Social Control vs. Energy Management and Civilization Normotype from the Perspective of Sociocybernetics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Theoretical Basis of the Undertaken Analysis

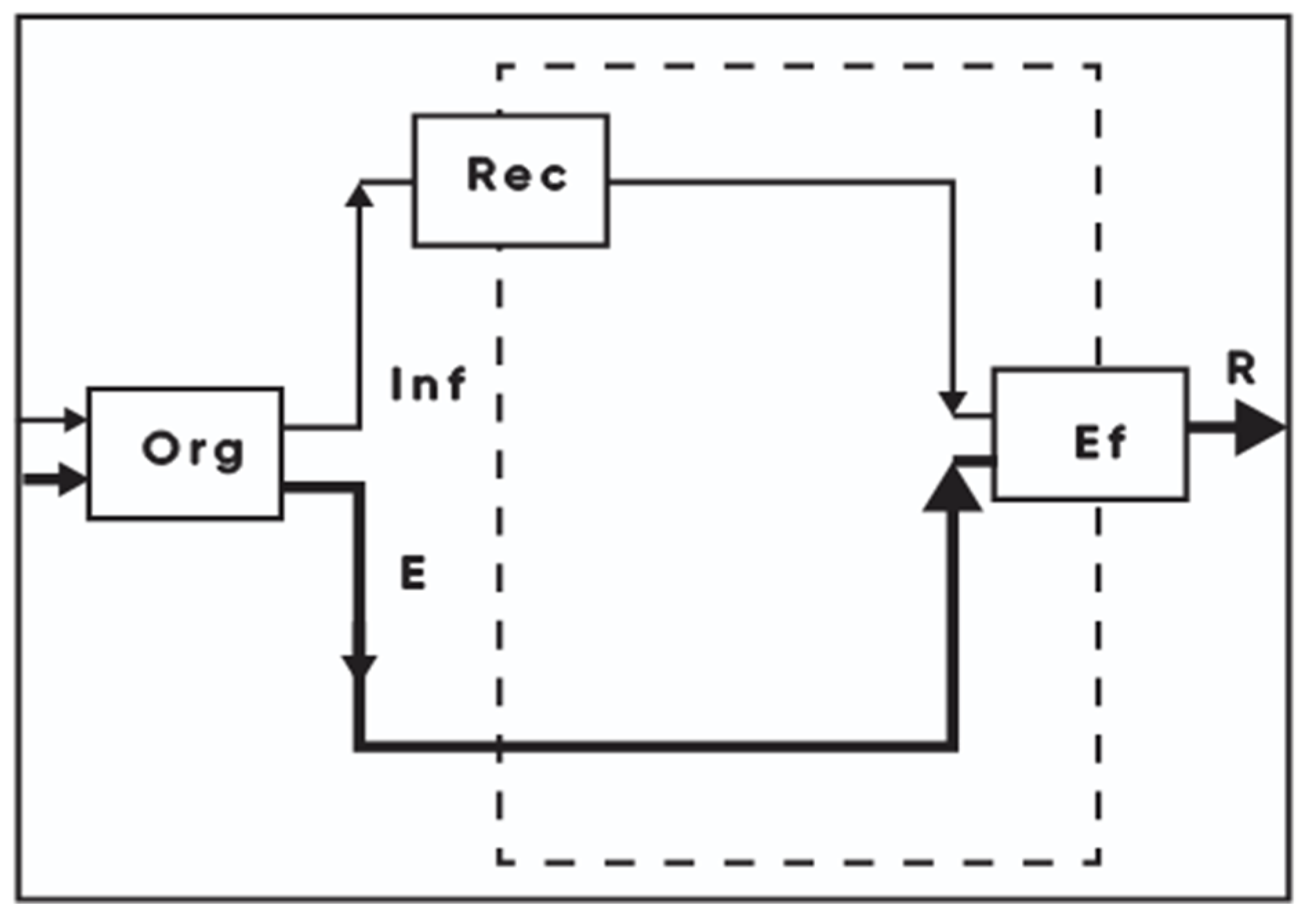

Energy and Information Processes as Well as System Independence from a Cybernetic Perspective

- (1)

- Energetic processes, which involve bringing into the system the material–energy (material and energy) needed to cause a given reaction;

- (2)

- Informational processes, consisting in causing a certain reaction among many possible ones, which is the basis of social control.

