Research on Load Forecasting Based on Bayesian Optimized CNN-LSTM Neural Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Main Contributions

2. Model Architecture and Components

2.1. Convolutional Neural Network

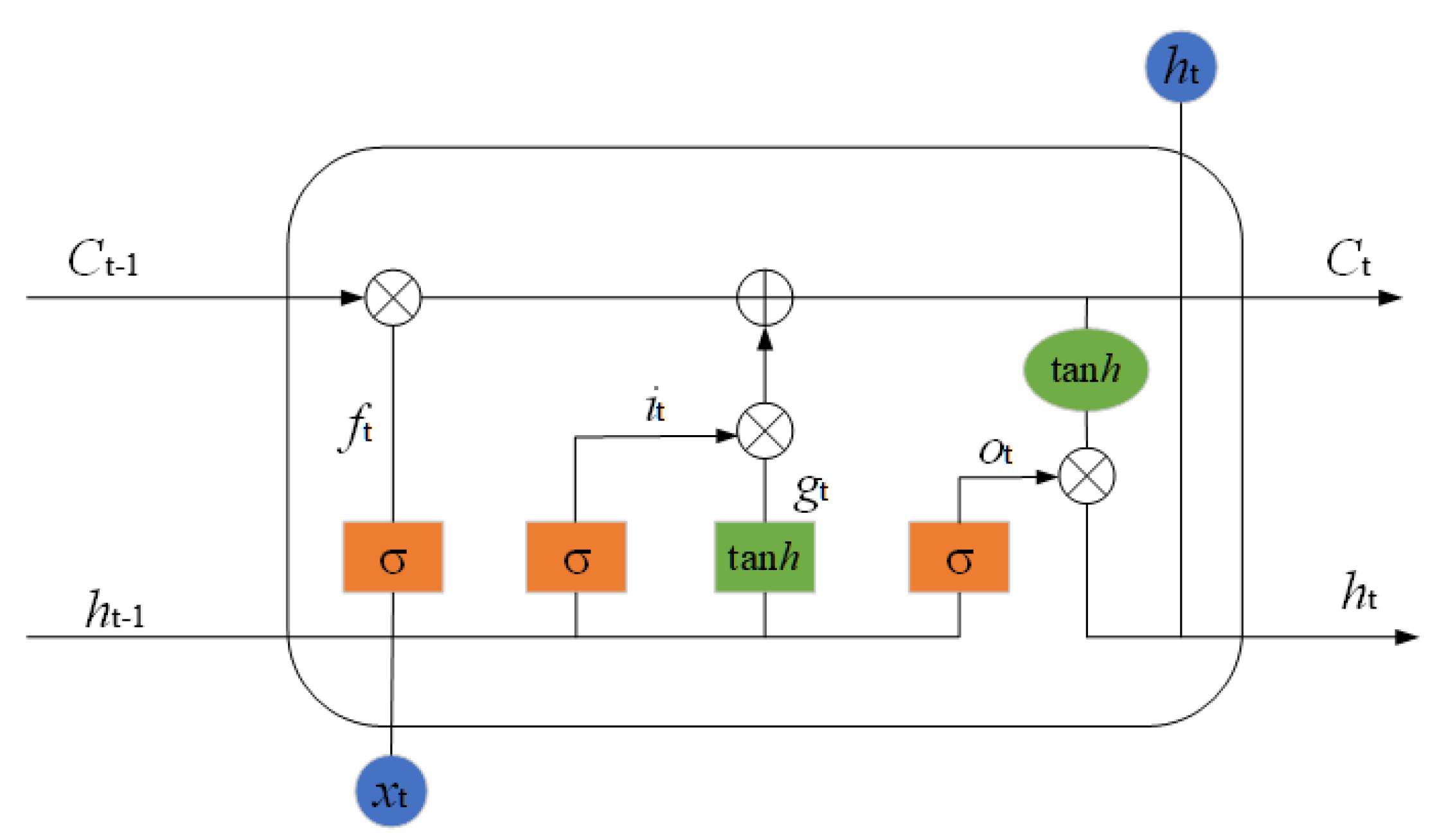

2.2. Long Short-Term Memory Network

2.3. Bayesian Optimization

- (1)

