The Influence of Hydrogen Concentration on the Hazards Associated with the Use of Coke Oven Gas

Abstract

1. Introduction

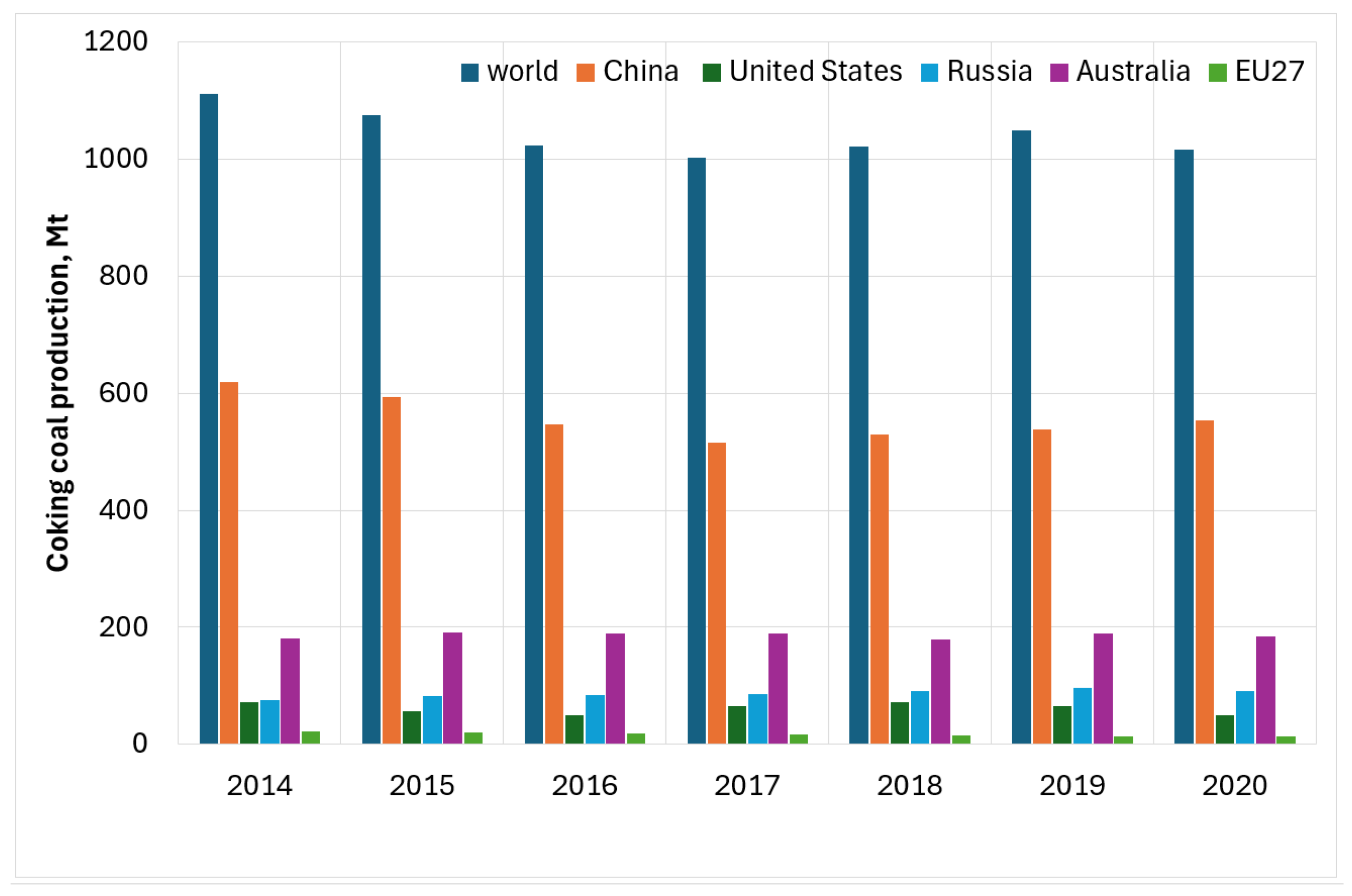

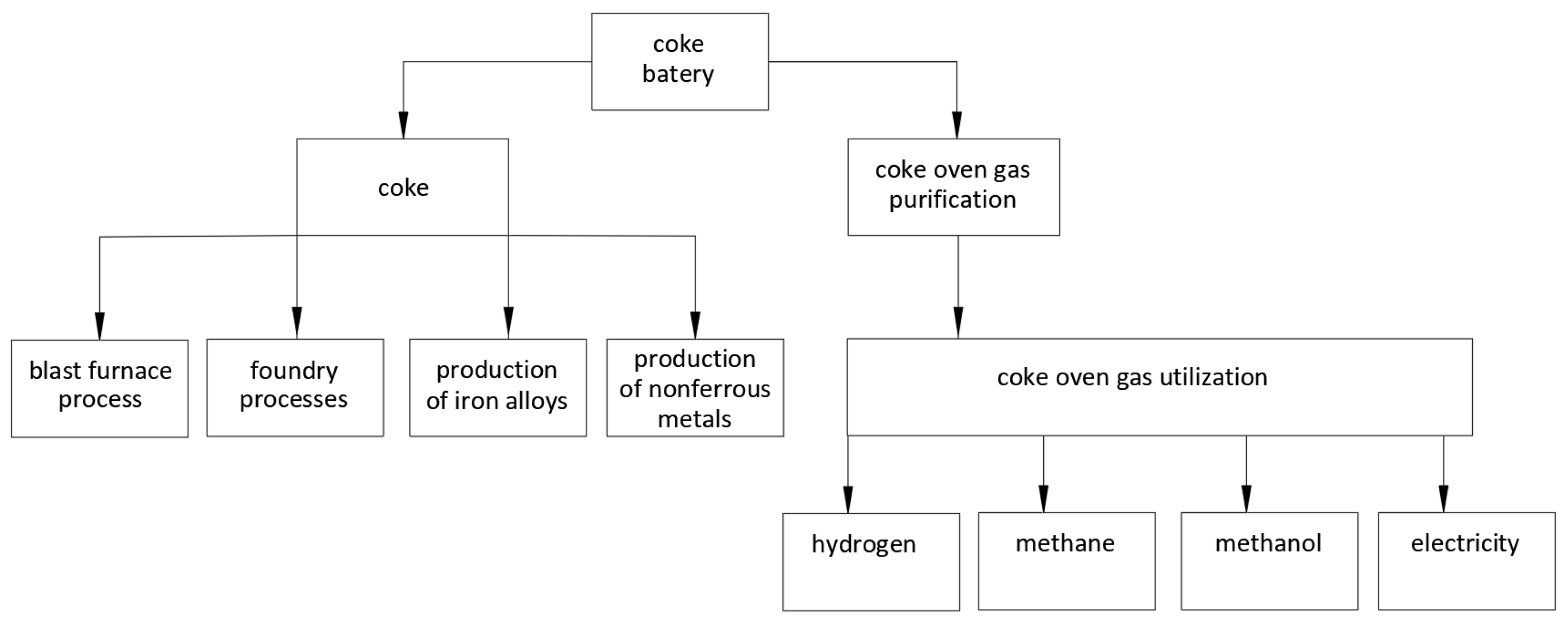

2. Coking Industry and Coke Oven Gas (COG)

3. Characteristics of Coke Oven Gas

- The combustion of coke oven gas. This is one of the basic methods of COG utilization. Raw COG can be combusted on-site in blast furnaces and coke oven batteries in the coking process. It can also be combusted in small combustion units, such as process heaters and boilers. A surplus of gas can be used to generate power and heat.

