1. Introduction

The increasing commitment to lowering fossil fuel dependence and reducing local emissions has driven extensive research on electric vehicles (EVs), fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), and hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs). In parallel, a wide range of energy storage systems (ESS) has been investigated. Different storage technologies are characterized either by high power density (PDES) or by high energy density (EDES). To exploit the strengths of both, hybrid energy storage systems (HESS) have been introduced in EV applications [

1,

2,

3,

4], typically combining PDES devices such as supercapacitors with EDES solutions such as batteries.

FCEVs are particularly promising, since hydrogen refueling is significantly faster than recharging a battery and generally ensures a longer driving range compared to battery electric vehicles [

5,

6,

7]. However, fuel cells exhibit a slow dynamic response, making it essential to pair them with a battery storage system. Although hydrogen refueling is convenient in terms of time, it requires specific and costly infrastructures; for this reason, some FCEVs are also designed as plug-in versions, allowing direct recharging of the onboard battery from the grid [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

When fuel cells are coupled with other energy storage units, bidirectional DC-DC converters are required to connect the auxiliary storage to the DC-link of the traction drive. In parallel, a unidirectional boost-type DC-DC converter is conventionally employed to interface the fuel cell stack. In HESS configurations, where multiple DC sources need to share a common DC bus, a single multi-input converter often represents a more efficient solution compared to deploying several parallel single-input converters. For instance, ref. [

13] presented a newly developed multi-input boost topology, derived from earlier works, capable of enabling bidirectional power transfer while achieving higher efficiency levels than traditional approaches.

In recent years, significant progress has been achieved in the development of advanced Energy Management Systems (EMS) [

14,

15,

16] that coordinate the operation of diverse storage devices such as batteries and supercapacitors [

17,

18,

19,

20] and also when integrated with fuel cells [

3]. However, most studies available in the literature rely on type-approval driving cycles. While these cycles are useful for providing a standardized comparison framework, their profiles are typically less energy demanding and therefore may not accurately represent the real power requirements of a vehicle in operation.

To address this gap, the present work investigates three powertrain architectures—battery-only, supercapacitor-only, and a combined battery–supercapacitor system—applied to both conventional and plug-in FCEVs. A dedicated EMS has been designed to manage power distribution among the sources. The evaluation is conducted under an actual urban driving mission with an experimentally measured speed–altitude profile, enabling a more realistic assessment of energy consumption. The evaluation is carried out exploiting an accurate vehicle model in the MATLAB/Simulink environment.

2. System Model

The next section is devoted to a presentation of the mathematical formulation adopted for the system under study. In this framework, the modeling approach is based on quasi-stationary representations. This assumption is justified by the fact that the transient dynamics of the individual components, although present, have only a marginal influence on the overall energy balance and therefore can be neglected without compromising the accuracy of the analysis. As a matter of fact, given the vehicle’s inertia, the dynamics of the electrical components can be considered negligible with respect to the vehicle dynamics. Consequently, all loss mechanisms are assessed by considering a sequence of steady-state operating points that adequately describe the actual working conditions of the system.

Within this formulation, the total resistive force that counteracts the forward motion of the vehicle is expressed as follows:

where

m is the vehicle’s mass [kg],

g denotes gravitational acceleration [m/s

2],

α [°] represents the road inclination,

Cr is the rolling resistance coefficient,

ρ stands for air density [kg/m

3],

Cx is the aerodynamic drag coefficient,

S is the vehicle’s frontal area [m

2], and

v corresponds to its speed [m/s]. After determining the resistive force, the resulting torque can then be computed:

In this context,

Rwheel represents the wheel radius, while

τ denotes the fixed transmission ratio. The vehicle’s speed can be determined using the well-established equation:

where

Here,

Tmotor [N·m] represents the motor torque, which becomes negative during regenerative braking.

J denotes the moment of inertia referenced to the motor shaft, while

Jmotor corresponds to the moment of inertia of the electric motor. The motor torque is controlled using a PI regulator, with its limits varying based on angular speed according to the torque constraints of the PMSM in the flux-weakening region.

Urban Mission and Vehicle Parameters

In this study, the reference vehicle selected for the simulations corresponds to a medium-size passenger car, whose main technical and geometric parameters are summarized in

Table 1. These data serve as the foundation for the mathematical representation of the system and ensure that the subsequent analyses are linked to a realistic case study rather than a purely theoretical framework.

