Operational Smart Charging and Its Environmental Impacts: Evidence from Three EU Use Cases with an Innovative LCA Tool, VERIFY-EV

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. The VERIFY-EV Platform: Methodology and Implementation

3.1. Overview of the VERIFY Platform

3.2. Key Performance Indicators

3.3. Component Libraries and Databases

3.4. Analysis Algorithms

3.4.1. Battery Primary Energy and Emission Factor Estimations

- and are the cumulative charges at time-step that the EV chargers provided over the previous 96 h, stemming from their RES and the grid, respectively.

- are the cumulative GHG emissions from the charge provided from RES, over the last 92 h, and are derived by the following equation:

- is the emission factor of the RES under examination.

- are the cumulative GHG emissions from the charge provided by the grid over the last 96 h and are derived by the following equation:

- is the cumulative primary energy stemming from the charge provided by RES over the last 96 h and is derived by the following equation:

- is the primary energy factor of the RES under examination.

- is the cumulative primary energy stemming from the charge provided by the grid over the last 96 h and is derived by the following equation:

3.4.2. VERIFY-EV KPI Formulas

- The GHG savings from EV driving are determined by comparing the performance of the EV with its conventional equivalent, yielding two KPIs:

- The GHG emission savings, at each time-step, , derived by the following equation:

- The primary energy savings, at each time-step, n, derived by the following equation:

where- is the energy consumed for driving the same distance in a conventional fuel equivalent vehicle, and

- and are the emission and primary energy factors of the fuel consumed by the conventional fuel vehicle.

- The savings generated from EV charging using dedicated RES.

- The GHG emission savings,, at each time-step, , derived by the following equation:

- The primary energy savings, at each time-step, n, derived by the following equation:

- The savings due to V2X technology

- The GHG emission savings, at each time-step, , derived by the following equation:

- The primary energy savings, at each time-step, n, derived by the following equation:

- : GHG emissions per kilometer due to EV driving

- : Electricity GHG emission factor stemming from the country’s energy mix

- Ie: lifecycle GHG emissions that are not included in the operation phase of the system (e.g., for manufacturing, transportation, installation, etc.).

- Es,a: kgCO2eq saved annually due to EV use.

3.4.3. Time-Series Data

3.4.4. Evaluation of Counter-Congestion Strategies

4. Use Case Description

4.1. Overview of Three Use Cases in the Netherlands, Norway, and Hungary

4.2. Utrecht: Large-Scale Bidirectional Charging Ecosystem

Data Processing and Country-Specific Energy Mix Evaluation for Utrecht Use Case

- is the hourly total charge provided by the chargers at time-step i,

- is the hourly discharge exported to the grid and

- is the total hourly distance traveled by the EVs at time-step, i.

