Breakdown Time Phenomena: Analyzing the Conductive Channel of Positive Impulse Voltage Discharges under Standard Temperature and Pressure Air Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

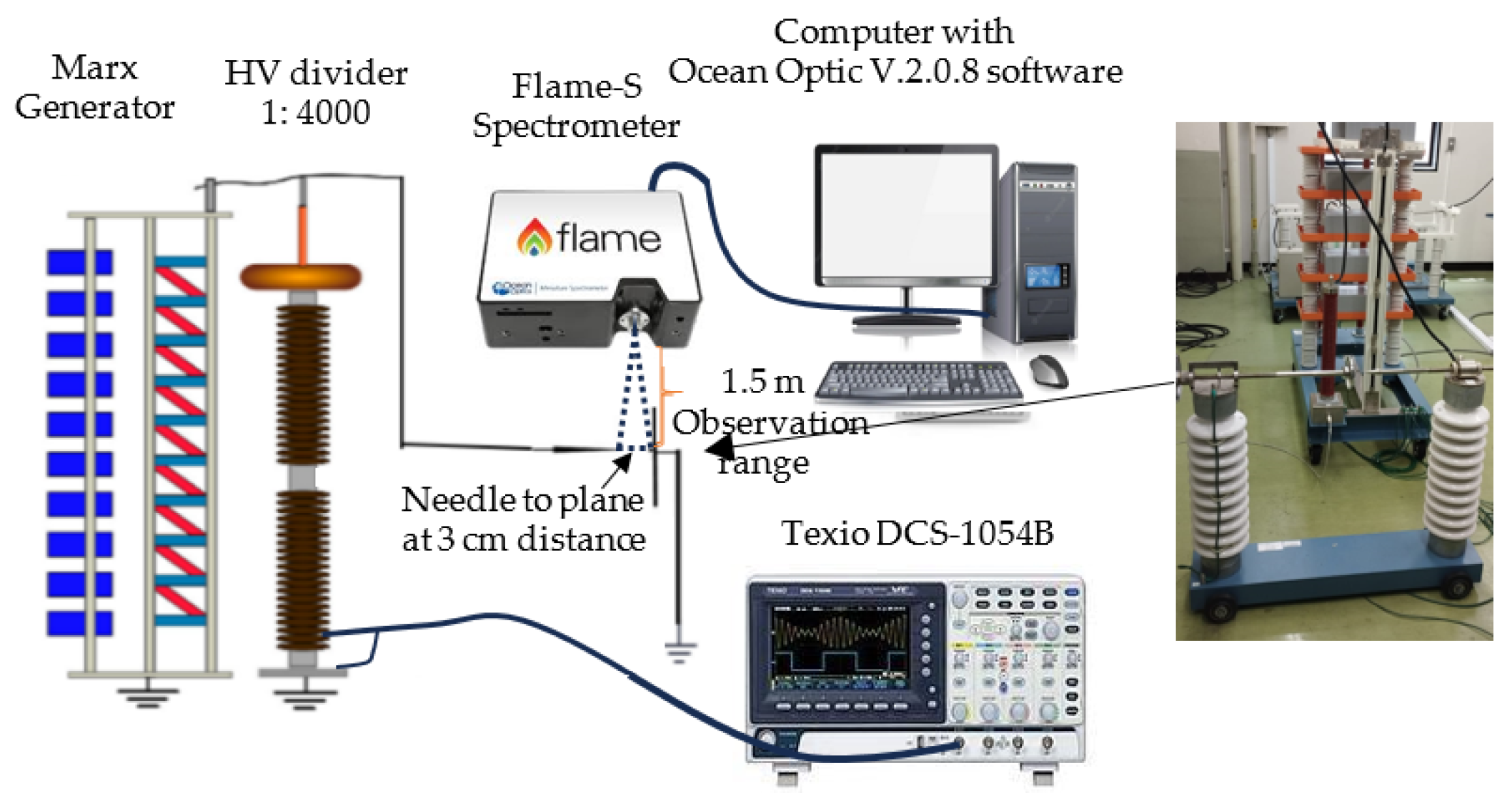

2. Experiments and Methods

3. Results

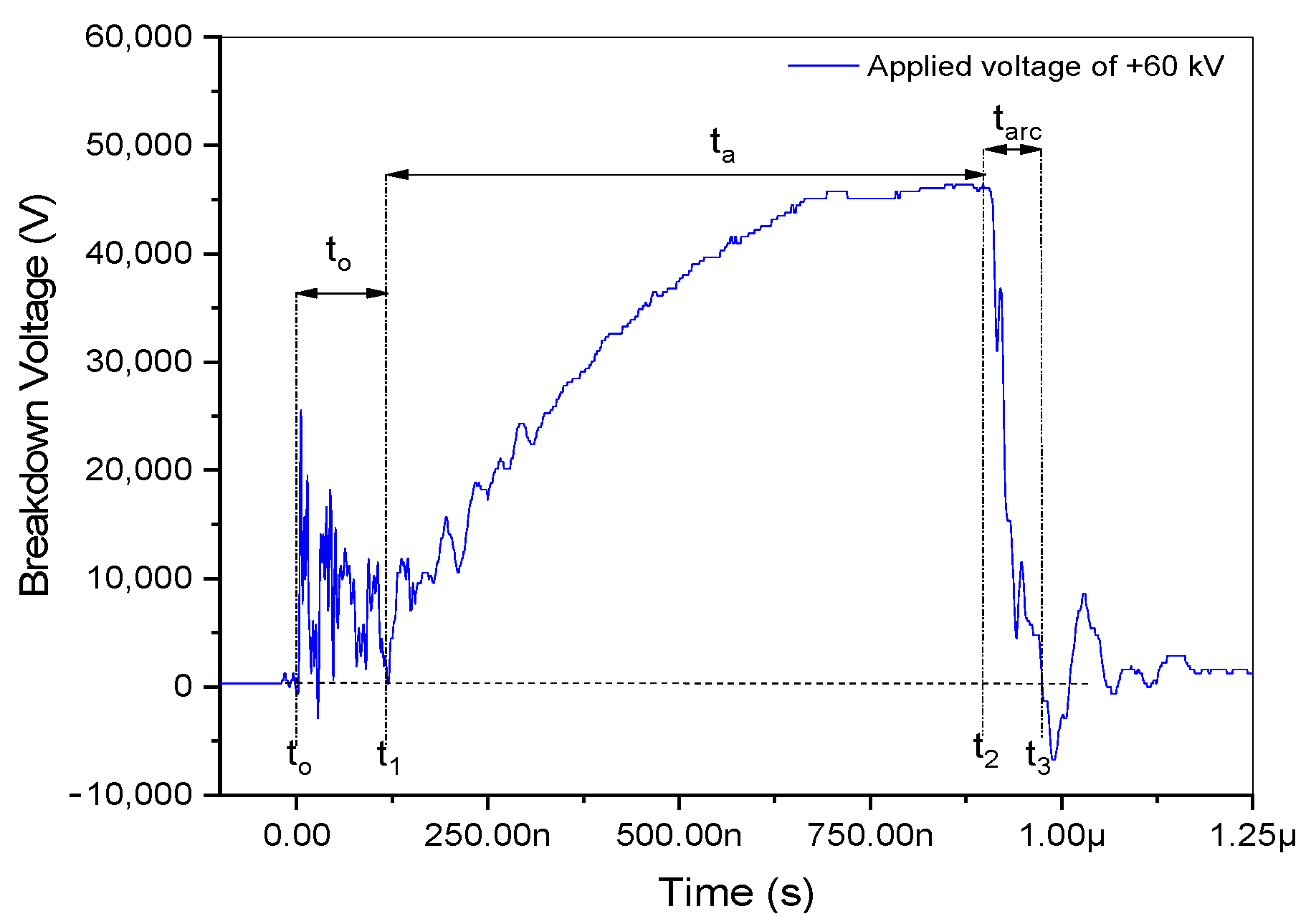

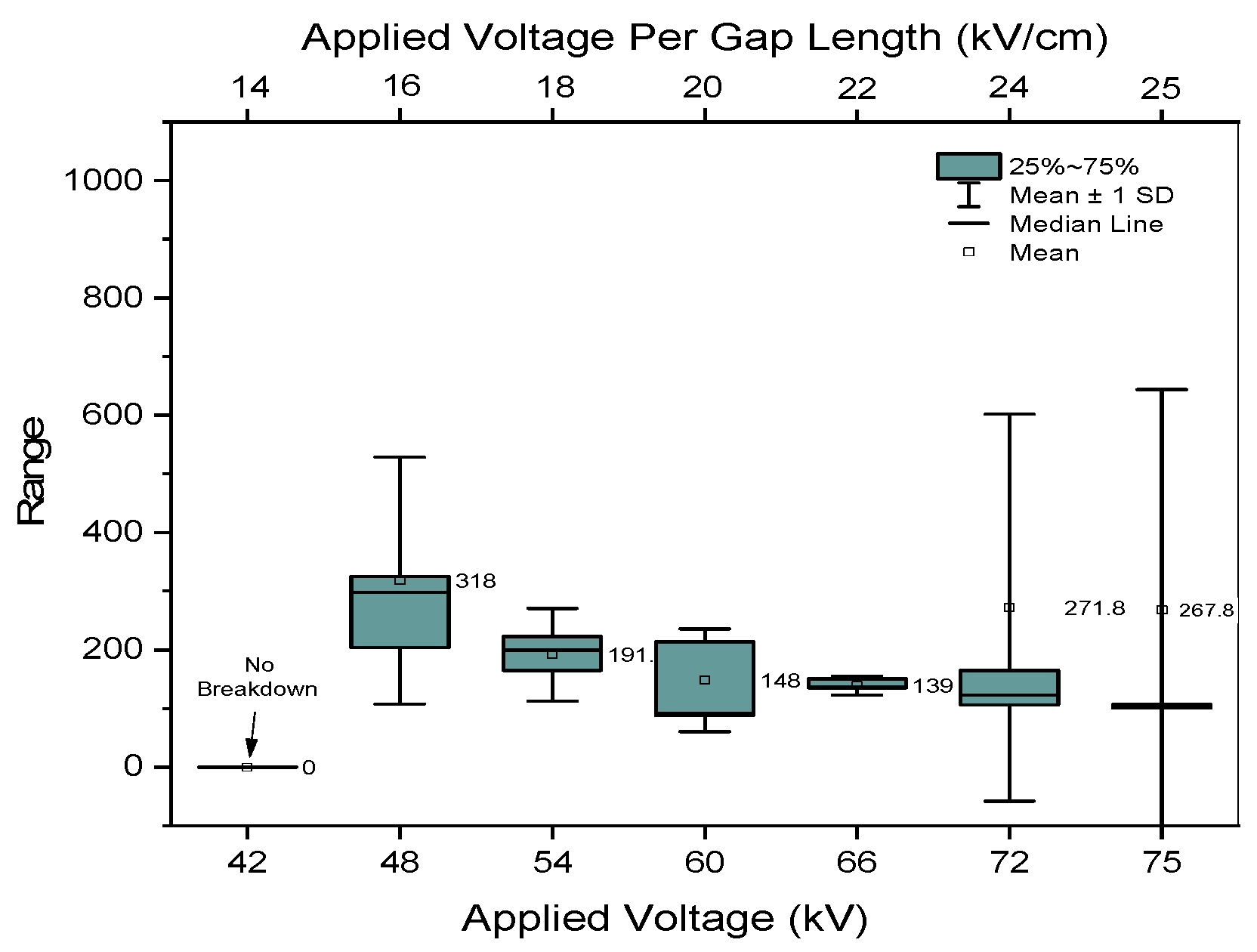

3.1. Times of Breakdown

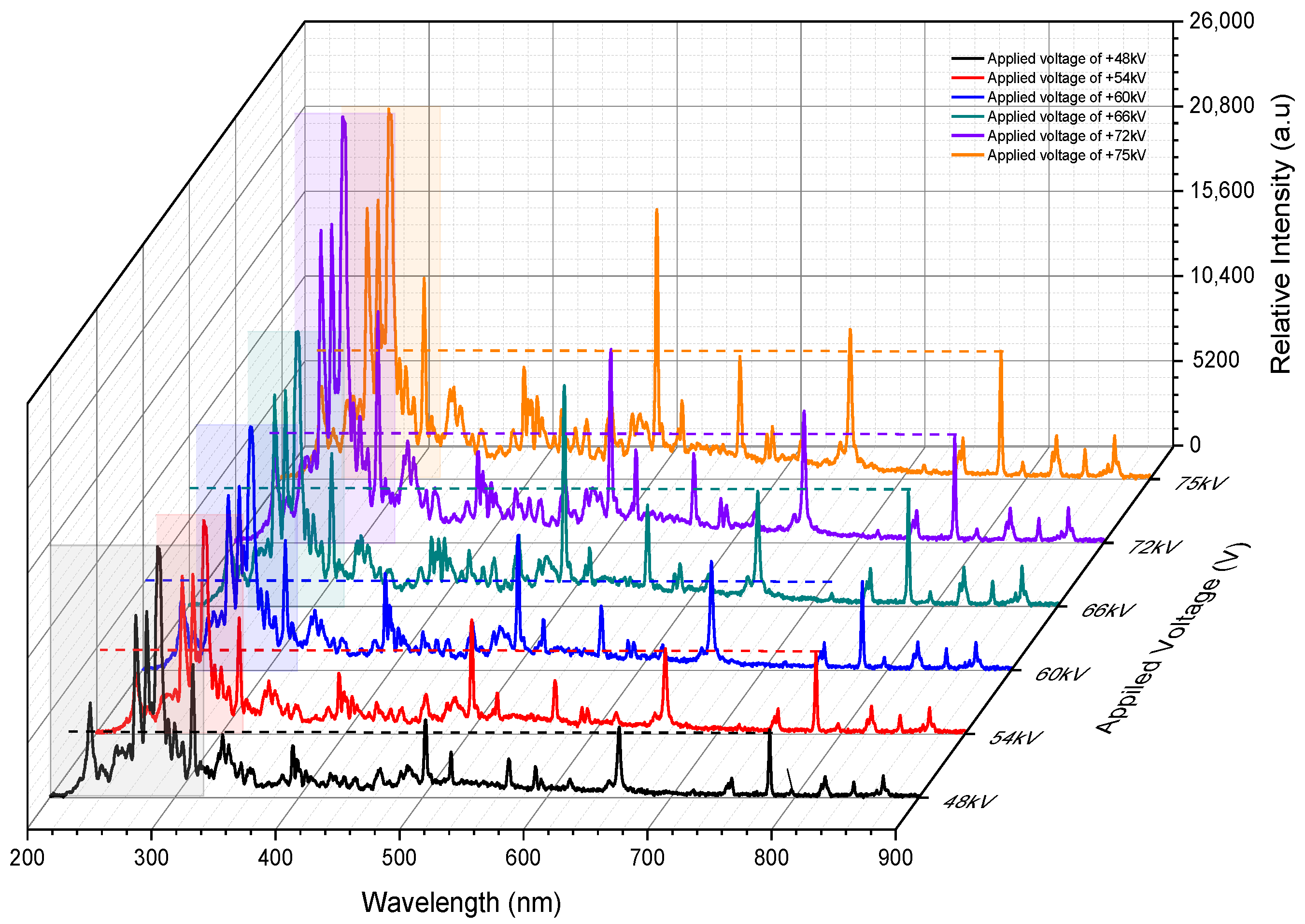

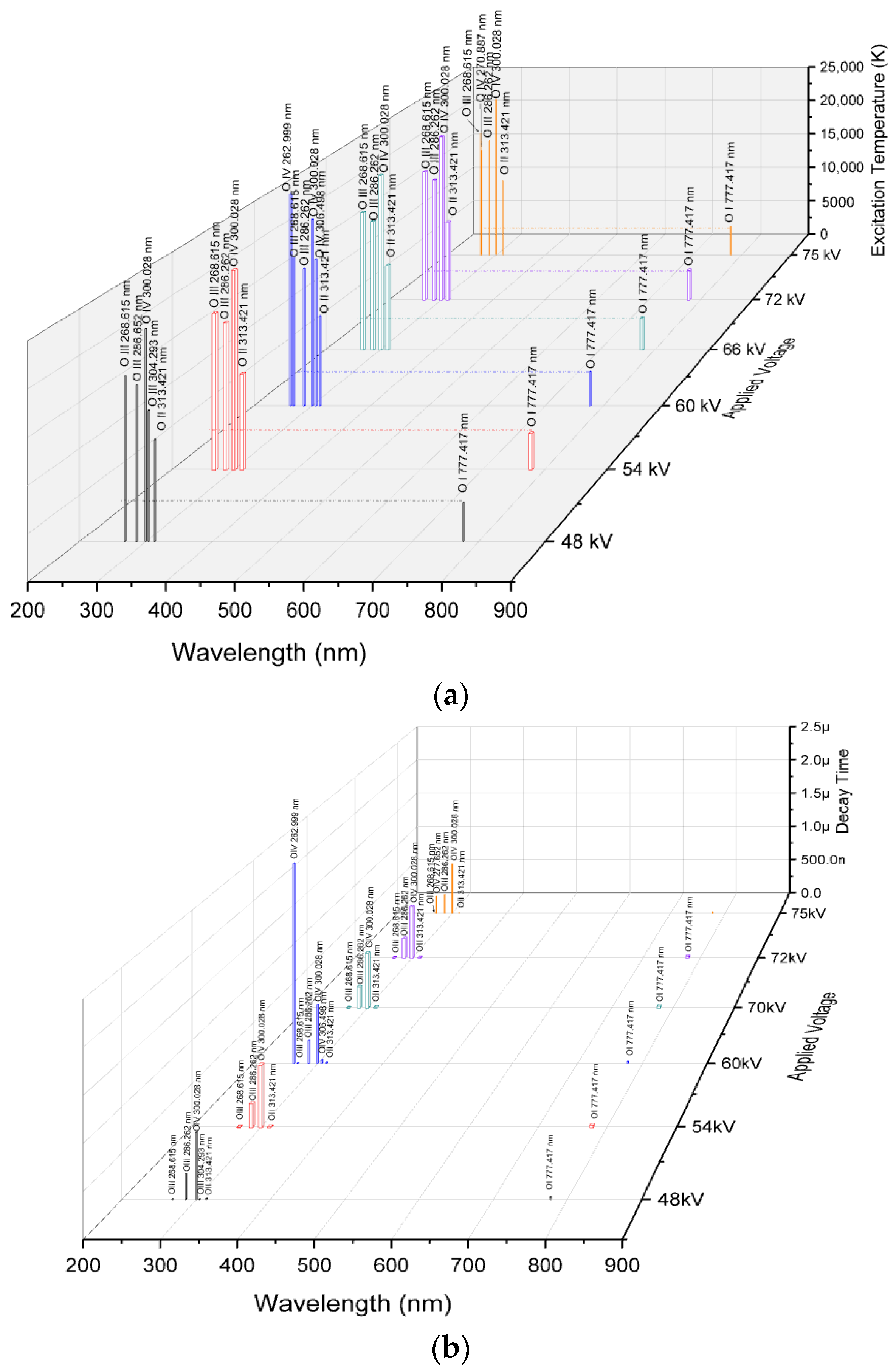

