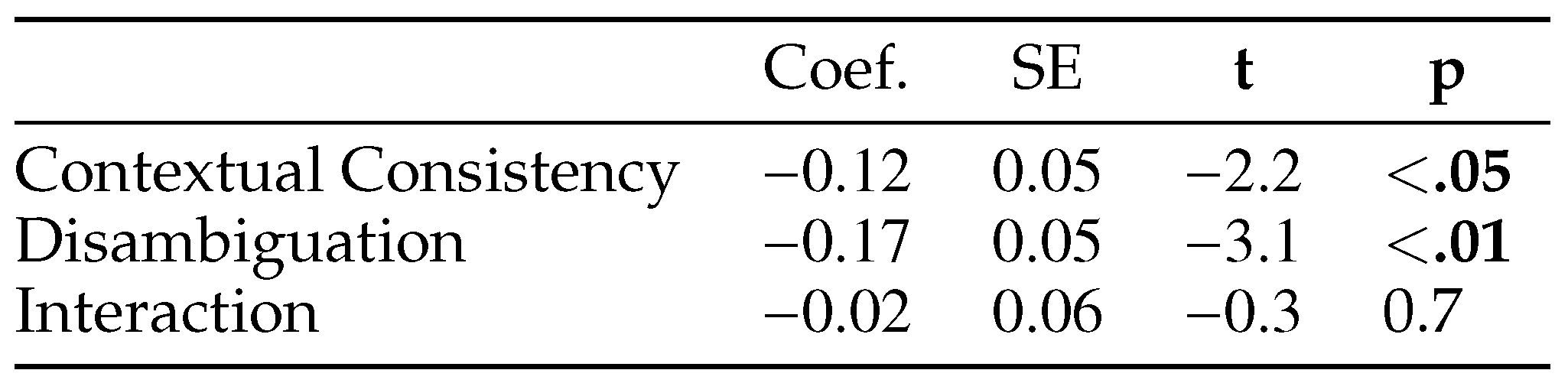

One theoretical account which can be readily ruled out in light of these results is the garden-path model. Traditional garden-path theory predicts that the temporal reading of nicht mehr should be initially adopted in all cases; as the temporal reading is consistent with initial stress on the following verb, no prosodic effects are predicted. The sustained effects of verb stress found in our data clearly contradict this account.

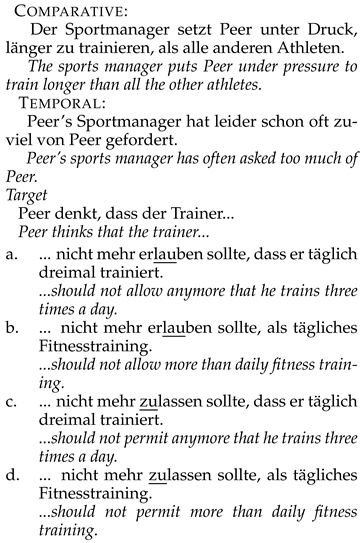

The constraint-satisfaction model which originally motivated the present study finds limited support in the form of an interaction on first-pass reading times at the point of disambiguation; however, the bulk of the data is inconsistent with this model’s predictions. The central prediction of the constraint model is an early, competition-driven effect of context at the ambiguous region, here mehr, with spillover effects on the main verb likely. As noted in the section outlining the predictions, this could be realized either as a main effect of context (contextual bias for the comparative reading conflicts with the global preference for the temporal reading: C.1, C.2 > T.1, T.2) or as an interaction (contextual bias for the comparative reading conflicts with prosodic bias for the temporal reading: C.1 > C.2, T.1, T.2), or both; crucially, comparative contextual bias is predicted to lead to longer reading times, as it competes with temporal bias both at the global level of pre-existing lexical and syntactic preference, and at the local level of prosody when the main verb carries initial stress. Notably, contextual bias supporting the dispreferred comparative reading is also expected to lead to slowed reading times on mehr due to the wellestablished subordinate bias effect upon lexical access (Rayner, Pacht, & Duffy, 1994).

