A Deep Neural Network-Based Approach for Optimizing Ammonia–Hydrogen Combustion Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

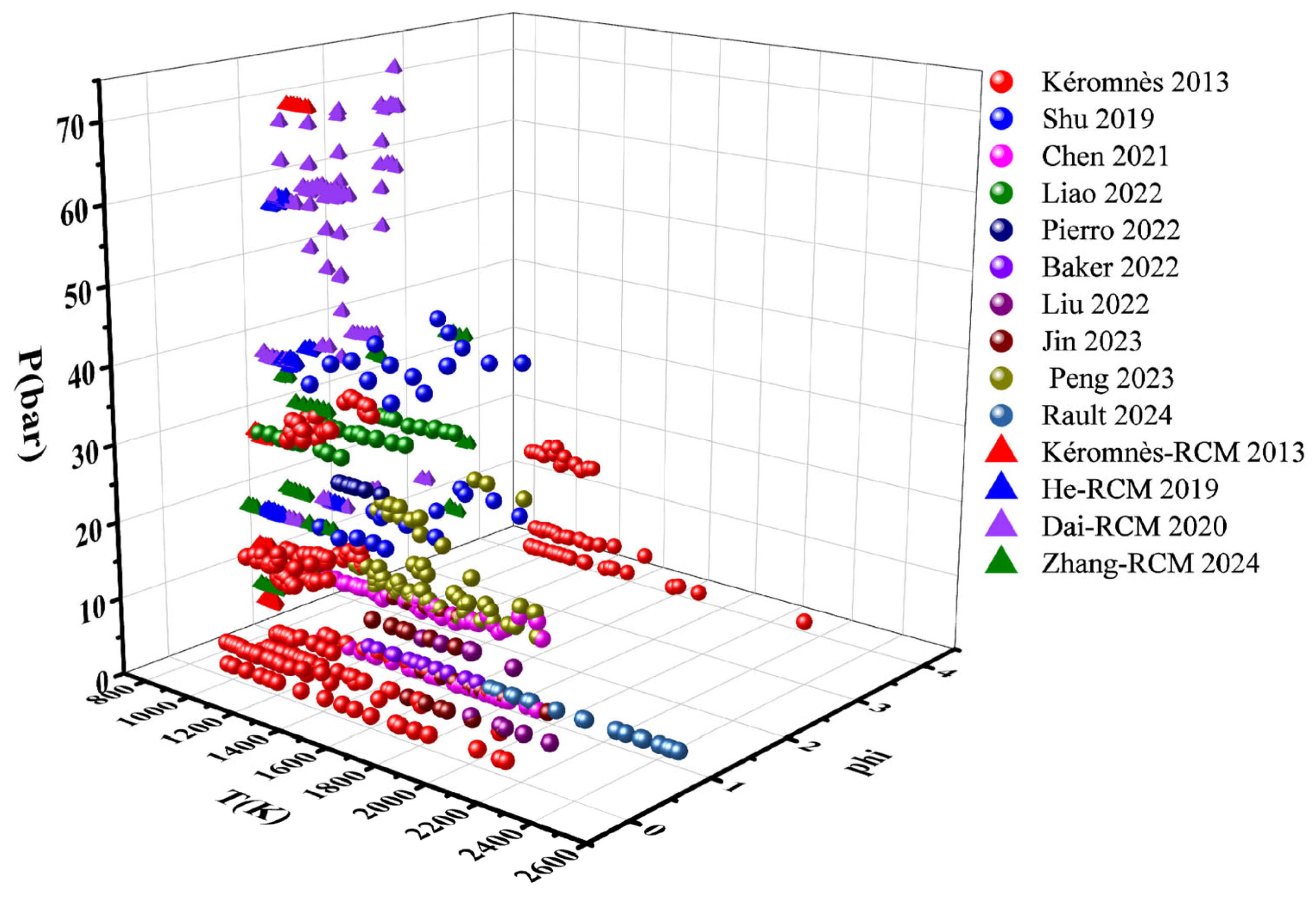

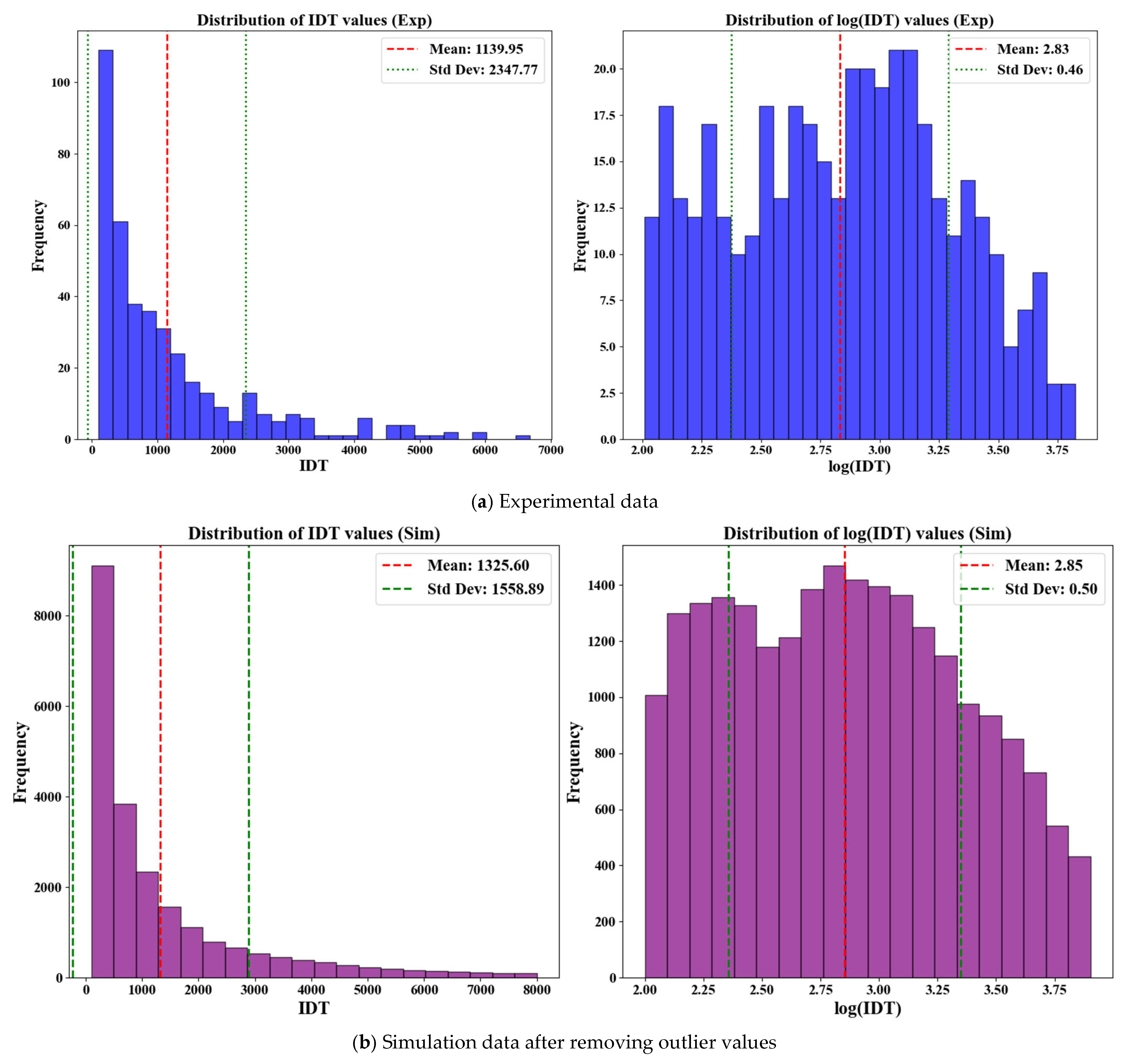

2.1. Data Preparation

2.2. Machine Learning Methods

2.2.1. Comparative Methods

2.2.2. Surrogate Model

2.3. Evaluation of Models

3. Results

3.1. Surrogate Model Optimization

3.1.1. The Predictive Capability of Neurons Within the Hidden Layers of MLP

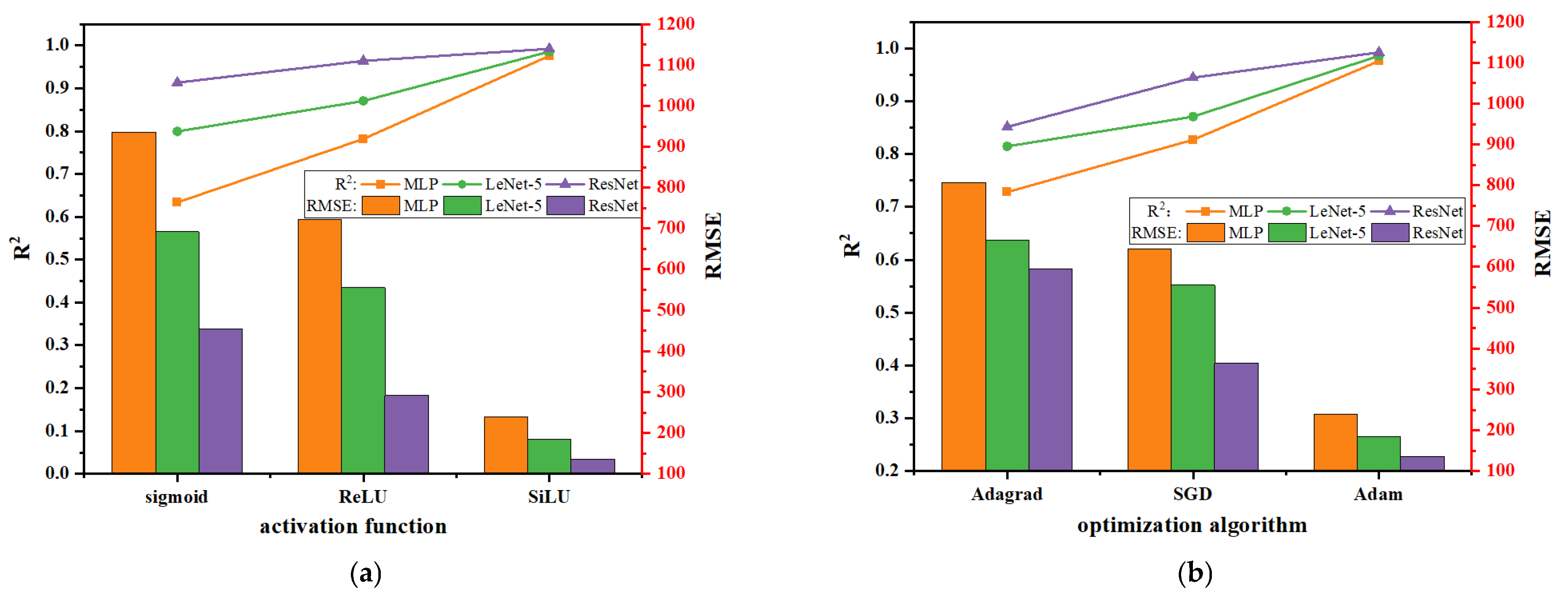

3.1.2. Optimization of DNN

