Performance Modeling of Rooftop PV Systems in Arid Climate, a Case Study for Qatar: Impact of Soiling Losses and Albedo Using PVsyst and SAM

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Region

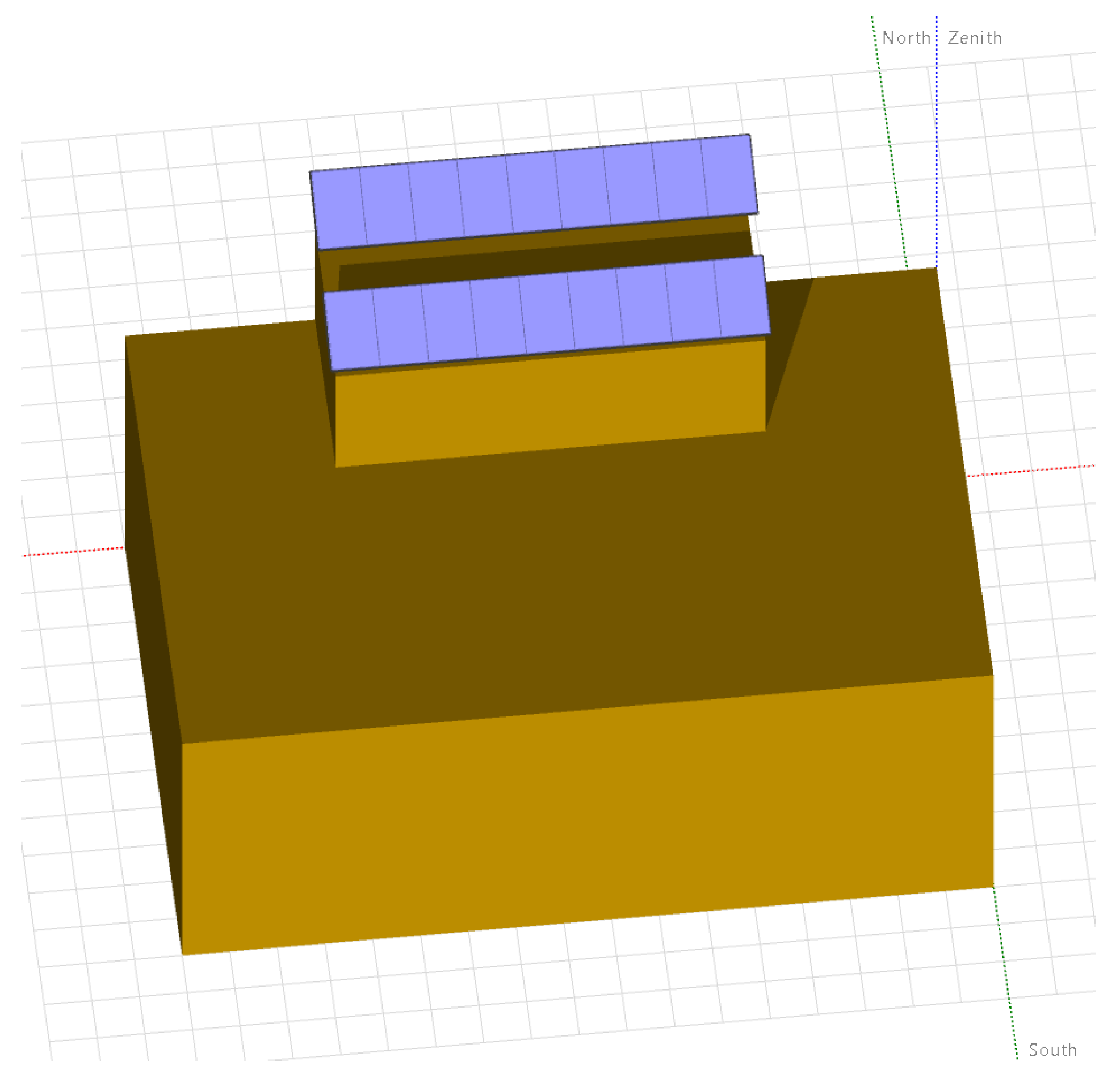

2.2. Three-Dimensional Model of the Building for Shading Analysis

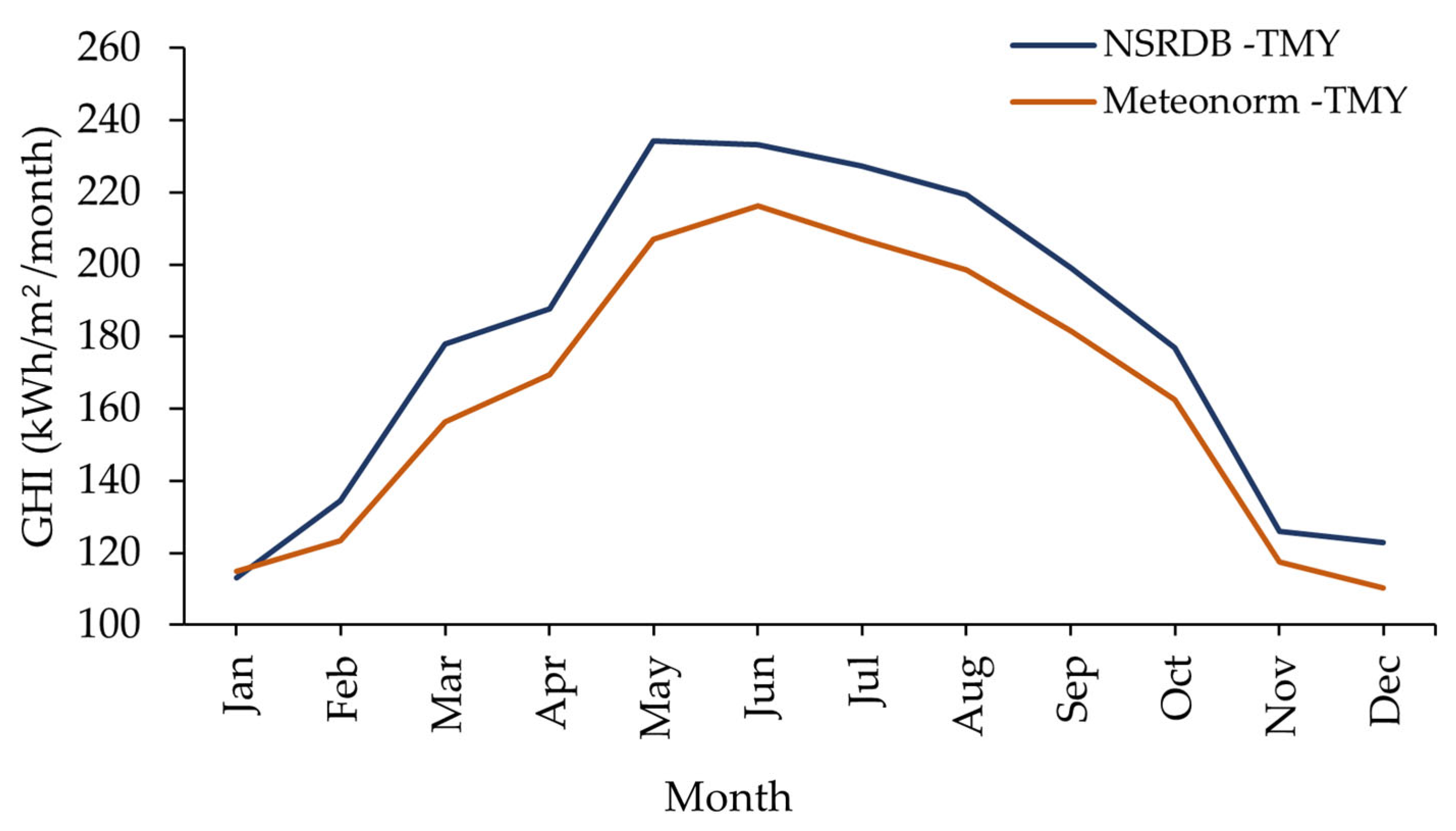

2.3. Irradiance and Weather Data Sources

2.4. System Description and Parameters

2.5. Soiling Model

2.6. In Situ Measurements

3. Results

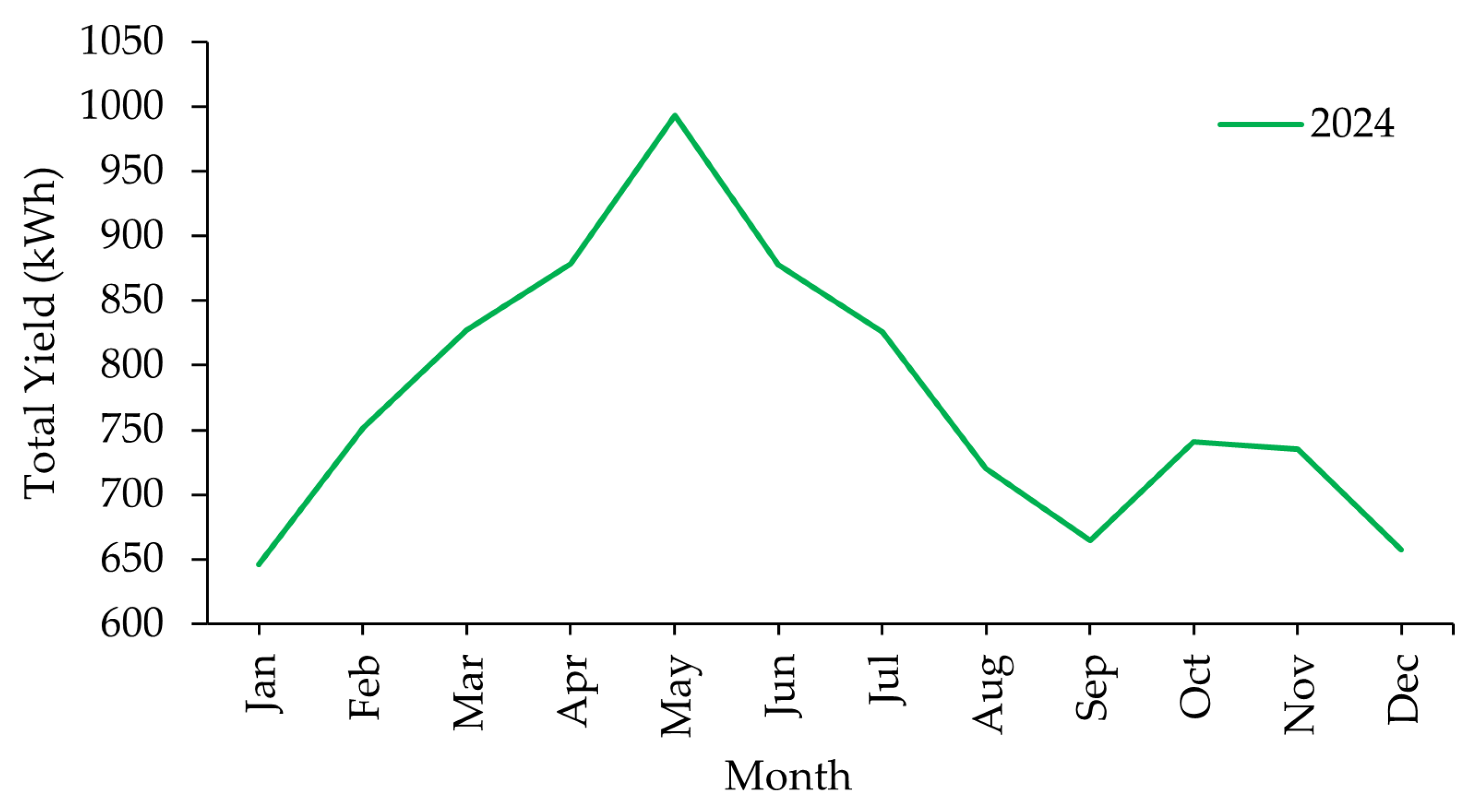

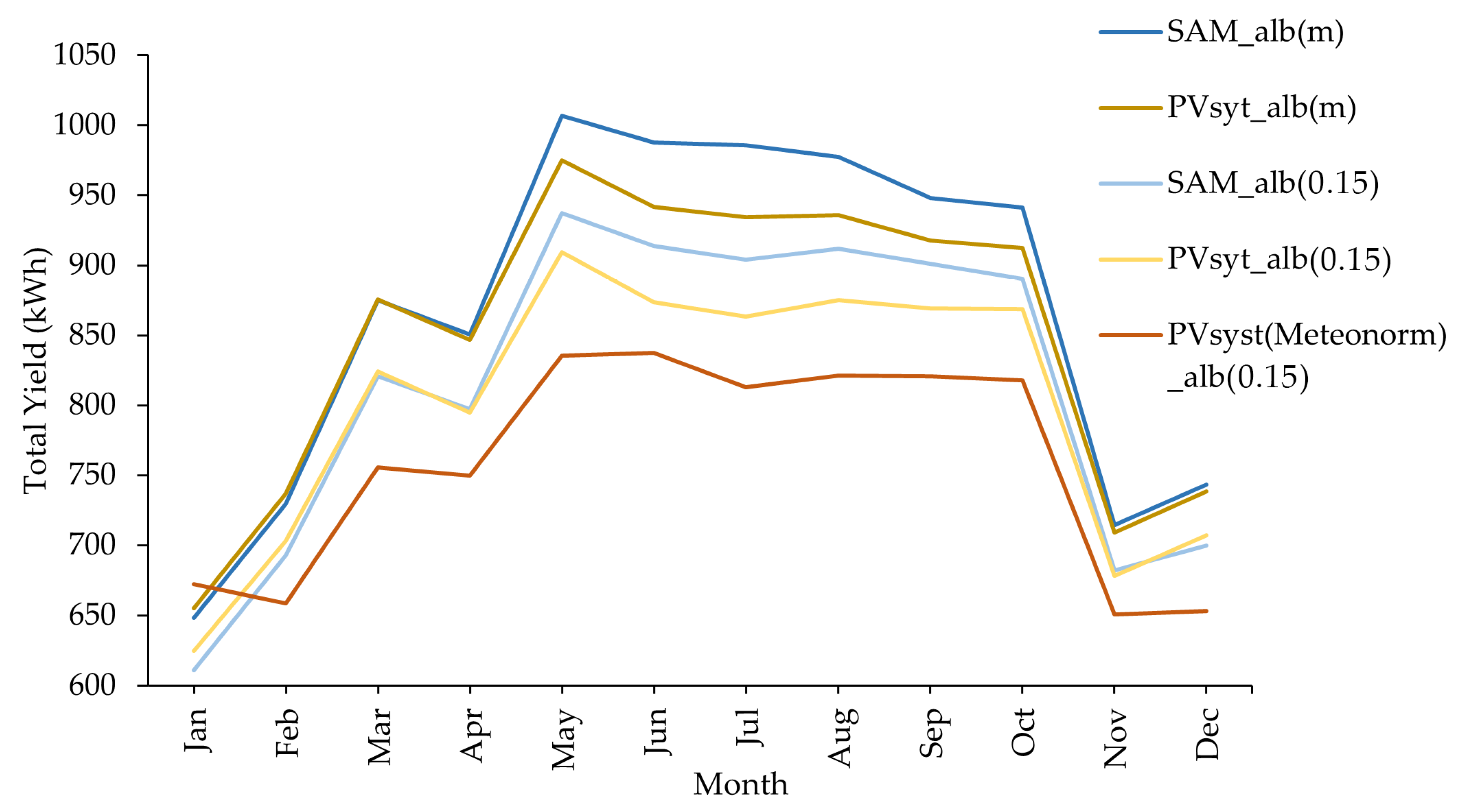

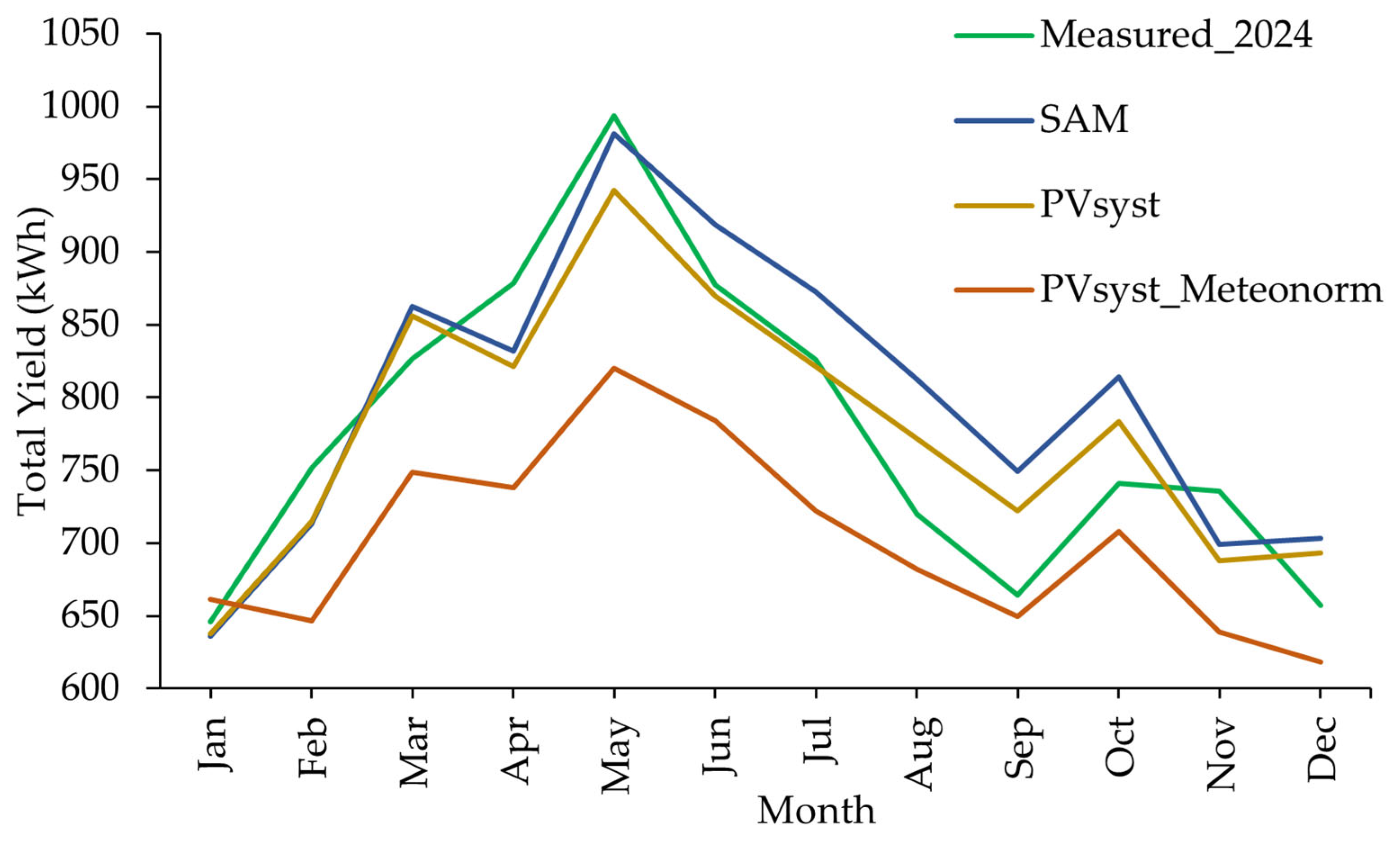

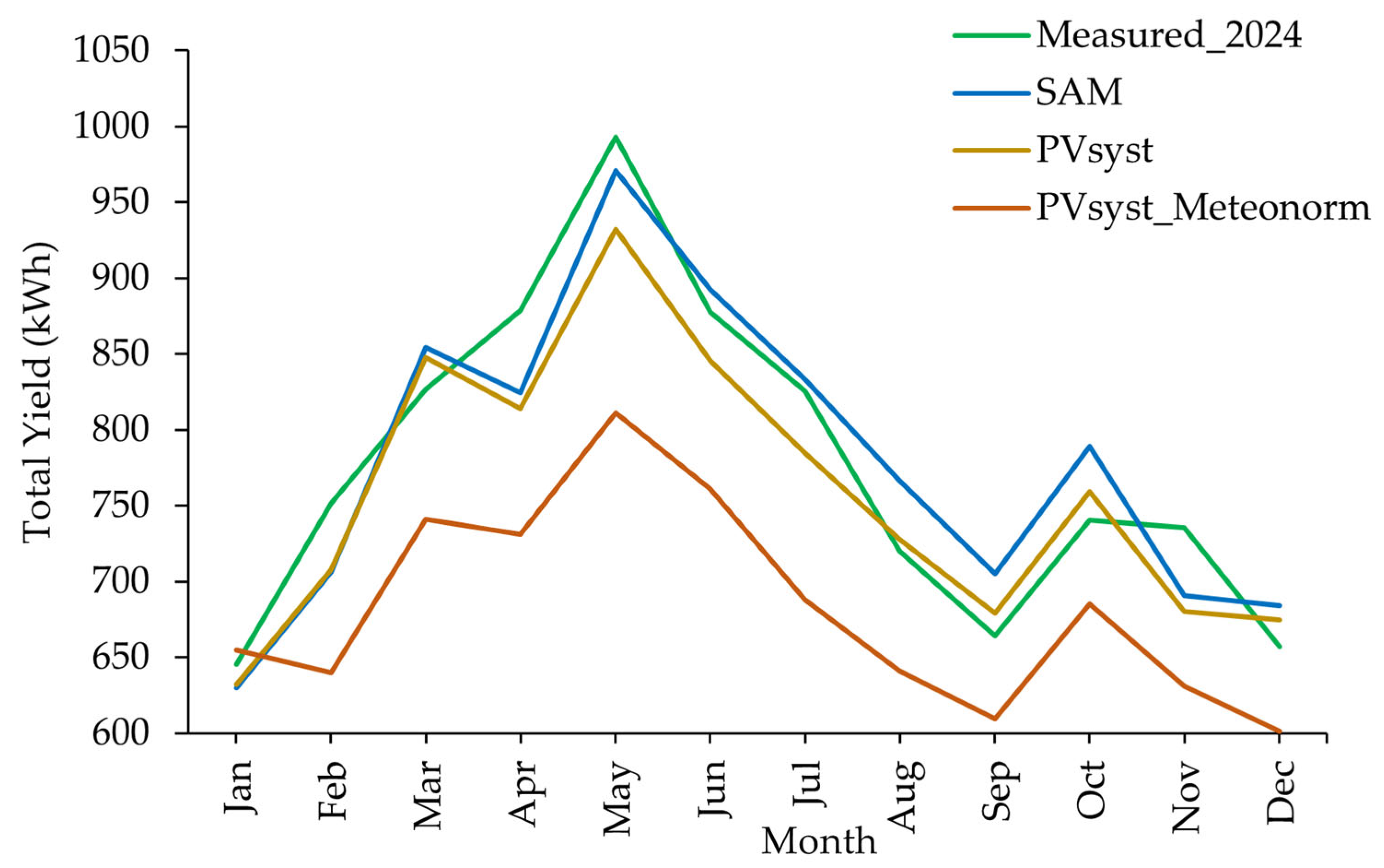

3.1. PVsyst, SAM Simulation, and In Situ Measurement Comparison and Analysis

3.1.1. Albedo Contribution

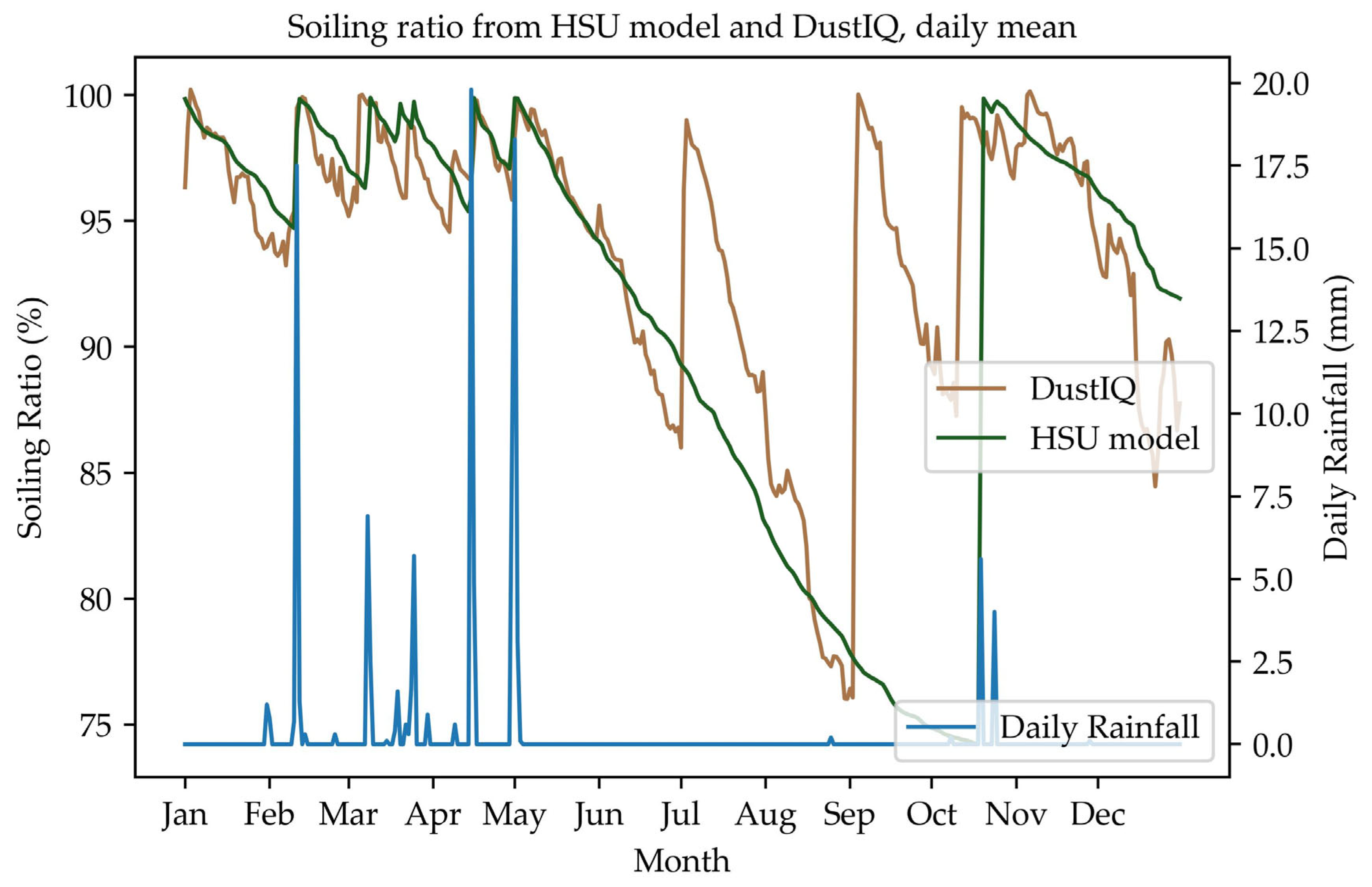

3.1.2. Soiling Losses

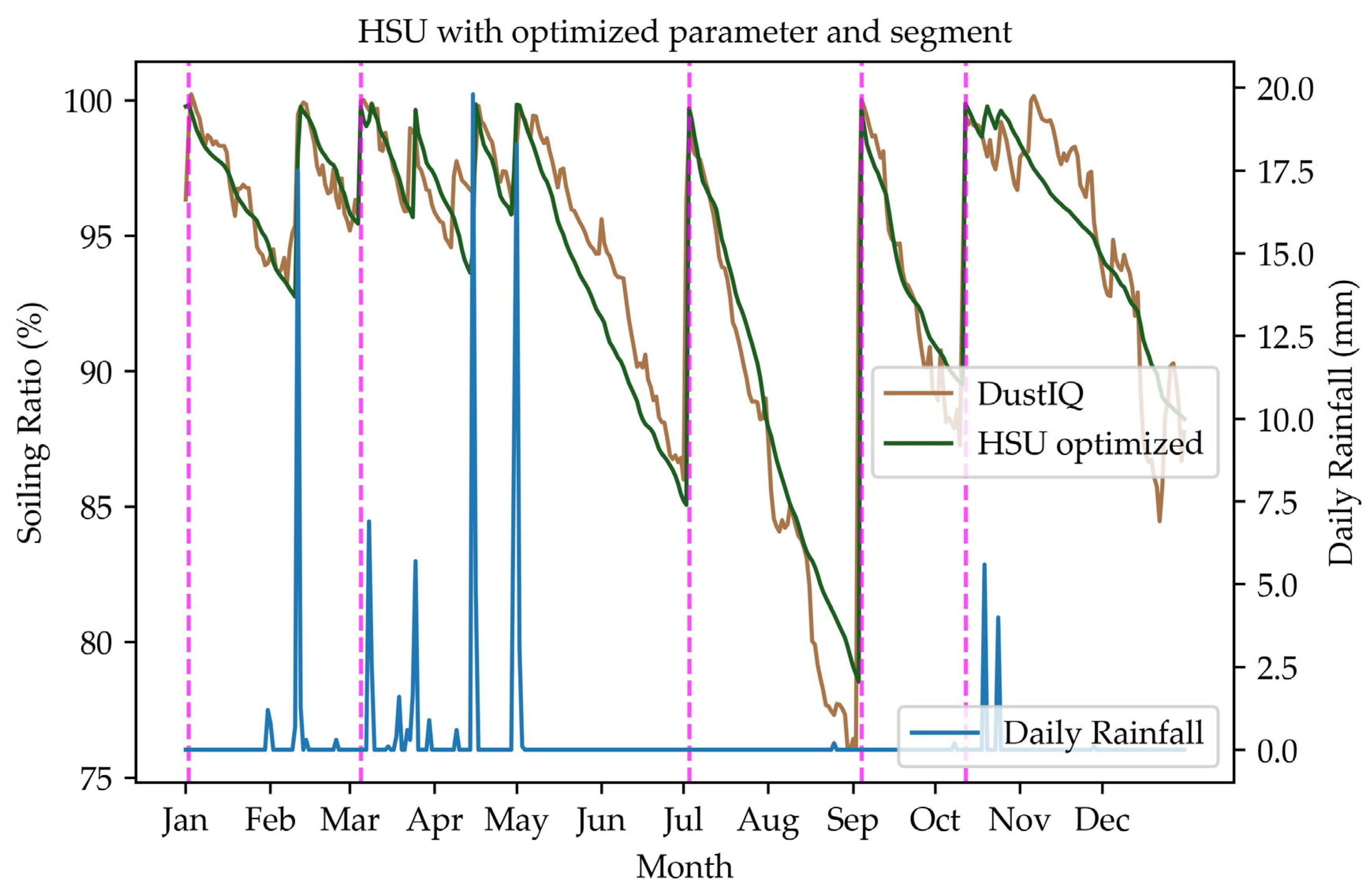

3.2. Optimization of the HSU Soiling Model

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- PVsyst|Photovoltaic Software, Design and Simulate Photovoltaic Systems. Available online: https://www.pvsyst.com/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Welcome–System Advisor Model–SAM. Available online: https://sam.nrel.gov/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Freeman, J.; Whitmore, J.; Blair, N.; Dobos, A. Validation of Multiple Tools for Flat Plate Photovoltaic Modeling Against Measured Data. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 40th Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), Denver, CO, USA, 8–13 June 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HelioScope|Commercial Solar Software. Available online: https://helioscope.aurorasolar.com/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- PV*SOL Online–A Free Tool for Solar Power (PV) Systems. Available online: https://pvsol-online.valentin-software.com/#/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Guittet, D.L.; Freeman, J.M. Validation of Photovoltaic Modeling Tool HelioScope Against Measured Data; National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Milosavljević, D.D.; Kevkić, T.S.; Jovanović, S.J. Review and Validation of Photovoltaic Solar Simulation Tools/Software Based on Case Study. Open Phys. 2022, 20, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JRC Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS)—European Commission. Available online: https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- PVWatts Calculator. Available online: https://pvwatts.nrel.gov/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Solar & Meteo Data and Analysis Software|Solargis. Available online: https://solargis.com/products (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- RETScreen—Natural Resources Canada. Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/maps-tools-publications/tools-applications/retscreen (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Home–BlueSol. Available online: https://www.bluesolpv.com/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Solar Design Software|Solarius PV|ACCA. Available online: https://www.accasoftware.com/en/solar-design-software (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- PV F-CHART: Photovoltaic Systems Analysis|F-Chart Software: Engineering Software. Available online: https://www.fchartsoftware.com/pvfchart/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Polysun|Simulation and Energy Modeling Software. Available online: https://www.velasolaris.com/en/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Photovoltaic System Simulation–Solar Pro∣Laplace System Viet Nam. Available online: https://lapsys.vn/en/products/pro/index.html (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- HOMER–Hybrid Renewable and Distributed Generation System Design Software. Available online: https://www.homerenergy.com/products/pro/index.html (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Islam, M.A.; Ali, M.M.N.; Benitez, I.B.; Sidi Habib, S.; Jamal, T.; Flah, A.; Blazek, V.; El-Bayeh, C.Z. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Photovoltaic Simulation Software: A Decision-Making Approach Using Analytic Hierarchy Process and Performance Analysis. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2025, 58, 101663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumsudeen, R.M.; Alarfaj, M.; Jeyanthy, P.A. Investigating the Effect of Shade on Rooftops Solar PV Systems in Hot Arid Regions. In Proceedings of the 2024 Third International Conference on Intelligent Techniques in Control, Optimization and Signal Processing (INCOS), Tamil Nadu, India, 14–16 March 