Design and Investigation of a Low-Cogging-Torque and High-Torque-Density Double-Sided Permanent Magnet Motor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Motor Structure and Theoretical Analysis

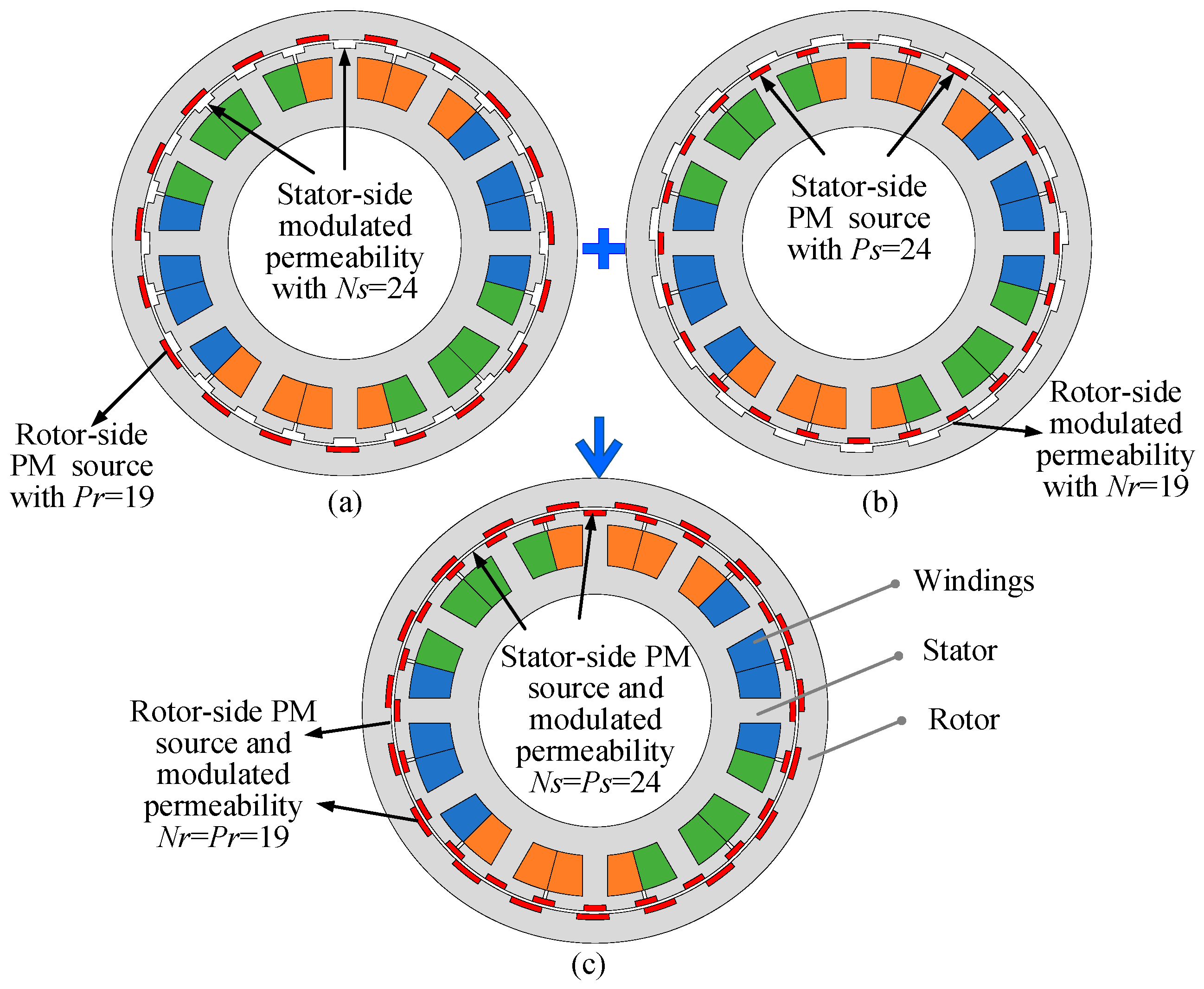

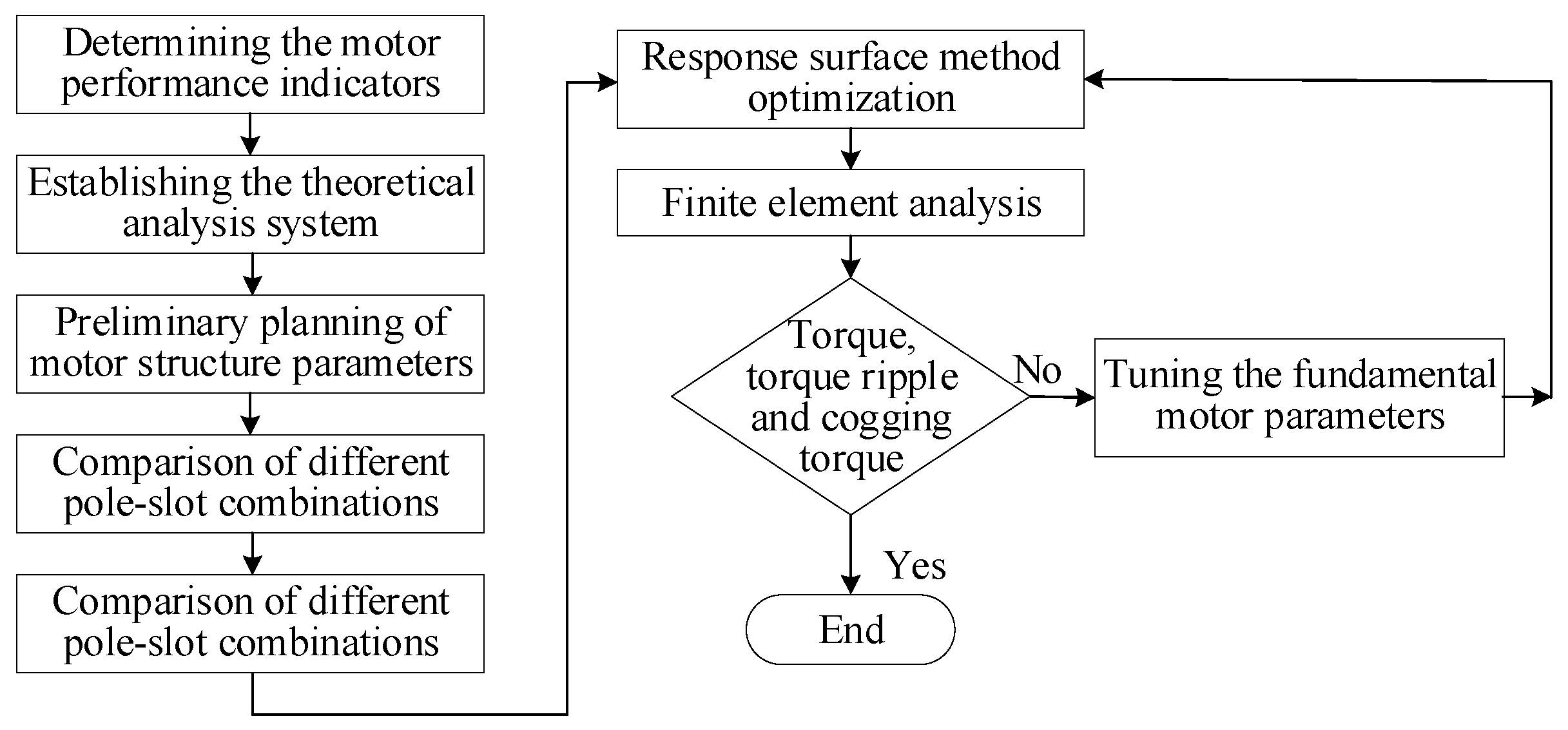

2.1. Schematic Diagram of DS-PMFM Motor and Methodology