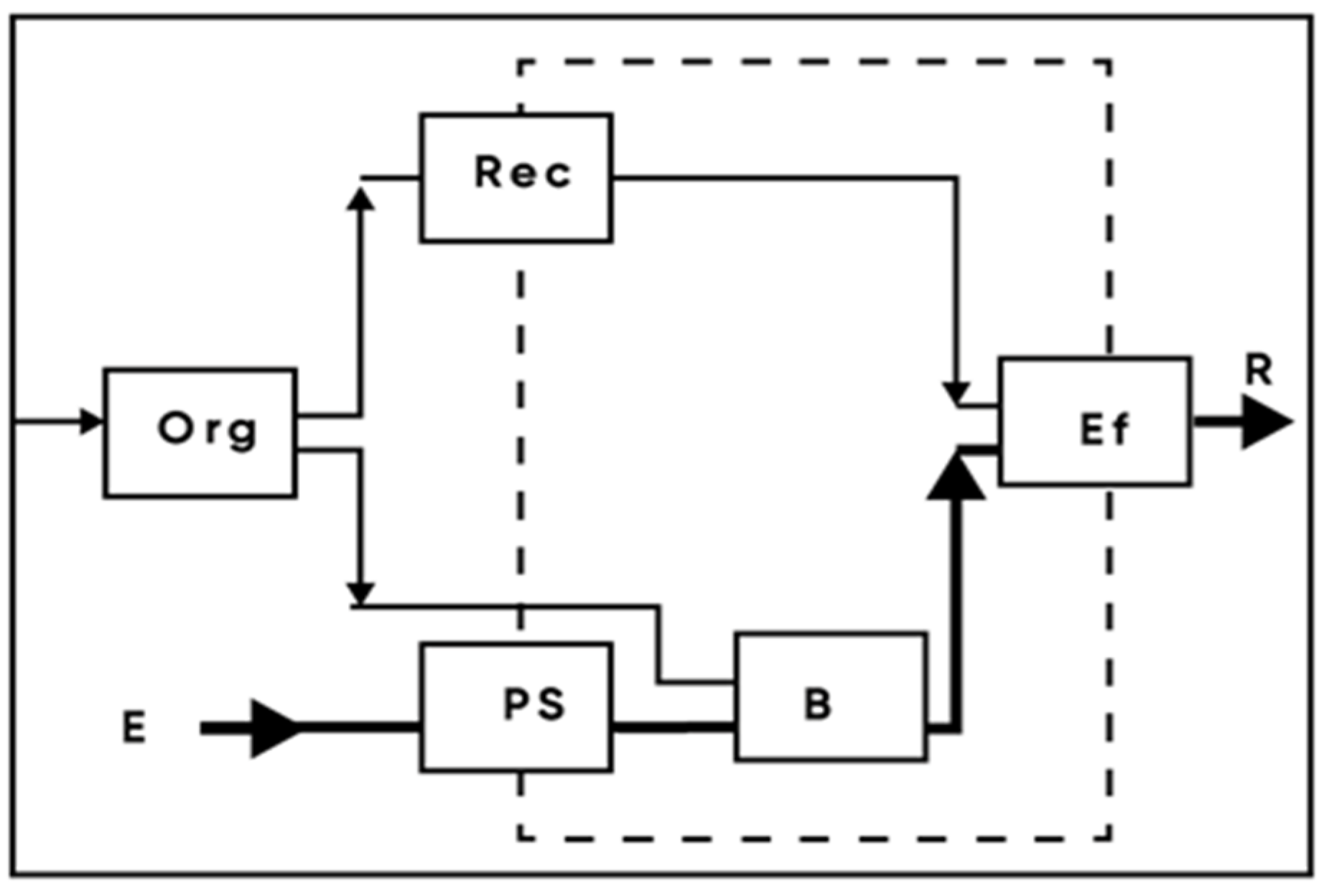

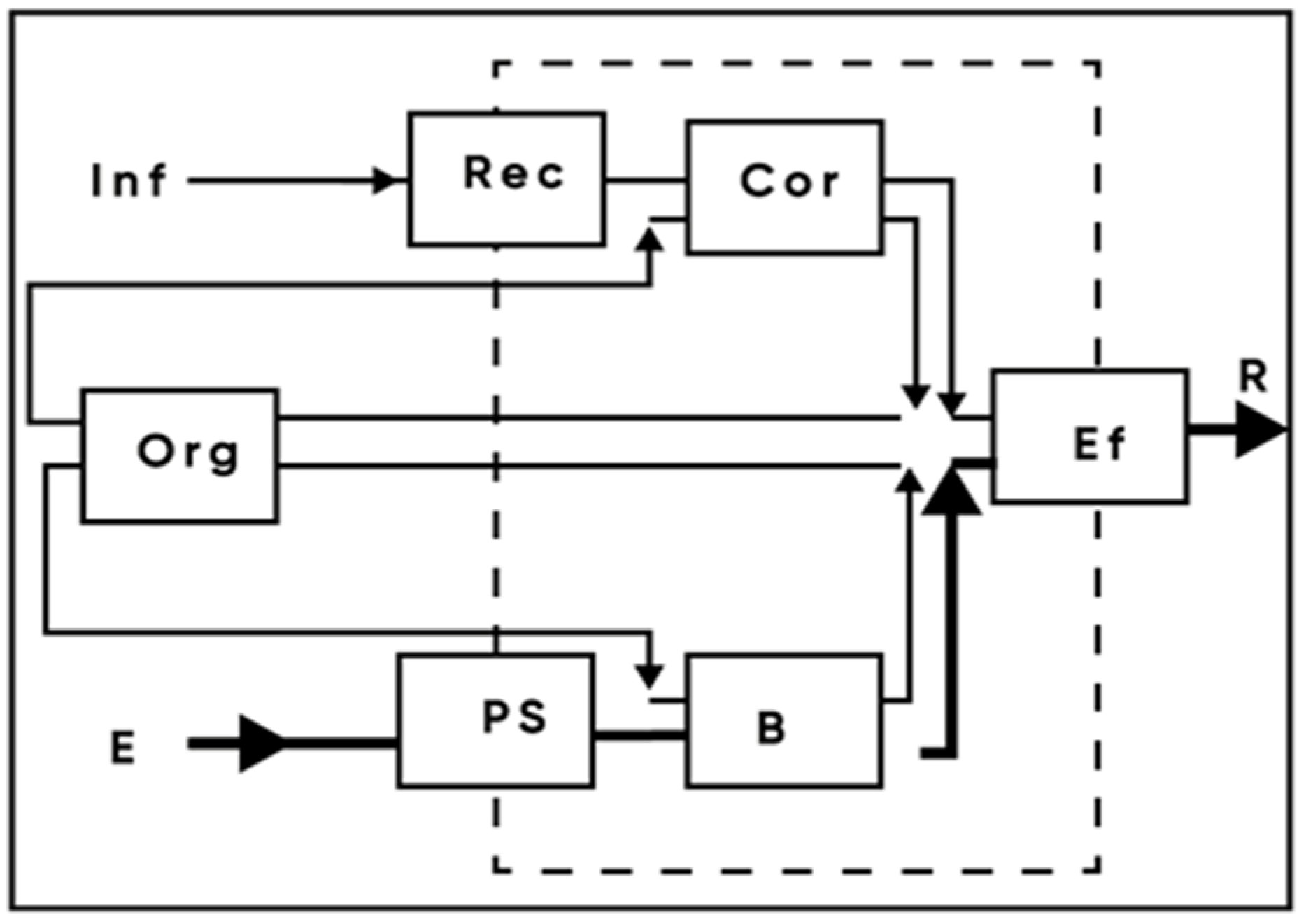

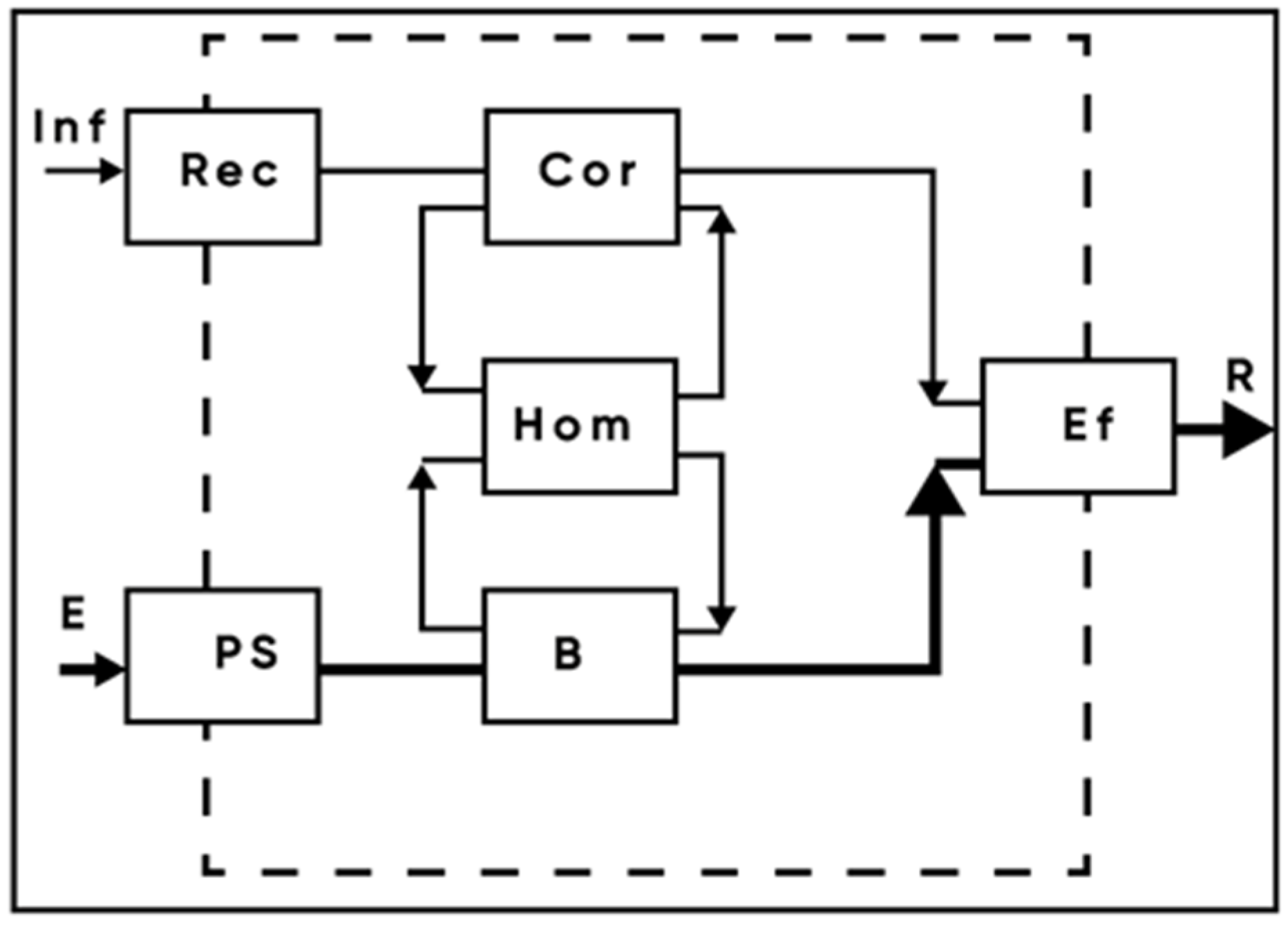

- (1)

- Receptors (Recs) are fulfilled by television stations, news agencies, the Internet, Institute for Public Opinion research, intelligence and counterintelligence agencies, and other entities;

- (2)

- Power supplies (PSs) and batteries (Bs) are fulfilled by the economy: power supplies are mainly the energy industry and agriculture, while energy terminals and the processing industry, as well as other entities, act as batteries (Bs);

- (3)

- The correlator (Cors) supports all institutions engaged in collecting and processing information: national security offices, business information offices, archives, libraries, scientific and administrative institutions, and other entities;

- (4)

- Effectors (Efs) are performed by all executive bodies through which the state interacts with its environment: public administration, police, military and other bodies;

- (5)

- The homeostat (Hom) can be fulfilled by the governing bodies of the state (including parliament), classes and social strata (which vary at different stages of history), certain social organizations and institutions with appropriate moral authority (including religious institutions), and other entities [8].

