Just Transitions, Poverty and Energy Consumption: Personal Carbon Accounts and Households in Poverty

Abstract

1. Introduction: Poverty, Climate Justice and Personal Carbon Accounts

1.1. Background

1.2. Just Transitions to a Low Carbon Future: Responsibility, Choice, Poverty

1.2.1. Respective Capacities and Just Transitions

1.2.2. Poverty, Choice and Decision-Making

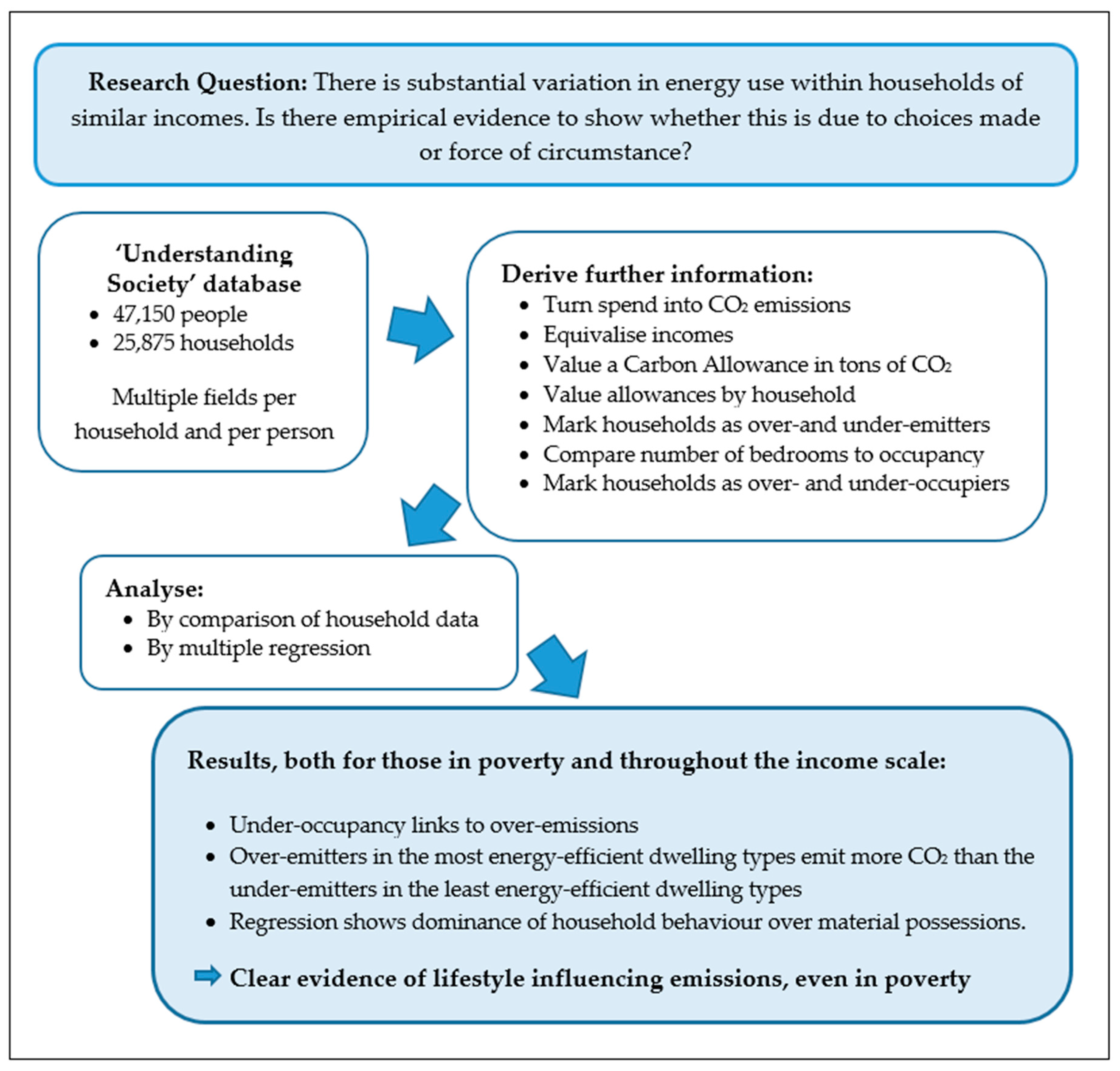

