1. Introduction

In the context of the increasing demand for electricity, distributed energy resources (DERs) can effectively enhance the existing centralized energy network, offering greener energy and greater flexibility and reliability. The virtual power plant (VPP) presents a highly efficient and popular solution for seamlessly integrating distributed energy resources into the distribution network [

1,

2].

EVs provide flexible, mobile energy storage solutions [

3,

4,

5], and their widespread adoption is increasingly recognized as a crucial element of the energy transition. As sales of EVs flourish, operations are facing the challenge of an ever-increasing number of EVs integrated into the VPP. The intermittent nature of renewable generation and the uncontrolled charging/discharging of EVs can threaten the security and reliability of power system operations. The optimal operation of VPPs with EVs is a complex problem due to the inherent intermittency of DERs and the stochastic nature of EV charging and discharging behaviors. Modelling a realistic number of EVs interacting with VPPs incurs a significant computational burden for traditional optimization methods, for instance, mixed integer programming [

6,

7] and dynamic programming [

8]. With increasing EV participation, the number of decision variables expands, resulting in an exponential rise in computational costs.

Voluminous historical studies have focused on VPP scheduling and operation [

9] while excluding EVs from the modeling entirely or treating them merely as standard loads [

9,

10] without considering bidirectional interaction between VPPs and EVs. Ref. [

11] introduces a new VPP that integrates an EV fleet to mitigate the variability of wind power output. In [

12], the energy-saving potential of a VPP comprising PV and energy storage systems (ESS) is examined using historical data. Ref. [

3] utilizes EVs as a storage medium to overcome the variability of wind generation. Ref. [

4] proposes a two-stage robust optimization model for a VPP that aggregates EV energy storage; it analyzes the distribution characteristics of EVs over time, along with the responsiveness of EV users, to create a model for energy storage capacity. The deployment of VPPs with EVs to enhance renewable energy integration and manage EV charging and discharging efficiently is focused on in [

13]. Ref. [

14] researches the technical challenges associated with integrating EVs and renewable energy sources into the electric power system.

Ref. [

15] has explored pricing strategies for VPP operators that benefits both the operators and EV users. The proposed model involves a Stackelberg game where the VPP acts as a power sales operator, guiding EV users to charge orderly by setting an appropriate power sales price. Ref. [

16] optimizes the scheduling and operation of a VPP comprising charging stations for EVs, stationary batteries, and renewable energy sources. The potential of using bidirectional chargers to turn EV battery packs into a VPP that supports the power grid is explored in [

17]. Ref. [

18] discusses the impact of uncoordinated EV charging behavior on the power grid and the potential for coordinated operation to provide grid flexibility through VPPs. Ref. [

15] offers valuable insights for VPPs to efficiently manage EV charging behavior and enhance their operating revenue. The need for detailed charging models of EVs is highlighted in [

10], and their impact on VPP operations is explored by considering four different types of EVs. Ref. [

19] presents a method to enhance the reliability of a multi-type load power supply, reduce disorder in EV charging, and ensure the low-carbon economic operation of a VPP. Ref. [

5] discusses the potential for EV charging to function as a VPP to support distribution system operators.

VPPs are crucial for coordinating EV participation in the power market as aggregators of renewable energies and diverse loads. Ref. [

20] proposes a vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) market mechanism as a supplement to vehicle-to-grid (V2G) operations, aiming to maximize the revenue of each EV owner and create a distributed electricity market. The V2V market allows for trade among EV owners within a local distribution grid, leveraging charging points such as charging stations and auto parks. Ref. [

21] introduces an agent-based control system for coordinating the charging of EVs in distribution networks. Its objective is to charge EVs during low electricity price periods while adhering to technical constraints. Ref. [

22] considers multiple EV parking lots that are controlled by the VPP and its competitors, vying to attract EVs through competitive offering strategies. In [

23], the power optimization of PQ and PV nodes in the power grid was addressed using the SARSA method based on the convergence of power flow calculations. Ref. [

24] uses SARSA methods to address Q-learning’s overestimation issue in the automatic generation control strategy for interconnected power grids. Ref. [

18] introduces discomfort function for scheduling EV charging that accounts for EV drivers’ reluctance to change their initial charging patterns.

V2G [

25] technology allows not only for the charging of the EVs but also for the discharge of energy back into the grid. Through V2G services, EV groups can play a dual-role as both energy consumer and provider. To tap into the battery capacity of EVs in a parking lot, Ref. [

26] proposes V2G services and a dynamic charging price to optimally control the charging and discharging of EVs in a parking lot. Ref. [

27] designs an energy management system to optimize the energy distribution between a workplace’s PV system, grid, and battery electric vehicles (BEVs), leading to reductions in charging costs and decreased grid energy consumption.

There is increasing research on V2G services in the context of VPPs, but the research on the integration of V2G services provided by a large quantity of EVs into VPPs is still not sufficiently explored. Although the price signal from the VPP to the EV group is well-understood and has been extensively studied [

21,

26], the potential for V2G services offered by the EV group to the VPP remains under-explored in existing research. Refs. [

20,

26,

27] did not discuss what impact the arrival of a significant number of EVs at a charging parking lot would have on the aggregator, and how to optimize and mitigate these impacts without compromising the interests of the power provider.

Although various studies [

6,

18,

25,

26,

28,

29,

30,

31] have explored VPP–EV coordination using different optimization approaches, scalability remains a major challenge. As the number of EVs increases, ensuring computational efficiency and solution quality becomes increasingly difficult. Game-theoretic [

32,

33] methods often perform well in small systems but face exponential growth in complexity with more agents, leading to convergence issues. Similarly, neural network-based reinforcement learning (RL) models can be slow to converge and yield suboptimal results compared to lighter, more interpretable tabular RL algorithms in small-scale settings [

34].

Compared to the existing literature, the core motivation for this research is addressing the challenges posed by the substantial quantity of EVs integrated into VPP operations. To overcome the challenges, special considerations are required to ensure optimal solutions are obtained within reasonable time budget. Interactive optimization frameworks in the form of centralized control [

15,

16,

17,

18] structures demand substantial computational resources and time. Consequently, this study adopts a decentralized [

35,

36] approach to decouple the modeling of the VPP and EVs. Additionally, RL algorithms exhibit robustness in dynamic and uncertain environments, enabling adaptive decision-making when the EV model is trained iteratively using the Monte Carlo (MC) simulation. For VPP optimization, a gradient-based optimization algorithm combined with a custom loss function is novelly employed to leverage the high computational capacity of GPUs.

This paper presents a two-stage optimization framework for managing the operation of a VPP that integrates EVs, PVs, and a battery energy storage system (BESS). The VPP aims to maximize the revenue from both the EV group and the electricity wholesale market while offering reduced charging costs to the EV group to incentivize their participation in V2G discharge activities. To study the impact of a realistic number of EVs, a MC-SARSA is proposed to train an EV model on the electricity price provided by the VPP.

The contributions of this paper are threefold:

- (1).

A two-stage optimization framework for the coordinated operation of a VPP that integrates PVs, and a BESS, serving a substantial quantity of EVs that act as prosumers.

- (2).

A MC-SARSA algorithm is used to train the EV model based on the electricity price provided by the VPP, with training accelerated through action masking for RL.

- (3).

A gradient-base optimization algorithm with custom loss function to achieve optimal solution for VPP operation, also an exemplary pricing strategy is proposed for the analytic purposes of VPP profitability and EV cost reduction.

