Energy-Saving Scenarios of an Existing Swimming Pool with the Use of Simple In Situ Measurement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Characteristic of Swimming Pools

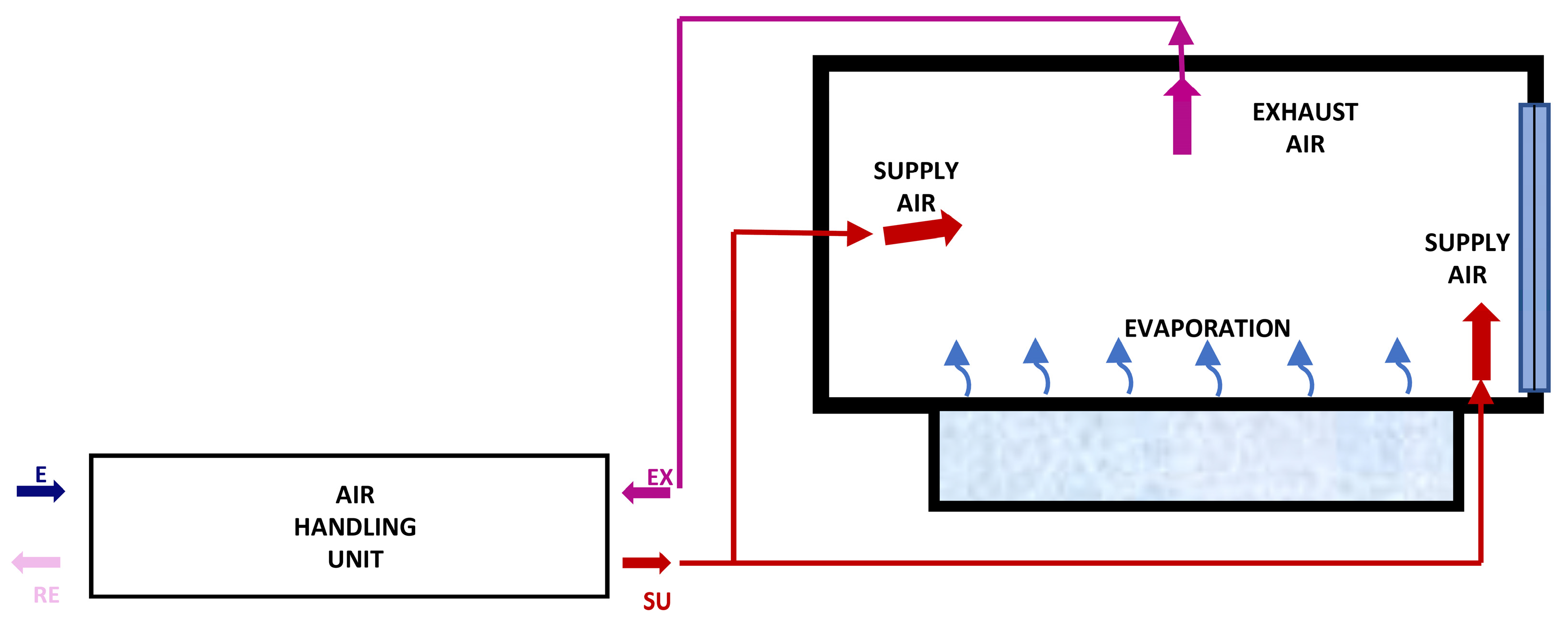

1.2. Ventilation Air Preparation

1.3. Possibilities of Reducing Energy Consumption in Indoor Swimming Pools

1.4. In Situ Measurements for Improving the Energy Performance of Swimming Pools—Research Goal

2. Materials and Methods

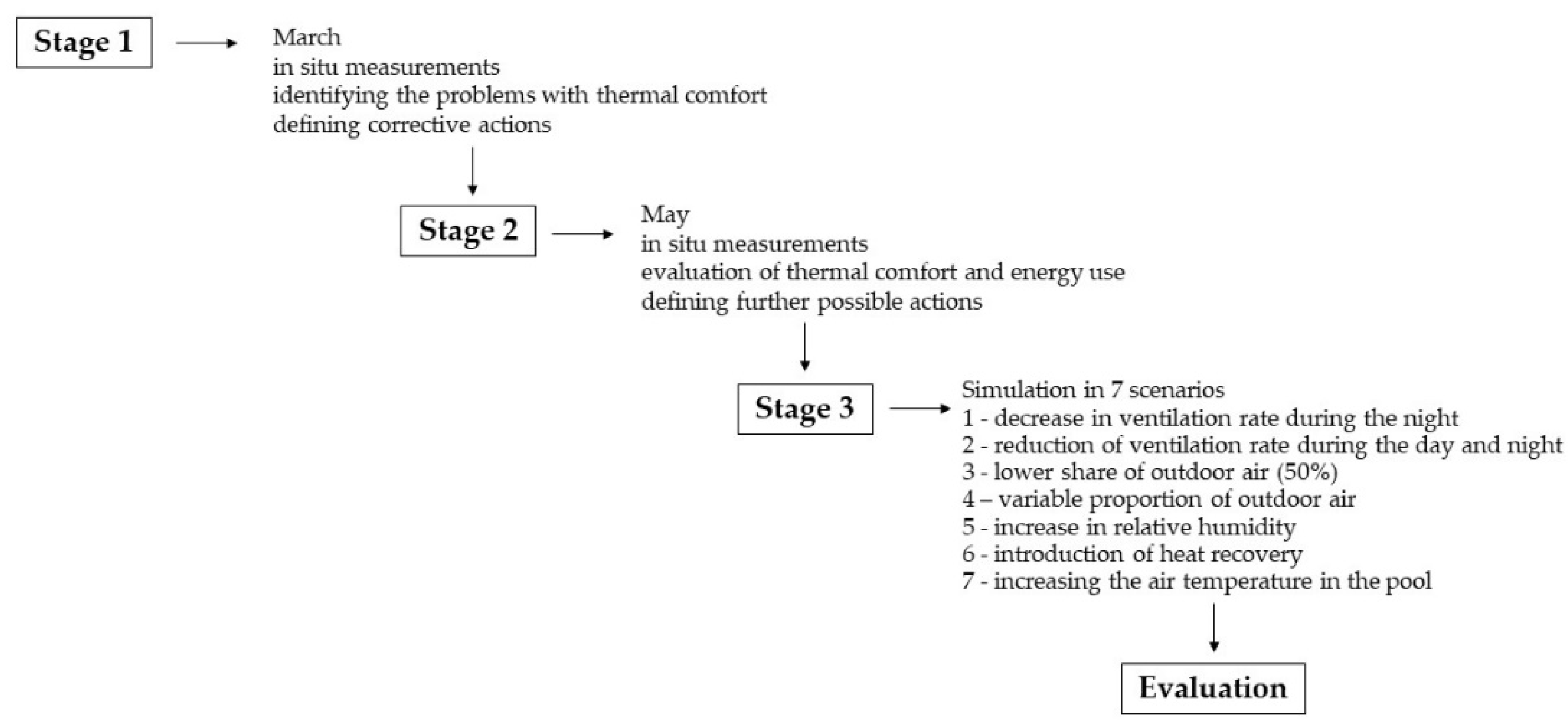

2.1. Research Plan

- (1)

- Presentation of the method of in situ measurements in a functioning swimming pool facility,

- (2)

- Stage 1—performing in situ measurements and identifying the possibility of introducing changes in the analyzed facility,

- (3)

- Stage 2—checking the effects of the introduced changes and possible further diagnostics,

- (4)

- Stage 3—proposing scenarios aimed at reducing the energy used to ensure comfortable conditions along with a quantitative assessment of effects;

- (5)

- Define the conclusions.

2.2. Research Principles

2.2.1. General Principles

2.2.2. Measurement Equipment

2.3. Measurement and Simulation Periods

2.3.1. Measurement Period for In Situ Tests

2.3.2. Measurement Period for the Simulation

2.4. Equations Used for the Analysis

2.4.1. Equations Used for the Calculations in Stage 1 and Stage 2

2.4.2. Stage 3—Scenarios

2.5. Using the Results to Improve Comfort in Pool Scenarios

2.6. A Detailed Research Plan in the Test Facility

2.7. Simulations in Seven Scenarios