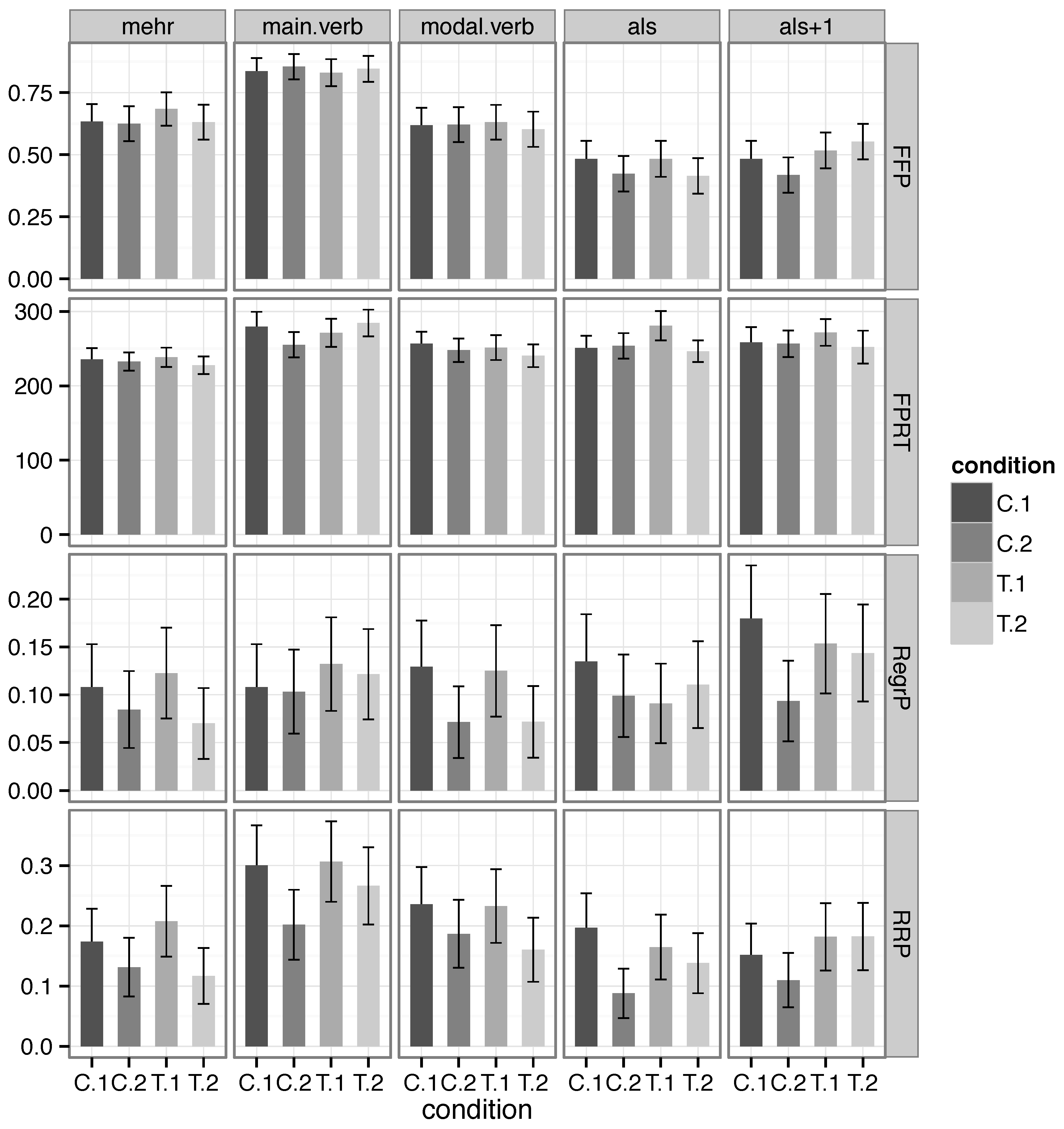

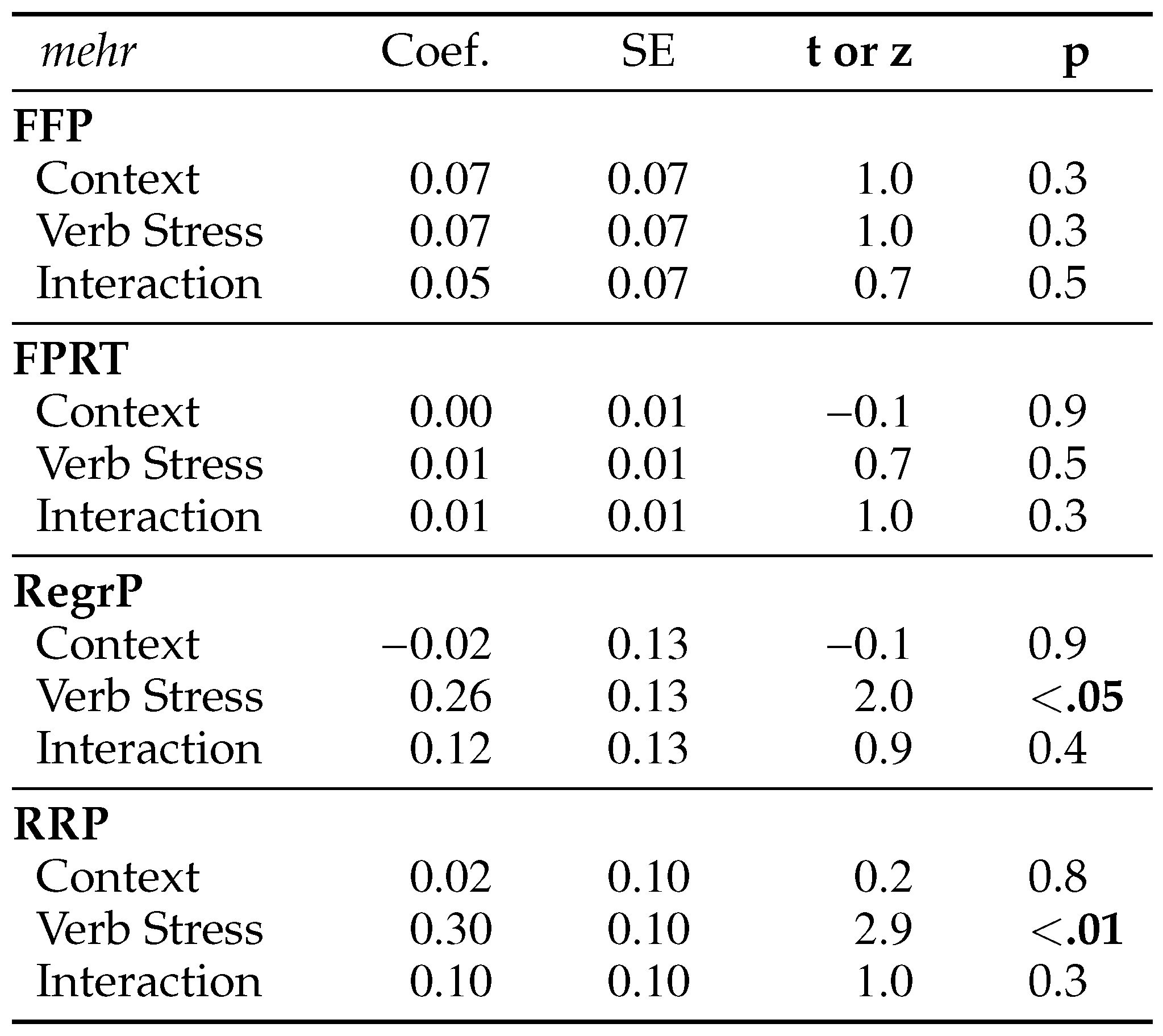

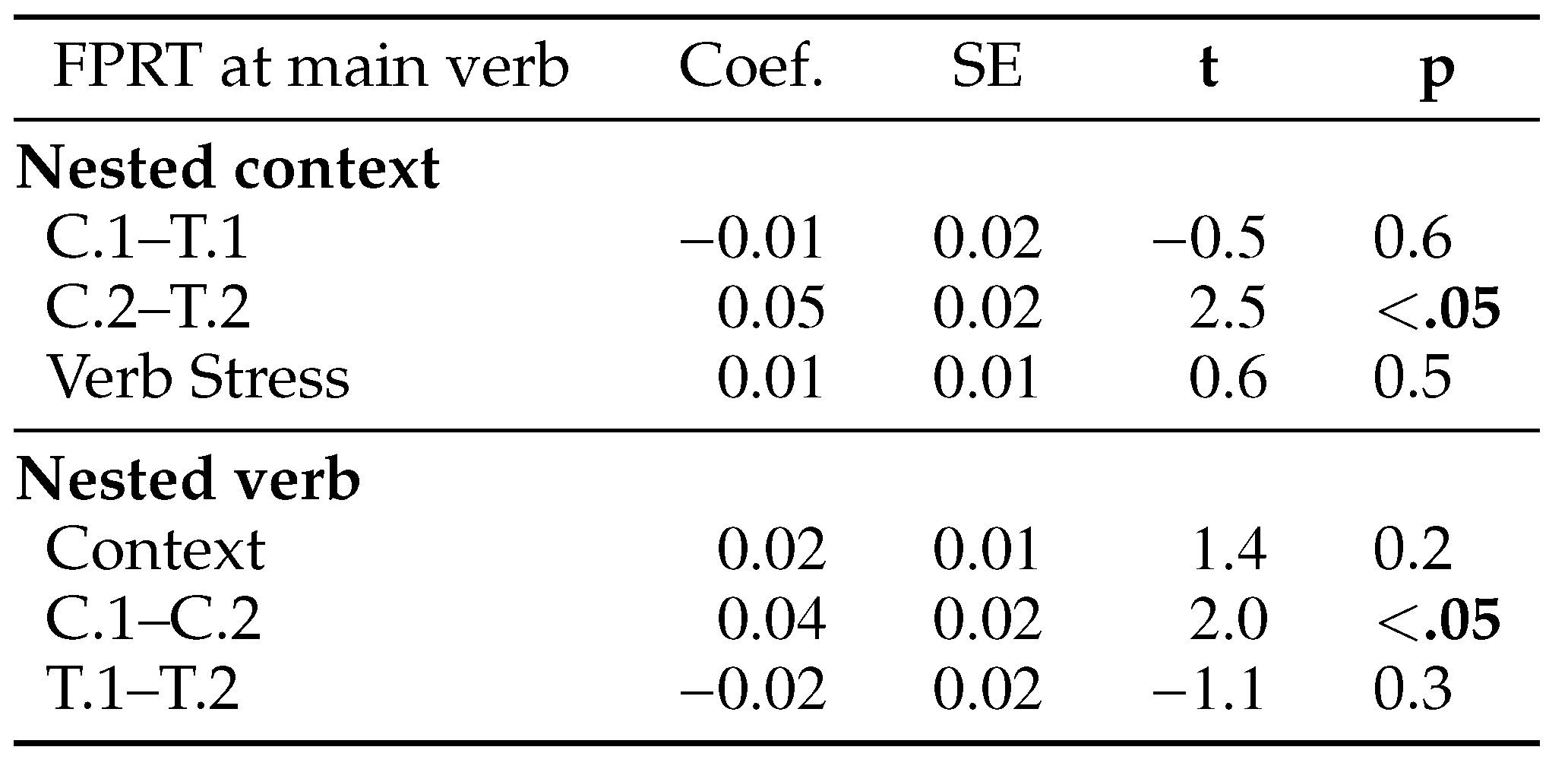

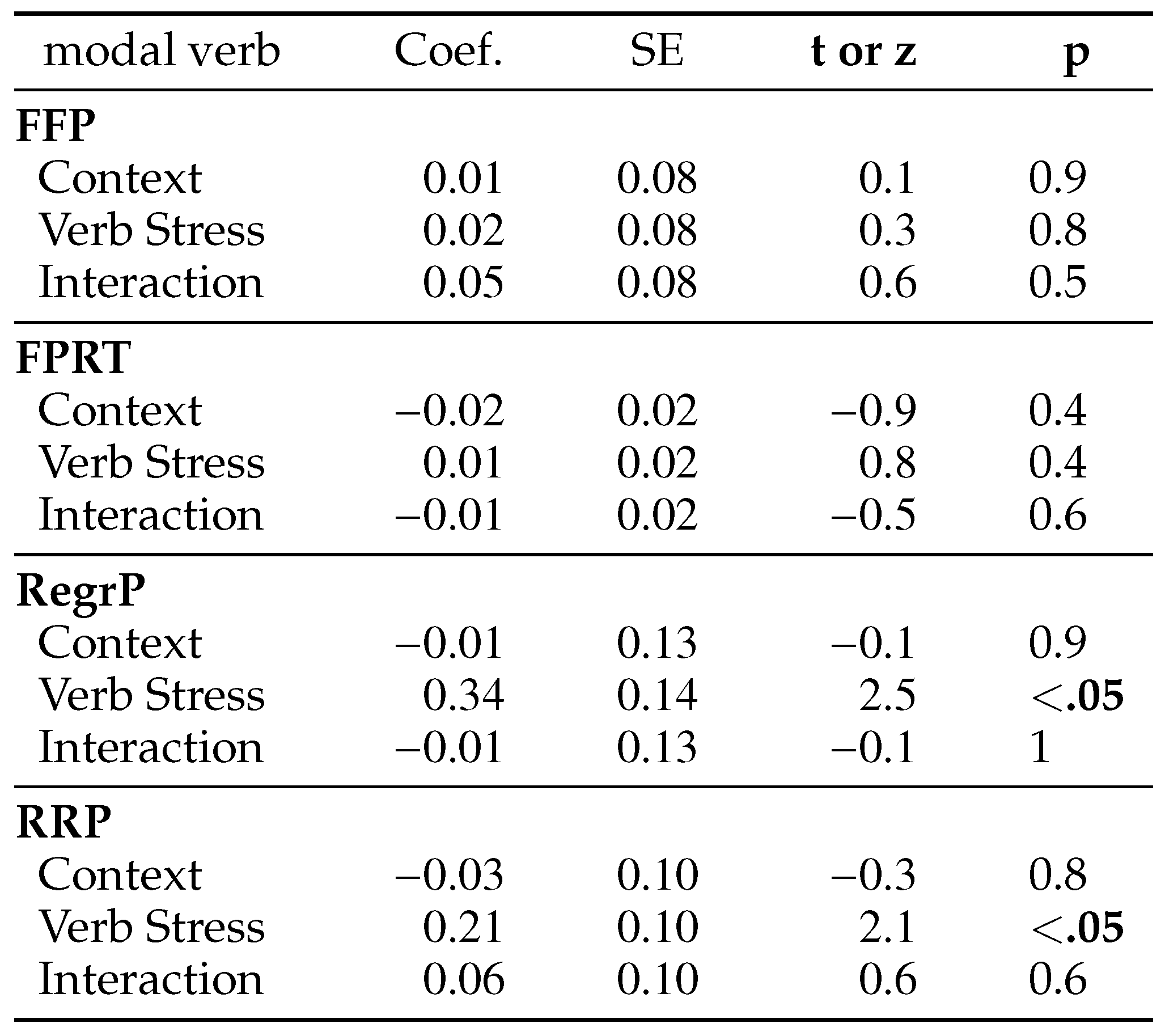

The only region that reflects any influence of context prior to disambiguation is the main verb, which shows a significant interaction between context and verb stress for first-pass reading times. This interaction, however, goes in a different direction from that predicted by the constraint model: post-hoc comparisons reveal that significantly longer reading times in condition T.2 relative to C.2 drive the result, while C.1 and T.1 show no reliable differences with any other condition. A disadvantage for contextual bias that supports the globally preferred temporal reading, alongside an advantage for contextual bias toward the dispreferred comparative reading, is completely unexpected under the constraint model. Moreover, the early effects of verb stress in regression probability on mehr and the modal verb are inexplicable in terms of competition. As the prosodic temporal bias produced by initial verb stress is wholly consistent with the global preference for the temporal reading, competition should be reduced, if anything, in the presence of initial verb stress; instead, regression probability appears to reflect increased processing difficulty in exactly those conditions.