2. Materials and Methods: Unpacking Justice in UK Carbon Emissions

3. Results: Unpacking the Social Impact of a Personal Carbon Allowance Scheme in the UK

3.1. Emissions Levels and Income

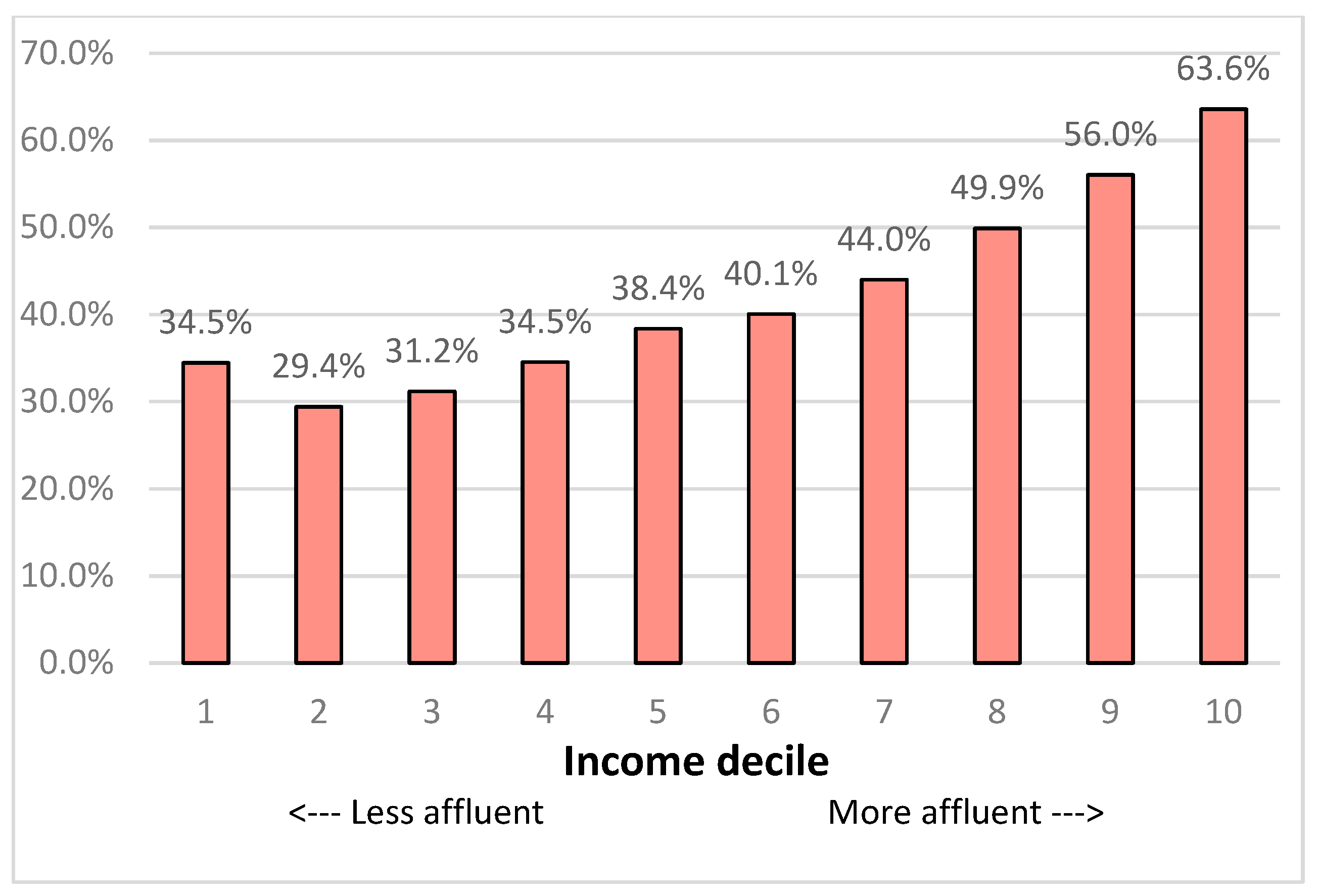

3.2. Proportion of High Emitters

3.3. Relative Income Poverty: Composition and Emissions of Households

3.4. Relative Income Poverty by Tenure and Occupancy Levels

3.5. Fuel Poverty

3.6. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Capacity to Act

