1. Introduction

The attention to energy saving and energy efficiency has been growing worldwide since the 1970s. Regarding the energy performance of buildings, Italy has certainly played a pioneer role within the EU, having the first specific regulations with Law 373/76, Law 10/91, and D.P.R. 412/93. In detail, the first constraints were implemented for thermal insulation, components’ performance, and installation and maintenance of heating systems. Indeed, according to a recent survey [

1], in Italy the energy consumption in the residential sector from 1990 to 2021 has increased by 22.9%: it grew until 2010 (+1.5%/year), then it started reducing (−0.9%/year) due to combined actions (both regulatory and financial/fiscal) for improving energy efficiency. In 2021, energy consumption in the residential sector was 32.0 Mtep, +4.5% compared to 2020, and mainly involved natural gas, solid biofuels, electricity, and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). Other renewable energy sources are growing, but their weight is reduced. The effect of the pandemic on family energy consumption has been absorbed by the resumption of normal activities, while consumption for air conditioning is increasing.

In the wider framework of the European Union, the building stock is responsible for around 40% of the annual energy consumption and for 36% of the greenhouse gas emissions [

2]. Accordingly, due to the several regulations enacted in the last decades, prescribed values of the global heat transfer coefficient have to be accounted for and the resulting potential savings can be estimated [

3,

4,

5]. For instance, in Italy the thermal transmittance of perimeter vertical walls for existing buildings subject to energy refurbishment has to be lower than 0.38 W/(m

2 K) to lower than 0.22 W/(m

2 K), depending on the specific climatic region [

6], while local fiscal bonuses provide even stricter values.

Thus, the study of advanced physical phenomena that can affect, even locally or temporarily, thermal transmittance deserves great attention. If one neglects internal and external finishes, external walls are generally composed of two main parts, a structural layer to support the mechanical load and an insulating layer to reduce heat transfer. Accordingly, a vertical wall can be seen as the sequence of two (or more) porous layers saturated by air and made with solid materials that differ in permeability, porosity, conductivity, and diffusivity. When the air within the pores is still or in purely vertical flow, the resulting thermal transmittance can be low. On the other hand, if the thermal boundary conditions lead to thermal instability, meaning multicellular flow patterns, of the natural convective flow through open cells, worse insulating performance is expected.

The present paper aims to investigate such a phenomenon, namely, to find the threshold values of the modified Darcy–Rayleigh number for the onset of linear instability within a two-layer porous wall subject to isothermal boundary conditions. This problem follows the path started with the pioneering study by Gill [

7], who proved that a vertical porous slab bounded by impermeable surfaces at different temperatures is always a stable configuration from the thermal viewpoint. Thus, a natural convection system of cells that produces an increase in thermal transmittance is impossible in that case. Even when one relaxes the infinite Prandtl–Darcy number assumption, i.e., when Darcy’s law is slightly altered by accounting for the time-derivative of velocity in the momentum balance [

8], it is proved that the impermeable vertical layer still cannot experience the onset of thermal instability. On the other hand, Barletta [

9] demonstrated that natural convection parallel flow in a vertical porous slab can become unstable when the boundaries are isothermal but permeable surfaces. This different setup holds when the slab is confined by two isothermal environments where a fluid with a hydrostatic pressure distribution is present, which can be the case when a building vertical wall separating the internal and the external environments is considered. In such a setup, an increase in the Darcy–Rayleigh number can lead to instability. This behavior, which differs from Gill’s findings for impermeable boundaries, arises for transverse rolls and occurs at a Darcy–Rayleigh number of 197.081.

Another different setup with respect to Gill’s problem where instability can arise is studied by Shankar and Shivakumara [

10], where the boundaries are impermeable, but the porous slab is heterogeneous with a horizontal continuous change in the permeability.

Recently, Barletta et al. [

11] extended the study to a multilayered vertical porous structure where the external layers have a thermal conductivity much higher than the inner one, and the slab is bounded by impermeable and isothermal surfaces kept at different temperatures. It is found that convective instability can arise in the multilayer structure, whereas the single-layer counterpart with the same boundary conditions displays no instability. Then, the same authors studied a vertical double-layer porous slab having an open boundary and an impermeable one, kept at different uniform temperatures, in the limiting case of a porous layer that is much more conductive than the other [

12]. The linear stability analysis shows that convective instability can arise for sufficiently high values of the modified Darcy–Rayleigh number and that the permeability ratio between the two layers has a destabilizing effect.

In the present paper, the convective stability within an external vertical wall of a building will be studied. The wall will be modelled as a two-layer vertical porous structure, which is saturated by air and has two permeable boundaries kept at different temperatures. The basic stationary flow will be found and perturbed by applying small-amplitude disturbances in the form of normal modes. The perturbed governing equations will be solved numerically to determine the threshold values of the governing parameters for the onset of linear instability.

This paper eventually addresses a key question: can thermal instability arise within insulated building walls? Answering this question can provide a valuable insight into the design of effective insulating envelopes. An important aspect of this study lies in the integration of actual Italian building regulations with a known, yet tailored, analytical model. The approach extends classical Gill-type stability problems to configurations that explicitly reflect the constraints imposed by national standards—specifically, those concerning the maximum allowable thermal transmittance (

U value) for building envelopes, as defined by current Italian legislation. This regulatory framework is not merely cited but actively shapes the parametric space explored in the following analysis. Indeed, by aligning boundary conditions, wall thicknesses, and material properties with the requirements of Italian energy efficiency codes (such as those outlined in Legislative Decree 192/2005 [

13] and its subsequent updates), the present study bridges the gap between theoretical modeling and practical application. Such alignment ensures that the findings are directly relevant to real-world design scenarios, particularly in the context of retrofitting or constructing buildings that comply with national energy performance targets. This methodological innovation fills a notable gap in the literature, where most studies focus on idealized or generic configurations and tend to overlook the implications of country-specific regulatory frameworks. By contrast, the present work contributes to a more grounded understanding of heat and mass transfer phenomena within multilayered porous walls, offering a valuable reference for engineers and designers operating within the Italian regulatory landscape.

