values make the algorithm more conservative by discouraging unnecessary splits.

- lambda = 1 (L2 regularization) and alpha = 0.1 (L1 regularization): Regularization terms used to control overfitting and improve generalization.

- random_state = 42: Ensures reproducibility of results.

- objective = ‘binary:logistic’: Specifies the binary classification objective for predicting the probability of fraud.

- n_estimators = 140: Number of boosting trees to be built in the ensemble.

3.7. Evaluation Metrics and Operational Criteria

- Default Threshold (0.5): Initially, the model was evaluated using the standard decision threshold of 0.5. The following metrics were calculated:

- -

- classification_report: Provides a comprehensive summary of Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Support for both classes (Non-Fraud and Fraud).

- -

- Recall (Fraud): The proportion of actual fraud cases correctly identified by the model. In fraud detection, recall is often prioritized since the main goal is to minimize the number of undetected frauds.

- -

- Precision (Fraud): The proportion of predicted fraud cases that are truly fraudulent. A high precision value indicates a lower rate of false positives.

- -

- F1-Score (Fraud): The harmonic mean between Precision and Recall, providing a balanced measure between the two.

- -

- AUC-ROC Score: The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve, a robust metric for evaluating imbalanced classification problems. It quantifies the model’s ability to distinguish between the two classes: a value of 0.5 indicates random performance, while 1.0 corresponds to a perfect classifier.

- Adjusted Decision Threshold (0.6): In fraud detection scenarios, it may be desirable to prioritize either Precision or Recall depending on the operational costs associated with false positives and false negatives. To explore this trade-off, the model was re-evaluated using an adjusted decision threshold of 0.6. Under this configuration, a prediction is classified as fraud only if the estimated probability is greater than or equal to 0.6. Increasing the threshold generally enhances Precision (reducing false positives) while slightly decreasing Recall (increasing false negatives).

- Customer-Level Detection Results (Testing Set): For a more business-oriented and granular analysis, performance metrics were also computed at the customer level, using the adjusted 0.6 threshold:

- -

- Total number of unique customers in the testing set.

- -

- Number of customers predicted as fraudulent.

- -

- Number of customers actually labeled as fraudulent.

- -

- Number of correctly identified fraudulent customers.

- -

- Customer-Level Precision: The proportion of customers predicted as fraudulent who are indeed fraudsters.

- -

- Customer-Level Recall: The proportion of actual fraudulent customers successfully detected by the model.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Baseline Performance and Threshold Optimization