2. Problem Formulation

EVs parked at workplace charging facilities typically remain for extended durations, providing sufficient time to charge their batteries to the expected energy level before departure. However, the energy capacity stored in the EV batteries during this period after being fully charged is wasted. The capacity of EV batteries can be leveraged to increase the financial benefits for both the VPP and EV owners. EV owners will obtain a better charging electricity price by participating in the V2G scheme and offer the battery capacity to VPP as long as the battery is charged to the expected energy level at departure. The desired SOC level before departure is modeled as a variable set by the EV owner upon arrival. This design introduces flexibility into the EV model, enabling it to accommodate diverse driving scenarios and individual user preferences. For example, drivers with mileage anxiety may choose to set their desired SOC to the maximum limit. By specifying the target SOC, the model captures realistic behavioral variations among EV owners. This flexibility ensures that charging strategies are better aligned with individual needs and driving habits. At the aggregate level, the VPP can tap from this EV battery capacity at disposal through trading in the wholesale electricity market.

This research does not adopt a centralized control structure, as centralized control relies on physical communication infrastructure, requiring sufficient speed, stability, and bandwidth. Moreover, it places the entire computational and decision-making burden on a single node, creating a critical single point of failure that compromises the system’s robustness and scalability. In such a setup, decisions are made centrally without considering the specific preferences of individual participants, and the lack of personalized incentives may discourage user participation. Therefore, in this research, the VPP does not directly manage EV charging and discharging; rather, the EV model functions as a self-interested agent. The final product of the EV optimization is a self-governing agent that requires no additional tuning during runtime. This EV model is capable of directing the charging/discharging behavior of EVs as they enter the car park. Additionally, since the EV model can simulate a large number of EV charging and discharging behaviors, it can also be used for price strategy analysis.

2.1. Two-Stage Optimization Framework

MC simulation is a robust statistical technique employed to model and analyze the impact of risk and uncertainty in prediction and forecasting models [

37]. This method relies on the generation of a large number of random samples to investigate the potential outcomes of a process or system. The inputs to the simulation are typically characterized by probability distributions (normal, uniform…), which delineate the range and likelihood of various input values. The process entails conducting numerous iterations, with each simulation using different sets of random inputs to generate a distribution of possible outcomes.

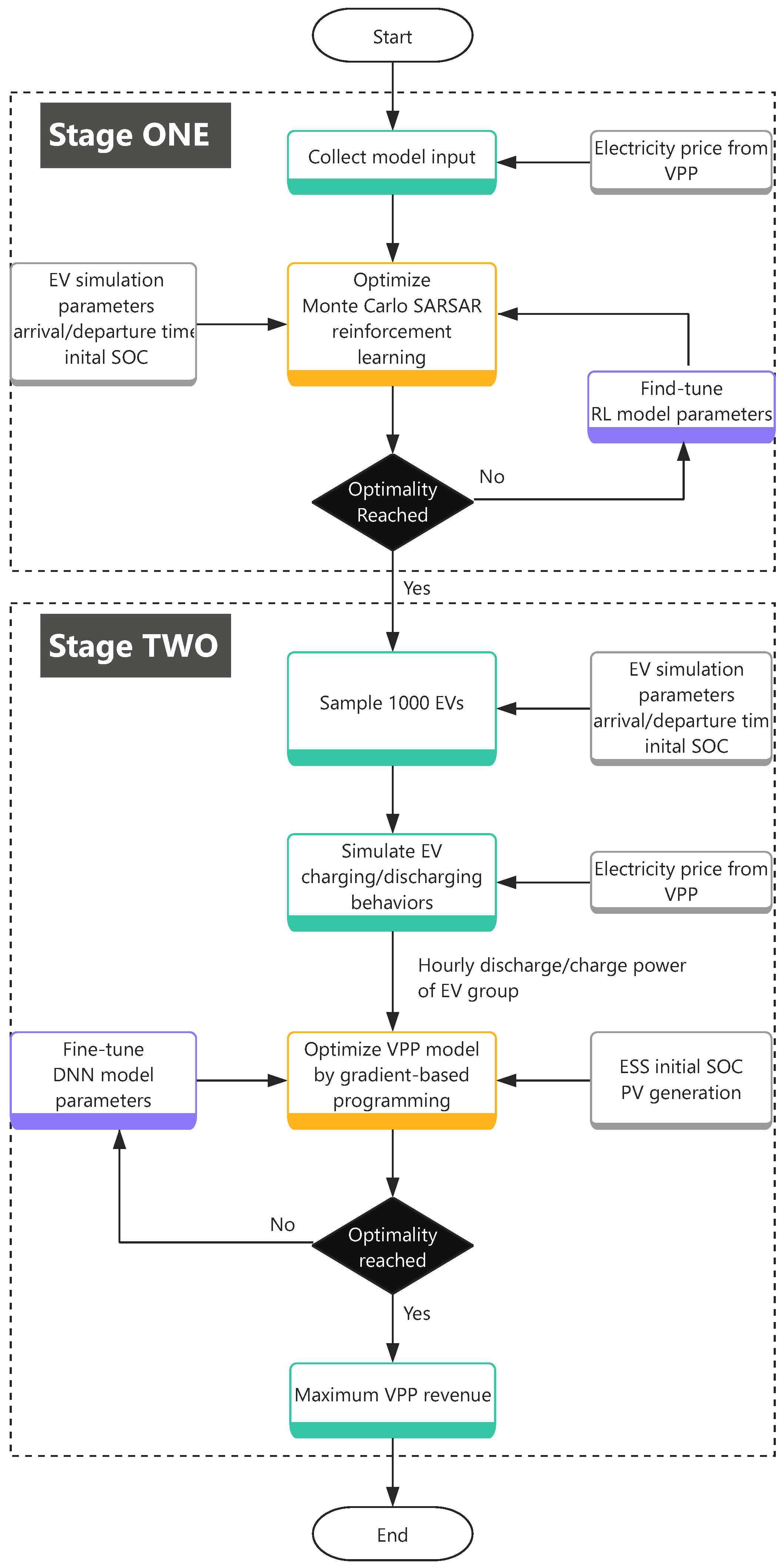

The two-stage optimization framework is a strategic approach utilized in decision-making processes, characterized by the sequential execution of decisions across two distinct stages. This framework proves particularly advantageous for addressing problems where uncertainty or variability plays a significant role.

2.1.1. First Stage: EV Model Training

In the first stage, the EV drive-in time, departure time, state of charge (SOC) at drive-in, and minimum charging hours are mathematically modeled using stochastic distribution. Based on this stochastic distribution, an MC simulation is employed to randomly generate an EV customer’s entry into the system, optimizing the EV model until achieving optimal convergence.

Direct optimization methods such as dynamic programming (DP) and mixed integer linear programming (MILP) are not considered in this study due to their inherent limitations. DP requires full knowledge of system dynamics and suffers from the curse of dimensionality [

34], making it computationally inefficient for large state or action spaces. This limitation is particularly relevant to our problem, which involves optimizing the behavior of a large number of EVs. While MILP is effective for problems with a moderate number of decision variables, it struggles with non-convex constraints and objectives, making it less suitable for complex, uncertain, or nonlinear scenarios involving interdependent EV participants.