2. Mathematical Modeling of the Wall

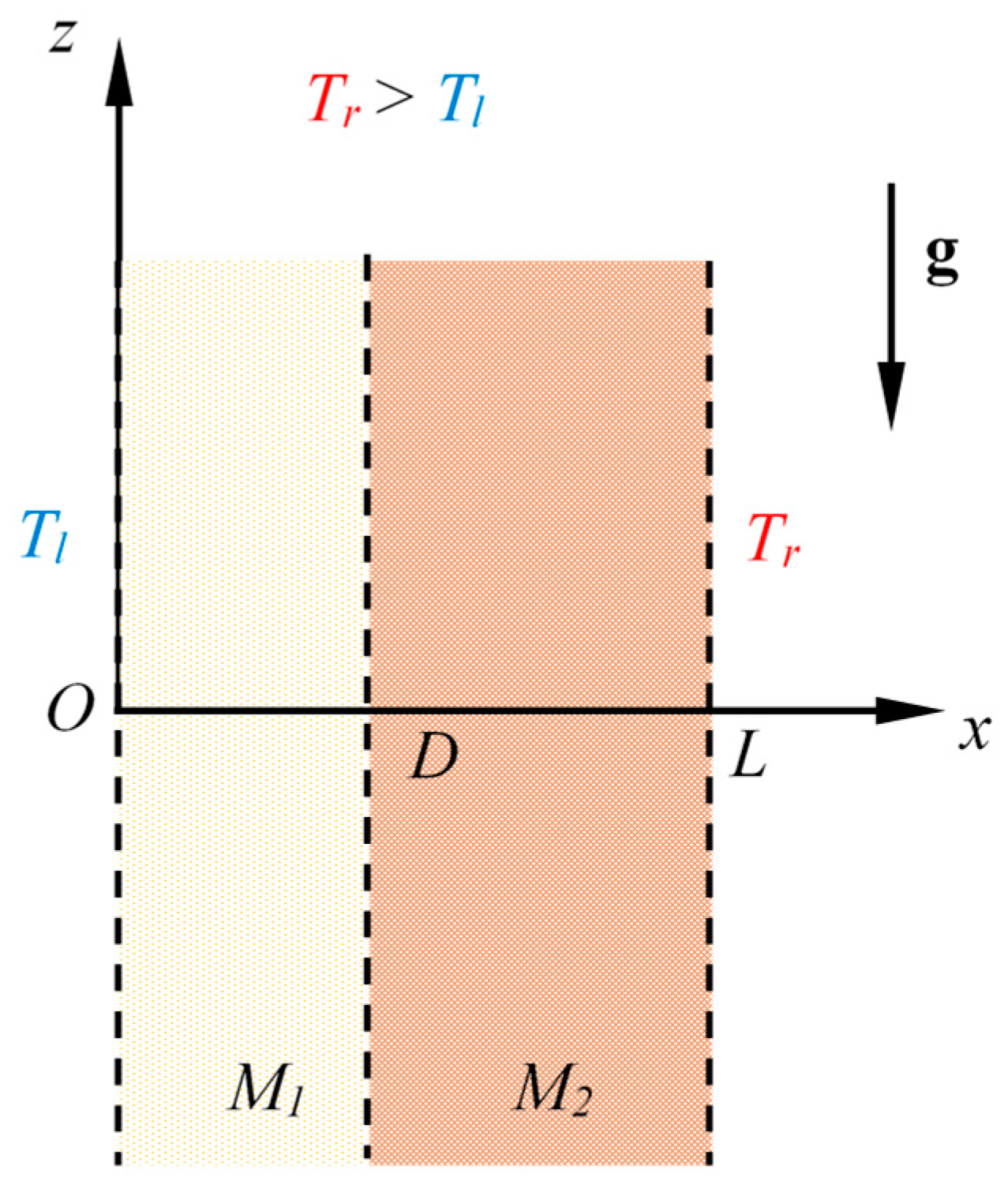

Let us sketch the external vertical wall of a building as a two-layer porous structure, as reported in

Figure 1. In detail, by neglecting the thin finishes on the two sides, the wall has an overall thickness

L, and it is composed by two layers: a first one, denoted

M1, that has thickness

D and represents the external insulating layer, and a second one,

M2, that reproduces the structural layer, having thickness (

L-

D). The two layers are bounded by permeable surfaces that are kept at uniform temperatures

Tl and

Tr, respectively, with

Tr >

Tl, so that side-heating occurs. Moreover, let us assume that the pressure distribution along the boundaries,

x = 0 and

x =

L, is purely hydrostatic, i.e., let us consider that the wall separates two environments containing still air. It is worth noting that the model described can also be easily applied to the case of breathing walls.

Due to the considered boundary conditions, a natural convection problem arises, which can be studied by means of the following governing equations:

where the index

m = 1, 2 refers to the

M1 layer and the

M2 layer, respectively. Equations (1)–(3) are the mass, momentum, and energy balance equations, written by assuming the Oberbeck–Boussinesq approximation in modeling buoyancy, by adopting Darcy’s law to model the flow within the porous media and by neglecting viscous dissipation and source/sink terms. In Equations (1)–(3),

Km,

αm, and

σm are the permeability, the thermal diffusivity, and the heat capacity ratio of the saturated porous media;

t is time; and

μ,

ρ0,

β are the dynamic viscosity, the reference density, and the coefficient of thermal expansion of the air saturating the wall.

um = (

um,

vm,

wm),

Pm and

Tm are the velocity, the dynamic pressure, and the temperature fields, respectively.

The following boundary and interface conditions hold:

Let us define the following dimensionless quantities and parameters:

where

T0 is a reference temperature, which is defined as the following,

ρ0 =

ρ(

T0), Δ

T =

Tr −

Tl, and

R is the Darcy–Rayleigh number. By introducing Equations (5) and (6) in Equations (1)–(4), and by observing that Equation (4) involves pressure and temperature only, one can conveniently rewrite the problem in the following dimensionless pressure–temperature formulation, where the asterisks are omitted to simplify the notation:

Once the dimensionless problem given by Equations (7)–(9) has been solved, the dimensionless velocity fields can be determined as

In order to solve the problem in (7)–(9), let us describe the wall as made by a single equivalent porous layer, showing a step change in its thermophysical properties to account for both layers M1 and M2. This original approach reduces the number of equations to be solved from 4 to 2, i.e., those referring to one layer only, while definition (6) leads to three explicit parameters only, namely, a, ξ, γ.

