Diagnosing Energy Poverty in Portugal through the Lens of a Social Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Related Work

1.3. Contribution

1.4. Paper Organization

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The REVERTER Project

- Create nine roadmaps.

- Facilitate the renovation of more than 800 houses during the implementation of the project and within five years after its end.

- Create a positive impact on more than 3000 vulnerable people.

- Demonstrate the effectiveness and replicability of the proposed solutions among 20,000 energy-vulnerable households.

- Trigger the investment of about EUR 8 million in sustainable energy and primary energy savings/renewable energy to generate 12.3 GWh/year during the implementation of the project and within 5 years after its end.

- Use 10 existing and new “tailor-cut” complementary indicators to measure energy poverty.

- Create a knowledge database and analyze deep renovation measures by employing economic, environmental (via LCA), technical, and social criteria, and by using cost–benefit and multicriteria approaches.

- Identify viable financial schemes, support best practices, and shape future policies aimed at alleviating EP through energy retrofits by creating/adapting 15 pieces of legislation, policies, or strategies during the implementation of the project and within 5 years after its end.

- The identification of energy-vulnerable households;

- The analysis of building stock;

- The assessment of deep renovation measures;

- The establishment of “one-stop-shops” (OSS);

- Capacity building using energy ambassadors, awareness, and training campaigns.

2.2. Social Survey

- Test the EP identification methodology;

- Develop a set of tailor-made materials that will be used in the one-stop shops to support community capacity-building programs;

- Recruit households willing to participate in REVERTER’s field activities, e.g., via home visits;

- Facilitate the development of roadmaps;

- Identify best practices in terms of delivering energy advice during local engagement initiatives/campaigns for low-income households;

- Recognize key incentives for energy efficiency retrofitting for each category of property tenure type, which is necessary for the design of the one-stop shops.

- (a)

- Local context (national/regional/neighborhood)—this section was designed to identify the locally available support mechanisms, users’ awareness of their existence, and possible improvements to them. From this knowledge, using the strategies in the other pilot cities, existing mechanisms can be improved and inspire the development of new ones.

- (b)

- Information on building envelopes and comfort systems—the information collected in this section helps to discover more about the building and the way it is used, helping to design roadmaps.

- (c)

- Household-related questions, which aim to validate indicators used to quantify energy poverty and existing European statistics with evidence-based information.

- (d)

- Individual household demographics, including the postal code, are used in order to allow matching between the answers with local climate conditions.

- The impact of the building characteristics and mechanical systems on the comfort levels and energy bills;

- The reasons to not apply for support programs and the willingness to pay for efficiency improvements;

- The correlation between income, energy bills, and self-declared comfort;

- The levels of energy poverty when considering different options in terms of indicators.

- An inability to keep the home adequately warm;

- An inability to keep the home adequately cool;

- Cutbacks or restrictions in essential products and services;

- ‘Ten-Percent-Rule’—when the energy expenditure is more than 10% of income [36];

- Arrears in energy bills.

