1. Introduction

The progression toward intelligent agriculture has significantly revolutionized modern greenhouse management practices, enhancing productivity, sustainability, and resource efficiency. Early greenhouse cultivation primarily relied on manual control and basic environmental regulation, including passive or minimally automated temperature and humidity adjustments [

1]. With technological advancement, these practices evolved into sophisticated automated control systems, integrating precise regulation of critical climatic factors such as temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide (CO

2) concentration, and artificial lighting [

2,

3]. This evolution improved microclimatic precision and significantly influenced overall crop yield and quality, responding dynamically to internal plant physiological requirements and external climatic variability [

4,

5]. Recent work has, for example, combined reinforcement learning with MPC–LSTM to improve supervisory energy management under variable conditions, illustrating the value of hybrid, learning-augmented controllers [

6].

Despite technological advances, managing greenhouse microclimates remains challenging due to complex interdependencies among various climatic parameters. Temperature fluctuations directly affect relative humidity levels and plant transpiration rates, thereby influencing photosynthesis efficiency and nutrient uptake [

7,

8]. Additionally, artificial lighting systems provide essential light energy for plant growth but also significantly impact thermal dynamics and CO

2 assimilation processes within greenhouse environments [

9,

10]. Such couplings make simple on/off or relay strategies suboptimal; comparative studies in controlled horticulture environments have shown that MPC-based climate control outperforms traditional relay logic in tracking precision and energy efficiency, underscoring the need for predictive, constraint-aware control in CEA [

11].

These challenges become particularly critical under constrained resource conditions, such as limited energy availability or water scarcity. Optimal simultaneous control of all parameters becomes impractical under such constraints, necessitating prioritization based on their relative importance to crop productivity and sustainability [

12]. Prioritization aids decision-makers in effectively allocating limited resources to manage the most influential parameters optimally, thus maintaining critical environmental conditions even during extreme resource limitations [

13].

In addressing these complex management scenarios, multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approaches, particularly the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), have demonstrated significant effectiveness. AHP systematically structures complex decisions into a hierarchical model, utilizing expert evaluations to determine precise weighting and prioritization of multiple parameters [

14,

15]. García et al. [

16] extensively reviewed the versatility of AHP, underscoring its successful implementation across various industries, notably agriculture. Recent applications in agriculture highlight AHP’s strength in systematically capturing and integrating expert knowledge to enhance decision-making quality and resource allocation efficiency [

17,

18].

In parallel, multi-criteria decision-making methods like the AHP offer structured frameworks to prioritize interdependent climate variables. AHP enables experts to evaluate and weigh parameters such as temperature, humidity, and CO

2—whose interactions are critical to ensuring balanced and efficient climate control strategies [

19]. This capacity to quantify expert judgment makes AHP particularly suited for greenhouse management, where multiple, often conflicting environmental variables must be managed simultaneously.

Parallel developments in Model Predictive Control (MPC) have further enhanced strategic greenhouse environmental management. MPC, characterized by its predictive and adaptive control capabilities, enables proactive adjustment of environmental management strategies based on predicted future conditions [

19,

20]. Numerous studies validate MPC’s effectiveness in optimizing energy usage, water resources, and improving overall environmental control compared to traditional control methods [

21,

22,

23].

Despite the proven strengths of MPC and the AHP, their combined use in greenhouse management remains limited. Most MPC frameworks treat all climate variables equally, overlooking agronomic priorities. This often leads to inefficient resource use, especially under constraints like water scarcity or limited energy. While MPC excels in prediction and dynamic control, it is rarely guided by expert-informed weighting aligned with real agricultural needs.

Traditional rule-based systems also fall short, as they lack anticipation, adaptability, and the ability to handle conflicting objectives. In contrast, integrating AHP-derived priorities into MPC enables more intelligent, multi-objective control that dynamically allocates resources based on agronomic significance. Yet, such integration remains underexplored.

Building on these ideas, this study embeds expert-elicited AHP priorities directly into a multi-objective Model Predictive Controller that jointly manages microclimate, irrigation, and energy dispatch over a hybrid PV-wind-battery-grid system. This approach aligns control actions with agronomic priorities rather than purely technical balancing. Similar developments in other controlled agricultural environments (e.g., predictive control in poultry houses) support the broader applicability of optimization-based strategies for CEA [

24].

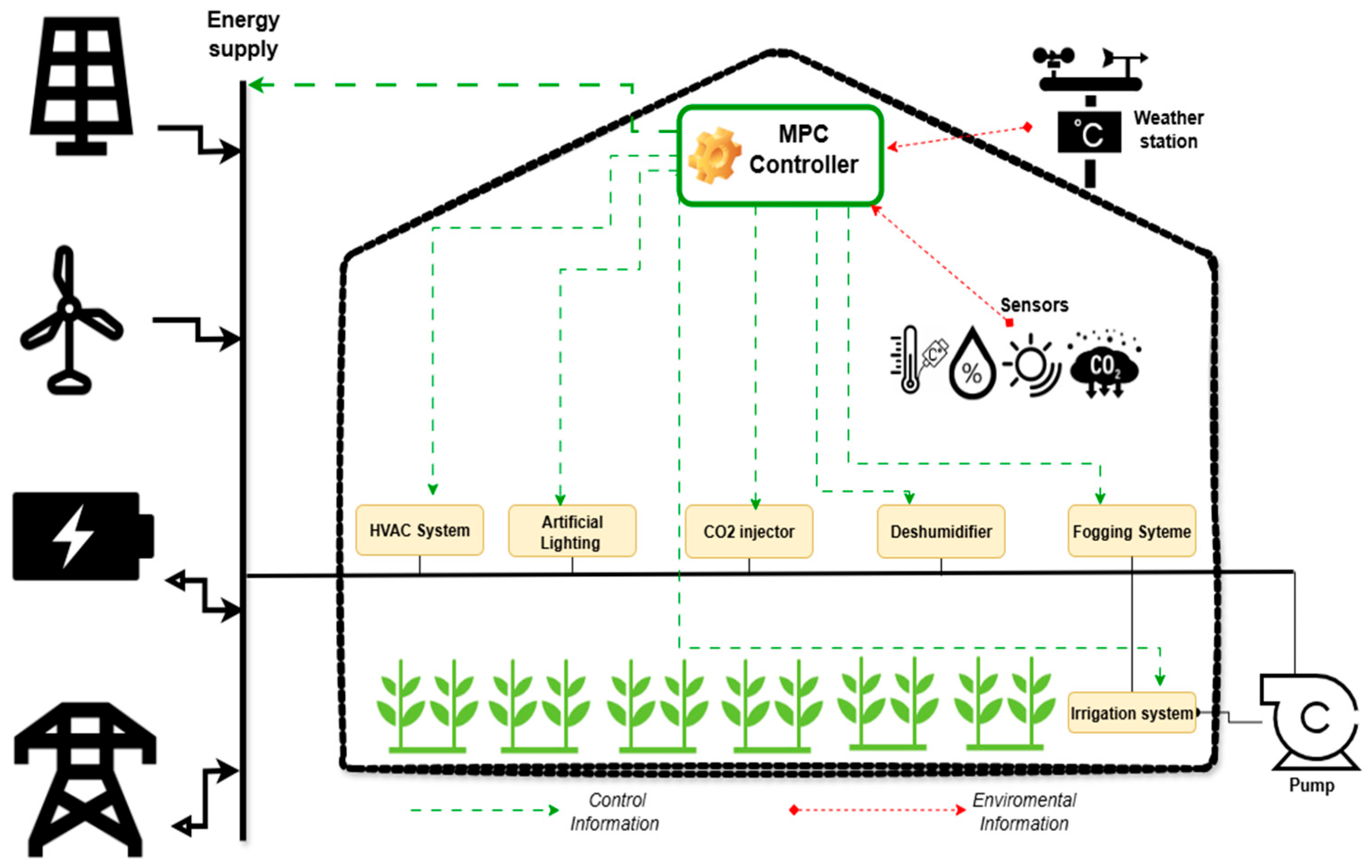

The controller regulates HVAC, (de)humidification, CO

2 dosing, LED lighting, and irrigation while coordinating energy flows from PV, wind, battery, and grid sources. It is evaluated over two 72 h seasonal episodes (Kenitra, Morocco) using tracking KPIs (NRMSE, SMAPE) and energy KPIs (source shares, peak grid import).

