2. Nuclear Energy Development in Bangladesh

Nuclear energy has emerged as an issue of global and local importance, propelled in large part by increased costs of fossil fuels, rising energy needs, concerns over inefficiencies in the energy mix, security of energy supply, climate change, its cleanness as less carbon polluting than fossil fuels, raw material availability, technicians and scientists’ interests, etc. [

5]. Nuclear power supplies a large amount of the world’s electricity needs [

6]. The efficiency of nuclear power is well-documented. For example, 1 kg of U-235 has been shown to be able to produce more than 24 million kWh worth of electricity [

7]. By comparison, a wholly combustive or fission-based process yields 8 kWh worth of heat via conversion from 1 kg of coal. The same amount of mineral oil conversion results in 12 kWh [

8].

At the start of 2011, before Fukushima, there were 441 NPPs in operation in 30 countries [

9]. In 2016, 13 countries generated more than 30% of their total electricity from nuclear: France generated 77.7% of its electricity from nuclear power; Slovakia, 54%; Belgium, 54%; Ukraine, 47.2%; Hungary, 43.3%; Slovenia, 41.7%; Switzerland, 40.9%; Sweden, 39.6%; South Korea, 34.6%; Armenia, 33.2%; Czech Republic, 33.0%; Bulgaria, 32.6%; and Finland, 31.6% [

10,

11].