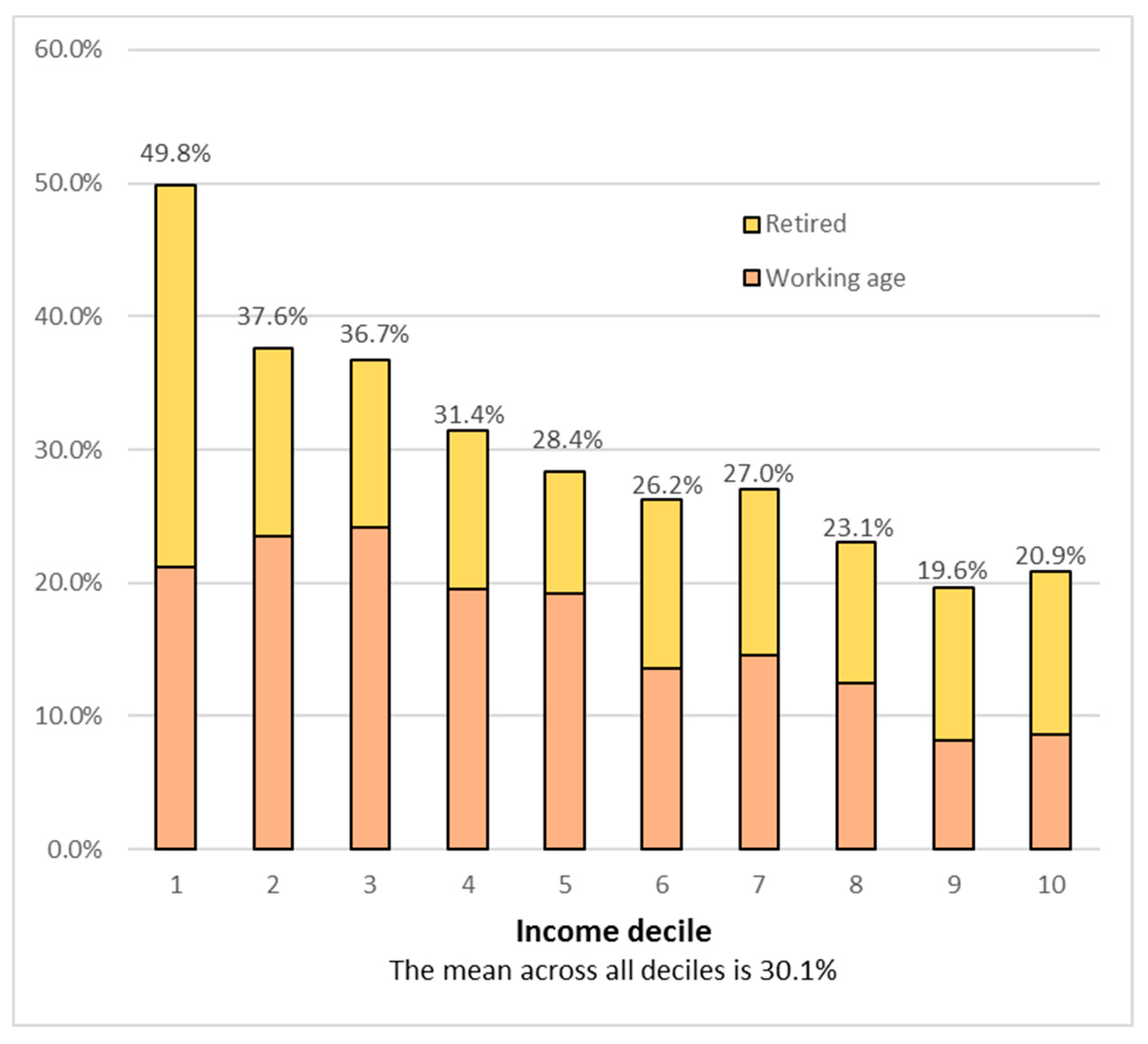

4.2. Choice Limitation: Old Age

4.3. Choice Limitation: Social Norms

4.4. Responsibility and Justice

4.5. Limitations, Literature and Further Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Principal Component Analysis and Rotated Factor Analysis

| Percent of Variance Explained | Under-Emitters | Over-Emitters |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 22.0% | 18.9% |