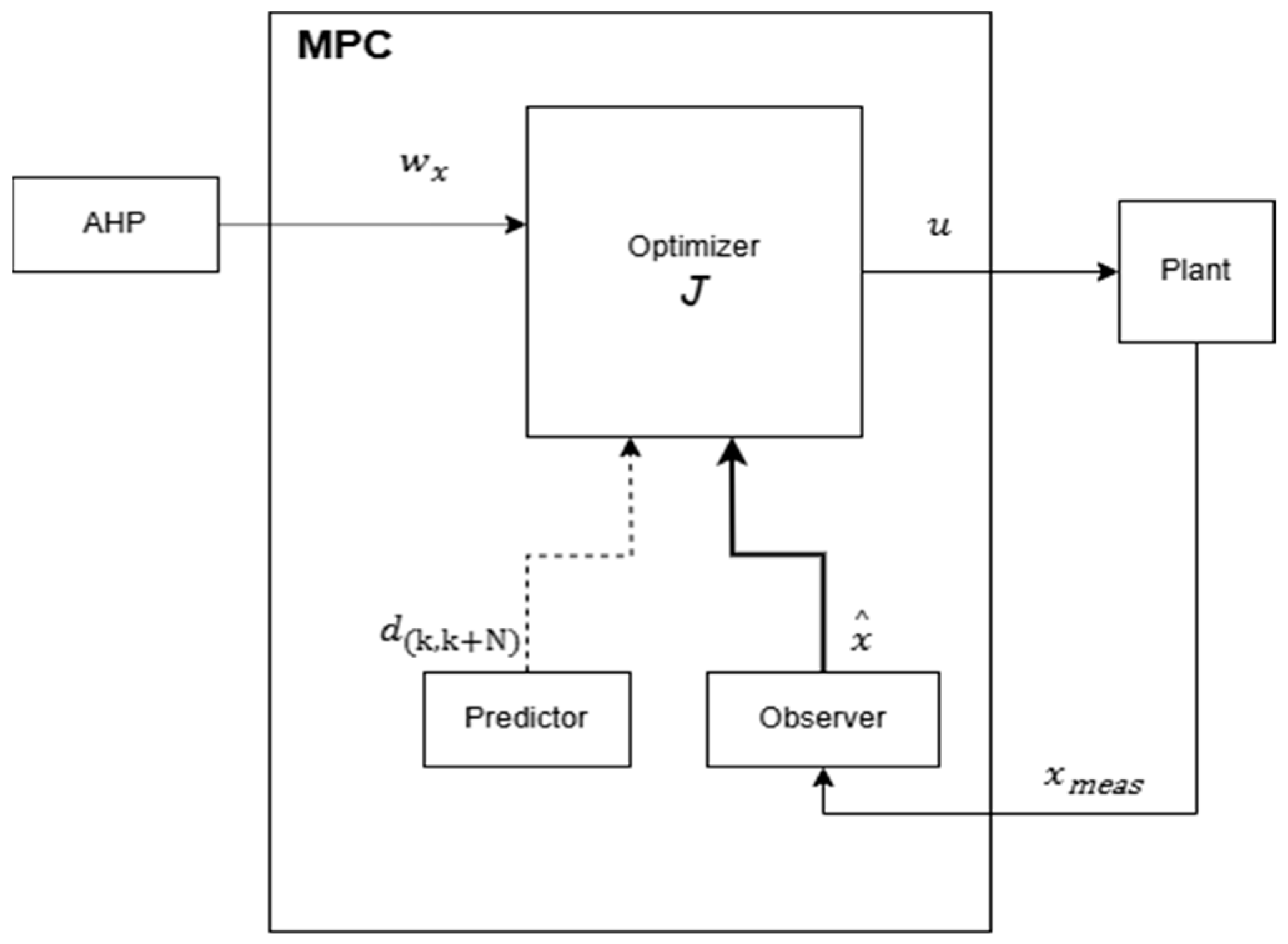

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 present the greenhouse architecture and the integrated AHP–MPC control scheme; each component is detailed in the following sections.

3. Study Design and Methods

This section describes the research materials and methodology used in the study, encompassing the expert survey and weighting procedure, the greenhouse–microgrid assets, the mathematical models of climate and energy subsystems, the predictive control setup, and the governing energy-balance equations.

