Abstract

The strategies, plans and legislation on energy market development and decarbonization in the European Union (EU) developed in recent years, such as the directives implementing the package “Clean energy for all Europeans”, aim at promoting not only renewable energy sources, but also new institutions that involve the development of local energy markets and a greater role for citizens in managing their own energy generation. At the same time, Poland remains the economy most dependent on coal and one of the largest air polluters in the EU. In order to minimize this problem and to meet the direction of energy development in the EU, Poland decided to establish, among other things, an energy cooperative. It is intended to fill the gap in the development of the civil dimension of energy on a local scale and at the same time improve efficiency in the use of the potential of renewable energy sources in rural areas. The authors of the paper seek to verify the extent to which this new institution, which is part of the idea of a local energy community, one of the driving forces for the implementation of the objectives and directions of development of “clean energy” set by the EU, has a chance to develop. The research took into account the characteristics of energy producers and consumers in rural areas, economic preferences provided for by law, relating to the functioning of an energy cooperative and the existing alternative solutions dedicated to prosumers. A dedicated mathematical model in the mixed integer programming technology was used to optimize the functioning of an energy cooperative, and more than 5000 simulations were carried out, with a typical optimization task performed as part of the research with about 50,000 variables. The conclusions and simulations make it possible to confirm the thesis that profitable energy cooperatives can be established in rural areas, with the objective of minimizing the sum of energy purchases from the distribution network and losses on the energy deposit (virtual network storage) (the energy deposit (or network deposit) should be understood as energy introduced to the grid during generation surpluses for its subsequent consumption, taking into account the discount factor).

1. Introduction

Decentralization of large-scale energy, replacing it with pro-ecological, distributed generation sources and building the civil dimension of energy [1,2], are the objectives of the energy transformation in the European Union (EU) [3,4]. EU legislation does not impose a precise formula for achieving these objectives, providing the freedom to individual member states [5,6]. Building energy self-sufficiency at local level is possible on the basis of institutions called energy communities (EC) [7]. The first of these is the energy community defined in the REDII Directive (Renewable Energy Directive II) [8], focused on a renewable energy community (REC) [9]. The second form of activity is the citizens energy community (CEC) [10], introduced by the market directive [11]. Both these concepts serve the development of locally distributed energy, have a legal personality and are characterized by voluntary and open participation [12]. Their primary purpose is to provide economic and environmental benefits at local level. The main differences between the REC and the CEC [13] are that large and medium-sized enterprises are excluded from the CEC, whereas energy generation capacity must be available in an REC (it must be from a renewable energy source—RES) and there are requirements for investment [14].

The EU direction of energy market transformation has also been reflected in Polish law, where, similarly to the community provisions, two institutions were created that introduce the civil dimension of energy. These include energy clusters [15] and energy cooperatives—the latter, being the newest [16] form of support for distributed civil energy, are the subject of consideration by the authors of this paper. The activity of an energy cooperative may be conducted in the territory of a rural or urban-rural municipality or in no more than three such municipalities directly adjacent to each other. The energy cooperative relies on:

- the generation of electricity or biogas, or heat in RES systems;

- the balancing of the demand for the auxiliaries of the energy cooperative and its members.

The provision of opportunities to build local energy communities [14,17] on the basis of cooperatives [18,19] can be very important especially in rural areas [20]—including by developing the “smart villages” concept [21,22]. This is where the greatest potential exists for the use of renewable energy sources (including biomass and biogas), including those of a waste nature that are part of the characteristics of a circular economy [23,24]. Unfortunately, although solutions concerning energy cooperatives have been in place in Poland since mid-2019, by the end of 2020 no energy cooperative had yet been established [25]. The considerations of different options for the cost-effectiveness of creating an energy cooperative as a Polish response to the development of local energy communities in the EU [26] are the core of the research presented in the paper. However, it should be noted that it is not the purpose of this paper to assess the extent to which the institution of an energy cooperative meets Poland’s obligation with respect to REC and CEC.

The main objective of our paper is to check where generation (number, type and capacity of installed sources) and consumption (energy demand) configurations the energy cooperative will be a cost-effective solution for the potential members of cooperatives. Thus an attempt will be made to answer the question of the production and consumer structure and the number of members that will be necessary for a form of self-organization such as an energy cooperative to develop. All restrictions and conditions resulting directly from the Polish law will be taken into account, and an analysis of the cost-effectiveness of establishing cooperatives in relation to the preferences that apply to individual prosumers will be analyzed. According to the authors, due, among other things, to different preferences for individual prosumers [27] and energy cooperatives (the so-called 1:0.8 or 1:0.7 discount rate for individual prosumers (this is a type of support scheme for prosumers in Poland: owners of micro-installations (capacity up to 50 kW) are allowed to exchange the surplus of energy produced under favourable conditions for gaps in energy production. The ratio is 1 to 0.8 for capacity up to 10 kW and 1 to 0.7 in the case of micro-installations between 10 and 50 kW) [28]) [29] and 1:0.6 for energy cooperatives [16]), the establishment of a cooperative will not always be economically justified. All the models of cooperatives proposed and researched in this paper, likewise data concerning energy production and consumption in households which are potential members of cooperatives, are anonymized real data from rural areas of Poland.

Our paper fills in a literature gap in the following ways. Firstly, our research, based on real data, allowed us to create several model energy cooperatives taking into account the conditions for the establishment and development of these institutions in Poland. Owing to this, the authors do not limit themselves to examining one specific example, but seek to show the most optimal model of operation of the citizens’ energy community, which includes the energy cooperative. Secondly, our paper fills a methodological gap [30], as the methodological approach presented can easily be used in relation to other distributed energy institutions (especially the various energy communities), which have been and will be established in Europe and on other continents. Thirdly, it is novel at the national level as it investigates a problem not yet explored for Poland.

The contribution of the paper to scientific literature consists in proving that the energy communities’ efficiency may be considered using optimization models in the mixed-integer programming technology, which are a basic tool for operational research applicable to decision-support processes in all areas of the economy. The paper also contributes to policy-related literature, because the economic effects of the functioning of energy communities are underestimated in decisions regarding the creation of such new institutions [30,31,32], where legal [33], administrative [34,35] and technological aspects prevail [36,37,38].

The paper is structured as follows. The second section provides the rules for the functioning of energy cooperatives and the main model assumptions arising from Polish law and those made by the authors. The next section describes the output data and their selection, as well as the mathematical optimization method used in the research process. Then the results are presented and discussed step by step. The final section presents the conclusions that have made it possible to conclude the entire research work and to present its universal character in relation to the methodology of examining the cost-effectiveness of creating institutions that are part of the idea of energy communities, which is gaining increasing recognition all over the world.