- (1)

- Decrease in the ventilation rate during the night by 15%—impact on electricity consumption and amount of heat (Scenario 1),

- (2)

- Reduction in the ventilation rate during the day and night, by 33% during the day and by another 15% at night (Scenario 2),

- (3)

- Introduction of a lower share of outdoor air (50%)—Impact on heat demand (Scenario 3),

- (4)

- Introducing a variable proportion of outdoor air to ensure the regulation of the moisture content in the supply air, which will result in constant relative humidity in the pool (Scenario 4),

- (5)

- Increase in relative humidity in the swimming pool and a variable proportion of outside air (Scenario 5)

- (6)

- Induction of heat recovery in the treatment of ventilation air, with assumed heat recovery at a relatively low level (50%)—Impact on the demand for heat to heat the air (Scenario 6),

- (7)

- Increasing the air temperature in the pool—Impact on the amount of heat supplied to the heater (Scenario 7).

2.8. Simulations in Seven Scenarios and Assumptions

2.8.1. Scenario 1

2.8.2. Scenario 2

2.8.3. Scenario 3

2.8.4. Scenario 4

2.8.5. Scenario 5

2.8.6. Scenario 6

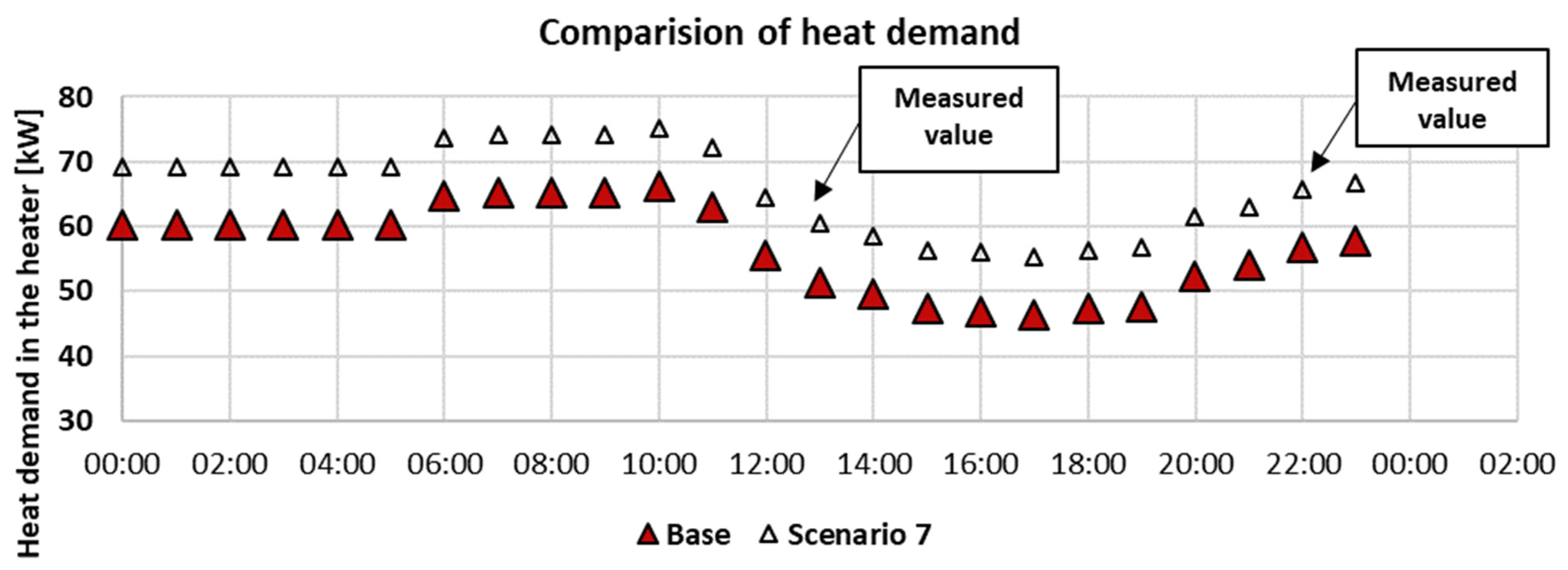

2.8.7. Scenario 7

3. Tested Swimming Pool Facility

4. Results

4.1. Stage 1—Results

- (1)

- The obtained results of short measurements for day and night correspond to the values measured in the period preceding the tests. This suggests that such measured conditions prevail in the analyzed facility.