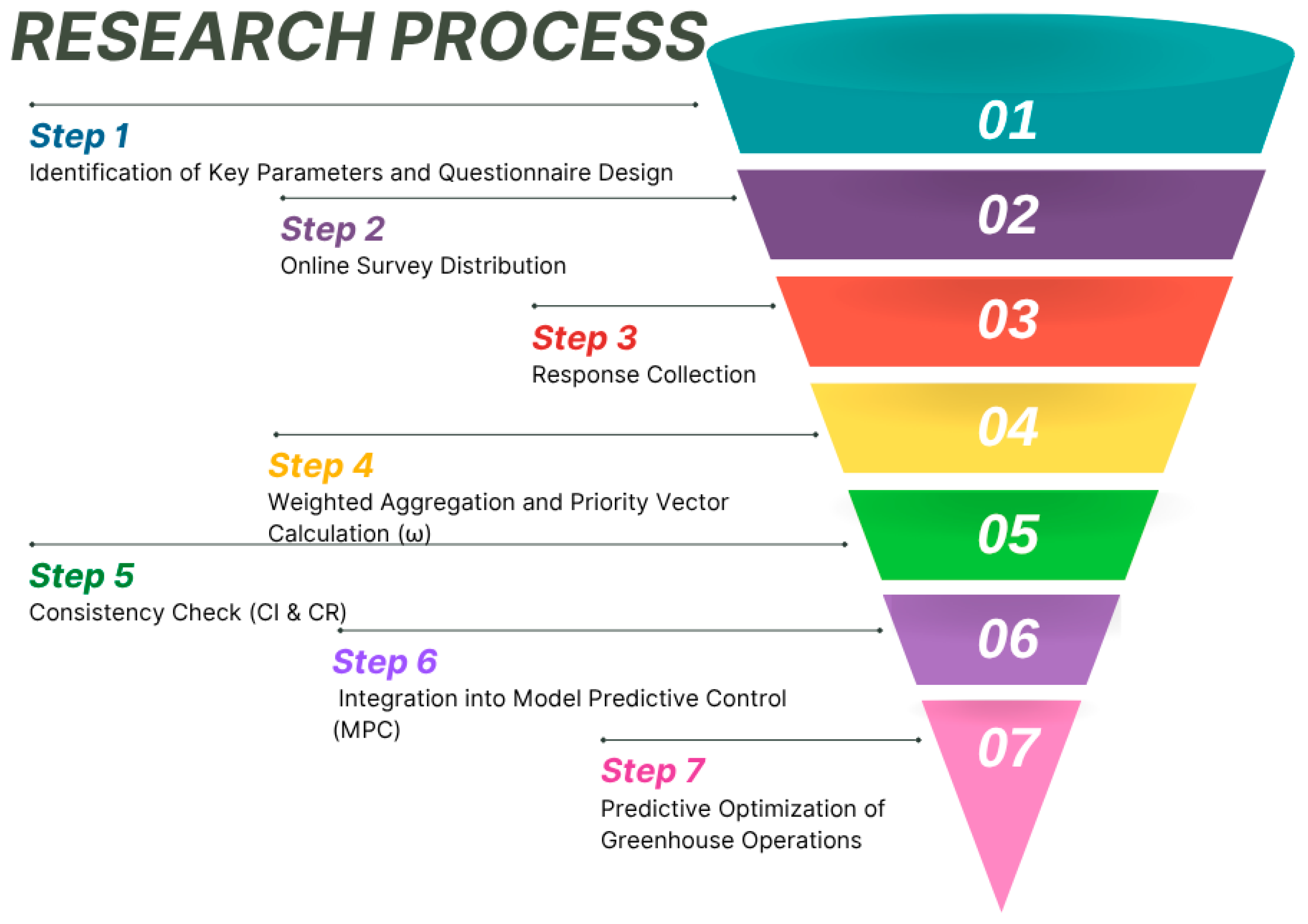

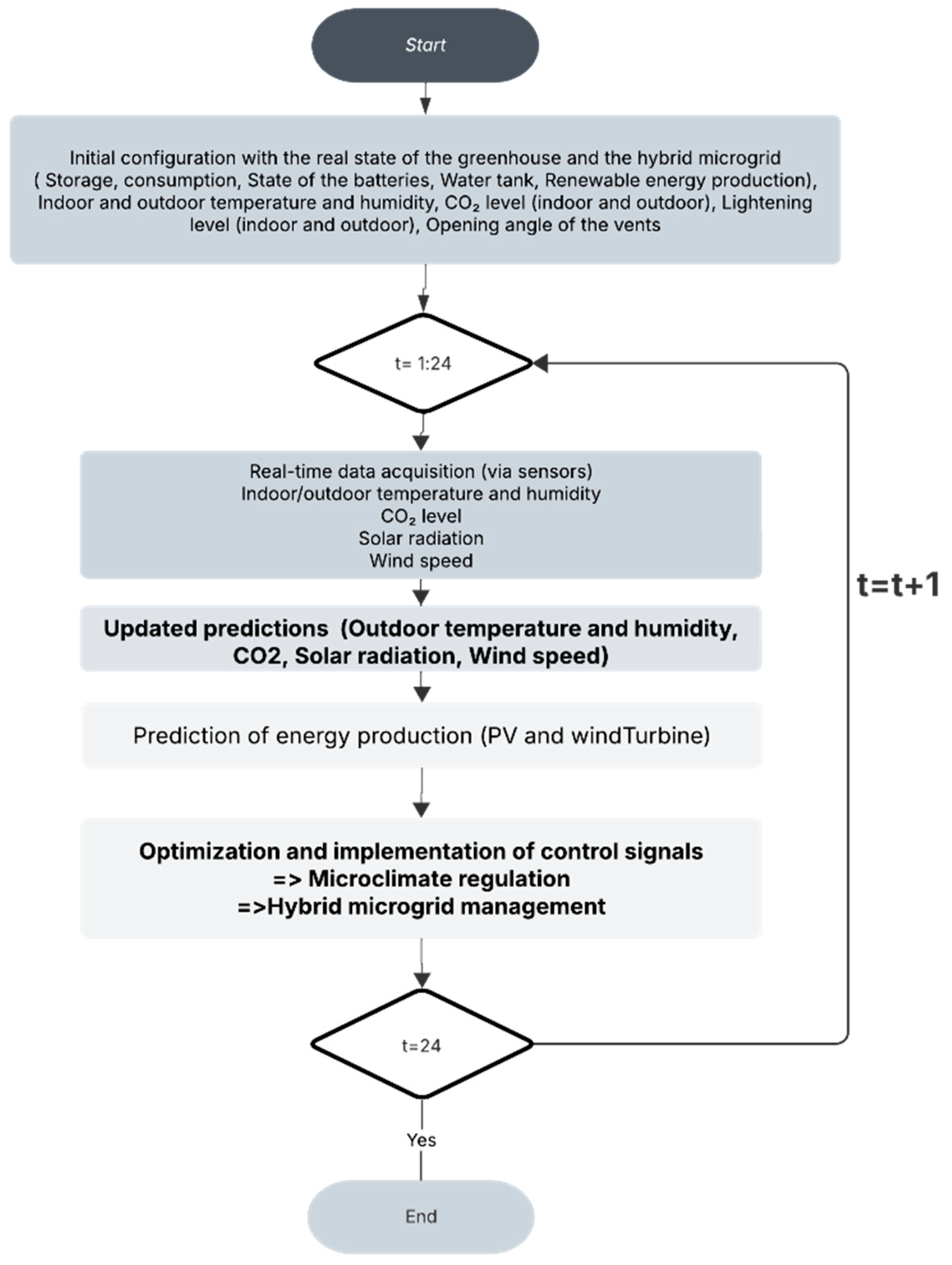

The methodology follows a structured seven-step pipeline that connects expert knowledge to predictive control (see

Figure 3). First, relevant greenhouse climate criteria are identified, and a detailed questionnaire is designed. The survey is then deployed online to professionals across multiple domains, and responses are collected. Pairwise judgments from experts are aggregated using a weighted geometric mean and converted into a priority vector ω via the principal eigenvector method. Logical coherence of the responses is verified through the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) consistency index and ratio.

The resulting expert-informed weights are then embedded in a multi-objective Model Predictive Control (MPC) cost function, which balances climate tracking with energy consumption. This controller operates in a receding-horizon fashion over seasonal test episodes, dynamically scheduling HVAC, (de)humidification, CO2 dosing, lighting, and irrigation. Simultaneously, it orchestrates the operation of PV panels, wind turbines, battery storage, and grid interaction to achieve predictive optimization of the greenhouse–microgrid system.

3.1. AHP Survey Materials and Questionnaire Design

This study employed a structured methodology inspired by established multi-criteria decision-making techniques, specifically the AHP [

33].

The primary objective was to identify and prioritize the key climatic parameters essential for effective greenhouse climate control. This process began with a literature review and expert consultations to select five core parameters: temperature, humidity, CO2 concentration, artificial lighting, and irrigation.

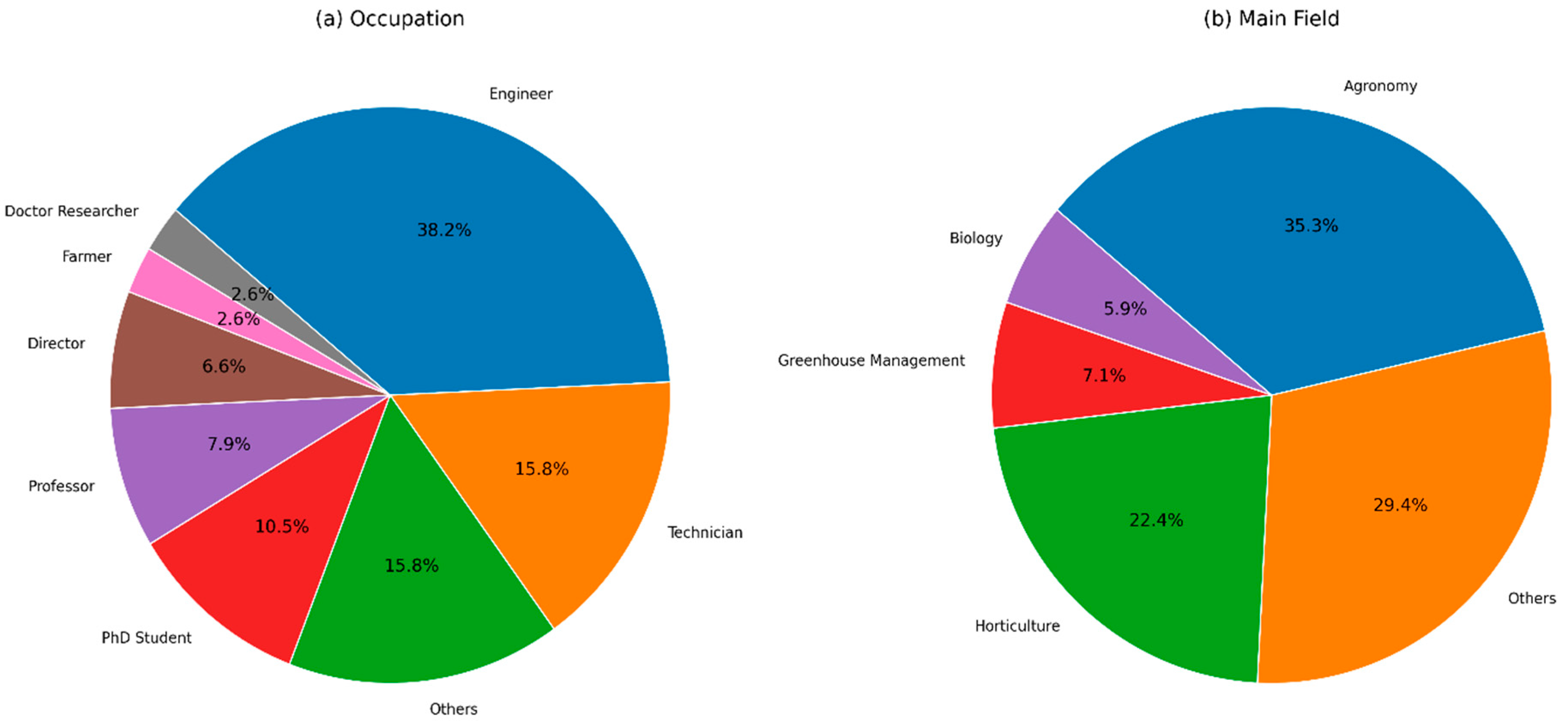

A diverse group of professionals—including agricultural engineers, technicians, researchers, PhD students, professors, farmers, and facility managers—participated in the survey. Their inclusion ensured a balanced representation of expertise across agriculture, horticulture, engineering, and greenhouse operations, providing a broad and practical perspective.

The questionnaire was administered online and consisted of two sections. The first section gathered information on the respondents’ profiles—including their role or sector, years of experience in greenhouse production, primary crop types, and key characteristics of their facilities—allowing for a contextualized interpretation of the responses. The second section implemented the AHP pairwise comparison procedure across the selected climate and irrigation criteria (temperature, irrigation, humidity, lighting, and CO

2). For each pair, experts were asked to evaluate the relative importance of one criterion over another by assigning a value on Saaty’s 1–9 scale (as shown in

Table 1). Only the upper triangle of the comparison matrix was completed manually; reciprocal values for the lower triangle were generated automatically to ensure consistency.

Experts were requested to make pairwise comparisons among the climatic parameters using this scale, enabling clear and structured quantification of expert judgments.

A total of 69 professionals participated in the survey. The participant group, predominantly composed of experts based in Morocco with a limited number of contributors from the Netherlands, encompassed a range of professional roles as summarized in

Figure 4a.

The participants specialized predominantly in agronomy (35.3%), horticulture (22.4%), greenhouse management (7.1%), and plant biology (5.9%). Other specialized fields such as irrigation science, biotechnology, renewable energy, and agricultural data science were also represented.

