Chin IX: Unusual Soft Tissue Problems of the Lower Face

Abstract

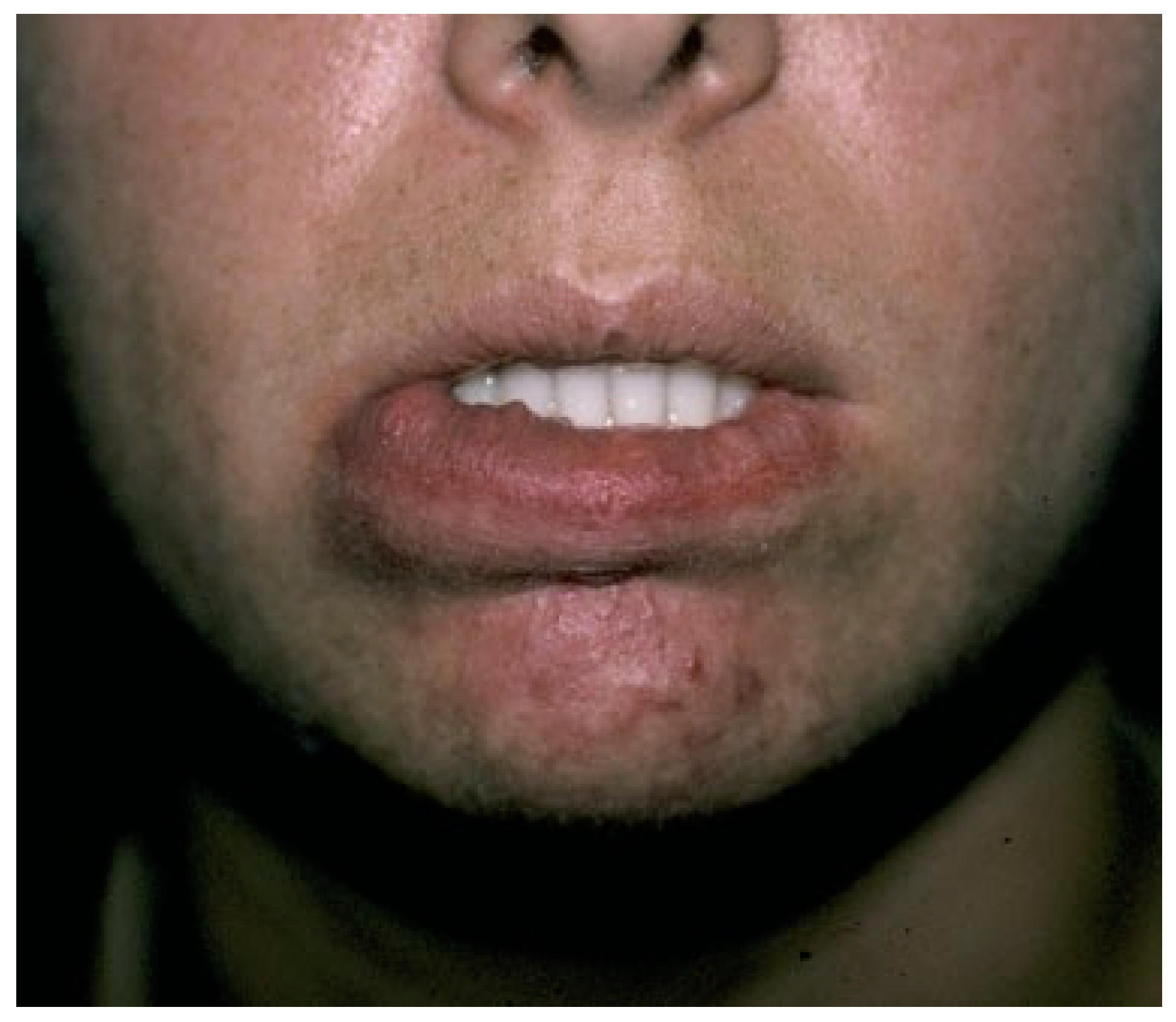

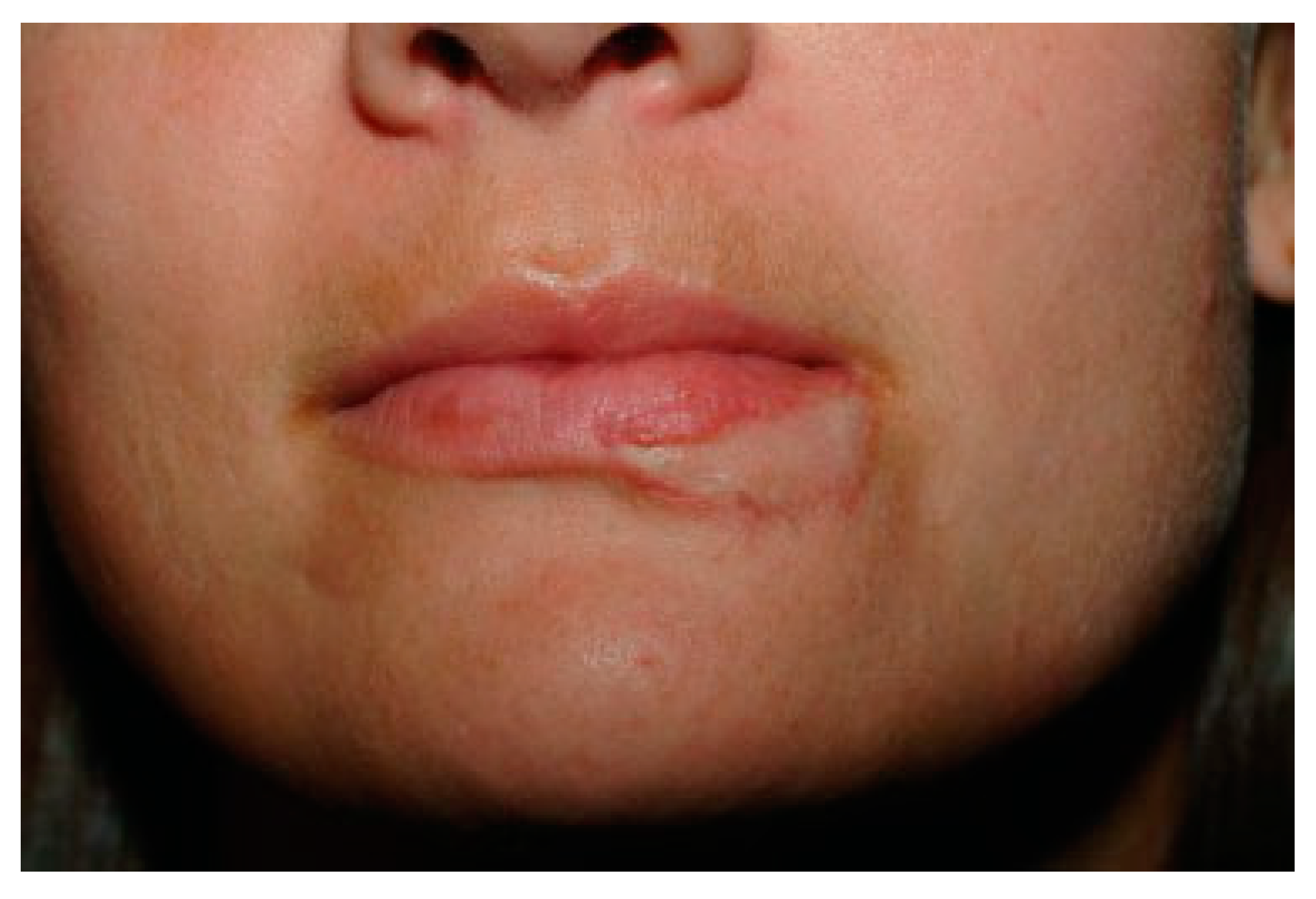

:Case 1: Port-Wine Stain Macrocheilia Overresected—Where do You Get Tissue?

Problems

- Deficiency of the vermillion on the left side of the lower lip.

- Excess horizontal length of the lower lip.

- Incisor show.