3.1.3. Comparison Among Diverse Machine Learning Models

3.1.4. Optimization in Surrogate Model

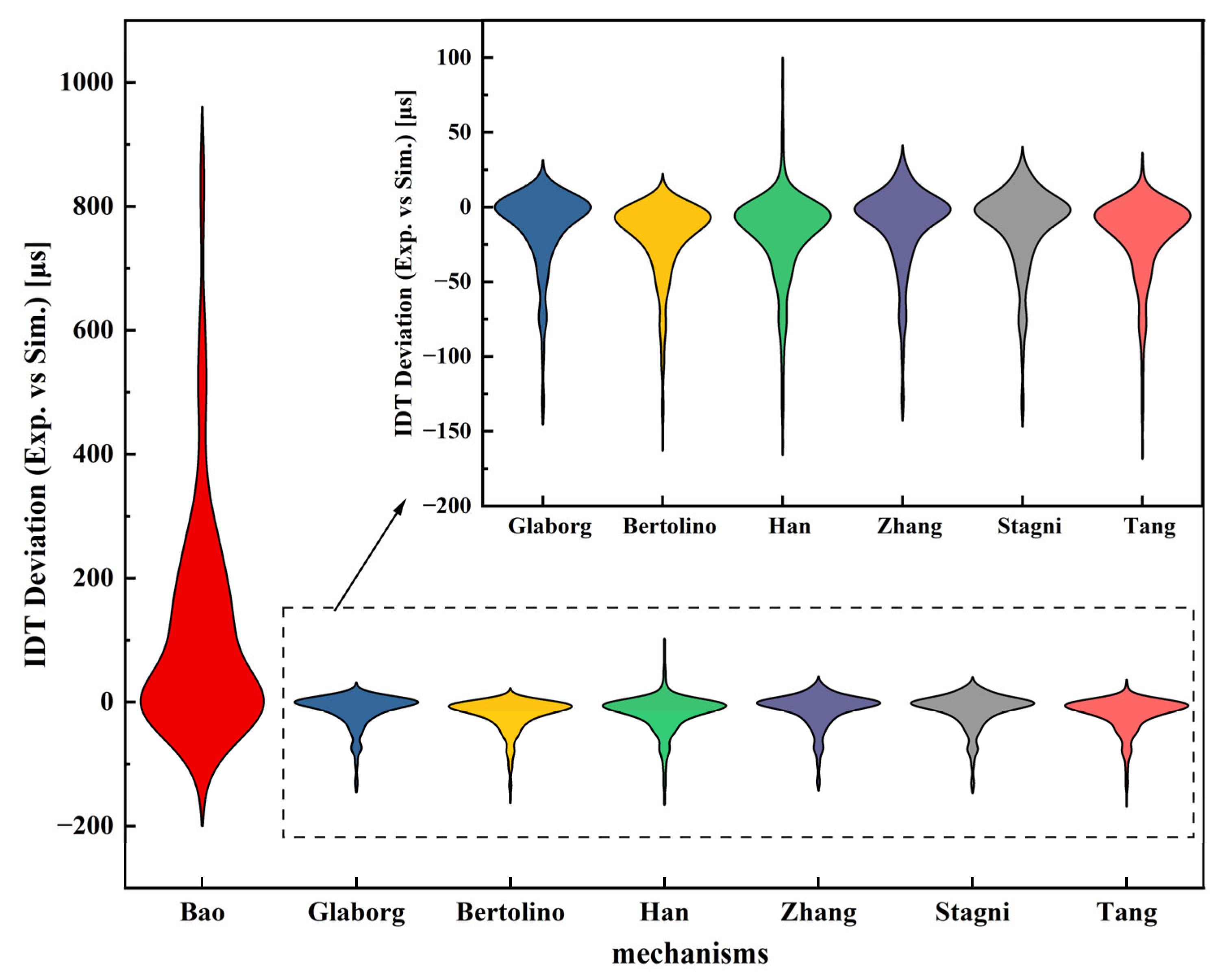

3.2. Comparison of Different Mechanisms Performance

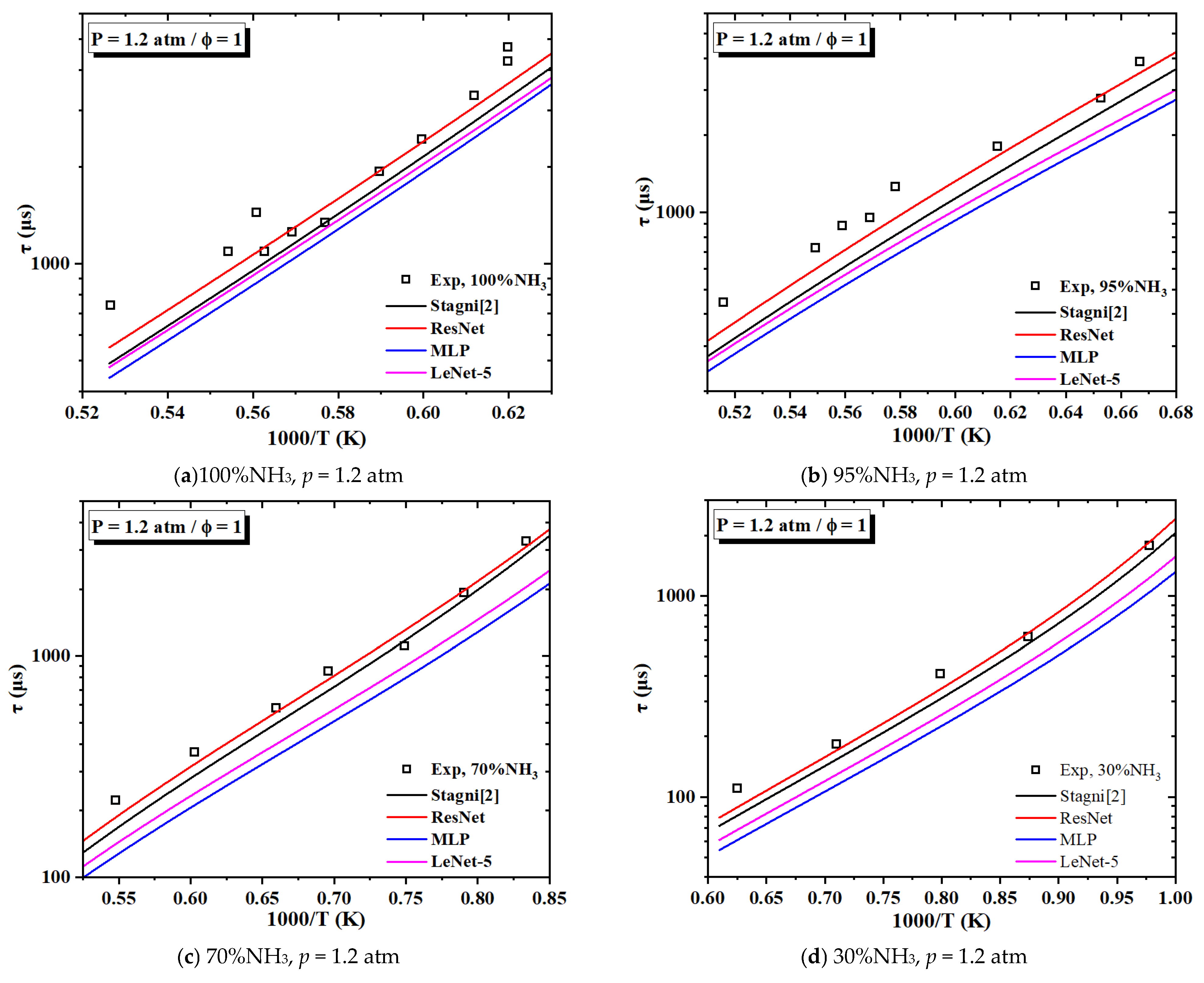

3.2.1. Validation on IDTs

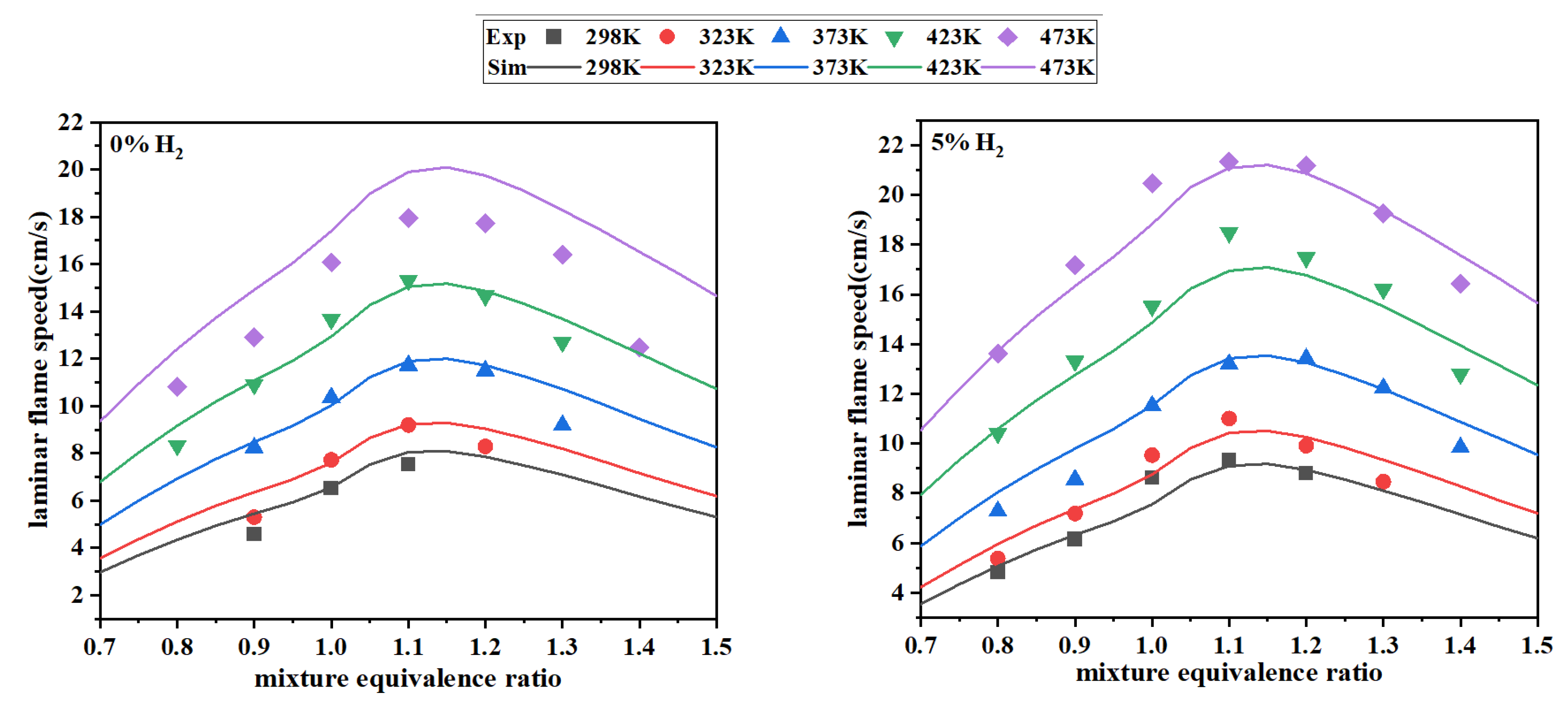

3.2.2. Validation on LFS

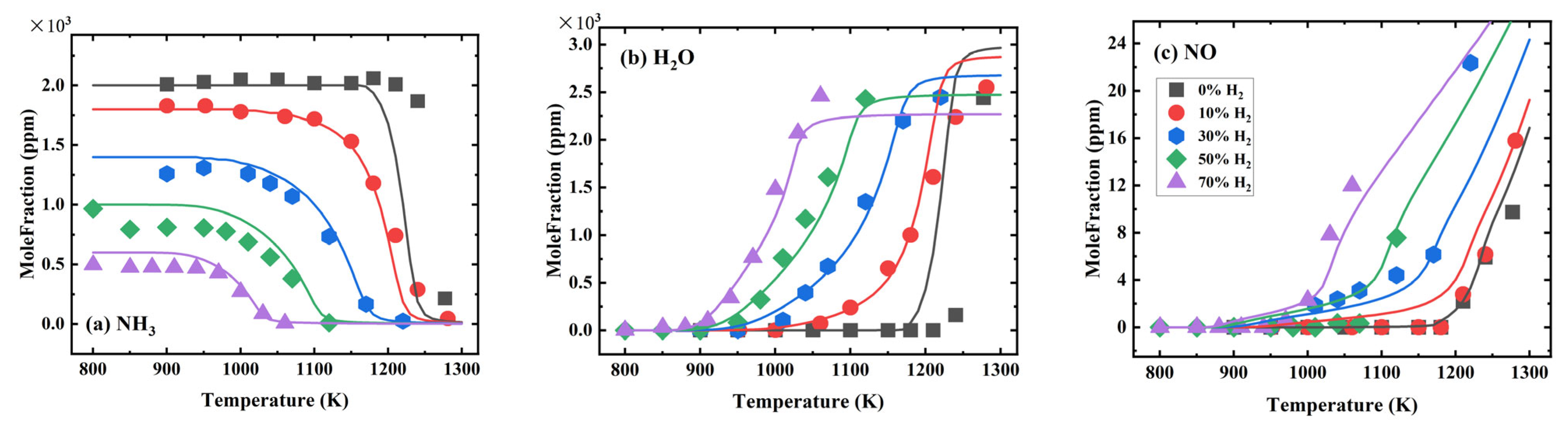

3.2.3. Validation of Species Mole Fractions

4. Conclusions

- MLP performed better with seven layers and 1500 epochs. Following the optimization of its activation function and optimization algorithms on the test set—comprising the IDTs of ammonia–hydrogen under varying operating pressures, temperatures, and equivalence ratios—the MLP model delivered improved performance with an R2 of 0.9807 and RMSE of 239.

- LeNet-5 and ResNet markedly enhanced the prediction accuracy of the DNN model, thereby achieving an R2 of 0.9858, and 0.9923 and RMSE of 184, and 136, respectively. ResNet was used as a part of the surrogate model to further optimize the mechanism parameters.

- The optimized mechanism outperforms the original mechanism when tested with experimental data. For IDT simulations, mech_ResNet exhibits smaller deviations. For LFS simulations, mech_ResNet improves the prediction accuracy by approximately 36.6% compared to the original mechanism.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DNN | Deep neural network |

| MLP | Multi-layer perceptron |

| GLR | generalized linear regression |

| SVM | support vector machine |

| RF | random forest |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| IDT | ignition delay time |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| LFS | laminar flame speed |