| Factor 2 | 12.3% | 13.4% |

| Factor 3 | 10.3% | 10.5% |

| Factor 4 | 9.3% | 8.9% |

| Total | 53.8% | 51.8% |

| Factor 1: | “Consumers”: relates total household emissions, salary, adult numbers, cars, employment, rooms, home ownership and consumer goods. |

| Factor 2: | “Climate concerned”: relates the environmental beliefs and very mildly the environmental habits. However, the coefficient of the emissions variable is under ±0.1; environmental beliefs are almost completely unconnected to emissions. |

| Factor 3: | Relates children, employment, tax credits, council tax and housing benefits. |

| Percent of Variance Explained | Under-Emitters | Over-Emitters |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 13.6% | 14.3% |

| Factor 2 | 13.6% | 13.2% |

| Factor 3 | 13.1% | 11.7% |

| Factor 4 | 10.9% | 10.3% |

| Total | 51.2% | 49.5% |

| Factor 1: | “Working poor”: links wages, children, income support, housing benefit or council tax benefit and excludes home ownership and pensioners. |

| Factor 2: | Strongly varies with numbers of appliances (coefficient = 0.90) and moderate variance in emissions and little else. |

| Factor 3: | “Consumers”: excludes home ownership but otherwise as Factor 1 for the whole (richer) database. Emissions coefficient high at 0.61. |

| Factor 4: | “Climate concerned” as Factor 2 for the whole (richer) database. Emissions coefficient minimal at 0.02. |

| Factor 1: | Strongly varies with numbers of appliances (coefficient = 0.95) and moderate variance in emissions and little else. |

| Factor 2: | “Working poor”: links wages, children, income support, housing benefit or council tax benefit and excludes home ownership and pensioners. |

| Factor 3: | “Climate concerned” as Factor 2 for the whole (richer) database. Emissions coefficient minimal at 0.02. |

| Factor 4: | “Consumers”: links emissions, adult numbers, rooms, oil or other heating, cars and rurality. Excludes wages (these vary relatively little across the poverty band), numbers employed and home ownership but otherwise similar Factor 1 for the whole (richer) database. Emissions coefficient high at 0.58. |

References

- Department for Communities and Local Government (DLG). 2010 to 2015 Government Policy: Energy Efficiency in Buildings. 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-energy-efficiency-in-buildings/2010-to-2015-government-policy-energy-efficiency-in-buildings (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Climate Change Act (CCA). Modified by Standing Order, 2050 Target Amendment, 2019. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/27/pdfs/ukpga_20080027_en.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- DECC. Annual Fuel Poverty Statistics Report: 2015; Department of Energy and Climate Change: London, UK, 2015.

