Joint Optimization Scheduling of Electric Vehicles and Electro–Olefin–Hydrogen Electromagnetic Energy Supply Device for Wind–Solar Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Challenges of the Problem

1.2. Research Motivation and Existing Shortcomings

1.3. The Main Contribution of This Article

- (1)

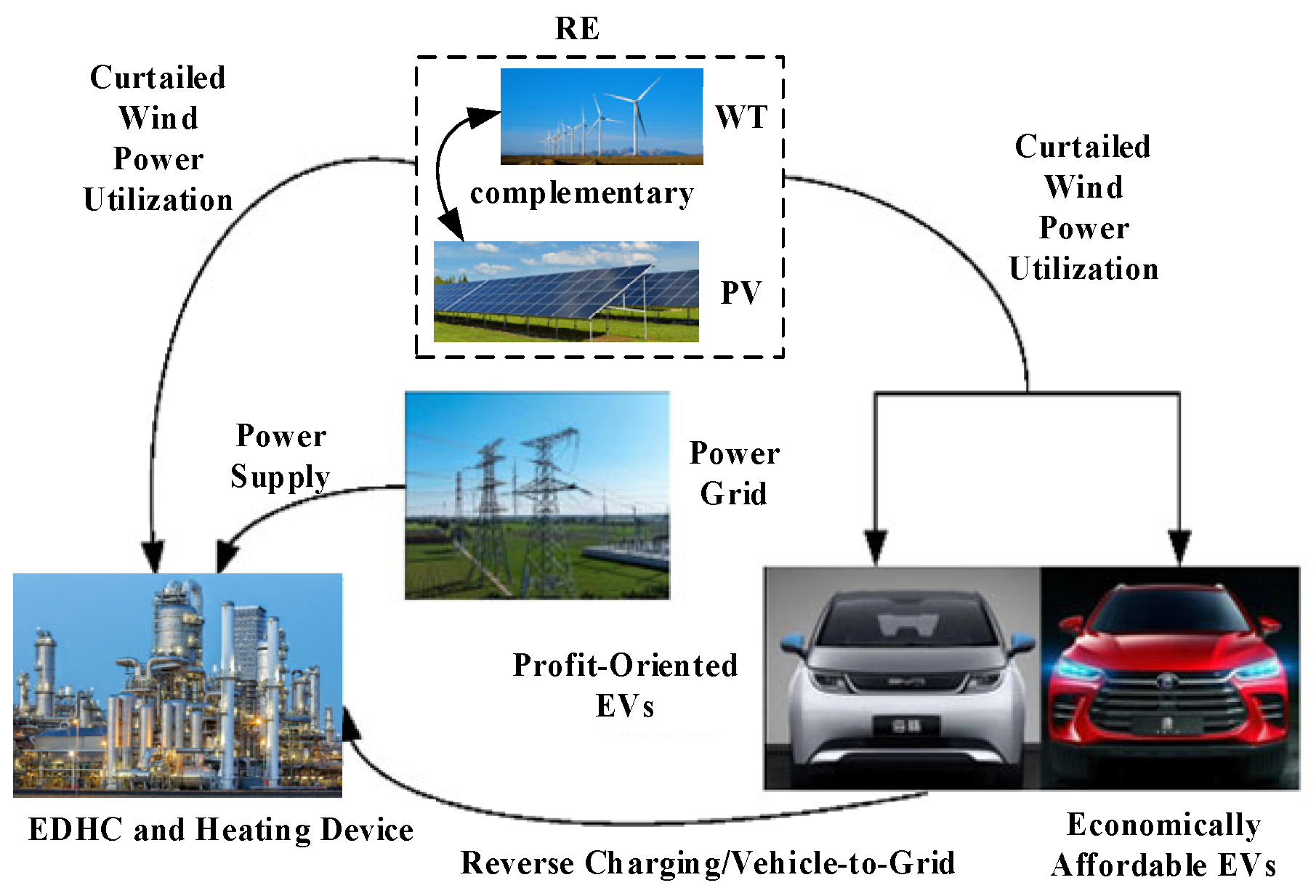

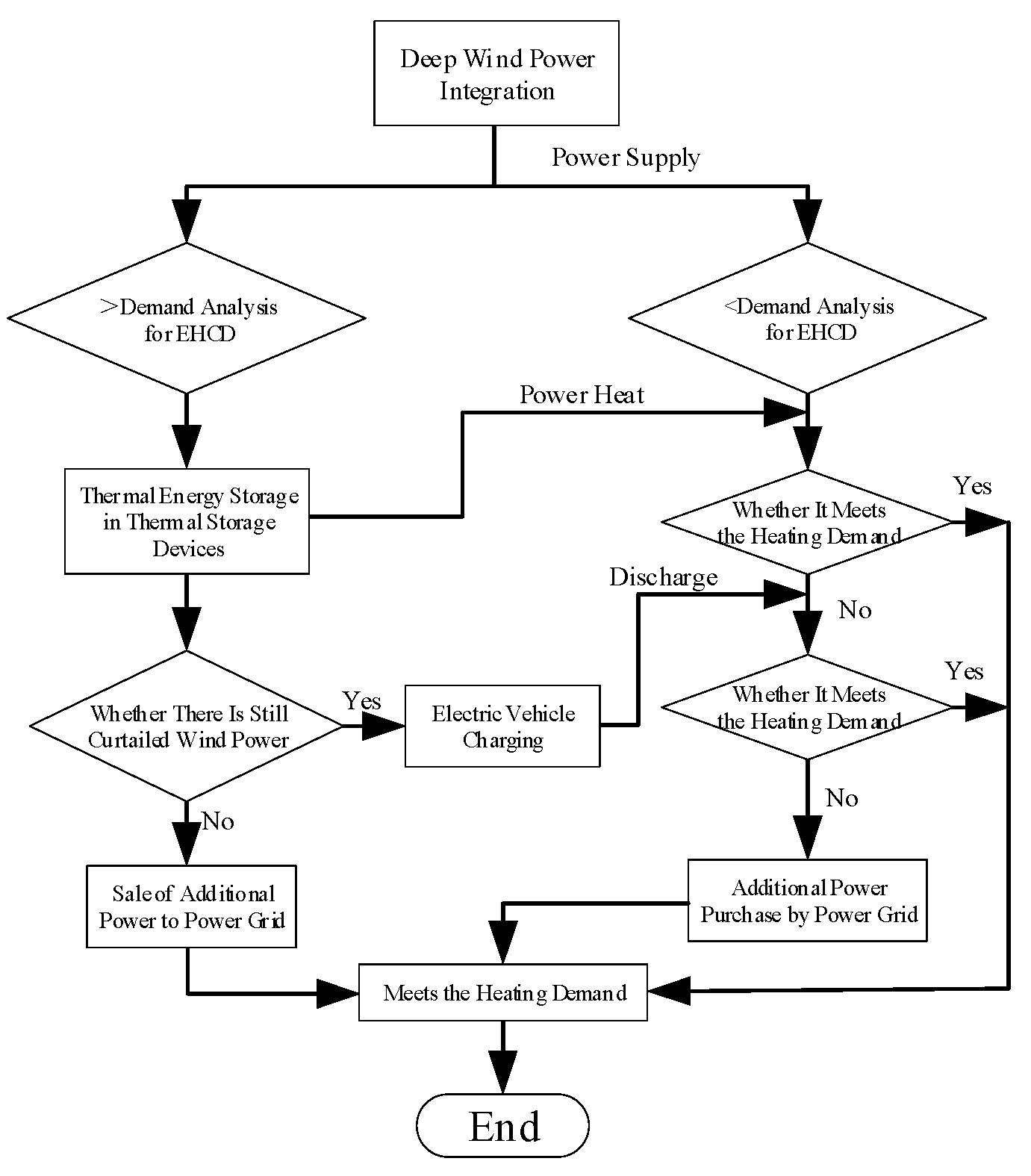

- It proposes a joint optimization scheduling framework for electric vehicles (EVs) and thermal storage electro–olefin–hydrogen electromagnetic energy supply devices (EHEDs). Through the flexible charging/discharging of EVs and the collaborative operation of thermal storage/discharging of EHEDs, a hierarchical control strategy is designed to break through the limitation of single-device wind–solar integration.

- (2)

- Develops a mixed-integer programming optimization framework adapted to the joint optimization scheduling framework, establishes the relationship between 0 and 1 variables and constraints such as coupled power balance and device operation boundaries, and realizes the collaborative optimization of wind–solar integration and economic operation through CPLEX solution, verifying the engineering practicability of the multi-energy complementary system.

- (3)

- Based on the differentiated charging needs of vehicle owners, EVs are divided into three categories: “time-sensitive”, “price-sensitive”, and “revenue-seeking”. The potential of “price-sensitive” and “revenue-seeking” dispatchable EVs is focused on, and a dynamic electricity price incentive and battery loss cost compensation mechanism are proposed, significantly improving user participation willingness and deep wind–solar integration.

2. Feasibility Analysis of Electric Vehicles—Thermal Storage Electric–Olefin–Hydrogen Electromagnetic Power Supply Equipment

2.1. Classification and Model of Electric Vehicle Scheduling Potential

- (1)

- Time-sensitive: EV owners aim to achieve the desired charging power in the shortest time.

- (2)

- Price-sensitive: EV owners expect to obtain power at the optimal price during grid-connected charging periods, ensuring the desired charging power before departure while avoiding battery degradation caused by “reverse charging”.

- (3)

- Revenue-seeking: EV owners aim to obtain power at the optimal price during grid-connected charging periods, while leveraging the “reverse charging” function to gain profits, ensuring the desired charging power before departure.