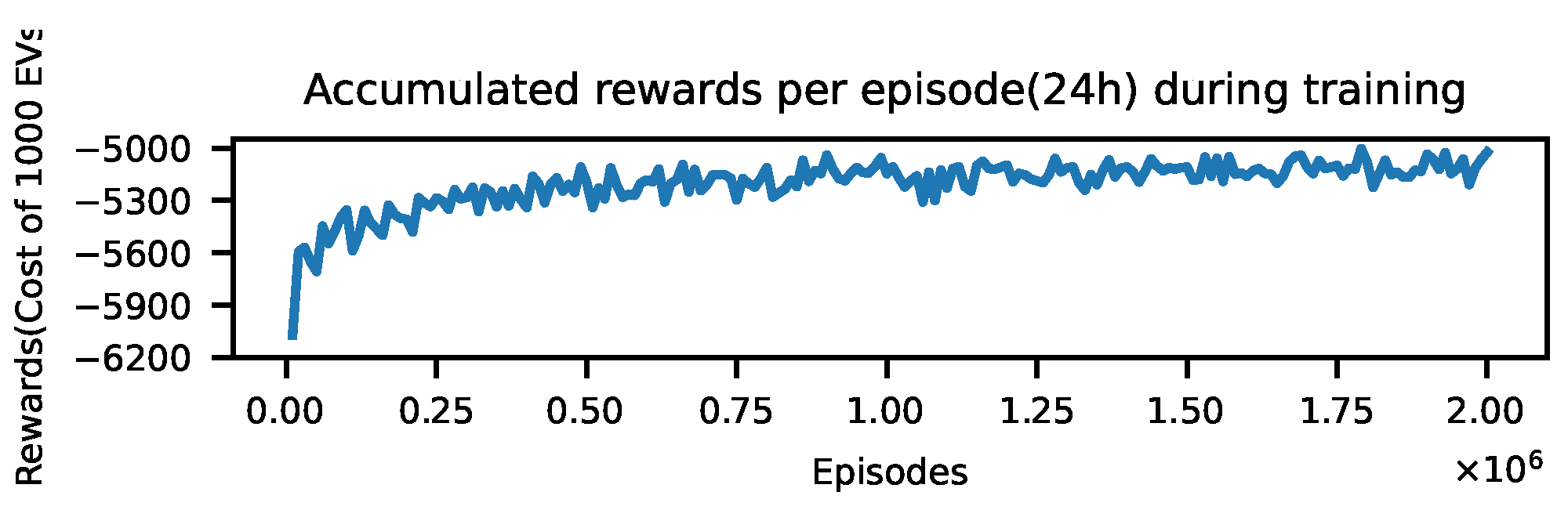

For EV modeling, Monte Carlo SARSA (MC-SARSA) was selected over deep RL methods due to its superior convergence stability, computational efficiency, and interpretability. In mathematical optimization, deep RL often encounters convergence instability, leading to suboptimal outcomes. In contrast, tabular MC-SARSA provides more reliable learning for EV charging scheduling. It also requires far less computational power while achieving comparable performance, making it suitable for edge deployment on EV terminals. Moreover, its tabular structure offers better interpretability of learned policies compared with the black-box nature of DNN.

The motivation for modeling EV behaviors using RL also lies in its efficiency and adaptability. Once trained, an RL model requires relatively low computational resources, making it well-suited for deployment in resource-constrained environments such as the charging terminals in our case. Accordingly, the operational behavior of the EV model is formulated using an MC-SARSA RL algorithm, enhanced with action masking to accelerate convergence.

Upon completion of the EV model training, 1000 EVs are randomly generated, preparing for the second stage, which involves VPP operational optimization. In this stage, the 1000 EVs act as contracted prosumers, and their operational behavior is guided by the optimal EV model trained in this stage.

2.1.2. Second Stage: VPP Operational Optimization

In the second stage, a BESS and a PV system are mathematically modeled, and the base electricity price of wholesale market is determined. PV generation is highly sensitive to the weather conditions of a given area. To develop a model that is robust to the stochastic nature of this renewable resource, traditional direct optimization methods, such as linear programming and dynamic programming, often struggle due to the issue of variable explosion when large volumes of PV data are considered.

In the context of VPP modeling, convergence time is less critical compared to EV modeling, which must accommodate a substantially large population of EVs. Neural networks, owing to their high representational capacity, are particularly well-suited for optimizing problems characterized by stochastic PV generation. Deep neural network (DNN)-powered gradient optimization offers distinct advantages, including inherent differentiability and GPU-accelerated parallelization, handling computationally intensive optimization. Consequently, the formulation of objective functions in VPP modeling can be extended to include general differentiable functions, thereby relaxing the constraints traditionally imposed by convexity [

38].

As a result, a DNN is designed for the gradient-based optimization of the VPP model. A custom loss function is designed as the objective function of the VPP modeling. As the DNN converges, the stabilized loss value converges to the optimal results of the VPP model.

Figure 1 illustrates the two-stage optimization framework for managing the operation of a VPP that integrates EVs, PVs, and a BESS.