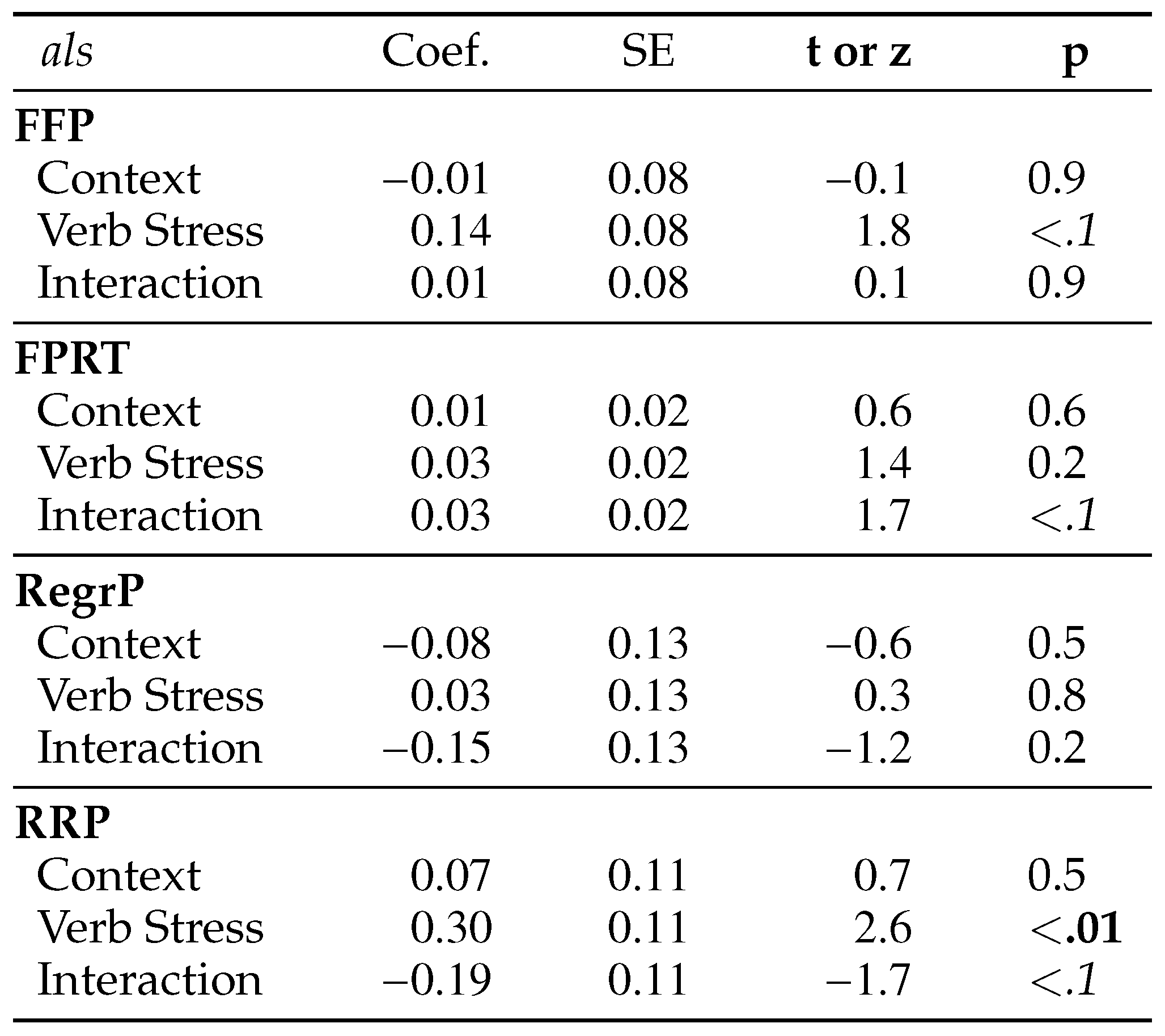

The sole piece of evidence for the constraint-based model’s predictions regarding the influence of context is the statistically marginal interaction on first-pass reading times at als, the point of disambiguation. Als is read on average 30 ms slower in condition T.1 compared to the other three conditions. This result is consistent with an interpretation in which the earlier contextual bias in condition C.1 successfully activated the comparative reading despite a prosodic bias toward the temporal reading, leading to reduced competition at als relative to condition T.1, in which both contextual and prosodic biases toward the temporal reading conflict with the ultimate comparative disambiguation. Nevertheless, this account is undermined not only on the grounds of statistical uncertainty, but also on evidence from second-pass measures of processing. A main effect of verb stress on re-reading probability indicates that als is significantly more likely to be re-read in initial verb stress conditions, and an additional marginal interaction reflects the fact that condition C.1 actually shows the highest rate of re-reading. Another issue for the interaction on first-pass reading times at als is the unexpected absence of a difference in reading times between T.2 and C.2 — if the influence of context is strong enough to modulate prosodic bias in initial verb stress conditions, its effects should appear in the absence of prosodic bias as well. Overall, the data is difficult to reconcile with any analysis in which a comparative contextual bias manages to switch off the prosodic garden path.

Thus, the main conclusion from our work is that implicit meter plays a strong role in guiding parsing, and this effect of implicit meter is insensitive to higher-level constraints. In the remainder of this discussion, we outline a post-hoc explanation for the results.

A post-hoc explanation in terms of the unrestricted race model

Is there any model which captures the observed pattern of results? We think a case can be made for a variation on the two-stage model, namely the unrestricted race model (

Traxler et al., 1998; Van Gompel, Pickering, & Traxler, 2001). Our account is post-hoc, and relies upon a couple of additional assumptions, justified below. Nonetheless, it strikes us as the most parsimonious way to describe these results within an existing theoretical framework.

The unrestricted race model is a modified two-stage reanalysis model in which the initial parsing process is probabilistic and unrestricted: the parser draws on all available sources of information in constructing the initial parse, and the analysis assigned to a given structure may vary based on a range of constraints. Encountering an ambiguity triggers a race in which both potential grammatical structures are built up simultaneously. As soon as one of the processes finishes, the resulting parse is adopted as the parser moves forward in the sentence. Because the process is non-deterministic, while the preferred parse is generally constructed the fastest and therefore wins the race, the dispreferred parse is adopted on some non-zero proportion of trials. For this reason, ambiguous structures are considered as easy or easier to process (

Logačev & Vasishth, 2013) than those which are disambiguated, as ambiguous structures are consistent with any grammatically possible analysis the parser may have initially chosen. In other words, the unrestricted race model posits a penalty for disambiguation.

