TESE-Informed Evolution Pathways for Photovoltaic Systems: Bridging Technology Trajectories and Market Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What stage of development has PV technology reached?

- What market conditions (economic, legal, and political) determine the growth of the photovoltaic panel market?

- Which trends in the development of technical systems will prove most effective for the current stage of PV development?

2. Trends in Photovoltaic Panel Development—Literature Review

- Cells within panels (subsystem level), including:

- materials, such as the chemical composition and physical properties of semiconductors and other cell-forming components;

- design, meaning the architecture of individual cells, their arrangement, and layering structure;

- construction, referring to the manufacturing of the cell and its integration into the panel (e.g., layer connections, electrode type, sealing, etc.).

- Panels (system level), comprising:

- optimization of control systems and electronics, i.e., solutions for efficient, safe, and intelligent energy flow management (inverters, power optimizers, monitoring);

- processes, namely the conversion of solar to electrical energy, energy management, storage, grid connection, distribution, and settlement.

- Integration with building infrastructure (application level) concerns methods and standards for installing panels in buildings (BIPV), urban planning, solar farms, and integration with other technologies, in other words, connecting PV systems with specific applications in the built environment.

- Market conditions (environment level), encompassing economic, legal, and ecological considerations.

- Optimization of control systems and electronics in photovoltaic panels. Particular emphasis is placed on reducing undesirable effects, such as leakage currents and losses that occur during cooperation of multiple panels with the grid. This includes the design of transformerless inverters, protective devices, and monitoring systems. These solutions enhance the safety and stability of installations, even with a high share of renewables and dynamically changing grid conditions [44,47].

- Management of the energy conversion process and integration of the panel with the grid. This practice involves advanced control systems, automatic fault detection algorithms, adaptive management of output power tailored to current installation conditions, and modeling of panel cooperation with energy infrastructure based on advanced equations and predictive systems. These solutions facilitate efficient conversion of solar energy to electricity and its further transfer to storage systems, grid reception, and settlement at various system levels [48,49,50].

- Improving the quality and reliability of panel production. Digital tools for quality analysis and production process control, such as automation, robotics, and machine learning for defect detection and reliability forecasting, are of growing importance. These ensure high repeatability in production and effective minimization of structural defects [51,52].

- A systemic approach to cooperation between panels and other energy infrastructure elements. Photovoltaic panels are now designed as components of advanced smart energy systems that incorporate not only storage and settlement, but also integration with energy sources, management devices (e.g., energy storage, FACTS systems), and tools enabling adaptive power flow control. Such an approach improves the efficiency of the entire energy process—from conversion to distribution and settlement balancing [27,32,41].

3. Materials and Methods

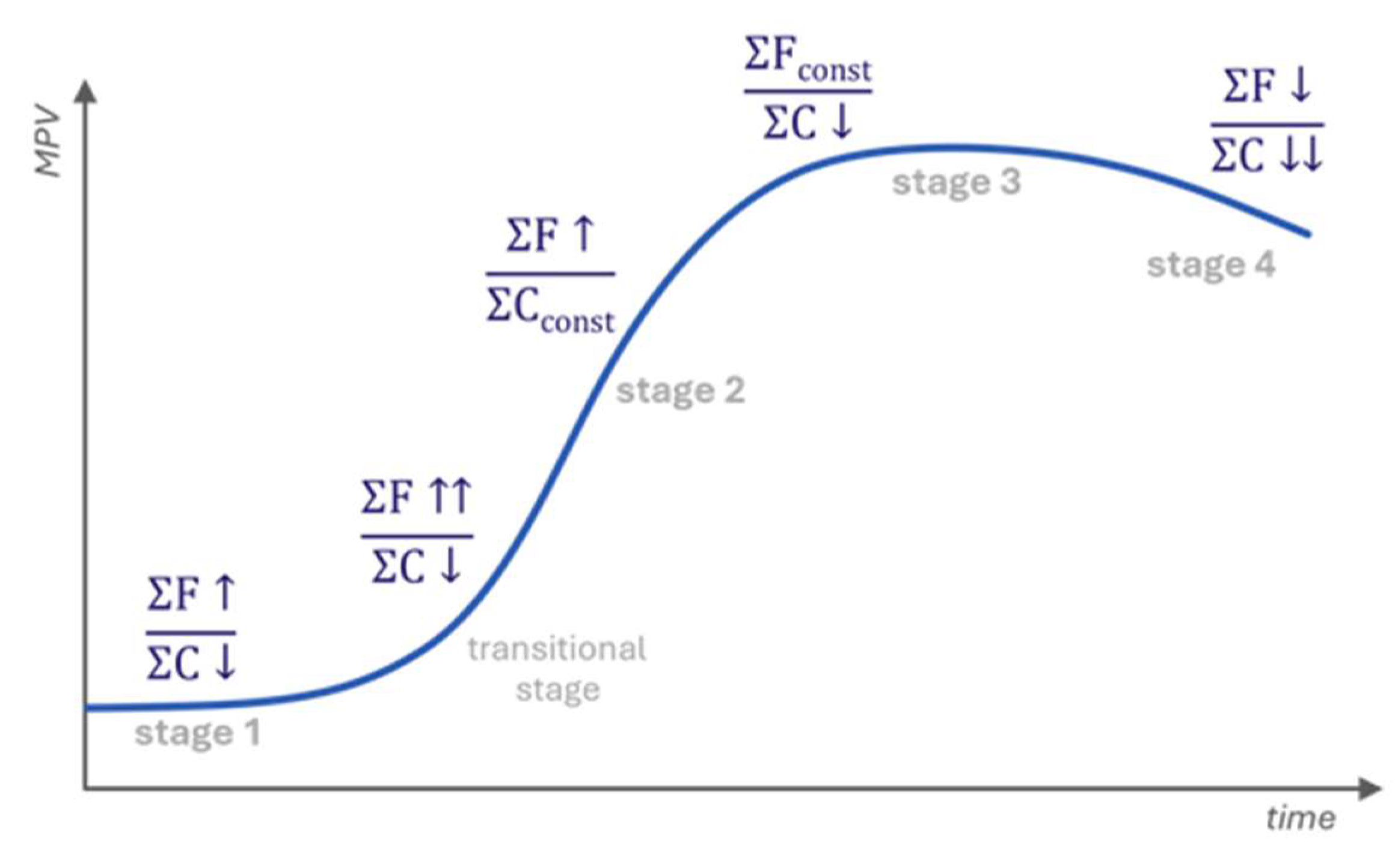

3.1. MPV and Its Position on the S-Curve

- 1st stage: infancy—the system is not yet present on the market;

- Transitional stage—the system enters the market;

- 2nd stage: rapid growth—the system is present on the market, and its production grows rapidly;

- 3rd stage: maturity—the system remains on the market, but its development is already limited;

- 4th stage: decline—the system loses its position in the market.

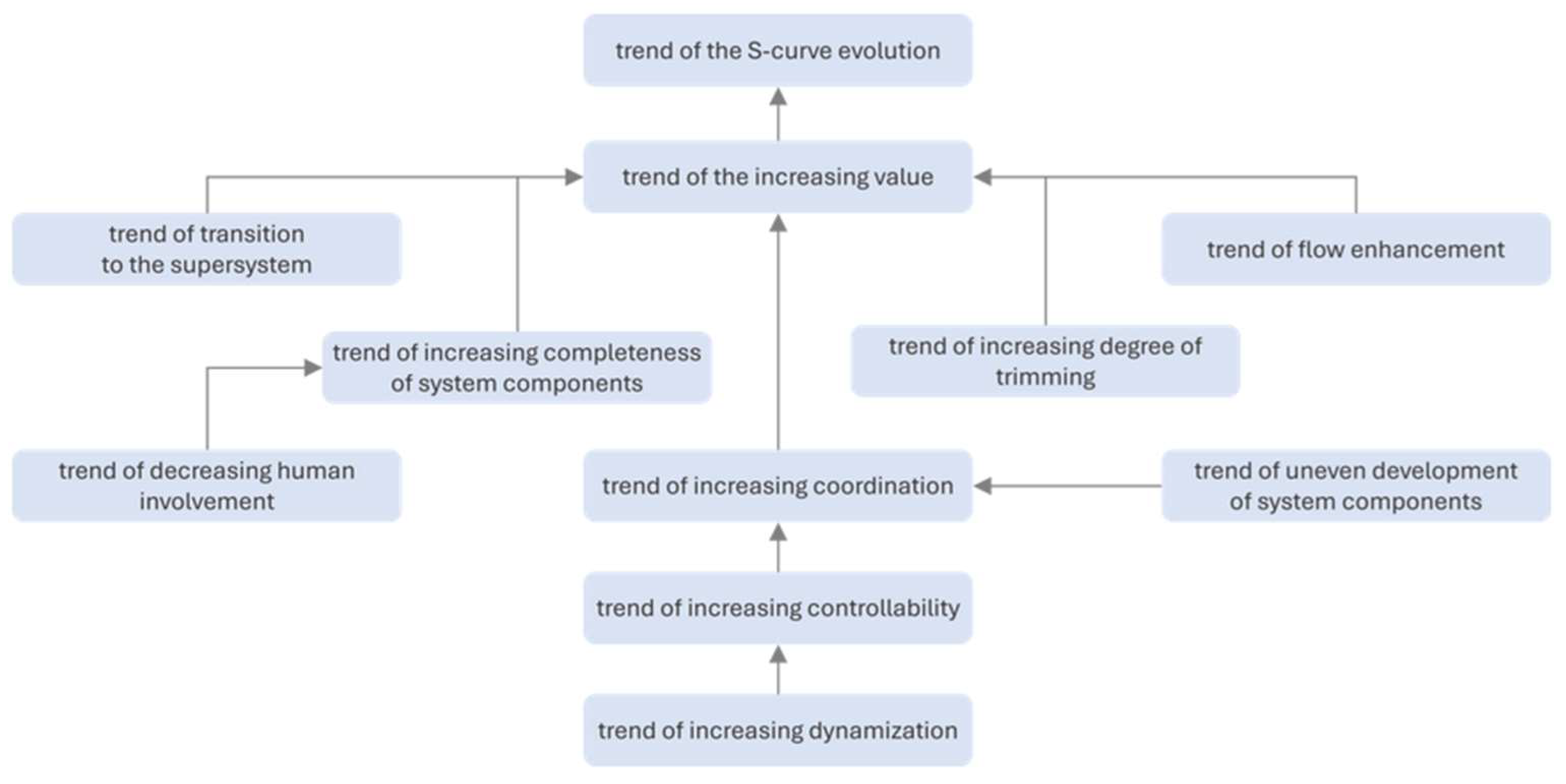

3.2. Trends of Engineering Systems Evolution as a Development Prediction Framework

functionality increases while costs decrease;

functionality increases while costs decrease;  functionality grows faster than costs;

functionality grows faster than costs;  functionality increases while costs remain stable;

functionality increases while costs remain stable;  functionality remains at the same level, while costs decrease;

functionality remains at the same level, while costs decrease;  functionality declines more slowly than costs.

functionality declines more slowly than costs.

functionality increases while costs decrease;

functionality increases while costs decrease;  functionality grows faster than costs;

functionality grows faster than costs;  functionality increases while costs remain stable;

functionality increases while costs remain stable;  functionality remains at the same level, while costs decrease;

functionality remains at the same level, while costs decrease;  functionality declines more slowly than costs.

functionality declines more slowly than costs.