2. The Background of Energy Cooperatives

2.1. Energy Cooperatives as a Response to Renewable Energy Community (REC) and Citizens Energy Community (CEC)

As a country whose energy sector is still mainly dependent on coal [39], Poland is unlikely to meet the minimum 15% national target for renewable energy sources (RES) [40] in the final balance of energy consumption in 2020 (the European Union is committed to achieving 20% of energy from renewable sources in gross final energy consumption in 2020. All member states have individual targets to ensure that the EU plan is met. Poland has committed itself to achieving 15%. For comparison, Sweden has the highest level of commitment (49%) and Malta the lowest (10%) [41]) [42] (official EUROSTAT data will be available in 2022). One of the solutions enabling the acceleration of Poland’s green transformation is the popularization of local energy communities and the resulting decentralization of energy. In 2019, the Polish government introduced the institution of an energy cooperative in order to meet the objectives of the EU directives on the development of RES and citizens’ energy communities. Energy cooperatives are also intended to:

- increase the energy independence of rural areas;

- improve living and business conditions in rural areas, including increasing the competitiveness of the agri-food sector;

- increase the use of local renewable resources.

Rural areas make up more than 93% of Poland, with almost 40% of the country’s population. The increase in energy demand in these areas, coupled with increased consumption by agriculture, is forcing rural people to use it more efficiently and politicians to develop energy security strategies for rural areas [43]. This is possible by creating a sustainable energy policy using renewable energy sources. Rural areas are largely associated with food production and processing, where agricultural holdings are important. They should now be seen on the one hand as energy users and on the other as producers of energy or final energy components based on renewable energy sources [44], including those concentrated and developed in energy cooperatives.

The definition of an energy cooperative appeared in Polish law during the amendment of the Act on Renewable Energy Sources. Pursuant to this, an energy cooperative is one within the meaning of the provisions of the Cooperative Law [45] and the Act on Farmers’ Cooperatives [46] the object of which is to generate electricity, heat or biogas (exclusively for the auxiliaries of the energy cooperative and its members). Energy cooperatives may be established (conditions to be met cumulatively):

- in a rural or urban-rural municipality or in no more than three neighboring municipalities of this kind;

- in the area of operation of one distribution-system operator. The area of operation of an energy cooperative is to be determined on the basis of the places where the generators and consumers who are members of the cooperative are connected to the electricity distribution network or gas distribution network or district heating network;

- as part of low- and medium-voltage networks.

2.2. The Functioning and Billing Rules in an Energy Cooperative

Energy cooperatives operate on the basis of a prosumer system consisting of energy billing on the basis of “discounts”. With the energy cooperative the energy seller (a licensed seller of a given type of energy, designated by the Energy Regulatory Office (https://www.ure.gov.pl/en) in a given area) accounts only for the difference between the amount of electricity fed into the power distribution network and the amount of electricity drawn from it for the auxiliaries of the cooperative (its members) in the ratio corrected by the quantitative coefficient 1 to 0.6 (in the case of prosumers, the coefficients 1 to 0.8 or 1 to 0.7 apply in Poland, depending on the system capacity). In other words, for one MWh of energy generated by the cooperative and not used at a given moment by its members, i.e., fed into the distribution network (the network in this situation operates as a deposit (storage) for energy unused by the cooperative), 0.6 MWh (600 kWh) of energy can be drawn from the distribution network. This may happen at any time during the billing period when the cooperative’s generation sources do not cover the electricity demand generated by its members. This billing concerns electricity fed into and drawn from the distribution network by all electricity generators and consumers who are members of the energy cooperative. The same applies if heat or gas is the subject of the cooperative’s operation.

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the more the members of the cooperative “synchronize” the amount of energy generated and consumed at any given time so as not to discharge energy surpluses into the network, the greater the economic effects of the energy cooperative will be. It can be said that in such a situation the distribution network will, in a way, only “protect” the internal energy economy of the cooperative. For this reason, the authors considered that the production mix should be optimized for the pre-set demand, with the minimization of energy not drawn from the network deposit and that additionally purchased from the network, resulting from possible shortages of energy generated inside the cooperative.

As a prosumer the energy cooperative operates in the power system under a comprehensive agreement with an external energy seller. This regulates both the distribution and sale of possible energy shortages to cooperatives. For an energy seller, an energy cooperative is a single, collective final consumer subject to single billing. For internal billing of an energy cooperative between its individual members, the seller indicates the amount of energy fed into and drawn from the network by its individual members. The cooperative accounts for them in accordance with internally accepted rules. The amount of unused energy remains to be taken (compensated) within a given billing period, which is usually 12 months from the last day of the month in which the surplus occurred. The energy cooperative does not pay the following fees for the amount of electricity thus billed:

- a fee for energy billing;

- a variable distribution fee;

- costs of commercial balancing.

These costs are covered by the energy seller as part of the value of energy at its disposal, i.e., 40% of the energy fed into the distribution network by the energy cooperative. (For the amount of electricity drawn from the network storage (with a coefficient of 0.6), the energy cooperative does not pay variable fees for the distribution service and does not pay the seller the billing fees. In addition, the RES, capacity and co-generation fee is not charged and collected for the amount of electricity generated in all RES systems of the energy cooperative, and subsequently consumed by all consumers of that cooperative, including the amount of energy billed. Energy cooperatives also do not have to obtain property rights arising from certificates of origin in order to redeem them, and fulfill the obligations relating to energy efficiency and capacity fees).

2.3. Legal Conditions and Assumptions for Energy Cooperatives

The institution of an energy cooperative is subject to a number of requirements and assumptions arising directly from the legislation [16], which must be met in order for an entity to be considered an energy cooperative. According to the authors, in order to better understand the subject of the analysis and the clarity of the arguments presented in the following sections, it is necessary to specify all requirements for the establishment and functioning of energy cooperatives:

- Energy cooperatives may be established only in rural or urban-rural municipalities.

- The total capacity of the cooperative’s RES system must cover no less than 70% of its auxiliaries.

- The maximum capacity generated by the energy cooperative is not to exceed 10 MW (30 MW for heat).

- The maximum number of members is 999.

- The energy cooperative generates electricity (as well as biogas or heat) exclusively for its auxiliaries and the auxiliaries of its members.