4.3. Customer-Level Analysis

4.4. Lift and Cost-Benefit Analysis

4.5. Feature Importance and Interpretability

4.6. Comparative Scenarios

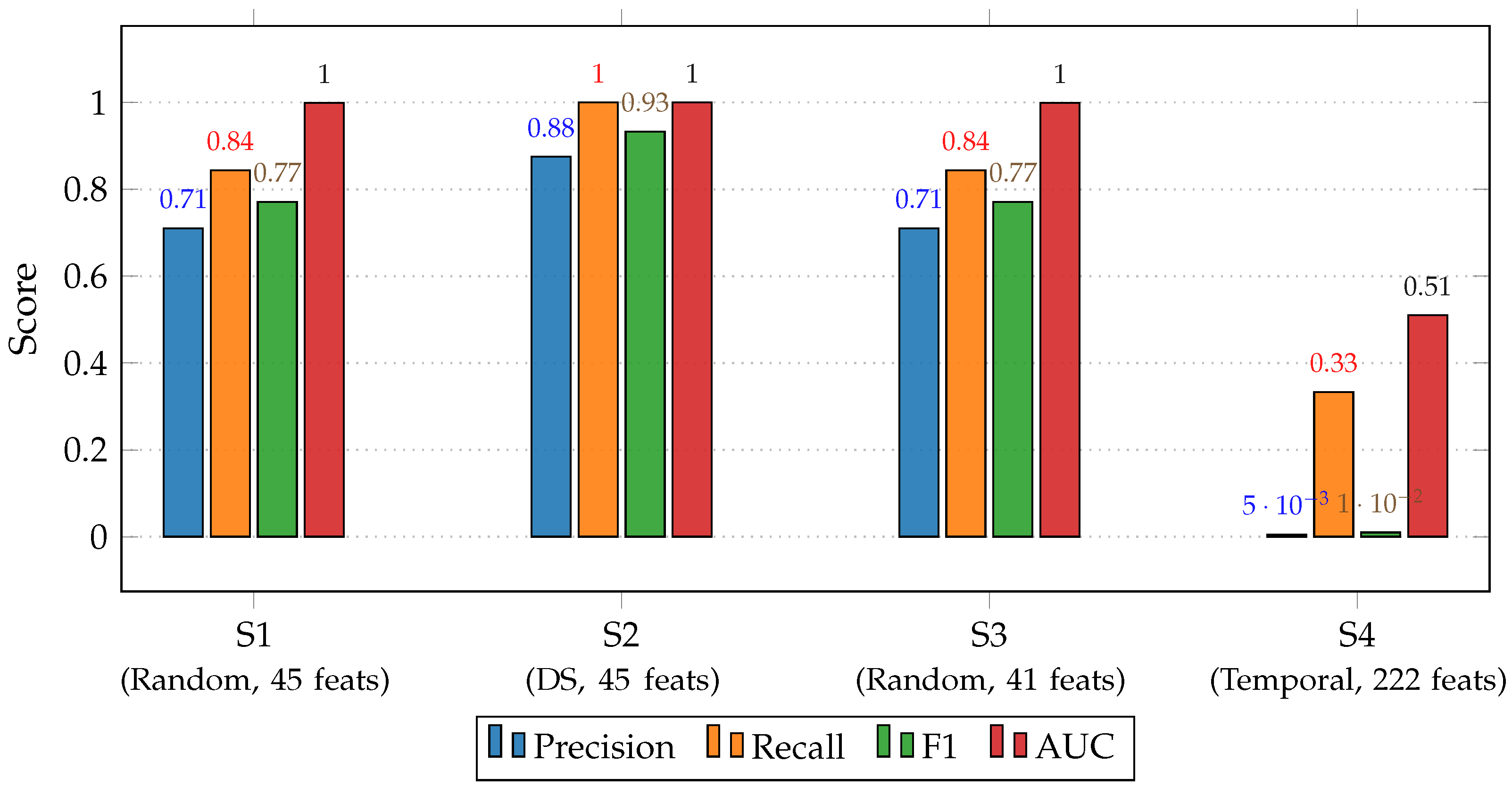

- Scenario 1: Random Split (45 features).Baseline configuration using the complete feature set. This scenario serves as the reference for comparison.

- Scenario 2: Filtered by DS. Sub-dataset restricted to a specific Distribution Substation, evaluating spatial sensitivity of the model.

- Scenario 3: Reduced Feature Set (41 features). Removal of correlated and redundant attributes to test compactness versus performance trade-offs.

- Scenario 4: Temporal Validation (TSFRESH–222 features). Extended dataset using automatically extracted time-series features to validate temporal generalization [6].

- Baselines: Random Forest & Logistic Regression. To benchmark the hybrid framework, we compared it against standard Random Forest and Logistic Regression models trained on the same data.

- Scenario 1 (Random Split with 45 Features): demonstrated a strong and stable performance across all evaluation metrics, achieving a Recall of 0.844 and an F1-score of 0.771 at a 0.6 threshold. The model successfully balanced sensitivity and precision, confirming that a comprehensive handcrafted feature set—particularly those derived from temporal variability and the Isolation Forest anomaly score—provides robust discrimination between normal and fraudulent customers. This configuration serves as the baseline reference for subsequent analyses.

- Scenario 2 (Random Split with DS Filter): produced near-perfect results, with Precision and Recall both reaching unity at the customer level. However, this exceptional performance likely stems from the increased homogeneity of the filtered subset, which simplifies the classification task. Although less generalizable to heterogeneous populations, these findings underscore the operational advantage of developing localized or substation-specific (DS-based) models for precision targeting within defined network segments.

- Scenario 3 (Random Split with 41 Features): maintained performance nearly identical to Scenario 1 while employing a reduced feature set. The removal of secondary variables, such as auxiliary anomaly indicators, slightly simplified the model without compromising predictive quality. This result highlights the efficiency of carefully engineered features over excessive dimensionality, revealing that compact yet well-designed feature spaces can preserve discriminative strength while improving interpretability and reducing computational overhead.

