2.1. Geometric Module Design

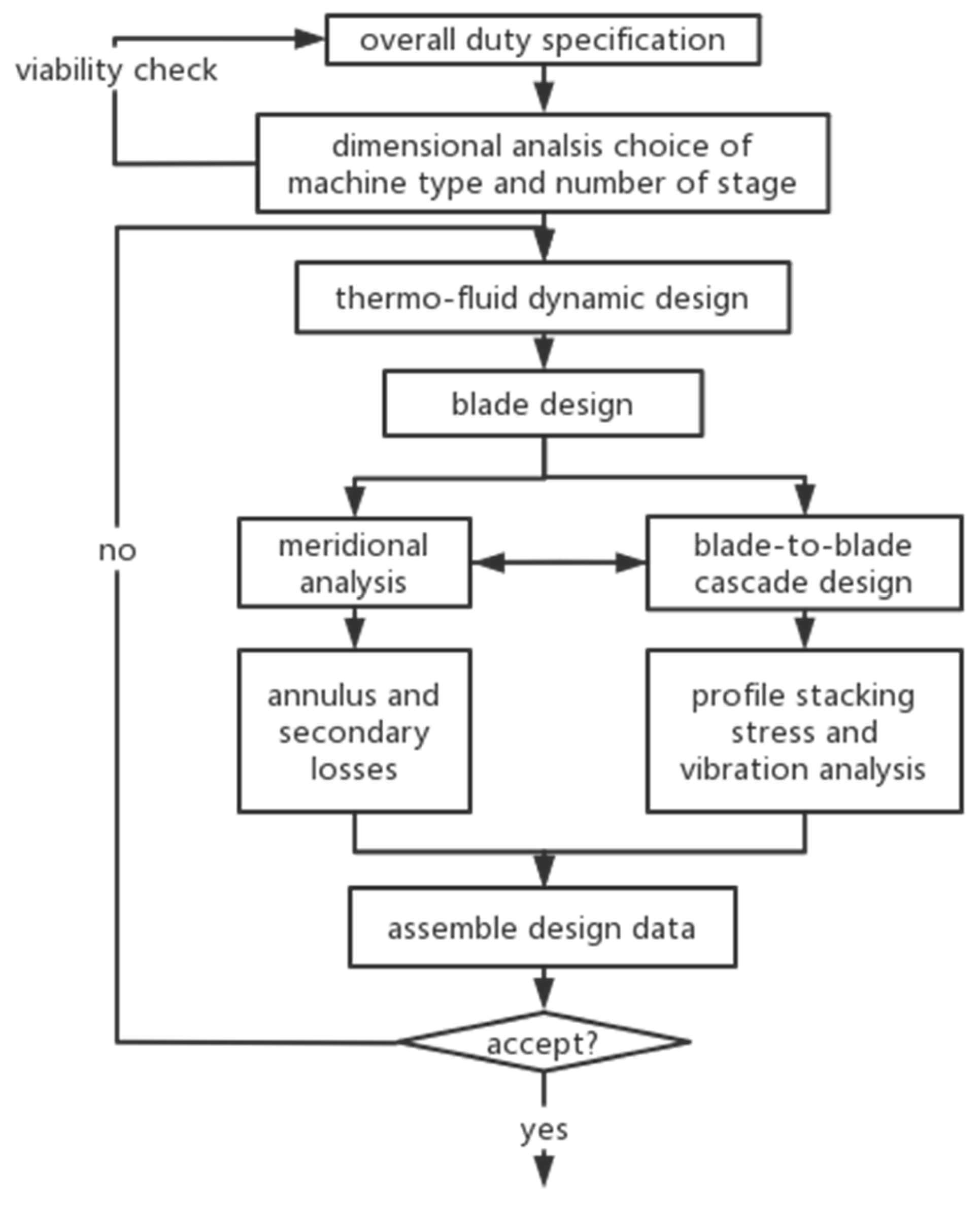

In this study, the axial turbine design software AXIAL 8.8.15.0 is used for one-dimensional design. The design process in AXIAL 8.8.15.0 consists of two steps: preliminary design and detailed design. The preliminary design determines the initial design based on parameters such as initial temperature, initial pressure, back pressure, mass flow rate, and rotational speed. The detailed design involves adjusting parameters such as blade thickness, blade chord length, trailing edge thickness, and blade angles to achieve turbine performance closer to the design values. The design process is illustrated in

Figure 1. First, the type of machinery and number of stages needs to be determined. Then follows the methodology proposed by Lewis to determine the thermodynamic parameters and velocity triangles along the turbine centerline, which involves calculations of two dimensionless parameters [

25]. Finally proceeds with blade design and analysis to complete the blade design process. During this process, operations such as meridional design and blade-to-blade design need to be performed.

During the preliminary design process in the AXIAL 8.8.15.0 software, the Geo (P0T0Ang-P) mode is selected as the design method. This method calculates the initial geometric parameters based on given inlet pressure, inlet temperature, inlet flow angle, outlet static pressure, mean radius, flow coefficient, and load coefficient. The software sets the inlet flow type to subsonic mode, with an inlet flow angle of 0 degrees. Based on the correlation between the flow coefficient and the load coefficient in the Smith diagram and the recommended values from AXIAL 8.8.15.0, the flow coefficient was selected as 0.6 [

26]. The load coefficient is automatically selected based on the equation

[

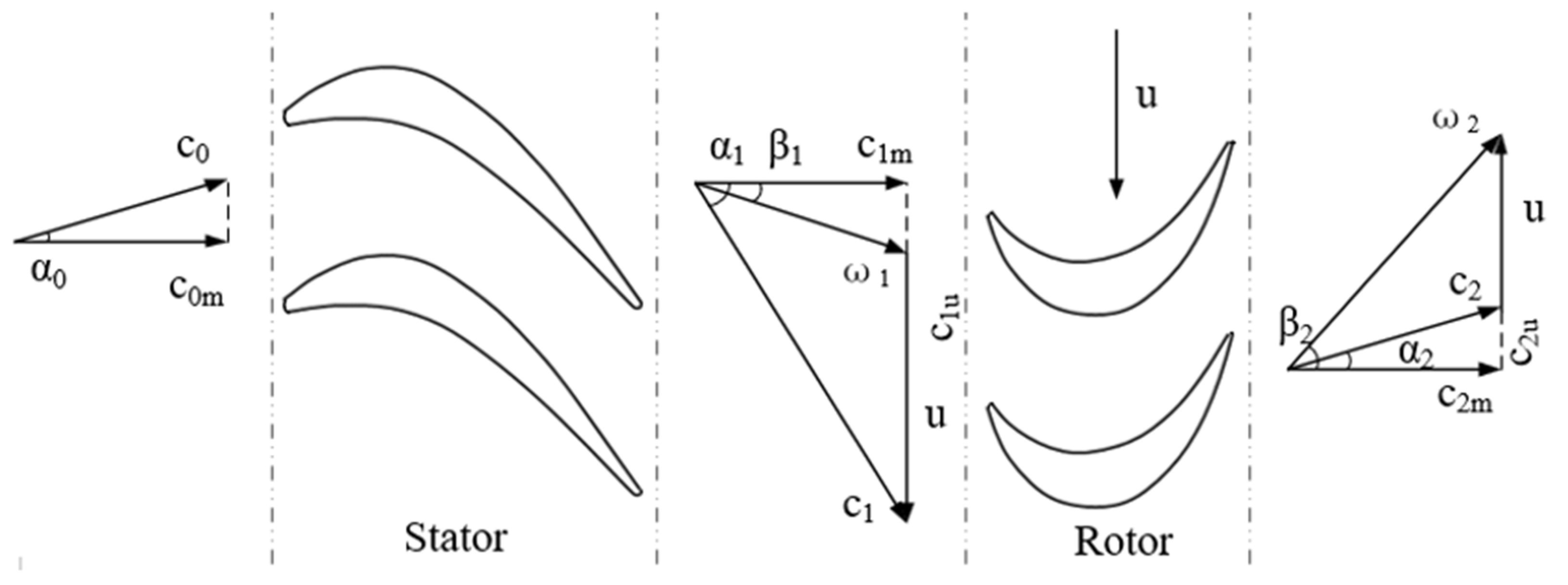

25]. Based on the flow coefficient and load coefficient, the speed parameters are calculated, as show in Equations (1)–(7), thus the speed triangle of the axial-flow turbine is determined and presented in

Figure 2.

where

α1 represents stator outlet absolute flow angle;

β2 represents rotor outlet relative flow angle;

φ represents flow coefficient;

ψ represents load coefficient.

R represents reaction;

N represents rotational speed;

u represents tangential velocity;

c1 represents stator outlet absolute velocity;

ω2 represents relative velocity;

cm represents axial component of absolute velocity;

cu represents tangential component of absolute velocity.

Furthermore, Axial 8.8.15.0 retrieves the property parameter table of carbon dioxide from the NIST Refprop thermophysical property database to conduct thermodynamic calculations for the turbine. Assuming the flow process is adiabatic, according to the Euler equation, the power of the turbine can be derived, as shown in Equations (8) and (9).

Isentropic efficiency is important parameters for monitoring turbine performance, as shown in Equation (10).