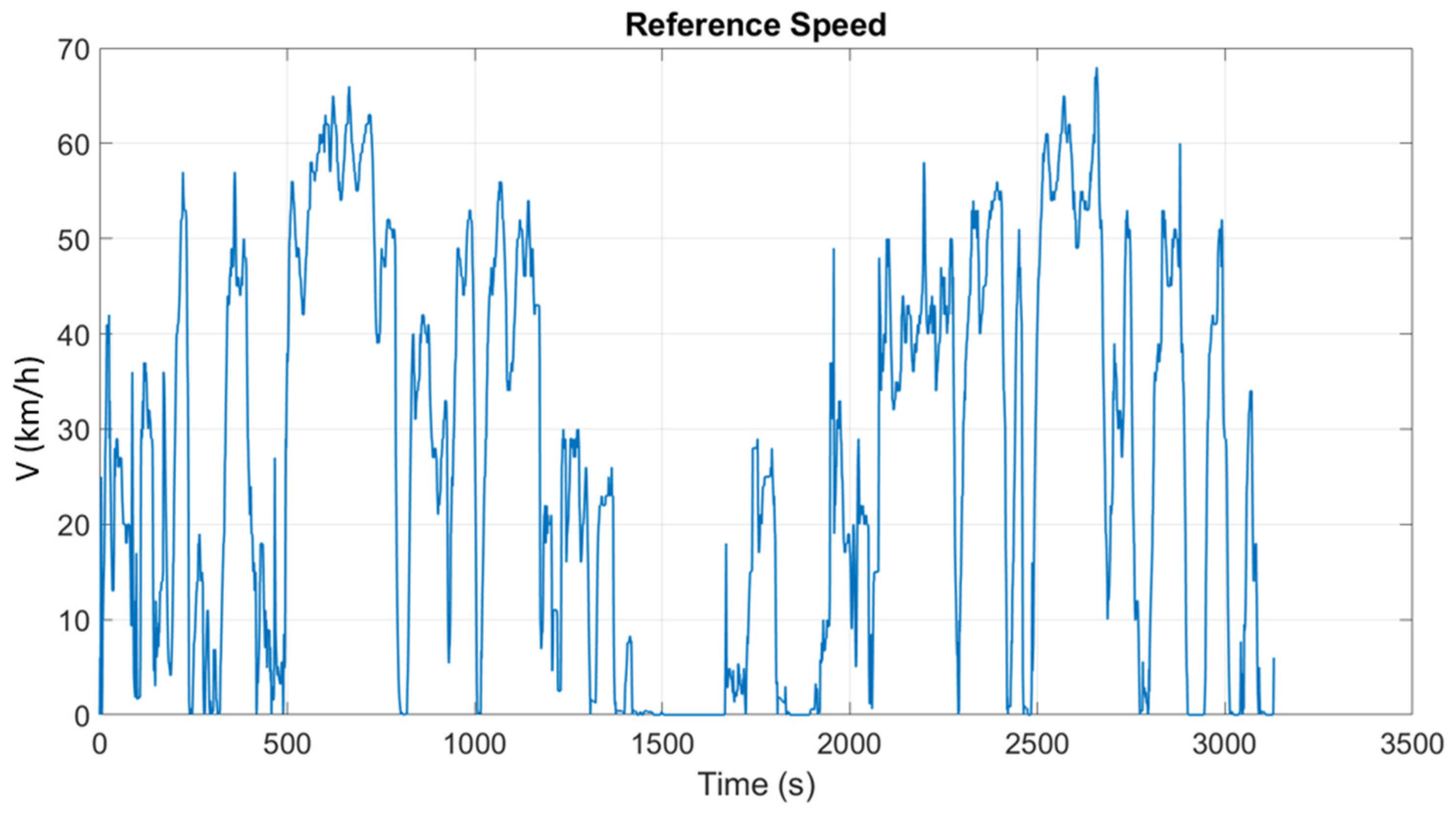

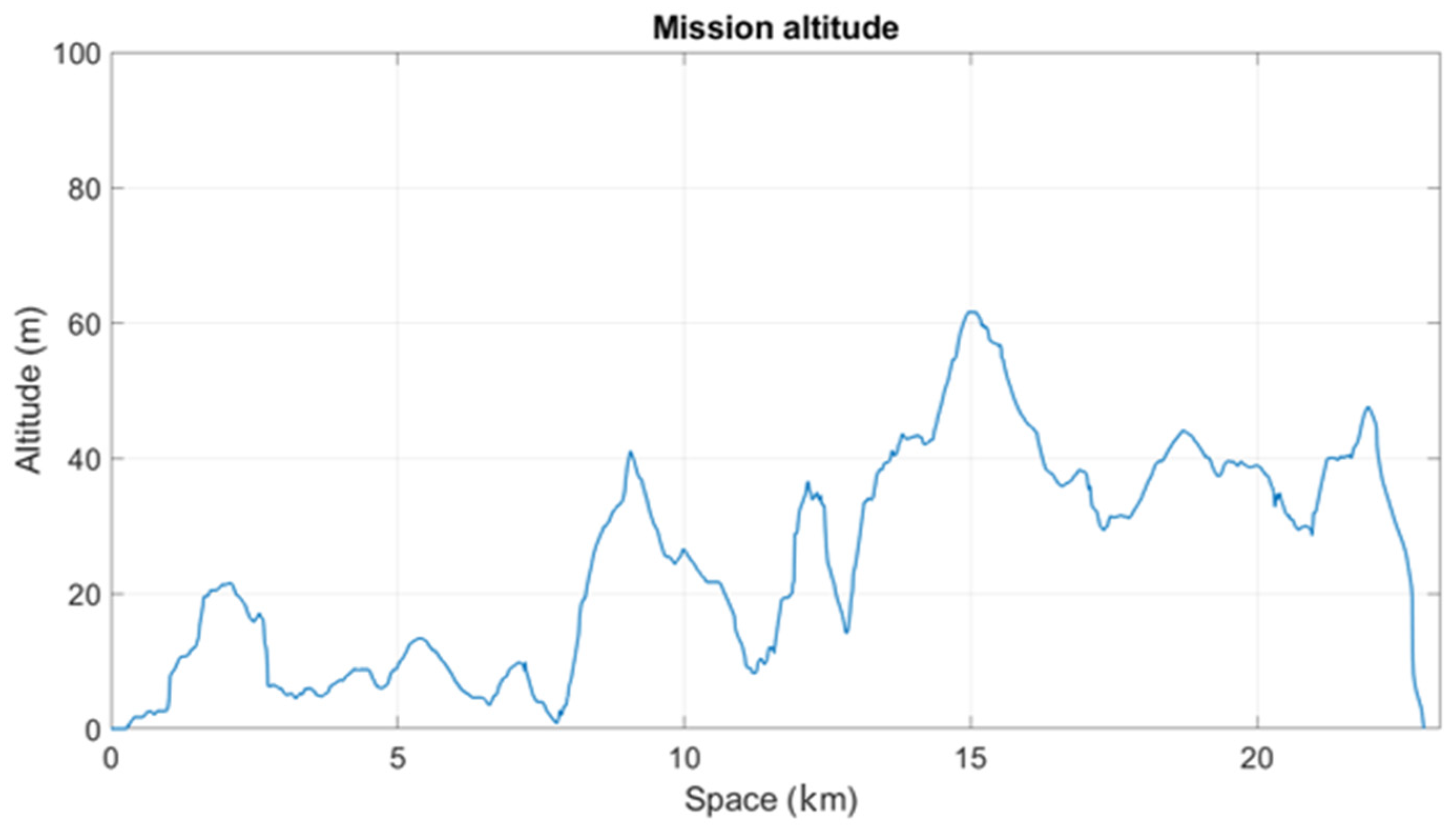

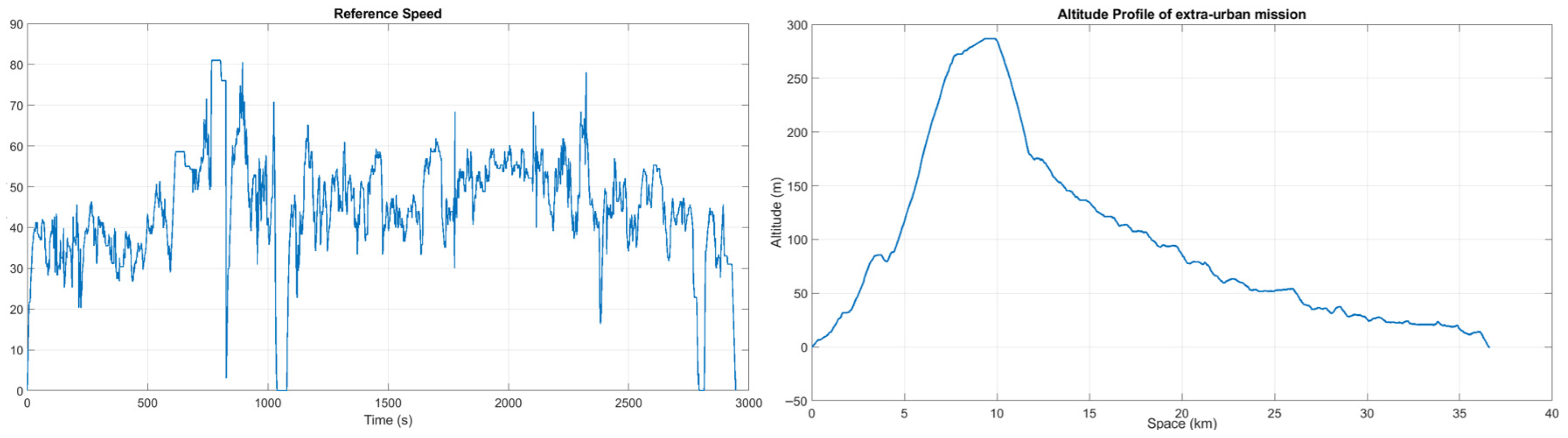

To assess the energy consumption associated with the different powertrain configurations under investigation, an urban driving mission has been considered as the operational scenario. Specifically, the test route is located in the city of Genoa, Italy, an environment characterized by a combination of dense traffic conditions, frequent accelerations and decelerations, and notable variations in road elevation. Such conditions make this route particularly suitable for evaluating the performance of hybrid energy storage solutions, since both speed fluctuations and altitude changes strongly influence the instantaneous power demand of the vehicle.

The reference data used to model the mission consist of two main input profiles: the vehicle speed profile and the road altitude profile. Both of these were experimentally measured during an actual driving session carried out on the selected route and subsequently processed to serve as inputs for the mathematical model. The resulting speed trace and elevation profile are illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, respectively, and represent the benchmark against which the energy consumption of the considered configurations has been evaluated.

As previously stated at the beginning of

Section 2, a dedicated mathematical model has been established to describe the operating behavior of the system. Within this framework, Equations (1)–(5) have been implemented in order to compute, at each time instant, the power demand imposed on the different energy storage devices. This approach allows for the evaluation of the dynamic interactions among the subsystems and provides a detailed picture of how the required energy is distributed during the driving mission.

In addition to the fundamental equations, a feedback control loop has been incorporated into the simulation environment. The role of this controller is to adjust the torque and rotational speed of the electric motor so that the actual vehicle speed faithfully tracks the reference speed profile previously illustrated in

Figure 1.

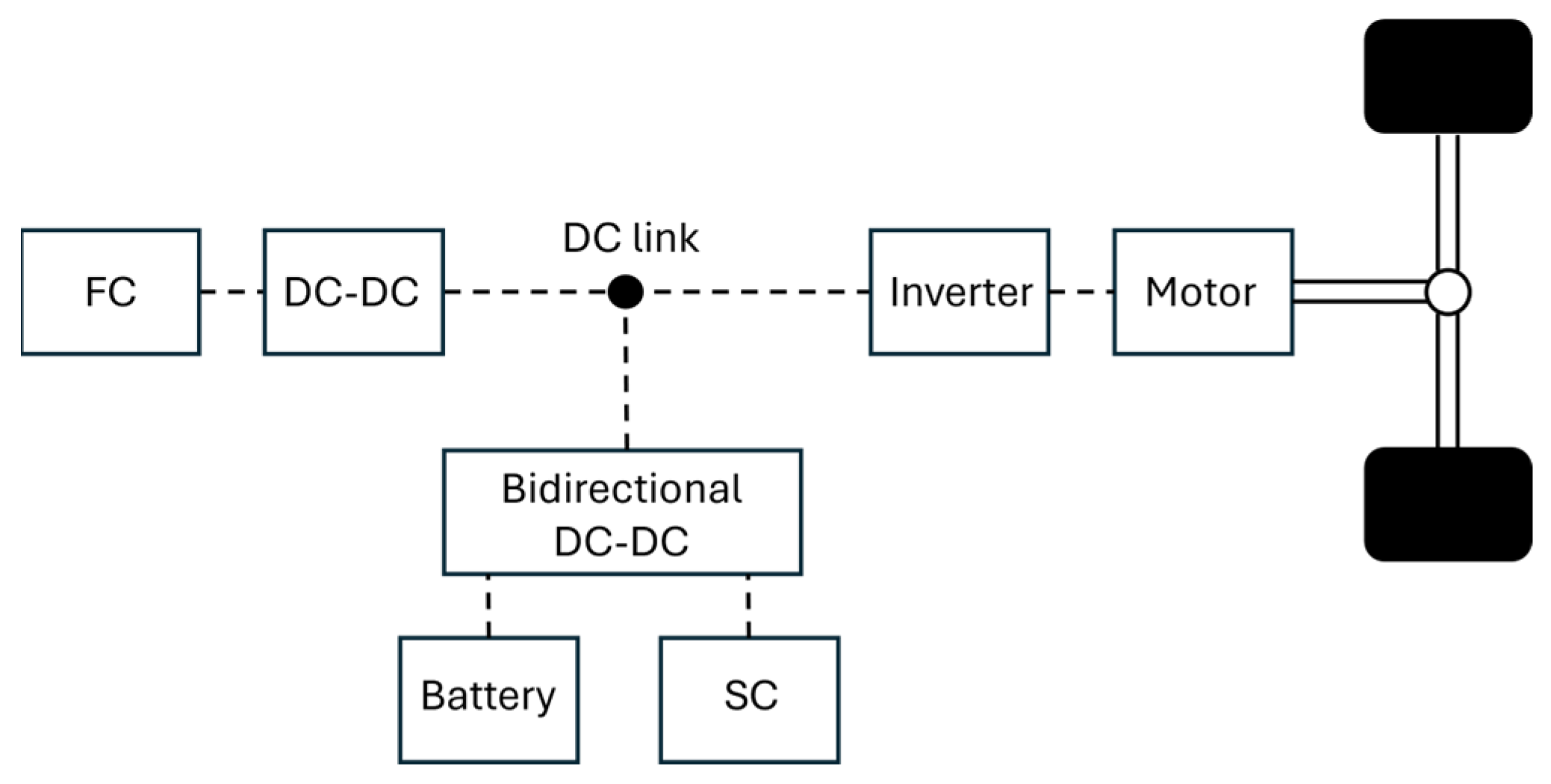

The overall architecture of the considered powertrain is depicted in

Figure 3. The diagram illustrates the configuration of a fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) in which the fuel cell stack operates in conjunction with both a conventional battery storage system and a supercapacitor bank. The hybridization of these three energy sources enables the exploitation of their complementary characteristics: the fuel cell provides the baseline energy supply, the battery covers medium-term energy fluctuations, and the supercapacitor manages rapid power transients. Such a layout highlights the potential benefits of combining different storage technologies to optimize efficiency, improve dynamic performance, and extend the lifetime of the individual components.

A bidirectional DC-DC converter is required to connect either the battery or the supercapacitor to the shared DC-link, enabling the storage systems to be recharged during regenerative braking. The efficiency characteristics of the DC-DC converters, as well as those of the inverter and the electric motor, have been incorporated into this study by using contour efficiency maps [

21].

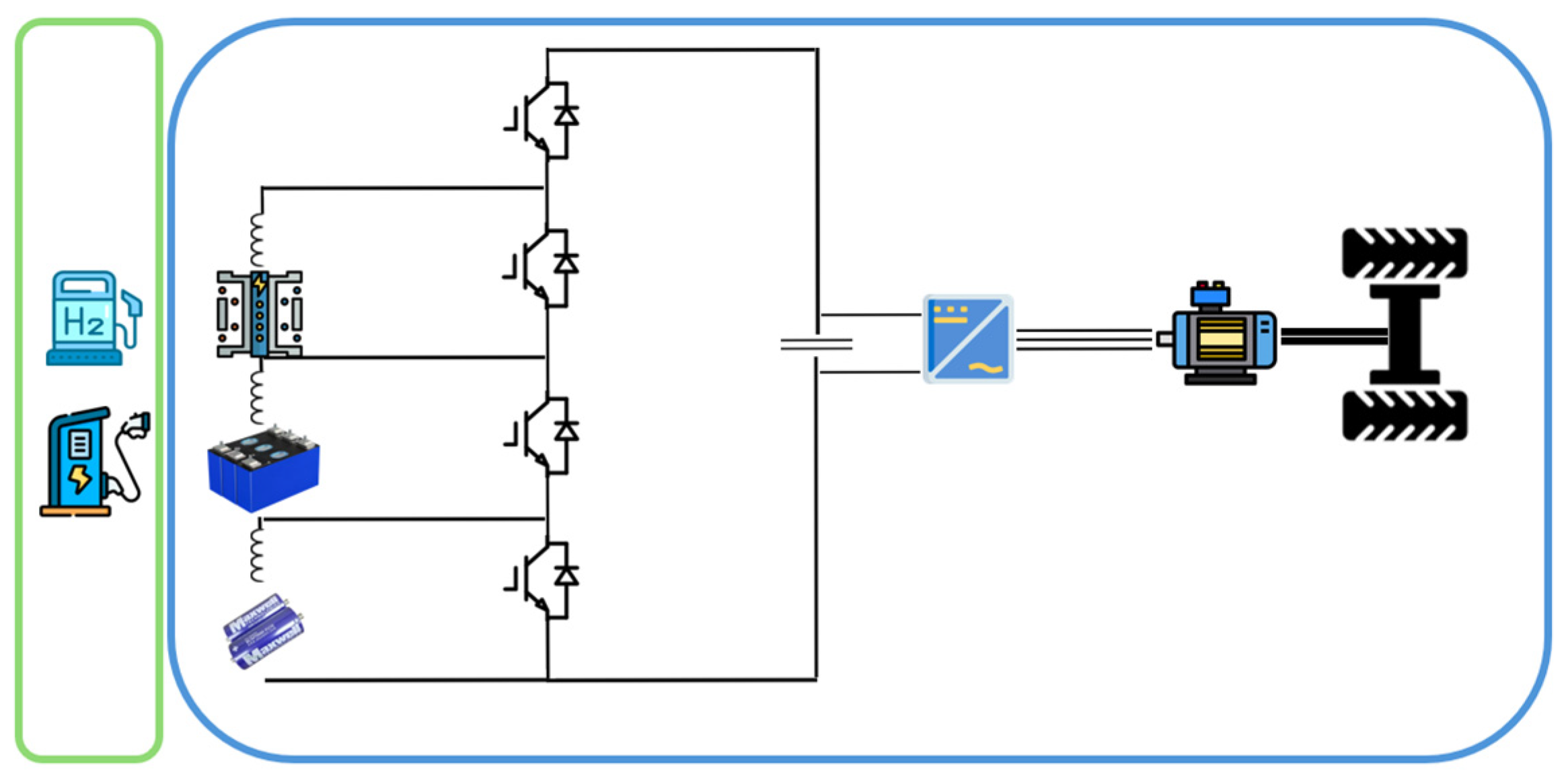

As highlighted in the introduction, the recent technical literature has proposed an innovative multi-input bidirectional DC-DC boost converter, which is schematically illustrated in

Figure 4. This advanced topology enables the independent control of multiple DC sources, allowing them to interface with a higher-voltage DC-link while utilizing only

n + 1 switching devices for

n sources. Such a design not only reduces the overall complexity of the system but also improves efficiency and facilitates the integration of hybrid energy storage systems, such as the combination of batteries and supercapacitors in FCEVs, by ensuring a flexible and high-performance power distribution architecture. It has to be mentioned that, for the simulation results section of this work, the multi-input bidirectional converter presented in [

13] has been considered, and its efficiency has been taken into account in the model.