3. Survey Results

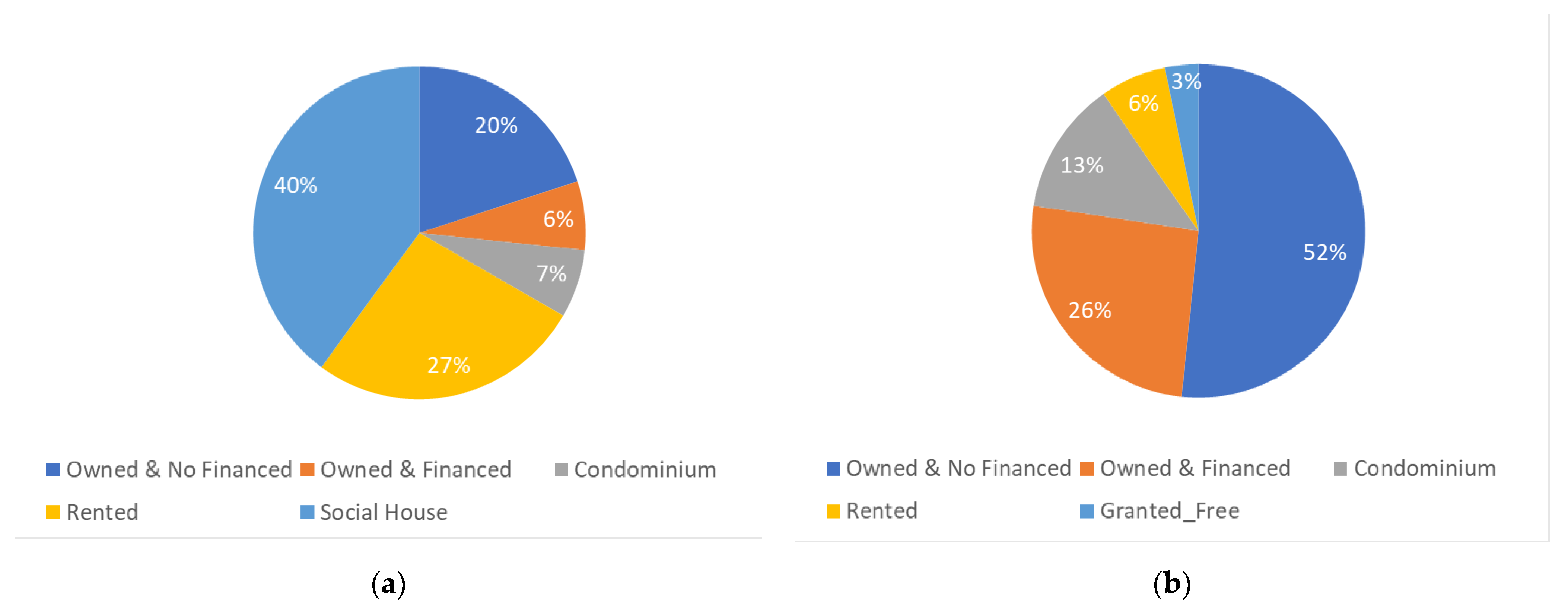

3.1. Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics

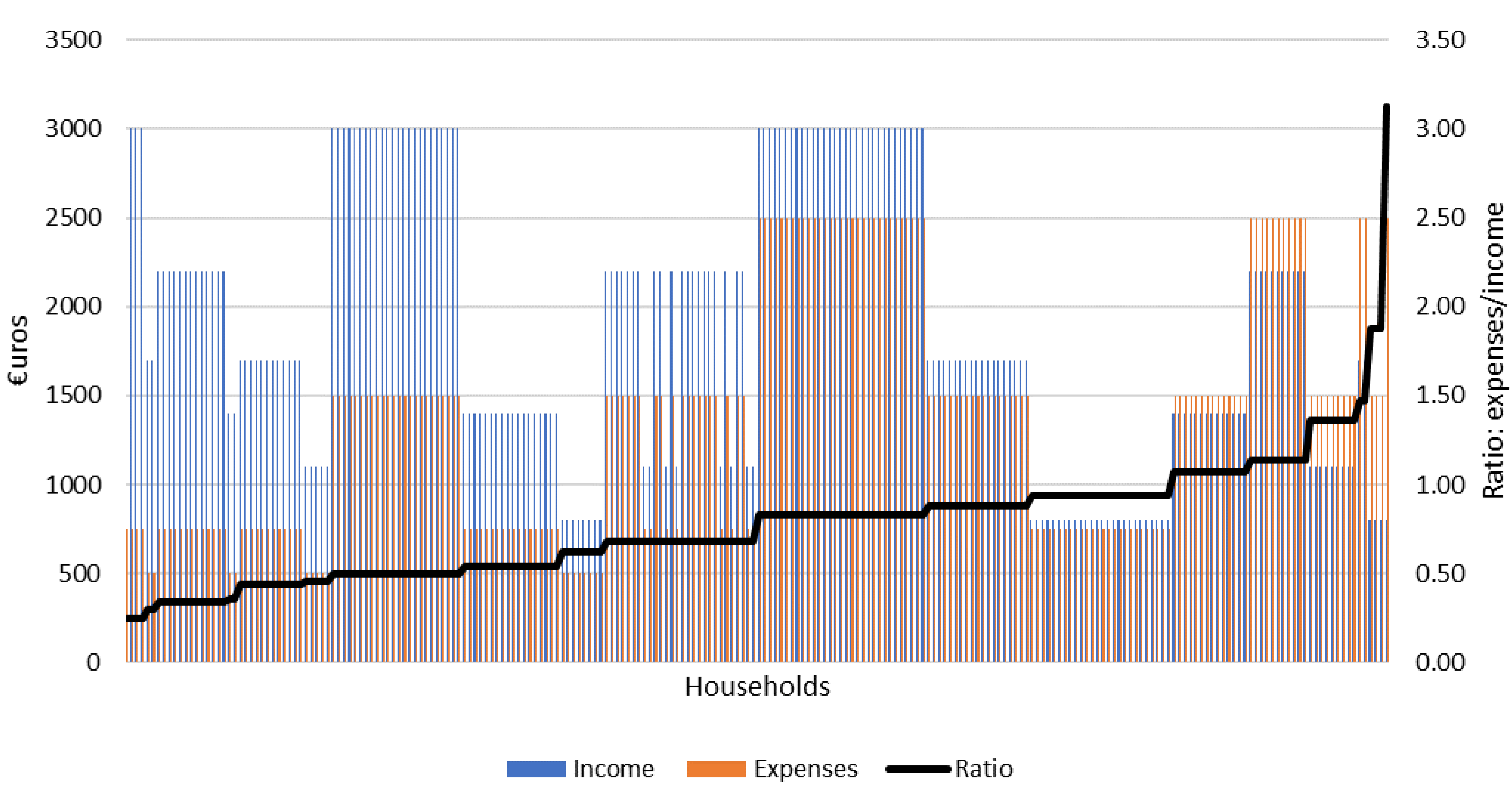

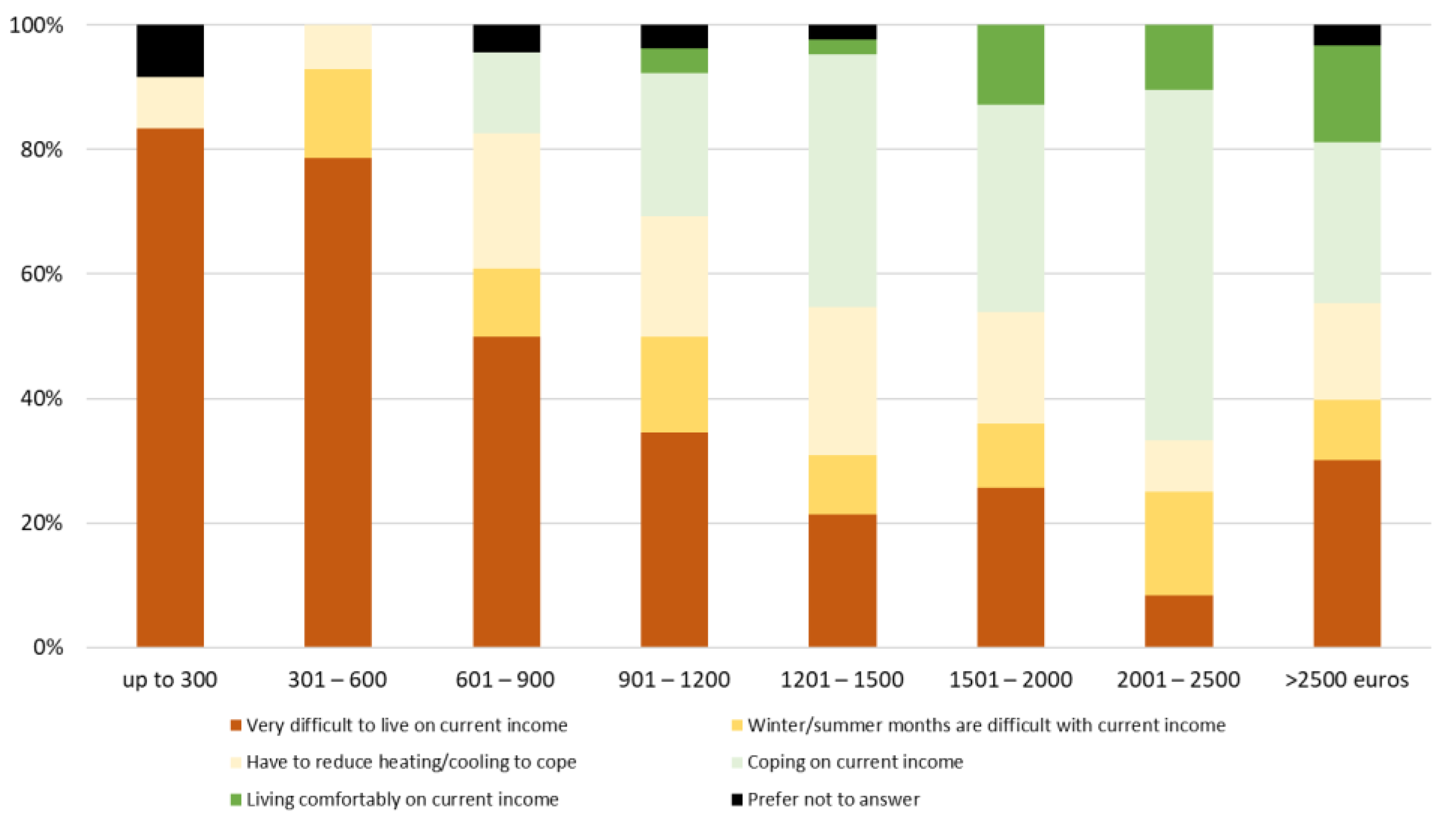

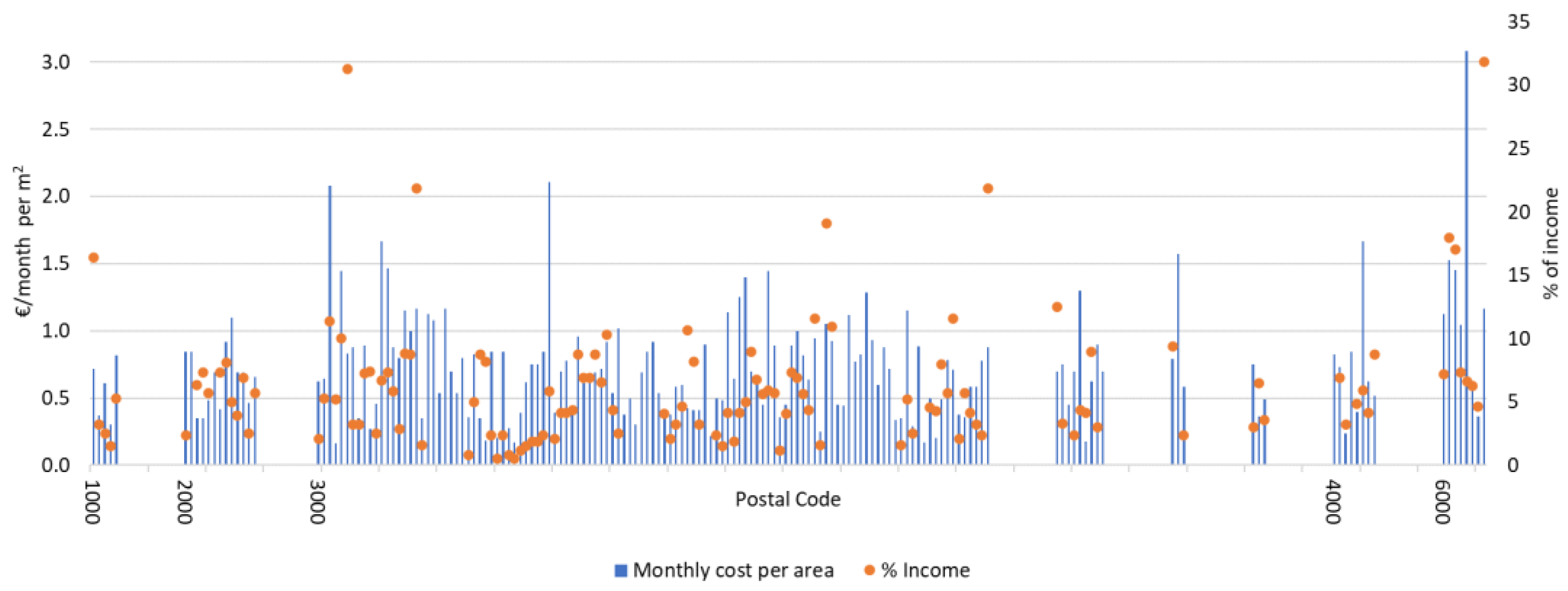

3.2. Income and Expenditure

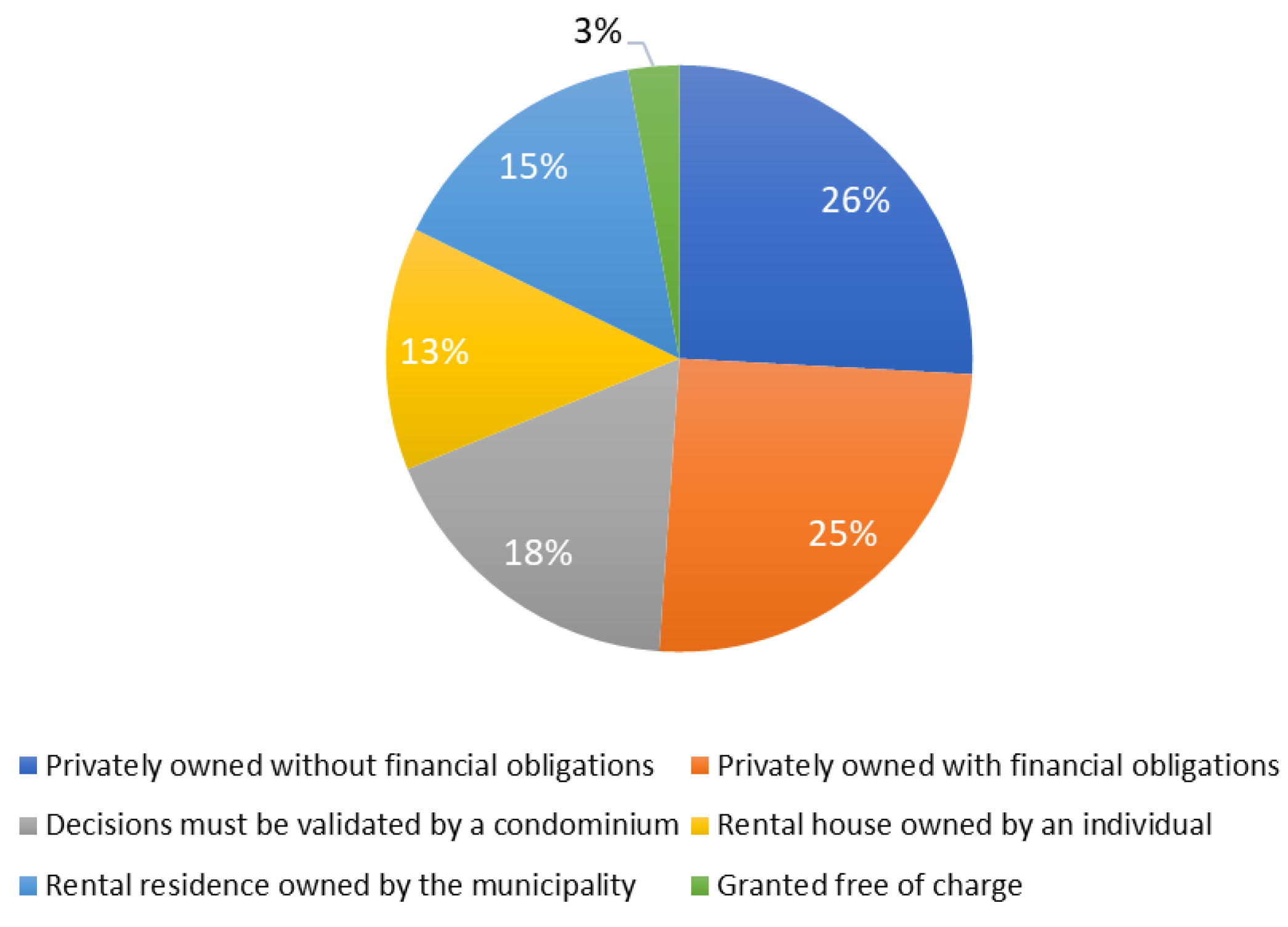