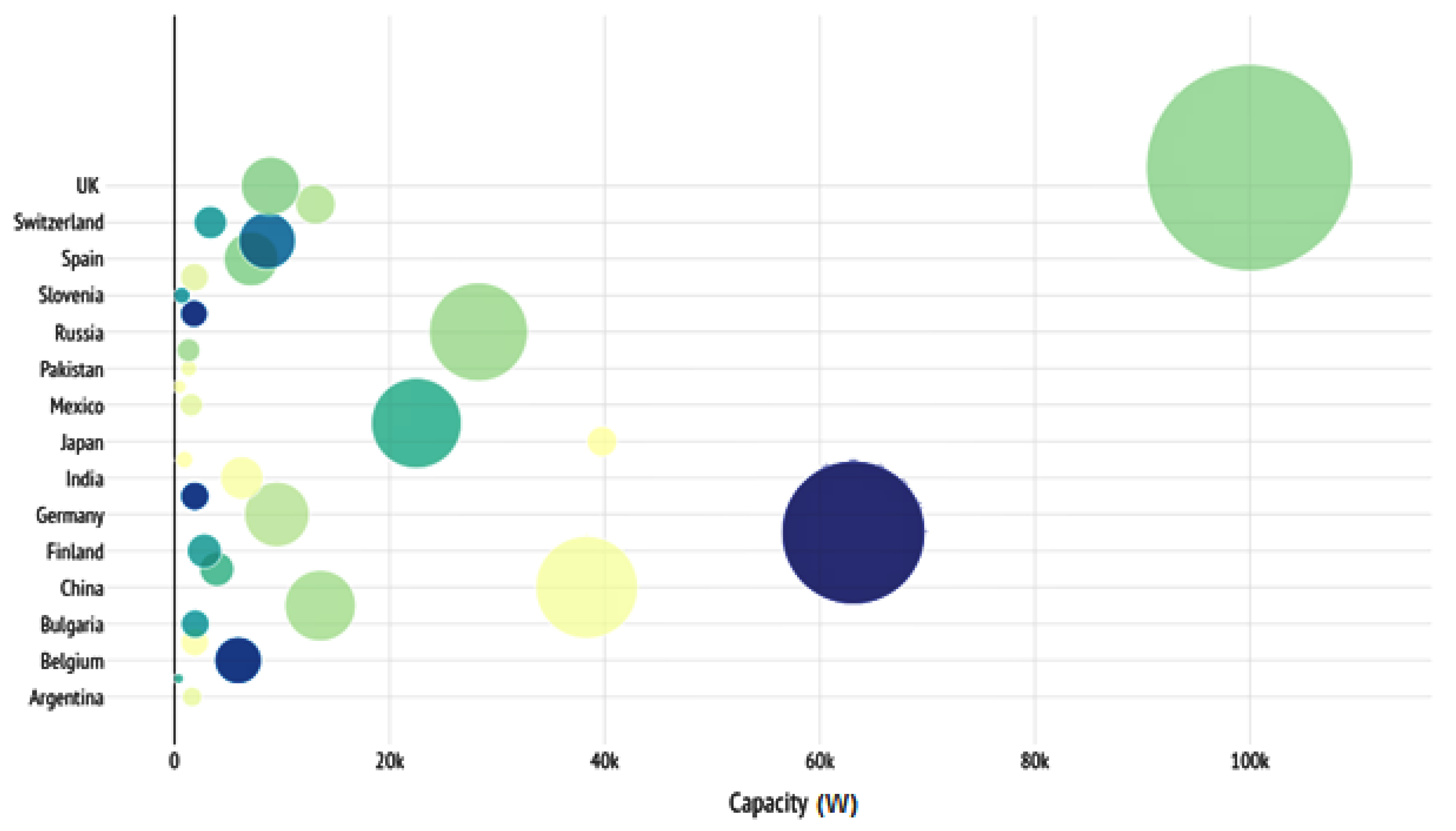

Figure 1,

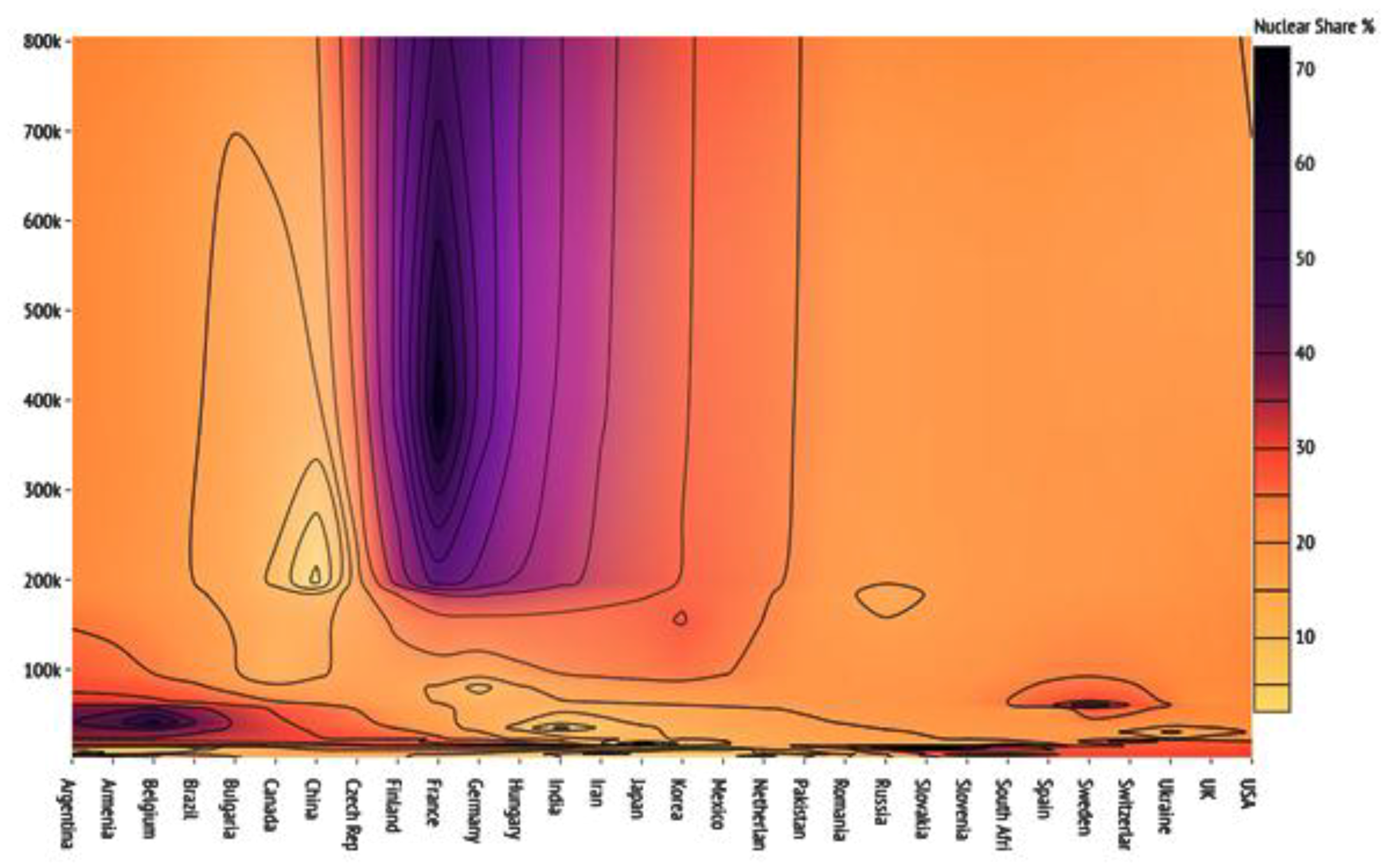

Figure 2 and

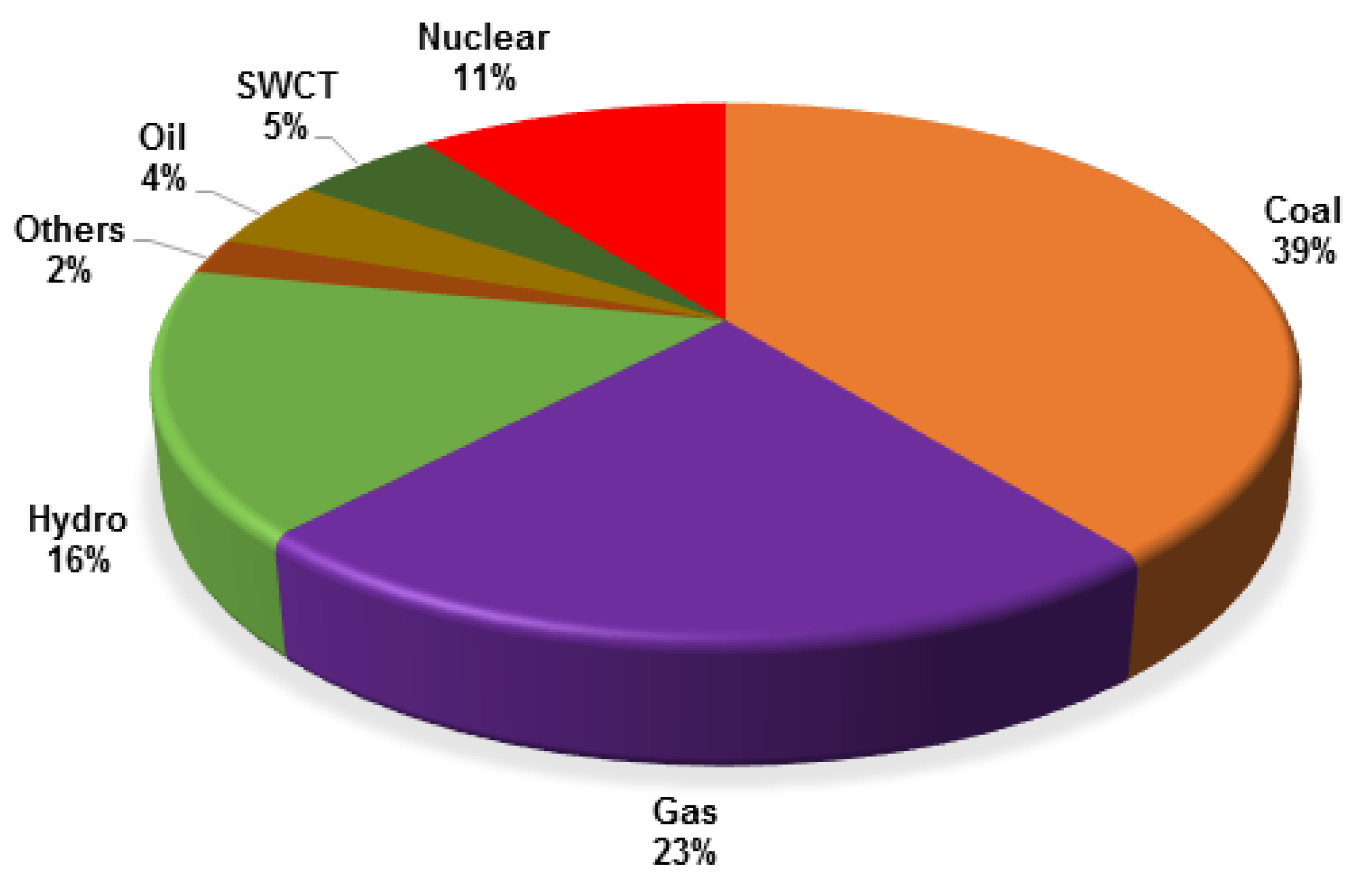

Figure 3 demonstrate an overview of worldwide energy production capacity, nuclear capacity, and distribution of energy sources respectively. In particular, in

Figure 1, bigger bubble sizes indicate more nuclear reactors available, while darker colors indicate higher proportion of energy being generated through nuclear sources;

Figure 2 indicates domestic share of nuclear power generation for nuclear reactor rich countries;

Figure 3 explains the worldwide energy source distribution which displays the contribution of fission technology in the modern world.

In light of the discussed challenges, various resource-rich heavyweight countries have realigned their existing plans pertaining to expansion of atomic power plants [

13]. Examples of such countries include India, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), the United Arab Emirates (UAE), South Africa, China, Vietnam, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States of America (USA) [

10]. Bangladesh is no exception. The steady upward trend in global prices in fossil fuels, crude oil, and coal [

14], and overall dearth of natural gas reserves indicate that, for the foreseeable future, Bangladesh will face pressures in meeting its energy demands, and this pressure will sustain. The environmental impact [

15] of this phenomenon should not be discounted either. Under these circumstances, nuclear energy is an attractive strategic option for the Bangladeshi government. This is reflected in the government’s decision to construct NPPs to stimulate the ongoing economic growth and meet consumer and industry demands. Thus, Bangladesh has undertaken serious initiatives to commence NPPs to mitigate the ever-surging power demands in one of the sprinting economies in the world.

While Bangladesh has been known worldwide as an agriculture-based economy that frequently combats natural disasters, Bangladesh has undergone significant industrialization in the past two decades. The proportion of heavy industries’ contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP) bears the testimony in this regard. Thus, it is hardly surprising that Bangladesh’s policy makers have connected the increase of power generation to the rise of gross domestic product (GDP) growth [

16]. The greatest rational behind the nuclear power production is the prospect of minuscule input producing a great deal of power. The first batch of these projects, Rooppur (located in Pabna district) [

17], is a joint collaborative effort with Russia’s State based Nuclear Energy Corporation (ROSATOM).

In May 2010, an intergovernmental understanding was marked with Russia, giving a lawful premise to atomic participation in territories, for example, siting, outline, development and operation of energy and research in atomic reactors, water desalination plants, and basic molecule enrichment agents [

17]. Thus, the journey to produce the nuclear power energy has already begun. However, despite enthusiasm at the State’s administrative level, some oppositions exist in implementation of NPPs, especially in the form of negative perception and attitude held by certain quarters of the population and intellectual stakeholder community. Therefore, it is the right time for the government of Bangladesh to take initiatives to deal with the challenges for the safe and secured production of nuclear energy. It is imperative that without a strong nuclear safety regulatory framework, it would not be possible for Bangladesh to ensure safe nuclear energy production.