The first assumption necessary to support our application of the unrestricted race framework to these data is the conjecture that the parser treats implicit prosodic information as if it were disambiguating — that is, upon reaching the initially-stressed syllable of the main verb, stress clash avoidance leads the parser to respond as if

nicht mehr has been disambiguated to the temporal reading. This claim may appear rather unconventional, as it relies upon the premise that non-syntactic information can induce the parser to reanalyze its existing representation as ungrammatical. This reasoning is not, however, quite as outlandish as it may first appear. For one thing, the extra-grammatical factor of semantic plausibility has been successfully employed to resolve syntactic ambiguity in a variety of studies (e.g., Rayner, Carlson, & Frazier, 1983; Ni, Crain, & Shankweiler, 1996;

Van Gompel et al., 2001). An additional consideration for word-level prosody is that, in spoken language, it is unequivocally disambiguating. In the prepared reading task of Kentner’s Experiment 1 (2012), speakers were given time to read the sentence silently before reading it aloud, so that the ultimate meaning of

nicht mehr was known to them before they began to speak. When followed by a comparative disambiguation,

mehr was accented in 90% of trials; with a temporal disambiguation,

mehr was accented in less than 10% of trials. These findings indicate that the spoken prosody of

nicht mehr is a highly reliable cue to its meaning and structure. Furthermore, in Kentner’s unprepared reading task, when speakers were not aware of

nicht mehr’s final meaning, they were significantly less likely to produce an accent on

mehr when it was immediately followed by a verb with initial stress. This illustrates that the well-established principle of stress clash avoidance in production (

Kelly & Bock, 1988) also guides speakers’ preferences with respect to

nicht mehr. This speaker preference for alternating stressed and unstressed syllables has also been found to affect spoken language perception: listeners interpret acoustically stress-ambiguous syllable strings in accordance with a rhythmic preference for stress clash avoidance (

Dilley & McAuley, 2008;

Niebuhr, 2009). Taken together, it appears that 1) the presence or absence of stress on

mehr in the phrase

nicht mehr is a highly reliable indicator of grammatical structure; 2) speakers reliably avoid stress clash on

nicht mehr, in accordance with the general preference in production; and 3) listeners reliably incorporate the preference for stress clash avoidance into their interpretation of ambiguous syllable sequences. The combination of these related pieces of evidence suggests that, insofar as implicit prosody is speechlike, it isn’t so unreasonable to imagine the parser treating the presence of a stressed syllable directly following

mehr, with its implied stress clash, as the silent yet effective analog of a broadly valid acoustic cue to syntactic structure (This argument for prosodic disambiguation draws heavily upon the reasoning of cue validity, positing that stress is a reliable cue to local structure. Similar reasoning has been used by advocates of the constraint-satisfaction approach to explain apparent asymmetries in the timing of different constraints upon parsing; for example, Spivey, Fitneva, Tabor, and Ajmani account for the delayed appearance of thematic role effects relative to those of lexical subcategorization by noting that “rather than becoming operative at an earlier point in time, subcategorization information may simply provide a probabilistically stronger constraint on grammaticality than thematic role information does” (2002, 219). Such a logic could be used to account for the earlier and stronger effects of implicit prosody within a constraint-based framework, assuming it is probabilistically more valid as a cue to structure than discourse context; however, this account fails to capture the direction of the effect, namely greater processing difficulty when prosody is compatible with the globally preferred reading. The penalty for disambiguation asserted by the unrestricted race model is thus more compatible with the current data.).

Medial verb stress, on the other hand, does not provide such a strong cue. It is more or less compatible with both prosodic realizations and thus both parses. Although prosodic theory stipulates that the counterpart to stress clash known as lapse — two adjacent unstressed syllables — is also dispreferred in production (

Liberman & Prince, 1977), the preference for lapse avoidance is much weaker than that of clash avoidance (Nespor, Vogel, et al., 1989). This is supported by Kentner’s results (2012). In Experiment 2, throughout the disambiguating region, significant effects of verb stress on various dependent measures (skipping, re-reading time, and total fixation time) appeared when the disambiguation was comparative, but not when it was temporal. This indicates that, while initial verb stress produces a temporal bias that clashes when the ultimate reading is comparative, medial verb stress exerts no countervailing bias toward the comparative reading; it is simply neutral. The data from Kentner’s Experiment 1 illustrate this point as well. A model evaluating the likelihood of producing the appropriate prosody for

mehr given the ultimate disambiguation — i.e. accenting

mehr when the final reading was comparative, and leaving

mehr unstressed when it was temporal — found a main effect of disambiguation and a significant interaction of disambiguation and verb stress. The main effect reflected an overall tendency to avoid accenting

mehr, yielding more inappropriate prosodic realizations in comparative-disambiguation conditions. The interaction revealed that initial verb stress increased the rate of inappropriate de-accenting relative to medial verb stress. The absence of a main effect of verb shows that appropriate accent production in temporal-disambiguation conditions was unaffected by verb stress. In both comprehension and production data from this study, prosodic clash avoidance exerted a significant effect when verb stress was initial, while there is scant evidence that lapse avoidance played any role in the medial verb stress conditions.