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.S.D.; Shimray, B.A.; Meitei, S.N. Performance Analysis of a Rooftop Grid-Connected Photovoltaic System in North-Eastern India, Manipur. Energies 2025, 18, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghba, L.; Khennane, M.; Mekhilef, S.; Fezzani, A.; Borni, A. Long-Term Outdoor Performance of Grid-Connected Photovoltaic Power Plant in a Desert Climate. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 74, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, J.; Martín-Chivelet, N.; Sanz-Saiz, C.; Alonso-Montesinos, J.; López, G.; Alonso-Abella, M.; Battles, F.J.; Marzo, A.; Hanrieder, N. Modeling Soiling Losses for Rooftop PV Systems in Suburban Areas with Nearby Forest in Madrid. Renew. Energy 2021, 178, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PV Performance Modeling Collaborative (PVPMC)—Sandia National Laboratories. Available online: https://pvpmc.sandia.gov/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Stein, J.S. The Photovoltaic Performance Modeling Collaborative (PVPMC). In Proceedings of the 2012 38th IEEE Photovolta-ic Specialists Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 3–8 June 2012; pp. 3048–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theristis, M.; Riedel-Lyngskær, N.; Stein, J.S.; Deville, L.; Micheli, L.; Driesse, A.; Hobbs, W.B.; Ovaitt, S.; Daxini, R.; Barrie, D.; et al. Blind Photovoltaic Modeling Intercomparison: A Multidimensional Data Analysis and Lessons Learned. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2023, 31, 1144–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandakar, A.; Touati, A.; Touati, F.; Abdaoui, A.; Bouallegue, A. Experimental Setup to Validate the Effects of Major Environmental Parameters on the Performance of FSO Communication Link in Qatar. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamoon, A.A.; Regan, B.; Sylianteng, C.; Rahman, A.; Alkader, A.A.A. Flood Study in Qatar-Challenges and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 36th Hydrology and Water Resources Symposium (HWRS 2015), Hobart, Australia, 7–10 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Solar Resource Maps & GIS Data for 200+ Countries|Solargis. Available online: https://solargis.com/resources/free-maps-and-gis-data?locality=qatar (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Zeedan, A.; Barakeh, A.; Al-Fakhroo, K.; Touati, F.; Gonzales, A.S.P. Quantification of Pv Power and Economic Losses Due to Soiling in Qatar. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, D.S.; Lopez Garcia, J.; Figgis, B.; Jain, S.; Benito, V.B. Impact of Robotic Cleaning on the LCOE of Utility Scale PV Power Plants: A Global Assessment Based on Koppen-Geiger Climatic Zones. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 52nd Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), Seattle, WA, USA, 9–14 June 2024; pp. 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, W.; Guo, B.; Figgis, B.; Martin Pomares, L.; Aïssa, B. Multi-Year Field Assessment of Seasonal Variability of Photovoltaic Soiling and Environmental Factors in a Desert Environment. Sol. Energy 2020, 211, 1392–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghrabi, A.H.; Al-Mostafa, Z.A. Estimating Surface Albedo over Saudi Arabia. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 1607–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMA Solar Technology AG—Sunny Portal. Available online: https://www.sunnyportal.com/Templates/Start.aspx?logout=true (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Meteonorm. Available online: https://meteonorm.com/en/meteonorm-version-8 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- NSRDB. Available online: https://nsrdb.nrel.gov/data-viewer (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Soiling Loss-PVsyst Documentation. Available online: https://www.pvsyst.com/help/project-design/array-and-system-losses/soiling-loss.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Losses. Available online: https://samrepo.nrelcloud.org/help/pv_losses.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Coello, M.; Boyle, L. Simple Model for Predicting Time Series Soiling of Photovoltaic Panels. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2019, 9, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 🌤️ Free Open-Source Weather API|Open-Meteo.Com. Available online: https://open-meteo.com/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Redondo, M.; Platero, C.A.; Moset, A.; Rodríguez, F.; Donate, V. Review and Comparison of Methods for Soiling Modeling in Large Grid-Connected PV Plants. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albedo-PVsyst Documentation. Available online: https://www.pvsyst.com/help/physical-models-used/irradiation-models/albedo.html (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Lopez-Lorente, J.; Neubert, A.; Hamer, M. Uncertainty Considerations in Bifacial Photovoltaic Systems with High Albedo Seasonality. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 50th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), San Juan, PR, USA, 11–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golroodbari, S.; van Sark, W. On the Effect of Dynamic Albedo on Performance Modelling of Offshore Floating Photovoltaic Systems. Sol. Energy Adv. 2022, 2, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DustIQ for PV Soiling Monitoring-Kipp & Zonen. Available online: https://www.kippzonen.com/Product/419/DustIQ-Soiling-Monitoring-System (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential Evolution—A Simple and Efficient Heuristic for Global Optimization over Continuous Spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, M.; Rashidi, S.; Waqas, A. Modeling of Soiling Losses in Solar Energy Systems. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Yousif, M.; Rashid, Z.; Muhammad, A.; Altaf, M.; Mustafa, A. Effect of Dust Accumulation on the Performance of Photovoltaic Modules for Different Climate Regions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e23069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Module | SolarWorld SunModule Bisun SW 280 Duo |

