Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Geographical Focus: Poland and Sweden were chosen as case studies due to their contrasting approaches to energy transition and poverty alleviation. Poland, heavily reliant on coal for its energy needs, presents a sharp contrast to Sweden, which has developed a highly advanced renewable energy infrastructure. These differences provide a rich basis for analyzing energy poverty across varying contexts.

- Economic and Social Indicators: The countries were selected due to their distinct energy production models. Poland’s economy has long depended on coal as a primary energy source, while Sweden is recognized for its extensive use of renewable energy, making these economic and social factors critical to the study’s framework.

- Energy Poverty Alleviation Policies: The paper examines the national policies in Poland and Sweden that specifically target energy poverty reduction, allowing for a comparative analysis of their effectiveness and outcomes.

- Sources and Literature: The literature and studies included in the review were selected based on their relevance to energy poverty, the impacts of policy interventions, and their empirical approach to measuring the outcomes of energy transitions in these two countries.

3. Results

Energy Poverty Alleviation in Poland and Sweden

- It has a low income;

- It incurs high energy-related expenses;

- It resides in a dwelling or building with low energy efficiency [22].

- -

- combustion of fossil fuels,

- -

- Nox and SO2 emissions

- -

- In turn, the end customer pays for the following:

- -

- energy tax (close to the price of energy),

- -

- a fee for ordered power,

- -

- a fee for the energy consumed,

- -

- an additional small fee for the promotion of green energy,

- -

- and finally VAT on the total amount

- -

- Strengthen financial support policies: It is important for the government to continue and expand support programs for households, especially low-income households that are most vulnerable to energy poverty. These could include subsidies for improving the energy efficiency of homes, which would reduce heating and electricity costs.

- -

- Education and awareness: Increasing public awareness of energy saving and available sources of support is key. Education about how to use energy efficiently can help lower energy bills.

- -

- Energy price dynamics: Allowing more flexible energy prices that reflect supply and demand can help stabilize costs. At the same time, efforts should be made to avoid a situation where households with limited resources cannot take advantage of dynamic pricing models.

- -

- Promoting renewable energy sources: Investment in renewable energy can help lower overall energy costs, as well as improve energy security. The government should promote renewable energy installations at the local level.