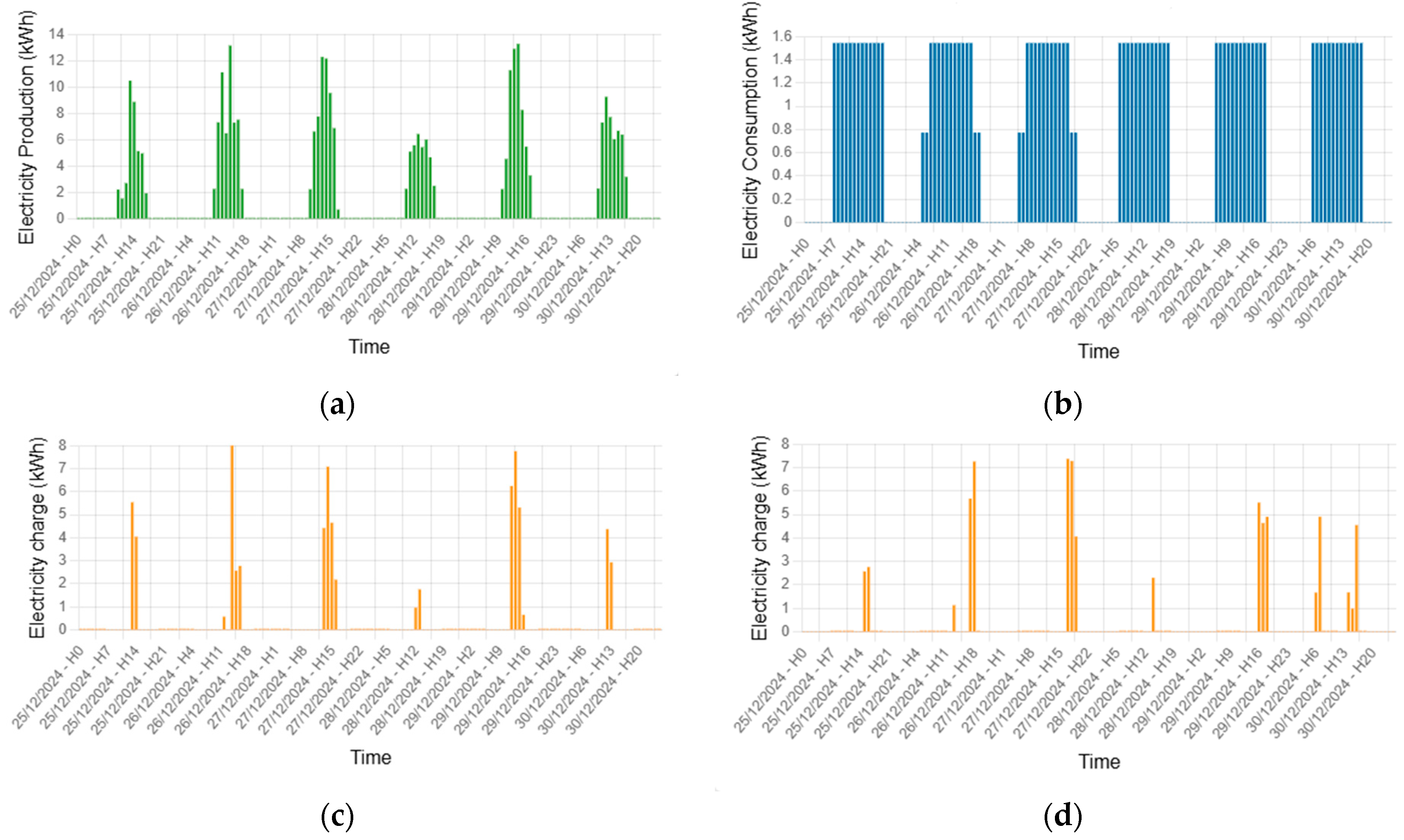

4.3. Oslo: Renewable-Integrated Charging Plaza

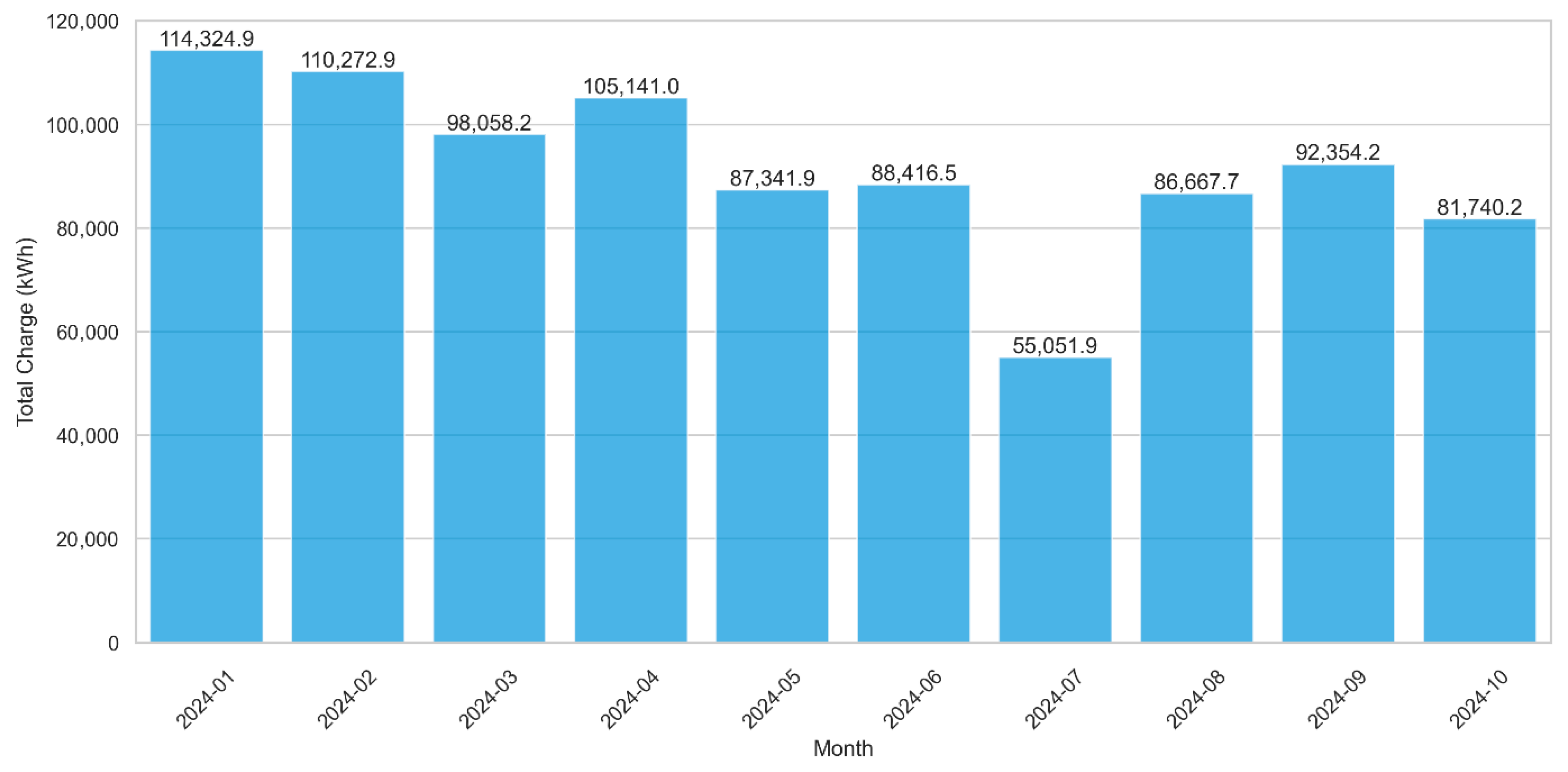

Data Processing and Country-Specific