Let us reproduce the step variation between the two layers by means of the following dimensionless polynomial function

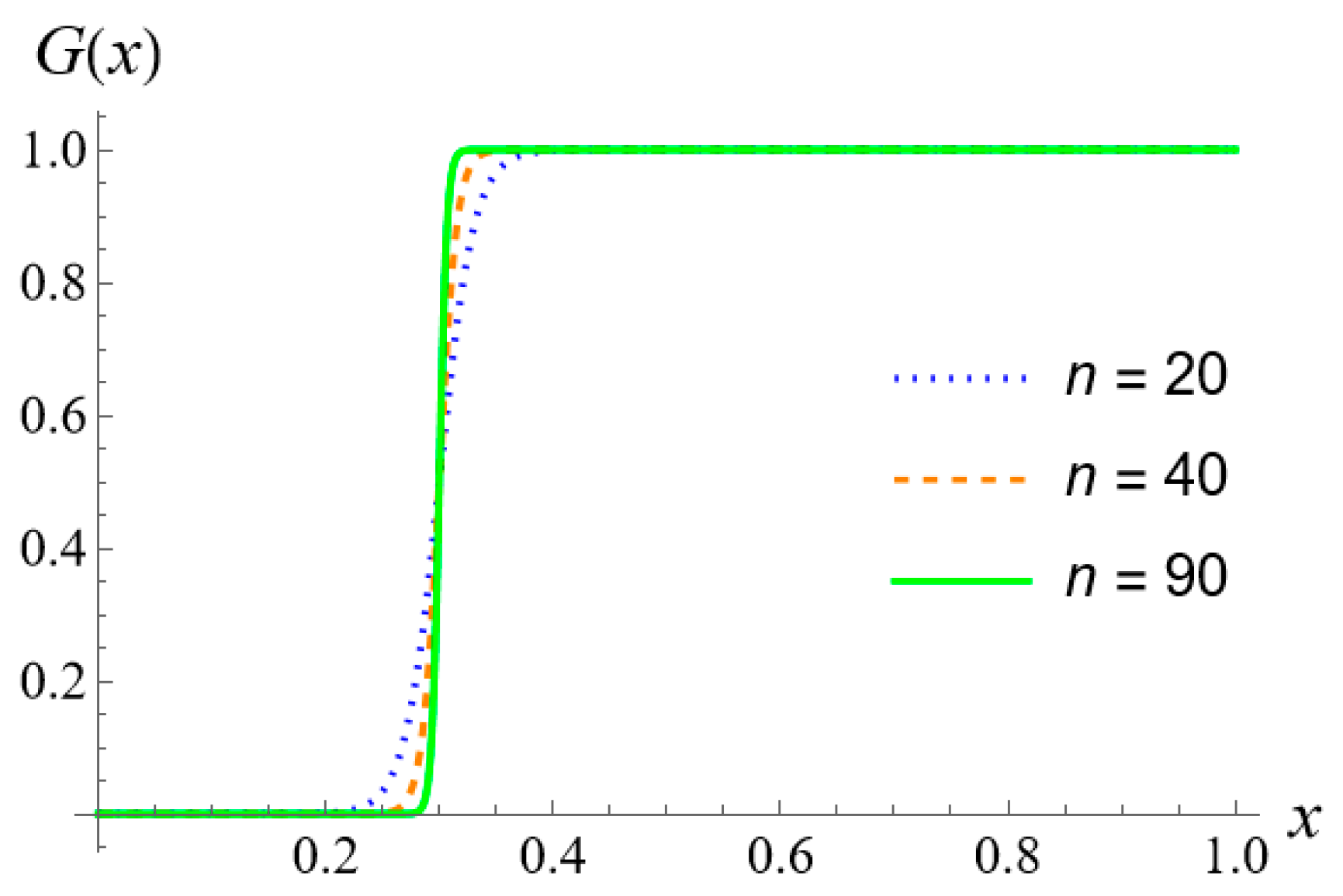

G, which is plotted in

Figure 2 for the case

a = 0.3 and for three values of the steepness parameter

n:

The function

G(

x) is adopted for replacing the two layers with a single equivalent one that spans over the entire dimensionless domain; indeed, the change in properties between the two layers is modeled by the continuous yet steep variation described by

G(

x), which can be tuned by changing the value of

n to produce a less- or more-steep transition between the layers. It is worth noting that, according to the dimensionless formulation adopted, the dimensionless domain is in the range 0 ≤

x ≤ 1; therefore, the first layer is in the range 0 ≤

x ≤

a, while the second layer is in the range

a ≤

x ≤ 1. By means of Equations (6) and (11), the dimensionless changes in the physical properties of the wall can be written as functions of the dimensionless coordinate

x in the form

In conclusion, the problem to be solved for the single equivalent layer is given by the following equations and boundary conditions:

where

.

4. Linear Stability Analysis

In order to study the onset of instability, let us perturb the basic state by applying small-amplitude disturbances in the form of normal modes, namely

where

k = (0,

ky,

kz) is the wave vector, whose modulus

k gives the wave number, which is thus a positive quantity. On the other hand,

ω is defined in the complex domain, and its real part gives the angular frequency, while its imaginary part gives the temporal growth rate. In detail, a negative value of Im(ω) dampens the instability that can thus extinguish over time. Although ω is a valuable parameter, in the current work the goal is to determine the values of the Darcy–Rayleigh number that trigger the onset of linear instability, identified as the condition where Im(ω) > 0, and to determine the most unstable modes. Indeed, the main focus is on the physical insights into natural convection within a building’s insulated wall in order to understand if and how material characteristics may affect the overall heat transfer performance of the wall.