- (2)

- The air temperature in the pool is too low. To ensure appropriate thermal comfort, the air temperature should be higher than the water temperature. In the current state, users may experience thermal discomfort.

- (3)

- The relative humidity of the air in the pool is at an acceptable level. However, it could be higher. The lower the relative humidity, the faster the evaporation of water from the surface of the bodies of people leaving the pool. This can cause thermal discomfort.

- (4)

- The amount of evaporation is lower in the absence of users, i.e., during the night. Therefore, the ventilation rate can be reduced during the night. The relative humidity measured at night is significantly lower than that during the day, which is associated with the use of a constant ventilation rate. There is no risk that the air flow reduction will result in exceeding the relative humidity limit.

- (1)

- Increase the temperature of the indoor air, which is the value set in the ventilation system in the tested facility.

- (2)

- Increase the relative humidity of the air in the pool; because it is not possible to set a higher relative humidity, this will be accomplished indirectly by reducing the ventilation rate. Reducing the air rate will cause the relative humidity to increase with the same use of the pool (the same moisture gains) and with a reduced flow of supply air.

4.2. Stage 2—Results

- (1)

- The air temperature in the pool increased by 1.7 °C during the day and by about 1.1 °C at night. However, the air temperature in the pool is still low and reaches 26 °C, with the water temperature equal to 28 °C. Users may still experience thermal discomfort.

- (2)

- The ventilation rate was reduced by more than 2000 m3/h. Ventilation continues to operate at a constant but reduced air flow throughout the day and night. The controller in the air handling unit does not allow for entering the work schedule in day and night mode. Reducing the air flow reduces the electrical consumption of the fan drive. The power consumption of the air handling unit was 800 W/h. If the reduced air flow was maintained throughout the year, the electricity consumption would be reduced by 7000 kWh, which could bring significant savings in the electricity bills.

- (3)

- The reduction in the ventilation rate along with the increase in air temperature in the swimming pool did not cause changes in the evaporation rate. A slightly higher amount of moisture gain was measured during the night. During the period of use, the amount of evaporation was slightly lower. However, it could have been influenced by the number of swimmers, which was one person less in Stage 2.

- (4)

- At the same time, the relative humidity in the swimming pool decreased during the day and at night. The purpose of lowering the air flow was to obtain a higher relative humidity. An increase in the relative humidity could not be achieved, which may cause thermal discomfort.

- (5)

- Due to the measurement inside the air handling unit, it was determined that the share of outside air in the supply air flows is 70%. The air handling unit did not change during the testing period, so the share of outdoor air in March was also 70%. As a rule, in the colder period, the proportion of outside air can be lower by up to 30%, especially when the outside air contains little moisture. Therefore, it is assumed that savings in heat consumption can be achieved by reducing the share of outdoor air. It may also be the reason for the low relative humidity in the pool. This is because there is little possibility of controlling the moisture content in the supply air if the external air flow rate is set constant.

- (6)

- The cross-flow exchanger for heat recovery was found to not work. Calculated on the basis of the value of moisture content in the exhaust air, the outside air, and the air behind the mixing chamber, the share of outside air allows for concluding that the air in the AHU flows through the bypass. The use of bypass in winter allows the exchanger to be protected against frosting. Due to the lack of the automatic control of the AHU, the adjustment of the bypass damper was not taken into account during service. Including a heat exchanger in the operation of the AHU would allow for significant savings.

