The Usage of Big Data in Electric Vehicle Charging: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

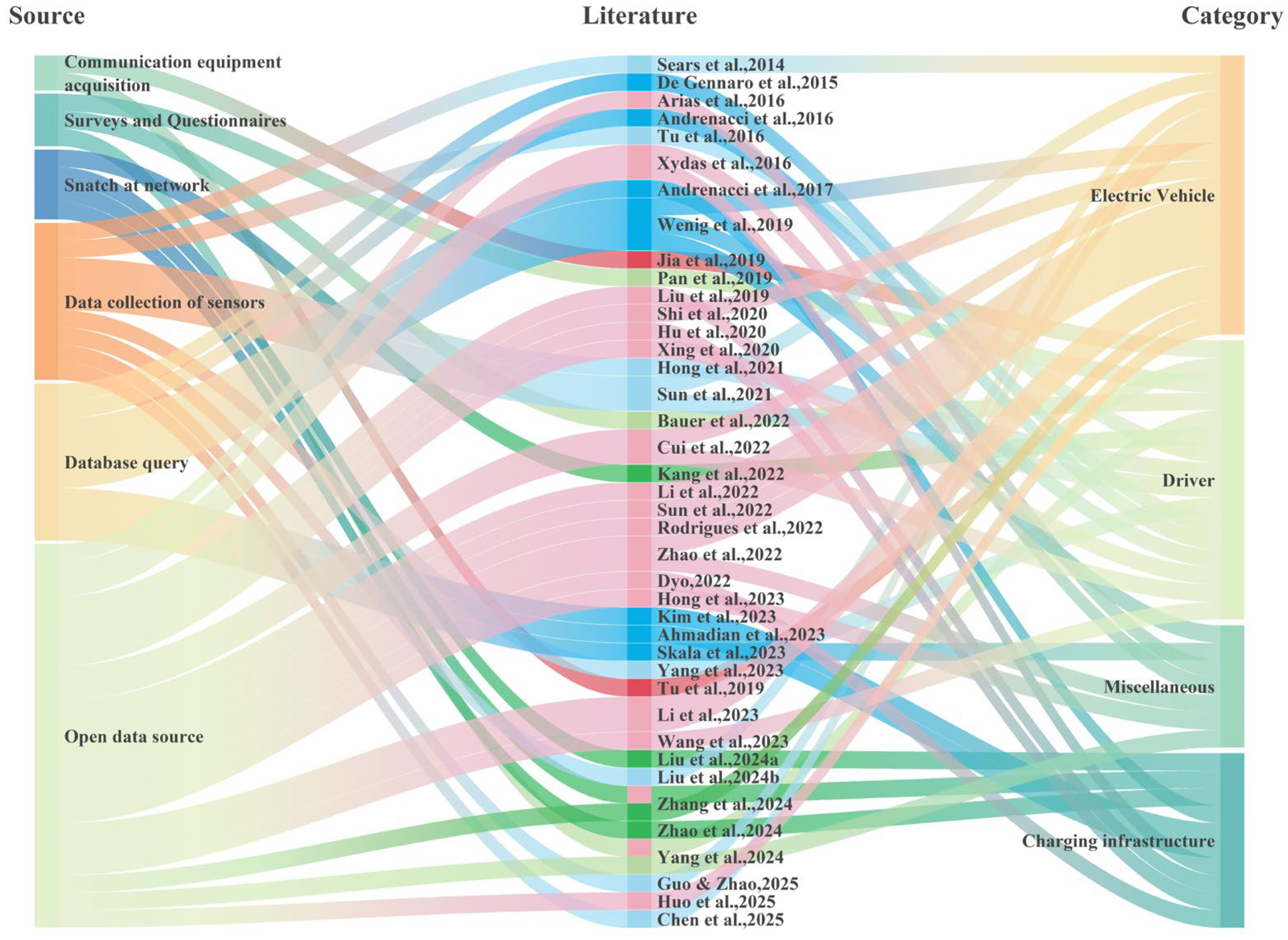

2. Review Methodology

2.1. Databases Searched

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

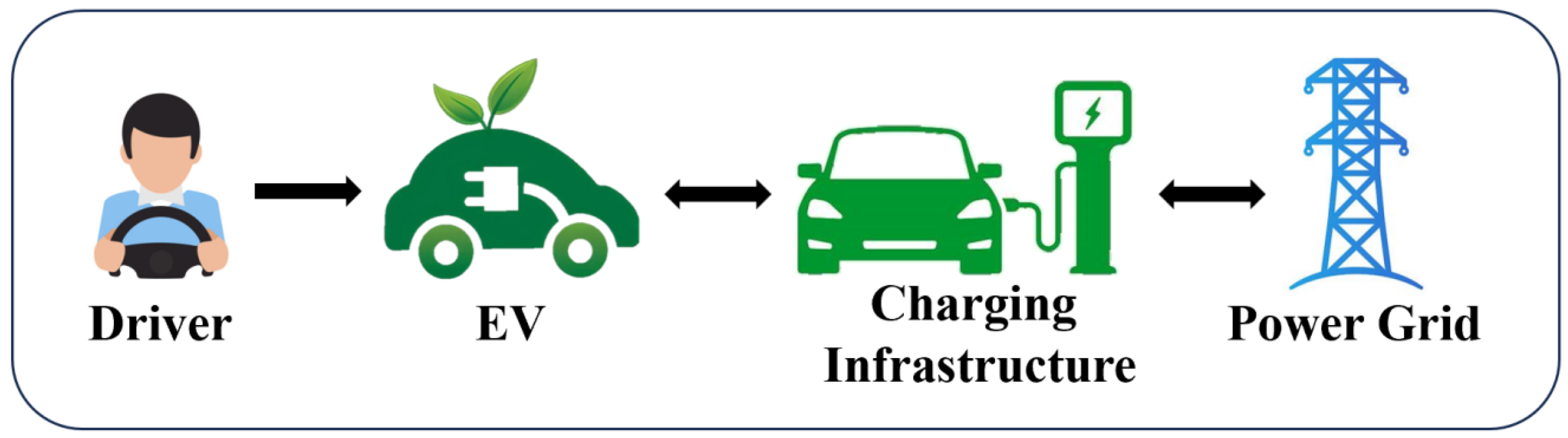

3. Big Data Generated by EV Charging

3.1. The Chain of EV Charging

3.2. Big Data Generated by EV Drivers

3.3. Big Data Generated by EVs

3.4. Big Data Generated by Charging Infrastructures

3.5. Big Data Generated by Power Grid

3.6. Big Data Generated by Others

4. Key Issues in EV Charging That Big Data Can Address

4.1. Optimized Control of Grid Operation

4.2. Charging Infrastructure Layout

4.3. Battery Development

4.4. Dynamic Pricing of Charging Network

4.5. Safety of Charging Equipment

5. Data Collection and Data Processing in EV Charging Applications

5.1. EV Charging Big Data Collection

5.2. EV Charging Big Data Analysis

| Big Data Analytics Algorithm | Problems Solved | References |

|---|---|---|

| DBSCAN and K-means clustering algorithm |

| [46,89] |

| K-means and direct and hierarchical and DPC clustering algorithm |

| [137] |

| K-means clustering algorithm |

| [9,66,69,74,117,118,138,139] |

| PCA algorithm |

| [75,140] |

| Random forest algorithm |

| [119,141] |

| GBDT algorithm |

| [142] |

| Genetic algorithm |

| [10,88] |

| KNN algorithm and logistic regression and SVM |

| [120] |

| Greedy heuristic algorithm |

| [143] |

| Two-stage guided constrained differential evolution algorithm |

| [84] |

| Dynamic Time Warping algorithm |

| [121] |

| Ridge Regression |

| [144] |

| Gradient Boosting algorithm and XGBoost algorithm |

| [145] |

| XGBoost algorithm |

| [146] |

5.3. Applications for EV Charging Big Data

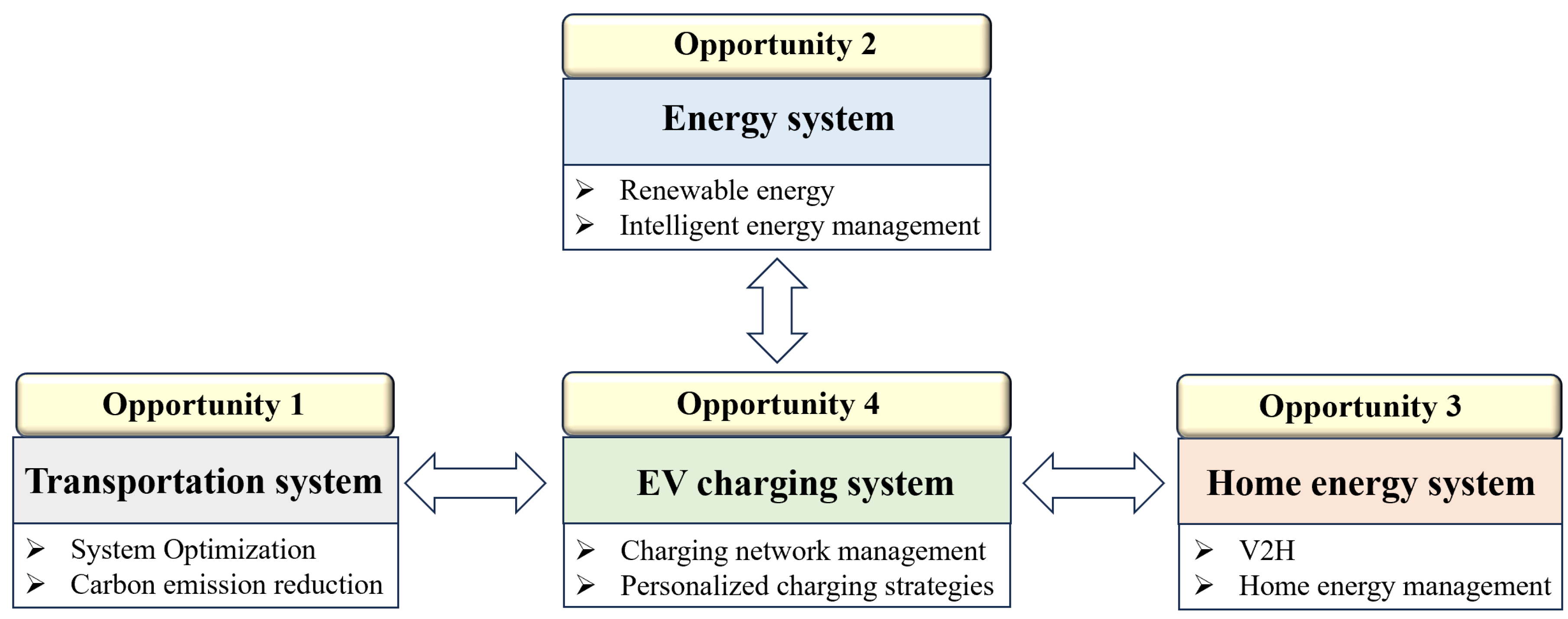

6. Future Research Opportunities

6.1. Opportunity 1: Deep Integration of Intelligent Transportation and Smart Grid

6.2. Opportunity 2: Renewable Energy and Intelligent Energy Management Optimization

6.3. Opportunity 3: Synergizing Smart Homes with EVs

6.4. Opportunity 4: Data-Enabled and User-Driven Smart EV Charging Management

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Ipsos. How to Create a Friendly Environment for EVs and Accelerate Market Adoption? Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2024-06/N200_CEX_How_EVs_Incentives_can_Charge_the_Market_CHN.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z. Energy consumption analysis and prediction of electric vehicles based on real-world driving data. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Son, D.; Jeong, B. Electric vehicle charging scheduling with mobile charging stations. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hu, X.; Sun, J.; Lei, Q.; Zhang, Y. Is it worth promoting battery swapping? A social welfare perspective on provider- and consumer-side incentives. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.S.; Gao, Y.X.; Wu, N.Q.; Zhu, J.W.; Li, H.Z.; Yang, J.H. Optimal scheduling of electric vehicle charging operations considering real-time traffic condition and travel distance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 118941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, E.; Barros, T.A.D.; Ruppert, E. Forecasting urban electric vehicle charging power demand based on travel trajectory simulation in the realistic urban street network. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 4254–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhuge, C.X.; Shao, C.F.; Guo, R.H.; Wong, A.T.C.; Zhang, X.Y.; Sun, M.D.; Wang, P.X.; Wang, S.Q. Dominant charging location choice of commuters and non-commuters: A big data approach. Transportation 2023, 52, 439–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shao, C.; Zhuge, C.; Sun, M.; Wang, P.; Yang, X. Deploying Battery Swap Stations for Electric Freight Vehicles Based on Trajectory Data Analysis. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 3782–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Deng, Z.; Che, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Hu, X. Big field data-driven battery pack health estimation for electric vehicles: A deep-fusion transfer learning approach. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 218, 111585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.W.; Chang, Y.H.; Luo, T.Q.; Lu, B.; Guo, C.D.; Li, Y.C. Integrating particle swarm optimization with convolutional and long short-term memory neural networks for real vehicle data-based lithium-ion battery health estimation. J. Energy Storage 2025, 111, 115427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Peng, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, F.; Jiao, H.; Wang, J. Planning public electric vehicle charging stations to balance efficiency and equality: A case study in Wuhan, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 124, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, A.A.; Mohamed, Y. Unsupervised Nonintrusive Extraction of Electrical Vehicle Charging Load Patterns. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2019, 15, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, F.; Sivakumar, A. Analysing the impact of electric vehicle charging on households: An interrelated load profile generation approach. Energy Build. 2025, 335, 115558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, A.; Ghodrati, V.; Gadh, R. Artificial deep neural network enables one-size-fits-all electric vehicle user behavior prediction framework. Appl. Energy 2023, 352, 121884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.N.; Xing, H.W.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.Y.; Wan, M.C.; Geng, G.C.; Jiang, Q.Y. Real-time estimation of aggregated electric vehicle charging load based on representative meter data. Energy 2025, 321, 135162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Guo, X.P.; Li, Y.; Yang, K. The sequential construction research of regional public electric vehicle charging facilities based on data-driven analysis—Empirical analysis of Shanxi Province. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, B.; Li, T.; Deng, N.; Song, Q.; Zhang, J. Multi-objective electric-carbon synergy optimisation for electric vehicle charging: Integrating uncertainty and bounded rational behaviour models. Appl. Energy 2025, 389, 125790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Lin, X.; Yang, Q. Design and Application of a Fault Diagnosis and Monitoring System for Electric Vehicle Charging Equipment Based on Improved Deep Belief Network. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2022, 20, 1544–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, E.J.; Pan, L. Electric vehicle drivers’ charging behavior analysis considering heterogeneity and satisfaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.T.; Yao, E.J.; Wu, K.Q. Deploying Public Charging Stations for Battery Electric Vehicles on the Expressway Network Based on Dynamic Charging Demand. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 2531–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Wang, W.; Jin, K.; Gu, H. A blockchain-enabled personalized charging system for electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 161, 104549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Peng, Z.H.; Wang, P.X.; Zhuge, C.X. Seasonal variance in electric vehicle charging demand and its impacts on infrastructure deployment: A big data approach. Energy 2023, 280, 128230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbertus, R.; Kroesen, M.; van den Hoed, R.; Chorus, C. Fully charged: An empirical study into the factors that influence connection times at EV-charging stations. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.Z.; Tian, M.; Han, S.W.; Wu, T.Y.; Tang, Y.F. Electric vehicle battery remaining charging time estimation considering charging accuracy and charging profile prediction. J. Energy Storage 2022, 49, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Zhang, W.G.; Sun, B.X.; Zhang, Y.R.; Fan, X.Y.; Zhao, B. A novel method of battery pack energy health estimation based on visual feature learning. Energy 2024, 293, 130656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.D.; Dai, Y.X.; Huang, J.H.; Xu, H.; Lu, L.G.; Han, X.B.; Du, J.Y.; Ouyang, M.G. Charging patterns analysis and multiscale infrastructure deployment: Based on the real trajectories and battery data of the plug-in electric vehicles in Shanghai. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, S. Optimal charging infrastructure planning based on a charging convenience buffer. Energy 2020, 192, 116655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kong, H.; Lin, Z.; Dang, A. Mapping the dynamics of electric vehicle charging demand within Beijing’s spatial structure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Hu, P.; Tan, Z. Research on the effect of large-scale electric vehicle based on smart wearable equipment access to grid. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2018, 10, 3231–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Wang, G.L.; Wang, X.F.; Du, Y.K. Smart charging strategy for electric vehicles based on marginal carbon emission factors and time-of-use price. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Liang, C.D.; Lu, M. Optimal scheduling of electric vehicle ordered charging and discharging based on improved gravitational search and particle swarm optimization algorithm. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 157, 109766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.P.; Singh, M. Time-of-Use tariff rates estimation for optimal demand-side management using electric vehicles. Energy 2023, 273, 127243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.Y.; Liu, Y.P.; Xu, J.; Jia, L.W.; Ke, D.P.; Jiang, X.X. Data-Driven Real-Time Congestion Forecasting and Relief With High Renewable Energy Penetration. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2024, 21, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, Y.W.; Lian, Y.C.; Hao, G.K.; Jiang, L. Data-driven nested robust optimization for generation maintenance scheduling considering temporal correlation. Energy 2023, 278, 127499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Q.L.; Sun, H.B. Integrated pricing framework for optimal power and semi-dynamic traffic flow problem. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2020, 14, 3636–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.J.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, D.H.; Liu, W.N. Dynamic spatial-temporal feature optimization with ERI big data for Short-term traffic flow prediction. Neurocomputing 2020, 412, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, A.; Wang, P.; Zhuge, C. Predicting electric vehicle charging demand using a heterogeneous spatio-temporal graph convolutional network. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 153, 104205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.L.; Wu, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, L.; Tan, Z.Y.; Tian, Z.H. A VMD and LSTM Based Hybrid Model of Load Forecasting for Power Grid Security. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2022, 18, 6474–6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Qian, Q. Optimal placement of parking of electric vehicles in smart grids, considering their active capacity. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 220, 109238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Ly, S.; Wang, P.; Nguyen, H.D. Hypothesis Testing for Mitigation of Operational Infeasibility on Distribution System Under Rising Renewable Penetration. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 876–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.A.E.; Alham, M.H.; Ibrahim, D.K. Big data resolving using Apache Spark for load forecasting and demand response in smart grid: A case study of Low Carbon London Project. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashitani, T.; Ikegami, T.; Uemichi, A.; Akisawa, A. Evaluation of residential power supply by photovoltaics and electric vehicles. Renew. Energy 2021, 178, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Liu, C.; Jalili, M.; Yu, X.H.; McTaggart, P. Ensemble Classification Model for EV Identification From Smart Meter Recordings. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2023, 19, 3274–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Zhou, K.; Li, F.; Ma, D. Electric vehicle user classification and value discovery based on charging big data. Energy 2022, 249, 123698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, H.; Xiong, J.; Kato, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Smart and Resilient EV Charging in SDN-Enhanced Vehicular Edge Computing Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2020, 38, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrenacci, N.; Ragona, R.; Genovese, A. Evaluation of the Instantaneous Power Demand of an Electric Charging Station in an Urban Scenario. Energies 2020, 13, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevec, D.; Babic, J.; Podobnik, V. Electric Vehicles: A Data Science Perspective Review. Electronics 2019, 8, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.; Al-Ali, A.R.; Osman, A.H.; Dhou, S.; Nijim, M. Machine Learning Approaches for EV Charging Behavior: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 168980–168993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappeta, V.S.R.; Appasani, B.; Patnaik, S.; Ustun, T.S. A Review on Emerging Communication and Computational Technologies for Increased Use of Plug-In Electric Vehicles. Energies 2022, 15, 6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.A.; Fanti, M.P.; Roccotelli, M.; Ranieri, L. A Review of Digital Twin Technology for Electric and Autonomous Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mololoth, V.K.; Saguna, S.; Ahlund, C. Blockchain and Machine Learning for Future Smart Grids: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.N.; Hemmati, M.; Miraftabzadeh, S.M.; Mohammadi, Y.; Bayati, N. A Mini Review of the Impacts of Machine Learning on Mobility Electrifications. Energies 2024, 17, 6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M.; Dissanayake, D.; Bell, M. Next Generation of Electric Vehicles: AI-Driven Approaches for Predictive Maintenance and Battery Management. Energies 2025, 18, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhou, X.; Bao, Z.