Abstract

The incidence of energy poverty in the Global South is identified by the lack of basic access to modern fuels and energy carriers. Impoverished people have traditional biomass and human power as their only sources of energy. This situation of deprivation of basic resources, in which (according to estimates of international agencies) almost one third of the world’s population lives, masks other relevant characteristics of energy poverty. Current assessments of energy poverty in impoverished areas and the mitigation strategies being implemented are derived from the development agenda and, with variations in detail and scope, highlight electricity connections and access to clean cooking fuels as guarantors of progress. However, a comprehensive understanding of energy poverty requires focusing beyond basic access, building on the interactions between the supply of energy sources and carriers, the provision of energy services, and their impact on decent living conditions. To deal with the effects of these interactions on the energy poor, several studies have attempted in the last decade to construct an assessment framework centred on energy services. This work discusses the relevant dimensions in the framework (supply, services, and impact on wellbeing), reviews the multidisciplinary work available in each aspect, presents a range of proposed taxonomies, and discusses the different issues. A detailed framework is proposed for the integrated assessment of the supply of energy carriers and energy equipment, the provision of relevant energy services, and the improvements obtained in living conditions.

1. Introduction

The energy poverty literature has grown exponentially in the last decade [1,2,3] with a focus on developed countries—and Europe in particular—but also producing a branch of works that deals with the aspects of the problem in the Global South [4,5,6,7]. Some works have tried to establish a global perspective of energy deprivation [8,9], and others have focused on particular local cases [10,11], but in general, the approaches fall into two divergent types defined for developed and developing regions [12]. In developed countries, the emphasis is mostly on the affordability of domestic energy services, primarily space heating [13,14,15], while in the Global South, attention is generally centred on the lack of access to the energy supply of ‘modern’ sources of energy such as electricity, natural gas, or LPGs [16,17,18]. In both cases, the focus is on the supply of energy sources and carriers, either for its costs or its availability.

EU indicators of energy poverty [15] deal with household energy expenses (in three parallel ways: whether expenses are too small, whether they represent a large share of the family budget, or whether utility bills go unpaid) and the capability of dwellers to keep their household adequately warm. Global South indicators deal with access to electricity or to modern cooking fuels, and although large differences can be observed, for example, between simple binary indicators such as those of Sustainable Development Goal 7 [19,20,21] and the complex array of indicators developed by the World Bank [22] or the intermediate indicators of the IEA [23,24], most efforts remain centred on the supply of energy sources and carriers.

Nevertheless, beyond the availability of energy carriers, the focus is on the specific energy services that are thus obtained, and ultimately on the concrete achievement of wellbeing involved. Examples of energy sources and carriers include LPG and electricity, but also wood, while examples of services include (among others) lighting, space heating, cooking, or transportation. Achievements of wellbeing are more subtle and difficult to assess; e.g., being able to cook permits the satisfaction of the basic physiological need for food but also may help in shaping household values of respect, protection, and affection, while lighting enhances the possibilities for daily activities and can help in gaining education, providing entertainment, or facilitating social contact. But the interactions between these (or other) carriers, services, and achievements depend on a large variety of aspects that interlink in a complex way. Weather conditions (e.g., highlighting the need for space heating or cooling, or both, or neither), together with cultural patterns and/or socio-economic household characteristics (e.g., ways of cooking, needs for transportation or energy for labour at home, etc.) may influence the metabolic pattern in which a society uses energy to develop or access decent living conditions.

To have a broader view on the effect of energy services on living conditions, their interactions with general poverty indicators can be addressed. The poverty indicators used for the Global South by the World Bank, the UN, or the 2030 Agenda and those implemented in the EU such as the AROPE index (At Risk of Poverty and/or Exclusion) will be analyzed in terms of their relation to energy poverty aspects. Some indicators of general poverty can be identified as energy-linked (i.e., they have clear dependencies on the availability of one energy service or another), whereas some of them straightforwardly use energy access parameters as indicators (like the access to electricity or the ownership of a fridge). These interactions between energy aspects and the broad definitions of poverty can be used to establish the mechanisms linking energy use to wellbeing.

The complex relation between energy services and decent living conditions (or wellbeing) has been studied in the recent past by several authors to establish a general framework of energy vulnerability. Bouzarovski and Petrova [8] assessed the relevance of different energy services for domestic energy deprivation, producing a typology of energy vulnerability factors and their constituent elements. Kalt and co-workers [25] discussed the different approaches to identifying energy services and their effects on societies. Day and co-workers [9] presented an analysis of energy services in view of Sen’s capability approach. Brand-Correa and co-workers [26] identified links between energy services and wellbeing using Max Neef’s taxonomy of needs [27]. This approach is also used by García-Ochoa [28] for the definition of an energy poverty index for CEPAL (United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean). Ruiz-Rivas and co-workers [6] presented a critical review of the multidisciplinary work that leads to the construction of energy poverty alleviation strategies in the Global South, from the definition of basic energy needs and services to the indicators of assessment, the global or local action plans, or the design and development of standard or alternative technology to fight the problem.

In this work, a review of the different approaches to energy poverty assessment is performed, and a methodology is proposed to (a) establish a framework that links energy services with social benefits (individual and communal) and (b) identify indicators of performance for energy supply projects that go beyond characterizing energy access and seek to assess the concrete impacts on living conditions.

2. The Interactions between Poverty and Energy Poverty

An important part of the population in the Global South lacks access to electricity or depends on traditional biomass for cooking and heating. Current figures, provided by the IEA [29], state that 760 million people do not have access to electricity and 2.3 billion to clean cooking fuels. Building from this key feature in the development agenda, the most relevant indicators of energy poverty focus on those two figures. Therefore, the operating indicators of SDG 7 directly concerning the Global South are the proportion of the population with access to electricity (with a target of 98% of the global population in 2030) and the proportion of the population with a primary reliance on clean fuels and technology (with a 2030 target of 85%). The world population is projected to reach 8.5 billion in 2030 (UN data), so target figures of SDG7 are to reduce the population without access to electricity to 170 million and those without access to clean cooking fuels to 1.3 billion by 2030.

Even though it is evident that not having access to electricity and/or relying on “dirty” fuels (wood, dung, waste, etc.) are clear indicators of poverty, the approach has often been considered too narrow. The Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) added considerations of indoor pollution and appliance ownership in its Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index [30], while the World Bank defined its “beyond connections” strategy [22] in opposition (and as a next step) to the binary indicators of the UN. The World Bank (WB) strategy enhanced this view by identifying a multi-tier framework that considered various levels of access to energy sources and carriers and included aspects like quality, reliability, legality, or security (risks, pollution, etc.) of the supply. It also distinguished between fuels for cooking or heating (this last one often being neglected for Global South indicators although being the focus of Global North indicators). These efforts have broadened the view, but still, there are plenty of issues left for characterizing energy vulnerability “beyond carrier supply”, both in developed countries and in the Global South.

Before engaging in such views, it is relevant to discuss the relationship between poverty and energy poverty. How does one affect the other, and vice versa? This is the fundamental question of how energy use interacts with a society and its progress. To understand this relation, the methods of characterizing poverty, both in developed countries and in the Global South, must be assessed. Income indicators are the norm for poverty assessment with a variety of approaches based on averages, fixed or variable limits, inequalities, etc. Criticism of income approaches generally states that they provide an indirect view of poverty, as income identifies possibilities rather than achievements in poverty issues. A completely different approach was proposed and tried in Latin America in the 1980s, with the Unsatisfied Basic Needs approach (UBN). It was a direct approach identifying six possible household deficiencies classified in four dimensions (access to housing, health and education services, and economic capacity). One deficiency identifies a household as poor. A similar approach has been adopted in the last decade by the UN with the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), which identifies 10 possible household deficiencies organized in three dimensions (access to health and education services and living conditions). Here, the three dimensions are equally valued, and a sum of deficiencies larger than one-third (all adding to one) identifies a household as poor (while a sum larger than 0.5 identifies a severely poor household). The EU also uses a similar criterion to evaluate severe material deprivation, together with income, with the At Risk of Poverty and/or Exclusion (AROPE) index. Here, a household is under severe material deprivation when it cannot afford at least four of a list of nine basic items (including eating meat or fish twice a week, having a car, or being able to take a one-week vacation per year).

Focusing on these direct approaches to characterize poverty, Table 1 shows the diverse criteria used by the different approaches. Some criteria are plain energy yardsticks (from energy carrier access to thermal appliance ownership), and some show a direct interaction with energy criteria (an energy supply is customary to use a car or a TV set), while others show a rather indirect relation or no link at all (although being aware that energy plays a leading role in modern societies and that there are always indirect relationships). The last column in the table suggests these relations.

Table 1.

Material deprivation criteria used for assessment of poverty and its relationship with energy issues.

A quick glimpse at Table 1 suggests that an evaluation of energy poverty might look beyond access to energy carriers, and thus establish the way in which availability of energy and its uses change the living conditions of vulnerable populations.

With these approaches to poverty in view, a general framework for the assessment of energy poverty will now be presented. The purpose is not (or not only) for completeness. The framework should serve to establish associations between a lack of energy carriers and services and household deficiencies, and subsequently identify the impact of energy poverty alleviation strategies on the wider effort to fight poverty.

In search of an all-inclusive model, first, a revision of previous attempts in the literature is performed, and the different dimensions are discussed. Then, an analysis of works devoted to each dimension is carried out (considering the available space), and a comparison and discussion of the principal methodologies and approaches within each dimension is produced. This will modulate the landscape from particularly technical contributions focused on the energy chain and energy supply to more formal work on the concept and variety of energy services, and finally towards conceptual proposals of basic needs and wellbeing that, in most cases, are not particularly focused on energy. From the revision of proposals and taxonomies, some general agreements will be identified, discussing variants and differences, taking into consideration the different points of view identified by the various authors in their works.