Reconstructive Plan

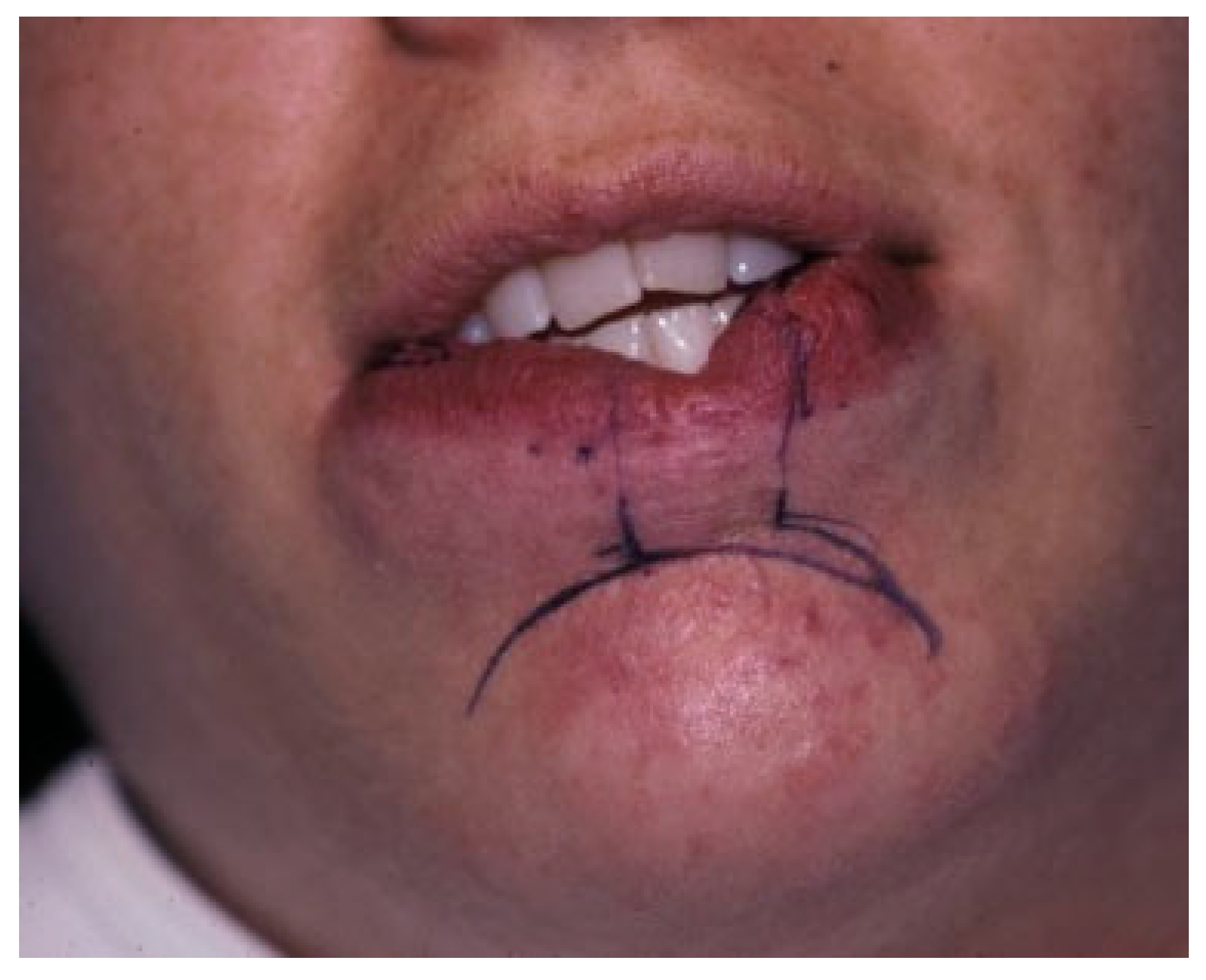

- 4.

- Restoration of the left lower-lip vermillion deficit with an ipsilateral, interior, Abbe flap transposed 90 degrees to the left.

- 5.

- Resection of excess horizontal lower lip and donor defect from Stage 1.