- Gaussian Process Regression

- (2)

- Acquisition Function

- (3)

- Hyperparameter Estimation Method

- (4)

- Numerical Robustness Guarantee

- (5)

- Handling of Discrete and Integer Parameters

2.4. Structure of the CNN-LSTM Short-Term Load Forecasting Model Based on Bayesian Optimization

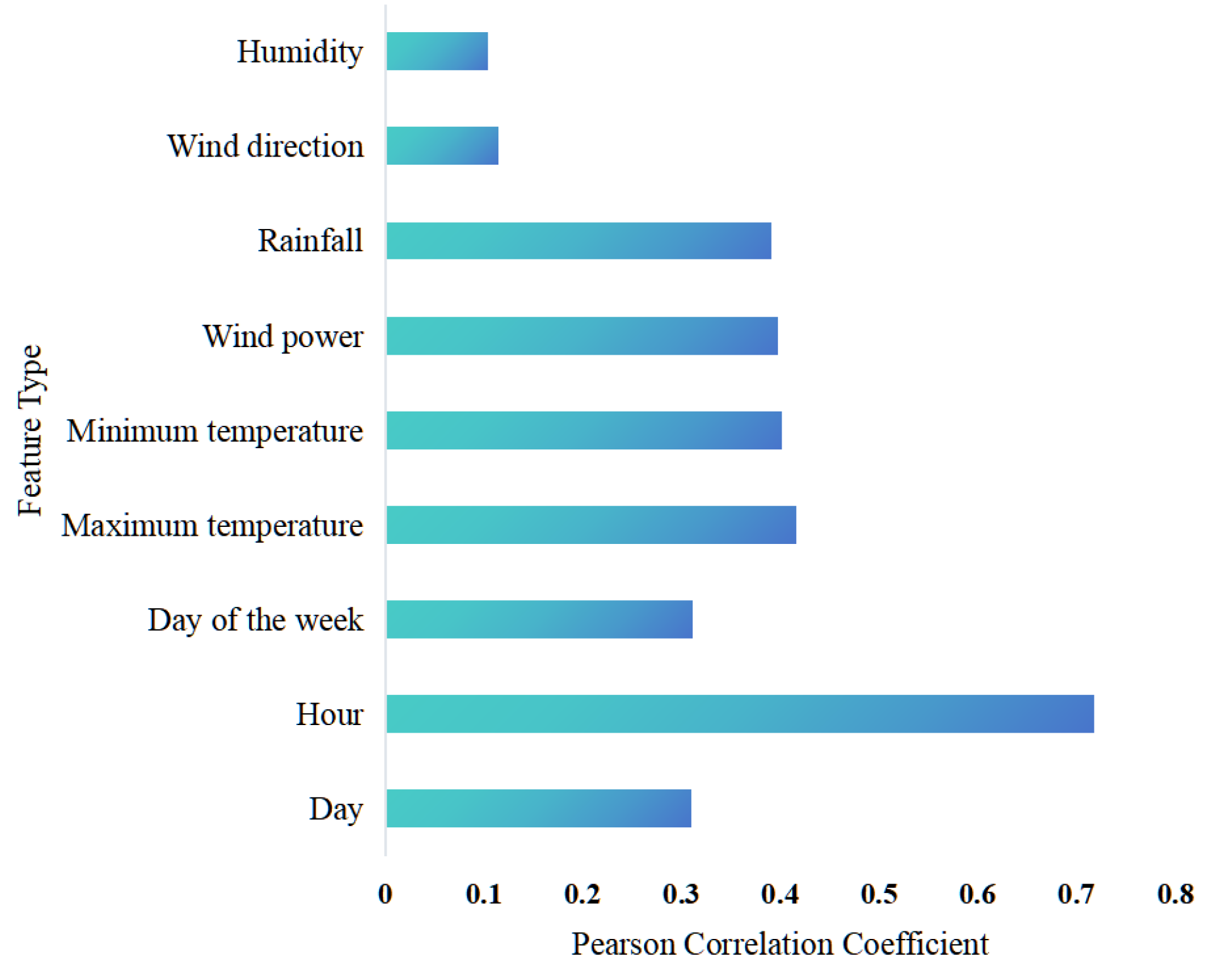

- Feature Engineering Phase. First, historical data is preprocessed, including handling missing values, treating outliers, and normalization. Preliminary input features are selected. Then, Pearson correlation coefficient is used for correlation analysis to compute the correlation between each feature and the load value. Redundant features weakly correlated with the load are eliminated, forming a new feature set for subsequent model input.

- Hyperparameter Optimization Phase. A Bayesian optimization framework is established, using the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of the prediction results as the objective function. The search space for hyperparameters is defined, including the number of CNN convolutional layers, the number and size of convolutional kernels, the number of LSTM layers, the number of LSTM units, dropout rate, learning rate, and batch size. The Gaussian process surrogate model and the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function are used to efficiently explore the parameter space and find the globally optimal hyperparameter combination.

- Receptive field theory requires the convolutional kernel to cover the fundamental period or basic fluctuation window.

- b.

- The temporal receptive field of the convolutional layer can be described by the following formula:

- c.

- Effective coverage after combining convolutional and pooling layers:

- A single convolutional layer sufficiently covers the required local structure.

- b.

- Avoiding parameter explosion and training instability caused by excessively deep convolutions.

- c.

- Rationale for evaluating dilated convolutions.

- 3.