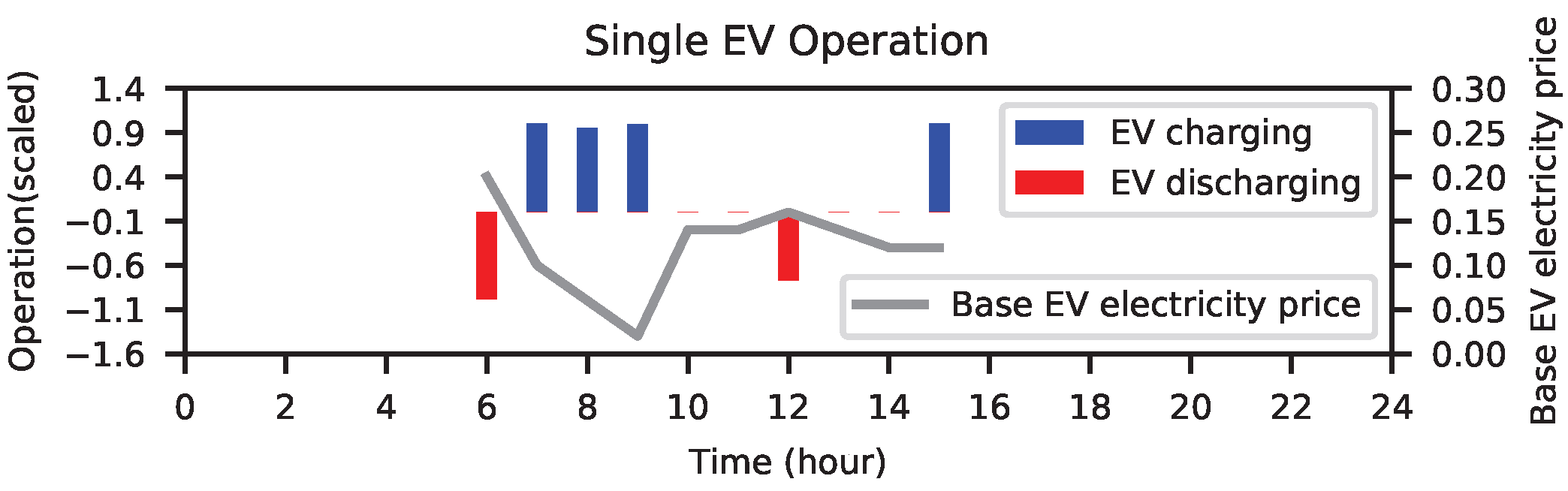

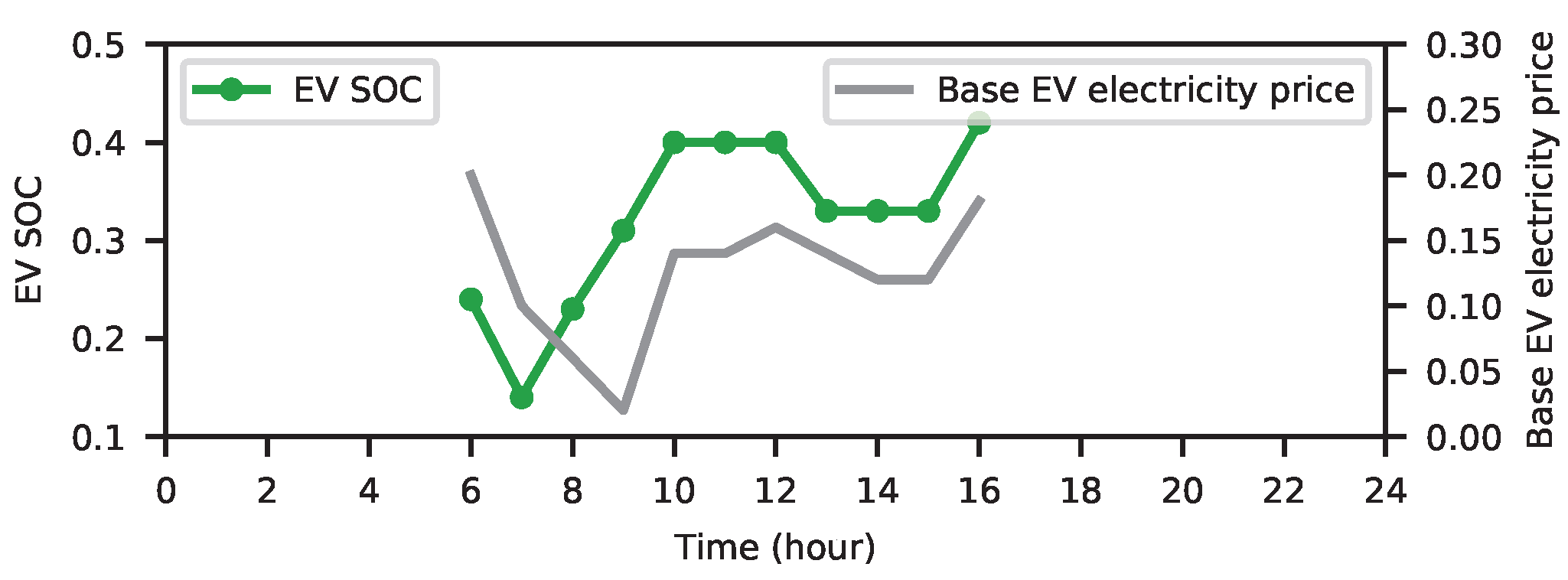

2.2. EV Model

EV enters the workplace car park in a stochastic manner, and leaves at around 5 pm in the afternoon. During the period of stay, the EV owner expects the vehicle to be charged to the required hours set upon entering. During the span of around 9 h, the vehicle is assumedly contracted to the VPP owner to offer the battery capacity to the VPP, and, in return, VPP allows the EV owner to charge the vehicle at a favorable hour and price. The EV will always charge during the hours with the lowest price and discharge during the hours with the highest price, based on the assumption that the EV acts as a rational agent prioritizing its own benefits. EV owners participating in V2G schemes benefit from reduced prices in exchange for granting the VPP the right to use their EV batteries during their parking periods. As this paper focuses on optimizing the benefits of the VPP, EV battery degradation is not directly modeled.

The objective of the first stage optimization is to minimize the cost of charging the EVs to the minimum charging requirements which are formulated as follows:

The total cost of charging the EV group is the sum of the individual charging costs for each EV, minus the V2G services revenue generated by each EV. is the revenue by selling electricity to the VPP through V2G service. is the charging cost incurred by purchasing electricity from the VPP.

Upon arrival, an

has an initial amount of energy stored in the battery, the SOC of the

is set to the initial SOC level,

. In this research, the initial SOC level of the

follows a normal distribution.

where

is the arrival time of the

EV,

is the initial drive-in SOC of the

EV.

The V2G revenue from the VPP to the EV group is the accumulating value of the V2G revenue at each time step

t for each

in the group:

where

N is the total number of EVs in the study,

T is the total number of time steps considered in the optimization period, and

is the duration of each time step.

is the discharged power from

EV to the VPP at the time

t,

is the V2G electricity price offered to EV group by the VPP at the time

t.

is the V2G service fee charged by the VPP to the EV owner participating in the scheme.

The cost of purchasing electricity from the VPP follows (

4). The total cost of charging the EV group is the sum of the costs of purchasing electricity at each time step

t for each

in the group:

where

is the charging power of the

EV from the VPP at the time

t,

is the charging electricity price offered to EV group by the VPP at the time

t.

Before arrival and after departure, the SOC of

is set to zero:

where

is the departure time of the

EV.

The SOC of the

at time

during the scheduling is calculated as follows:

where

is the SOC of the

EV at time

t,

is the charging efficiency of the

EV,

is the discharging efficiency of the

EV, and

is the battery capacity of the

EV.

Outside the parking period (from arrival to departure), the charging and discharging power of

should be zero:

During the MC simulation, the departure time for

should always be later than the arrival time at all times. Both the departure time and the arrival time should be a positive integer following a normal distribution, with a different mean value.

The charging and discharging power of the

at any time during the scheduling must not exceed the maximum and minimum charging/discharging power limits, as described by the following equation:

where

and

are the minimum and maximum discharging power of the

EV respectively; Likewise,

and

are the minimum and maximum charging power of the

EV.

To protect the battery life of the EV, the SOC of the

is constrained by the following conditions:

where

and

are the minimum and maximum SOC of the

EV, respectively.

The power exchange between the EV group and the VPP adheres to the following balance equation:

To prevent simultaneous charging and discharging within any operational time horizon, the power exchange between the

EV and the VPP is regulated by the following condition:

Upon departure, the SOC of the

EV should be charged to the required SOC level.

where

is the required energy that need to be charged to the

EV at departure in terms of SOC.