Classification and Model of Electric Vehicle Scheduling Potential

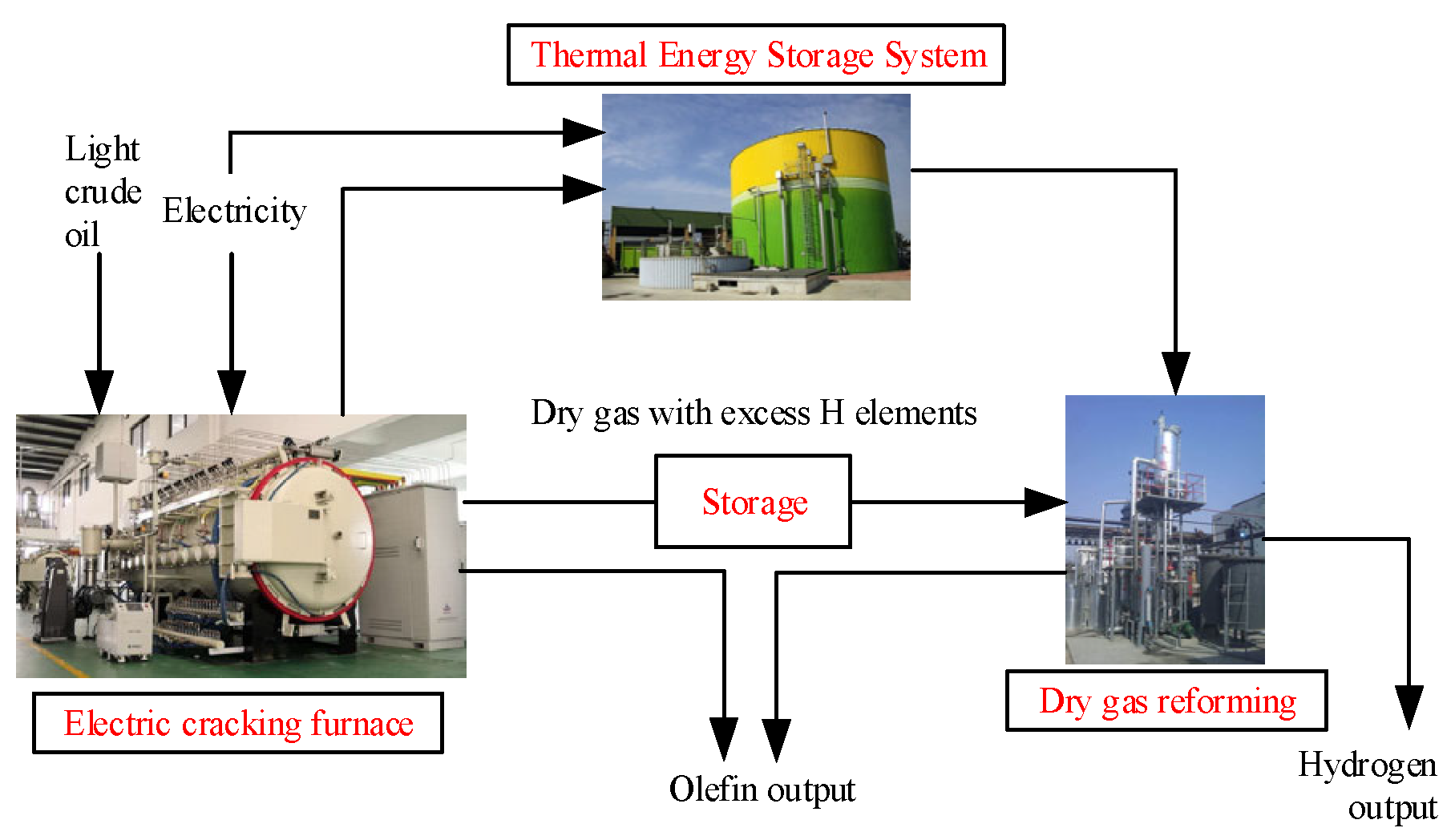

2.2. Energy Balance and Revenue Model of EHCD Equipment

2.2.1. Energy Balance Equation of Electro–Olefin–Hydrogen Device Cracking

2.2.2. Thermal Storage Capacity and Heat Release Power

2.2.3. Product Yield Model

2.2.4. Dry Gas and Hydrogen Sales Revenue Model

3. Wind–Solar Collaborative Clustering Method Based on Improved K-Means++

3.1. Data Preprocessing

3.2. Feature Extraction

3.3. Dimensionality Reduction

3.4. Improved K-Means++ Algorithm

4. Joint Optimization Scheduling of Electric Vehicles-Thermal Energy Storage Electro–Olefin–Hydrogen Device for Enhancing Deep Wind–Solar Integration

