Optimising Frequency-Based Railway Services with a Limited Fleet Endowment: An Energy-Efficient Perspective †

Abstract

1. Introduction

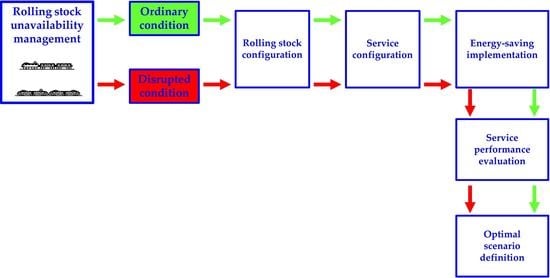

2. The Proposed Methodology for Managing Rolling Stock Unavailability in an Energy-Saving Context

2.1. Frequency-Based Service Definition

- the maximum and minimum value of term according to Constraint (3);

- the minimum value of the feasible headway as shown by Condition (11).

2.2. Implementation of Energy-Saving Strategies (ESSs)

- service providers (i.e., infrastructure operators and/or rail service operators) who seek to minimise energy consumption;

- service customers (i.e., passengers and/or logistic operators) who seek to minimise total travel times.

- variability in the service condition of a rail convoy in terms of running, dwell and inversion times (i.e., primary delays);

- interaction via the signalling system among the train considered and other rail convoys which have different travel times from the planned ones (i.e., secondary delays).

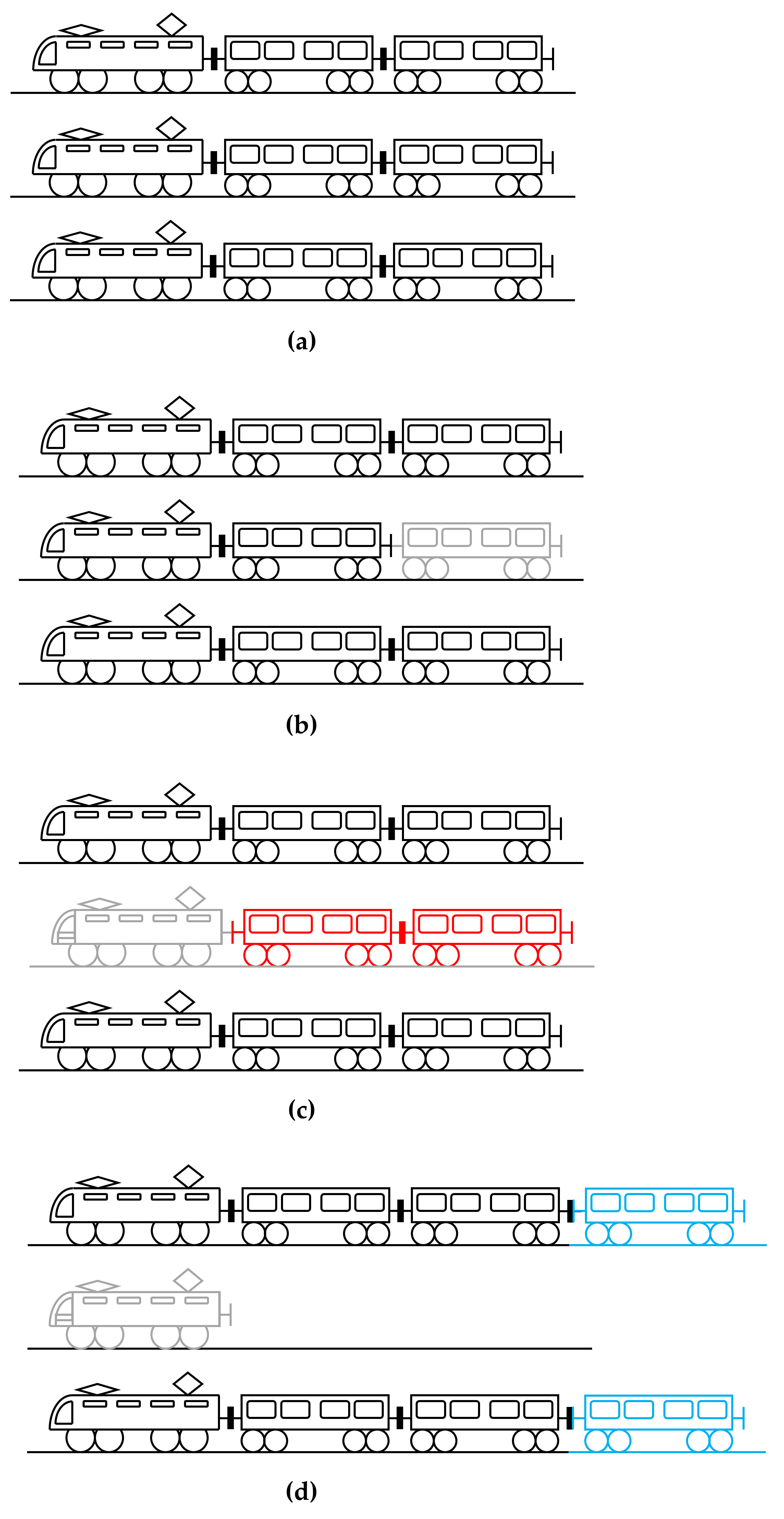

2.3. Management of Rolling Stock Unavailability

- an increase in waiting time due to the increase in headway;

- an increase in crowding levels due to the increase in headway since the number of passengers waiting on the station platform may be calculated as the product between the passenger arrival rate and the service headway (obviously, in the case of variable arrival rate, the above product has to be properly integrated);

- an increase in the probability of not being able to board the first train arriving due to the increase in train occupancy (the service has lower capacity levels ) and an increase in the number of passengers waiting (to board) on the platform. Obviously, in the event of not being able to board the first train, passenger waiting time increases.

- the number of operating rail convoys is restored (see Figure 4c) so that the planned headway is also restored, according to Equation (1). In this case, passenger waiting time tends to remain unchanged. Obviously, since the service capacity is reduced (due to a reduction in train capacity ), some passengers may not be able to board the first rail convoy arriving, thereby experiencing an increase in waiting time;

- the number of operating convoys is increased (see Figure 4d) with respect to the ordinary condition (shown in Figure 4a). In this case, the planned headway may be reduced according to Equation (1), with the subsequent reduction in passenger waiting times. Obviously, more frequent trains lead to a reduction in crowding levels on platforms. However, as regards the service capacity being calculated with Equation (12), neither a reduction nor an increase can be stated a priori, but a proper simulation model is required for determining its value.

- if passengers at a station platform are not able to board the first arriving train, they have to wait for the subsequent trains by increasing considerably their waiting time [20];

- if this increase in waiting time exceeds certain thresholds, users can choose to leave the rail system to utilise a different transportation system [22].