By restricting the stability analysis to two-dimensional modes, by substituting Equation (18) into the governing equations and boundary conditions given by Equations (13)–(15), and by neglecting O(

ε2) terms, one has the following eigenvalue problem for neutrally stable modes:

where

S is the rescaled Darcy–Rayleigh number defined as

For sufficiently small values of S, the values of the growth rate Im(ω) are negative, meaning that the perturbations tend to asymptotically dampen and the flow remains stable. On the other hand, large values of S are associated to positive values of Im(ω), meaning instability. By changing the wave number k, one can find the points where Im(ω) = 0 in the parametric plane (k, S). These points serve to draw the neutral stability curve, which maps the boundary of the instability region. The absolute minimum of this curve corresponds to the absolute minimum value of the Darcy–Rayleigh number that triggers instability. The aim of the linear stability analysis is to find this value, which will be referred to as the critical value and denoted with the subscript c.

It is worth noting that the perturbations modes for the onset of instability at the lowest values of R are transverse rolls. Indeed, since k ≤ kz, with the equality holding true for the transverse rolls (ky = 0), then the last are the most unstable modes. Equations (19) and (20) define the linear stability problem, and they have to be solved simultaneously in order to find the eigenfunctions. To this aim, we rewrote the problem as a boundary value problem and found the solution numerically through a fourth-order Runge–Kutta shooting method that we implemented in Wolfram 14.2 (© Wolfram Research Inc., Champaign, IL, USA) by using the embedded functions NDSolve and FindRoot. In detail, for both the functions, the Working Precision was set to Automatic, which means computations were carried out with 16 significant digits, while for FindRoot the maximum number of iterations was set to Infinity. In all the forthcoming results, the number of stable significant figures is always 7 or above.

5. Results

The results are organized as follows: For each considered value of a, namely, a = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, the neutral stability curves are shown for some values of the parameters ξ and γ, starting from the cases where one of these two parameters is equal to one and letting the other vary in order to understand its effect on the onset of instability. Then, a table reporting the critical values for the onset of the thermal instability is provided for the considered values of a, ξ, and γ in order to easily compare the impact of these parameters. It is worth noting that these critical values are the local minima of the modified Darcy–Rayleigh number S along the neutral stability curves. Finally, the numerical model is applied to some reference walls, and the results are discussed.

5.1. Case of ξ = 1 and γ = 1

The case where

ξ = 1 and

γ = 1 represents a situation where the vertical wall is effectively made by one porous medium only, i.e., the solution of the problem given by Equations (20) and (21) reduces to that already found by Barletta [

6], namely, the well-known critical value

Sc = 197.081,

kc = 1.0595. It is worth noting that in this case the parameter

a loses its meaning, i.e., the solution is the same regardless of the considered value of

a. The result obtained for the limiting case

ξ = 1 and

γ = 1 serves as a direct comparison with classical stability theory for simpler geometries and provides a means to verify the accuracy of the numerical evaluation performed.