- -

- Crisis interventions: With energy prices rising due to global crises, it is important for the government to have intervention programs ready to quickly support the neediest households.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouzarovski, S. Energy Poverty in the European Union: Landscapes of Vulnerability. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2014, 3, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, B. Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth; Pinter Pub Limited: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia, J.P.; Bessa, S.; Palma, P.; Mahoney, K.; Sequeira, M. EPAH Energy Poverty National Indicators: Uncovering New Possibilities for Expanded Knowledge; Energy Poverty Advisory Hub: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://energy-poverty.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2024-05/EPAH2023_2nd%20Indicators%20Report_Final_0_0.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- International Energy Agency; International Renewable Energy Agency; United Nations Statistics Division; World Bank; World Health Organization. Tracking SDG 7—The Energy Progress Report 2022; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/bcdf24b0-4bd1-5d9f-9140-97825fec0598 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- World Bank. Report: Universal Access to Sustainable Energy Will Remain Elusive Without Addressing Inequalities; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/06/07/report-universal-access-to-sustainable-energy-will-remain-elusive-without-addressing-inequalities (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M. Access to Energy; Our World in Data. 2019. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/energy-access (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Pachauri, S.; Spreng, D. Measuring and Monitoring Energy Poverty. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7497–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, K.M.; Spitzer, M.; Christanell, A. Experiencing Fuel Poverty: Coping Strategies of Low-Income Households in Vienna, Austria. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Popke, J. “Because You Got to Have Heat”: The Networked Assemblage of Energy Poverty in Eastern North Carolina. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2011, 101, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, V.; Tre, J.-P.; Wodon, Q. Energy Consumption and Income: An Inverted U at the Household Level? Econ. Lett. 2000, 68, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Buzar, S. Energy Poverty in Eastern Europe: Hidden Geographies of Deprivation; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S.; Sarlamanov, R. Energy Poverty Policies in the EU: A Critical Perspective. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; O’Keeffe, Z.P.; Abidoye, B.; Gaba, K.M.; Monroe, T.; Stewart, B.P.; Baugh, K.; Sánchez-Andrade Nuño, B. Lost in the Dark: A Survey of Energy Poverty from Space. Joule 2024, 8, 1982–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemiss, L.; Gillard, R. Fuel Poverty from the Bottom-Up: Characterizing Household Energy Vulnerability through the Lived Experience of the Fuel Poor. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, D.; Kahouli, S. From Residential Energy Demand to Fuel Poverty: Income-Induced Non-Linearities in the Reactions of Households to Energy Price Fluctuations. Energy J. 2019, 40, 101–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njiru, C.W.; Letema, S.C. Energy Poverty and Its Implication on Standard of Living in Kirinyaga, Kenya. J. Energy 2018, 2018, 3196567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristondo, O.; Onaindia, E. Counting Energy Poverty in Spain between 2004 and 2015. Energy Policy 2018, 113, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1563 of 14 October 2020 on Energy Poverty. Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, L357, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Igawa, M.; Managi, S. Energy Poverty and Income Inequality: An Economic Analysis of 37 Countries. Appl. Energy 2022, 306, 118076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, C.E.; Kammen, D.M. The Energy-Poverty-Climate Nexus. Science 2010, 330, 1181–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Eguino, M. Energy Poverty: An Overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland. Energy Law, August 24, 2024, Art. 5; Dziennik Ustaw. 2024. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19970540348/U/D19970348Lj.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- European Commission. State of the Energy Union Report 2023—Country Fiches; European Union: 2023. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Boguszewski, R.; Herudziński, T. Ubóstwo Energetyczne w Polsce; Pracownia Badań Społecznych SGGW: Warszawa, Polska, 2018; pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Owczarek, D. (Nie)równy Ciężar Ubóstwa Energetycznego Wśród Kobiet i Mężczyzn w Polsce; ClientEarth: Warszawa, Polska, 2016; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, A.K.N. Energy and Social Issues. In World Energy Assessment: Energy and the Challenge of Sustainability; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Halkos, G.; Gkampoura, E.-C. Evaluating the Effect of Economic Crisis on Energy Poverty in Europe. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2021, 144, 110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardazzi, R.; Bortolotii, L.; Pazienza, M.G. To Eat and Not to Heat? Energy Poverty and Income Inequality in Italian Regions. Soc. Sci. 2021, 73, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

