Valorisation of Cranberry Residues through Pyrolysis and Membrane Filtration for the Production of Value-Added Agricultural Products

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection and Preparation of Cranberry Residues

2.2. Elemental Analysis

2.3. Fibres Content: Hemicellulose, Cellulose, and Lignin

2.4. Pyrolysis Operating Conditions

2.5. Membrane Filtration

2.6. Determination of Filtration Parameters

2.7. Gas Chromatography (GC) Coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS)

2.8. Biostimulation Tests

2.9. Determination of Leaf Chlorophyll Rates

2.10. Bioherbicide Test

2.11. Bioherbicide Action on Conductivity

3. Results

3.1. Production of Wood Vinegar from Pyrolysis of Cranberry Residues

3.2. Membrane Processes Applied to Wood Vinegar

3.3. The quality of the Permeate and Retentate

3.4. Biostimulation Test

3.4.1. Evaluation of Germination Rates

3.4.2. Chlorophyll Content

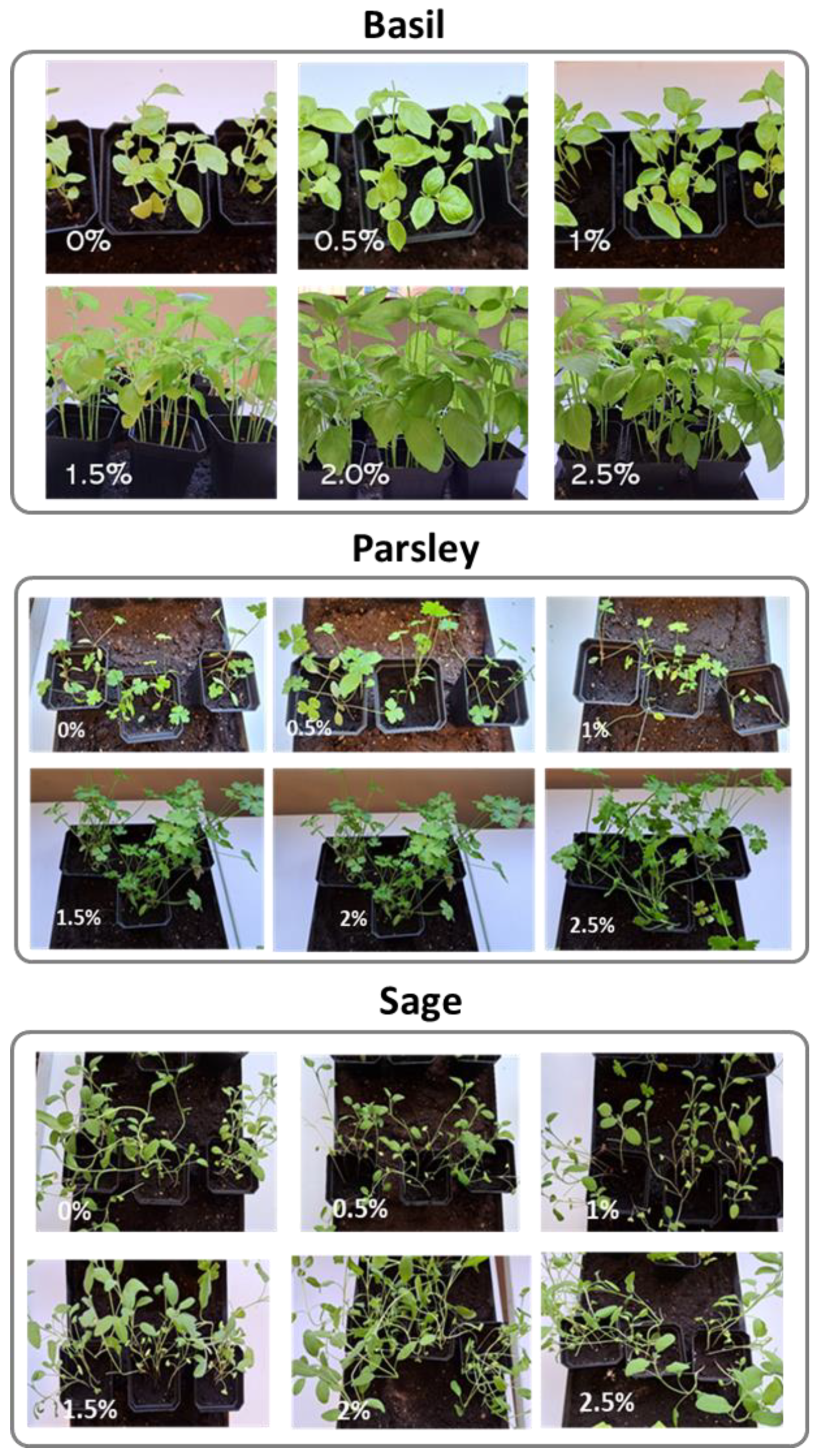

3.4.3. Plant Growth

3.5. Bioherbicide Test

3.5.1. Assessment of Permeate Phytotoxicity by Conductivity Measurement

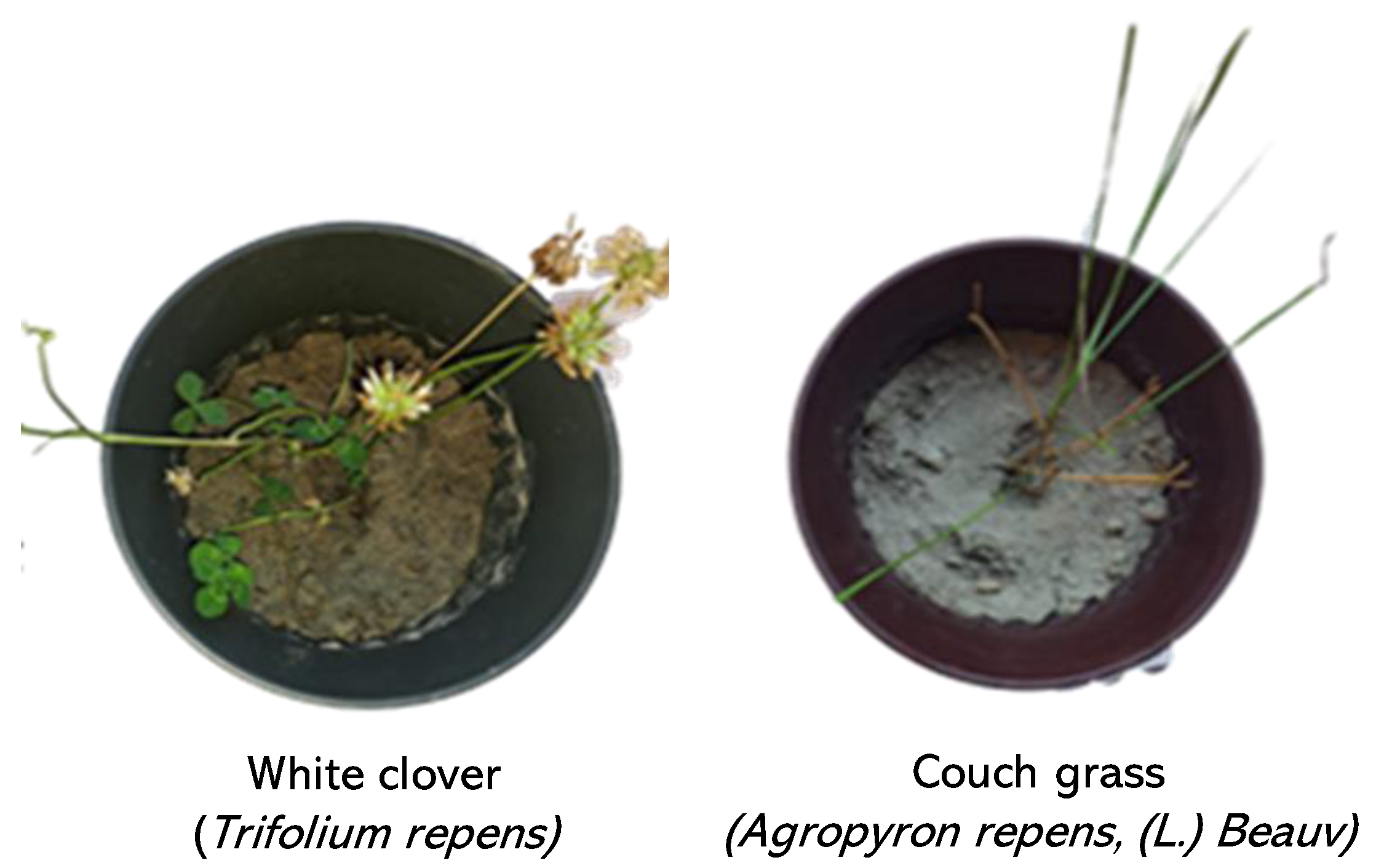

3.5.2. Assessment of Wood Vinegar Permeates Phytotoxicity on Weeds

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gratton, F. Agriculture durable au Québec: Rencontre entre Marcel Groleau et Christiane Pelchat. Vecteur Environ. 2021, 54, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Trépanier, K. Analyse Environnementale et Socio-Économique de la Production de Canneberges au Québec en Fonction des Principes de Développement Durable; Université de Sherbrooke: Québec, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Review of fast pyrolysis of biomass and product upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 38, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gholizadeh, M. Progress of the applications of bio-oil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Mourant, D.; Gunawan, R.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Lievens, C.; Li, C.-Z. Production of value-added chemicals from bio-oil via acid catalysis coupled with liquid–liquid extraction. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 9366–9370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Mahmood, N.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, M.; Wang, J.; Zheng, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wei, Q.; Xu, C.C. Preparation and characterization of bio-polyol and bio-based flexible polyurethane foams from fast pyrolysis of wheat straw. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 103, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, L.A.; McGarvey, B.D.; Briens, C.; Berruti, F.; Yeung, K.K.-C.; Scott, I.M. Insecticidal properties of pyrolysis bio-oil from greenhouse tomato residue biomass. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 112, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venderbosch, R.; Prins, W. Fast pyrolysis technology development. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2010, 4, 178–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, É.; Barnabé, S.; Godbout, S.; Zamboni, I.; Palacios, J. Production and characterization of two fractions of pyrolysis liquid from agricultural and wood residues. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2020, 12, 3333–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D. Lignin as a base material for materials applications: Chemistry, application and economics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2008, 27, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidra, A.; Németh, Á. Bio-produced acetic acid: A review. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2018, 62, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, V. Phenolic Compounds: Introduction. In Natural Products; Ramawat, K., Mérillon, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1543–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Hao, S.; Lyu, H.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J. Ion exchange separation for recovery of monosaccharides, organic acids and phenolic compounds from hydrolysates of lignocellulosic biomass. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 172, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.H.; Loh, S.K.; Chin, B.L.F.; Yiin, C.L.; How, B.S.; Cheah, K.W.; Wong, M.K.; Loy, A.C.M.; Gwee, Y.L.; Lo, S.L.Y. Fractionation and extraction of bio-oil for production of greener fuel and value-added chemicals: Recent advances and future prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 397, 125406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.; Robertson, J.; Lewis, B. Symposium: Carbohydrate methodology, metabolism, and nutritional implications in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brassard, P.; Godbout, S.; Raghavan, V.; Palacios, J.H.; Grenier, M.; Zegan, D. The production of engineered biochars in a vertical auger pyrolysis reactor for carbon sequestration. Energies 2017, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Chávez, B.J.; Godbout, S.; Raghavan, V. Effect of fractional condensation system coupled with an auger pyrolizer on bio-oil composition and properties. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 158, 105270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Yousef, H.; Steele, P. Increasing the efficiency of fast pyrolysis process through sugar yield maximization and separation from aqueous fraction bio-oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 110, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, M.; Wang, S.; Shen, J.; Rhodes, M.; Lee, W.J.; Li, C.-Z. Effects of temperature on the formation of lignin-derived oligomers during the fast pyrolysis of Mallee woody biomass. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 2022–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, G.; Okutucu, C.; Ucar, S.; Stahl, R.; Yanik, J. The slow and fast pyrolysis of cherry seed. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, T.M.; Bispo, M.D.; Cardoso, A.R.; Migliorini, M.V.; Schena, T.; de Campos, M.C.V.; Machado, M.E.; Lopez, J.A.; Krause, L.C.; Caramao, E.B. Preliminary studies of bio-oil from fast pyrolysis of coconut fibers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 6812–6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Pyrolysis of municipal plastic wastes for recovery of gasoline-range hydrocarbons. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2004, 72, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hui, J.; Qin, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, H.; Li, M. Transfer-learning-based approach for leaf chlorophyll content estimation of winter wheat from hyperspectral data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 267, 112724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, M.; Sarkar, S.; Era, F.M.; Islam, A.M.; Anwar, M.P.; Fahad, S.; Datta, R.; Islam, A.A. Drought Stress in Grain Legumes: Effects, Tolerance Mechanisms and Management. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofig, A. Effect of drought stress on some physiological traits of durum (Triticum durum Desf.) and bread (Triticum aestivum L.) wheat genotypes. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 11, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Teella, A.; Huber, G.W.; Ford, D.M. Separation of acetic acid from the aqueous fraction of fast pyrolysis bio-oils using nanofiltration and reverse osmosis membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 378, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, M.S. Effect of “osmotic” systems on germination of peas (Pisum sativum L.). Planta 1966, 71, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, B.-R.; Bradford, K.J. Quantitative models characterizing seed germination responses to abscisic acid and osmoticum. Plant Physiol. 1992, 98, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topal, S.; Kocaçalışkana, I.; Arslan, O. Herbicidal potential of catechol as an allelochemical. Z. Für Naturforschung C 2006, 61, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthandan, V.; Geetha, R.; Kumutha, K.; Renganathan, V.G.; Karthikeyan, A.; Ramalingam, J. Seed priming: A feasible strategy to enhance drought tolerance in crop plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valanciene, E.; Jonuskiene, I.; Syrpas, M.; Augustiniene, E.; Matulis, P.; Simonavicius, A.; Malys, N. Advances and prospects of phenolic acids production, biorefinery and analysis. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Meki, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Zheng, H.; You, X.; Li, F. Effect of co-application of wood vinegar and biochar on seed germination and seedling growth. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 3934–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, N.; Ghorbani Dashtaki, S.; Motaghian, H.; Iranipour, R.; Khalili Moghadam, B. Effect of Application of Biochar and Wood Vinegar on Some Chemical and Microbiological Properties of Soil under Forage Corn Cultivation. J. Water Soil Conserv. 2022, 29, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, H.; You, X.; Sun, K.; Luo, X.; Li, F. Comparative study of individual and co-application of biochar and wood vinegar on blueberry fruit yield and nutritional quality. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mine, S.; Boopathy, R. Effect of organic acids on shrimp pathogen, Vibrio harveyi. Curr. Microbiol. 2011, 63, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NF-90 | DESAL DL | BW30 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Dow Filmtec | GE Osmonics DK | Dow Filmtec |