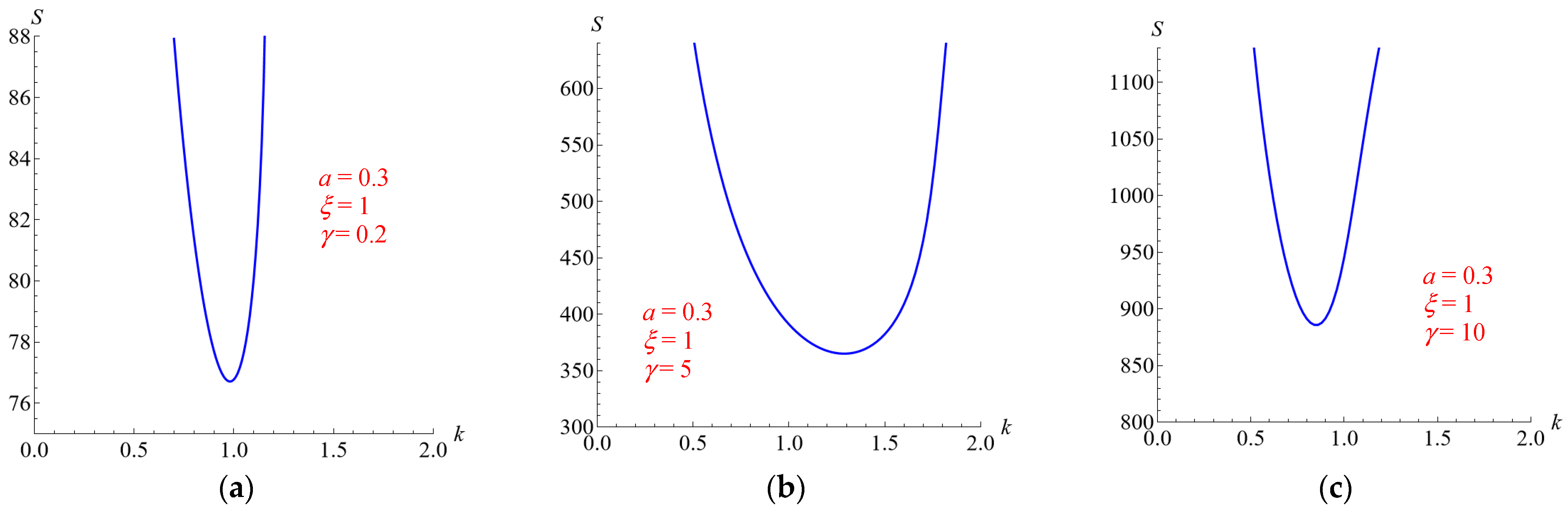

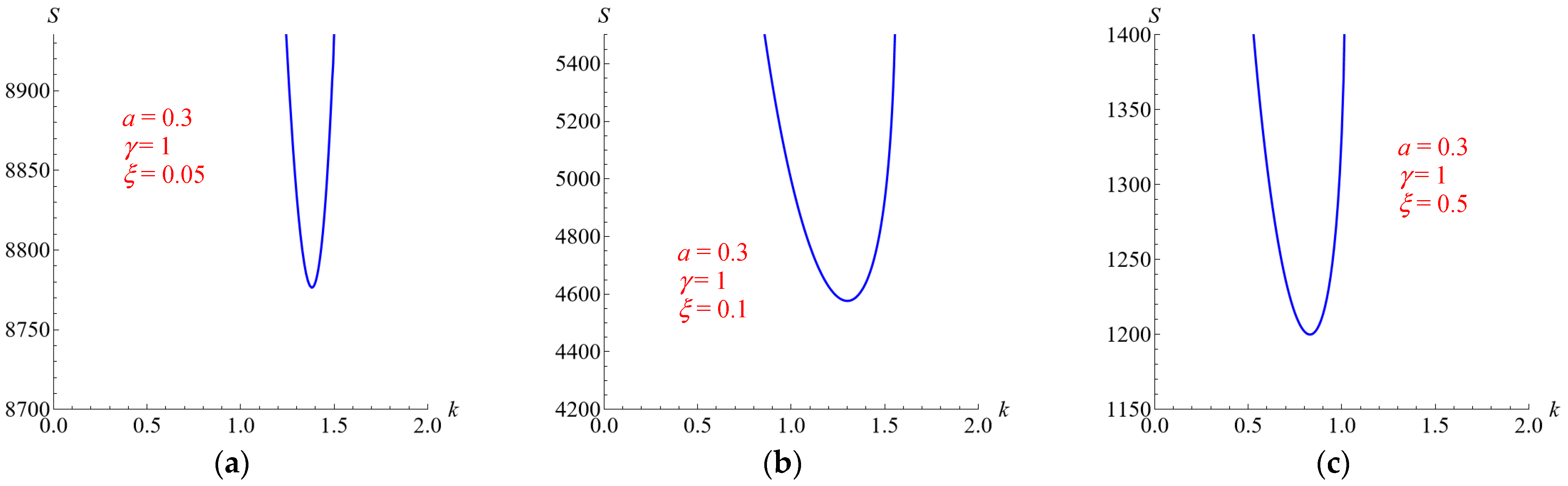

5.2. Effects of the Parameters ξ and γ for a = 0.3

In order to distinguish the effects of

ξ and

γ, let us vary one of them by fixing the other one.

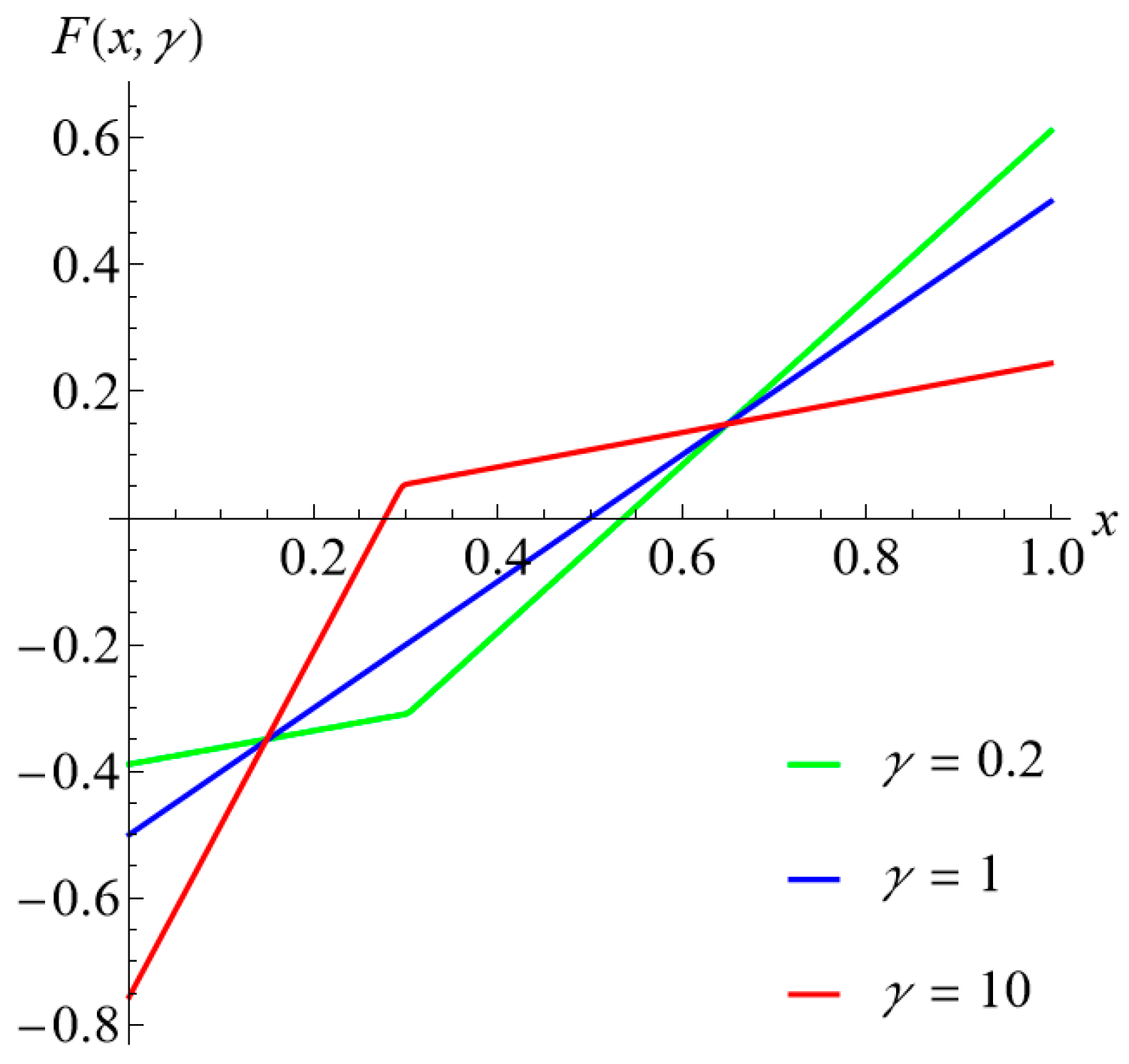

Figure 4 shows the neutral stability curves

S =

S(

k) obtained for

ξ = 1 and

γ = 0.2, 5, 10, when

a = 0.3. For the considered values of the parameter

γ, the curves move upward as

γ increases, suggesting its stabilizing role.