4.1. Objective Function

4.1.1. Depreciation Cost of TES-EHED

4.1.2. Battery Degradation Cost

4.1.3. Wind Turbine Generation Cost

4.1.4. Photovoltaic Generation Cost

4.1.5. Joint Scheduling Cost

4.1.6. Cost of Additional Grid Power Purchase

4.1.7. Dry Gas and Hydrogen Sales Revenue

4.2. Constraint Conditions

4.2.1. Power Balance Constraints

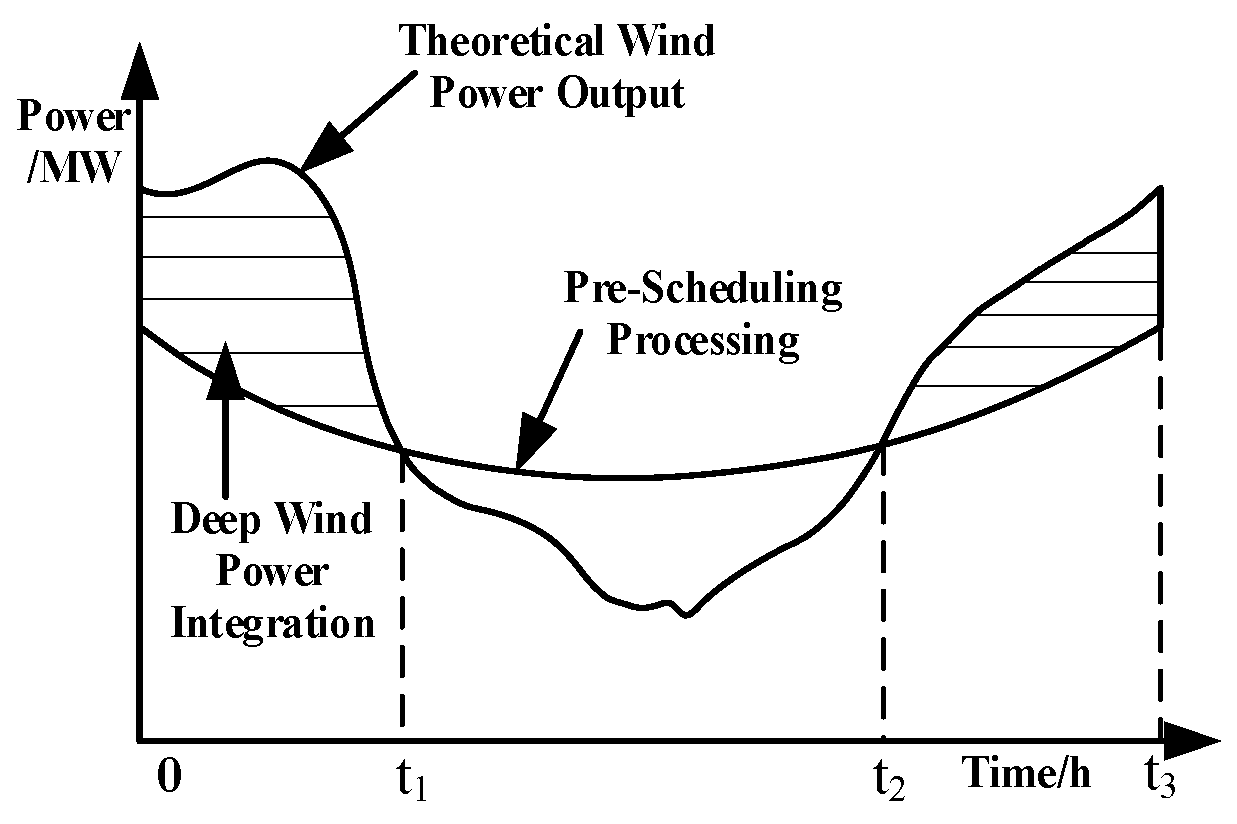

4.2.2. Deep Wind–Solar Integration Power Constraint

4.2.3. Operation Constraints of TES-EHED

4.3. Solution to Joint Optimization Model Based on Mixed-Integer Programming

5. Case Study

5.1. Case Description

5.2. Simulation Analysis

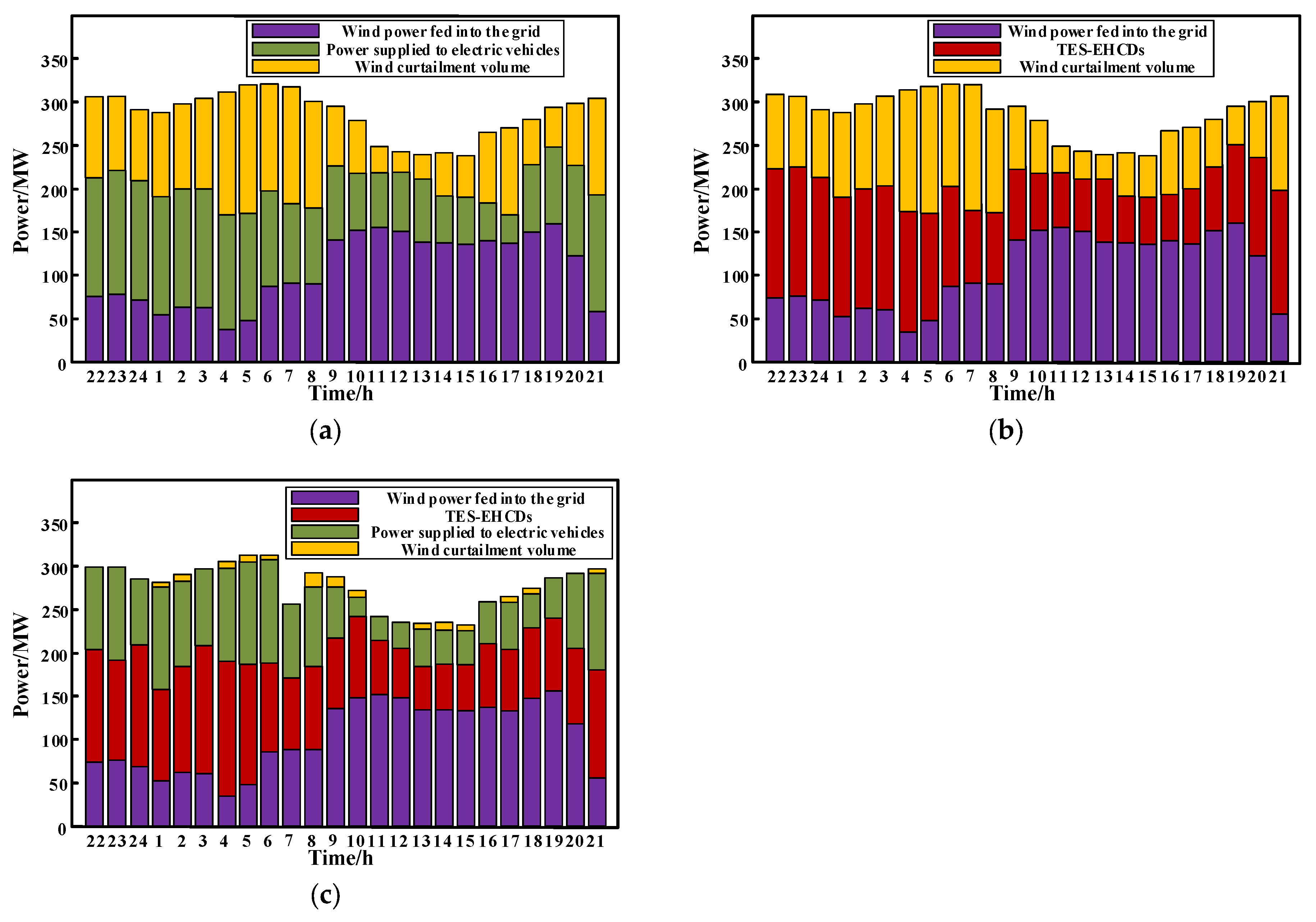

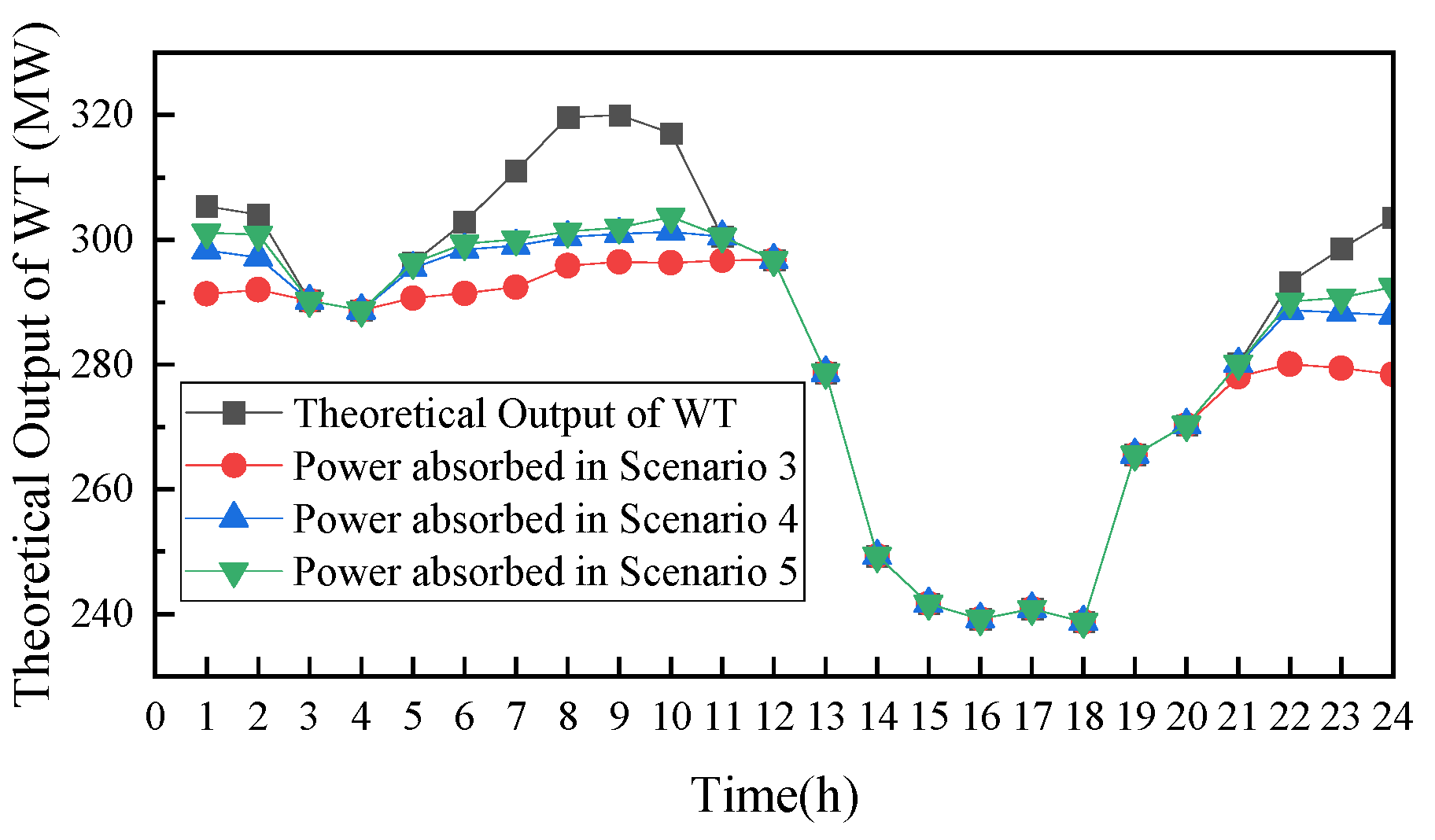

5.2.1. Deep Wind–Solar Integration Analysis

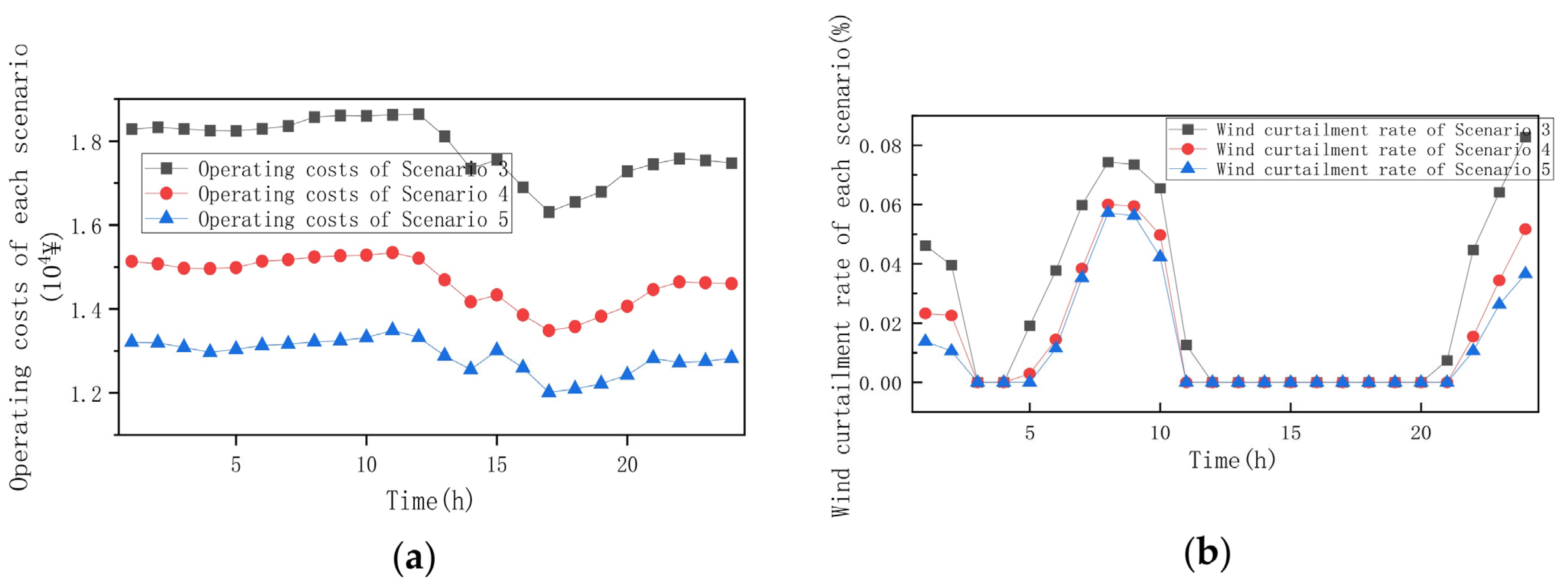

5.2.2. Comparison of System Operation Cost, EV Revenue, and Wind Curtailment Rate Under Three Scenarios

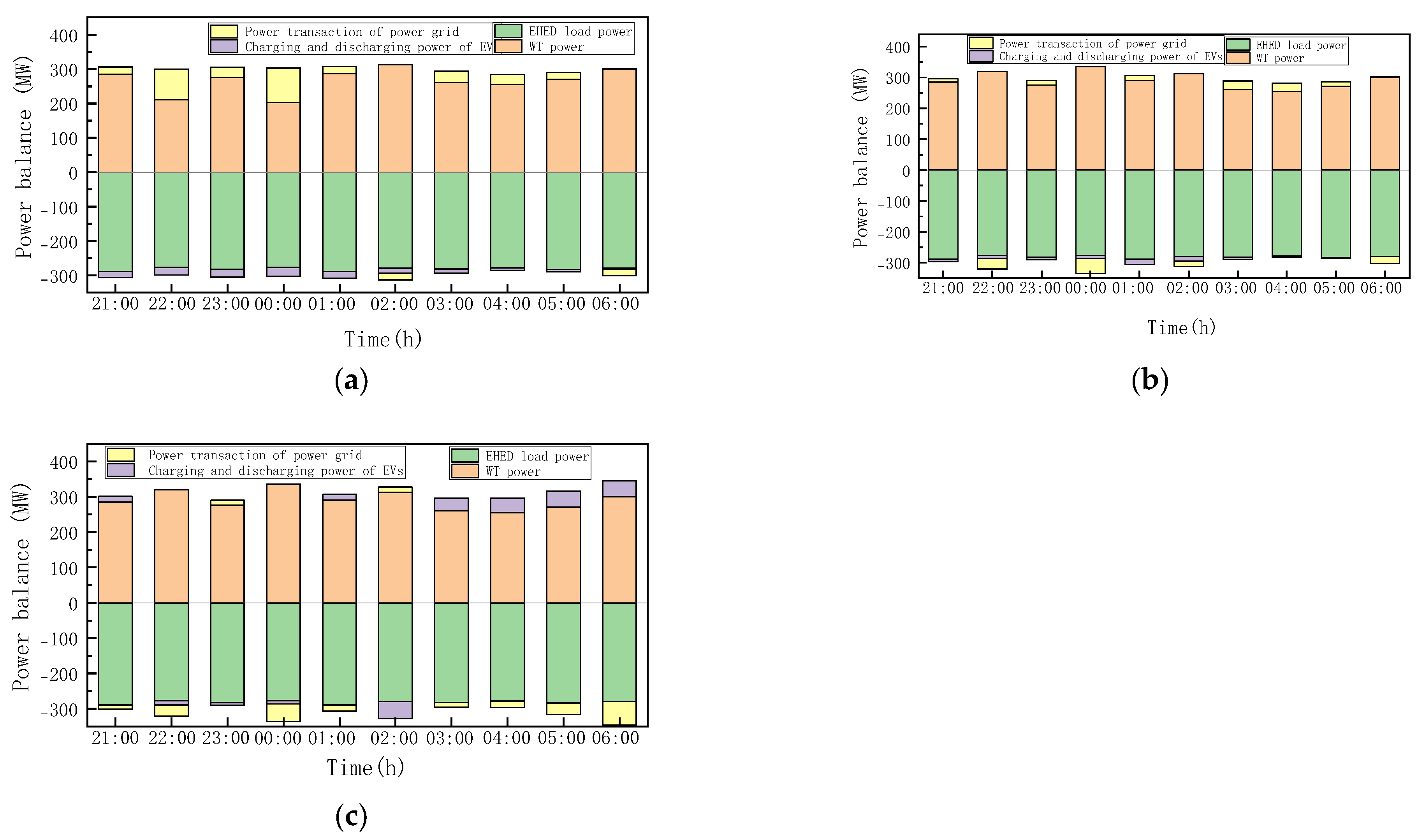

5.2.3. Joint Dispatch Optimization Under Different EV Demand Response Intentions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Callaway, D.S. Tapping the energy storage potential in electric loads to deliver load following and regulation, with application to wind energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baohong, J. Impact of renewable energy penetration in power systems on the optimization and operation of regional distributed energy systems. Energy 2023, 273, 127201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.; Iqbal, S. Reinforcement Learning-Based Optimization for Electric Vehicle Dispatch in Renewable Energy Integrated Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 20–24 October 2024; pp. 1297–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Bojod, J.; Erkal, B. Distributed Energy Resources for Techno-Economic with Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) based Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Energy, Electrical and Power Engineering (CEEPE), Yangzhou, China, 26–28 April 2024; pp. 1443–1448. [Google Scholar]