The implication of this claim is that our experiment’s verb stress manipulation not only alters the implicit rhythm of the sentence at the critical point of syntactic ambiguity, it actually creates an additional disambiguating region in those conditions where stress clash is anticipated. In this interpretation, when the ambiguous word mehr is encountered, the race to construct a suitable parse begins — only to be abruptly halted when the stressed syllable immediately following provides evidence for a temporal reading. Here the sentence is effectively disambiguated to the temporal reading, so the unrestricted race model’s penalty for disambiguation is expected to apply. In contrast, when the following syllable is unstressed, the race is able to run through to completion and one of the two parses is adopted. As medial verb stress is roughly compatible with either prosodic realization (lapse avoidance notwithstanding), the sentence remains locally ambiguous, so the parser is able to proceed without difficulty regardless of which grammatical commitment has been made. In fact, taking into account the possibility of a weak preference to avoid lapse offers a possible explanation for the unexpected interaction on firstpass reading times at the main verb. The verb was read significantly faster in C.2 than in T.2, a finding at odds with the established global temporal bias; however, the slowed reading times on T.2 may reflect an underlying race process which takes longer to complete due to the dispreferred rhythmic lapse that results, while a preceding contextual bias for the comparative reading yields a faster time to completion for the prosodically congruous alternating rhythm in condition C.2. Reading times for the initial stress conditions C.1 and T.1 are slower than C.2 and statistically indistinguishable from each other and condition T.2, a finding that is compatible with difficulty stemming from implicit prosodic disruption of the race process.

The second assumption in this account is that the early effect of verb stress upon regression probability at

mehr, the ambiguous word, reflects parafoveal access to the initial syllable of the critical verb that immediately follows. This assumption is independently motivated in previous work by

Ashby and Martin (

2008), among others. Each main verb in the current experiment began with a 2-4 character prefix which is either obligatorily stressed or obligatorily unstressed according to the morphology of German verbs; thus, visual access to the initial syllable alone was sufficient to determine the presence or absence of stress clash in each trial.

Ashby and Martin (

2008) found converging evidence from a lexical decision task and an ERP experiment indicating that the prosodic structure of an initial syllable is reliably accessed during parafoveal preview. The parafoveal interpretation of the verb stress effect on

mehr is also consistent with the findings of

Breen and Clifton (

2011), who found evidence for parafoveally triggered implicit metrical reanalysis occurring on the prosodically and syntactically ambiguous word itself, while syntactic reanalysis in the absence of prosodic ambiguity occurred in the disambiguating region as expected (Note that, without further investigation, one cannot rule out an alternative explanation for the parafoveal effect: mislocated fixations (Drieghe, Rayner, & Pollatsek, 2008). Participants could have intended to fixate the main verb but saccadic error could result in their eyes falling on the preceding word; alternatively, measurement error in the tracker could be responsible for this effect. Given that the verb was skipped approximately 15% of the time (see below), these are possible explanations for the effect. We are grateful to a reviewer, Erik Reichle, for pointing this out.).

These two assumptions motivate and reinforce each other: parafoveal access would explain why verb stress effects appear before the verb itself, and prosody as disambiguation would explain the unexpected direction of the effect: more regressions observed when there is a prosodic bias consistent with the global preference for the temporal reading. Of the two, parafoveal access is probably more plausible, which is fortunate, because this assumption is also necessary under other analyses. To abandon the prosody-as-disambiguation interpretation and exclude the verb stress effect upon regressions at mehr as statistical noise would still leave the main effect of verb stress at the modal verb immediately prior to syntactic disambiguation to be explained. In the absence of any reason to assume a global processing cost associated with initial stress on the main verb, this effect is explicable only in terms of parafoveal access of als conflicting with an earlier, prosodically-driven temporal reading of mehr.

Moving forward with the assumptions and analysis outlined above, upon reaching als, syntactic disambiguation occurs in all conditions toward the globally dispreferred comparative reading, but for initial verb stress conditions this is actually the second time that disambiguation occurs. Whereas nicht mehr had earlier appeared to resolve to the temporal reading due to prosody, it is now reanalyzed as comparative; hence, processing difficulty is observed at als and the word immediately following. Context may be expected to show an effect at this region in initial verb stress conditions as well, as the unrestricted race model, like the garden-path model, includes a role for context in guiding reanalysis; however, this effect may not be very large, owing to the earlier analysis in favor of the temporal reading. In contrast, for the medial verb stress conditions, als represents the first point of disambiguation. The penalty for disambiguation is thus anticipated here, and context is expected to guide reanalysis as well, likely to a larger degree than in the initial stress conditions, as there has been no prior resolution to the alternative reading.