3. Framework to Assess Energy Poverty and Actions of Energy Poverty Alleviation

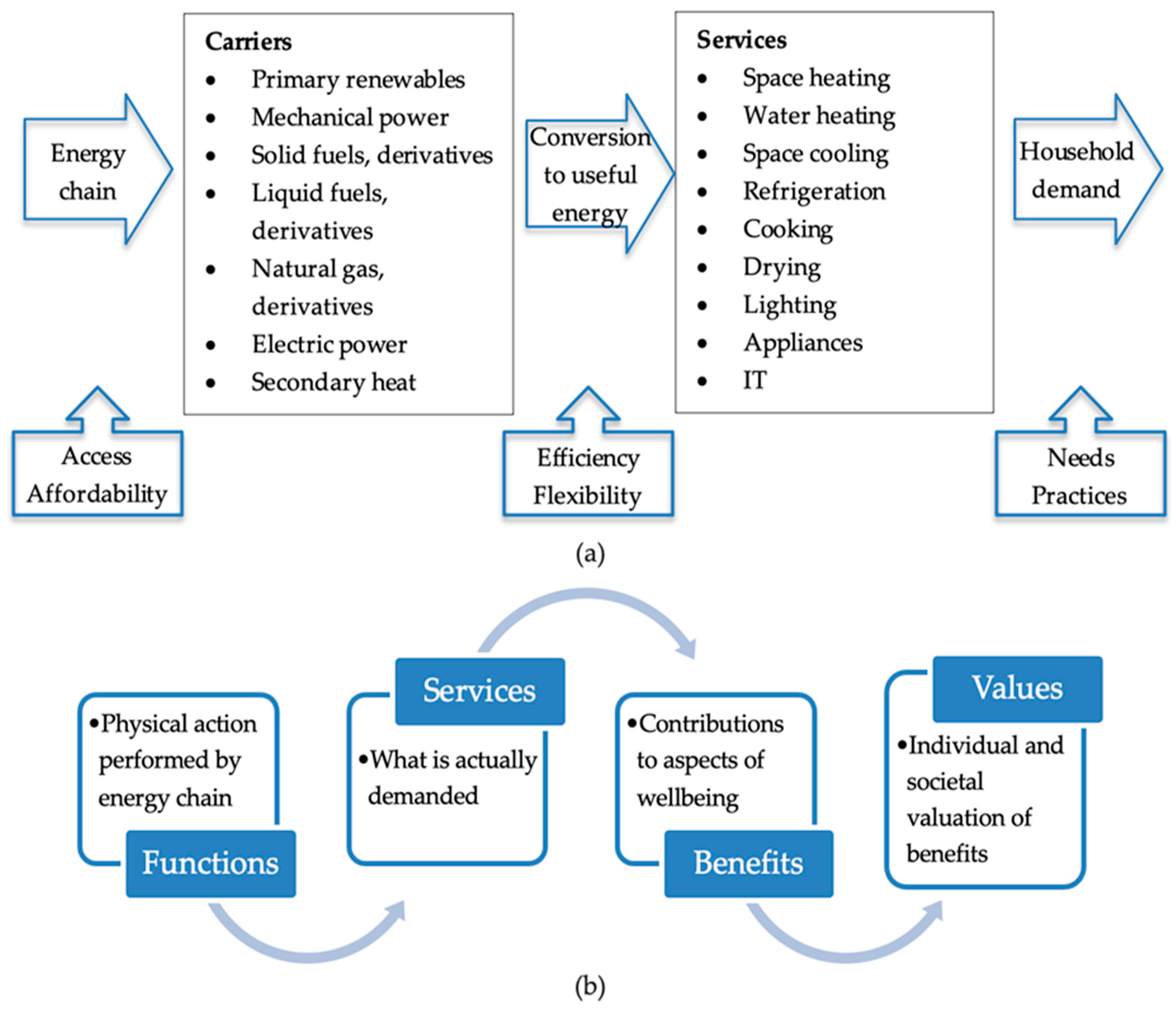

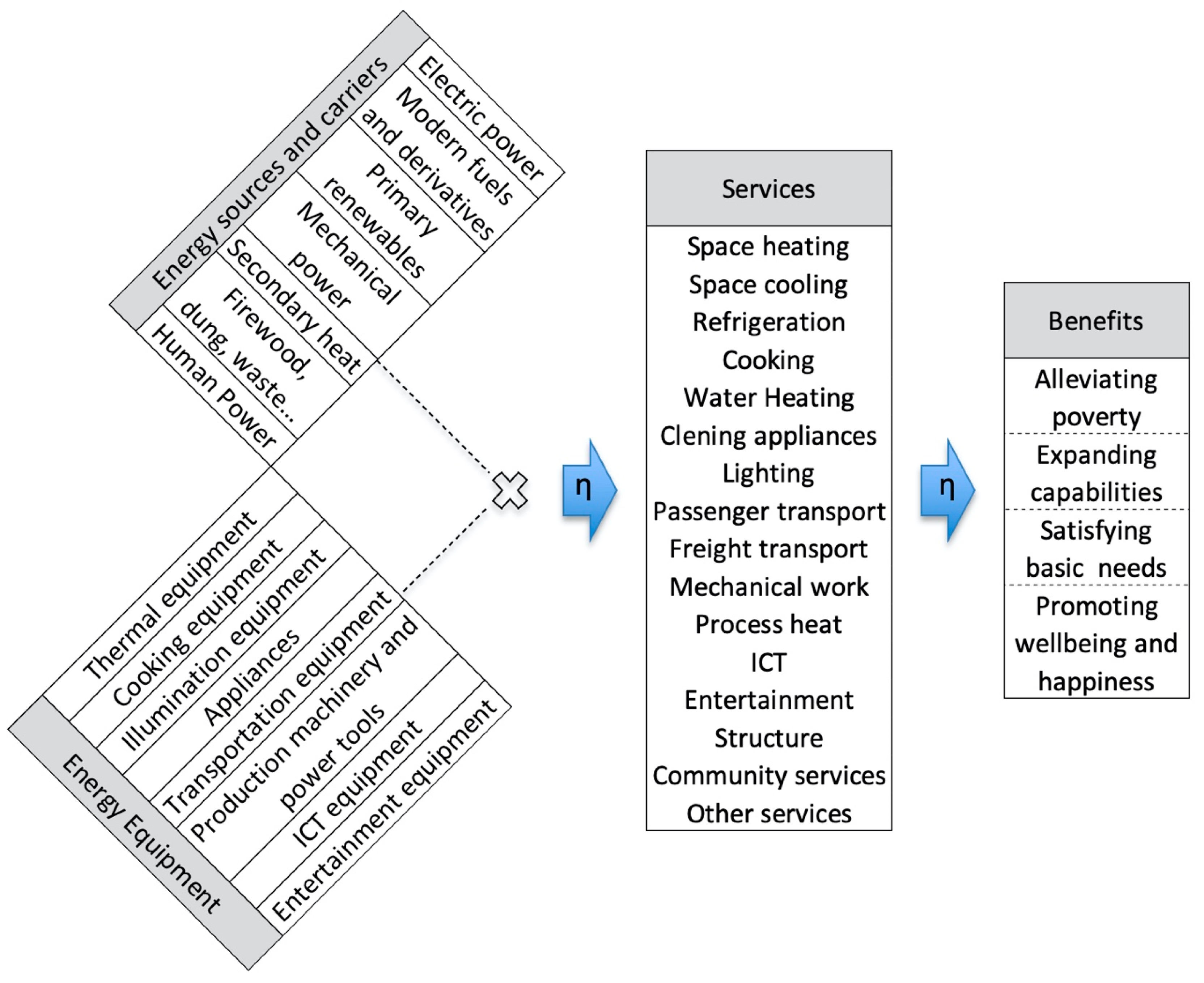

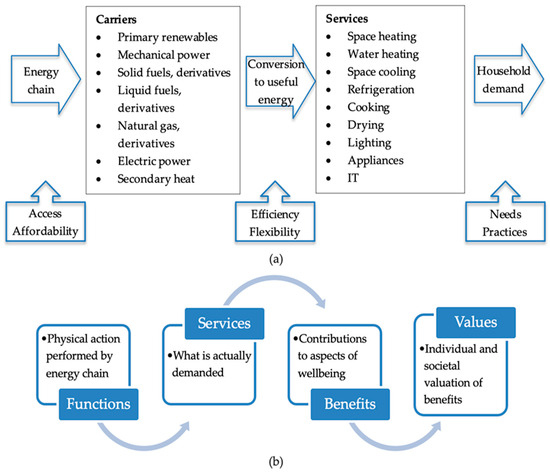

Several authors have attempted to build a general framework of the energy–society metabolic nexus, linking energy services with energy-associated wellbeing (or in opposition, the lack of it: energy poverty). The proposals of Bouzarovski and Petrova [8] and Kalt and co-workers [25] are depicted in Figure 1. The Kalt cascade model is, in turn, adapted and expanded from a proposal by Haines-Young and Potschin [31].

Figure 1.

Dimensions influencing energy services and domestic energy deprivation, adapted from [8] (a) and [25] (b).

Bouzarovski and Petrova [8] focus on the link between carriers (obtained through the energy chain) and energy services (considered the actual benefit of energy use) and provide a classification of both carriers and services. They identify two relevant vulnerability factors on the demand side: possible mismatches between requirements and available services (referenced as a needs factor) and social practises for energy use. Kalt and co-workers [25] consider a benefit dimension beyond services, which conforms the objective or reason for the process. They expand it in two parts: contributions to wellbeing and the valuation of such contributions. It is also interesting to note that access to energy equipment, although a factual necessity in the transitions between carriers from the energy chain and services, is not considered on the same level as carriers and services in both cases.

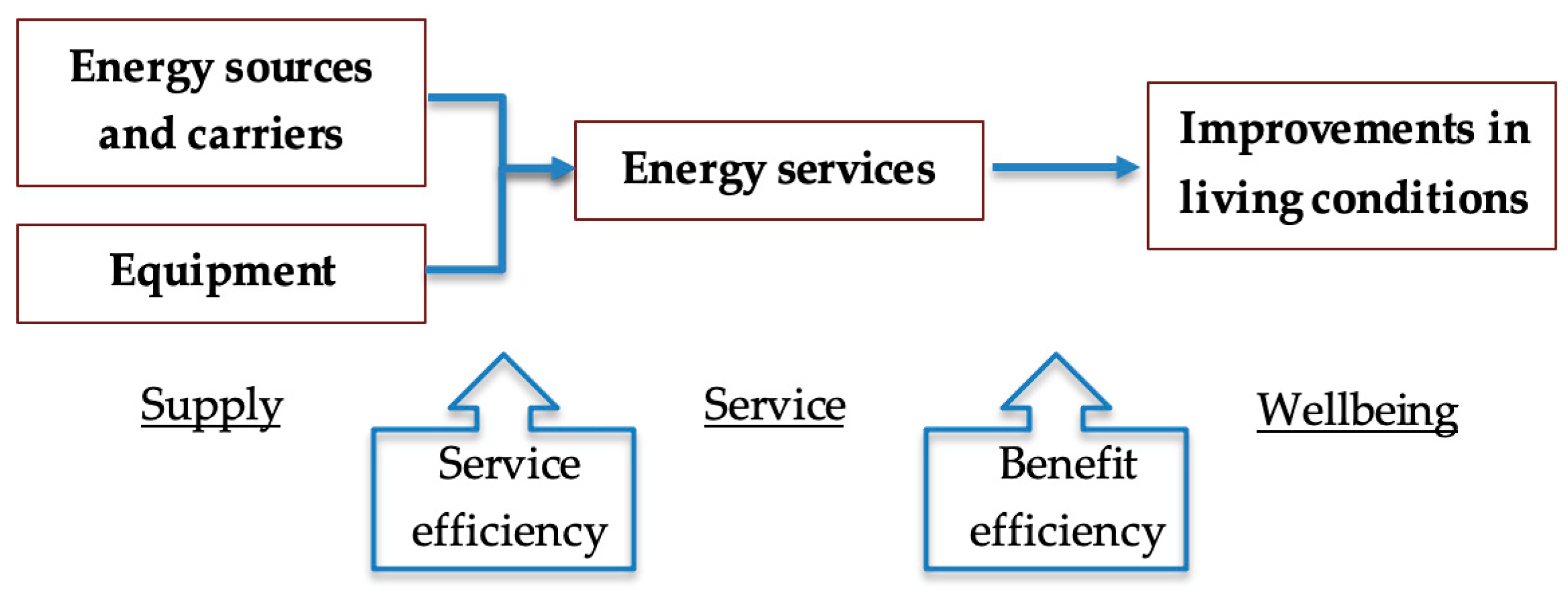

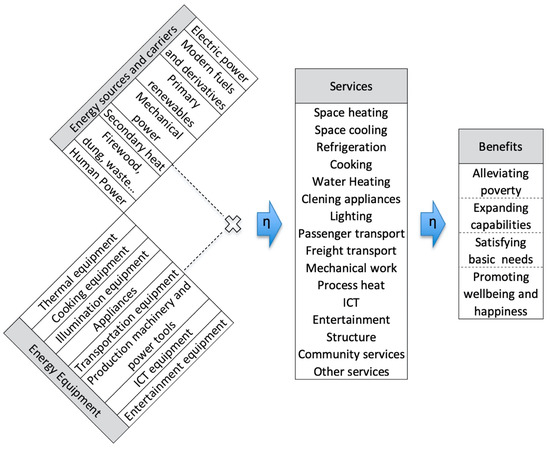

In view of these and other related proposals that will later be discussed in detail (e.g., [9,28]), a general framework to assess energy poverty is depicted in Figure 2. The main difference here is the inclusion of energy equipment as a fundamental dimension, together with a certain rearrangement and renaming of aspects. The arrangement is organized in three dimensions: supply, service, and wellbeing:

Figure 2.