4. Energy Transformation and Civilization Normotype in Control Processes

5. Variants of Global Society and Cybernetic Models in the Context of Global Energy Management

6. Public Mood in IPSOS Surveys

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiener, N. Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine; The Technology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, N. Cybernetyka a Społeczeństwo (Cybernetics and Society), 2nd ed.; Książka i Wiedza: Warsaw, Poland, 1961; pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Cybernetics and Management; English Universities Press: London, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution and Epistemology; Chandler Publishing Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Social Systems; Stanford University Press: Standford, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maturan, H.R.; Varel, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living; D. Reidel Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, M. Cybernetyka i Character (Cybernetics and Character); Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy: Warsaw, Poland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kossecki, J. Cybernetyka Społeczna (Sociocybernetics); Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warsaw, Poland, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, H. Zasady Socjologii (Principles of Sociology); Głos: Warsaw, Poland, 1889; Parts 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, L. Ogólna Teoria Systemów (General Theory of Systems); Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warsaw, Poland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, M.; Friedberg, E. Człowiek i System. Ograniczenia Działania Zespołowego (Man and the System. Limitations of Teamwork); Państwowe Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kossecki, J. Granice Manipulacji (The Limits of Manipulation); Młodzieżowa Agencja Wydawnicza: Warsaw, Poland, 1984; pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, M. The Bureaucratic Phenomenon; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009; pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Globalizacja. I co z Tego Dla Ludzi Wynika (Globalization. The Human Consequences), 1st ed.; PIW: Warsaw, Poland, 2000; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lewada, J. Kibierneticheskie metody v sotsiologii. Kommunist. In General System Theory: Essays on Its Foundation and Development; Bertalanffy, L., Ed.; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ruesch, J. Epilogue. In Toward a Unified Theory of Human Behavior, 2nd ed.; Grinker, R.R., Ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Urbinati, N. Representative Democracy and Its Critics, Chapter 1. In The Future of Representative Democracy; Alonso, S., Keane, J., Merkel, W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. Globalizacja (Globalization), 1st ed.; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, M. Cybernetyczna Teoria Układów Samodzielnych (Cybernetic Theory of Autonomous Systems); Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warsaw, Poland, 1966; pp. 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Smill, V. Energia i Cywilizacja. Tak Tworzy się Historia (Energy and Civilization. This Is How History Is Made); Helion SA: Gliwice, Poland, 2022; p. 265. [Google Scholar]

- van Dujn, I.J. The Long Wave in Economic Life; George Alllen and Unwin: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wyleżałek, J. Dilemmas around the Energy Transition in the Perspective of Peter Blau’s Social Exchange Theory. Energies 2021, 14, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kėdaitienė, A.; Klyvienė, V. The Relationships Between Economic Growth, Energy Efficiency and CO2 Emissions: Results for the Euro area; Vilnius University Press: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020; Volume 99, pp. 6–25. [Google Scholar]