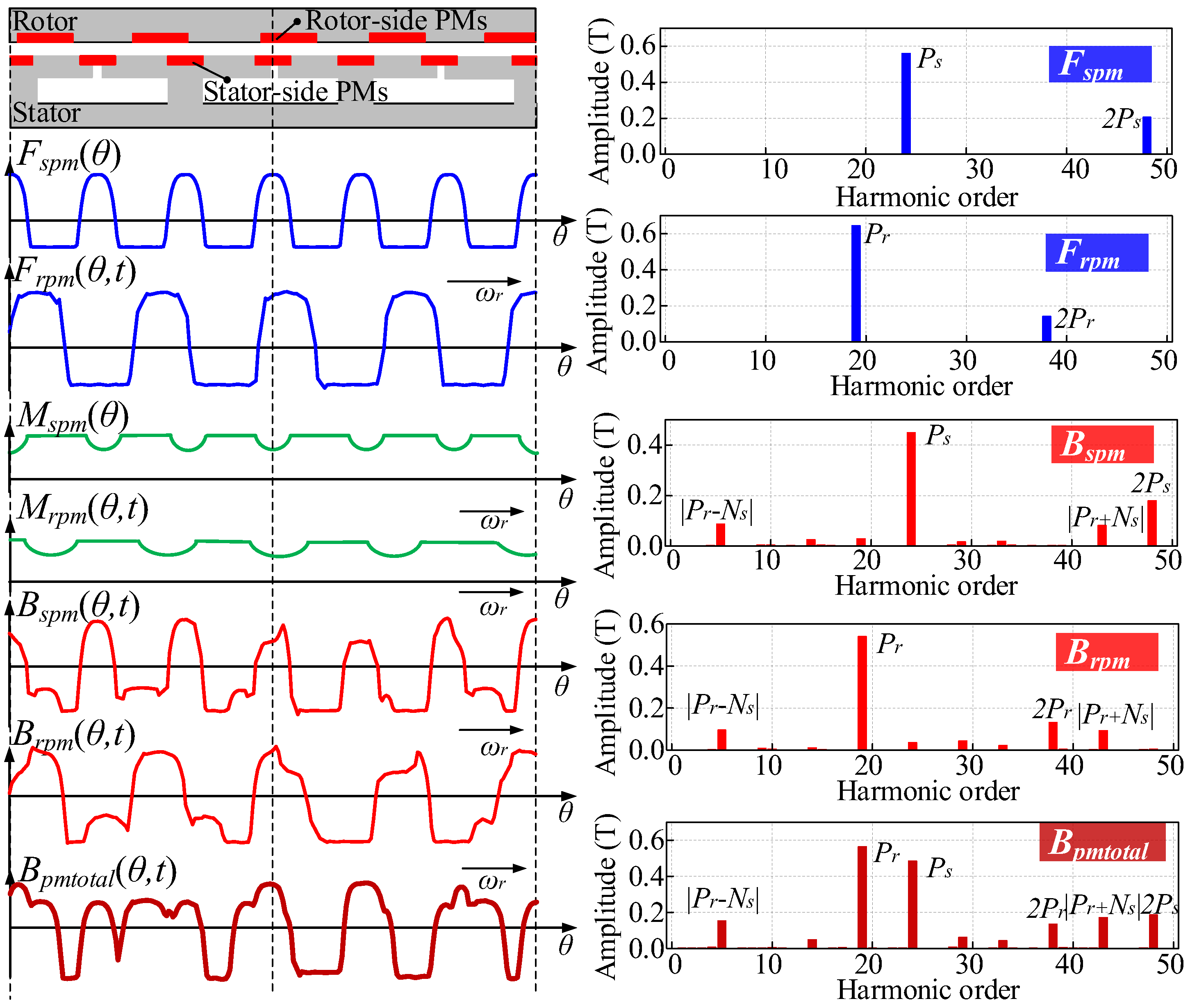

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

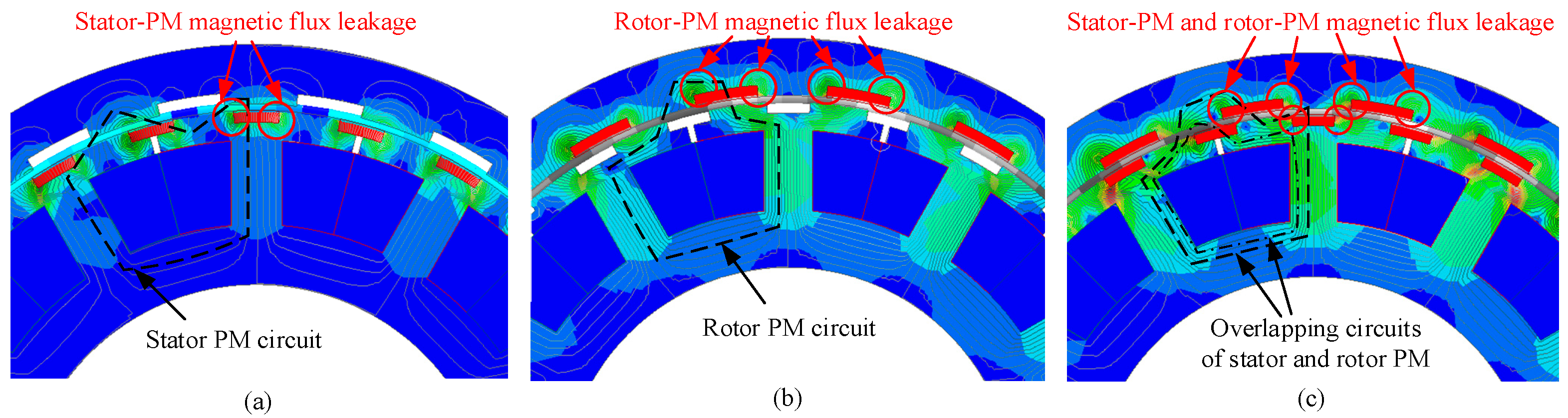

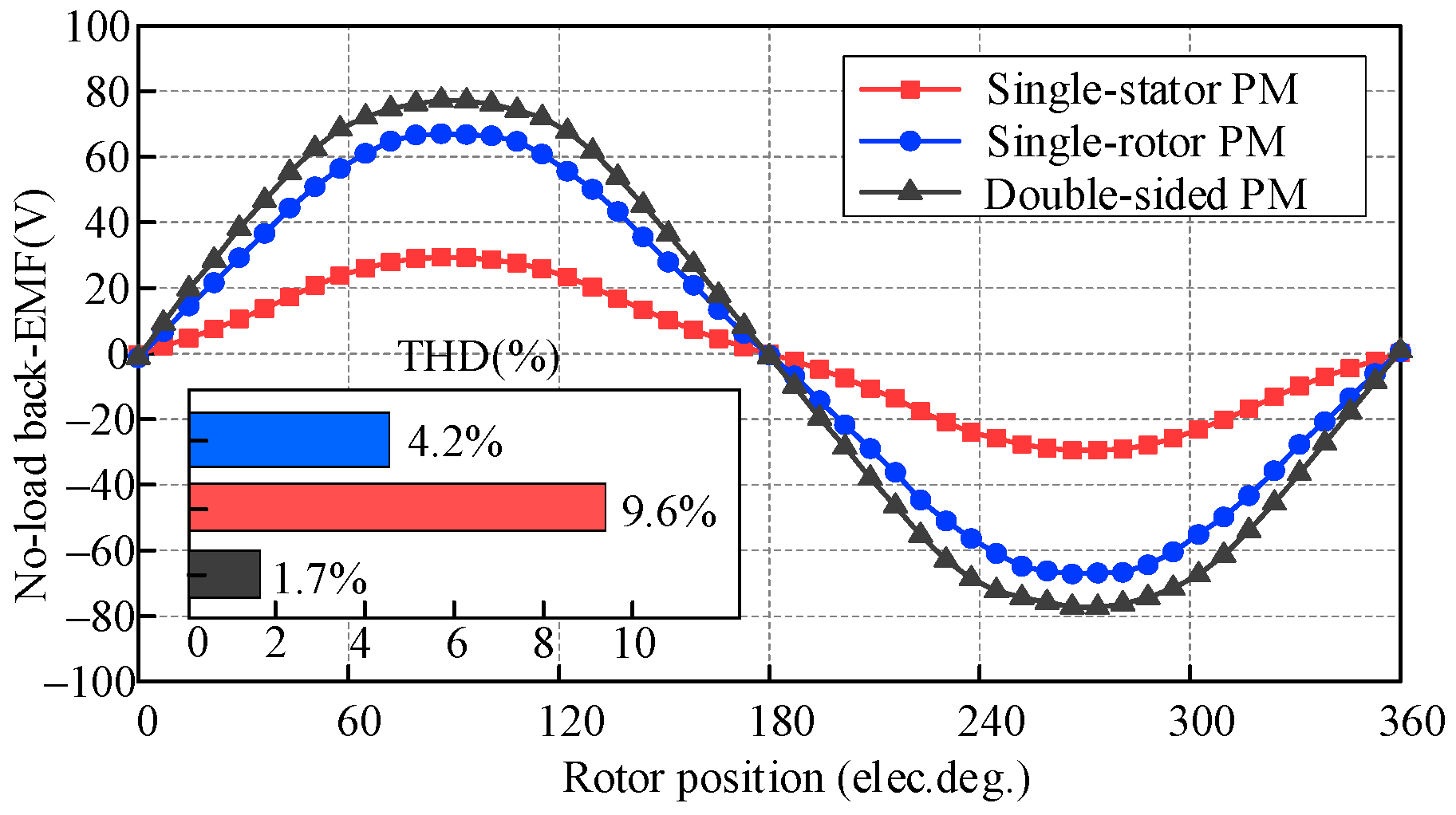

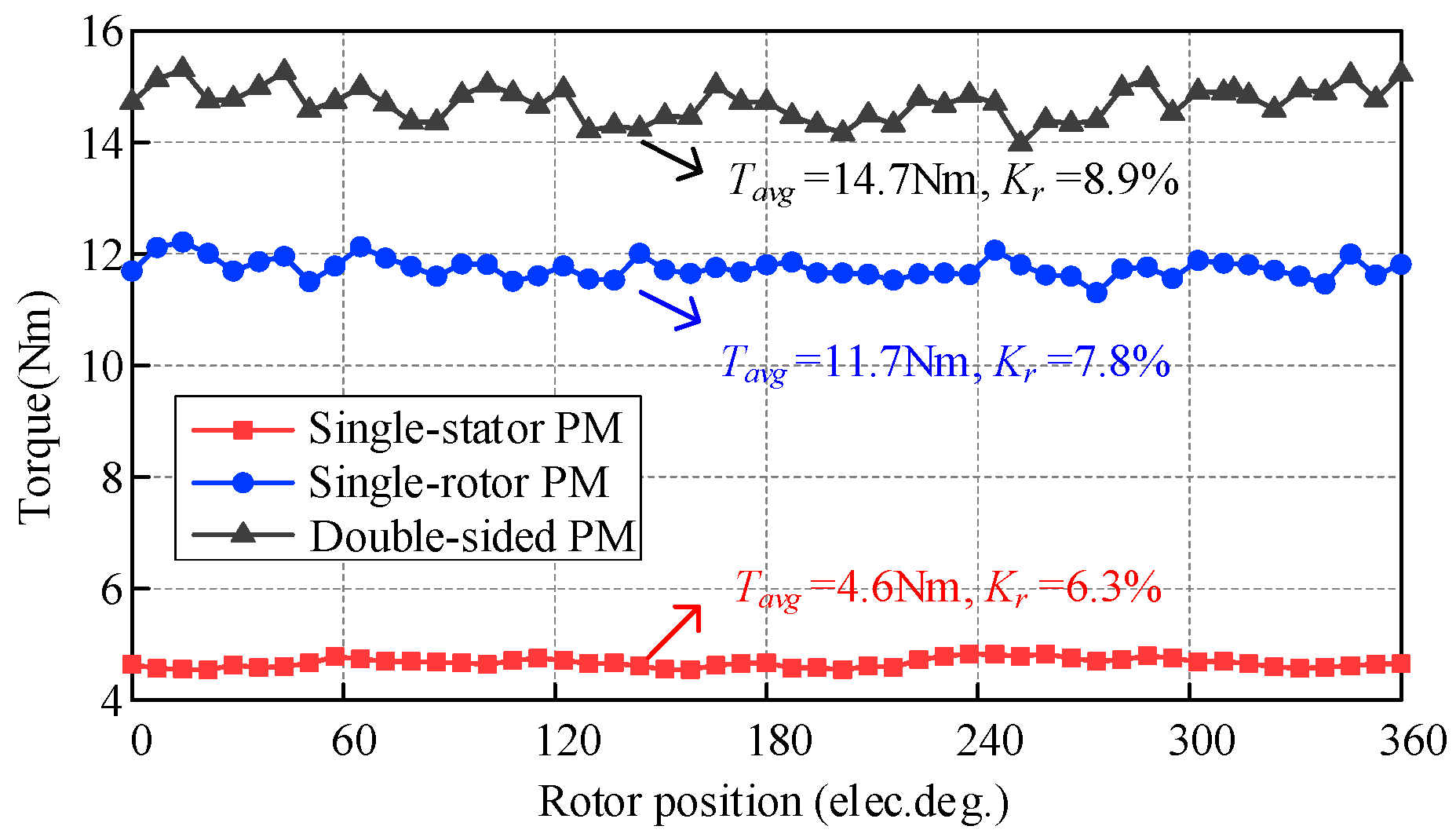

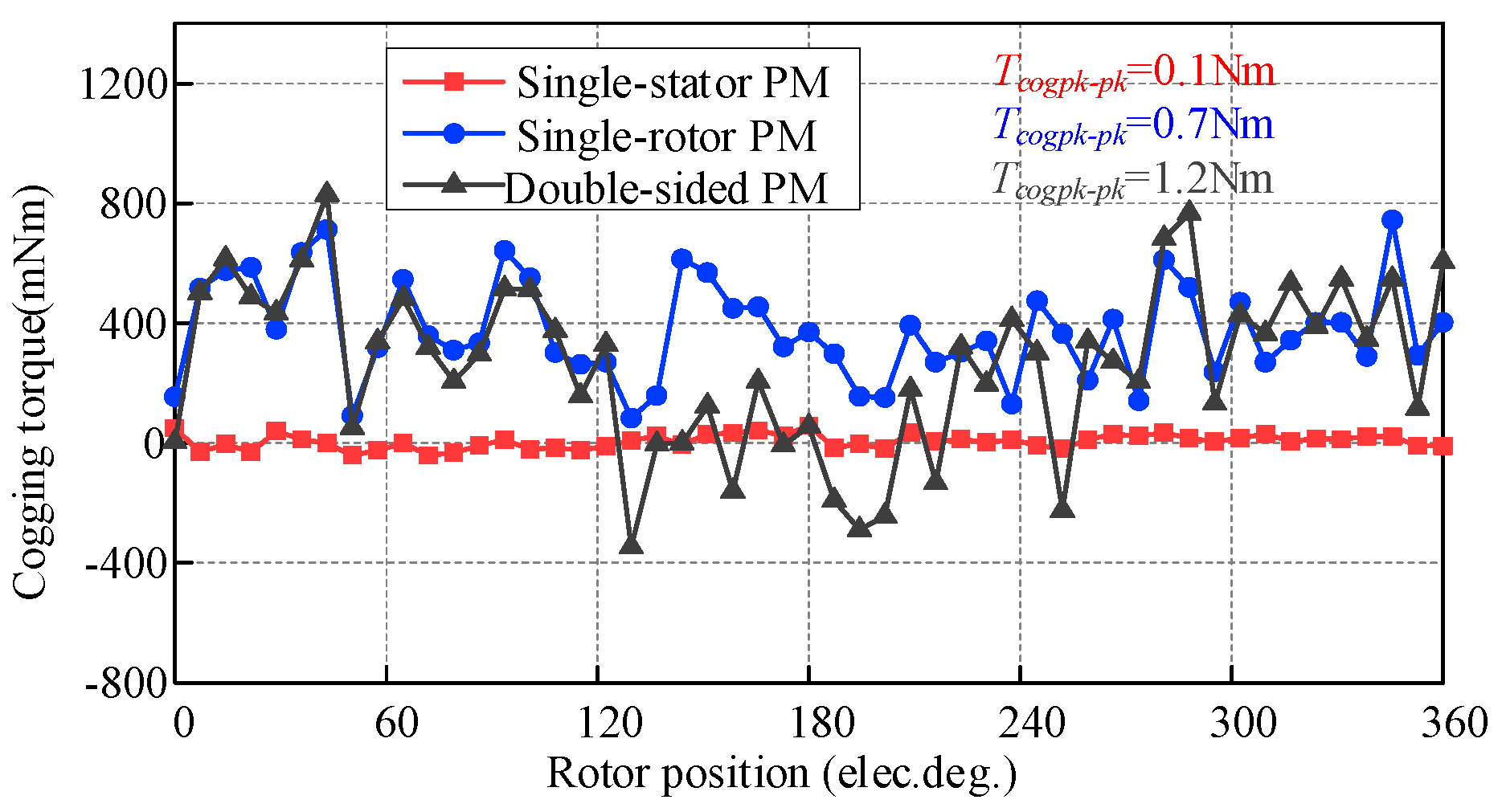

2.3. Comparison of Performance of DS-PMFM Motor and SS-PMFM Motor