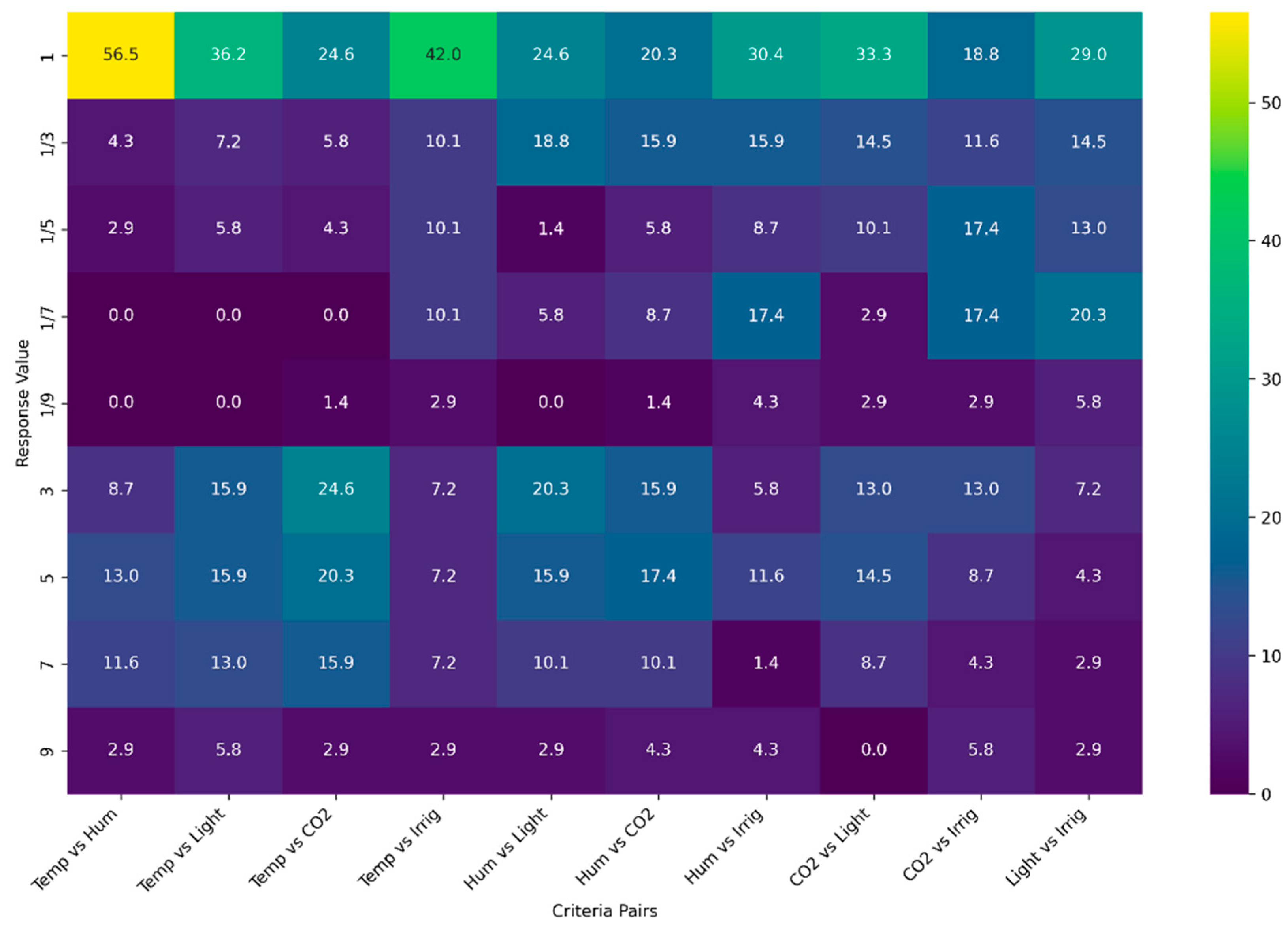

Figure 5 presents a heatmap displaying the percentage distribution of respondents’ judgments for each pairwise comparison of climatic parameters. Each cell indicates the proportion of participants assigning a given AHP importance value (as defined in

Table 1) to a parameter pair. This visualization reveals prevailing trends and areas of consensus or divergence among experts, offering a clear and intuitive interpretation of their prioritization preferences.

Following the collection of survey data, an analytical weighting procedure was applied to responses based on the respondents’ self-reported experience levels in two critical areas: greenhouse management and crop physiology. The experience was scored as described in

Table 2.

Each respondent’s experience level in greenhouse management and crop physiology was individually assessed, and an average experience score was computed. These scores were then normalized so that their total equaled one, assigning higher weights (ω) to responses from more experienced experts.

The weighted scores were incorporated into the AHP analysis to enhance its accuracy by prioritizing expert judgments based on experience. This process produced refined AHP weighting coefficients that more precisely reflect collective expert insight. These coefficients are then integrated into the MPC system, aligning climate control strategies with expert-derived priorities to improve operational efficiency and sustainability.

3.2. Weight Derivation from Expert Judgments

To aggregate judgments from multiple respondents while accounting for their relative importance, we use a weighted geometric mean. For pair (

i,

j), denote by

the set of respondents who provided a valid judgment

(Saaty scale), and by

the non-negative weight assigned to respondent

K. We normalize these weights over the responding subset

, and compute [

34,

35]

is the judgment provided by respondent k for the pair (i,j).

is the normalized weight of respondent k.

K is the number of respondents who provided a valid judgment for this comparison.

is the sum of the weights of respondents who rated the pair (i,j).

This multiplicative form preserves the AHP scale structure and reciprocity and reduces to the classical geometric mean when all respondents have equal weight. Judgments are strictly positive, ensuring that the logarithm is well-defined.

According to reference [

36], a judgment matrix A

k (k = 1, 2, …, q) is constructed from the evaluations provided by the

k-th respondent. As shown in Equation (2), A

k is a positive reciprocal matrix of order n.

The elements

(for

i,

j = 1,2,…,

n) represent the relative importance of the

i-th objective compared to the

j-th objective according to respondent

k. In other words,

indicates how much more important objective

i is relative to objective

j.

The matrix has reciprocal properties, which are

To determine the relative importance of the criteria, the aggregated pairwise comparison matrix was formed using the weighted geometric mean of individual expert judgments. The priority vector—which represents the criteria weights—was then computed using the principal eigenvector method.

This vector

satisfies the eigenvalue equation [

33]:

where

A is the aggregated comparison matrix.

is its largest eigenvalue.

is the corresponding eigenvector.

To ensure a consistent interpretation, the eigenvector is normalized so that the sum of weights equals 1:

where

is the

i-th component of the principal eigenvector and n is the total number of criteria.

This method provides a mathematically consistent and interpretable way to extract the relative weights of the criteria, aligning them with expert judgment.

The Consistency Index (CI) [

37] evaluates the coherence of a pairwise comparison matrix. It is computed using the matrix’s principal eigenvalue

:

where

n is the number of criteria. Perfect consistency yields have

, resulting in

.

The Consistency Ratio (CR) assesses this CI against a Random Index (RI)—the average CI of randomly generated matrices of the same order [

38]:

For a matrix of order n = 5, the standard RI is 1.12. A CR value below 0.1 indicates acceptable consistency in the expert judgments

3.3. Advanced Predictive Energy Management Framework

The proposed framework autonomously manages and optimizes energy distribution in a greenhouse connected to a hybrid microgrid. It begins by assessing the current state of the greenhouse and energy system, including battery charge, water reserves, energy consumption, renewable production, climatic conditions (indoor/outdoor temperature, humidity, CO2, lighting), and vent status.

At each hourly time step, real-time sensor data covering temperature, humidity, CO2 levels, solar radiation, and wind speed feeds predictive models that forecast environmental conditions. These forecasts inform the Energy Management System (EMS), which estimates renewable generation from PV panels and wind turbines.

The central controller then applies optimization rules to generate control signals for actuators, ensuring climate conditions stay within optimal ranges while respecting system constraints. Its main objective is to allocate renewable energy efficiently, balancing greenhouse demands with supply variability.

When excess energy is available, it is either stored in batteries or fed back to the grid, improving energy resilience and reducing waste. This proactive control enhances both operational efficiency and sustainability.

The basic structure of the MPC is illustrated in

Figure 6 [

39]:

The implemented Model Predictive Control approach utilizes a dynamic model to forecast system behavior over a prediction horizon (Np) at each control step. Based on these forecasts, it evaluates the impact of different energy flow scenarios to align future conditions with target setpoints.

Following the receding horizon principle, only the first control action of each optimized sequence is applied, and the process is repeated at the next interval using updated data. This ensures continuous re-optimization and adherence to system constraints.

In this setup, the MPC manages lighting, heating, dehumidification, CO2 injection, irrigation, and grid interactions. It solves an online optimization problem over a control horizon (Nc) to minimize a multi-objective cost function, enabling efficient, predictive, and sustainable greenhouse and energy system management.

3.4. Mathematical Models of the System

The objective function is designed to minimize both the energy drawn from the main grid and deviations from optimal environmental setpoints for greenhouse operation. These setpoints include internal temperature, soil moisture, artificial lighting, CO2 levels, and irrigation ensuring system reliability and high agricultural quality.

Formulated as a multi-objective quadratic cost function, the optimization balances microclimate control with operational efficiency. The first five terms penalize deviations from reference trajectories for each key variable, while an additional term minimizes reliance on grid energy, encouraging the use of local renewable sources.

The overall objective function to be minimized is defined as follows:

where each deviation term is weighted by coefficients

derived from an AHP based on expert input, ensuring that the prioritization of control objectives reflects agronomic needs.

