Reforming Climate and Development Finance for Clean Cooking

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Clean Cooking Access Deficit

1.2. Funding Deficit

1.3. Development Finance Institutions

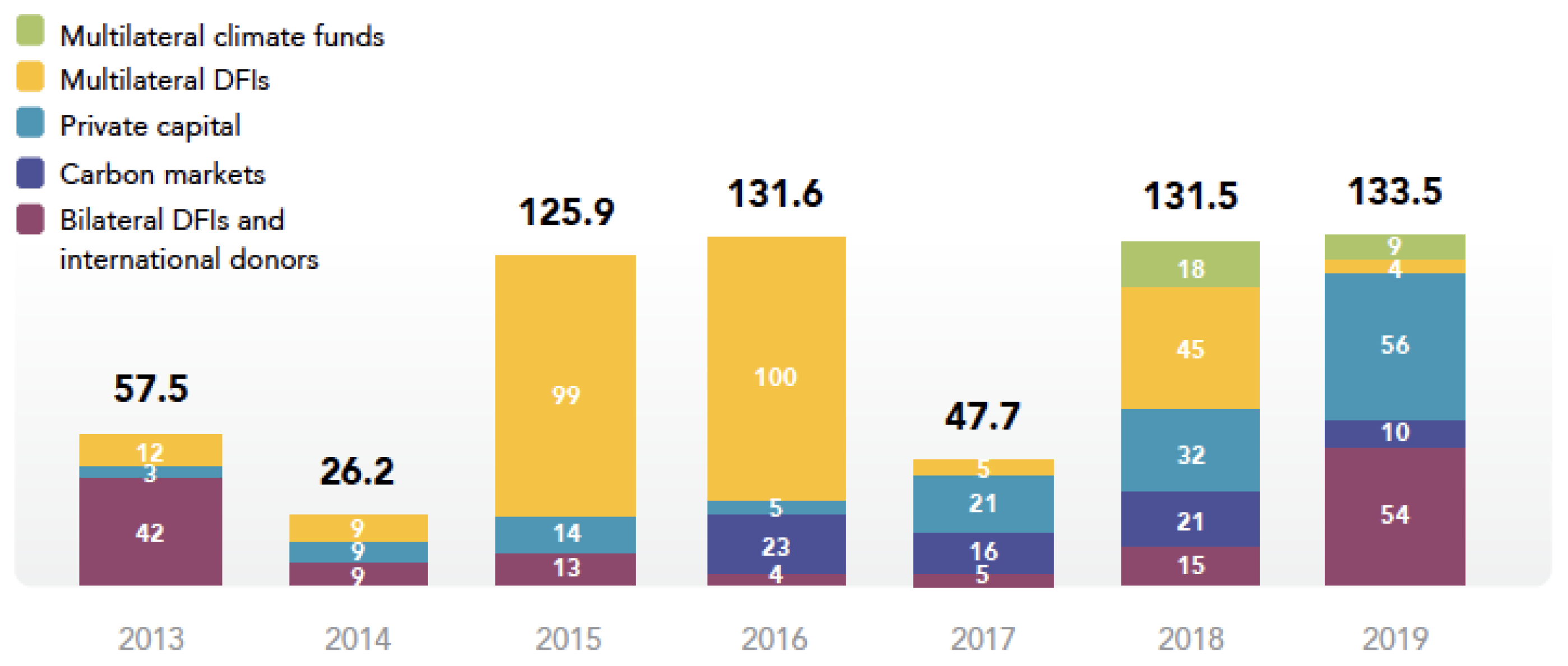

1.4. Data on Finance Flows

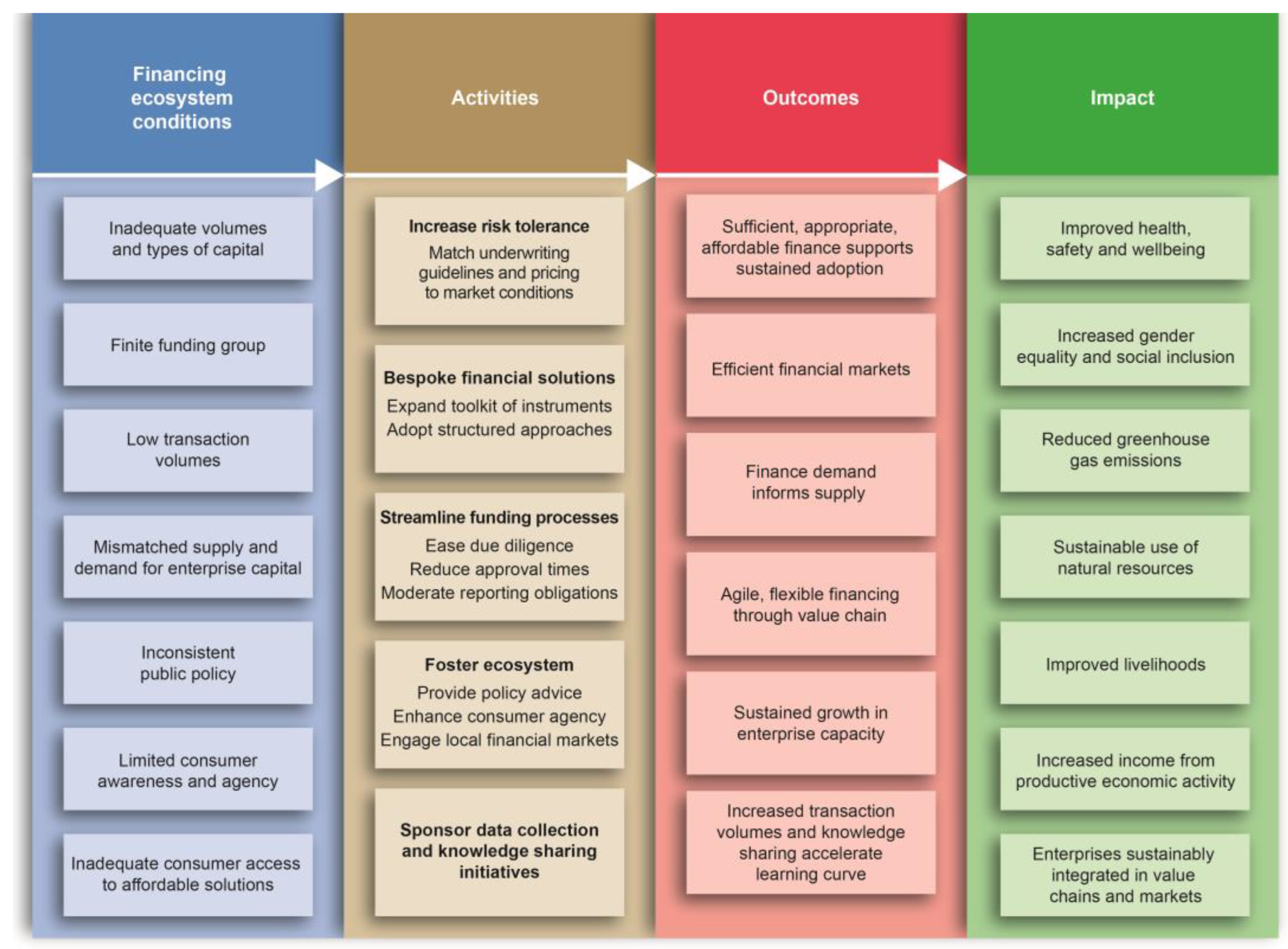

1.5. The Reform Agenda

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. DFIs’ Role in Clean Cooking Markets

3.1.1. Ecosystem Building

Clean cooking can be invisible to policymakers because the people who are experiencing the pressures and pain of lack of access are far away from the capital cities. They don’t have access to a voice, they don’t talk to decision makers, they’re easily forgotten about.[MO3]

One thing we all, myself included, [should do] is to really put yourself in the position of those that need the solutions. I don’t think that happens often enough. I spent time in the field talking to a woman who said ‘my day is only about cooking. It starts early in the morning collecting wood, and then I cook for ten people and then clean up. And that’s my day’.[PF2]

Accessing public finance is quite difficult, even when you look at it from a developing country like us. It’s more challenging. How are we going to unlock that process or how can we make it easier to access that funding? The [emissions] contribution from our country is negligible. But we are one of the most vulnerable countries. So it’s not created by us but we are feeling the impacts of climate change. We have not been supported enough to meet our climate-related funding requirements. I think public financial institutions should focus on that point and then make the deal process easier, or even look at country funding envelopes.[PF3]

