Community Energy Groups: Can They Shield Consumers from the Risks of Using Blockchain for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading?

Abstract

1. Introduction

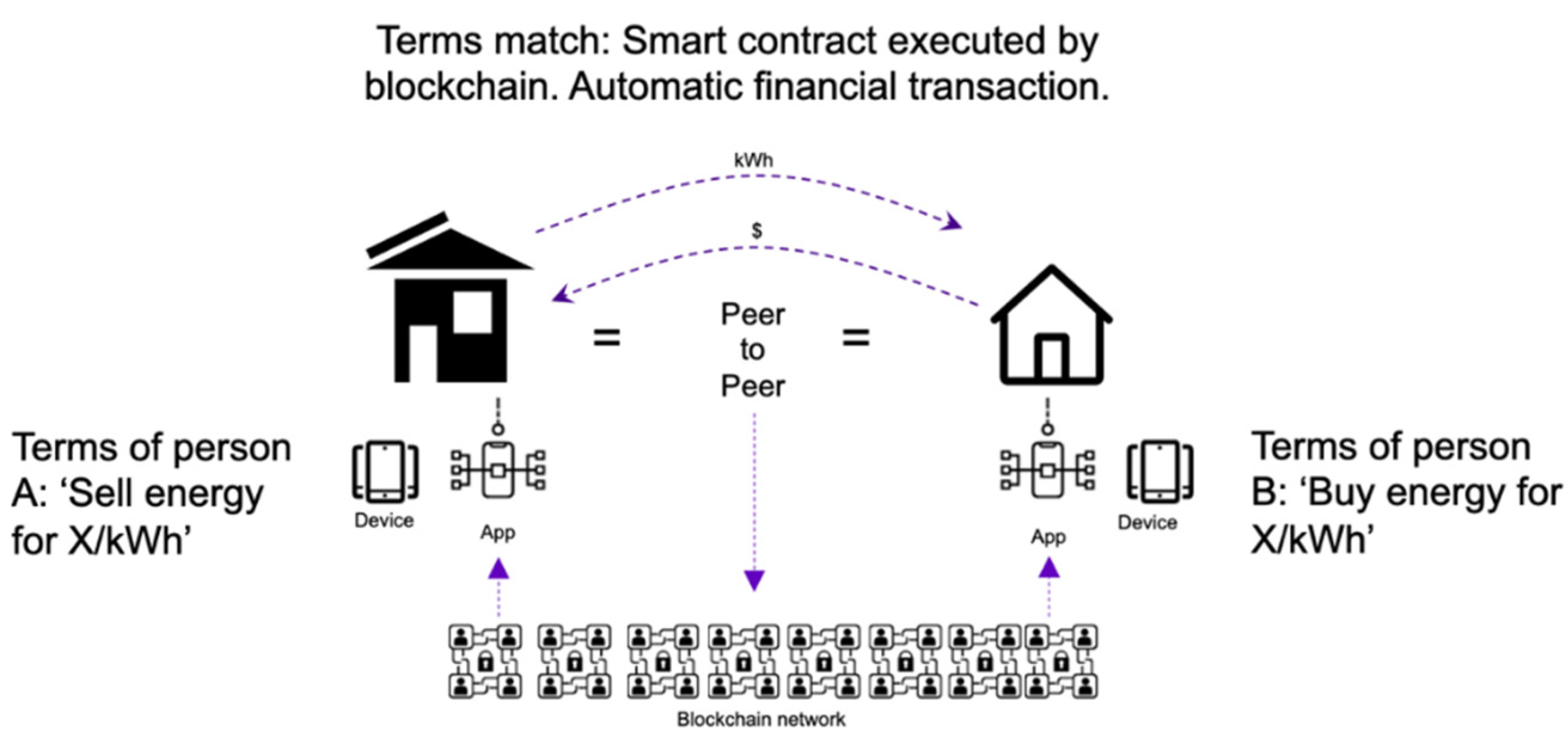

Blockchain and Energy

2. Method

3. Legal Challenges

3.1. Data Privacy

3.2. Smart Contracts

3.3. Prosumer Rights

4. Legal Forms Available to Energy Communities

4.1. The Importance of Incorporation

4.2. Co-Operative Societies

4.3. Limited Liability Partnerships

5. To What Extent Can These Forms Protect Consumers?

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ordonnance n° 2016–1019 du 27 Juillet 2016 Relative à l’Autoconsommation d’Electricité. 2021. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000032938257&categorieLien=id (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland. Experimenten Elektriciteitswet. 2021. Available online: https://www.rvo.nl/subsidies-regelingen/experimenten-elektriciteitswet (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Co-operatives, UK. The Community Shares Handbook—2.1 Bona Fide Co-operative Societies. 2021. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/resources/community-shares-handbook/2-society-legislation/21-bona-fide-co-operative-societies (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Fanone, E.; Gamba, A.; Prokopczuk, M. The Case of Negative Day-ahead Electricity Prices. Energy Econ. 2013, 35, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A. Maximizing solar PV energy penetration using energy storage technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 866–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipworth, D. Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading Using Blockchains—Part 1: Peer-to-Peer in the Energy Transition. IEA DSM Spotlight. December 2017, pp. 5–9. Available online: https://userstcp.org/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Giles, J. Peer to Peer Trading and Microgrids–the Next Big Thing? February 2018. Available online: https://www.regen.co.uk/peer-to-peer-trading-and-microgrids-the-next-big-thing (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. 2008. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Szabo, N. Smart Contracts. 1994. Available online: http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature/LOTwinterschool2006/szabo.best.vwh.net/smart.contracts.html (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Küfner, R. Breaking Down the Smart Contract. April 2018. Available online: https://medium.com/nakamo-to/breaking-down-the-smart-contract-45b249b8bc71 (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Nguyen, C. Brooklyn’s ‘Microgrid’ Did Its First Solar Energy Sale. April 2016. Available online: https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/d7y7n7/transactive-grid-ethereum-brooklyn-microgrid (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Pylon Network. Pylon Network Installs the First “Metron” Energy Meters at Users of the GoiEner Energy Cooperative and Begins to Test Its Blockchain Platform in a Real Environment. March 2018. Available online: https://pylon-network.org/pylon-network-installs-first-metron-energy-meters-users-goiener-energy-cooperative-begins-test-blockchain-platform-real-environment.html (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- De Almeida, A.; Klausmann, N.; van Soest, H.; Cappelli, V. Peer-to-Peer Trading and Energy Community in the Electricity Market: Analysing the Literature on Law and Regulation and Looking Ahead to Future Challenges. April 2021. Available online: https://fsr.eui.eu/publications/?handle=1814/70457 (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Observatorio Blockchain. Pylon Network, Plataforma Blockchain para el Autoconsumo Energetico. April 2019. Available online: https://observatorioblockchain.com/blockchain/pylon-network-la-plataforma-blockchain-que-liderara-el-autoconsumo-energetico-en-espana-tras-la-derogacion-del-impuesto-al-sol/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- EDF Energy. EDF Energy Empowers Social Housing Residents to Trade Solar Energy. February 2019. Available online: https://www.edfenergy.com/media-centre/news-releases/edf-energy-empowers-social-housing-residents-trade-solar-energy (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Repowering London. About Us. Available online: https://www.repowering.org.uk/about-us/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Wörner, A.; Meeuw, A.; Ableitner, L.; Wortmann, F.; Schopfer, S.; Tiefenbeck, V. Trading solar energy within the neighborhood: Field implementation of a blockchain-based electricity market. Energy Inform. 2019, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ableitner, L.; Ableitner, L.; Meeuw, A.; Schopfer, S.; Tiefenbeck, V.; Wortmann, F.; Wörner, A. Quartierstrom—Implementation of a Real World Prosumer Centric Local Energy Market in Walenstadt, Switzerland. 2019. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1905.07242.