3. Battery and Supercapacitor Modeling

3.1. Battery Model

In the context of comparing the energy consumption of a fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) powertrain equipped with battery storage, supercapacitor storage, and a hybrid battery–supercapacitor configuration, accurately modeling the efficiency of the storage systems is essential. For the battery case, the performance data have been taken directly from the manufacturer’s datasheet of the selected Li-NMC cells (EVE INP58P, 3.62 V, and 58 Ah) [

22]. According to the provided specifications, the round-trip efficiency depends strongly on the charge/discharge rate: it reaches about 98% at 0.2 C, decreases to around 94.5% at 1 C, and further drops to approximately 89.5% at 2 C. These values highlight the sensitivity of lithium-ion battery efficiency to current levels and provide a reliable basis for integrating realistic efficiency behavior into the overall powertrain model.

Starting from the efficiency values at different C-rates, an equivalent series resistance (ESR) was derived in order to evaluate the internal losses of the cells. The battery was therefore represented by an equivalent circuit consisting of an ideal voltage source in series with the ESR. The voltage source itself was expressed as a function of the state of charge (SOC), and its behavior was also parameterized using the information provided in the manufacturer’s datasheet. This simplified representation allows the battery to be realistically integrated into system-level simulations, while keeping the model computationally efficient and directly linked to physical performance data.

3.2. Supercapacitor Model

Supercapacitors are widely acknowledged for their very high efficiency, primarily resulting from their extremely low internal equivalent series resistance (ESR), which significantly reduces energy losses during operation. In contrast to batteries, where energy storage is achieved through chemical reactions, supercapacitors rely on electrostatic mechanisms. This fundamental distinction enables them to sustain rapid charge and discharge cycles and contributes to their considerably longer operational lifespan. Nevertheless, a major limitation of this technology is its relatively low energy density, which restricts the amount of energy that can be stored per unit of mass or volume. In the present study, the supercapacitor storage system has been modeled as an ideal capacitor connected in series with a resistance. For this purpose, the Maxwell BCAP3000 P300 K04/K05 cells have been selected [

23], characterized by a nominal voltage of 3 V, a capacitance of 3000 F, an ESR of 0.13 mΩ, and a maximum current rating of 220 A. It is worth noting that more refined models can be implemented, both for the battery and the supercapacitor, such as a 1-RC Thevenin equivalent circuit in order to capture the transient voltage drop of the battery, or a lumped thermal model for both the battery and supercapacitor to describe the cell temperature evolution. Given the focus on mission-level energy comparison, it has been verified from the literature data that such refinements only marginally influence total energy consumption under the studied conditions. A detailed dynamic thermal model is planned for future work.

3.3. Fuel Cell Model

In this study, a M240 Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) fuel cell stack produced by Axane has been selected as the reference device [

24]. The stack is characterized by a rated power of 10 kW, a maximum output voltage of 34 V, and a maximum current capacity of 500 A, while also offering a compact and lightweight design that makes it suitable for vehicular applications. The efficiency profile of PEM fuel cell stacks typically follows a well-known trend: the highest efficiency values, in the range of 50–60%, are generally achieved when the stack operates at about 25–30% of its rated power. At operating points below this range, efficiency is reduced due to activation losses, whereas at higher loads, ohmic losses together with thermal effects become dominant, leading to a progressive efficiency drop, with values not exceeding 40–50% when running close to rated power.

Considering these characteristics, in this work, the stack is controlled to deliver a constant power output of about 3 kW, corresponding to the average power demand observed during the mission. In order to reproduce its behavior in the overall system simulation, the efficiency of the fuel cell has been represented through a lookup table as a function of the delivered power. Furthermore, a control strategy has been implemented to adjust the fuel cell power contribution dynamically, depending on the state of charge (SOC) of the battery and the voltage level of the supercapacitor, thus ensuring proper energy management during operation. It is noted that transient penalties such as oxygen starvation, purge/water management, start/stop events, and temperature-dependent efficiency are not explicitly modeled in the current study. These effects can influence short-term performance and efficiency but are expected to have limited impact under the examined conditions.

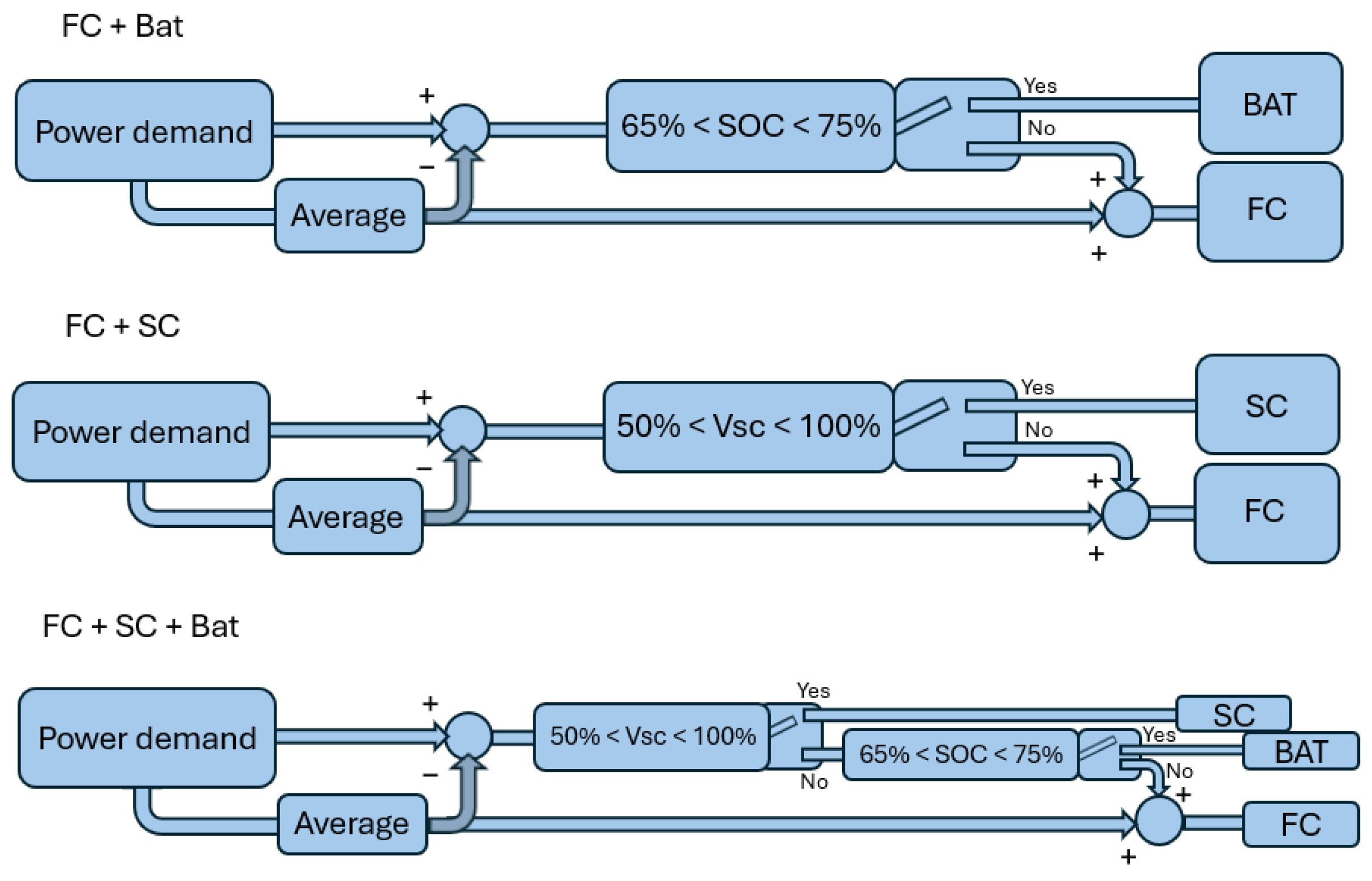

4. Energy Management System

As mentioned, this work focuses on the analysis and comparison of different FCEV powertrain configurations. In particular, three setups have been investigated: fuel cell with a battery, fuel cell with a supercapacitor, and the hybrid arrangement combining the fuel cell, battery, and supercapacitor. In all cases, the auxiliary storage system plays a crucial role in handling power fluctuations and regenerative braking, allowing the fuel cell to operate at quasi-constant power.

In conventional fuel cell vehicles, the energy management strategy is relatively straightforward. The fuel cell is controlled to supply the average power required by the driving mission, while the auxiliary storage acts as a buffer, absorbing or releasing power during transients. This approach ensures that the fuel cell is less exposed to rapid load variations, which would otherwise reduce efficiency and accelerate degradation.

When both the battery and supercapacitor are integrated into the powertrain, a simple EMS has been implemented. The strategy prioritizes the use of the supercapacitor, exploiting its high power density to cover transient demands, while the battery is involved only under specific conditions: when the supercapacitor voltage drops below 50% of its nominal value during discharge or when the supercapacitor is fully charged during regenerative braking. This ensures that the supercapacitor is primarily responsible for managing fast dynamics, while the battery is employed as a secondary buffer, preserving its cycle life and energy efficiency.

5. Simulation Results

To compare the performance of the different configurations in terms of energy consumption, dedicated models were developed in MATLAB/Simulink, following the mathematical framework described in

Section 2. The efficiency of the NMC cells, together with the efficiency data of the supercapacitor and the fuel cell, were integrated into the vehicle model. Three architectures were implemented: fuel cell with a battery, fuel cell with a supercapacitor, and a hybrid system combining the fuel cell, battery, and supercapacitor. To ensure a fair comparison, the converters, motor, electrical machines, and storage components were kept identical across all three configurations.

