Log-Log Pressure Curve–Based Analysis and Evaluation of Shale Gas Stimulation: A Case Study from Block X, Sichuan Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

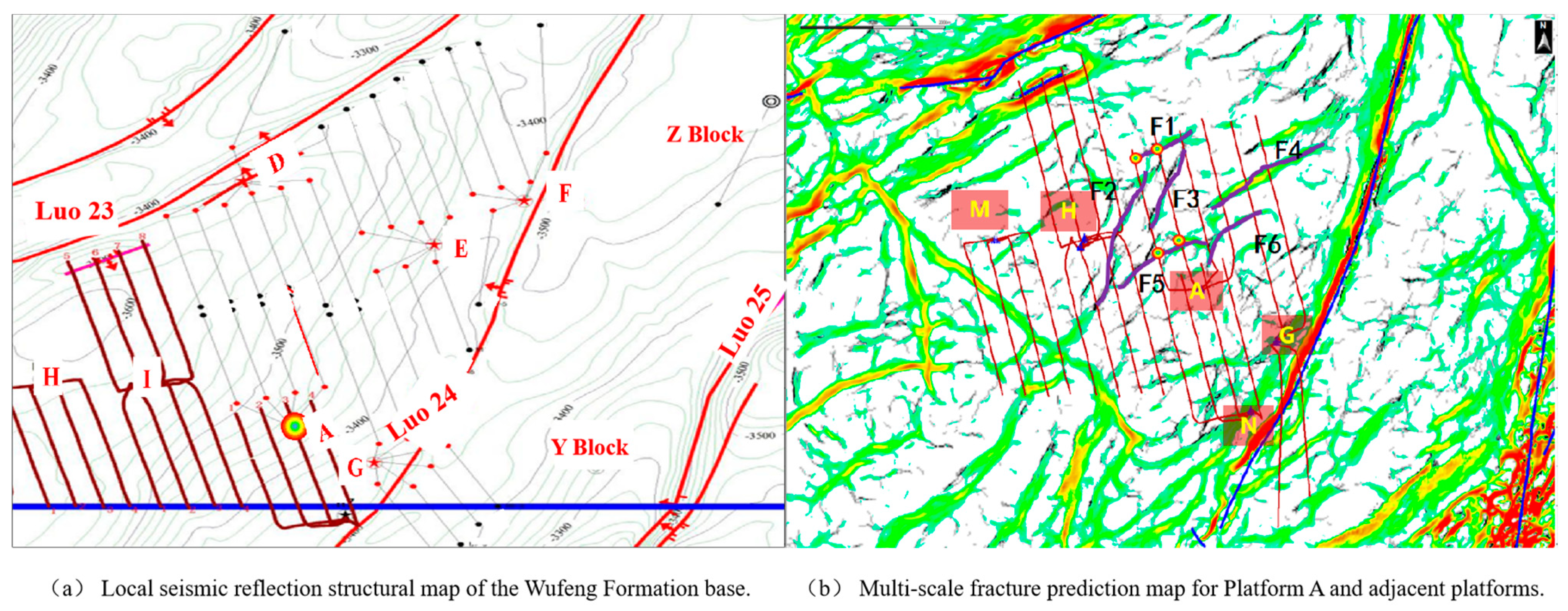

2. Geological Overview of the Study Block

3. Research Methods

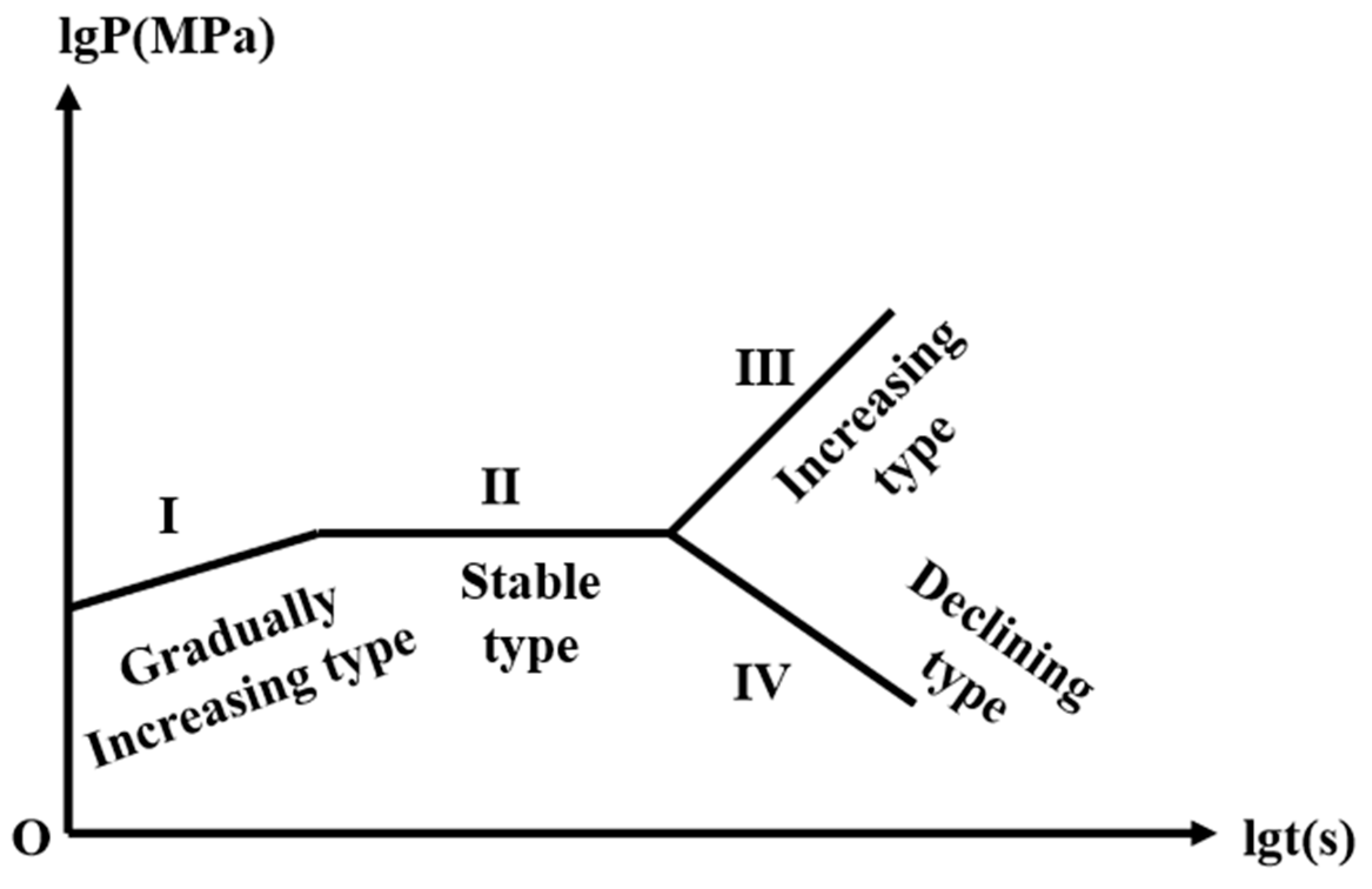

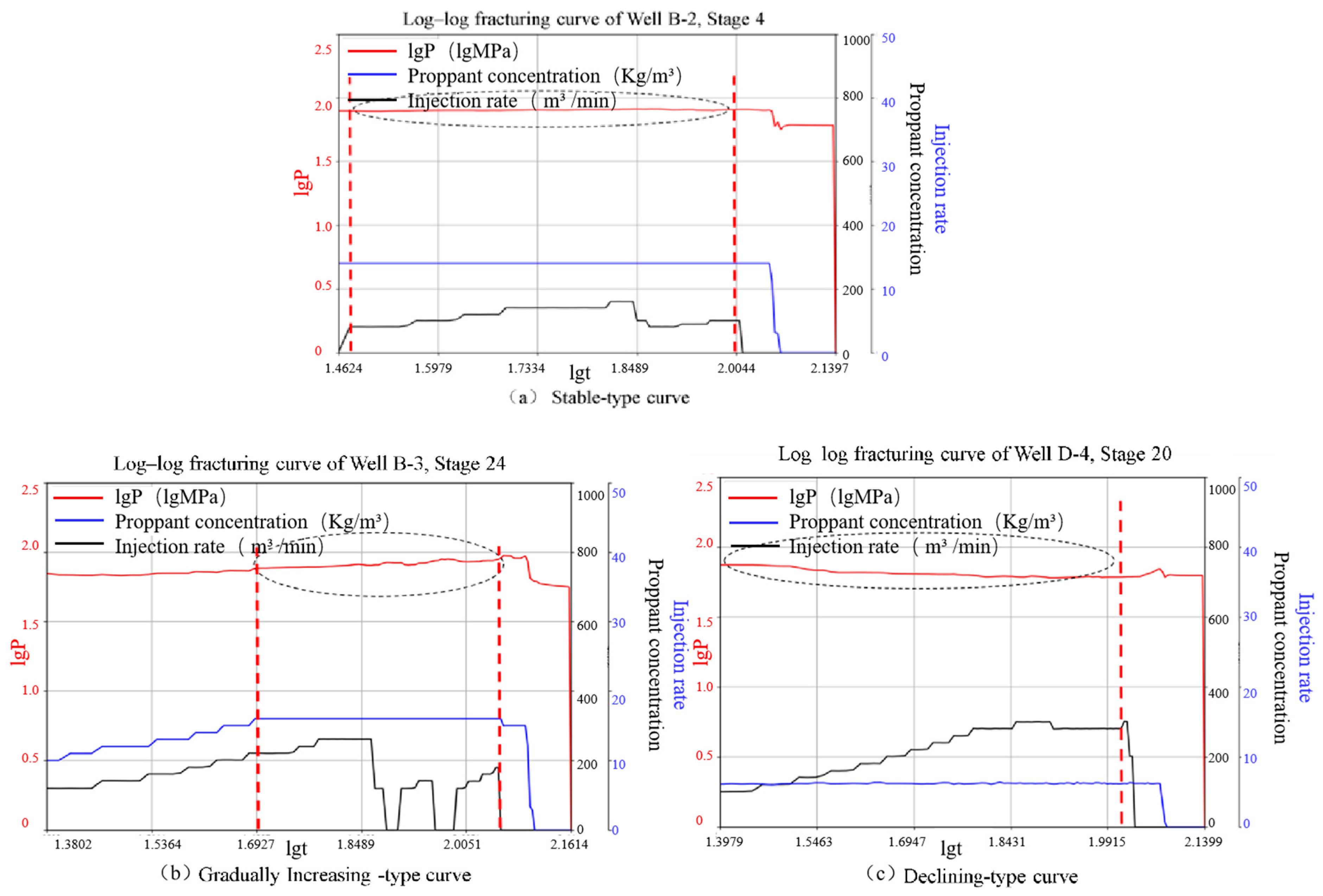

3.1. Log P–Log t Diagnostic Curve Analysis

- Curve I: A log P–log t slope with a low positive value corresponds to the PKN model, indicating that fracture height growth is restricted while fracture length extends gradually. Under ideal, leakoff-controlled conditions, the PKN model predicts a time-dependent pressure slope of 1/4 power, whereas the KGD model predicts a slope between 1/4 and 1/3. Therefore, a slope of approximately 0.2–0.3 theoretically reflects a planar fracture propagation pattern constrained vertically by impermeable layers.

- Curve II: A slope near zero suggests the opening of natural microfractures or initiation of new fractures, which increases fluid leakoff until the leakoff rate balances the injection rate. This pattern is a characteristic indicator of a complex fracture network activation, consistent with a leakoff-dominated fracture propagation regime.

- Curve III: A slope of approximately 1 occurs when fracture propagation ceases due to near-wellbore bridging, proppant screenout, or severe stress shadow effects. The fracture cavity then behaves as a fixed volume, and pressure becomes directly proportional to injection time, meaning the pressure increment scales with injected fluid volume. This corresponds to the fracture cavity filling model, indicating severe proppant blockage or effective tip screenout within the fracture.

- Curve IV: A negative slope indicates that as the fracture propagates into a low-stress layer, the resistance decreases and the fracture accelerates into that interval, resulting in pressure decline. Vertical fracture growth or intersection with natural fractures may also lead to pressure release. This deviation from classical planar fracture models marks a transition in the fracture propagation regime, which can be explained by the pseudo-three-dimensional (P3D) model exhibiting uncontrolled fracture height growth or by the complex fracture network model involving large-scale natural fracture connectivity.