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Fang, W. Artificial intelligence in infrastructure construction: A critical review. Front. Eng. Manag. 2025, 12, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; Feng, D.; Habib, S.; Numan, M.; Rahman, U. A heuristically optimized comprehensive charging scheme for large-scale EV integration. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2020, 30, e12313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.; Cui, Y.; Sun, J.; Peng, H. On-board state of health monitoring of lithium-ion batteries using incremental capacity analysis with support vector regression. J. Power Sources 2013, 235, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, D.; Khan, M.A.; Khosravi, N.; Waseem, M.; Ahmed, H. A review of energy storage systems for facilitating large-scale EV charger integration in electric power grid. J. Energy Storage 2025, 112, 115496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaraju, I. Fractional order Adaptive Integral Hierarchical Sliding Mode Controller for Energy Management System in Electric Vehicles. J. New Mater. Electrochem. Syst. 2025, 28, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, W.; Chau, K.T.; Hou, Y.; Guo, J. Stochastic Behavior Modeling and Optimal Bidirectional Charging Station Deployment in EV Energy Network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 6231–6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, Å.L.; Sartori, I.; Lindberg, K.B.; Andresen, I. A method for generating complete EV charging datasets and analysis of residential charging behaviour in a large Norwegian case study. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2023, 36, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile-Ardanuy, J.; Castano-Solis, S.; Álvaro-Hermana, R.; Merino, J.; Castillo, Á. Using mobility information to perform a feasibility study and the evaluation of spatio-temporal energy demanded by an electric taxi fleet. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 157, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, J.; Dang, A.; Liao, L.; Xu, M. Emission pattern mining based on taxi trajectory data in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, T.; Huang, X.; Wang, H. Urban Electric Vehicle Fast-Charging Demand Forecasting Model Based on Data-Driven Approach and Human Decision-Making Behavior. Energies 2020, 13, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, S.; Min, L.; Feng, Y.; Hang, Z.; Shi, L. Energy Storage Charging Pile Management Based on Internet of Things Technology for Electric Vehicles. Processes 2023, 11, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyrazoglu, G.; Coban, E. A stochastic value estimation tool for electric vehicle charging points. Energy 2021, 227, 120335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, A.; Pan, A.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Liao, Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z. A real-world investigation into usage patterns of electric vehicles in Shanghai. J. Energy Storage 2020, 32, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenig, J.; Sodenkamp, M.; Staake, T. Battery versus infrastructure: Tradeoffs between battery capacity and charging infrastructure for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2019, 255, 113787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Tian, Y.; Tian, J. Energy Consumption Estimation for Electric Buses Based on a Physical and Data-Driven Fusion Model. Energies 2022, 15, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, A.; Wang, P.; Zhuge, C. Short-term electric vehicle battery swapping demand prediction: Deep learning methods. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 119, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xydas, E.; Marmaras, C.; Cipcigan, L.M.; Jenkins, N.; Carroll, S.; Barker, M. A data-driven approach for characterising the charging demand of electric vehicles: A UK case study. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyo, V. Behavior-Neutral Smart Charging of Plugin Electric Vehicles: Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64095–64104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.; Xue, L. Analyzing Charging Behavior of Electric City Buses in Typical Chinese Cities. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 4466–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.P.; Liu, C. Data Compression and Reconstruction for EV Charging Stations Based on Principal Component Analysis. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 556–562, 4317–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yu, J. Identification of charging behavior characteristic for large-scale heterogeneous electric vehicle fleet. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2017, 6, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawale, S.A.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, P.; Kolhe, M.L. Priority Wise Electric Vehicle Charging for Grid Load Minimization. Processes 2022, 10, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, M.B.; Bae, S. Electric vehicle charging demand forecasting model based on big data technologies. Appl. Energy 2016, 183, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Hu, B.; Xie, K.; Tang, J.; Tai, H.-M. An EV Charging Demand Model for the Distribution System Using Traffic Property. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 28089–28099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Cao, J.; Fang, C.; Li, D. 6G Based Intelligent Charging Management for Autonomous Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 7574–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Xiong, Y.; Hu, X. Research on Planning and Layout of Electric Vehicle Public Charging Piles in Historical and Cultural Street Based on Big Data. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 510, 062026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.Y.; Yu, H.; Niu, S.X.; Jian, L.N. Power loss analysis and thermal assessment on wireless electric vehicle charging technology: The over-temperature risk of ground assembly needs attention. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.Y.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Chen, H.B.; Niu, S.X.; Jian, L.N. Noncooperative Metal Object Detection Using Pole-to-Pole EM Distribution Characteristics for Wireless EV Charger Employing DD Coils. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 6335–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, T.-W.; Li, W.; Liang, Q.; Hong, C.; Fang, Q. Research on charging behavior of electric vehicles based on multiple objectives. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 15708–15736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clack, C.T.M.; Qvist, S.A.; Apt, J.; Bazilian, M.; Brandt, A.R.; Caldeira, K.; Davis, S.J.; Diakov, V.; Handschy, M.A.; Hines, P.D.H.; et al. Evaluation of a proposal for reliable low-cost grid power with 100% wind, water, and solar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6722–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shui, D.Y.; Xie, Y.; Wu, L.B.; Liu, Y.N.; Su, X. Lightweight three-party key agreement for V2G networks with physical unclonable function. Veh. Commun. 2024, 47, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Shao, C.; Zhuge, C.; Wang, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, S. Exploring the potential of rental electric vehicles for vehicle-to-grid: A data-driven approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Li, Q.; Fang, Z.; Shaw, S.-l.; Zhou, B.; Chang, X. Optimizing the locations of electric taxi charging stations: A spatial–temporal demand coverage approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 65, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, C.; Wan, T. Planning of the Charging Station for Electric Vehicles Utilizing Cellular Signaling Data. Sustainability 2019, 11, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Peng, Z.H.; Liu, L.B.; Wu, H. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Electric Vehicle Charging Based on Multisource Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Xu, N. Spatial adaptability evaluation and optimal location of electric vehicle charging stations: A win-win view from urban travel dynamics. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2023, 49, 101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.M.; Rong, J.F.; Zhang, J.M.; Liu, C.R.; Yi, F.Y.; Jiao, Z.P.; Zhang, C.Z. Deep learning estimation of state of health for lithium-ion batteries using multi-level fusion features of discharge curves. J. Power Sources 2025, 653, 237781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, G.; Diao, W.; Zhang, W. Study on battery pack consistency evolutions and equilibrium diagnosis for serial- connected lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Energy 2017, 207, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Song, C. Detection of voltage fault in the battery system of electric vehicles using statistical analysis. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Fu, P.; Yin, H.; Xie, W.; Feng, S. A Study of Online State-of-Health Estimation Method for In-Use Electric Vehicles Based on Charge Data. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2019, E102.D, 1302–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Liang, T.; Lu, L.; Ouyang, M. Lithium-ion battery pack equalization based on charging voltage curves. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 115, 105516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, B.; Zhao, X.; Ma, S. Capacity estimation for series-connected battery pack based on partial charging voltage curve segments. J. Energy Storage 2024, 95, 112576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Chau, K.T. Deep reinforcement learning-based energy management strategy for fuel cell buses integrating future road information and cabin comfort control. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.C.; Liu, W.; He, H.W.; Chau, K.T. Health-conscious energy management for fuel cell vehicles: An integrated thermal management strategy for cabin and energy source systems. Energy 2025, 333, 137330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, Q.Y.; Qu, H.Q.; Wang, M.S.; Wu, Y.L.; Ge, L. Dynamic pricing for fast charging stations with deep reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 2023, 346, 121334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, C.; Li, Y. Dynamic pricing based electric vehicle charging station location strategy using reinforcement learning. Energy 2023, 281, 128284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Lee, C.K.M. Dynamic Pricing for EV Charging Stations: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 2456–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.B.; Wu, J.A.; Cui, J.S.; Xu, Y.Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Gonzalez, M.C. Deadline Differentiated Dynamic EV Charging Price Menu Design. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. Price-responsive early charging control based on data mining for electric vehicle online scheduling. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2019, 167, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Huang, Y.F.; Gupta, V. Stochastic Dynamic Pricing for EV Charging Stations With Renewable Integration and Energy Storage. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 1494–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Kulcsár, B.; Gros, S. Personalized dynamic pricing policy for electric vehicles: Reinforcement learning approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 161, 104540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lv, Z.; Wang, W. Detecting Anomalies in Intelligent Vehicle Charging and Station Power Supply Systems With Multi-Head Attention Models. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Z.; Zou, Z.H.; Liu, Y.L.; Zeng, Z.Y.; Zhou, S.; Jin, T. Deep Learning-Based Multifeature Fusion Model for Accurate Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis in Electric Vehicle DC Charging Piles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 2243–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Min, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. A Method for Abnormal Battery Charging Capacity Diagnosis Based on Electric Vehicles Operation Data. Batteries 2023, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kwon, D.; Han, J.; Lee, S.M.; Elkosantini, S.; Suh, W. Data-Driven Model for Identifying Factors Influencing Electric Vehicle Charging Demand: A Comparative Analysis of Early- and Maturity-Phases of Electric Vehicle Programs in Korea. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.X.; Deng, Y.L. Federated learning-based prediction of electric vehicle battery pack capacity using time-domain and frequency-domain feature extraction. Energy 2025, 319, 135002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, D.; Li, W.; Liu, J. Unraveling influencing factors of public charging station utilization. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 137, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, S.; Moon, H.; Woo, J. Analyzing heterogeneous electric vehicle charging preferences for strategic time-of-use tariff design and infrastructure development: A latent class approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 374, 124074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Gan, Q.; Shaker, M.P. Optimal management of parking lots as a big data for electric vehicles using internet of things and Long–Short term Memory. Energy 2023, 268, 126613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fescioglu-Unver, N.; Yıldız Aktaş, M. Electric vehicle charging service operations: A review of machine learning applications for infrastructure planning, control, pricing and routing. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2023, 188, 113873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Huang, A.; Cui, H.; Yu, R.; Peng, X. Spatial heterogeneity analysis on distribution of intra-city public electric vehicle charging points based on multi-scale geographically weighted regression. Travel Behav. Soc. 2024, 35, 100725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, H.; Xie, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, R. Research on the Dispatching of Electric Vehicles Participating in Vehicle-to-Grid Interaction: Considering Grid Stability and User Benefits. Energies 2024, 17, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrenacci, N.; Ragona, R.; Valenti, G. A demand-side approach to the optimal deployment of electric vehicle charging stations in metropolitan areas. Appl. Energy 2016, 182, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Hu, C. Research on Big Data Mining Technology of Electric Vehicle Charging Behaviour. Elektron. Elektrotechnika 2019, 25, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Albuquerque, V.; Ferreira, J.C.; Dias, M.S. EV Battery Degradation: A Data Mining Approach. In Intelligent Transport Systems, Proceedings of the 5th EAI International Conference, INTSYS 2021, Virtual Event, 24–26 November 2021; Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Hwang, H.; Kim, D.; Cui, S.; Joe, I. Real Driving Cycle-Based State of Charge Prediction for EV Batteries Using Deep Learning Methods. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skala, R.; Elgalhud, M.A.T.A.; Grolinger, K.; Mir, S. Interval Load Forecasting for Individual Households in the Presence of Electric Vehicle Charging. Energies 2023, 16, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhao, C. iEVEM: Big Data-Empowered Framework for Intelligent Electric Vehicle Energy Management. Systems 2025, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.S.; Zheng, C.; Shaheen, S.; Kammen, D.M. Leveraging Big Data and Coordinated Charging for Effective Taxi Fleet Electrification: The 100% EV Conversion of Shenzhen, China. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 10343–10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Santi, P.; Zhao, T.; He, X.; Li, Q.; Dong, L.; Wallington, T.J.; Ratti, C. Acceptability, energy consumption, and costs of electric vehicle for ride-hailing drivers in Beijing. Appl. Energy 2019, 250, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrenacci, N.; Genovese, A.; Ragona, R. Determination of the level of service and customer crowding for electric charging stations through fuzzy models and simulation techniques. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Yao, E.; MacKenzie, D. Modeling EV charging choice considering risk attitudes and attribute non-attendance. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 102, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Z.-J.M.; Zhang, L.; Dorrell, D.G.; Sun, F. Big data-driven decoupling framework enabling quantitative assessments of electric vehicle performance degradation. Appl. Energy 2022, 327, 120083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, J.; Roberts, D.; Glitman, K. A comparison of electric vehicle Level 1 and Level 2 charging efficiency. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech), Portland, OR, USA, 24–26 July 2014; pp. 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- De Gennaro, M.; Paffumi, E.; Martini, G. Customer-driven design of the recharge infrastructure and Vehicle-to-Grid in urban areas: A large-scale application for electric vehicles deployment. Energy 2015, 82, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.Q.; Yadav, A.; Khan, A.; Liu, H.; Haq, A.U. Application of Big Data Fusion Based on Cloud Storage in Green Transportation: An Application of Healthcare. Sci. Program. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Shao, C.; Zhuge, C.; Wang, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, S. Uncovering travel and charging patterns of private electric vehicles with trajectory data: Evidence and policy implications. Transport. 2021, 49, 1409–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Dorrell, D.G.; Li, X. Battery electric vehicle usage pattern analysis driven by massive real-world data. Energy 2022, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezugwu, A.E.; Ikotun, A.M.; Oyelade, O.O.; Abualigah, L.; Agushaka, J.O.; Eke, C.I.; Akinyelu, A.A. A comprehensive survey of clustering algorithms: State-of-the-art machine learning applications, taxonomy, challenges, and future research prospects. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 110, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speiser, J.L.; Miller, M.E.; Tooze, J.; Ip, E. A comparison of random forest variable selection methods for classification prediction modeling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 134, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboudi, Z.; Chikhi, S. Comparison of Genetic Algorithm and Quantum Genetic Algorithm. Int. Arab. J. Inf. Technol. 2012, 9, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Luo, W.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, H.; Yu, Q. Research on EV loads clustering analysis method for source-grid-load system. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choumal, A.; Rizwan, M.; Jha, S. Big data analytics for photovoltaic and electric vehicle management in sustainable grid integration. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2025, 17, 016102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenimanesh, A.; Entchev, E. Charging Strategies for Electric Vehicles Using a Machine Learning Load Forecasting Approach for Residential Buildings in Canada. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, R.; Monopoli, T.; Zampolli, M.; Jaboeuf, R.J.P.; Tosco, P.; Patti, E.; Aliberti, A. A Novel Procedure for Real-Time SOH Estimation of EV Battery Packs Based on Time Series Extrinsic Regression. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Asadi, A.; Yang, K.; Maitra, A.; Asgeirsson, H. Analyzing household charging patterns of Plug-in electric vehicles (PEVs): A data mining approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 128, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Lin, H.; Chen, X.; Xie, K.; Shan, X. Modeling Usage Frequencies and Vehicle Preferences in a Large-Scale Electric Vehicle Sharing System. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2022, 14, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Fei, X.; Li, J.; He, X.; Gu, H. Location of Electric Vehicle Charging Piles Based on Set Coverage Model. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, S.; Radha, R.; Prakash, P.A.; Nandhini, R. Optimizing the Selection of Intermediate Charging Stations in EV Routing Through Neuro-Fuzzy Logic. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 140021–140038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghian, S.; Doan, T.N.; Knox, J.; Harris, A.; Sartipi, M. Data-Driven Insights Into EV Charging Patterns: Machine Learning Models Reveal Key Predictors of Station Utilization in Tennessee. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 51458–51483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, G.S.A.; Priya, P.S.L.; Jayan, J.; Satheesh, R.; Kolhe, M.L. Data-Driven Energy Management of an Electric Vehicle Charging Station Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 65956–65966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.-S.; Oh, E.; Son, S.-Y. Study on EV Charging Peak Reduction with V2G Utilizing Idle Charging Stations: The Jeju Island Case. Energies 2018, 11, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Song, H.; Kaiwartya, O.; Zhou, B.; Zhuang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X. Mobile Edge Computing for Big-Data-Enabled Electric Vehicle Charging. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhuge, C.; Shao, C.; Wang, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, S. Short-term electric vehicle charging demand prediction: A deep learning approach. Appl. Energy 2023, 340, 121032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.; Moreira, J.; Costa, R.L.d.C. Logical big data integration and near real-time data analytics. Data Knowl. Eng. 2023, 146, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Pan, S.; Wang, J.; Vasilakos, A.V. Machine learning on big data: Opportunities and challenges. Neurocomputing 2017, 237, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Gong, Y. ChatGPT, AI-generated content, and engineering management. Front. Eng. Manag. 2024, 11, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liu, P. Battery Safety Risk Assessment in Real-World Electric Vehicles Based on Abnormal Internal Resistance Using Proposed Robust Estimation Method and Hybrid Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 7661–7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Song, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, P.; Dorrell, D.G. A Data-Driven Method for Battery Charging Capacity Abnormality Diagnosis in Electric Vehicle Applications. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.P.; Zhao, J.Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.B.; Lian, Y.B.; Burke, A.F. Spatial-Temporal Self-Attention Transformer Networks for Battery State of Charge Estimation. Electronics 2023, 12, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Eze, C.; Wang, J.; Lian, Y.; Burke, A.F. Cloud-Based Deep Learning for Co-Estimation of Battery State of Charge and State of Health. Energies 2023, 16, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Jia, H.; Mu, Y.; Yu, X.; Dong, X.; Deng, Y. Coordinated Planning of Fixed and Mobile Charging Facilities for Electric Vehicles on Highways. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 10087–10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würtz, S.; Bogenberger, K.; Göhner, U. Big Data and Discrete Optimization for Electric Urban Bus Operations. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2022, 2677, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Streimikiene, D.; Fomina, A.; Semenova, E. Internet of Energy (IoE) and High-Renewables Electricity System Market Design. Energies 2019, 12, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borozan, S.; Giannelos, S.; Strbac, G. Strategic network expansion planning with electric vehicle smart charging concepts as investment options. Adv. Appl. Energy 2022, 5, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagaria, S.; van der Kam, M.; Boström, T. Vehicle-to-grid impact on battery degradation and estimation of V2G economic compensation. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffash, S.; Nguyen, A.T.; Zhu, J. Big data algorithms and applications in intelligent transportation system: A review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 231, 107868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dileep, G. A survey on smart grid technologies and applications. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 2589–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Z.; Yang, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhan, X.P.; Liao, S.Y.; Xu, J.; Fan, H.; Liang, J.F. Cascading failure in coupled networks of transportation and power grid. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 140, 108058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.I.; Fu, Z.; Apostolaki-Iosifidou, E.; Lipman, T.E. Evaluating smart charging strategies using real-world data from optimized plugin electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 100, 103023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalrahman, A.; Zhuang, W.H. PEV Charging Infrastructure Siting Based on Spatial-Temporal Traffic Flow Distribution. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 6115–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.F.; Yuan, F.M.; Zhai, H.P.; Song, C. Multifactor and multiscale method for power load forecasting? Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 268, 110476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Lund, H.; Liang, Y.T. The electrification of transportation in energy transition. Energy 2021, 236, 121564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission; National Energy Administration; Ministry of Industry and Information Technology; The State Administration for Market Regulation. Implementation Opinions of the National Development and Reform Commission and Other Departments on Strengthening the Integrated Interaction Between New Energy Vehicles and the Power Grid. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202401/content_6924347.htm (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- ICCT. Regional Charging Infrastructure Requirements in Germany Through 2030. Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/germany-charging-infrastructure-20201021.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Wen, Y.; Wu, R.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Wallington, T.J.; Shen, W.; Tan, Q.; Deng, Y.; Wu, Y. A data-driven method of traffic emissions mapping with land use random forest models. Appl. Energy 2022, 305, 117916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, R.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Du, Y.T.; Yang, Y.T. Monitoring the enterprise carbon emissions using electricity big data: A case study of Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 396, 136427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Lian, S.; Zeng, J.; Geng, M.; Zheng, S.; Dong, Y.; He, Y.; Huang, P.; et al. Multi-scale urban passenger transportation CO2 emission calculation platform for smart mobility management. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ren, H.; Wu, Q.; Li, Q.; Gao, W. Cooperative economic dispatch of EV-HV coupled electric-hydrogen integrated energy system considering V2G response and carbon trading. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaps, C.; Marinesi, S.; Netessine, S. When Should the Off-Grid Sun Shine at Night? Optimum Renewable Generation and Energy Storage Investments. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 7633–7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, G.S.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Jamei, E.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S.; Stojcevski, A. Role of optimization techniques in microgrid energy management systems—A review. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2022, 43, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenar-Santos, A.; Muñoz-Gómez, A.-M.; Rosales-Asensio, E.; López-Rey, Á. Electric vehicle charging strategy to support renewable energy sources in Europe 2050 low-carbon scenario. Energy 2019, 183, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massana, J.; Burgas, L.; Herraiz, S.; Colomer, J.; Pous, C. Multi-vector energy management system including scheduling electrolyser, electric vehicle charging station and other assets in a real scenario. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, S.E.; Homer, J.S.; Orrell, A.C. Valuing wind as a distributed energy resource: A literature review. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., The Core Writing Team, Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Essayeh, C.; Morstyn, T. Aggregated Feasible Active Power Region for Distributed Energy Resources With a Distributionally Robust Joint Probabilistic Guarantee. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dippenaar, J.A.; Bekker, B. Understanding interconnection rule non-compliance: Lessons from South Africa’s surge in unauthorised distributed energy resources. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 85, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Li, Q.X.; Zhu, Y.L.; Shan, Z.J.; Ye, H.D.; Xu, C.B.; Dong, H.X. A hierarchical co-optimal planning framework for microgrid considering hydrogen energy storage and demand-side flexibilities. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Masrur, H.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Howlader, H.O.R.; Gamil, M.M.; Nakadomari, A.; Mandal, P.; Senjyu, T. Multi-objective optimization of campus microgrid system considering electric vehicle charging load integrated to power grid. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strezoski, L.; Stefani, I. Enabling mass integration of electric vehicles through distributed energy resource management systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 157, 109798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.B.; Zheng, K.D.; Gu, Y.X.; Wang, J.X.; Chen, Q.X. Optimal Energy Dispatch of Grid-Connected Electric Vehicle Considering Lithium Battery Electrochemical Model. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 3000–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.T.; Shang, Y.M.; Yu, H.; Shao, Z.Y.; Jian, L.N. Achieving Efficient and Adaptable Dispatching for Vehicle-to-Grid Using Distributed Edge Computing and Attention-Based LSTM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2022, 18, 6915–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.W.; Khazaei, J.; Freihaut, J.D. Optimal integration of Vehicle to Building (V2B) and Building to Vehicle (B2V) technologies for commercial buildings. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2022, 32, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.A.; Numan, M.; Tahir, H.; Rahman, U.; Khan, M.W.; Iftikhar, M.Z. A comprehensive overview of vehicle to everything (V2X) technology for sustainable EV adoption. J. Energy Storage 2023, 74, 109304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, B.; Slama, S.A.B. PV-EV integrated home energy management using vehicle-to-home (V2H) technology and household occupant behaviors. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2022, 44, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Vijayananth, V.; Perumal, T. Smart home energy prediction framework using temporal Kolmogorov-Arnold transformer. Energy Build. 2025, 335, 115529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhar, S.K.; Sethi, S.; Kamble, S.S.; Mathew, S.; Belhadi, A. Artificial intelligence and machine learning-based decision support system for forecasting electric vehicles’ power requirement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 204, 123396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, R.; Carvajal, G.; Guerra-Vallejos, E.; Ramírez, G. Techno-economic evaluation of a vehicle to home and time of use tariff scheme to promote the adoption of electric vehicles in Chile. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Aziz, S.M.; Haque, M.H. Vehicle-to-home operation and multi-location charging of electric vehicles for energy cost optimisation of households with photovoltaic system and battery energy storage. Renew. Energy 2024, 221, 119729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostado-Véliz, M.; León-Japa, R.S.; Jurado, F. Optimal electrification of off-grid smart homes considering flexible demand and vehicle-to-home capabilities. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajalal, M.; Boden, A.; Stevens, G. ForecastExplainer: Explainable household energy demand forecasting by approximating shapley values using DeepLIFT. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, D.; Uçkun, C. Dynamic Electricity Pricing to Smart Homes. Oper. Res. 2019, 67, 1520–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, S.; Vianna Cezar, G.; Apostolaki-Iosifidou, E.; Rajagopal, R. Large-scale scenarios of electric vehicle charging with a data-driven model of control. Energy 2022, 248, 123592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, N.B.; Sabillón, C.; Franco, J.F.; Quirós-Tortós, J.; Rider, M.J. Hierarchical Optimization for User-Satisfaction-Driven Electric Vehicles Charging Coordination in Integrated MV/LV Networks. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.X.; Zhao, D.T.; Li, Y.H. Comparing Mini and full-size electric vehicles in China: Evidence from user heterogeneity and satisfaction asymmetry. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.N.; Jiang, Y.D.; Yu, S.Y.; Qiu, J.D.; Li, H.T.; Sheng, W.X. Non-dominated sorting WOA electric vehicle charging station siting study based on dynamic trip chain. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 244, 111532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menos-Aikateriniadis, C.; Sykiotis, S.; Georgilakis, P.S. Unlocking the potential of smart EV charging: A user-oriented control system based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 230, 110255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Timeline | Number of Papers | Core Focus | EV Charging Ecosystem |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pevec et al. [49] | 2011–2018 | 96 | Exploring research on EVs from the perspectives of social economy (market acceptance, sales forecasting) and social technology (batteries, charging facilities, Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G)) | Fragmentation analysis of various parts of the EV charging ecosystem |