Figure 5 shows the neutral stability curves

S =

S(

k) obtained for

γ = 1 and

ξ = 0.05, 0.1, 0.5 when

a = 0.3. For the considered values of the parameter

ξ, the curves move upward as

ξ decreases, suggesting its destabilizing role.

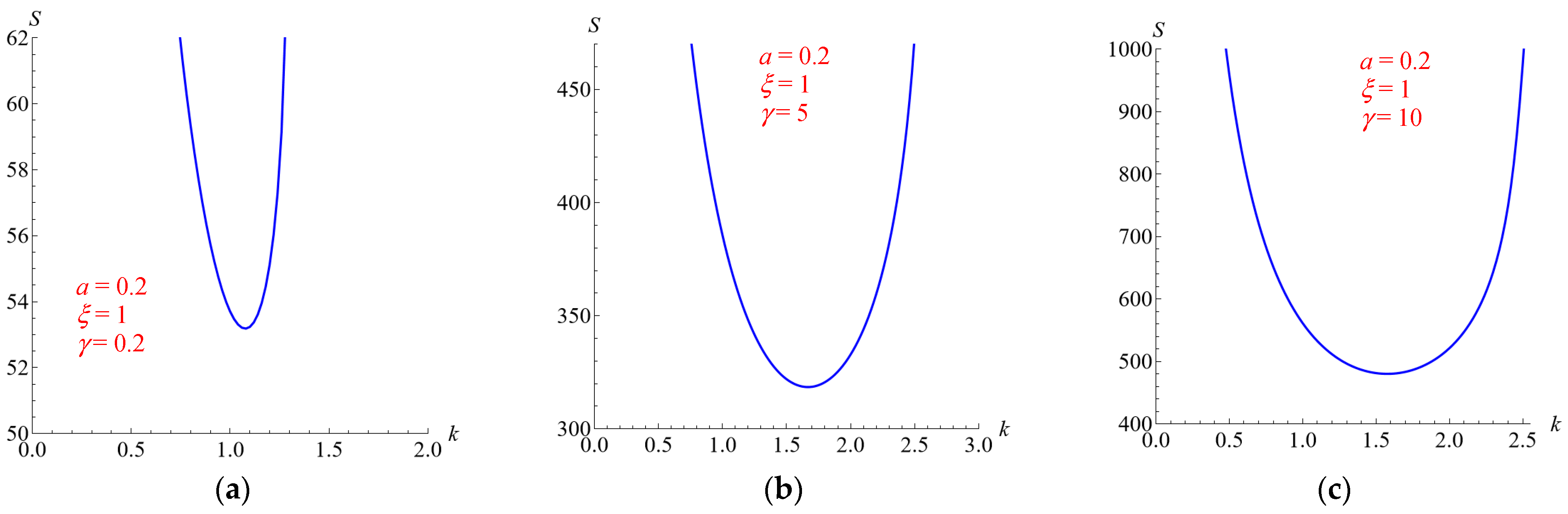

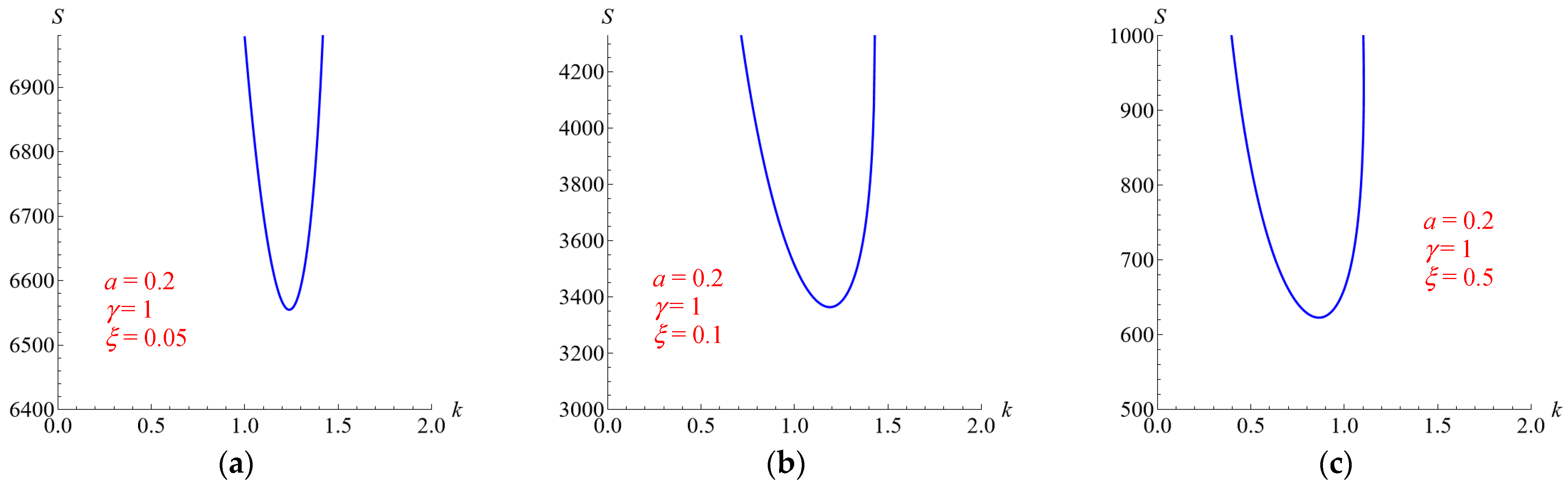

5.3. Effects of the Parameters ξ and γ, for a = 0.2

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the neutral stability curves for

ξ = 1 and

γ = 0.2, 5, 10 and for

γ = 1 and ξ = 0.05, 0.1, 0.05, respectively. Both figures refer to the case

a = 0.2. The same effect of the parameters

ξ and

γ shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 is recovered.