The dynamic deviations are subject to a series of predictive constraints that maintain each state variable within a defined tolerance margin around its optimal reference:

The predictive framework enables proactive environmental control by anticipating future climatic conditions, optimizing resource use, and supporting sustainable agriculture. This requires accurate dynamic models of the greenhouse microclimate and hybrid energy system. These models capture the behavior of key variables—temperature, humidity, CO2, lighting—and energy flows from PV, wind, storage, and grid interaction. The following section details their mathematical formulation, which forms the core of the MPC’s predictive engine.

3.4.1. Greenhouse Dynamic Modeling (GDM)

The greenhouse microclimate is represented by a coupled, discrete-time state model that captures heat and mass exchanges, gas balance, illumination, and water storage/transport. Indoor air temperature

evolves according to a lumped first-order RC relation with HVAC actuation (Equation (14)) [

40]:

where

is the global thermal resistance,

the air heat capacity,

the forecast outdoor temperature,

the HVAC power, and

∈ {−1, 0, +1} encodes cooling/idle/heating.

Admissible temperatures are enforced by bounds:

Moisture is modeled via the absolute water content of air w(t) [g/m

3], updated by a mass balance that aggregates evapotranspiration, ventilation exchange, and active (de)humidification (Equation (16)). The ventilation term uses a ventilation conductance

and a psychrometric saturation relation (Tetens-type) parameterized by (c1, …, c5) and Patm (Equation (17)). Fogging and dehumidification contributions are proportional to the greenhouse floor

and the respective control inputs

(t),

(t) with maxima

and

(Equations (18) and (19)). To keep relative humidity within target comfort limits, w(t) is constrained between

and

computed from the admissible indoor RH band and the predicted

(Equations (20)–(22)). Mutual exclusivity avoids simultaneous humidification and dehumidification (Equation (23)) [

41].

Carbon dioxide is the most vital gaseous nutrient after water, directly affecting photosynthesis. Although ambient levels average ~400 ppm, increasing internal CO

2 in greenhouses significantly enhances crop growth, improving biomass, height, leaf and flower development, and branching in various species [

42].

Indoor CO

2 concentration follows a balance among injection, plant assimilation, and ventilation losses (Equation (24)). The injection term depends on the valve command

, the injected concentration

, and the gas supply pressure

(Equation (25)). Assimilation is captured by a saturating response to ambient CO

2 and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), combining the predicted global irradiance

and LED contribution

(Equation (26)). Ventilation induces dilution toward the outdoor level

with rate

(Equation (27)). CO

2 is kept within agronomic bounds (Equation (28)).

Light is a critical factor for plant growth, influencing both photosynthesis and key developmental processes such as germination, elongation, and flowering. These effects depend on light intensity, photoperiod, and spectral composition [

33]. In greenhouses, artificial lighting especially energy-efficient and spectrum-adjustable LEDs is used to supplement natural light, particularly in low-radiation conditions, helping maintain optimal growth and productivity [

27].

Artificial lighting supplements natural light to maintain the prescribed photoperiod. The required luminous flux scales with the illuminated area (Equation (29)). A threshold policy activates LEDs when predicted irradiance falls below

; electrical power follows the fixture efficiency

(Equation (30)).

Water supply is represented by a storage-and-delivery chain. The reservoir state

integrates the inflow from a source pump and the outflow to irrigation (Equation (31)) [

43], with hydraulic flows linked to pump powers

,

, heads

,

, efficiency

, and (

) (Equations (32) and (33)). Capacity limits (Equation (34)) prevent overflow and dry-tank operation. Together, Equations (14)–(34) define a compact, physically grounded model that the predictive controller uses to track climate references, schedule irrigation, and coordinate energy flows under operational constraints

3.4.2. Microgrid Dynamic Modeling (MDM)

Wind Turbine Power Generation Model

Wind energy is a renewable and naturally abundant source; whose availability depends on the local wind profile. The electrical power output of a wind turbine varies non-linearly with wind speed and is governed by the turbine’s operational characteristics, such as cut-in, rated, and cut-out speeds.

The power output

at time t is determined according to the following piecewise model [

44]:

The power output of the WTPG module is limited between the upper and lower bounds.

Photovoltaic Power Generation Model

Photovoltaic (PV) systems convert solar irradiance into electrical energy through semiconductor materials. The output power of a PV panel depends primarily on the level of solar irradiance, the ambient temperature, and the temperature sensitivity of the PV module.

In this work, the PV power output

at time t is estimated using the following relation [

44]:

This model accounts for the nonlinear impact of ambient temperature on PV performance, where higher temperatures typically reduce module efficiency. The irradiance-normalized term ensures that output power scales with incident solar energy, and the thermal correction reflects real environmental operating conditions.

The power output of the PV module is limited between the upper and lower bounds:

Energy Storage System Dynamics

To balance supply and demand within the greenhouse microgrid, an Energy Storage Unit (ESU), typically a battery, is used to buffer renewable energy fluctuations and reduce grid dependence. Its energy level is modeled as a discrete-time state variable updated through charge/discharge actions, accounting for efficiency losses [

45]:

The energy level is constrained by the physical capacity of the battery:

Likewise, the charging and discharging power rates are bounded by the inverter or battery specifications:

To avoid simultaneous charging and discharging, which is physically infeasible and energetically wasteful, the following constraint is imposed:

This logical constraint ensures that the controller selects either a charging or discharging mode at each time step, but never both. This ESU model is embedded into the predictive control framework to support optimal power flow and load balancing within the greenhouse energy system.

Electrical Grid Interaction Model

The electrical grid is modeled as an unlimited energy source and sink. It allows the greenhouse system to draw power at any time to meet energy deficits and inject surplus renewable generation without restrictions. No technical or capacity constraints are imposed on grid usage.

The grid exchange is directly embedded in the objective function as a cost-related term to discourage unnecessary dependence on the grid and to promote local energy autonomy. A higher weight on this term can encourage the controller to prioritize renewable sources and storage over grid usage.

3.5. Energy Balance and State Equations

At each prediction step t + k, the energy balance of the greenhouse system is enforced through the following algebraic equation, ensuring that the total power supplied by local sources and the grid equals the total power demanded by all actuators and charging systems:

With .

This compact formulation is essential for enforcing the energy conservation law in the predictive controller, ensuring feasible and efficient energy allocation across all systems at each control step.

4. Simulation Setup

The simulation spans 72 h (1 h resolution) to test an AHP-weighted Model Predictive Controller that optimally operates HVAC, LED lighting, CO

2 injectors, humidification/dehumidification systems, and irrigation pumps (see

Section 3.4.1, GDM). Energy is sourced from PV panels, a wind turbine, a lithium-ion battery, and the grid (see

Section 3.4.2, MDM). Optimization uses the Sequential Least Squares Programming (SLSQP) algorithm from scipy.optimize.minimize [

46,

47].

The simulation is nonlinear, multi-objective, and subject to multiple constraints, aiming not only to test the stability of the controller but also to evaluate its energy efficiency and agronomic performance.

The test site is an 80 m2 even-span greenhouse (ridge height 4.3 m), with geometry feeding into the thermal, humidity, CO2, and ventilation models.

Climate and Irrigation Setpoints:

Temperature: 17 °C (night/early morning) and 22 °C (daytime).

Humidity: Maintained between 60–70%.

CO2: Varies from 500 to 920 ppm, peaking during peak photosynthesis.

Irrigation: Pulsed at 0/0.025 m3/h based on water demand.

Lighting: LEDs extend the photoperiod to 20 h/day, activating under low irradiance.

These parameters follow agronomic guidance for tomato production in Mediterranean greenhouses [

48,

49].

Seasonal Scenarios:

Figure 7 presents two contrasting 72 h weather scenarios in Kenitra, Morocco, showing six key climate variables: air temperature, relative humidity, CO

2 concentration, wind speed, solar radiation, and vapor pressure deficit (VPD).

June (Summer): Displays higher temperatures, strong solar radiation, increased wind speed, and a higher VPD, indicating hot and dry conditions. The MPC system focuses on cooling and humidity regulation, while artificial lighting is rarely needed due to high natural irradiance.

December (Winter): Characterized by lower temperatures, reduced solar input, frequent high humidity, low wind, and lower VPD, reflecting cooler and more humid conditions. The MPC strategy shifts toward heating, dehumidification, and the use of supplemental lighting to maintain optimal indoor conditions.

Ambient CO2 levels remain stable across both seasons and primarily affect internal concentrations through the ventilation system.

Initial Conditions:

At t0, internal temperature is 18 °C, RH is 63%, CO2 is 500 ppm, and the battery is at 5 kWh. Sub-models handle each subsystem—thermal exchange (HVAC), latent/moisture balance (humidity), mass balance (CO2), crop-water dynamics (irrigation), and coulomb counting (battery). Renewable generation is updated hourly from irradiance and wind forecasts.

This setup evaluates how the AHP-guided MPC dynamically reallocates energy to meet crop needs amid seasonal fluctuations in renewable availability.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the main results of the intelligent greenhouse climate–energy management framework, structured into three parts: (i) priority weight derivation using the AHP, (ii) closed-loop performance in tracking climate setpoints (temperature, humidity, CO2, lighting, irrigation), and (iii) seasonal energy orchestration, highlighting how PV, wind, battery, and grid resources are allocated during summer and winter periods.