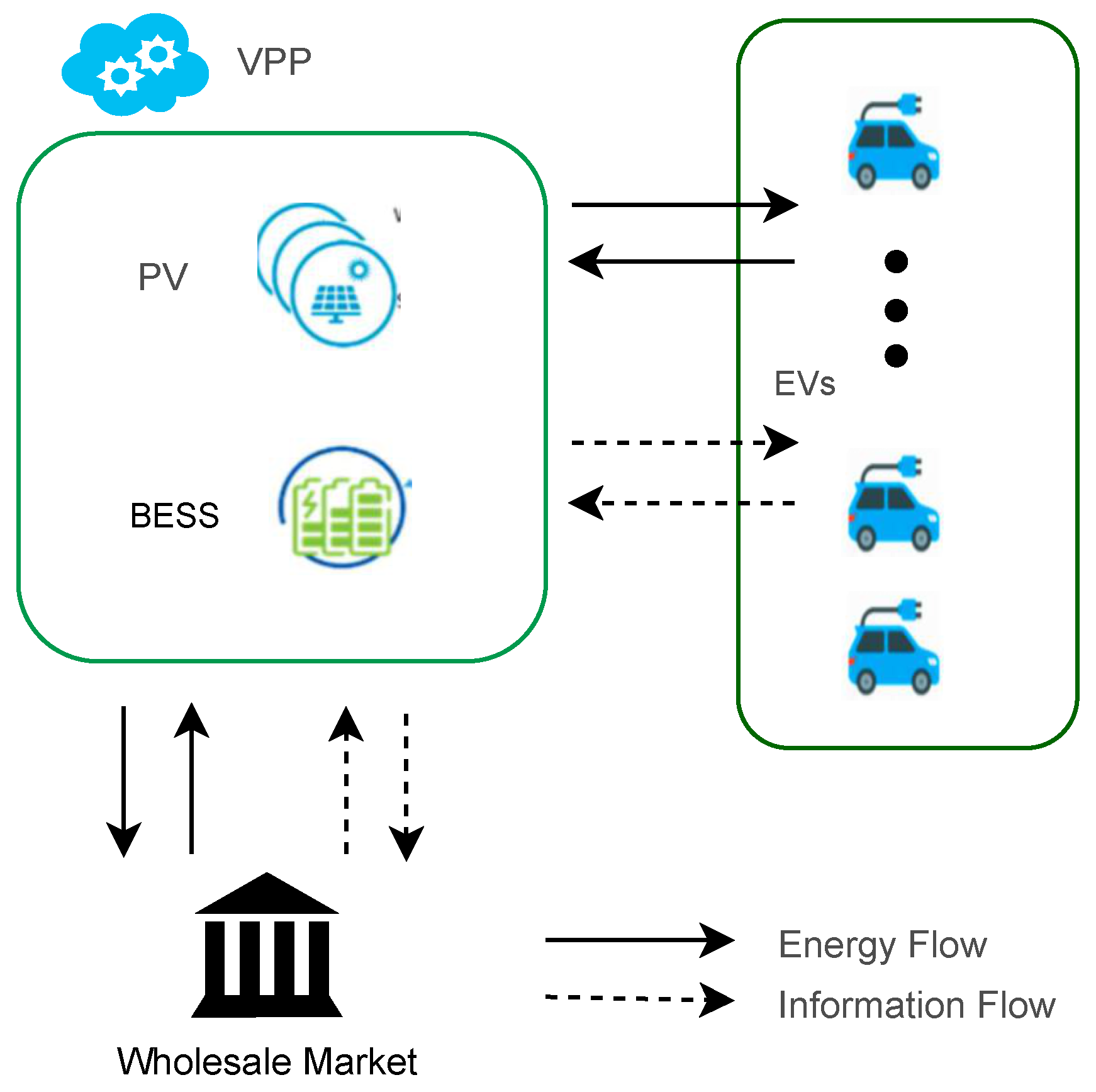

2.3. VPP Model

The VPP in this study owns a PV system, a BESS. Additionally, a group of EVs that randomly enter and leave the workplace parking lot during working hours are the contracted customers of the VPP. The purpose of the BESS is to smooth the intermittent PV power generation and store the surplus energy. PV energy generation involves converting sunlight into electricity using photovoltaic cells, which convert the light into direct current (DC), then transformed into alternating current (AC) for use in homes and businesses or for feeding into the electrical grid. The VPP generates revenue by selling electricity on the wholesale market and providing energy to meet the charging demands of the EV group as shown in

Figure 2. The scale of the VPP business is modeled to accommodate

N number of EVs entering daily, where

N represents any realistic figure that makes business sense to the VPP owner. Once the RL-based EV model is trained, it enables efficient scalability to 100–3000 EVs with minimal computational overhead, due to its decentralized decision-making policy. Although the experimental results in this paper focus on 1000 EVs, the model can scale to 5000 or more without notable computation time increase. The trained EV model is capable of analyzing business strategies for a VPP at a fine-grained scale, factoring in the number of EVs included in the modeling.

The objective of this VPP study, which is the second stage of the optimization framework, is to maximize the revenue of the VPP which is calculated as follows:

where

is the revenue gained by selling electricity to the wholesale market.

is the cost incurred by purchasing electricity from the wholesale market during energy deficiency.

The revenue of the VPP is the surplus from the revenue gained by selling electricity to the wholesale market and the cost incurred by purchasing electricity from the wholesale market during energy deficiency. Another stream of revenue comes from the energy transactions between EVs and the VPP. This includes the energy purchased by EVs for charging during the scheduled time period, offset by the energy sold back to the VPP through V2G services.

The VPP feed-in revenue is calculated by accumulating all the VPP feed-in revenue during each time step

t:

where

is the feed-in price at the time

t,

is the power fed into the grid by the VPP at time step

t.