Outline of a general framework to assess energy poverty.

- The supply dimension includes sources and carriers (the specific source or carrier to which access is granted and its access parameters: maximum energy, maximum power, hourly availability, quality, costs, etc.) and the supply of energy equipment (availability, output, quality, performance and efficiency, costs, etc.). As stated above, most of the energy poverty indicators available are focused on energy carrier supply, although varying a lot in the procedure and detail.

- The service dimension identifies the energy services provided by such a supply. ‘Energy services’ is, quite surprisingly, a loosely defined term in the bibliography [32], and taxonomies vary. Also, environmental characteristics may affect such taxonomies, minimizing or even eliminating some services and highlighting others (space heating and space cooling are evident examples).

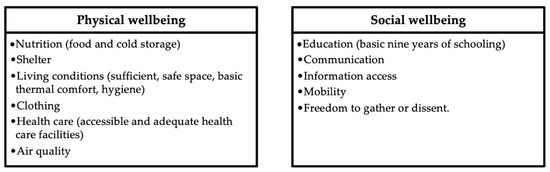

- The wellbeing dimension focuses on the identification of benefits or improvements in living conditions obtained from such services. There are several approaches to understanding such improvements. One possibility is the assessment of a change in the poverty indicators presented in the previous section. Conceptual approaches for the identification of human development go from Sen and Nussbaum’s capability theory to the variety of wellbeing approaches, or the basic human needs approach.

Figure 2 provides a framework to analyze the different approaches proposed to characterize energy poverty. Each approach generally focuses on a certain dimension (supply, service, or wellbeing). Most emphasize the supply of carriers, while few analyze services or effects on wellbeing. This general framework permits the identification of connections between different approaches and problems encountered in the quest for providing a broader view. In this sense, the analysis can be two-fold, mixing a direct approach, to identify indicators for assessing energy poverty through shortfalls in living conditions, and indirect approaches, focusing on services or carriers as necessary prerequisites for the satisfaction of needs. Indirect approaches are subjected to a certain efficiency based on the fulfilment of the inherent assumptions. An analysis of available services is subjected to a certain “benefit” efficiency established a priori: having a certain service (e.g., lighting) is considered as an indicator of a certain improvement in living conditions, but the efficiency of the transition can vary (e.g., the number of people using it and the variety of purposes, including leisure, education, or production). Analysis of the availability of energy sources, which is the most common currently, is indirect in two ways as it is based on the fulfilment of two necessary implications: having a connection or even an appropriate supply of an energy carrier is not a straightforward guarantee of having the proper energy services (e.g., depending on time availability or intensity for moving around the house, for reading, etc.), which in turn is connected to benefits to living conditions in an indirect way, as stated previously. In short, while a general aprioristic thought can consider that having an appropriate supply will produce adequate energy services and in turn will provide benefits to living conditions, such reasoning involves a general hypothesis and is subjected to certain restrictions (e.g., the availability and affordability of appliances, appropriation by the community, interaction between what is offered and what is considered a need by the community, etc.) and thus to the effect of different efficiencies, as suggested in Figure 2.

In the following subsections, a discussion of the different approaches for each dimension found in the literature is provided. Then, the efficiencies of the transformations (from carriers and equipment to services and benefits) will be analyzed.

3.1. Access to Energy Sources and Carriers

The main approach to energy vulnerability in the Global South is to prioritize access to modern energy carriers. Both the UN and the World Bank focus their strategies on such accesses, although the scope and concreteness vary enormously between proposals. As mentioned above, the operating indicators of SDG 7 identify targets concerning the proportion of the population with access to electricity and with a primary reliance on clean fuels and technology. Dependence on non-commercial forms of energy such as human power [33] and/or traditional biomass (wood, dung, etc.) is associated with the conventional view of energy poverty. The transition scenarios identify energy access with electricity connections and access to clean fuels for cooking (natural gas, LPG, etc.). Some indices also consider appropriatethe introduction and use of improved cookstoves. Improved cookstoves still rely on “dirty” fuels, but they have a far better efficiency than traditional cookstoves, and they provide a certain level of control over indoor air pollution. It is seldom mentioned that reliance on traditional biomass is often a question of affordability and not a lack of supply. Tang and Liao [34] observed that over 75% of rural households in China use biomass for cooking because they are constrained by the price of modern energy services and not by an insufficient supply of them.

The Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, linked with the UN, presented the Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI, [35]) in 2012. It is a composite index allegedly “designed to shed light on energy poverty by assessing the services that modern energy provides”. It includes information on five dimensions (cooking, lighting, services via household appliances, entertainment/education, and communication), each defined by their corresponding variables and weighted indicators. The lighting dimension (weight 0.2) is fulfilled by the electricity access variable; cooking (0.4) has two variables: the availability of a modern cooking fuel (0.2) and indoor pollution (0.2). The other three dimensions are equally weighted (0.13 each) and are fulfilled by the ownership of a fridge, a radio or TV, and a phone (either mobile or landline), respectively. The sum of the weighted indicators for a household provides a number between 0 and 1 (a value different from 0 identifies a lack) and the household is energy poor if the value is larger than 0.3. The MEPI of a community is then calculated as the proportion of the population that is energy-poor multiplied by the average of the sum of indicators of those that are energy-poor. The MEPI has been widely used in recent years [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] as it provides a simple approach that gives substantial information. Still, the MEPI relies mainly on electricity and clean fuels (0.6 out of 1), and the other services are established for a minimum need (fridge, radio, and phone, together 0.4 out of 1). The threshold value implies that one household is considered energy-poor if it does not use clean fuels, if it has no electricity (so it will also be deprived of the appliances), or, having both electricity and clean cooking fuels, if it is deprived of a fridge, radio, and phone. This third case, and the assessment of the extension and intensity of deprivations, is the main difference of the SDG indicators. Cedano and co-workers [43] later proposed a modification of the MEPI that includes an extra dimension of thermal comfort. For other relevant proposals of indicators, see references [44,45,46,47,48].

In 2010 and 2012, Practical Action, an NGO connected with the Appropriate Technology movement, presented a different approach with two indices: the Energy Supply Index and the Total Energy Access Index [49]. The TEA is an energy services index that will be addressed later in this section. The ESI is a multi-level index based on three dimensions: cooking fuels, electricity, and mechanical power. This last inclusion that establishes a basic need for mechanical work for household tasks is a clear difference from previous indices. A major change is also its non-binary condition. Each dimension is identified by six levels of access (e.g., from only accessing third-party battery charging to using a reliable AC connection available for all uses, with intermediate steps of access defined by the possession of a stand-alone electrical appliance, of limited power access for multiple home applications, or of an intermittent AC connection). This index has not been widely used, but it is a precursor of the multi-tier index promoted later by the World Bank.

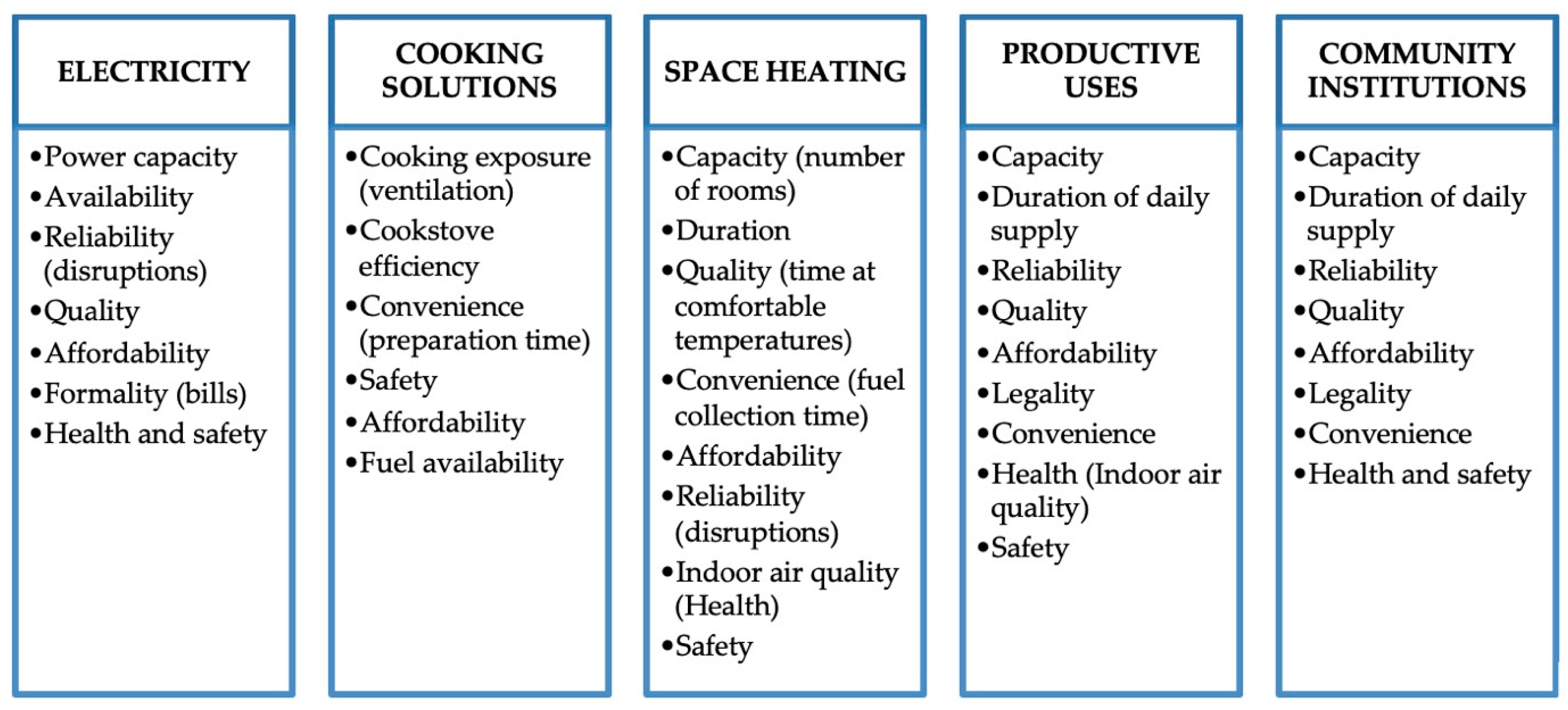

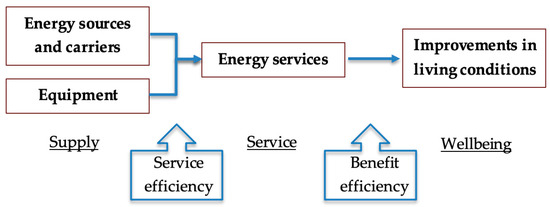

In 2015, the World Bank presented its “beyond connections” strategy [22] as a step away from the binary indicators of the UN. It identifies a multi-tier framework that considered various levels of access to different services. The World Bank approach is the broader one to this date, but for this same reason has been seldom used, except in projects specifically financed by the WB. Being such an ambitious framework, it has followed some changes in every implementation [50,51], but the general scope remains and is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Dimensions of the multi-tier framework and their attributes. Adapted from [22].

The multi-tier framework is the ultimate effort to be comprehensive following the approach that focuses on access to energy carriers. It thus transcends the narrow borders of the approach by introducing some equipment characteristics (e.g., cookstove efficiency) and identifying some relevant energy services as main dimensions of its indicators. When only electricity and cooking solutions are implemented, it is merely an expansion of the simple UN binary indicators following the multi-level approach of the ESI. Of course, its main advantage in any case is its non-binary nature, which serves to identify a wide range of actions for the progress towards energy wellbeing. This aspect is of paramount importance for development actions, as the narrow approach of the binary SDG indicators only expose changes for leaving extreme energy poverty, but do not reflect actions intended to promote further progress.