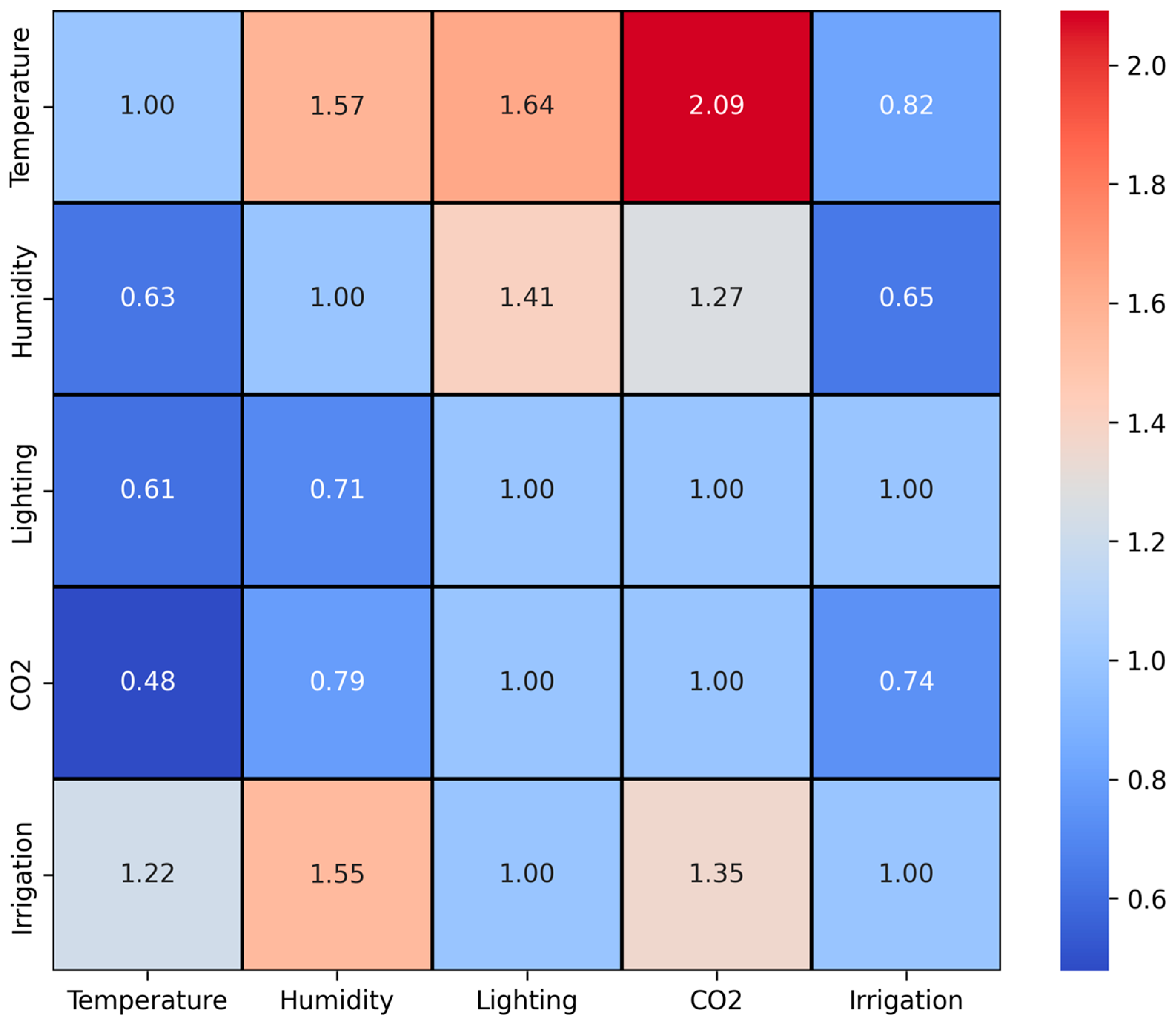

The decision weights used in the AHP-based control scenario were obtained through a structured multi-criteria analysis involving agricultural experts. Based on pairwise comparisons of the importance of five climatic parameters temperature, humidity, lighting, CO

2 concentration, and irrigation, a judgment matrix was constructed. This matrix is presented in

Figure 8, where each element

represents the degree of importance of criterion i over criterion j, based on the collective opinion of all respondents.

The matrix displays a consistent preference toward temperature and irrigation over the other criteria. For instance, temperature was judged to be approximately 2.09 times more important than CO2, and 1.64 times more important than lighting, indicating strong perceived influence on crop productivity and energy consumption. Meanwhile, CO2 and lighting exhibited values closer to 1 when compared with each other or with humidity, suggesting they are seen as moderately important but less dominant.

To validate the coherence of expert judgments, the consistency index (CI) and consistency ratio (CR) were calculated. The matrix yielded a CI of 0.0195 and a CR of 0.0174, well below the threshold of 0.1. This confirms that the expert inputs were logically consistent and statistically acceptable.

The final normalized weights derived from the AHP matrix are summarized in

Table 3 and were directly integrated into the objective function of the Model Predictive Controller (MPC) for the AHP-based control scenario. These weights define the relative priority of each actuator in the optimization process, allowing the controller to dynamically prioritize decisions based on expert-defined agronomic objectives rather than relying on purely technical balancing. Similar multi-criteria approaches in greenhouse control underscore the importance of such expert-informed weighting. For instance, Hu et al. note that simple weighted-sum control can be very sensitive to weight choice [

50], so obtaining robust weights (as through AHP) is crucial. By incorporating the finalized weights into the MPC cost function, the control strategy explicitly reflects agronomic priorities rather than treating all deviations equally. This expert-driven prioritization is expected to yield more agronomically sensible control actions than a purely technical or ad hoc weighting.

These weights serve as a direct input to the MPC cost function and define the relative priority of each regulated deviation—temperature (ρ), humidity (λ), lighting/illuminance (φ), CO2 (β), and irrigation flow (ν)—together with the penalty on purchased electricity. Their integration allows the controller to allocate effort where it matters agronomically, rather than pursuing a purely technical balance among loops. Concretely, the optimizer will first suppress temperature and irrigation errors, then humidity excursions, and only thereafter tighten CO2 and artificial-lighting tracking if energy remains available.

Here, the priority structure couples with the anticipative nature of MPC to do more than just track setpoints—it schedules actuations in time to exploit renewable availability and respect crop physiology. This forward-looking characteristic of MPC makes it particularly well-suited for greenhouse climate control, as it enables optimization of control actions based on forecasted environmental conditions. Unlike traditional feedback-based strategies, MPC can anticipate diurnal and weather-related variations such as changes in solar radiation or external temperature and adjust internal conditions proactively. Prior research has demonstrated these advantages: for instance, Aaslyng et al. developed the IntelliGrow system, which employed MPC to optimize heating and lighting by leveraging natural sunlight, significantly reducing energy consumption while maintaining crop productivity [

51]. Similarly, Markvart et al. introduced a multi-objective optimization approach using genetic algorithms (DynaLight) to minimize electricity costs while ensuring adequate lighting levels, prioritizing agronomic needs over purely technical criteria [

52].