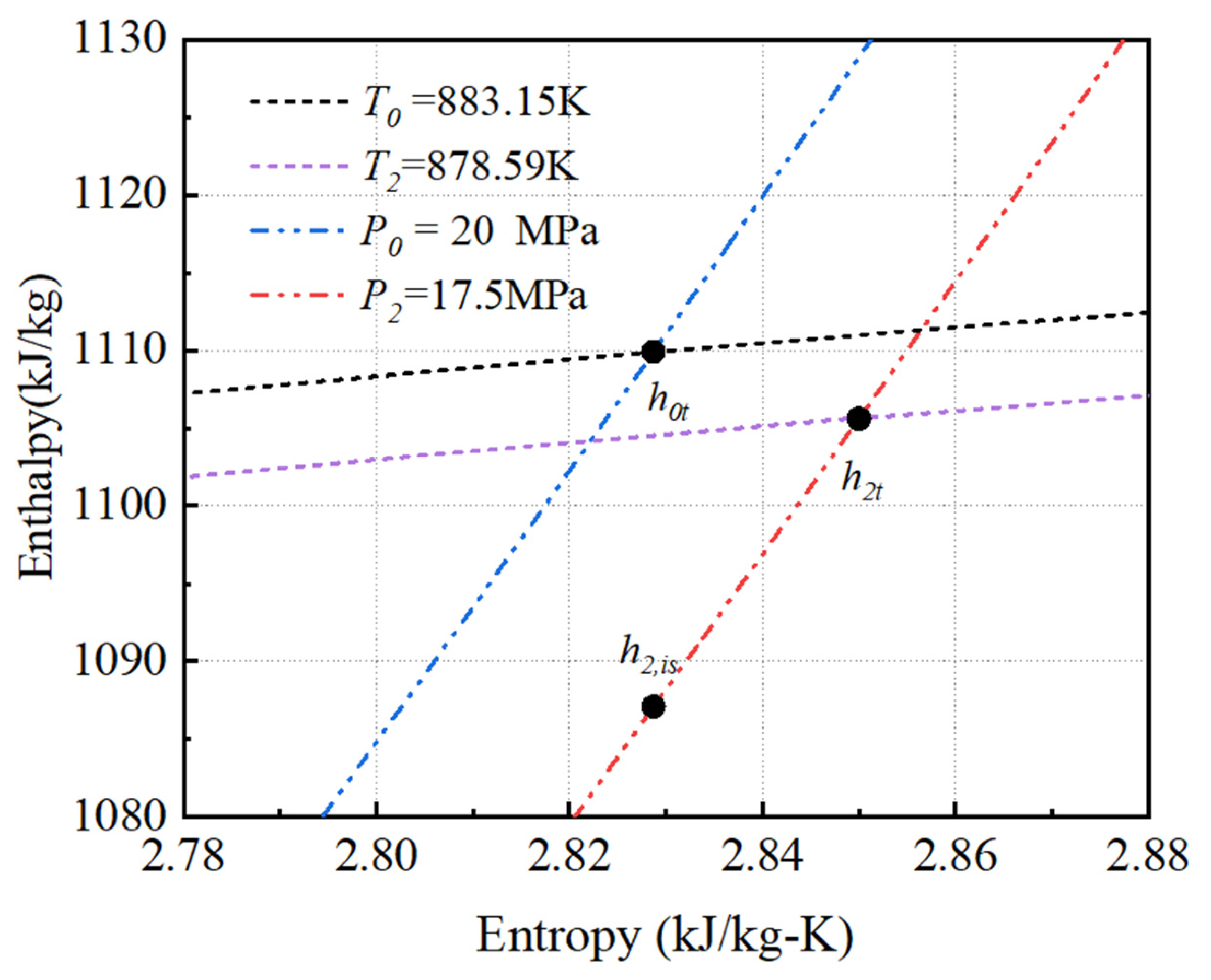

To exhibition enthalpy values at main points used to calculate efficiency and power, The Entropy and Enthalpy figure are shown in

Figure 3, where

T0 represents the inlet temperature;

T2 represents the outlet temperature;

P0 represents the inlet pressure;

P2 represents the outlet pressure;

h0t represents the total specific enthalpy at the inlet of the stationary blades,

h2t represents the total specific enthalpy at the outlet of the moving blades, and

h2,is represents the specific isentropic enthalpy at the outlet of the moving blades.

The enthalpy drop of the sCO

2 flowing through the turbine is partly used for doing work, and the other part is dissipated in the form of flow loss. The total loss consists of four parts as shown in Equation (11).

where

Yt represents total loss;

Yp represents profile Loss;

Ys represents secondary loss;

YTE represents trailing-edge-thickness loss;

YTC represents tip clearance losses.

2.3. Mass Design Approach and Variable Selection

The purpose of turbine design in this study is to be equipped on Small Modular Reactors, requiring small size and appropriate power. Therefore, supercritical carbon dioxide is chosen as the operating fluid and the designed target power is 150 kW. Turbines for nuclear power generation need to adapt to high-temperature and high-pressure initial boundary conditions. And the research conducted by Chen et al. revealed that turbine achieved the highest efficiency at an inlet temperature of 610 °C and an inlet pressure of 20 MPa [

28]. Therefore, the inlet boundary conditions with an initial temperature (

T0) of 883.15 K and an initial pressure (

P0) of 20 MPa are selected. In addition, suitable back pressure (

P2), rotational speed (

N), mean radius (

Rm), and mass flow rate (

Qm) need to be selected to meet the design power of 150 kW and high isentropic efficiency. To achieve this target, a large number of design points were screened during the preliminary design process, as described below:

Selecting suitable design points among the four variables: back pressure, rotational speed, mean radius, and mass flow rate requires extensive computational effort. To determine reasonable design points in the shortest possible time, it is necessary to differentiate between primary variables and secondary variables among the four variables.

Considering the wide range and large periodicity of the selection for rotational speed and back pressure, and referring to the research by Chen et al. and Al et al. on axial-flow turbines under variable operating conditions, the final choice for the rotational speed interval is 10,000 rpm, while the back pressure interval is 1000 kPa [

28,

29]. During the preliminary design process, it was found that the values of rotational speed and back pressure are not constrained by mean radius and mass flow rate. However, back pressure and rotational speed limit the minimum mean radius within the subsonic range of the turbine. As shown in

Table 2, when the back pressure is fixed, the allowable minimum mean radius within the subsonic range decreases as the rotational speed increases. The selection of mean radius further constrains the value of mass flow rate. Excessive mass flow rate at the same mean radius can lead to channel blockage, while insufficient mass flow rate can result in low power and efficiency. Therefore, based on these considerations, rotational speed and back pressure are determined as the primary variables.

The span of values for mean radius and mass flow rate is small. As the design goal is a small-sized and low-power turbine, the values of mean radius and mass flow rate are both restricted. The ranges and intervals for selection are small. The mass flow rate appeared as a variable during the design stage, so the exact appropriate value was unknown. Referring to the 15 WM turbine designed by Zhang et al., with a mass flow rate of 150 kg/s, and the turbine designed by Ying et al., with an average radius of 4.6 cm and a mass flow rate of 10 kg/s [

30,

31]. After reducing the parameters proportionally and expanding the selection range, the values of mean radius are limited within the range of 2~10 cm, and the values of mass flow rate are limited within the range of 2~15 kg/s. Moreover, once the rotational speed and back pressure are determined, selecting a too small mass flow rate will result in insufficient blade height, while selecting a too large mass flow rate will lead to excessive blade height and turbine deformity. Similar restrictions apply to the selection of mean radius. Therefore, it can be concluded that the selection ranges for mean radius and mass flow rate are constrained by rotational speed and back pressure, making them secondary variables.

Based on the data provided in

Table 2, the design rotational speed can be directly determined. The larger the rotation speed, the smaller the size that can be achieved in the subsonic range. To achieve the design goal of a small-sized turbine, the maximum value should be chosen for the rotational speed. Currently, the speeds of axial turbines are normally less than 50,000 rpm [

32]. Therefore, in this study the rotational speed is set at 40,000 rpm. Next, by comparing the influence patterns of mean radius and mass flow rate under different back pressures on the design results, reasonable values for back pressure, mean radius, and mass flow rate can be further determined.