- Scenario 4 (Temporal Split with 222 TSFRESH Features): introduced a more realistic temporal validation, training on data from 2019–2021 and testing on 2022. Despite including a large automatically extracted feature set, performance dropped considerably (F1-score = 0.010; AUC = 0.510), and computational cost increased by approximately 60%. The poor performance of Scenario 4 stems from the high dimensionality of the automatically extracted features combined with the severe class imbalance. In this context, generic temporal descriptors extracted by TSFRESH are overshadowed by the sparse and highly localized nature of fraud patterns. Domain-informed behavioral features (e.g., abrupt drops, specific tariff changes) provide much stronger discriminatory power than abstract statistical moments, reinforcing why hybrid, domain-guided architectures remain necessary for NTL detection.

- Computational Considerations: Across all experiments, training time and memory consumption were dominated by extensive feature engineering and the SMOTETomek balancing process. While XGBoost maintained high scalability, scenarios with expanded feature spaces—particularly Scenario 4—incurred significantly higher computational demand, reinforcing the importance of model parsimony for real-world deployment.

4.7. Discussion and Limitations

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Practical Implications for Utilities

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

- Incremental Learning: Developing pipelines that can update model parameters in real-time as new consumption data arrives.

- Federated Learning: Investigating decentralized training architectures to allow different utility companies to collaborate on fraud detection without sharing sensitive customer data.

- Geospatial Enrichment: Incorporating socio-economic and detailed geospatial attributes to further refine contextual anomaly detection.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NTL | Non-Technical Losses |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| FP/HP | Off-Peak Period/Peak Period |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique |

| Tomek Links | Undersampling method that removes overlapping samples between classes |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| DS | Distribution Substation |

| AUC-ROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| TSFRESH | Time Series Feature Extraction based on Scalable Hypothesis tests |

| SMOTETomek | Hybrid resampling method combining SMOTE and Tomek Links |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ASGD | Active Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| CSGD | Cuckoo Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| AMI | Advanced Metering Infrastructure |

| IF | Isolation Forest |

References

- Ahir, R.K.; Chakraborty, B. Pattern-based and context-aware electricity theft detection in smart grid. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2022, 32, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Jaidhar, C.D. Employing Feature Extraction, Feature Selection, and Machine Learning to Classify Electricity Consumption as Normal or Electricity Theft. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S. Intelligent Feature Engineered-Machine Learning Based Electricity Theft Detection Framework for Labelled and Unlabelled Datasets. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, G.; Simão, J.G.S.; Teive, R.C.G. Identificação de Fraudes de Energia Elétrica em Consumidores Comerciais-Uma Aplicação voltada aos Medidores Inteligentes. In Proceedings of the IX Computer on the Beach, Florianópolis, Brazil, 8–10 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Darban, Z.Z.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S.; Aggarwal, C.C.; Salehi, M. Deep Learning for Time Series Anomaly Detection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdary, A.; Chehri, A.; Jakimi, A.; Saadane, R. Hyperparameter Optimization with Genetic Algorithms and XGBoost: A Step Forward in Smart Grid Fraud Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, N.; Hasnain, M.; Ammar, M. An AI explained data-driven framework for electricity theft detection with optimized and active machine learning. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouguer, D.; Sebaa, A.; Hadjout, D. Fraud Detection of the Electricity Consumption by combining Deep Learning and Statistical Methods. Electroteh. Electron. Autom. EEA 2024, 72, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiodun, T.; Olukanmi, P. Performance Evaluation of Machine Learning Models for Anomaly Detection in Energy Usage Data. In Proceedings of the 2025 33rd Southern African Universities Power Engineering Conference (SAUPEC), Pretoria, South Africa, 29–30 January 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Badr, M.M.; Ibrahem, M.I.; Kholidy, H.A.; Fouda, M.M.; Ismail, M. Review of the Data-Driven Methods for Electricity Fraud Detection in Smart Metering Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.H.; Sathyavani, B.; Mamatha Bai, B.G.; Dutta, P.; Saranya, N.N. Anomaly Detection in Conventional Meters and Electricity Consumption using Optimized Extreme Gradient Boosting. In Proceedings of the 2024 Third International Conference on Distributed Computing and Electrical Circuits and Electronics (ICDCECE), Ballari, India, 26–27 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulqadder, I.H.; Aziz, I.T.; Flaih, F.M.F. Robust Electricity Theft Detection in Smart Grids Using Machine Learning and Secure Techniques. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2025, 18, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dai, Y. A multiscale electricity theft detection model based on feature engineering. Big Data Res. 2024, 36, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawoosa, A.I.; Prashar, D.; Raman, G.R.A.; Bijalwan, A.; Haq, M.A.; Aleisa, M.; Alenizi, A. Improving Electricity Theft Detection Using Electricity Information Collection System and Customers’ Consumption Patterns. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2024, 42, 1684–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinergmin. Publicaciones—Regulación Tarifaria. Página de Publicaciones Sobre Regulación Tarifaria (Electricidad, Gas Natural, Hidrocarburos) del Organismo Supervisor de la Inversión en Energía y Minería—Perú. 2025. Available online: https://www.osinergmin.gob.pe/seccion/institucional/regulacion-tarifaria/publicaciones/regulacion-tarifaria (accessed on 1 November 2025).