- The use of coke oven gas as a feedstock for hydrogen separation. Hydrogen is considered as a future clean energy source. Coke oven gas containing 50–60% hydrogen is a high-potential source of H2. The processes used to obtain hydrogen from COG are the process of pressure swing adsorption (PSA), membrane separation and cryogenic distillation. The PSA process and the membrane separation process are considered to be highly energy-intensive. They are commercially available. The membrane separation process, in turn, is less industrially developed.

- The use of coke oven gas to produce synthesis gas. Currently, synthesis gas is produced using steam reforming of natural gas and oil. Using coke-oven gas as an alternative to syngas production makes it possible to produce syngas in a less energy-intensive and cleaner way. Synthesis gas, in turn, is a valuable source of hydrogen and a raw material for the production of chemicals and fuels.

- The use of coke oven gas in methanol synthesis. Methanol is used in many industries, e.g., for the production of chemicals. The high hydrogen content in coke oven gas means that COG is considered a good element for sustainable methanol production. This is because COG is used to produce syngas, which is in turn useful in methanol synthesis. However, the process is not free of disadvantages. The problems associated with the use of COG to produce syngas are related to the reduction of hydrogen content in the finished syngas, which in turn results in a low H2:CO ratio, which is unsuitable for the synthesis of methanol.

- The methanation of coke oven gas. The catalytic co-methanation of CO and CO2 (COx) in COG to CH4 enrichment is considered a simple and efficient way to produce a gas with a high heating value and a wide range of industrial and commercial uses. Methanation of COG can occur without the addition of other reagents, while CH4 can be separated as a valuable fuel. An important factor in the process is the selection of a catalyst, especially for low-temperature methanation. This is to provide long-term thermal stability and minimize operating costs for large-scale applications.

- Others.

4. Hazards Related to the Use of Coke Oven Gas

- Hydrogen (H2)—is considered to be the future energy carrier. It is a raw material in the production of chemicals, refining processes, etc. [24]. The potential of hydrogen is also used in the power generation and transport sectors. Under normal conditions, hydrogen is a gas with a very low density. The product of its combustion is water and a significant amount of released energy. A characteristic property of hydrogen that has a major impact on the safety of its use is its wide flammability range of 4 to 75%. Another property that affects the potential hazard of accidental ignition of hydrogen is its low ignition energy, i.e., the minimum amount of external energy that, if supplied to hydrogen, can ignite it. This value is only 0.02 mJ, while for other fuels these energies are more than ten times higher. Such a low value of hydrogen ignition energy means that any uncontrolled leakage of hydrogen can result in a fire, and an igniting spark may be generated as a result of the friction of the flowing hydrogen stream itself or may come from electrostatic interactions [37].

- Methane (CH4)—is a non-toxic, colourless and odourless gas. Methane is flammable and burns with a blue and yellow flame. The minimum ignition energy of methane is 0.28 mJ, and its flammability limits range from 5 to 15%. In the right proportions, a mixture of air and methane has flammable and explosive properties [38].

- Carbon monoxide (CO)—is a flammable gas. It burns in the air with a small, brightening blue flame. Carbon monoxide is also toxic. It quickly combines with haemoglobin, causing a decrease in cellular respiration, which is particularly harmful to the central nervous system. Initial symptoms of poisoning include headache, nausea, vomiting and blurred vision. Then chest pain, shortness of breath, weakness and fainting. In case of severe toxicity, it causes cardiac arrhythmia, myocardial ischemia, cardiac arrest, pulmonary oedema and coma [39,40].

- Carbon dioxide (CO2)—is a colourless and odourless gas lighter than air. Because it is odourless, it is difficult to detect. The effect of carbon dioxide on humans and the environment depends on the concentration and time of exposure. Lower concentrations of CO2 cause higher breathing rates. Headaches and ear buzzing may also occur. At higher concentrations, blood pressure increases, and hallucinations, loss of consciousness and convulsions may occur. Spending a long time in high concentrations of carbon dioxide can cause death. Exposure to concentrations exceeding 30% causes immediate human death [38].

- Ammonia (NH3)—is considered a toxic and flammable substance. Ammonia is difficult to ignite in air, but it creates a flammable/explosive mixture in closed spaces. Ammonia is toxic, irritating and caustic. In the form of gas and vapour, it causes eye pain, conjunctival redness, cough, sore throat, nausea, vomiting and shortness of breath. Laryngeal oedema with a feeling of shortness of breath, bronchospasm, respiratory arrest and pulmonary oedema may also occur. Immediately after ammonia poisoning, acute bronchitis, pneumonia and fibrosis of the lung tissue with severe respiratory failure may occur. In contact with the skin, ammonia, its mist and solutions cause chemical burns with deep ulcerations. Liquid ammonia causes frostbite of the skin. The negative effects of ammonia on the human body depend on the concentration of ammonia vapour and the exposure time [38].

- Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)—is a colourless and extremely flammable gas. It has a characteristic rotten egg smell and is detectable even at very low concentrations. It is absorbed into the body through the lungs and to a small extent through the skin. Hydrogen sulfide is highly toxic, irritating and chemically asphyxiating. Lower concentrations of hydrogen sulfide cause irritation and inflammation of the eyes and the respiratory tract. Higher concentrations cause cough, headache, eye pain and swelling of the eyelids. In very high concentrations, hydrogen sulfide causes severe irritation of the respiratory system. Respiratory and heart problems, loss of unconsciousness and death can occur [38].

- Others—depending on the final composition of the raw and purified coke oven gas.