- Lachapelle, E. Communicating about Carbon Taxes and Emissions Trading Programs. In Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Climate Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian Newspaper. Australia Kills off Carbon Tax. 2014. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jul/17/australia-kills-off-carbon-tax (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- BBC. France Protests: PM Philippe Suspends Fuel Tax Rises. 2018. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-46437904 (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Parag, Y.; Eyre, N. Barriers to personal carbon trading in the policy arena. Clim. Policy 2010, 10, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, N.; Rosenow, J. Banning the bulb: Institutional evolution and the phased ban of incandescent lighting in Germany. Energy Policy 2014, 67, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, R. Environmental Market Failures: Local Market-Based Corrective Mechanisms for Global Problems. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 1997, 1, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, D. Tradable Quotas: Using information technology to cap national carbon emissions. Eur. Environ. 1997, 7, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, M. Carbon budget watchers. Town Ctry. Plan. Oct. 1998, 67, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Starkey, R.; Anderson, K. Domestic Tradable Quotas: A Policy Instrument for the Reduction of Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research: Norwich, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, J.; Lockwood, M. Plan B: The Prospects for Personal Carbon Trading; IPPR: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thumim, J.; White, V. Distributional Impacts of Personal Carbon Trading; Centre for Sustainable Energy: Bristol, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jagers, S.C.; Lofgren, A.; Stripple, J. Attitudes to PCAs: Political trust, fairness and ideology. Clim. Policy 2010, 10, 410–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. The economics of personal carbon trading. Clim. Policy 2010, 10, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caney, S. Two Kinds of Climate Justice: Avoiding Harm and Sharing Burdens. J. Political Philos. 2014, 22, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K. Setting energy justice apart from the crowd: Lessons from environmental and climate justice. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of National Statistics. Housing. Soc. Trends 2011, 41, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, P.; Mulvaney, D. The Political Economy of the “just transition”. Geogr. J. 2013, 179, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasanoff, S. Just transitions: A humble approach to global energy futures. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 35, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, I. The Capabilities Approach: A theoretical survey. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilovich, T.; Ross, L. The Wisest One in the Room; Oneworld Publications: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Salecl, R. The Tyranny of Choice; Profile Books: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- John, P.; Smith, G.; Stoker, G. Nudge, Nudge, Think, Think: Two Strategies for Changing Civic Behaviour. Political Q. 2019, 80, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrentine, T.; Karani, K. Car buyers and fuel economy? Energy Policy 2007, 35, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, B. Travel Mode Choice as Habitual Behaviour: A Review of LiteratureI; Aarhus School of Business: Aarhus, Denmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Dear, R.; Brager, G.S. Developing an Adaptive Model of Thermal Comfort and Preference; ASHRAE Transactions: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 1998; Volume 104, Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qq2p9c6 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Hall, S.M. Everyday family experiences of the financial crisis: Getting by in the recent economic recession. J. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 16, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.M.; Holmes, H. Making do and Getting By? Beyond a romantic politics of Austerity and Crisis. Article in Discover Society. 2017. Available online: https://discoversociety.org/2017/05/02/making-do-and-getting-by-beyond-a-romantic-politics-of-austerity-and-crisis/ (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Haushofer, J.; Fehr, E. On the psychology of poverty. Science 2014, 344, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E. Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much; Time Books, Henry Holt & Company LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Snell, C. Policy pathways to justice in energy efficiency. In Proceedings of the Presentation to Food Poverty Research Network, Newcastle, UK, 7 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, T. Energy Poverty in Western Australia. In Proceedings of the Presentation to Food Poverty Research Network, Newcastle, UK, 7 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sherriff, G. Socio-Technical Concepts. In Proceedings of the Presentation to Food Poverty Research Network, Newcastle, UK, 6 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel, M.J. What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. Presented at the Lecture Delivered at Brasenose College, Oxford, UK, 11–12 May 1998. Available online: academia.edu (accessed on 17 April 2019).

- Liu, L.; Feng, T.; Suo, T.; Lee, K.; Li, H. Adapting to the Destitute Situations: Poverty Cues Lead to Short-Term Choice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, P. Paying More to Be Poor: The Poverty Premium in Energy, Telecommunications and Finance; Citizens Advice Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Belaïd, F. Exposure and risk to fuel poverty in France: Examining the extent of the fuel precariousness and its salient determinants. Energy Policy 2018, 114, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, A.; Whitley, E.; Curl, A. Occupant behaviour as a fourth driver of fuel poverty (aka warmth & energy deprivation). Energy Policy 2019, 129, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Pykett, J.; Whitehead, M. Governing temptation: Changing behaviour in an age of libertarian paternalism. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 35, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.W.; Prillwitz, J. A smarter choice? Exploring the behaviour change agenda for environmentally sustainable mobility. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Aarts, H. Habit, Attitude, and Planned Behaviour: Is Habit an Empty Construct or an Interesting Case of Goal directed Automaticity? Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 10, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Walker, I.; Davis, A.; Jurasek, M. Context change and travel mode choice: Combining the habit discontinuity and self-activation hypotheses. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, M. Personal Carbon Allowances: A revised model to alleviate distributional issues. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büsch, M.; Schnepf, S. Who emits most? Associations between socio-economic factors and UK households’ home energy, transport, indirect and total CO2 emissions. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 90, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Demos. Poverty in Perspective; Magdalen House: London, UK, 2012; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Fiscal Studies. Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2015; Institute of Fiscal Studies: London, UK, 2015; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Shelter. Bedroom Tax Ruling “Devastating News” for Disabled Families’. 2013. Available online: http://england.shelter.org.uk/news/july_2013/bedroom_tax_ruling_devastating_news_for_disabled_families (accessed on 29 March 2017).