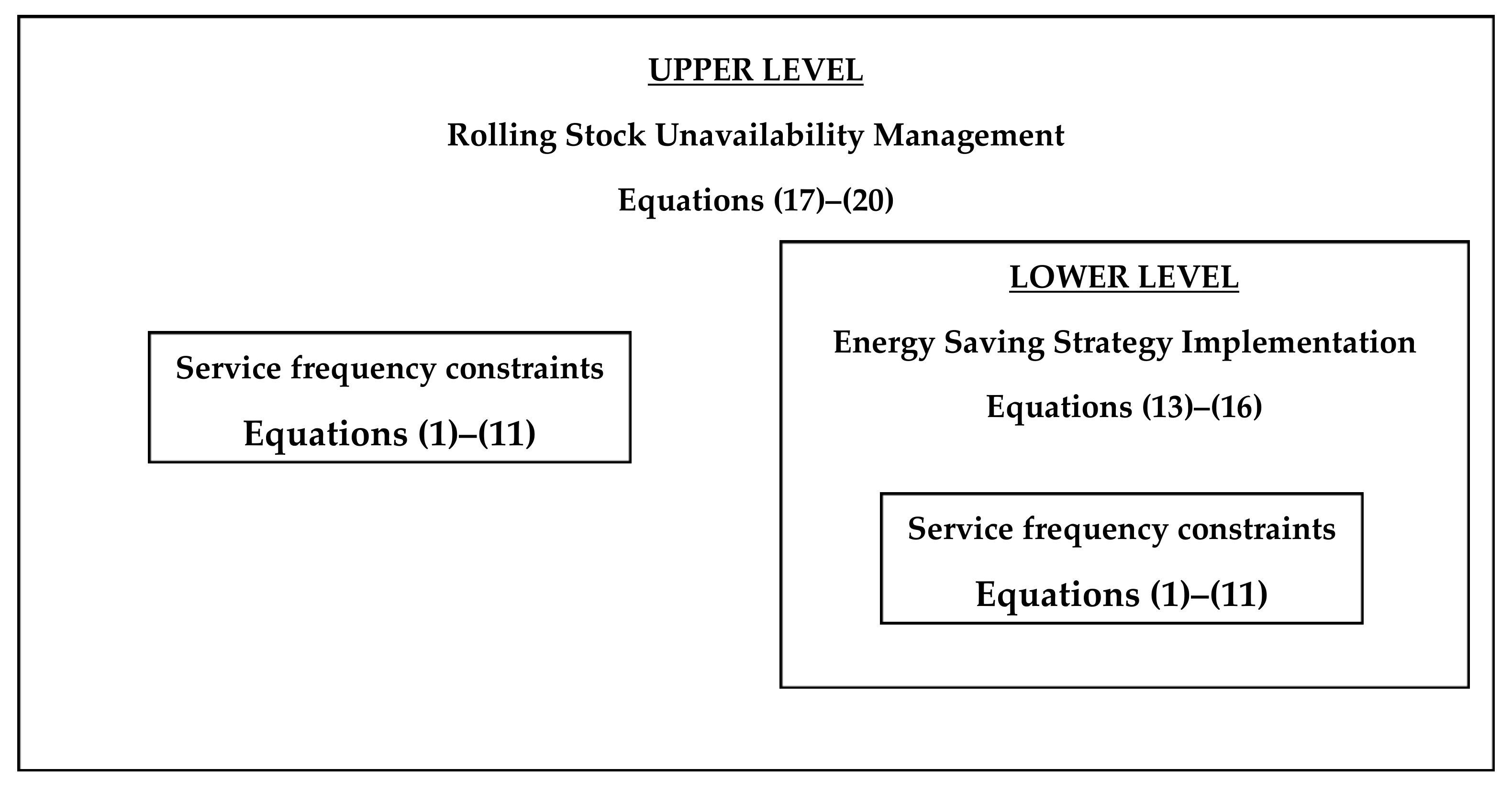

2.4. Joint Management of Rolling Stock Unavailability and ESS Implementation

- the upper level defines the optimal intervention strategy in the case of rolling stock unavailability, as formulated by Equations (17)–(20);

- the lower level is the implementation of an energy-saving strategy which jointly minimises the user generalised cost and energy consumption, as formulated by Equations (13)–(16);

3. Application to a Regional Railway Line

- the adopted Energy Saving Strategy (ESS) consists in imposing a single speed limit for the outward trip and a single speed limit for the return trip;

- all runs are subjected to the same speed limits;

- the increase in travel times is offset by a reduction in layover times so as to maintain service headway;

- speed limits are imposed so as to maximise the use of layover time (i.e., minimising total energy consumption);

- no energy recovery systems/devices are considered;

- the total layover time may be freely divided between the outward and return trips, according to the theoretical approach proposed by [32].

- if a rolling stock scenario can be implemented with a single service configuration, ESS implementation will provide a reduction in objective function value;

- if a rolling stock scenario can be implemented with more than one service configuration, only that with the lower planned headway (i.e., term ) will yield a reduction in objective function value, while the other scenarios will result in an increase in objective function value.

- (1)

- all trains are operated by avoiding any ESS implementation (i.e., all services are performed in time-optimal condition);

- (2)

- all trains are operated by implementing a suitable ESS (i.e., all speed limits are recalculated and applied according to the new rolling stock availability);

- (3)

- all trains are operated by implementing an inappropriate ESS consisting of the speed limits adopted in ordinary conditions (i.e., the railway service operator is unable to update the speed limits promptly).

- the disrupted condition always yields an increase in objective function value regardless of the strategy adopted due to the discomfort imposed upon passengers;

- the adoption of the optimised ESS always yields an increase in the objective function with respect to the time-optimal condition, except in the case of the lowest planned headway (i.e. scenario DS1);

- the adoption of ESS in the case of nonoptimised speed limits (i.e., the optimal value being calculated in the case of ordinary conditions) always yields an increase in the objective function.