- The cooperative discharges the surplus to the common distribution network. The billing of the provision and consumption of energy to and from the network is carried out in the system of discounts at the ratio of 1:0.6—i.e., with the possibility of recovery by the cooperative of 60% of previously produced (and unused) energy.

- Individual prosumers may benefit from discounts at the ratio of 1:0.8 or 1:0.7, depending on the capacity of their sources.

- The “external” balancing of cooperatives with the seller and the distribution system operator takes place during the annual billing period.

- The “internal” balancing of energy between the members of the cooperative is carried out within one hour. From the sum of energy taken within an hour, the sum of energy fed in at the same time is subtracted. Thus for billing purposes only the result of this calculation is regarded as energy fed into or drawn from the network (depending on the result), while the rest is treated as self-consumption, which is not subject to the system of discounts or charges.

- The internal billing model can be run for any period—e.g., from an hour to a year.

- The difference in the amount of energy fed in or drawn out in the different phases is irrelevant, as the amount of energy is added to the net amount in one hour and is thus balanced. Single-phase and three-phase systems are treated the same.

- The surplus of energy fed into the network in relation to the energy drawn out at a given moment is accumulated in the network deposit during the annual billing period. After 12 months, the stock is reduced to zero.

3. Materials and Methods (Optimization Model)

3.1. Assumptions for Creating a Sample of the Energy Cooperative for Simulation Purposes

In order to carry out the simulation and study the hypotheses, it was necessary to prepare several simulation scenarios that reflect the possible reality of energy cooperatives. Based on actual data on energy producers and consumers in rural areas in Poland, five types of energy cooperative were created for simulation. They were developed so as to reproduce different: (i) locational nature, (ii) level (scale) of electricity demand, (iii) nature of economic activity of the participants in the cooperative, (v) profile of electricity consumption of each member of the cooperative, (vi) generation potential among the members of the cooperative, (vii) level of supply voltage of the members of the cooperative and (viii) size.

The structure of energy cooperatives also takes account of formal and legal aspects resulting from the regulations in force. In particular, the location criterion for the allocation of members in up to three neighboring rural or rural-urban municipalities and low or medium voltage supply was maintained. The criterion for the selection of the generation structure by the optimizer took account at least 70% of the energy demand within the annual billing period and different types of generation.

Due to unfavorable hydrological conditions in Poland, which translate into stagnation in the construction of new hydro power plants [47], it was assumed that a maximum of one hydro power plant [48] may operate within the energy cooperative. The members of the cooperative were selected so that there was a watercourse in their municipalities that could be adapted for the construction of a small hydro power plant. A practical assumption was adopted, stating that a small hydro power plant is characterized by low capacity of between several dozen and several hundred kW. The simulation, therefore, took account of the capacity limits of a single source from 0 to 500 kW with increments of 50 kW. Discreet increments make the simulation realistic because a source with continuous capacity cannot currently be installed.

In Poland there are moderately favorable solar conditions, but the prosumer energy is practically based 100% on photovoltaic sources. The structure of photo-voltaic (PVPP) sources is currently the most popular and fastest-growing method to achieve energy self-sufficiency in Poland [49]. According to the data from the Ministry of Development, Labor and Technology [50], at the end of September 2020, there were about 357,000 micro-systems in Poland (increase of 35.5% compared to the end of the 2nd quarter of 2020 and as much as 131% compared to the end of 2019) [51]. The total PVPP capacity in the Polish power grid is about 3420 MW [52]. The dynamics of micro-systems growth is influenced by numerous aid programs (The Importance of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland’s Energy Mix) [53]. The development of photovoltaic sources is also influenced by the economic aspect and the constantly decreasing unit cost of energy generation (LCOE) [54] for this type of source. In view of the above, for the simulations it was assumed that at least 25% of energy production of the members of the cooperative is from solar energy. In addition, capacity limits for a single PVPP farm from 0 to 1000 kW with increments of 50 kW were adopted.

Rural and rural-urban areas are very often undeveloped or have low-rise buildings. These factors support the construction of low-mast wind sources with low and medium capacity. The efficiency of wind generation is about twice as high for Polish wind conditions as for photovoltaic sources, which makes this type of generation attractive in terms of efficiency and cost [55]. For analysis and simulation, the possibility of cooperative participants establishing sources with a capacity from 0 to 1000 kW with increments of 250 kW was assumed.

The development of energy cooperatives must ensure that they are at least 70% self-sufficient in energy per annum and that they have a stable daily and hourly generation profile. The achievement of these indicators is determined not only by the level of installed capacity and the efficiency of generation, but also by its stability and the resultant consumer and generation profile. Taking into account the location criterion when establishing the cooperative was also intended to take advantage of the agricultural character and potential of the regions. In this context, it was assumed that members of the cooperative can also build generation sources with a stable generation profile based on biomass and biogas. For the simulation, the capacity both of biomass and biogas sources was limited to 0 to 600 kW with increments of 200 kW. The presence of generation sources of both stochastic (PVPP, wind) and stable (biomass, biogas) generation in energy cooperatives will result in flattening of the profile and reduction in generation differences between seasons of the year or times of day.

Due to the fact that the installation of new sources involves significant costs, which are not analyzed in the model presented in the paper, the assumption was made that for the optimal balance of demand in the cooperative one member has at most two energy generation sources, which does not exclude a situation where not all members have them and are thus energy producers. The discount nature of the operation of the energy cooperative and its members means that the loss of some energy on its introduction into the distributor’s network and its subsequent consumption should be balanced by a slight increase in the installed capacity of the source. For the simulation, it was assumed that the total annual energy production of each member of the cooperative could not exceed 120% of the annual energy demand. This level ensures that each member of the cooperative is fully balanced at an individual level and allows for developing self-sufficiency at an aggregated cooperative level. The discount model is also characterized by the fact that the temporary production surplus fed into the network is continuously accumulated in the network in a follow-up manner, making it possible to use this energy and consume it during periods when the demand is not covered by the current generation.

3.2. Characteristics of Energy Cooperatives Adopted for Simulation Purposes

Energy cooperatives were established on the basis of current measurement data and profiles of consumers and generation for each type of renewable energy source. The purpose of selecting the participants of the cooperative was to reflect:

- the location character—the simulation was made for participants in two southern voivodeships (administrative divisions), Małopolskie and Śląskie, and the selection took account of different locations of municipalities within the voivodeships. The selection of two different voivodeships was also aimed at reflecting potentially different solar levels and thus the efficiency of generation.