- Green Party Manifesto. The Green Party of England and Wales, Development House, 56–64 Leonard Street, London EC2A 4LT. 2015, p. 44. Available online: https://www.greenparty.org.uk/assets/files/Elections/Green%20Party%20Manifesto%202019.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- The Independent Newspaper. 2013. Available online: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/big-lie-behind-the-bedroom-tax-families-trapped-with-nowhere-to-move-face-penalty-for-having-spare-8745597.html (accessed on 14 February 2017).

- Gibb, K. The multiple policy failures of the UK bedroom tax. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2015, 15, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, K. The Bedroom Tax in Scotland. Report to the Welfare Reform Committee; Scottish Parliament: Edinburgh, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt, S.; Lawson, S.; Patterson, R.; Holding, E.; Dennison, A.; Sowden, S.; Brown, J. A qualitative study of the impact of the UK “bedroom tax”. J. Public Health 2015, 38, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H.; Bouzarovski, S.; Snell, C. Rethinking the measurement of energy poverty in Europe: A critical analysis of indicators and data. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Housing Statistics at 31.3.18. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Housing Statistical Release 24.5.19. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/803958/Dwelling_Stock_Estimates_31_March_2018__England.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2019).

- Elderkin, S. Defra. An Assessment of the Potential Effectiveness and Strategic Fit of Personal Carbon Trading; Defra: London, UK, 2008.

- Giddens, A. The Politics of Climate Change: National Responses to the Challenge of Global Warming; Policy Network: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, I.; Abdallah, S.; Johnson, V. The Distribution of Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Households in the UK; Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, I.; White, V.; Thumim, J.; Bridgeman, T. Distribution of Carbon Emissions in the UK: Implications for Domestic Energy Policy; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, S. The Effectiveness of Feedback on Energy Consumption; Oxford Environmental Institute: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G.; Newborough, M. Dynamic energy-consumption indicators for domestic appliances: Environment, behaviour and design. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, B.; Moeller, S. GHG Emissions and the Rural-Urban Divide. A Carbon Footprint Analysis Based on the German Official Income and Expenditure Survey. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, A.; Zahran, S. The carbon implications of declining household scale economies. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 116, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of National Statistics. 2013. Available online: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census/detailed-characteristics-on-housing-for-local-authorities-in-england-and-wales/short-story-on-detailed-characteristics.html (accessed on 29 March 2017).

- Druckman, A.; Jackson, T. Household energy consumption in the UK: A highly geographically and socio-economically disaggregated model. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3177–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Low Carbon Behaviours Framework; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2016; p. 17.

- Boardman, B. Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth; Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, R.; Lilley, R.; Cass, J. Behaviour Change and Home Energy Coaching; Ceredigion County Council; Aberystwyth University: Wales, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, S. Changeworks’ charity. In Proceedings of the Presentation to Food Poverty Research Network Meeting, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK, 7 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Homes. Quoted in Inside Housing. 2015. Available online: http://www.insidehousing.co.uk/energy-efficiency-progress-on-social-homes-stalls/7010051.article (accessed on 20 March 2017).

- DECC. National Energy Efficiency Data Framework: Annex E, Table A 3.1.; Department of Energy & Climate Change: London, UK, 2012.

- The Guardian Newspaper. Loneliness as Bad for Health as Long-Term Illness, Says GPs’ Chief. 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/oct/12/loneliness-as-bad-for-health-as-long-term-illness-says-gps-chief (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Whitehead, M. The wood for the trees: Ordinary environmental injustice and the everyday right to urban nature. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 662–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.B. The Paradox of Aging in Place in Assisted Living; Bergin & Garvey: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.A.P. Place identification and positive realities of aging. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2001, 16, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities Project. 2007. Available online: https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Mill, J.S. On Liberty; John W Parker & Son: London, UK, 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, J.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R. The Meaning of “Aging in Place” to Older People. Gerontologist 2011, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annual Report 2010–2011; Behavioural Insights Team, Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2011; p. 13.