- 1st stage: infancy—functionality should be improved while simultaneously reducing costs.

- Transitional stage—at this stage, MPV increases significantly, which drives cost growth; efforts should be made to ensure that the growth rate of costs remains slower than that of functionality.

- 2nd stage: rapid growth—MPV continues to increase; measures should be taken to keep cost growth below the rate of increased functionality or to maintain costs at a stable level.

- 3rd stage: maturity—MPV has limited potential for further development; the focus should shift primarily to cost reduction.

- 4th stage: decline—both functionality and costs should be reduced, but the decrease in costs must exceed the decline in functionality; for instance, producing simpler, lower-cost products that still meet customer needs.

- Trend of increasing degree of trimming—as the engineering system evolves, certain elements of the system (components or operations) are eliminated without diminishing its functionality; in many cases, this process even enhances overall system performance.

- Trend of flow enhancement—as the engineering system develops, the intensity of flows of substances, energy, or information through the system increases and/or these flows become more efficiently utilized.

- Trend of increasing system completeness—as an engineering system evolves, it progressively acquires the following typical function blocks: the operating agent (which carries out the main function (the function for which the technical system was created) of the system), transmission (which channels energy supplied to the system to the operating agent), energy source (required for system operation), and control block (which manages the system’s activity).

- Trend of decreasing human involvement—with the evolution of the engineering system, the number of functions performed by humans decreases.

- Trend of transition to the supersystem—as the technical system evolves, it becomes increasingly integrated with elements of the supersystem. (the system that contains the analyzed technical system within itself.)

- Trend of increasing coordination—as the engineering system evolves, the characteristics of its components become more coordinated with each other and with the supersystem.

- Trend of uneven development of system components—the evolution of the engineering system initially focuses on the operating agent, with other components developed later.

- Trend of increasing controllability—as the engineering system evolves, more means of controlling the system are developed.

- ▪

- Trend of increasing dynamization—the engineering system and its components progress towards greater flexibility, dynamism, and adaptability, acquiring more degrees of freedom.

3.3. Justification for Selecting TESE as a Technological Forecasting Framework

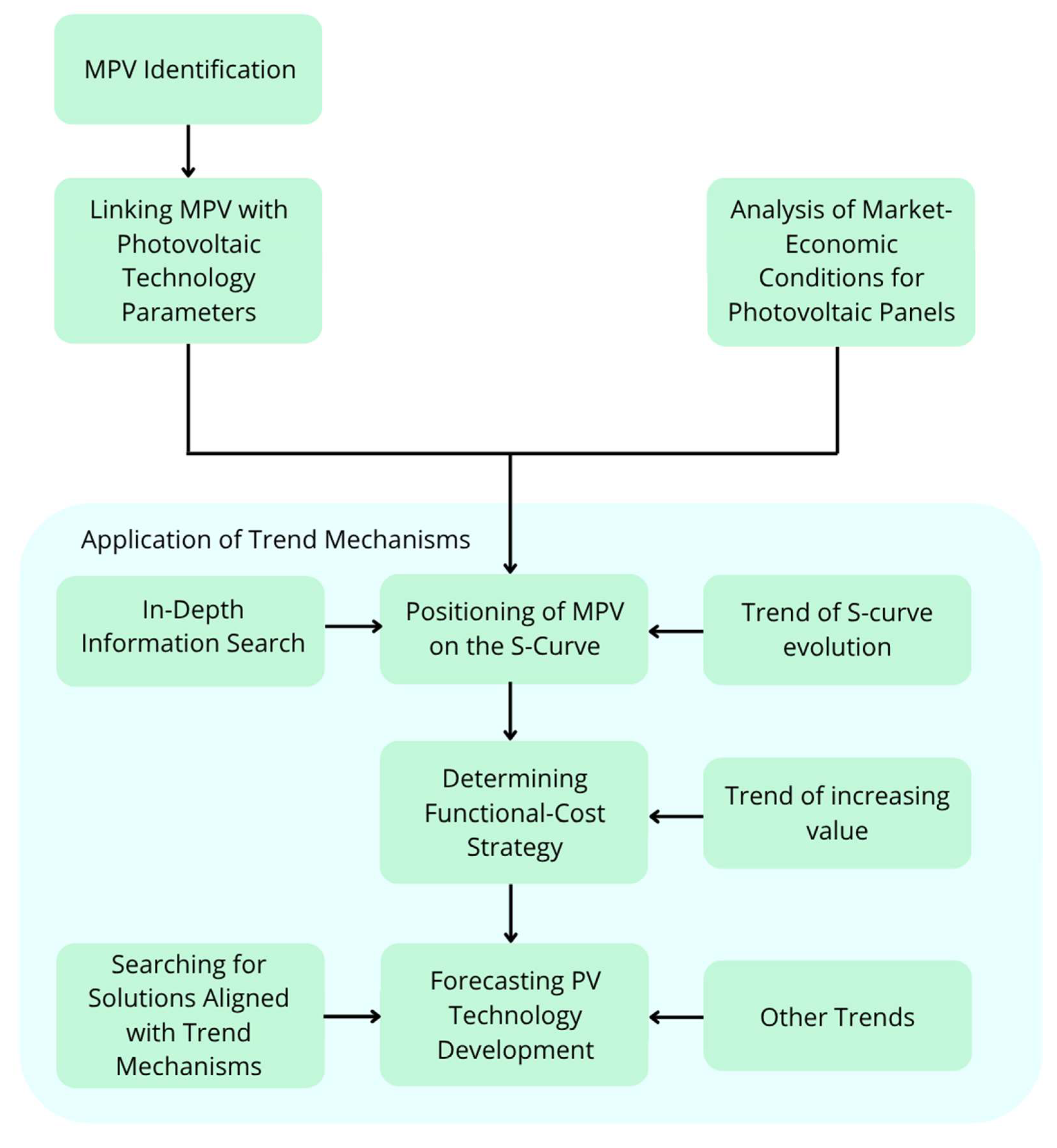

3.4. Research Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Main Parameter of Value (MPV) for Photovoltaic Panels

4.1.1. Identification of MPV for Photovoltaic Panels

4.1.2. Linking MPV with Technological Parameters of Photovoltaic Panels and Their Development Level

- The efficiency of silicon-based (Si) solar cells has reached nearly its maximal value, about 25%. In contrast, III-V compound semiconductor solar cells continue to show annual performance gains of approximately 1%. These cells have recently achieved a remarkable efficiency of 47.1%.

- Thin-film photovoltaic cells are advantageous due to minimal material consumption and steadily increasing performance. Cadmium telluride (CdTe), copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS), and amorphous silicon (α-Si) are three major materials utilized in thin-film photovoltaic cells. CIGS and CdTe PV technologies rival crystalline cells, with current record efficiencies at 23.6% for CIGS and 22.3% for CdTe. Meanwhile, perovskite photovoltaic cells exhibit extraordinary efficiency, reaching 26% for single-junction cells and 33.7% for perovskite–silicon tandem cells.

- For single-junction solar cells, sub-bandgap loss accounts for around 25%, while thermalization loss is approximately 29.8% for material with a bandgap of 1.31 eV.

- Integrating plasmonic nanoparticles on the cell surface offers promising opportunities for enhanced light trapping, while multijunction solar cells deliver exceptional spectral utilization.

- ▪

- Temperature: An increase of 1 °C results in a decrease in productivity by 0.0316 percentage points.

- ▪

- Humidity: An increase in humidity by 1% leads to a decrease in productivity by 0.021 percentage points.

- ▪

- Irradiance: An increase of irradiance by 1 W/m2 raises productivity by 0.0027 percentage points.

- ▪

- Wind speed: Higher wind speeds enhance cooling and reduce panel overheating, maintaining a lower operating temperature and positively correlating with productivity.

- ▪

- Dew point: A high dew point adversely affects productivity, because it increases the propensity for moisture deposition on panels, forming a layer that impedes solar radiation flow and thus reduces energy output.

- ▪

- Precipitation: Rain and snow temporarily limit energy production (due to the obstruction of light by water or snow layers) but can also clean the panel surface, which, in the long run, benefits overall productivity.

- ▪

- Optimization of self-consumption [131]: Storing surplus production allows its use during non-sunny hours, reducing grid electricity purchases and raising the level of energy self-sufficiency.

- ▪

- Shortening of the payback period [132]: Economic studies indicate that combining PV with storage accelerates investment payback (down to 9 years under industrial conditions).

- ▪

- ▪

4.2. Market Assessment of Photovoltaic Panels—Current Status and Forecasts

4.3. Positioning of MPV on the S-Curve

4.3.1. Profitability

4.3.2. Independence

4.4. PV Market Development for “Profitability” and “Independence” According to Trends of Technical System Evolution

4.4.1. Trend Operation in the Context of MPV “Profitability” and “Independence”

4.4.2. Recommendations

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Alternating current |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| APAC | Asia–Pacific countries |

| ASMC | Adaptive Sliding Mode Control |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| BIPV | Building-Integrated Photovoltaics |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| BoS | Balance of System |

| CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| C&I | Commercial and Industrial |

| CdTe | Cadmium telluride |

| CIGS | copper indium gallium selenide |

| CPVT | Concentrated Photovoltaic Thermal Hybrid |

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Power |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| DC | Direct current |

| DERMS | Distributed Energy Resource Management System |

| DSO | Distribution System Operator |

| EMS | Energy Management Systems |

| EPBD | Energy Performance of Buildings Directive |

| EPCs | Energy Performance Certificates |

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| FACTS | Flexible AC Transmission Systems |

| GFM | Grid-forming inverters |

| HEMS | Home Energy Management System |

| HJT | Heterojunction Technology |

| IEC | International Electrotechnical Commission |

| IM-TLBO | Improved Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| IT | Information Technology |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| LFP | Lithium-iron-phosphate |

| MATRIZ | International TRIZ Association |

| MIPV | Mobile Integrated Photovoltaics |

| MLPE | Module Level Power Electronics |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| MPV | Main Parameter of Value |

| NMC | Nickel-manganese-cobalt |

| O&M | Operations and Maintenance |

| OPV | Organic Photovoltaics |

| PCMs | Phase Change Materials |

| PERC | Passivated Emitter and Rear Cell |

| PSH | Pumped Storage Hydropower |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PVCS | Photovoltaic Charging Stations |

| PVT | Photovoltaic Thermal Hybrid |

| R&D | Research & Development |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| STC | Standard test conditions |

| T&D | Transmission and distribution |

| TESE | Trend of Engineering System Evolution |

| TOPCon | Tunnel Oxide Passivated Contact |

| TRIZ | Theory of inventive problem solving |

| TSO | Transmission System Operator |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VPP | Virtual Power Plant |

| WEEE | Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| α-Si | Amorphous silicon |