4. Conclusions and Research Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Rolling Stock Scenario | Single-Header Convoys | Double-Header Convoys | Triple-Header Convoys | Total Rail Convoys | Number of Railcars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 24 |

| B2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 24 |

| B3 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 24 |

| B4 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 24 |

| B5 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 24 |

| B6 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 24 |

| B7 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 24 |

| B8 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 24 |

| B9 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 24 |

| B10 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 24 |

| B11 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 13 | 24 |

| B12 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 24 |

| B13 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 24 |

| B14 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 24 |

| B15 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 24 |

| B16 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 24 |

| B17 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 24 |

| B18 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 24 |

| B19 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 24 |

| B20 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 24 |

| B21 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 24 |

| B22 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 12 | 24 |

| B23 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 13 | 24 |

| B24 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 24 |

| B25 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 13 | 24 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Rolling Stock Scenario | Hplan (min) | NC (#) | TLTTO (min) | Capserv (pax/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | B1 | 20.0 | 8 | 1.55 | 4050 |

| DS2 | B1 | 20.5 | 8 | 5.55 | 3951 |

| DS3 | B1 | 21.0 | 8 | 9.55 | 3857 |

| DS4 | B1 | 21.5 | 8 | 13.55 | 3767 |

| DS5 | B1 | 22.0 | 8 | 17.55 | 3682 |

| DS6 | B1 | 22.5 | 8 | 21.55 | 3600 |

| DS7 | B2 | 18.0 | 9 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS8 | B2 | 18.5 | 9 | 8.05 | 3892 |

| DS9 | B2 | 19.0 | 9 | 12.55 | 3789 |

| DS10 | B2 | 19.5 | 9 | 17.05 | 3692 |

| DS11 | B3 | 16.0 | 10 | 1.55 | 4050 |

| DS12 | B3 | 16.5 | 10 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS13 | B3 | 17.0 | 10 | 11.55 | 3812 |

| DS14 | B4 | 18.0 | 9 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS15 | B4 | 18.5 | 9 | 8.05 | 3892 |

| DS16 | B4 | 19.0 | 9 | 12.55 | 3789 |

| DS17 | B4 | 19.5 | 9 | 17.05 | 3692 |

| DS18 | B5 | 16.0 | 10 | 1.55 | 4050 |

| DS19 | B5 | 16.5 | 10 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS20 | B5 | 17.0 | 10 | 11.55 | 3812 |

| DS21 | B6 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4063 |

| DS22 | B6 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS23 | B7 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS24 | B8 | 16.0 | 10 | 1.55 | 4050 |

| DS25 | B8 | 16.5 | 10 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS26 | B8 | 17.0 | 10 | 11.55 | 3812 |

| DS27 | B9 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4063 |

| DS28 | B9 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS29 | B10 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS30 | B11 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 3988 |

| DS31 | B12 | 16.0 | 10 | 1.55 | 4050 |

| DS32 | B12 | 16.5 | 10 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS33 | B12 | 17.0 | 10 | 11.55 | 3812 |

| DS34 | B13 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4063 |

| DS35 | B13 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS36 | B14 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS37 | B15 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 3988 |

| DS38 | B16 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4063 |

| DS39 | B16 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS40 | B17 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS41 | B18 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 3988 |

| DS42 | B19 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4063 |

| DS43 | B19 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 3927 |

| DS44 | B20 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS45 | B21 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 3988 |

| DS46 | B22 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS47 | B23 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 3988 |

| DS48 | B24 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4000 |

| DS49 | B25 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 3988 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Rolling Stock Scenario | Hplan (min) | NC (#) | Average Objective Function Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Time Optimal) (€/pax) | (Optimised ESS) (€/pax) | (Non-Optimised ESS) (€/pax) | ||||

| DS1 | B1 | 20.0 | 8 | 5.071 | 5.060 | unfeasible |

| DS2 | B1 | 20.5 | 8 | 5.119 | 5.135 | 5.120 |

| DS3 | B1 | 21.0 | 8 | 5.163 | 5.224 | 5.165 |

| DS4 | B1 | 21.5 | 8 | 5.209 | 5.226 | 5.212 |

| DS5 | B1 | 22.0 | 8 | 5.251 | 5.426 | 5.255 |

| DS6 | B1 | 22.5 | 8 | 5.300 | 5.545 | 5.304 |

| DS7 | B2 | 18.0 | 9 | 4.863 | 4.863 | 4.863 |

| DS8 | B2 | 18.5 | 9 | 4.900 | 4.949 | 4.903 |

| DS9 | B2 | 19.0 | 9 | 4.943 | 5.056 | 4.946 |

| DS10 | B2 | 19.5 | 9 | 4.997 | 5.185 | 5.002 |

| DS11 | B3 | 16.0 | 10 | 4.657 | 4.647 | unfeasible |

| DS12 | B3 | 16.5 | 10 | 4.696 | 4.724 | 4.698 |

| DS13 | B3 | 17.0 | 10 | 4.736 | 4.831 | 4.740 |

| DS14 | B4 | 18.0 | 9 | 4.863 | 4.863 | 4.863 |

| DS15 | B4 | 18.5 | 9 | 4.900 | 4.949 | 4.903 |

| DS16 | B4 | 19.0 | 9 | 4.943 | 5.056 | 4.946 |

| DS17 | B4 | 19.5 | 9 | 4.997 | 5.185 | 5.002 |

| DS18 | B5 | 16.0 | 10 | 4.657 | 4.647 | unfeasible |

| DS19 | B5 | 16.5 | 10 | 4.696 | 4.724 | 4.698 |

| DS20 | B5 | 17.0 | 10 | 4.736 | 4.831 | 4.740 |

| DS21 | B6 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.498 | 4.486 | unfeasible |

| DS22 | B6 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.541 | 4.570 | 4.543 |

| DS23 | B7 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.391 | 4.392 | 4.391 |

| DS24 | B8 | 16.0 | 10 | 4.657 | 4.647 | unfeasible |

| DS25 | B8 | 16.5 | 10 | 4.696 | 4.724 | 4.698 |

| DS26 | B8 | 17.0 | 10 | 4.736 | 4.831 | 4.740 |

| DS27 | B9 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.498 | 4.486 | unfeasible |

| DS28 | B9 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.541 | 4.570 | 4.543 |

| DS29 | B10 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.391 | 4.392 | 4.391 |

| DS30 | B11 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.284 | 4.290 | 4.286 |

| DS31 | B12 | 16.0 | 10 | 4.657 | 4.647 | unfeasible |

| DS32 | B12 | 16.5 | 10 | 4.696 | 4.724 | 4.698 |

| DS33 | B12 | 17.0 | 10 | 4.736 | 4.831 | 4.740 |

| DS34 | B13 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.498 | 4.486 | unfeasible |

| DS35 | B13 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.541 | 4.570 | 4.543 |

| DS36 | B14 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.391 | 4.392 | 4.391 |

| DS37 | B15 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.284 | 4.290 | 4.286 |

| DS38 | B16 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.498 | 4.486 | unfeasible |

| DS39 | B16 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.541 | 4.570 | 4.543 |

| DS40 | B17 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.391 | 4.392 | 4.391 |

| DS41 | B18 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.284 | 4.290 | 4.286 |