- Predictive Model Construction Phase. The dataset is divided into training, validation, and test sets in chronological order. The model adopts a multi-layer encoder–decoder structure: the input layer receives the multi-dimensional time series data after feature selection; followed by 1–2 one-dimensional convolutional layers using the ReLU activation function to extract local features; a pooling layer to reduce feature dimensionality; a Dropout layer to prevent overfitting; then connected to 1–2 LSTM layers to capture long-term dependencies; and finally, the prediction results are output through a fully connected layer. Early stopping is used during training to prevent overfitting, and the Adam optimizer is used to update the network parameters.

- 4.

- Prediction Phase. The trained CNN-LSTM model is used for load forecasting. The test set data is fed into the model, first passing through the CNN layers to extract deep local temporal features. The feature sequences are then fed into the LSTM layers to learn the long-term dependencies of the time series. Finally, the features are integrated through the fully connected layer to output the prediction results.

- 5.

- Evaluation and Validation Phase. Multiple performance metrics are used to comprehensively evaluate the prediction results. This paper selects three metrics—Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)—to judge the accuracy of the predictions. Ablation experiments are conducted to verify the contribution of each module, including comparisons between a standalone LSTM model and the complete CNN-LSTM model, thereby validating the superiority and reliability of the proposed model.

3. Predictive Features and Evaluation Metrics

3.1. Data Preprocessing

3.2. Load Feature Screening

3.3. Parameter Settings

- He Initializer

- b.

- L2 Regularization

- c.

- Dropout (rate = 0.25)

- d.

- Gradient Clipping (Threshold = 1)

- e.

- Piecewise Learning Rate Schedule

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Ablation Experiment Results Analysis