References

- Erfani, N.; Baharudin, L.; Watson, M. Recent Advances and Intensifications in Haber-Bosch Ammonia Synthesis Process. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2024, 204, 109962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, T.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Li, R.; Xu, C. Thermodynamic Comparison of Cryogenic Air Separation Units with External and Internal Compression of Oxygen Designed for the Coal-Fueled Allam Cycle. Energy 2025, 333, 137325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashida, Y.; Arashiba, K.; Nakajima, K.; Nishibayashi, Y. Molybdenum-Catalysed Ammonia Production with Samarium Diiodide and Alcohols or Water. Nature 2019, 568, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yandulov, D.V.; Schrock, R.R. Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia at a Single Molybdenum Center. Science 2003, 301, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.M.O.; Economou, I.G.; Bicer, Y. Navigating Ammonia Production Routes: Life Cycle Assessment Insights for a Sustainable Future. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 49, 100947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, W.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Min, H.; Li, F.; Yin, Y.; Li, Z. Numerical Simulation of Ammonia-Hydrogen Engine Using Low-Pressure Direct Injection (LP-DI); No. 2024–1–2118; SAE International: Detroit, MI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Huang, H.; Kobayashi, N.; He, Z.; Nagai, Y. Study on Using Hydrogen and Ammonia as Fuels: Combustion Characteristics and NO xFormation: Hydrogen and Ammonia as Fuels. Int. J. Energy Res. 2014, 38, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Valera-Medina, A.; Bowen, P.J. Modeling Combustion of Ammonia/Hydrogen Fuel Blends under Gas Turbine Conditions. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 8631–8642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Howard, M.; Valera-Medina, A.; Dooley, S.; Bowen, P.J. Study on Reduced Chemical Mechanisms of Ammonia/Methane Combustion under Gas Turbine Conditions. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 8701–8710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zou, C.; Song, Y.; Cheng, S.; Lin, Q. Experimental and Numerical Study of Laminar Flame Speeds of CH4/NH3 Mixtures under Oxy-Fuel Combustion. Energy 2019, 175, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, Z. Investigation on Flame Propagation and End-Gas Auto-Ignition of Ammonia/Hydrogen in a Full-Field-Visualized Rapid Compression Machine. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, Q.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Effect of Injection and Ignition Strategy on an Ammonia Direct Injection–Hydrogen Jet Ignition (ADI-HJI) Engine. Energy 2024, 306, 132502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, Q.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Z. Numerical Investigation of Multiple Hydrogen Injection in a Jet Ignition Ammonia-Hydrogen Engine. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 77, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qi, Y.; Sun, Q.; Lin, Z.; Xu, X. Ammonia Combustion Using Hydrogen Jet Ignition (AHJI) in Internal Combustion Engines. Energy 2024, 291, 130407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.A.; Smooke, M.D.; Green, R.M.; Kee, R.J. Kinetic Modeling of the Oxidation of Ammonia in Flames. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1983, 34, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenimore, C.P.; Jones, G.W. Oxidation of Ammonia in Flames. J. Phys. Chem. 1961, 65, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, R.K.; Hardy, J.E. Discovery and Development of the Thermal DeNOx Process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 1986, 25, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstedt, R.P.; Lockwood, F.C.; Selim, M.A. Detailed Kinetic Modelling of Chemistry and Temperature Effects on Ammonia Oxidation. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1994, 99, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstedt, R.P.; Lockwood, F.C.; Selim, M.A. A Detailed Kinetic Study of Ammonia Oxidation. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1995, 108, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otomo, J.; Koshi, M.; Mitsumori, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Yamada, K. Chemical Kinetic Modeling of Ammonia Oxidation with Improved Reaction Mechanism for Ammonia/Air and Ammonia/Hydrogen/Air Combustion. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 3004–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Hashemi, H.; Christensen, J.M.; Zou, C.; Marshall, P.; Glarborg, P. Ammonia Oxidation at High Pressure and Intermediate Temperatures. Fuel 2016, 181, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.B.; Rahman, R.K.; Pierro, M.; Higgs, J.; Urso, J.; Kinney, C.; Vasu, S. Experimental Ignition Delay Time Measurements and Chemical Kinetics Modeling of Hydrogen/Ammonia/Natural Gas Fuels. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2023, 145, 41002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, R.; Wang, K.; Bowman, C.T.; Hanson, R.K.; Davidson, D.F.; Brezinsky, K.; Egolfopoulos, F.N. A Physics-Based Approach to Modeling Real-Fuel Combustion Chemistry-I. Evidence from Experiments, and Thermodynamic, Chemical Kinetic and Statistical Considerations. Combust. Flame 2018, 193, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggese, C.; Wan, K.; Xu, R.; Tao, Y.; Bowman, C.T.; Park, J.-W.; Lu, T.; Wang, H. A Physics-Based Approach to Modeling Real-Fuel Combustion Chemistry–V. NO Formation from a Typical Jet A. Combust. Flame 2020, 212, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, K.; Shao, J.; Johnson, S.E.; Movaghar, A.; Han, X.; Park, J.