5. Methodology

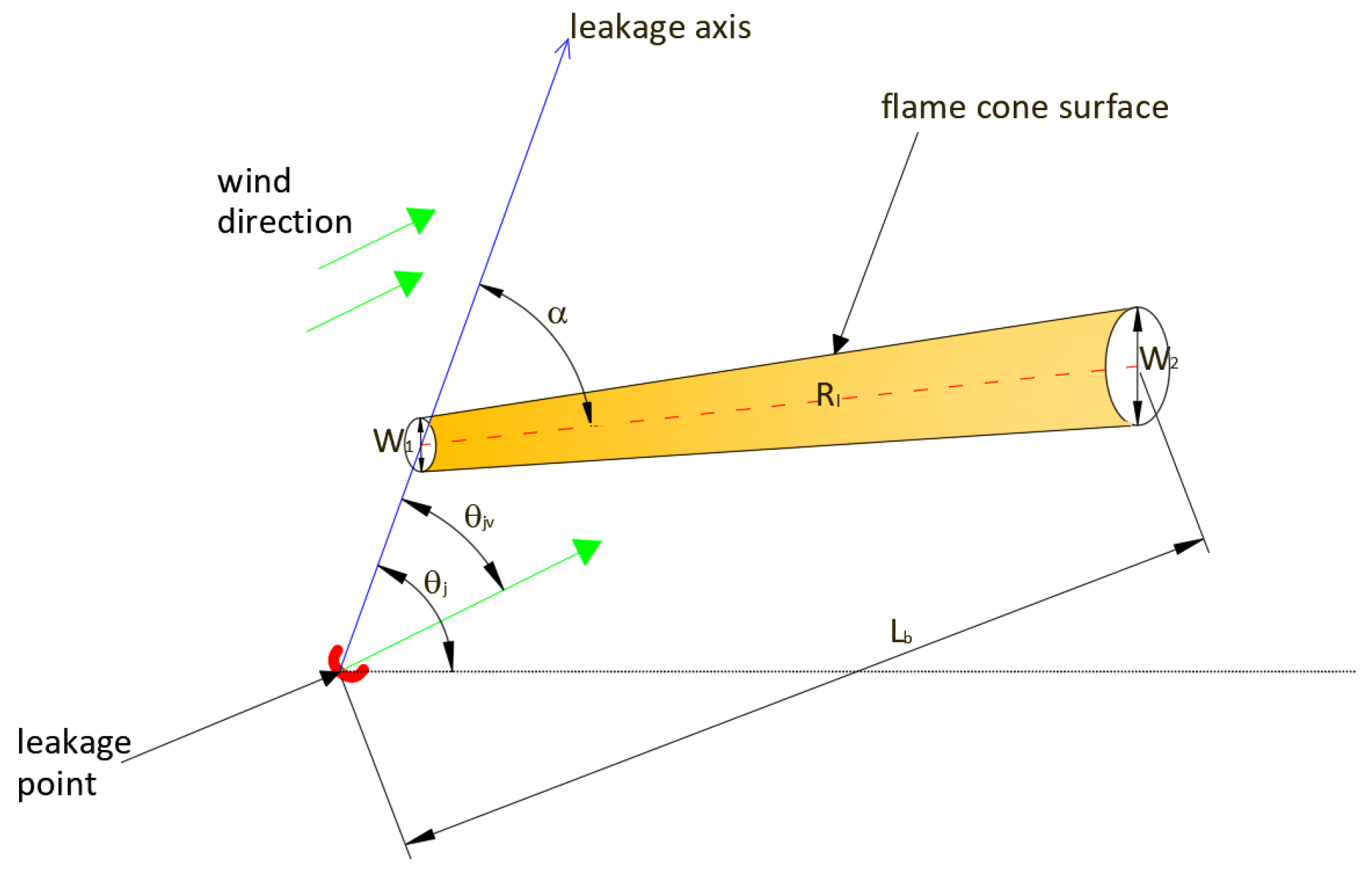

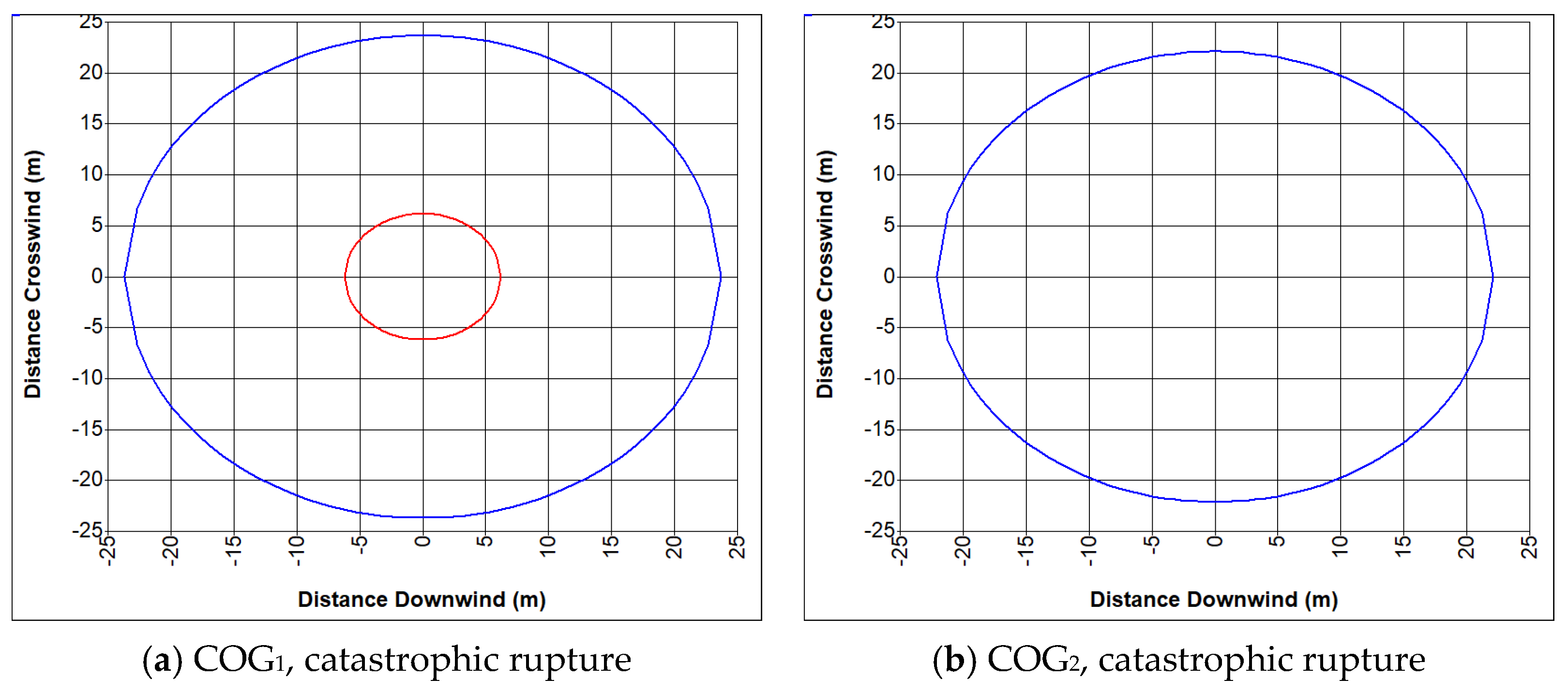