3. Design Method of DS-PMFM Motor with Low Cogging Torque

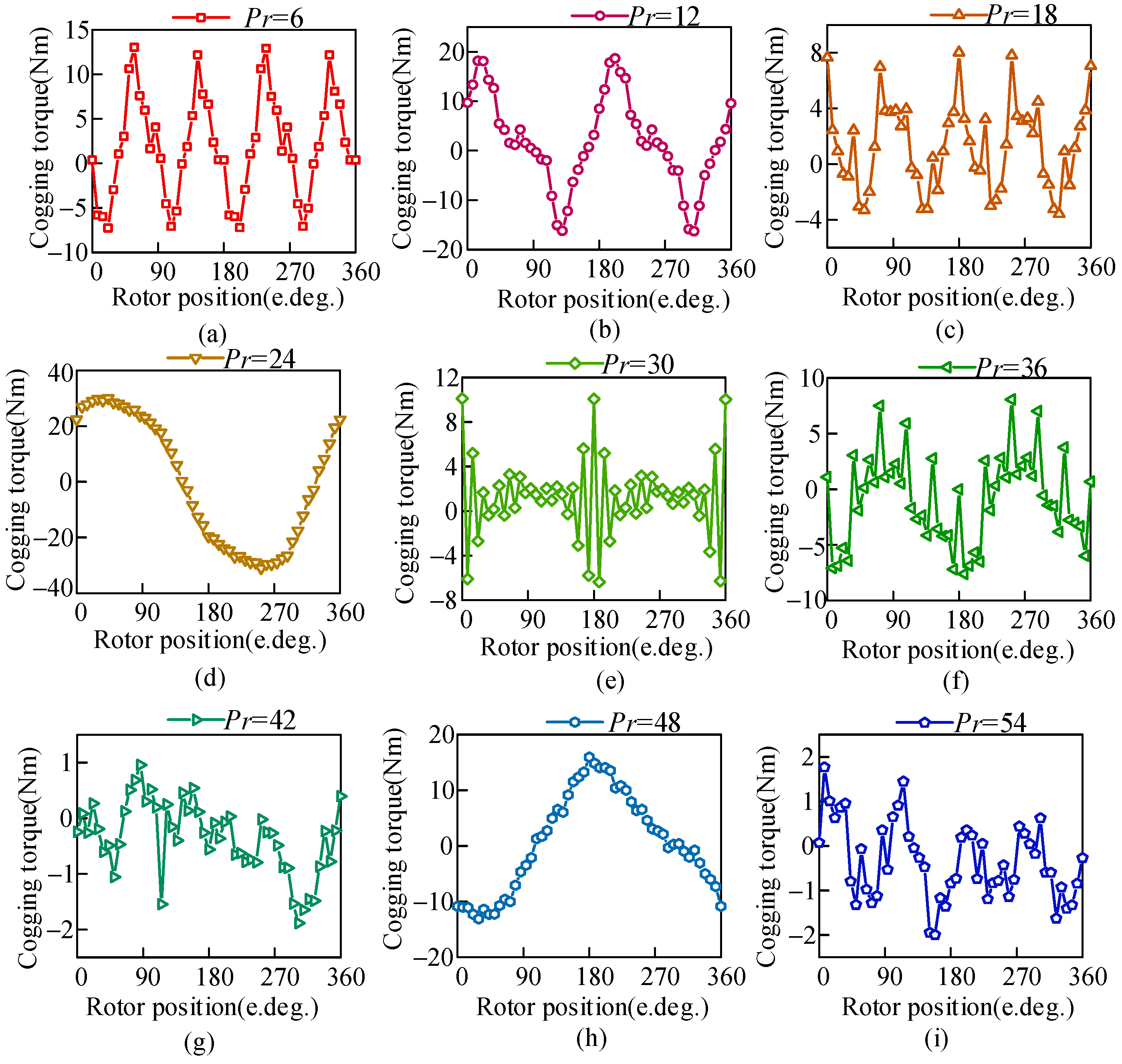

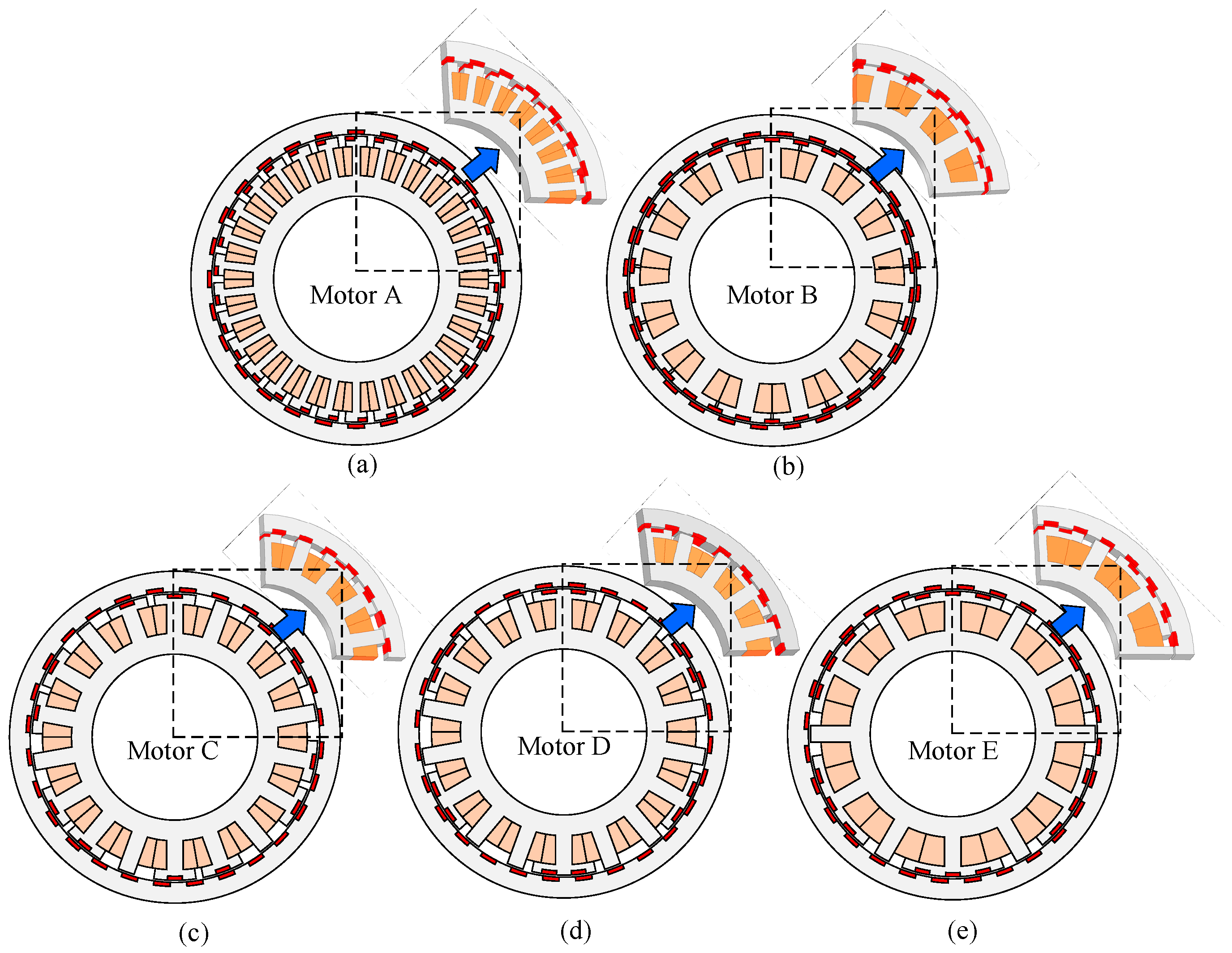

3.1. Variation Law of Cogging Torque in DS-PMFM Motor

3.2. The Design of Pole Slot Ratio and Tooth Slot Structure

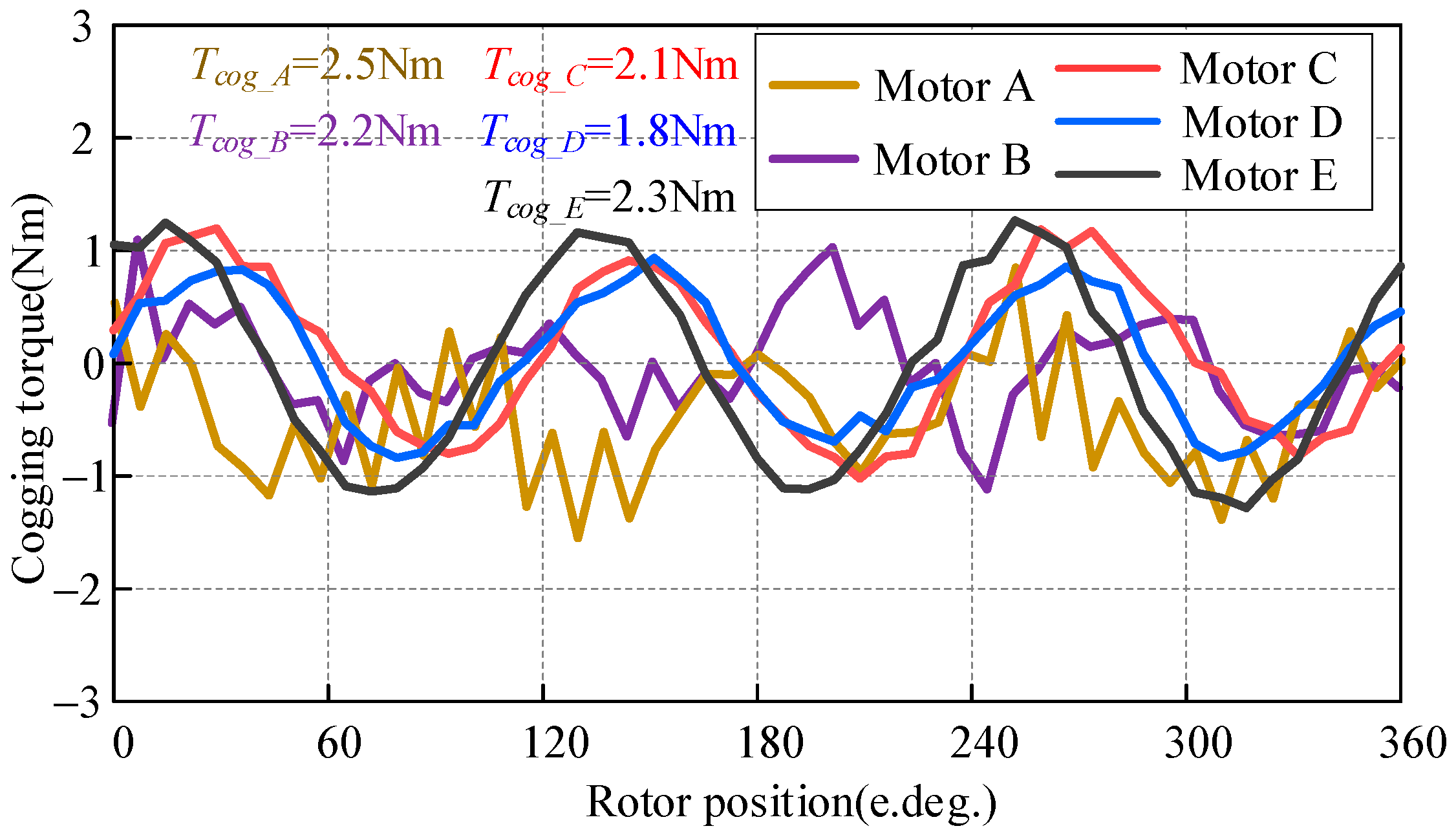

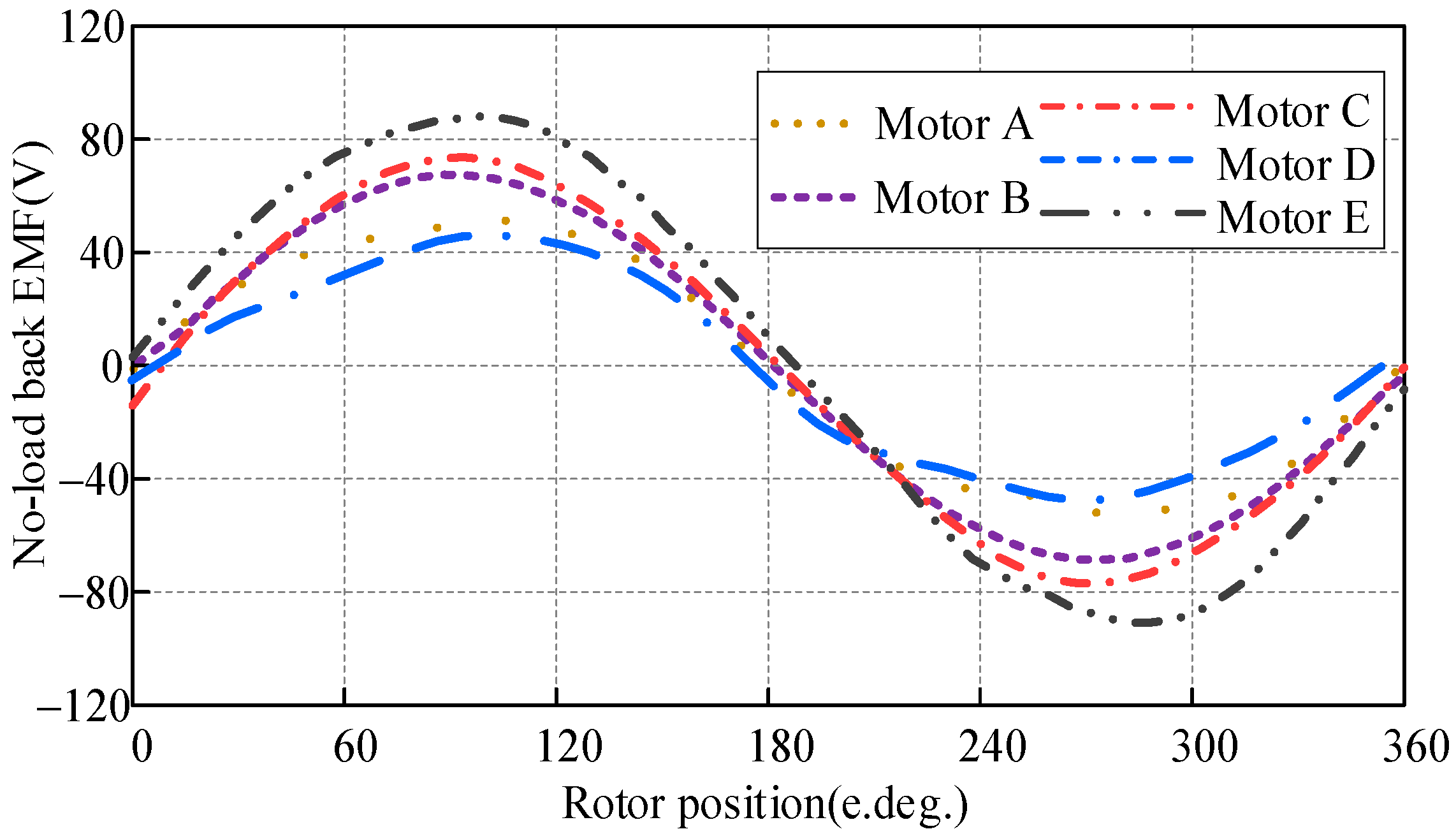