- a different level of electricity demand—this resulted in cooperatives with demand ranging from 762 MWh/year to 9759 MWh/year. Within this criterion, participants were also selected taking account of the diversity of their individual energy demands. The cooperative included participants with negligible consumption, oscillating around one MWh/year, up to 3.5 GWh.

- the nature of participants’ business activity—the selection of participants reflected the division in Polish law according to PKD codes (Polish Classification of Activities) relevant for typical agricultural activities, i.e., crop, vegetable, cereal production, raising of poultry, pigs and cattle as well as services for the agricultural sector. The complete classification is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of each analytical scenario.

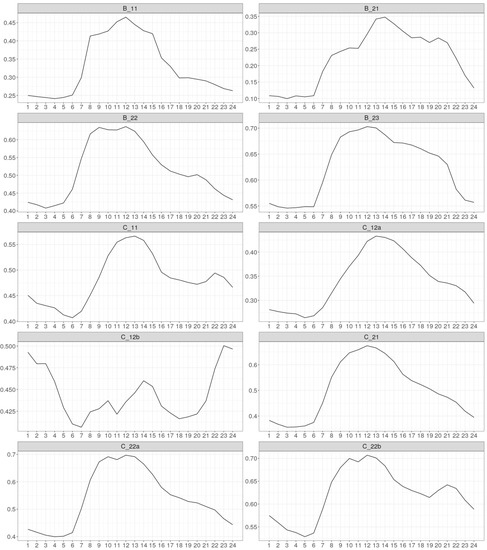

Table 1. Characteristics of each analytical scenario. - the electricity consumption profile of each member of the cooperative—the full range and variety of tariffs applicable in Poland—was taken into account, which may exist among the members of energy cooperatives. All analytical scenarios included entities belonging to one-, two- or three-zone tariffs, thus mapping the diverse nature of energy consumption. The shape of the profiles of the participants in the cooperatives is shown in Figure 1, and the belonging of differently profiled members to specific cooperatives in Table 1.

Figure 1. Average daily-hour profiles for each tariff.

Figure 1. Average daily-hour profiles for each tariff.

- the generation potential of members of the cooperatives—the selection of municipalities took account of the possibility of building renewable energy sources in each technology: wind, photovoltaic, biogas, biomass, water.

- the voltage supply of the members of the cooperatives—within each of the five cooperatives, the participants were consumers connected to the network at both medium and low voltages.

- the size—the aim was also to map cooperatives of different sizes, from 11 to 19 members.

The imposition of the above criteria made it possible to map the structures that combine all the above features in order to reproduce the real conditions for the establishment and operation of cooperatives as faithfully as possible and to examine the hypotheses formulated. Table 1 shows the characteristic and most important features of each of the cooperatives developed for the simulation.

3.3. Optimization Model

The paper’s results were obtained on the basis of data from a simulation of a dedicated mathematical model (the mathematical model has been developed and included as Supplementary Materials (see “mip_model.pdf” and “mip_model.tex” files). The mixed integer programming technique [56] was used for modeling. GLPK software was used in particular for modeling the high-level GMPL language [57] (this is open-source software). The COIN-OR/CBC software [58] (also open-source) was used to solve the individual optimization tasks. The model’s basic assumptions will be discussed below01 and fragments of the GMPL model will be illustrated.

The input data for the model comprised a two-year horizon data in hourly granulation. The calculation sessions used current data from several dozen consumers from different billing tariffs. The current two-year generation profiles of the following electricity sources were used: a small hydro power plant, a wind power plant, a photovoltaic power plant, wastewater- and biomass-based biogas plants.

Generally, the task of the optimization model was to select the optimum production mix for the pre-set demand, minimizing the energy not taken from the network deposit and purchased from the network. The energy demand, depending on the calculation scenario, was created by individual consumers or aggregated consumers within predefined cooperatives. The energy mix is to be understood as the vector of discrete factors scaling the generation profiles of the energy producers considered. The coordinates of this vector are fixed during the optimization period. The business process modeled connected the consumers with the sources on a proprietary basis (the consumer was the source owner/prosumer). Properly produced energy could be a discrete multiple of the profile adopted. Below is a relevant fragment of a mathematical model in GMPL language.

subject to def_ProductionMultiplier{e in EnergySources}:

ProductionMultiplier[e] = ProductionDiscretization[e]*ProductionDiscretizationLevel[p];

subject to def_Production{e in EnergySources, h in Hours}:

Production[h,e] = ProductionMultiplier[e]*ProductionProfile[h,e];

The ProductionMultiplier[e] is an integer variable defining a multiple of the standardized production of a specific source at hour h, i.e., ProductionProfile[h,e]. Total production of the source e is expressed by the variable Production[h,e].

The values of the total integer vector ProductionMultiplier[e] were concretized as part of the optimization task, for each energy source e. The Production[h,e] vector expressed the energy production by the source e at hour h. The energy produced could be consumed as part of own demand, or could be sent to the network to be recovered from it when needed, with a specific discount. In addition to using energy from self-consumption production and energy previously accumulated in a network deposit, the consumer could buy additional energy in the case of an absence of energy in the network deposit. The energy balance equation in the GMPL modeling language is presented below.

where EnergyDemand[h] is energy demand at hour h, BuyFromNetwork[h] is energy purchase at hour h, Production[h] is energy production at hour h, SendToNetwork[h] is energy sending at hour h, and PickUpFromNetwork[h] is energy collected at hour h.

subject to def_EnergyBalance{h in Hours}:

EnergyDemand[h]

=

BuyFromNetwork[h]

+

sum{e in EnergySources} Production[e,h]

-

SendToNetwork[h]

+

PickUpFromNetwork[h];

The model assumes that it is not possible to send energy to the operator and take energy from it or collect energy previously sent at the same hour h. The relevant model equations are as follows:

subject to constr_SingleComponentFlow{h in Hours}:

SendToNetworkIndicator[h] + BuyFromNetworklndicator[h] + PickUpFromNetworkIndicatorl[h] <= 1;

The variables SendToNetworkIndicator[h], BuyFromNetworklndicator[h], PickUpFromNetworkIndicatorl[h] are binary variables indexed by the hours of the optimization horizon, which took the value 1 for non-zero values of the corresponding current variables and the value 0 for zero flows.