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Quartierstrom. 2021. Available online: https://quartier-strom.ch/index.php/en/the-essentials-in-brief/ (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Mengelkamp, E.; Garttner, J.; Rock, K.; Orsini, L.; Weinhardt, C. Designing microgrid energy markets: A case study: The Brooklyn Microgrid. Appl. Energy 2017, 210, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoni, M.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D.; Geach, D. Blockchain technology in the energy sector: A systematic review of challenges and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 100, 143–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooklyn Microgrid. 2021. Available online: https://www.brooklyn.energy/ (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Innovation at the Service of Well-Being: Lyon Confluence. 2021. Available online: https://www.lyon-confluence.fr/en/eureka-2016-2020-innovation-service-well-being (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Chen, T.; Bu, S. Realistic Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading Model for Microgrids using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe Conference, Bucharest, Romania, 29 September–2 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, W.; Hu, C.-W.; Chiu, K.-Y. Renewable Energy Bidding Strategies Using Multiagent Q-Learning in Double-Sided Auctions. IEEE Syst. J. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Exergy. Business Whitepaper. April 2018. Available online: https://lo3energy.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Exergy-BIZWhitepaper-v11.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Community Energy England. What Is Community Energy? 2021. Available online: https://communityenergyengland.org/pages/what-is-community-energy (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- European Commission. Stronger Protection, New Opportunities-Commission Guidance on the Direct Application of the General Data Protection Regulation as of 25 May 2018 (COM/2018/043 Final). 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0043&from=EN (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- DLA Piper. Brexit: Final Arrangements for 1 January and Future EU-UK Data Transfers. December 2020. Available online: https://www.dlapiper.com/en/uk/insights/publications/2019/04/no-deal-brexit/data-protection/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Regulation 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data (General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32016R0679; 2021 (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Finck, M. Blockchains and Data Protection in the European Union. Max Planck Inst. Innov. Compet. Res. Pap. 2017, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Article 29 Data Protection Working Party. Opinion 05/2014 on Anonymisation Techniques. April 2014. Available online: https://www.pdpjournals.com/docs/88197.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). Patrick Breyer v Germany (C-582/14). Available online: https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?docid=184668&doclang=EN (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Van Humbeeck, A. The Blockchain-GDPR paradox. J. Data Prot. Priv. 2019, 2, 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- Consensys. Grid+: Welcome to the Future of Energy (White Paper). 2017. Available online: https://whitepaper.io/document/269/grid-whitepaper (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Runyon, J. How Smart Contracts [Could] Simplify Clean Energy Distribution. May 2017. Available online: https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/storage/how-smart-contracts-could-simplify-clean-energy-distribution/#gref (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- McKinsey & Company. What Every Utility CEO Should Know about Blockchain. March 2018. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/electric-power-and-natural-gas/our-insights/what-every-utility-ceo-should-know-about-blockchain (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Norton Rose Fulbright. Can Smart Contracts Be Legally Binding Contracts? An R3 and Norton Rose Fulbright White Paper. November 2016, pp. 22–26. Available online: https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en-ca/knowledge/publications/a90a5588/can-smart-contracts-be-legally-binding-contracts (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. December 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2018.328.01.0082.01.ENG&toc=OJ:L:2018:328:TOC (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Cartwright, J. Contract Law: An Introduction to the English Law of Contract for the Civil Lawyer, 3rd ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2016; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- Beale, H.G.; Chitty, J. Chitty on Contracts, 33rd ed.; Sweet & Maxwell: London, UK, 2018; Chapters 2, 4, 15, 23. [Google Scholar]