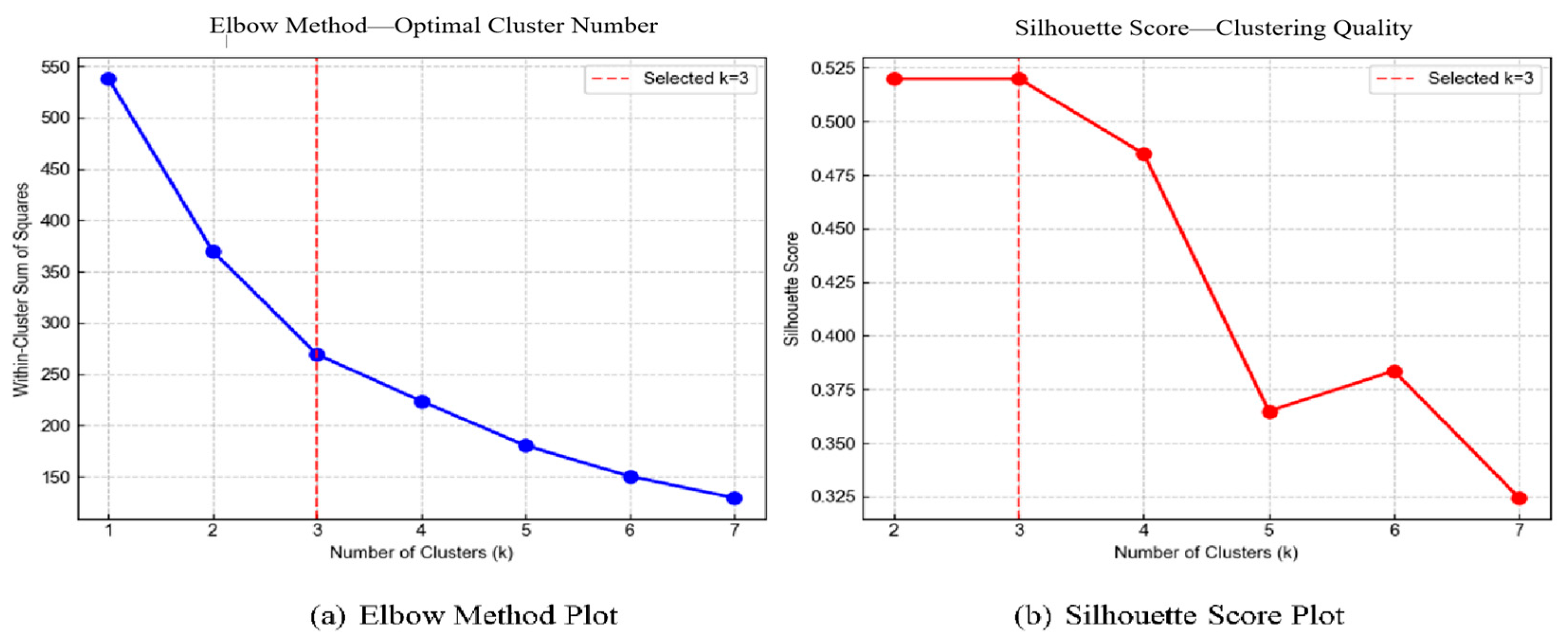

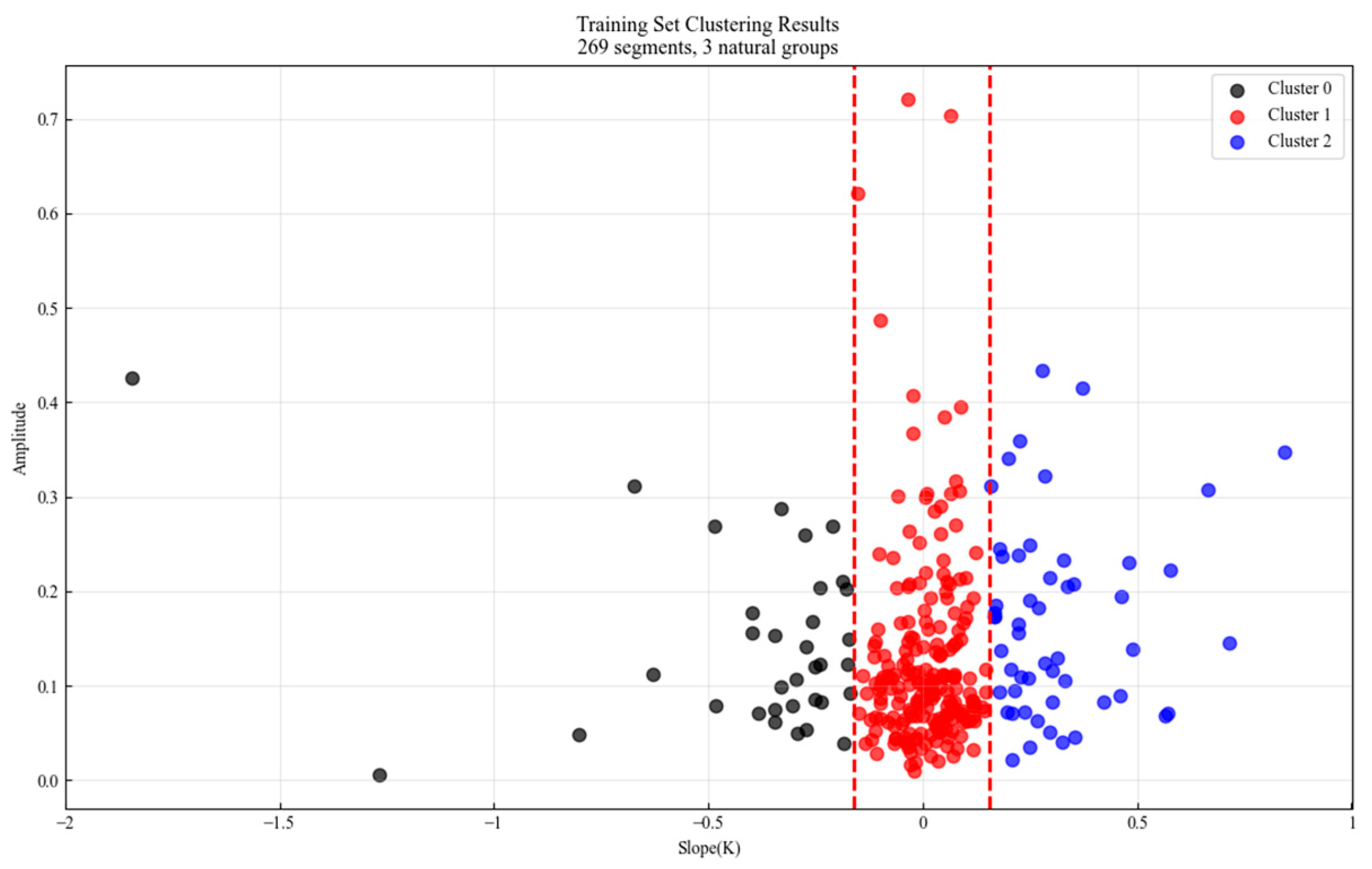

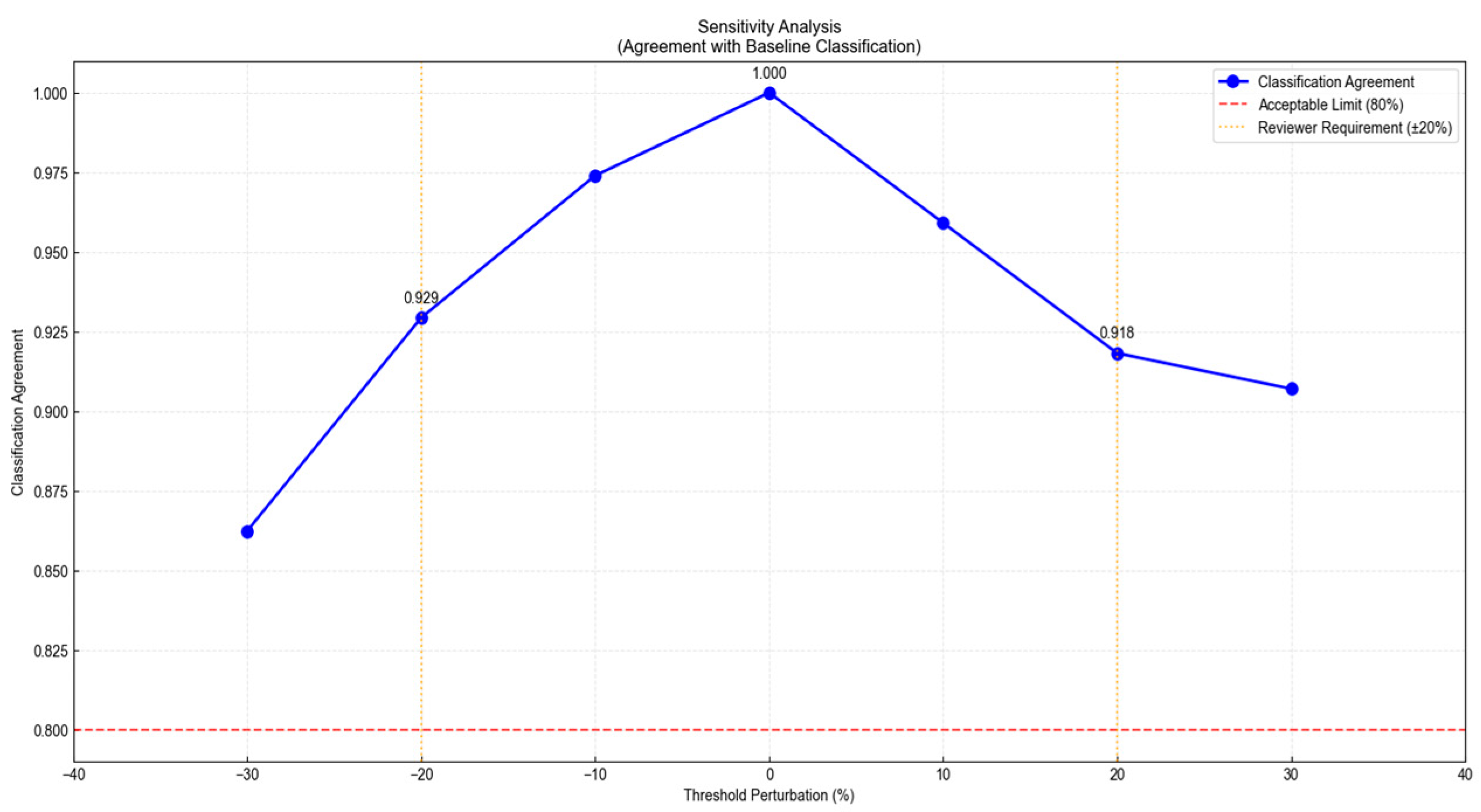

3.2. Threshold Classification of Log–Log Curve Types

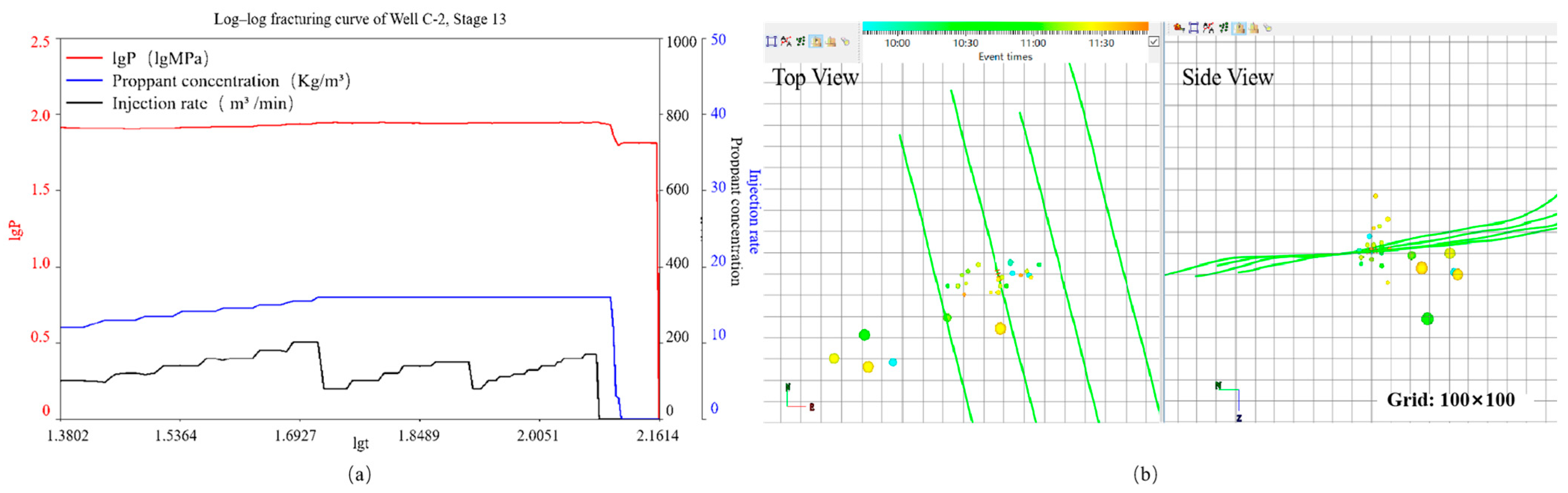

3.3. Verification of the Log–Log Method Using Cross-Microseismic Monitoring Results