The equations modeling the operation of a network deposit of energy produced by prosumers and sent to the network for later recovery are as follows:

where the set StartsOfBillingPeriods was a set of indexes containing the beginnings of billing periods—especially h = 1, i.e., the beginning of optimization, and Storage[h] is the state of the network energy deposit (storage) at hour h.

subject to def_EnergyStorage{h in Hours}:

Storage[h] =

if(h in StartsOfBillingPeriods) then

0

else

(

Storage[h-1]

-

PickUpFromNetwork[h]

+

Discount*SendToNetwork[h]

);

The optimization objective function was the sum of two components—energy taken from the network and energy produced but not consumed. Optimization was to minimize the following objective function.

minimize objective:sum{h in EndsOfBillingPeriods}

Storage[h]

+

sum{h in Hours}

BuyFromNetwork[h]

;

The set EndsOfBillingPeriods covered the last hours of billing periods.

The optimization covered a two-year horizon and the results are from the first year of optimization. This operation was aimed at avoiding the “end of the world problem”—this is manifested by non-intuitive results in the final optimization period (e.g., zero energy deposit (storage) states in final optimization intervals).

A typical optimization task carried out as part of the research covered approximately 50,000 variables, of which approximately 10,000 were total variables. The limitations were 150% of the number of variables, and the optimization task matrix comprised about 300,000 non-zero factors. Due to the volume of output data (many variables indexed by hours within a year), the analysis of the results of a single optimization session is a complex task. Without additional analytical tools, drawing conclusions from the results of thousands of optimization sessions is an impossible task. For this reason, an algorithm of regression trees [59] was used to analyze the profitability of a cooperative depending on the input parameters. Aggregates based on the correlation of weekly profiles of the cooperative members’ demand, aggregates based on the correlation of their annual demand profiles, and types and capacity of installed sources were used to describe the cooperative’s profit.

4. Results and Discussion

The following section presents the results of two series of experiments. The first examined the profitability of five specific cooperatives described in detail in Section 3. As part of the second series of experiments, which attempted to generalize the results, a total of 5000 cooperatives made up of a set of randomly selected participants were analyzed.

4.1. Hypothetical Cooperatives (Energy Cooperatives Adopted for Simulation)

Table 2 presents a summary of the most important information concerning farms that are prosumers or energy consumers and that have become members of the energy cooperatives established for the purpose of the research. The generation structure in prosumer farms was based on various renewable technologies and fuels. The average daily production level in prosumer farms varied between 13 and 100 kWh. It is worth noting that photovoltaic sources dominated the generation structure, whose production characteristics resulted in generation shortages at night and capacity surplus at noon. The variability of the daily generation level of individual members of the cooperative ranged between 0 and 1075 kWh and the average daily energy demand was between 0 and 651 kWh.

Table 2.

Information concerning farms (prosumers and energy consumers) before the establishment of the cooperative.

For each member of the five cooperatives analyzed, the optimization task was solved and the production mix, total energy consumption and energy loss within the network deposit—unused in the annual billing period—was determined. The simulation results for energy cooperatives and the aggregated results for the individual members are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Simulation results for cooperatives compared to the results obtained by aggregating partial results of the individual farms.

The analysis of the calculation results leads to several key conclusions:

- In each of the cases of energy cooperatives analyzed, there is a significant reduction in the loss on the network deposit, i.e., the energy accumulated in it is used almost entirely within the set billing period. This is particularly evident in the case of Cooperative CP3, where at the end of the year there is only 9 kWh left in the deposit. If the cooperative were not established and its members were not accounted for on an individual basis, the total stock of their deposits would be 4750 kWh. Thus a nearly 100% reduction in lost volume was achieved. The worst results allow for a reduction in energy loss, as much as by 43% from 141,363 kWh to 80,591 kWh.

- In each of the cases of energy cooperatives analyzed, there is an increase in self-consumption, i.e., the consumption of electricity by the cooperative during which the electricity production occurs. This effect is shown in Table 4. The increase in self-consumption translated into a reduction in sending of energy to the network deposit and a reduction in the volume of energy drawn from the deposit. The reduction in the volume of energy fed into the deposit by the cooperative compared to the sum of individual use of the deposit by its members ranged from 2% to 22%. It should be emphasized that the energy fed into the network deposit is drawn from it, taking account of the discount, so minimizing the volume of energy that is sent there is a desirable phenomenon.

Table 4. Energy self-consumption at the level of the energy cooperative and the individual members.

Table 4. Energy self-consumption at the level of the energy cooperative and the individual members. - In three out of five cases it was possible to parameterize the optimization model in order to achieve a reduction in the energy consumption from the network. In the case of cooperative CP2, no significant change in the amount collected was observed between the scenario of the aggregate of individual functioning of farms and the cooperative thereby established. The establishment of cooperative CP3 proved to be ineffective from this perspective, since the volume drawn from the network increased by 23%. The optimization objective set in the task, consisting in a minimization of the deposit loss and electricity consumption from the distribution network, is also very important from the perspective of aspects of economic rationality not analyzed within the framework of the paper, but extremely important. Energy consumption from the network outside the network deposit is billed each time at full purchase cost including both the electricity component as a commodity and full distribution fees relating to its delivery. The loss of electricity in the deposit after the billing period is closed is of a similar nature.

- In order to present the economic benefits of the operation of energy cooperatives, Table 5 presents the results of analyses for the example cooperative CP4 (Source data, calculation formulas and results are available as Supplementary Materials—at public source file “Analysis_CP4.xls”) taking account of the costs of energy, costs of distribution and power (capacity market) fee, broken down into: (i) costs incurred individually by farms, (ii) costs incurred by farms as prosumers, (iii) costs incurred by farms—members of cooperatives. The calculations were made based on the actual tariff rates [60]. Due to the complexity of the economic analyses, their complete picture is an area of separate analyses and publications conducted by the authors’ team.

Table 5. Economic account results for energy cooperative (CP4).

Table 5. Economic account results for energy cooperative (CP4).

The economic analysis of the selected energy cooperative (presented in Table 5) proves the profitability of its establishment and operation. The analysis does not take account of the fixed distribution and settlement fees, as these are the same at each stage. Additionally, similar to the assumptions of the model, the analysis of investment outlays was not included. Investments in generation sources and the related cost depend not only on the technological solutions used, but also on many ways of financing. It is possible, for example, to obtain subsidies or loans under national and regional support schemes, to participate in RES auctions, to participate in the feed-in tariff or feed-in premium mechanisms. The parameterization of grants and loans is conditioned by many (frequently changing) factors—the above makes it impossible to carry out a synthetic analysis and include it in the article [61].

- Self-consumption can be considered as a parameter for optimal adaptation of the generation profile to the consumption profile. In the analytical scenario before the establishment of energy cooperatives, the average self-consumption in prosumer farms ranged from 37% to 57%. The establishment of the cooperative made it possible to achieve simultaneous generation and consumption at 54–71%.