We have to look at the inclusive aspects, on the socioeconomic aspects rather than the economic aspects. Everybody talks about the energy transition from the supply side. Behaviour change will, to a certain extent, determine the market where supply needs to follow.[MO1]

Addressing some of the systemic issues that prevent more companies from becoming investable in the space is a very good use of public funding, if it’s done right.[PF1]

It’s hard to find the right local entrepreneurs, but if you have them, I think they can make much more speed, because they know the game locally. Local entrepreneurs find a way to the right people.[CC2]

Technical assistance, sometimes it’s as good as money and sometimes even better. But for the most part it’s less good than money and at worst it’s even a negative. Some programs kind of force you to. They assume that you are not capable.[CC1]

3.1.2. Financial Catalysts

It’s really a remarkable space. When you think that over the last years, annually, there’s just a few hundred million [dollars] being invested in this sector, while there are huge implications for climate as well as a whole raft of other SDGs. It’s one of the highest impact potential investments but still it’s received such little focus and attention.[MO4]

3.2. Characteristics of DFI Finance for Clean Cooking

3.2.1. Bureaucratic, Slow, and Rigid

The challenge is that public finance doesn’t operate at the speed of private equity. And they need to if they’re going to operate in this space. You’ve got to be able to transact in a way that is commercial.[CC5]

The frustration that we had working with DFIs, it was just too slow. I mean, everything’s so frantic in the private sector that if you don’t get an answer, you call the next number.[CF3]

There’s a perception that DFIs and multilaterals have a particular way of working and like to stay within that. Sort of ‘swim lanes’, as people might say. And to jump outside of that takes an incredible bureaucratic effort.[PF5]

It’s a bureaucratic process, and our institution alone cannot even directly approach [GCF]. So we have to go through the government bureaucratic processes, and the government is not supportive of our request. How can that issue be addressed?[PF3]

You often end up doing things that you put in your proposal three years ago, and it’s not relevant. Some are extremely rigid with it, others less so. If you have a blowtorch in your back to deliver to get the next payment, you may sacrifice for low quality because essentially your most important customer at a certain stage is not the customer, it’s the grant giver.[CC1]

The amount of costs throughout the chain to ensure that money is spent properly can be astronomically high. A direct transfer, even given the risks, may still come out better as we’ve seen in the disaster response sector.[CC4]

If we’re talking about custody of taxpayers’ money, if that is justifying how some programs are running, including the risk aversion, is that really what taxpayers want? Do they understand how some of these programs are actually run? If money was earmarked for climate finance in sub-Saharan Africa, and if money is not paid out, what happens to that money? I feel there’s an opaqueness in the whole sector. If it cost taxpayers a million dollars, how much of that reaches the distribution company, and how much reaches the end beneficiary?[CC1]

3.2.2. Risk Aversion and Fear of Failure

I don’t think the public money out there has an interest in actually solving this problem to the scale required, otherwise it would be solved. What have they delivered to date? Very little in forty years.[CC7]

I mean the clean cooking sector has been around for a while now. If the reality is that today, in 2023, we’re still calling it a nascent sector, that essentially means that a lot of the public financing flows that were intended to come to the market haven’t in the way that would have enabled the market to move from nascent.[PF4]

Achieving market rate returns with that baked into your growth requires businesses to be uncommonly profitable and to grow uncommonly fast in markets where we know that’s harder to do than in other places. And so my view of a public finance institution is that it should be taking risks and catalysing growth. Their view is that it should be operating for a very long time, preserving its capital and preserving its high bond rating, and its ability to access the capital markets at low cost.[PF6]

It’s like we need to throw out the net wide to get the unicorns, and many will fail, whatever fail means, because it contributes to the [sector] understanding.[CC1]

If you really want to go and build an impact unicorn in whatever sector, then you’re going to have to expect that eighty percent of your best will fail. And you get fired for that sort of stuff in public sector land.[CC7]