- Angelini, V.; Brugiavini, A.; Weber, G. Does Downsizing of housing equity alleviate financial distress in old age? In The Individual and the Welfare State; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gram-Hanssen, K. Teenage consumption of cleanliness: How to make it sustainable? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2007, 3, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberlein, T. Navigating Environmental Attitudes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brom, P.; Hansen, A.; Gram-Hanssen, K.; Meijer, A.; Visscher, H. Variances in residential heating consumption-Importance of building characteristics and occupants analysed by movers and stayers. Appl. Energy 2019, 250, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraseni, T.N.; Qu, J.; Zeng, J. A comparison of trends and magnitudes of household carbon emissions between China, Canada and UK. Environ. Dev. 2015, 15, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Chang, K. Cutting CO2 intensity targets of interprovincial emissions trading in China. Appl. Energy 2016, 163, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Han, L.; Yin, Z.; Luo, K. A competitive carbon emissions scheme with hybrid fiscal incentives: The evidence from a taxi industry. Energy Policy 2017, 102, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Karplus, V.; Cassisa, C.; Zhang, X. Emissions trading in China: Progress and prospects. Energy Policy 2014, 75, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, L.; Clapp, A. Applying Personal Carbon Trading: A proposed ‘Carbon, Health & Savings system’ for British Columbia. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Maraseni, T.N.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yusuf, T. A Comparison of Household Carbon Emission Patterns of Urban and Rural China over the 17 Year Period (1995–2011). Energies 2015, 8, 10537–10557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresner, S.; Ekins, P. Economic Instruments to Improve UK Home Energy Efficiency without Negative Social Impacts. Fisc. Stud. 2006, 27, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean Tons CO2 Emitted | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Under-Emitters | Over-Emitters | Significance of Difference | |

| Retired | 3.5 | 7.3 | 99.9% |

| Singles | 2.2 | 6.7 | 99.9% |

| Lone Parents | 4.7 | 8.9 | 99.9% |

| Couples with no dependents | 4.6 | 12.1 | 99.9% |

| Families | 6.9 | 15.9 | 99.9% |

| Adults sharing | 5.5 | 13.0 | 99.9% |

| Mean Tons CO2 Emitted | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Under-Emitters | Over-Emitters | Significance of Difference | |

| Detached | 5.7 | 10.2 | 99.9% |

| Semi-detached | 5.1 | 8.2 | 99.9% |

| End Terraced | 4.6 | 8.1 | 99.9% |

| Terraced | 4.6 | 7.7 | 99.9% |

| Purpose Built Flat | 2.8 | 6.3 | 99.9% |

| Converted Flat | 2.6 | 6.7 | 99.9% |

| 4.4 | 8.4 | ||

| For Households in Poverty: Total Emissions, Includes Oil Fired Central Heating as a Regression Variable | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under-Emitters | n = 1814 | Over-Emitters | n = 984 | ||||||||

| F(9, 1804) | =201.71 | F(9, 974) | = 128.82 | ||||||||

| Prob > F | =0.0000 | Prob > F | = 0.0000 | ||||||||

| vs. Total household emissions | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P > |t| | Beta | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P > |t| | Beta | Z |

| Household monthly gross income | 0.00047 | 0.00014 | 3.32 | 0.001 | 0.10 | −0.00023 | 0.00025 | −0.92 | 0.358 | 0.02 | 2.44 |

| Number of adults | 1.020 | 0.090 | 11.31 | 0.000 | 0.37 | 3.36 | 0.21 | 15.94 | 0.000 | 0.42 | −10.21 |

| Number of children | 0.413 | 0.066 | 6.26 | 0.000 | 0.16 | 1.36 | 0.17 | 8.24 | 0.000 | 0.19 | −5.34 |

| Total number of rooms in home | 0.236 | 0.036 | 6.59 | 0.000 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 2.44 | 0.015 | 0.06 | 0.45 |

| Central heating by gas | 0.881 | 0.103 | 8.52 | 0.000 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 0.505 | 0.02 | 1.38 |

| Central heating by oil | 2.363 | 0.273 | 8.66 | 0.000 | 0.13 | 3.76 | 0.47 | 7.93 | 0.000 | 0.27 | −2.55 |

| Central heating by other solid fuel | 0.791 | 0.276 | 2.86 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 1.34 | 0.37 | 3.66 | 0.000 | 0.09 | −1.20 |

| Number of cars in the household | 0.916 | 0.084 | 10.88 | 0.000 | 0.26 | 0.94 | 0.19 | 4.84 | 0.000 | 0.14 | −0.09 |

| Number of people employed | −0.035 | 0.085 | −0.41 | 0.678 | 0.01 | 0.63 | 0.20 | 3.14 | 0.002 | 0.08 | −3.05 |