The solution to the optimal task within the production resources held by its individual members consisted in determining for each cooperative the equivalent of total energy consumption from the network and total uncollected energy within the network deposit, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Evaluation of optimization results.

It is worth noting that in the case of cooperatives CP1, CP2, CP4 and CP5, the profitability was of 7.7% to 27.5%. At −17.93% cooperative CP3 turned out to be unprofitable. This result was different to the authors’ expectations and was the starting point for designing and conducting the second series of experiments.

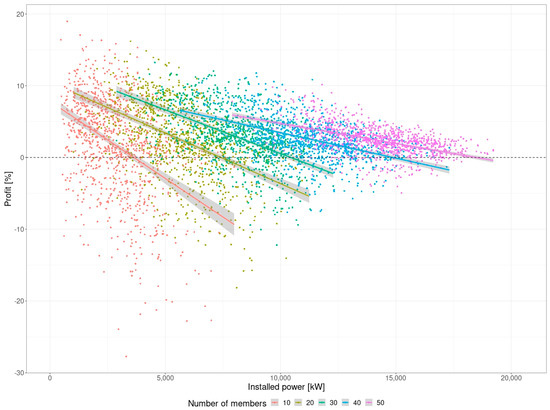

4.2. Random Cooperatives

As part of this experiment, the profitability of cooperatives selected at random from the previously prepared data of about 100 prosumers was analyzed. As in the first experiment, the individual prosumers’ data were prepared on the basis of current data. The composition of the cooperative was drawn from this set and then the optimal tasks for the individual members and the cooperative were solved. Cooperatives with 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 members were considered. The main result of the experiment is shown in Figure 2. A single point describes the profitability of the cooperative. On the horizontal axis, the total installed capacity of the cooperative and on the vertical axis, the profitability of the cooperative as a percentage value are provided. The experimental points corresponding to cooperatives with a certain number of members are marked in one color. Additionally, regression straight lines were applied to each such group of points.

Figure 2.

Visualization of the profitability of the energy cooperative by number of members.

The statistical results determining the level of profitability as percentages are presented in Table 7. The first column indicates the number of members of the cooperative. The following lines contain statistics corresponding to a cooperative with a certain number of members. The second column contains information on the minimum value of the profitability of the cooperative. This is followed by the 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 95% quantiles and the average profitability. The final columns comprise the maximum value, standard deviation and number of observations greater than zero.

Table 7.

Statistics of the profitability of the cooperative depending on the number of members.

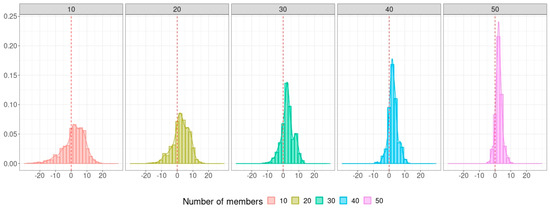

Table 7 shows that the average profitability of cooperatives with different numbers of members is similar and amounts to around 2%, but the risk of losses varies greatly. As the number of members increases, the respective profitability distributions become more concentrated—see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the profitability of the cooperative by number of members.

Experimental data were analyzed using a regression-tree algorithm in order to detect the rules governing cooperatives’ profitability. Separate trees were created for cooperatives with the same number of members. As variables describing profitability, the aggregates of correlation matrices of average weekly profiles in hourly granulation and average annual profiles in weekly granulation were assumed; information on the structure and capacity of sources installed were also used. The set of decision-making rules makes it possible to conclude that in order to maximize the profit of the cooperative:

- for small cooperatives, participants with a similar aggregated energy demand whose daily/weekly profiles are negatively correlated as much as possible should be selected;

- for larger cooperatives, aggregated energy demand may vary greatly, but the correlation of annual demand trends should be as close as possible to 1;

- diversification of generation sources should be pursued; optimal results were obtained for cooperatives which had a small hydro-power plant and a wind-power plant, but with a share in production not exceeding 30%.

It is worth noting that as the number of members increases the risk of losses (negative profitability) decreases. As the number of members increases, the minimum profitability increases and the standard deviation decreases.

5. Conclusions

The results of the research and simulations confirm that the profitability of energy cooperatives is highly dependent on the nature and supply and demand profile of its members. The analyses unequivocally confirm that the more numerous an energy cooperative in which the daily-hour profiles of its participants are maximally negatively correlated, the higher is the probability of positive profitability, understood as the minimization of the sum of energy consumption from the network and energy loss in deposit. However, positive profitability in such a scenario means lower profitability than would be the case for cooperatives with fewer members. The level of profitability is, therefore, limited, but the probability of achieving it increases.

The establishment of energy communities on the basis of energy cooperatives has not yet been practically analyzed in Poland. In the authors’ opinion, this phenomenon is caused by the necessity to carry out a dedicated and non-trivial optimization analysis each time confirming the profitability of establishing a cooperative, which is proved by this research. However, the analyses suggest that in most cases there is a solution that guarantees the creation of a profitable cooperative. This is confirmed by the results of the simulation, in which the objective for the first group of simulations was achieved in four out of five cases. The second group of calculations each time concerned 1000 simulations, for each of the five variants with 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 members of the cooperative. The results obtained—respectively 683, 718, 695, 847 and 899—also confirm this thesis.

It is worth noting that the legislative framework determining the functioning of energy cooperatives in Poland imposes relatively unfavorable boundary conditions for their development. In particular, the high discount rate of 1/0.6 is a limitation for the establishment of cooperatives. It limits their profitability in the context of the possibility of independent functioning of farms in the prosumer area and the achievement of discount rates of 1/0.7 or 1/0.8. It is also worth emphasizing that the negative impact of a high discount factor (ratio) can be limited by the physical storage of surplus energy and minimizing its flow through the operator’s network. Work is currently underway in Poland to develop and launch support schemes for the construction of energy storage facilities, which will certainly have a positive impact on the increase in the profitability of energy cooperatives. In the authors’ opinion, the legal solution in Poland and—as shown in the paper—giving measurable effects in most cases, may also be applicable and scalable in other EU countries obliged to build distributed and civil energy (corresponding to the Community framework imposed by institutions such as REC and CEC) [8,11].

In order to fully assess the profitability of cooperatives, financial aspects not covered by this paper (excepting the analysis for CP4—see Table 5) should also be taken into account, including both the amount of capital expenditure and operating costs. Market conditions, including current electricity prices and transmission and distribution fees, are also becoming crucial in this context—as well as energy storage (batteries) and e-mobility chargers. Due to their complexity, these elements will constitute an area of further exploration, research and publication by the authors’ team.

