Sand Transport and Deposition Behaviour in Subsea Pipelines for Flow Assurance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Approaches

2.1. Governing Equations

2.2. Numerical Schemes

3. Results and Discussion

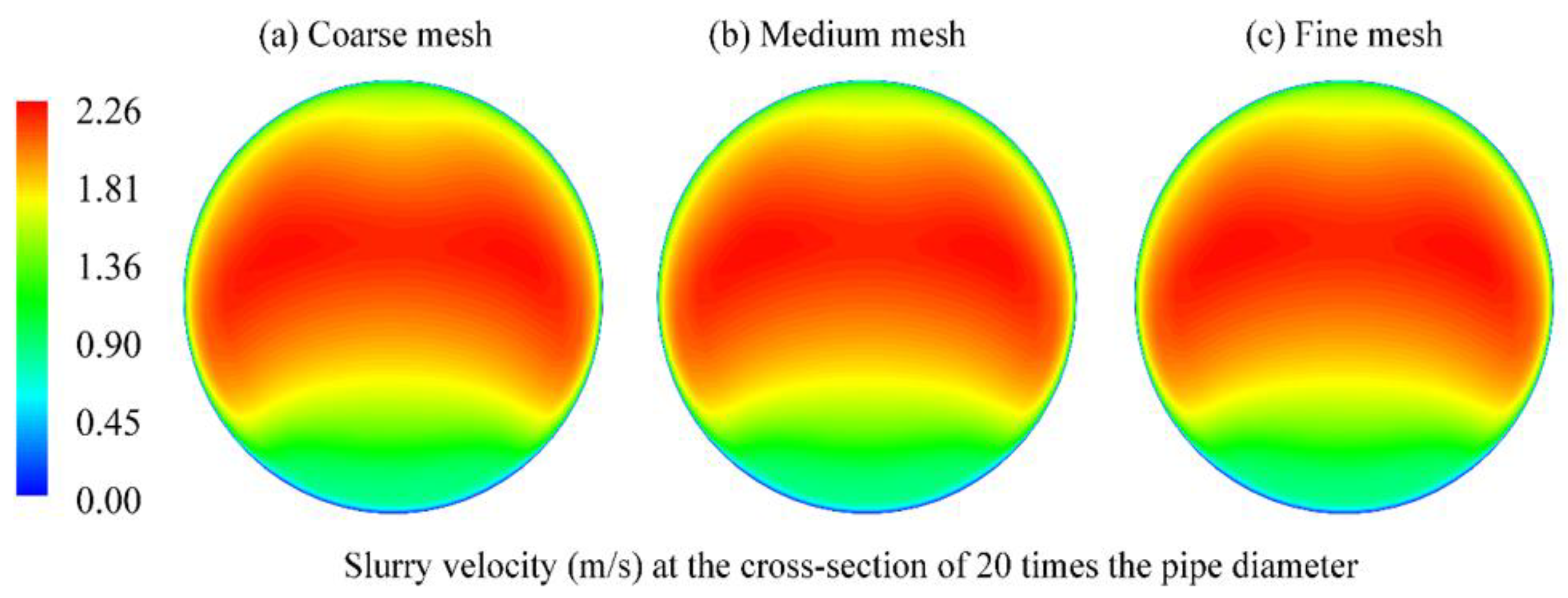

3.1. Model Validation

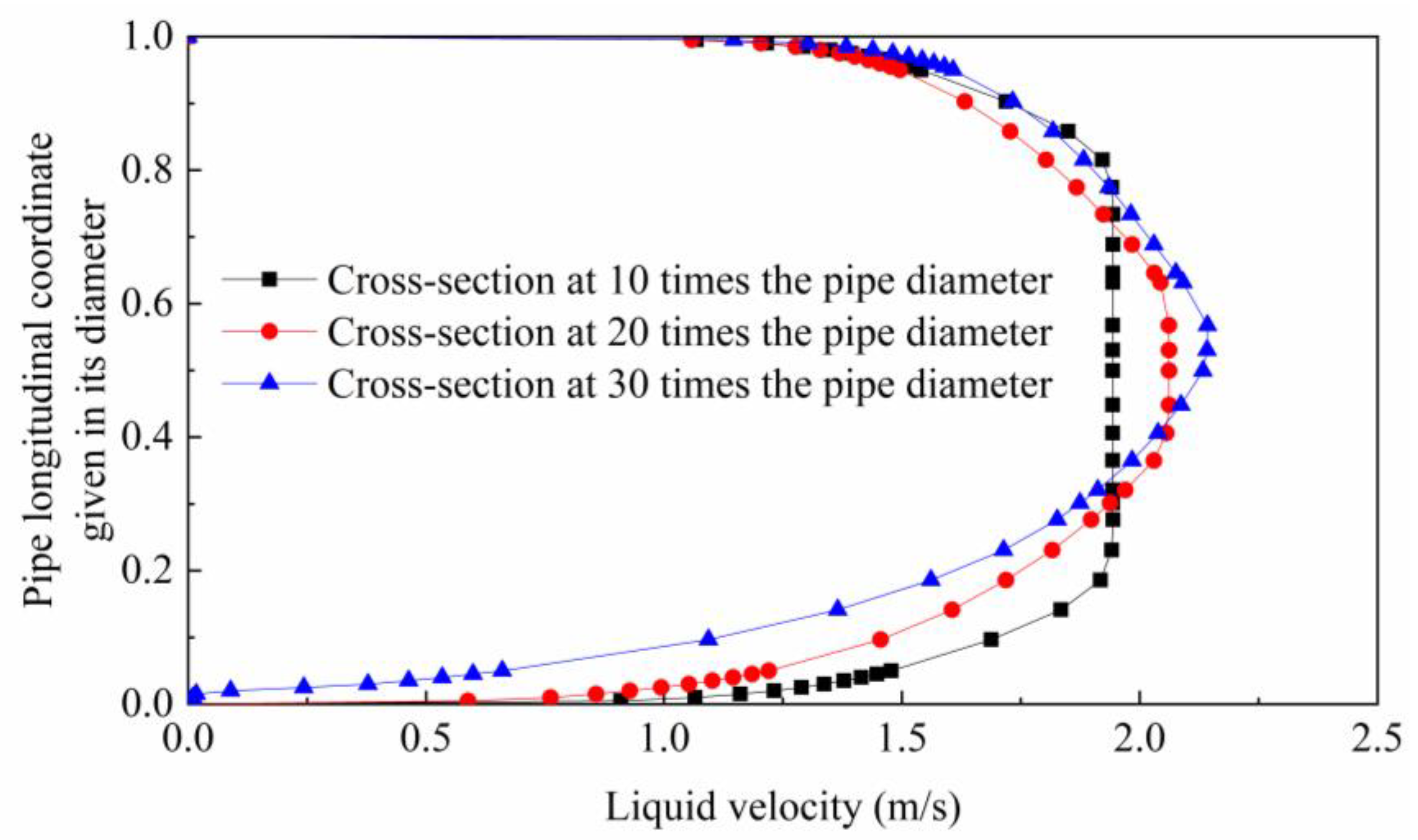

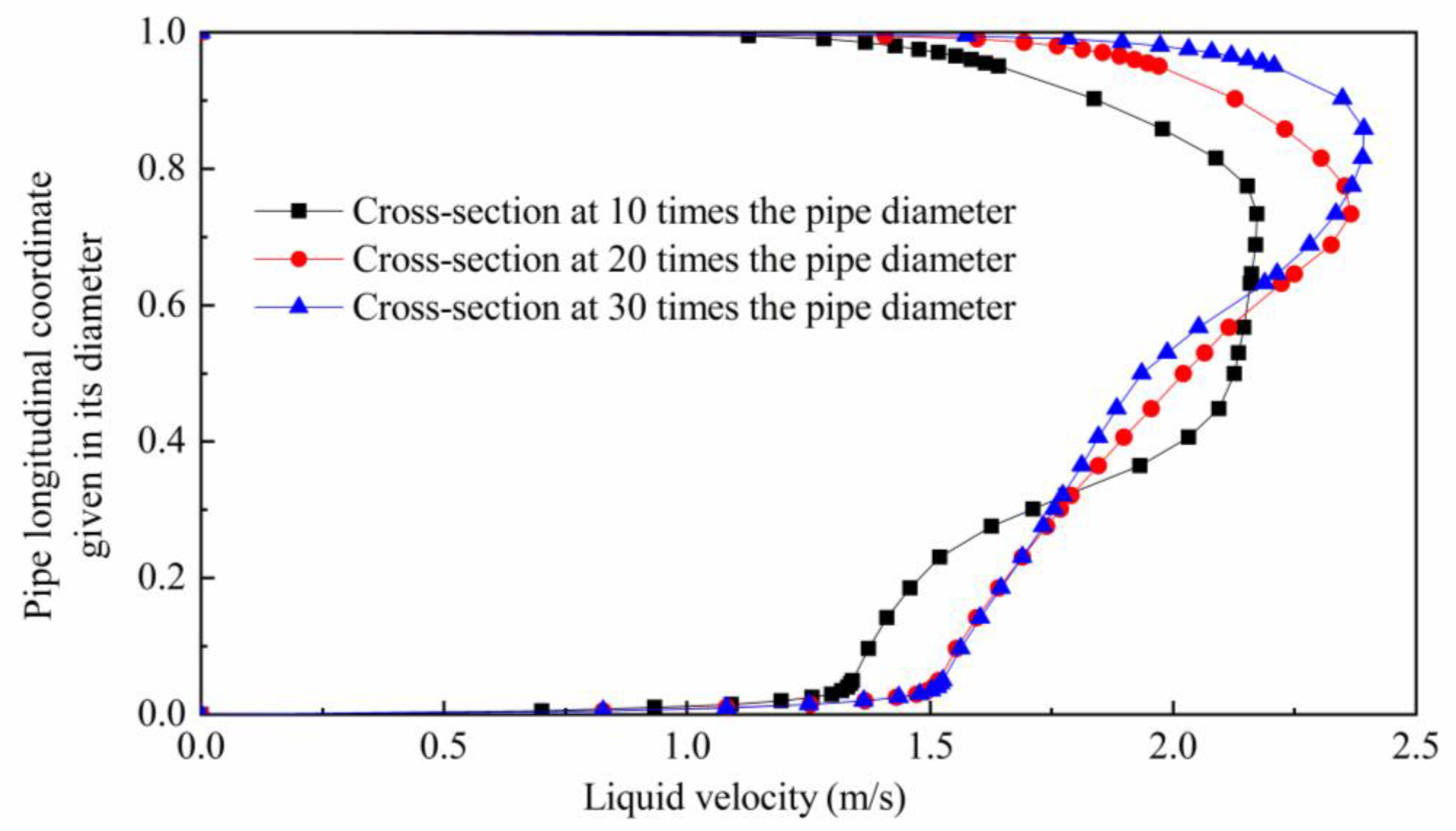

3.2. Slurry Velocity

3.3. Sand Concentration

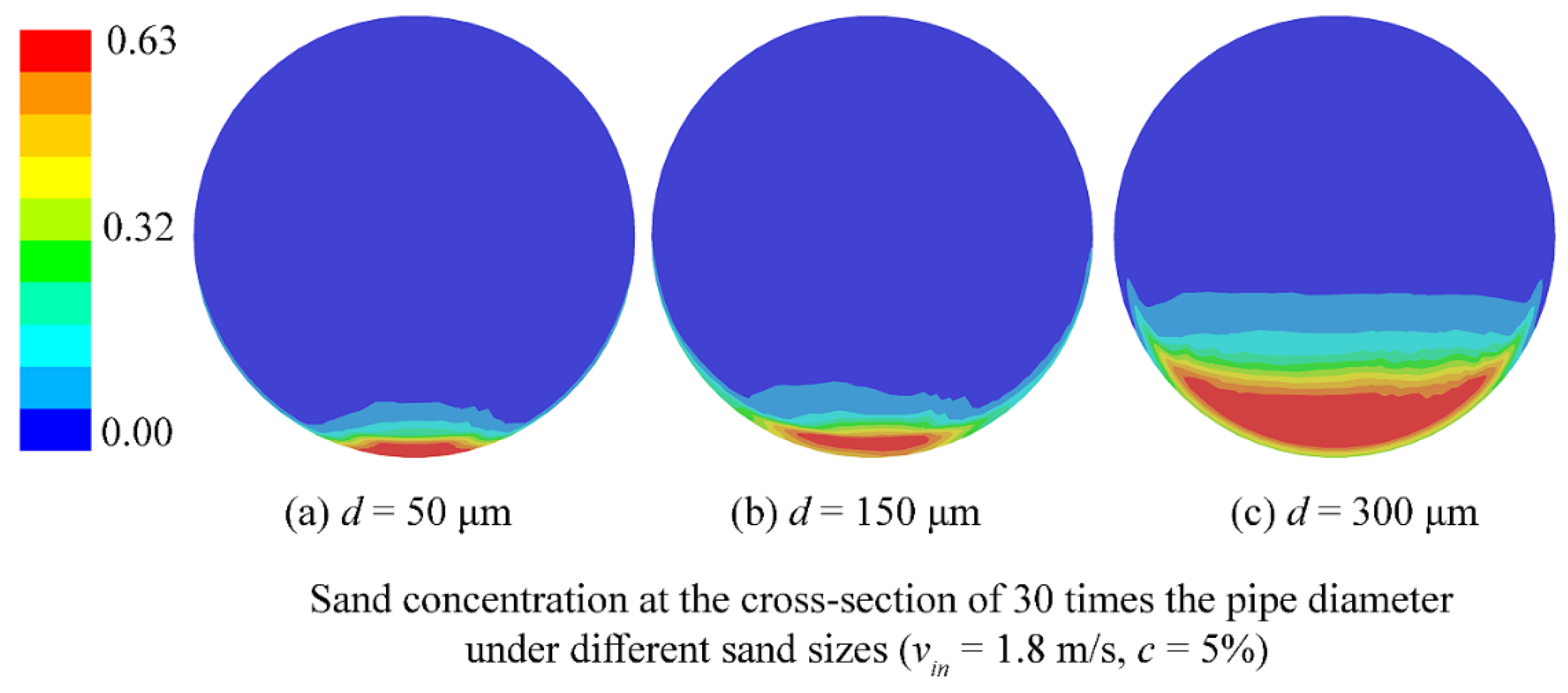

3.4. Effect of the Particle Size

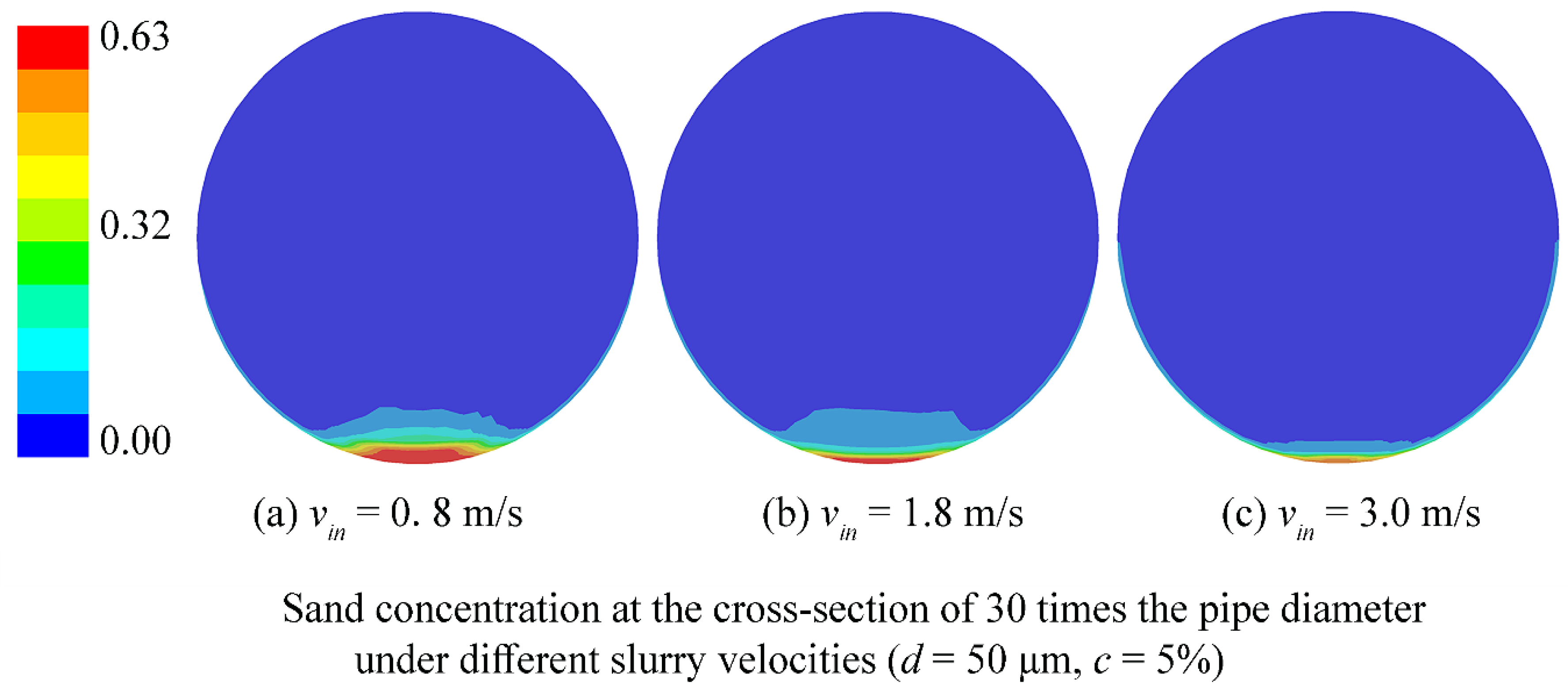

3.5. Effect of the Inlet Velocity

3.6. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dotto, G.L.; dos Santos, J.N.; Rosa, R.; Pinto, L.A.A.; Pavan, F.A.; Lima, E.C. Fixed bed adsorption of Methylene Blue by ultrasonic surface modified chitin supported on sand. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2005, 100, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, T.J. Transient multiphase flow: Past, present, and future with flow assurance perspective. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 4137–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorgani, E.; Al-Awadi, H.; Yan, W.; Al-Lababid, S.; Yeung, H.; Fairhurst, C.P. Viscosity effects on sand flow regimes and transport velocity in horizontal pipelines. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2018, 92, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlin, W.L.; Sexton, J.H.; Zumwalt, G.L. Sand transport experiments in thin fluids. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–26 September, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Guo, L.J.; Zhang, X.M. Liquid-solid separation phenomena of two-phase turbulent flow in curved pipes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2002, 45, 4995–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassai, M. Effectiveness