As with most ventures, Bangladesh’s foray into the nuclear energy realm is a double-edged sword [

18]. Although Bangladesh has a lot to gain from this pursuit, the challenges need equally careful considerations, particularly given the high stakes for a developing and high-density country such as Bangladesh. Nuclear energy surely can be a prospective medium of energy source to meet the massive energy demand in Bangladesh, however, for that, the government of Bangladesh must equip themselves with all the necessary tools before going to harness the benefit of such technology.

Nuclear energy is considered to be the most dangerous process in the production of energy [

19] and that how a developing and densely populated country such as Bangladesh takes the initiatives to address the challenges regarding the NPP should be revealed. The most important question is whether Bangladesh can survive any NPP disaster such as the Chernobyl disaster (occurred in the former Soviet Union, now in Ukraine) and the very recent Fukushima (Japan) disaster, when Bangladesh is already vulnerable to natural calamities.

Japan took immediate action after the occurrence of the Fukushima disaster, thus the human losses from the Fukushima nuclear accident itself could have been practically avoided. However, the economic consequences and socio-political impact of the disaster seriously affected the public attitude towards nuclear power and are expected to pertain for quite some time in the future [

19].

One of the basic purposes of present fervor for Bangladesh will be the planning and availability of qualified staff to meet the staggering necessities of the procedure and broadening program. Regardless, the path chosen to develop qualified human resources and personnel needs to consolidate each of the issues that impact human resource training; for instance, activity, organization structures, working society, atomic data organization, and individual perspectives [

14]. In particular, for Bangladesh, it is rudimentary that a productive nuclear power program requires an extensive system. Hence, this paper completely breaks down the atomic foundations, offices, research affiliations, authoritative offices, and government divisions in Bangladesh and assesses whether such bodies have nuclear aptitudes and informational capacity to ensure that nuclear projects are ready in a safe and secure manner. There is no denying that constructing a solid backbone and enhancing a nuclear regulatory system is imperative to avert any NPP disaster [

20]. Instead of operating a single, comparatively miniature NPP to achieve the know-how and expertise, concurrently Bangladesh is moving toward two high output (1200 MWe and 3000 MWth) plants, and, according to experts, the government aims to spend enormous costs on them [

21].

Regarding the economic and safety viability of the recommended NPP at Rooppur, not only academics, engineers, doctors, surgeons, scientists and other experts from Bangladesh but also many foreign nationals and dignitaries, are anxious about the setup.

In Bangladesh, where the conventionally placed coal-based or gas power plants are tumbling down frequently, mostly due to incorrect installation and lack of decent maintenance, the question certainly arises: How secure would a sophisticated NPP be? Gas disasters, naturally, pale in comparison with nuclear disaster in terms of damage and risk to public safety. There exist serious concerns and, therefore, a study about the introduction of nuclear energy in Bangladesh from a legal point of view should be conducted.

A disaster such as Fukushima provides a chance to reconsider [

22], venture back, factor in, and evaluate all the more extensively where, as a group and as a general public, we stand [

23]. Industrialized nations such as Japan and the USA could react promptly after the nuclear debacle [

24]. Is there any guarantee that a developing nation such as Bangladesh with scant resources can replicate their success of recovery? There is no reason to believe Bangladesh can achieve that, given its present scenario and infrastructure. It is important to understand that we welcome any new technologies that come forward; however, such technology must be equipped with proper tools for safe and secure generation and production.

The commitment of Bangladeshi government toward ensuring the concerns related to safety of atomic power plant and power generation as a whole cannot be doubted [

16]. Other than the liability issues, the government of Bangladesh has been trying to come up with a solid legal structure. There remain certain loopholes in that structure. However, the government’s genuine intention to provide the best regulatory structure must be appreciated.

3. Nuclear Energy Regulations in Bangladesh

The first step in regulating nuclear energy in any State includes assessing the present and future anticipated programs and plans concerning atomic techniques and materials [

25]. This is regardless of whether the country is adopting a brand new framework for a legislation, revising an existing one, or simply updating one or more aspects of its legislation [

26].

Scholars have identified several levels within the hierarchy of a nation which is going to build new nuclear power plants. The first, ordinarily held as the constitutional level, sets the primary legal and institutional framework to govern all relationships in the State [

27]. The statutory level is directly underneath the constitutional level, at which particular laws are passed by a parliament to place other imminent bodies and to foster the rules connecting to the wide range of activities concerning national interests [

2].

The third level includes very comprehensive regulations that are usually quite technical to regulate or control activities stipulated by the legal instruments [

2]. By reason of their distinctive character, the expert bodies (comprising bodies nominated as regulatory authorizations) usually state these rules. In addition, these bodies are authorized to look after specific domains subjected to national interest and promulgated through the national legal framework.

A fourth level comes with non-mandatory guidance instruments containing instructions meant to serve organizations and persons to meet the legal specifications [

25]. Based on which kind of nuclear ventures a nation chooses to sanction, the optimal use of the nuclear technology may require the employment of a wide array of laws initially associating with other subjects (for instance, industrial safety, environmental protection, mining, transport, administrative procedure, land use planning, electricity rate regulation and government ethics).

Usually, the discrepancies from the general structure of national legislation ought to be accepted only where the distinctive characteristic of an activity justifies the special treatment. Consequently, up to the degree that an activity deals with nuclear is modestly incorporated in other laws, it should not be necessary to issue new laws. Nevertheless, from the initial stage of its advancement, to make sure the proper management, nuclear energy has always been acknowledged to use special legal design. Bangladesh, thus far, has followed these levels to incorporate new regulatory structure particularly for fission technology. However, there are still some gaps, which need to be addressed soon to make a comprehensive nuclear regulatory regime. This paper attempts to find such gaps and recommend the Government of Bangladesh to take necessary regulatory steps to ensure the safe and secure nuclear energy production.

In the case of Bangladesh, the agency appointed to deal with assessment of safety and security of nuclear energy is Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission (BAEC) [

28]. This is a scientific research organization. Established in 1973, two years after the liberation war, its primary goal is promotion of using nuclear energy for peaceful purposes and to maximize citizens’ export.

BAEC, subjected to the presidential order of 1973, enjoys the role of sole beneficiary owner of the NPP and thus is entrusted with our atomic regulation related aspects. Meanwhile, Bangladesh Nuclear Power Action Plan (BANPAP) (2000) and Bangladesh Atomic Energy Regulatory Authority (BAERA) operate under the auspices of existing Nuclear Safety and Radiation Control (NSRC) Acts (1993 and 1997), and Bangladesh Atomic Energy Authority (BAEA) Act (2012) [

29].

The International Atomic Energy Authority (IAEA) safety standards, established under the prevailing domestic legislation frameworks, requires the organizations interested with operation of NPPs to liaise with an independent regulatory body [

24]. This law empowers the BAERA with the ability to a apprise safety and security related to atomic plants, protecting the personnel from radiation, authorization, transporting and managing waste materials, assessing and shielding raw material and liabilities for transportation, and overall operation of nuclear facilities throughout the country.

Regardless of which regulatory agency is vested with carrying out assessment criteria, be it from the government, a committee from the legislation body, or an independent expert panel, the actions of that regulatory agency should not constrict itself to the confines of present and expected programs in the immediate future [

30]. Instead, they should be versatile enough to contemplate and design programs which could surface and a somewhat more distant future keeping in mind the fluid and swiftly changing patterns of the global economy. As such, we argue that designing advance legislative guidance pertaining to operational parameters of atomic energy related actions and its concomitant regulations is a superior proactive strategy compared to the present patterns of reactive policies, even if that means that the present guidance is hastily drafted and requires revisions in the future. This is far better than abandoning guidance and leaving operations without any regulatory oversight. Previous precedents from nuclear disasters have shown that nuclear activities, even if carried out in good faith, run the risk of environmental, safety, health, security, and economic pitfalls.