3.3. Housing Characteristics

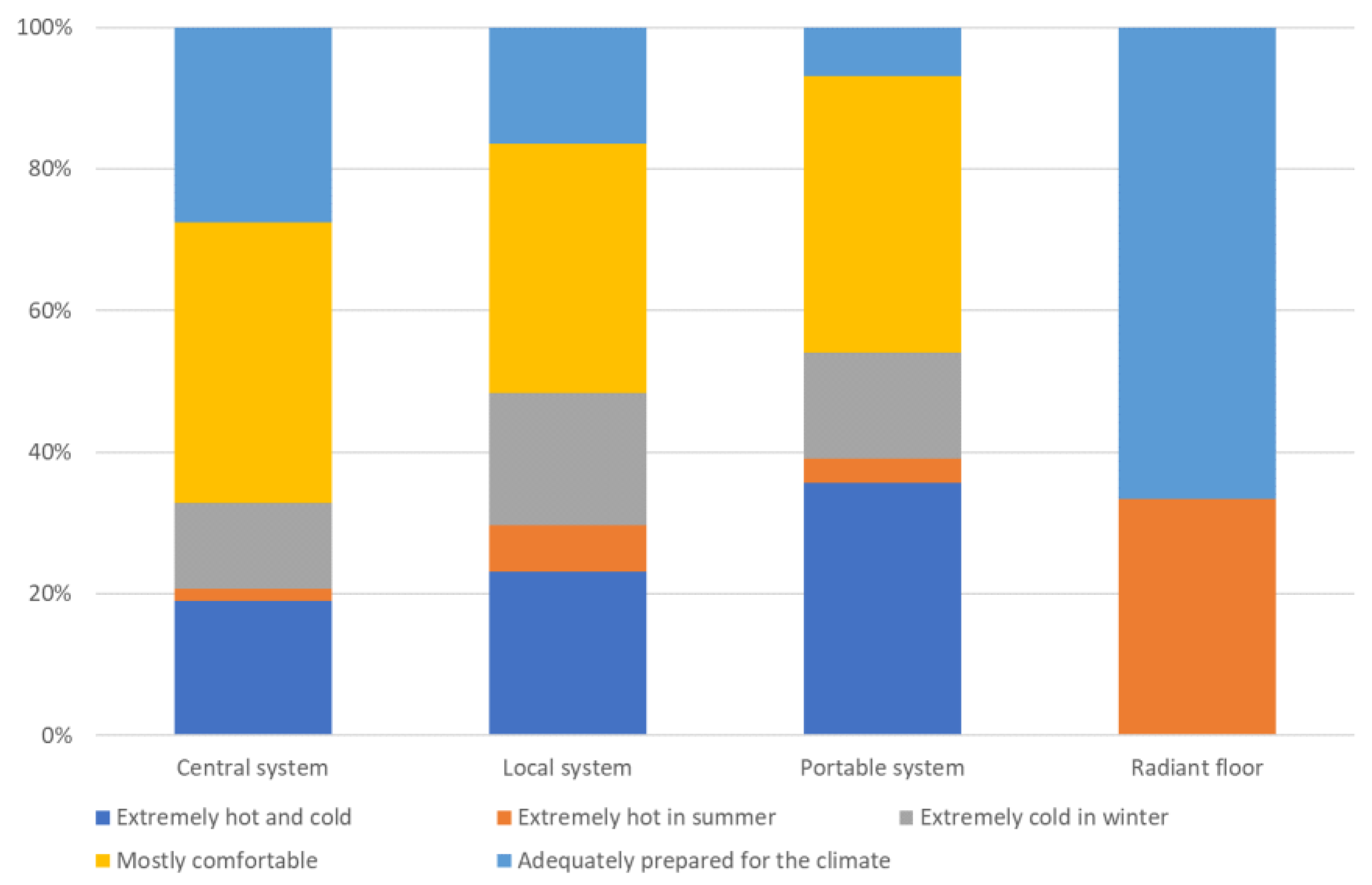

3.4. Mechanical Systems

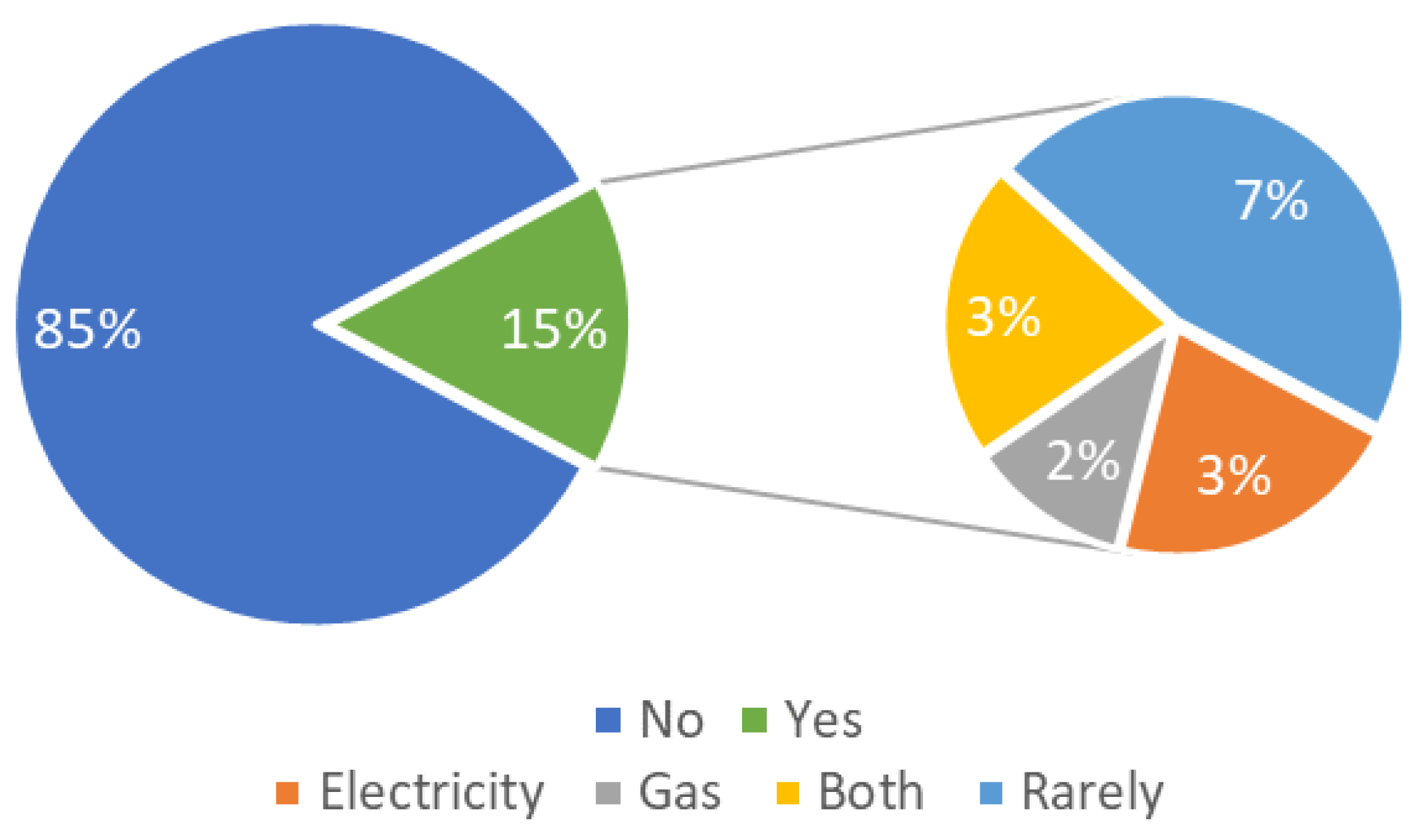

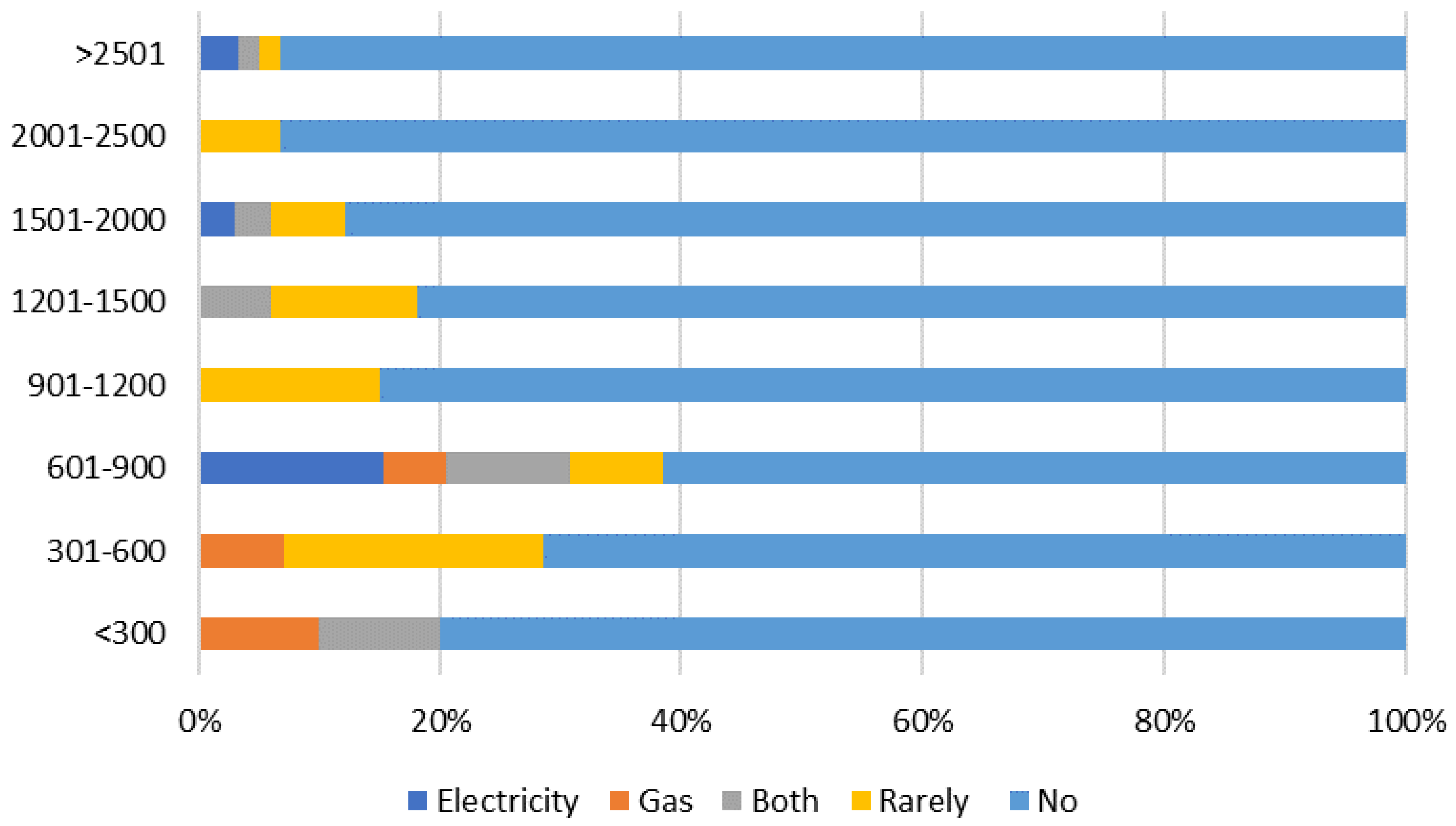

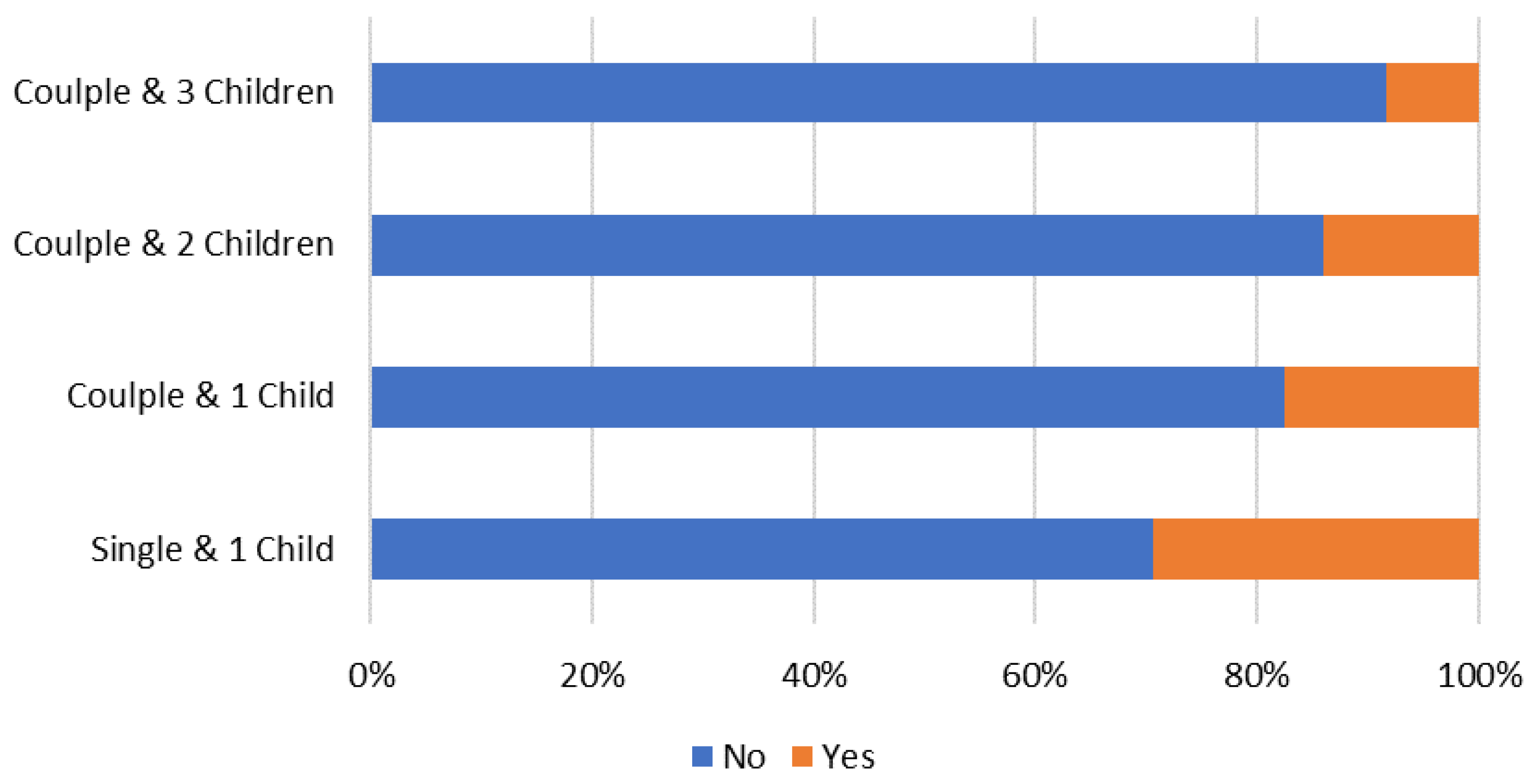

3.5. Energy Costs and Habits

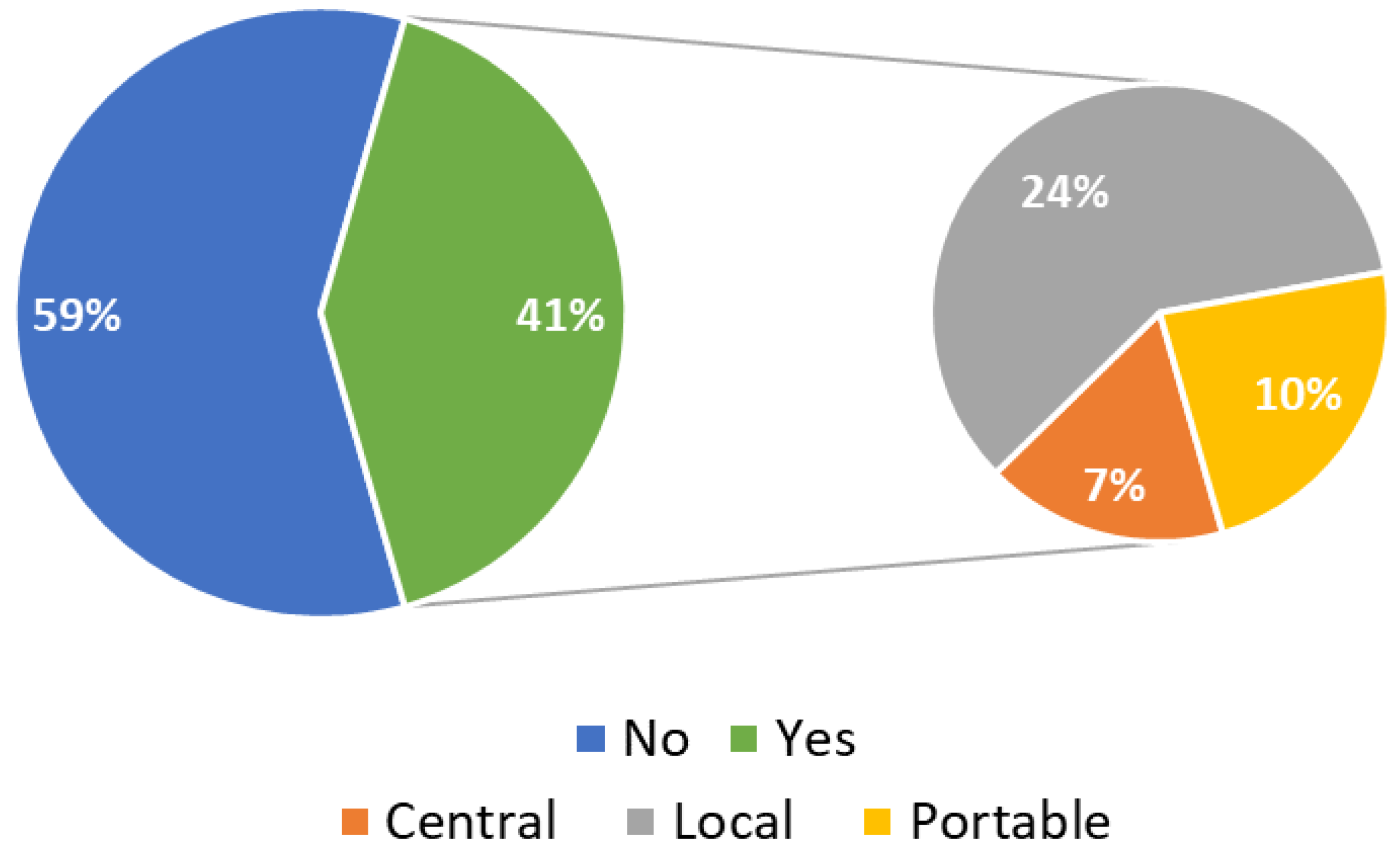