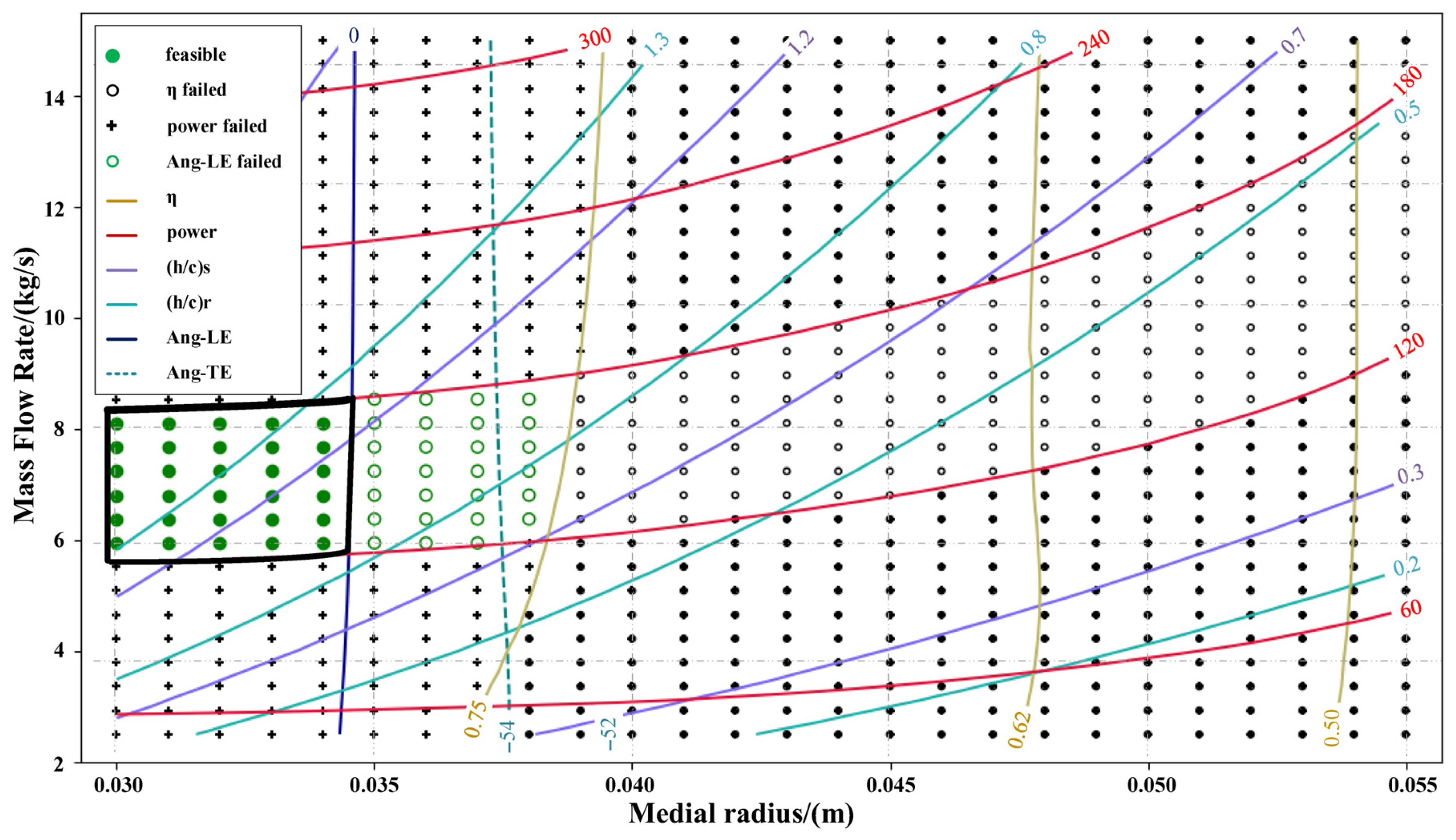

The primary variables and secondary variables are arrayed as follows: The research range for rotational speed in this study is from 20,000 rpm to 50,000 rpm with an interval of 10,000 rpm. The research range for back pressure is from 16 MPa to 18 MPa with an interval of 1 MPa. Due to space limitations, only one example was provided with a back pressure of 16 MPa and a rotational speed of 40,000 rpm, as shown in

Table 3. Under the conditions of a back pressure of 16 MPa and a rotational speed of 40,000 rpm, the minimum mean radius is 0.035 m, and the suitable range for mass flow rate is 2.5 kg/s to 15 kg/s. Therefore, 30 equally spaced design values are selected within the range of mean radius from 0.035 m to 0.055 m, and another set of 30 equally spaced design values are selected within the range of mass flow rate from 2.5 kg/s to 15 kg/s. A total of 900 design points are established and imported into the AXIAL 8.8.15.0 software for batch calculations.

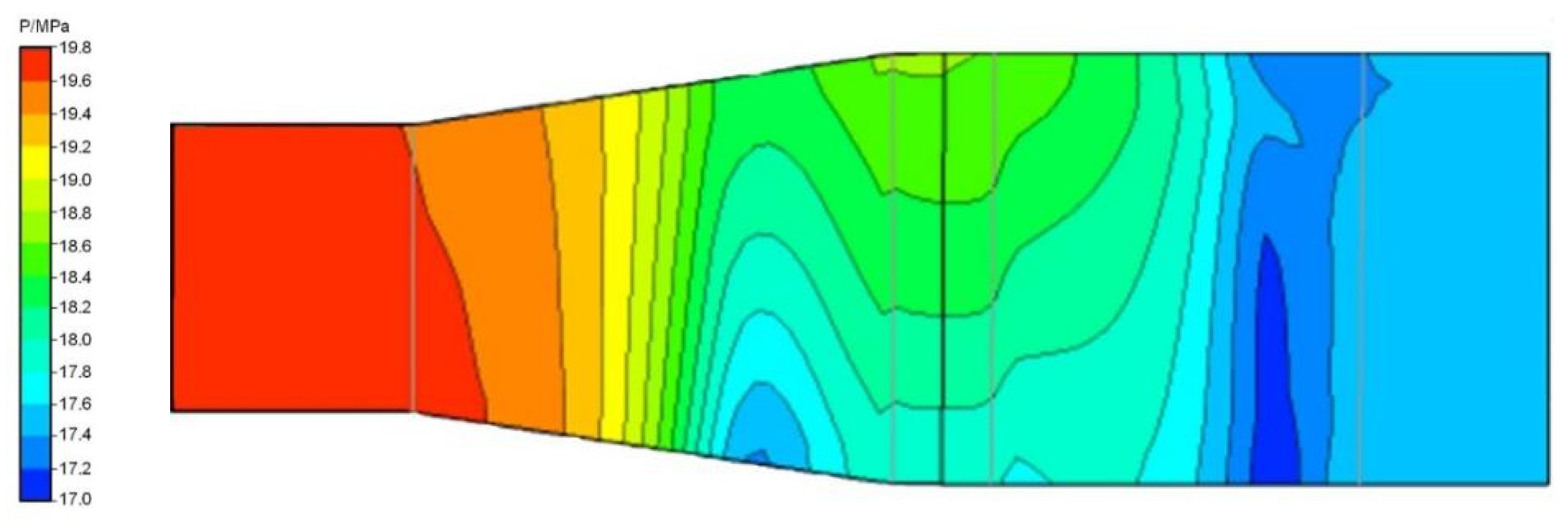

2.4. Analysis of Design Results

Batch initial calculations are performed for all design point schemes, thereby obtaining all the design point parameter information.

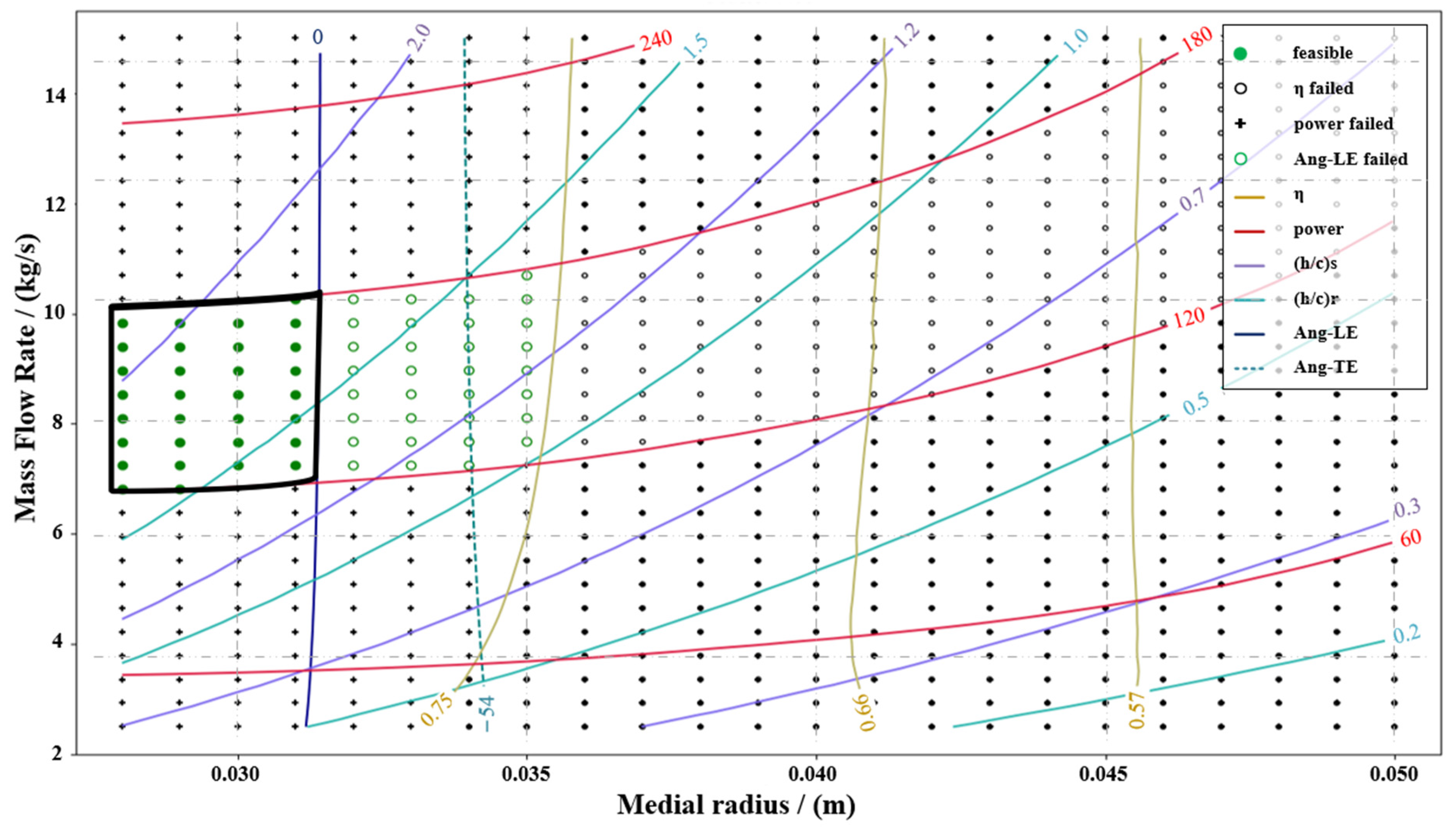

Figure 5 shows the design parameter results for different mass flow rates and mean radius corresponding to a back pressure of 16 MPa and a rotational speed of 40,000 rpm. It consists of 900 design points formed by a cross-array of 30 different mass flow rates and 30 different mean radius.