| Shahriar et al. [50] | 2010–2020 | 96 | Machine Learning (ML) methods in EV charging behavior (mainly applied in analysis and prediction) | Fragmented discussion from a technical perspective |

| Tappeta et al. [51] | 2011, 2013–2022 | 130 | The protocols, standards, emerging communication and computing technologies emerging in EVs | Fragmented application of computational technology in EV charging systems |

| Ali et al. [52] | 2018–2022 | 86 | Application of digital twin technology in EVs and autonomous vehicles | Focusing on technical analysis of EVs, charging infrastructure, and power grids |

| Mololoth et al. [53] | 2011–2014, 2016–2022 | 123 | Research on the application of blockchain technology and ML in smart grids | Discussing EVs and the power grid |

| Ali et al. [54] | 2015–2024 | 120 | Review the impact, application, and models of ML/Deep Learning (DL) in the field of mobile electrification | Isolation analysis of various parts of the EV charging ecosystem from ML/DL perspective |

| Cavus et al. [55] | 2010–2016, 2018–2024 | 123 | Exploring the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology in battery management Systems and system control technologies for EVs | Focusing on the optimization and technological application of EVs |

| Category | Application in EV Charging | Machine Learning Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Grid |

| Hybrid Neural Network | [80] |

| LSTM and Bayesian Neural Networks | [122] | |

| Battery |

| LSTM, GRU, Bi-LSTM and Bi-GRU | [71] |

| Hybrid Neural Network | [153] | |

| LSTM | [121] | |

| XGBoost regression model | [154] | |

| K-means algorithm | [94] | |

| Charging Infrastructure |

| Multiple Head Attention model | [107] |

| Deep Belief Network | [20] | |

| Deep Reinforcement Learning | [47] | |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Feedforward Neural Network (FNN) | [111] | |

| XGBoost regression | [123] | |

| Particle Swarm Optimization and CNN and LSTM | [12] | |

| Gaussian process Regression | [11] | |

| Transformer | [155] | |

| Transformer | [156] | |

| EV |

| LSTM | [149] |

| Iterative extended Gaussian process regression-Kalman filter | [95] | |

| CatBoost Decision Tree Model | [70] | |

| Reinforcement Learning | [73] | |

| Driver |

| Heterogeneous spatio-temporal graph convolutional network | [39] |

| LSTM | [114] | |

| Decision Tree | [78] | |

| Binary Logic Model | [110] | |

| Gradient Hoist Model | [124] | |

| K-means clustering | [125] | |

| Fuzzy model | [126] | |

| Hybrid Choice model | [127] | |

| Gradient Boosting Decision Tree | [142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, L.; Liu, M.; Gong, K.; Jiao, L.; Huo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. The Usage of Big Data in Electric Vehicle Charging: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2025, 18, 5066. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18195066

Wu L, Liu M, Gong K, Jiao L, Huo X, Zhang Y, Wang H. The Usage of Big Data in Electric Vehicle Charging: A Comprehensive Review. Energies. 2025; 18(19):5066. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18195066

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Liu, Min Liu, Ke Gong, Liudan Jiao, Xiaosen Huo, Yu Zhang, and Hao Wang. 2025. "The Usage of Big Data in Electric Vehicle Charging: A Comprehensive Review" Energies 18, no. 19: 5066. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18195066

APA StyleWu, L., Liu, M., Gong, K., Jiao, L., Huo, X., Zhang, Y., & Wang, H. (2025). The Usage of Big Data in Electric Vehicle Charging: A Comprehensive Review. Energies, 18(19), 5066. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18195066