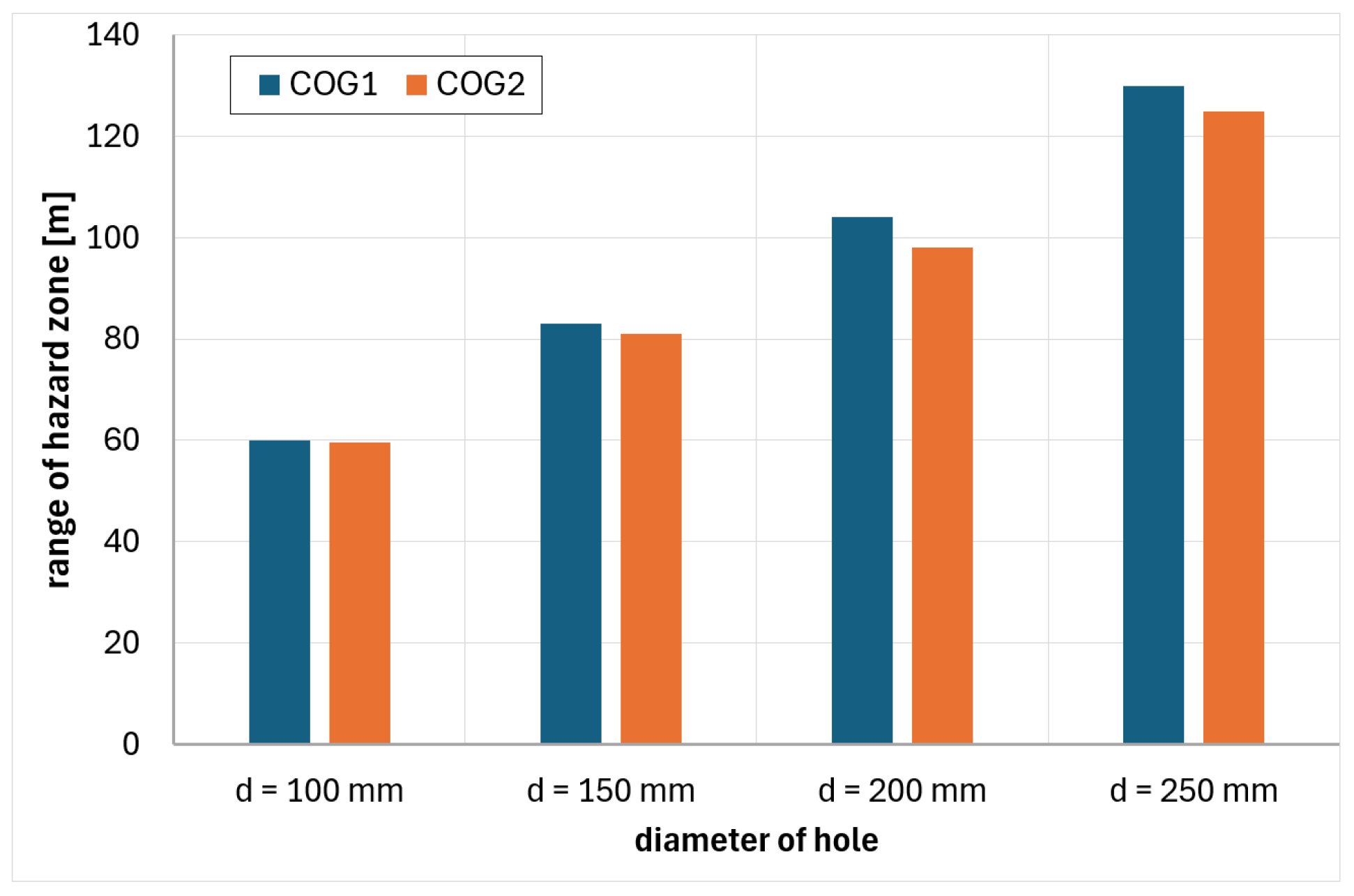

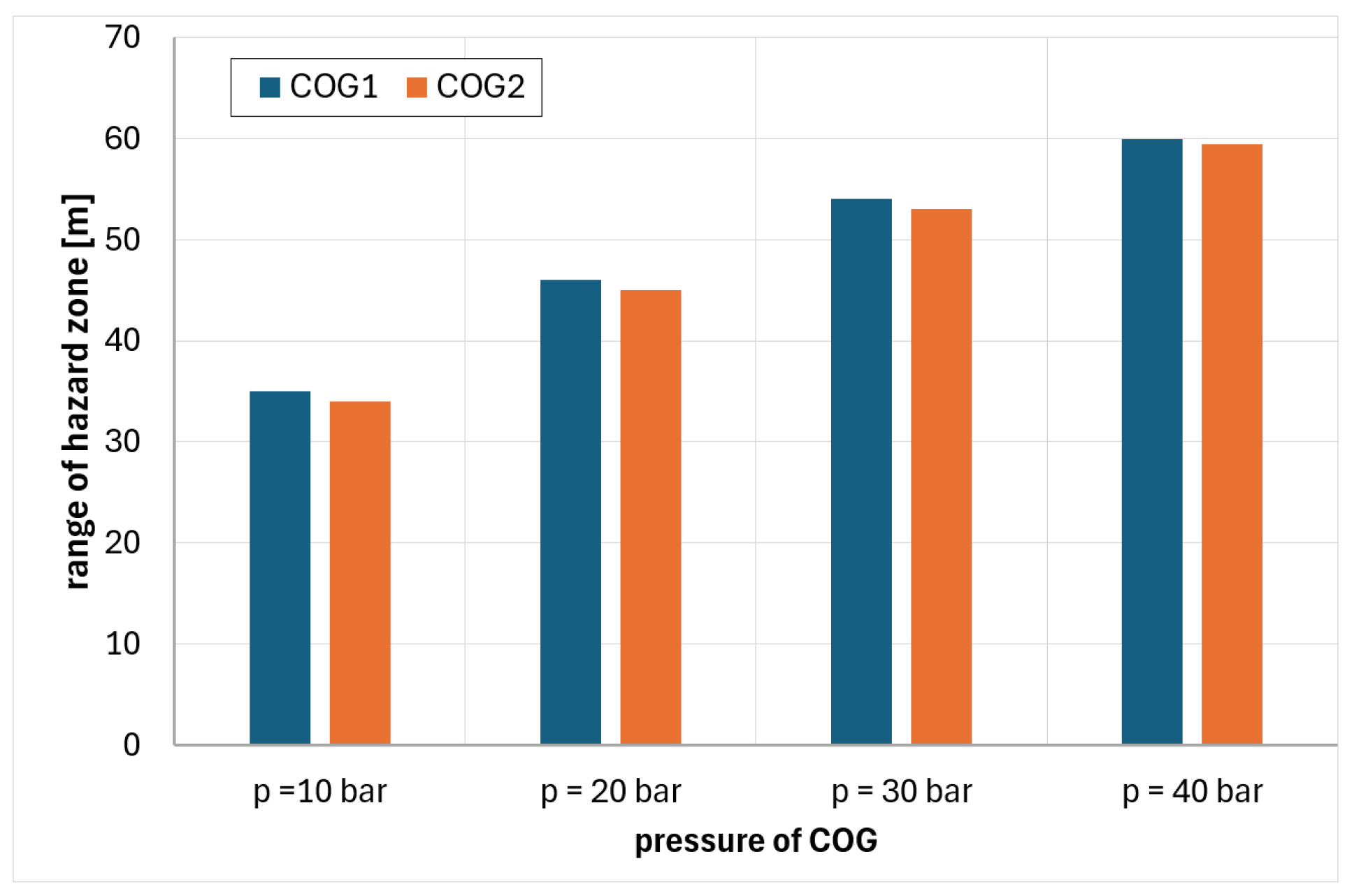

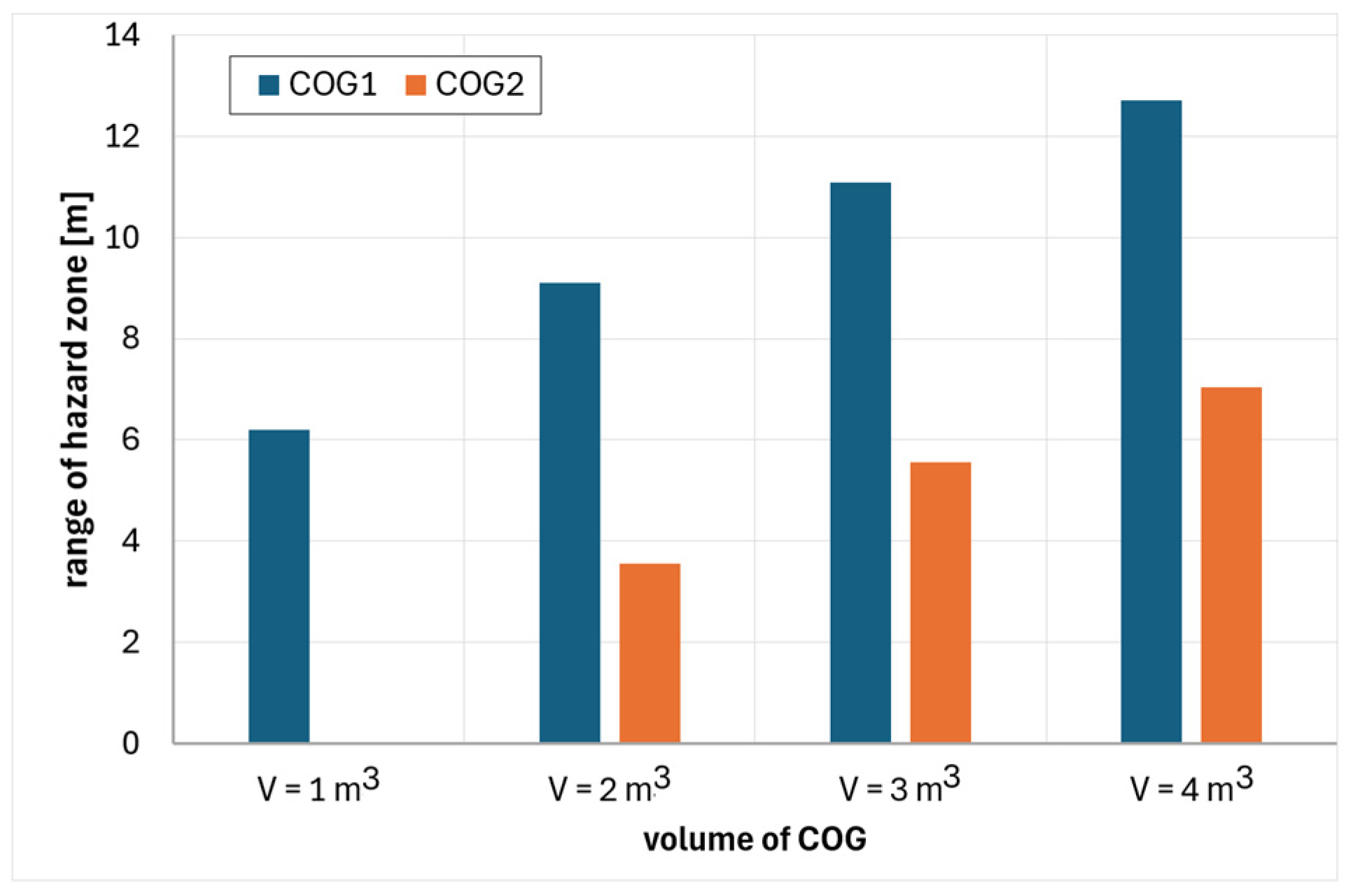