In emerging markets and in a nascent sector like clean cooking, doing the right thing involves taking risk and sometimes failing, and DFIs and MDBs often don’t have the mandate required to develop a nascent sector. While we were fortunate with numerous DFIs who bucked the trend, in many cases their incentives don’t lead them to extend sufficiently concessional capital (in terms of risk and/or return expectations) to mobilise private capital.[PF1]

To me, the best development would be if public finance procured validated outcomes. So, for example, SDG impact or gender impact. Or climate impact. And there are some very good proxies [to enable this], for example, payments, electronic payments, mobile money.[CC1]

3.2.3. Limited Range of Financial Solutions

RBFs have almost no risk for the donor. They actually keep a lot of the sector in hibernation, because RBF doesn’t really enable things to grow. Companies just get rewarded for particular behaviour.[DA3]

There is definitely this grey zone between outright grants and semi-commercial investment or concessional finance. I believe that’s where a lot more intervention is needed from public funding. And given that public funding is scarce, of course it needs to blend with other forms of capital to make the scale equation work.[MO4]

We have public finance resources, we have aid, we have grants, and we also have guarantee instruments. One way to look at it is as the different types of finance that a sector, and particularly companies, need to scale and grow and establish themselves.[DA2]

You need multiple instruments available in the markets; some companies need a bit more on the equity side and some more on the loan side. But in the end, these bigger and smaller companies, they all need to have access to finance, and public organisations need to make sure that this somehow happens.[DA3]

So, these improved cookstoves, people used them for a while. They are too slow to cook, and they are still using the same dirty fuel that we tell people not to use… Therefore, people don’t see the reason for adopting them. But I would blame this on the development partners who have been pushing down the throats of Africans to use improved cookstoves[66].

I think it’s these companies that will keep the ecosystem going and they will go to places where, let’s say, the marginal returns for a big company are just not enough.[DA3]

Mainstream clean cooking solutions/technology are indeed too often ignored in the global discourse, whereas innovations (pay-as-you-go, forced draft gasifiers, briquettes, etc.), products in a pilot phase and/or serving niche markets, are getting a lot more attention and funding.[DA1]

The affordability gap is a huge issue which can essentially only be covered by a smart subsidy approach. And I think that’s a very tough combination still for many donors to figure out what the sweet spot is.[MO4]

3.2.4. Strategic Misalignment

There’s all this talk about the financing gap in clean cooking, but not nearly enough conversation around what it is you’re trying to finance, and what you’re trying to do with that finance.[CC5]

It’s not that they’re not fit for purpose. It’s just that they’re not doing it. The world is awash with maps and roadmaps. But actually, I don’t think we’ve got the right engine for driving decisions, and that is a fundamental condition for scale. Do we need to think differently about the problem, because we can’t scale outcomes unless we start talking about it in a different way and grappling with it.[CF2]

If there had been even less public investment than there was, maybe we would have been already at the stage of electric cooking 10 years ago.[CC3]

Public financing agencies have particular buckets of money which need to be deployed in a particular way. They are constrained by terms and conditions and specific characteristics that they need to meet. So there’s a set of guidelines, whether that be from a debt perspective or an equity perspective. They’ll have a credit policy sitting there. They’ll have a set of underwriting perspectives from the equity side. Yet they’re often being developed for markets which are already established rather than those really early-stage markets. And I think that’s where you need that high level of flexibility to come into structures so that you’re actually fitting the financing structure to the need versus trying to fit the need to the financing structure.[PF5]

Public finance has a very key role to play of being able to price in not just commercial, but social and environmental returns of an intervention. If an intervention could already deliver pure commercial returns, there’d be no additionality and no need for public finance.[CC4]

4. Discussion

We’ve had a whole debate that’s been enormously successful in many respects since Paris, about sustainable finance and green finance and sustainable infrastructure. There’s been an absolute gap between that tier of debate and the one underneath, which is how do you deliver outcomes? But engaging with finance practitioners in that debate points to things that have plain names, but are unfashionable in the sustainable finance world, like policy, regulation, public finance.[CF2]