| Materials | Active layer based on polypiperazinamide and benzentricarbonyl trichloride (Fully aromatic polyamide) | Semi-aromatic polypiperazine-amide | Polyamide |

| MWCO (Molecular Weight Cut-Off) | 200 Dalton | 150–300 Dalton | ∼100 Dalton |

| NaCl rejection (%) | 95 | <50 | 99.5% NaCl |

| Test pressure | 70 psi | 40 bars | 600 psig |

| Recommended pH range | 4–11 | 2–11 | 2–11 |

| Membrane charge (pH 7) | Negative | - | - |

| Pure water permeability | 2.49 L/m2/day kPa (at 25 °C) | 8.3 L/h.m² bar (at 30 °C) | - |

| Level | Correspondence | Qualitative Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No bioherbicid effect | The shape and colour of young leaves are normal |

| 1 | Slightly poisoned | 0 to 5% of the shape and colour of young leaves are abnormal |

| 2 | Moderately poisoned | 5 to 20% of the shape and colour of the young are abnormal |

| 3 | Severely poisoned | 20% to 50% of the shape and colour of young leaves are abnormal |

| 4 | Very severe poisoning | 50% to 75% of the shape and colour of young leaves are abnormal |

| 5 | Plant death (the plant dries up, falls and dies) | More than 75% of the shape and colour of young leaves are abnormal |

| Lignocellulosic Composition | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Extractables [%] | Cellulose [%] | Hemicelluloses [%] | Lignin [%] |