AXIAL 8.8.15.0 recorded detailed parameters for each design point. This study selected parameters that have guiding significance in the design process, including isentropic efficiency, power, relative blade height (h/c), and inlet deflection angle of the rotor and stator. The contour lines of these parameters are presented in the figure, indicating certain limit values, while different shapes of dots represent design solutions within different limit regions. The target design power of this article is 150 kW, so a power with an error of 20% is selected as the power contour line for successful design, where the contour lines are 120 kW and 180 kW. The lowest design efficiency is selected as 75%, where on the left side of the contour lines are all greater than 75% considered a successful design, while the efficiency on the right side is less than 75% considered a failure. As for the moving blades inlet airflow angle, the angle must be designed to be greater than 0 (positive value) to achieve a “shock-free inlet” and ensure the efficient and stable operation of the turbine, which means that the moving blades inlet airflow angle contour lines less than 0 are design failures. So, the reasonable design point region is trimmed from the contour lines of 120 kW and 180 kW close to the target power, the contour line of 75% isentroentropy efficiency, and the contour line of 0 moving blade inlet airflow Angle. The most reasonable target design value lies in the middle of this region, which is displayed in the black box, and any design points outside the region do not meet the design requirements.

From

Figure 5, it can be observed that the isentropic efficiency reaches 75% at a mean radius of 0.045 m. Power and efficiency increase with the increase in mass flow rate. When the average radius is 0.05 m, the power value at the mass flow rate of 5.08 kg/s is 120 kW, and the efficiency is 69.58%. While at the mass flow rate of 7.23 kg/s, the power value is 173.37 kW, and the efficiency is 69.67%. In comparison, the mass flow increased by 42%, the power rose by 44.5%, and the efficiency has a slight increase. For the same mass flow rate, larger mean radius results in lower power. For the case where the average radius is 0.046 m, the power value at the mass flow rate of 5.08 kg/s is 126.35 kW, and the efficiency is 73.85%. Compared with the case where the radius is 0.05 m, the power has increased by 5.3% and the efficiency has increased by 6.1%. As the average radius increases, in order to maintain the same mass flow rate, the blade height must be reduced accordingly, which leads to a significant increase in secondary flow loss. To mitigate the impact of this secondary flow loss, the outlet relative airflow angle will deviate from the ideal

β2, resulting in a decrease in the absolute value of the tangential component of the outlet relative velocity and an increase in

c2u, leading to a decrease in power. This inevitably leads to a decrease in power and efficiency. Power and isentropic efficiency are the most important parameters in the preliminary design of a turbine. The minimum mean radius and maximum mass flow rate achieve the highest isentropic efficiency and maximum power.

Design results with larger mass flow rate and smaller mean radius exhibit higher relative blade heights, resulting in slender and long blade shapes that often have lower strength and are not suitable for high-parameter turbine designs. For example, when Qm = 15 kg/s and Rm = 0.035 m, the blade height is 7.69 mm, and the ratio of blade height to chord length reaches 1.8774, which increases the likelihood of blade fracture. Design results with excessively small mass flow rate lead to very low blade heights (less than 1 mm) and smaller flow areas, rendering them impractical. When the mean radius is less than 0.04 m, an outlet deflection angle greater than 0 degrees for the rotor meets the design requirements. Otherwise, a negative inlet deflection angle for the moving blades can cause abnormal flow, increased turbulence, and higher losses. The target design power in this study is 150 kW, and the reasonable design points fall within the region of approximately 5 kg/s mass flow rate and a mean radius of 0.035~0.040 m. In this region, the relative blade heights of the stators range between 0.6 and 1.0, while those of the rotors range from 0.3 to 0.7. These relatively flat and low-profile blades exhibit strong resistance to high-parameter airflow, aligning with the design expectations.

Using a design point parameter plot like

Figure 5 can help consider various factors such as power, isentropic efficiency, and blade shape comprehensively. It allows for multidimensional comparisons of design points in different regions to ultimately find a reasonable design region and the best design point. Under the conditions of 16 MPa and 40,000 rpm, the optimal design mass flow rate is 5.09 kg/s, and the optimal design mean radius is 0.038 m, positioning this design point at the center of the design region. The result of the optimal design point indicates a power of 145.62 kW, an isentropic efficiency of 78.61%, an inlet deflection angle of the rotor of 13.08 degrees, an outlet deflection angle of the rotor of −56.42 degrees, a relative blade height of 0.5864 for the stator, and a relative blade height of 0.5878 for the rotor. Additionally, information in the figure includes blade solidity, with a solidity value of 1.43 for the stator and 1.52 for the rotor.

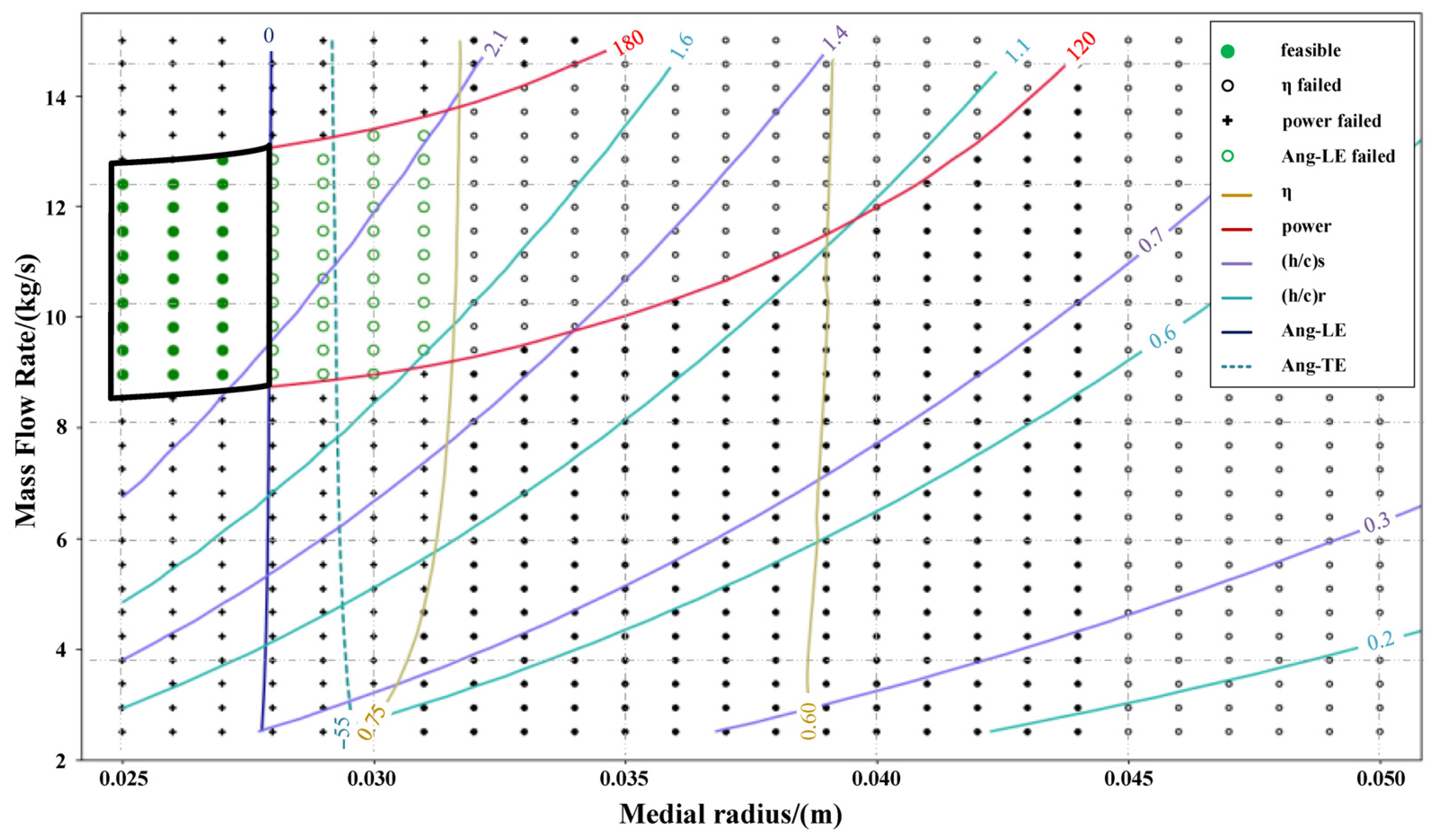

Figure 6 displays the result parameter map for various design points at a rotational speed of 40,000 rpm and a back pressure of 17 MPa. The patterns of parameters such as power, isentropic efficiency, and blade shape are similar to those in

Figure 5. The reasonable design region is also constrained by the same factors, being trimmed by contours of reasonable power values and the limit contours of the inlet deflection angle of the rotor. Reasonable design points fall within the range of mean radius 0.030~0.034 m and mass flow rate 6~8 kg/s, which have moved upward compared to the 16 MPa back pressure, with the optimal design point occurring at a smaller mean radius and larger mass flow rate.

In

Figure 6, all the power contour lines have shifted upward compared to

Figure 5 and can be observed that as the back pressure increases, the power and isentropic efficiency of design points with the same mean radius and mass flow rate decrease. When the back pressure increases to 7 MPa, for the case where the average radius is 0.05 m, the power value at the mass flow rate of 5.08 kg/s is 105.58 kW, and the efficiency is 57.68%. Compared to the 16 MPa situation, the power and efficiency have decreased by 12% and 17.1%, respectively. This is related to the reduction in the expansion level of the carbon dioxide stream, resulting in weakened performance of the turbine. The variation in the relative blade height of the stator with back pressure is not significant, while the range of variation in the relative blade height of the rotor converges as the back pressure increases. In the reasonable design region, the relative blade height of the stator ranges from 1.0 to 1.4, and the relative blade height of the rotor ranges from 0.8 to 1.7. Both show a more noticeable improvement compared to the reasonable design region under the 16 MPa back pressure. This suggests that as the back pressure increases, the blade shape tends to become slender and longer.