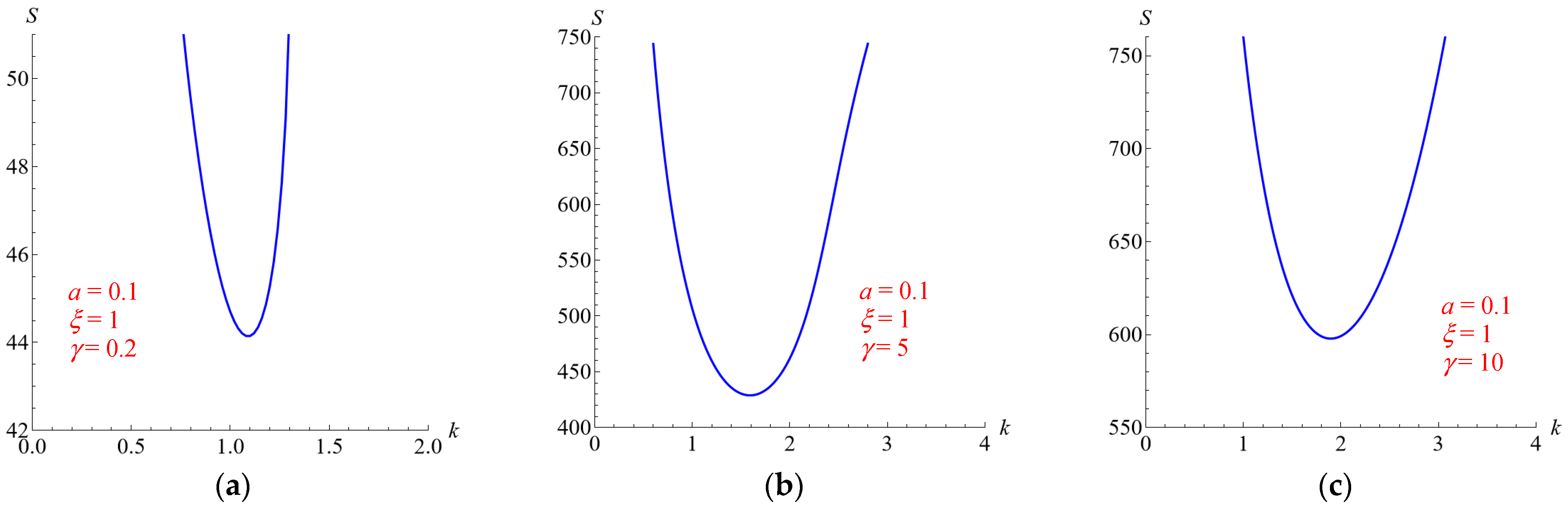

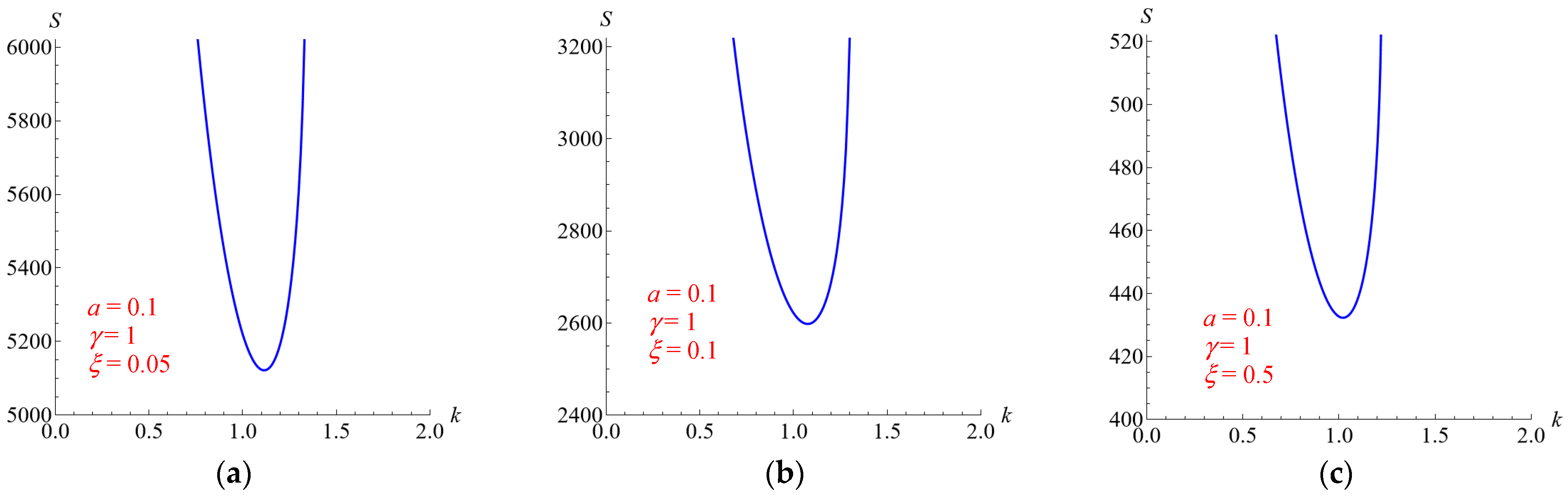

5.4. Effects of the Parameters ξ and γ for a = 0.1

The neutral stability curves for

ξ = 1 and

γ = 0.2, 5, 10 and for

γ = 1 and

ξ = 0.05, 0.1, 0.5 are given in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, respectively. Both figures refer to the case

a = 0.1.

The comparisons between

Figure 4,

Figure 6 and

Figure 8 and between

Figure 5,

Figure 7 and

Figure 9 show that the aspect ratio

a has a non-monotonic effect on the stability with reference to the changes in the parameter

γ, whereas for decreasing values of

a and

ξ (for

γ = 1), the value of

Sc increases.

Table 1 reports the critical values

kc and

Sc for the onset of the thermal instability with reference to the cases shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. The table shows that

Sc is an increasing function of

γ for each considered value of

a. On the contrary,

Sc decreases as

ξ increases, suggesting a destabilizing effect of this last parameter, namely, the neutral stability curves move downward as

ξ increases. On the other hand,

kc does not have a monotonic trend.