- National Energy Administration. Notice on Issuing the Clean Heating Plan for Winter in Northern Regions (2017–2021) [EB/OL]. 27 December 2017. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/201712/t20171220_962623.html?code=%26state=123 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Ding, T.; Mu, C.; He, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, R.; He, F.; Ren, C. Analysis on Current Situation of Clean Heating Policies and Typical Cases in Northwest China (II): Typical Cases and Economic Analysis. Proc. CSEE 2020, 40, 5126–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojod, J.; Erkal, B. A New Approach in Distributed Energy Resources for Techno-Economic with Metaheuristic Method and Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Integrated Circuits and Communication Systems (ICICACS), Raichur, India, 24–25 February 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Xin, H.; Wang, T.; Yang, J.; Peng, D.; Tan, Z. Robust Optimization Model for Joint Heating Dispatch of Wind Power and Thermal Storage Electric Boiler. Electr. Power Constr. 2016, 37, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Liu, Y.; Ni, Z.; Ge, L.; Li, X. Collaborative Operation Between Power Network and Hydrogen Fueling Stations with Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 1521–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Tang, J.; Ghosh, P. Optimizing Electric Vehicle Charging: A Customer’s Perspective. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2013, 62, 2919–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.; Singh, M. Dynamic scheduling of electricity demand for decentralized EV charging systems. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 39, 101467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Ganguly, S. Multi-objective smart charging scheduling scheme for EV integration and energy loss minimization in active distribution networks using mixed integer programming. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 43, 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yin, W.; Wen, T. An advanced multi-objective collaborative scheduling strategy for large scale EV charging and discharging connected to the predictable wind power grid. Energy 2024, 287, 129495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Bian, J.; Li, G.; Meng, X. A Two-Layer Real-Time Dispatch Strategy for Large-Scale Electric Vehicles Connected to Power Grid Based on Improved Rolling Horizon Method. Power Syst. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-G.; Choi, Y.-J.; Park, J.-K.; Bahk, S. Stackelberg-game-based demand response for at-home electric vehicle charging. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2016, 65, 4172–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, S.M.; Hasankhani, A.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Stochastic planning of a multi-microgrid considering integration of renewable energy resources and real-time electricity market. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirioun, M.H.; Jafarpour, S.; Abdali, A.; Guerrero, J.M.; Khan, B. Resilience-Oriented Scheduling of Shared Autonomous Electric Vehicles: A Cooperation Framework for Electrical Distribution Networks and Transportation Sector. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 7291712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Zhang, T.; Li, G.; Cheng, W.; Wang, J. Cloud-Edge Collaborative Scheduling Method for Virtual Power Plant Considering Parameter Consistency of Electric Vehicles. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2025, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Mehmood, K.K.; Bukhari, S.B.A.; Imran, K.; Wadood, A.; Rhee, S.B.; Park, S. An Optimization-Based Reliability Enhancement Scheme for Active Distribution Systems Utilizing Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 157247–157258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasciuolo, F.; Orozco, C.; Dicorato, M.; Borghetti, A.; Forte, G. Chance-Constrained Calculation of the Reserve Service Provided by EV Charging Station Clusters in Energy Communities. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 4700–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalala, Z.; Al-Omari, M.; Al-Addous, M.; Bdour, M.; Al-Khasawneh, Y.; Alkasrawi, M. Increased renewable energy penetration in national electrical grids constraints and solutions. Energy 2022, 246, 123361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, S.G.; Oladigbolu, J.; Li, L. A review on electric vehicle charging station operation considering market dynamics and grid interaction. Appl. Energy 2025, 392, 126058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediwaththe, C.P.; Smith, D.B. Game-theoretic electric vehicle charging management resilient to non-ideal user behavior. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 3486–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaimeh, M.; Wardle, R.; Jenkins, A.M.; Yi, J.; Hill, G.; Lyons, P.F.; Hübner, Y.; Blythe, P.T.; Taylor, P.C. A probabilistic approach to combining smart meter and electric vehicle charging data to investigate distribution network impacts. Appl. Energy 2015, 157, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Yu, J.L. Optimal sizing of the CAES system in a power system with high wind power penetration. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2012, 37, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yuan, M.; Jiao, X. Electric vehicle charging and discharging scheduling strategy based on dynamic electricity price. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yang, Q.; Yan, W. Optimal temporal-spatial electric vehicle charging demand scheduling considering transportation-power grid couplings. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting, PESGM, Portland, OR, USA, 5–10 August 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.; Lu, H.; Hong, Y.; Liu, S.; Chang, J. Dynamic pricing for electric vehicle extreme fast charging. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Yao, F.; Littler, T.; Zhang, H. An electric vehicle dispatch module for demand-side energy participation. Appl. Energy 2016, 177, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yu, C.; Chen, C.; Guo, L.; Su, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, X. Impedance model-based stability analysis of single-stage grid-connected inverters considering PV panel characteristics and DC-side voltage. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2025, 10, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Du, L. Optimal dispatching of electric vehicles for providing charging on-demand service leveraging charging-on-the-move technology. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 146, 103968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | EHED Load (MW) | Time | EHED Load (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 906.55 | 10 | 931.68 |