References

- United Nations. The Paris Agreement. Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/parisagreement_publication.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Eco-nomic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels, Belgium. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality and Amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX%3A32021R1119&from=EN (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- European Commission. REPowerEU Plan. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:fc930f14-d7ae-11ec-a95f-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- SolarPower Europe. Global Market Outlook for Solar Power 2025–2029. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/global-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2025-2029/detail (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- SolarPower Europe. EU Market Outlook for Solar Power, 2025 Mid-Year Analysis. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/eu-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2025-mid-year-analysis/detail (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Padture, N.P.; Berry, J.J.; Unger, E. Halide perovskite solar photovoltaics. MRS Bull. 2024, 49, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, M.F.R. Photovoltaic-Assisted Photo(electro)catalytic Hydrogen Production: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Liu, T. Optimized photovoltaic system for improved electricity conversion. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 2022, 17, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam, E.; Ramasubramanian, B.; Reddy, V.S.; Dalapati, G.K.; Ghosh, S.; Pa, T.S.; Chakrabortty, S.; Motapothula, M.R.; Kumar, A.; Ramakrishna, S.; et al. Emerging trends in cooling technologies for photovoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 192, 114203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakfan, A.; Bin Salamah, Y. Development and Performance Evaluation of a Hybrid AI-Based Method for Defects Detection in Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Prospects of Photovoltaic Technology. Engineering 2022, 21, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Shaping the solar future: An analysis of policy evolution, prospects and implications in China’s photovoltaic industry. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanoot, A.K.; Mokhlis, H.; Mekhilef, S.; Alghoul, M.; Shareef, H.; Samatar, A.M. Distributed PV systems in Saudi Arabia: Current status, challenges, and prospects. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 55, 101535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Nureen, N.; Irfan, M.; Ali, M. The current developments and future prospects of solar photovoltaic industry in an emerging economy of India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 46270–46281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endiz, M.S.; Coşgun, A.E. Assessing the potential of solar power generation in Turkey: A PESTLE analysis and comparative study of promising regions using PVsyst software. Sol. Energy 2023, 266, 112153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita, A.; Castillejo-Cuberos, A.; García, M.; Mata-Torres, C.; Simsek, Y.; García, R.; Antonanzas-Torres, F.; Escobar, R.A. State of the art and future prospects for solar PV development in Chile. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 701–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, S.; Olabi, A.G.; Mahmoud, M. A review of solar photovoltaic technologies: Developments, challenges, and future perspectives. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Rezgui, B.D.; Khan, M.T.; Al-Sulaiman, F. Perovskite-based tandem solar cells: Device architecture, stability, and economic perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikovenko, S. Knowledge-Base Innovation—A Technology of the Future. In From Knowledge Intensive CAD to Knowledge Intensive Engineering; IFIP TC5 WG5.2. Fourth Workshop on Knowledge Intensive CAD 22–24 May 2000, Parma, Italy; Cugini, U., Wozny, M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikovenko, S. Training Materials for MA TRIZ Level; GEN3 Partners: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ghane, M.; Ang, M.C.; Kadir, R.A.; Ng, K.W. Technology Forecasting Model Based on Trends of Engineering System Evolution (TESE) and Big Data for 4IR. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Student Conference on Research and Development (SCOReD), Batu Pahat, Malaysia, 27–29 September 2020; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Schollmeyer, J.; Tamuzs, V. Deducing Altshuller’s Laws of Evolution of Technical Systems. In New Opportunities for Innovation Breakthroughs for Developing Countries and Emerging Economies; Benmoussa, R., De Guio, R., Dubois, S., Koziołek, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadnis, N.S. Innovation Portfolio Management: How Can TRIZ Help? In Systematic Innovation Partnerships with Artificial Intelligence and Information Technology; Nowak, R., Chrząszcz, J., Brad, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, A. Combining hidden customer need tools and MPV to generate product concept. In Proceedings of the TRIZfest International Conference, Beijing, China, 28–30 July 2016; Souchkov, V., Ed.; International TRIZ Association—MATRIZ: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Teplov, R.; Chechurin, L.; Podmetina, D. TRIZ as innovation management tool: Insights from academic literature. Int. J. Technol. Mark. 2017, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Ayaz, M.; Khan, M.; Adil, S.F.; Farooq, W.; Ullah, N.; Tahir, M.N. Recent Trends in Sustainable Solar Energy Conversion Technologies: Mechanisms, Prospects, and Challenges. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 6283–6301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guesnay, Q.; Sahli, F.; Artuk, K.; Turkay, D.; Kuba, A.G.; Mrkyvkova, N.; Vegso, K.; Siffalovic, P.; Schreiber, F.; Lai, H.; et al. Pizza Oven Processing of Organohalide Perovskites (POPOP): A Simple, Versatile and Efficient Vapor Deposition Method. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2303423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, B.; Zheng, N. Optimizing Solvent Chemistry for High-Quality Halide Perovskite Films. Accounts Mater. Res. 2024, 6, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yan, C.; Fang, C. Solvent engineering for the formation of high-quality perovskite films: A review. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Rahaman, Z.; Ali, L. Pressure-Induced Band Gap Engineering of Nontoxic Lead-Free Halide Perovskite CsMgI3 for Optoelectronic Applications. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 24942–24951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurokawa, K. PV systems in urban environment. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2001, 67, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, A.T.; Visan, A.I.; Negut, I. Laser-Fabricated Micro/Nanostructures: Mechanisms, Fabrication Techniques, and Applications. Micromachines 2025, 16, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S.H.; Ng, C.H.; Ng, Y.H.; Islam, A.; Hayase, S.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H. Resolve deep-rooted challenges of halide perovskite for sustainable energy development and environmental remediation. Nano Energy 2022, 99, 107401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teomete, E. Roughness damage evolution due to wire saw process. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2011, 12, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, J.; Huang, D.; Wang, J.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; et al. Optimized Molecular Packing and Nonradiative Energy Loss Based on Terpolymer Methodology Combining Two Asymmetric Segments for High-Performance Polymer Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 20393–20403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchan, K.; Jacobsson, T.J.; Rehermann, C.; Unger, E.L.; Kirchartz, T.; Wolff, C.M. Rationalizing Performance Losses of Wide Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells Evident in Data from the Perovskite Database. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 14, 2303420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odabaşı, Ç.; Yıldırım, R. Performance analysis of perovskite solar cells in 2013–2018 using machine-learning tools. Nano Energy 2019, 56, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singareddy, A.; Sadula, U.K.R.; Nair, P.R. Phase segregation induced efficiency degradation and variability in mixed halide perovskite solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 225501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, G.; Brambilla, M. Photovoltaics and TLC. In Proceedings of the 10th International Telecommunications Energy Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 October–2 November 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Radisavljevic-Gajic, V.; Karagiannis, D.; Gajic, Z. The Modeling and Control of (Renewable) Energy Systems by Partial Differential Equations—An Overview. Energies 2023, 16, 8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qu, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W. Optimization of heterojunction back-contact (HBC) crystalline silicon solar cell based on Quokka simulation. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, A. Toward Deregulated, Smart and Resilient Power Systems with Massive Integration of Renewable Energy in Japan. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 17, 1242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponrekha, A.S.; Subathra, M.S.P.; Bharatiraja, C.; Kumar, N.M.; Alhelou, H.H. A topology review and comparative analysis on transformerless grid-connected photovoltaic inverters and leakage current reduction techniques. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 19, e12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, R.; Minuto, F.D.; Bracco, G.; Mattiazzo, G.; Borchiellini, R.; Lanzini, A. Supporting Decarbonization Strategies of Local Energy Systems by De-Risking Investments in Renewables: A Case Study on Pantelleria Island. Energies 2022, 15, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.L.; Stershic, J.; Ryan, T.; Young, M. The Future of Building Science Education with the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon. In Proceedings of the 2022 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 26–29 June 2022; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kerekes, T. Analysis and Modeling of Transformerless Photovoltaic Inverter Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Aalborg Universitet, Aalborg, Denmark. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/en/publications/analysis-and-modeling-of-transformerless-photovoltaic-inverter-sy (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Esram, T.; Chapman, P.L. Comparison of Photovoltaic Array Maximum Power Point Tracking Techniques. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2007, 22, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalva, M.G.; Gazoli, J.R.; Filho, E.R. Comprehensive Approach to Modeling and Simulation of Photovoltaic Arrays. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ye, Z.; Lim, L.H.I.; Dong, Z. Very short term irradiance forecasting using the lasso. Sol. Energy 2015, 114, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Vu, Q.D. Identification of parameter correlations for parameter estimation in dynamic biological models. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, Y.; Javier, G.M.; Abdullah-Vetter, Z.; Dwivedi, P.; Hameiri, Z. Machine learning for advanced characterisation of silicon photovoltaics: A comprehensive review of techniques and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.-T.; Xu, Z.-L.; Li, F.-M.; Chen, F.-Y.; Yu, J.-Y.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xia, B.Y. Recent advances in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 5652–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogdakis, K.; Karakostas, N.; Kymakis, E. Up-scalable emerging energy conversion technologies enabled by 2D materials: From miniature power harvesters towards grid-connected energy systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3352–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirskiy, A.; Litvin, S.; Ikovenko, S.; Thurnes, C.M.; Adunka, R. Trends of Engineering Systems Evolution (TESE): TRIZ Paths to Innovation; TRIZ Consulting Group GmbH: Sulzbach-Rosenberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MATRIZ. Trend of the S-Curve Evolution. International TRIZ Association. Available online: https://wiki.matriz.org/knowledge-base/triz/trends-of-engineering-systems-evolution-tese-5919/trend-of-s-curve-evolution/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Ikovenko, S. Directions for Future TRIZ Development and Applications. Available online: https://www.osaka-gu.ac.jp/php/nakagawa/TRIZ/eTRIZ/elinksref/eJapanTRIZ-CB/e4thTRIZSymp08/eTRIZSymp08Presentations/I01eS-Ikovenko.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Phadnis, N.; Torkkeli, M. Impact of Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ) on Innovation Portfolio Development. In Towards AI-Aided Invention and Innovation; Cavallucci, D., Livotov, P., Brad, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, O.; Medvedev, A.; Tomashevskaya, N. Main Parameters of Value (MPV) Analysis: Where MPV Candidates Come From. In Creative Solutions for a Sustainable Development; Borgianni, Y., Brad, S., Cavallucci, D., Livotov, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, S.; Barattin, D. Definition and exploitation of trends of evolution about interaction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2014, 86, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotin, B.; Zusman, A.; Hallfell, F. TRIZ to invent your future utilizing directed evolution methodology. Procedia Eng. 2011, 9, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lyubomirskiy, A.; Litvin, S. Trends of Engineering System Evolution; GEN3 Partners: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- MATRIZ. Trends of Engineering Systems Evolution (TESE). International TRIZ Association. Available online: https://wiki.matriz.org/knowledge-base/triz/trends-of-engineering-systems-evolution-tese-5919/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- MATRIZ. Trend of Increasing Value. International TRIZ Association. Available online: https://wiki.matriz.org/knowledge-base/triz/trends-of-engineering-systems-evolution-tese-5919/trend-of-increasing-value/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ghane, M.; Cavallucci, D. An Analytical Model for Sustainable Product Ideation Based on Main Parameter Values and Social Network Data. In World Conference of AI-Powered Innovation and Inventive Design; Cavallucci, D., Brad, S., Livotov, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATRIZ. TRIZ Knowledge Base. International TRIZ Association. Available online: https://wiki.matriz.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Krupińska, M.; Yatsunenko, S.; Ikovenko, S. Głos produktu zestrojony z głosem klienta [The Voice of the Product Aligned with the Voice of the Customer]. Prod. Manag. 2024, 4, 64–70. Available online: https://production-manager.pl/czasopismo/production-manager-4-2024 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Ikovenko, S. TRIZ and Computer Aided Inventing. In Building the Information Society; Jacquart, R., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chybowska, D.; Chybowski, L. A Review of TRIZ Tools for Forecasting the Evolution of Technical Systems. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2019, 27, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, G.; Zini, M.; Russo, D. Functional TRIZ analysis. In Proceedings of the ICED’09: The 17th International Conference on Engineering Design, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 24–27 August 2009; pp. 371–384. [Google Scholar]