3.2. Lines of the Spectrum during Arc Discharges

4. Discussion

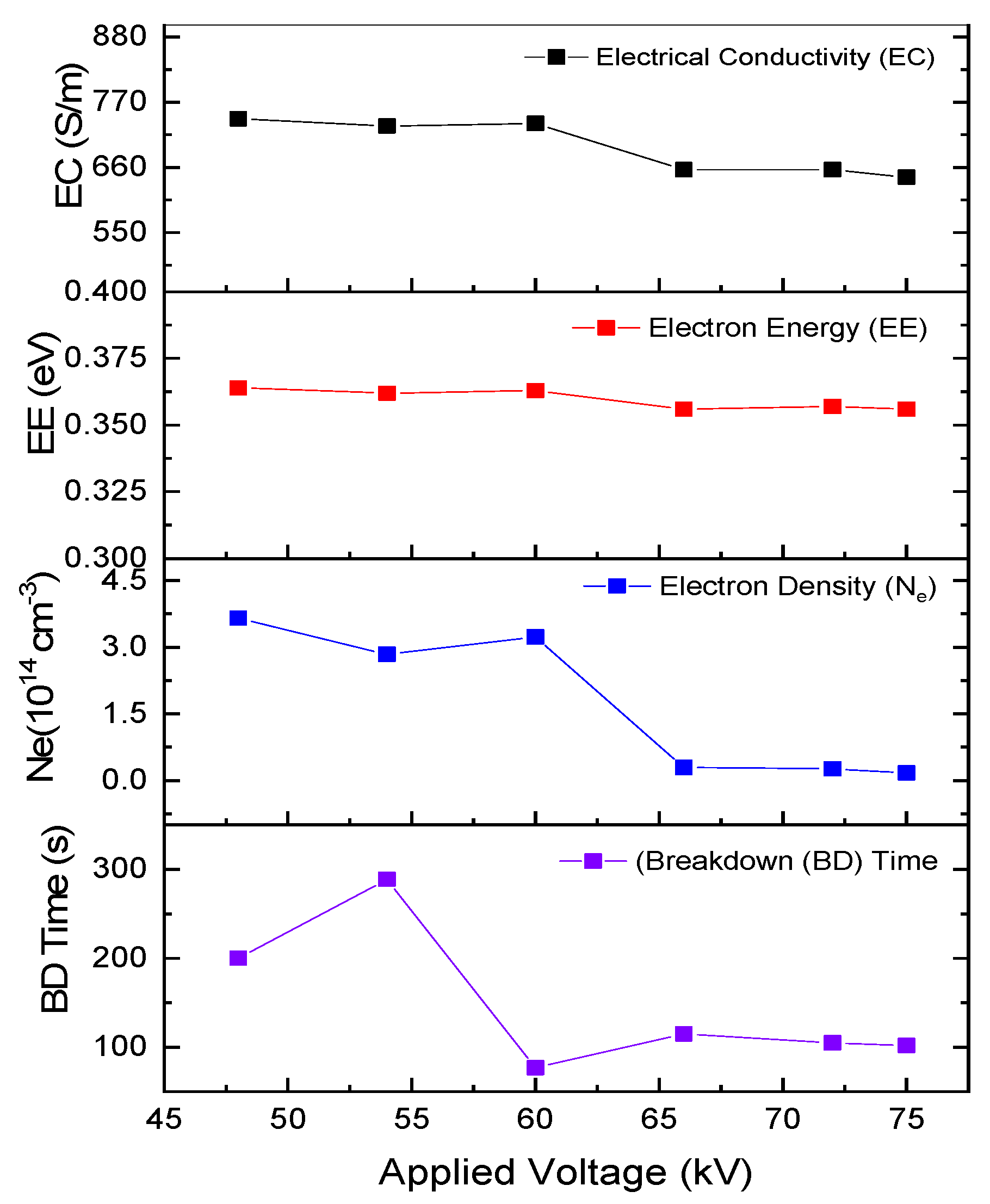

4.1. Breakdown Time Influenced by Peak Intensity

4.2. Impact of Excitation Temperature on Breakdown Time

4.3. Electrical Conductivity of the Channel

5. Conclusions

- Shorter breakdown times can be attributed to the channel conductivity with the increased oxygen excitations observed at +60 kV and +75 kV, compared to other applied voltages. These excitations are particularly evident in