Parallel to the definition of access and supply indicators, significant effort has been made to assess those indicators around the world. Table 2 presents a necessarily incomplete compilation of countries and regions where the different indicators presented in this section have been characterized.

Table 2.

Energy supply indices and places where they have been assessed, adapted from [6].

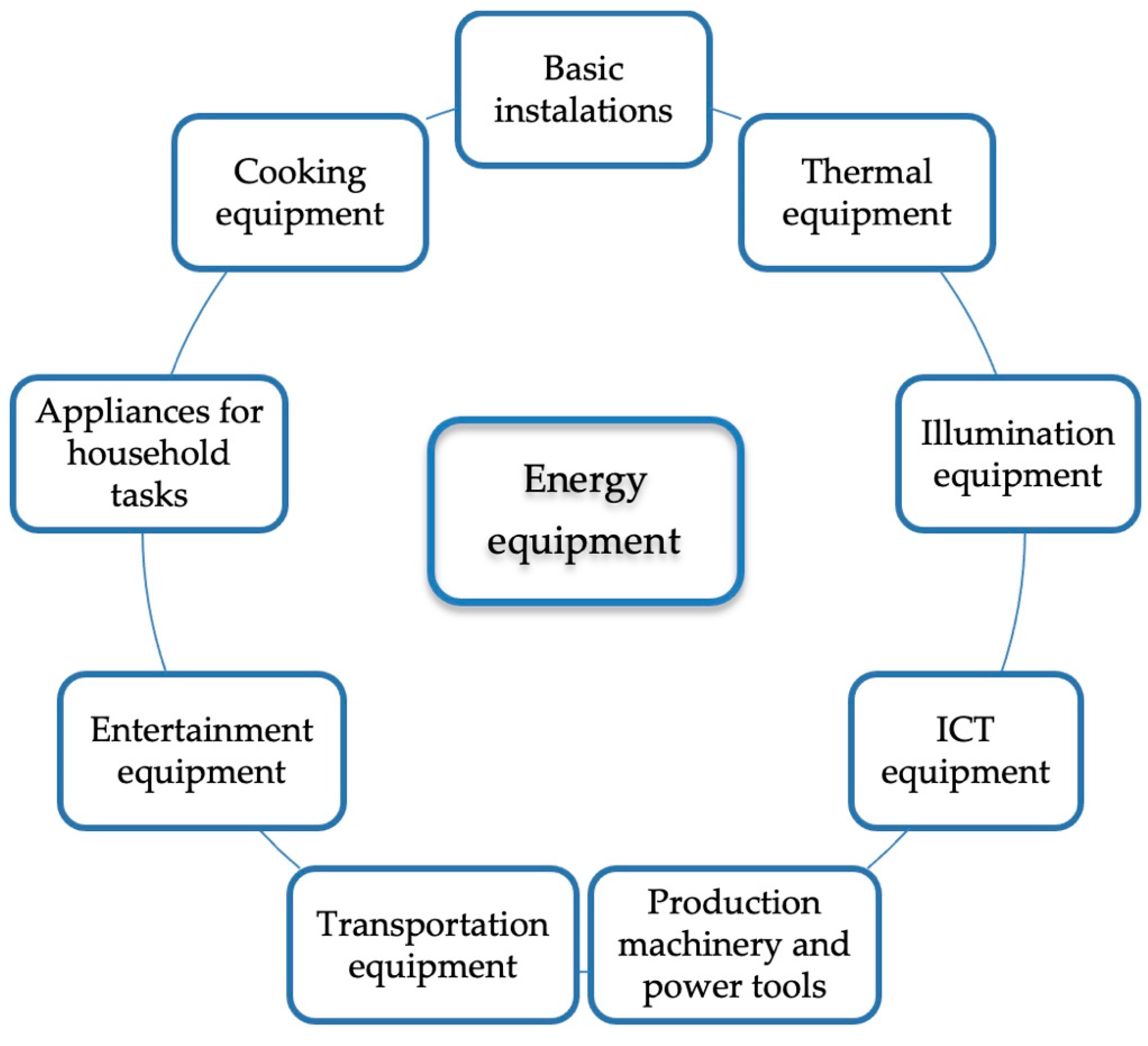

3.2. Access to Energy Equipment

It is somehow curious that indicators seldom deal with the access to efficient energy equipment, while most of them state that a minimum level of access to energy carriers is compulsory. Nonetheless, energy equipment is mentioned in a variety of indicators, notably in general poverty indicators: ownership of a fridge, a TV/radio, or a phone is considered as criteria by both the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) and the Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI). The MPI adds the ownership of a computer and of any means of transportation, from an animal cart or a bike to a van. Regarding general poverty indicators, AROPE includes the ownership of a TV/radio, computer, and car, and adds the ownership of a washing machine as a primary need. But not much information is gathered by the main indicators on the efficiency of available energy equipment, except for the identification of cooking efficiency in the multi-tier framework. The range of efficiencies of available fridges, cookstoves, TVs, phones, or cars can vary within a narrow range, say 20%, but they can also double, triple, or even vary by an order of magnitude (as in lighting with the advent of LEDs). Therefore, the aprioristic statement that a certain amount of energy and power (e.g., electricity) will ensure a service (e.g., 24 h functioning of a fridge) assumes the availability not only of equipment (a fact that includes both supply and affordability) but of efficient equipment (at least to a certain level).

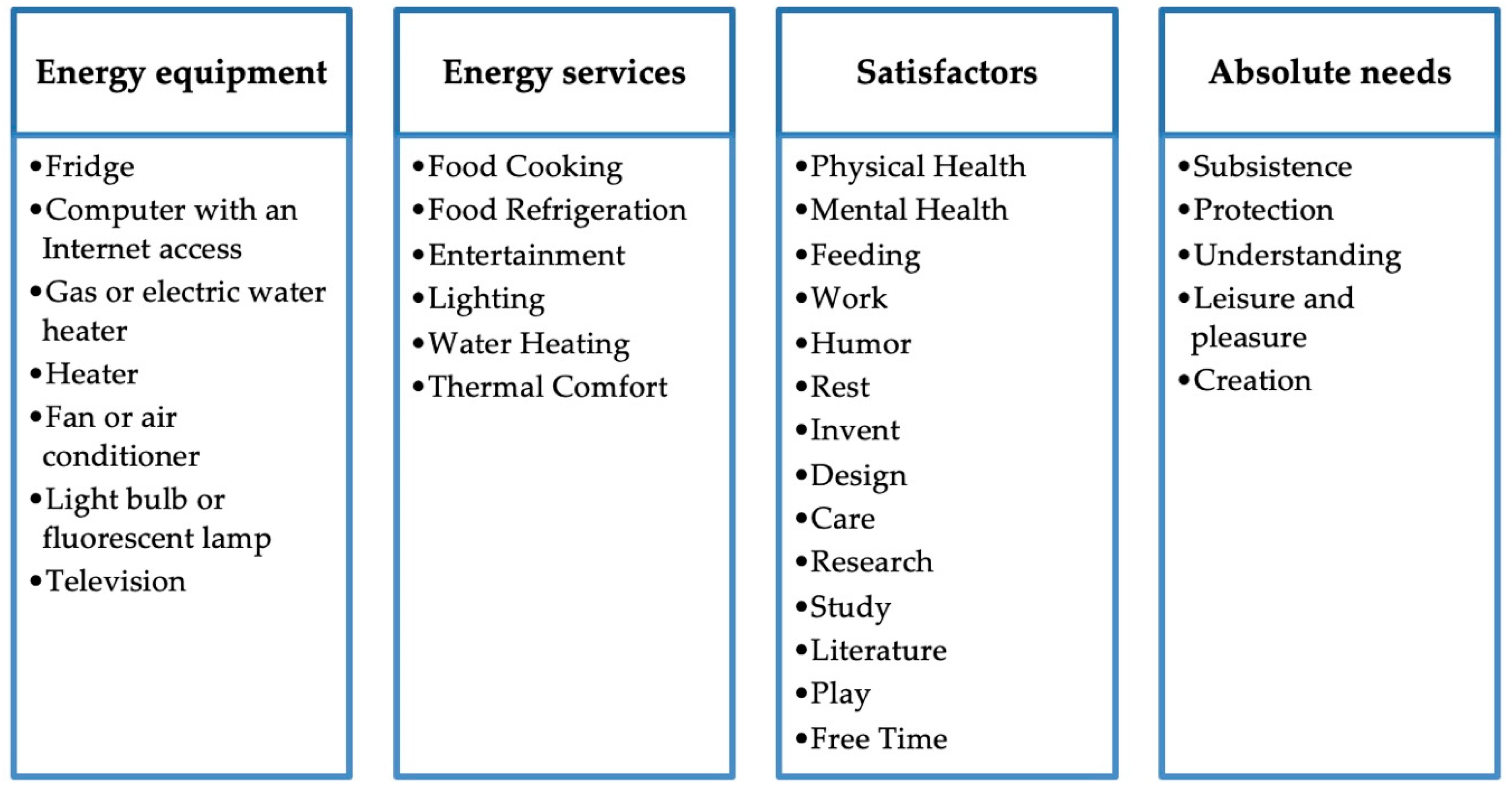

One exception of an index detailing energy equipment is the Meeting of Absolute Energy Needs method [28], which establishes energy poverty as an inability to satisfy basic human needs. To do so, the method defines a range of economic goods that are linked to the satisfaction of those needs. The proposed list of relevant economic goods includes refrigerators, computers (PC or laptop) with Internet access, gas or electric water heaters, space heaters, fans or air conditioners, fluorescent lamps or bulbs, televisions, and gas or electric cookstoves. Following a similar line of thought, a classification of relevant energy equipment is now presented.

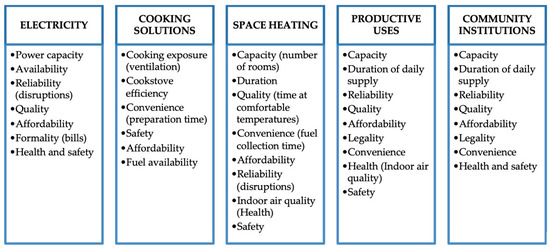

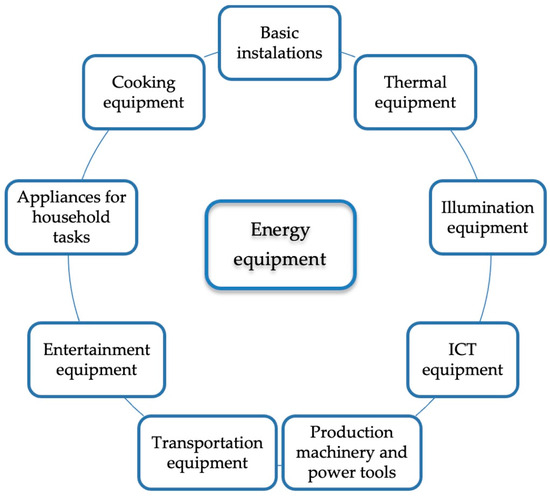

A taxonomy of energy equipment that is relevant for energy welfare is not evident. Different classifications in terms of the energy carrier used (electricity, gas, LPG, etc.) or the service given are possible. A distinction can also be made between energy equipment with an energy use (thermal uses, generators, pumps, etc.) and those with non-energy use (but with energy consumption, such as electronics, cleaning, devices, etc.). The following organization based on uses is proposed and depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Categories of energy equipment.