- Ghane, M.; Ang, M.C.; Cavallucci, D.; Kadir, R.A.; Ng, K.W.; Sorooshian, S. TRIZ trend of engineering system evolution: A review on applications, benefits, challenges and enhancement with computer-aided aspects. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 174, 108833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, C.; Muenzberg, C.; Lindemann, U. Designing new concepts for household appliance with the help of TRIZ. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED17), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 August 2017; Volume 4, pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, M.; Mariun, N.; AbdulWahab, N.I. Innovating problem solving for sustainable green roofs: Potential usage of TRIZ—Theory of inventive problem solving. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 99, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, O.; Smirnova, E.; Fimin, P. Identifying the best technology for solid waste management using TRIZ-based technology scouting. In Proceedings of the MATRIZ International Conference TRIZfest-2022, Warsaw, Poland, 31 August–3 September 2022; pp. 101–112. Available online: https://matriz.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/TRIZfest-2022-Proceedings.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Nikulin, C.; Graziosi, S.; Cascini, G.; Stegmaier, R. Integrated Model for Technology Assessment and Expected Evolution: A Case Study in the Chilean Mining Industry. J. Integr. Des. Process Sci. 2013, 17, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdonosov, V.; Kozlita, A.; Zhivotova, A. TRIZ evolution of black oil coker units. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2015, 103, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, O. Use of AI in the TRIZ Innovation Process: A TESE-Based Forecast. In World Conference of AI-Powered Innovation and Inventive Design; Cavallucci, D., Brad, S., Livotov, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, Z.A.; Iqbal, M.S. The Review of Patent Literature and Analytics of Robo-Physic System Evolution Using Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ). In Advances in Intelligent Computing Techniques and Applications; Saeed, F., Mohammed, F., Fazea, Y., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Lin, K.-Y. A Review of Technological Forecasting from the Perspective of Complex Systems. Entropy 2022, 24, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAndrew, T.; Wattanachit, N.; Gibson, G.C.; Reich, N.G. Aggregating predictions from experts: A review of statistical methods, experiments, and applications. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2020, 13, e1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jang, D.; Jun, S.; Park, S. A Predictive Model of Technology Transfer Using Patent Analysis. Sustainability 2015, 7, 16175–16195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, D.; Ryu, J.-B.; Jun, S. An Interval Estimation Method of Patent Keyword Data for Sustainable Technology Forecasting. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doos, L.; Packer, C.; Ward, D.; Simpson, S.; Stevens, A. Past speculations of the future: A review of the methods used for forecasting emerging health technologies. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.M. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: A narrative review. Medicine 2023, 102, e32829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederberger, M.; Spranger, J. Delphi Technique in Health Sciences: A Map. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Tapinos, E.; Knight, L. Scenario-driven roadmapping for technology foresight. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 124, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, G.V.; Mello, C.H.P. How to develop technology roadmaps? The case of a Hospital Automation Company. Production 2015, 26, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- González, C.J.I.; Ogliari, A.; de Abreu, A.F. A Contribution to Guide the Use of Support Tools for Technology Roadmapping: A Case Study in the Clothing industry. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2013, 8, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, R.; Amaral, D.C.; Caetano, M. Framework for continuous agile technology roadmap updating. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2018, 15, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Way, R.; Verdolini, E.; Anadon, L.D. Comparing expert elicitation and model-based probabilistic technology cost forecasts for the energy transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e1917165118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, M.; Abbas, A.E.; Budescu, D.V.; Galstyan, A. A survey of human judgement and quantitative forecasting methods. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, rsos.201187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regenfelder, M.; Slowak, A.P.; Werner, A.; Weiblen, M.; Goldmann, J.; Senger, S. The German Case of Clean Energy Transition. Teh. Glas. J. 2025, 19, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukoro, V.; Sharmina, M.; Gallego-Schmid, A. A review of business models for access to affordable and clean energy in Africa: Do they deliver social, economic, and environmental value? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 88, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridha, H.M.; Gomes, C.; Hizam, H.; Ahmadipour, M.; Heidari, A.A.; Chen, H. Multi-objective optimization and multi-criteria decision-making methods for optimal design of standalone photovoltaic system: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A. Model of Choice Photovoltaic Panels Considering Customers’ Expectations. Energies 2021, 14, 5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargnoli, M.; Salvatori, E.; Tronci, M. A Green Marketing and Operations Management Decision-Making Approach Based on QFDE for Photovoltaic Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, C.; Kennedy, E.H.; Familia, T. Rooftop solar in the United States: Exploring trust, utility perceptions, and adoption among California homeowners. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzaid, H.; AbuMoeilak, L.; Alzaatreh, A. A structural equation modeling of customer attitudes towards residential solar initiatives in Jordan. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 101038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yoo, H.; Kim, J.; Koo, C.; Jeong, K.; Lee, M.; Ji, C.; Jeong, J. A model for determining the optimal lease payment in the solar lease business for residences and third-party companies—With focus on the region and on multi-family housing complexes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehir, M.A.; Batman, A.; Bagriyanik, M. Review and comparison of demand response options for more effective use of renewable energy at consumer level. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerby, J.; Tarekegne, B. A guide to residential energy storage and rooftop solar: State net metering policies and utility rate tariff structures. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 49, 100566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwińska-Małajowicz, A.; Banaś, M.; Piecuch, T.; Pyrek, R.; Szczotka, K.; Szymiczek, J. Energy and Ecological Concept of a Zero-Emission Building Using Renewable Energy Sources—Case Study in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A. Eco-Innovation Method for Sustainable Development of Energy-Producing Products Considering Quality and Life Cycle Assessment (QLCA). Energies 2024, 17, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Qasuria, T.A.; Ibrahim, M.A. A Brief Review on Smart Grid Residential Network Schemes. Sains Malays. 2020, 49, 2989–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrichenko, L.; Mutule, A.; Zalitis, I.; Lazdins, R.; Kozadajevs, J.; Mihaila, D. Assessing the Role of Electricity Sharing in Meeting the Prerequisites for Receiving Renewable Support in Latvia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libra, M.; Mrázek, D.; Tyukhov, I.; Severová, L.; Poulek, V.; Mach, J.; Šubrt, T.; Beránek, V.; Svoboda, R.; Sedláček, J. Reduced real lifetime of PV panels–Economic consequences. Sol. Energy 2023, 259, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarte, F.; Glenk, G.; Rieger, A. Business Models and Profitability of Energy Storage. iScience 2020, 23, 101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basem, A.; Opakhai, S.; Elbarbary, Z.M.S.; Atamurotov, F.; Benti, N.E. A comprehensive analysis of advanced solar panel productivity and efficiency through numerical models and emotional neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Future of Solar Photovoltaic: Deployment, Investment, Technology, Grid Integration and Socio-Economic Aspects (A Global Energy Transformation: Paper). Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Nov/IRENA_Future_of_Solar_PV_2019.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- VDMA. International Technology Roadmap for Photovoltaics (ITRPV) 2023. 15th Ed. Verband Deutscher Maschinen-und Anlagenbau, 2024. Available online: https://www.qualenergia.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ITRPV-15th-Edition-2024-2.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Oni, A.M.; Mohsin, A.S.; Rahman, M.; Bhuian, M.B.H. A comprehensive evaluation of solar cell technologies, associated loss mechanisms, and efficiency enhancement strategies for photovoltaic cells. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 3345–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NREL. Best Research-Cell Efficiencies. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/libraries/pv/cell-pv-eff.pdf?sfvrsn=26e2254e_14 (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- IEA PVPS. Floating Photovoltaic Power Plants: A Review of Energy Yield, Reliability, and Maintenance. 2025, Photovoltaic Power Systems Technology Collaboration Programme, International Energy Agency. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/IEA-PVPS-T13-31-2025-REPORT-Floating-PV-Plants.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Elibol, E.; Özmen, Ö.T.; Tutkun, N.; Köysal, O. Outdoor performance analysis of different PV panel types. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, P.; Das, D.; Saikia, M.; Kumar, V.; Yadav, S.K.; Paramasivam, P.; Dhanasekaran, S. Comprehensive Analysis of Solar Panel Performance and Correlations with Meteorological Parameters. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 47897–47904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamisile, O.; Acen, C.; Cai, D.; Huang, Q.; Staffell, I. The environmental factors affecting solar photovoltaic output. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 208, 115073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batić, I. Impacts of different photovoltaic panel technologies on electrical energy production and CO2 emission reduction. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1519131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Loonen, R.; Hensen, J. Performance variability and implications for yield prediction of rooftop PV systems—Analysis of 246 identical systems. Appl. Energy 2022, 322, 119550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanecka, E.; Olczak, P. A specific yield comparison of 2 photovoltaic installations—Polish case study. Polityka Energetyczna—Energy Policy J. 2023, 26, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglia, A.G.; Lykoudis, S.; Argiriou, A.A.; Balaras, C.A.; Dialynas, E. Energy efficiency of PV panels under real outdoor conditions–An experimental assessment in Athens, Greece. Renew. Energy 2017, 101, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harazin, J.; Wróbel, A. Analysis and study of the potential increase in energy output generated by prototype solar tracking, roof mounted solar panels. F1000Research 2022, 9, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsema, E.; Nieuwlaar, E. Energy viability of photovoltaic systems. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA PVPS. Climatic Rating of Photovoltaic Modules: Different Technologies for Various Operating Conditions. 2020. Photovoltaic Power Systems Technology Collaboration Programme, International Energy Agency. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Report-IEA-PVPS-T13-20_2020-Climatic-Rating-of-PV-Modules.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Bothe, K.; Siefer, G.; Hinken, D.; Rauer, M.; Hohl-Ebinger, J.; Hao, X. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 64). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2024, 32, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthander, R.; Widén, J.; Nilsson, D.; Palm, J. Photovoltaic self-consumption in buildings: A review. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, A. Dobór optymalnego rozwiązania instalacji PV i magazynu energii dla budynku biurowego wyposażonego w Cen-trum Przetwarzania Danych [Selection of the optimal solution for a PV installation and energy storage for an office building equipped with a Data Processing Center]. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2024, 11, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA PVPS. Active Power Management of Photovoltaic Systems—State of the Art and Technical Solutions Task 14 PV in the 100% Renewable Energy System. International Energy Agency. 2024. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/IEA-PVPS-T14-15-REPORT-Active-Power-Management.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Rajput, P.; Singh, D.; Singh, K.Y.; Karthick, A.; Shah, M.A.; Meena, R.S.; Zahra, M.M.A. A comprehensive review on reliability and degradation of PV modules based on failure modes and effect analysis. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniela-Abigail, H.-L.; Vega-De-Lille, M.I.; Sacramento-Rivero, J.C.; Ponce-Caballero, C.; El-Mekaoui, A.; Navarro-Pineda, F. Life cycle assessment of photovoltaic panels including transportation and two end-of-life scenarios: Shaping a sustainable future for renewable energy. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deline, C.; Jordan, D.B.; Sekulic, J.; Parker; Mcdanold, B.; Anderberg, A. PV Lifetime Project—2024 NREL Annual Report. NREL, National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2024. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy24osti/90651.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Zhao, G.; Clarke, J.; Searle, J.; Lewis, R.; Baker, J. Economic analysis of integrating photovoltaics and battery energy storage system in an office building. Energy Build. 2023, 284, 112885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horzela-Miś, A.; Semrau, J. The role of renewable energy and storage technologies in sustainable development: Simulation in the construction industry. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1540423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, M.; Peng, J. Actual Performances of PV Panels in the Local Environment. Final Report. 2020. Available online: https://re.emsd.gov.hk/files/Actual_Performances_of_PV_Panels_in_the_Local_Environment.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Atia, D.M.; Hassan, A.A.; El-Madany, H.T.; Eliwa, A.Y.; Zahran, M.B. Degradation and energy performance evaluation of mono-crystalline photovoltaic modules in Egypt. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEIA. Solar Industry Research Data. Solar Energy Industries Association. 2025. Available online: https://seia.org/research-resources/solar-industry-research-data/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Qian-Jing, D. Synergy Between Solar and Storage will Drive the Clean Energy Transition. World Economic Forum. 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/04/synergy-solar-storage-clean-energy-transition/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- IEA. Batteries and Secure Energy Transitions. 2024. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/cb39c1bf-d2b3-446d-8c35-aae6b1f3a4a0/BatteriesandSecureEnergyTransitions.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- IRENA. Renewable Capacity Statistics 2025. Abu Dhabi. 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2025/Mar/Renewable-capacity-statistics-2025 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Energy Institute. Statistical Review of World Energy. 2025. Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Our World in Data. Total Solar Capacity. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/installed-solar-pv-capacity?country=OWID_ASI~OWID_NAM~OWID_EUR~OWID_AFR~OWID_SAM~AUS (accessed on 4 November 2025).