The most reasonable design point in

Figure 6 is still located at the center of the reasonable design region. The optimal design point has a mean radius of 0.032 m and a mass flow rate of 7.24 kg/s. The design results indicate that this design point has a power of 154.80 kW, an isentropic efficiency of 80.11%, an inlet deflection angle of the rotor of 17.54 degrees, an outlet deflection angle of the rotor of −56.38 degrees, a relative blade height of 1.313 for the stator, and a relative blade height of 1.396 for the rotor. Additionally, the blade solidity for this solution is 1.41 for the stator and 1.55 for the rotor.

Figure 7 presents the result parameter map for design points at a rotational speed of 40,000 rpm and a back pressure of 18 MPa. The constraints on the reasonable design region are the same as in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. Reasonable design points fall within the range of mean radius 0.025~0.028 m and mass flow rate 8.5~12.5 kg/s. Compared with the above two results, these points have further shifted upward, with a smaller mean radius and larger mass flow rate. The optimal design point has a mean radius of 0.026 m and a mass flow rate of 11.12 kg/s. And the design results indicate that this design point has a power of 155.77 kW, an isentropic efficiency of 80.51%, an inlet deflection angle of the rotor of 16.47 degrees, an outlet deflection angle of the rotor of −56.35 degrees, a relative blade height of 2.86 for the stator, and a relative blade height of 3.05 for the rotor. Additionally, the blade solidity for this solution is 1.43 for the stator and 1.54 for the rotor.

Comparing the optimal design points in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, it can be observed that as the back pressure increases, the optimal design points have lower mean radius, higher mass flow rates, improved isentropic efficiency, increased inlet deflection angles for the rotor, and higher relative blade heights for both the stator and rotor.

Table 4 provides a comparison of the parameters for the optimal design points in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The most significant parameters that vary among the design points are the mean radius, mass flow rate, and relative blade height of the rotor and stator. Other parameters remain at relatively reasonable levels. This study aims to design a small-sized axial flow turbine, making the mean radius a crucial parameter of interest.

Table 4 indicates that as the back pressure increases, the mean radius of the turbine decreases, resulting in a smaller final turbine size. However, as the mean radius decreases, the mass flow rate gradually increases to maintain the desired power and isentropic efficiency. Simultaneously, the relative blade heights of the rotor and stator also increase significantly.

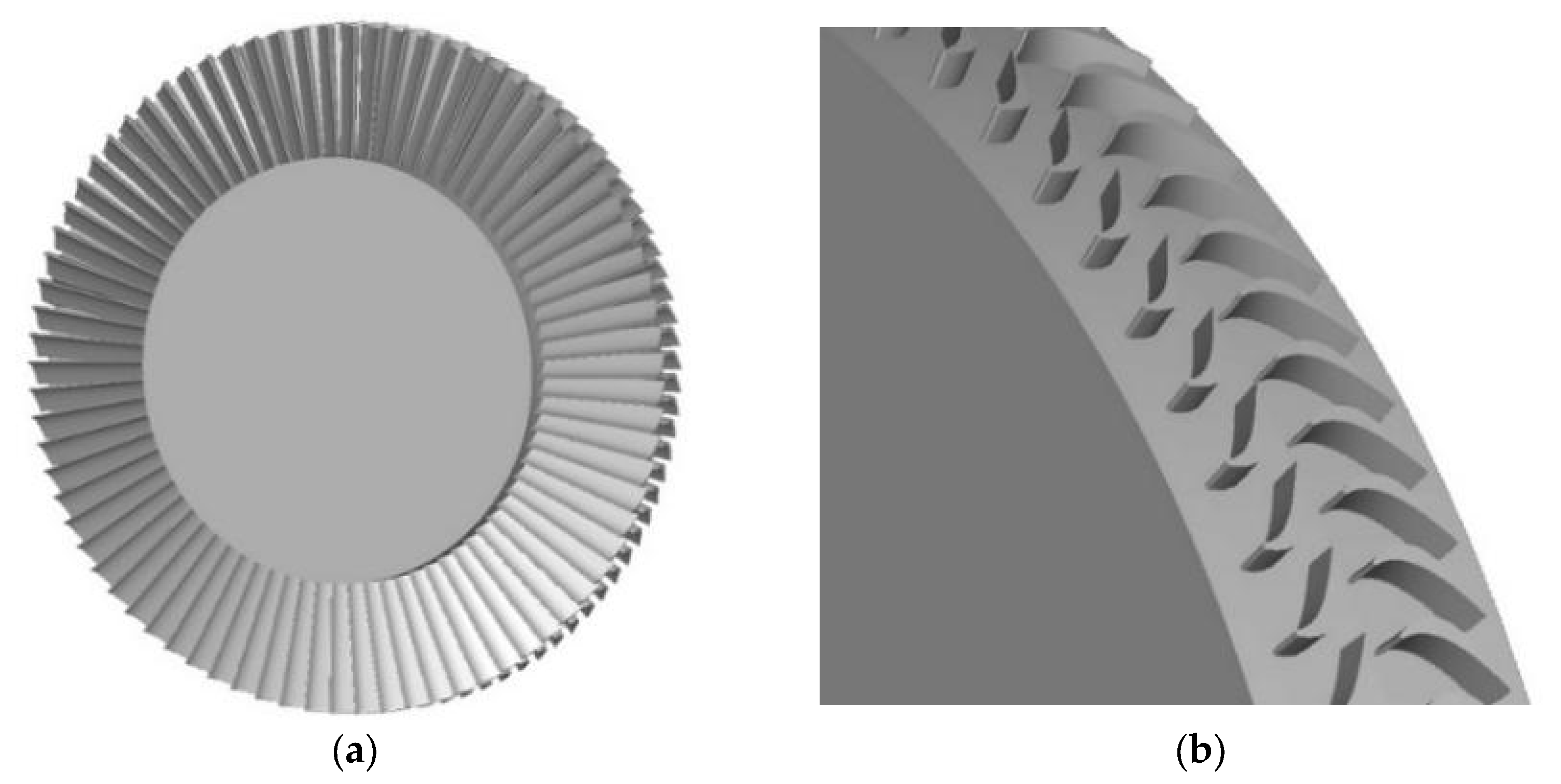

High blade heights are not suitable for high-parameter turbines.

Figure 8a shows the shapes of the stator and rotor with relative blade heights of 3.97 and 4.11, respectively. The blades are noticeably slender, with a height that accounts for nearly half of the mean radius. This blade shape is more fragile. On the other hand, if the relative blade height is too low, it not only reduces turbine efficiency but also poses greater manufacturing challenges. Moreover, it is difficult to achieve satisfactory results in practical engineering applications.

Figure 8b illustrates the shapes of the stator and rotor with relative heights of only 0.3 and 0.31, respectively. It can be observed that the blades grow tightly against the surface of the impeller, resembling raised threads on the surface. The carbon dioxide stream passage becomes narrow, resulting in a small flow area, making it impractical for engineering applications.

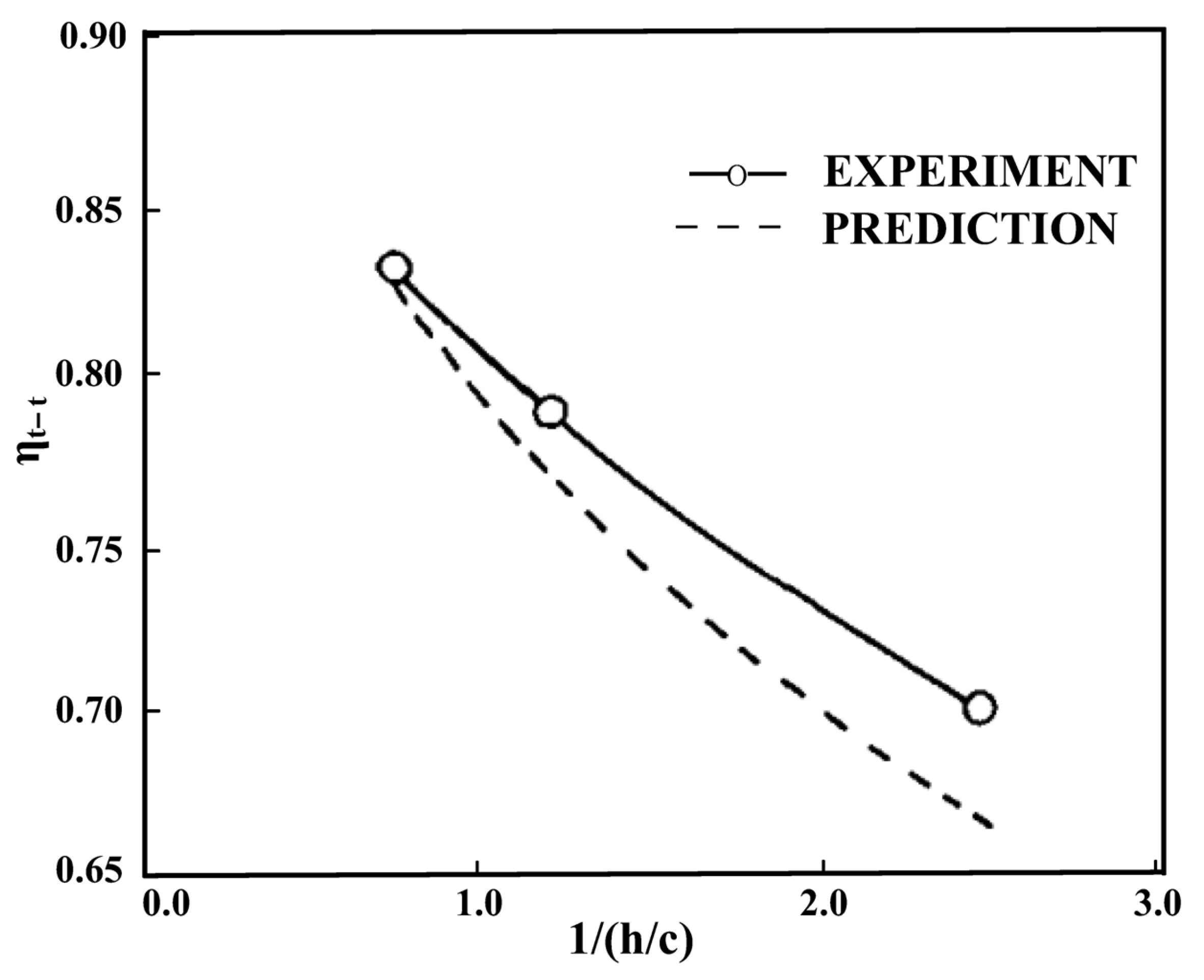

Figure 9 presents the relationship between relative blade height and turbine efficiency summarized by Kacker [

26]. Both simulation predictions and experimental values indicate that excessively low relative blade heights lead to reduced turbine efficiency. When the relative blade height is 0.5, the actual efficiency of the turbine is already below 70%. Therefore, considering the guarantee of turbine efficiency in practical applications, it is advisable to avoid using excessively low blade heights. Thus, this study selects blades with relative heights ranging from 1 to 2 as the design solution.