3.3. Discussion About the Cogging Torque Characteristic of Proposed Motors

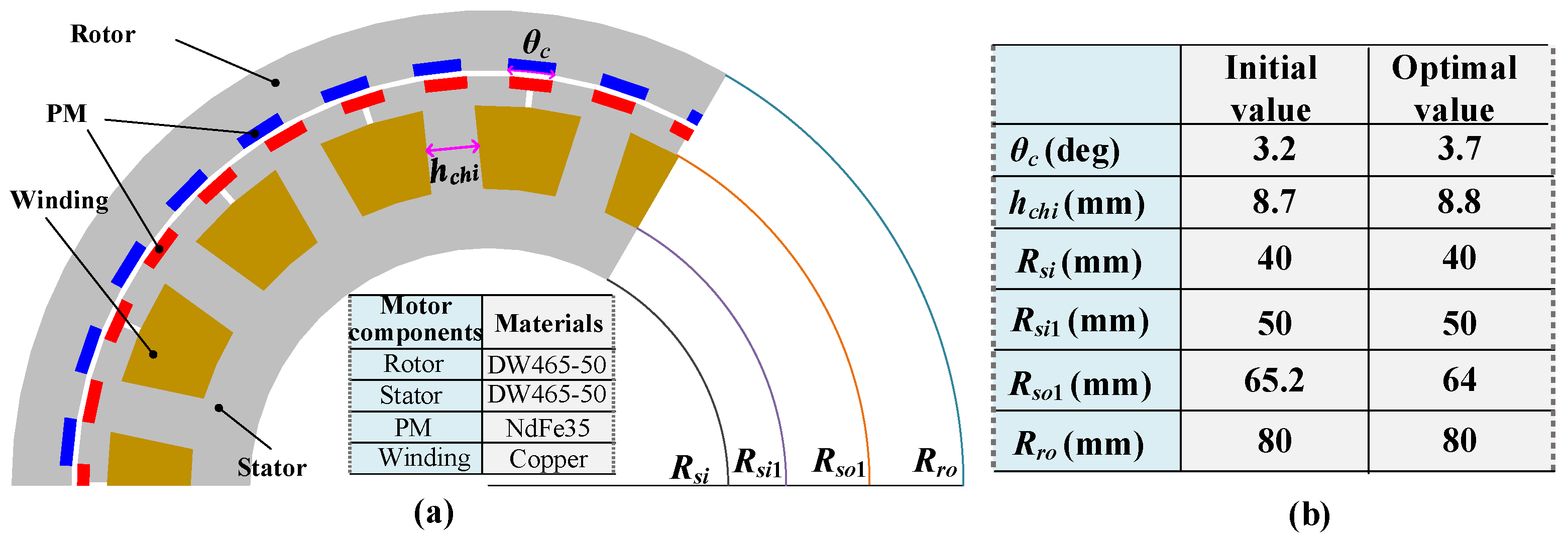

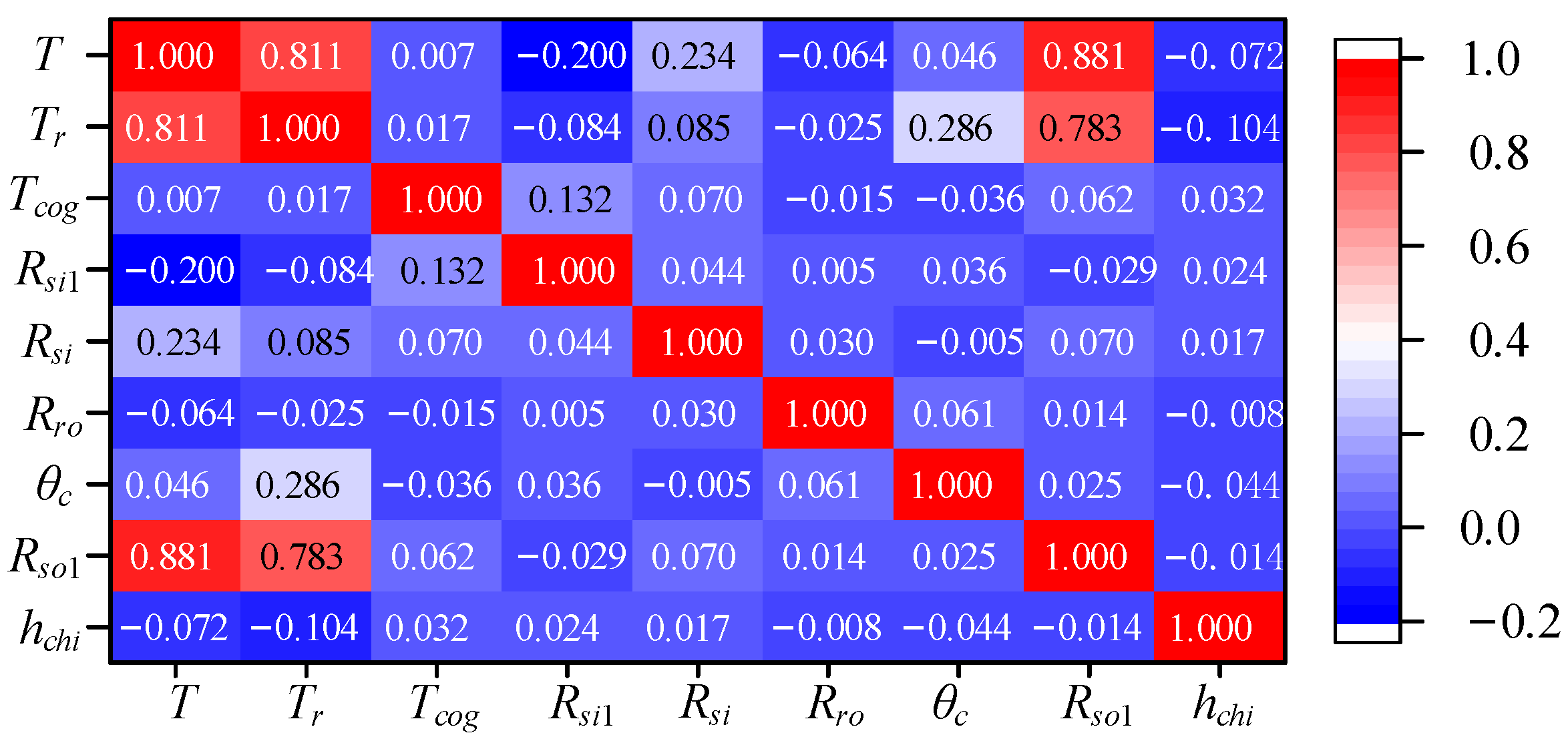

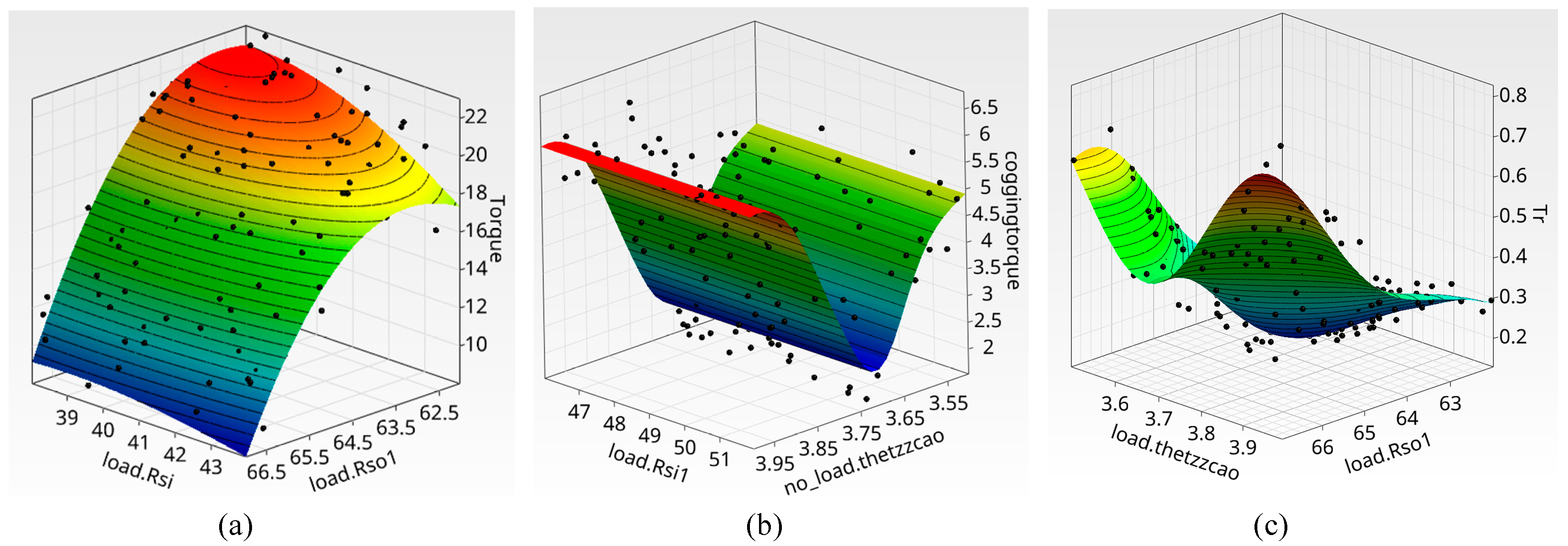

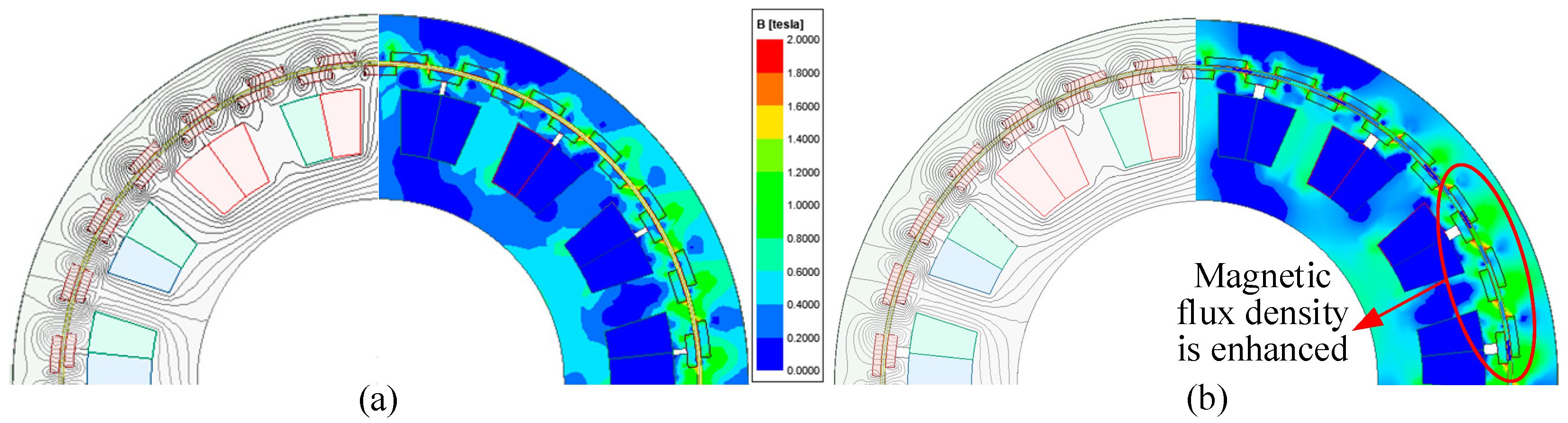

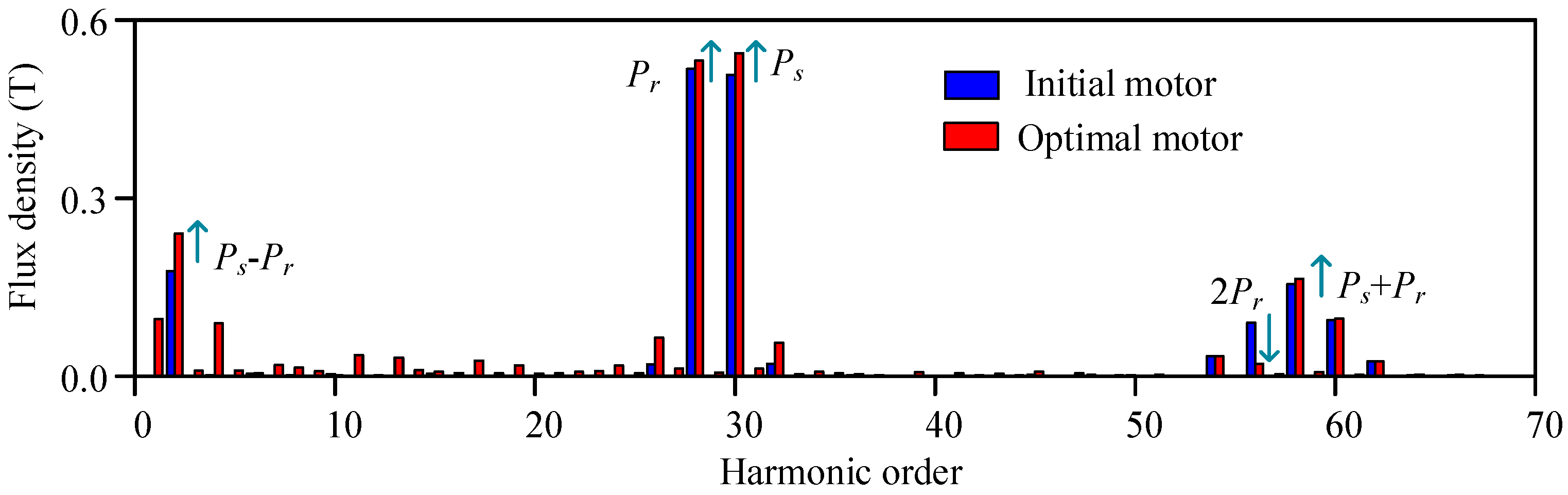

4. Design Method of DS-PMFM Motor with High Torque Density