While the SDGs present a commendable blueprint for achieving inclusive and sustainable growth, they do not yet provide a detailed investment strategy or guide for actualizing that vision[73].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Government of Barbados. The 2022 Bridgetown Initiative for the Reform of the Global Financial Architecture. 2022. Available online: https://pmo.gov.bb/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-2022-Bridgetown-Initiative.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- French Presidency. Summit for a New Global Financing Pact Multilateral Development Banks Vision Statement. 2023. Available online: https://nouveaupactefinancier.org/pdf/multilateral-development-banks-vision-statement.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- African Heads of State and Government. The African Leaders Nairobi Declaration on Climate Change and Call to Action. 6 September 2023. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/2023/09/08/the_african_leaders_nairobi_declartion_on_climate_change-rev-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- United Nations. Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 6: Reforms to the International Financial Architecture. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-international-finance-architecture-en.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines. Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, M.; Angelou, N. Beyond Connections: Energy Access Redefined ESMAP Technical Report; 008/15; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. In Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 19/35; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Res. 70/1 of 25 September 2015.

- IEA; IRENA; UNSD; World Bank; WHO. Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. A Vision for Clean Cooking Access for All; IEA: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ESMAP. The State of Access to Modern Energy Cooking Services; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Household Air Pollution: Key Facts. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/household-air-pollution-and-health (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Puzzolo, E.; Fleeman, N.; Lorenzetti, F.; Rubinstein, F.; Li, Y.; Xing, R.; Shen, G.; Nix, E.; Maden, M.; Bresnahan, R.; et al. Estimated health effects from domestic use of gaseous fuels for cooking and heating in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njenga, M.; Gitau, J.K.; Mendum, R. Women’s work is never done: Lifting the gendered burden of firewood collection and household energy use in Kenya. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 77, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V. Blanket bans on fossil fuels hurt women and lower-income countries. Nature 2022, 607, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ENERGIA; World Bank—Energy Sector Management Assistance Program; UN Women. Policy Brief 12 Global Progress of SDG7—Energy and Gender; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ngum, S.; Kim, L. Powering a Gender-Just Energy Transition; Green Growth Knowledge Partnership: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sciences Po; ESMAP. The Smart Economics of Clean Cooking: Placing Women at the Center of the Energy Access Development Agenda. 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencespo.fr/students/sites/sciencespo.fr.students/files/sciencespo-projet-co-policy-brief-smart-economics-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- 60 Decibels. Why Off-Grid Energy Matters 2024. 2024. Available online: https://60decibels.com/insights/why-off-grid-energy-matters-2024/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Gill-Wiehl, A.; Kammen, D.M. A pro-health cookstove strategy to advance energy, social and ecological justice. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mperejekumana, P.; Shen, L.; Saad Gaballah, M.; Zhong, S. Exploring the potential and challenges of energy transition and household cooking sustainability in sub-sahara Africa. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiolo, H.H.; Marwah, H.; Leach, M. The Emergence of Large-Scale Bioethanol Utilities: Accelerating Energy Transitions for Cooking. Energies 2023, 16, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA; IRENA; UNSD; World Bank; WHO. Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UN ESCAP. Universal Access to all: Maximizing the Impact of Clean Cooking. 2021. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12870/3506 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Shittu, I.; Rais Bin Abdul Latiff, A.; Aisyah Baharudin, S. Closing the clean cooking gap: Which policies and institutional qualities matter? Energy Policy 2024, 185, 113964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, A.O.; Evans Osei Opoku, E.; Dogah, K.E. The political economy of energy transition: The role of globalization and governance in the adoption of clean cooking fuels and technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 186, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook; IEA: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clean Cooking Alliance. 2023 Clean Cooking Industry Snapshot. Available online: https://cleancooking.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/CCA-2023-Clean-Cooking-Industry-Snapshot.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Sustainable Energy for All; Climate Policy Initiative. Energizing Finance: Understanding the Landscape 2021; Sustainable Energy for All: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. What You Need to Know about Concessional Finance for Climate Action. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/09/16/what-you-need-to-know-about-concessional-finance-for-climate-action (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- OECD. Development Finance Institutions and Private Sector Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/development/development-finance-institutions-private-sector-development.htm (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- te Velde, D.W. The Role of Development Finance Institutions in Tackling Global Challenges; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MECS; Energy 4 Impact. Modern Energy Cooking: Review of the Funding Landscape. 2022. Available online: https://mecs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/MECS-Landscape-report_final-17-02-2022.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Marbuah, G.; te Velde, D.W.; Attridge, S.; Lemma, A.; Keane, J. Understanding The Role of Development Finance Institutions in Promoting Development: An Assessment of Three African Countries; SEI: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, G.; Rowlands, D. The Catalytic Effect of Lending by the International Financial Institutions. In International Finance and the Developing Economies; Bird, G., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, A. Development Impact of DFIs: What Are Their Impacts and How Are They Measured? Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD DAC Blended Finance Principles. 2018. Available online: https://web-archive.oecd.org/2022-08-19/469783-OECD-Blended-Finance-Principles.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- DFI Working Group on Blended Concessional Finance for Private Sector Projects. Joint Report, March 2023 Update. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/mgrt/2023-03-dfi-bcf-joint-report.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Mutambatsere, E.; Schellekens, P.; The Why and How of Blended Finance. International Finance Corporation World Bank Group Discussion Paper. 2020. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/856201613568586386/pdf/The-Why-and-How-of-Blended-Finance.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Kouwenberg, R.; Zheng, C. A Review of the Global Climate Finance Literature. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Adoption of the Paris Agreement. In Proceedings of the 21st Conference of the Parties, Paris, France, 30 November–13 December 2015. UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.2 Decision 1.CP.21, Article 9. [Google Scholar]