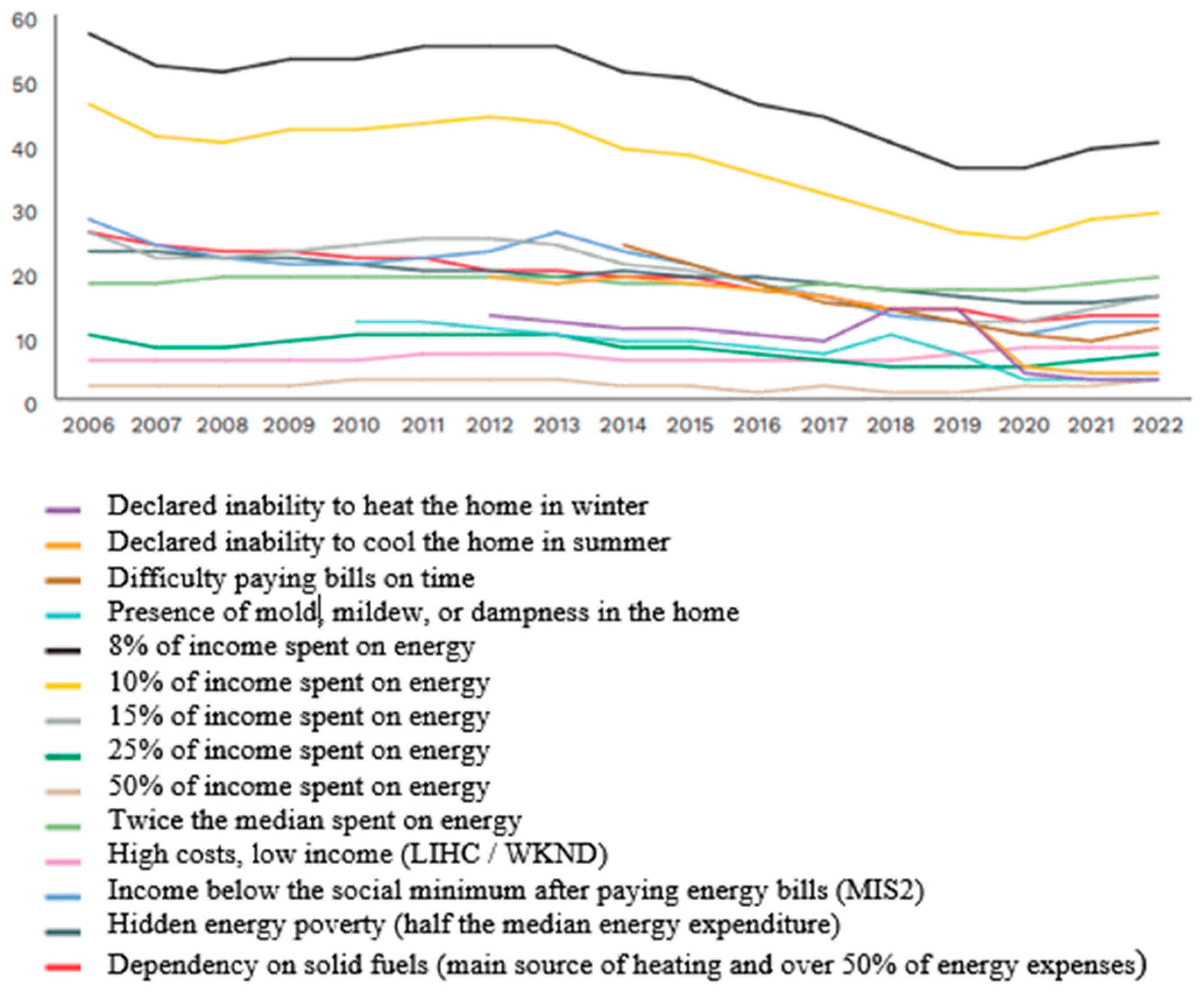

- Selecting Indicators to Measure Energy Poverty. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/Selecting%20Indicators%20to%20Measure%20Energy%20Poverty.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Policy Report, Energy Poverty and Vulnerable Consumers in the Energy Sector across the EU: Analysis of Policies and Measures. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/INSIGHT_E_Energy%20Poverty%20-%20Main%20Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Addressing Energy Poverty in the European Union: European State of Play and Action. Available online: https://www.energypoverty.eu/sites/default/files/downloads/publications/18-08/paneureport2018_final_v3.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- The Health Impacts of Cold Homes and Fuel Poverty. Available online: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/the-health-impacts-of-cold-homes-and-fuel-poverty/the-health-impacts-of-cold-homes-and-fuel-poverty.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Directive 2009/73/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 Concerning Common Rules for the Internal Market in Natural Gas and Repealing Directive 2003/55/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32009L0073 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Clean Energy for all Europeans. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/topics/energy-strategy/clean-energy-all-europeans_en (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Kiewra, D.; Szpor, A.; Witajewski-Baltvilks, J. Sprawiedliwa Transformacja Węglowa w Regionie Śląskim. Implikacje dla Rynku Pracy; IBS Research Reports 2019; Instytut Badań Strukturalnych: Warszawa, Polska, 2019; pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Structural Change in Coal Phase-Out Regions. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/Policy%20Brief%20structural%20change%20in%20coal%20phase-out%20regions.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Uchwała w Sprawie “Polityki Energetycznej Polski do 2040 r”. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/polski-atom/uchwala-w-sprawie-polityki-energetycznej-polski-do-2040-r (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Polish Ministry of Climate and Environment. Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040 r. PEP2040. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/ia/polityka-energetyczna-polski-do-2040-r-pep2040 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Polish National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management. Program Czyste Powietrze. Available online: https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Polish National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management. Program Ciepłe Mieszkanie. Available online: https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/inne-programy/cieple-mieszkanie (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Federacja Konsumentów. Assist—Sieć Doradców Wrażliwych Odbiorców Energii. Available online: https://www.federacja-konsumentow.org.pl/225,assist--siec-doradcow-wrazliwych-odbiorcow-energii.html (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder). CSOP—Financing; Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder): Frankfurt (Oder), Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Poland. We Protected Poles from the Energy Crisis. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/primeminister/we-protected-poles-from-the-energy-crisis (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego. Fundusz Termomodernizacji i Remontów. Available online: https://www.bgk.pl/programy-i-fundusze/fundusze/fundusz-termomodernizacji-i-remontow-ftir/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Prawo.pl. Dz.U. UE L 2024, 618. Available online: https://www.prawo.pl/akty/dz-u-ue-l-2024-618,72281934.html (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- D’Silva, M.C. Public Policy Responses to the Energy Crisis. In Energy, Sustainability and Society; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.F.; Ferreira, J.A.; Almeida, A.J. Renewable Energy Policies: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Energy Policy 2024, 166, 112878. [Google Scholar]