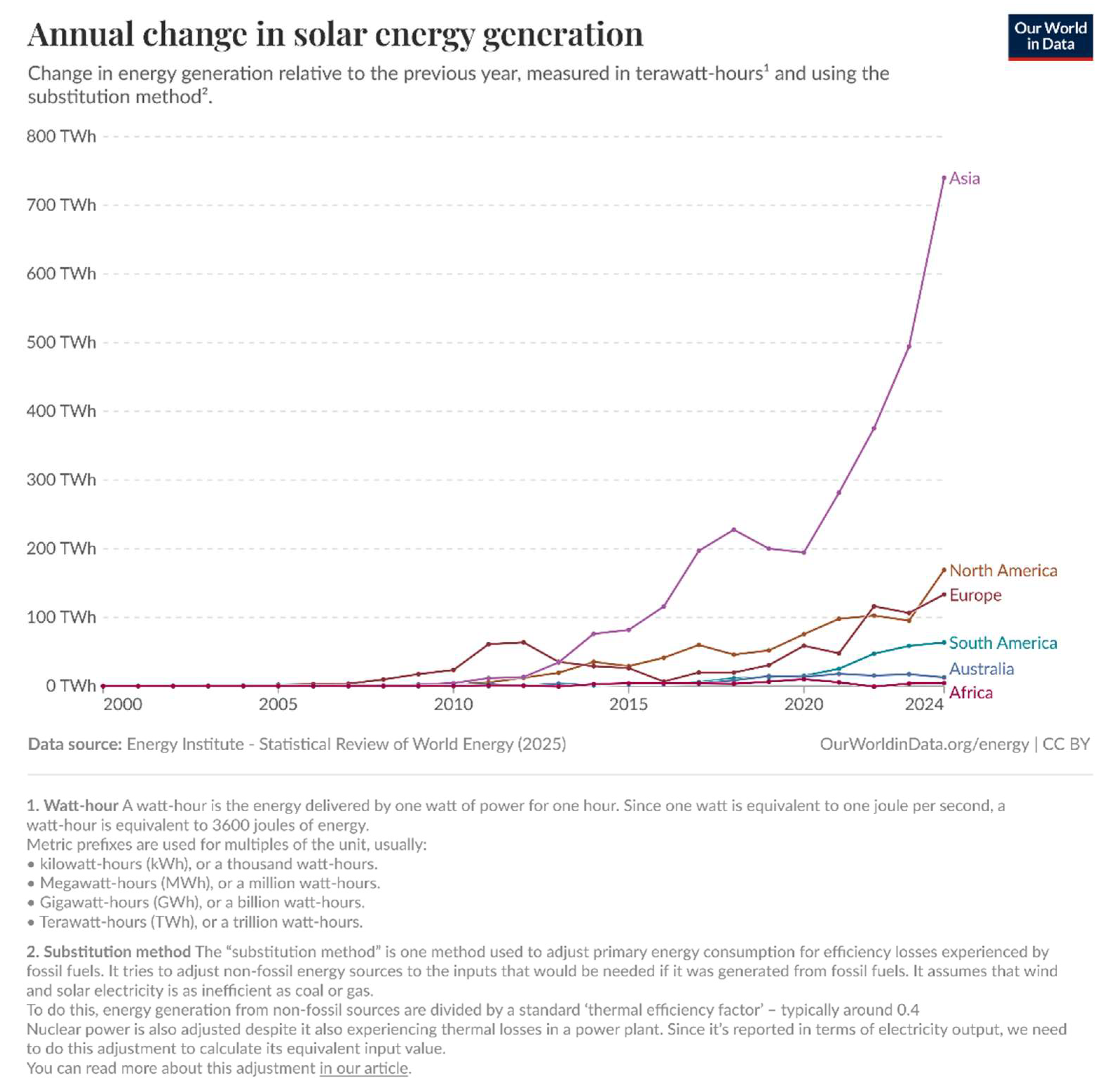

- Our World in Data. Annual Change in Solar Energy Generation. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/annual-change-solar?tab=line&time=2000..latest&country=OWID_EUR~OWID_ASI~OWID_SAM~OWID_NAM~AUS~OWID_AFR (accessed on 4 November 2025).

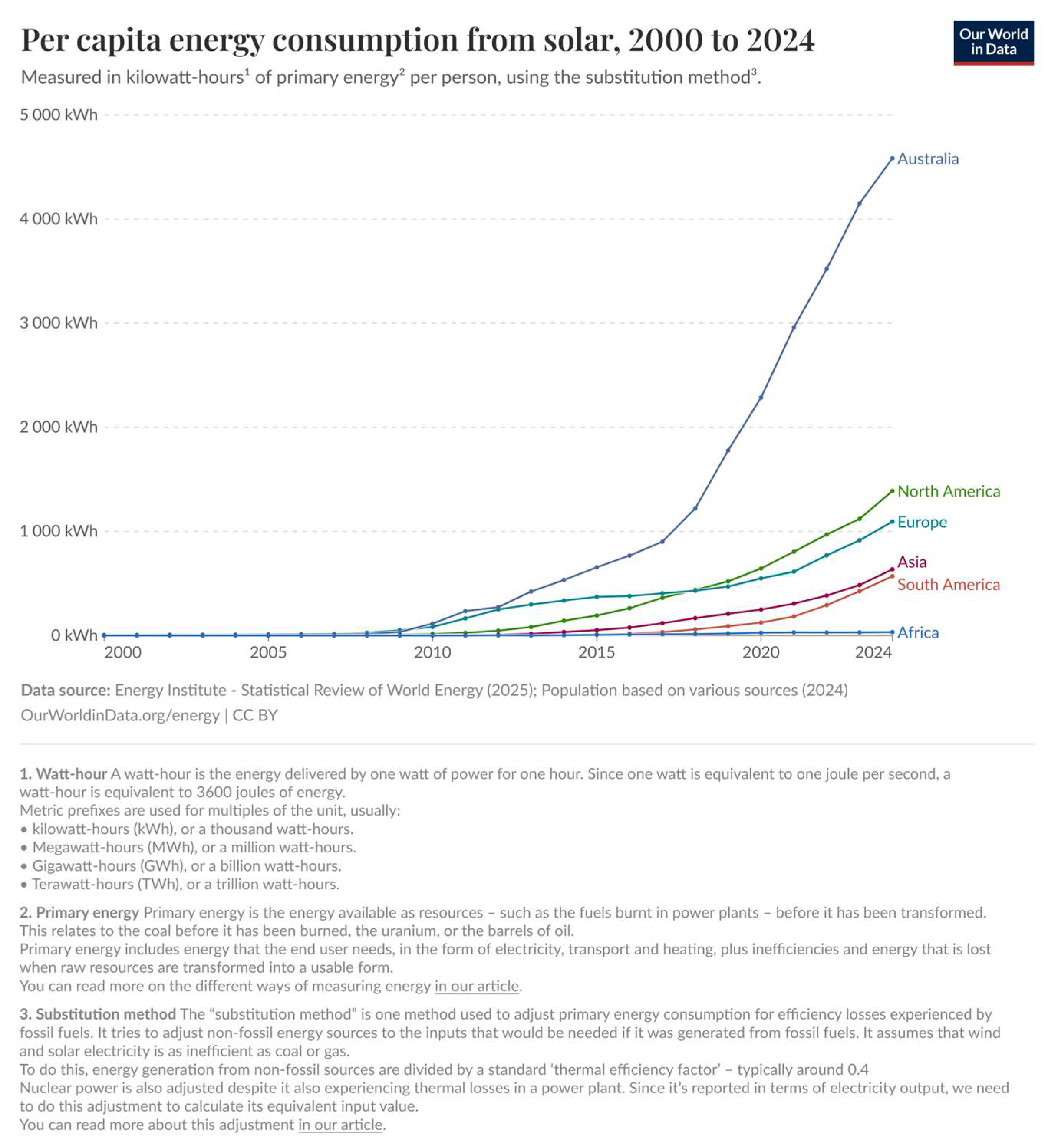

- Our World in Data. Solar Power Consumption Per Capita. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-solar?tab=line&time=2000..latest&country=OWID_EUR~OWID_ASI~AUS~OWID_NAM~OWID_SAM~OWID_AFR (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- IRENA. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2023. International Renewable Energy Agency. 2024. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2024/Sep/IRENA_Renewable_power_generation_costs_in_2023.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