4.3. Simulation Results—Thermal Comfort

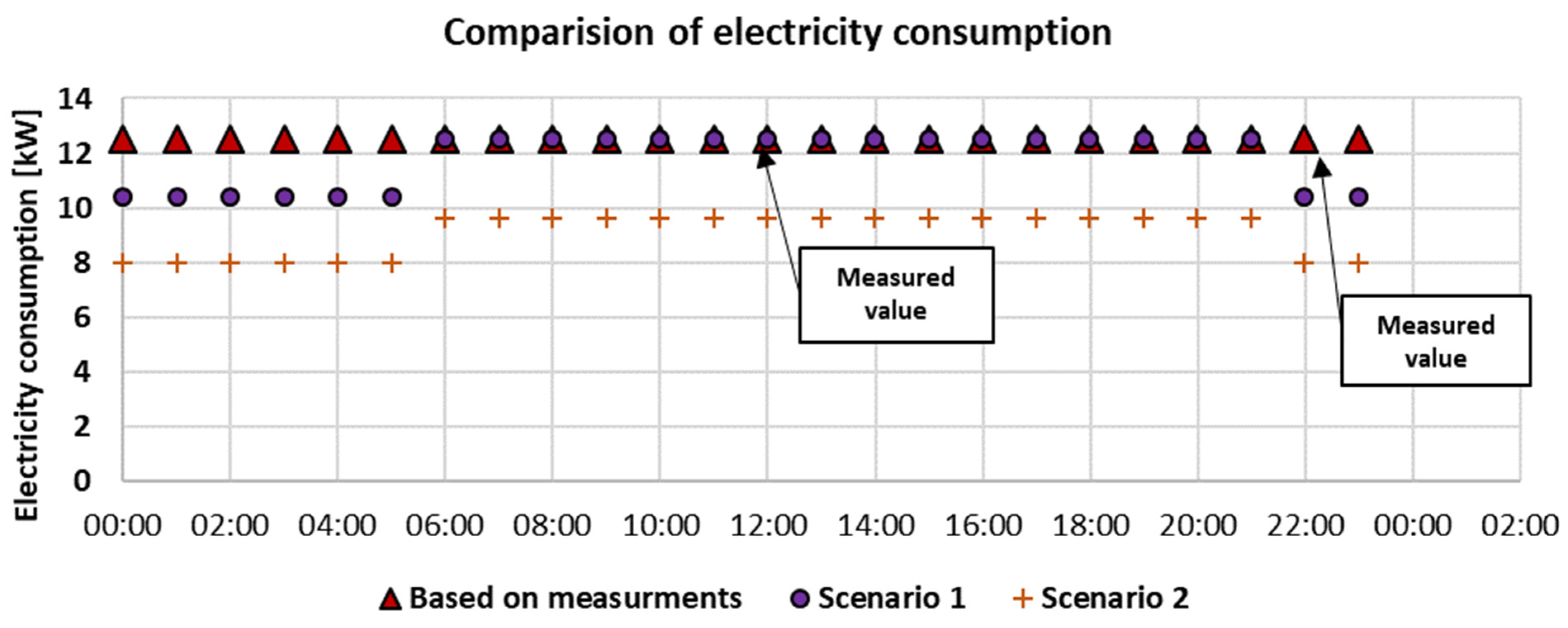

4.4. Simulation Results—Electricity Consumption

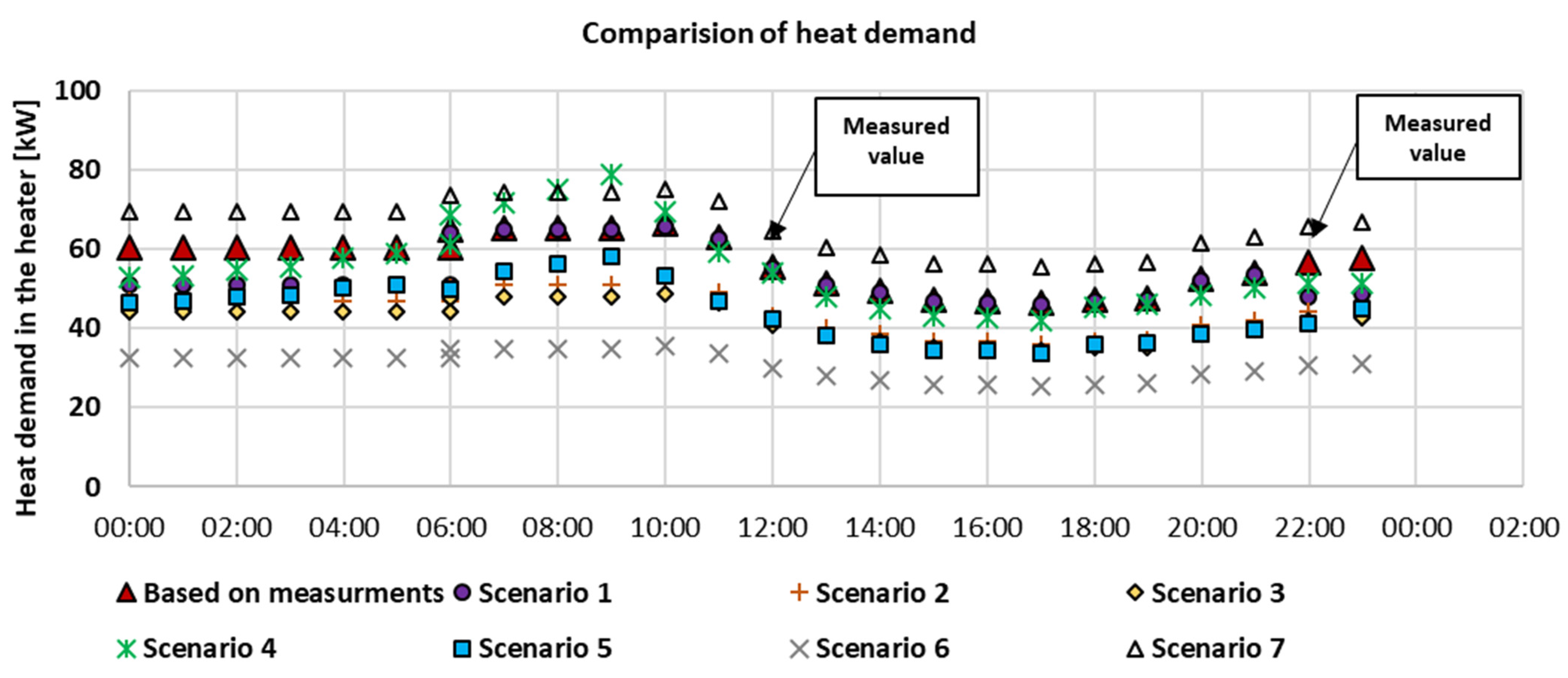

4.5. Simulation Results—Heat Demand

4.6. Summary of the Results

5. Limitations and Further Research

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Further Research

6. Conclusions and Summary

- (1)

- Conducting in situ measurements, even in a very limited scope, allows for determining actions that can lead to an improvement in thermal comfort in a room while reducing energy consumption.

- (2)

- Due to the reduction in the ventilation rate during the night, the electricity consumption was reduced. Assuming a reduction in the ventilation rate of 33% during the day and 45% at night compared to the base variant, 27% of the electric energy needed for the operation of ventilation was saved per year.

- (3)

- The use of the scheduling of the operation of the air handling unit, even in such a limited scope as variable performance during the day and night, can bring significant money savings, which is very valuable nowadays.

- (4)

- Due to the reduced evaporation from the pool during the night, associated with the absence of disturbances of the water, it is possible to reduce the ventilation rate at night in all swimming pool facilities.

- (5)

- Conducting more advanced in situ measurements allows for identifying faults in the controller settings. As a result of the measurements, it was established that air in the analyzed air handling unit does not flow through the heat exchanger but through a bypass. The introduction of an exchanger for heat recovery into air treatment by moving the throttle in the air handling unit would make it possible to achieve savings in the amount of heat at the level of 46% compared to the base situation.

- (6)

- The use of a variable proportion of outside air allows us to ensure comfortable relative humidity in the swimming pool room. At the same time, the use of a smaller share of outside air in winter allows for savings in the amount of heat supplied to the day AHU by 22%. Due to this, you can reduce costs without compromising thermal comfort in the room.

- (7)

- Increasing the temperature of the air in the swimming pool to a level that guarantees comfortable conditions is associated with an increase in the demand for heat in the analyzed facility by 26%.

Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chase, N.L.; Sui, X.; Blair, S.N. Comparison of the Health Aspects of Swimming With Other Types of Physical Activity and Sedentary Lifestyle Habits. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2008, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, L.; Chen, X.; She, Q.; Cao, G.; Liu, Y.; Chang, V.W.C.; Tang, C.Y. Regulation, formation, exposure, and treatment of disinfection by-products (DBPs) in swimming pool waters: A critical review. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyczarska-Kokot, J.; Lempart-Rapacewicz, A.; Dudziak, M.; Łaskawiec, E. Impact of swimming pool water treatment system factors on the content of selected disinfection by-products. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, K.; Piotrowska, A. Disinfection By-Products in Swimming Pool Water and Possibilities of Limiting Their Impact on Health of Swimmers. Geomat. Environ. Eng. 2019, 13, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyczarska-Kokot, J.; Lempart-Rapacewicz, A.; Dudziak, M. Analysis of Free and Combined Chlorine Concentrations in Swimming Pool Water and an Attempt to Determine a Reliable Water Sampling Point. Water 2020, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weng, S.; Sun, P.; Ben, W.; Huang, C.H.; Lee, L.T.; Blatchley, E.R., III. The Presence of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Swimming Pools. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2014, 1, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempart, A.; Kudlek, E.; Dudziak, M. Determination of Micropollutants in Water Samples from Swimming Pool Systems. Water 2018, 8, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lempart, A.; Kudlek, E.; Lempart, M.; Dudziak, M. The Presence of Compounds from the Personal Care Products Group in Swimming Pool Water. J. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lempart, A.; Kudlek, E.; Dudziak, M. Concentration profiles of Personal Care Products in swimming pools. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 44, 00095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Natnael, T. Health-related behaviors and associated factors among swimming pool users in Kombolcha Town, Northeastern Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 985335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, K.; Pobudkowska, A. Pilot Test on Pre-Swim Hygiene as a Factor Limiting Trihalomethane Precursors in Pool Water by Reducing Organic Matter in an Operational Facility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuten, M.G.A.; Schets, F.M.; Schijven, J.F.; Verberk, J.Q.J.C.; Van Dijk, J.C. Definition and quantification of initial anthropogenic pollutant release in swimming pools. Water Res. 2012, 46, 3682–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.; Robillard, P.; Loeffler, P.; Sekercioglu, F. Determinants of bather hygiene in public swimming pools: A mixed-methods analysis of online discussion comments. J. Water Health 2022, 20, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, A.; Heacock, H. The evaluation of factors affecting the pre-swim shower behaviors of pool patrons. BCIT Environ. Public Health J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wu, J.Y.; Wang, R.Z.; Xu, Y.X. Analysis of indoor environmental conditions and heat pump energy supply systems in indoor swimming pools. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeźnik, I. Study on water evaporation rate from indoor swimming pools. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 22, 00150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asdrubali, F. A scale model to evaluate water evaporation from indoor swimming pools. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, S.A.R.; Hoshmand, S.M.; Foadaddini, A.; Ebrahimi Naghani, P. Modeling mutual effects of evaporation, thermal sensation and concentration of chlorine contaminant in an indoor swimming pool. Modares Mech. Eng. 2016, 16, 179–188. Available online: https://mme.modares.ac.ir/article-15-10822-en.html (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Ratajczak, K.; Szczechowiak, E. Energy consumption decreasing strategy for indoor swimming pools—Decentralized Ventilation system with a heat pump. Energy Build. 2020, 206, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, B.; Vézina, L.; Gauvin, D.; Leroux, P. Investigation of Air Quality Problems in an Indoor Swimming Pool: A Case Study. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2015, 59, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lebon, M.; Fellouah, H.; Galanis, N.; Limane, A.; Guerfala, N. Numerical analysis and field measurements of the airflow patterns and thermal comfort in an indoor swimming pool: A case study. Energy Effic. 2017, 10, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuman, P.; Kaczmarczyk, J. Numerical Analysis of the Energy Consumption of Ventilation Processes in the School Swimming Pool. Energies 2021, 14, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, K.; Szczechowiak, E. The Use of a Heat Pump in a Ventilation Unit as an Economical and Ecological Source of Heat for the Ventilation System of an Indoor Swimming Pool Facility. Energies 2020, 13, 6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Nord, N.; Huang, G.; Li, X. Swimming pool heating technology: A state-of-the-art review. Build. Simul. 2021, 14, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, K.; Bandurski, K.; Płóciennik, A. Incorporating an atrium as a HAVC element for energy consumption reduction and thermal comfort improvement in a Polish climate. Energy Build. 2022, 277, 112592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinacka, J.; Ratajczak, K. Analysis of selected input data impact on energy demand in office building—Case study. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 222, 01015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amanowicz, Ł.; Ratajczak, K.; Dudkiewicz, E. Recent Advancements in Ventilation Systems Used to Decrease Energy Consumption in Buildings—Literature Review. Energies 2023, 16, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, L.; Dahl, J. Use of an open absorption heat-pump for energy conservation in a public swimming-pool. Appl. Energy 1994, 49, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarin, R.M.; Longo, G.A. Comparison of heat recovery systems in public indoor swimming pools. Appl. Therm. Eng. 1996, 16, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-S.; Kung, C.-K. Optimization of heat pump system in indoor swimming pool using particle swarm algorithm. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietkun-Greber, I.; Suszanowicz, D. The consequences of the inappropriate use of ventilation systems operating in indoor swimming pool conditions—Analysis. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 45, 00064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amanowicz, Ł.; Wojtkowiak, J. Comparison of Single- and Multipipe Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers in Terms of Energy Gains and Electricity Consumption: A Case Study for the Temperate Climate of Central Europe. Energies 2021, 14, 8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A. Comparison of swimming pools alternative passive and active heating systems based on renewable energy sources in Southern Europe. Energy 2015, 81, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Figaj, R.D.; Vanoli, L. Energy and Economic Analysis of Energy Savings Measures in a Swimming Pool Centre by Means of Dynamic Simulations. Energies 2018, 11, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, Z.; Liang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Jokisalo, J.; Kosonen, R. Heating energy-saving potentials in HVAC system of swimming halls: A review. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.T.; Bai, Y.; Fong, K.F.; Lin, Z. Analysis of a solar assisted heat pump system for indoor swimming pool water and space heating. Appl. Energy 2012, 100, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.M.; Jorge, H.M.; Quintela, D.A. An approach to optimised control of HVAC systems in indoor swimming pools. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2016, 35, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, R.; Aliasghary, M.; Mokarram, M. Design and fabrication of an intelligent management and control system to optimize energy consumption in indoor swimming pools. Energy Effic. 2021, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, G.M.; Arnesano, M. Measuring overall thermal comfort to balance energy use in sports facilities. Measurement 2014, 55, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Marín, J.P.; Vera García, F.; García Cascales, J.R. Use of a predictive control to improve the energy efficiency in indoor swimming pools using solar thermal energy. Sol. Energy 2019, 179, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Marín, J.P.; Garcia-Cascales, J.R. Dynamic simulation model and empirical validation for estimating thermal energy demand in indoor swimming pools. Energy Effic. 2020, 13, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, P.; Jamei, E. Thermal comfort of multiple user groups in indoor aquatic centres. Energy Build. 2015, 105, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowiak, J.; Amanowicz, Ł.; Mróz, T. A new type of cooling ceiling panel with corrugated surface—Experimental investigation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 7275–7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowiak, J.; Amanowicz, Ł. Effect of surface corrugation on cooling capacity of ceiling panel. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2020, 19, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinacka, J.; Szczechowiak, E. An Experimental Study of a Thermally Activated Ceiling Containing Phase Change Material for Different Cooling Load Profiles. Energies 2021, 14, 7363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trianti-Stourna, E.; Spyropoulou, K.; Theofylaktos, C.; Droutsa, K.; Balaras, C.A.; Santamouris, M.; Asimakopoulos, D.N.; Asimakopoulos, D.; Papanikolaou, N. Energy conservation strategies for sports centers: Part B. Swimming pools. Energy Build. 1998, 27, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, M.F.; Felgueiras, F.; Mourão, Z.; Fernandes, E.O. Assessment of the air quality in 20 public indoor swimming pools located in the Northern Region of Portugal. Environ. Int. 2019, 133, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczechowiak, E. Analityczne obliczanie parametrów powietrza wilgotnego. Chłodnictwo 1985, 8, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi, M.Z.; Blatchley, E.R., III. Seasonal dynamics of water and air chemistry in an indoor chlorinated swimming pool. Water Res. 2015, 68, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.C.; Weaver, W.A.; Zare Afifi, M.; Blatchley, T.N.; Cramer, J.S.; Chen, J.; Blatchley, E.R., III. Dynamics of gas-phase trichloramine (NCl3) in chlorinated, indoor swimming pool facilities. Indoor Air 2011, 21, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, C.; Wunderlich, H.G.; Heinze, R.; Frimmel, F.H.; Zwiener, C.; Grummt, T. Application of an optimized system for the well-defined exposure of human lung cells to trichloramine and indoor pool air. J. Water Health 2011, 9, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Proulx, H.; Hallé, S. A numerical study of the impacts of outdoor air intake and air changes per hour on the trichloramine concentrations in a swimming pool enclosure. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 957973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichowicz, R.; Sabiniak, H.; Wielgosińsk, G. The Influence of a Ventilation on the Level of Carbon Dioxide in a Classroom at a Higher University/Wpływ Wentylacji Na Poziom Ditlenku Węgla W Pomieszczeniu Uczelni Wyższej. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2015, 22, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lisik, K.; Cichowicz, R. Microbiological Risk in Rooms with Mechanical Ventilation. J. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 23, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature | Indoor Air | Pool Water |