A category of basic installations has been included to state the need for basic infrastructure, such as sockets, switches, electrical protections, gas connections, exhausts, etc., which is often forgotten. The rest of the categories are self-explanatory. Table 3 elaborates on the categories and the different equipment involved. Information obtained from various sources is compared. A product list is taken from the EU energy efficient products webpage [52], which lists all products (energy equipment) covered by Directive 2009/125/EC. The products are divided into separate categories that generally match those in Figure 4. The EU product list is compared with the product groups in the Collaborative Labelling and Appliance Standards Program [53], an international nonprofit organization that provides a comprehensive comparison of energy standard labels (covering nine major economies and more than 100 products) and also with Japan’s Top Runner programme of energy equipment efficiency [54]. Of course, the comparison from various sources is only meant for completeness of the whole view rather than to highlight differences among sources (which are attributed to the diverse scopes of the different programmes). A quick glimpse at Table 3 shows a general agreement in most categories, with minute differences based on locally relevant equipment (e.g., electric toilet seats). The entertainment category shows low coherence, as it is not generally addressed.

Table 3.

Taxonomy of energy equipment.

Although the categories and types in Figure 4 and Table 3 may remain adequate for different locations, the actual equipment may vary a lot (e.g., the types of cooking devices available may differ between Vietnam and Ecuador, China, or Cuba).

The taxonomy in Table 3 is an attempt to establish a classification of relevant energy equipment that uses energy carriers and is the key feature for delivering energy services. They are thus the link between carriers supplied and services provided. Two major features are relevant for the inclusion of energy equipment indicators in an energy poverty assessment: availability and efficiency. As mentioned above, the efficiency of available equipment may produce a relevant change in the ratio of energy service/energy carrier. This effect is labelled “Service efficiency” in Figure 2. Furthermore, in acute energy poverty circumstances, the actual availability of equipment, or its affordability by part of the population, may render the service inaccessible independently of the carrier energy/power supplied. For example, a rural electrification project might claim that the service of food refrigeration and preservation is available to the target population thanks to the completion of the project. Nonetheless, carrier availability in sufficient capacity (both power and energy) may not assure such a service if the available equipment is too expensive, has very low efficiency (lower than that used by the project engineers to identify energy needs when planning their action), or does not convey the necessities (e.g., there is some availability of small fridges in the region, but no freezers are available).

Therefore, a primary need when assessing energy poverty in a certain location should be to identify a list of available energy equipment, with costs and efficiencies. One may argue that globalization has expanded and unified the market globally, so the main characteristics and availability of equipment are similar worldwide. Still, cultural differences, transport costs and taxes on imported goods, foreign affair issues (e.g., the Cuba blockade, frontier problems in landlocked countries like Armenia), or partial inaccessibility to remote communities can alter the global picture.

3.3. Provision of Energy Services

Not much attention has been directed to the definition and characterization of energy services until recently. This is probably linked to the long-term definition of energy as a commodity, so the uses cannot be defined, let alone limited, as they respond to consumer interests or needs; in short, it is linked to consumer choice. Increased focus on a just energy transition and, as a relevant part of it, on the aspects of energy conservation and energy poverty alleviation has raised interest in the definition of energy services and the discussion of their breadth and relative legitimacy.

Fell [32] studied the previous bibliography of the term and presented a definition and taxonomy of energy services. The definition states that “energy services are those functions performed using energy which are means to obtain or facilitate desired end services or states”. The taxonomy is based on nine general themes or categories in which the author was able to accommodate any service mentioned in the literature reviewed (including a category of “other”). Table 4 recreates the taxonomy of energy services according to this literature revision. The first column shows the nine general terms or categories in which the author organized his findings. The second column shows a compressed view of the information given by the author about the terms involved in the definition of each energy category, and the related aspects. The third column is not derived from this work and shows the links between the different services and the categories of energy equipment defined in the previous subsection.

Table 4.

Taxonomy of energy services, derived from [32].

The analysis of Table 4 shows that the “other” category is overcrowded. Of course, the analysis carried out by Fell 32] only tried to establish representativeness of each service in the literature available at that moment. Therefore, one can state that thermal comfort (space heating and cooling), cooking, water heating, refrigeration, lighting, and transport were generally addressed in the studies on energy services, while the commercial/industrial category was somehow vaguely defined and energy services like those given through ICT or with household appliances were not considered as categories by Fell [32], although they were mentioned in the literature. On the contrary, entertainment was very rarely mentioned as a relevant energy service.

To broaden the debate on energy services and its taxonomy, a comparison of the list of categories in [32] with other relevant previous lists and with some published afterwards is presented in Table 5. A certain coherence can be observed in the more assessed services (heating, cooling, cooking, refrigeration, lighting, transport) although some curious groupings exist. Grouping of heating and cooling into the category of thermal comfort is irrelevant, and it is a consequence of considering that the objective is common: to maintain indoor temperature within restricted limits. Grouping of cooking and refrigeration into terms like sustenance or merely food is again a question of scope. On the other hand, the regrouping of cooking and water heating is probably due to technological reasons: the target population may use one single facility for both purposes. Entertainment is still seldom considered, while concepts like structure (i.e., materials used to provide structural support, commercial/industrial, or production issues) are irregularly defined and may have a variety of points in common.

Table 5.

Grouping of energy services by several authors.

As a working conclusion of the taxonomy of energy services, a list of 13 categories could be proposed, with the aim of being comprehensive in services and choosing to separate grouped categories that show relevant differences. Such categories are space heating and cooling, refrigeration, cooking, water heating, appliance services (mostly cleaning appliances), lighting, transport (passenger and freight), production services (process heat, mechanical work), ICT, entertainment, and structure. Community services might be included or excluded depending on the scope.

Not all categories might be relevant for all, and the number of legitimate and relevant energy services for a certain society that should be included in each category may vary a lot, together with the level of energy carrier capacity (both energy and power) required and the energy equipment needed. Cultural issues may have an effect (cooking issues are generally the most affected, but not the only ones). Of course, environmental characteristics will affect the identification of essential services, minimizing or even eliminating some energy services and highlighting others (space heating and space cooling are evident examples). This is considered, for example, in the definition of the Meeting of Absolute Energy Needs method [28], in which the index is made up of different essential needs for populations living in different climate regions.

3.4. Improvements in Living Conditions

Having filled the gap between access to energy carriers and equipment and provision of energy services, the next step concerns actual improvements in living conditions obtained by using such services. Kalt and co-workers [25] provided an interesting discussion on what they call benefits and values as descriptors of wellbeing. Day and co-workers [9] presented relevant insights into the nature of benefits, following the capability approach of Sen and Nussbaum. Brand-Correa and co-workers [26,58] and García-Ochoa [28] identified such benefits using the basic needs approach of Max-Neef. Also, there is a relevant line in development studies that focus on wellbeing and measurements of happiness [59]. Finally, the approaches to poverty in general, as detailed in the second section of this work, may provide a direct approach to identifying improvements in living conditions in the sense that an action to reduce energy poverty should have an impact on poverty reduction in general.

3.4.1. Benefits in Terms of Satisfied Needs

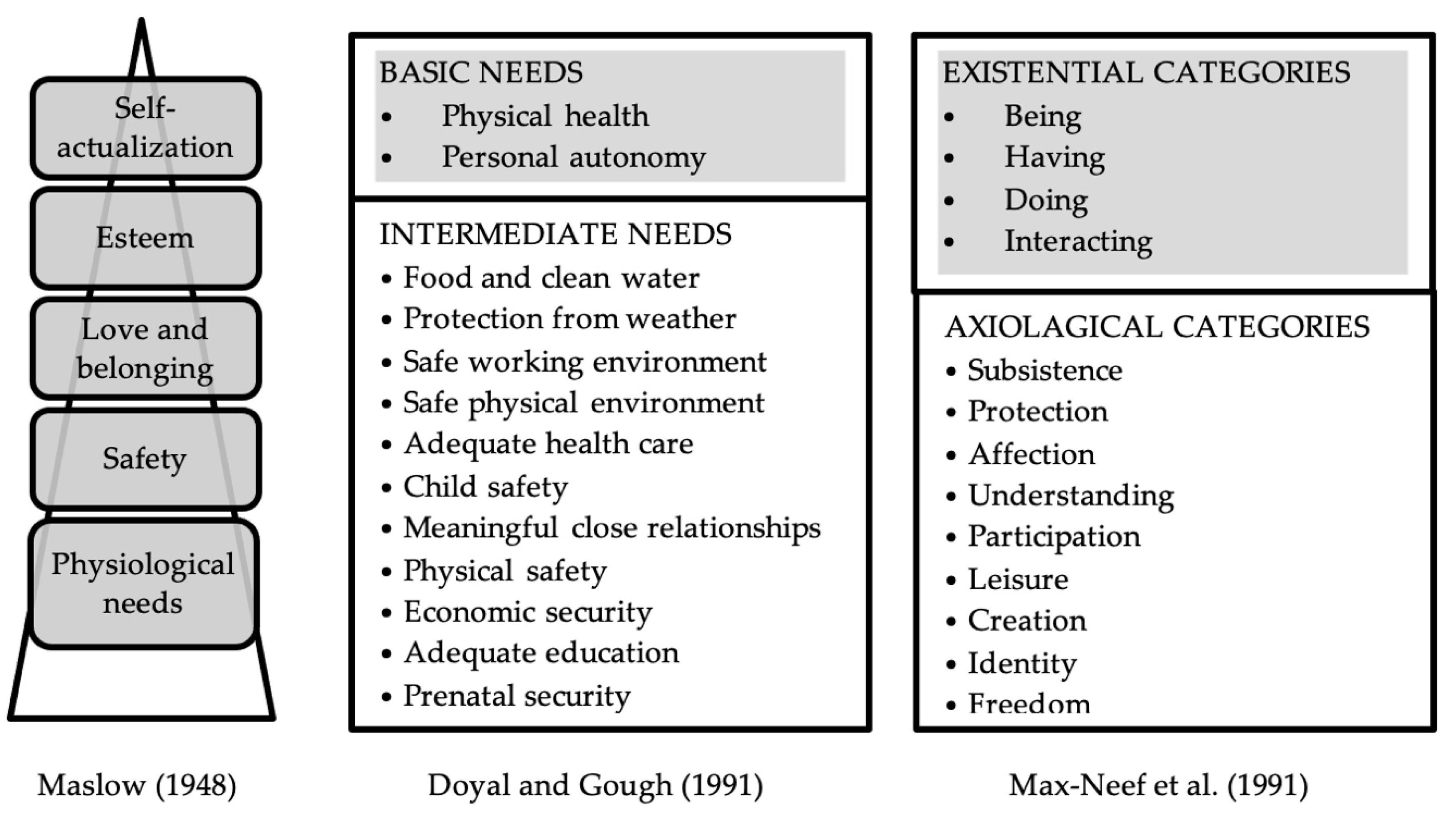

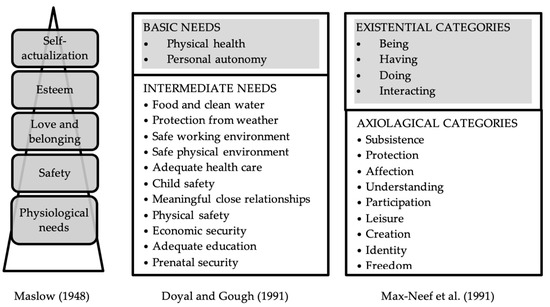

The basic needs approach was established with the works of Doyal and Gough [60,61] and Max-Neef and collaborators [27]. They discuss and propose taxonomies of basic human needs. The common precedent is the pyramid of Maslow [62], a hierarchical organization of basic needs that defines five levels in which the lower ones represent priority needs. The authors of these works consider, on the contrary, that basic needs are not hierarchical. They also define two interacting concepts: actual needs, which should be objective and universal and are finite and few, and satisfiers, which may change through time and across cultures, can be enormously varied and numerous, and define the ways in which a society proposes to meet its own needs. This dichotomy is an argument in the long discussion on the universality and cross-culturalism of human needs maintained with advocates of relativism. In this sense, ref. [60] defines basic needs as universalizable preconditions for both social participation and the pursuit of personal goals. For such goals, the authors identify two basic human needs: physical health and personal autonomy (capacity for action). From those, they derive 11 categories of intermediate needs, that they also considered universal and cross-cultural. In [27], in turn, an array of categories based on two orthogonal vectors is proposed: existential categories and axiological categories. Max-Neef and coauthors claim that the values defined in their nine axiological categories (which can relate, with some differences and discussion, to the categories of Maslow and the intermediate needs of Doyal and Gough), are defined differently in four existential ways, those of being, having, doing, and interacting (a similar issue as the “functionings” of the capability theory that will be addressed in the next section). This forms a matrix where the cultural satisfiers could be integrated. The categories for Max-Neef are again universal and cross-cultural but might vary in time, as global society does. In this sense, they discuss the relevance of identity and freedom as quite “modern” needs in comparison with the rest, which are considered by them as grounded in the beginnings of humanity. They also raise the subject of introducing transcendence needs but conclude that it is still an immature need in most societies around the world.