- Ørsted. Sveriges Framtida Energimix. Available online: https://orsted.se/sveriges-framtida-energimix (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- BIM Energy. Home. Available online: https://bimenergy.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Arshad, S.S.; Alwazir, A.S.; Khan MZ, A.; Nasir, M.A. An Overview of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Policy in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ULMA Construction. Conversion Energy Efficiency Grant. Available online: https://ulma.se/en/blog/post/conversion-energy-efficiency-grant (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Nordic Council of Ministers. Housing Allowance in Sweden. Available online: https://www.norden.org/en/info-norden/housing-allowance-sweden (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Instytut Badań Strukturalnych. Cztery Oblicza Ubóstwa Energetycznego. In Polskie Gospodarstwa Domowe w Czasie Kryzysu 2021–2023; Instytut Badań Strukturalnych: Warszawa, Polska, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- AGH Akademia Górniczo-Hutnicza. Energetyka Rozproszona w Polsce: Analiza i Wnioski; AGH Akademia Górniczo-Hutnicza: Kraków, Polska; Available online: https://www.energetyka-rozproszona.pl/media/magazine_attachments/9-14_AGH_zeszyt_3.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Polish Institute for Energy Poverty. Ubóstwo Energetyczne w Polsce: Przyczyny, Skutki, Rozwiązania; Polish Institute for Energy Poverty: Warszawa, Polska, 2021; Available online: https://www.pine.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/broszura-ubostwo-energetyczne.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Lopes, J.A.P.; Soares, F.J.; Almeida, P.M.R. Integration of Electric Vehicles in the Electric Power System. Proc. IEEE 2011, 99, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, M.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. A Self-Tuning LCC/LCC System Based on Switch-Controlled Capacitors for Constant-Power Wireless Electric Vehicle Charging. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhil, M.M.S.; Zaidan, E.J.H.; Zaidan, A.H.; Rahman, M.B.M.A.; Ab Rahman, A.M. Renewable Energy Sources and Their Role in Energy Efficiency: A Review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahal, D.S.; Awad, A.A.; Khalil, M.T. A Review of Renewable Energy Technologies and Their Contribution to Energy Efficiency. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 48, 102315. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, K.L.; El-Shafey, R.H.; Abd El-Aziz, H.E. The Role of Renewable Energy in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 50, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tools to Support the Struggle Against Energy Poverty | Description |

|---|---|

| Energy Policy until 2040 | Poland’s national efforts, outlined in the Energy Policy until 2040 (PEP2040), focus on reducing energy poverty to 6% by 2030. The policy emphasizes the importance of establishing appropriate legal frameworks, including clarifying the definition of energy poverty, developing metrics to assess it, and identifying key areas for action. Poland’s energy policy until 2040 defines the framework for energy transition and is a response to the EU climate policy [6]. |