|---|---|---|

| Regular pool | 30 °C | 28 °C |

| Relative humidity | 50–60% | − |

| Measurements | Measurement Period | Results | Evaluation | Conclusions | Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 March | Minimum—measurements only in the swimming pool | 1 h during the day (12:00) 1 h after closing (22:00) | Averaging values | Parameters recommended as comfortable according to Table 1 | Evaluation of the possibility of improving the measured state | Definition of specific corrective actions |

| Measured parameters | Supplied air—tSU, RHSU/Exhaust air—tEX, RHEX/External air—tE, RHE/Air stream/Number of swimmers/Electricity consumption of air handling unit | |||||

| Calculated parameters | The power of the heater (Equation (6)) | |||||

| Implementation of corrective actions based on the recommendations from Stage 1 Checking after a longer period of the operation of the facility in new conditions | ||||||

| Stage 2 May | Minimum: measurements only in the swimming pool. If possible, supplement the measurements with the values measured in the air handling unit | 1 h during the day (12:00) 1 h after closing (22:00) | Averaging values | Parameters recommended as comfortable according to Table 1 and the assessment of the improvement of parameters according to the recommendations | Evaluation of the achieved improvement in terms of comfort and energy consumption. Definition of further possible actions—definition of scenarios | Perform a simulation in order to select the most advantageous operation for the analyzed facility (Section 4.3) |

| Measured parameters | Supplied air—tSU, RHSU/Exhaust air—tEX, RHEX/External air—tE, RHE/Air stream/Number of swimmers/Electricity consumption of air handling unit Additionally: inside the AHU after mixing—tMIX, RHMIX | |||||

| Calculated parameters | The power of the heater (Equation (6)) | |||||

| Stage 3 Simulations | Calculations of parameters in the air handling unit | 1 day | Average values for each hour, labeling the values measured in Step 2 for the two selected hours | Based on the difference in energy consumption from baseline and thermal comfort rating | Evaluation of the results for each scenario and selection of the solution for which the energy consumption will be the lowest | Further recommendations for conclusions |

| Conclusion | ||||||

| Characteristics of the Changes in Parameters | Baseline (From the Results of Stage 2) | Scenario | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| Air stream daytime | VSU,DAY [m3/h] | 13,400 | 13,400 | 10,900 | 13,400 | 13,400 | 13,400 | 13,400 | 13,400 |

| Air stream nighttime | VSU,NIGHT [m3/h] | 13,400 | 11,400 | 8900 | 13,400 | 13,400 | 13,400 | 13,400 | 13,400 |

| External air share | αEX [%] | 70 | 70 | 70 | 50 | Variable | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Relative humidity | RH [%] | ≈45% | ≈45% | ≈55% | ≈55% | ≈45% | 55% | ≈50% | ≈45% |

| Supply air temperature | tSU [°C] | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 30 |