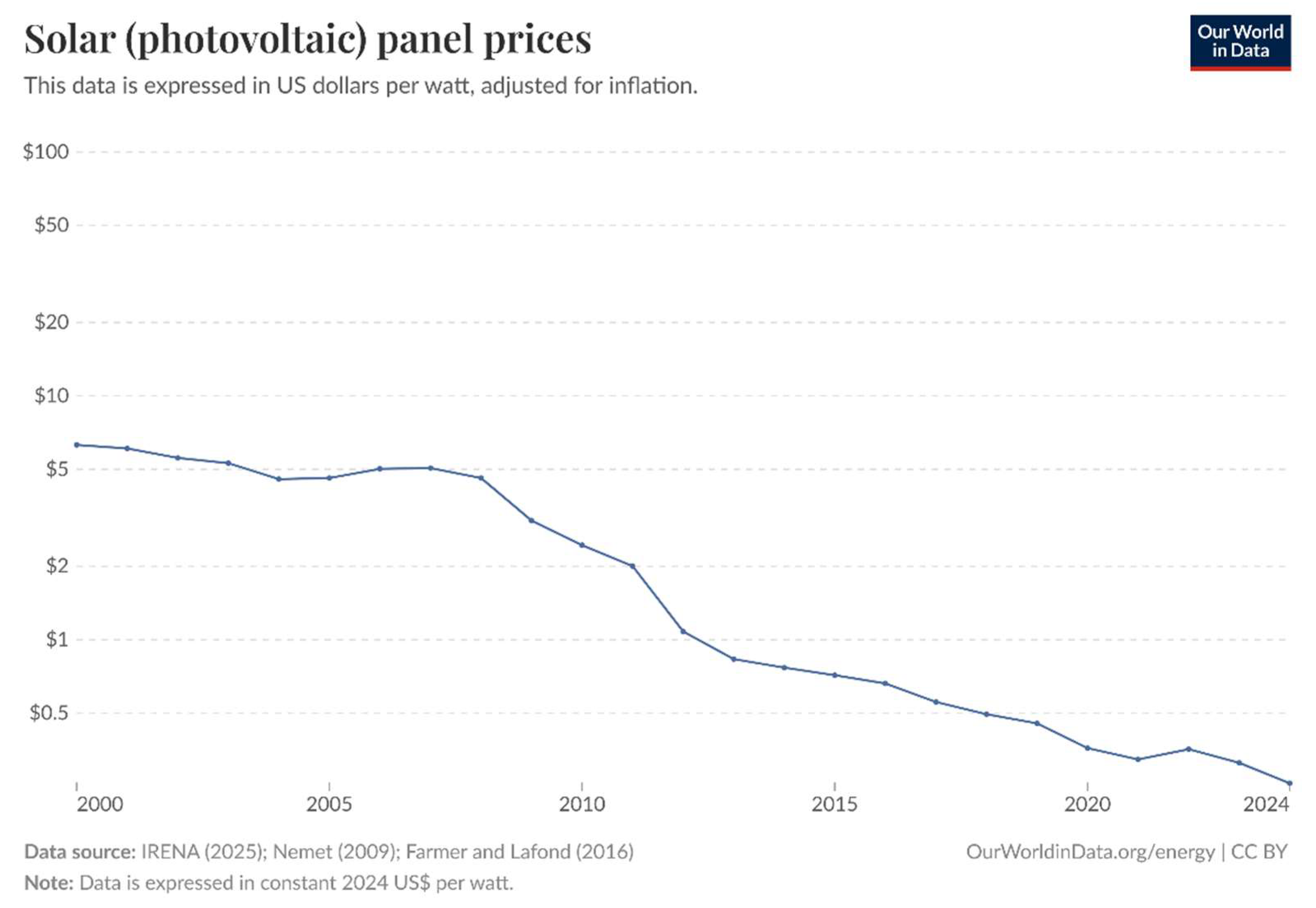

- Our World in Data. Solar Photovoltaic Module Price. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/solar-pv-prices?time=2000..latest (accessed on 4 November 2025).

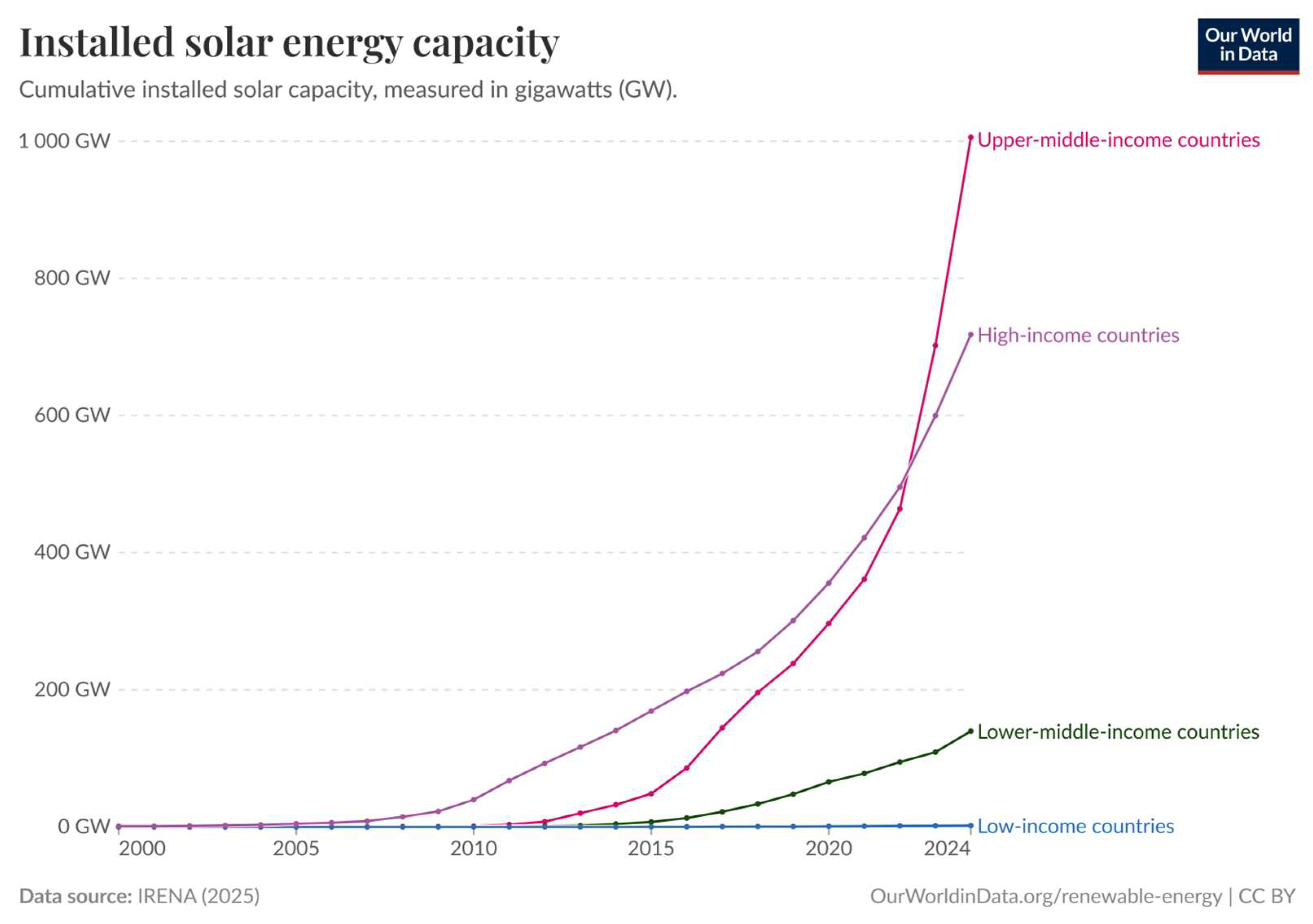

- Our World in Data. Total Solar Capacity by Income Level. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/installed-solar-pv-capacity?country=OWID_LMC~OWID_UMC~OWID_LIC~OWID_HIC (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- IEA PVPS. Snapshot of Global PV Markets. 2025. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Snapshot-of-Global-PV-Markets_2025.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Che, X.-J.; Zhou, P.; Chai, K.-H. Regional policy effect on photovoltaic (PV) technology innovation: Findings from 260 cities in China. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, T.S.; Kumar, P.U.; Ippili, V. Review of global sustainable solar energy policies: Significance and impact. Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M. Missing Data on Energy: Our List of Datasets That Are Needed but Are Not Available. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/energy-missing-data#article-citation (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- EMBER. In 12 Months the Renewables Market has Moved but Governments Have Not. 2024. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2024/11/Report-In-12-months-the-renewables-market-has-moved-but-governments-have-not-2.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- SolarPower Europe. European Market Outlook for Battery Storage 2025–2029. SolarPower Europe. 2025. Available online: https://api.solarpowereurope.org/uploads/SPE_European_Battery_Outlook_2025_62b89db476.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- BSW Solar. The German PV and Battery Storage Market. 2025. Available online: https://www.thesmartere.com/publications/german-pv-and-battery-storage-market (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- EMBER. Global Electricity Review 2025. 2025. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2025/04/Report-Global-Electricity-Review-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- IRENA. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2024. 27 August 2025. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/episode/0lCmND0wxv4iCp386ri4sD?go=1&sp_cid=2815080a6d4828f037a439568dd300e0&utm_source=embed_player_p&utm_medium=desktop&nd=1&dlsi=3acbd6bc2d3b452e (accessed on 14 October 2025).