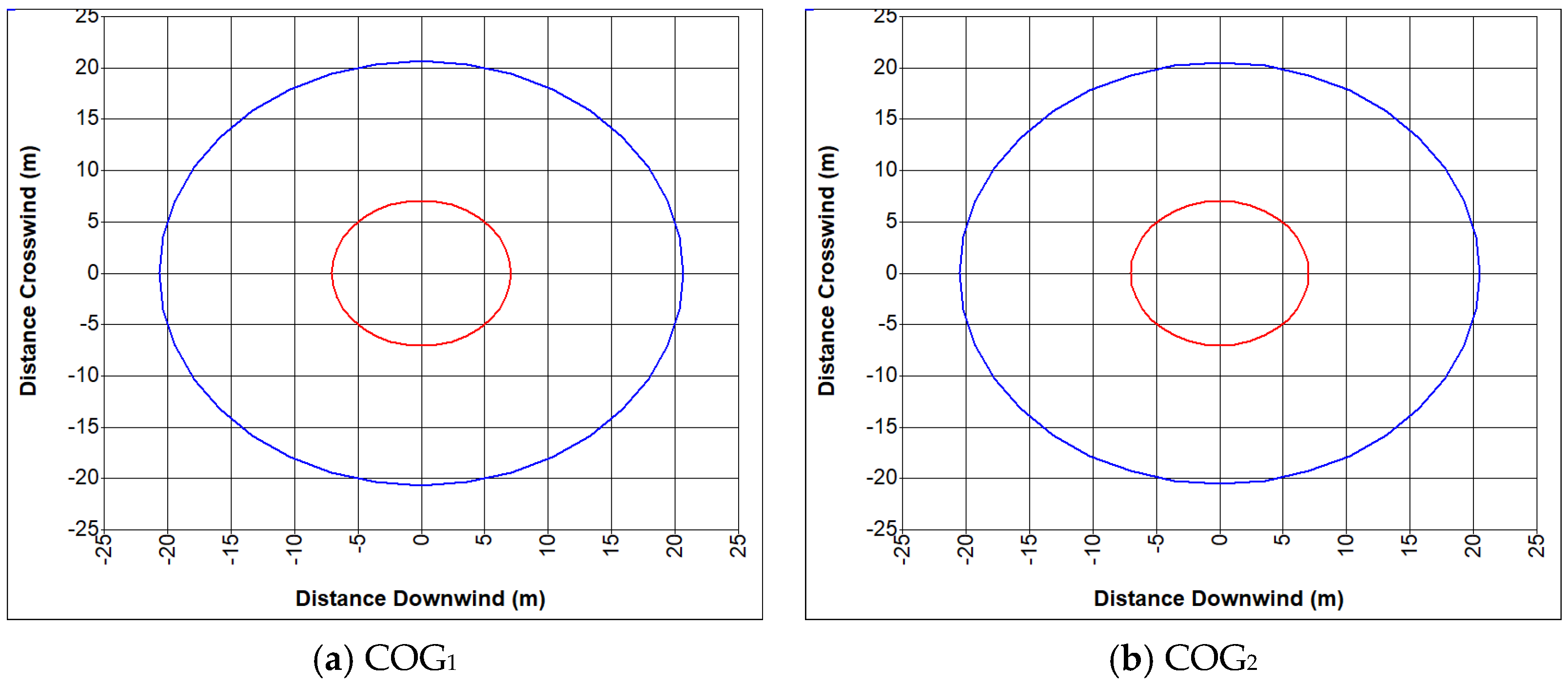

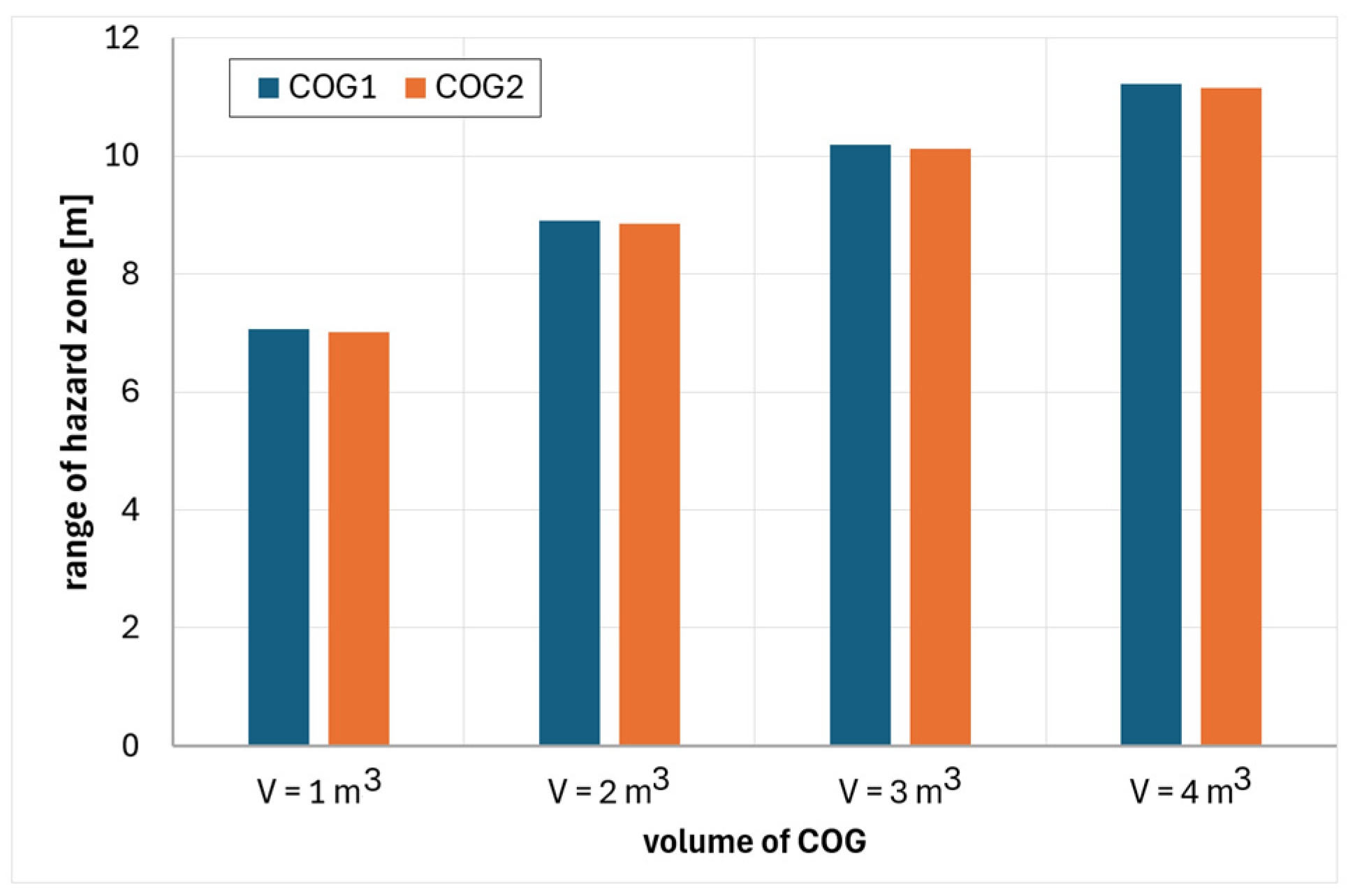

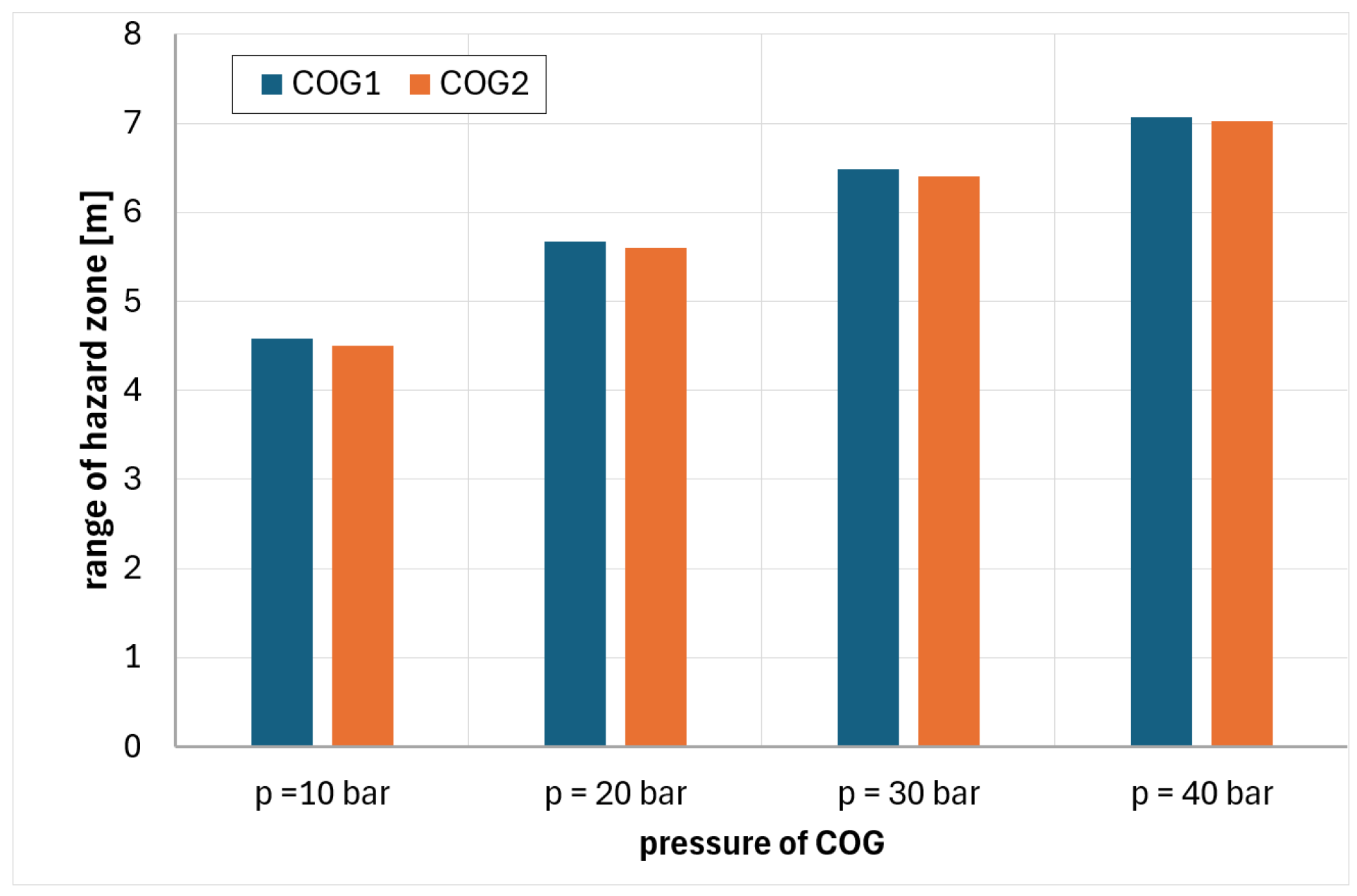

6. Analysis of Hazards Related to the Fire and Explosion of Coke Oven Gas

- COG1—60% H2, 29% CH4, 6% CO, 2% CO2, 3% N2

- COG2—55% H2, 29% CH4, 8% CO, 2% CO2, 6% N2

- (a)

- Fire of coke oven gas

- (b)