4. Fracturing Diagnostic Results and Applications

4.1. Distribution Characteristics of Curve Types

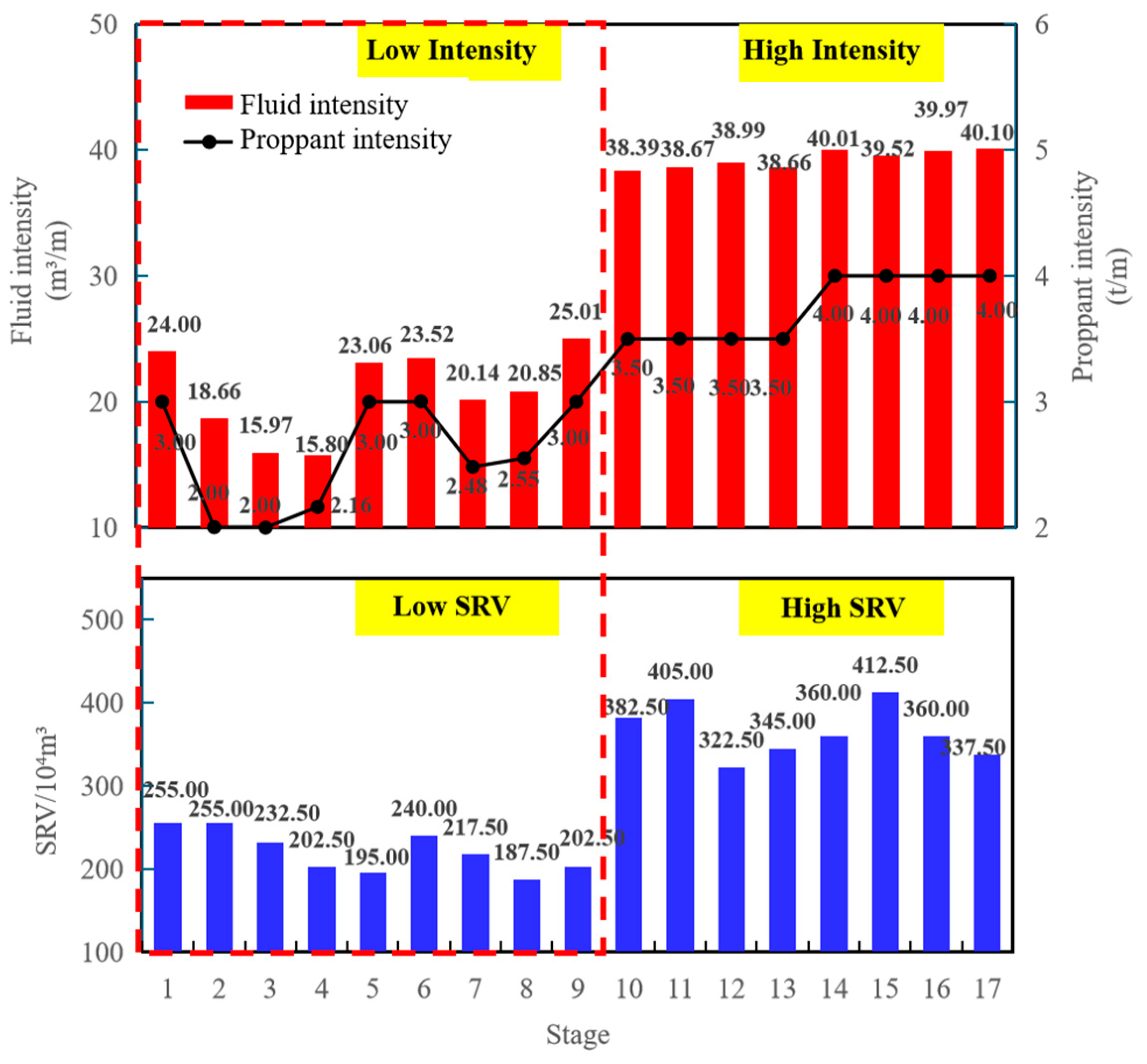

4.2. Relationship Between Curve Types and SRV

4.3. Identification of Dominant Hydraulic Fracturing Parameters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Nomenclature | ||

| Symbols | Description | Units |

| P | Treating pressure | MPa |

| ∆P | Net pressure | MPa |

| Pc | Fracture closure pressure | MPa |

| Pff | Near-wellbore tortuosity and fracture wall friction | MPa |

| Pfw | Frictional pressure loss in the wellbore | MPa |

| PL | Hydrostatic pressure from the fluid column in the vertical wellbore section | MPa |