the 200–400 nm range, especially in the shorter wavelength region of O IV at 262.999 nm and O III at 270.887 nm at +60 kV, as well as O III at 270.887 nm at +75 kV, due to their higher excited states. In contrast, only two spectral lines, in O IV at 262.999 nm and O III at 270.887 nm, contribute to electron flow within the channel at +60 kV and +75 kV with decay times of 2.5 µs and 0.26 µs, respectively. At +48 kV, even though electron density and electrical conductivity are higher than at +60 kV, electrons do not remain in the air for long because they attach to or recombine with neutral atoms and molecules. The shorter breakdown times at +60 kV and +75 kV are achieved through the dominance of oxygen excitations in the 200–400 nm range, with longer decay times allowing electrons to collide with other neutral atoms and molecules. This facilitates the flow of electrons within the channel to bridge the gap.

- The higher excitation temperature of O IV at 262.999 nm maintains electrons in the hot channel to impede the attachment process by releasing Joule heat at 26,003 K for a decay time of 2.5 µs before the recombination process of the O I line at 777.417 nm occurs in 27 ns, thus enhancing channel conductivity compared to other applied voltages. Consequently, the elevated excitation temperature in O IV at 262.999 nm, with sustained electron presences, contributes to the fast breakdown time of 77 ns at +60 kV. Meanwhile, at +75 kV, the additional temperature in O III at 270.887 nm sustains hot conductivity for approximately 0.26 µs resulting in a breakdown time of 102 ns.

- Understanding the electrical conductivity, electron density, and electron energy of O I at 777.417 nm helps to elucidate the breakdown time process. Examining the temperature transitions of oxygen within the 200–400 nm range provides insight into how electrons are prevented from being lost due to the attachment process in the air.