Supplementary Materials

The data presented in this study can be found here, https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/14/2/319/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.J., M.K., M.S.; methodology, M.K.; formal analysis, J.J., M.K., M.S.; investigation, J.J., M.K., M.S.; resources, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J., M.K., M.S.; writing—review and editing, J.J.; visualisation, M.K.; supervision, J.J., M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Horstink, L.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Ng, K.; Luz, G.P.; Marín-González, E.; Gährs, S.; Campos, I.; Holstenkamp, L.; Oxenaar, S.; Brown, D. Collective Renewable Energy Prosumers and the Promises of the Energy Union: Taking Stock. Energies 2020, 13, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.A.; Iles, A.; Jones, C.F. The Social Dimensions of Energy Transitions. Sci. Cult. 2013, 22, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Energy for All Europeans Package. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/topics/energy-strategy/clean-energy-all-europeans_en (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- International Renewable Energy Agency; European Commission. Renewable Energy Prospects for the European Union; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2018; ISBN 978-92-9260-007-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lüth, A.; Weibezahn, J.; Zepter, J.M. On Distributional Effects in Local Electricity Market Designs—Evidence from a German Case Study. Energies 2020, 13, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelise, C.; Ruggieri, G. Status and Evolution of the Community Energy Sector in Italy. Energies 2020, 13, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, J.S.; Nyborg, S.; Hansen, M.; Schwanitz, V.J.; Wierling, A.; Zeiss, J.P.; Delvaux, S.; Saenz, V.; Polo-Alvarez, L.; Candelise, C.; et al. Collective Action and Social Innovation in the Energy Sector: A Mobilization Model Perspective. Energies 2020, 13, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources; (OJ L 328, 21.12.2018); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Soeiro, S.; Dias, M.F. Renewable Energy Community and the European Energy Market: Main Motivations. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Position Paper: Citizens Energy Communities: Recommendations for a Successful Contribution to Decarbonisation; Eurelectric—Dépôt Légal: D/2019/12.105/13. 2019. Available online: https://www.apren.pt/contents/publicationsothers/eurelectric--citizens-energy-communities.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity and Amending Directive 2012/27/EU; (OJ L 158, 14.6.2019); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Sokołowski, M.M. Renewable and Citizen Energy Communities in the European Union: How (Not) to Regulate Community Energy in National Laws and Policies. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 2020, 38, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report: Energy Community Definitions; H2020-824424 COMPILE: Integrating Community Power in Energy Islands. 2019. Available online: https://www.compile-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/Explanatory-note-on-energy-community-definitions.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Ghiani, E.; Giordano, A.; Nieddu, A.; Rosetti, L.; Pilo, F. Planning of a Smart Local Energy Community: The Case of Berchidda Municipality (Italy). Energies 2019, 12, 4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, K. Klastry energii w Polsce—W kierunku poprawy bezpieczeństwa energetycznego. Koncepcje i uwarunkowania 2020, 4/2019, 68–78. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ustawa z Dnia 19 Lipca 2019 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw (Act of 19 July 2019 Amending the Act on Renewable Energy Sources and Certain Other Acts) (DZ.U. z 2019 r. Poz. 1524). Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20190001524 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Dóci, G.K. Renewable Energy Communities: A Comprehensive Study of Local Energy Initiatives in the Netherlands and Germany. Ph.D. Thesis, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Debor, S. The Socio-Economic Power of Renewable Energy Production Cooperatives in Germany: Results of an Empirical Assessment. Wupp. Pap. 2014, 187, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Neagu, B.-C.; Ivanov, O.; Grigoras, G.; Gavrilas, M.; Istrate, D.-M. New Market Model with Social and Commercial Tiers for Improved Prosumer Trading in Microgrids. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future of Rural Energy in Europe (FREE) Initiative. Rural Energy Matters. Report and Recommendations for Policymakers. 2016. Available online: https://www.rural-energy.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Summary-Report-Rural-Energy-Matters.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- European Commission Smart Villages and Renewable Energy Communities. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/enrd_publications/smart_villages-capacity_tools-renewable_energy_communities-v08.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Watson, J.K.R. Energy Diversification and Self-Sustainable Smart Villages. In Smart Villages in the EU and beyond; Visvizi, A., Lytras, M.D., Mudri, G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 99–109. ISBN 978-1-78769-846-8. [Google Scholar]