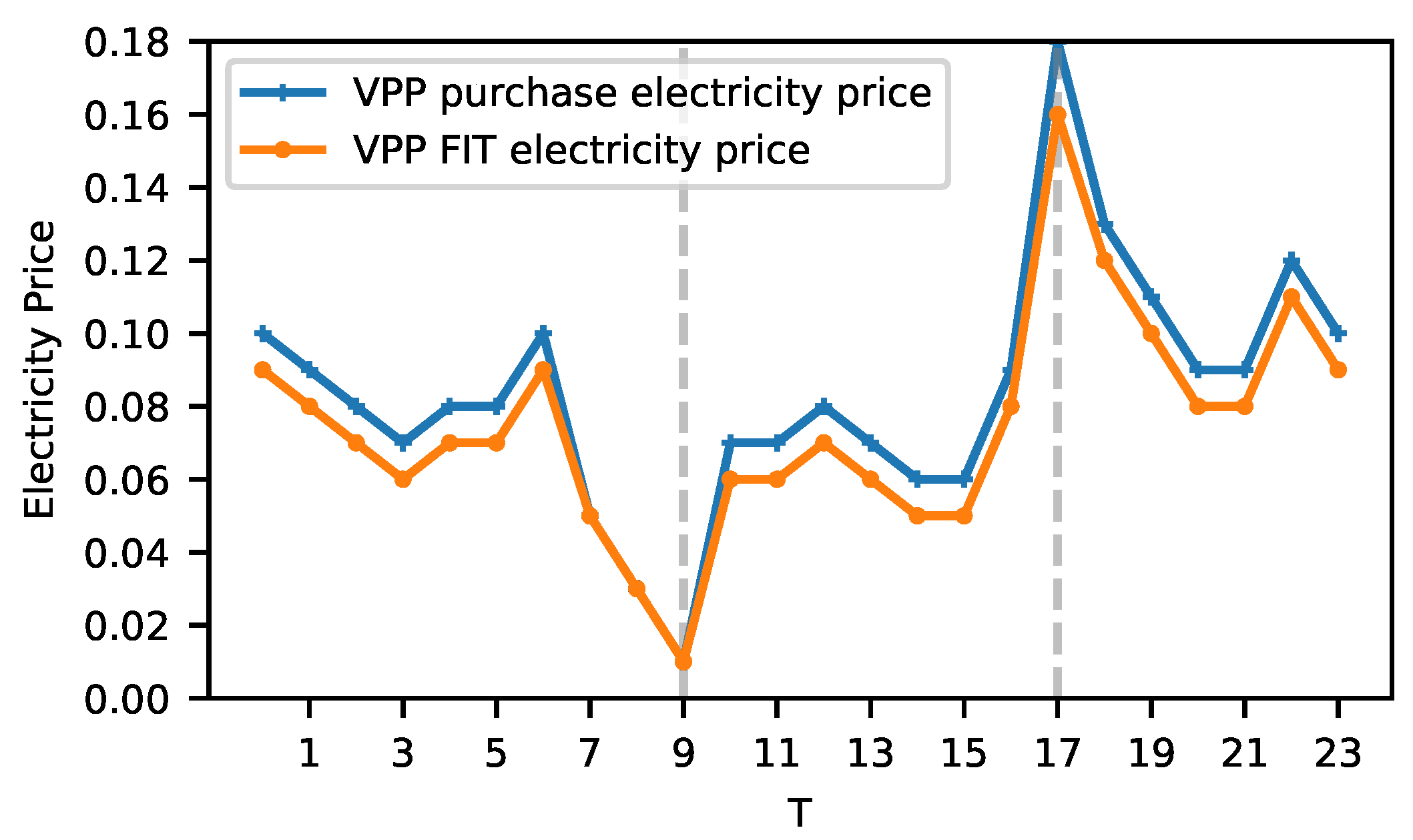

The cost of purchasing electricity from the wholesale market is calculated as follows:

is the cost incurred from purchasing electricity from the wholesale market. is the wholesale market electricity price at the time t. is the required power from the grid for VPP at time step t.

The feed-in electricity price sold to the wholesale market at each time step

t is marked down from the purchase electricity price from the wholesale market by a discount factor

, where

.

2.3.1. PV Generation

For the purpose of mathematical modeling, the PV panels are aggregated into a single unit, calculated using the following formula [

26]:

where

is the PV power generation of the VPP,

is the global horizontal irradiance at time

t,

A is the area of the PV panels, and

is the efficiency of the PV panels.

2.3.2. Battery Storage

During the period of VPP scheduling, the discharging and charging of the ESS is constrained by the following condition:

where

is the SOC of the ESS at time

t,

is charging power of the ESS at time

t,

is the discharging power of the ESS at time

t,

is the charging efficiency of the ESS,

is the discharging efficiency of the ESS, and

is the battery capacity of the ESS.

The charging and discharging power of the ESS at any time during the scheduling can not exceed the maximum and minimum power limits, as described by the following constraints:

where

and

are the minimum and maximum charging power of the ESS, respectively; likewise,

and

are the minimum and maximum discharging power of the ESS, respectively.

The ESS cannot be charged and discharged simultaneously at any time during the scheduling period, and this is ensured by the following condition:

At the end of the scheduling, the SOC of the ESS should be the same as the initial SOC

.

For the safe operations of the ESS, the SOC of the ESS is constrained by (

25) at any time

t:

where

and

are the minimum and maximum SOC, respectively.

2.3.3. Power Equation

During the scheduling period, the VPP system is constrained by the following balance equation:

where

is defined in (

12).

when EVs are charging,

when EVs are discharging.

Power exchange between the VPP and the grid during the operational time horizon is governed by the following condition:

2.3.4. Modeling and Simulation

The VPP model is a three-layer neural network with a neuron configuration of 24-50-100-50-24, which converges stably to the optimality within 3 min and 47 s. The input vector is divided into two segments: the first segment consists of the hourly electricity prices, and the second segment includes 24 inputs representing the solar power generation for each hour. The model outputs 24 values, which correspond to the hourly discharge or charging schedule operations of the BESS.

The output decision vector of the neural network is constrained to the range

using the hyperbolic tangent activation function, where negative values indicate VPP battery discharging, positive values represent charging, and a value of zero signifies an idle state with no charging or discharging activity. Positive raw values from the neural network are scaled to the range

, while negative raw values are similarly scaled to

. As a result, constrait (

23) is upheld. Furthermore,

is cliped within the bounds

,

to ensure compliance with the predefined operational limits, if the output decision vector of the neural network results in a violation of the lower or upper bounds of

during training.

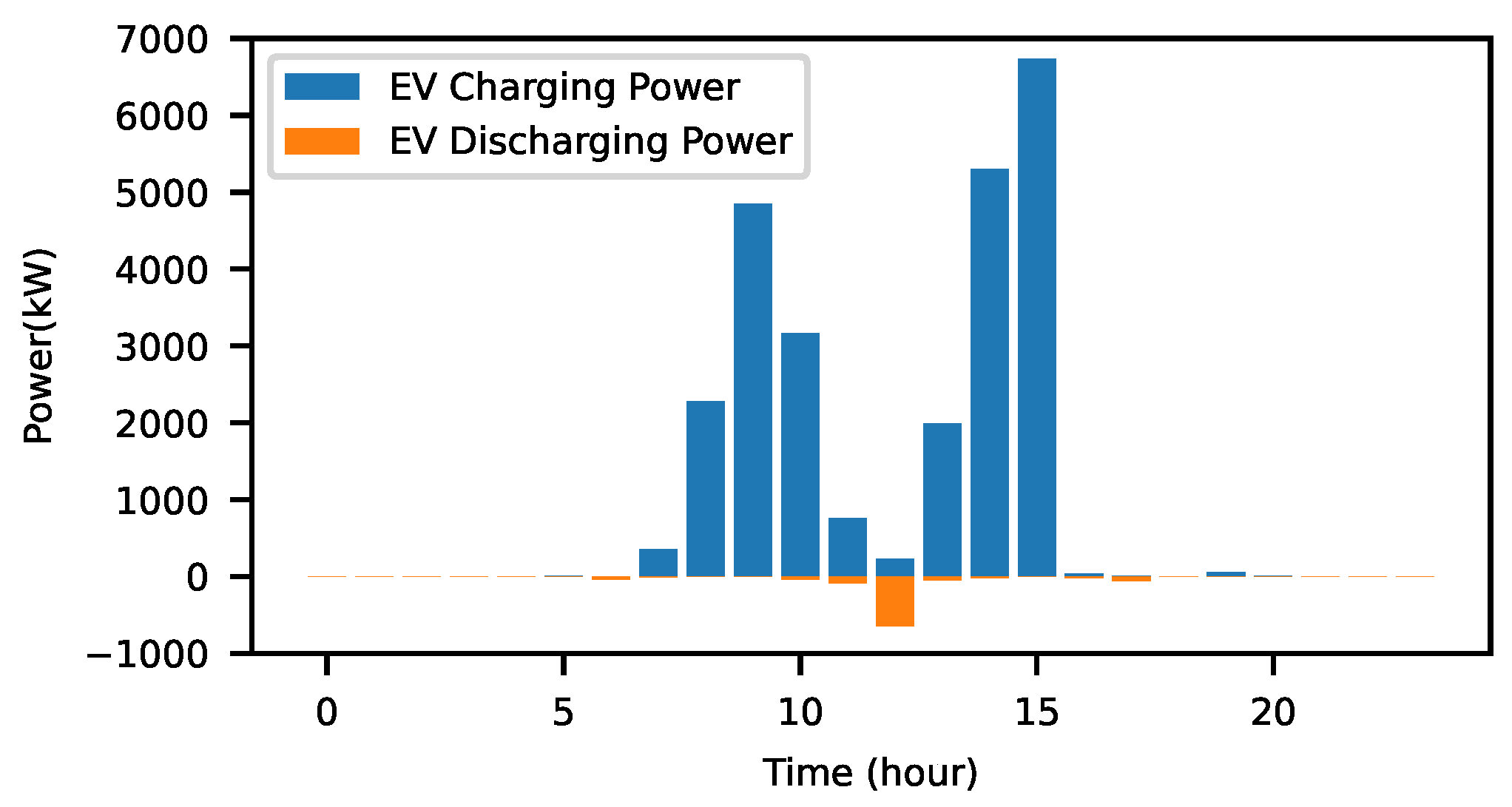

The MC sampling method is employed to simulate 1000 EVs driving at various times with diverse charge demands, computing the hourly power exchange between EVs and the VPP, leveraging the optimal EV model previously trained. On average, the MC-SARSA model with action masking converges within approximately 4 min 18 s. This convergence time reflects the model’s ability to efficiently explore and exploit the action space while maintaining stability in the learning process. Note that while the choice of 1000 vehicles reflects the scale of the VPP business and is not constrained by computational capabilities.