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The DS-PMFM motor causes a non-negligible deterioration of cogging torque and torque ripple while increasing the output torque compared with the single-sided permanent magnet (SS-PMFM) motor;

- (2)

- After adopting the stator modulation pole split-tooth design, the number of stator modulation teeth and the number of stator teeth of the motor are inconsistent, making it possible for the motor to simultaneously meet the high Nc and small amplitude of cogging torque harmonic;

- (3)

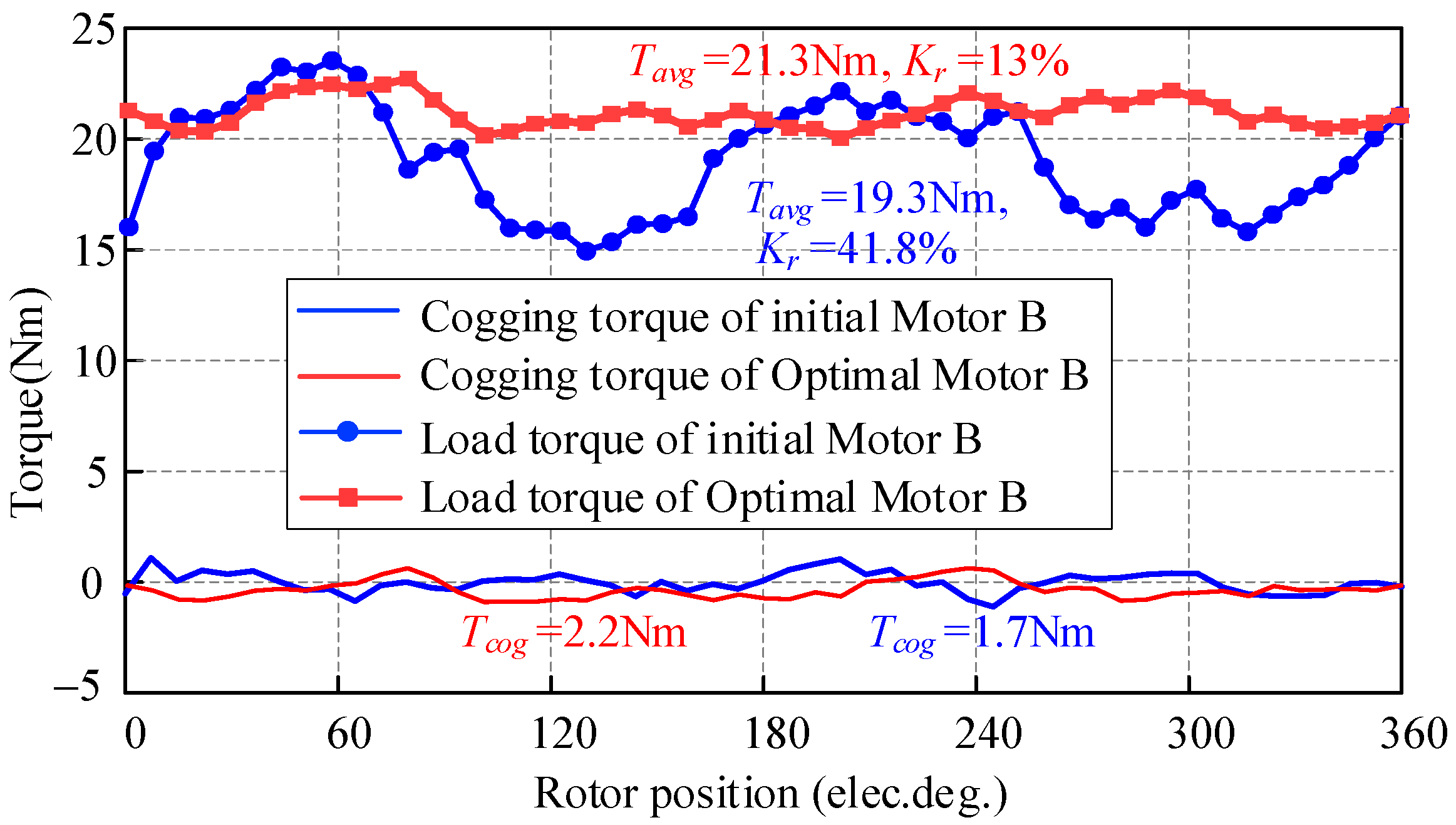

- The adoption of the rotor unequal-width modulation pole design can effectively improve the motor torque performance. The torque is increased by 10% and the torque ripple is decreased by 70% while the cogging torque is reduced by 23%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Ns | Number of stator modulation teeth |

| Ps | Number of stator permanent magnets |

| Pa | Number of pole pairs of the armature winding |

| Fspm1 | Amplitude of the fundamental harmonic component of the stator-side PM MMF |