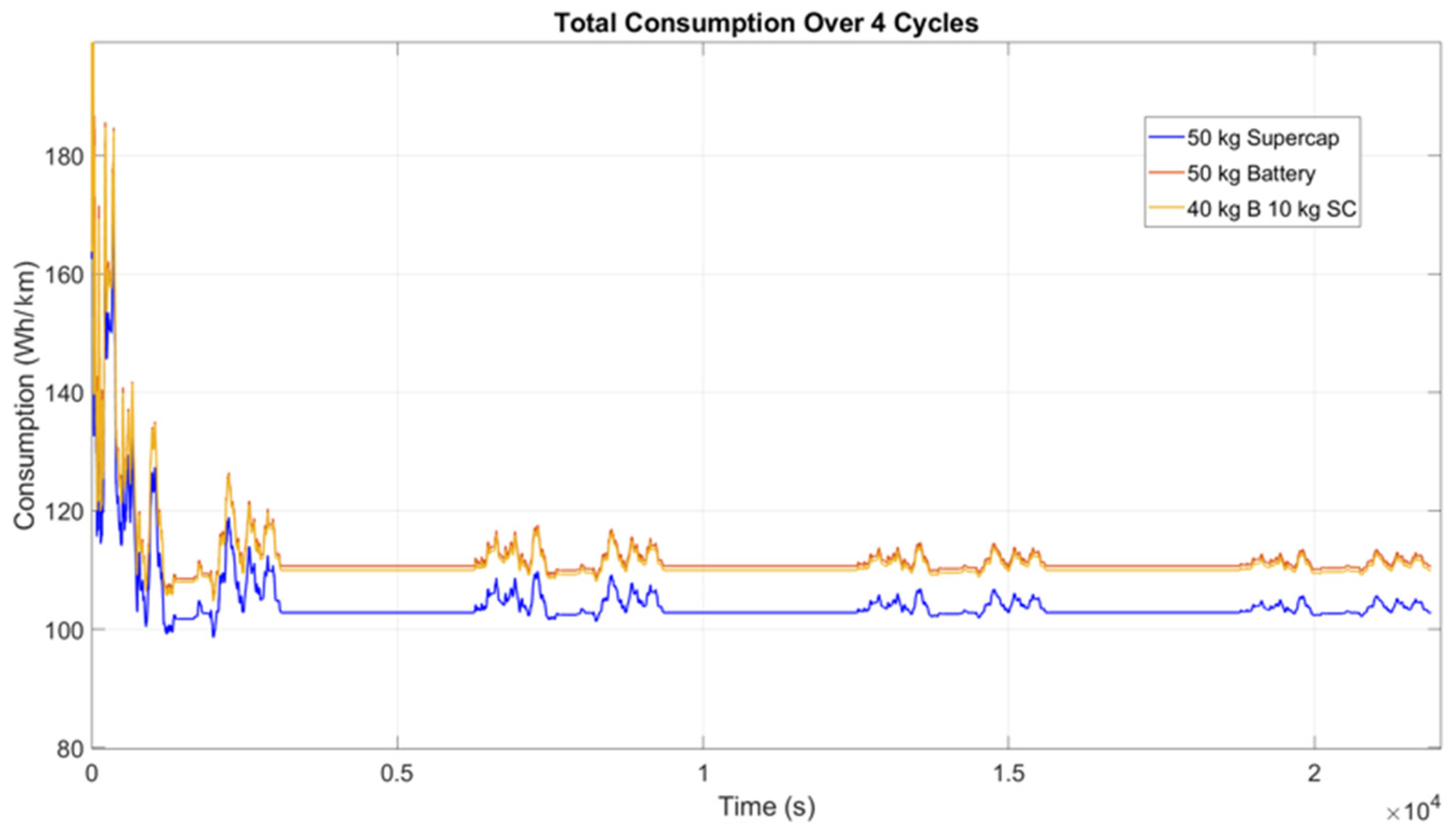

As a preliminary step, a comparison between the battery and the supercapacitor, without the fuel cell, was carried out to assess the intrinsic efficiency of the two storage systems during the mission profile. For this purpose, the weight of both storage systems was fixed at 50 kg. The corresponding fuel economy results are presented in

Figure 5: the red trace refers to the fuel consumption (Wh/km) obtained using only the battery, the blue trace shows the performance of the supercapacitor, while the yellow trace corresponds to the case in which the two devices operate together. It should be noted that this comparison was performed exclusively to evaluate storage efficiencies, as relying on the supercapacitor alone is not feasible in terms of range.

It can be noted that a cycle of multiple consecutive missions has been considered, each time using the final conditions of the previous run. This approach allows for obtaining an average energy consumption as a function of the initial conditions.

In this scenario, a simple energy management strategy (EMS) was adopted: the supercapacitor was prioritized, with the battery engaged only when the supercapacitor voltage dropped to 50% of its nominal value during discharge or when it reached full charge during regenerative braking. To ensure robustness of the results, four consecutive missions were simulated. Furthermore, in the combined storage case, the system was configured with a 40 kg battery and a 10 kg supercapacitor, thus maintaining the total mass constraint of 50 kg. Please note that, in this study, the iso-mass comparison has been preferred compared to the iso-energy, since the overall vehicle mass directly affects the energy consumption, dynamic performance, and payload capability.

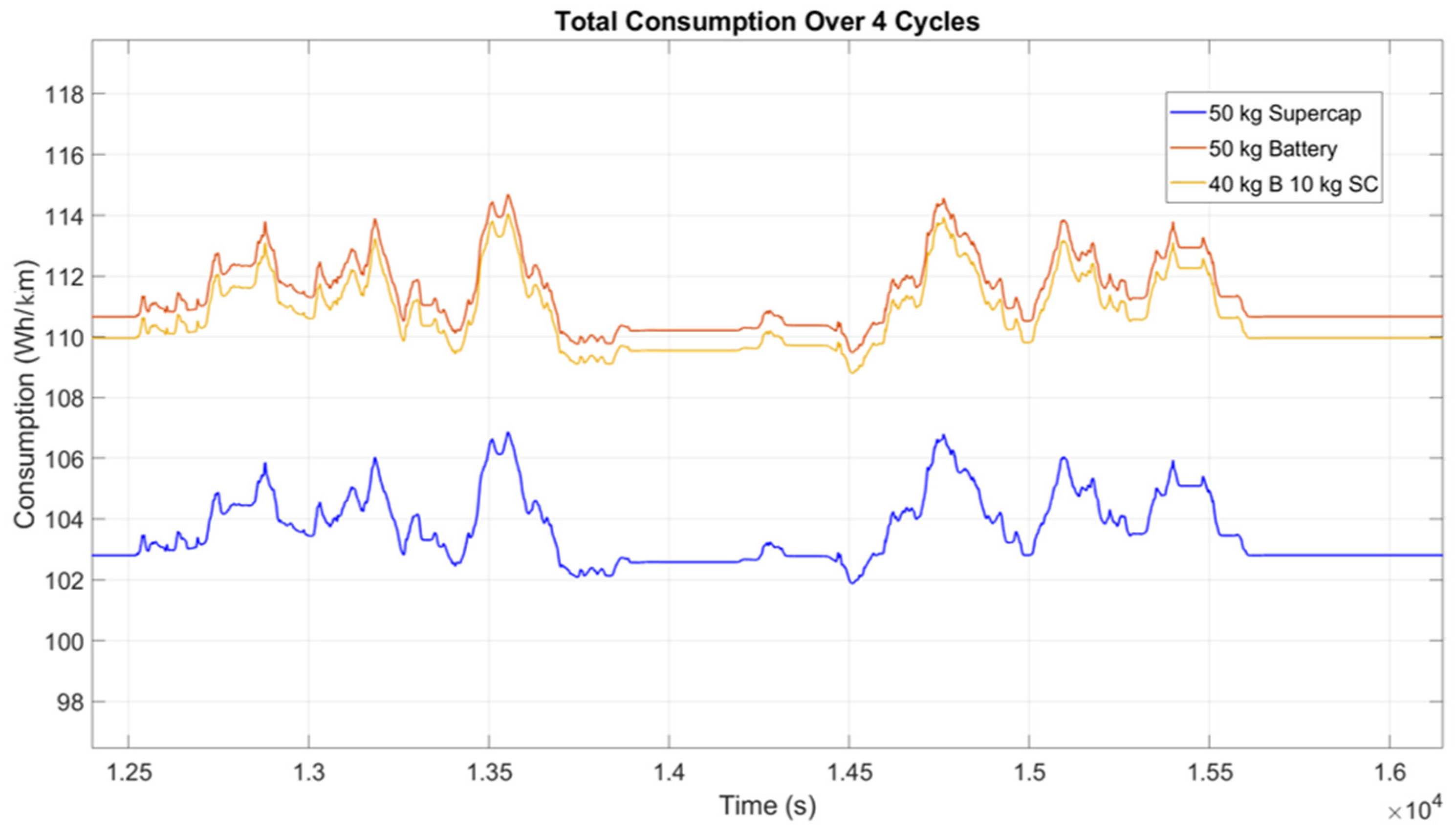

A closer view of the same test is presented in

Figure 6, highlighting that using the supercapacitor alone results in a consumption reduction of approximately 7% compared to the battery-only case (red trace). In contrast, the combined use of both storage systems yields a smaller decrease in energy consumption, less than 1%, once again relative to the battery-only scenario.

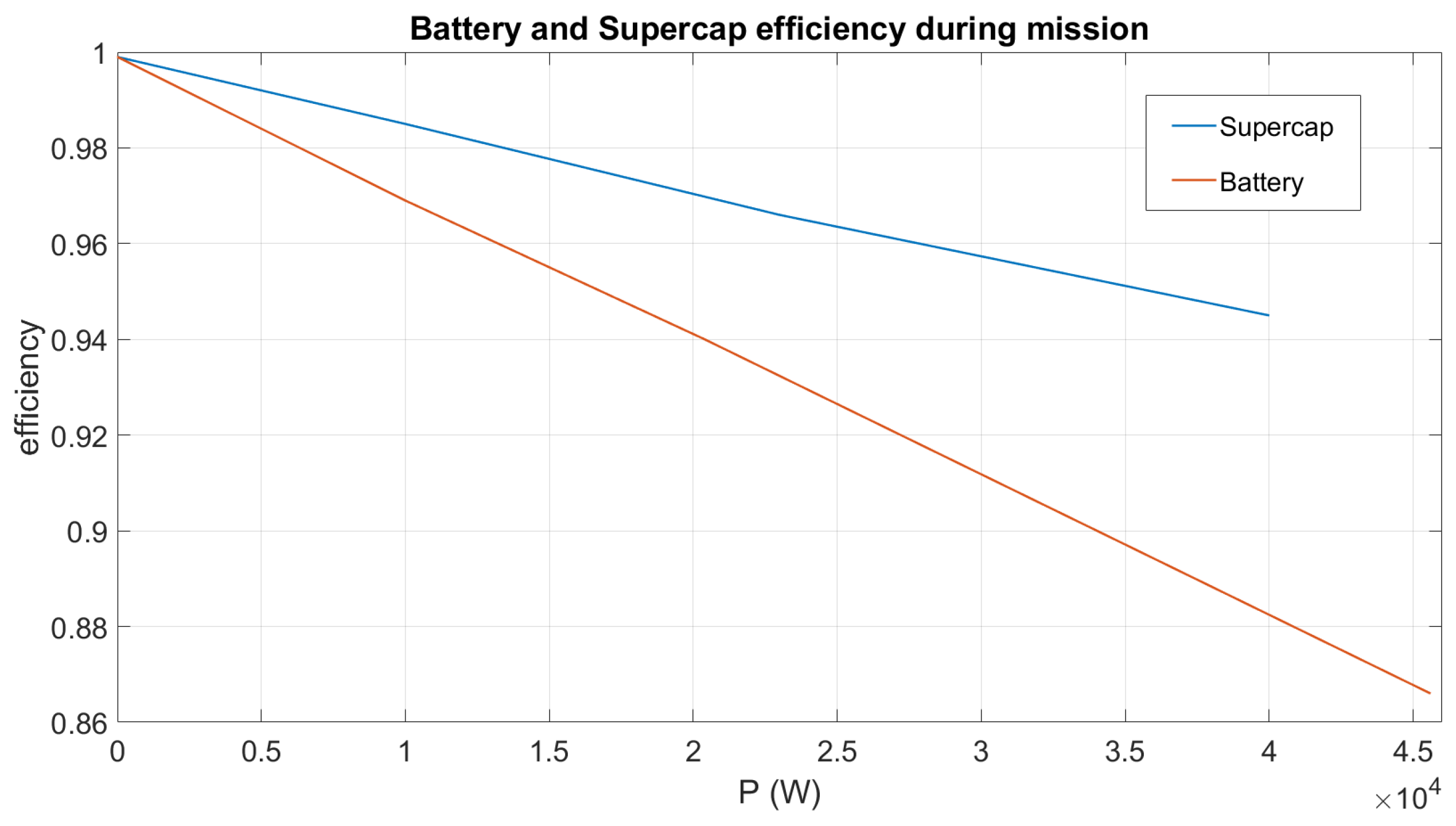

The variation in efficiency of both the battery and the supercapacitor over the course of the mission is illustrated in

Figure 7. It should be noted that this figure refers specifically to the configuration consisting of a 40 kg battery combined with a 10 kg supercapacitor.

In addition, the vehicle range has been evaluated during a mission in three configurations: 50 kg battery, 40 kg battery plus 10 kg supercapacitor, and 45 kg battery plus 5 kg supercapacitor; the results have been reported in

Table 2, together with a summary of the consumptions.

As shown in

Table 2, the vehicle range decreases by approximately 10% when a 5 kg supercapacitor is introduced, with an additional 10% reduction observed for the configuration with a 40 kg battery combined with a 10 kg supercapacitor. At this stage, the fuel cell was incorporated into the model to enable a comparative analysis of the three configurations:

As previously discussed, in fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), the fuel cell system is generally managed to operate at an almost constant power level, typically matching the vehicle’s average power demand. This approach helps to optimize the efficiency, durability, and dynamic response. Because fuel cells achieve higher efficiency and a longer life when operating steadily, this control strategy reduces performance degradation caused by frequent load fluctuations. To meet transient power requirements, an auxiliary energy storage system, such as a battery or supercapacitor, is incorporated into the powertrain. During acceleration or periods of high power demand, the auxiliary storage supplements the fuel cell output, while during braking or low-load phases, surplus energy is captured and stored in the auxiliary system. This hybrid energy management strategy improves overall vehicle efficiency and dynamic performance, ensuring that the fuel cell operates optimally while also maximizing the use of regenerative braking energy.