| DS42 | B19 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.498 | 4.486 | unfeasible |

| DS43 | B19 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.541 | 4.570 | 4.543 |

| DS44 | B20 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.391 | 4.392 | 4.391 |

| DS45 | B21 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.284 | 4.290 | 4.286 |

| DS46 | B22 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.391 | 4.392 | 4.391 |

| DS47 | B23 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.284 | 4.290 | 4.286 |

| DS48 | B24 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.391 | 4.392 | 4.391 |

| DS49 | B25 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.284 | 4.290 | 4.286 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Rolling Stock Scenario | Hplan (min) | NC (#) | Variation in Average Objective Function Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Time Optimal) (%) | (Optimised ESS) (%) | (Non-Optimised ESS) (%) | ||||

| DS1 | B1 | 20.0 | 8 | 3.61% | 3.39% | unfeasible |

| DS2 | B1 | 20.5 | 8 | 4.60% | 4.93% | 4.62% |

| DS3 | B1 | 21.0 | 8 | 5.51% | 6.74% | 5.54% |

| DS4 | B1 | 21.5 | 8 | 6.43% | 6.78% | 6.49% |

| DS5 | B1 | 22.0 | 8 | 7.29% | 10.87% | 7.38% |

| DS6 | B1 | 22.5 | 8 | 8.29% | 13.31% | 8.38% |

| DS7 | B2 | 18.0 | 9 | −0.63% | −0.63% | −0.63% |

| DS8 | B2 | 18.5 | 9 | 0.13% | 1.13% | 0.18% |

| DS9 | B2 | 19.0 | 9 | 0.99% | 3.31% | 1.07% |

| DS10 | B2 | 19.5 | 9 | 2.10% | 5.95% | 2.21% |

| DS11 | B3 | 16.0 | 10 | −4.84% | −5.05% | unfeasible |

| DS12 | B3 | 16.5 | 10 | −4.04% | −3.48% | −4.01% |

| DS13 | B3 | 17.0 | 10 | −3.23% | −1.30% | −3.15% |

| DS14 | B4 | 18.0 | 9 | −0.63% | −0.63% | −0.63% |

| DS15 | B4 | 18.5 | 9 | 0.13% | 1.13% | 0.18% |

| DS16 | B4 | 19.0 | 9 | 0.99% | 3.31% | 1.07% |

| DS17 | B4 | 19.5 | 9 | 2.10% | 5.95% | 2.21% |

| DS18 | B5 | 16.0 | 10 | −4.84% | −5.05% | unfeasible |

| DS19 | B5 | 16.5 | 10 | −4.04% | −3.48% | −4.01% |

| DS20 | B5 | 17.0 | 10 | −3.23% | −1.30% | −3.15% |

| DS21 | B6 | 14.5 | 11 | −8.09% | −8.33% | unfeasible |

| DS22 | B6 | 15.0 | 11 | −7.21% | −6.63% | −7.17% |

| DS23 | B7 | 13.5 | 12 | −10.28% | −10.27% | −10.27% |

| DS24 | B8 | 16.0 | 10 | −4.84% | −5.05% | unfeasible |

| DS25 | B8 | 16.5 | 10 | −4.04% | −3.48% | −4.01% |

| DS26 | B8 | 17.0 | 10 | −3.23% | −1.30% | −3.15% |

| DS27 | B9 | 14.5 | 11 | −8.09% | −8.33% | unfeasible |

| DS28 | B9 | 15.0 | 11 | −7.21% | −6.63% | −7.17% |

| DS29 | B10 | 13.5 | 12 | −10.28% | −10.27% | −10.27% |

| DS30 | B11 | 12.5 | 13 | −12.45% | −12.34% | −12.43% |

| DS31 | B12 | 16.0 | 10 | −4.84% | −5.05% | unfeasible |

| DS32 | B12 | 16.5 | 10 | −4.04% | −3.48% | −4.01% |

| DS33 | B12 | 17.0 | 10 | −3.23% | −1.30% | −3.15% |

| DS34 | B13 | 14.5 | 11 | −8.09% | −8.33% | unfeasible |

| DS35 | B13 | 15.0 | 11 | −7.21% | −6.63% | −7.17% |

| DS36 | B14 | 13.5 | 12 | −10.28% | −10.27% | −10.27% |

| DS37 | B15 | 12.5 | 13 | −12.45% | −12.34% | −12.43% |

| DS38 | B16 | 14.5 | 11 | −8.09% | −8.33% | unfeasible |

| DS39 | B16 | 15.0 | 11 | −7.21% | −6.63% | −7.17% |

| DS40 | B17 | 13.5 | 12 | −10.28% | −10.27% | −10.27% |

| DS41 | B18 | 12.5 | 13 | −12.45% | −12.34% | −12.43% |

| DS42 | B19 | 14.5 | 11 | −8.09% | −8.33% | unfeasible |

| DS43 | B19 | 15.0 | 11 | −7.21% | −6.63% | −7.17% |

| DS44 | B20 | 13.5 | 12 | −10.28% | −10.27% | −10.27% |

| DS45 | B21 | 12.5 | 13 | −12.45% | −12.34% | −12.43% |

| DS46 | B22 | 13.5 | 12 | −10.28% | −10.27% | −10.27% |

| DS47 | B23 | 12.5 | 13 | −12.45% | −12.34% | −12.43% |

| DS48 | B24 | 13.5 | 12 | −10.28% | −10.27% | −10.27% |

| DS49 | B25 | 12.5 | 13 | −12.45% | −12.34% | −12.43% |

References

- Cartenì, A. Accessibility indicators for freight transport terminals. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2014, 39, 7647–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartenì, A. Urban sustainable mobility. Part 1: Rationality in transport planning. Transp. Probl. 2014, 9, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cartenì, A. Urban sustainable mobility. Part 2: Simulation models and impacts estimation. Transp. Probl. 2015, 10, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M. The impact of urban transit systems on property values: A model and some evidences from the city of Naples. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 1767149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M. Improving equity of urban transit systems with the adoption of origin-destination based taxi fares. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2018, 64, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CENELEC. EN 50126-1: Railway Applications—Specification and Demonstration of Reliability, Availability, Maintainability and Safety (RAMS); European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). IEC 61508: Functional Safety of Electrical/Electronic/Programmable Electronic Safety-Related Systems—Part 4: Definitions and Abbreviations; International Electrotechnical Commission: Genève, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, G. RAMS Analysis of Railway Track Infrastructure. Master’s Thesis, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, A.P. Maintenance Decision Support Models for Railway Infrastructure Using RAMS & LCC Analyses. Ph.D. Thesis, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.G. RAMS Management of Railway Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.K. RAMS management for a complex railway system: A case study. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Applied Reliability Symposium, Bangalore, India, 12–14 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Praticò, F.; Giunta, M. An integrative approach RAMS-LCC to support decision on design and maintenance of rail track. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference Environmental Engineering, Vilnius, Lithuania, 27–28 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mahboob, Q.; Zio, E. Handbook of RAMS in Railway Systems: Theory and Practice; CRC Press by Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Louwerse, I.; Huisman, D. Adjusting a railway timetable in case of partial or complete blockades. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 235, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Kroon, L.; Veelenturf, L.P.; Wagenaar, J.C. Real-time high-speed train rescheduling in case of a complete blockage. Transport. Res. B-Meth. 2015, 78, 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmus, M.S.; Takai, S.; Söylemez, M.T. Fault diagnosis in fixed-block railway signaling systems: A discrete event systems approach. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. 2014, 9, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botte, M.; D’Acierno, L.; Montella, B.; Placido, A. A stochastic approach for assessing intervention strategies in the case of metro system failures. In Proceedings of the 2015 AEIT International Annual Conference, Naples, Italy, 14–16 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Botte, M.; Puca, D.; Montella, B.; D’Acierno, L. An innovative methodology for managing service disruptions on regional rail lines. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference Environmental Engineering, Vilnius, Lithuania, 27–28 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, W.; Meng, L.; Veelenturf, L.P.; Long, S.; Corman, F.; Niu, X. Optimal reassignment of passengers to trains following a broken train. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Rail Transport (IEEE ICIRT 2018), Marina Bay Sands, Singapore, 12–14 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D’Acierno, L.; Gallo, M.; Montella, B.; Placido, A. The definition of a model framework for managing rail systems in the case of breakdowns. In Proceedings of the 16th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (IEEE ITSC 2013), The Hague, The Netherlands, 6–9 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- D’Acierno, L.; Placido, A.; Botte, M.; Gallo, M.; Montella, B. Defining robust recovery solutions for preserving service quality during rail/metro systems failure. Int. J. Supply Oper. Manag. 2016, 3, 1351–1372. [Google Scholar]

- D’Acierno, L.; Placido, A.; Botte, M.; Montella, B. A methodological approach for managing rail disruptions with different perspectives. Int. J. Math. Models Methods Appl. Sci. 2016, 10, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, A.; Kroon, L.; Monaci, M.; Peeters, M.; Toth, P. Passenger Railway Optimization. In Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science; North Holland Publishing Company: North Holland, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 14, pp. 129–187. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, H.J.; Chen, C.S.; Lin, C.H.; Hsieh, C.H.; Ho, C.Y. Design of optimal coasting speed for saving social cost in mass rapid transit systems. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Deregulation and Restructuring and Power Technologies (DRPT 2008), Nianjing, China, 6–9 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Martinis, V.; Weidmann, U.; Gallo, M. Towards a simulation-based framework for evaluating energy-efficient solutions in train operation. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2014, 135, 721–732. [Google Scholar]

- D’Acierno, L.; Botte, M.; Montella, B. An analytical approach for determining reserve times on metro systems. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering (IEEE EEEIC 2017) and 1st Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (I&CPS 2017), Milan, Italy, 6–9 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guastafierro, A.; Lauro, G.; Pagano, M.; Roscia, M. A method for optimizing coasting phases in railway speed profiles: An application to an Italian route. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electrical Systems for Aircraft, Railway, Ship Propulsion and Road Vehicles & International Transportation Electrification Conference (ESARS ITEC 2016), Toulouse, France, 2–4 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, K.; Karamancioglu, A. Energy efficient motion control for a light rail vehicle using the big bang big crunch algorithm. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepmaker, G.; Goverde, R.M.P. The interplay between energy-efficient train control and scheduled running time supplements. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2015, 5, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Goverde, R.M.P. Multi-train trajectory optimization for energy-efficient timetabling. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 272, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botte, M.; D’Acierno, L. Dispatching and rescheduling tasks and their interactions with travel demand and the energy domain: Models and algorithms. Urban Rail Transit 2018, 4, 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acierno, L.; Botte, M.; Gallo, M.; Montella, B. Defining reserve times for metro systems: An analytical approach. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 5983250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gil, A.; Palacin, R.; Batty, P. Sustainable urban rail systems: Strategies and technologies for optimal management of regenerative braking energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 75, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Kim, K.T.; Han, M.S. A model and approaches for synchronized energy saving in timetabling. In Proceedings of the 9th World Congress on Railway Research (WCRR 2011), Lille, France, 22–26 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Li, X.; Gao, Z.; Wang, H.; Tang, T. A cooperative scheduling model for timetable optimization in subway systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. 2013, 14, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornic, D. Efficient recovery of braking energy through a reversible dc substation. In Proceedings of the Electrical Systems for Aircraft, Railway and Ship Propulsion (ESARS 2010), Bologna, Italy, 19–21 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ibaiondo, H.; Romo, A. Kinetic energy recovery on railway systems with feedback to the grid. In Proceedings of the 14th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (EPE-PEMC 2010), Ohrid, Macedonia, 6–8 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Romo, L.; Turner, D.; Ng, L.S.B. Cutting traction power costs with wayside energy storage systems in rail transit systems. In Proceedings of the 2005 Joint Rail Conference (JRC 2005), Pueblo, CO, USA, 16–18 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ghavihaa, N.; Campilloa, J.; Bohlinb, M.; Dahlquista, E. Review of application of energy storage devices in railway transportation. Energy Proced. 2017, 105, 4561–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, D.; Tricoli, P. Speed-based state-of-charge tracking control for metro trains with onboard supercapacitors. IEEE Trans. Power Electr. 2012, 27, 2129–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Yuan, T.; Yang, J.; He, H. Simulation of braking energy recovery for the metro vehicles based on the traction experiment system. Simulation 2017, 93, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah, M.; Asadi, M.; Moghbeli, H.; Dehnavi, G.R. Energy management and control system of DC-DC converter with super-capacitor and battery for recovering of train kinetic energy. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 0174103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acierno, L.; Botte, M. The implementation of energy-saving strategies in the case of limitation in rolling stock availability. In Proceedings of the 19th IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering (IEEE EEEIC 2019) and 3rd Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (I&CPS 2019), Genoa, Italy, 11–14 June 2019; pp. 380–385. [Google Scholar]