4.3.1. Load Forecasting for Industrial Electrolytic Aluminum (Ablation Study)

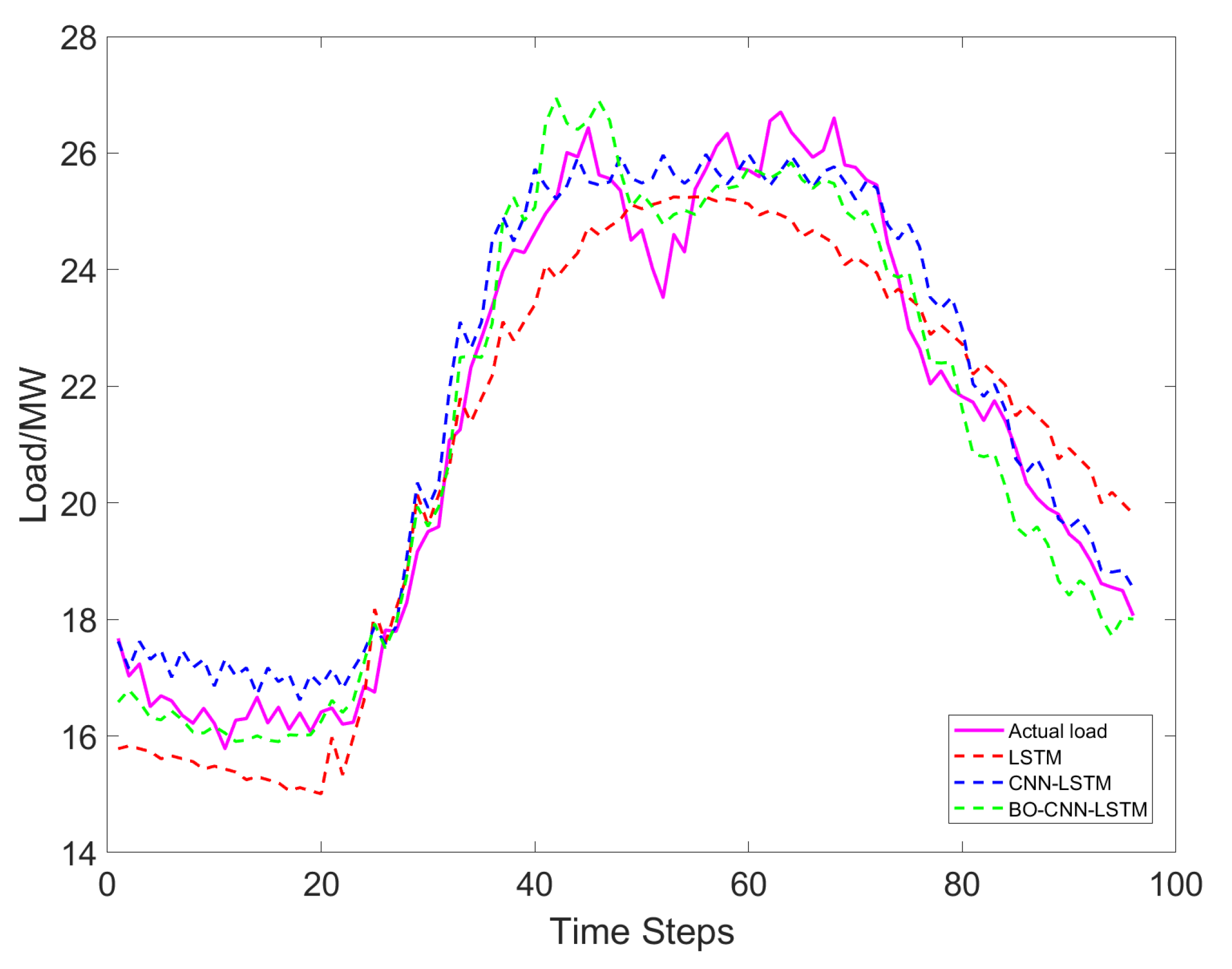

4.3.2. Load Forecasting for Agricultural Irrigation (Ablation Study)

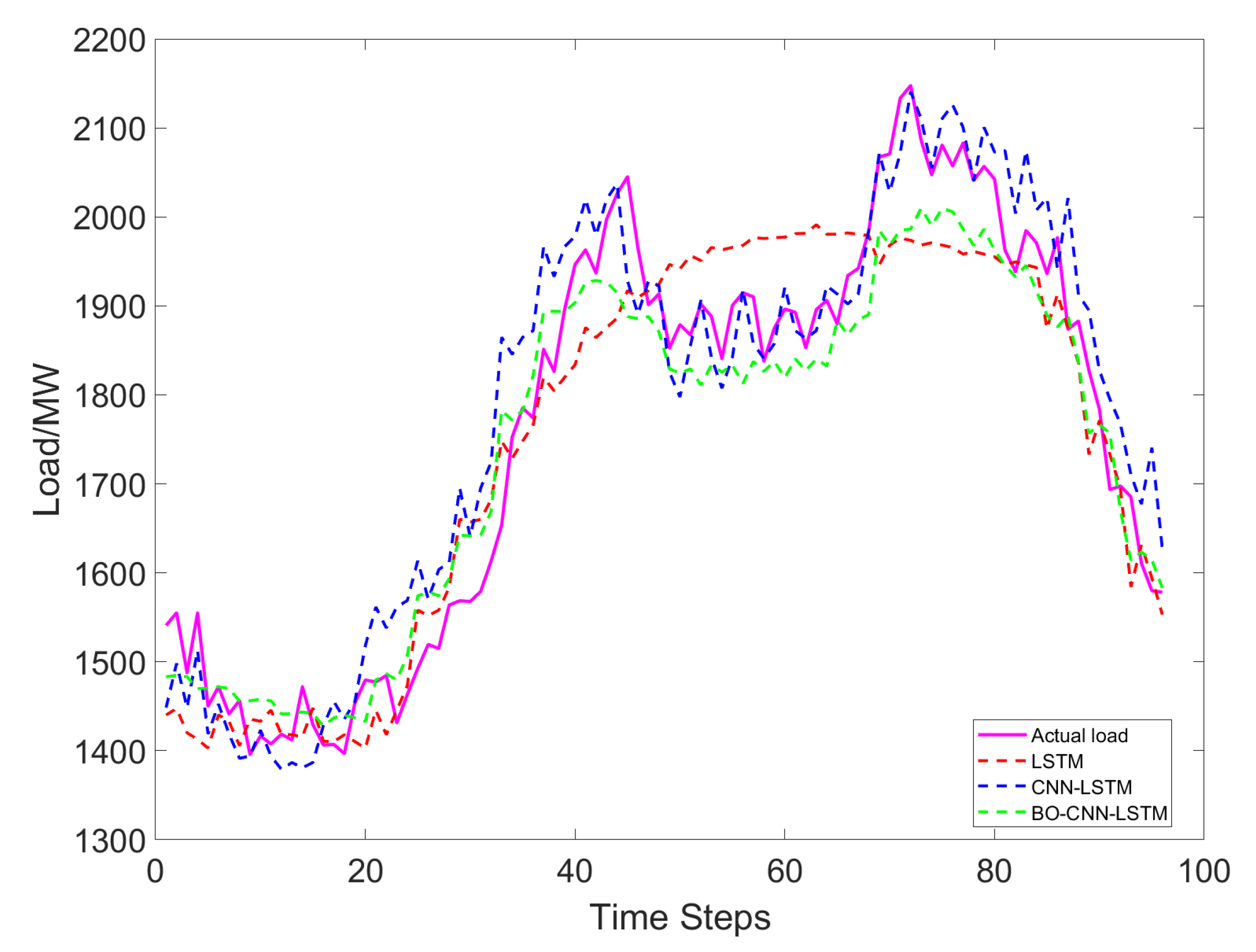

4.3.3. Load Forecasting for Industrial Alloy Smelting (Ablation Study)

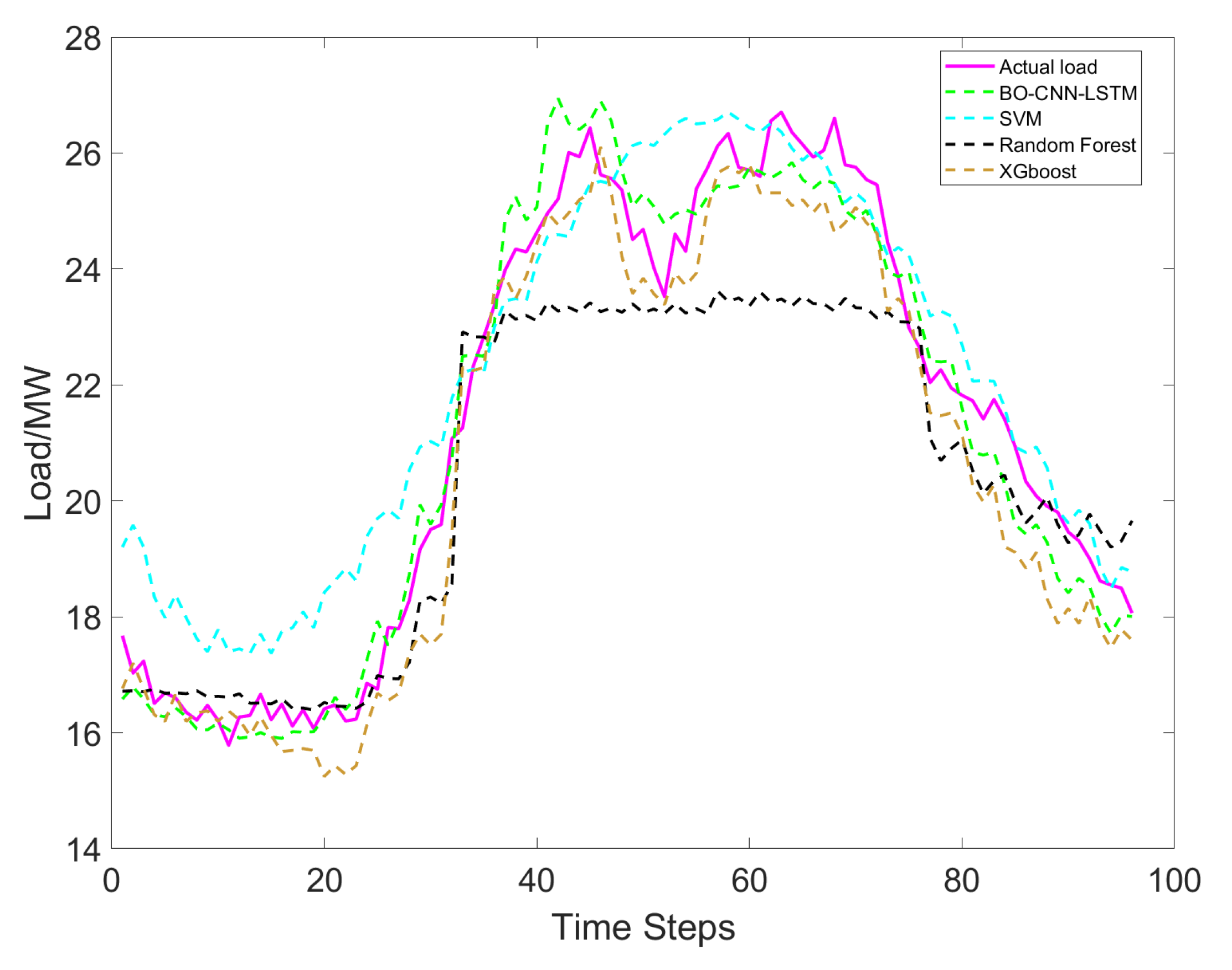

4.4. Comparison Results with Other Prediction Algorithms

4.4.1. Load Forecasting for Industrial Electrolytic Aluminum (Algorithm Comparison)

4.4.2. Load Forecasting for Agricultural Irrigation (Algorithm Comparison)

4.4.3. Load Forecasting for Industrial Alloy Smelting (Algorithm Comparison)

5. Conclusions

- Module contributions validated by ablation experiments: The ablation experiments conducted on three typical load datasets clearly demonstrate the role of each component. The results confirm the functional complementarity between CNN and LSTM, and underscore the critical importance of Bayesian optimization for automated hyperparameter tuning in maximizing the hybrid model’s predictive performance.

- Superior performance demonstrated through comparative analysis: Comparative experiments with SVR, Random Forest, and XGBoost demonstrate the proposed model’s superior accuracy and robustness across different load types, proving its enhanced capability in capturing complex spatiotemporal dependencies.