- Long, S.; Lucey, B.; Kumar, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z. Climate finance: What we know and what we should know? J. Clim. Financ. 2022, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Development Bank; Asian Development Bank; Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank; Council of Europe Development Bank; European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; the European Investment Bank; Inter-American Development Bank Group; Islamic Development Bank; New Development Bank; World Bank Group. 2022 Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Climate Finance; European Investment Bank: Luxembourg, 2023; Version 1.1. [Google Scholar]

- International Development Finance Club. Mission & Vision. 2024. Available online: https://www.idfc.org/mission-vision/ (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Sixteenth Session, Held in Cancun from 29 November to 10 December 2010. Addendum. Part two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties at Its Sixteenth Session, 2011; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2010/7/Add.1 Decision 1.CP.16, paragraph 102.

- Green Climate Fund Independent Evaluation Unit. 2023 Annual Report; Green Climate Fund Independent Evaluation Unit: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- G7 Climate, Energy and Environment Ministers. Meeting Communiqué. 2024. Available online: https://www.g7italy.it/wp-content/uploads/G7-Climate-Energy-Environment-Ministerial-Communique_Final.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- IEA. The Clean Cooking Declaration: Making 2024 the Pivotal Year for Clean Cooking. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/news/the-clean-cooking-declaration-making-2024-the-pivotal-year-for-clean-cooking (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Coldrey, O.; Lant, P.; Ashworth, P. Elucidating Finance Gaps through the Clean Cooking Value Chain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, W.C.; Colomb, G.G.; Williams, J.M.; Bizup, J.; FitzGerald, W.T. The Craft of Research, 4th ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.P. Snowball Sampling: Introduction; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Adoption of the Paris Agreement. In Proceedings of the 21st Conference of the Parties, Paris, France, 30 November–11 December 2015. UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1 Decision 1.CP.21, Article 4, paragraph 2. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Energy. Achieving Universal Access and Net-Zero Emissions by 2050: A Global Roadmap for Just and Inclusive Clean Cooking Transition; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor, S.; Brown, E.; Scott, N.; Leach, M.; Clements, A.; Leary, J. Mutual Support—Modern Energy Planning Inclusive of Cooking—A Review of Research into Action in Africa and Asia since 2018. Energies 2022, 15, 5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Khan, M.R.; Haque, N. Does climate finance enhance mitigation ambitions of recipient countries? Earth Syst. Gov. 2023, 17, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Jomo, K.S. The Climate Finance Conundrum. Development 2022, 65, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Scholtens, B.; Homroy, S. Rebalancing climate finance: Analysing multilateral development banks’ allocation practices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 101, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, S.A. Clean cooking for all? A critical review of behavior, stakeholder engagement, and adoption for the global diffusion of improved cookstoves. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 68, 101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiamang, G. The Call for Action: African Startups and Small Businesses Demand More Than Just Capacity Building. 2 May 2024. Available online: https://medium.com/@grannylesiamang/the-call-for-action-african-startups-and-small-businesses-demand-more-than-just-capacity-building-b135b9de371c (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- LEAD at Krea University. Clean Cookstoves: Impact and Determinants of Market Success. 2021. Available online: https://ifmrlead.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Clean-Cookstoves-2021-Report.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- ESMAP. What Drives the Transition to Modern Energy Cooking Services? A Systematic Review of the Evidence; Technical Report 015/21; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Energy for All; South Pole. Energizing Finance: Missing the Mark 2020; Sustainable Energy for All: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MECS; Energy 4 Impact. Clean Cooking: Results-Based Financing as a Potential Scale up Tool for the Sector. 