Distribution-Level PV Representative Bands: Blockwise BGMM and NSGA-II for Coverage and Tail-Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

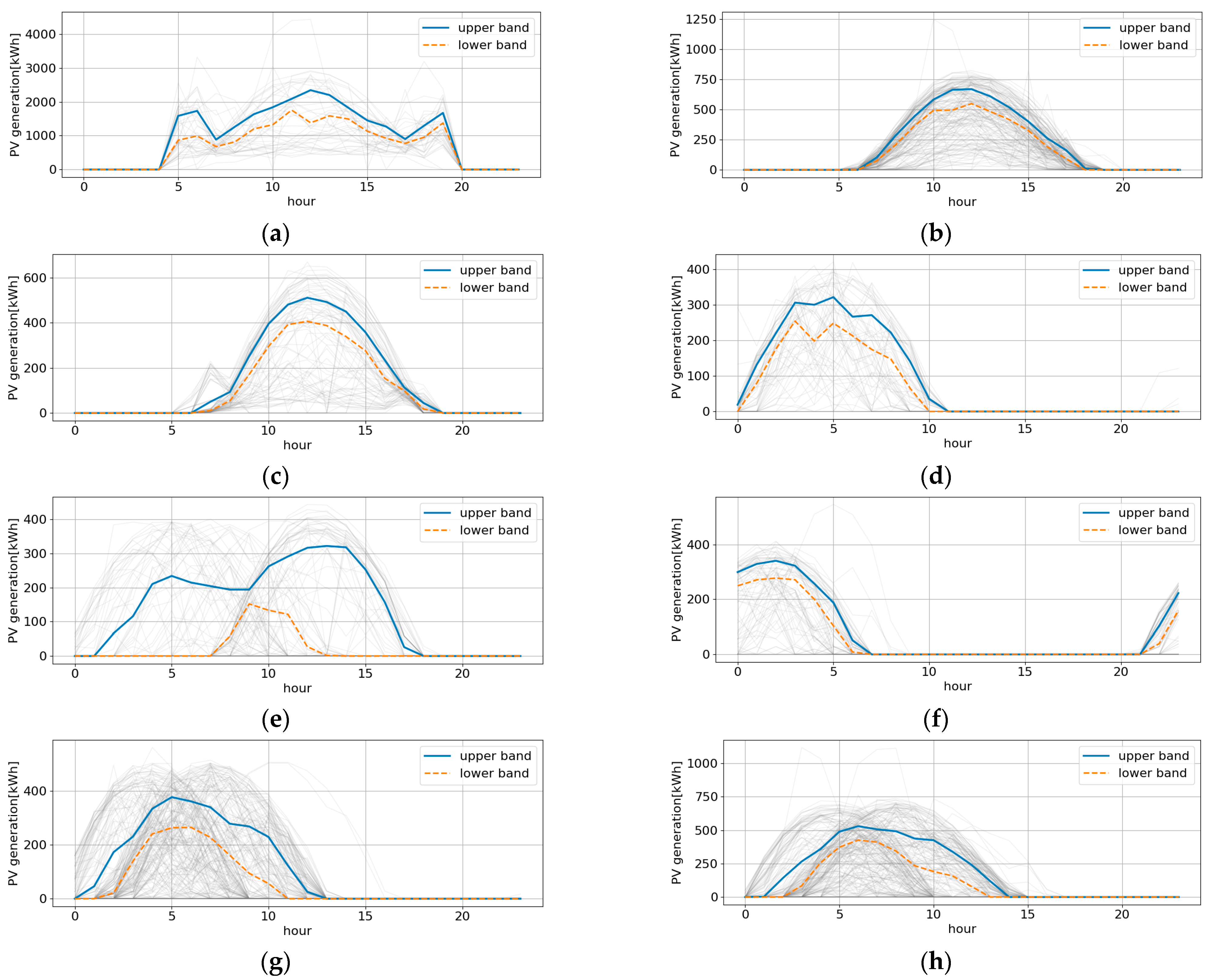