and humidification capacity investigation of liquid-to-air membrane energy exchanger under low heat capacity ratios at winter air conditions. J. Therm. Sci. 2015, 24, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, P.; Granica, D.; Barnea, D. Slurry flow in horizontal pipes—Experimental and modeling. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1987, 13, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.G.; Shook, C.A. Concentration distributions of sand slurries in horizontal pipe flow. Part. Sci. Technol. 1994, 12, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.G.; Hill, K.B.; Mckibben, M.J.; Shook, C.A. Solids transport by laminar Newtonian flows. Powder Technol. 1999, 104, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, D.R.; Tomita, Y. Solids concentration profiles and pressure drop in pipeline flow of multisized particulate slurries. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2002, 28, 1697–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, D.R.; Tomita, Y. Comparative study of pressure drop in multisized particulate slurry flow through pipe and rectangular duct. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2003, 29, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, D.R.; Sato, K.; Toyota, T.; Funatsu, K.; Tomita, Y. Effect of particle size distribution on pressure drop and concentration profile in pipeline flow of highly concentrated slurry. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2005, 31, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, D.R.; Tomita, Y. Experimental investigation for near-wall lift of coarser particles in slurry pipeline using γ-ray densitometer. Powder Technol. 2007, 172, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Miska, S.Z.; Yu, M.; Takach, N.E.; Ahmed, R.M.; Zettner, C.M. Critical conditions for effective sand-sized solids transport in horizontal and high-angle wells. SPE Dril. Com. 2009, 24, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, K.; Hill, A.L.; McLaury, B.S.; Shirazi, S.A.; Cremaschi, S. Experimental study of low concentration sand transport in multiphase air–water horizontal pipelines. J. Energy Res. Technol. 2015, 137, 032908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, H.P.; Fairweather, M.; Peakall, J.; Hunter, T.N.; Mahmoud, B.; Biggs, S.R. Measurement of particle concentration in horizontal, multiphase pipe flow using acoustic methods: Limiting concentration and the effect of attenuation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 126, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roco, M.C.; Shook, C.A. Modeling of slurry flow: The effect of particle size. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1983, 61, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, Q.; Ali, S.M.; George, A.E.; Oguztoreli, M. Simulation of sand transport in a horizontal well. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Horizontal Well Technology, Calgary, AB, Canada, 18–20 November 1996; Richardson, Texas, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, J.; Skudarnov, P.V.; Lin, C.X.; Ebadian, M.A. Numerical investigations of liquid-solid slurry flows in a fully developed turbulent flow region. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2003, 24, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.X.; Ebadian, M.A. A numerical study of developing slurry flow in the entrance region of a horizontal pipe. Comput. Fluids 2008, 37, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, T.J. Sand transport modeling in multiphase pipelines. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 30 April–3 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.C.; Sanders, R.S.; Gillies, R.G.; Shook, C.A. Verification of the near-wall model for slurry flow. Powder Technol. 2010, 197, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messa, G.V.; Malin, M.; Malavasi, S. Numerical prediction of fully-suspended slurry flow in horizontal pipes. Powder Technol. 2014, 256, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.P.; Luo, Z.H.; Zheng, Z.W. Numerical simulation of liquid-solid two-phase flow in a tubular loop polymerization reactor. Powder Technol. 2010, 198, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassai, M. Experimental investigation on the effectiveness of sorption energy recovery wheel in ventilation system. Exp. Heat Transfer 2018, 31, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messa, G.V.; Malavasi, S. Improvements in the numerical prediction of fully-suspended slurry flow in horizontal pipes. Powder Technol. 2015, 270, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadinoto, K. Predicting turbulence modulations at different Reynolds numbers in dilute-phase turbulent liquid–particle flow simulations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 5297–5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, D.R.; Thinglas, T.; Tomita, Y.; Kuchii, S.; Tsukamoto, H. CFD modeling for pipeline flow of fine particles at high concentration. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2012, 43, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soepyan, F.B.; Cremaschi, S.; Sarica, C.; Subramani, H.J.; Kouba, G.E. Solids transport models comparison and fine-tuning for horizontal, low concentration flow in single-phase carrier fluid. AIChE J. 2014, 60, 76–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabirian, R.; Mohan, R.; Shoham, O.; Kouba, G. Critical sand deposition velocity for gas-liquid stratified flow in horizontal pipes. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, K.; McLaury, B.S.; Shirazi, S.A.; Cremaschi, S. The effect of viscosity on low concentration particle transport in single-phase (liquid) horizontal pipes. J. Energy Res. Technol. 2016, 138, 032902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, K.; McLaury, B.S.; Shirazi, S.A.; Cremaschi, S. Low concentration sand transport in multiphase viscous horizontal pipes: An experimental study and modeling guideline. AIChE J. 2016, 62, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabirian, R.; Arabnejad Khanouki, H.; Mohan, R.S.; Shoham, O. Numerical Simulation and Modeling of Critical Sand-Deposition Velocity for Solid/Liquid Flow. SPE Prod. Oper. 2018, 33, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabirian, R.; Mohan, R.; Shoham, O.; Kouba, G. Sand Transport in Slightly Upward Inclined Multiphase Flow. J. Energy Res. Technol. 2018, 140, 072901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebowei, R.; Hossain, M.; Islam, S.Z.; Droubi, M.G.; Oluyemi, G. Investigation of sand transport in an undulated pipe using computational fluid dynamics. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 162, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajemidupe, O.T.; Aliyu, A.M.; Baba, Y.D.; Archibong-Eso, A.; Yeung, H. Sand minimum transport conditions in gas–solid–liquid three-phase stratified flow in a horizontal pipe at low particle concentrations. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 143, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporini, M.; Marchetti, B.; Corvaro, F.; di Giovine, G.; Polonara, F.; Terenzi, A. Sand transport in multiphase flow mixtures in a horizontal pipeline: An experimental investigation. Petroleum 2019, 5, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporini, M.; Terenzi, A.; Marchetti, B.; Corvaro, F.; Polonara, F. On the numerical simulation of sand transport in liquid and multiphase pipelines. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 175, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS Fluent. 18.0 ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide 18.0; ANSYS Fluent: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yan, Y.; Ding, H.; Wen, C. Performance of supersonic steam ejectors considering the nonequilibrium condensation phenomenon for efficient energy utilisation. Appl. Energy 2019, 242, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Karvounis, N.; Walther, J.H.; Yan, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yang, Y. An efficient approach to separate CO2 using supersonic flows for carbon capture and storage. Appl. Energy 2019, 238, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lee, M.; Han, C. Hydraulic transport of sand-water mixtures in pipelines Part I. Experiment. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2008, 22, 2534–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Lababidi, S.; Yan, W.; Yeung, H. Sand transportations and deposition characteristics in multiphase flows in pipelines. J. Energy Res. Technol. 2012, 134, 034501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofei, T.N.; Ismail, A.Y. Eulerian-Eulerian simulation of particle-liquid slurry flow in horizontal pipe. J. Pet. Eng. 2016, 2016, 5743471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Sand Size (μm) | Sand Concentration (%) | Pipe Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dabirian et al. 2016 [30] | 45–600 | 0.025–1% | 97 |