Along these lines, the Bangladeshi government has viably figured out how to develop the definitive structure to erect a sustainable and responsible framework for NPP in general and to create, commission and work the country’s first nuclear power plant: the Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant. In line with this commitment, the BAER Act has quite recently been maintained with robust commitment from national specialists, IAEA and furthermore a well-reputed vendor country to set up an independent managerial body, the BAERA, to execute administrative obligations without undue obstacle from the bodies responsible for making, progressing or operational assignments of nuclear foundations [

30].

3.1. Assessment of Laws and the Regulatory Framework

Generally speaking, new atomic legislation should incorporate a complete appraisal of the status of all things considered and administrative courses of action significant to atomic energy [

2]. This undertaking may not be a direct one. In most national legislation frameworks, numerous arrangements not particularly coordinated towards atomic related activities can have a considerable effect on how such activities are directed. Notwithstanding broad environment laws, enactment concerning financial issues (e.g. tax collection, liabilities, administrative charges, financial punishments and the setting of energy and utilities rates), workers’ wellbeing and security, criminal enforcement, planning of land uses, worldwide customs and trade, scientific research, and many other related disciplines, may encroach on endeavors pertaining to atomic related activities [

31].

Bangladesh has repeatedly demonstrated her commitment and responsibility to anchor and advance human rights. Common and political rights are seen in the constitution as real rights. Article 11 of the Bangladesh Constitution communicates that the Republic will be a prominent government in which significant human rights and openings and respect for the pride and worth of the human individual will be ensured [

32]. Indeed, even money related, social and social rights are recognized and regarded by the Constitution of Bangladesh. The constitution arranges that it will be a key obligation of the State to achieve, through arranged financial development, a steady addition in helpful forces and an unwavering change in the material and social lifestyle of the overall public with a view to anchoring to its nationals the arrangements of the key necessities to life, including sustenance, protection, shelter, clothing needs, education and instruction, and human services [

33].

Along these lines, energy is inseparably associated with other basic human rights and in most of the cases a precondition to fulfill substitute rights. Reports such as the American Convention on Human Rights, the African Charter of Human and People’s Rights, the Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development, the UN Declaration on the Right to Development, the Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment and others give state change and affirmation of various human rights through comprehensive access to energy.

Bangladesh is a nation host to countless conventions and in this manner is bound to fulfill each of the responsibilities constrained by them. Both the Fundamental Principles of State Policy and the Fundamental Rights’ parts of the Constitution of Bangladesh contain courses of action, which are overwhelmingly dependent on comprehensive and feasible access to energy. Article 15 of the constitution includes different rights major for the affirmation of the benefit to an adequate lifestyle, including access to agreeable sustenance, clothing, survival, and to the persistent change in living conditions. These rights are interrelated with the basic access to energy. That very article similarly empowers commitment on the State to ensure respectable work condition, which is unavoidable with genuine access to energy. In addition, Article 16 is based on common and country progression, while ceaseless access to energy is considered the best and most critical instrument to get positive changes in this domain.

The provision in Constitution of Bangladesh additionally ensures work with reasonable wage, right to standardized savings, and personal satisfaction. The established arrangements are made to ensure, advance and regard financial improvement as a constituent of human rights in Bangladesh. Be that as it may, the current context is prejudicial as half of rural populace has no access to power. Despite what might be expected, as indicated by the United Nation’s Least Developed Countries (LDC) Report 2017, 84% urban citizens get power but the rate is as yet unsuitable contrasted with the world average [

34].

In any case, the next few articles of Bangladesh Constitution again stress citizen’s rights to education, well-being and environmental security and conservation, which are not in the slightest degree achievable by the State if access to energy facilities is not ensured. Moreover, Article 31 ascribes the right to life as a major right, which doubtlessly incorporates right to employment. Nonetheless, right to life revered in Bangladesh Constitution fails to translate as right to breathe and live as a mere animal. Instead, it imputes great importance on life incorporating right to live with dignity, respect, and comfort, as attested by the Judiciary in Ain O Salish Kendra vs Bangladesh, 1999 BLD 488 case [

35].

In this manner, the privilege to have access to power can be translated as a sacred commitment of the State and enforceable by the court. Moreover, it is a protected commitment for the government of Bangladesh not exclusively to give sufficient quantity of energy to its citizens, but also to ensure the safe and secure production of the energy.

Along these lines, there is no extent of circumventing this duty by claiming falsely that there is no particular law on citizens’ rights to gain access to energy. Instead, if the full notion of the Bangladesh Constitution is considered, it becomes clear that the goal of the constitution is to slowly improve the standard of livelihood for the peoples of this Republic. To reiterate, the State component should look into the matter of all-inclusive access to current energy from a human right point of view to make it more comprehensive.

Moreover, it is additionally required to proceed with the issue with cautious and sincere insight for the improvement of the country and its long-term sustainable growth. From an economic point of view, considering the scarcity of resources, we should make present day energy authorities accessible in view of equality and non-segregation to the entire populace including those who are left behind by the society; the most underprivileged.