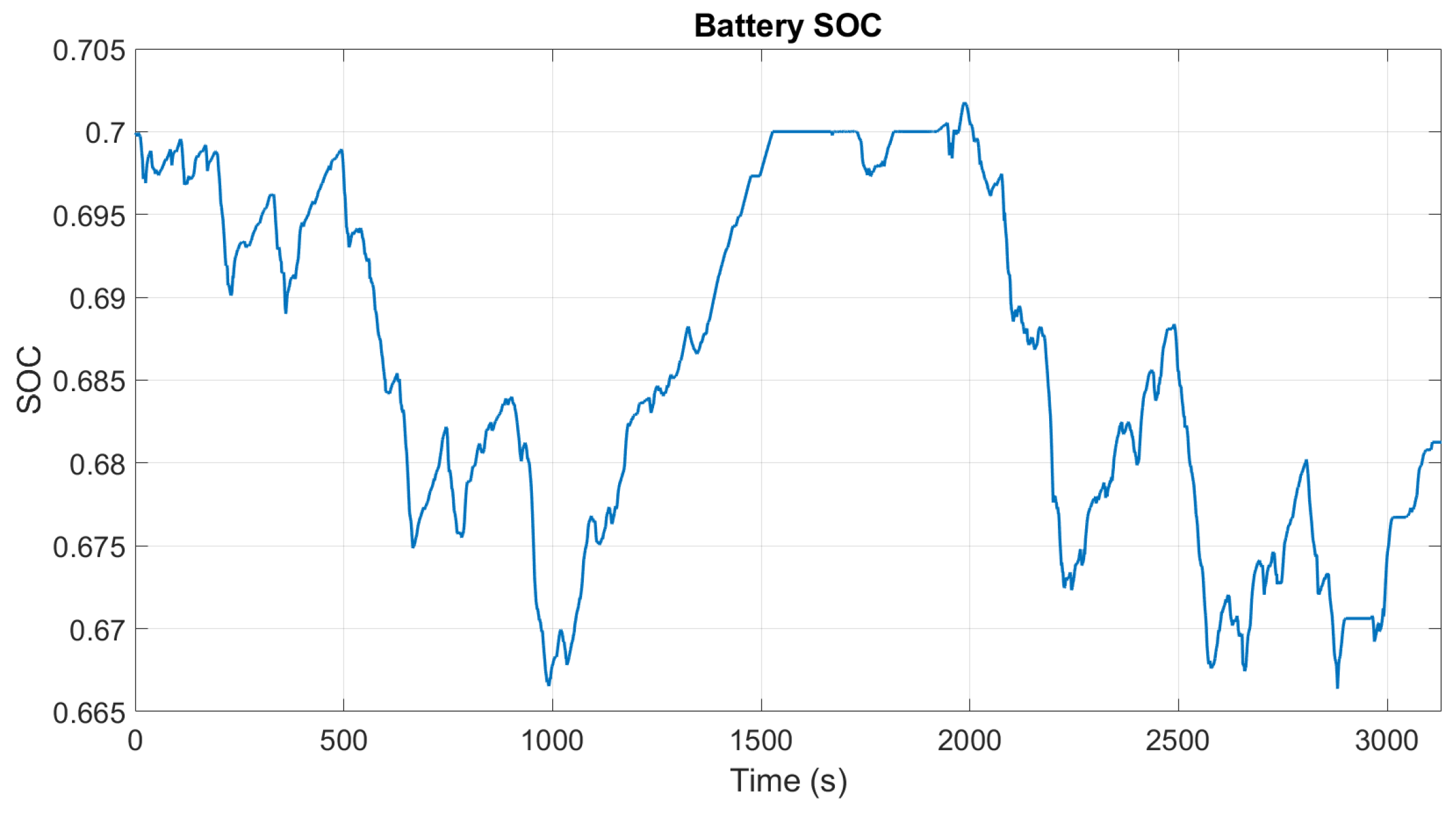

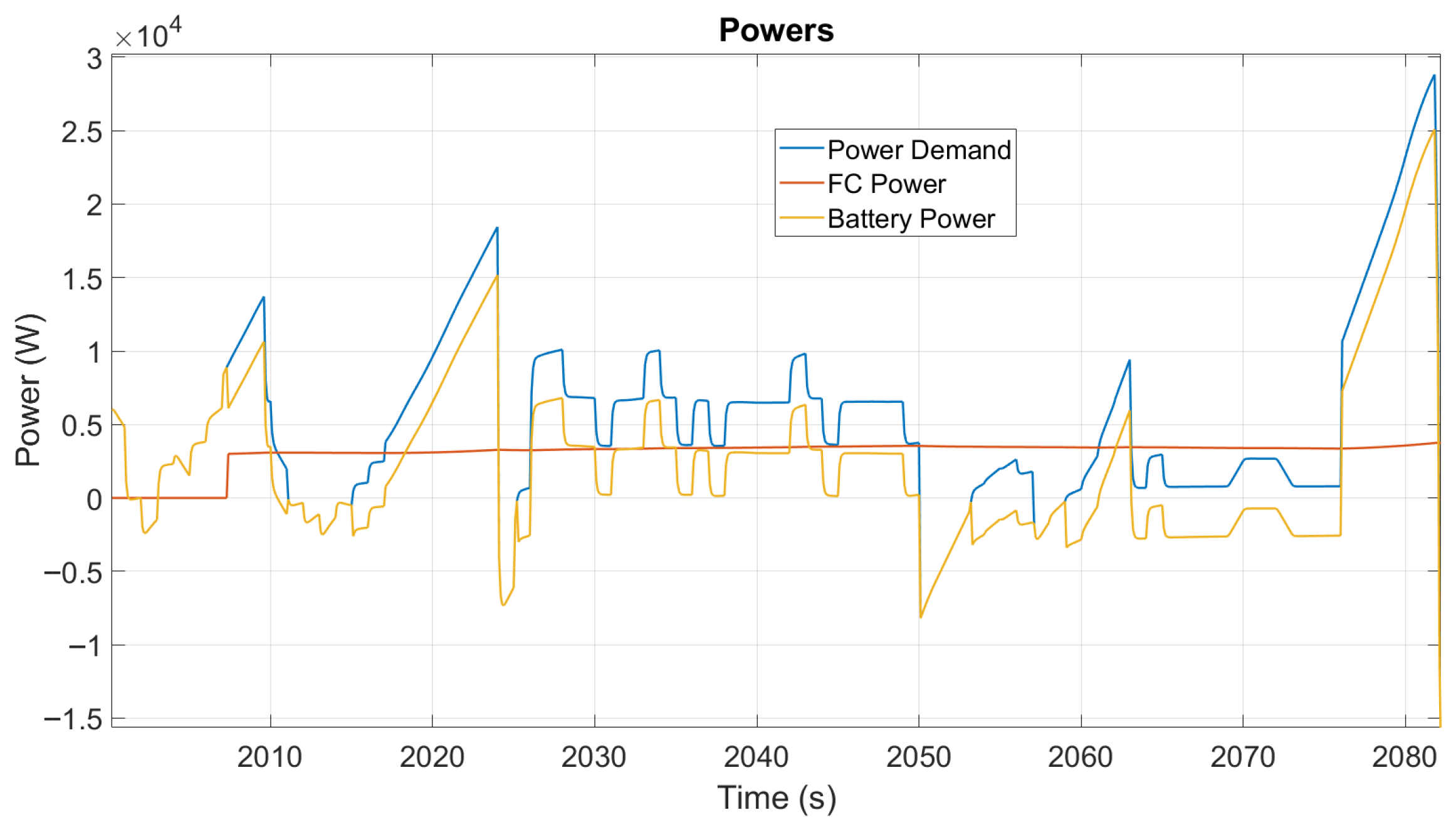

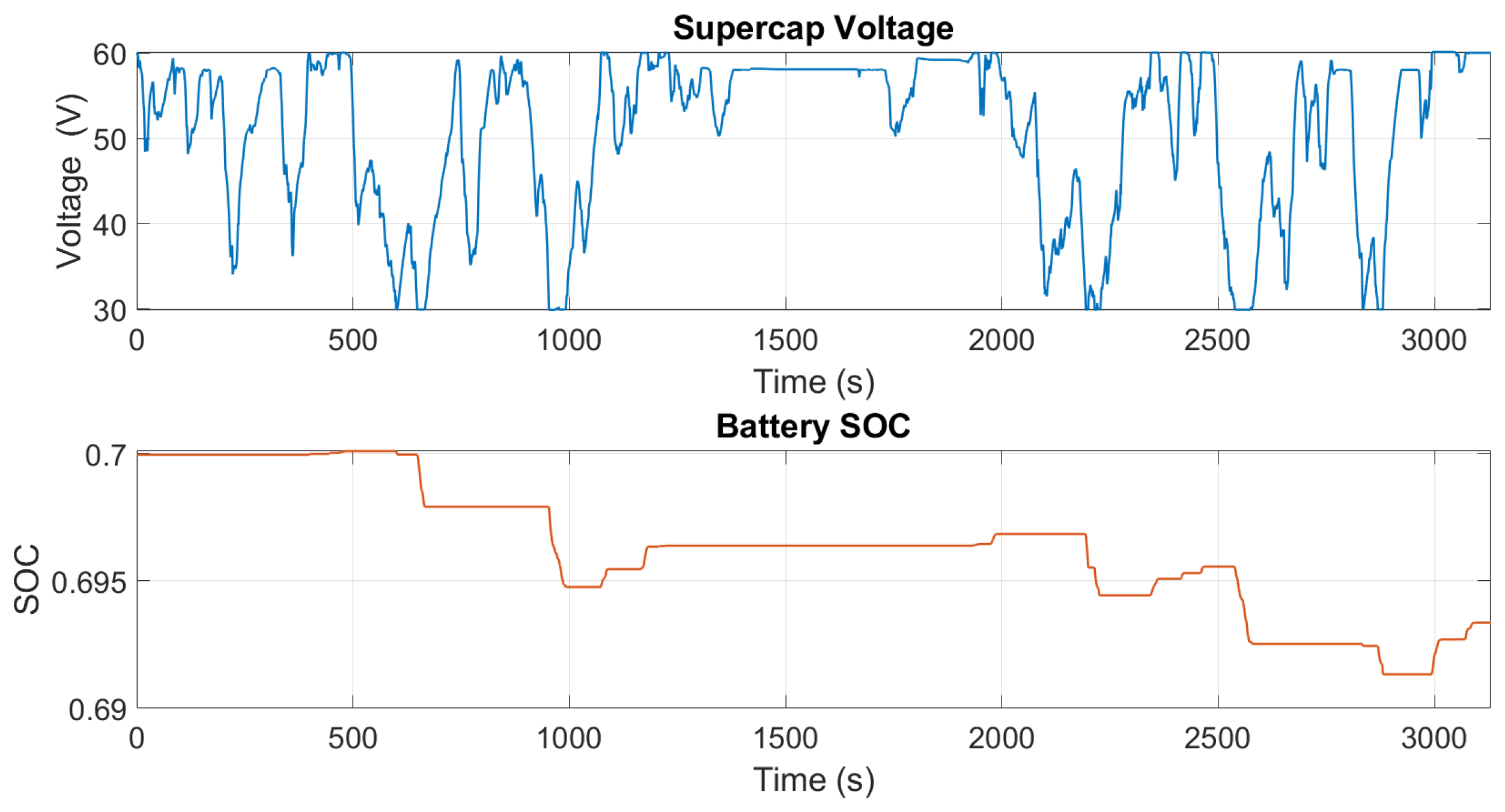

5.1. Fuel Cell and Battery

In this configuration, the battery’s state of charge (SOC) is maintained within a target range of 65% to 75%. The fuel cell output is controlled based on the battery SOC, with the additional rule that the fuel cell is switched off during regenerative braking whenever the battery SOC reaches 75%. The measured battery SOC over the mission, along with a detailed view of the resulting power distribution, are presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, respectively.