Energy Mix Evaluation for Oslo Use Case

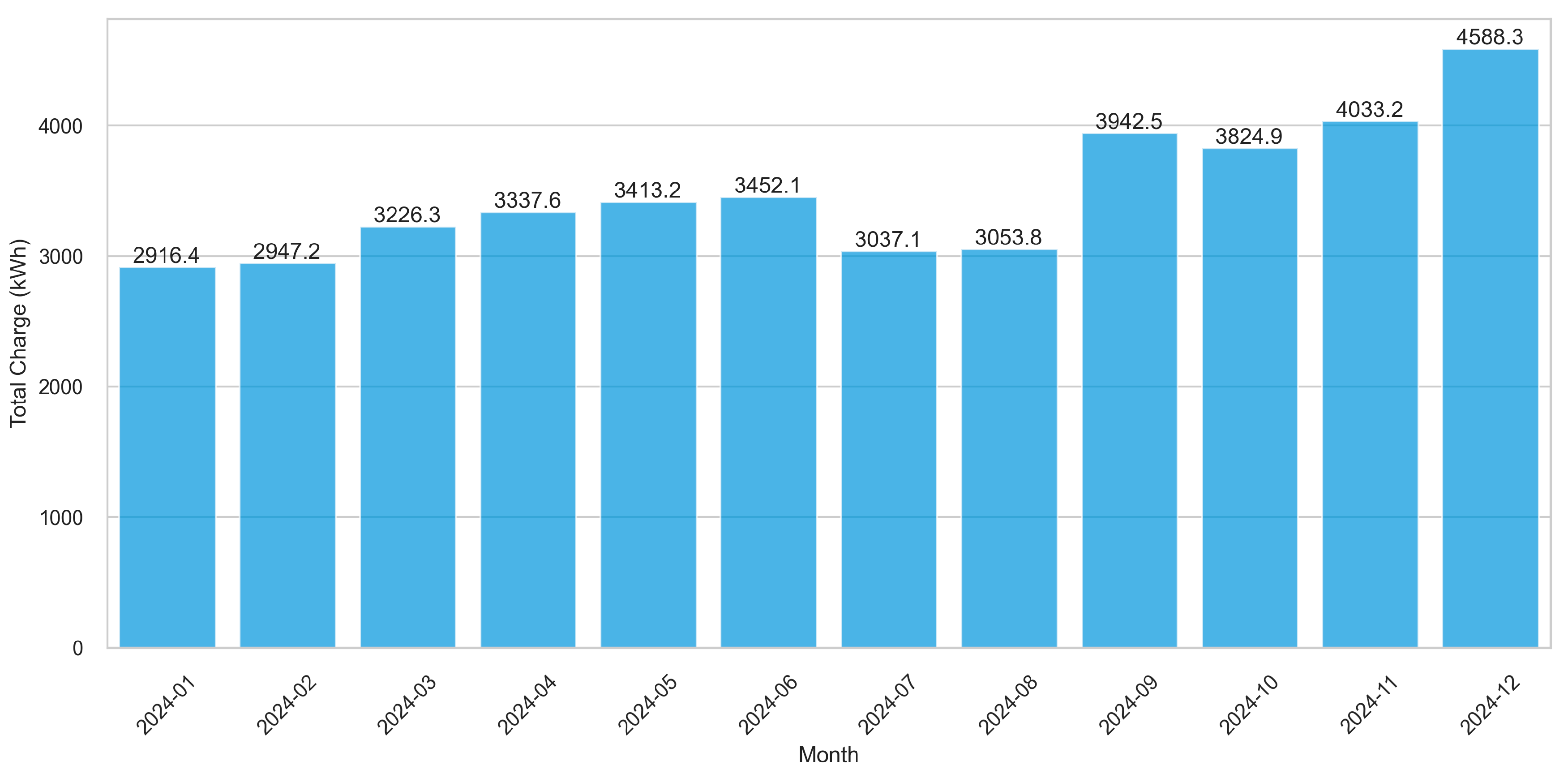

4.4. Budapest: Renewable Integration and Energy Communities

Data Processing and Country-Specific Energy Mix Evaluation for Budapest Use Case

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Overview of Environmental Assessment Results