| 23.9 | 22.3 | 9.9 | 43.9 |

| Elementary composition | |||

| C [%] | H [%] | N [%] | S [%] |

| 46.8 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

| Mineral content of cranberry | |||

| Ca (%) | Mg (%) | K (%) | P (%) |

| 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.14 |

| Moisture | Temp. | Yield (% w.b.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood Vinegar | Biochar | Oily Fraction | Gas 1 | ||

| 10% | 400 °C | 17.6 | 51.3 | 10.8 | 20.3 |

| 475 °C | 31.4 | 39.9 | 12.9 | 25.7 | |

| 550 °C | 20.5 | 37.6 | 11.8 | 30.1 | |

| 20% | 400 °C | 19.9 | 44.8 | 14.6 | 20.8 |

| 475 °C | 26.7 | 35.5 | 13.2 | 24.6 | |

| 550 °C | 22.7 | 32.7 | 15.1 | 29.5 | |

| Membrane | Pressure (psi) | Retention Rate % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catechol | Acetic Acid | ||

| Desal Dl | 400 | 39.7 | 30.9 |

| 600 | 52.1 | 28.8 | |

| NF90 | 400 | 97.9 | 97.4 |

| 600 | 88.7 | 71.7 | |

| BW30 | 400 | 98.2 | 78.3 |

| 600 | 95.1 | 89.4 | |

| Permeate | Retentate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Compounds | Peak Area (%) | Organic Compounds | Peak Area (%) |

| Acetic acid | 45 | Acetic acid | 7.5 |

| Butanoic acid, 3-methyl- | 15.7 | Butanoic acid, 3-methyl- | 33 |

| Propanoic acid | 1.7 | (2S,13S)-12,13-Dihydroxy-1,4,7,10-tetraoxacyclotetradecane | 1 |

| Phenol | 1.4 | 1,2-Benzenediol, 4-methyl- | 8.4 |

| Catechol | 3 | Catechol (1,2-Benzendiol) | 36 |

| Furfural | 13 | Furfural | 4.2 |

| 2-Propanone, 1-hydroxy- | 11.5 | 2-Propanone, 1-hydroxy- | 2 |

| 2-Cyclopenten-1-one | 5 | 1,2-Benzenediol, 3-methyl- | 5.4 |

| Paromomycin | 1.5 | ||

| Weeds | Test | Conductivity before Autoclaving (µS/cm) | Conductivity after Autoclaving (µS/cm) | Lesion Percentage % | Lesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Couch grass | Control (0%) | 9.2 | 254 | 3.7 | 0 |

| White vinegar (12%) | 35.3 | 200 | 18.9 | 0 | |

| Wood vinegar permeates (12%) | 122.6 | 197 | 62.3 | ++ | |

| White clover | Control | 5 | 150 | 3.3 | 0 |

| White vinegar (12%) | 23.2 | 165 | 13.8 | + | |

| Wood vinegar permeates (12%) | 36.3 | 183 | 20.5 | ++ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bennani, G.; Ndao, A.; Konan, D.; Brassard, P.; Le Roux, É.; Godbout, S.; Adjallé, K. Valorisation of Cranberry Residues through Pyrolysis and Membrane Filtration for the Production of Value-Added Agricultural Products. Energies 2023, 16, 7774. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16237774

Bennani G, Ndao A, Konan D, Brassard P, Le Roux É, Godbout S, Adjallé K. Valorisation of Cranberry Residues through Pyrolysis and Membrane Filtration for the Production of Value-Added Agricultural Products. Energies. 2023; 16(23):7774. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16237774

Chicago/Turabian StyleBennani, Ghita, Adama Ndao, Delon Konan, Patrick Brassard, Étienne Le Roux, Stéphane Godbout, and Kokou Adjallé. 2023. "Valorisation of Cranberry Residues through Pyrolysis and Membrane Filtration for the Production of Value-Added Agricultural Products" Energies 16, no. 23: 7774. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16237774

APA StyleBennani, G., Ndao, A., Konan, D., Brassard, P., Le Roux, É., Godbout, S., & Adjallé, K. (2023). Valorisation of Cranberry Residues through Pyrolysis and Membrane Filtration for the Production of Value-Added Agricultural Products. Energies, 16(23), 7774. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16237774