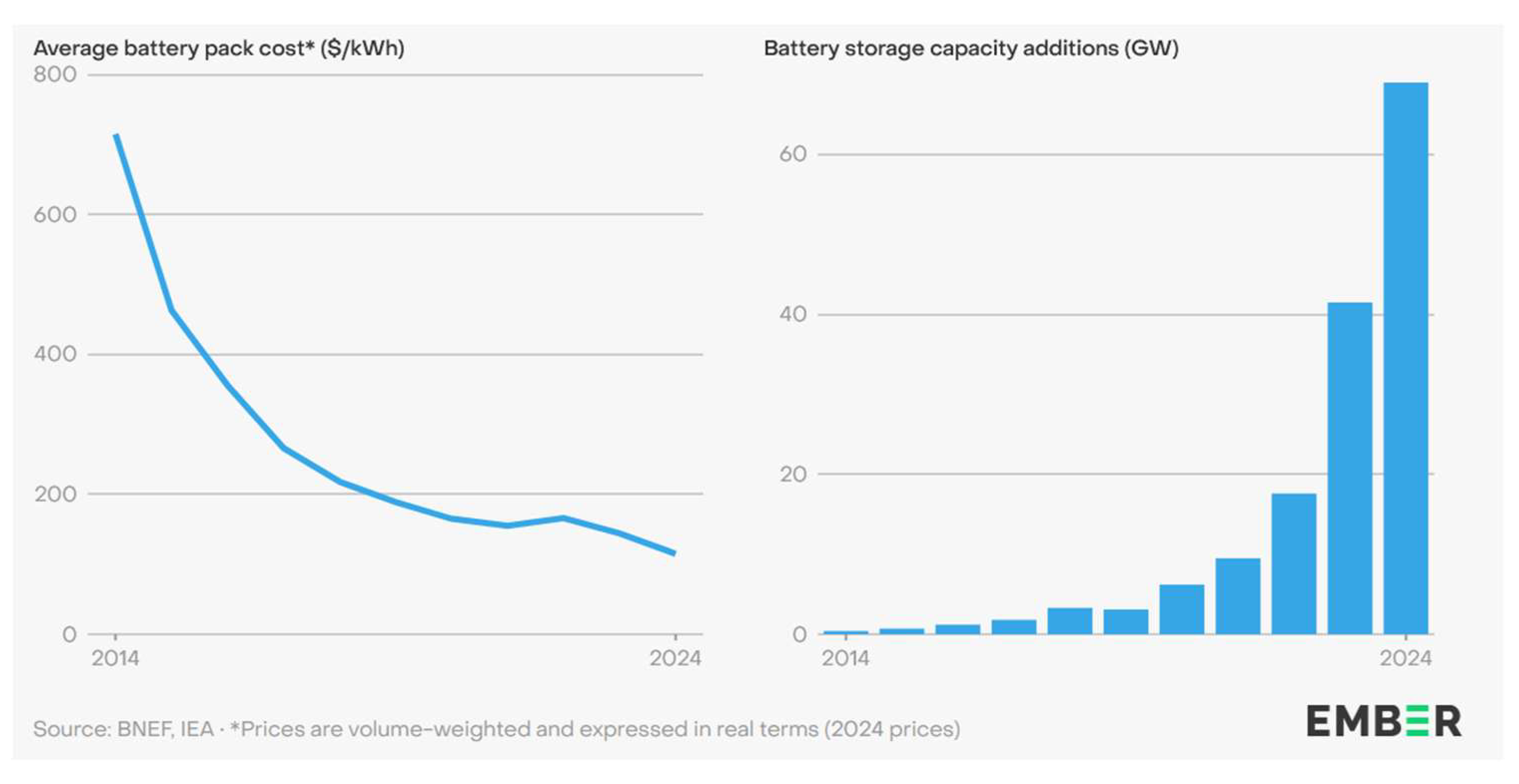

- EMBER. As Battery Prices Have Fallen, Installations Have Skyrocketed. Ember Energy Research. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/latest-insights/global-electricity-review-2025/the-big-picture/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Colthorpe, A. US Energy Storage Installs to ‘Plummet’ with a Repeal of Inflation Reduction Act Tax Credits. Energy Storage News. Available online: https://www.energy-storage.news/us-energy-storage-installs-to-plummet-with-a-repeal-of-inflation-reduction-act-tax-credits/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Ali, A.O.; Elgohr, A.T.; El-Mahdy, M.H.; Zohir, H.M.; Emam, A.Z.; Mostafa, M.G.; Al-Razgan, M.; Kasem, H.M.; Elhadidy, M.S. Advancements in photovoltaic technology: A comprehensive review of recent advances and future prospects. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA PVPS. Analysis of Technological Innovation Systems for BIPV in Different IEA Countries. 2025. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IEA-PVPS-T15-23-2025-REPORT-BIPV-Different-Countries.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Feldman, D.; Ramasamy, V.; Margolis, R. Spring 2025 Solar Industry Update. 2025. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy25osti/95135.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Gonzalez, A. Grid and Storage Readiness is Key to Accelerating the Energy Transition. International Renewable Energy Agency. 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/News/expertinsights/2025/Jan/Grid-and-storage-readiness-is-key-to-accelerating-the-energy-transition (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- WEF. Fostering Effective Energy Transition 2025. World Economic Forum. 2025. Available online: https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Fostering_Effective_Energy_Transition_2025.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- REN21. Renewables Global Status Report 2025. Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century. 2025. Available online: https://www.ren21.net/gsr-2025/downloads/pdf/go/GSR_2025_GO_2025_Full_Report.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- European Patent Office. Advances in Photovoltaics. Technology Trends for Solar Energy. European Patent Office, European Innovation Council. 2025. Available online: https://link.epo.org/web/business/technology-insight-reports/en-epo-technology-insight-report-advances-in-photovoltaics.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- IRENA. Renewable Technology Innovation Indicators: Mapping Progress in Costs, Patents and Standards. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. 2022. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2022/Mar/IRENA_Tech_Innovation_Indicators_2022_.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Islam, S.N.; Saha, S.; Haque, E.; Mahmud, A. Comparative Analysis of Commonly used Batteries for Residential Solar PV Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE PES Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC), Macao, China, 1–4 December 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Electricity Storage and Renewables: Costs and Markets to 2030. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. 2017. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2017/Oct/IRENA_Electricity_Storage_Costs_2017.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Battery Energy Storage Systems Report. Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response. 1 November 2024. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2025-01/BESSIE_supply-chain-battery-report_111124_OPENRELEASE_SJ_1.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Armada, M.; Sánchez, M.J. Potential utilization of battery energy storage systems (BESS) in the major European electricity markets. Appl. Energy 2022, 322, 119512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K.; Ali, M.; Siddique, N.I.; Chand, A.A.; Kumar, N.M.; Dong, D.; Pota, H.R. A review of battery energy storage systems for ancillary services in distribution grids: Current status, challenges and future directions. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 971704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, S.; Hossain, B.; Zamee, M.A.; Hossain, M.; Habib, A. Role of battery energy storage systems: A comprehensive review on renewable energy zones integration in weak transmission networks. J. Energy Storage 2025, 128, 117223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA PVPS. Trends in Photovoltaic Applications 2024. Photovoltaic Power Systems Technology Collaboration Programme, International Energy Agency. 2024. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/IEA-PVPS-Task-1-Trends-Report-2024.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwi4zeW33M6QAxUw8bsIHQVyOLkQFnoECBoQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1YJ8nyeT-V9rgqxsLiD0As (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Grönman, A.; Sihvonen, V.; Honkapuro, S. Emerging and maturing grid-scale energy storage technologies: A bibliometric review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 107, 114996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TESLA. Autobidder. TESLA. Available online: https://www.tesla.com/support/energy/tesla-software/autobidder (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Ullah, H.; Czapp, S.; Szultka, S.; Tariq, H.; Bin Qasim, U.; Imran, H. Crystalline Silicon (c-Si)-Based Tunnel Oxide Passivated Contact (TOPCon) Solar Cells: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Yang, M.; Ru, X.; Wang, G.; Yin, S.; Peng, F.; Hong, C.; Qu, M.; Lu, J.; Fang, L.; et al. Silicon heterojunction solar cells with up to 26.81% efficiency achieved by electrically optimized nanocrystalline-silicon hole contact layers. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Li, C.; Yu, W.; Gao, P. Revolutionizing photovoltaics: From back-contact silicon to back-contact perovskite solar cells. Mater. Today Electron. 2024, 9, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Qiu, S.; Cerrillo, J.G.; Wagner, M.; Kasian, O.; Feroze, S.; Jang, D.; Li, C.; Le Corre, V.M.; Zhang, K.; et al. Fully printed flexible perovskite solar modules with improved energy alignment by tin oxide surface modification. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 7097–7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R. Sungrow Unveils 4.8 MW Modular Inverter. PV Magazine. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/09/10/sungrow-unveils-modular-inverter-battery-energy-storage-systems/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Qu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, F.; Mei, L.; Chen, X.-K.; Zhou, H.; Chu, X.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, X.; et al. Enhanced charge carrier transport and defects mitigation of passivation layer for efficient perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoh, J.H.; Lo, K.-Y.; Hsieh, I.-Y.L. Optimizing urban energy flows: Integrative vehicle-to-building strategies and renewable energy management. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherneva, G.; Filipova-Petrakieva, S. Modeling and Analysis of an Autonomous Photovoltaic System for Laboratory Research. In Proceedings of the 2022 14th Electrical Engineering Faculty Conference (BulEF), Varna, Bulgaria, 14–17 September 2022; pp. 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Labiod, C.; Meneceur, R.; Bebboukha, A.; Hechifa, A.; Srairi, K.; Ghanem, A.; Zaitsev, I.; Bajaj, M. Enhanced photovoltaic panel diagnostics through AI integration with experimental DC to DC Buck Boost converter implementation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamodiya, U.; Kishor, I.; Garine, R.; Ganguly, P.; Naik, N. Artificial intelligence based hybrid solar energy systems with smart materials and adaptive photovoltaics for sustainable power generation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.L.; Woodhouse, M.; Horowitz, K.A.W.; Silverman, T.J.; Zuboy, J.; Margolis, R.M. Photovoltaic (PV) Module Technologies: 2020 Benchmark Costs and Technology Evolution Framework Results. NREL, National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2020. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy22osti/78173.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Mdallal, A.; Yasin, A.; Mahmoud, M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Alami, A.H.; Olabi, A.G. A comprehensive review on solar photovoltaics: Navigating generational shifts, innovations, and sustainability. Sustain. Horiz. 2025, 13, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Bookhart, D.B.; Leung-Shea, M. A high-resolution three-year dataset supporting rooftop photovoltaics (PV) generation analytics. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MRA. Europe Energy Management Systems Market Market Disruption: Competitor Insights and Trends 2025–2033. Market Report Analytics. 2025. Available online: https://www.marketreportanalytics.com/reports/europe-energy-management-systems-market-91019 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Aydin, E.; Allen, T.G.; De Bastiani, M.; Razzaq, A.; Xu, L.; Ugur, E.; Liu, J.; De Wolf, S. Pathways toward commercial perovskite/silicon tandem photovoltaics. Science 2024, 383, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorgian, V.; Koralewicz, P.; Shah, S.; Mendiola, E.; Wallen, R.; Pico, H.V. Photovoltaic Plant and Battery Energy Storage System Integration at NREL’s Flatirons Campus. NREL, National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2022. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy22osti/81104.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Liu, S.; Yang, F.; Li, J.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, T.; Guo, Y. Integration method of large-scale photovoltaic system in distribution network based on improved multi-objective TLBO algorithm. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 1322111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MRA. Future Trends Shaping Photovoltaic Power Generation Monitoring and Control System Growth. Market Report Analytics. 2025. Available online: https://www.marketreportanalytics.com/reports/photovoltaic-power-generation-monitoring-and-control-system-224232# (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Kazem, H.A.; Chaichan, M.T.; Al-Waeli, A.H.; Sopian, K. Recent advancements in solar photovoltaic tracking systems: An in-depth review of technologies, performance metrics, and future trends. Sol. Energy 2024, 282, 112946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.; Singh, D.K.; Alsharif, M.H.; Kim, M.-K. Enhanced MPPT approach for grid-integrated solar PV system: Simulation and experimental study. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 3323–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, M.; Friesen, G.; Jahn, U.; Koentges, M.; Lindig, S.; Moser, D. Identify, analyse and mitigate—Quantification of technical risks in PV power systems. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2022, 31, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.J.D.; Santamaria, R.A. Decoding Solar Adoption: A Systematic Review of Theories and Factors of Photovoltaic Technology Adoption in Households of Developing Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, E.; Scheller, F.; Sloot, D.; Bruckner, T. A meta-analysis of residential PV adoption: The important role of perceived benefits, intentions and antecedents in solar energy acceptance. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 84, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, T.C.; Pandian, S.N. Unveiling the shadows: A qualitative exploration of barriers to rooftop solar photovoltaic adoption in residential sectors. Clean Energy 2024, 8, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA PVPS. Trends in Photovoltaic Applications. Photovoltaic Power Systems Technology Collaboration Programme, International Energy Agency. 2025. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/trends_reports/trends-2025/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Liu, H.; Xiang, L.; Gao, P.; Wang, D.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Shi, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Y. Improvement Strategies for Stability and Efficiency of Perovskite Solar Cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, T.N.; Minh, P.V.; Trung, K.D.; Anh, T.D. Study on Performance of Rooftop Solar Power Generation Combined with Battery Storage at Office Building in Northeast Region, Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hariri, M.; Youssef, T.A.; Mohammed, O.A. On the Implementation of the IEC 61850 Standard: Will Different Manufacturer Devices Behave Similarly under Identical Conditions? Electronics 2016, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A.; Omer, S.; Su, Y.; Mohamed, E.; Alotaibi, S. The Technical Challenges Facing the Integration of Small-Scale and Large-scale PV Systems into the Grid: A Critical Review. Electronics 2019, 8, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Li, W.; Hussain, R.; He, X.; Williams, B.W.; Memon, A.H. Overview of Current Microgrid Policies, Incentives and Barriers in the European Union, United States and China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topics | Web of Science | Scopus |