| ∆Winj | Represents the work performed by the fluid | J |

| GC | Denotes the rock fracture toughness | J/m2 |

| σ3 | Minimum principal stress | MPa |

| A | Fracture area | m2 |

| ∆V | Fracture volume increment | m3 |

| Abreviation Expansion | ||

| ∆i(k) | Absolute Difference between Target Sequence and Reference Sequence | |

| γ(X0,norm(k), Xi,norm(k)) | Grey relational coefficient | |

| minimink∆i(k) | Minimum absolute difference in the target sequence | |

| maximaxk∆i(k) | Maximum absolute difference in the target sequence | |

| ρ | Distinguishing or resolution coefficient | |

| γ0i | Grey relational grade for individual parameter | |

| ωi | Normalized weight (from grey relational analysis) | |

References

- Auping, W.L.; Pruyt, E.; de Jong, S.; Kwakkel, J.H. The geopolitical impact of the shale revolution: Exploring consequences on energy prices and rentier states. Energy Policy 2016, 98, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Gao, S.; Huang, J.; Guan, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. A discussion on the shale gas exploration & development prospect in the Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2015, 2, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhofer, M.J.; Lolon, E.P.; Warpinski, N.R.; Cipolla, C.L.; Walser, D.; Rightmire, C.M. What is stimulated reservoir volume? SPE Prod. Oper. 2010, 25, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, C.L.; Warpinski, N.R.; Mayerhofer, M.J.; Lolon, E.P.; Vincent, M.C. The Relationship Between Fracture Complexity, Reservoir Properties, and Fracture Treatment Design. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, CO, USA, 21–24 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Kobina, F. The Influence of Geological Factors and Transmission Fluids on the Exploitation of Reservoir Geothermal Resources: Factor Discussion and Mechanism Analysis. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhai, M.; Huang, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, A.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, L. Numerical Analysis of Multiple Factors Affecting Hydraulic Fracturing in Heterogeneous Reservoirs Using a Coupled Hydraulic-Mechanical-Damage Model. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 5552287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warpinski, N.R.R.; Du, J.; Zimmer, U. Measurements of Hydraulic-Fracture-Induced Seismicity in Gas Shales. SPE Prod. Oper. 2012, 27, 240–252. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wan, X.; Shi, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, C. Application of large-array microseismic real-time monitoring technology in shale oil hydraulic fracturing. Oil Geophys. Prospect. 2024, 59, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jin, Y.; Lin, B. Classification and evaluation for stimulated reservoir volume (SRV) estimation models using microseismic events based on three typical grid structures. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 211, 110169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Fang, L.; Sun, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D. Evaluation of Borehole Hydraulic Fracturing in Coal Seam Using the Microseismic Monitoring Method. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Song, W.; Yang, X.; Zhou, D.; Dong, L.; Hu, J. Channel connection and stimulated reservoir volume estimation derived by the timing, location, and focal mechanism of microseismic events. Interpretation 2023, 11, T75–T87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liao, X.; Ye, H. The Performance Evaluation of Old Well after SRV in Ordos Basin Tight Oil Reservoir. In Proceedings of the SPE Trinidad and Tobago Section Energy Resources Conference, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, 9–11 June 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Shale-gas well test analysis and evaluation after hydraulic fracturing by stimulated reservoir volume (SRV). Nat. Gas Ind. B 2016, 3, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennour, Z.; Watanabe, S.; Chen, Y.; Ishida, T.; Akai, T. Evaluation of stimulated reservoir volume in laboratory hydraulic fracturing with oil, water and liquid carbon dioxide under microscopy using the fluorescence method. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2018, 4, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Zhong, Y. Experimental Study on Synergistic Application of Temporary Plugging and Propping Technologies in SRV Fracturing of Gas Shales. Chem. Technol. Fuels Oils 2021, 57, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.Z. Optimization and Evaluation of Multiple Hydraulically Fractured Parameters in Random Naturally Fractured Model Blocks: An Experimental Investigation. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2018, 36, 3411–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; Hu, Q.; Yan, B.; Yu, C.; Peng, S. Evaluation of Hydraulic Fracturing in Coal Seam Based on Time Difference-Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 10955–10971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Du, S.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, M. Evaluation of hydraulic fracturing effect on coalbed methane reservoir based on deep learning method considering physical constraints. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 212, 110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Pan, D.; Zhai, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, C. Evaluation of the gas production enhancement effect of hydraulic fracturing on combining depressurization with thermal stimulation from challenging ocean hydrate reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 83, 103621-1–103621-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 Sequestration to Hydrogen Storage: Further Utilization of Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazelipour, W. Development of Techniques to Integrate Hydraulic Fracturing Design and Reservoir Simulation Technologies—Application to Forecast Production of Stimulated Wells in Unconventional Gas Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the Society of Petroleum Engineers Middle East Unconventional Gas Conference and Exhibition, Muscat, Oman, 31 January–2 February 2011; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M.F.; Morales, A.; Yu, W.; Miao, J. Characterization of complex hydraulic fractures in Eagle Ford shale oil development through embedded discrete fracture modeling. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Zhang, L.-H.; Shan, B.-C. Mathematical model of fractured horizontal well in shale gas reservoir with rectangular stimulated reservoir volume. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 59, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatykov, T.; Bimuratkyzy, K. Case Study: An Approach for Hydraulic Fracturing Minifrac G-Function Analysis in Relation to Facies Distribution in Multilayered Clastic Reservoirs. SPE Prod. Oper. 2022, 37, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, D.; Du, C.; Ma, P.; Li, M.; Gao, H. Graphic Template Establishment and Productivity Evaluation Model of Post-Fracturing Based on the Fluctuation Pattern of G-Function Curve. Processes 2023, 11, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhou, F. A new multi-fracture geometry inversion model based on hydraulic-fracture treatment pressure falloff data. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 215, 110724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wan, Y.; Geng, X.; Su, Y.; Zhang, X. Quantitative evaluation and application of main controlling factors for high production of shale gas horizontal wells. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2021, 28, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, X.; Hou, L.; Jiang, T.; Gao, D.; Zhang, C. Influencing factors of fracture morphology in deep shale. Lithol. Reserv. 2019, 31, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Luo, S.; Hua, L.; Tang, H.; Sun, Z. Prediction of fracturing sweet spots in tight conglomerate reservoirs: A case study of the Ma18 block. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 14174–14183. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, H.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Duan, G.; Lai, J.; Jiang, M. Numerical simulation of complex fracture propagation during shallow shale gas fracturing in Zhaotong. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2023, 51, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Jiang, T.; Jia, C.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Su, Y.; Wei, R. A new method for post-fracturing evaluation of shale gas wells based on construction curves. Nat. Gas Ind. 2016, 36, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, K.G.; Smith, M.B. Interpretation of Fracturing Pressures. J. Pet. Technol. 1981, 33, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economides, M.J.; Nolte, K.G. Reservoir Stimulation, 3rd ed; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, K. Analysis and application of fracturing construction curves in shale gas wells. J. Jianghan Pet. Staff. Univ. 2016, 29, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Chang, X.; Yao, Z.X.; Wang, Y.B. Fracture monitoring and reservoir evaluation using the microseismic method. Chin. J. Geophys. 2019, 62, 707–719. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.-W. Gray relational analysis method for intuitionistic fuzzy multiple attribute decision making. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 11671–11677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.J. Application of grey correlation method in the analysis of factors affecting reservoir stimulation effectiveness. Oil Gas Well Test. 2023, 32, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, X.G. Evaluation of deep shale reservoir fracturing effectiveness based on microseismic monitoring. J. Oil Gas Technol. 2024, 46, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Miao, W. Volume fracturing technology of deep shale gas in southern Sichuan. Reserv. Eval. Dev. 2021, 11, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.; Liu, B.; Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Wei, H.; Yu, B.; Dong, L.; Zhong, P.; Lin, H. Analysis on Correlation Model Between Fracture Network Complexity and Gas-Well Production: A Case in the Y214 Block of Changning, China. Energies 2024, 17, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