- Increasing the impulse voltage does not guarantee a quick breakdown time. In contrast, at +60 kV, rapid breakdown is achieved due to more intense oxygen excitations, which produce more electrons in higher excited states to maintain the channel through Joule heat. Therefore, O IV at 262.999 nm and O III at 306.498 nm contributed to this effect. The excitation of O IV at 262.999 nm maintains a hot channel at 26,003 K for up to 2.5 µs keeping the electrons energized and enhancing their ability to collide with neutral atoms and molecules thereby preventing the attachment process. Additionally, these oxygen excitations exhibit higher peak intensities in the shorter wavelength range of 200–400 nm than O I at 777.417 nm, which may contribute to the rapid breakdown.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ikhwanus, M.; Morimoto, T. Rapid Breakdown Time in Positive Impulse Voltages through Spectroscopy Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidis, G.V. Simulation of streamer-to-spark transition in short non-uniform air gaps. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys 1999, 32, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieu, N.; Gordillo-Vazquez, F.J.; Passas, M.; Sanchez, J.; Perez-Invernon, F.J. High-speed spectroscopy of lightning-like discharges: Evidence of molecular optical emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2021, 126, e2021JD035016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijdam, S.; Teunissen, J.; Ebert, U. The physics of streamer discharge phenomena. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowke, J.J. Theory of electrical breakdown in air-the role of metastable oxygen molecules. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1992, 25, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, K.; Iwata, T.; Kojima, H.; Hayakawa, N.; Yanagita, N.; Kato, T.; Rokunohe, T.; Okubo, H. Impulse breakdown mechanism based on discharge propagation process under non-uniform electric field in air. In Proceedings of the Annual Report Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena, Cancun, Mexico, 16–19 October 2011; pp. 534–537. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmond, R.S. The residual streamer channel: Return strokes and secondary streamers. J. Appl. Phys 1984, 56, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marode, E. The mechanism of spark breakdown in air at atmospheric pressure between a positive point and plane. II. Theoretical: Computer simulation of the streamer track. J. Appl. Phys. 1975, 46, 2016–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidis, G.V. Dynamics of streamer breakdown of short non uniform air gaps. J. Phys. D 2005, 38, 3889–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducasse, O.; Eichwald, O.; Merbahi, N.; Dubois, D.; Yousfi, M. Numerical simulation and comparison with experiment for a positive point to plane corona discharges in dry air. In Proceedings of the ICPIG 2007: XXVIII International Conference on Phenomena in Ionized Gases, Prague, Czech Republic, 15–20 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhuri, P.; Mishra, A.K.; Martin, P.M.; McConnell, B.W. The effects of nonstandard lightning voltage waveshapes on the impulse strength of short air gaps. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1994, 9, 1991–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Gao, J.; Xie, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Li, E. Breakdown characteristics of combined air gaps under lightning impulse. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 035024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Gao, J.; Xie, C.; Liu, L.; Song, B.; Peng, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y. Breakdown voltage characteristics of combined air gaps under negative lightning impulse. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kip, A.F. Positive-Point-to-Plane Discharge in Air at Atmospheric Pressure. Phys. Rev. 1938, 54, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, R.; Takezawa, K.; Oda, T. Two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence of atomic oxygen in the afterglow of pulsed positive corona discharge. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 043302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komuro, A.; Suzuki, K.; Yoshida, K.; Ando, A. Characteristics of spatiotemporal variations of primary and secondary streamers under pulsed-voltage in air at atmospheric pressure. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 59, SAAB03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST Atomic Spectra Database Lines Form. Available online: https://physics.nist.gov/ (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Sahin, N.; Tanish, M. Electron temperature estimation of helium plasma via line intensity ratio at atmospheric pressure. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2020, 135, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corliss, C.H.; Tech, J.L. Lifetimes of Energy Levels in Neutral Iron. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. A Phys. Chem. 1967, 71A, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, A.; Kovalgin, A.Y.; Aarmink, A.A.I.; Wolters, R.A.M.; Holleman, J.; Brunets, I.; Schmitz, J. Measurement of electron temperatures of Argon Plasmas in a High-Density Inductively-Coupled Remote Plasma System by Langmuir Probe and Optical-Emission Spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Workshop on Semiconductor Advances for Future Electronics and Sensors, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 23–24 November 2006; pp. 412–418. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Dickinson, A.S. Mutual neutralisation of N+ by O− and O+ by O− in slow collisions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 1997, 124, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janet, L.; Pralhad, R. Foundations of Pulsed Power Technology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 378–383. [Google Scholar]

- Amarasinghe, D.U.; Berg, S.M.; Cooray, V. Correlation between brightness and channel currents of electrical discharges. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2007, 14, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.D.; Christian, H.J. Triggered Lightning Spectroscopy: 2. A Quantitative Analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 3930–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, G. Hundred years of the Saha equation and astrophysics. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2021, 230, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varo, M.P.; Vázquez, F.J.G.; Sánchez, J.; Kieu, N. Experimental radial profiles of early time (<4 μs) neutral and ion spectroscopic signatures in lightning-like discharges. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD036553. [Google Scholar]