2021. Available online: https://mecs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Clean-cooking-results-based-financing-as-a-potential-scale-up-tool-for-the-sector.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Stritzke, S.; Sakyi-Nyarko, C.; Bisaga, I.; Bricknell, M.; Leary, J.; Brown, E. Results-Based Financing (RBF) for Modern Energy Cooking Solutions: An Effective Driver for Innovation and Scale? Energies 2021, 14, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoy, C.M.; Carter, P.; Lemma, A. Development Finance Institutions Come of Age: Policy Engagement, Impact and New Directions; Centre for Strategic and International Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ESMAP. Multi-tier Framework for Energy Access. 2022. Available online: https://mtfenergyaccess.esmap.org/methodology/cooking (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Perros, T.; Tomei, J.; Parikh, P. Stakeholder perspectives on the future of clean cooking in sub-Saharan Africa and the role of pay-as-you-go LPG in expanding access. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 112, 103494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill-Wiehl, A.; Ray, I.; Kammen, D. Is clean cooking affordable? A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Van der Vleuten, F. Balancing Opportunity and Risk: Harnessing Carbon Markets to Expand Clean Cooking. 13 January 2023. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/energy/balancing-opportunity-and-risk-harnessing-carbon-markets-expand-clean-cooking (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Gill-Wiehl, A.; Kammen, D.M.; Haya, B.K. Pervasive over-crediting from cookstove offset methodologies. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stritzke, S.; Bricknell, M.; Leach, M.; Thapa, S.; Khalifa, Y.; Brown, E. Impact Financing for Clean Cooking Energy Transitions: Reviews and Prospects. Energies 2023, 16, 5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Finance Corporation. Clean Impact Bond: Mobilizing Finance for Clean Cooking; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Convergence. The State of Blended Finance 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.convergence.finance/resource/state-of-blended-finance-2024/view (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Mazzucato, M. Financing the Sustainable Development Goals through Mission-Oriented Development Banks, UN DESA Policy Brief Special Issue; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Theory of Change. What Is Theory of Change? 2024. Available online: https://www.theoryofchange.org/what-is-theory-of-change/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Polzin, F.; Sanders, M.; Serebriakova, A. Finance in global transition scenarios: Mapping investments by technology into finance needs by source. Energy Econ. 2021, 99, 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandary, R.R.; Gallagher, K.S.; Zhang, F. Climate finance policy in practice: A review of the evidence. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Identifier Code | No. of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Clean cooking company | CC | 7 |

| Climate finance | CF | 3 |

| Development agency | DA | 3 |

| Impact investor/private fund/foundation | PF | 6 |

| Multilateral organisation/international financial institution | MO | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coldrey, O.; Lant, P.; Ashworth, P.; LaRocco, P.; Eibs Singer, C. Reforming Climate and Development Finance for Clean Cooking. Energies 2024, 17, 3720. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17153720

Coldrey O, Lant P, Ashworth P, LaRocco P, Eibs Singer C. Reforming Climate and Development Finance for Clean Cooking. Energies. 2024; 17(15):3720. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17153720

Chicago/Turabian StyleColdrey, Olivia, Paul Lant, Peta Ashworth, Philip LaRocco, and Christine Eibs Singer. 2024. "Reforming Climate and Development Finance for Clean Cooking" Energies 17, no. 15: 3720. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17153720

APA StyleColdrey, O., Lant, P., Ashworth, P., LaRocco, P., & Eibs Singer, C. (2024). Reforming Climate and Development Finance for Clean Cooking. Energies, 17(15), 3720. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17153720