| Threshold | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | AUC-ROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 0.451 | 0.938 | 0.609 | 0.999 |

| 0.51–0.53 | 0.467–0.503 | 0.936–0.906 | 0.623–0.647 | 0.999 |

| 0.54–0.56 | 0.541–0.615 | 0.894–0.878 | 0.674–0.723 | 0.999 |

| 0.57–0.59 | 0.653–0.693 | 0.874–0.846 | 0.747–0.762 | 0.999 |

| 0.60 | 0.710 | 0.844 | 0.771 | 0.999 |

| 0.65 | 0.815 | 0.710 | 0.759 | 0.999 |

| 0.70 | 0.920 | 0.550 | 0.688 | 0.999 |

| Scenario | Split/Features | Prec. | Rec. | F1 | AUC | Cust-Prec. | Cust-Rec. | Cost | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Random/ 45 features | 0.710 | 0.844 | 0.771 | 0.999 | 0.679 | 0.905 | 1.0× | Strong baseline balance |

| 2 | DS filter/ 45 features | 0.875 | 1.000 | 0.933 | 1.000 | 0.800 | 1.000 | ≈1.0× | Specialist model, near-perfect metrics |

| 3 | Random/ 41 features | 0.710 | 0.844 | 0.771 | 0.999 | 0.696 | 0.929 | ↓ vs S1 | Reduced feature set, similar performance |

| 4 | Temporal/ 222 (TSFRESH) | 0.005 | 0.333 | 0.010 | 0.510 | – | – | +60% | High cost, poor temporal generalization |

| Base 1 | Logistic Regression | 0.320 | 0.750 | 0.449 | 0.880 | – | – | Low | Linear baseline, high FP rate |

| Base 2 | Random Forest | 0.650 | 0.780 | 0.709 | 0.950 | – | – | Medium | Strong, but outperformed by XGBoost |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monteiro, T.V.P.; Castor, G.J.B.C.; Castillo Correa, C.G.; Arias, H.R.C.; Ñaupari Huatuco, D.Z.; Molina Rodriguez, Y.P. A Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Electricity Fraud Detection: Integrating Isolation Forest and XGBoost for Real-World Utility Data. Energies 2025, 18, 6249. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236249

Monteiro TVP, Castor GJBC, Castillo Correa CG, Arias HRC, Ñaupari Huatuco DZ, Molina Rodriguez YP. A Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Electricity Fraud Detection: Integrating Isolation Forest and XGBoost for Real-World Utility Data. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6249. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236249

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonteiro, Thomas Vitor P., Glaucio José Bezerra Cavalcante Castor, Carlos Gilmer Castillo Correa, Hector Raul Chavez Arias, Dionicio Zócimo Ñaupari Huatuco, and Yuri Percy Molina Rodriguez. 2025. "A Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Electricity Fraud Detection: Integrating Isolation Forest and XGBoost for Real-World Utility Data" Energies 18, no. 23: 6249. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236249

APA StyleMonteiro, T. V. P., Castor, G. J. B. C., Castillo Correa, C. G., Arias, H. R. C., Ñaupari Huatuco, D. Z., & Molina Rodriguez, Y. P. (2025). A Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Electricity Fraud Detection: Integrating Isolation Forest and XGBoost for Real-World Utility Data. Energies, 18(23), 6249. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236249