- D’Acierno, L.; Botte, M. A passenger-oriented optimization model for implementing energy-saving strategies in railway contexts. Energies 2018, 11, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union of Railways (UIC). UIC CODE 451-1: Timetable Recovery Margins to Guarantee Timekeeping—Recovery Margins; UIC: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzillo Iacono, M.; Martinez, M.; Mangia, G.; Galdiero, C. Knowledge creation and inter-organisational relationships: The development of innovation in the railway industry. J. Knowl. Manag. 2012, 16, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariscotti, A.; Marrese, A.; Pasquino, N.; Schiano Lo Moriello, R. Time and frequency characterization of radiated disturbance in telecommunication bands due to pantograph arcing. Measurement 2013, 46, 4342–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A. Affecting atmospheric emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases within the electricity industry (In Italian). In Technical Report 257/2017, National Institute for Environmental Protection and Research; ISPRA: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saltelli, A.; Ratto, M.; Andres, T.; Campolongo, F.; Cariboni, J.; Gatelli, D.; Saisana, M.; Tarantola, S. Global Sensitività Analysis: The Primer; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

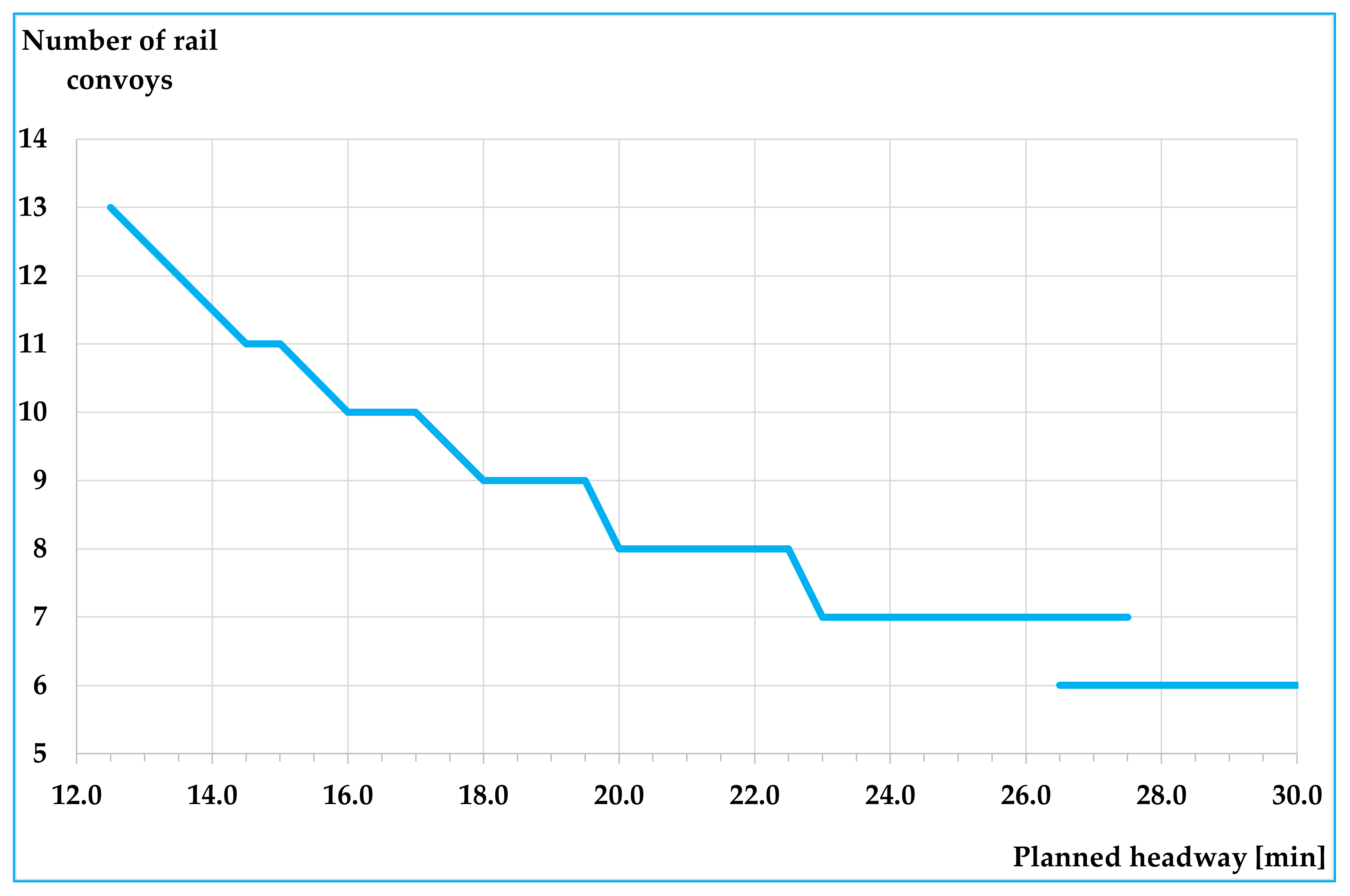

| Hplan (min) | 12.5 | 13.5 | 14.5 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 16.5 | 17.0 | 18.0 | 18.5 | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.0 |

| NC (#) | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| Hplan (min) | 20.5 | 21.0 | 21.5 | 22.0 | 22.5 | 23.0 | 23.5 | 24.0 | 24.5 | 25.0 | 25.5 | 26.0 |

| NC (#) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Hplan (min) | 26.5 | 26.5 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 27.5 | 27.5 | 28.0 | 28.5 | 29.0 | 29.5 | 30.0 | |

| NC (#) | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Rolling Stock Scenario | Single-Header Convoys | Double-Header Convoys | Triple-Header Convoys | Total Rail Convoys | Number of Railcars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 27 |

| A2 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 11 | 27 |

| A3 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 27 |

| A4 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 27 |

| A5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 27 |

| A6 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 12 | 27 |

| A7 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 13 | 27 |

| A8 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 | 27 |

| A9 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 27 |

| A10 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 13 | 27 |

| A11 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 27 |

| A12 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 12 | 27 |

| A13 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 13 | 27 |

| A14 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 12 | 27 |

| A15 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 27 |

| A16 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 27 |

| A17 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 13 | 27 |

| A18 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 27 |

| A19 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 27 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Rolling Stock Scenario | Hplan (min) | NC (#) | TLTTO (min) | Capserv (pax/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS1 | A1 | 18.0 | 9 | 3.55 | 4500 |