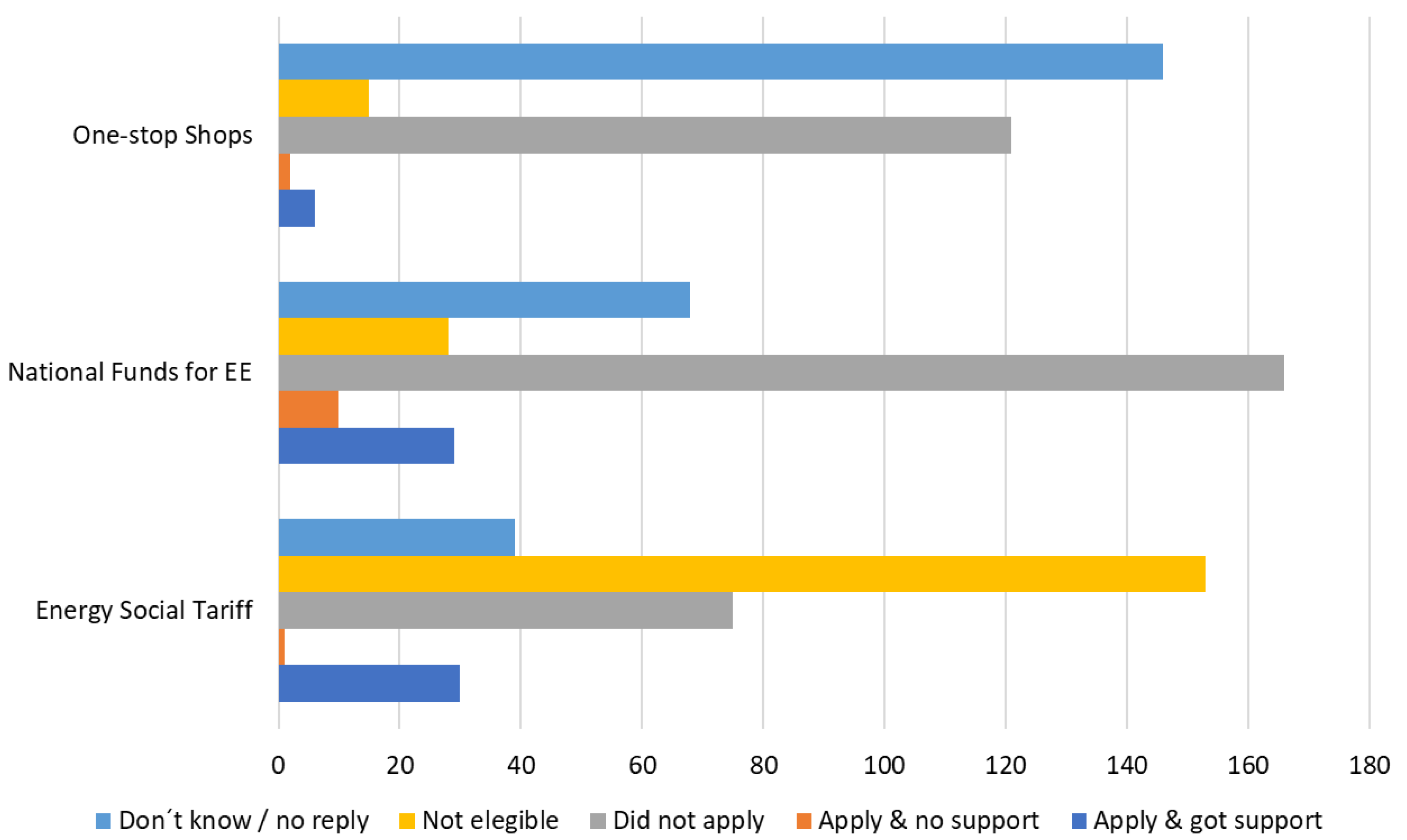

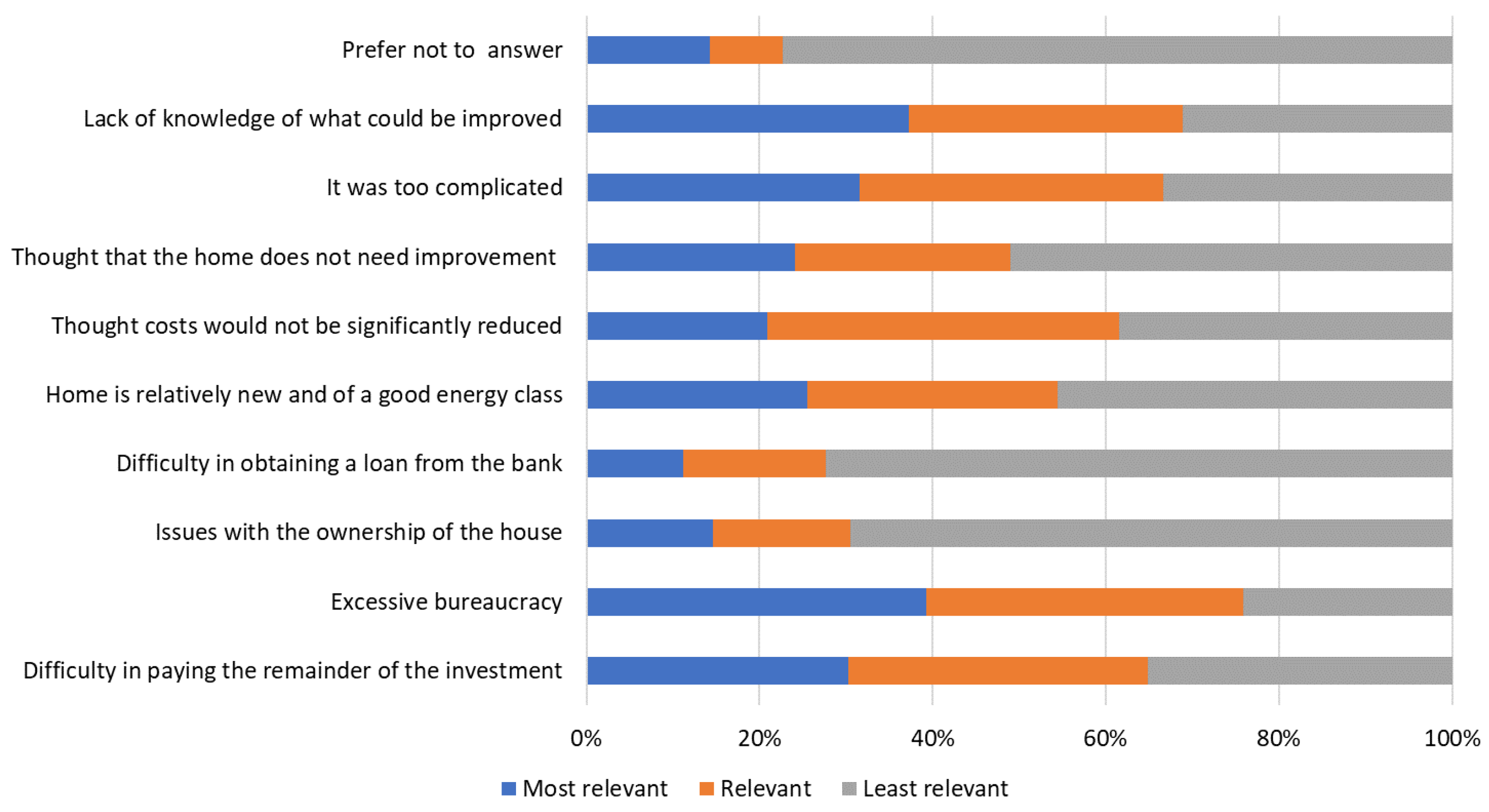

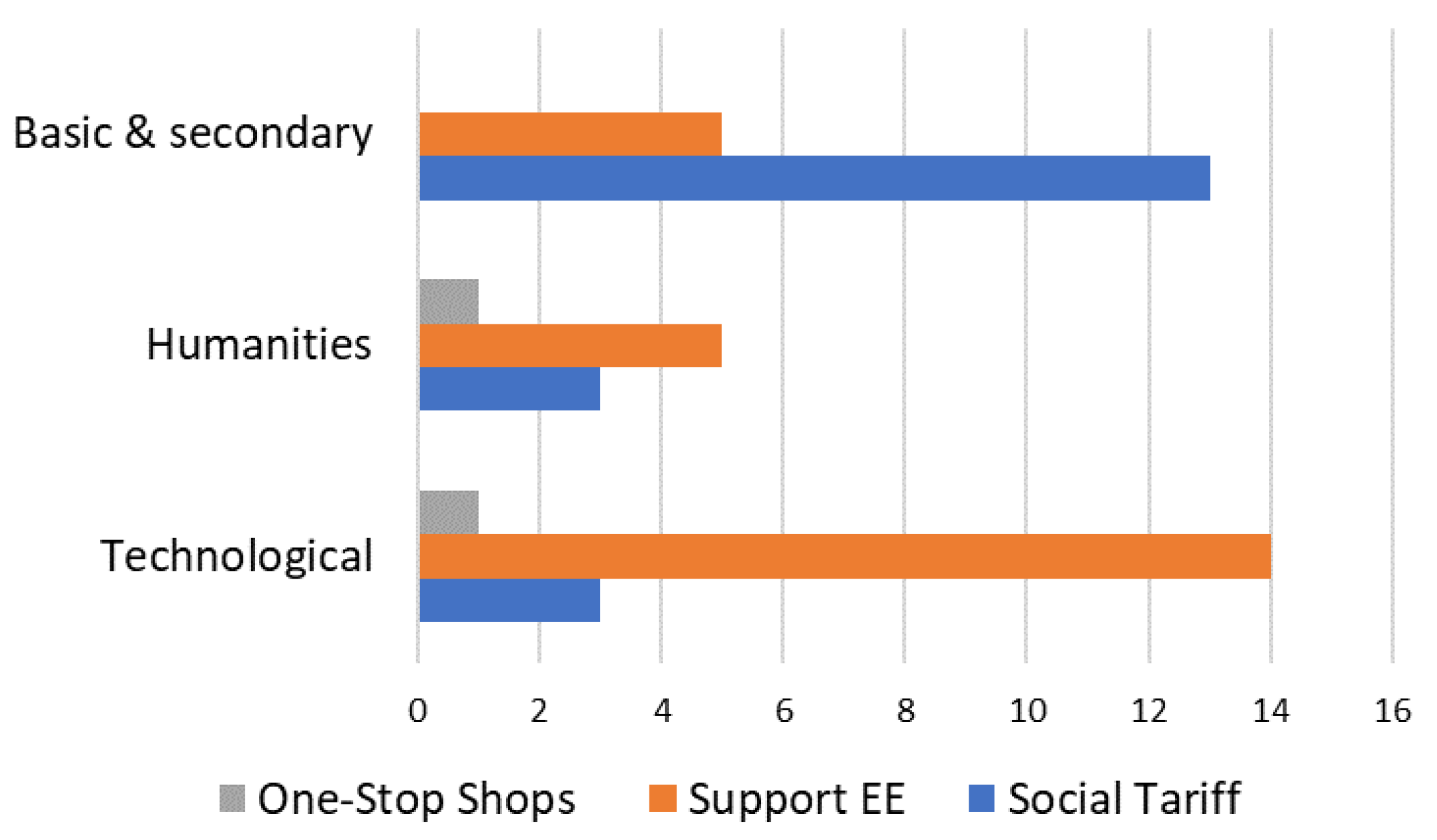

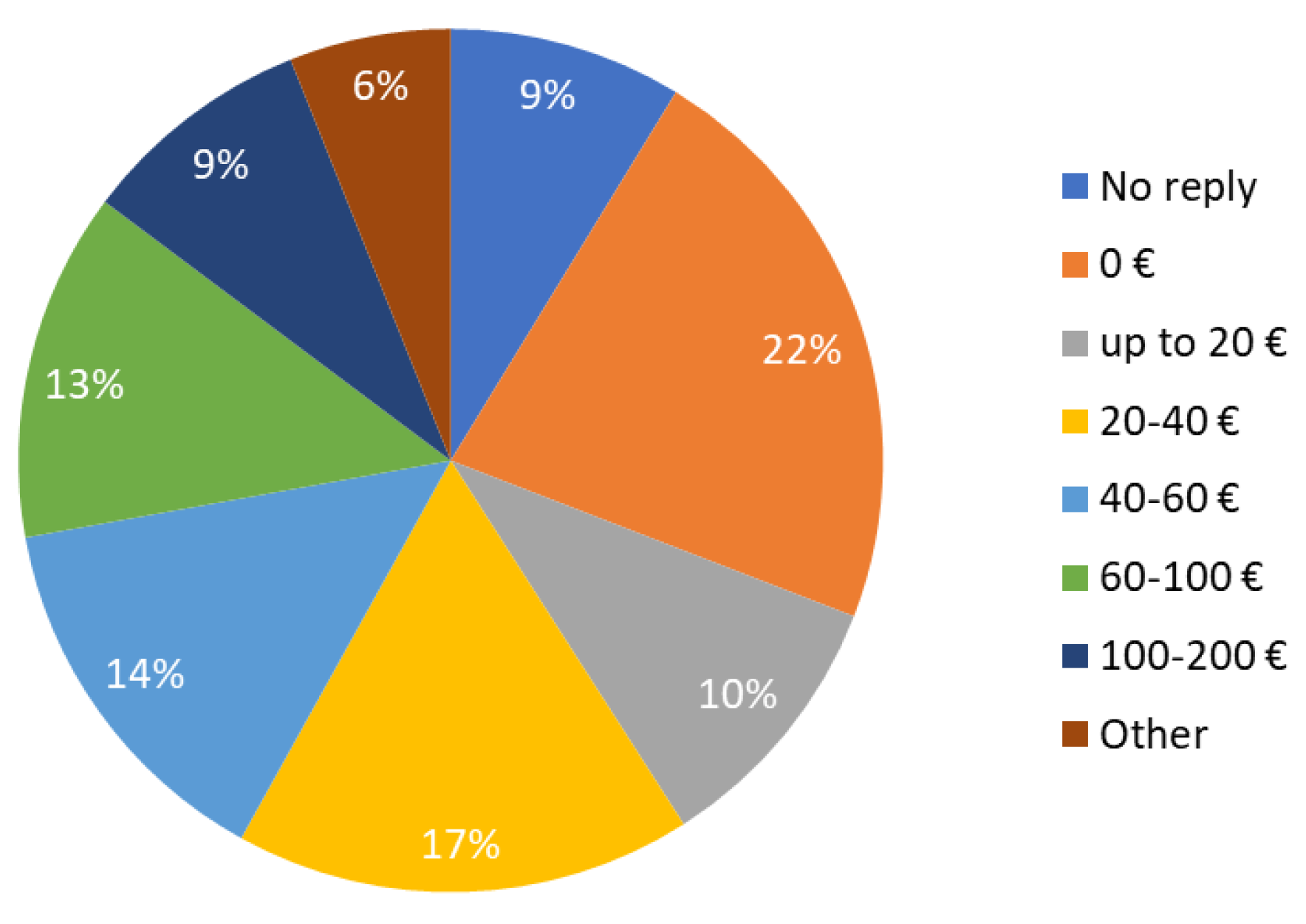

3.6. Energy Efficiency Interventions and Awareness

- Depends on the upfront costs;

- The house is rented and there is no keenness to spend money on retrofits;

- A retired person indicated that the amount received per month does not allow other expenses than the basics;

- Others indicated the amounts of EUR 500, 1000, and 5000 at once, but that it depended on the payback (5 years’ payback time was indicated by one respondent).