| Rated maximum power (per module) | 280 W |

| Configuration | 18 modules in series, arranged in 2 rows |

| Inverter | SMA Sunny Tripower 6000TL-20 |

| Rated inverter power | 6 kW |

| Parameter | Default Value | Optimized Value (OTF Calibration) |

|---|---|---|

| Rain cleaning threshold | 1.00 | 1.17 |

| PM2.5 deposition velocity | 0.0009 | 0.004 |

| PM10 deposition velocity | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soiling loss (%), default parameter | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 8.2 | 13.5 | 19.7 | 23.8 | 15.4 | 2.4 | 6 |

| Soiling loss (%), optimized parameter | 3.1 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 11.3 | 18.1 | 25.1 | 29.0 | 18.4 | 3.7 | 8.8 |

| Case | PVsyst_Meteonorm | PVsyst (NSRDB) | SAM (NSRDB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default albedo and default soiling losses | 12.08 | 13.29 | 13.99 |

| Monthly soiling losses and monthly albedo (non-optimized) | 12.88 | 5.21 | 6.83 |

| Monthly albedo and optimized monthly soiling losses (HSU) | 13.60 | 4.86 | 4.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jain, S.; Abdelrahim, M.; Abdallah, A.A.; Pillai, D.S.; Bayhan, S. Performance Modeling of Rooftop PV Systems in Arid Climate, a Case Study for Qatar: Impact of Soiling Losses and Albedo Using PVsyst and SAM. Energies 2025, 18, 5876. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225876

Jain S, Abdelrahim M, Abdallah AA, Pillai DS, Bayhan S. Performance Modeling of Rooftop PV Systems in Arid Climate, a Case Study for Qatar: Impact of Soiling Losses and Albedo Using PVsyst and SAM. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5876. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225876

Chicago/Turabian StyleJain, Sachin, Mohamed Abdelrahim, Amir A. Abdallah, Dhanup S. Pillai, and Sertac Bayhan. 2025. "Performance Modeling of Rooftop PV Systems in Arid Climate, a Case Study for Qatar: Impact of Soiling Losses and Albedo Using PVsyst and SAM" Energies 18, no. 22: 5876. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225876

APA StyleJain, S., Abdelrahim, M., Abdallah, A. A., Pillai, D. S., & Bayhan, S. (2025). Performance Modeling of Rooftop PV Systems in Arid Climate, a Case Study for Qatar: Impact of Soiling Losses and Albedo Using PVsyst and SAM. Energies, 18(22), 5876. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225876