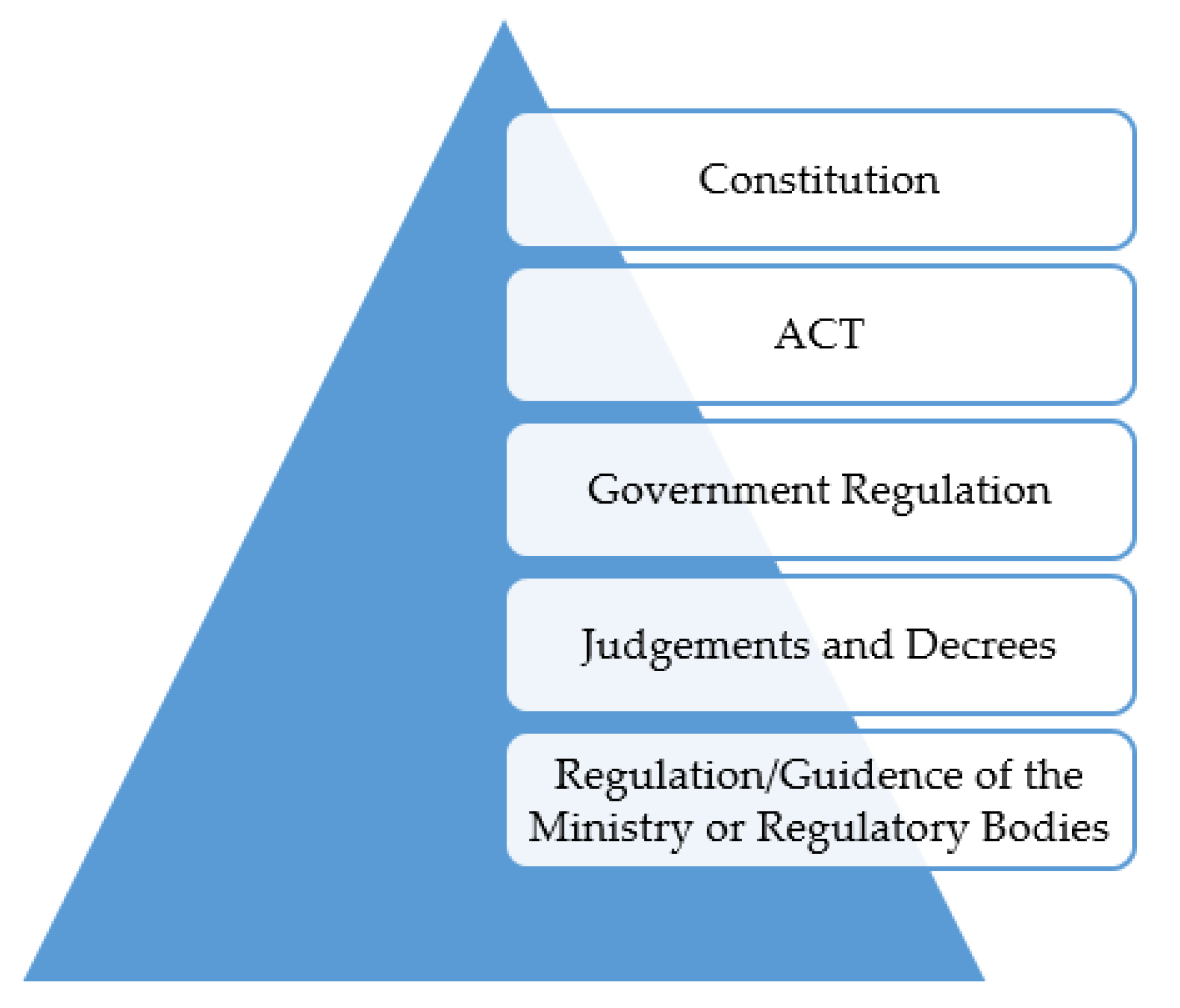

To understand the legal procedure relating to any aspect of a nation, it is very important to look into the country’s regulatory structure and hierarchy. Therefore,

Figure 4 shows the structure and hierarchy of the laws in Bangladesh to construct a comprehensive regulatory idea about the nuclear energy for the country.

In

Figure 4, the Constitution of Bangladesh is the supreme law of the land, and no other law can be in conflict with the provisions of it. It stands on the top of any legislative structure applied in the country. The basic features of the Constitution of Bangladesh are:

- (a)

Supremacy of the constitution (Article 7 of the Constitution).

- (b)

Democracy (preamble).

- (c)

Republican government (Article 1 of the Constitution).

- (d)

Independence of judiciary (Article 22 of the Constitution).

- (e)

Unitary State (Article 9 of the Constitution).

- (f)

Separation of powers (Article 22 of the Constitution).

- (g)

Fundamental rights (Articles 26–47A of the Constitution).

In addition, it requires the government to ensure all the necessary steps to produce energy through safe and secure means, and on any disastrous event, the government is under an obligation to safeguard the citizens and ensure compensation through legal tools.

Other than the constitutional protections for the citizens, the government of Bangladesh has also enacted various laws and regulations to ensure the safe and secure production of the nuclear energy:

The Atomic Energy Commission Order, 1973

The Nuclear Safety and Radiation Control (NSRC) Act, 1993 and the NSRC Rules 1997

The Bangladesh Nuclear Power Action Plan (BANPAP), 2000

The Bangladesh Atomic Energy Regulatory (BAER) Act, 2012

The Nuclear Power Plant Act 2015

Using the BAER Act, Bangladesh government is proceeding with plans to promote a separate framework for regulation of atomic energy and ionizing radiation. The first chapter of this Act states that the first portions including definitions, range, and amplitude of the power vested on the regulator must be carefully calibrated. Moreover, the range of power given to the Act are clearly specified in the Section 3. Besides, Section 5 allows a superseding clause to the BAER Act which states that, unless explicitly stated by any other law or provision, the BAER Act will have the final say in deciding matters [

29].

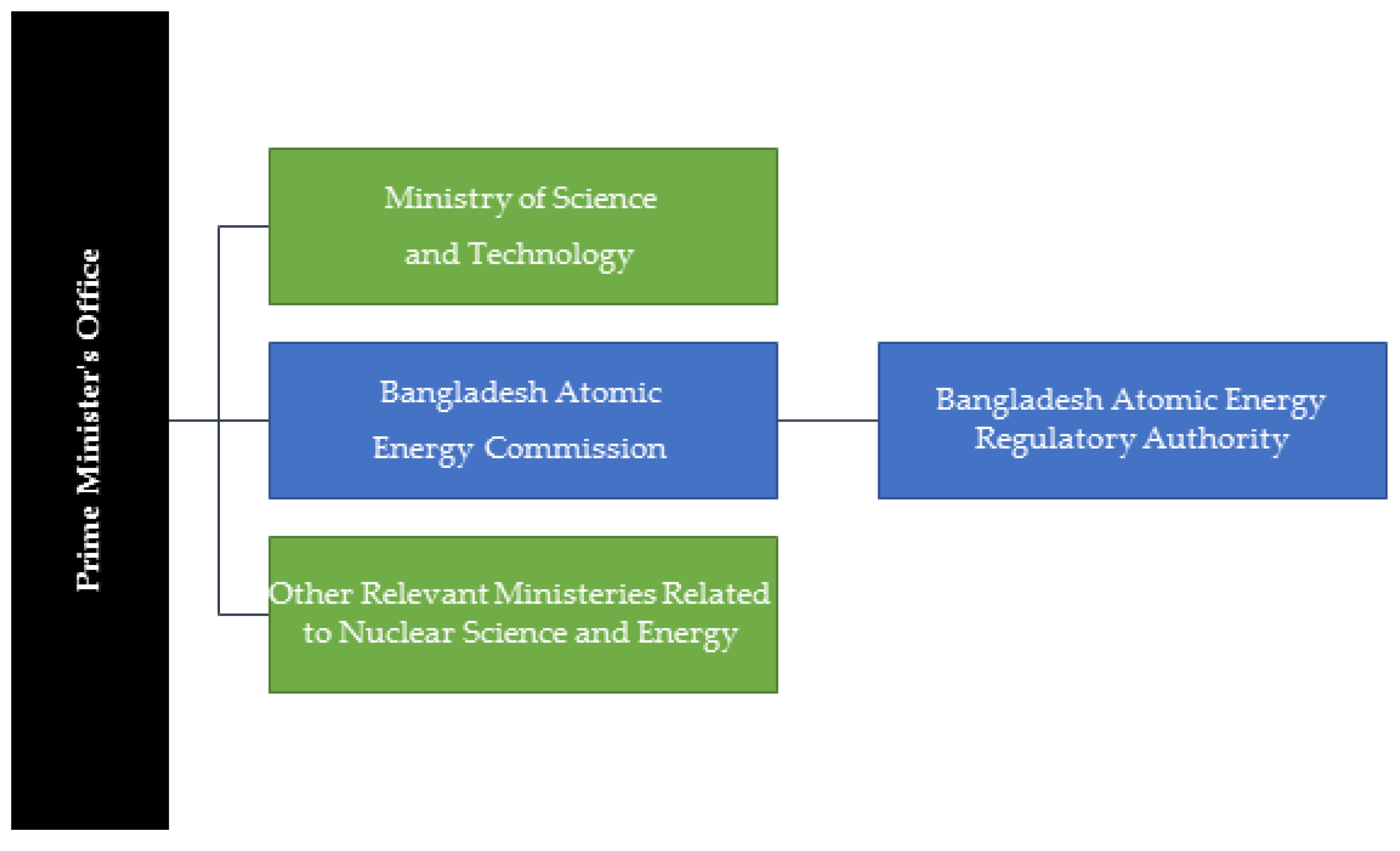

Figure 5 outlines the general framework and stratification of the local Government pertaining to atomic energy regulation. Under the ambit of this framework, BAERA is expected to exert independent influence as per directions of ministry responsible for administering science and technology. Ancillary issues relating to the affairs of the central government and local administration will require compliance with BAERA’s decisions so as to not jeopardize nuclear safety and put public safety at risk. The organization and delegation of such power to BAERA are specified in the Section 8. Accordingly, four members will form a committee to oversee the operations, headed by a chairperson, who will also discharge the duties of chief executive. This person will be liable to answer directly to the government minister responsible for science and technology. Due to involvement of the relevant ministry in this matter, the BAERA will benefit from having a direct access to the government whenever consultation is necessary, or conflict of interest arises. Moreover, the major conduits of BAERA’s options will be required to oversee administration of nuclear energy safety through a specific chain of command via ministries responsible for science and technology, health and family-welfare, environment and forestry, industry, commerce, law, defense, agriculture, and the Power Development Board. If deemed necessary, BAER Act leaves open a clause for establishing an advisory council for consultation to the relevant scientific and regulatory bodies to clarify any confusions about radiation or atomic safety as per provisions of Section 19.