| Heat exchange efficiency | η [%] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| Characteristic | V = 13,400 m3/h αEX = 70% RH = 40% η = 0% tSU = 27 °C | VSU,NIGHT = 11,400 m3/h (−15%) | V SU,DAY = 10,900 m3/h (−33%) V SU,NIGHT = 8900 m3/h (−42%) | αEX = 50% (−20%) | αEX = variable | RH = 55% (+15%) | η = 50% | tSU = 30 °C (+3 °C) | |

| Hour | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Heat Demand Equation (6) | Hour | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Heat Demand Equation (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tEX | RHEX | xEX | QH,0 | tEX | RHEX | xEX | QH,0 | ||

| [°C] | [%] | [kg/kg] | [kW/h] | [°C] | [%] | [kg/kg] | [kW/h] | ||

| Daytime | Nighttime | ||||||||

| 06:00 | 7 | 78 | 0.0048 | 64.7 | 22:00 | 9.5 | 49 | 0.00359 | 56.8 |

| 07:00 | 6.8 | 78 | 0.00476 | 65.3 | 23:00 | 9.2 | 50 | 0.00359 | 57.7 |

| 08:00 | 6.8 | 82 | 0.00501 | 65.3 | 00:00 | 8.4 | 51 | 0.00347 | 60.2 |

| 09:00 | 6.8 | 86 | 0.00526 | 65.3 | 01:00 | 8.4 | 52 | 0.00354 | 60.2 |

| 10:00 | 6.5 | 75 | 0.00449 | 66.2 | 02:00 | 8.4 | 55 | 0.00374 | 60.2 |

| 11:00 | 7.5 | 60 | 0.00384 | 63.1 | 03:00 | 8.4 | 56 | 0.00381 | 60.2 |

| 12:00 | 9.9 | 54 | 0.00407 | 55.58 | 04:00 | 8.4 | 60 | 0.00408 | 60.2 |

| 13:00 | 11.2 | 46 | 0.00378 | 51.4 | 05:00 | 8.4 | 62 | 0.00422 | 60.2 |

| 14:00 | 11.8 | 42 | 0.00359 | 49.5 | 06:00 | 8.4 | 65 | 0.00443 | 60.2 |

| 15:00 | 12.5 | 40 | 0.00358 | 47.3 | |||||

| 16:00 | 12.6 | 40 | 0.0036 | 46.9 | |||||

| 17:00 | 12.8 | 39 | 0.00356 | 46.3 | |||||

| 18:00 | 12.5 | 44 | 0.00394 | 47.3 | |||||

| 19:00 | 12.4 | 45 | 0.004 | 47.6 | |||||

| 20:00 | 10.9 | 46 | 0.0037 | 52.3 | |||||

| 21:00 | 10.4 | 48 | 0.00374 | 53.9 | |||||

| Heat demand 1424 kWh/day | |||||||||

| Analyzed Point | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Share in the Air Stream | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Air (E) | Table 4 | Table 4 | Table 4 | α = 70% | − |

| Exhaust Air (EX) | 26 °C | Equation (12) | Equation (11) | (1 − α) = 30% | Evaporation during the day 64.0 kg/h Evaporation at night 53.1 kg/h |

| Supply Air (SU) | 27 °C | not applicable | xSU = xMIX | not applicable | During the day 13,400 m3/h At night 11,390 m3/h |

| Air in Mixing Chamber (MIX) | Equation (10) | not applicable | Equation (9) | not applicable | − |

| Analyzed Point | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Share in the Air Stream | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Air (E) | Table 4 | Table 4 | Table 4 | α = 70% | − |

| Exhaust Air (EX) | 26 °C | Equation (12) | Equation (11) | (1 − α) = 30% | Evaporation during the day 64.0 kg/h Evaporation at night 53.1 kg/h |

| Supply Air (SU) | 27 °C | not applicable | xSU = xMIX | not applicable | During the day 10,500 m3/h At night 8920 m3/h |

| Air in Mixing Chamber (MIX) | Equation (10) | not applicable | Equation (9) | not applicable | − |

| Analyzed Point | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Share in the Air Stream | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Air (E) | Table 4 | Table 4 | Table 4 | α = 50% | − |

| Exhaust Air (EX) | 26 °C | Equation (12) | Equation (11) | (1 − α) = 50% | Evaporation during the day 64.0 kg/h Evaporation at night 53.1 kg/h |

| Supply Air (SU) | 27 °C | not applicable | xSU = xMIX | not applicable | During the day 13,400 m3/h At night 13,400 m3/h |

| Air in Mixing Chamber (MIX) | Equation (10) | not applicable | Equation (9) | not applicable | − |

| Analyzed Point | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Share in the Air Stream | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Air (E) | Table 4 | Table 4 | Table 4 | Variable, Equation (4) | − |

| Exhaust Air (EX) | 26 °C | 47% | xEX = 9.88 kg/kg | (1 − α) | Evaporation during the day 64.0 kg/h Evaporation at night 53.1 kg/h |

| Supply Air (SU) | 27 °C | not applicable | xSU = 5.92 kg/kg | not applicable | During the day 13,400 m3/h At night 13,400 m3/h |

| Air in Mixing Chamber (MIX) | Equation (10) | not applicable | xMIX = xSU | not applicable | − |

| Analyzed Point | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Share in the Air Stream | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Air (E) | Table 4 | Table 4 | Table 4 | variable, Equation (4) | − |

| Exhaust Air (EX) | 26 °C | 55% | xEX = 11.7 kg/kg | (1 − α) | Evaporation during the day 64.0 kg/h Evaporation at night 53.1 kg/h |

| Supply Air (SU) | 27 °C | not applicable | xSU = 7.7 kg/kg | not applicable | During the day 13,400 m3/h At night 13,400 m3/h |

| Air in Mixing Chamber (MIX) | Equation (10) | not applicable | xMIX = xSU | not applicable | − |

| Analyzed Point | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Share in the Air Stream | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Air (E) | Table 4 | Table 4 | Table 4 | α = 70% | − |

| Exhaust Air (EX) | 26 °C | Equation (12) | Equation (11) | (1 − α) = 30% | Evaporation during the day 64.0 kg/h Evaporation at night 53.1 kg/h |