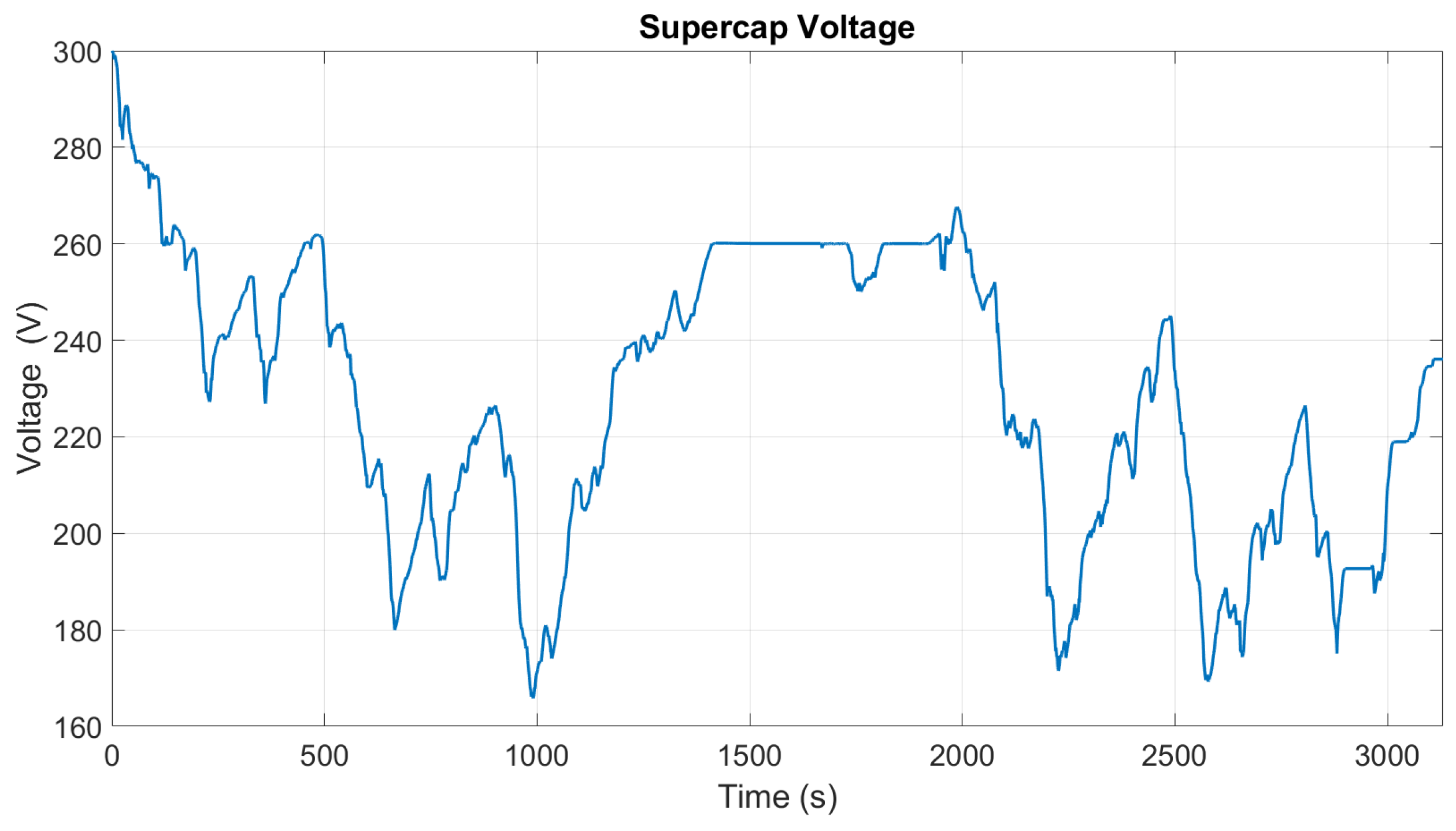

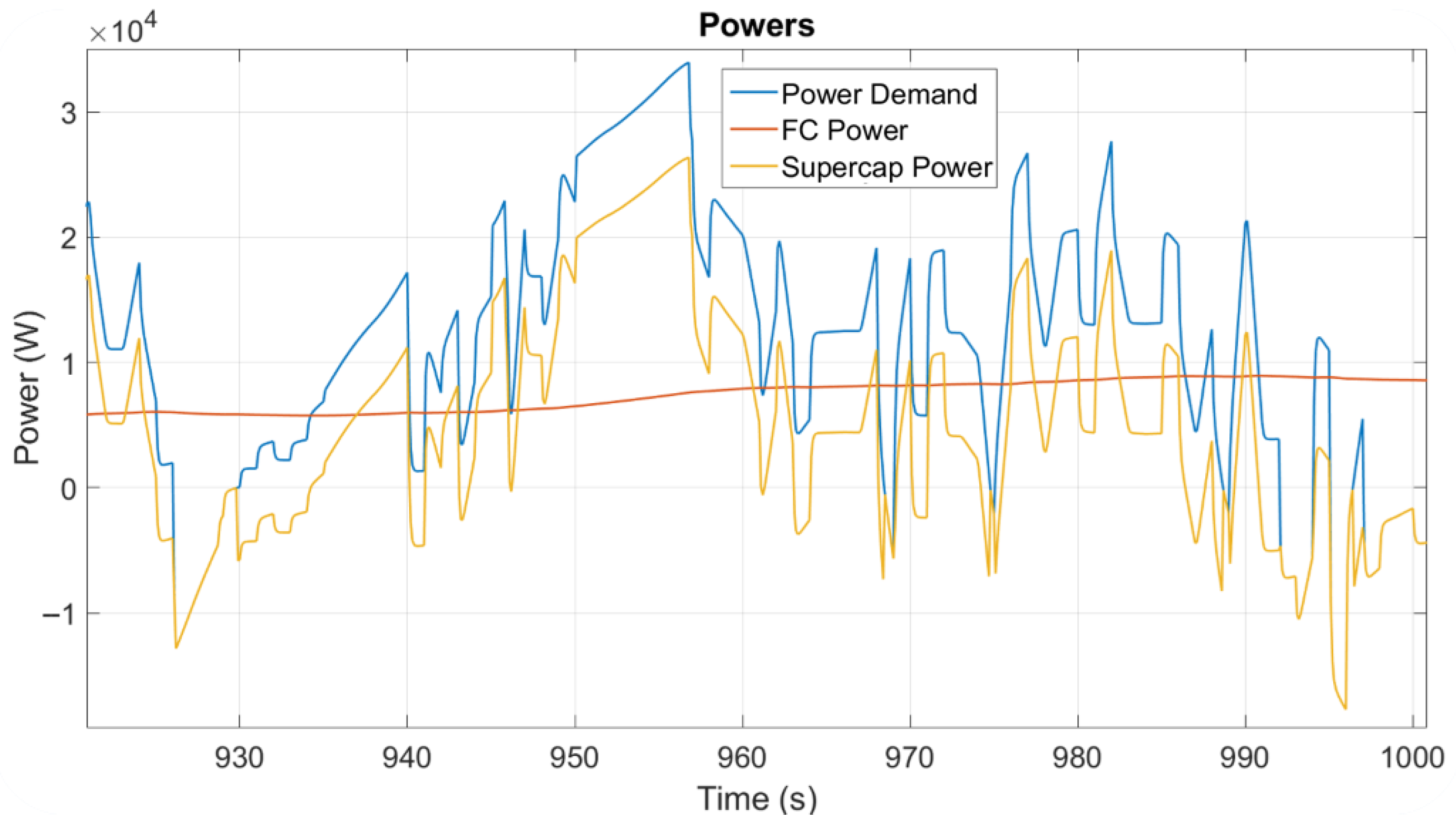

5.2. Fuel Cell and Supercapacitor

Similarly, when the supercapacitor is used instead of a battery system, the fuel cell output is regulated based on the supercapacitor voltage, while the voltage is maintained within the range [Vrated/2; Vrated]. As in the battery case, the fuel cell is switched off during regenerative braking whenever the supercapacitor reaches full charge. The measured supercapacitor voltage and a detailed view of the resulting power distribution are shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, respectively. From the zoomed section in

Figure 11, it can be observed that, as the supercapacitor voltage decreases (see

Figure 10 at 2500 s), the fuel cell output correspondingly increases.