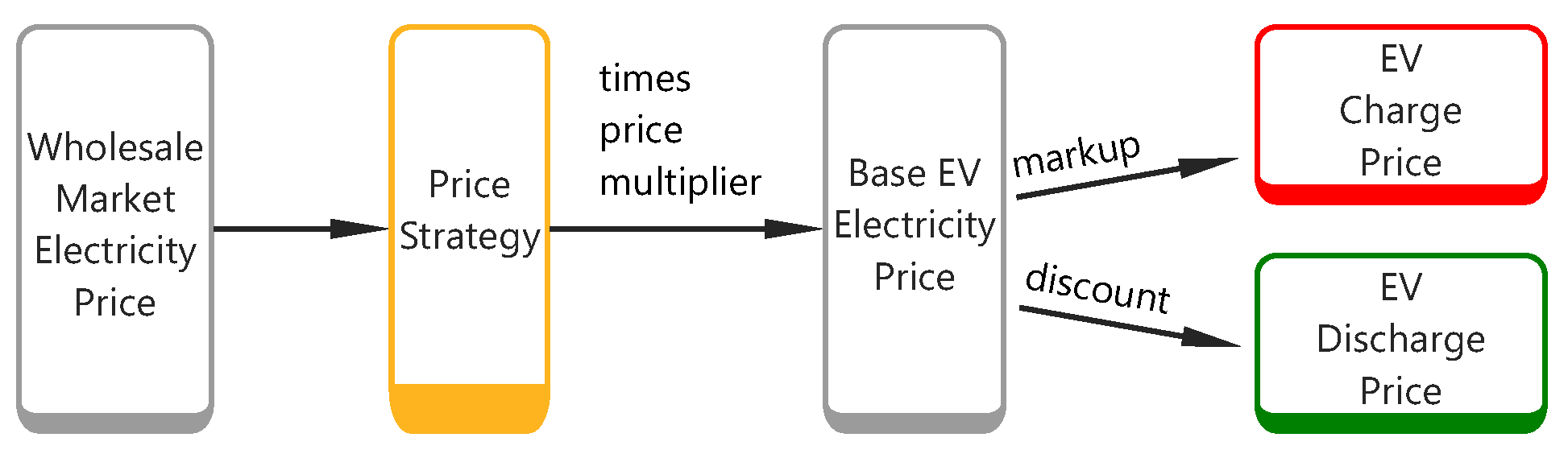

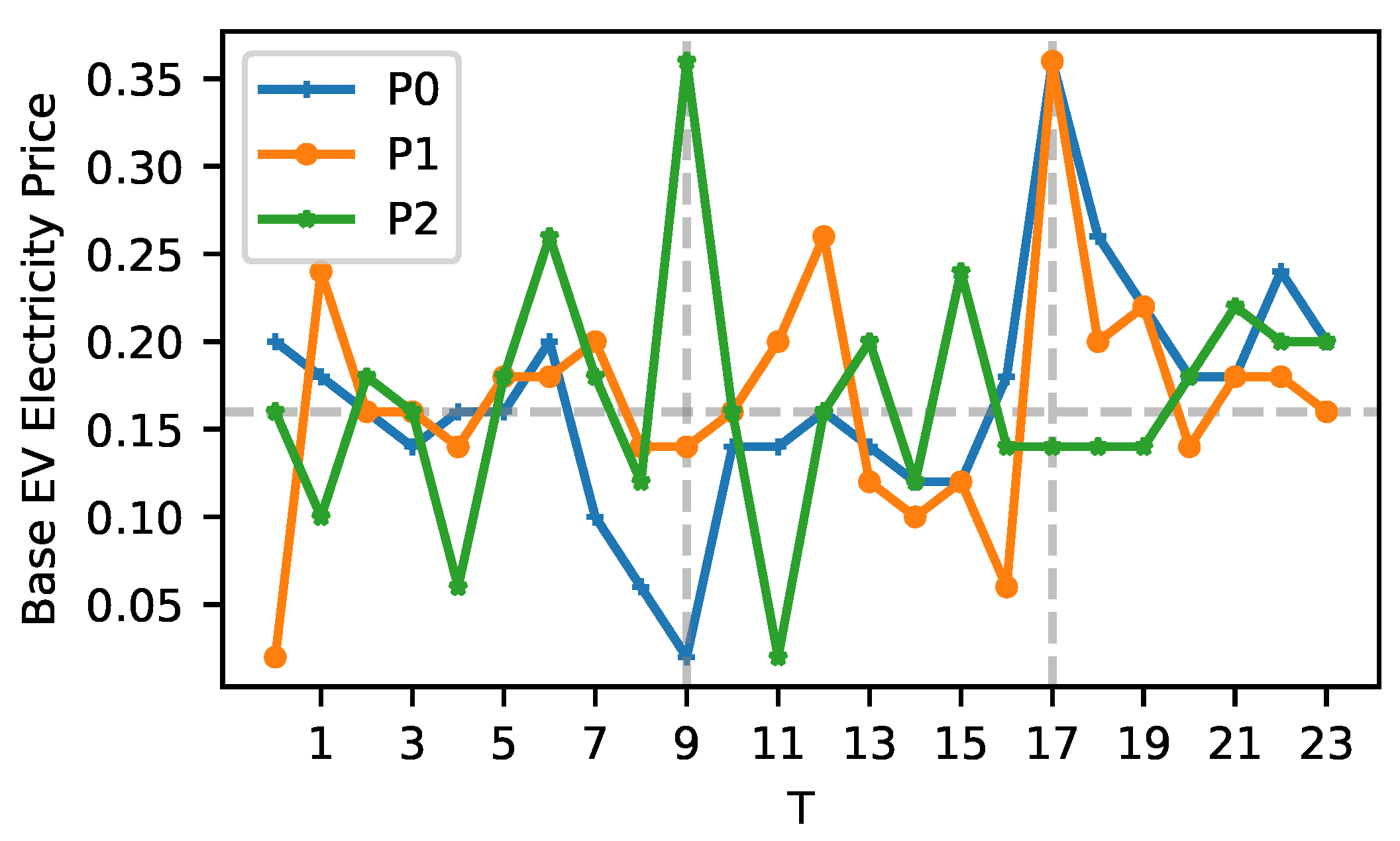

2.4. Pricing Strategy

The electricity price offered by VPP is vital to both parties in terms of charging costs and revenue. The pricing strategy itself is a research direction that attracts many researchers. To prove the concept, this paper only includes an exemplary price strategy, formulated as (