| Heat Exchanger (EX) | Equation (7) | not applicable | xHE = xE | not applicable | Heat exchange efficiency η = 50% |

| Supply Air (SU) | 27 °C | not applicable | xSU = xMIX | not applicable | During the day 13,400 m3/h At night 13,400 m3/h |

| Air in Mixing Chamber (MIX) | Equation (10) | not applicable | Equation (9) | not applicable | − |

| Analyzed Point | Temperature | Relative Humidity | Moisture Content | Share in the Air Stream | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Air (E) | Table 4 | Table 4 | Table 4 | α = 70% | − |

| Exhaust Air (EX) | 29 °C | Equation (12) | Equation (11) | (1 − α) = 30% | Evaporation during the day 64.0 kg/h Evaporation at night 53.1 kg/h |

| Supply Air (SU) | 30 °C | not applicable | xSU = xMIX | not applicable | During the day 13,400 m3/h At night 13,400 m3/h |

| Air in Mixing Chamber (MIX) | Equation (10) | not applicable | Equation (9) | not applicable | − |

| Parameters | Daytime 12:00 | Nighttime 22:00 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature [°C] | Relative Humidity [%] | Moisture Content [kg/kg] Equation (1) | Temperature [°C] | Relative Humidity [%] | Moisture Content [kg/kg] Equation (1) | |

| Supply Air | 23.7 | 28.6 | 0.0052 | 25.6 | 24.4 | 0.0049 |

| Exhaust Air | 24.3 | 51.0 | 0.0097 | 24.4 | 43.6 | 0.0089 |

| Pool | 24.5 | 50.0 | 0.0096 | 24.6 | 46.0 | 0.0089 |

| Outdoor | 7.7 | 55.0 | 0.0036 | 4.9 | 67.0 | 0.0036 |

| Water Temperature [°C] | 28 | 28 | ||||

| Number of Swimmers | 19 | 0 | ||||

| Air Flow [m3/h] | 15,475 | 15,530 | ||||

| Δx = xSU − xEX [kg/kg] Equation (2) | 0.0045 | 0.0033 | ||||

| Evaporation [kg/h] Equation (3) | 83 | 62.1 | ||||

| Evaporation Rate [kg/h/m2] | 0.266 | 0.199 | ||||

| Parameters | Daytime 12:00 | Difference | Nighttime 22:00 | Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature [°C] | Relative Humidity [%] | Moisture Content [kg/kg] | Temperature [°C] | Relative Humidity [%] | Temperature [°C] | Relative Humidity [%] | Moisture Content [kg/kg] | Temperature [°C] | Relative Humidity [%] | |

| Supply Air | 25.9 | 28 | 0.0058 | 2.2 | 28 | 22 | 0.515 | 2.4 | ||

| Exhaust Air | 25.9 | 46.7 | 0.0098 | 1.6 | 25.9 | 41 | 0.852 | 1.5 | ||

| Pool Air | 26.2 | 43.5 | 0.00922 | 1.7 | −10 | 25.7 | 39.8 | 0.0082 | 1.1 | −5 |

| Outdoor Air | 9.9 | 55 | 0.00414 | 2.2 | 9.5 | 51 | 0.0037 | 4.6 | ||

| In AHU Mixing Chamber | 15.2 | 54.4 | 0.00582 | − | 13.8 | 53 | 0.0052 | − | ||

| Swimmers | 24 | 0 | ||||||||

| Water Temperature [°C] | 27.8 | 0.2 | 27.8 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Air Flow [m3/h] | 13,417 | −2058 | 13,312 | −2218 | ||||||

| External Air Share [%] | − | − | 70.0 | − | ||||||

| Δx [kg/kg] | 0.00398 | 0 | 0.00337 | 0 | ||||||

| Evaporation rate [kg/h] | 64.1 | −18.9 | 53 | −14 | ||||||

| Evaporation rate [kg/h/m2] | 0.205 | −0.06 | 0.17 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Scenario | Baseline | Scenario | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Characteristic | VSU = 13,400 m3/h αEX = 70% RH = 40% η = 0% tSU = 27 °C | VSU,NIGHT = 11,400 m3/h (−15%) | VSU,DAY = 10,900 m3/h (−33%) VSU,NIGHT = 8900 m3/h (−42%) | αEX = 50% (−20%) | αEX = variable | RH = 55% (+15%) | η = 50% | tSU = 30 °C (+3 °C) |

| Average relative humidity [%] | 46.6 | 46.6 | 53.9 | 56.5 | 46.6 | 56.5 | 52.4 | 46.6 |

| Average temperature [°C] | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 29 |

| Baseline | Scenario | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| VSU = 13,400 m3/h αEX = 70% RH = 40% η = 0% tSU = 27 °C | VSU,NIGHT = 11,400 m3/h (−15%) | VSU,DAY = 10,900 m3/h (−33%) VSU,NIGHT = 8900 m3/h (−42%) | αEX = 50% (−20%) | αEX = variable | RH = 55% (+15%) | η = 50% | tSU = 30 °C (+3 °C) | |

| Heat demand [kWh/day] | 1424 | 1334 | 1108 | 1049 | 1392 | 1085 | 769 | 1580 |

| Difference [%] | −6% | −22% | −26% | −2% | −24% | −46% | +16% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ratajczak, K.; Szczechowiak, E.; Pobudkowska, A. Energy-Saving Scenarios of an Existing Swimming Pool with the Use of Simple In Situ Measurement. Energies 2023, 16, 5886. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16165886

Ratajczak K, Szczechowiak E, Pobudkowska A. Energy-Saving Scenarios of an Existing Swimming Pool with the Use of Simple In Situ Measurement. Energies. 2023; 16(16):5886. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16165886

Chicago/Turabian StyleRatajczak, Katarzyna, Edward Szczechowiak, and Aneta Pobudkowska. 2023. "Energy-Saving Scenarios of an Existing Swimming Pool with the Use of Simple In Situ Measurement" Energies 16, no. 16: 5886. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16165886

APA StyleRatajczak, K., Szczechowiak, E., & Pobudkowska, A. (2023). Energy-Saving Scenarios of an Existing Swimming Pool with the Use of Simple In Situ Measurement. Energies, 16(16), 5886. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16165886