- Raizer, Y.P.; Allen, J.E.; Kisin, V.I. Gas Discharge Physics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hegazy, H. Oxygen spectral lines for diagnostics of atmospheric laser-induced plasmas. Appl. Phys. B 2010, 98, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.; Carr, D.; Mitchard, D.; Stone, C.; Haddad, A. Spectroscopic techniques for temperature measurement of laboratory generated lightning arcs. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on High Voltage Engineering, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 28 August–1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Applied Voltage | Breakdown Time (t3 – t2) |

|---|---|

| +42 kV | No breakdown occurs |

| +48 kV | (1.280–1.080) µs = 0.2 µs = 200 ns |

| +54 kV | (1.292–1.003) µs = 0.289 µs = 289 ns |

| +60 kV | (0.968–0.891) µs = 0.077 µs = 77 ns |

| +66 kV | (1.019–0.904) µs = 0.115 µs = 115 ns |

| +72 kV | (0.891–0.786) µs = 0.105 µs = 105 ns |

| +75 kV | (0.850–0.748) µs = 0.102 µs = 102 ns |

| Atoms | Wavelength (nm) | Relative Intensity (a.u) at a Voltage of | Excitation Temperature (K) at a Voltage of | Decay Time (s) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 kV | 54 kV | 60 kV | 66 kV | 72 kV | 75 kV | 48 kV | 54 kV | 60 kV | 66 kV | 72 kV | 75 kV | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | |

| O IV | 262.999 | - | - | 3238 | - | - | - | - | - | 26,003 | - | - | - | 2.5 × 10−6 | |

| O III | 268.615 | 8828 | 6292 | 6019 | 7479 | 11,816 | 10,804 | 17,829 | 18,030 | 18,057 | 17,927 | 17,659 | 17,711 | 6.3 × 10−9 | |

| O III | 270.887 | - | - | - | - | - | 9662 | - | - | - | - | - | 15,212 | 0.26 × 10−6 | |

| O III | 286.262 | 14,674 | 12,682 | 14,459 | 15,952 | 25,030 | 21,936 | 16,813 | 16,885 | 16,820 | 16,772 | 16,556 | 16,619 | 0.28 × 10−6 | |

| O IV | 300.028 | 4353 | 3824 | 4549 | 5374 | 7645 | 6671 | 22,878 | 22,964 | 22,849 | 22,740 | 22,513 | 22,600 | 0.72 × 10−6 | |

| O II | 303.946 | - | 1956 | 2487 | 2846 | 4346 | 3586 | - | - | - | - | - | - | No data | |

| O III | 304.293 | 2329 | - | - | - | - | - | 14,142 | - | - | - | - | - | 5.2 × 10−9 | |

| O III | 306.498 | - | - | 3085 | - | - | - | - | - | 17,943 | - | - | - | 46 × 10−9 | |

| O II | 313.421 | 3595 | 2968 | 3557 | 3519 | 6125 | 5335 | 10,989 | 11,057 | 10,993 | 10,996 | 10,805 | 10,105 | 1.3 × 10−8 | |

| O I | 777.417 | 300 | 347 | 40 | 587 | 538 | 607 | 4227 | 4206 | 4209 | 4133 | 4145 | 4128 | 27 × 10−9 | |

| Parameter | +48 kV | +54 kV | +60 kV | +66 kV | +72 kV | +75 kV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Density () (cm−3) | 3.656 × 1014 | 2.840 × 1014 | 3.233 × 1014 | 2.945 × 1013 | 2.644 × 1013 | 1.756 × 1013 |

| Electron Energy (eV) | 0.364 | 0.363 | 0.363 | 0.356 | 0.357 | 0.356 |

| Electrical Conductivity (S/m) | 742 | 730 | 734 | 656 | 656 | 643 |

| Breakdown time (ns) | 200 | 289 | 77 | 115 | 105 | 102 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ikhwanus, M.; Morimoto, T. Breakdown Time Phenomena: Analyzing the Conductive Channel of Positive Impulse Voltage Discharges under Standard Temperature and Pressure Air Conditions. Energies 2024, 17, 4222. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17174222

Ikhwanus M, Morimoto T. Breakdown Time Phenomena: Analyzing the Conductive Channel of Positive Impulse Voltage Discharges under Standard Temperature and Pressure Air Conditions. Energies. 2024; 17(17):4222. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17174222

Chicago/Turabian StyleIkhwanus, Muhammad, and Takeshi Morimoto. 2024. "Breakdown Time Phenomena: Analyzing the Conductive Channel of Positive Impulse Voltage Discharges under Standard Temperature and Pressure Air Conditions" Energies 17, no. 17: 4222. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17174222

APA StyleIkhwanus, M., & Morimoto, T. (2024). Breakdown Time Phenomena: Analyzing the Conductive Channel of Positive Impulse Voltage Discharges under Standard Temperature and Pressure Air Conditions. Energies, 17(17), 4222. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17174222