|---|---|---|

| Cells within panels | Ashraf et al. [27] Guesnay et al. [28] Huang et al. [29] Jiao et al. [30] Khan et al. [31] Kurokawa [32] Matei at al. [33] Teo et al. [34] Teomete [35] Wang et al. [36] | Suchan et al. [37] Odabaşı Özer & Yıldırım [38] Singareddy et al. [39] Pagliai & Brambilla [40] Radisavljevic-Gajic et al. [41] Matei et al. [33] |

| Panels (system level) | Liu et al. [42] Yokoyama [43] Ponrekha et al. [44] | Odabaşı Özer & Yıldırım [38] Singareddy et al. [39] Pagliai & Brambilla [40] Suchan et al. [37] Novo et al. [45] Radisavljevic-Gajic et al. [41] |

| Integration with building infrastructure | Yokoyama [43] Ponrekha et al. [44] Ashraf et al. [27] | Matei et al. [33] Romero et al. [46] Novo et al. [45] |

| Market conditions | Ashraf et al. [27] Kurokawa [32] Liu et al. [42] Ponrekha et al. [44] Yokoyama [43] Guesnay et al. [28] Huang et al. [29] Jiao et al. [30] Khan et al. [31] Wang et al. [36] Teo et al. [34] | Matei et al. [33] Romero et al. [46] Pagliai & Brambilla [40] Novo et al. [45] Suchan et al. [37] Singareddy et al. [39] |

| Stage of S-Curve | Indicators | Presence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 Infancy | The technical system is not present on the market or exists only in small niche markets. | ||

| The MPV behavior is flat. | |||

| The technical system adopts components from other technical systems. | |||

| The technical system integrates with elements of the supersystem. | |||

| The technical system utilizes resources that were not originally designed for it. | |||

| Initially, changes within the system occur rapidly, but their frequency gradually decreases. | |||

| There is a large number of system variants, of which only one enters production. | |||

| Improved functionality significantly reduces costs. | |||

| Costs exceed revenues. | |||

| Transitional Stage | The technical system is ready for market introduction but remains sensitive to external factors. | ||

| The MPV is increasing very rapidly. | |||

| The first successful implementations of the system have appeared in various areas. | |||

| The system begins to enter the market through niche sectors. | |||

| Stage 2 Rapid growth | The technical system is present on the market. | ||

| The MPV increases sharply. | |||

| The technical system enters mass production. | |||

| Multiple product variants appear, sharing the same main function but differing in design. | |||

| Various product variants emerge with new applications. | |||

| The technical system acquires additional functionalities that generate new areas of application for the product. | |||

| At the end of this stage, the number of system designs and variants decreases. | |||

| The supersystem adapts to the technical system. | |||

| The technical system begins to use resources that have been specifically created for it. | |||

| Stage 3 Maturity | The presence of the technical system on the market is stable. | ||

| The MPV is flat—changing very slowly. | |||

| The technical system has reached certain limits of development. | |||

| The technical system has found new applications and market niches. | |||

| Gradual improvement of the technical system requires disproportionately high expenditures. | |||

| The technical system consumes specialized resources. | |||

| The supersystem includes many components that have been specifically designed for the technical system. | |||

| A large number of product variants appear, but they concern design rather than functionality. | |||

| The technical system gains additional functions that are not related to the performance of its main function. | |||

| Stage 4 Decline | The technical system remains on the market. | ||

| The MPV decreases. | |||

| The technical system has lost its practical value but continues to exist as sports equipment, toys, tourist attractions, or decorative items. | |||

| The system satisfies the needs of a niche market. | |||

| The system can be integrated into the supersystem. | |||

| TESE | 1st Stage | Transitional Stage | 2nd Stage | 3rd Stage | 4th Stage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend of S-curve evolution | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Trend of increasing value | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||

| • | Trend of increasing system completeness | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| · | Trend of decreasing human involvement | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||

| • | Trend of transition to the supersystem | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| • | Trend of increasing degree of trimming | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| • | Trend of flow enhancement | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| • | Trend of increasing coordination | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| · | Trend of uneven development of system component | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| · | Trend of increasing controllability | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| · | Trend of increasing dynamization | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Region | Share * of Installed PV Panel Capacity in 2024 | Forecasted Share * of Installed PV Panel Capacity in 2029 | Installed PV Capacity in 2024 (GW) | Forecasted Installed PV Capacity in 2029 ** (GW) | Total Cumulative PV Capacity in 2024 (GW) | Forecasted Total Cumulative PV Capacity in 2029 ** (GW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 55% | 50% | 329 GW | ~465 GW | 985 GW | ~2800–3000 GW |

| APAC without China | 15% | 20% | 90 GW *** | ~186 GW | 415 GW **** | ~1000–1200 GW |

| Europe | 14% | 13% | 82.1 GW | ~121 GW | 407 GW | ~800–900 GW |

| Americas | 14% | 10% | 82.9 GW | ~93 GW | 350 GW | ~600–700 GW |

| Middle East and Africa | 2% | 7% | 14.5 GW | ~65 GW | 63 GW | ~400–500 GW |

| Stage | Indicators | Presence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 2 Rapid growth | The technical system is present on the market. | YES | |

| The MPV increases sharply. | In laboratory—YES; in the commercial market slower | ||

| The technical system enters mass production. | PARTIALLY | ||

| Multiple product variants appear, sharing the same main function but differing in design. | YES | ||

| Various product variants emerge with new applications. | YES | ||

| The technical system acquires additional functionalities that generate new areas of application for the product. | YES | ||

| At the end of this stage, the number of system designs and variants decreases. | YES | ||

| The supersystem adapts to the technical system. | PARTIALLY | ||

| The technical system begins to use resources that have been specifically created for it. | PARTIALLY | ||

| Stage 3 Maturity | The presence of the technical system on the market is stable. | YES | |

| The MPV is flat—changing very slowly. | NO | ||

| The technical system has reached certain limits of development. | NO | ||

| The technical system has found new applications and market niches. | PARTIALLY | ||

| Gradual improvement of the technical system requires disproportionately high expenditures. | NO | ||

| The technical system consumes specialized resources. | YES | ||

| The supersystem includes many components that have been specifically designed for the technical system. | PARTIALLY | ||

| A large number of product variants appear, but they concern design rather than functionality. | NO | ||

| The technical system gains additional functions that are not related to the performance of its main function. | YES | ||

| Stage | Indicators | Presence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 2 Rapid growth | The technical system is present on the market. | YES | |

| The MPV increases sharply. | In laboratory—YES; in the commercial market slower | ||

| The technical system enters mass production. | PARTIALLY | ||

| Multiple product variants appear, sharing the same main function but differing in design. | YES | ||

| Various product variants emerge with new applications. | YES | ||

| The technical system acquires additional functionalities that generate new areas of application for the product. | YES | ||

| At the end of this stage, the number of system designs and variants decreases. | YES | ||

| The supersystem adapts to the technical system. | PARTIALLY | ||

| The technical system begins to use resources that have been specifically created for it. | PARTIALLY | ||

| Stage 3 Maturity | The presence of the technical system on the market is stable. | YES | |

| The MPV is flat—changing very slowly. | NO | ||

| The technical system has reached certain limits of development. | NO | ||

| The technical system has found new applications and market niches. | PARTIALLY | ||

| Gradual improvement of the technical system requires disproportionately high expenditures. | NO | ||

| The technical system consumes specialized resources. | YES | ||

| The supersystem includes many components that have been specifically designed for the technical system. | PARTIALLY | ||

| A large number of product variants appear, but they concern design rather than functionality. | NO | ||

| The technical system gains additional functions that are not related to the performance of its main function. | YES | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gorączkowska, J.; Moczulska, M.; Yatsunenko, S. TESE-Informed Evolution Pathways for Photovoltaic Systems: Bridging Technology Trajectories and Market Needs. Energies 2025, 18, 6216. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236216

Gorączkowska J, Moczulska M, Yatsunenko S. TESE-Informed Evolution Pathways for Photovoltaic Systems: Bridging Technology Trajectories and Market Needs. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6216. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236216

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorączkowska, Jadwiga, Marta Moczulska, and Sergey Yatsunenko. 2025. "TESE-Informed Evolution Pathways for Photovoltaic Systems: Bridging Technology Trajectories and Market Needs" Energies 18, no. 23: 6216. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236216

APA StyleGorączkowska, J., Moczulska, M., & Yatsunenko, S. (2025). TESE-Informed Evolution Pathways for Photovoltaic Systems: Bridging Technology Trajectories and Market Needs. Energies, 18(23), 6216. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236216