-W.; Lu, T.; Brezinsky, K.; et al. A Physics-Based Approach to Modeling Real-Fuel Combustion Chemistry–III. Reaction Kinetic Model of JP10. Combust. Flame 2018, 198, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wang, K.; Banerjee, S.; Shao, J.; Parise, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; Movaghar, A.; Lee, D.J.; Zhao, R.; et al. A Physics-Based Approach to Modeling Real-Fuel Combustion Chemistry–II. Reaction Kinetic Models of Jet and Rocket Fuels. Combust. Flame 2018, 193, 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xu, R.; Parise, T.; Shao, J.; Movaghar, A.; Lee, D.J.; Park, J.-W.; Gao, Y.; Lu, T.; Egolfopoulos, F.N.; et al. A Physics-Based Approach to Modeling Real-Fuel Combustion Chemistry–IV. HyChem Modeling of Combustion Kinetics of a Bio-Derived Jet Fuel and Its Blends with a Conventional Jet A. Combust. Flame 2018, 198, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buras, Z.J.; Safta, C.; Zádor, J.; Sheps, L. Simulated Production of OH, HO2, CH2O, and CO2 during Dilute Fuel Oxidation Can Predict 1st-Stage Ignition Delays. Combust. Flame 2020, 216, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X. The Reduced Mechanism of Ammonia/Hydrogen Mixture for Detonation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 139, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Xiao, B.; You, J.; Zhan, H.; Hu, E.; Huang, Z. Experimental and Kinetic Modeling Study on Propane Enhancing the Laminar Flame Speeds of Ammonia. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 247, 107779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Freitas, R.S.M.; Jiang, X. Neural Network Potential-Based Molecular Investigation of Thermal Decomposition Mechanisms of Ethylene and Ammonia. Energy AI 2024, 18, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Shen, D.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, M.; Wu, X.; Zhu, W.; Long, W.; Bi, M. A Combustion Mechanism Simplification and Optimization Method Using Two-Stage Deep Neural Networks for Multiple Fuels. Energy 2025, 335, 137943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Song, Y.; Ji, W.; Wei, H. Machine Learning for Combustion. Energy AI 2022, 7, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliramezani, M.; Koch, C.R.; Shahbakhti, M. Modeling, Diagnostics, Optimization, and Control of Internal Combustion Engines via Modern Machine Learning Techniques: A Review and Future Directions. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 88, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, C.E.; De Freitas, R.D.S.M.; Okafor, E.C.; Shahbakhti, M.; Jiang, X.; Paykani, A. Machine Learning Applications for Predicting Fuel Ignition and Flame Properties: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, acs.energyfuels.5c02343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahpouri, S.; Norouzi, A.; Hayduk, C.; Fandakov, A.; Rezaei, R.; Koch, C.R.; Shahbakhti, M. Laminar Flame Speed Modeling for Low Carbon Fuels Using Methods of Machine Learning. Fuel 2023, 333, 126187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Wang, B.; Xia, Y.; Liang, Z. A Deep Learning Model for Predicting the Laminar Burning Velocity of NH3/H2/Air. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tan, F.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y. Combining Genetic Algorithm and Deep Learning to Optimize a Chemical Kinetic Mechanism of Ammonia under High Pressure. Fuel 2024, 360, 130508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulga, L.; Bianchi, G.M.; Falfari, S.; Forte, C. A Machine Learning Methodology for Improving the Accuracy of Laminar Flame Simulations with Reduced Chemical Kinetics Mechanisms. Combust. Flame 2020, 216, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Im, S. Development of a Global Mechanism for Ammonia Combustion Assisted by Machine Learning. J. Korean Soc. Combust. 2024, 29, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Gersen, S.; Glarborg, P.; Levinsky, H.; Mokhov, A. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of the Autoignition Behavior of NH3 and NH3/H2 Mixtures at High Pressure. Combust. Flame 2020, 215, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Chu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, B. An Experimental and Modeling Study on Auto-Ignition of Ammonia in an RCM with N2O and H2 Addition. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 4377–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Shu, B.; Nascimento, D.; Moshammer, K.; Costa, M.; Fernandes, R.X. Auto-Ignition Kinetics of Ammonia and Ammonia/Hydrogen Mixtures at Intermediate Temperatures and High Pressures. Combust. Flame 2019, 206, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kéromnès, A.; Metcalfe, W.K.; Heufer, K.A.; Donohoe, N.; Das, A.K.; Sung, C.-J.; Herzler, J.; Naumann, C.; Griebel, P.; Mathieu, O.; et al. An Experimental and Detailed Chemical Kinetic Modeling Study of Hydrogen and Syngas Mixture Oxidation at Elevated Pressures. Combust. Flame 2013, 160, 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, B.; Vallabhuni, S.K.; He, X.; Issayev, G.; Moshammer, K.; Farooq, A.; Fernandes, R.X. A Shock Tube and Modeling Study on the Autoignition Properties of Ammonia at Intermediate Temperatures. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2019, 37, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, X.; Qin, X.; Huang, Z. Effect of Hydrogen Blending on the High Temperature Auto-Ignition of Ammonia at Elevated Pressure. Fuel 2021, 287, 119563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z.; Chu, X. Effect of Dimethyl Ether on Ignition Characteristics of Ammonia and Chemical Kinetics. Fuel 2023, 343, 127885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Ranjan, D.; Sun, W. A Shock Tube Study of Fuel Concentration Effect on High-Pressure Autoignition Delay of Ammonia. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 16, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zou, C.; Luo, J. Experimental and Modeling Study on the Ignition Delay Times of Ammonia/Methane Mixtures at High Dilution and High Temperatures. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 4399–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, T.M.; Clees, S.; Figueroa-Labastida, M.; Barnes, S.C.; Ferris, A.M.; Obrecht, N.; Callu, C.; Hanson, R.K. Multi-Speciation and Ignition Delay Time Measurements of Ammonia Oxidation behind Reflected Shock Waves. Combust. Flame 2024, 260, 113260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhuillier, C.; Brequigny, P.; Lamoureux, N.; Contino, F.; Mounaïm-Rousselle, C. Experimental Investigation on Laminar Burning Velocities of Ammonia/Hydrogen/Air Mixtures at Elevated Temperatures. Fuel 2020, 263, 116653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, A.; Fürst, M.; Stagni, A.; Frassoldati, A.; Pelucchi, M.; Cavallotti, C.; Faravelli, T.; Parente, A. An Evolutionary, Data-Driven Approach for Mechanism Optimization: Theory and Application to Ammonia Combustion. Combust. Flame 2021, 229, 111366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Lubrano Lavadera, M.; Konnov, A.A. An Experimental and Kinetic Modeling Study on the Laminar Burning Velocity of NH3+N2O+air Flames. Combust. Flame 2021, 228, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Du, H.; Chai, W.S.; Nie, D.; Zhou, L. Numerical Investigation and Optimization on Laminar Burning Velocity of Ammonia-Based Fuels Based on GRI3.0 Mechanism. Fuel 2022, 318, 123681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Xu, Q.; Pan, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Wei, H.; Shu, G. An Experimental and Modeling Study of Ammonia Oxidation in a Jet Stirred Reactor. Combust. Flame 2022, 240, 112007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glarborg, P. The NH3/NO2/O2 System: Constraining Key Steps in Ammonia Ignition and N2O Formation. Combust. Flame 2023, 257, 112311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagni, A.; Cavallotti, C. H-Abstractions by O2, NO2, NH2, and HO2 from H2NO: Theoretical Study and Implications for Ammonia Low-Temperature Kinetics. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, Y.; Chu, Z.; Yang, B.; Wang, Z. A Study on Measuring Ammonia-Hydrogen IDTs and Constructing an Ammonia-Hydrogen Combustion Mechanism at Engine-Relevant Thermodynamic and Fuel Concentration Conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 786–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Davidson, D.F.; Barbour, E.A.; Hanson, R.K. A New Shock Tube Study of the H+O2→OH+O Reaction Rate Using Tunable Diode Laser Absorption of H2O near 2.5μm. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2011, 33, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.X.; Luther, K.; Troe, J.; Ushakov, V.G. Experimental and Modelling Study of the Recombination Reaction H + O2 (+M) → HO2 (+M) between 300 and 900 K, 1.5 and 950 Bar, and in the Bath Gases M = He, Ar, and N2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagni, A.; Cavallotti, C.; Arunthanayothin, S.; Song, Y.; Herbinet, O.; Battin-Leclerc, F.; Faravelli, T. An Experimental, Theoretical and Kinetic-Modeling Study of the Gas-Phase Oxidation of Ammonia. React. Chem. Eng. 2020, 5, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippenstein, S.J.; Mulvihill, C.R.; Glarborg, P. Theoretical Kinetics Predictions for Reactions on the NH2 O Potential Energy Surface. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 8650–8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glarborg, P.; Hashemi, H.; Cheskis, S.; Jasper, A.W. On the Rate Constant for NH2 +HO2 and Third-Body Collision Efficiencies for NH2 +H(+M) and NH2 +NH2 (+M). J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippenstein, S.J.; Harding, L.B.; Ruscic, B.; Sivaramakrishnan, R.; Srinivasan, N.K.; Su, M.-C.; Michael, J.V. Thermal Decomposition of NH2 OH and Subsequent Reactions: Ab Initio Transition State Theory and Reflected Shock Tube Experiments. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 10241–10259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glarborg, P.; Miller, J.A.; Ruscic, B.; Klippenstein, S.J. Modeling Nitrogen Chemistry in Combustion. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 67, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.; Liao, W.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Sui, R.; Wang, Z.; Yang, B. New Insights into the NH3/N2O/Ar System: Key Steps in N2O Evolution. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glarborg, P.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Miller, J.A. The Reaction of Ammonia with Nitrogen Dioxide in a Flow Reactor: Implications for the NH2 + NO2 Reaction. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1995, 27, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulch, D.L.; Bowman, C.T.; Cobos, C.J.; Cox, R.A.; Just, T.; Kerr, J.A.; Pilling, M.J.; Stocker, D.; Troe, J.; Tsang, W.; et al. Evaluated Kinetic Data for Combustion Modeling: Supplement II. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2005, 34, 757–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcat, A.; Ruscic, B. Third Millennium Ideal Gas and Condensed Phase Thermochemical Database for Combustion with Updates from Active Thermochemical Tables; Argonne National Lab. (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. R and Data Mining: Examples and Case Studies; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuer, R.; Poggi, J.-M.; Tuleau-Malot, C.; Villa-Vialaneix, N. Random Forests for Big Data. Big Data Res. 2017, 9, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, P.; Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Searching for Activation Functions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.05941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, F. The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model for Information Storage and Organization in the Brain. Psychol. Rev. 1958, 65, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Moosakutty, S.P.; Rajan, R.P.; Younes, M.; Sarathy, S.M. Combustion Chemistry of Ammonia/Hydrogen Mixtures: Jet-Stirred Reactor Measurements and Comprehensive Kinetic Modeling. Combust. Flame 2021, 234, 111653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ammonia | Hydrogen | Methanol | Ethanol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen mass fraction (%) | 17.7 | 100 | 12.5 | 13.0 |