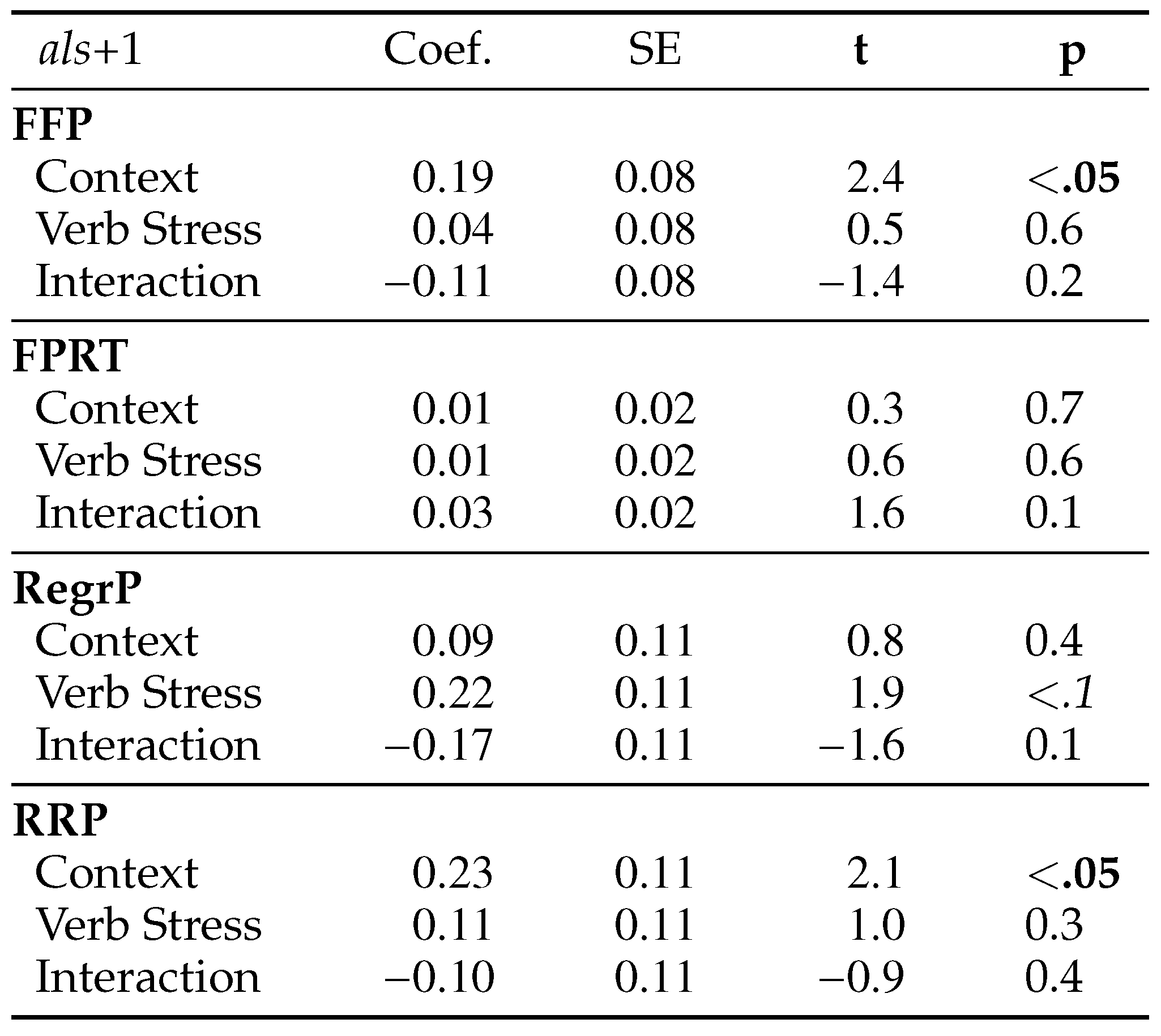

This account successfully captures the pattern of results observed at the point of disambiguation (Note, however, that the race model as originally proposed assumes that all sources of information are used immediately, so it predicts early effects of context. Thus, our assumption that context mainly has an effect on reanalysis is a departure from the original model.). The continuing influence of verb stress is reflected in marginal main effects on two early measures of processing: first fixation probability at

als, and regression probability at

als+1. The additional cost of prosodic reanalysis on top of syntactic reanalysis (

Bader, 1998;

Breen & Clifton, 2011) is evident in the second-pass measure of re-reading probability, which shows reliable main effects of verb stress on each region from

mehr up to and including

als. The anticipated effects of context are also apparent at the second word of the disambiguating region, where both first fixation probability and re-reading probability show main effects of context in the predicted direction. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons within both of these dependent measures reveal the expected asymmetry of this main effect — in both instances, the effect is driven by a significant difference in the medial stress conditions, so that the contextual facilitation for C.2 relative to T.2 is much greater than that of C.1 relative to T.1.

Another possible interpretation of the results presented here posits a privileged role for lexical information in online processing. This concept is reflected in the modified constraint-based model proposed by Boland and colleagues (

Boland & Cutler, 1996), which claims that lexical constraints determine the initial generation of syntactic and semantic structures, and other constraints then select between the generated alternatives. The early effects of lexical-level verb stress and later effects of discourse context in our experiment do appear to mirror the early effects of lexical frequency and later effects of context found in Boland and Blodgett’s study of ambiguous noun-verb homographs (2001); however, insofar as the stress clash avoidance found in our study is a supralexical rather than strictly lexical phenomenon, the precise relation of our results to this model’s predictions is difficult to determine. Nonetheless, the core claim that lower-level cues which form bottom-up constraints upon syntactic structure may have a special role in parsing is compatible with our findings (cf. Snedeker & Yuan, 2008, for a related account of processing in development).

Regardless of whether the unrestricted race analysis presented above is ultimately borne out, the pervasive effects of implicit prosody found in both early and late stage dependent measures in the eye-movement record point to the need for new theoretical frameworks, ones which admit the possibility of implicit prosodic influence upon the earliest stages of syntactic parsing. The consistent main effects of verb stress in re-reading probability are particularly striking. While the effects of context observed following als suggest that global discourse bias does play a role in guiding reanalysis, implicit prosody emerges as the dominant factor in readers’ decisions to re-visit the ambiguous region. These results speak against the possibility that a global contextual bias (at least, as construed in the present study) can eliminate a local prosodic garden path. When it comes to parsing syntactic structure, it appears that prosody not only follows syntax, but sometimes leads — even when this means leading in silence.