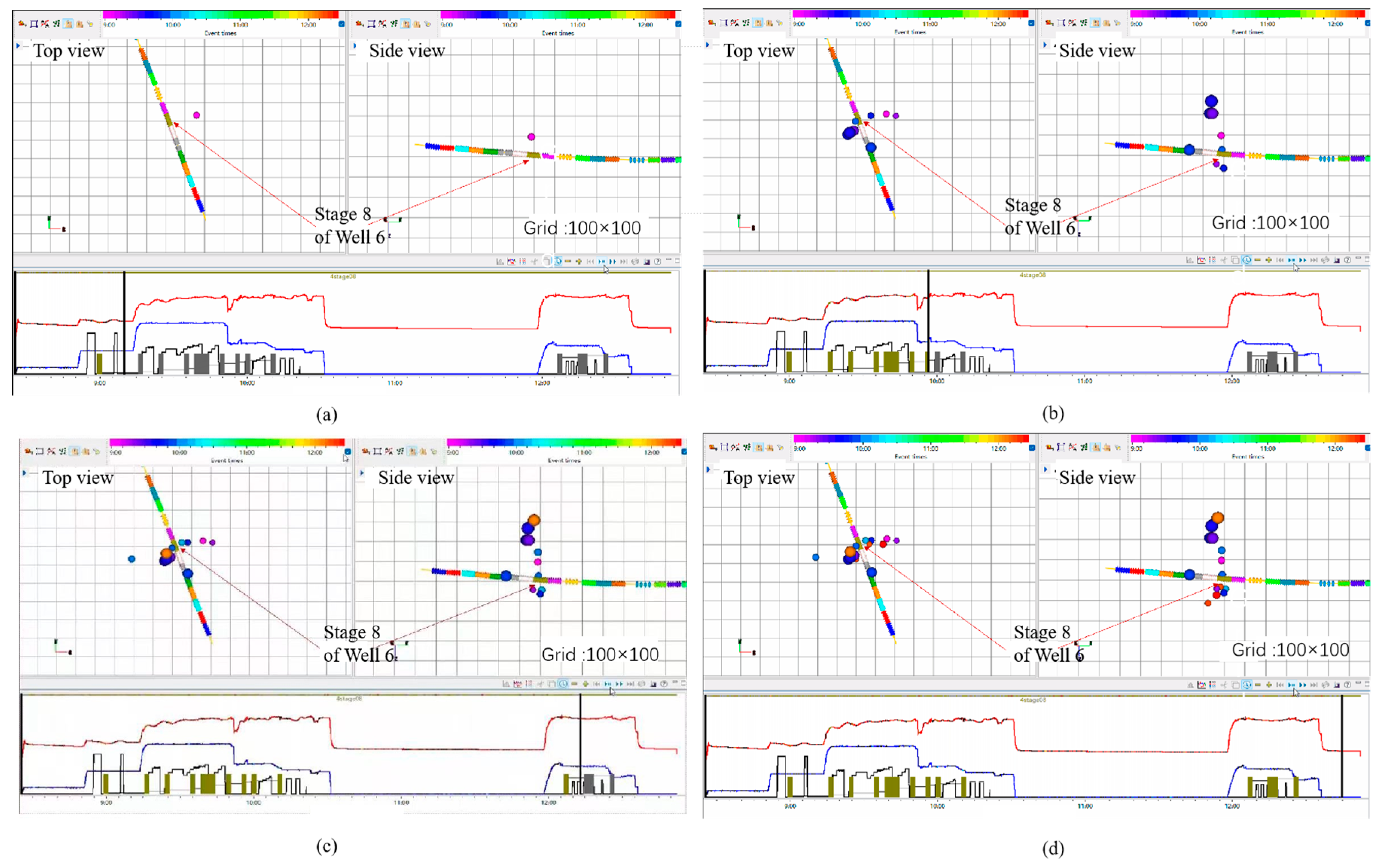

| Stage | Operation Time | Log t Range | Microseismic Characteristics | Pressure Curve Characteristics | Stage Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation Stage | 10:00–10:30 | 1.49–1.63 | Few events concentrated near the wellbore, limited energy release | Slight pressure increase | Fracture initiation |

| Propagation Stage | 10:30–11:00 | 1.63–2.05 | Dense events extending westward, rapid growth of fracture geometry | Stable pressure response with near-zero slope | Fracture propagation |

| Stabilization Stage | 11:00–11:30 | 2.05–2.19 | Fewer events, stable spatial distribution | Pressure remains steady with slight decline | Fracture stabilization /cessation of growth |

| Pressure Curve Diagnosis Type | Number of Stages | Microseismic Signature |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Type | 12 | Linear/Band Distribution, Balanced Propagation |

| Gradually increasing type | 9 | Unidirectional/Confined Propagation |

| Declining Type | 9 | Complex/Divergent Pattern |

| Well Name | Stable Type | Gradually Increasing Type | Declining Type | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platform A | Number | 32 | 4 | 2 | 38 |

| Percentage | 84.21% | 10.53% | 5.26% | 100% | |

| Platform B | Number | 39 | 14 | 5 | 58 |

| Percentage | 67.24% | 24.14% | 8.62% | 100% | |

| Platform C | Number | 67 | 12 | 5 | 84 |

| Percentage | 79.76% | 14.29% | 5.95% | 100% | |

| Platform D | Number | 62 | 12 | 19 | 93 |

| Percentage | 66.67% | 12.90% | 20.43% | 100% | |

| Slope Category | Mean | Std | … | 50% | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable type | 267.46 | 86.81 | … | 262.5 | 324.18 | 475.2 |

| Gradually increasing type | 286.24 | 92.87 | … | 312 | 356 | 422.8 |

| Declining type | 253.1 | 94.4 | … | 257.5 | 280.2 | 514.8 |

| Stage | SRV ×104 m3 | Breakdown Pressure MPa | Shut-In Pressure MPa | Fluid Intensity m3/m | Proppant Intensity t/m | Total Fluid Volume m3 | Total Proppant Mass t | Injection Rate m3/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 107.2 | 69.08 | 63 | 20.08 | 2 | 1604.24 | 154.11 | 18 |

| 2 | 98.8 | 71.52 | 63.5 | 19.6 | 2 | 1566.01 | 154.05 | 18 |

| 3 | 369.6 | 69.67 | 63 | 22.05 | 2 | 1754.9 | 154.15 | 18 |

| 4 | 282.8 | 70.73 | 63.9 | 5.19 | 1.08 | 521 | 100.17 | 6 |

| 5 | 307.6 | 72.21 | 64.6 | 4.8 | 0.98 | 528.87 | 100.24 | 6 |

| 6 | 408.4 | 70.87 | 64.6 | 19.1 | 2 | 1690.85 | 178.14 | 19 |

| 7 | 308.8 | 72.24 | 64.5 | 18.3 | 2.04 | 1621.28 | 173.69 | 18 |

| 8 | 514.8 | 73.07 | 66 | 24.92 | 3.02 | 2032.68 | 235.26 | 20 |

| 9 | 234.8 | 69.81 | 66 | 19.81 | 2.03 | 1624.96 | 160.14 | 18 |

| 1st Most Influential | 2nd Most Influential | 3rd Most Influential | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | Fluid Intensity (0.555) | Total Fluid Volume (0.393) | Total Proppant Mass (0.322) |

| 0.2 | Fluid Intensity (0.659) | Total Fluid Volume (0.483) | Total Proppant Mass (0.440) |

| 0.3 | Fluid Intensity (0.721) | Total Fluid Volume (0.546) | Total Proppant Mass (0.519) |

| 0.4 | Fluid Intensity(0.763) | Total Fluid Volume (0.593) | Total Proppant Mass (0.577) |

| 0.5 | Fluid Intensity(0.793) | Total Fluid Volume (0.631) | Total Proppant Mass (0.621) |

| 0.6 | Fluid Intensity (0.816) | Total Fluid Volume (0.662) | Total Proppant Mass (0.657) |

| 0.7 | Fluid Intensity (0.834) | Total Fluid Volume (0.688) | Total Proppant Mass (0.686) |

| 0.8 | Fluid Intensity (0.849) | Total Proppant Mass (0.710) | Total Fluid Volume (0.710) |