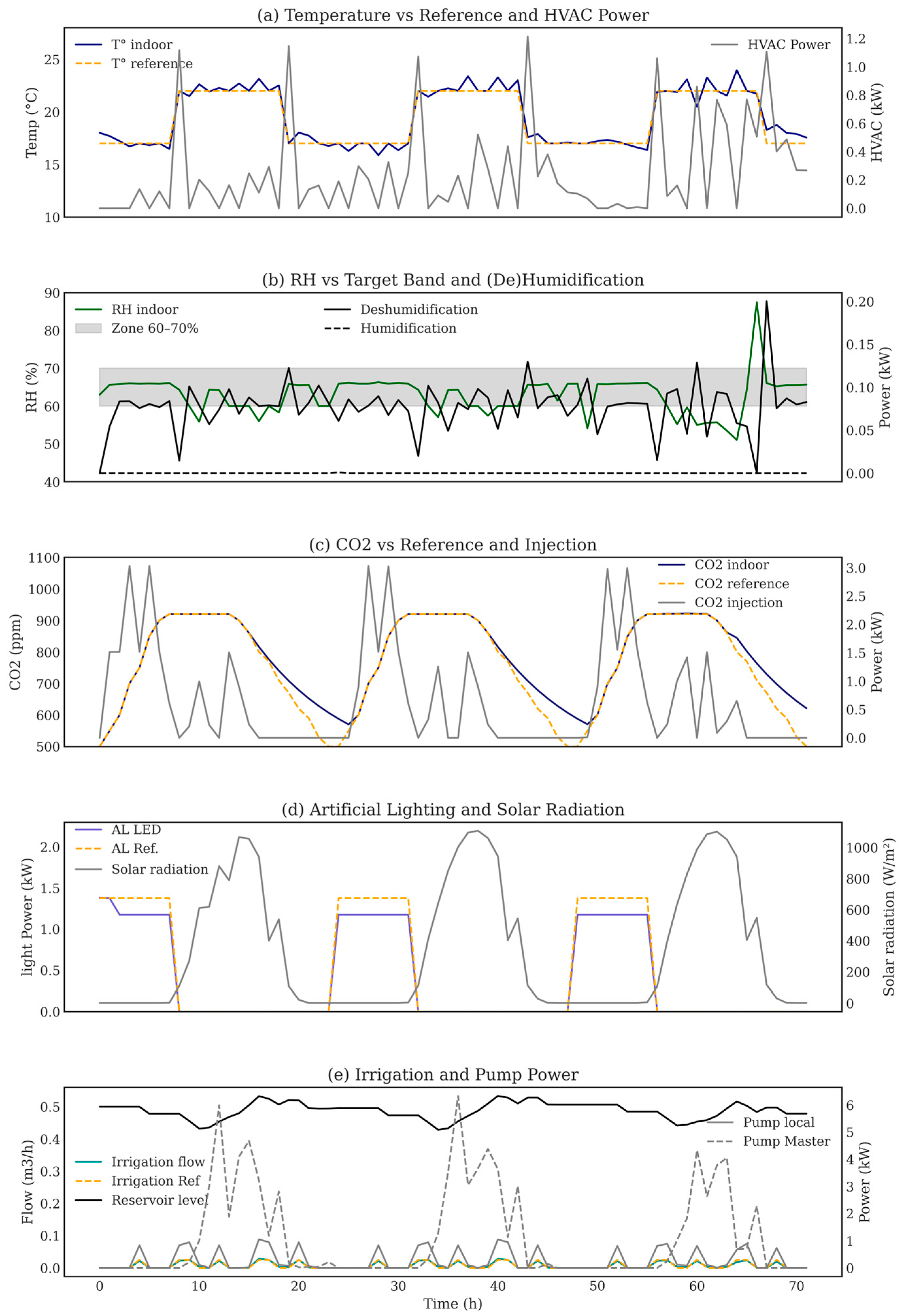

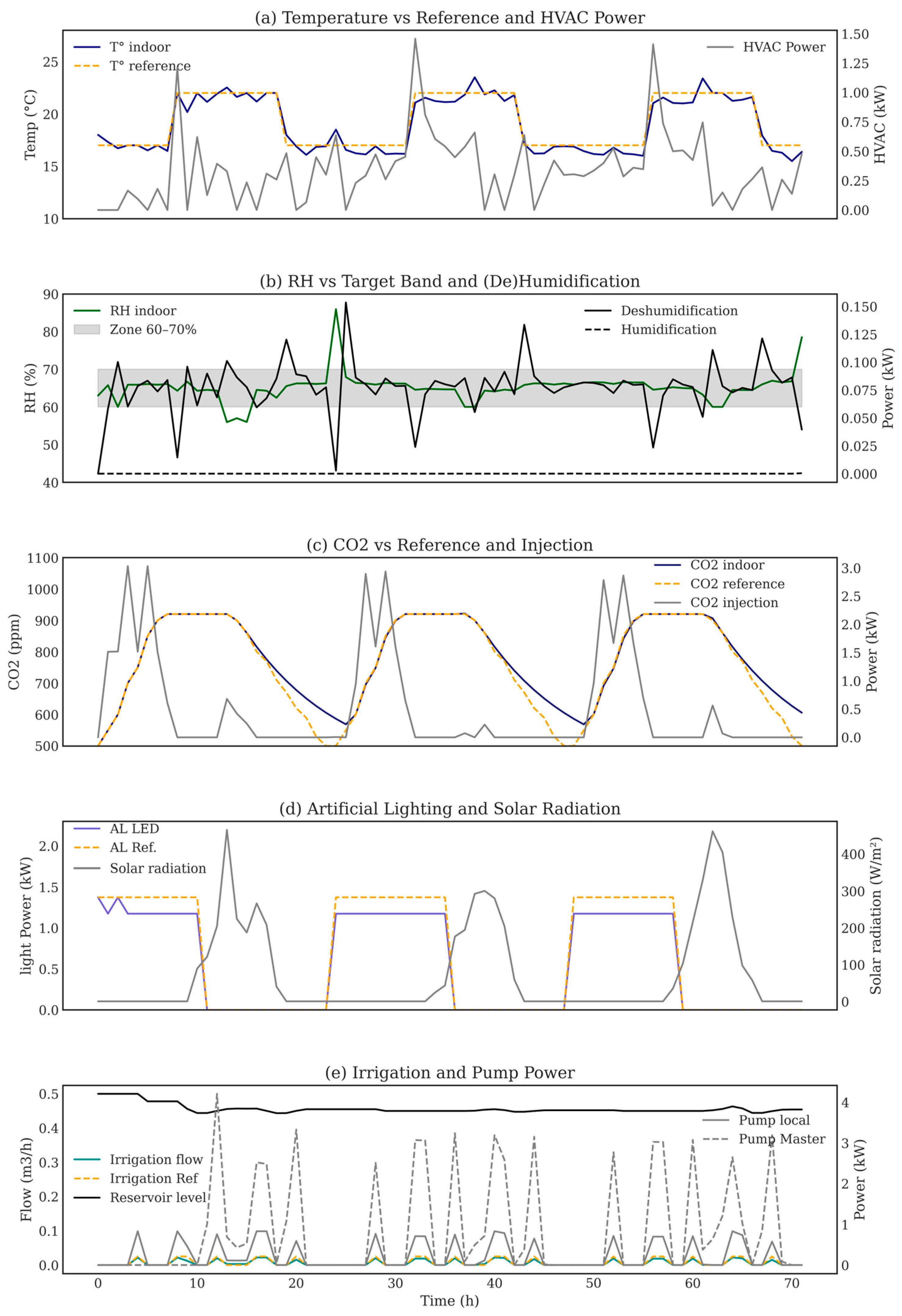

This integration of anticipative optimization with agronomic priorities is exemplified in seasonal control behavior. In June (high-PV) (

Figure 9), the controller not only keeps

Tin close to its day/night targets with short HVAC bursts, but it also shifts energy-intensive tasks into high-irradiance hours. The master irrigation pump is commanded primarily when PV power is abundant, while the local pump delivers fine pulses that track the flow reference. CO

2 dosing is concentrated during bright periods, when photosynthesis is most responsive, and dehumidification operates in brief, targeted pulses to keep RH in the 60–70% band without overshoot. Artificial lighting is used sparingly to top-up the photoperiod: LEDs maintain the prescribed light window and then respect a dark rest period to avoid unnecessary energy use and to align with plant circadian needs.

In December (low-PV) (

Figure 10), the same AHP-weighted MPC protects temperature and water status first (higher-priority terms), while leveraging forecasts for pre-conditioning: the battery is charged ahead of colder intervals, and the master pump is scheduled in the few daylight/PV windows to limit grid dependence. When renewable power is scarce, the controller gracefully relaxes lower-priority loops (slight, time-bounded deviations in CO

2 or illuminance) rather than triggering long, energy-expensive actuation. RH is held near the target by combining predictive ventilation with selective dehumidification; LEDs enforce the photoperiod/rest alternation even if additional electrical energy is available, preventing light stress.

Across both seasons, the AHP-MPC therefore delivers explicit, expert-driven trade-offs plus temporal orchestration: (i) tight tracking of high-priority variables (temperature, irrigation/RH) remains intact; (ii) energy-heavy actuators (master pump, HVAC, LEDs, CO2 injector) are timed to renewable peaks; and (iii) lower-priority objectives are adjusted predictively and briefly to keep the whole microclimate within agronomic bounds with minimal energy cost.