5.2. Utrecht Use Case Results

5.3. Oslo Use Case Results

5.4. Budapest Use Case Results

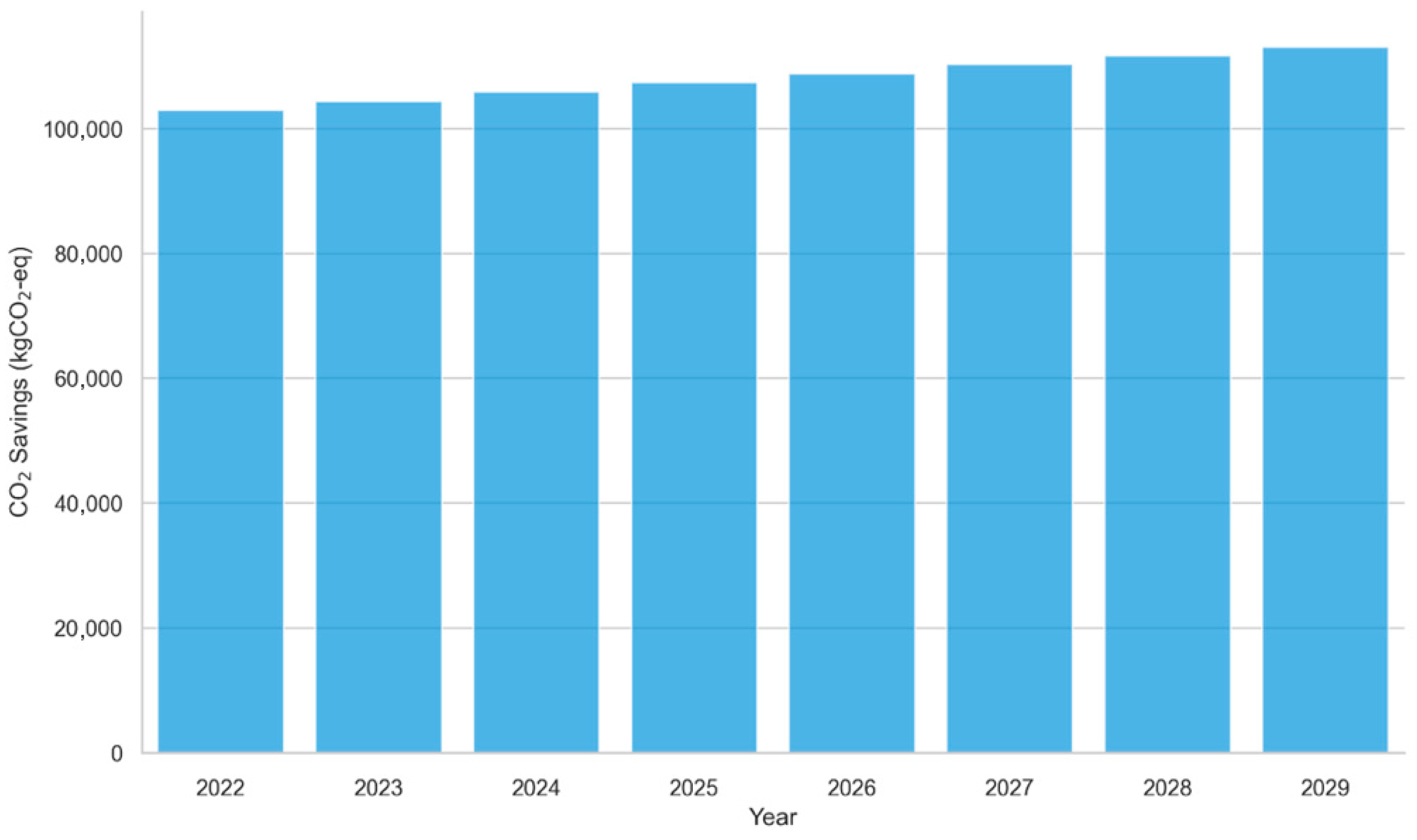

5.5. Carbon Payback Time (CPBT) Results

5.6. Cross-Site Comparative Insights

5.7. Limitations and Future Research Needs

6. Conclusions

- Target high-utilization nodes. Public support should concentrate on connectors with credible, high-energy throughput so that CPBT falls within battery life. Funding prospects can operationalize this via ex-ante utilization plans (routes, duty cycles) and ex-post hourly reporting of delivered energy, with minimum throughput (or CPBT) thresholds tied to continued support.

- Advance grid decarbonization and EV roll-out in tandem. As marginal grid carbon intensity declines, operational emissions fall, and CPBT shortens. Programs should enable location- and time-aware siting and dispatch, promote on-site renewables or a guarantee of origin, and coordinate with DSOs to relieve local constraints that otherwise shift charging to dirtier hours

- Make smart charging the default and stage V2G. Require emissions-aware, dynamic-tariff control as baseline operation to capture most benefits at low complexity and to build the data/control layer needed for flexibility markets. Where V2G is pursued, adopt staged deployment with minimum state-of-charge guarantees, degradation-aware scheduling, performance warranties, and interoperability requirements so flexibility does not compromise battery longevity or user needs.

- Require evidence-based monitoring. Mandate LCA-consistent monitoring at supported sites—hourly energy flows, grid intensity factors, utilization metrics, and CPBT—to align public spending with measured climate performance and enable continuous optimization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| CPBT | Carbon Payback Time |

| DSO | Distribution System Operator |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gases |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engine |

| LCA | Lifecycle Assessment |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| TLA | Three-letter acronym |

| Nomenclature | |

| Symbol | Meaning |

| n | Time-step |

| Cumulative energy from the grid, at time-step, , | |

| Cumulative renewable energy, at time-step, , | |

| Cumulative GHG emissions from the charge with energy provided from RES | |

| Cumulative GHG emissions from the charge with energy provided from the Grid | |

| ER(n) | Energy supplied by the charger from on-site RES, at step, n |

| EG(n) | Energy supplied by the charger from the grid, at step, n |

| EFR | Emission factor of electricity provided by RES |

| EFG(n) | Emission factor of grid electricity, at step n |

| EFB(n) | Emission factor of battery-stored energy mix, at step n |

| PEFR | Primary energy factor of electricity from RES |

| PEFG(n) | Primary energy factor of electricity from the grid, at step n |

| Cumulative primary energy from renewables, at step n | |

| Cumulative primary energy from the grid, at step n | |

| PEFB(n) | Primary energy factor of battery mix, at step n |

| GHG emission savings, at step, | |

| Primary Energy savings, at step n | |

| EFF(n) | Energy consumed by ICEV for same distance traveled by the EV, at step n |