- Safari, M.A.M.; Masseran, N.; Jedi, A.; Mat, S.; Sopian, K.; Bin Abdul Rahim, A.; Zaharim, A. Rural Public Acceptance of Wind and Solar Energy: A Case Study from Mersing, Malaysia. Energies 2020, 13, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Baptista, R.; Henriques, R.; Nogueira, P.; Costa Pinto, L.M.; Ramísio, P.J.; Santoro, A.; Teixeira, J.C.; Vaz, E. A Green City: Impossible Dream or Necessity. In Environmental History in the Making; Joanaz de Melo, C., Vaz, E., Costa Pinto, L.M., Eds.; Environmental History; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 355–376. ISBN 978-3-319-41137-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wykaz Spółdzielni Energetycznych (List of Energy Cooperatives). Available online: http://www.kowr.gov.pl/odnawialne-zrodla-energii/spoldzielnie-energetyczne/wykaz-spoldzielni-energetycznych (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of The Council on Common Rules for the Internal Market in Electricity (Recast) COM(2016) 864 Final/2—2016/0380(COD). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52016PC0864R%2801%29 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Description of Development of Prosumer Energy Sector in Poland. Polityka Energetyczna-Energy Policy J. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Krzysztof Ignaciuk—RES LEGAL Europe Legal Sources on Renewable Energy (Promotion in Poland—Summary of Support Schemes). Available online: http://www.res-legal.eu/search-by-country/poland/tools-list/c/poland/s/res-e/t/promotion/sum/176/lpid/175/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Ustawa z Dnia 20 Lutego 2015 r. o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii (Act of February 20, 2015 on Renewable Energy Sources) (Dz.U. 2020 Poz. 261). Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20150000478 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Hoppe, T.; Coenen, F.H.J.M.; Bekendam, M.T. Renewable Energy Cooperatives as a Stimulating Factor in Household Energy Savings. Energies 2019, 12, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifakis, N.; Savvakis, N.; Daras, T.; Tsoutsos, T. Analysis of the Energy Consumption Behavior of European RES Cooperative Members. Energies 2019, 12, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grève, Z.D.; Bottieau, J.; Vangulick, D.; Wautier, A.; Dapoz, P.-D.; Arrigo, A.; Toubeau, J.-F.; Vallée, F. Machine Learning Techniques for Improving Self-Consumption in Renewable Energy Communities. Energies 2020, 13, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Pontes, L.G.; Marín-González, E.; Gährs, S.; Hall, S.; Holstenkamp, L. Regulatory challenges and opportunities for collective renewable energy prosumers in the EU. Energy Policy 2020, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowitzsch, J.; Hoicka, C.E.; van Tulder, F.J. Renewable Energy Communities under the 2019 European Clean Energy Package—Governance Model for the Energy Clusters of the Future? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 122, 109489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagemans, D.; Scholl, C.; Vasseur, V. Facilitating the Energy Transition—The Governance Role of Local Renewable Energy Cooperatives. Energies 2019, 12, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, T.; Jasiński, M.; Ropuszyńska-Surma, E.; Węglarz, M.; Kaczorowska, D.; Kostyla, P.; Leonowicz, Z.; Lis, R.; Rezmer, J.; Rojewski, W.; et al. A Case Study on Distributed Energy Resources and Energy-Storage Systems in a Virtual Power Plant Concept: Technical Aspects. Energies 2020, 13, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Mastroianni, C.; Menniti, D.; Pinnarelli, A.; Sorrentino, N. An Energy Community Implementation: The Unical Energy Cloud. Electronics 2019, 8, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Mastroianni, C.; Scarcello, L. Optimization Model for IoT-Aware Energy Exchange in Energy Communities for Residential Users. Electronics 2020, 9, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat: Renewable Energy Statistics in the EU in 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Renewable_energy_statistics (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- UE Blisko Celu OZE, Polsce Sporo Brakuje (The EU Is Close to the RES Target, Poland Is Far from Achieving It). Available online: https://www.cire.pl/item,209253,1,0,0,0,0,0,ue-blisko-celu-oze-polsce-sporo-brakuje.html (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources and Amending and Subsequently Repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC (Text with EEA Relevance) (OJ L 140, 5.6.2009). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009L0028&from=EN (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Raport “Rozwój Sektora Odnawialnych Źródeł Energii” (Report: “Development of the Renewable Energy Sector”) Najwyzsza Izba Kontroli 171/2017/P/17/020/KGP. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/kontrole/wyniki-kontroli-nik/pobierz,kgp~p_17_020_201709181219251505737165~01,typ,kk.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Piwowar, A.; Dzikuć, M. Development of Renewable Energy Sources in the Context of Threats Resulting from Low-Altitude Emissions in Rural Areas in Poland: A Review. Energies 2019, 12, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, M. Sustainable energy economy in rural areas in Poland (Zrównoważona gospodarka energetyczna na obszarach wiejskich w Polsce). Polityka Energ. 2018, T. 21, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ustawa z Dnia 16 Września 1982 r.—Prawo Spółdzielcze (Act of September 16, 1982—Cooperative Law) (Dz. U. z 2018 r. Poz. 1285 Oraz z 2019 r. Poz. 730, 1080, 1100). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19820300210 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Ustawa z Dnia 4 Października 2018 r. o Spółdzielniach Rolników (Act of October 4, 2018 on Farmers’ Cooperatives) (Dz. U. Poz. 2073). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180002073 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Energy Regulatory Office Narodowy Potencjał OZE w Liczbach—Stan na 31 Grudnia 2019 r. (The Domestic Renewable Energy Potential in Numbers as of 31 December 2019). Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/pl/oze/potencjal-krajowy-oze/5753,Moc-zainstalowana-MW.html (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Paska, J. Polish Hydropower Resources and Example of Their Utilization. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2020, 1, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Księżopolski, K.; Drygas, M.; Pronińska, K.; Nurzyńska, I. The Economic Effects of New Patterns of Energy Efficiency and Heat Sources in Rural Single-Family Houses in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerstwo Rozwoju, Pracy i Technologii Energetyka Prosumencka i Rozproszona (Prosumer and Distributed Energy). Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rozwoj-praca-technologia/energetyka-prosumencka-i-rozproszona (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Gramwzielone.pl Sp. z o. o. The Number of Prosumers in Poland Exceeds 357,000. It’s Time for Energy Storage. Available online: https://www.gramwzielone.pl/energia-sloneczna/104268/liczba-prosumentow-w-polsce-przekracza-357-tys-pora-na-magazyny-energii (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Polish Press Agency. Polish Solar Farm Has Exceeded the Level of 3400 MW of Capacity. Available online: https://www.wnp.pl/budownictwo/polska-fotowoltaika-przekroczyla-poziom-3400-mw-mocy,440020.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Marks-Bielska, R.; Bielski, S.; Pik, K.; Kurowska, K. The Importance of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland’s Energy Mix. Energies 2020, 13, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Energy Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040 r.: Wnioski z Analiz Prognostycznych dla Sektora Paliwowo—Energetycznego (Poland’s Energy Policy Until 2040: Conclusions from Prognostic Analyzes for the Fuel and Energy Sector). Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/cff9e33d-426a-4673-a92b-eb4fb0bf4a04 (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Dolega, W. Problems, Barriers and Perspectives of RES Development in Poland. In Engineering and Industry; Mavromatakis, F., Siderakis, K., Eds.; Trivent Publishing: Budapest, Hungary, 2016; Volume 3, ISBN 978-615-80340-7-4. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, H.P. Model Building in Mathematical Programming, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-44333-0. [Google Scholar]

- GLPK (GNU Linear Programming Kit). Available online: https://www.gnu.org/software/glpk/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- COIN-OR/CBC. Available online: https://projects.coin-or.org/Cbc (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Luger, G.F. Artificial Intelligence: Structures and Strategies for Complex Problem Solving, 6th ed.; Pearson Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-321-54589-3. [Google Scholar]

- TAURON Dystrybucja S.A. Taryfa dla Energii Elektrycznej na Rok 2020 (Tariff for Electricity for 2020). Available online: https://www.tauron.pl/-/media/offer-documents/firma/taryfa-msp/gze-podstawowe/taryfa_dystrybucyjna.ashx (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Wróbel, J.; Sołtysik, M.; Rogus, R. Selected Elements of the Neighborly Exchange of Energy—Profitability Evaluation of the Functional Model. Polityka Energ. Energy Policy J. 2019, 22, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).