| 23 | 915.21 | 11 | 902.05 |

| 24 | 958.89 | 12 | 911.30 |

| 1 | 957.37 | 13 | 862.78 |

| 2 | 963.83 | 14 | 851.33 |

| 3 | 969.89 | 15 | 858.91 |

| 4 | 957.33 | 16 | 842.03 |

| 5 | 946.16 | 17 | 857.08 |

| 6 | 944.53 | 18 | 857.62 |

| 7 | 942.45 | 19 | 860.39 |

| 8 | 937.17 | 20 | 894.17 |

| 9 | 941.36 | 21 | 925.83 |

| Scenario | Operation Cost (104 Yuan) | EV Cost (104 Yuan) | Wind Curtailment Power (MW) | Curtailment Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | 101.03 | 4.46 | 223.2 | 3.26 |

| Scenario 2 | 97.16 | / | 215.64 | 3.15 |

| Scenario 3 | 42.80 | 2.34 | 193.2 | 1.37 |

| Scenario | Operation Cost (104 Yuan) | EV Revenue (104 Yuan) | EV Reverse Charging Revenue (104 Yuan) | Power Purchase Cost (104 Yuan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 3 | 42.8 | −2.341 | / | 16.93 |

| Scenario 4 | 35.21 | −0.727 | / | 9.72 |

| Scenario 5 | 30.93 | 3.219 | 3.809 | 5.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, S.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Lu, X.; Sun, L.; Zhou, G.; Wang, N. Joint Optimization Scheduling of Electric Vehicles and Electro–Olefin–Hydrogen Electromagnetic Energy Supply Device for Wind–Solar Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 5911. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225911

Sun S, Wang C, Cheng Y, Wang S, Wang C, Lu X, Sun L, Zhou G, Wang N. Joint Optimization Scheduling of Electric Vehicles and Electro–Olefin–Hydrogen Electromagnetic Energy Supply Device for Wind–Solar Integration. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5911. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225911

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Shumin, Chenglong Wang, Yan Cheng, Shibo Wang, Chengfu Wang, Xianwen Lu, Liqun Sun, Guangqi Zhou, and Nan Wang. 2025. "Joint Optimization Scheduling of Electric Vehicles and Electro–Olefin–Hydrogen Electromagnetic Energy Supply Device for Wind–Solar Integration" Energies 18, no. 22: 5911. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225911

APA StyleSun, S., Wang, C., Cheng, Y., Wang, S., Wang, C., Lu, X., Sun, L., Zhou, G., & Wang, N. (2025). Joint Optimization Scheduling of Electric Vehicles and Electro–Olefin–Hydrogen Electromagnetic Energy Supply Device for Wind–Solar Integration. Energies, 18(22), 5911. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225911