| OS2 | A1 | 18.5 | 9 | 8.05 | 4378 |

| OS3 | A1 | 19.0 | 9 | 12.55 | 4263 |

| OS4 | A1 | 19.5 | 9 | 17.05 | 4154 |

| OS5 | A2 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4571 |

| OS6 | A2 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 4418 |

| OS7 | A3 | 16.0 | 10 | 1.55 | 4556 |

| OS8 | A3 | 16.5 | 10 | 6.55 | 4418 |

| OS9 | A3 | 17.0 | 10 | 11.55 | 4288 |

| OS10 | A4 | 16.0 | 10 | 1.55 | 4556 |

| OS11 | A4 | 16.5 | 10 | 6.55 | 4418 |

| OS12 | A4 | 17.0 | 10 | 11.55 | 4288 |

| OS13 | A5 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4571 |

| OS14 | A5 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 4418 |

| OS15 | A6 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4500 |

| OS16 | A7 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 4486 |

| OS17 | A8 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4571 |

| OS18 | A8 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 4418 |

| OS19 | A9 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4500 |

| OS20 | A10 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 4486 |

| OS21 | A11 | 14.5 | 11 | 1.05 | 4571 |

| OS22 | A11 | 15.0 | 11 | 6.55 | 4418 |

| OS23 | A12 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4500 |

| OS24 | A13 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 4486 |

| OS25 | A14 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4500 |

| OS26 | A15 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 4486 |

| OS27 | A16 | 13.5 | 12 | 3.55 | 4500 |

| OS28 | A17 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 4486 |

| OS29 | A18 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 4486 |

| OS30 | A19 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.05 | 4486 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Speed Limit in the Outward/Return Trip (km/h) | Average Passenger Running/Waiting Time (min/pax) | Daily Runs (Railcars-km) | Daily Energy Consumption (MWh/day) | Average Objective Function Value (€/pax) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS1 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 9.0 | 13,541 | 62.82 | 4.901 |

| OS2 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 9.2 | 13,157 | 61.08 | 4.937 |

| OS3 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 9.5 | 12,774 | 59.27 | 4.978 |

| OS4 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 9.8 | 12,519 | 58.08 | 5.032 |

| OS5 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 7.2 | 13,692 | 63.55 | 4.536 |

| OS6 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 7.5 | 13,274 | 61.61 | 4.578 |

| OS7 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 8.0 | 13,796 | 64.01 | 4.695 |

| OS8 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 8.2 | 13,336 | 61.88 | 4.733 |

| OS9 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 8.5 | 12,876 | 59.74 | 4.772 |

| OS10 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 8.0 | 13,796 | 64.01 | 4.695 |

| OS11 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 8.2 | 13,336 | 61.88 | 4.733 |

| OS12 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 8.5 | 12,876 | 59.74 | 4.772 |

| OS13 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 7.2 | 13,692 | 63.55 | 4.536 |

| OS14 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 7.5 | 13,274 | 61.61 | 4.578 |

| OS15 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.7 | 13,604 | 63.12 | 4.429 |

| OS16 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.2 | 13,442 | 62.37 | 4.322 |

| OS17 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 7.2 | 13,692 | 63.55 | 4.536 |

| OS18 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 7.5 | 13,274 | 61.61 | 4.578 |

| OS19 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.7 | 13,604 | 63.12 | 4.429 |

| OS20 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.2 | 13,442 | 62.37 | 4.322 |

| OS21 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 7.2 | 13,692 | 63.55 | 4.536 |

| OS22 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 7.5 | 13,274 | 61.61 | 4.578 |

| OS23 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.7 | 13,604 | 63.12 | 4.429 |

| OS24 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.2 | 13,442 | 62.37 | 4.322 |

| OS25 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.7 | 13,604 | 63.12 | 4.429 |

| OS26 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.2 | 13,442 | 62.37 | 4.322 |

| OS27 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.7 | 13,604 | 63.12 | 4.429 |

| OS28 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.2 | 13,442 | 62.37 | 4.322 |

| OS29 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.2 | 13,442 | 62.37 | 4.322 |

| OS30 | 90 / 90 | 32.2 / 6.2 | 13,442 | 62.37 | 4.322 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Speed Limit in the Outward/Return Trip (km/h) | Total Layover Time Used (min) | Average Passenger Running/Waiting Time (min/pax) | Daily Energy Consumed (MWh/day) | CO2 Reduction (t/day) | Average Objective Function Value (€/pax) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS1 | 70 / 71 | 3.33 | 32.9 / 9.0 | 50.68 | 5.94 | 4.894 |