Notwithstanding the lawful and political autonomy, the monetary freedom of the BAERA is guaranteed through the financing instruments accessible to the authority. Section 13 determines the funds of the authority. The authority will have its very own reserve. The fund will be gathered by the accompanying, in particular: (a) reserves allowed by the administration every year; (b) expenses and charges kept under BAER Act; (c) gifts enjoyed through national and global offices, not directed by authority, with earlier endorsement of the legislature; and (d) cash transmitted from ancillary sources. The authority may acquire credit under this Act (Section 14) with a specific end goal to discharge its fundamental activities and the authority will be expected to pay-off under pertinent conditions. If there should be an occurrence of overseas loans, advance endorsement of the administration is important. The authority will recuperate every single due expense, charges, punishments and other applicable charges as requested by the general public as per Section 15.

Additionally, Section 17 determines the issue of audit and accounts. The Comptroller and Auditor General of Bangladesh will review the records of the authority consistently and will send duplicate of review answer to the legislature and the authority. It is received practice that the BAER Act is the main driving source behind the legitimacy and power of BAERA. Hence, authorities are expected to move in a deliberate procedure for comprehensive setup of regulatory framework and independent operational freedom.

3.2. Safety Requirements and Regulations

To understand the safety requirements and regulations of nuclear energy, we need to look at how the single regulatory body BAERA is functioning within the country’s nuclear regulatory structure.

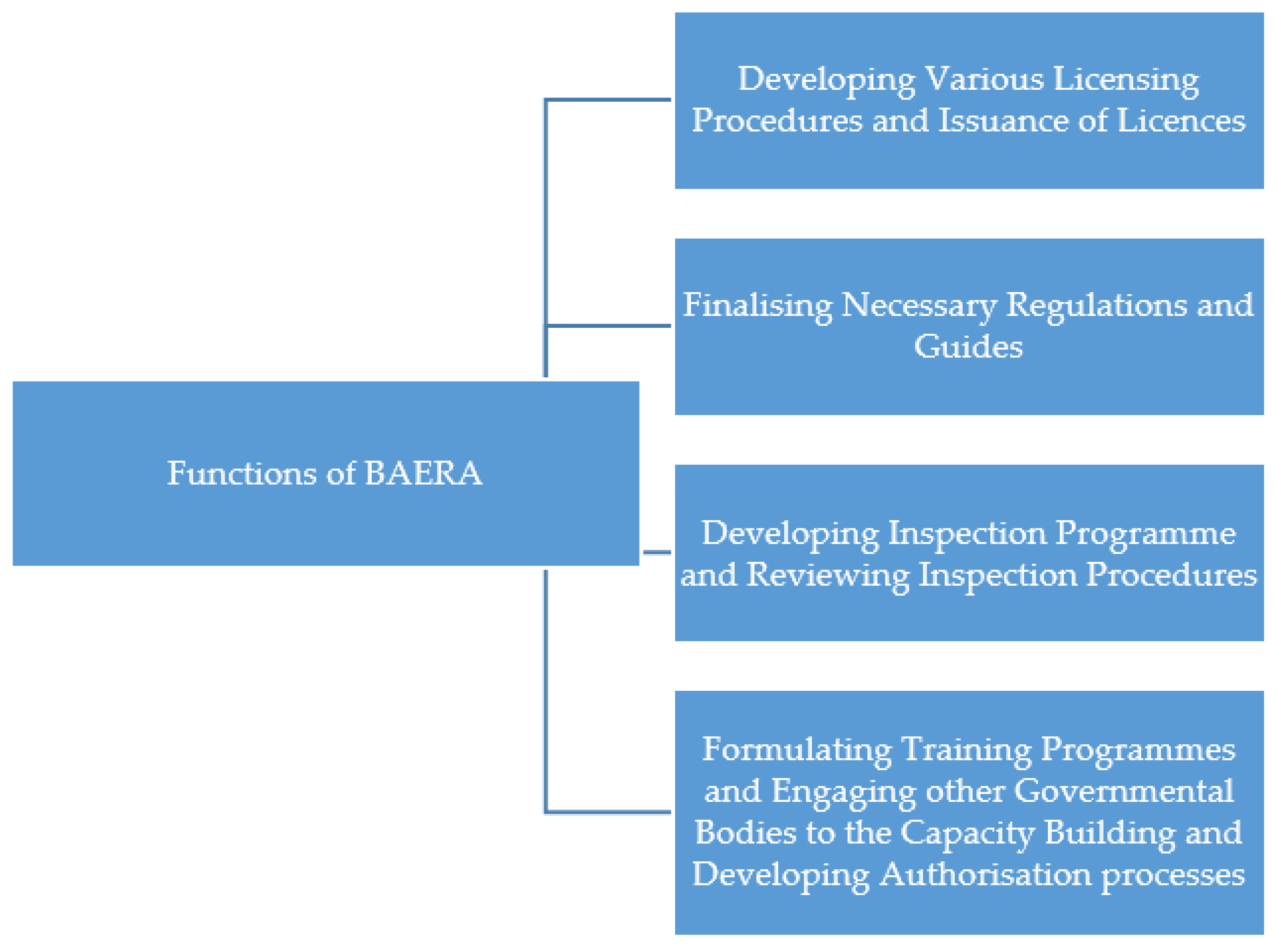

Figure 6 elaborates the major functions of BAERA. BAERA’s main goal is to guarantee the safe and secure utilization of atomic energy in Bangladesh so undue hazard to human prosperity and the environment is eradicated. To understand this mission, the BAER Act (2012) gives the principle lawful premise. Conversely, national tenets, controls, aides and worldwide instruments, codes, and measures are the essential archives specifying chief, prerequisites, practices and arrangements for upgraded wellbeing. The guidelines and controls are primarily in light of IAEA security prerequisites, gauges and aides, giving best need to the wellbeing. The BAERA utilizes IAEA security prerequisites and seller nation controls where the issues are not expressly secured by the national directions. Through a thorough approval plan, assessment and authorization framework, the BAERA achieves administrative control of atomic establishment with legitimate thought for the assurance of authorities, open and nature and atomic security.

The National Legislative prerequisite on atomic and radiological security for all activities identified with the serene utilization of nuclear energy in Bangladesh stems essentially from Section 18 of the BAER Act (2012) that forces limitations on specific activities without having proper type of approval by the BAERA. BAERA, by practicing powers under Section 11 of the act, is the capable expert in Bangladesh to guarantee the consistence of nuclear safety and security in any atomic establishment. In addition, Section 30 of the BAER Act (2012) expressly expresses that it is the sole duty of an approval holder to guarantee nuclear safety and security in his/her atomic establishment. A similar section has additionally enabled BAERA to make controls on the necessities of atomic security.

There is additionally an arrangement in the BAER Act (2012) that permits the NSRC rules (1997) made under the canceled NSRC Act (1993) keep on being operational as though it were enacted currently, whereby the Act is presumed to enforce thorough and definite directions set up under the BAER Act (2012). These principles (NSRC Rules 1997) likewise give rundown of pertinent standard, code and support mechanisms important to various phases of nuclear establishments to guarantee atomic safety and security.