| Adjusted r-squared | 0.601 | Adjusted r-squared | 0.552 | ||||||||

| Whole Population: Total Emissions, All Heating Types | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under-Emitters | n = 11,596 | Over-Emitters | n = 8999 | ||||||||

| F (9, 11586) | =1388.2 | F (9, 8989) | =896.0 | ||||||||

| Prob > F | =0.000 | Prob > F | =0.000 | ||||||||

| vs. Total household emissions | Coef. | Std. Err | t | P > |t| | Beta | Coef. | Std. Err | t | P > |t| | Beta | Z |

| Household monthly gross income | 0.00005 | 0.00001 | 4.09 | 0.000 | 0.04 | 0.00015 | 0.00003 | 6.12 | 0.000 | 0.08 | −3.16 |

| Number of Adults | 1.27 | 0.04 | 34.73 | 0.000 | 0.41 | 2.97 | 0.10 | 30.33 | 0.000 | 0.37 | −16.22 |

| Number of Children | 0.56 | 0.03 | 21.64 | 0.000 | 0.18 | 1.06 | 0.07 | 15.56 | 0.000 | 0.13 | −6.91 |

| Total Rooms | 0.24 | 0.02 | 15.87 | 0.000 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 11.49 | 0.000 | 0.13 | −4.34 |

| Central heating by gas | 1.03 | 0.05 | 20.00 | 0.000 | 0.12 | −0.25 | 0.20 | −1.23 | 0.218 | −0.02 | 6.14 |

| Central heating by oil | 2.61 | 0.17 | 15.69 | 0.000 | 0.10 | 4.18 | 0.23 | 18.03 | 0.000 | 0.24 | −5.50 |

| Central heatingby other solid fuel | 0.75 | 0.12 | 6.35 | 0.000 | 0.04 | 1.58 | 0.20 | 7.94 | 0.000 | 0.09 | −3.60 |

| Number of Cars in the household | 0.89 | 0.03 | 27.48 | 0.000 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.11 | 6.11 | 0.000 | 0.11 | 1.70 |

| Number of people employed | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.11 | 0.035 | 0.02 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 8.48 | 0.000 | 0.09 | −7.07 |

| Adjusted r-squared | 0.634 | Adjusted r-squared | 0.584 | ||||||||

| Result | Households in Poverty | All Households |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of over-emitting households under-occupying their dwellings. Proportion of under-emitting households under-occupying their dwellings. Interpretation: underoccupancy is one cause of over-emissions. | 82% 56% | 85% 60% |

| On average, over-emitting households in the most energy-efficient dwelling type (purpose-built flats or apartments) emit more than under-emitting households in the least energy-efficient households (detached houses). Interpretation: in aggregate, this is apparent proof that lifestyle is a cause of over-emissions, irrespective of income. | True | True |

| Regression analysis shows that, adjusting for materialistic differences between households (such as cars and numbers of rooms—Table 3 and Table 4), adults in over-emitting households emit very significantly more than those in under-emitting households. Emission variations caused by adults are the most important factor in the regressions (the factor has the highest β-values by some margin) and so are more important than variations caused by other factors such as cars or numbers of rooms. Also, the difference between the coefficients of the adult emissions factor between Under- and Over-Emitters is the most significantly different (highest z value), significant at 0.0000%. Interpretation: in aggregate, this is apparent proof that behaviour is a cause of over-emissions irrespective of income. This is distinguished from the previous result as “lifestyle” includes (for example) home size and car ownership, whereas this result theoretically accounts for these materialistic variables and attributes cause to the actions of the occupants. | True by a factor of over 3 | True by a factor of over 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burgess, M.; Whitehead, M. Just Transitions, Poverty and Energy Consumption: Personal Carbon Accounts and Households in Poverty. Energies 2020, 13, 5953. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13225953

Burgess M, Whitehead M. Just Transitions, Poverty and Energy Consumption: Personal Carbon Accounts and Households in Poverty. Energies. 2020; 13(22):5953. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13225953

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurgess, Martin, and Mark Whitehead. 2020. "Just Transitions, Poverty and Energy Consumption: Personal Carbon Accounts and Households in Poverty" Energies 13, no. 22: 5953. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13225953

APA StyleBurgess, M., & Whitehead, M. (2020). Just Transitions, Poverty and Energy Consumption: Personal Carbon Accounts and Households in Poverty. Energies, 13(22), 5953. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13225953