| EFFF | Emission factor of the fuel consumed by the conventional fuel vehicle |

| PEFFF | Primary energy factor of the fuel consumed by the conventional fuel vehicle |

| GHG emission savings, at step n, calculated as the difference between emissions from charging solely from the grid and from charging solely from RES | |

| Primary energy savings, at step n, calculated as the difference between n energy from charging solely from the grid and from charging solely from RES | |

| GHG emission savings, at step n, calculated by comparing the emissions from using energy discharged from EV batteries with those from importing an equivalent amount of energy from the grid. | |

| Primary Energy savings, at step n, calculated by comparing the primary energy discharged from EV batteries with the primary energy from importing an equivalent amount of primary energy from the grid. | |

| D(n) | EV battery discharge exported at step n |

| GHG emissions per kilometer due to EV driving | |

| : | Electricity GHG emission factor based on the country’s electricity generation mix |

| Carbon Payback Time | |

| Ie: | Lifecycle GHG emissions that are not included in the operation phase of the system |

| Es,a | kgCO2eq saved annually due to EV use. |

References

- The European Green Deal—European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Das, P.K.; Bhat, M.Y.; Sajith, S. Life Cycle Assessment of Electric Vehicles: A Systematic Review of Literature. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, M.; Neugebauer, J. Cumulative Emissions of CO2 for Electric and Combustion Cars. A Case Study on Specific Models. Energies 2022, 15, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Koroma, M.S.; Broadbent, A.; Wood, D. Life Cycle Assessment of Battery Electric Vehicles: Implications of future electricity mix and different battery end-of-life management. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, D.; Pechancová, V.; Saha, N.; Pavelková, D.; Saha, N.; Motiei, M.; Jamatia, T.; Chaudhuri, M.; Ivanichenko, A.; Venher, M.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Based Batteries: Review of Sustainability Dimensions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 206, 114860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Salzinger, M.; Remppis, S.; Schober, B.; Held, M.; Graf, R. Reducing the Environmental Impacts of Electric Vehicles and Electricity Supply: How Hourly Defined Life Cycle Assessment and Smart Charging Can Contribute. World Electr. Veh. J. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhao, X. Rethinking Electric Vehicle Smart Charging and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Renewable Energy Growth, Fuel Switching, and Efficiency Improvement. Appl. Energy 2024, 361, 122904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCALE. Available online: https://scale-horizon.eu/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Angelakoglou, K.; Lampropoulos, I.; Chatzigeorgiou, E.; Giourka, P.; Martinopoulos, G.; Skembris, A.-S.; Seitaridis, A.; Kousovista, G.; Nikolopoulos, N. Advancing Energy-Efficient Renovation Through Dynamic Life Cycle Assessment and Costing: Insights and Experiences from VERIFY Tool Deployment. Energies 2025, 18, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Du, Y. Smart Charging Strategy for Electric Vehicles Based on Marginal Emission Factors and Time-of-Use Pricing. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Cockerill, T.T.; Pimm, A.J.; Yuan, X. Reducing the life cycle environmental impact of electric vehicles through emissions-responsive charging. iScience 2021, 24, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlschlager, D.; Kigle, S.; Schindler, V.; Neitz-Regett, A.; Fröhling, M. Environmental Effects of Vehicle-to-Grid Charging in Future Energy Systems—A Prospective Life Cycle Assessment. Appl. Energy 2024, 370, 123618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Dou, H.; Hao, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, F.; Hao, H. Additional Emissions of Vehicle-to-Grid Technology Considering China’s Geographical Heterogeneity. Carbon Footpr. 2025, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preis, V.; Mauser, I.; Koller, J.; Kühn, R. Assessing the Incorporation of Battery Degradation in Vehicle-to-Grid Optimization Models: A Review. Energy Inform. 2023, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagaria, S.; Van Der Kam, M.; Boström, T. Vehicle-to-Grid Impact on Battery Degradation and Estimation of V2G Economic Compensation. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Sun, X.; Wolfram, P.; Zhao, S.; Tang, X.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zheng, X. Hidden delays of climate mitigation benefits in the race for electric vehicle deployment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltohamy, H.; Van Oers, L.; Lindholm, J.; Raugei, M.; Lokesh, K.; Baars, J.; Husmann, J.; Hill, N.; Istrate, R.; Jose, D.; et al. Review of Current Practices of Life Cycle Assessment in Electric Mobility: A First Step towards Method Harmonization. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, N.; Nasri, S.; Mnassri, A.; Lashab, A.; Vasquez, J.C.; Cherif, A.; Rezk, H. Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure: Impacts and Future Challenges of Photovoltaic Integration with Examples from a Tunisian Case. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussan, M.; Neirotti, F. Cross-Country Comparison of Hourly Electricity Mixes for EV Charging Profiles. Energies 2020, 13, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousovista, G.; Iakovides, G.; Petridis, S.; Chairopoulos, N.-C.; Skembris, A.; Fotopoulou, M.; Antipa, D.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Rakopoulos, D. Comparative Lifecycle Assessment of Renewable Energy Investments in Public Buildings: A Case Study of an Austrian Kindergarten Under Atypical Operational Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Bachoumis, A.; Skopetou, N.; Mylonas, C.; Tagkoulis, N.; Iliadis, P.; Mamounakis, I.; Nikolopoulos, N. Integrated Methodology for Community-Oriented Energy Investments: Architecture, Implementation, and Assessment for the Case of Nisyros Island. Energies 2023, 16, 6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. ISO, International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Level(s)-Green Forum-European Commission. Available online: https://green-forum.ec.europa.eu/green-business/levels_en (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- ISO 16745-1:2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/69969.html (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- SCALE-D3.2-Use Case Evaluation Report. Available online: https://Scale-Horizon.Eu/?Jet_download=6418 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Sanchez, D.A.; Torres, S.P.; Chillogalli, J.E.; Chamorro, H.R.; Gonzalez, L.G.; Sood, V.K.; Romero, R.R. Optimal Planning of Electric Vehicles Energy Exchange in Parking Lots Considering Uncertainties. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe 2022), Novi Sad, Serbia, 10–12 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- EV Database. Available online: https://ev-database.org/cheatsheet/energy-consumption-electric-car (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- CO2 Emissions Per kWh in Norway-Nowtricity. Available online: https://www.nowtricity.com/country/norway/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Demirci, S.M.; Tercan, U.; Cali, U.; Nakir, I. A Comprehensive Data Analysis of Electric Vehicle User Behaviors Toward Unlocking Vehicle-to-Grid Potential. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9149–9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabr, O.; Ayaz, F.; Nekovee, M.; Saeed, N. Forecasting Infrastructure Needs, Environmental Impacts, and Dynamic Pricing for Electric Vehicle Charging. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall Foot Traffic Statistics Statistics: ZipDo Education Reports 2025. Available online: https://zipdo.co/mall-foot-traffic-statistics/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Alaee, P.; Bems, J.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. A Review of the Latest Trends in Technical and Economic Aspects of EV Charging Management. Energies 2023, 16, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiers, J.; Frey, G. A Case Study of the Use of Smart EV Charging for Peak Shaving in Local Area Grids. Energies 2024, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, E.; Iliadis, P.; Papalexis, C.; Rotas, R.; Mamounakis, I.; Sougkakis, V.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Kosmatopoulos, E. Holistic Renovation of a Multi-Family Building in Greece Based on Dynamic Simulation Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 381, 135202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Long Does an Electric Car Battery Last? Eissenergy. EV Connect. Available online: https://www.evconnect.com/blog/how-long-does-an-electric-car-battery-last/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Albatayneh, A.; Assaf, M.N.; Alterman, D.; Jaradat, M. Comparison of the Overall Energy Efficiency for Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles and Electric Vehicles. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2020, 24, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Guevara, Ó.S.; Huertas, J.I.; Giraldo, M. Real Energy Efficiency of Road Vehicles. Energies 2025, 18, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S. Unit Process Inventory Data for Residential Electric Vehicle Charger Life Cycle Assessment. Available online: https://research.chalmers.se/publication/541061/file/541061_Fulltext.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kukreja, B. Life Cycle Analysis of Electric Vehicles. Available online: https://sustain.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/2018-63%20Lifecycle%20Analysis%20of%20Electric%20Vehicles_Kukreja.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Argue, C. How Long Do Electric Car Batteries Last? What Analyzing 10,000 EVs Tells Us…. Geotab Blog 2025. Available online: https://www.geotab.com/au/blog/ev-battery-health/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Yang, F.; Xie, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, C. Predictive modeling of battery degradation and greenhouse gas emissions from U.S. state-level electric vehicle operation. Nature Commun. 2018, 9, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Symbol | Functional Unit |