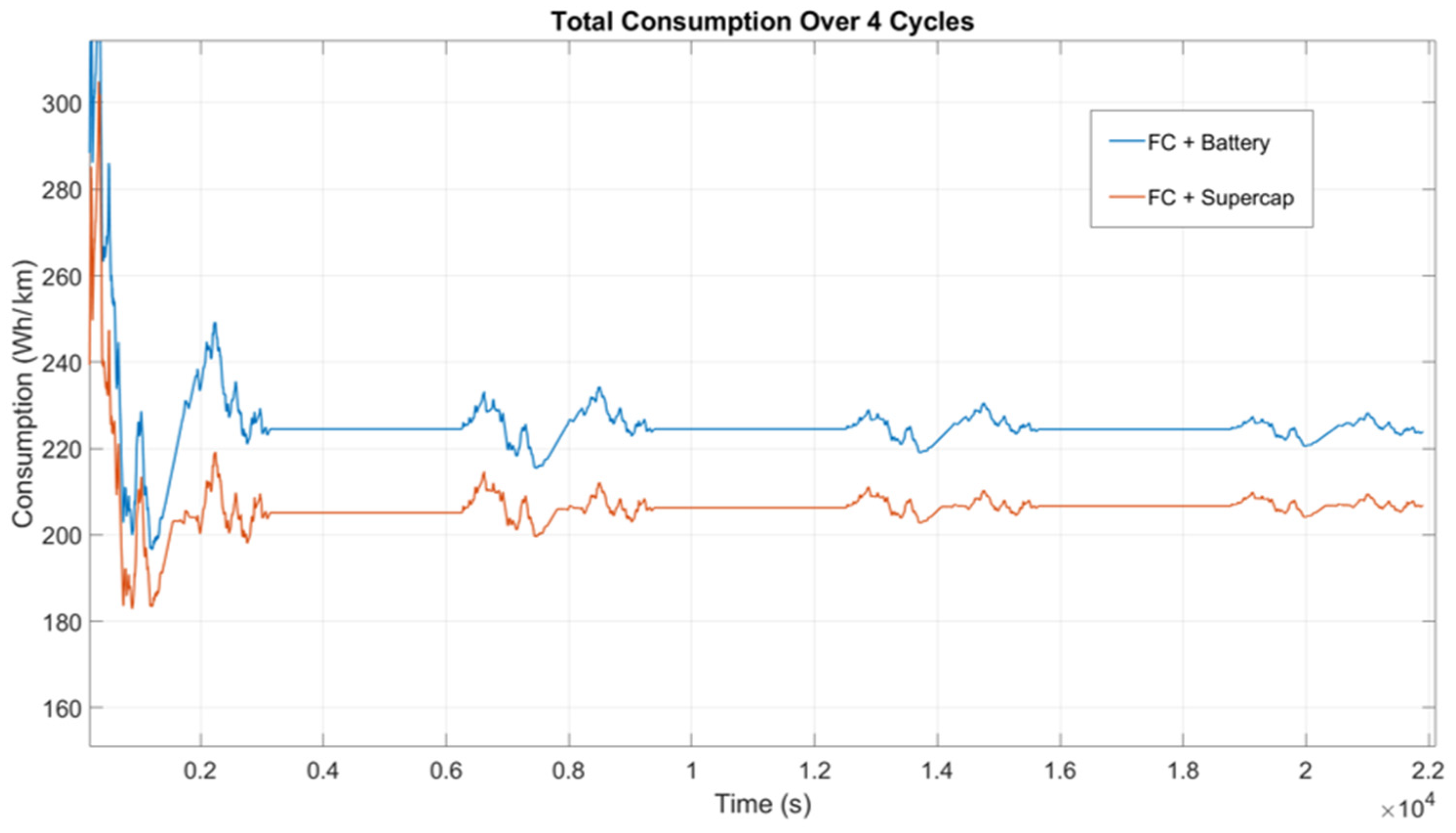

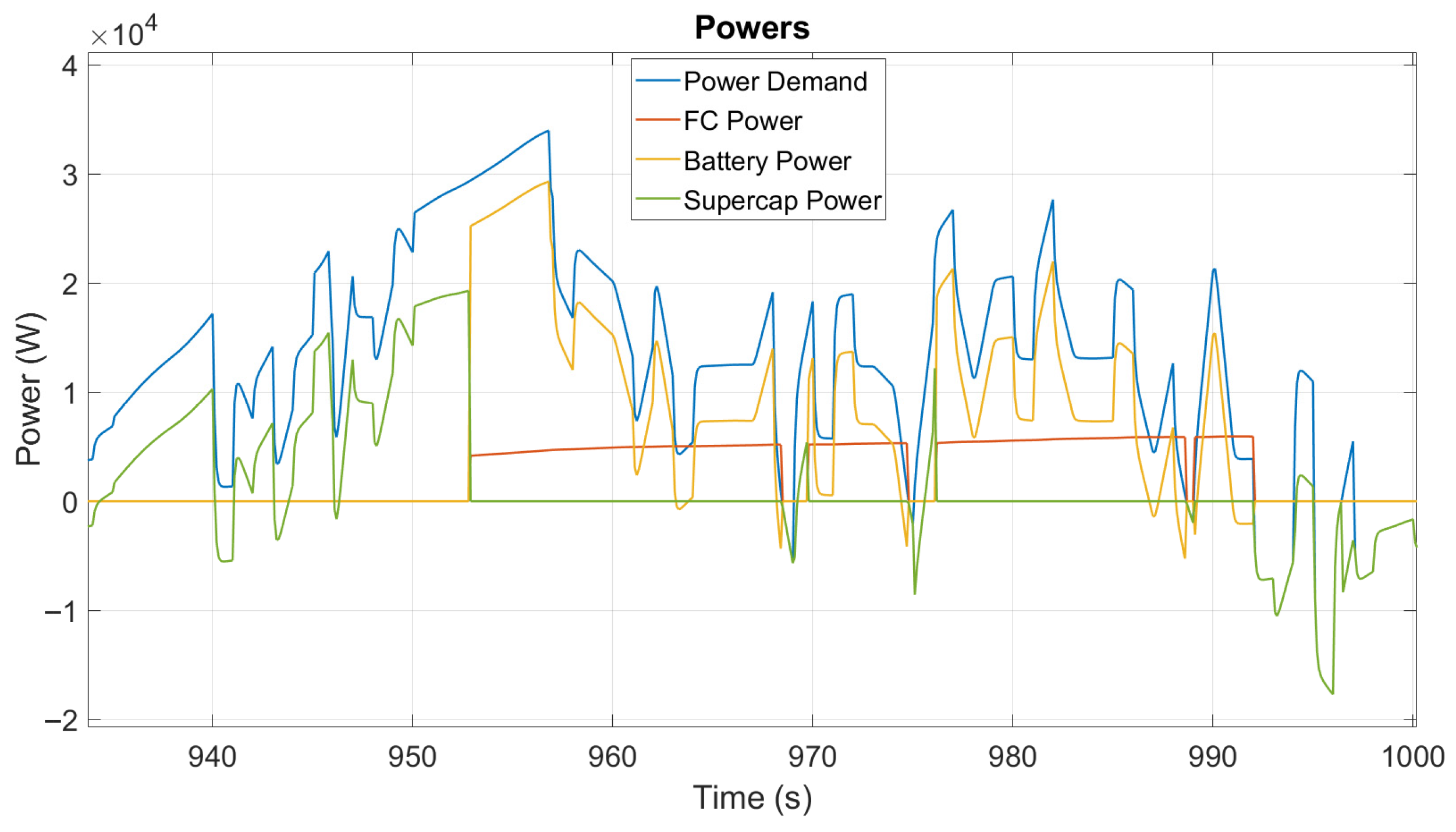

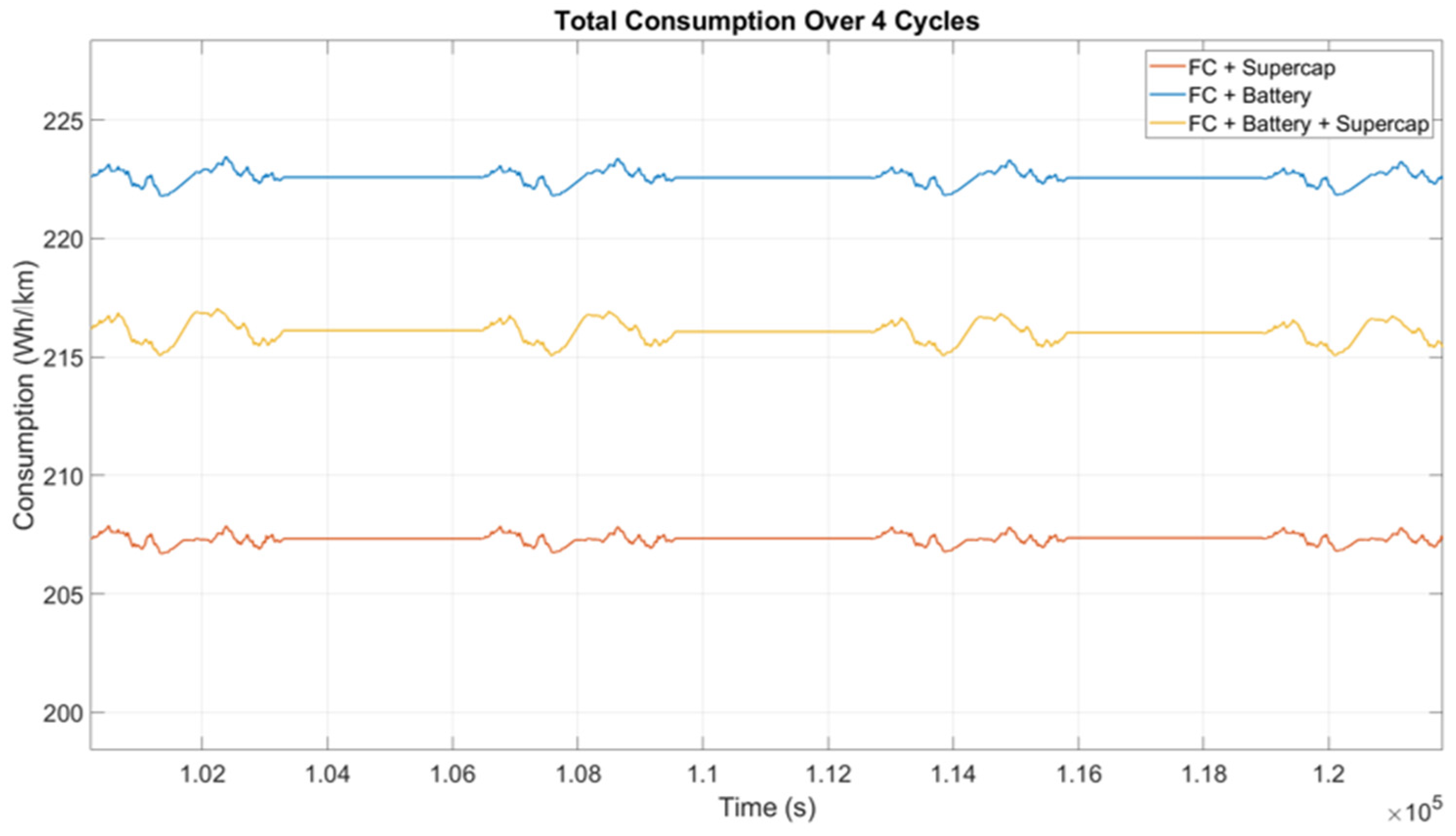

5.3. Fuel Cell with Both Battery and Supercapacitor

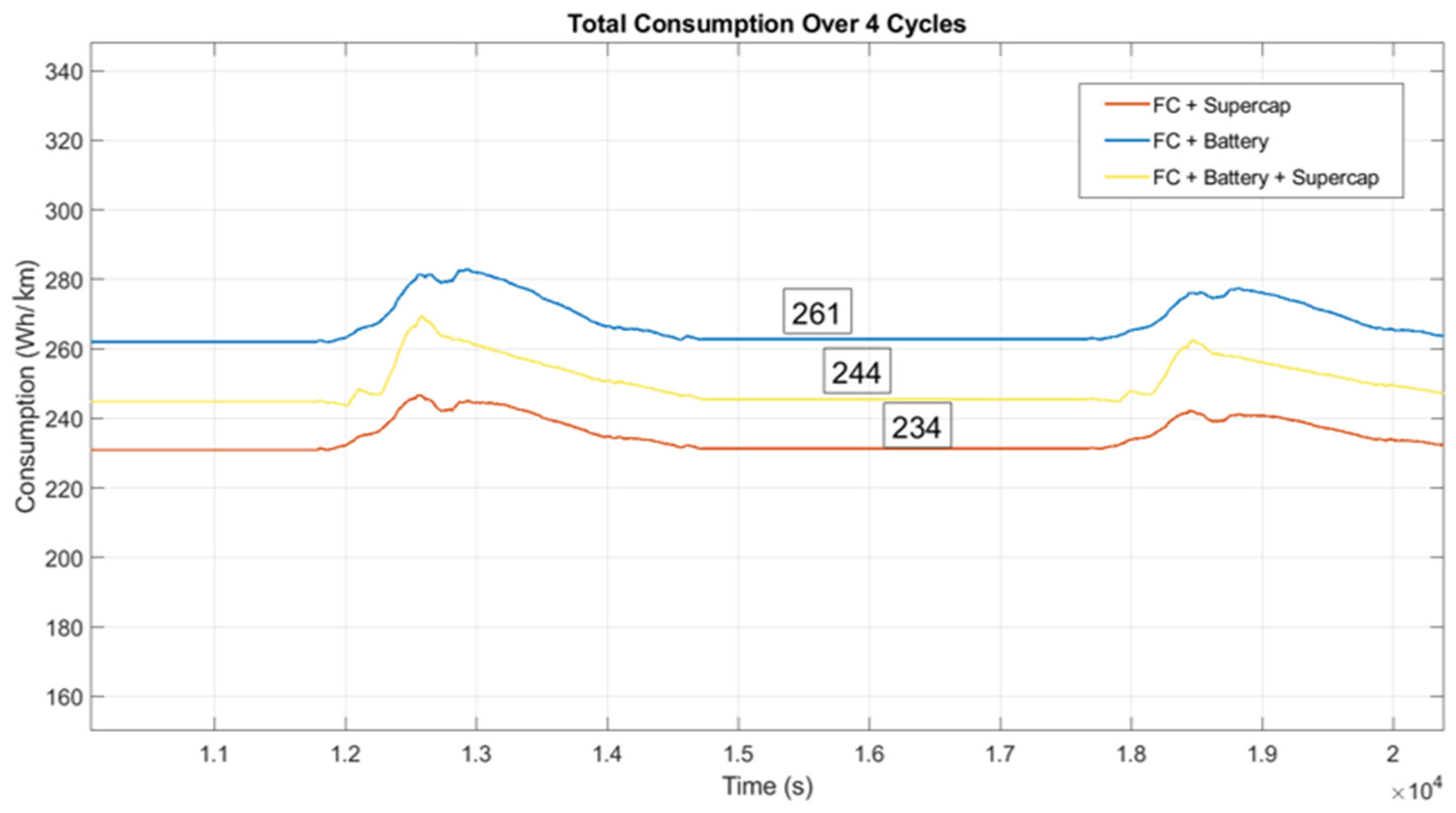

First, the energy consumption of the configurations of

Section 5.1 and

Section 5.2 are evaluated and compared during a cycle of four consecutive missions, and the result is shown in

Figure 12. Analogously to the comparison of

Figure 6, without the fuel cell, the advantage of using a supercapacitor over a battery is a reduction of 7% in consumption. Please note that, compared to the results of

Figure 6, the average consumptions are now higher due to the lower overall fuel cell efficiency.

In this last subsection the combined utilization of both the battery and supercapacitor with the fuel cell has been analyzed. As for the simple battery/supercapacitor comparison of

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the configuration with a 40 kg battery and a 10 kg supercapacitor has been considered. It can be noted that, in this study, the results are presented in the condition of iso-mass, which is the relevant constraint in vehicle design, as total weight strongly influences efficiency, cost, and dynamic performance. An iso-energy comparison has been conceptually analyzed, but it would have led to a substantial increase in the vehicle’s mass due to the low energy density typical of supercapacitors.