In accordance with Section 16 (1) of the NSRC Act (1993), the Nuclear Safety and Radiation Control (NSRC) Rules were told in the Bangladesh Gazette on 18 September 1997 to accommodate guaranteeing nuclear security and radiation control in Bangladesh. The principles, in practice, amalgamated all the constituent prerequisites of the IAEA Basic Safety Standards (IAEA BSS No. 115, 1996) [

36].

The NSRC rules are very far reaching for the control of all radiation/atomic practices. The tenets which are of particular substance and importance to nuclear offices are mentioned hereforth: Requirement of permit (Rule 7); General necessity (security and insurance, budgetary asset, human asset, and so forth.) (Rule 10.1); Stage of permit (sitting, brief activity or start up and full task) (Rule 10.3); Condition of permit (Rule 10,14); Applicable standard, code and aides (Rule 15); Responsible gathering (Rule 16); Safety prerequisite (Rule 17); Technical prerequisite (Rule 18); Management prerequisite (quality affirmation program, wellbeing society, human factor, human asset, instruction and preparing, qualified master, protection and so forth.) (Rule 19); Occupational presentation (Rule 20); radioactive waste administration (Rule 87); Inspection (Rule 90); Penalty (Rule 91); Emergency Rectification measure (Rule 94); and Compensation (Rule 97).

Timetables for public workers, comforters of patients, activity levels for acute exposures, and different direction levels for patients have just been adopted and lawfully notified. In any case, it should be noticed that a portion of these principles have just been received by the BAER Act (2012) and, as indicated by the law, if there should arise an occurrence of any logical inconsistency between BAER Act (2012) and NSRC Rules (1997) BAER Act, will prevail.

3.3. Directions Identifying with Appraisal and Confirmation of Nuclear Reactor Safety

Section 30 of the BAER Act (2012) tended clear-cut to the necessity for Nuclear Safety of any atomic establishment and related activities. According to Section 30 (2), the obligation to guarantee the nuclear security lies with the approval holder of the corresponding establishment. The approval holder is subject for the arrangement of sufficient funds and human resources and in addition equipped for completing essential building and specialized help activities to guarantee atomic security in their atomic establishment.

Sections 30 (3)–30 (7) describe the requisite should be satisfied by the approval holder to guarantee atomic well-being all through the lifetime of an atomic establishment. As per Section 30 (3), the approval holder needs to perform consistent, far reaching and methodical evaluations of nuclear well-being considering the cutting-edge information and comprehension in the region. Moreover, considering the working encounters of comparable NPPs, vital measures are necessary to wipe out any inefficiencies recognized amid the whole working life cycle and the decommissioning phase of a nuclear establishment. The approval holder likewise needs to keep records of wellbeing assessment activities and about alterations of their nuclear establishment (if applicable). According to Section 11 (7), the BAERA do audit and examination of the well-being appraisals and enforce necessary actions as required. In addition, Section 51 of the BAER Act (2012) offers leeway to the authority to lead administrative assessment in an atomic establishment to confirm that the nuclear safety and security demands of the Act and the pertinent directions planned under the Act are appropriately being complied with [

37].

In addition, keeping in mind the end goal to guarantee the well-being of NPPs, atomic energy laws should give an ideal risk plan to the government, full strict obligation for the administrator; joint and several liabilities with upstream providers, with the upstream providers‘ obligation being limited to a negligence standard; and compulsory risk protection to be given by the market to some degree. These risk plans and the commitments of a protection contract are recommended by the universal traditions on nuclear law. However, the legislature of Bangladesh is resolved to give a civil liability to nuclear harm and pay to the casualties of an atomic episode as indicated by Chapter VIII of the BAER Act. Subsequently, there remain legal concerns at the present stage pertaining to the liability issues of nuclear disaster.

3.4. Directions Identifying with Radiation Assurance

As indicated by the Section 11 (4) of the BAER Act (2012), BAERA is the vested body in Bangladesh to regulate that the arrangements identified with the radiation insurance in its purview are appropriately consented to or not. As indicated by Section 31 of the BAER Act (2012), approval holder is liable to guarantee radiation security of nuclear organization. Up until now, radiation insurance foundation and program in every single pertinent action/offices, for example, the exploration reactor (BTRR), Central Radioactive Waste Management Facility, various radiation offices, and so forth, are complete and agreeable and is reinforced on consistent premise in light of development of technology and levels of experience.

As a legacy vestige from the previous Nuclear Safety and Radiation Control Division of BAEC, security observation/review and administrative component of the BAERA in the region of radiation insurance is additionally extensive, persistent and careful.

3.5. Authorization Process

The approval method involves for the most part Chapter III of the BAER Act. Section 25 shows the exercises required for holding approval or getting managerial allowances from the responsible expert panels. The systems for issuing approval and the commitments of the approval holder are reliant principally upon Sections 27 and 28, individually, of the BAER Act. Section 30 demonstrates that the expert to control import and fare of nuclear and radioactive material, while Section 31 decides the approval strategy for import and fare control of nuclear and radioactive material. The authoritative issues on suspension and rescission of approval are resolved in Section 34, and Section 34 (4) describes a game plan of offer by a disputative or disgruntled human resource segment. Section 34 (4) states that, if a man is faced by a demand of suspension and withdrawal of the endorsement under this Section, he may guarantee up to 30 long periods of receipt of such demand to the Appellate Committee established by the Government. The Secretary of the Ministry of Science and Technology will be the Chairman and the official investigator of the executive body will be the secretary from the Appellate Committee.

Sections 18 and 19 of the BAER Act (2012) indicate the prerequisites and process for acquiring permit from the authority, BAERA. This Act manifestly expresses that no individual, administrator or foreign authority will plan, build, commission, work, and decommission any atomic establishment and discharge the site from administrative control without holding an approval issued by the authority. Likewise, the Act limits to get, deliver, claim, import, send out, have, utilize, transport, process, reprocess, exchange, exchange, uproot, store, desert or arrange any atomic material, radioactive waste and spent fuel and carryout inquire about on them without having fitting type of assent of the BAERA.

The BAERA issues the approval (for example, Siting License) to an atomic establishment and does security observing, examination and authorization activities under the arrangements of BAER Act (2012). For example, Section 21 of the Act recommends the general technique for issuing approval. For various stages/kinds of approval, BAERA takes after particular norms, codes and aides that determine the base security related prerequisites that must be satisfy [

38].

Sections 51 and 52 of the Act determine the prerequisite on administrative assessment and implementation to be completed by the BAERA in nuclear power plants. For these plants, the approvals are issued for the significant stages. Examples of these stages include inspection and determination of proper sites, building and construction, commissioning and eventual decommissioning, operation, etc. Approvals for these processes are known as licenses. Up until now, aside from the involvement in controlling the TRIGA MARK II Research Reactor, the recently set up BAERA has as of late provisioned the Siting License for the two units of VVER-1200 reactor at Rooppur NPP.

3.6. Preparation for Emergency

Fortifying nuclear safety and security and atomic hazard readiness is a worldwide issue [

39]. Each innovation imparts a few dangers and the nuclear technology is no aberration. As a rule, Generation III and Generation III+ Nuclear plants have been planned with sufficient wellbeing frameworks that could limit the likelihood of radiation discharge from the mishaps; uncommonly, the Fukushima atomic mischance demonstrated to us the need of a thorough atomic catastrophe administration program [

40,

41,

42]. Bangladesh government has considered the issue of atomic crisis readiness genuinely and wants to fortify capacity of regulatory bodies in an appropriate manner.