|---|---|---|

| GHG savings due to EV driving | kgCO2-eq | |

| Primary energy savings due to EV driving | kWh | |

| GHG savings due to RES charging | kgCO2-eq | |

| Primary energy savings due to RES charging | kWh | |

| GHG savings due to V2G | kgCO2-eq | |

| Primary energy savings due to V2G | kWh | |

| GHG emissions per kilometer | kgCO2-eq/km | |

| Carbon payback time | years |

| Location | Primary Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Utrecht, The Netherlands | Bidirectional ecosystem via V2G | Large-scale V2G living laboratory |

| Oslo, Norway | V1G charging application | Clean energy mix |

| Budapest, Hungary | Charging combined with PV and stationary storage at a large-scale shopping center | Energy community integration |

| Performance Indicator | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Total Primary Energy Savings | 1,344,246 | kWh |

| Total GHG Emissions Savings | 880,250 | kgCO2-eq |

| Primary Energy Savings per km | 0.215 | kWh/km |

| GHG Emissions Savings per km | 0.138 | kgCO2-eq/km |

| Annual GHG Savings from V2G | 1950 | kgCO2-eq/year |

| GHG Reduction vs. ICEV | 80.35 | % |

| Primary Energy Reduction vs. ICEV | 34.50 | % |

| Performance Indicator | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Total Primary Energy Savings | 12,206,631 | kWh |

| Total GHG Emissions Savings | 9,701,621 | kgCO2-eq |

| EV GHG Emissions per km | 0.002 | kgCO2-eq/km |

| GHG Reduction vs. ICEV | 99.0 | % |

| Primary Energy Reduction vs. ICEV | 35.0 | % |

| Performance Indicator | Scenario | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Total Primary Energy Savings (kWh) | Original | 296,324 |

| Weekend Increase | 297,007 | |

| PV Coupling | 297,204 | |

| Total GHG Emissions Savings (kgCO2-eq) | Original | 277,714 |

| Weekend Increase | 278,766 | |

| PV Coupling | 285,806 | |

| EV GHG Emissions per km ( kgCO2-eq /km) | Original | 0.034 |

| Weekend Increase | 0.033 | |

| PV Coupling | 0.03 | |

| GHG Reduction vs. ICEV (%) | Original | 80.34 |

| Weekend Increase | 80.92 | |

| PV Coupling | 82.66 | |

| Primary Energy Reduction vs. ICEV (%) | Original | 23.79 |

| Weekend Increase | 23.79 | |

| PV Coupling | 23.79 |

| Use Case | V2G Implementation | Charging Hours Optimization | RES Integration on Chargers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Utrecht | X | - | - |

| Oslo | - | X | X |

| Budapest | - | - | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giourka, P.; Petridis, S.; Seitaridis, A.; Angelakoglou, K.; Martinopoulos, G.; Kosmatopoulos, E.; Nikolopoulos, N. Operational Smart Charging and Its Environmental Impacts: Evidence from Three EU Use Cases with an Innovative LCA Tool, VERIFY-EV. Energies 2025, 18, 6215. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236215

Giourka P, Petridis S, Seitaridis A, Angelakoglou K, Martinopoulos G, Kosmatopoulos E, Nikolopoulos N. Operational Smart Charging and Its Environmental Impacts: Evidence from Three EU Use Cases with an Innovative LCA Tool, VERIFY-EV. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6215. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236215

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiourka, Paraskevi, Stefanos Petridis, Andreas Seitaridis, Komninos Angelakoglou, Georgios Martinopoulos, Elias Kosmatopoulos, and Nikolaos Nikolopoulos. 2025. "Operational Smart Charging and Its Environmental Impacts: Evidence from Three EU Use Cases with an Innovative LCA Tool, VERIFY-EV" Energies 18, no. 23: 6215. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236215

APA StyleGiourka, P., Petridis, S., Seitaridis, A., Angelakoglou, K., Martinopoulos, G., Kosmatopoulos, E., & Nikolopoulos, N. (2025). Operational Smart Charging and Its Environmental Impacts: Evidence from Three EU Use Cases with an Innovative LCA Tool, VERIFY-EV. Energies, 18(23), 6215. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236215