| Clean Air Clean Air Plus | The Clean Air program is one of Poland’s flagship initiatives aimed at improving air quality and addressing energy poverty by modernizing heating systems and enhancing the energy efficiency of single-family homes. The program provides financial support for replacing outdated, inefficient heating sources, such as coal-fired stoves, with more eco-friendly alternatives, and for implementing thermal upgrades to buildings. Its scope includes upgrading heating systems, improving insulation, and installing renewable energy technologies. The program is primarily targeted at owners and co-owners of single-family houses. Additionally, it offers special assistance to low-income households through the Clean Air Plus initiative, which provides even higher levels of financial aid. Beneficiaries can receive support in the form of grants or low-interest loans to fund these improvements [38]. |

| Warm Apartment | The Warm Apartment program is a Polish government initiative designed to enhance energy efficiency in multi-family apartment buildings. It provides financial support for upgrading old, inefficient heating systems to modern, eco-friendly alternatives, such as gas boilers or heat pumps, and for improving insulation to lower energy usage and costs. The program offers grants, with additional assistance for low-income households, to promote cleaner, more efficient heating and better living conditions, particularly in older apartments. It plays a key role in reducing energy poverty and air pollution while supporting Poland’s climate goals [39]. |

| ASSIST in Poland | ASSIST in Poland is part of a European initiative focused on combating energy poverty by offering direct support to vulnerable households. The program trains Vulnerable Consumers Energy Advisors (VCEA) to assist low-income families and seniors in managing energy use, cutting costs, and improving energy efficiency in their homes. The project provides personalized guidance, runs awareness campaigns on energy-saving strategies, and collaborates with local governments and NGOs [40]. |

| The Consumer Stock Ownership Plan (CSOP) | The Consumer Stock Ownership Plan (CSOP) empowers consumers, particularly those without savings or access to capital credit, to acquire ownership stakes in the renewable energy installations they use, transforming them into ‘prosumers’. This consumer-focused investment model in public utilities provides both financial participation and a voice in management decisions. By shielding consumer shareholders from personal liability, CSOP enables co-investment opportunities for municipalities, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and other local stakeholders, fostering broader community engagement in sustainable energy projects [41]. |

| The Energy Shield Allowance (Energy Supplement) | The Energy Shield Allowance (Energy Supplement) is a direct financial support program designed to help households facing difficulties in paying their energy bills. It targets low-income individuals, with the amount of the allowance determined by household size and income. This initiative is part of a wider social policy aimed at alleviating the effects of rising energy costs [42]. |

| The Thermomodernization and Renovation Fund | The Thermomodernization and Renovation Fund is a support program for housing cooperatives and associations aimed at enhancing the energy efficiency of multi-family buildings. By reducing heating costs, thermomodernization helps to alleviate energy poverty. The program covers a range of energy-saving measures, including window replacement, upgrades to heating systems, and other improvements designed to increase energy efficiency [43]. |

| Tools to Support the Struggle Against Energy Poverty | Description |

|---|---|

| Energy Efficiency Law (Energilagen) | Key regulations on energy consumption and energy management in the building sector are defined in this law. It imposes an obligation on building owners and property managers to strive to reduce energy consumption and CO2 emissions, which has a direct impact on reducing energy poverty [44]. |

| Climate strategy | Sweden is aiming for climate neutrality by 2045 as part of its climate policy, and the building sector plays a key role in this transition. This includes requirements for energy retrofits of existing buildings [45]. |

| Boverket—Sweden’s National Council for Building, Planning and Housing | This council administers standards that set minimum requirements for energy efficiency. These must be met by new buildings, as well as by retrofitting existing buildings. The standards address high thermal insulation and mandate the use of energy-efficient technologies [46]. |