Table 1 suggests that, as the value of

a decreases, an increase in

γ leads to a greater percentage rise in

Sc when

γ is sufficiently small, whereas it results in a smaller percentage rise in

Sc for higher values of

γ. Moreover, the decrease in

a has only a slight effect on the percentage reduction in

Sc as

ξ increases. Overall, for given values of (

ξ,

γ), the lowest value of

Sc corresponds to the smallest value of

a. It is worth mentioning that, for given values of

γ and

ξ, the numerical solution becomes hard to find as

a increases.

5.5. Practical Examples

Let us focus on feasible external vertical walls of a building. In order to refer to realistic values of the dimensionless parameters (6), let us choose some walls such that their overall thermal transmittance fulfils the Italian requirements for the most severe climatic region, namely,

U < 0.22 W/(m

2 K). Other walls are chosen to fall within the range of admittable values, 0.22 <

U < 0.38 W/(m

2 K). Lastly, the other walls present a quite high thermal transmittance and represent those walls that have been poorly insulated, for instance, because their refurbishment occurred before the latest version of the prescription law (when the admittable values were higher) or because other constraints prevented the reaching of the desired value of

U. Among the numerous combinations of thickness and materials that can be considered feasible, we refer to those reported in

Table 2 in order to obtain an estimate for the working range of the governing parameters. The values of the thermophysical properties were taken from the producer’s datasheets, whenever available, or from handbooks. For the evaluation of the thermal transmittance, the surface thermal resistances on the internal and external surfaces are assumed to be equal to 0.13 and 0.04 m

2 K/W, respectively, as reported in the standard UNI EN ISO 6946:2008 [

14] for horizontal heat flux. Moreover, the overall resistance due to the internal and external finishes (plaster) is accounted for as 0.038 m

2 K/W.

Table 2 reports the main quantities for the six reference walls.

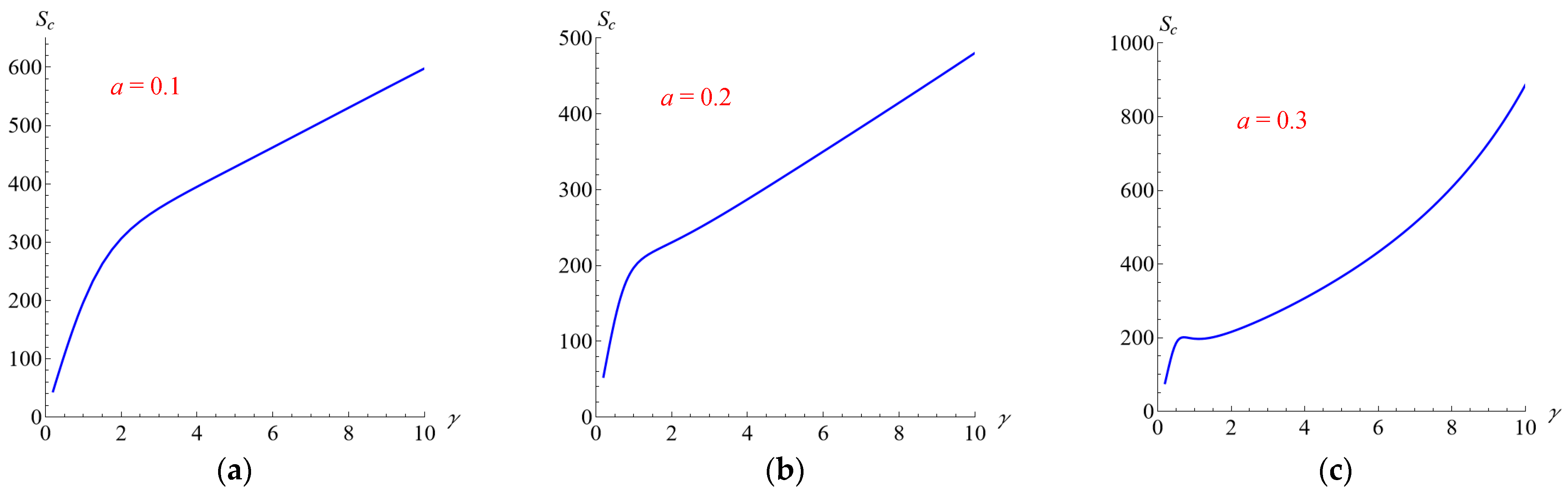

In order to study linear convective stability of these walls and obtain a deeper understanding of the heat transfer through the opaque building envelope, let us consider the trend in

Sc as a function of

ξ and

γ, as reported in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, respectively.

These results show that the most important parameter triggering convective instability is

ξ. Indeed, although according to

Figure 10 thermal instability can arise for small values of

Sc for all the reference walls in

Table 2,

Figure 11 shows that, regardless of the value of

a, one has an extremely high

Sc as

ξ tends to 0.

To better understand the implications of these two figures, let us now consider the wall denoted as #1 in

Table 2, namely, a wall made by a 36 cm layer of brick and a 12 cm insulating layer of glass wool for which

a = 0.25,

γ = 0.18,

ξ = 0.00045. According to Equations (6) and (21), and by assuming for the air saturating the wall

ρ0 = 1.2 kg/m

3,

β = 1/293 = 3.4 × 10

−3 K

−1,

μ = 1.8 × 10

−5 kg/(m s), while for the insulating layer

K1 = 3.8 × 10

−17 m

2,

α1 = 2.4 × 10

−6 m

2/s, one has that the temperature difference Δ

T corresponding to the onset of convective instability is larger than 10

10 °C. Thus, in this case there is no actual possibility for the onset of convective instability, and, consequently, no negative effects on the thermal transmittance are expected. The same kind of result holds when analyzing the other feasible walls in

Table 2.

Accordingly, although the analysis shows that some combinations of values (a, ξ, γ) can exist such that the conditions for the onset of convective linear instability could also arise for relatively small values of Sc, the corresponding critical values of ΔT are always far too large to be comparable to practical operating conditions.