2. Proposed Method for Representative Pattern Generation

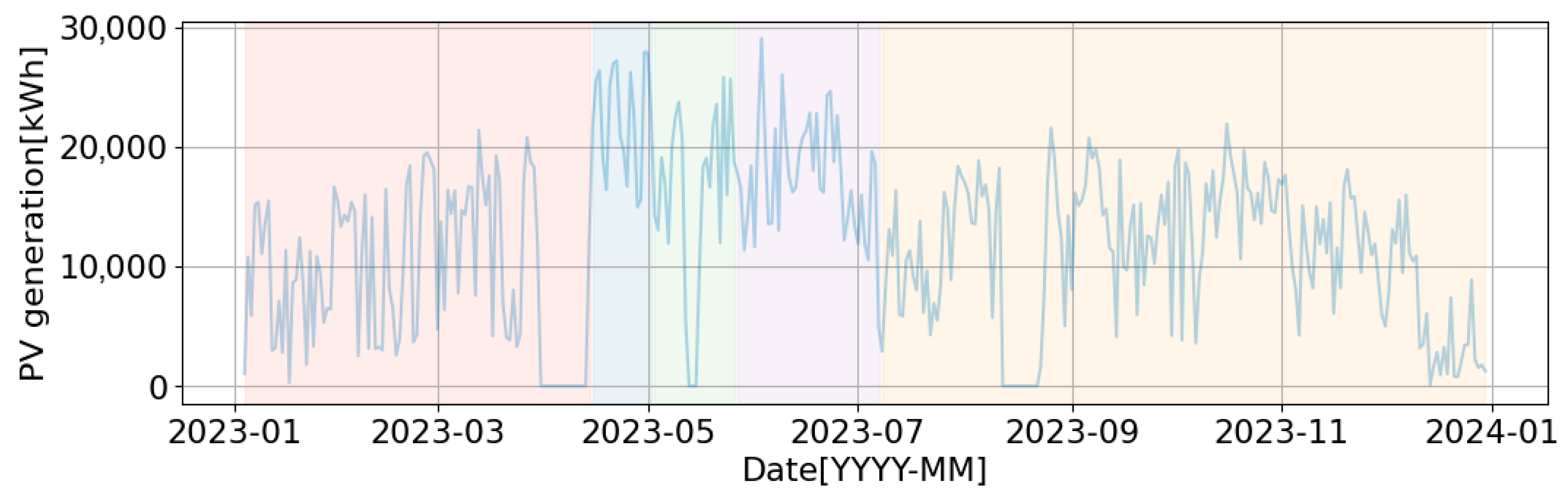

2.1. Data Preprocessing and Daily Profile Construction

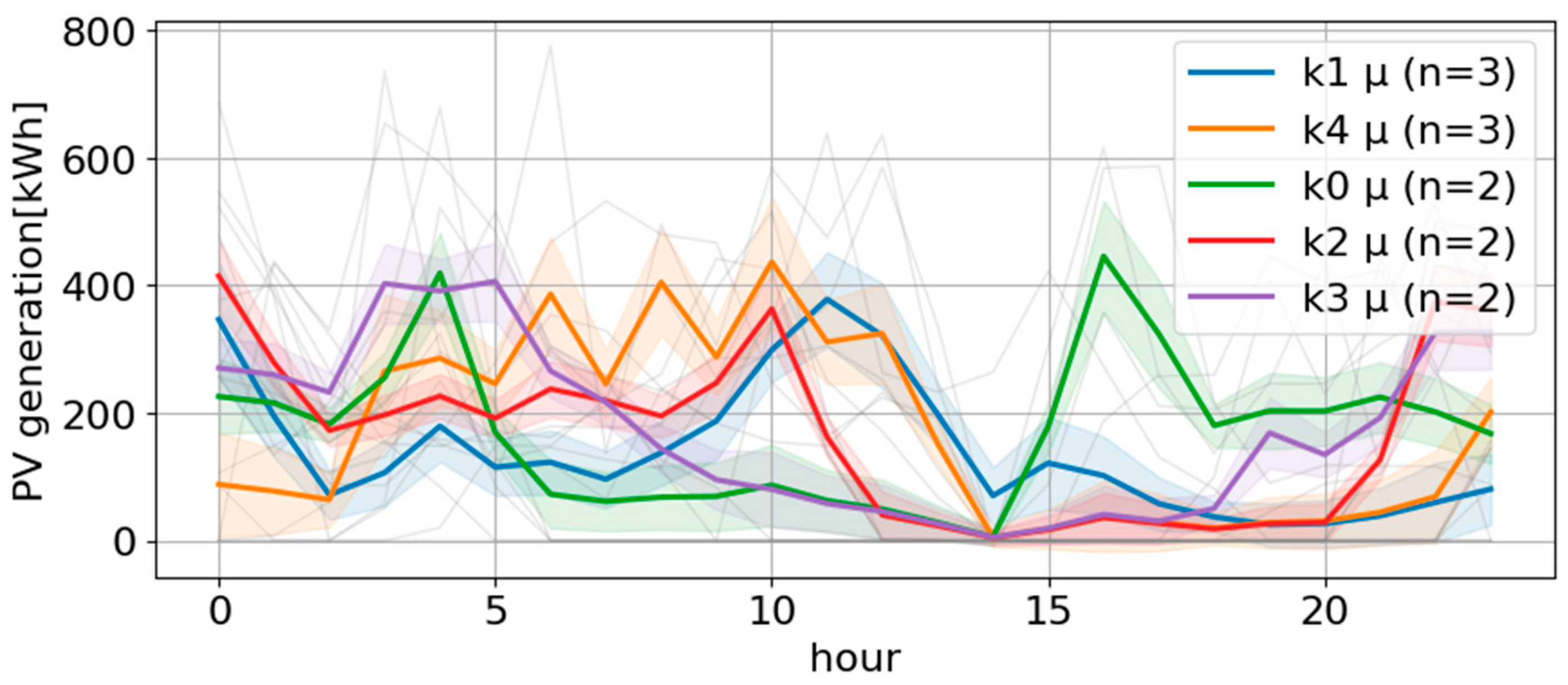