| Mandatory energy certificates (Energideklaration) | Sweden requires an energy certificate for every residential building. These certificates assess the building’s energy efficiency based on energy consumption and recommend improvement measures. Owners of buildings with low efficiency are required to make improvements [47]. |

| Grants for thermomodernization | Building owners can apply for subsidies for measures to improve insulation, replace windows, and upgrade heating systems. This effectively reduces energy demand [48]. |

| Support for renewable energy in buildings | The government offers subsidies and tax breaks for owners who choose to install renewable energy sources, such as photovoltaic panels and heat pumps. Renewable energy sources reduce energy costs, which helps in the fight against energy poverty. Wind and hydroelectric power plants: The high share of renewables in Sweden’s energy mix contributes to stable and relatively low energy prices compared to fossil fuel-dependent countries [49]. |

| Warm rent rules | Public housing often has a “warm rent” policy, which means that all energy charges are included in one rent. This gives financial stability to tenants, who do not have to worry about sharp increases in energy prices [50]. |

| Subsidy for heating costs | People with low incomes can apply for energy allowances to help cover rising heating costs, especially during the winter months [51]. |

| Housing benefits | Social support for people who have difficulty paying their rent often includes covering part of the cost of energy [52]. |

| Impact in Poland | Impact in Sweden |

|---|---|

| Energy Prices—As Poland shifts towards decarbonization, its coal-dependent energy system is likely to face rising costs, which could result in higher energy prices. This would disproportionately affect households already at risk of energy poverty. Moreover, the growing demand for electric vehicles could further strain the electricity grid, potentially driving energy costs even higher and worsening the burden on vulnerable consumers. | Affordable Electricity—Sweden’s energy grid, primarily powered by renewable sources like hydropower and wind, offers long-term cost efficiency. As a result, the widespread adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) is unlikely to cause significant increases in energy prices. This allows lower-income households to potentially benefit from reduced transportation costs without facing higher energy bills, making the EV transition more accessible and economically advantageous for a broader population. |

| Dependence on Fossil Fuels—Since Poland’s energy grid is still largely reliant on coal, the environmental and economic advantages of transitioning to electric vehicles (EVs) could be undermined unless substantial investments are made in renewable energy sources. Without such investments, the shift to EVs may result in higher electricity bills for households, perpetuating the cycle of energy poverty rather than alleviating it. For many families, the cost burden could grow, especially if clean energy alternatives are not adopted at scale. | Accessibility—Sweden’s energy grid, predominantly powered by renewable sources like hydropower and wind, ensures long-term cost stability. Consequently, the widespread adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) is unlikely to significantly increase energy prices. This stability allows lower-income households to benefit from reduced transportation costs without a corresponding rise in energy bills, making the EV transition more affordable and accessible across all income levels, while also enhancing overall economic efficiency. |

| Rural and Poorer Communities—The initial deployment of EV charging infrastructure is likely to be concentrated in urban areas, potentially leaving rural and economically disadvantaged regions underserved. This disparity in access could exacerbate energy inequality, as rural households may struggle to benefit from the transition to electric vehicles due to limited availability and higher costs of charging stations in their areas. | Policy Support—Sweden has implemented forward-thinking policies to promote the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) and expand renewable energy usage, increasing the likelihood that this transition will ease, rather than exacerbate, energy poverty. Financial incentives and subsidies for EV purchases make EV ownership more accessible to low-income households, while the country’s robust renewable energy grid ensures these benefits reach a broader segment of the population. This comprehensive approach helps ensure that the shift to EVs is both environmentally sustainable and socially inclusive. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janikowska, O.; Generowicz-Caba, N.; Kulczycka, J. Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden. Energies 2024, 17, 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215481

Janikowska O, Generowicz-Caba N, Kulczycka J. Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden. Energies. 2024; 17(21):5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215481

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanikowska, Olga, Natalia Generowicz-Caba, and Joanna Kulczycka. 2024. "Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden" Energies 17, no. 21: 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215481

APA StyleJanikowska, O., Generowicz-Caba, N., & Kulczycka, J. (2024). Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden. Energies, 17(21), 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17215481