A comparison of the taxonomies of Maslow [62], Doyal and Gough [61], and Max-Neef and co-workers [27] is addressed in Figure 5, including the listing of their different categories.

Figure 5.

Three relevant taxonomies of basic human needs [27,61,62].

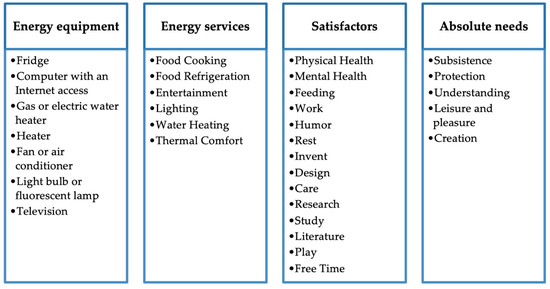

These frameworks provide a useful approach for the characterization of the change in living conditions experienced by a change along the energy supply chain and/or in the provision of energy services. García-Ochoa and collaborators [28,56] proposed an organization of energy equipment (economic goods, in their words), energy services, satisfiers, and absolute needs following the Max-Neef taxonomy. An outline of their organization is depicted in Figure 6. Brand-Correa and Steinberger [58] also proposed an organization of human needs and energy services using the axiological categories of Max-Neef in their Human Scale Energy Services analysis. They linked energy services and human needs in two Colombian communities using a community-level participatory approach.

Figure 6.

Outline of a cascade of energy equipment, energy services, satisfiers, and absolute needs, following [28,56].

These contributions show the possibilities of the basic needs approach to characterize the benefits obtained by the community and closing a general framework to assess energy poverty and energy poverty alleviation strategies encompassing energy supply (carriers and equipment), energy services, and their effect on living conditions.

3.4.2. Benefits in Terms of Capabilities

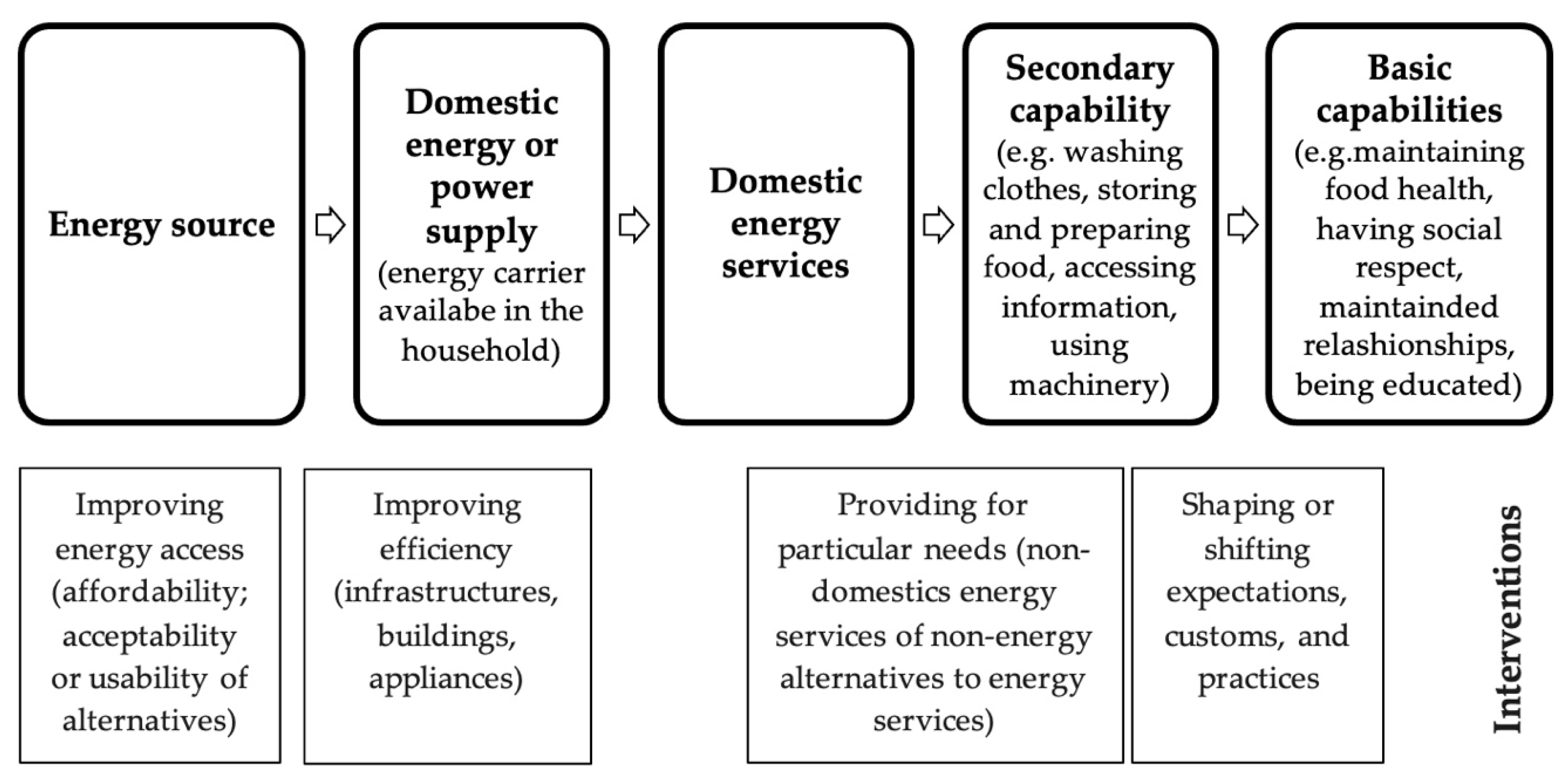

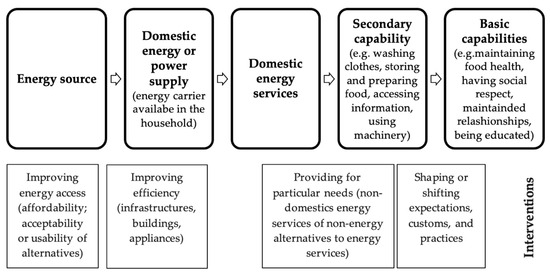

Sen and Nussbaum’s capability theory is also a well-established methodology to identify benefits of the energy cascade. Sovacool and co-workers [63] and Day and co-workers [9] have applied the capability approach to energy poverty.

The capability approach tries to maximize opportunities by highlighting freedom of choice and focusing on what people can achieve and do. The methodology uses two linked concepts: functionings and capabilities. Functionings are defined as “beings and doings” to incorporate both states and activities, while capabilities are viewed as opportunities to develop functionings (states or activities) and are divided into primary and secondary capabilities. Primary capabilities are general concepts like being respected (a state) or acquiring skills and knowledge (an activity) and secondary capabilities are intermediate concepts (and, as such, nearer to energy services) that built on primary capabilities such as maintaining hygiene standards. Some parallelism can be observed with the taxonomy of needs of Max-Neef, but relevant differences are also present: the capability approach is a methodology that does not define normative capabilities. They are the result of a participatory process of each community. The categories presented by Nussbaum [64], although quite broad, were the subject of a strong debate and they were even branded as ethnocentric (i.e., life, bodily health, bodily integrity, senses, imagination and thought, emotions and practical reason, affiliation, relating to other species, play, and control over one’s political and material environment).

Following Nussbaum’s statement that energy is a material prerequisite to achieving valued capabilities, Day and co-workers [9] proposed a definition of energy poverty in terms of the deprivation of such capabilities. They conceptualized the relationship between energy, services, and outcomes and identified fields of action (interventions for energy poverty alleviation) in the linkages. Figure 7 is adapted from their work.

Figure 7.

Relationship between energy, services, and outcomes, with related interventions for energy poverty alleviation, adapted from [9].

Of special interest is the shaping of interventions for energy poverty alleviation. Improving energy access and efficiency has been discussed previously. In the transition between secondary and basic capabilities, Day and co-workers [9] identify the need for modifying the way in which a society imagines such links, which is of course a satisfactory solution and a problem on its own. This is more a domain for capability theorists than for the analysis of energy benefits. The focus might point to the transition from services to secondary capabilities. The authors suggest that some capabilities should be obtained with community services and others might be obtained with non-energy services. This is a sound statement. Community services could be included in the energy services stage (as stated previously), as the problem is, in fact, an issue of the organization of the provision of energy services more than an issue of the interaction between services and benefits. On the other hand, non-energy services are considered fundamental, and the way some traditionally non-energy services have been displaced by energy-consuming services is a characteristic feature of modern societies. Both aspects are relevant, but little attention is drawn to the way some energy services can fulfil secondary capacities better than others (a certain service-benefit efficiency). This is a key issue, as services that use adequate equipment and carriers, and have the acquired experience of users, may be more efficient than others. This might encompass issues related to (a) access to the form of energy service provision appropriate to household needs; (b) the mismatch between requirements and available energy services; and (c) acquiring knowledge about using energy or asking for support, three key aspects of energy poverty highlighted by the authors of [8] in their typology of energy vulnerability factors and their constituent elements.

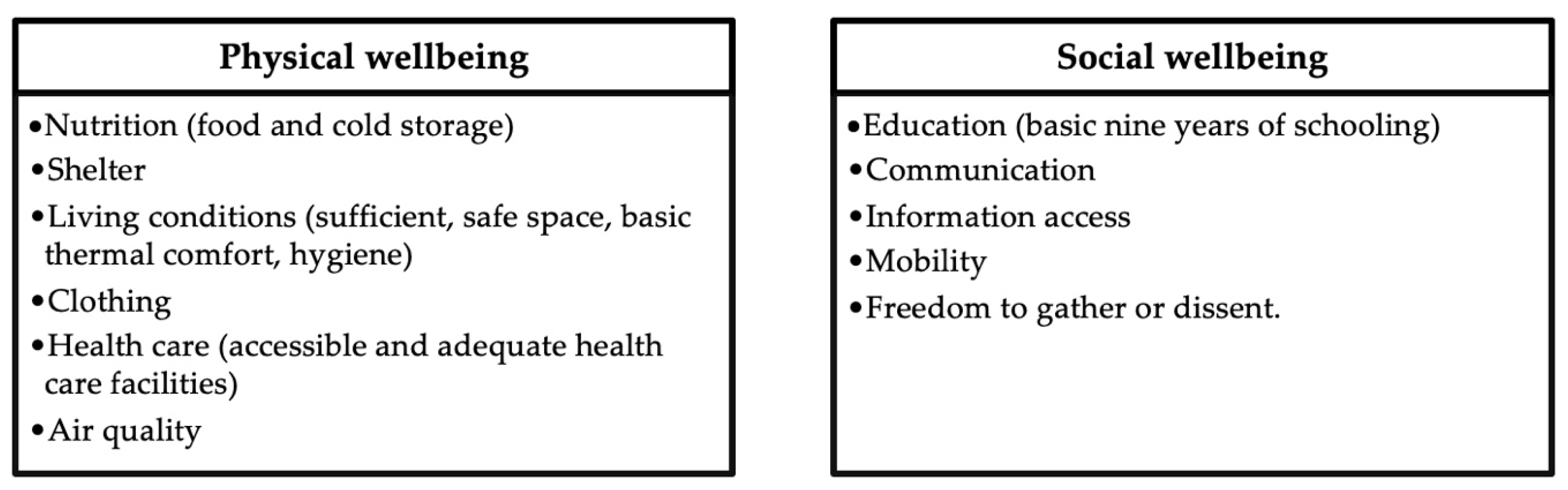

3.4.3. Benefits in View of Wellbeing and Happiness

There is a large variety of wellbeing approaches. Loveridge and co-workers [59] analyzed 111 different available indicators for a field test. Boarini et al. [65] identified three distinct dimensions of wellbeing studies: objective (focusing on material conditions), subjective (based on self-assessment of personal circumstances) and relational wellbeing (evolving from Sen’s capability approach). Finally, Brand-Correa and co-workers [26] confronted ‘eudaimonic’ (need-centred) and ‘hedonic’ (pleasure-centred) understandings of wellbeing in their aim of establishing priorities for achieving wellbeing within environmental limits.