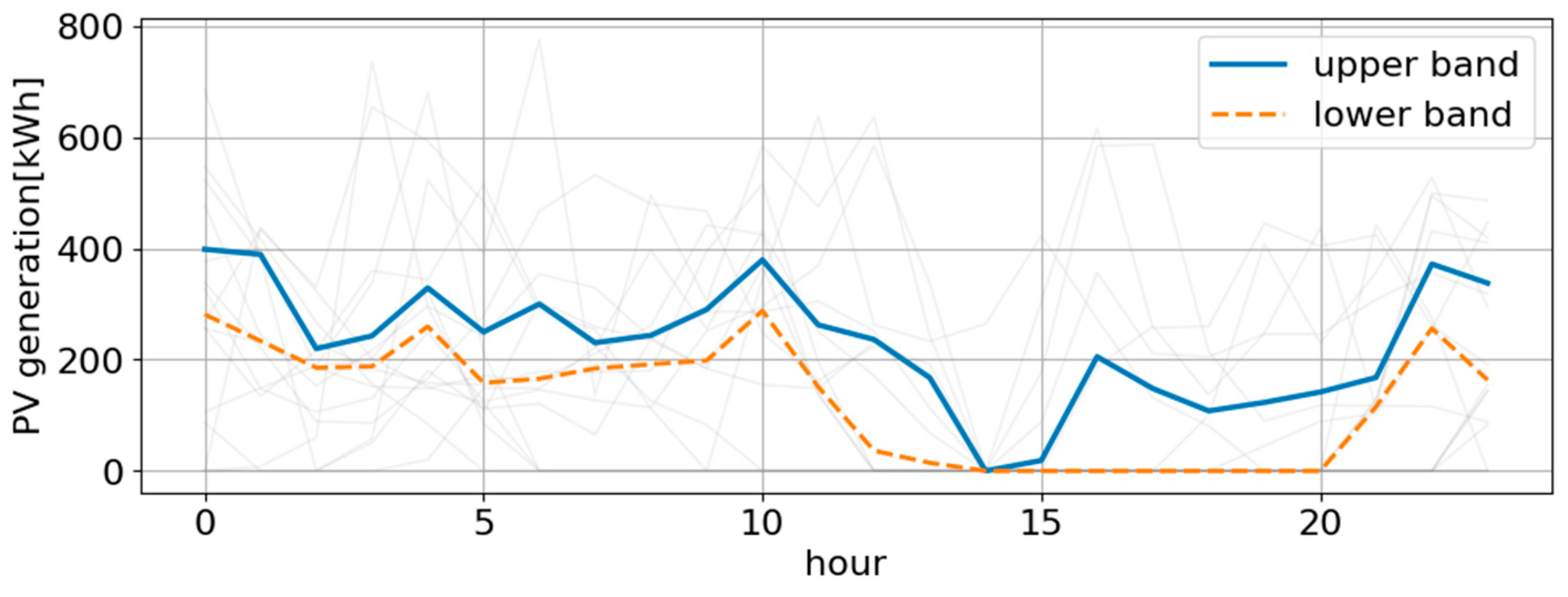

2.2. Blockwise Segmentation and Micro-Splitting

| Algorithm 1 Shape-based Segmentation with Micro-splits |

| Input: Daily 24 h normalized PV profiles Hyperparameters:

|

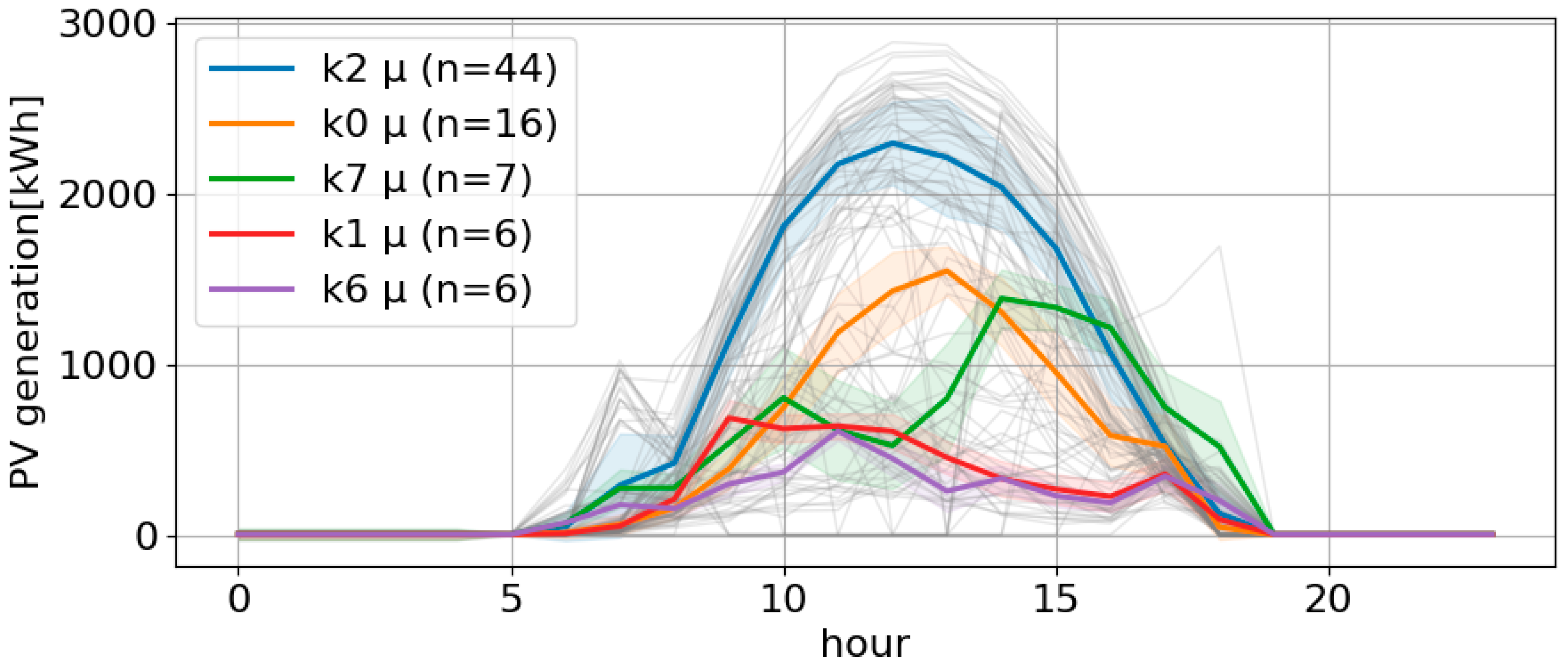

2.3. Probabilistic Clustering with BGMM

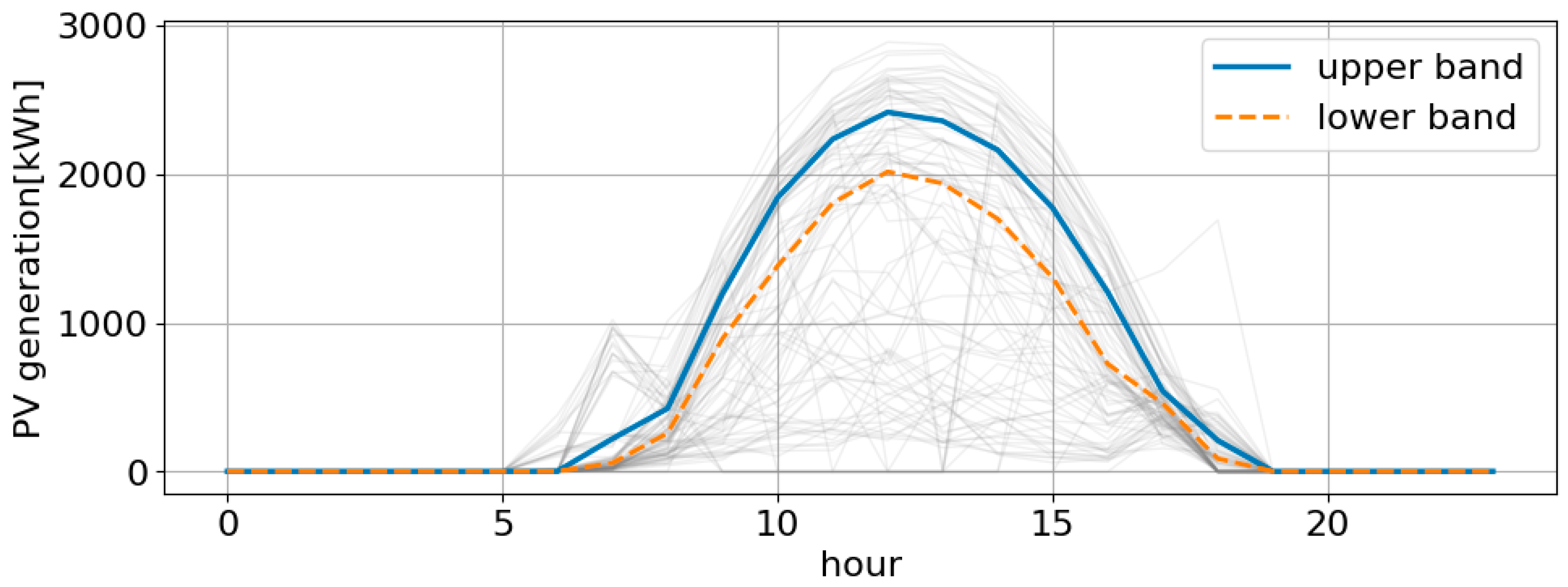

2.4. Optimized Representative Curve Generation

3. Experiments and Verification Results

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.2. Verification Metrics

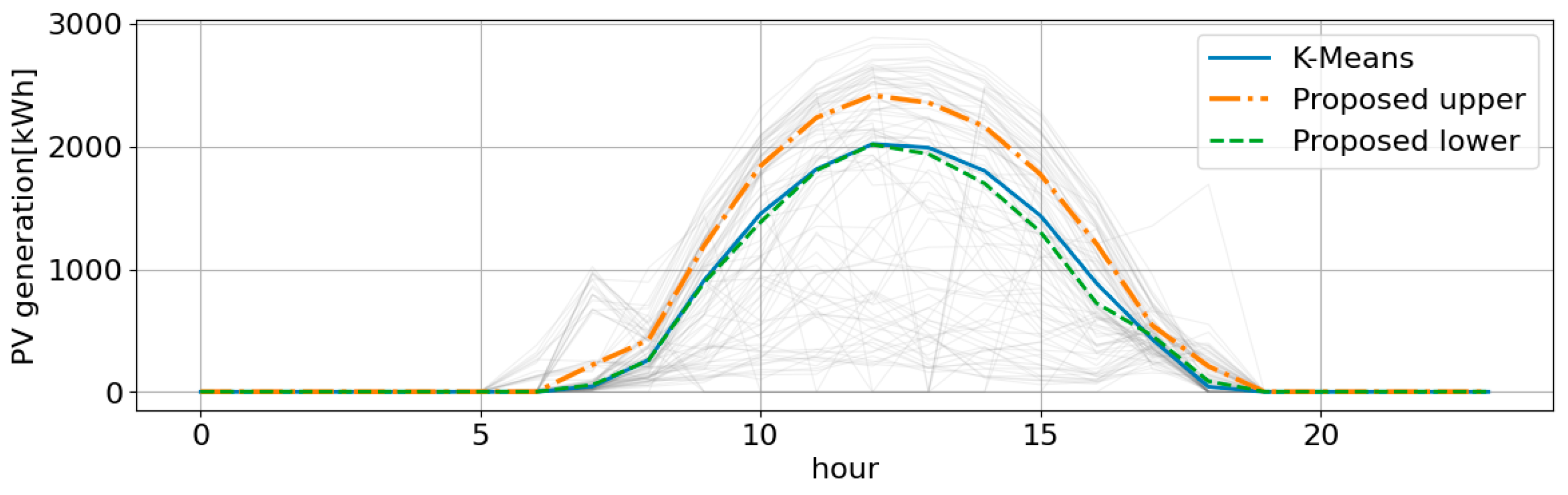

3.3. Verification Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Energy Highlights, July 2025; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, J.; Zu, Q.; Zhen, J.; Huang, X. Short-Term Forecasting and Uncertainty Analysis of Photovoltaic Power Based on the FCM-WOA-BILSTM Model. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 926774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichgraeber, H.; Brandt, A.R. Clustering Methods to Find Representative Periods for the Optimization of Energy Systems: An Initial Framework and Comparison. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, I.J.; Carvalho, P.M.S.; Botterud, A.; Silva, C.A. Clustering Representative Days for Power Systems Generation Expansion Planning: Capturing the Effects of Variable Renewables and Energy Storage. Appl. Energy 2019, 253, 113603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahmmacher, P.; Schmid, E.; Hirth, L.; Knopf, B. Carpe Diem: A Novel Approach to Select Representative Days for Long-Term Power System Modeling. Energy 2016, 112, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Sepahvand, M.; Tindemans, S.H. Representative Days and Hours with Piecewise Linear Transitions for Power System Planning. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 234, 110788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, S.