Stage 1

Stage 2

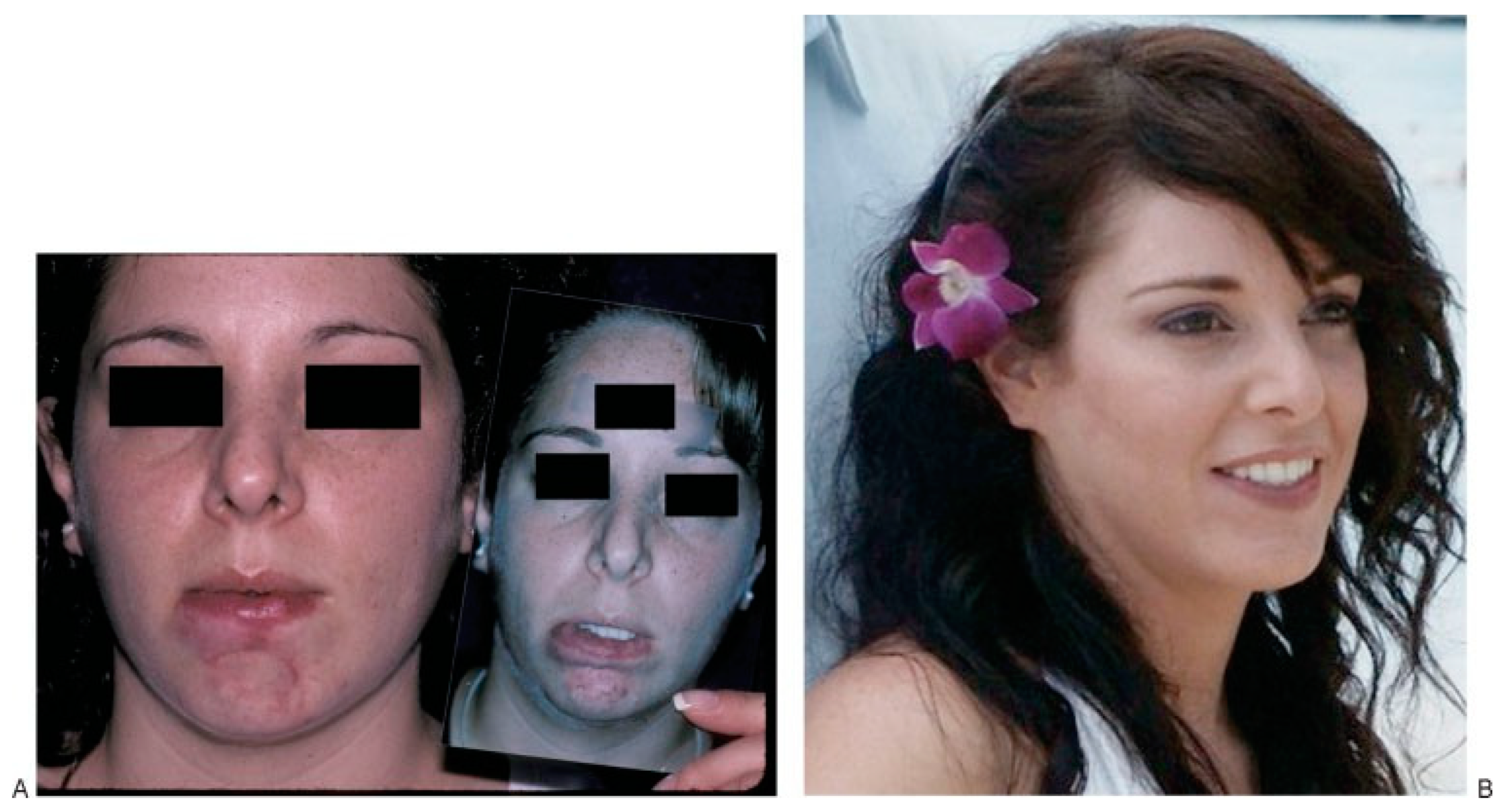

Result

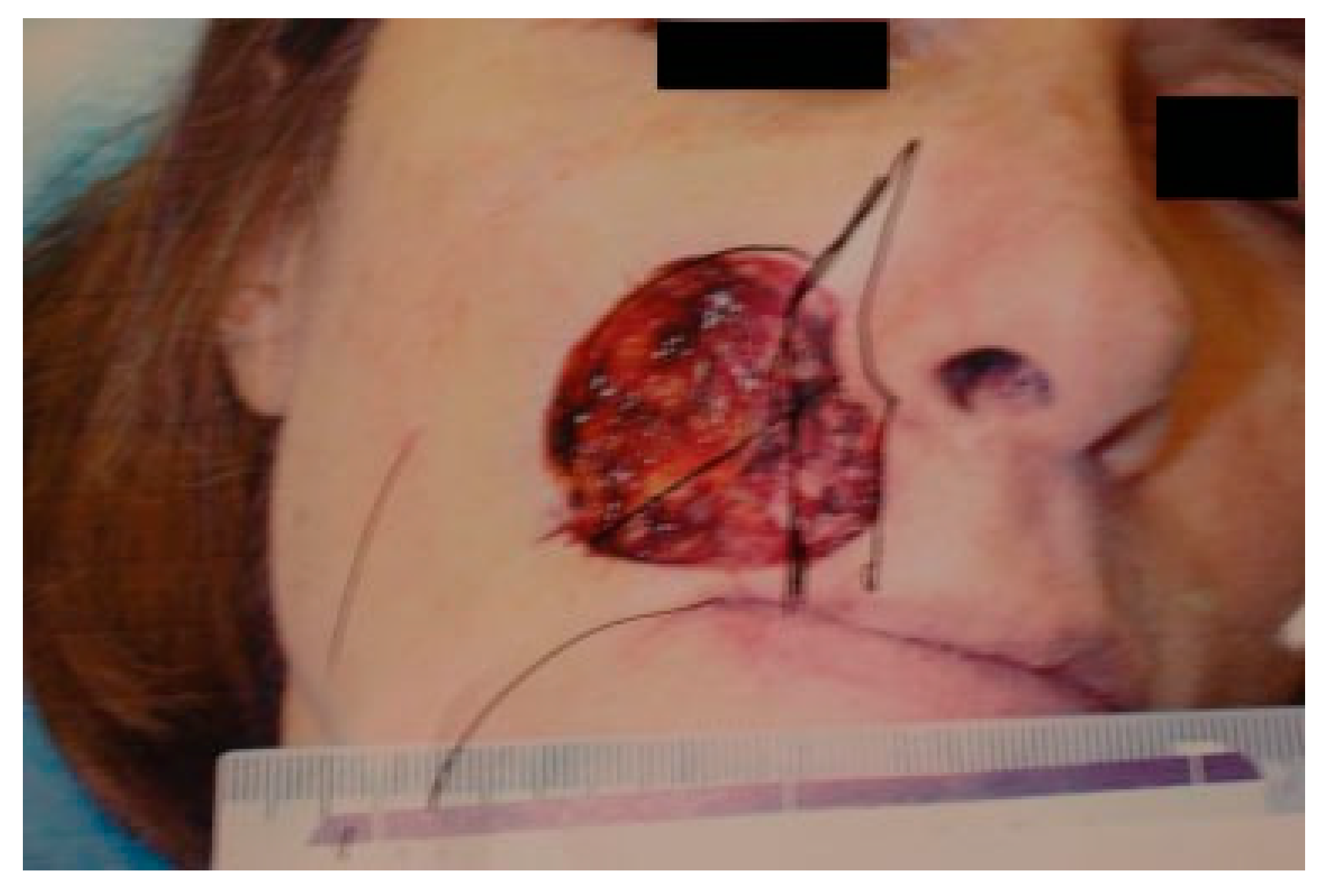

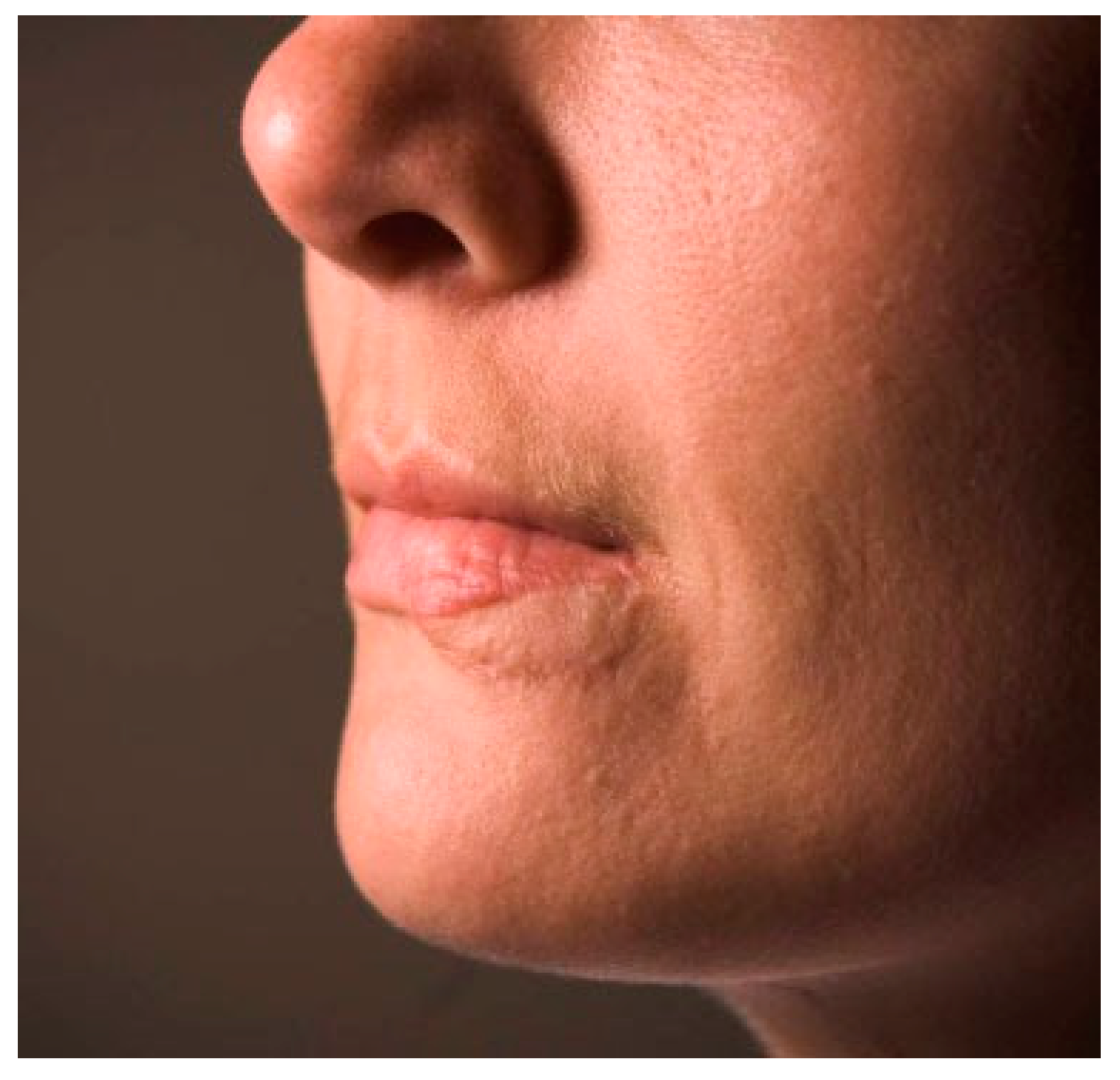

Case 2: Expanding the Reach of the Deep-Plane Schrudde Flap

Problems

- Large upper-lip soft tissue defect extending onto the cheek with mucosal and skin deficiency.

- Upper-lip retraction.

Reconstructive Plan

- Deep-plane angle-rotation flap to restore the upper- lip defect (Figure 7).

Stage 1

Stage 2

Result

Cases 3 and 4: Precise Reconstruction of the White-Roll

Case 3

Problems

- Obliteration of the white roll.

- Advancement of the vermillion onto the lower-lip skin.

Reconstructive Plan

- Reconstruction of the vermillion/lower-lip skin bor- der exactly with a skin graft.