| Ms0 | DC component of the stator permeability |

| Ms1 | Fundamental harmonic of the stator permeability |

| Pr | Pole pairs of the rotor PMs |

| Nr | Number of rotor teeth |

| Mr0 | DC component of the rotor permeability |

| Ms1 | Fundamental harmonic of the rotor permeability |

| ωr | Rotor rotating speed |

| Ls | Axial length of the motor |

| Rair | Air-gap radius of the motor |

| μ0 | Vacuum permeability |

| Zs | Number of stator teeth |

| Nc | Minimum number of periods |

References

- Nory, H.; Yildiz, A.; Aksun, S.; Aksoy, C. Design and Analysis of an IE6 Hyper-Efficiency Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor for Electric Vehicle Applications. Energies 2025, 18, 4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y. Overview of Deadbeat Predictive Control Technology for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor System. Energies 2025, 18, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Yan, L.; Liu, X.; He, X.; Du, N.; Wang, H. Structural Topology Design for Electromagnetic Performance Enhancement of Permanent-Magnet Machines. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 38, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Zhang, Y.; Song, B.; Xu, K.; Feng, C.; Qi, S. High-Torque-Density Composite-Cooled Axial Flux Electrically Excited Synchronous Motor. Energies 2025, 18, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Pei, Y.; Chai, F.; Doppelbauer, M. Performance Comparison Between Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor and Vernier Motor for In-Wheel Direct Drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 7761–7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Jiang, M.; Xiang, Z.; Quan, L.; Hua, W.; Cheng, M. Design and Optimization of A Flux-Modulated Permanent Magnet Motor Based on An Airgap-Harmonic-Orientated Design Methodology. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 5337–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhu, X. Torque Ripple Suppression of a PM Vernier Machine from Perspective of Time and Space Harmonic Magnetic Field. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 10150–10161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhu, X.; Xiang, Z.; Zheng, S.; Fan, D. Dual-Sub-Region Rotor Design of a Permanent Magnet Hub Motor with Enhanced Speed Regulation and Output Torque for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 13659–13669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Du, Y.; Xiao, F.; Zhu, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, C. Comprehensive Performance Improvement of Permanent Magnet Vernier Motor for Electric Tractors. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 4821–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Yan, L.; Ge, L.; He, X.; Du, N.; Liu, X. Development of a Radial-Flux Machine with Multi-Shaped Magnet Rotor and Non-Ferromagnetic Yoke for Low Torque Ripple and Rotor Mass. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 2897–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Hou, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z. Comparative Study of Yokeless Stator Axial-Flux PM Machines Having Fractional Slot Concentrated and Integral Slot Distributed Windings for Electric Vehicle Traction Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, D.; Ren, X.; Qu, R. A Novel Permanent Magnet Vernier Machine with Coding-Shaped Tooth. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 6058–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, X.; Quan, L.; Fan, D.; Liu, Q. Research on Characteristic Airgap Harmonics of a Double-Rotor Flux-Modulated PM Motor Based on Harmonic Dimensionality Reduction. IEEE Trans. Transport. Electrific. 2024, 10, 5750–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhao, X.; Cai, F.; Wu, Q.; Pang, J.; Guo, X. Design of a Dual-Permanent-Magnet Vernier Machine to Replace Conventional Surface-Mounted Permanent Magnet Motor for Direct-Drive Industrial Turbine Application. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 2291–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Yan, L.; Guo, Y.; He, X.; Gerada, C.; Chen, I. A Concentrated-Flux-Type PM Machine with Irregular Magnets and Iron Poles. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 29, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, D.; Qu, R. Torque Improvement of Vernier Permanent Magnet Machine with Larger Rotor Pole Pairs Than Stator Teeth Number. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 12648–12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Yan, Y.; Wang, S.; Onn, B.C.S.; Gajanayake, C.J.; Gupta, A.K.; Lee, C.H.T. Investigation of a Flux-Switching Machine with U-V-Array Permanent Magnet Arrangement for Traction Applications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 12580–12591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Deng, F. Design and Optimization of a High-Torque-Density Low-Torque-Ripple Vernier Machine Using Ferrite Magnets for Direct-Drive Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 5421–5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zheng, J.; Ji, J.; Zhu, S.; Kang, M. Star and Delta Hybrid Connection of a FSCW PM Machine for Low Space Harmonics. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 65, 9266–9279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Jia, S.; Yang, D.; Liang, D. Comparative Study of Novel Dual Winding Dual Magnet Flux-Modulated Machines with Different Stator/Rotor Pole Combinations. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 9691–9700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fu, W.; Niu, S.; Zhao, X. Comparative Analysis of Different Permanent Magnet Arrangements in a Novel Flux Modulated Electric Machine. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 14437–14445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, T. Analysis of a Fault-Tolerant Dual-Permanent-Magnet Vernier Machine with Hybrid Stator. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 6559–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pa | Ns | Pr | PR | LCM (Pr, Ns)/Pr | Pa | Ns | Pr | PR | LCM (Pr, Ns)/Pr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 20 | 18 | 9 | 10 | 3 | 20 | 17 | 5.7 | 20 |

| 22 | 20 | 10 | 11 | 22 | 19 | 6.3 | 22 | ||

| 24 | 22 | 11 | 12 | 24 | 21 | 7 | 8 | ||

| 26 | 24 | 12 | 13 | 26 | 23 | 7.7 | 26 | ||

| 28 | 26 | 13 | 14 | 28 | 25 | 8.3 | 28 | ||

| 30 | 28 | 14 | 15 | 30 | 27 | 9 | 10 | ||

| 4 | 20 | 16 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 15 | 3 | 4 |

| 22 | 18 | 4.5 | 11 | 22 | 17 | 3.4 | 22 | ||

| 24 | 20 | 5 | 6 | 24 | 19 | 3.8 | 24 | ||

| 26 | 22 | 5.5 | 13 | 26 | 21 | 4.2 | 26 | ||

| 28 | 24 | 6 | 7 | 28 | 23 | 4.6 | 28 | ||

| 30 | 26 | 6.5 | 15 | 30 | 25 | 5 | 6 |

| Motor | LCM (Pr, Zs)/Pr | Tcogpk-pk/Spm (Nm/mm2) | U0max/Spm (V/mm2) | Pr-th (T) | Pa-th (T) | Pr + Ns-th (T) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor A | 15 | 0.0035 | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Motor B | 15 | 0.0025 (−28.5%) | 0.12 (+33%) | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Motor C | 15 | 0.0028 (−20%) | 0.12 (+33%) | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Motor D | 9 | 0.0017 (−51.4%) | 0.08 (−11.1%) | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Motor E | 3 | 0.0029 (−17.1%) | 0.14 (+55%) | 0.51 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Motor | Spm (mm2) | Tavg/Spm (Nm/mm2) | Torque Density (Nm/L) | Core Loss (W) | Solid Loss (W) | Power Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial motor | 873.4 | 0.0221 | 19.2 | 112.2 | 10.5 | 0.61 |

| Optimal motor | 873.4 | 0.0243 | 21.2 | 105.8 | 13.7 | 0.68 |

| Item | Value | Item | Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| The outer radius of the rotor | 80 mm | Rotor | DW465-50 |

| The inner radius of the rotor | 70 mm | Stator | DW465-50 |

| The outer radius of the stator | 69 mm | PM | NdFe-35 |

| The height of the stator split tooth | 5 mm | Winding | Copper |

| The width of the stator yoke | 10 mm | Stack length | 50 mm |

| The inner radius of the stator | 40 mm | Pr | 28 |

| The width of the stator’s straight teeth | 8.8 mm | PS | 30 |

| The thickness of the rotor PM | 1.76 mm | Rated speed | 600 rpm |

| The thickness of the stator PM | 2 mm | Rated current | 10 A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Gui, S. Design and Investigation of a Low-Cogging-Torque and High-Torque-Density Double-Sided Permanent Magnet Motor. Energies 2025, 18, 5995. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225995

Zhou Y, Xiang Z, Liu Q, Gui S. Design and Investigation of a Low-Cogging-Torque and High-Torque-Density Double-Sided Permanent Magnet Motor. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5995. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225995

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yuting, Zixuan Xiang, Qian Liu, and Suiyuan Gui. 2025. "Design and Investigation of a Low-Cogging-Torque and High-Torque-Density Double-Sided Permanent Magnet Motor" Energies 18, no. 22: 5995. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225995

APA StyleZhou, Y., Xiang, Z., Liu, Q., & Gui, S. (2025). Design and Investigation of a Low-Cogging-Torque and High-Torque-Density Double-Sided Permanent Magnet Motor. Energies, 18(22), 5995. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225995