- Feature engineering and automated optimization are key enablers: The feature selection and Bayesian optimization strategy effectively enhanced data quality and model performance, improving the method’s practicality and reproducibility.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, C.Q.; Chen, Q.X.; Xia, Q. Prospects of low carbon electricity. Power Syst. Technol. 2009, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, C.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, S.; Yang, Z. Effect of market structure on renewable energy development—A simulation study of a regional electricity market in china. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 118911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Huang, A.P.; Xiao, J.R.; Cheng, T.; Liang, C. Analysis of power load forecasting technology based on deep neural networks. Electr. Technol. Econ. 2024, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, D.X.; Cao, S.H.; Lu, J.C. Power Load Forecasting Technology and Its Applications; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Sun, G.F.; Miao, S.W. Short term power load forecasting method based on multi dimensional time series information fusion. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Wan, C.; Cao, Z.J.; Li, Y.Y.; Ju, P. Short term probabilistic load forecasting based on conditional GAN curve generation. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2023, 47, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, K.J.; Ma, Y. Wind speed time series forecasting via seasonal index adjusted recurrent neural networks. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2022, 43, 444–450. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.L.; Li, T.H.; Liu, W.H. Short term power load forecasting using a similar day SAE DBiLSTM model. J. Electr. Eng. 2022, 17, 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Chodakowska, E.; Nazarko, J.; Nazarko, Ł. Arima models in electrical load forecasting and their robustness to noise. Energies 2021, 14, 7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Z.; Kong, C.; Chen, W. Short-term load forecasting based on linear regression under MapReduce framework. J. Lanzhou Univ. Technol. 2021, 47, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nijhawan, P.; Bhalla, V.K.; Singla, M.K.; Gupta, J. Electrical Load Forecasting using SVM Algorithm. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2020, 8, 4811–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Song, Y.B.; Jin, S.; Feng, J.; Shi, X.; Yu, Y.; Huang, X. An improved deep learning short-term load forecasting model based on random forest algorithm and rough set theory. Power Gener. Technol. 2023, 44, 889–895. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Yuan, J.; Chen, L. Short-term load forecasting using EMD-LSTM neural networks with a Xgboost algorithm for feature importance evaluation. Energies 2017, 10, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Yang, J.T.; Han, S.R.; Zhu, Z. Construction of building load forecasting model based on XGBoost-neural network. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 12604–12611. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.S.; Zhang, J. SVM based short term power load forecasting with time series. Mod. Inf. Technol. 2020, 4, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.K.; Zhu, Y.D. Power load forecasting via linear regression and exponential smoothing. Power Equip. Manag. 2021, 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, S.W.; Yu, H.M.; Jian, Z.M.; Zhao, Y. Large power load forecasting and billing based on an improved adaptive Kalman filter. Comput. Meas. Control 2023, 31, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.J. Transformer Fault Diagnosis Based on Grey Wolf Optimizer Tuned Support Vector Machine. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Zhengzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.; Zhou, X.C. Load forecasting and optimal dispatch of power systems using artificial neural networks. Autom. Appl. 2024, 65, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Cheng, P.; Hou, J.; Fan, T.; Han, L. Short term load forecasting of multi scale recurrent neural networks based on residual structure. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2023, 35, e7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, Z.P.; Ji, W.J.; Gao, X.; Li, X. Short term power load forecasting method based on attention mechanism of CNN-GRU. Power Syst. Technol. 2019, 43, 4370–4376. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G. Application of LSTM network under deep learning framework in short term power load forecasting. Electr. Power Inf. Commun. Technol. 2017, 15, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Gao, T.; Li, C.G.; Jiang, C.L. Short term power load forecasting using GRU neural network. Sci. Technol. Innov. Appl. 2018, 52–53+57. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Xiang, Y.F.; Ma, T.X. Short term power load forecasting based on EMD CNN LSTM hybrid model. J. North China Electr. Power Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 49, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.L.; Fang, H.B.; Zhu, X.X.; Hu, L.; Qi, L. Stock prediction based on XGBoost model optimized by grid search. J. Fuyang Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 38, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Q.Q.; Tang, X.Y. Prediction model based on R language algorithm and random search—Taking heart failure death risk prediction as an example. Mod. Inf. Technol. 2024, 8, 91–93+98. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.L.; Ju, X.; Zhang, Y.F.; Huang, Y.C. Random-forest hyper parameter optimization via improved random search algorithm. Netw. Secur. Technol. Appl. 2022, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.B.; Wei, T.T.; Jia, H.; Li, S. Photovoltaic power generation forecasting based on genetic algorithm. J. Zhongyuan Univ. Technol. 2024, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q.; Li, Q.; Quan, W.; Pei, X.M. Overview of multi objective particle swarm optimization algorithms. Chin. J. Eng. 2021, 43, 745–753. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.R.; Wang, Y.C.; Yuan, L.Z. Short term power load forecasting based on SSA-CNN-LSTM. Mod. Ind. Econ. Inf. 2024, 14, 169–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.Z. Research on 10kV Distribution Network Single Phase Grounding Fault Line Selection. Master’s Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Jia, R.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H. A hybrid wind power forecasting approach based on Bayesian model averaging and ensemble learning. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 2426–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.Y.; Jin, F.; Dong, L.; Zhang, S.; Yu, K.Y. Photovoltaic power station data reconstruction based on Pearson correlation coefficient. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, R.; Ma, Y. Incorporating deep learning of load predictions to enhance the optimal active energy management of combined cooling, heating and power system. Energy 2021, 233, 121134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 107.88 | 82.59 | 4.66 |