- Explosion of coke oven gas

7. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA—International Energy Agency. Coking Coal Production, 1990–2020—Charts—Data & Statistics. Available online: https://www.iea.org/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Yıldız, I. Comprehensive Energy Systems, 1.1.2. Foss. Fuels 2018, 1, 521–567. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalev, E.T.; Malina, V.P.; Rudyka, V.I.; Soloviov, M.A. Global Coal, Coke, and Steel Markets and Innovations in Coke Production: A Report on the European Coke 2018 Summit. Coke Chem. 2018, 61, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Ji, C. Experimental and numerical study on laminar combustion characteristics of by-product hydrogen coke oven gas. Energy 2023, 278, 127766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, J.; Lin, Q.; Konnov, A.A. Experimental and kinetic modeling study of the laminar burning velocity of CH4/H2 mixtures under oxy-fuel conditions. Fuel 2024, 376, 132597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias Neto, G.W.; Leite, M.B.M.; Marcelino, T.O.A.C.; Carneiro, L.O.; Brito, K.D.; Brito, R.P. Optimizing the coke oven process by adjusting the temperature of the combustion chambers. Energy 2021, 217, 119419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamrat, S.; Poraj, J.; Bodys, J.; Smolka, J.; Adamczyk, W. Influence of external flue gas recirculation on gas combustion in a coke oven heating system. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 152, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, M.; Jin, S.; Wang, D. The Structural Design of and Experimental Research on a Coke Oven Gas Burner. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.; Zhou, Y. Numerical analysis of NOx formation mechanisms and emission characteristics with different types of reactants dilution during MILD combustion of methane and coke oven gas. Fuel 2022, 309, 122131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczyński, R.; Kim, R. On optimization of the coke oven twin-heating flue design providing a substantial reduction of NOx emissions Part I: General description, validation of the models and interpretation of the results. Fuel 2022, 323, 124194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, G.; Lupant, D.; Lybaert, P. Effect of increasing load on the MILD combustion of COG and its blend in a 30 kW furnace using low air preheating temperature. Energy Procedia 2017, 120, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Imedio, R.; Ortiz, A.; Ortiz, I. Comprehensive analysis of the combustion of low carbon fuels (hydrogen, methane and coke oven gas) in a spark ignition engine through CFD modeling. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 251, 114918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Sun, Z.; Li, H.; Tian, R. Simulation and 4E analysis of a novel coke oven gas-fed combined power, methanol, and oxygen production system: Application of solid oxide fuel cell and methanol synthesis unit. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 324, 124483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Cheng, A.; Wu, X.; Ruan, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, H.; He, G.; Xiao, W. Optimization of the hydrogen production process coupled with membrane separation and steam reforming from coke oven gas using the response surface methodology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 26238–26250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Zhang, T.; Bai, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, Z.; Hong, J. Environmental and economical assessment of high-value utilization routes for coke oven gas in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 353, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheng, W. Comparative life cycle energy consumption, carbon emissions and economic costs of hydrogen production from coke oven gas and coal gasification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 27979–27993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, A.S.; Liang, F.; Liu, M.; Jiang, H.; Toghan, A. Hydrogen production by water splitting coupled with the oxidation of coke oven gas in a catalytic oxygen transport membrane reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Du, T.; Webley, P.A.; Li, G.K. Vacuum pressure swing adsorption intensification by machine learning: Hydrogen production from coke oven gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 69, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, L.; Chang, C.; Di, Z. Steel slag-enhanced reforming process for blue hydrogen production from coke oven gas: Techno-economic evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radó-Fóty, N.; Egedy, A.; Nagy, L.; Hegedűs, I. Investigation and Optimisation of the Steady-State Model of a Coke Oven Gas Purification Process. Energies 2022, 15, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarczyk, E.; Sowa, F.; Kaiser, M.; Kern, W. Emissions at coke plants: European environmental regulations and measures for emission control. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2013, 66, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, R.; Li, C.; Zhang, S. Coke oven gas: Availability, properties, purification, and utilization in China. Fuel 2013, 113, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Chen, X.; Xu, X. Technology-environment-economy assessment of high-quality utilization routes for coke oven gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 666–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, G.; Ortiz-Imedio, R.; Ortiz, A.; Gorri, D.; Ortiz, I. Hydrogen Recovery from Coke Oven Gas. Comparative Analysis of Technical Alternatives. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 6106–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Hu, A.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yi, L.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M. The Research on Waste Heat Utilization Technology of Coke Oven Gas in Ascension Pipe. Coke Chem. 2023, 66, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, J.M.; Arenillas, A.; Luque, R.; Menéndez, J.A. An overview of novel technologies to valorise coke oven gas surplus. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 110, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajzadeh, E.; Zhuo, Y.; Shen, Y. Numerical investigation of the impact of injecting coke oven gas on raceway evolution in an ironmaking blast furnace. Fuel 2024, 358, 130345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ding, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, P. Catalytic partial oxidation of coke oven gas to syngas in an oxygen permeation membrane reactor combined with NiO/MgO catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 6239–6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Lei, F.; Jing, J.; Peng, H.; Lu, X.; Cheng, F. Technical alternatives for coke oven gas utilization in China: A comparative analysis of environment-economic-strategic perspectives. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2024, 21, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, B. Pyrolysis of coal with hydrogen-rich gases. 2. Desulfurization and denitrogenation in coal pyrolysis under coke-oven gas and synthesis gas. Fuel 1998, 77, 1643–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, B.; Li, G.; Ye, Q. Coke oven gas explosion suppression. Saf. Sci. 2013, 55, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Ren, T.; Du, T.; Liu, L.; Webley, P.A.; Li, G.K. Coke oven gases processing by vacuum swing adsorption: Carbon capture and methane recovery. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, K. Spatial distribution, environmental behavior, and health risk assessment of PAHs in soils at prototype coking plants in Shanxi, China: Stable carbon isotope and molecular composition analyses. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Wei, W.; Guo, A.; Zhang, C.; Sha, K.; Wang, R.; Wang, K.; Cheng, S. Health risk assessment of hazardous VOCs and its associations with exposure duration and protection measures for coking industry workers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Coke Oven Emissions. United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, V.; Vílchez, J.A.; Casal, J.; Planas, E. Fired equipment combustion chamber accidents: A historical survey. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2021, 71, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusin, A.; Stolecka, K. Hazards associated with hydrogen infrastructure. J. Power Technol. 2017, 97, 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Stolecka, K.; Rusin, A. Potential hazards posed by biogas plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolecka, K.; Rusin, A. Analysis of hazards related to syngas production and transport. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 2535–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraets, L. Carbon monoxide. Natl. Inst. Public Health Environ. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DNV Phast Software. 2012. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/software/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Witlox, H.W.M.; Fernandez, M.; Harper, M.; Oke, A.; Stene, J.; Xu, Y. Verification and validation of Phast consequence models for accidental releases of toxic or flammable chemicals to the atmosphere. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2018, 55, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, T. Development of source terms for gas dispersion and vapour cloud explosion modelling. Eng. Environ. Sci. 2006, 15, 108. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaldos, J.; Casal, J.; Montiel, H.; Sánchez-Carricondo, M.; Vílchez, J.A. Design of a computer tool for the evaluation of the consequences of accidental natural gas releases in distribution pipes. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 1998, 11, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, G.A. Developments in design methods for predicting thermal radiation from flares. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1987, 65, 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rusin, A.; Stolecka, K. Reducing the risk level for pipelines transporting carbon dioxide and hydrogen by means of optimal safety valves spacing. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2015, 33, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, A.; Rusin, A.; Majkut, M.; Stolecka, K. Analysis of compression and transport of the methane/hydrogen mixture in existing natural gas pipelines. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2018, 166, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaChance, J.; Tchouvelev, A.; Engebo, A. Development of uniform harm criteria for use in quantitative risk analysis of the hydrogen infrastructure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 2381–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | H2 | CH4 | CO | CO2 | N2 | CxHx | O2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | 59% | 29% | 7% | 2% | 3% | ||

| [27] | 60.5% | 26.3% | 7.2% | 1.5% | 4.7% | ||

| [28] | 57.8% | 31.6% | 7.6% | 3% | |||

| [29] | 54–59% | 24–28% | 5–8% | 1.5–3% | 2–4% | ||

| [30] | 60.9% | 20.7% | 6.9% | 1.8% | 7.8% | 2% | |

| [31] | 54.8% | 24% | 6.6% | 3.2% | 9.2% | 1.8% | 0.4% |

| [24] | 55–60% | 23–27% | 5–8% | 1–2% | 3–6% | 1.5–2.3% | |

| [32] | 55–60% | 22–28% | 6.5–10% | 1–3% | 3–5% | 0.3–0.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klejnowski, M.; Stolecka-Antczak, K. The Influence of Hydrogen Concentration on the Hazards Associated with the Use of Coke Oven Gas. Energies 2024, 17, 4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17194804

Klejnowski M, Stolecka-Antczak K. The Influence of Hydrogen Concentration on the Hazards Associated with the Use of Coke Oven Gas. Energies. 2024; 17(19):4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17194804

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlejnowski, Mateusz, and Katarzyna Stolecka-Antczak. 2024. "The Influence of Hydrogen Concentration on the Hazards Associated with the Use of Coke Oven Gas" Energies 17, no. 19: 4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17194804

APA StyleKlejnowski, M., & Stolecka-Antczak, K. (2024). The Influence of Hydrogen Concentration on the Hazards Associated with the Use of Coke Oven Gas. Energies, 17(19), 4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17194804