28), to demonstrate the significant impact of pricing on VPP-EV operations. The choice of pricing strategy can result in varying outcomes, potentially resulting in a win–win, win–lose, or lose–lose situation for both stakeholders—the VPP and the EVs. The exemplary pricing strategy is that the VPP proprietor gets the wholesale market electricity price for 24 h covering the whole operational period by prediction or other means. For each individual time step

t, we know the price

. The price will be shuffled in terms of the time stamp. The sum of the 24 prices will be unchanged but for individual time step

, the new price

is more likely from a different time-step of

. Once a price

is selected, it won’t be chosen anymore in the process. Consider 24 prices as 24 balls in a bag, each ball has a price

attached to it. According to our pricing strategy, for each time

ranging from 1 to 24, the pricing strategy picks a ball from the bag, and the price

attached will be selected for the current time step

. The ball is subsequently removed from the bag. At the end of the process, no ball should be left in the bag.

where

is the wholesale market price, and

is the price strategy that accepts the wholesale price and time step

t and outputs a price for the time

t.

is the base electricity price derived from the pricing strategy at time

t.

is the price multiplier which plays a significant role in revenue allocation for a VPP;

is the base EV electricity price,

is the discount of

for V2G, a positive decimal which is less than one, and

is the markup of

for charging, a positive decimal which is larger than one.

Figure 3 shows the process of deriving the EV charging/discharging price from the wholesale market price.

5. Conclusions

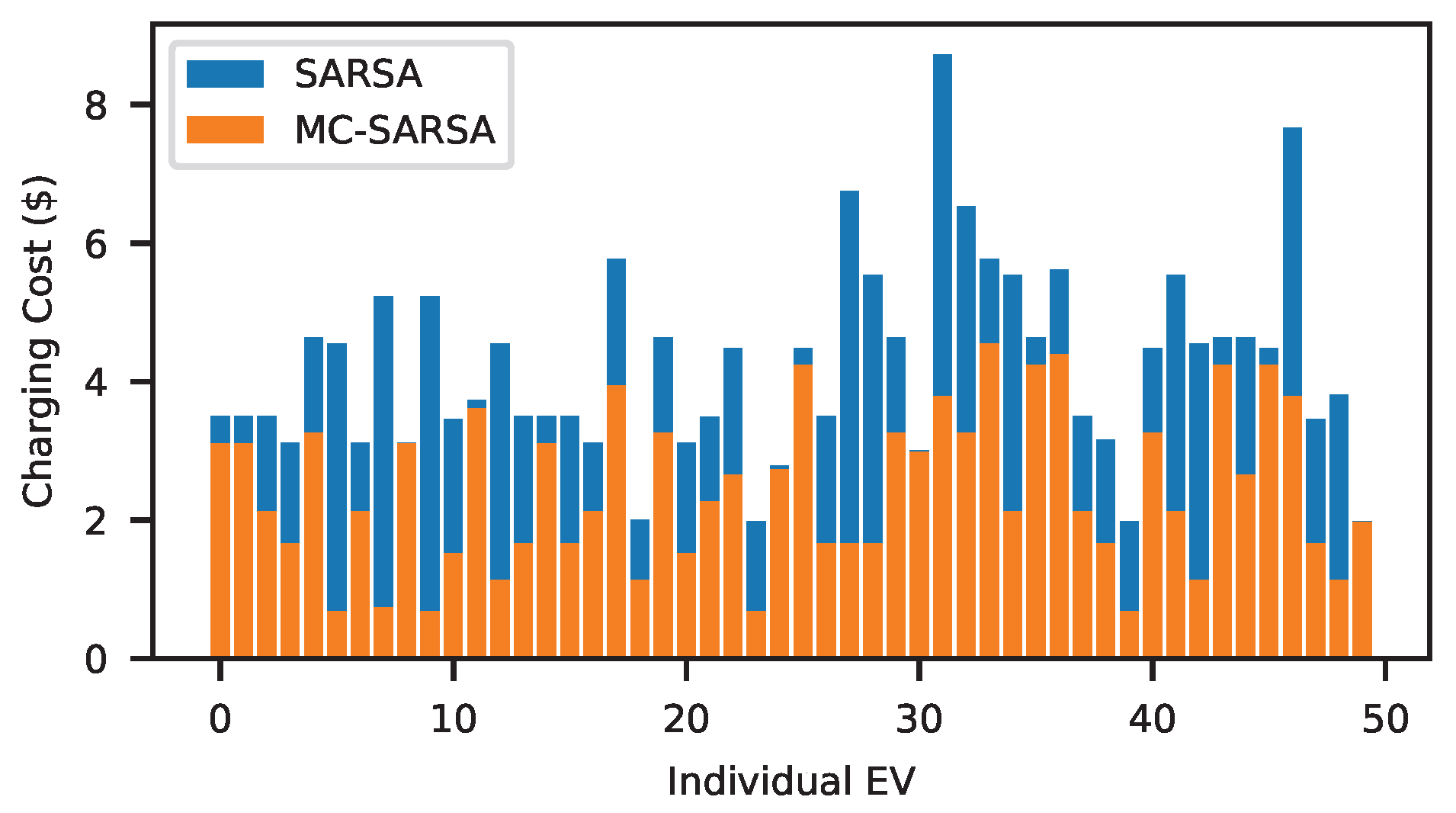

This study introduces a two-stage optimization framework designed to manage the operation of a VPP that integrates EVs, PVs, and a BESS. The VPP aims to maximize revenue from both the EV group and the electricity wholesale market, while offering reduced charging costs to the EV group to incentivize their participation in V2G discharge activities. By modeling 1000 EVs in the optimization framework, the VPP model determines the optimal solution by scheduling BESS and trading in the wholesale electricity market. Including a large number of EVs in the VPP modeling enables the business to capture more accurate and realistic data, results, and insights, thereby aiding in better business decision-making. While optimizing VPP operational modeling, gradient-based programming leverages neural networks as a powerful tool for fast and efficient optimality searching in VPP modeling. Custom loss functions for large neural networks overcome the limitations of traditional programming methods, such as strict linearity, convexity, and limited scales of decision variables. MC-SARSA increases the convergence speed for optimizing EV charging and discharging operations, delivering more optimal results within a reasonable time limit. The simulation results demonstrate that, under some charging strategy and EV electricity price selection, optimizing the operations of EVs can lead to a 26.38% reduction in the charging costs for 1000 EVs and the VPP revenue increases by 27.83% with the implementation of V2G services.

Modeling under idealized grid conditions limits the applicability of the findings to real-world networks, as grid constraints can influence feasible power flows and economic outcomes. Future research can extend the model to incorporate detailed grid-level constraints and network-aware optimization. Incorporating a more comprehensive benchmarking and discussion of computational efficiency and convergence would further strengthen the methodological foundation.

The integration of stochastic or robust optimization and transfer learning to mitigate the uncertainties identified in the limitation section can further improve the adaptability and reliability of the proposed method. Moreover, investigating the iterative optimization of EV electricity pricing within a bi-level framework represents a promising direction. In addition, studying the impacts of limited charging infrastructure on VPP profitability and the charging/discharging behaviors of a large number of EVs remains an important area for further exploration.