| OS2 | 58 / 69 | 7.48 | 33.8 / 9.2 | 42.91 | 8.58 | 4.975 |

| OS3 | 53 / 63 | 11.77 | 34.8 / 9.5 | 37.89 | 10.45 | 5.079 |

| OS4 | 46 / 66 | 16.00 | 35.8 / 9.8 | 35.18 | 10.62 | 5.207 |

| OS5 | 77 / 82 | 0.93 | 32.4 / 7.2 | 57.93 | 2.75 | 4.521 |

| OS6 | 62 / 68 | 6.08 | 33.5 / 7.5 | 44.68 | 8.03 | 4.597 |

| OS7 | 79 / 76 | 1.43 | 32.5 / 8.0 | 56.60 | 3.37 | 4.681 |

| OS8 | 67 / 63 | 6.03 | 33.5 / 8.2 | 45.01 | 8.00 | 4.751 |

| OS9 | 62 / 55 | 10.87 | 34.6 / 8.5 | 38.20 | 10.28 | 4.854 |

| OS10 | 79 / 76 | 1.43 | 32.5 / 8.0 | 56.60 | 3.37 | 4.681 |

| OS11 | 67 / 63 | 6.03 | 33.5 / 8.2 | 45.01 | 8.00 | 4.751 |

| OS12 | 62 / 55 | 10.87 | 34.6 / 8.5 | 38.20 | 10.28 | 4.854 |

| OS13 | 77 / 82 | 0.93 | 32.4 / 7.2 | 57.93 | 2.75 | 4.521 |

| OS14 | 62 / 68 | 6.08 | 33.5 / 7.5 | 44.68 | 8.03 | 4.597 |

| OS15 | 71 / 70 | 3.37 | 32.9 / 6.7 | 50.65 | 5.89 | 4.422 |

| OS16 | 71 / 68 | 3.77 | 33.0 / 6.2 | 49.55 | 6.27 | 4.320 |

| OS17 | 77 / 82 | 0.93 | 32.4 / 7.2 | 57.93 | 2.75 | 4.521 |

| OS18 | 62 / 68 | 6.08 | 33.5 / 7.5 | 44.68 | 8.03 | 4.597 |

| OS19 | 71 / 70 | 3.37 | 32.9 / 6.7 | 50.65 | 5.89 | 4.422 |

| OS20 | 71 / 68 | 3.77 | 33.0 / 6.2 | 49.55 | 6.27 | 4.320 |

| OS21 | 77 / 82 | 0.93 | 32.4 / 7.2 | 57.93 | 2.75 | 4.521 |

| OS22 | 62 / 68 | 6.08 | 33.5 / 7.5 | 44.68 | 8.03 | 4.597 |

| OS23 | 71 / 70 | 3.37 | 32.9 / 6.7 | 50.65 | 5.89 | 4.422 |

| OS24 | 71 / 68 | 3.77 | 33.0 / 6.2 | 49.55 | 6.27 | 4.320 |

| OS25 | 71 / 70 | 3.37 | 32.9 / 6.7 | 50.65 | 5.89 | 4.422 |

| OS26 | 71 / 68 | 3.77 | 33.0 / 6.2 | 49.55 | 6.27 | 4.320 |

| OS27 | 71 / 70 | 3.37 | 32.9 / 6.7 | 50.65 | 5.89 | 4.422 |

| OS28 | 71 / 68 | 3.77 | 33.0 / 6.2 | 49.55 | 6.27 | 4.320 |

| OS29 | 71 / 68 | 3.77 | 33.0 / 6.2 | 49.55 | 6.27 | 4.320 |

| OS30 | 71 / 68 | 3.77 | 33.0 / 6.2 | 49.55 | 6.27 | 4.320 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Rolling Stock Scenario | Hplan (min) | NC (#) | Average Objective Function Value (TO) (€/pax) | Average Objective Function Value (ESS) (€/pax) | Objective Function Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS1 | A1 | 18.0 | 9 | 4.901 | 4.894 | −0.144% |

| OS2 | A1 | 18.5 | 9 | 4.937 | 4.975 | 0.769% |

| OS3 | A1 | 19.0 | 9 | 4.978 | 5.079 | 2.023% |

| OS4 | A1 | 19.5 | 9 | 5.032 | 5.207 | 3.483% |

| OS5 | A2 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.536 | 4.521 | −0.330% |

| OS6 | A2 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.578 | 4.597 | 0.404% |

| OS7 | A3 | 16.0 | 10 | 4.695 | 4.681 | −0.306% |

| OS8 | A3 | 16.5 | 10 | 4.733 | 4.751 | 0.379% |

| OS9 | A3 | 17.0 | 10 | 4.772 | 4.854 | 1.713% |

| OS10 | A4 | 16.0 | 10 | 4.695 | 4.681 | −0.306% |

| OS11 | A4 | 16.5 | 10 | 4.733 | 4.751 | 0.379% |

| OS12 | A4 | 17.0 | 10 | 4.772 | 4.854 | 1.713% |

| OS13 | A5 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.536 | 4.521 | −0.330% |

| OS14 | A5 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.578 | 4.597 | 0.404% |

| OS15 | A6 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.429 | 4.422 | −0.147% |

| OS16 | A7 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.322 | 4.320 | −0.055% |

| OS17 | A8 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.536 | 4.521 | −0.330% |

| OS18 | A8 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.578 | 4.597 | 0.404% |

| OS19 | A9 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.429 | 4.422 | −0.147% |

| OS20 | A10 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.322 | 4.320 | −0.055% |

| OS21 | A11 | 14.5 | 11 | 4.536 | 4.521 | −0.330% |

| OS22 | A11 | 15.0 | 11 | 4.578 | 4.597 | 0.404% |

| OS23 | A12 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.429 | 4.422 | −0.147% |

| OS24 | A13 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.322 | 4.320 | −0.055% |

| OS25 | A14 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.429 | 4.422 | −0.147% |

| OS26 | A15 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.322 | 4.320 | −0.055% |

| OS27 | A16 | 13.5 | 12 | 4.429 | 4.422 | −0.147% |

| OS28 | A17 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.322 | 4.320 | −0.055% |

| OS29 | A18 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.322 | 4.320 | −0.055% |

| OS30 | A19 | 12.5 | 13 | 4.322 | 4.320 | −0.055% |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Rolling Stock Scenario | Hplan (min) | NC (#) | TLTTO (min) | Capserv (pax/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | 8 triple-header trains | 20.0 | 8 | 1.55 | 4050 |

| DS2 | 8 triple-header trains | 20.5 | 8 | 5.55 | 3951 |

| DS3 | 8 triple-header trains | 21.0 | 8 | 9.55 | 3857 |

| DS4 | 8 triple-header trains | 21.5 | 8 | 13.55 | 3767 |

| DS5 | 8 triple-header trains | 22.0 | 8 | 17.55 | 3682 |

| DS6 | 8 triple-header trains | 22.5 | 8 | 21.55 | 3600 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Hplan (min) | NC (#) | Average Objective Function Value (Time-Optimal) (€/pax) | Average Objective Function Value (Optimised ESS) €/pax) | Average Objective Function Value (Non-Optimised ESS) (€/pax) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | 20.0 | 8 | 5.071 | 5.060 | unfeasible |

| DS2 | 20.5 | 8 | 5.119 | 5.135 | 5.120 |

| DS3 | 21.0 | 8 | 5.163 | 5.224 | 5.165 |

| DS4 | 21.5 | 8 | 5.209 | 5.226 | 5.212 |

| DS5 | 22.0 | 8 | 5.251 | 5.426 | 5.255 |

| DS6 | 22.5 | 8 | 5.300 | 5.545 | 5.304 |

| Service Configuration Scenario | Hplan (min) | N (#) | Variation in Average Objective Function Value (Time Optimal) (%) | Variation in Average Objective Function Value (Optimised ESS) (%) | Variation in Average Objective Function Value (Non-Optimised ESS) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | 20.0 | 8 | 3.61% | 3.39% | unfeasible |

| DS2 | 20.5 | 8 | 4.60% | 4.93% | 4.62% |

| DS3 | 21.0 | 8 | 5.51% | 6.74% | 5.54% |

| DS4 | 21.5 | 8 | 6.43% | 6.78% | 6.49% |

| DS5 | 22.0 | 8 | 7.29% | 10.87% | 7.38% |

| DS6 | 22.5 | 8 | 8.29% | 13.31% | 8.38% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Acierno, L.; Botte, M. Optimising Frequency-Based Railway Services with a Limited Fleet Endowment: An Energy-Efficient Perspective. Energies 2020, 13, 2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13102403

D’Acierno L, Botte M. Optimising Frequency-Based Railway Services with a Limited Fleet Endowment: An Energy-Efficient Perspective. Energies. 2020; 13(10):2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13102403

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Acierno, Luca, and Marilisa Botte. 2020. "Optimising Frequency-Based Railway Services with a Limited Fleet Endowment: An Energy-Efficient Perspective" Energies 13, no. 10: 2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13102403

APA StyleD’Acierno, L., & Botte, M. (2020). Optimising Frequency-Based Railway Services with a Limited Fleet Endowment: An Energy-Efficient Perspective. Energies, 13(10), 2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13102403