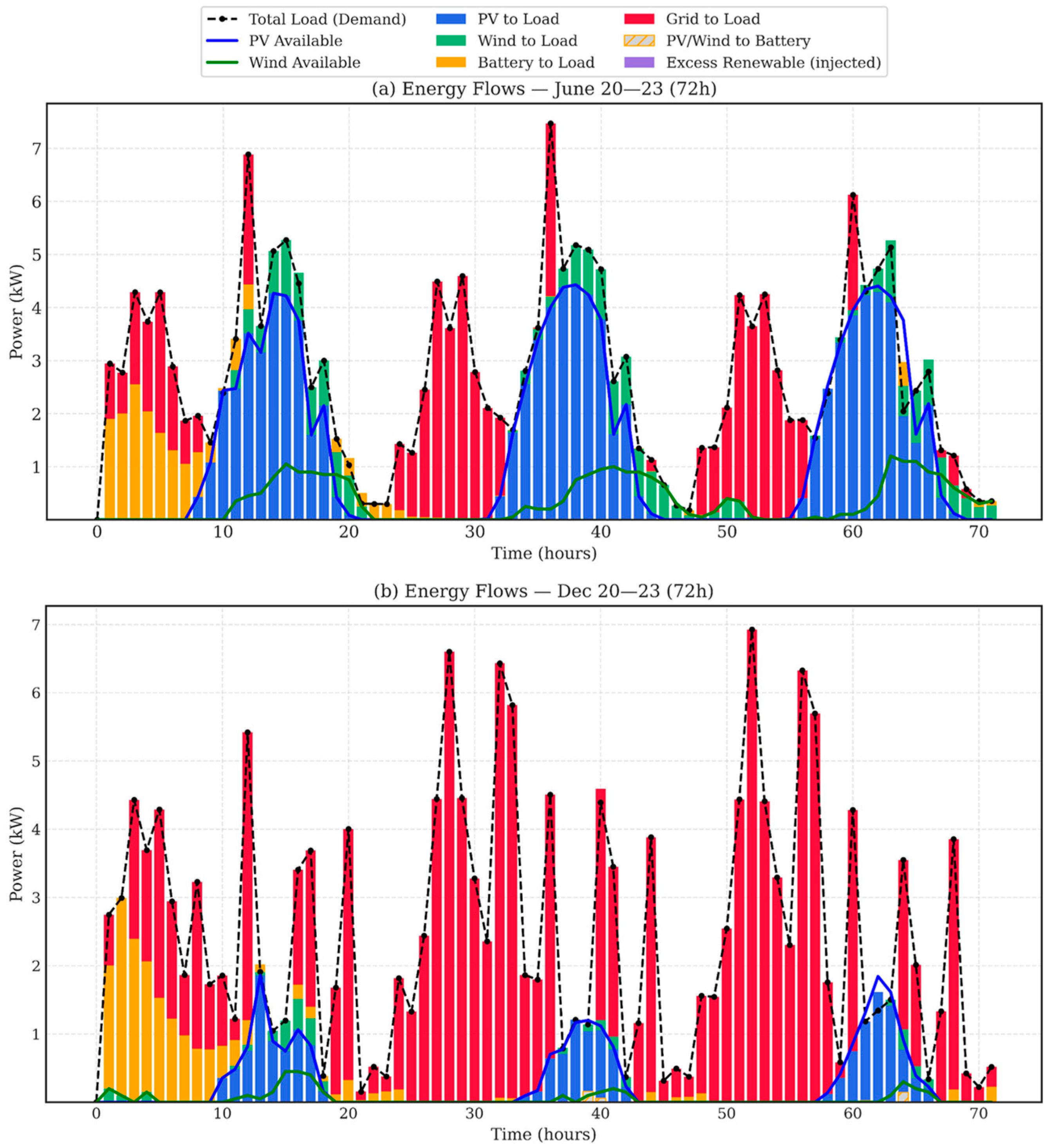

Figure 11 shows how the electrical demand of all greenhouse loads—HVAC, LED lighting, CO

2 injector, humidifier/dehumidifier, and the master/local irrigation pumps—is continuously satisfied by a time-varying mix of sources (PV, wind, battery, grid) orchestrated by the AHP-weighted MPC. At every hour, the controller follows a simple merit order guided by priorities and forecasts: use on-site renewables first, charge the battery when there is surplus, discharge it to cover expected shortfalls, and import from the grid only for the residual deficit. The split visible in the stacked bars depends jointly on (i) renewable availability (PV, wind), (ii) battery state of charge (SOC) and charge/discharge limits, and (iii) the instantaneous load profile driven by climate regulation (HVAC and RH control), photoperiod enforcement (LEDs), CO

2 enrichment, and irrigation scheduling (master pump for filling/reserve transfers, local pump for plot delivery).

Summer (June): Solar peaks create PV output plateaus from late morning to mid-afternoon. The MPC directs most demand to PV Powerbursts at temperature changes, CO2 injection during high-light hours, and local irrigation pumps matching setpoints. Surplus PV charges the battery, which discharges after sunset to reduce grid imports. The energy-intensive master pump is scheduled to run during periods of abundant PV generation. Wind energy contributes occasionally but plays a secondary role. No renewable energy is exported to the grid because all excess generation is allocated to charging the battery, emphasizing local energy storage and consumption.

Winter (December): Reduced solar and wind result in limited renewables and increased heating and lighting demand. The MPC relies more on the grid to maintain temperature and humidity, while charging the battery during brief renewable availability and discharging to smooth peaks. LEDs are heavily used to maintain photoperiod; HVAC dominates heating; humidification is applied selectively. As in summer, no export occurs: renewable surplus is first stored in the battery.

Overall,

Figure 11 illustrates a well-defined, season-aware power-flow policy: renewable energy covers a large share of the summer demand at specific hours (midday PV windows), enabling strategic activation of energy-hungry devices (e.g., master pump aligned with PV peaks); in winter, with low wind and solar potential, the grid carries the larger share, while the battery is managed predictively to buffer variability and protect the most agronomically critical services.

The AHP-weighted MPC maintains reliable climate control across seasons (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). In summer, all variables exhibit low tracking errors; irrigation shows a high SMAPE due to pulsed setpoints, but remains well aligned in absolute terms (

Table 4). In winter, performance slightly declines under renewable energy scarcity: temperature NRMSE increases to 0.14 (SMAPE = 3.05%), humidity remains at 0.19 (8.56%), lighting shows modest deviations (NRMSE = 0.10, SMAPE = 6.97%), and CO

2 is tightly regulated (NRMSE = 0.11, SMAPE = 3.92%). These results reflect the controller’s prioritization scheme, which preserves temperature and water control while permitting bounded relaxations on CO

2 and lighting.

The seasonal energy balance (

Figure 10,

Table 5) explains these results. Over three summer days, total demand is 197.66 kWh, mainly supplied by PV (47.10%) and wind (11.89%), with battery discharge (8.83%) smoothing evening peaks; grid supply accounts for 33.30%, with moderate peak import (4.57 kW). In winter, total demand falls slightly to 181.48 kWh, but renewable availability drops sharply at the Kenitra site (PV 10.92%, wind 1.99%), leading to greater reliance on battery discharge (9.93%) and grid supply (77.48%), with a higher peak import of 6.92 kW. No renewable export occurs in either season, as the MPC prioritizes charging the battery when surplus is present, then uses stored energy for upcoming loads rather than feeding the grid. This strategy of load shifting is mirrored in recent renewable-greenhouse research: Gholami et al. (2025) demonstrated that strategically charging a BESS during high PV output and discharging in the evening can markedly raise on-site autonomy and cut grid imports [

53].

Figure 10 also reveals temporal orchestration: in summer, energy-intensive tasks align with PV peaks—such as master-pump refilling and CO

2 dosing during bright hours—while LEDs provide only supplementary lighting to maintain photoperiod, respecting dark rest periods. Irradiance-aware scheduling of actuators and lighting has long been reported to reduce energy while maintaining crop performance; for example, Aaslyng et al. (2003) describe the IntelliGrow concept that times heating/lighting to natural sunlight availability [

54]. In winter, with minimal wind and low irradiance, the grid covers a larger share to maintain temperature and photoperiod; the battery charges opportunistically during short renewable windows and discharges repeatedly to shave demand peaks. Across seasons, the AHP-MPC meets agronomic targets with expert-driven trade-offs: high-priority variables (temperature, irrigation/humidity) stay within target bands, while lower-priority loops (CO

2, lighting) adjust predictively and briefly under energy scarcity—yielding the KPI profiles shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

6. Conclusions

This work shows that combining expert knowledge with optimization effectively manages greenhouse climate’s multiple objectives. By integrating AHP-derived priorities—ranking temperature, irrigation, humidity, lighting, and CO2 into an MPC—we created a balanced, adaptive control aligned with expert input. A key advance is explicitly handling interactions between climate variables, avoiding conflicts and focusing on what matters most for crops. When resources are limited, the controller maintains temperature and water within limits while allowing brief relaxations on lower-priority factors. The controller maintained high tracking accuracy for critical agronomic variables across two seasonal 72 h episodes (Kenitra, Morocco). Temperature and CO2 were tightly regulated (NRMSE ≤ 0.14; SMAPE ≤ 4%), while humidity, lighting, and irrigation remained within acceptable bounds despite variable references and pulsed setpoints.

On the energy side, the system intelligently synchronized energy-intensive actions with local renewable availability. In summer, 59.99% of the total demand (197.66 kWh) was met by PV, wind, and battery, limiting peak grid import to 4.57 kW. In winter, local sources covered 22.84% of 181.48 kWh demand, with controlled peak grid use at 6.92 kW. No renewable energy was exported; instead, surplus was stored and strategically dispatched to support agronomic priorities. Seasonal tests confirm it optimizes energy use by aligning heavy tasks with solar peaks in summer and protecting critical functions with battery and grid support in winter.

Our intent here was to isolate the value of weighting and orchestration; accordingly, the prediction engine feeding the MPC was kept generic. Future work will benchmark statistical, machine-learning and hybrid forecasters and quantify their impact on closed-loop performance [

55]; extend experiments to the full tomato production cycle (≈3–4 months); deploy real-time implementations with IoT sensing; and investigate adaptive re-weighting across phenological stages, price-responsive operation, and coordination of multiple greenhouses within a renewable microgrid.

Overall, integrating survey-based priorities into a predictive, anticipatory controller offers a practical path to knowledge-driven, resource-aware greenhouse operation—capable of maintaining agronomic quality while intelligently arbitraging scarce energy and water.