Stage 1

Stage 2

Result

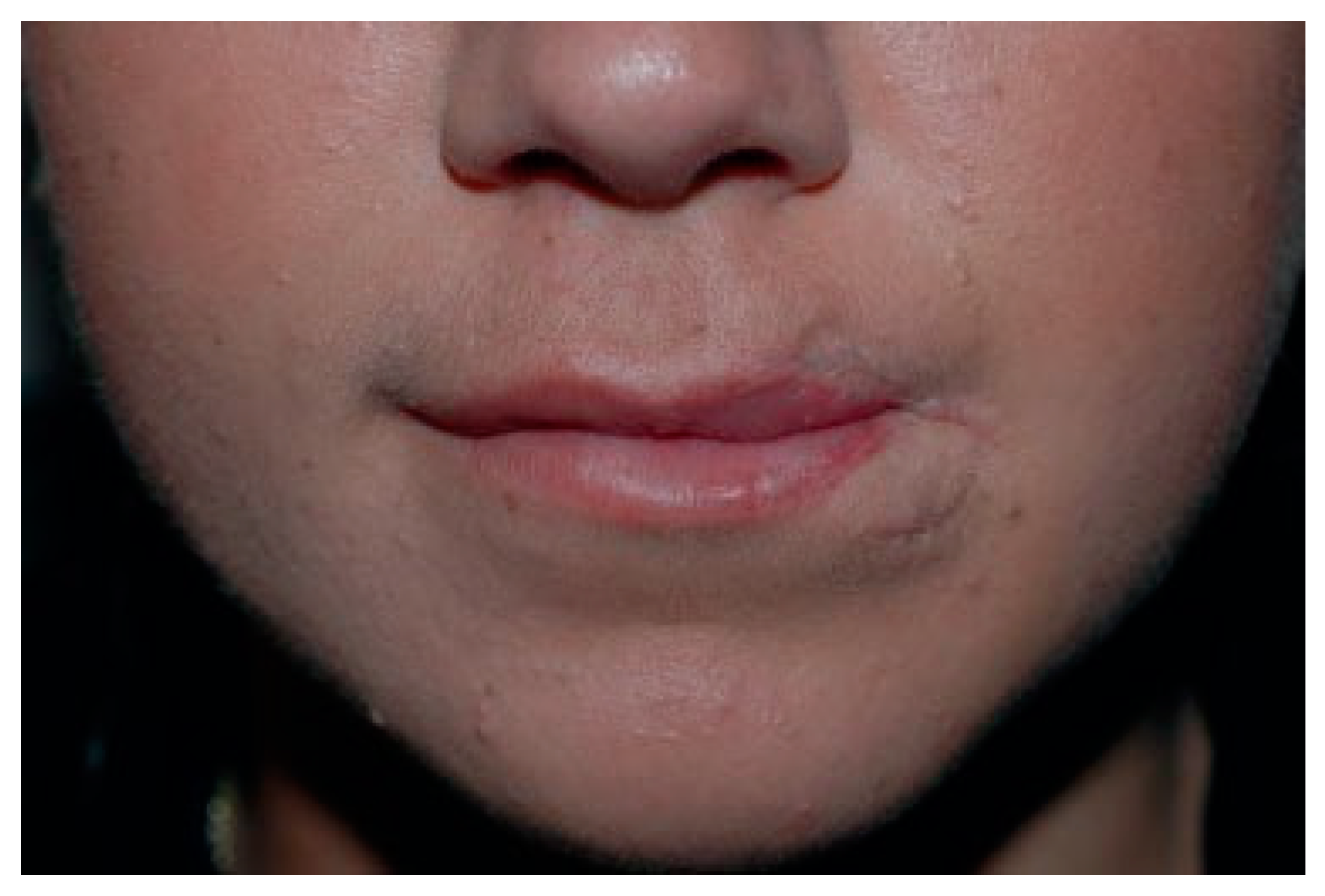

Case 4

Problems (Figure 14)

- Deficiency of upper-lip vermillion lateral to left Cupid’s peak.

- Left lower-lip white roll disrupted.

- Left lower-lip vermillion extending into rounded commissure.

- Contracture of left commissure.

- Tethering of the mucosa posterior to the left com- missure.

Reconstructive Plan

- Composite graft from right lower lip to left upper lip to equilibrate the vermillion.

- Excision of excess left upper-lip skin.

- Two-stage left lower-lip white roll reconstruction with an FTSG graft.

- Excision of scarred mucosa and commissure release followed by local flap reconstruction.

Stage 1 (Figure 15)