Objective wellbeing may appear more adequate to assess improvements in living conditions from energy services, as it focuses on material prerequisites for human wellbeing. Rao and Min [66] identified a series of decent living standard dimensions that were linked with material requirements often related to energy. Their dimensions are listed in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Decent living standard dimensions for objective wellbeing according to [66].

On the other hand, subjective wellbeing indicators are used to correlate with development indicators. Every year, the UN presents a World Happiness Report linked to the activities of SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing). The report presents results for the Cantril life ladder, a simple indicator that is based on a single survey question, asking the respondent on which step of a ladder of ten steps, where the highest one represents the best possible life and the lowest the worst, they think they are now. Of course, this is based on the philosophical concept that people’s self-asserted happiness should be the ultimate goal of policy. But the use of such subjective indicators to assess benefits derived from energy services seems rather crude and obscure.

The main argument in favour of subjective wellbeing analyses is their bottom-up nature. Nonetheless, the variety of approaches and variants are the subject of much debate and criticism because they claim to be or appear natural while sometimes being strongly ideologically charged.

3.4.4. Benefits Identified by Reduction of Poverty Indices

The effect of the provision of energy services on the reduction of poverty indices is another possibility to identify clear improvements in living conditions. It might even be an implicit and direct result of energy provision, as some poverty indicators include aspects directly linked to energy poverty, as stated in Table 1 in the second section of this work. An action modifying the lack of access to electricity or clean fuels in a household or a community will directly modify the results for the Multidimensional Poverty Index of that household or community. Such a change might make the household reach an indicator value that no longer establishes it as a poor or extremely poor household. Also, as energy aspects are lightweight and only partially affect the indicator value, the household may not leave its condition, but will at least certainly reduce the intensity of its deprivation as measured by the index.

Other outcomes can be obtained less directly from aspects that indicate poverty and that may change because of an action to address energy poverty, such as having a computer, a television, or access to drinking water.

Overall, the assessment of the efficiency in alleviating poverty conditions of the provision of energy services can be a sound identification of major improvements derived from energy projects.

4. Discussion

Energy poverty is a global problem. In recent decades, there have been significant advances in understanding and responding to this problem, both academically and politically. Studies have often focused on the problems of the Global North, but those of the Global South have also received attention, interacting with traditional international development aid efforts and expanding them. Still, the perspectives on addressing the problem of energy poverty in the Global South (an access to supply issue) and North (an affordability issue) differ greatly.

Several authors ([8,9,25,56,58], etc.) have addressed this problem in recent decades. Most have focused on the issue of energy services in their efforts to establish a global perspective on domestic energy poverty. Services are a midway point between carrier and equipment supply on one side and improvements/benefits/progress obtained by society on the other. Its indefiniteness as a term [32] allows it to encompass all the relevant aspects of the problem, as the different approaches of the mentioned authors show. A similar debate has been established in the past around the concept of ecosystem services, with parallels that make close reading fruitful [31,67,68].

The aims behind the various attempts to identify a broad and (as far as possible) global perspective on the problem of energy poverty are also varied, from a direct amelioration of energy deprivation in the home [8] to a broader aim of establishing priorities for achieving wellbeing within environmental limits in an ecological crisis scenario, and thus decoupling the satisfaction of human needs from energy use [26,58], or the previously mentioned search for coherence between Global North and South attempts [9]. Kalt and co-workers [25] focussed on systematizing terminology to promote interaction between exclusionary discourses, with a more epistemological aim. García Ochoa and collaborators [28] sought a specific definition of indicators that would be appropriate for the varied conditions of the Latin American context. Moreover, most authors highlight the importance of such a global perspective for the definition of a variety of methods of intervention to tackle the problem of energy poverty. The sum of those purposes generates extremely ambitious goals. In this work, while primarily focussing on the Global South issues, all those aims have been at least considered in the systematization analysis.

Figure 9 presents a compressed view of the general framework outlined in Figure 2 and characterized in detail throughout the previous section. Supply is defined by the availability of both energy sources and carriers and energy equipment, with a variety of pair combinations. Sources and carriers include electricity and modern fuels together with primary (direct use of) renewables, mechanical power, and secondary heat. Non-commercial forms of energy like firewood or human power are also considered. Equipment categories are those presented in Figure 4 and Table 4 and Table 5. Services are accomplished when supply is granted, and coverage and quality of services can be defined, together with efficiency (η) between supply and service. Service categories in Figure 9 are extracted from a comparison between Table 4 and Table 5, trying to be as comprehensive as possible. Finally, the benefit section defines the different options or approaches for identifying a positive assessment of service, either by individuals or communities, as have been analyzed in Section 3.4. Those options can be used independently or overlapped or merged in an assessment.

Figure 9.

Framework for evaluation of energy poverty.

Comparing Figure 9 with the previous attempts summarized in the preceding sections may provide some insights. The two proposals in Figure 2 are somewhat complementary. One considered services as the final benefit [8], thus contracting the framework on the right-hand side. The other broadened benefits to differentiate individual and societal issues [25], thus expanding the framework to that right-hand side. The basic needs proposal of [28,56], depicted in Figure 6, has a similar layout to that of Figure 9 (energy carriers are not present because they are identified as a pre-established necessity). Notably, it includes equipment defined as economic goods. Looking at the taxonomies, García-Ochoa proposes a rather sharp reduction in relevant equipment and services in his quest for bare necessities. Brand-Correa and Steinberger ([58], their Figure 4) proposed a similar scheme (energy supply chain/services/need satisfiers/wellbeing), but disregarding energy equipment. Finally, Day and co-workers [9] used the capability approach to wellbeing and (trying to provide some insight on the energy chain itself) separated the energy chain in energy sources and domestic energy carriers, as shown in Figure 7. Considering all these approaches, the framework in Figure 9 expands or compresses their findings, encompassing all dimensions.

Focusing on services as the pivotal point of a global perspective also means taking sides in the dilemma between direct and indirect approaches to poverty assessment. Standardized approaches to poverty and energy poverty focus on income and expenditure indicators, which are an indirect measure of poverty. This means addressing material problems through some a priori consensus. In energy poverty studies in the Global North, Boardman’s categorization of the determinants of fuel poverty is widely accepted: household income, cost of fuel, and the energy efficiency of the dwelling. In the Global South, the focus of most of energy poverty studies is still on the severe cases of extreme energy poverty (following development aid scenarios), and thus the emphasis is on carrier access indicators (as stated in Section 3.1). It is again an indirect approach to material problems (e.g., having access to electricity does not directly imply enjoying the possibilities of food preservation provided by a refrigerator: it is only a prerequisite for this). The use of a global perspective implicitly requires a shift to direct indicators centred around material problems, as the metabolic patterns of energy vary among global societies. The focus on energy services or even on the effects of these services on the living standards of the population shows that shift.

The fact that energy poverty studies in the Global South are often restricted to development aid scenarios, views, and agreements is of substantial relevance, firstly because they focus on extreme cases, as stated in the previous paragraph. Often, such cases involve most of the target population, but other situations of energy poverty may be shadowed, like the impact of cold homes in the Global South [43]. Using a framework with energy services at its core can broaden the view and integrate concepts of dignity and justice [8] to assess the problem. A second feature is inherited from the debate between humanitarian, relief, and development actions, traditionally embedded in the development aid ecosystem. This is a discussion on community appropriation and leadership of development processes. It is essential that action against energy poverty explores its capacity for change, a question central in the capabilities and basic needs approaches to development but sometimes neglected in other approaches and assessment indices. A third step confronts ‘eudaimonic’ (need-centred) and ‘hedonic’ (pleasure-centred) understandings of progress and wellbeing [58]. These approaches see the fight against (energy) poverty as an opportunity for human flourishing. This obviously takes the side of a certain concept of human wellbeing, which can lead to a debate on the prioritization of some energy services over others.

Coming back to the framework of Figure 9 and comparing it to previous proposals analyzed in Section 3, the major contribution of this framework is the inclusion of energy equipment as a fundamental dimension. One of the three determinants of fuel poverty of Boardman [13], energy efficiency of the dwelling, involves two energy efficiencies: the efficiency of the building and the efficiency of the energy equipment used to provide services within the household. Building efficiency is a question of insulation, as well as including aspects such as ventilation, orientation to the sun, or bioclimatic design issues. If included, its place should be in the energy equipment dimension, but it seems awkward to mix both concepts. An effort to integrate this relevant aspect should be undertaken. Concerning energy equipment, its placement as a fundamental dimension in the framework puts into focus not only the efficiency of any equipment, but its availability, affordability, and the range and capacity of what it can provide. The different analyses with a global perspective on domestic energy poverty seldom identify energy equipment issues. Apart from the analysis of García-Ochoa [28], consisting of seven basic types of equipment, there is only an occasional mention of the efficiency of some equipment in the other proposals. Nevertheless, Bouzarovski and Petrova [8] consider of paramount importance the aspects of efficiency and flexibility that link carrier supply to service, obviously referring to energy equipment.

No single approach has been identified in the proposed framework as preferential to identify a positive human assessment. This dimension encompasses personal, social, and political valuation of energy services. Even naming this dimension may be a subject of discussion. We have opted at times for benefits (a word with accounting resonances) and others for improvements in living conditions. Opting between the capabilities approach, the basic human needs approach, or the different wellbeing/happiness approaches, all with their varieties, is outside the scope of this work. Some indicators of poverty are also included as a parallel approach to identify the effects of energy services on development.

A word about efficiencies in the interspaces between dimensions: they identify the performance of carriers and equipment to provide adequate services, as well as the performance of services to achieve valuable improvements in living conditions. Therefore, they are the key aspects of the framework, as an adequate supply of all the necessary items might end up in a poor service and, in a second step, in a lousy improvement, or even with the opposite effect: a deterioration of living conditions.

In a sense, these efficiencies define possibilities to deviate from the general assumptions embedded in the conceptual core of indirect measures (that A implies B), through mechanisms that might alter the expected outcomes of adequate supply or, conversely, multiplicative effects, synergies, or synchronicities that may amplify the impact of simple actions on wellbeing. These efficiencies depend on unforeseen, unidentified, or unaccounted for parameters in the logic of action, on parallel, incidental processes, or on the appropriation and modification that societies make of new possibilities.