- von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Essays on its Foundation and Development; George Brazille: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Morano, M. Zielone Oszustwo (Green Fraud); Biblioteka XXI Wieku: Wrocław, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Parenti, M. Dirty Truths: Reflections on Politics, Media, Ideology, Conspiracy, Ethnic Life and Class Power; City Lights Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Saługa, P.W.; Zamasz, K.; Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z.; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, K.; Malec, M. Risk-Adjusted Discount Rate and Its Components for Onshore Wind Farms at the Feasibility Stage. Energies 2021, 14, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieniewicz, R. Wiemy, co Spowodowało Blackout w Hiszpanii i Portugalii. To Sygnał Ostrzegawczy Dla Całej Europy, (We Know What Caused the Blackout in Spain and Portugal. It’s a Warning Signal for All of Europe). Available online: https://www.farmer.pl/energia/oze/wiemy-co-spowodowalo-blackout-w-hiszpanii-i-portugalii-to-sygnal-ostrzegawczy-dla-calej-europy,160673.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Tönnies, F. Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887). Reprint; Kessinger Publishing LLC.: Whitefish, MT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, J. Research Project Manager, The Title of the Project: Architecture and Infrastructure of the Great Reset: A Study of the Transformation Towards the Information Civilization. Available online: https://gr.ans.pw.edu.pl/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Tooze, A. Welcome to the World of the Polycrisis. Financial Times. 2022. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/498398e7-11b1-494b-9cd3-6d669dc3de33 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Nowy światowy nieład? Przewodnik po polikryzysie IPSOS, Globalne Trendy 2023. (A New Global Disorder? A Guide to the Polycrisis. IPSOS, Global Trends 2023). Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en/ipsos-releases-global-trends-2023-new-world-disorder (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Co Martwi Świat? (What Worries the World?); IPSOS: North Sydney, Australian, 2025.

- Bricker, D. Sprawy Światowe, (World Affairs); IPSOS: North Sydney, Australian, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Globalny Indeks Zaufania, (Global Trust Index); IPSOS: North Sydney, Australian, 2024.

- Predictions 2025. Report; IPSOS: North Sydney, Australian, 2024; pp. 44–48. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en/global-opinion-polls (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024/executive-summary (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Zhang, N.; Yan, J.; Hu, C.; Sun, Q.; Yang, L.; Gao, D.W. Price-Matching-Based Regional Energy Market with Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 11103–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Determining Standards | Objectives of Social Action | Methods of Social Action |

|---|---|---|

| Types of Norms | ||

| Cognitive norms—science, art, and intelligence | Scientific research plans, promoted art trends, and gaining information through intelligence operations | Methodology of scientific research and dissemination activities and intelligence methods |

| Constitutive decision norms—law, ethics, and ideology | Ideological norms | Legal and ethical norms |

| Economic decision-making norms—economy | Business plans | Production technology |

| Vital decision-making norms—medicine and the army | Defense, security, and health care plans | Safety guarantees and methods of treatment and healthcare |

| Global Society Model | Characteristics of a Global Society | Reference to the Cybernetic Model Of a Control System |

|---|---|---|

| Global Gesellschaft I Egalitarian version | Nation-states participate in the relationship as equal partners engaged in mutually beneficial cooperation in the economic, political, and cultural fields. | Global society is a self-contained system based on the mutual cooperation of independent subsystems; this variant assumes the possibility of the reconstruction of the community on a global scale.* |

| Global Gesellschaft I Hierarchical version | The existence of a leading superpower or superpowers is recognized, which, without interfering in the internal affairs of other countries, takes on the responsibility of maintaining the world order. | A global society is a self-controlled system that has an external organizer acting in the interests of the subsystems (however, the system is no longer fully self-contained). |

| Global Gesellschaft I Deformation of the hierarchical version | Leading powers begin pursuing policies that primarily prioritize their own economic interests, using their advantage to impose regulations on other countries. | Global society is a control system acting in the interest of the organizer from whom it receives control signals; it ceases to be capable of processing and storing information that has control value in its interest. |

| Global Gesellschaft II | The disappearance of nation-states, with unification occurring regionally first and then globally under the authority of a common political organization or supranational world government. | A global society is a total system with an external organizer controlling both access to energy sources and information. The organizer acting with stimuli on the system’s receptor causes a specific effector response, resulting in changes in the environment until the goal set by the organizer is achieved. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wyleżałek, J.M. Social Control vs. Energy Management and Civilization Normotype from the Perspective of Sociocybernetics. Energies 2025, 18, 5786. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215786

Wyleżałek JM. Social Control vs. Energy Management and Civilization Normotype from the Perspective of Sociocybernetics. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5786. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215786

Chicago/Turabian StyleWyleżałek, Joanna Marta. 2025. "Social Control vs. Energy Management and Civilization Normotype from the Perspective of Sociocybernetics" Energies 18, no. 21: 5786. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215786

APA StyleWyleżałek, J. M. (2025). Social Control vs. Energy Management and Civilization Normotype from the Perspective of Sociocybernetics. Energies, 18(21), 5786. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215786