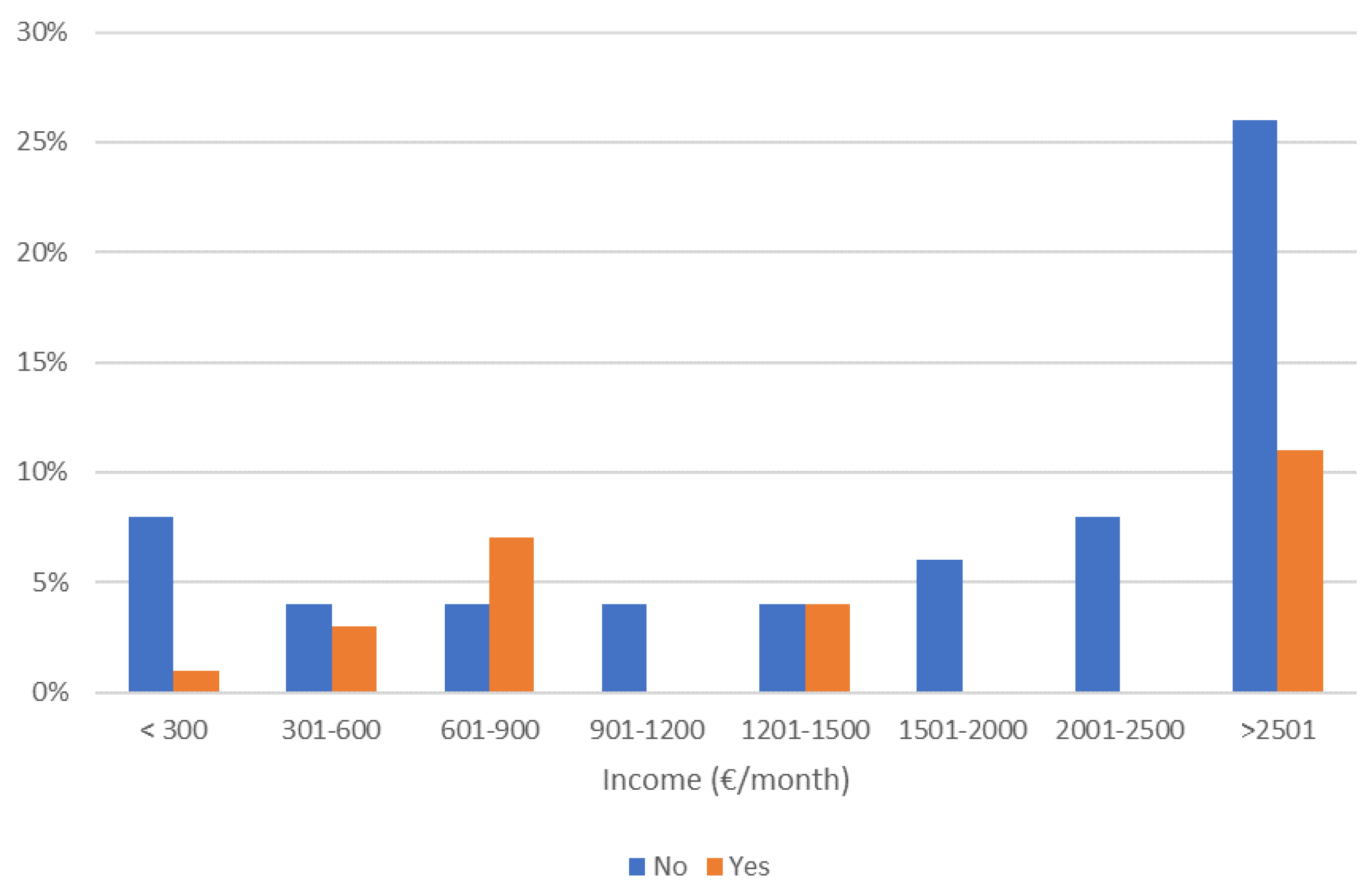

4. Diagnosis of Energy Poverty

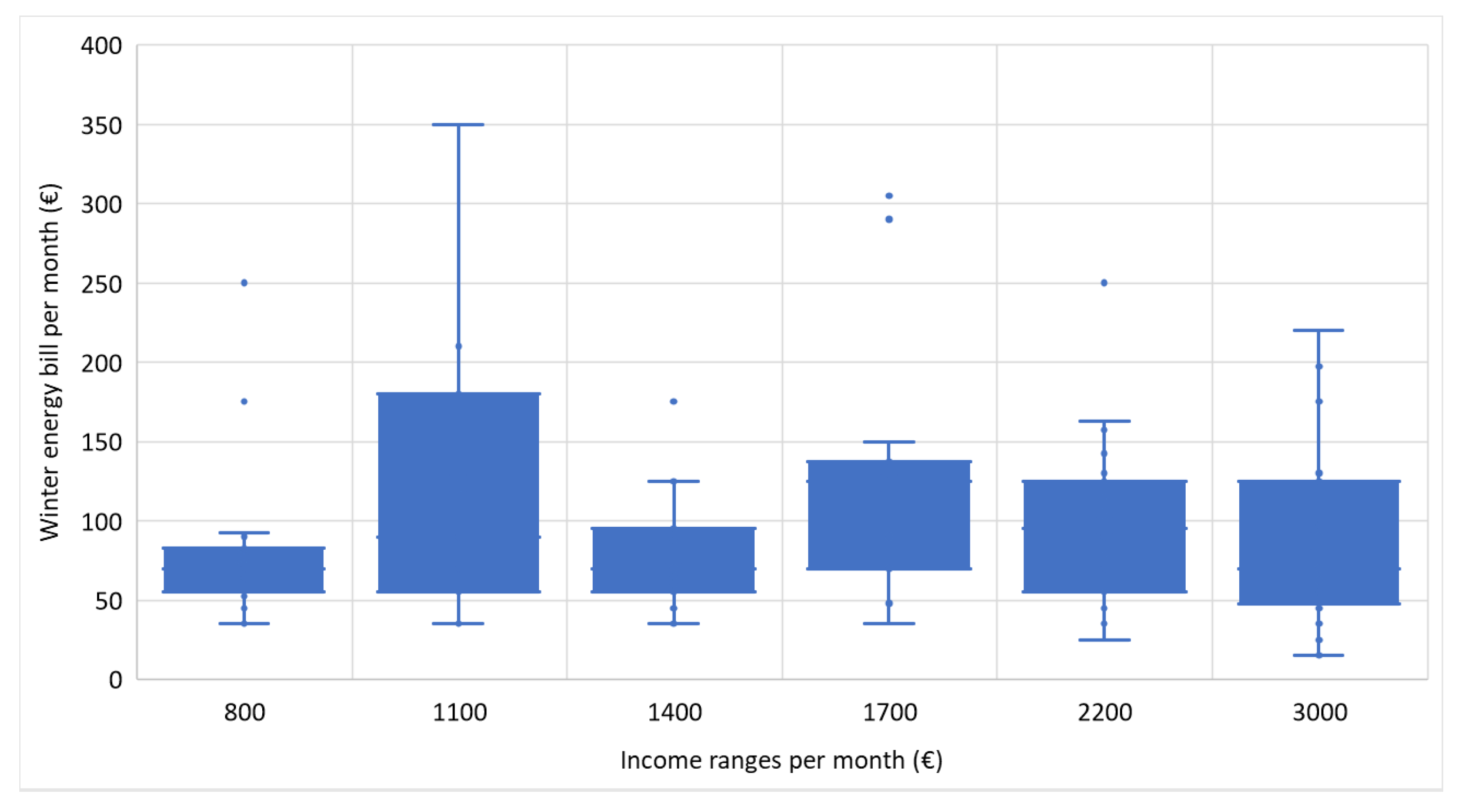

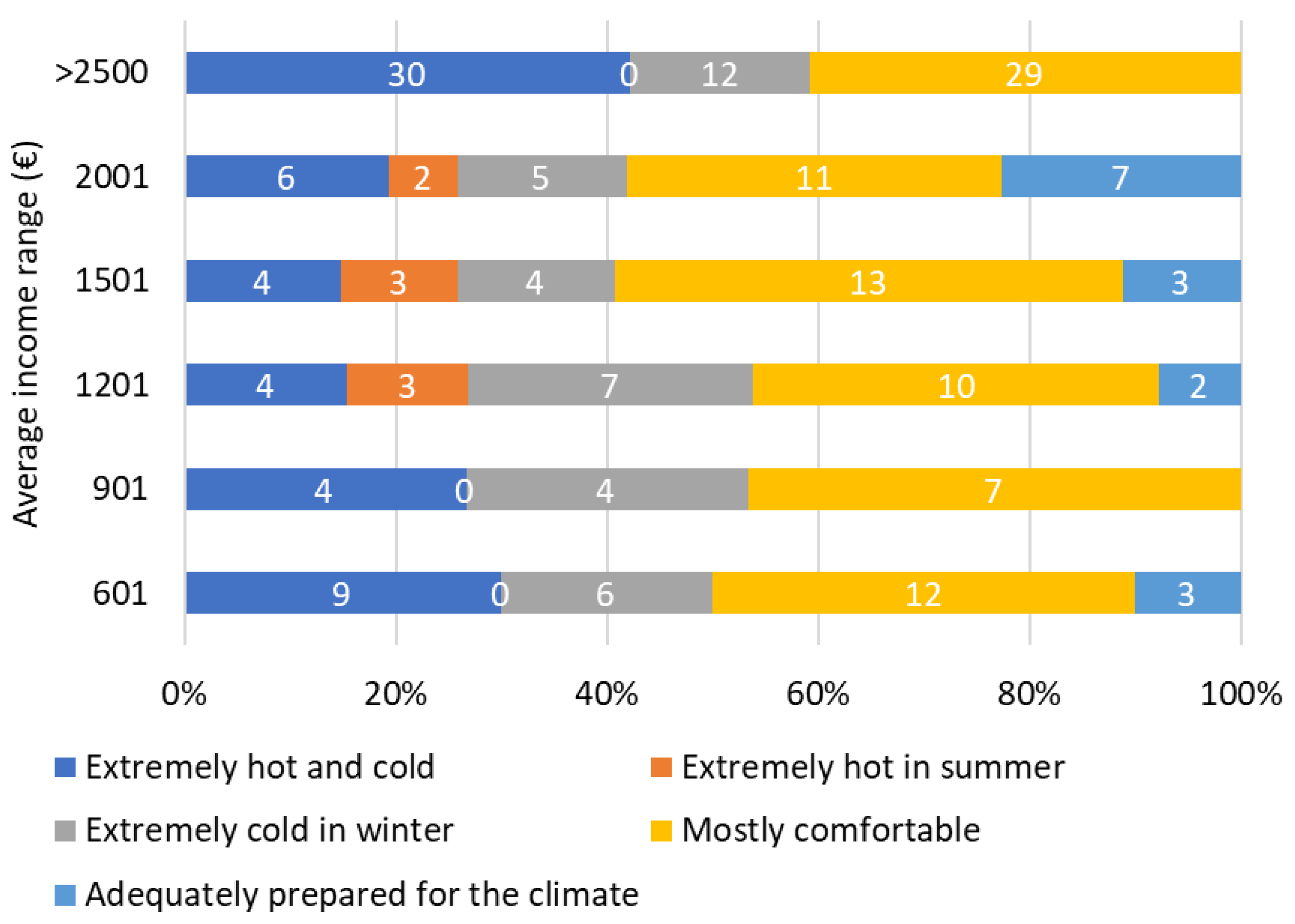

4.1. Energy Bills, Income and Comfort

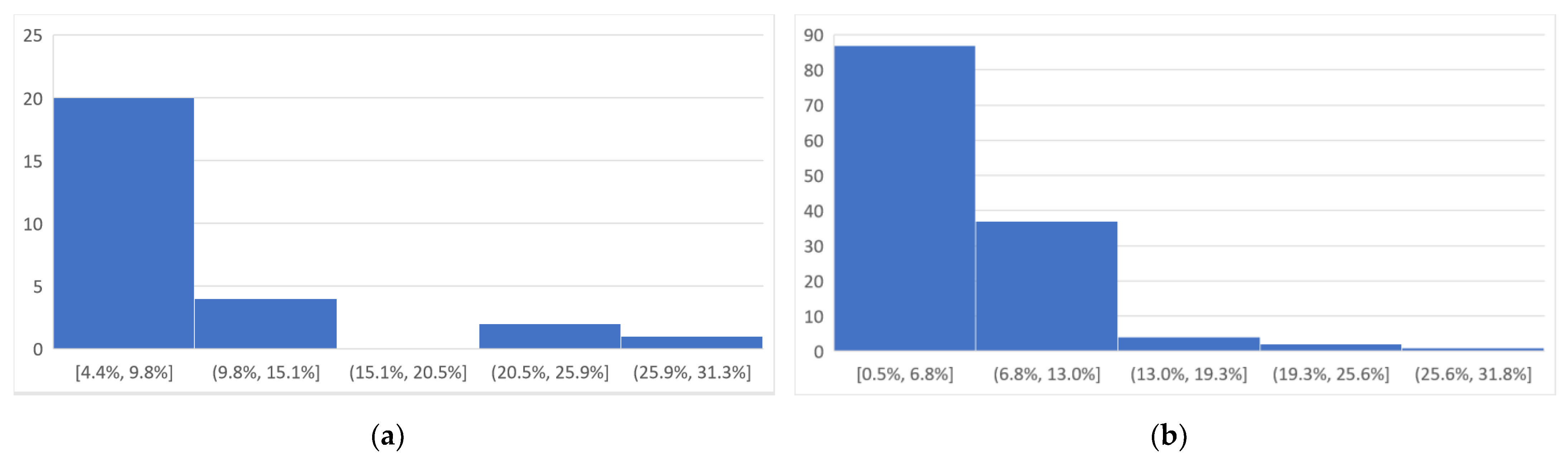

4.2. Energy Poverty Indicators

- Low efficiency—single-glass window and window condensation;

- Medium efficiency—double-glass windows and window condensation;

- High efficiency—double-glass windows, thermal cut, and no condensation in windows.

- Low income—≤1100 €/month;

- Medium income—>1100 €/month and ≤1700 €/month;

- High income—>1700 €/month.

5. Conclusions

- Analyzing existing energy rehabilitation techniques and adapting them to the region, in a process of multidisciplinary collaboration and the co-creation of innovative and effective solutions in conjunction with local players and stakeholders under a logic of non-invasive intervention and life cycle analysis, complying with the legal and normative framework defined by the regulation of the energy performance of buildings.

- Incentivizing the installation of heat pumps with a high coefficient of performance, particularly in existing buildings, to boost energy efficiency and enhance thermal comfort, as their use in new constructions is already widespread but not yet common in retrofits.

- Accelerate the implementation and promotion of passive houses and other building standards, installing solar thermal systems for heating sanitary water, and promoting services provided by renewable energy communities as the municipalities are keen on renewable energy communities and are open to innovative schemes.

- “One-stop shops” that provide information, guidance, and rehabilitation services to vulnerable households. These are emerging in the market in association with European projects, but more need to be established in association with municipalities to enroll vulnerable households in financing programs to improve energy efficiency, health, and comfort conditions in homes.

- Actions aimed at promoting awareness through less formal activities involving the population and the exchange of knowledge, training, and coaching in order to promote the development of skills and combat energy illiteracy, as these are crucial for the success of this concerted action.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat Key Figures on European Living Conditions—2023 edition; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-key-figures/w/key-figures-on-european-living-conditions-2023-edition (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Papada, L.; Katsoulakos, N.; Doulos, I.; Kaliampakos, D.; Damigos, D. Analyzing Energy Poverty with Fuzzy Cognitive Maps: A Step-Forward towards a More Holistic Approach. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2019, 14, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasiu, B.; Kontonasiou, E.; Mariottini, F. Alleviating Fuel Poverty in the EU. Investing in Home Renovation, a Sustainable and Inclusive Solution; Buildings Performance Institute Europe (BPIE): Brussels, Belgium, 2014; ISBN 978-94-91143-09-0. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2023/955 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 Establishing a Social Climate Fund and Amending Regulation (EU) 2021/1060; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Volume 130. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on Energy Efficiency and Amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (Recast) (Text with EEA Relevance); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Volume 231. [Google Scholar]

- EC Clean Energy for All Europeans Package. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-strategy/clean-energy-all-europeans-package_en (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- EC National Energy and Climate Plans. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/implementation-eu-countries/energy-and-climate-governance-and-reporting/national-energy-and-climate-plans_en (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- EPAH. EPAH Lunch Talk #3 Takeaways—2023 Roadmap for Addressing Energy Poverty. Available online: https://energy-poverty.ec.europa.eu/about-us/news/epah-lunch-talk-3-takeaways-2023-roadmap-addressing-energy-poverty (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Horta, A.; Gouveia, J.P.; Schmidt, L.; Sousa, J.C.; Palma, P.; Simões, S. Energy Poverty in Portugal: Combining Vulnerability Mapping with Household Interviews. Energy Build. 2019, 203, 109423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.; Feenstra, M.; Daskalova, V. Gender Perspective on Access to Energy in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Cheikh, N.; Ben Zaied, Y.; Nguyen, D.K. Understanding Energy Poverty Drivers in Europe. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kez, D.; Foley, A.; Lowans, C.; Del Rio, D.F. Energy Poverty Assessment: Indicators and Implications for Developing and Developed Countries. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 307, 118324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntaintasis, E.; Mirasgedis, S.; Tourkolias, C. Comparing Different Methodological Approaches for Measuring Energy Poverty: Evidence from a Survey in the Region of Attika, Greece. Energy Policy 2019, 125, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, P. Assessing Global Energy Poverty: An Integrated Approach. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashour, M.; Jaber, M.M. Revisiting Energy Poverty Measurement for the European Union. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 109, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szamrej-Baran, I. Assessing the Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Energy Poverty in EU Countries Using the Index of Energy Poverty. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 225, 4187–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Tirado Herrero, S. The Energy Divide: Integrating Energy Transitions, Regional Inequalities and Poverty Trends in the European Union. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2017, 24, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Thomson, H.; Cornelis, M. Confronting Energy Poverty in Europe: A Research and Policy Agenda. Energies 2021, 14, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, J.P.; Palma, P.; Simoes, S.G. Energy Poverty Vulnerability Index: A Multidimensional Tool to Identify Hotspots for Local Action. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H.; Bouzarovski, S.; Snell, C. Rethinking the Measurement of Energy Poverty in Europe: A Critical Analysis of Indicators and Data. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, H.; Snell, C. Quantifying the Prevalence of Fuel Poverty across the European Union. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, C.; Morris, C.; Thomson, H.; Guiney, C. Excess Winter Deaths in 30 European Countries 1980–2013: A Critical Review of Methods. J. Public Health 2016, 38, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A. Gripe Foi Suave, Mas Houve 3700 Mortes Acima Do Esperado No Último Inverno. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2018/12/14/sociedade/noticia/gripe-suave-3700-mortes-acima-esperado-ultimo-inverno-1854677 (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Simoes, S.G.; Gregório, V.; Seixas, J. Mapping Fuel Poverty in Portugal. Energy Procedia 2016, 106, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Panão, M.J.N. Lessons Learnt from Using Energy Poverty Expenditure-Based Indicators in a Mild Winter Climate. Energy Build. 2021, 242, 110936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafalda Matos, A.; Delgado, J.M.P.Q.; Guimarães, A.S. Linking Energy Poverty with Thermal Building Regulations and Energy Efficiency Policies in Portugal. Energies 2022, 15, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, P.; Gouveia, J.P.; Simoes, S.G. Mapping the Energy Performance Gap of Dwelling Stock at High-Resolution Scale: Implications for Thermal Comfort in Portuguese Households. Energy Build. 2019, 190, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, M.M.; Gouveia, J.P. A Sequential Multi-Staged Approach for Developing Digital One-Stop Shops to Support Energy Renovations of Residential Buildings. Energies 2022, 15, 5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, J.P.; Seixas, J.; Long, G. Mining Households’ Energy Data to Disclose Fuel Poverty: Lessons for Southern Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.C.; Gouveia, J.P. Students’ Perception of Energy Poverty—A Comparative Analysis between Local and Exchange University Students from Montevideo, Lisbon, and Padua. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1114540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, I.; Gouveia, J.P. Growing up in Discomfort: Exploring Energy Poverty and Thermal Comfort among Students in Portugal. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 113, 103550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca, M.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, A.; Jamasb, T. Objective vs. Subjective Fuel Poverty and Self-Assessed Health. Energy Econ. 2020, 87, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REVERTER Hub|Life Programme|REVERTER. Available online: https://reverterhub.eu/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- GDPR, eu. What Is GDPR, the EU’s New Data Protection Law? Available online: https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- LimeSurvey. LimeSurvey—Free Online Survey Tool. Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org/ (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Antepara, I.; Papada, L.; Gouveia, J.P.; Katsoulakos, N.; Kaliampakos, D. Improving Energy Poverty Measurement in Southern European Regions through Equivalization of Modeled Energy Costs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Gao, J.; Dai, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Shuai, C.; Li, W.; et al. Adding a Basis for Sustainable Poverty Monitoring: The Indicator Systems and Multi-Source Data of Multi-Dimensional Poverty Measurement. Environ. Dev. 2024, 49, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Poverty Advisory Hub. “The Inability to Keep Home Adequately Warm’’ Indicator: Is It Enough to Measure Energy Poverty?—European Commission. Available online: https://energy-poverty.ec.europa.eu/about-us/news/inability-keep-home-adequately-warm-indicator-it-enough-measure-energy-poverty (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Marktest Posse de Ar Condicionado Quase Duplica em 10 Anos. Available online: https://www.marktest.com/wap/a/n/id~29de.aspx (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Eurostat New Indicator on Annual Average Salaries in the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20221219-3 (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Lopes, L. Housing Crisis in Portugal: Inflation and Rising Interest Rates. Available online: https://www.caiadoguerreiro.com/en/the-current-housing-crisis-in-portugal-impact-of-inflation-and-rising-bank-interest-rates/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Castaño-Rosa, R.; Solís-Guzmán, J.; Rubio-Bellido, C.; Marrero, M. Towards a Multiple-Indicator Approach to Energy Poverty in the European Union: A Review. Energy Build. 2019, 193, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Arrears on Utility Bills—EU-SILC Survey. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ilc_mdes07/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Valeria, A. Energy Poverty in EU: Using Regional Climatic Conditions and Incidence of Electricity Prices to Map Vulnerability Areas across 214 NUTS2 European Regions. World Dev. Sustain. 2024, 4, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Attributes | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 97 | 32.4% |