| Najmi et al. 2016 [31] | 20–300 | 0–1% | 50 |

| Najmi et al. 2016 [32] | 150–300 | 0.01–0.1% | 50–100 |

| Dabirian et al. 2018 [33] | 150–600 | 0–1% | 50 |

| Dabirian et al. 2018 [34] | 45–600 | 0.025–1% | 97 |

| Tebowei et al. 2018 [35] | 255 | 0.04% | 100 |

| Fajemidupe et al. 2019 [36] | 212–800 | 0–0.006% | 50.4 |

| Leporini et al. 2019 [37] | 100–1100 | 0.0065–0.056% | 63 |

| Leporini et al. 2019 [38] | 45–600 | 0.00161–0.0538 | 50–100 |

| Grid Resolution | Slurry Velocity (m/s) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse mesh (121,080 cells) | 2.0233 | 2.24 |

| Medium mesh (203,490 cells) | 2.0614 | 0.40 |

| Fine mesh (466,820 cells) | 2.0697 | 0 |

| Numerical Inputs | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter of the Pipe (mm) | 200 |

| Length of the Pipe (mm) | 8000 |

| Sand size (μm) | 50, 300 |

| Sand concentration (%) | 5, 30 |

| Inlet velocity of the slurry flow | 1.8 |

| Numerical Inputs | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter of the Pipe (mm) | 200 |

| Length of the Pipe (mm) | 8000 |

| Sand size (μm) | 50, 150, 300 |

| Sand concentration (%) | 5 |

| Inlet velocity of the slurry flow | 1.8 |

| Numerical Inputs | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter of the Pipe (mm) | 200 |

| Length of the Pipe (mm) | 8000 |

| Sand size (μm) | 50 |

| Sand concentration (%) | 5 |

| Inlet velocity of the slurry flow | 0.8, 1.8, 3.0 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Peng, H.; Wen, C. Sand Transport and Deposition Behaviour in Subsea Pipelines for Flow Assurance. Energies 2019, 12, 4070. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12214070

Yang Y, Peng H, Wen C. Sand Transport and Deposition Behaviour in Subsea Pipelines for Flow Assurance. Energies. 2019; 12(21):4070. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12214070

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yan, Haoping Peng, and Chuang Wen. 2019. "Sand Transport and Deposition Behaviour in Subsea Pipelines for Flow Assurance" Energies 12, no. 21: 4070. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12214070

APA StyleYang, Y., Peng, H., & Wen, C. (2019). Sand Transport and Deposition Behaviour in Subsea Pipelines for Flow Assurance. Energies, 12(21), 4070. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12214070