| Boiling point (°C) | −33.4 | −253.0 | 64.7 | 78.0 |

| Lower heat value (MJ/kg) | 18.6 | 120 | 23.9 | 29.7 |

| Minimum ignition energy (mJ) | 8 | 0.02 | 0.14 | |

| LFS (cm/s) | 7 | 160 | 40 | 40 |

| Reaction Number | Reaction | A | E | UF | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | O2 + H <=> O + OH | 1.14 × 1014 | 0 | 1.5286 × 104 | 1.2 | [59] |

| 22 | H + O2 (+M) <=> HO2 (+M)(high-P-rate-constant) | 4.65 × 1012 | 0.44 | 0.0 | 1.2 | [60] |

| 29 | NH3 + HO2 <=> NH2 + H2O2 | 1.173 | 3.839 | 1.726 × 104 | 2 | [61] |

| 36 | NH2 + O2 <=> H2NO + O | 2.6 × 1011 | 0.487 | 2.905 × 104 | 1.5 | [62] |

| 37 | NH2 + HO2 <=> H2NO + OH | 1.02 × 1012 | 0.166 | −938.0 | 2 | [63] |

| 39 | NH2 + HO2 <=> NH3 + O2 | 5.91 × 107 | 1.59 | −1373.0 | 2 | [63] |

| 40 | NH2 + HO2 <=> HNO + H2O | 2.19 × 109 | 0.791 | −1428.0 | 2 | [63] |

| 46 | NH2 + NH2 <=> NH3 + NH | 5.64 | 3.53 | 550.0 | 1.5 | [64] |

| 47 | NH2 + NH2 <=> N2H4 (p=10 atm) | 3.2 × 1049 | −11.18 | 1.39885 × 104 | 1.2 | [63] |

| 76 | NH2 + NO2 <=> H2NO + NO | 8.6 × 1011 | 0.11 | −1186.0 | 2 | [65] |

| 77 | NH2 + NO2 <=> N2O + H2O | 2.2 × 1011 | 0.11 | −1186.0 | 1.5 | [66] |

| 78 | NH2 + NO <=> N2 + H2O | 2.6 × 1019 | −2.369 | 870.0 | 1.5 | [66,67] |

| 79 | NH2 + NO <=> NNH + OH | 4.3 × 1010 | 0.294 | −866.0 | 1.5 | [66,67] |

| 99 | N2H4 + NH2 <=> N2H3 + NH3 | 3,700,000 | 1.94 | 1630 | 2 | [67] |

| 113 | N2H2 <=> NNH + H (p=10 atm) | 3.1 × 1041 | −8.42 | 7.60042 × 104 | 2 | [67] |

| 142 | NO + HO2 <=> NO2 + OH | 2.11 × 1012 | 0 | −480 | 1.5 | [68] |

| 163 | HONO + NH2 <=> NH3 + NO2 | 317 | 2.83 | −3570 | 1.5 | [63] |

| 173 | H2NO + NH2 <=> HNO + NH3 | 9.48 × 1012 | −0.081 | −1643.4 | 2 | [69] |

| 174 | H2NO + O2 <=> HNO + HO2 | 172,300 | 2.188 | 1.801 × 104 | 2 | [65] |

| 183 | H + NO2 <=> OH + NO | 8.85 × 1013 | 0 | 0 | 2 | [63] |

| Models | R2 | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| GLR | 0.5855 | 995 |

| SVM | 0.8971 | 496 |

| RF | 0.9761 | 239 |

| MLP | 0.9807 | 214 |

| LeNet-5 | 0.9858 | 184 |

| ResNet | 0.9923 | 135 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Zhong, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, K.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Z. A Deep Neural Network-Based Approach for Optimizing Ammonia–Hydrogen Combustion Mechanism. Energies 2025, 18, 5877. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225877

Xu X, Zhong J, Hu Y, Zhang R, Zhang K, Qi Y, Wang Z. A Deep Neural Network-Based Approach for Optimizing Ammonia–Hydrogen Combustion Mechanism. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5877. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225877

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xiaoting, Jie Zhong, Yuchen Hu, Ridong Zhang, Kaiqi Zhang, Yunliang Qi, and Zhi Wang. 2025. "A Deep Neural Network-Based Approach for Optimizing Ammonia–Hydrogen Combustion Mechanism" Energies 18, no. 22: 5877. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225877

APA StyleXu, X., Zhong, J., Hu, Y., Zhang, R., Zhang, K., Qi, Y., & Wang, Z. (2025). A Deep Neural Network-Based Approach for Optimizing Ammonia–Hydrogen Combustion Mechanism. Energies, 18(22), 5877. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225877