| CNN-LSTM | 56.32 | 46.18 | 2.64 |

| BO-CNN-LSTM | 38.38 | 30.46 | 1.69 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 1.12 | 1.02 | 4.88 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.8 | 0.64 | 3.11 |

| BO-CNN-LSTM | 0.68 | 0.57 | 2.63 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 75.41 | 62.82 | 3.47 |

| CNN-LSTM | 66.69 | 52.76 | 3.10 |

| BO-CNN-LSTM | 61.67 | 51.09 | 2.84 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 92.65 | 79.01 | 4.6 |

| Random Forest | 69.2 | 54.14 | 2.98 |

| XGBoost | 61.18 | 49.49 | 2.75 |

| BO-CNN-LSTM | 38.38 | 30.46 | 1.69 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 1.27 | 1.04 | 5.39 |

| Random Forest | 1.5 | 1.17 | 5.05 |

| XGBoost | 0.94 | 0.78 | 3.71 |

| BO-CNN-LSTM | 0.68 | 0.56 | 2.63 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 91.94 | 78.51 | 4.6 |

| Random Forest | 66.42 | 53.55 | 2.99 |

| XGBoost | 64.89 | 53.26 | 2.97 |

| BO-CNN-LSTM | 61.67 | 51.09 | 2.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, P.; Jiao, H.; Sun, J.; Han, A.; Dai, Z.; Cheng, L.; Chen, X. Research on Load Forecasting Based on Bayesian Optimized CNN-LSTM Neural Network. Energies 2025, 18, 6217. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236217

Duan P, Jiao H, Sun J, Han A, Dai Z, Cheng L, Chen X. Research on Load Forecasting Based on Bayesian Optimized CNN-LSTM Neural Network. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6217. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236217

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Pengyang, Huannian Jiao, Jianying Sun, Aiming Han, Zheng Dai, Liang Cheng, and Xiaotao Chen. 2025. "Research on Load Forecasting Based on Bayesian Optimized CNN-LSTM Neural Network" Energies 18, no. 23: 6217. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236217

APA StyleDuan, P., Jiao, H., Sun, J., Han, A., Dai, Z., Cheng, L., & Chen, X. (2025). Research on Load Forecasting Based on Bayesian Optimized CNN-LSTM Neural Network. Energies, 18(23), 6217. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236217