The optimal design points in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 only

Figure 5 satisfy the design requirements of relative blade height. However, the optimal design point in

Figure 5 can be further optimized by increasing the back pressure. Therefore, this study adds a batch computation with an initial design at a rotational speed of 40,000 rpm and a back pressure of 17.5 MPa. The results are shown in

Figure 10.

The design points in

Figure 10 fall between those in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, and the trends of their parameters are similar to

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The reasonable design region is within a mass flow rate range of 7~10 kg/s and a mean radius range of 0.028~0.031 m. Within this region, the relative blade height for the stator ranges from 1.2 to 2.2, while for the rotor, it ranges from 1.3 to 1.8. The optimal design point in

Figure 10 has a mean radius of 0.030 m and a mass flow rate of 8.5 kg/s. The design results indicate that this design point has a power of 149.96 kW, an isentropic efficiency of 79.91%, an inlet deflection angle of the rotor of 10.21 degrees, an outlet deflection angle of the rotor of −56.31 degrees, a relative blade height of 1.625 for the stator, and a relative blade height of 1.699 for the rotor. Additionally, the blade solidity for this solution is 1.43 for the stator and 1.50 for the rotor. This solution has a power value closest to the design power, reasonable efficiency, reasonable inlet and outlet deflection angles for the rotor, and relative blade heights within the predetermined range. It is the most ideal design solution.

Through a large number of calculations and comparisons of preliminary variables, the optimal preliminary design parameters for the turbine have been determined. These parameters include the known initial temperature and pressure, as well as the selected rotational speed, back pressure, mean radius, and mass flow rate. By using these parameters as initial data, the entire design process of the turbine can be completed, resulting in an ideal design solution. Finally, the initial design parameters that closely approach the design target values are obtained, as shown in

Table 5.

The next step is to enter the detailed design process. In the detailed design process, the first step is to modify the number of blades, blade chord length, and axial chord length to determine a reasonable blade solidity and installation angle. Next, the trailing edge thickness and leading edge thickness are adjusted to values that are deemed reasonable based on experience. The trailing edge thickness is typically set to 0.5 mm. Then, the blade tip clearance is modified to satisfy manufacturing conditions, typically set to 0.2 mm based on experience.

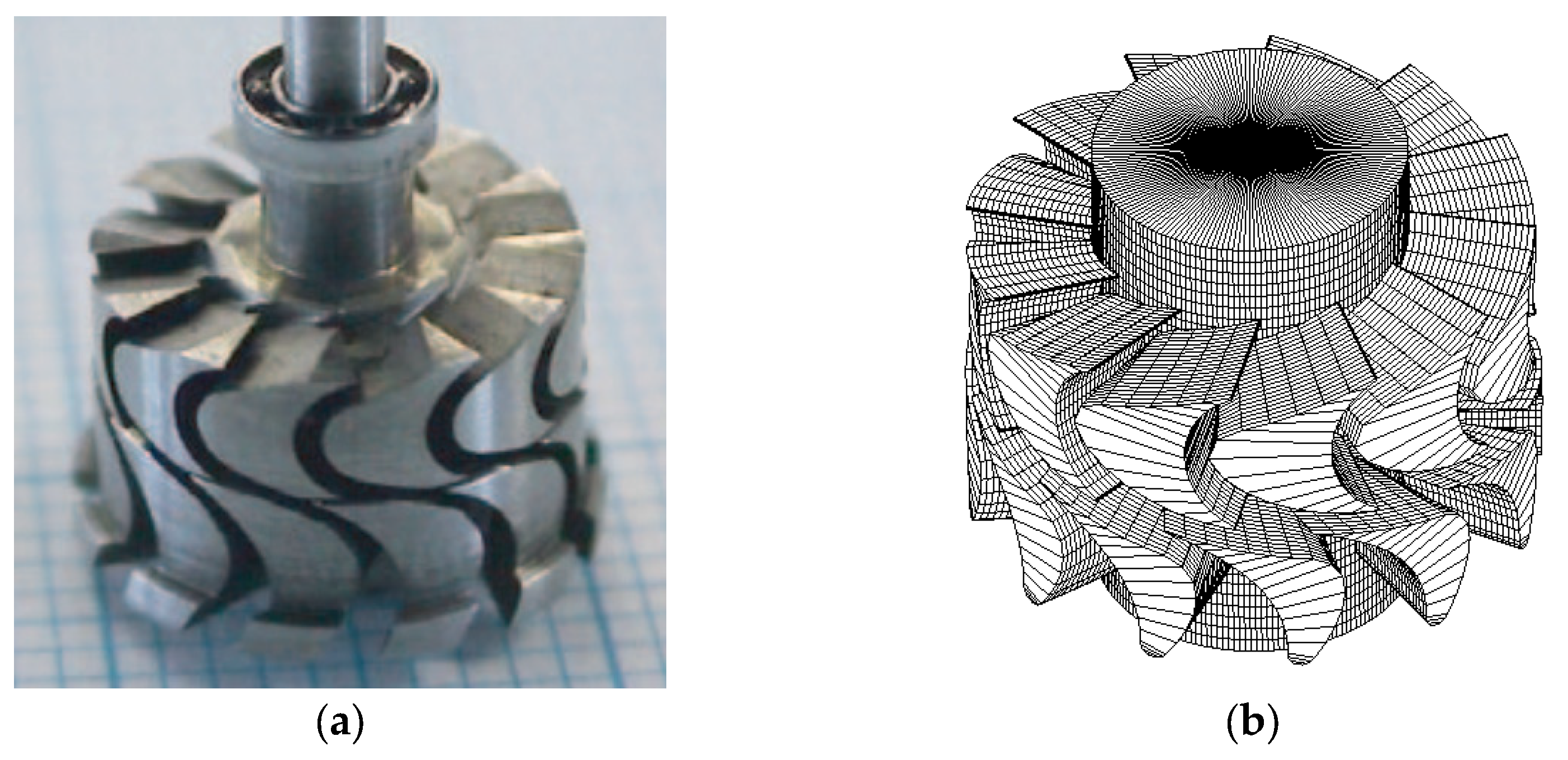

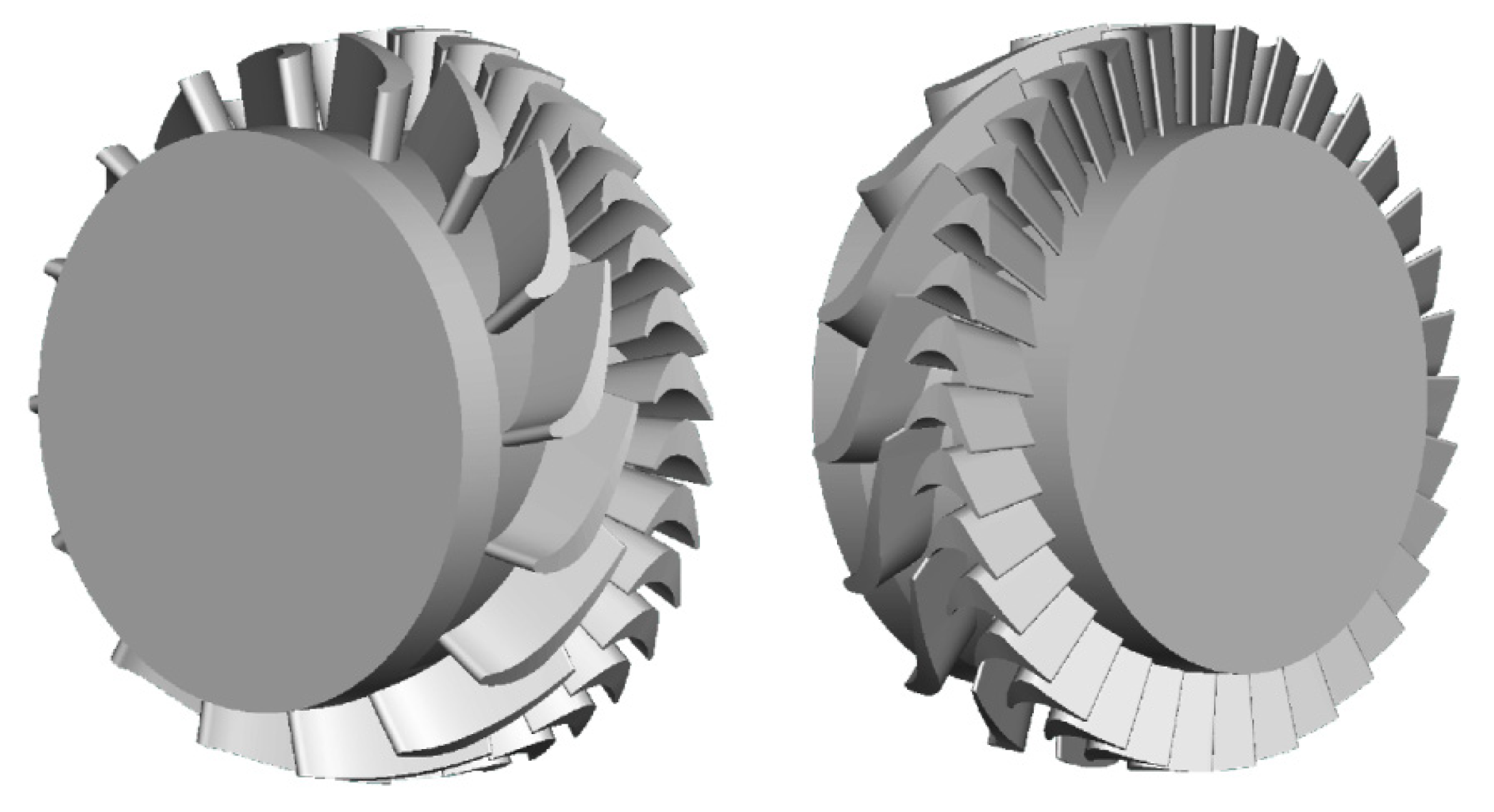

Finally, the geometric angles at the outlet of the stator, outlet of the rotor, and inlet of the rotor are adjusted to change their constraint capability on the mass flow rate, ensuring it matches the design value. With this, the complete design process concludes. The geometric parameters of the turbine design results are shown in