In order to give a better understanding of the EMS, three block diagrams have been reported in

Figure 13, representing the control logic implemented in the three analyzed configurations.

Please note that the resulting rated voltage value for the supercapacitor is now 60 V, as highlighted in the upper plot of

Figure 14.

Figure 15 shows a zoom of the resulting power distribution, while the measured supercapacitor voltage and battery SOC are reported in

Figure 15.

From both

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, it can be seen that the use of a supercapacitor has been prioritized since it offers higher efficiency, and the battery is used when the supercapacitor voltage reaches the limits of [Vrated/2; Vrated]. Again, battery SOC is properly controlled in the range 65–75%, while the fuel cell is regulated to provide power in the function of the battery SOC.

The following simulation results, presented in

Figure 16, compare the energy consumption from

Figure 12 with that of the hybrid configuration in which both the battery and supercapacitor are used alongside the fuel cell. The hybrid system (yellow line) achieves a reduction in energy consumption of approximately 3% compared to the battery-only configuration (blue line), while using only the supercapacitor (red line) results in an energy saving of about 4% relative to the hybrid setup. As in previous tests, a cycle of four consecutive missions was simulated to obtain these results.

Table 3 shows a comparison of the evaluated hydrogen consumption during a single mission in the three configurations.

In order to enhance the aspect of the real mission performances, a new extra-urban mission has been tested, and its results are depicted in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18. In

Figure 17, the speed trace and the elevation profile of the extra-urban mission are shown, while the resulting energy consumption comparison of the three configurations during a cycle of four consecutive missions is reported in

Figure 18, where, analogously to the urban mission, the fuel cell–supercapacitor configuration exhibits the best performance in terms of energy consumption.

These findings indicate that, considering efficiency alone, the fuel cell–supercapacitor combination provides the greatest benefit compared to the fuel cell–battery configuration. Nevertheless, ongoing advancements in battery technology mean that battery use can offer significant advantages, particularly when a plug-in mode is required. Additionally, in scenarios where plug-in operation has limited impact on the overall energy consumption, the combined use of batteries and supercapacitors can provide further benefits. To summarize these observations,

Table 4 presents the preferred storage solution for each FCEV configuration based on the simulation results.

6. Conclusions

In this work, the integration of battery and supercapacitor systems with fuel cells in FCEVs has been investigated through the development of three configurations in a MATLAB/Simulink environment. Their energy consumption was assessed under real driving conditions.

The results indicate that, in terms of efficiency alone, the fuel cell–supercapacitor configuration provides the most favorable performance compared to the fuel cell–battery arrangement. Although the numerical difference in energy consumption between the analyzed configurations can seem modest (3–10%), in fuel cell electric vehicles, even small percentage improvements in overall efficiency can lead to measurable reductions in hydrogen consumption, which directly impact the operating cost, refueling frequency, and autonomy. Nonetheless, ongoing progress in battery technology suggests that batteries may offer significant advantages, particularly when plug-in capability is required. Furthermore, in scenarios where plug-in operation is less relevant, the combined use of batteries and supercapacitors can deliver additional benefits. Moreover, it is worth noting that, in the paper, a plug-in-capable architecture has been considered to highlight the potential for external recharging of the auxiliary battery, and the main objective of this study was to compare the energy management performance of the three hybrid configurations under real urban conditions. The external grid-charging process itself, and the corresponding post-charging energy flows, were outside the present work scope, and the EMS focuses on on-board energy management rather than charging infrastructure interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and M.P.; methodology, S.C.; software, A.B.; validation, A.F., L.V. and M.C.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.C.; resources, M.P.; data curation, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, A.F.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, A.F.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been developed within the project “Network 4 Energy Sustainable Transition—NEST” funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Spoke 4.4.2—Call for Tender No. 1561 of 11.10.2022 of Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR); funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, S.; Chen, Z.; Huang, D.; Lin, T. Model Prediction and Rule Based Energy Management Strategy for a Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle with Hybrid Energy Storage System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 5926–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemian, D.; Bode, F. Battery-supercapacitor energy storage systems for electrical vehicles: A review. Energies 2022, 15, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, H.; Jia, C.; Guo, S. The Energy Management Strategies for Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles: An Overview and Future Directions. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.R.; Cheng, K.-W.; Xue, X.-D.; Fong, Y.-C.; Cheung, S. Hybrid energy storage system with vehicle body integrated super-capacitor and li-ion battery: Model, design and implementation, for distributed energy storage. Energies 2021, 14, 6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Vairin, C.; von Jouanne, A.; Agamloh, E.; Yokochi, A. Review of fuel-cell electric vehicles. Energies 2024, 17, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorlei, I.-S.; Bizon, N.; Thounthong, P.; Varlam, M.; Carcadea, E.; Culcer, M.; Iliescu, M.; Raceanu, M. Fuel cell electric vehicles—A brief review of current topologies and energy management strategies. Energies 2021, 14, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethoux, O. Hydrogen fuel cell road vehicles: State of the art and perspectives. Energies 2020, 13, 5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, J. The Impact of Hybrid Energy Storage System on the Battery Cycle Life of Replaceable Battery Electric Vehicle. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmeyer, P.J.; Wootton, M.; Reimers, J.; Opila, D.F.; Kurera, H.; Kadakia, M.; Gu, R.; Stiene, T.; Chemali, E.; Wood, M.; et al. Real-Time Control of a Full Scale Li-ion Battery and Li-ion Capacitor Hybrid Energy Storage System for a Plug-in Hybrid Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 4204–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Kamal, E.; Ghorbani, R. Reliable Energy Optimization Strategy for Fuel Cell Hybrid Electric Vehicles Considering Fuel Cell and Battery Health. Energies 2024, 17, 4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.; Marei, M.I.; Mokhtar, M. Comprehensive Study of Fuel Cell Hybrid Electric Vehicles: Classification, Topologies, and Control System Comparisons. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Yan, J. Enhancing fuel cell durability for fuel cell plug-in hybrid electric vehicles through strategic power management. Appl. Energy 2019, 241, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosso, S.; Benevieri, A.; Marchesoni, M.; Passalacqua, M.; Vaccaro, L.; Pozzobon, P. A New Topology of Multi-Input Bidirectional DC-DC Converters for Hybrid Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Chau, K.T. Health-conscious energy management for fuel cell vehicles: An integrated thermal management strategy for cabin and energy source systems. Energy 2025, 333, 137330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeogu, C.U.; Lim, W.J.I.A. Improved deep learning-based energy management strategy for battery-supercapacitor hybrid electric vehicle with adaptive velocity prediction. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 133789–133802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.-D.; Yoon, C.; Lee, Y.I.J.I.T.o.I.E. A standalone energy management system of battery/supercapacitor hybrid energy storage system for electric vehicles using model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 70, 5104–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, A.; Mahanta, C.J.I.T.o.V.T. Optimal Online Energy Management System for Battery-Supercapacitor Electric Vehicles Using Velocity Prediction and Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 74, 2652–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golchoubian, P.; Azad, N.L. Real-Time Nonlinear Model Predictive Control of a Battery–Supercapacitor Hybrid Energy Storage System in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 9678–9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parczewski, K.; Wnęk, H. Analysis of Energy Flow in Hybrid and Electric-Drive Vehicles. Energies 2024, 17, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Barroso, Á.; Makazaga, I.V.; Zulueta, E. Optimizing Hybrid Electric Vehicle Performance: A Detailed Overview of Energy Management Strategies. Energies 2025, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, M.; Lanzarotto, D.; Repetto, M.; Vaccaro, L.; Bonfiglio, A.; Marchesoni, M. Fuel Economy and EMS for a Series Hybrid Vehicle Based on Supercapacitor Storage. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 9966–9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythbattery. Available online: https://lythbattery.com/eve-m21-ncm-58ah-inp58p-3-62v-ncm-battery-cell-ev-car-batteries/?lang=it (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Maxwell Technologies. Available online: https://maxwell.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/3003483-EN.0_DS_3V-3000F-Cell-BCAP3000-P300.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Axane Technologies. Available online: https://advancedtech.airliquide.com/markets-solutions/energy-transition/axane-fuel-cell-expertise (accessed on 1 July 2025).

Figure 1.

Reference speed during mission.

Figure 1.

Reference speed during mission.

Figure 2.

Route altitude during mission.

Figure 2.

Route altitude during mission.

Figure 3.

FCEV powertrain.

Figure 3.

FCEV powertrain.

Figure 4.

Plug-in FCEV powertrain with the new multi-input dc-dc converter.

Figure 4.

Plug-in FCEV powertrain with the new multi-input dc-dc converter.

Figure 5.

Battery and supercapacitor energy consumption comparison.

Figure 5.

Battery and supercapacitor energy consumption comparison.

Figure 6.

Battery and supercapacitor energy consumption comparison (zoom).

Figure 6.

Battery and supercapacitor energy consumption comparison (zoom).

Figure 7.

Battery and supercapacitor fuel consumption comparison.

Figure 7.

Battery and supercapacitor fuel consumption comparison.

Figure 8.

Battery SOC during a mission.

Figure 8.

Battery SOC during a mission.

Figure 9.

FC and battery power distribution (zoom).

Figure 9.

FC and battery power distribution (zoom).

Figure 10.

Power distribution and supercapacitor voltage during a mission.

Figure 10.

Power distribution and supercapacitor voltage during a mission.

Figure 11.

FC and supercapacitor power distribution (zoom).

Figure 11.

FC and supercapacitor power distribution (zoom).

Figure 12.

Battery and supercapacitor energy consumption comparison with fuel cell.

Figure 12.

Battery and supercapacitor energy consumption comparison with fuel cell.

Figure 13.

EMS block diagram in the three configurations considered.

Figure 13.

EMS block diagram in the three configurations considered.

Figure 14.

FC battery and supercapacitor power distribution during a mission.

Figure 14.

FC battery and supercapacitor power distribution during a mission.

Figure 15.

FC battery and supercapacitor power distribution during a mission (zoom).

Figure 15.

FC battery and supercapacitor power distribution during a mission (zoom).

Figure 16.

Energy consumption final comparison in urban missions.

Figure 16.

Energy consumption final comparison in urban missions.

Figure 17.

Extra-urban mission: speet trace (left), elevation profile (right).

Figure 17.

Extra-urban mission: speet trace (left), elevation profile (right).

Figure 18.

Energy consumption comparison of extra-urban mission.

Figure 18.

Energy consumption comparison of extra-urban mission.

Table 1.

Medium size car parameters.

Table 1.

Medium size car parameters.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|

| Weight | 1500 kg |

| Rolling coefficient | 0.01 |

| Aerodynamic drag coefficient | 0.25 |

| Vehicle front area | 2.3 m2 |

| Differential gear efficiency | 0.97 |

| Electric motor power | 50 kW |

| Fuel cell rated power | 10 kW |

| Battery/Supercapacitor weight | 50 kg |

| Battery weight (hybrid conf.) | 40 kg |

| Supercapacitor weight (hybrid conf). | 10 kg |

Table 2.

Total energy, consumption, and range.

Table 2.

Total energy, consumption, and range.

| | Total Energy | Energy Consumption | Range |

|---|

| 50 kg Battery | 10 kWh | 110 Wh/km | 88 km |

| 45 kg Battery 5 kg Supercap | 9.04 kWh | 110.5 Wh/km | 80.1 km |

| 40 kg Battery 10 kg Supercap | 8.1 kWh | 111 Wh/km | 71.8 km |

Table 3.

Hydrogen consumption in the three considered configurations.

Table 3.

Hydrogen consumption in the three considered configurations.

| Storage Configuration | Hydrogen Consumption [kg/km] |

|---|

| Fuel cell + Supercap | 0.01212 |

| Fuel cell + Battery | 0.01260 |

| Fuel cell + Battery and Supercap | 0.01236 |

Table 4.

Summary results.

Table 4.

Summary results.

| FCEV Configuration | Storage Configuration |

|---|

| FC mode without plug-in | Fuel cell + Supercap |

| Relevant plug-in operation | Fuel cell + Battery |

| Minor relevance plug-in operation | Fuel cell + Battery and Supercap |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).