| Male | 136 | 45.5% | |

| Prefer not to answer | 66 | 22.1% | |

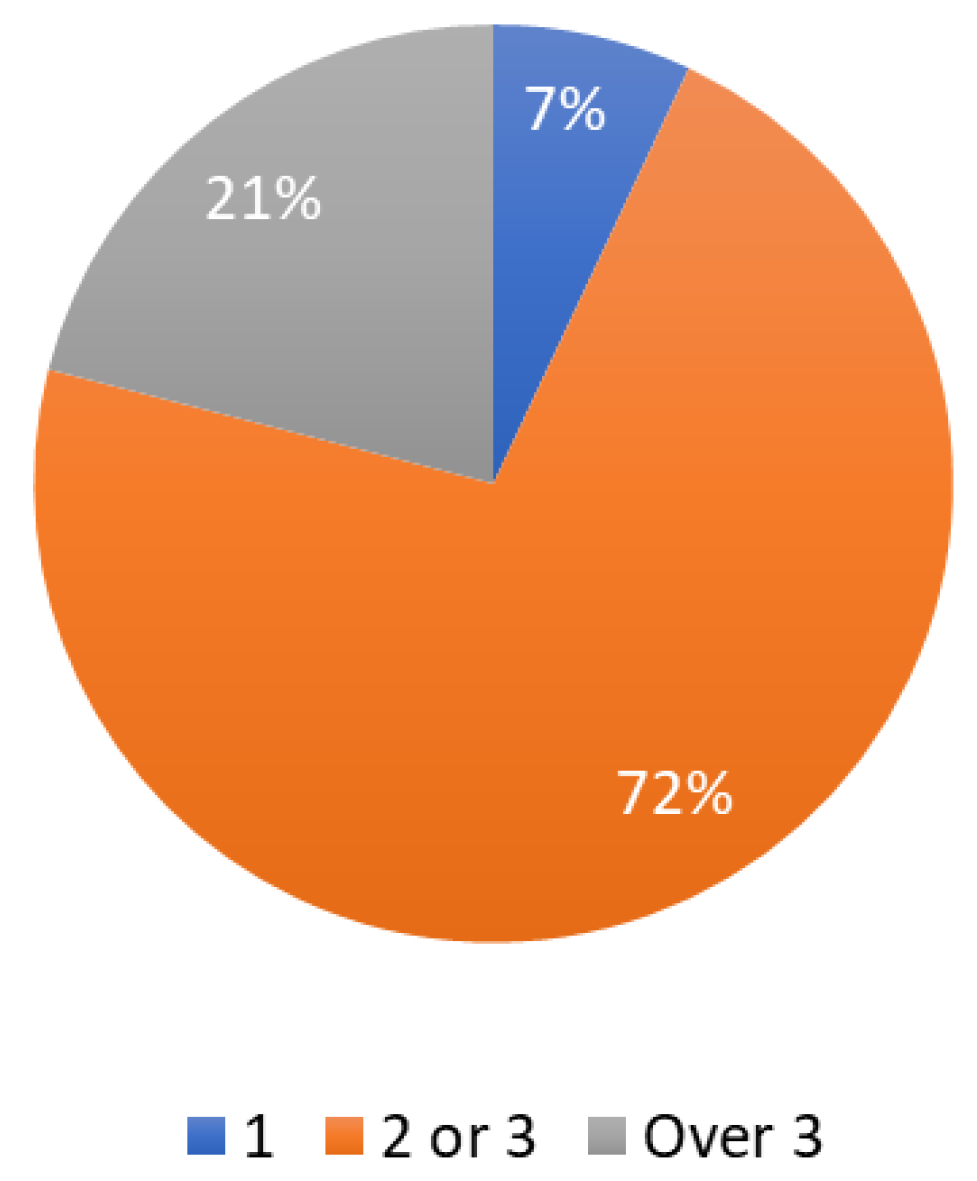

| Household members | 1 | 35 | 11.7% |

| 2 | 96 | 32.1% | |

| 3 | 85 | 28.4% | |

| 4 | 47 | 15.7% | |

| 5 | 15 | 5.0% | |

| 6 | 4 | 1.3% | |

| No response | 17 | 5.7% | |

| Household with children | 1 | 38 | 12.7% |

| 2 or more | 47 | 15.7% | |

| Household with students | 1 | 82 | 27.4% |

| 2 | 122 | 40.8% | |

| 3 | 26 | 8.7% | |

| More than 3 | 38 | 12.7% | |

| Household with pensioners | 1 | 40 | 13.4% |

| 2 | 17 | 5.7% | |

| More than 2 | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Full-time-employed household members | 1 | 87 | 29.1% |

| 2 | 139 | 46.5% | |

| 3 | 8 | 2.7% | |

| More than 3 | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Unemployed | 1 | 25 | 8.4% |

| 2 | 1 | 0.3% | |

| 3 | 0 | 0% | |

| More than 3 | 0 | 0% | |

| Education level | Graduated (technical area) | 270 | 35.9% |

| Graduated (humanities) | 121 | 16.1% | |

| Secondary school | 100 | 13.3% | |

| Secondary vocational | 23 | 3.1% | |

| Elementary school | 58 | 7.7% | |

| Primary school | 84 | 11.2% | |

| Kindergarten | 90 | 12.0% | |

| Prefer not to answer | 7 | 0.9% |

| Net Monthly Income | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 300 € | 11 | 3.7% |

| 301–600 € | 14 | 4.7% |

| 601–900 € | 41 | 13.7% |

| 901–1200 € | 22 | 7.4% |

| 1201–1500 € | 35 | 11.7% |

| 1501–2000 € | 35 | 11.7% |

| 2001–2500 € | 45 | 15.1% |

| >2500 € | 59 | 19.7% |

| Prefer not to answer | 37 | 12.4% |

| Monthly Expenditure | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| up to 500 € | 37 | 12.4% |

| 500–1000 € | 89 | 29.8% |

| 1001–2000 € | 95 | 31.8% |

| >2001 € | 47 | 15.7% |

| Prefer not to answer | 31 | 10.4% |

| Expenditure to Net Income | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 30% | 6 | 2.0% |

| 30–50% | 56 | 18.8% |

| 50–70% | 54 | 18.1% |

| 70–85% | 31 | 10.4% |

| 85–100% | 45 | 15.1% |

| Over 100% | 40 | 13.4% |

| No response | 66 | 22.1% |

| Construction Year | Max | Min | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Built before 1960 (thick walls, high inertia) or of vernacular type | 300 | 51 | 135.9 |

| Built between 1960–2010 (concrete structure and low insulation) | 600 | 30 | 135.5 |

| Built after 2010, with newer regulations | 300 | 85 | 153.3 |

| Home Energy Classe | Income Ranges | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤800 € | ≤1100 € | ≤1400 € | ≤1700 € | ≤2200 € | ≤3000 € | |

| Low | 5.0% | 4.3% | 5.7% | 2.1% | 3.6% | 2.9% |

| Medium | 5.0% | 2.9% | 1.4% | 5.0% | 3.6% | 7.1% |

| High | 8.6% | 5.0% | 10.0% | 9.3% | 9.3% | 22.9% |

| Energy Bill | Income Ranges | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤800 € | ≤1100 € | ≤1400 € | ≤1700 € | ≤2200 € | ≤3000 € | |

| 20–30 € | 2.3% | 1.4% | 1.8% | 1.8% | 0.0% | 0.5% |

| 40–50 € | 3.2% | 3.2% | 3.6% | 2.3% | 2.3% | 1.4% |

| 50–60 € | 2.7% | 1.4% | 3.2% | 2.3% | 2.7% | 3.6% |

| 60–80 € | 3.2% | 2.7% | 0.5% | 1.8% | 5.0% | 5.0% |

| 80–100 € | 1.4% | 1.8% | 2.3% | 2.7% | 3.2% | 5.0% |

| 100–150 € | 2.7% | 0.0% | 1.8% | 2.7% | 5.0% | 7.2% |

| >150 € | 0.9% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 4.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moura, P.; Fonseca, P.; Cunha, I.; Morais, N. Diagnosing Energy Poverty in Portugal through the Lens of a Social Survey. Energies 2024, 17, 4087. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17164087

Moura P, Fonseca P, Cunha I, Morais N. Diagnosing Energy Poverty in Portugal through the Lens of a Social Survey. Energies. 2024; 17(16):4087. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17164087

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoura, Pedro, Paula Fonseca, Inês Cunha, and Nuno Morais. 2024. "Diagnosing Energy Poverty in Portugal through the Lens of a Social Survey" Energies 17, no. 16: 4087. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17164087

APA StyleMoura, P., Fonseca, P., Cunha, I., & Morais, N. (2024). Diagnosing Energy Poverty in Portugal through the Lens of a Social Survey. Energies, 17(16), 4087. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17164087