Table 6, and the 3D model of the design results is exported using AXCENT 8.8.20.0 software, as shown in

Figure 11.

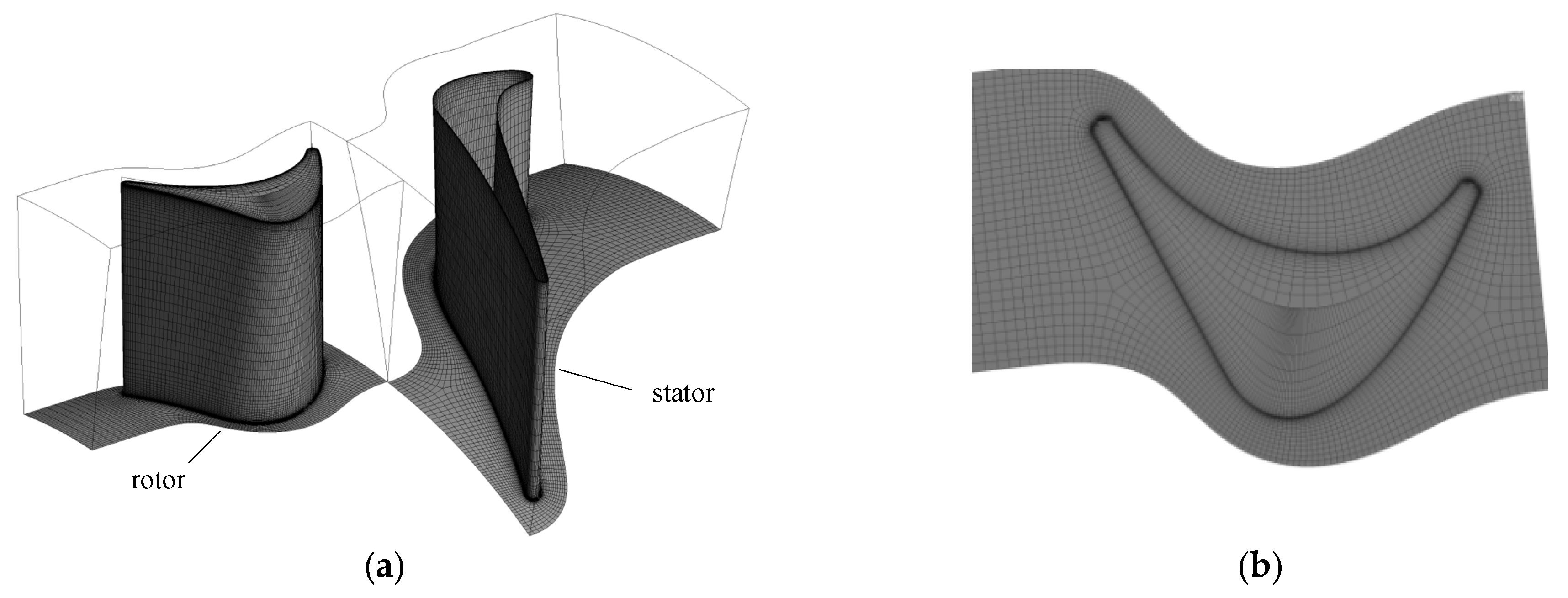

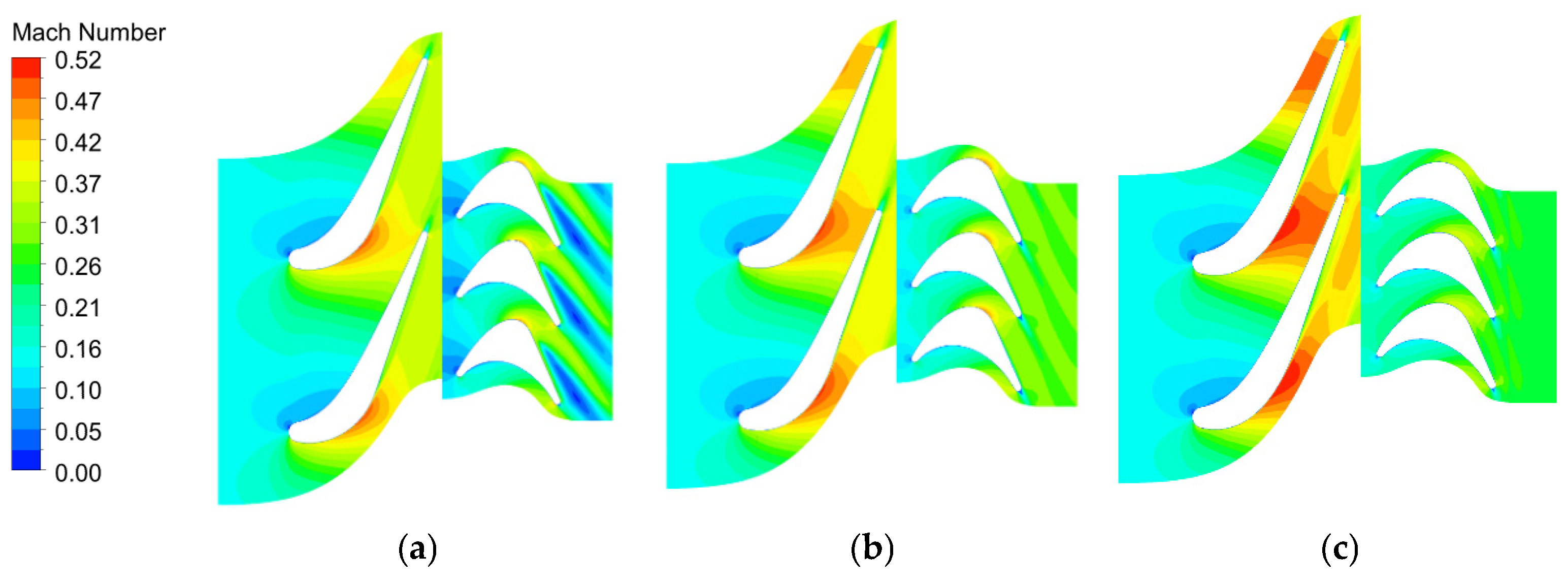

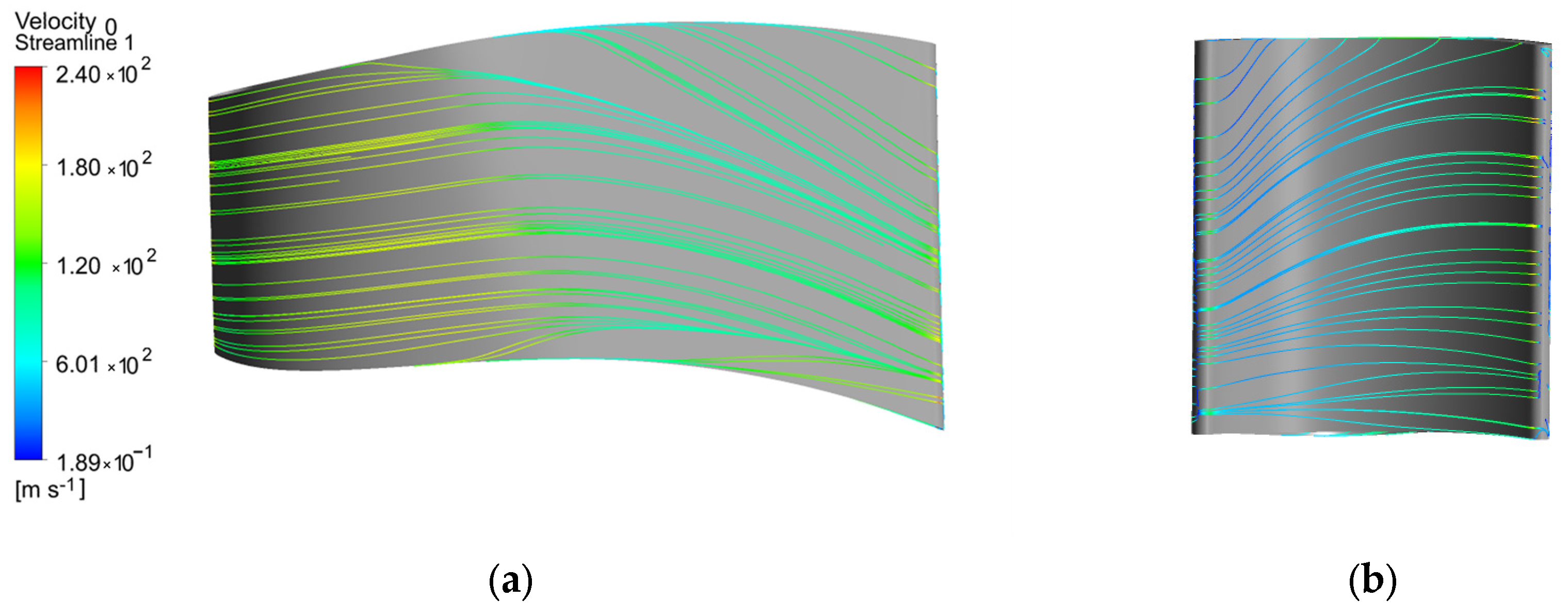

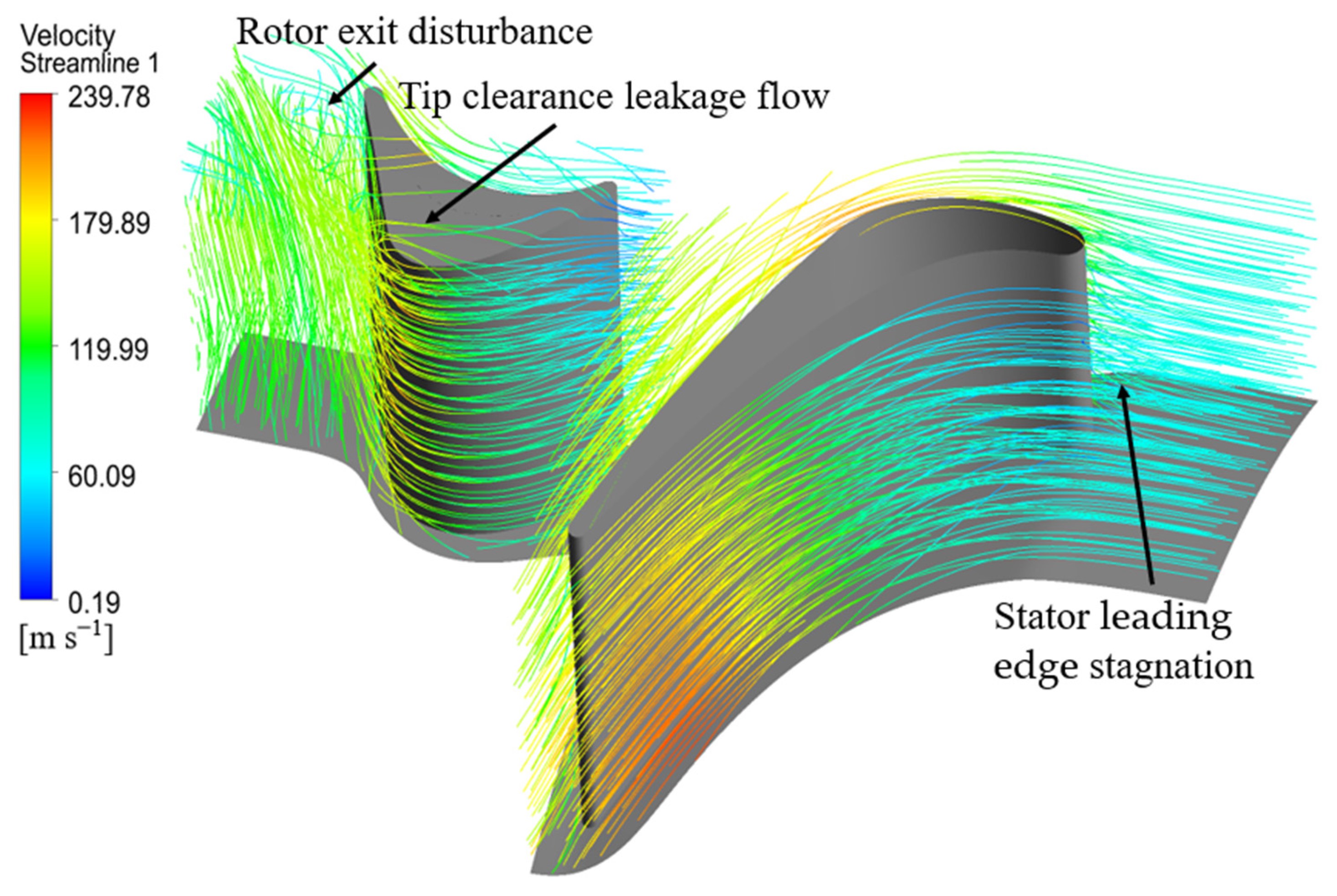

2.5. Grid Independence Verification

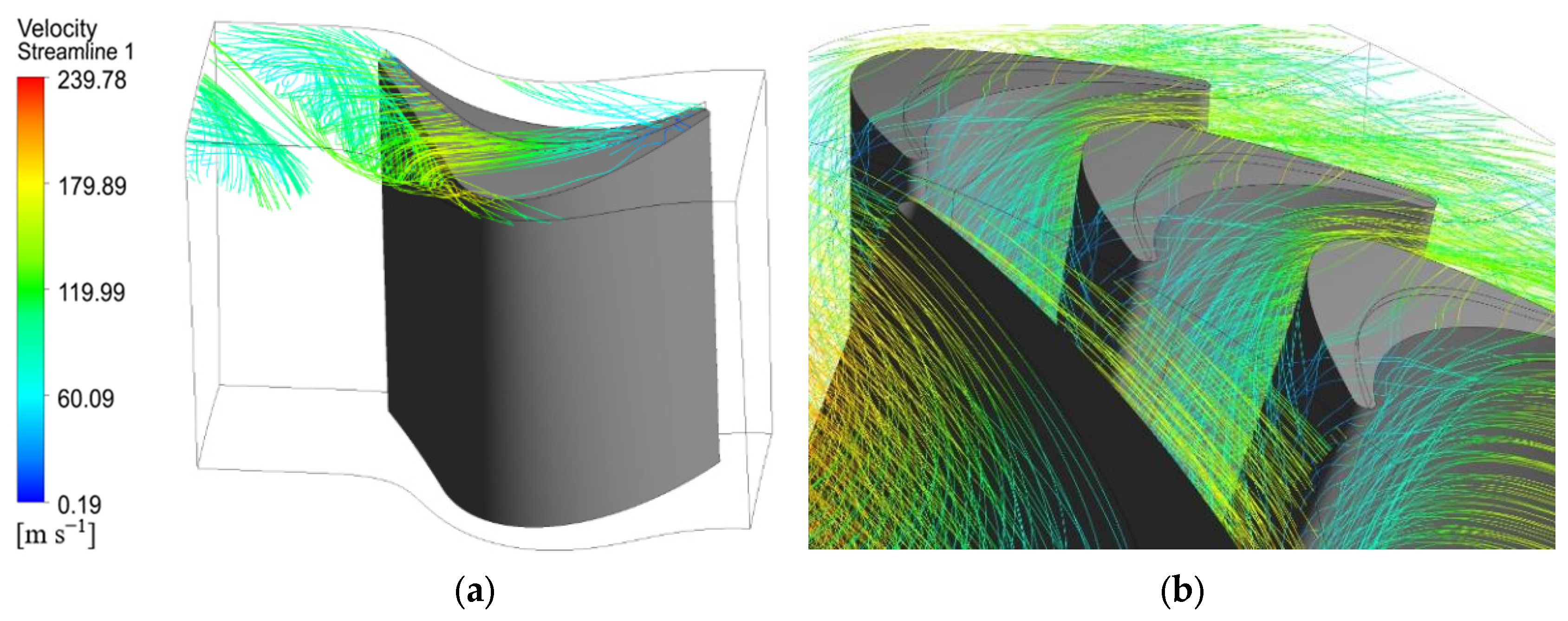

In this study, the designed turbine is modeled in 3D using AXCENT 8.8.20.0 software, including both the rotor and stator as well as the hub. The created model is imported into ANSYS Turbo-Grid 2020R1 software to generate grids for the passages of the rotor and stator. Structured grids are used, with grid refinement near the boundary layers. Due to the presence of the blade tip clearance, which leads to complex flow conditions, grid refinement is applied in the blade tip clearance region.

To ensure the accuracy of the computational results, grid independence verification is conducted. Four different grid sizes, namely 300,000, 470,000, 670,000, and 990,000, are considered, and the isentropic efficiency, Power, Mass flow are compared. It is found that the relative error is already below 0.2% for the grids with 670,000 and 990,000 cells. Following the principle of meeting the error requirement while saving computational resources, the model with 670,000 cells is chosen. Furthermore, Maximum Element Volume Ratio is 3.58, Maximum Edge Length Ratio is 921.923, and the y

+ is fixed at 1. The details of the grid independence verification can be found in

Table 7.

Figure 12 shows the grids for the passages of the rotor and stator, including the blade tip clearance.

In this study, ANSYS CFX 2020R1 software is used for numerical simulation and analysis. This software is widely employed in the field of rotating machinery and possesses strong expertise. As the working fluid, supercritical carbon dioxide remains in a subcritical state far from the critical point inside the turbine. Therefore, the “CO2 RK” substance from the CFX database is selected to meet the requirements for numerical simulation.

The internal flow within the turbine is complex, involving vortices, flow separation, and even backflow. Hence, the k-ω SST turbulence model is chosen, as it provides more accurate predictions for adverse pressure gradient flows. Regarding boundary conditions, the stage mixing-plane method is used for information exchange at the interface between the rotor and stator components. The inlet boundary condition includes total pressure and total temperature, while the outlet boundary condition is static pressure. The solid surfaces are set as adiabatic walls with no-slip conditions. The convergence criteria for each parameter are set to a residual value of 10−6. In addition, a single channel is used in the simulation process, and periodic boundary conditions are set for it.