Chapter VII of the BAER Act has indicated the administrative necessities of the crisis readiness and reaction and in addition association to be engaged with instance of Bangladesh. As indicated by this Act, the office licensees of atomic establishment or radiological office are required to set up nearby and off-site crisis designs. Section 8 (1) recognizes the crisis designs. The office licensees are required to build up nearby and off-site crisis designs. Section 8 (2) unequivocally distinguishes the authorization holder will be at risk to accept preventive measures and additionally measures to moderate or dispense with outcomes of occurrences and accidents at nuclear establishment or radiological office or amid the shipment of radioactive material. That person will be obligated to convey the message to the media and general society about the measures and methodology [

43].

The BAER Act has enabled BAEC for planning the arrangement of the national crisis design. Area 49 states that the Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission will be in charge of organizing the readiness of the national crisis design. The Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission, being trained by local and foreign experts, will arrange with other national associations as indicated by the national atomic and radiological crisis design. This is further supplemented by emergency rectification measures outlined in Section 50.

4. Recommendation

It cannot be denied that the Government of Bangladesh has taken the necessary regulatory initiatives to start their very first NPP project. The initiatives are highly appreciable. However, there remain certain regulatory concerns which this study has tried to reflect.

All the indications so far point to a high probability of BAERA’s failure in meeting the challenges within time with regards to rolling out the needed guidelines and working procedures, let alone their enforcement congruent with extant laws and policies. Besides, devising advancement programs and getting involved ancillary regulatory agencies for the broader goal of NPP safety can be equally daunting. Furthermore, BAERA also has to ensure cooperation with over-arching state-wide legislation and administration via development of capacity. This will mean that BAERA will gain access to the necessary legal powers to stamp a comprehensive framework for legal oversight while preserving its independence.

A complete arrangement for detailing of the basic directions and the full authorizing process has just been finalized by the BAER Act. Nevertheless, the administrative criteria for acknowledgment and endorsement of the plant configuration are a contentious but necessary issue for choice of NPP. To maintain a strategic distance from dangers related with administrative issue, as a newcomer country, the BAERA can consider adoption of the designer’s country update nuclear-related well-being directions associated with permitting of the plant outline, development, appointing and activity of NPP aside from the administrative requirements and conditions for the issues pertaining exclusive to the sites.

Establishing proper regulatory experts to deal with the complex issues of nuclear energy law is also another challenge that BAERA might face. In this manner, the BAERA should work its enrollment plans, execute it efficiently, and build up a sound preparing arrangement. Moreover, the preparation program has to show consistency with its needs and priorities. Accordingly, competent authorities should initiate contacts with administrative groups of different nations and with global organizations, to advance collaboration and the exchange of administrative data. The IAEA Safety Standards Series GS-R-13 might be employed as consultants for this purpose. That would allow for creating methodologies in labor recruitment, preparing policies and training initiatives. The authorities, moreover, need to likewise continue with foundation of a quality administration program and the IAEA Safety Standards Series GS-G-1.14 might be used as a beacon report in this connection [

43].

Likewise, there are numerous affected parties and stakeholders at the State level that should be associated with administrative basic leadership concerning atomic energy. This law must likewise empower the regulatory authority to liaise and arrange with other legislative bodies and with non-legislative bodies having ability in territories. Such examples include transportation, safety and security, environmental protection, and shifting of hazardous materials.

It is alarming to note that, although the government of Bangladesh has taken the initiative to establish an independent regulatory body, the government has not enacted any laws, rules or provisions that state clear liability rules for the damages. It is very important to note that, without having a proper liability rule that has been suggested by international authorities, it is impossible for the government of Bangladesh to ensure justice in any disastrous or accidental event of NPP. In this regard, it is absolutely vital to establish liability regimes to clearly demarcate the necessary responsibilities of all parties.

The concerned legislative bodies in Bangladesh is determined to afford a civil liability to nuclear-related harm and pay to the casualties of a nuclear disaster episode through household legislation. In any case, as per the global legal praxis, endorsed by the traditions, nuclear energy laws are expected to give optimal risk plan to the government, full strict obligation for the regulatory authorities; joint and several liabilities with upstream providers, with the upstream providers’ risk being limited to a negligence standard. Additionally, obligatory liability insurance should be given by the market to some degree or more by the government [

44]. It is always recommended that the government of Bangladesh should typically adhere to the liability schemes suggested by international conventions on nuclear energy. Therefore, it is essential for Bangladeshi government to revisit the issue and amend the provisions pertaining to nuclear energy liabilities.

The nuclear legislation structure is expected to show consistency with the national legal and political conventions, establishments, financial conditions, extent of technological improvement, cultural norms and social values. Forcing rules after harm is inflicted or liabilities caused is an exceptionally reactionary and ill-advised approach. Drafters of legislation should keep in mind that making the national administrative courses of action for the lead of nuclear-related activities are to be very wide in scope, as much as practically enforceable. Besides, it is hardly adequate only to survey options or alternatives that may be of interest. Governments must be set up to settle on firm choices on the degree and character of the sort of nuclear energy development that they intend to sponsor. Such choices require an unequivocal and articulated expression of national strategy. Government must also expect extended debate in this matter from public and be prepared to calibrate its views accordingly.

The BAERA should create indispensable directions on crisis composition recognizing the parts and duties regarding every organization to be included. Before appointing phase of the NPP program, satisfactory crisis planning arrangements are encouraged to be completely set up, incorporating conventions with local and national government, including suitable global courses of action. Furthermore, a manifest hierarchy of leadership for crisis reaction administration should be erected. The authority should acknowledge the responsibilities to define crisis reaction records that give courses of action to coordination and conventions, including correspondence arrangement for a viable unified reaction among the licensee, local first-responders, services, ministries, and the administration to a NPP crisis episode.

In this connection, Bangladesh has planned a National Plan for Disaster Management for the period 2010–2015 [

45]. This arrangement has demarcated the prospective dangers those may cause a catastrophe and the failure of nuclear generators. Experts agree that this sort of hazard is one of the worst anticipated form of technological risk. Along these lines, it is cardinal for the BAERA to set up a National Nuclear or Radiological Emergency Response Plan in line with global practices seen in many advanced countries. The IAEA Safety Standards Series GS-R-27 and the IAEA Safety Standards Series GS-G-28 can be consulted in this regard to ensure global standards are being met and to streamline the implementation processes [

46].

Like other nuclear energy producing countries, Bangladesh also established two authoritative bodies to investigate the safety of the Nuclear Power Plants. Other than BAEC, BAERA is the separate Atomic Energy Authority which eventually would be responsible for independent nuclear safety supervision on all civil nuclear facilities including nuclear power plants. However, as the authority still operates under the Ministry of Science and Technology, there remains a question over the independency and sovereignty of the authority.

The legal structure and regulatory system regarding the nuclear power plant of Bangladesh should also rationalize the duties and functions of nuclear safety management among the various agencies responsible for nuclear power in the country like China and strengthens the independence, authority, and professionalism of the nuclear safety regulatory body. The regulatory bodies for nuclear power plant in Bangladesh must also try to reduce the cost of nuclear power generation and enhance its market competitiveness.

BAEC and BAERA can also provide regulatory guides like National Security Council (NSC) in Japan, which would emphasize on regulatory requirements in building nuclear power plants in Bangladesh. Such guides should also consider beyond design basis events such as station blackout (SBO) events, anticipated transients without scram (ATWS), natural calamities and terrorist attacks. Regulatory process of BAEC should continuously promote to cater to the new developments in reactor technology.

The legislation and regulation which may affect the technological decisions as well as design and construction of the plans need to be clearly defined as well. Moreover, the BAERA should be established and armed with full degree and authority to execute the capacities appointed by the BAER Act. In this way, it can play a pivotal role in discharging its duties with adequate competency and have the services of expert regulatory staff members, further supported by funding agencies and technologically efficient physical facilities.