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Han, X.; Teng, F. LSTM Auto-Encoder Based Representative Scenario Generation Method for Hybrid Hydro–PV Power System. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 5935–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganefar, A.; Amin-Naseri, M.R.; Sheikh-El-Eslami, M.K. Improvement of representative days selection in power system planning by incorporating the extreme days of the net load to take account of the variability and intermittency of renewable resources. Appl. Energy 2020, 272, 115224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, D.; Pal, A.; Augustin, P. Representative Scenarios to Capture Renewable Generation Stochasticity and Cross-Correlations. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Denver, CO, USA, 17–21 July 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbar, M.; Mallapragada, D.S. Representative period selection for power system planning using autoencoder-based dimensionality reduction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoto, Y.; Budhi, G.S.; Mingardi, S.F. Clustering-based assessment of solar irradiation and temperature attributes for PV power generation site selection: A case of Indonesia’s Java-Bali region. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2024, 13, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sioshansi, R.; Conejo, A.J. Hierarchical clustering to find representative operating periods for capacity-expansion modeling. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 3029–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythcke-Jørgensen, C.E.; Münster, M.; Ensinas, A.V.; Haglind, F. A method for aggregating external operating conditions in multi-generation system optimization models. Appl. Energy 2016, 166, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, H.; Li, W. Typical solar radiation year construction using k-means clustering and discrete-time Markov chain. Appl. Energy 2017, 205, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Arango, D.A.; Domeshek, M.; Wogrin, S.; Centeno, E. Enhanced representative days and system states modeling for energy storage investment analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 6534–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, E.; Teng, X.; Zhang, X.; Strbac, G.; Pudjianto, D. Data-driven representative day selection for investment decisions: A cost-oriented approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 2925–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichgraeber, H.; Brandt, A.R. Time-series aggregation for the optimization of energy systems: Goals, challenges, approaches, and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 111984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitiwi, D.Z.; Cuadra, F.; Olmos, L.; Rivier, M. A new approach of clustering operational states for power network expansion planning problems dealing with RES generation operational variability and uncertainty. Energy 2015, 90, 1360–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; He, C.; Liu, T.; Wu, L. Risk-averse stochastic midterm schedule of thermal-hydro-wind system: A network-constrained clustered unit commitment approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prompook, T.; Jittanon, S.; Phumeesut, K.; Termritthikun, C.; Ketjoy, N.; Chamsa-Ard, W.; Meesuk, N.; Madtharad, C.; Suriwong, T. Impact of distance measures in adaptive K-means clustering on load profiles and spatial patterns of distributed substations in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, C.; Oudre, L.; Vayatis, N. Selective Review of Change Point Detection Methods. Signal Process 2020, 167, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoe, H.; Chiba, S. Dynamic Programming Algorithm Optimization for Spoken Word Recognition. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1978, 26, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Jordan, M.I. Variational Inference for Dirichlet Process Mixtures. Bayesian Anal. 2006, 1, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E. The Infinite Gaussian Mixture Model. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Solla, S.A., Leen, T.K., Müller, K.-R., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 554–560. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multi objective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockafellar, R.T.; Uryasev, S. Conditional Value-at-Risk for General Loss Distributions. J. Bank. Financ. 2002, 26, 1443–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Nahavandi, S.; Creighton, D.; Atiya, A.F. Comprehensive Review of Neural Network-Based Prediction Intervals and New Advances. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2011, 22, 1341–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokcesu, K.; Gokcesu, H. Nonparametric Extrema Analysis in Time Series for Envelope Extraction, Peak Detection and Clustering. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.02082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Block | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1 | Block1 | 0.7864 | 0.4574 | 0.0927 | 0.0568 |