| 0.9 | Fluid Intensity (0.861) | Total Proppant Mass (0.731) | Total Fluid Volume (0.729) |

| Breakdown Pressure MPa | Shut-In Pressure MPa | Fluid Intensity m3/m | Proppant Intensity t/m | Total Fluid Volume m3 | Total Proppant Mass t | Injection Rate m3/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platform A | 0.675 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.645 | 0.62 | 0.58 |

| Platform D | 0.6 | 0.675 | 0.595 | 0.633 | 0.603 | 0.605 | 0.59 |

| Block X, Sichuan Basin | 0.638 | 0.653 | 0.673 | 0.621 | 0.624 | 0.613 | 0.585 |

| Weight | 0.145 | 0.148 | 0.153 | 0.141 | 0.142 | 0.139 | 0.132 |

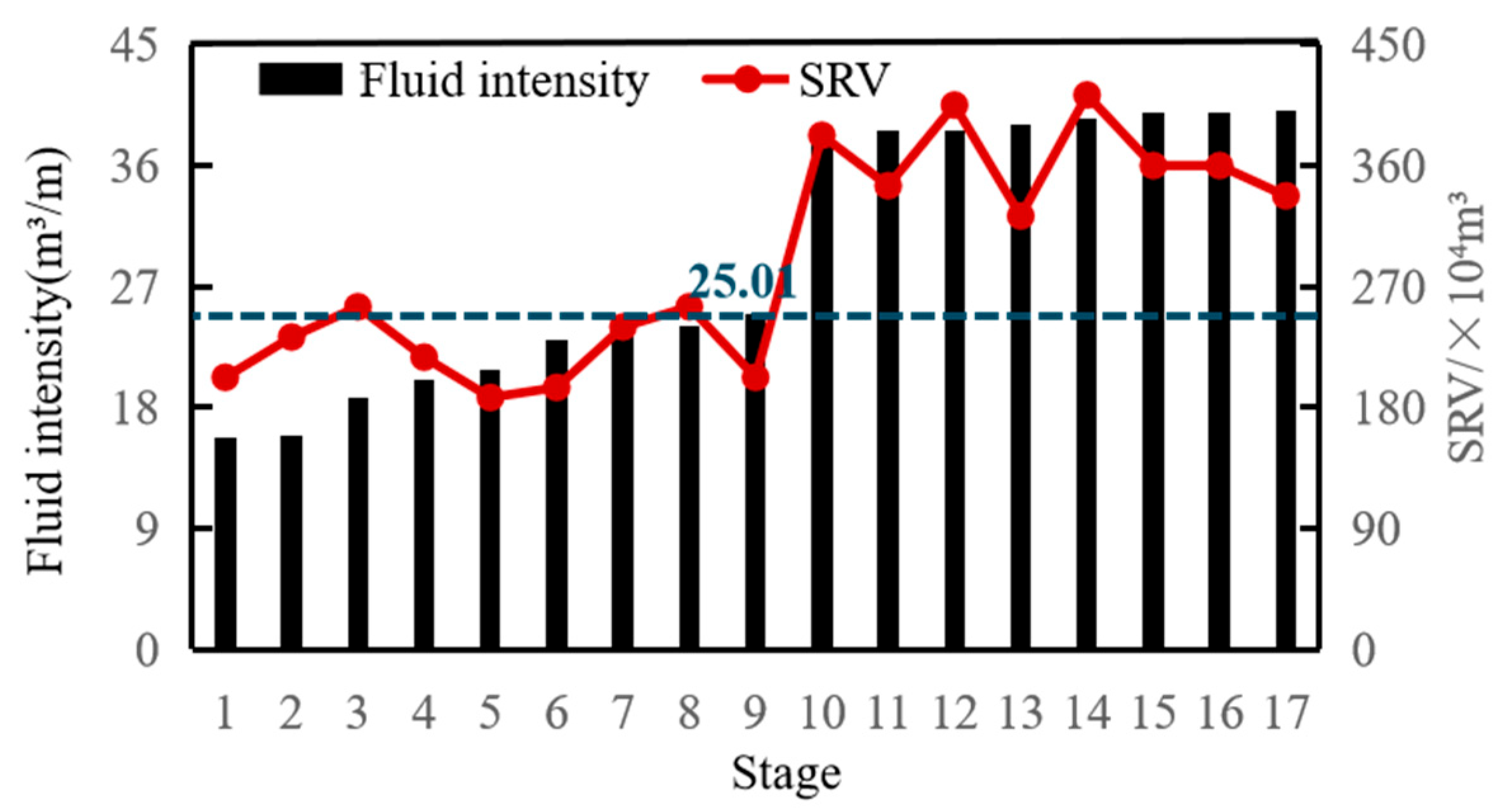

| Fluid Intensity Range (m3/m) | SRV Response

Characteristics | Pressure Fluctuation

Amplitude (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| <25 | Increase of 1.09% | ±5.14 |

| 25–40 | Increase of 68.72% | ±1.96 |

| Brittleness Index (%) | SRV | Proppant Intensity t/m | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ×104 m3 | |||

| High Brittleness Index | 79.2 | 475.2 | 2.92 | 0.78 |

| 79.2 | 422.8 | 2.9 | ||

| 79.2 | 366 | 3.05 | ||

| 79 | 194.8 | 2 | ||

| 79 | 274.4 | 2.94 | ||

| 76 | 138 | 1.11 | ||

| 79.1 | 181.2 | 2 | ||

| 79.1 | 329.2 | 3 | ||

| 79 | 150 | 2.05 | ||

| 79 | 334 | 2.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Y.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Deng, W.; Zhou, X.; Song, W.; Du, Y.; Hu, X. Log-Log Pressure Curve–Based Analysis and Evaluation of Shale Gas Stimulation: A Case Study from Block X, Sichuan Basin. Energies 2025, 18, 6213. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236213

Song Y, Yang X, Huang Y, Deng W, Zhou X, Song W, Du Y, Hu X. Log-Log Pressure Curve–Based Analysis and Evaluation of Shale Gas Stimulation: A Case Study from Block X, Sichuan Basin. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6213. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236213

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yi, Xinjie Yang, Yongzhi Huang, Wenquan Deng, Xiaojin Zhou, Wenjing Song, Yurou Du, and Xiaodong Hu. 2025. "Log-Log Pressure Curve–Based Analysis and Evaluation of Shale Gas Stimulation: A Case Study from Block X, Sichuan Basin" Energies 18, no. 23: 6213. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236213

APA StyleSong, Y., Yang, X., Huang, Y., Deng, W., Zhou, X., Song, W., Du, Y., & Hu, X. (2025). Log-Log Pressure Curve–Based Analysis and Evaluation of Shale Gas Stimulation: A Case Study from Block X, Sichuan Basin. Energies, 18(23), 6213. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236213