- UK Jurisdiction Taskforce. Legal Statement on Cryptoassets and Smart Contracts. November 2019. Available online: https://35z8e83m1ih83drye280o9d1-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/6.6056_JO_Cryptocurrencies_Statement_FINAL_WEB_111119-1.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Ashurst, L.L.P. Smart Contracts—Can Code Ever be Law? March 2018. Available online: https://www.ashurst.com/en/news-and-insights/legal-updates/smart-contracts---can-code-ever-be-law/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Tjong, T.T.E. Formalizing Contract Law for Smart Contracts. Tilburg Priv. Law Work. Pap. Ser. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durovic, M.; Janssen, A.U. The Formation of Blockchain-based Smart Contracts in the Light of Contract Law. Eur. Rev. Priv. Law 2018, 26, 753–771. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation (Committee on Consumer Policy). Summary of Workshop on Protecting Consumers in Peer Platform Markets. June 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sti/consumer/protecting-consumers-in-peer-platform-markets-workshop-summary.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Protecting Consumers in Peer Platform Markets: Exploring The Issues (Paper No. 253). June 2016. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/protecting-consumers-in-peer-platform-markets_5jlwvz39m1zw-en; (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Consumer Rights Act 2015. 2015. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/15/contents/enacted (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Gov.uk. Digital Platforms: EU Consultation Response. January 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-platforms-eu-consultation-response (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A European Agenda for the Collaborative Economy (COM(2016) 356 Final). June 2016. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/com2016-356-final.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity and Amending Directive 2012/27/EU. June 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L0944 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- UK Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. Modernising Consumer Markets-Consumer Green Paper. April 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/699937/modernising-consumer-markets-green-paper.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Hausemer, P.; Rzepecka, J.; Dragulin, M.; Vitiello, S.; Rabuel, L.; Nunu, M.; Diaz, R.A. European Commission: Exploratory Study of Consumer Issues in Online Peer-to-Peer Platform Markets. May 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/final_report_may_2017.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Ordonnance n° 2016-131 du 10 Février 2016 Portant Réforme du Droit des Contrats, du Régime Général et de la Preuve des Obligations. February 2016. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do;jsessionid=A4FA1D0CEE393720C9703EE7C2F99B05.tplgfr32s_1?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000032004939&categorieLien=id (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Chiu, I.; Schneiders, A. Blockchain Technology-Enabled Business Arrangements. In The Law and Governance of Decentralised Business Models—Between Hierarchies and Markets; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Community Energy England. Community Energy State of the Sector 2020. June 2020. Available online: https://communityenergyengland.org/files/document/385/1592215769_CommunityEnergy-StateoftheSector2020Report.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Co-operatives, UK. Simply Legal—All You Need to Know about Legal Forms and Organizational Types for Co-Operatives and Community Owned Enterprises. September 2017. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/sites/default/files/2020-10/simply-legal-final-september-2017.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014. 2014. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/14/contents (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- UK Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. CIC Business Activities: Forms and Step-by-Step Guidelines. March 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/community-interest-companies-business-activities/cic-business-activities-forms-and-step-by-step-guidelines (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- The Hive. Co-operatives UK. 5.1 Choosing to Incorporate. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/start-new-co-op/start/choosing-incorporate; 2021 (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Legaleze. A Glossary of Legal Terms and Expressions in UK Business Law. November 2014. Available online: https://www.legaleze.co.uk/content/Glossary.aspx (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Co-operatives, UK. Model Governing Documents. 2021. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/resources/model-governing-documents (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Co-operatives, UK. Co-Operative Society Director- Duties and Responsibilities. 2021. Available online: https://www.uk.coop/resources/directors-toolkit/co-operative-society-director-duties-and-responsibilities (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Gov.uk. Corporation Tax. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/corporation-tax (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2000. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/12/contents (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Limited Liability Partnerships. Application of Companies Act 2006—Regulations 2009. 2021. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2009/1804/contents/made (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Gov.uk. Set Up and Run a Limited Liability Partnership (LLP). April 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/set-up-and-run-a-limited-liability-partnership-llp (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- European Commission. Do the Data Protection Rules Apply to Data about a Company? 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/reform/rules-business-and-organisations/application-regulation/do-data-protection-rules-apply-data-about-company_en (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Gov.uk. Running a Limited Company. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/running-a-limited-company (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Eberhardt, J.; Tai, S. On or Off the Blockchain? Insights on Off-Chaining Computation and Data. In Proceedings of the 6th European Conference on Service-Oriented and Cloud Computing, Oslo, Norway, 27–29 September 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buterin, V. Privacy on the Blockchain. January 2016. Available online: https://blog.ethereum.org/2016/01/15/privacy-on-the-blockchain (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- The European Union Blockchain Observatory and Forum. Blockchain and the GDPR. October 2018. Available online: https://www.eublockchainforum.eu/sites/default/files/reports/20181016_report_gdpr.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- European Parliament Research Service. Blockchain and the General Data Protection Regulation: Can Distributed Ledgers be Squared with European Data Protection Law? July 2019. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/634445/EPRS_STU(2019)634445_EN.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Levi, S.D.; Lipton, A.B. An Introduction to Smart Contracts and Their Potential and Inherent Limitations. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation. May 2018. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2018/05/26/an-introduction-to-smart-contracts-and-their-potential-and-inherent-limitations (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Filatova, N. Smart contracts from the contract law perspective: Outlining new regulative strategies. Int. J. Law Info. Techol. 2020, 28, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helberger, N.; van Hoboken, J. Little Brother is Tagging You—Legal and Policy Implications of Amateur Data Controllers. Comput. Law Int. 2010, 4, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stene, A.K.; Holte, A.F. Why do Norwegian Consumers Participate in Collaborative Consumption? A Case Study of Airbnb and Bilkollektivet. Norwegian School of Economics. 2014. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/52113631.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Scholz, T. Platform Cooperativism—Challenging the Corporate Sharing Economy. January 2016. Available online: https://rosalux.nyc/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/RLS-NYC_platformcoop.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Cohen, M.; Sundararajan, A. Self-Regulation and Innovation in the Peer-to-Peer Sharing Economy. Univ. Chic. Law Rev. 2015, 82, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, A. European Parliament Report—The Collaborative Economy: Socioeconomic, Regulatory and Policy Issues. 2017. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2017/595360/IPOL_IDA(2017)595360_EN.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

| Co-Operative | LLP | |

|---|---|---|

| Data privacy | 0 | 0 |

| Smart contracts | 1 1 | 1 |

| Prosumer rights | 1 1 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schneiders, A.; Shipworth, D. Community Energy Groups: Can They Shield Consumers from the Risks of Using Blockchain for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading? Energies 2021, 14, 3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14123569

Schneiders A, Shipworth D. Community Energy Groups: Can They Shield Consumers from the Risks of Using Blockchain for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading? Energies. 2021; 14(12):3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14123569

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchneiders, Alexandra, and David Shipworth. 2021. "Community Energy Groups: Can They Shield Consumers from the Risks of Using Blockchain for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading?" Energies 14, no. 12: 3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14123569

APA StyleSchneiders, A., & Shipworth, D. (2021). Community Energy Groups: Can They Shield Consumers from the Risks of Using Blockchain for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading? Energies, 14(12), 3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14123569