| Block2 | 0.8375 | 0.4801 | 0.0557 | 0.0555 | |

| Block3 | 0.8216 | 0.4941 | 0.0493 | 0.0476 | |

| Block4 | 0.8615 | 0.4901 | 0.0630 | 0.0714 | |

| Block5 | 0.8936 | 0.5970 | 0.0324 | 0.0546 | |

| Section 2 | Block1 | 0.7895 | 0.5772 | 0.0713 | 0.0493 |

| Block2 | 0.8330 | 0.4862 | 0.0740 | 0.0666 | |

| Block3 | 0.8623 | 0.4922 | 0.0630 | 0.0714 | |

| Block4 | 0.8758 | 0.5844 | 0.1142 | 0.0545 | |

| Section 3 | Block1 | 0.8665 | 0.7146 | 0.0860 | 0.0769 |

| Block2 | 0.8846 | 0.7509 | 0.0920 | 0.1000 | |

| Block3 | 0.8635 | 0.6977 | 0.0898 | 0.0799 | |

| Block4 | 0.8120 | 0.6410 | 0.0584 | 0.0543 | |

| Block5 | 0.8901 | 0.7128 | 0.0774 | 0.0869 | |

| Block6 | 0.8624 | 0.6771 | 0.0883 | 0.0645 | |

| Block7 | 0.8989 | 0.6829 | 0.1053 | 0.0506 | |

| Section 4 | Block1 | 0.8202 | 0.6885 | 0.0576 | 0.0520 |

| Block2 | 0.8844 | 0.6478 | 0.0541 | 0.0513 | |

| Section 5 | Block1 | 0.7964 | 0.6249 | 0.0909 | 0.0495 |

| Block2 | 0.8798 | 0.5857 | 0.0571 | 0.0520 | |

| Section 6 | Block1 | 0.8072 | 0.5773 | 0.0384 | 0.0493 |

| Block2 | 0.8319 | 0.4836 | 0.0740 | 0.0666 | |

| Block3 | 0.8615 | 0.4901 | 0.0630 | 0.0714 | |

| Block4 | 0.8993 | 0.6020 | 0.0330 | 0.0548 | |

| Section 7 | Block1 | 0.7579 | 0.5414 | 0.0310 | 0.0555 |

| Block2 | 0.8615 | 0.4935 | 0.0630 | 0.0714 | |

| Block3 | 0.8917 | 0.6069 | 0.0402 | 0.0430 | |

| Section 8 | Block1 | 0.8386 | 0.6568 | 0.0961 | 0.0587 |

| Block2 | 0.8772 | 0.7970 | 0.1081 | 0.1000 | |

| Block3 | 0.8056 | 0.7471 | 0.0429 | 0.0540 | |

| Block4 | 0.8531 | 0.5765 | 0.0586 | 0.0625 | |

| Block5 | 0.8440 | 0.6358 | 0.0828 | 0.0574 | |

| Block6 | 0.8825 | 0.6838 | 0.0250 | 0.0581 | |

| Section 9 | Block1 | 0.7802 | 0.5257 | 0.0529 | 0.0555 |

| Block2 | 0.8637 | 0.4944 | 0.0630 | 0.0714 | |

| Block3 | 0.8900 | 0.6077 | 0.0361 | 0.0435 | |

| Section 10 | Block1 | 0.8398 | 0.6101 | 0.0540 | 0.0588 |

| Block2 | 0.8157 | 0.5262 | 0.1026 | 0.0000 | |

| Block3 | 0.7534 | 0.3575 | 0.0673 | 0.0625 | |

| Block4 | 0.8727 | 0.5151 | 0.0063 | 0.0540 | |

| Section 11 | Block1 | 0.9448 | 0.9219 | 0.0821 | 0.0769 |

| Block2 | 0.8905 | 0.8698 | 0.1107 | 0.1000 | |

| Block3 | 0.8151 | 0.5466 | 0.0980 | 0.0549 | |

| Block4 | 0.9027 | 0.7113 | 0.0726 | 0.0517 | |

| Section 12 | Block1 | 0.7830 | 0.5861 | 0.0269 | 0.0555 |

| Block2 | 0.8654 | 0.5026 | 0.0630 | 0.0714 | |

| Block3 | 0.8911 | 0.6171 | 0.0371 | 0.0432 | |

| Average | 0.8497 | 0.6035 | 0.0659 | 0.0605 | |

| Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | 0.7864 | 0.4574 | 0.0927 | 0.0568 |

| K-means | 0.5511 | 0.5511 | 0.8019 | 0.6943 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, G.; Kim, J.-H. Distribution-Level PV Representative Bands: Blockwise BGMM and NSGA-II for Coverage and Tail-Risk. Energies 2025, 18, 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236134

Kim G, Kim J-H. Distribution-Level PV Representative Bands: Blockwise BGMM and NSGA-II for Coverage and Tail-Risk. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236134

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Geonho, and Jun-Hyeok Kim. 2025. "Distribution-Level PV Representative Bands: Blockwise BGMM and NSGA-II for Coverage and Tail-Risk" Energies 18, no. 23: 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236134

APA StyleKim, G., & Kim, J.-H. (2025). Distribution-Level PV Representative Bands: Blockwise BGMM and NSGA-II for Coverage and Tail-Risk. Energies, 18(23), 6134. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236134