Finally, the definition of alleviation strategies, ways of intervention to tackle the problem of energy poverty, is a key feature of any assessment methodology. An indicator defines a level and characterizes with it the magnitude of a problem, but it also identifies changes, better or worse, for the available increments of such levels. In this sense, the presented framework provides a rich environment for identifying energy supply development actions intended to promote progress. Traditional energy poverty indicators for the Global South are binary and centred on extreme precariousness (SDG7 targets, MEPI) and as such can only define progress in a binary (has/has not) logic. Non-binary indicators like the World Bank multi-tier framework provide a much larger catalogue of actions, for example following a change in installed power capacity. The proposed framework uses such indicators but includes other performance indicators for energy supply projects that go beyond characterizing energy access to assess the provision of services and the concrete impacts on living conditions. Therefore, indicators of provided energy services (binary indicators or tier indicators with levels of service in terms of hours, capacity, or features) or improvements in living conditions (exploring changes in capabilities, subjective or objective wellbeing, satisfaction of basic needs, alleviation of poverty by a change in its current assessment indices, etc.) are available to identify the variety of impacts of an energy supply on a society’s or household’s energy metabolism.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a review of attempts to construct indicators to characterize energy poverty in the Global South, together with the proposal and discussion of a broad conceptual framework that allows for a multi-faceted assessment.

Current mitigation strategies and the very concept of energy poverty in developing regions follow the agreements of the development agenda (Sustainable Development Goal 7, World Bank “beyond connections” strategy), focusing on electricity connections and clean cooking fuels.

But addressing the lack of basic access to modern fuels and energy carriers and the dependence on traditional biomass with simple (binary) access indicators masks other features of the problem. Following this line of thought, some attempts, like those of the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative and the World Bank, deal with the concept of energy services. But these approaches still focus on access to carriers. Services are considered to be covered through indirect and specific aspects incorporated into the carrier assessment, such as the possession of basic equipment (fridge) or its performance (cookstove) or, in the World Bank’s more ambitious attempt, with the definition of a wide range of indicators that identify in detail the conditions of access to energy carriers, characterizing their capacity, availability, or affordability and thus indicating their potential to provide energy services.

Broader approaches centre explicitly on energy services, identifying their taxonomy. In these proposals, services are (a) the result of the establishment of an energy chain that provides a reasonable supply and (b) the prerequisite for the improvement of human wellbeing. This vision allows energy poverty to be understood as a lack of services that undermines the maintenance of decent living conditions. In this way, it allows for a much more detailed view of the problems caused by the dependence on biomass and the lack of or inadequate access to electricity and modern fuels, while making visible other parallel issues identified by the absence of services and generally not addressed in access-based strategies, such as space heating and cooling, productive tasks, communication, entertainment, or transportation.

While the supply side of the framework has been the subject of interest of most assessments and mitigation strategies, the wellbeing side has centred the debate around development and policy studies in the last half-century. Assessments of the improvement of living conditions caused by the provision of energy services may rely on several well-established or emerging approaches, from Sen and Nussbaum capability theory to the basic human needs approach (involved and competing in the definition of the UN strategy of the Millennium Development Goals), and the variety of wellbeing approaches (including the one used to produce the World Happiness Report, a key feature of SDG 3 devoted to good health and wellbeing). The identification of synergies between poverty and energy poverty indicators and mitigation strategies may also provide a simple parallel approach to state the benefits and values of energy services.

This work highlights the relevance of energy equipment as an often neglected but key item in the energy chain. The availability and affordability of adequate energy equipment, together with a certain flexibility of choice among items, are basic issues to make an energy service feasible. Nonetheless, the characteristics of locally available equipment are seldom addressed in energy poverty assessments. A taxonomy of energy equipment is presented, derived from several surveys on energy efficiency standards throughout the world.

The discussion section analyses the applications of the assessment framework, as well as its advantages and disadvantages. Applications have been described and attempted by several authors in the past. This perspective allows for a more detailed characterization of energy poverty in the Global South and can thus help to mitigate it. In a broader view, it could serve to improve coherence between Global North and South schemes on energy poverty. While normative indicators in developed countries centre on thermal comfort as the key service that the energy-poor lack, this perspective provides a tool to extend the view to the lack of other services or other problems, deficiencies, or inadequacies in the supply–service–wellbeing chain that might identify cases of extreme energy poverty in the Global North. Looking even further, the framework may serve to identify strategies for decoupling the satisfaction of human needs from energy use in an ecological crisis scenario.

If this methodology (or similar ones) was widely applied, in parallel with the current analysis of access to the energy chain, some benefits could be achieved. This type of assessment provides a generalized view of energy poverty: one could compare, in terms of service provision (and need for services), the incidence of energy poverty in the Global North and South and between rural or urban areas or climate zones. Access is a relevant aspect, but it creates a separation between two worlds (with/without), which prevents a broader view that the observation of services could provide. The effect of climate change on energy poverty, for example, can be further studied by analyzing the changes it causes, both in the services needed in each area (e.g., the need for heating or cooling to achieve thermal comfort for households) and in the availability of services in each area (e.g., less or different availability of energy resources—fuel scarcity—to provide services). Energy has been a commodity for more than a century. A global cutback in its consumption while maintaining an ideal of justice and equity requires the identification of energy services that are indispensable and those that can be considered as ancillary or even superfluous. This extremely complex analysis would be much more complicated if the indispensable/superfluous concept is applied to energy carriers.

Energy is one of the fundamental requirements and guarantors of a dignified and healthy life. But it is a finite, costly resource with side effects. In a scenario of control (and reduction) of energy consumption and climate change, the identification of priorities in energy consumption and the global assurance of their satisfaction is a determining aspect. In this paper, we present a critical review of works to establish the basis for such priorities or minimum criteria, focused on the mitigation and elimination of energy poverty. In the Global South, traditional approaches derived from the development agenda highlight supply from the energy chain. But supply is a necessary but insufficient goal. It cannot by itself assure a proper energy service, and, in turn, service availability may not assure a clear impact on living conditions. While keeping in mind that the discussion on what constitutes wellbeing might be an eternal dilemma, academics and policy makers shall focus on the energy chain, but also beyond it to the interactions and efficiencies in the provision of services and the fulfilment of achievements that may assure decent living conditions for all.

Author Contributions

U.R.-R.: conceptualization, research design, writing—original draft preparation, and final validation; J.M.-C.: result visualization, review, editing, and supervision; M.C.-S.: result visualization and review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This work is partly the result of many discussions over the years. Those shared during the FIIAPP workshop “Workshop on the construction of energy indicators of sustainable local development associated with renewable energy sources in isolated communities and rural environments” (R.1.1.A.3-3) held in Cuba in 2022 with members of the UNDP FRELocal project, and conversations held with Angel Brito of the University of Oriente, Cuba, Reineris Montero of the University of Moa, Cuba and Omar Masera of UNAM, Mexico have been particularly useful.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Primc, K.; Dominko, M.; Slabe-Erker, R. 30 years of energy and fuel poverty research: A retrospective analysis and future trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 301, 127003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, G.; Mei, H. Mapping the worldwide trends on energy poverty research: A bibliometric analysis (1999–2019). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevara, Z.; Mendoza-Tinoco, D.; Silva, D. The theoretical peculiarities of energy poverty research: A systematic literature review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 105, 103274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H.; Day, R.; Ricalde, K.; Brand-Correa, L.I.; Cedano, K.; Martinez, M.; Santillán, O.; Delgado Triana, Y.; Luis Cordova, J.G.; Milian Gómez, J.F.; et al. Understanding, recognizing, and sharing energy poverty knowledge and gaps in Latin America and the Caribbean—Because conocer es resolver. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 87, 102475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Delina, L.L. Energy poverty and beyond: The state, contexts, and trajectories of energy poverty studies in Asia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 102, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rivas, U.; Tahri, Y.; Arjona, M.M.; Chinchilla, M.; Castaño-Rosa, R.; Martínez-Crespo, J. Energy poverty in developing regions: Strategies, indicators, needs, and technological solutions. In Energy Poverty Alleviation; Rubio-Bellido, C., Solis-Guzman, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelz, S.; Pachauri, S.; Groh, S. A critical review of modern approaches for multidimensional energy poverty measurement. WIREs Energy Environ. 2018, 7, e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S. A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: Overcoming the energy poverty–fuel poverty binary. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.; Walker, G.; Simcock, N. Conceptualising energy use and energy poverty using a capabilities framework. Energy Policy 2016, 93, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado Herrero, S.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D. Trapped in the heat: A post-communist type of fuel poverty. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rivas, U.; Tirado-Herrero, S.; Castaño-Rosa, R.; Martínez-Crespo, J. Disconnected, yet in the spotlight: Emergency research on extreme energy poverty in the Cañada Real informal settlement, Spain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 102, 103182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I.; Streimikiene, D.; Lekavicius, V.; Balezentis, T. Energy poverty indicators: A systematic literature review and comprehensive analysis of integrity. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, B. Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth; Belhaven Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, H.; Bouzarovski, S.; Snell, C. Rethinking the measurement of energy poverty in Europe: A critical analysis of indicators and data. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirado-Herrero, S. Energy poverty indicators: A critical review of methods. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birol, F. Energy Economics: A Place for Energy Poverty in the Agenda? Energy J. 2007, 28, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Eguino, M. Energy poverty: An overview. Ren. Sust. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarakoon, S. A justice and wellbeing centered framework for analysing energy poverty in the Global South. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 165, 106385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Durand-Delacre, D.; Teksoz, K. An SDG Index and Dashboards—Global Report; Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN): New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/sdg-index-dashboards (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- UN. General Assembly, 71st Session. Work of the Statistical Commission Pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Sustainable Development Report 2019—Transformations to Achieve the SDGs. United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network. 2019. Available online: https://www.sdgindex.org/reports/sustainable-development-report-2019/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Bhatia, M.; Angelou, N. Beyond Connections—Energy Access Redefined; ESMAP Technical Report 008/15; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/a896ab51-e042-5b7d-8ffd-59d36461059e (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2010. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Paris. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2010 (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Malla, S. Household energy consumption patterns and its environmental implications: Assessment of energy access and poverty in Nepal. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, G.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Görg, C.; Haberl, H. Conceptualizing energy services: A review of energy and well-being along the Energy Service Cascade. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 53, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Correa, L.I.; Martin-Ortega, J.; Steinberger, J.K. Human scale energy services: Untangling a ‘golden thread’. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 38, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max-Neef, M.; Elizalde, A.; Hopenhayn, M. Human Scale Development. Conception, Application and Further Reflections; The Apex Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ochoa, R. Pobreza Energética en América Latina. 2014. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/36661 (accessed on 20 May 2024). (In Spanish).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023 (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Nussbaumer, P.; Bazilian, M.; Modi, V. Measuring energy poverty: Focusing on what matters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. The links between biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being. In Ecosyst. Ecol.; Raffaelli, D.G., Frid, C.L.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 110–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, M.J. Energy services: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 27, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.J.; Aye, L. Human and animal power—The forgotten renewables. Renew. Energy 2012, 48, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liao, H. Energy poverty and solid fuels use in rural China: Analysis based on national population census. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2014, 23, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaumer, P.; Nerini, F.F.; Onyeji, I.; Howells, M. Global Insights Based on the Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI). Sustainability 2013, 5, 2060–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, C.B., Jr.; Cayonte, D.D.D.; Leabres, M.S.; Manaligod, L.R.A. Understanding multidimensional energy poverty in the Philippines. Energy Policy 2019, 133, 110886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillán, O.S.; Cedano, K.G.; Martínez, M. Analysis of energy poverty in 7 Latin American countries using multidimensional energy poverty index. Energies 2020, 13, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Gasparatos, A. Multi-dimensional energy poverty patterns around industrial crop projects in Ghana: Enhancing the energy poverty alleviation potential of rural development strategies. Energy Policy 2010, 137, 111123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crentsil, A.O.; Asuman, D.; Fenny, A.P. Assessing the determinants and drivers of multidimensional energy poverty in Ghana. Energy Policy 2019, 133, 110884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]