Stage 2

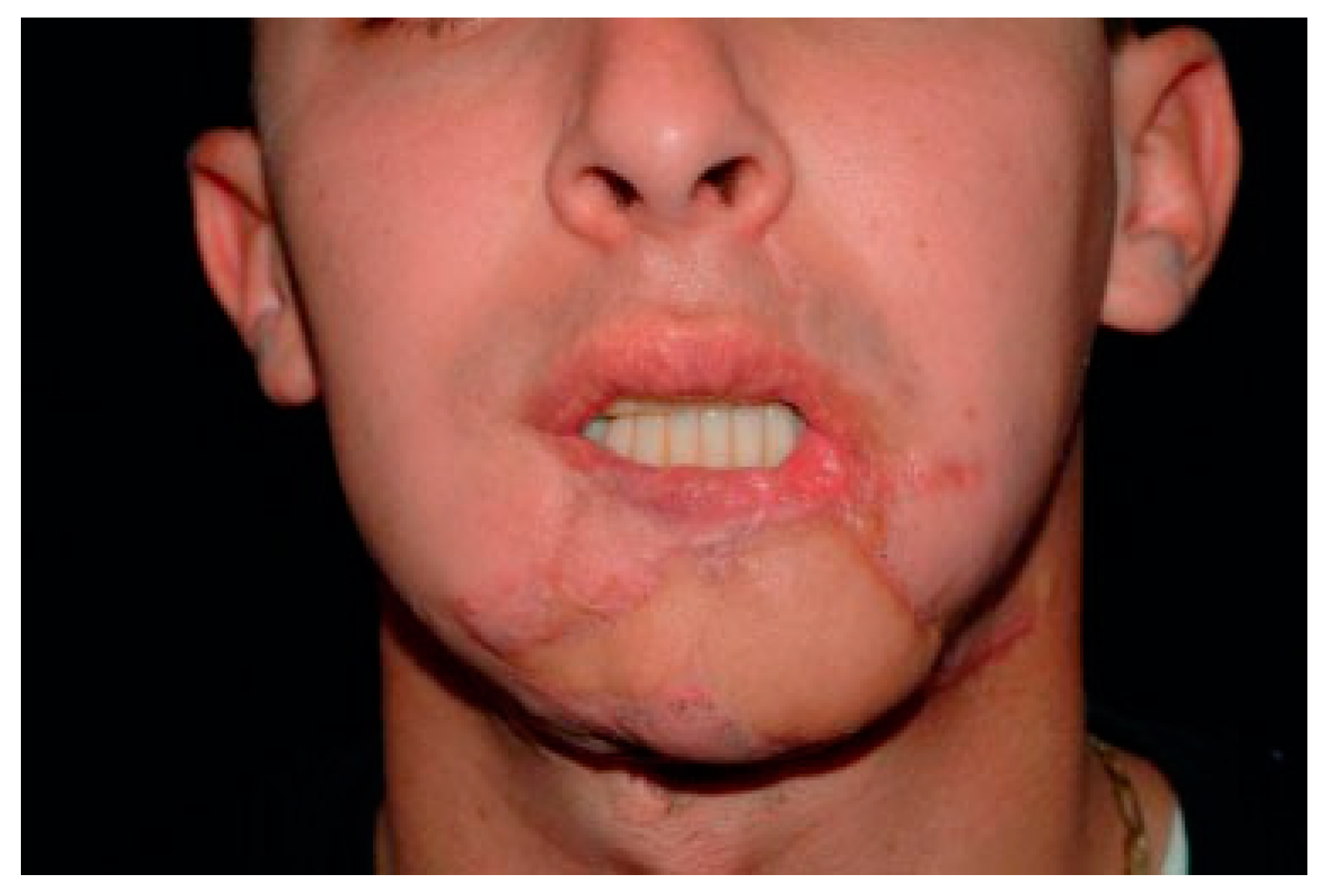

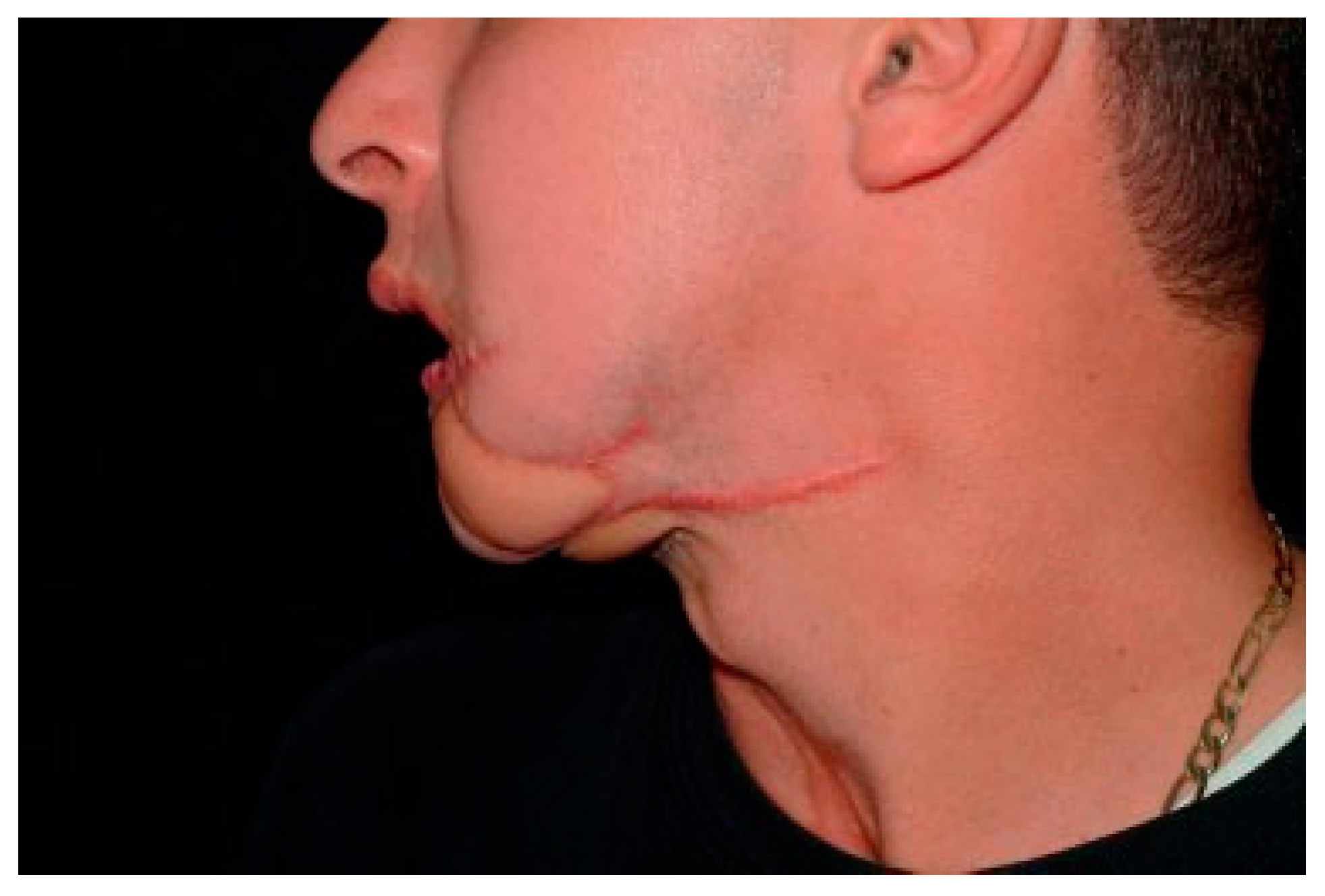

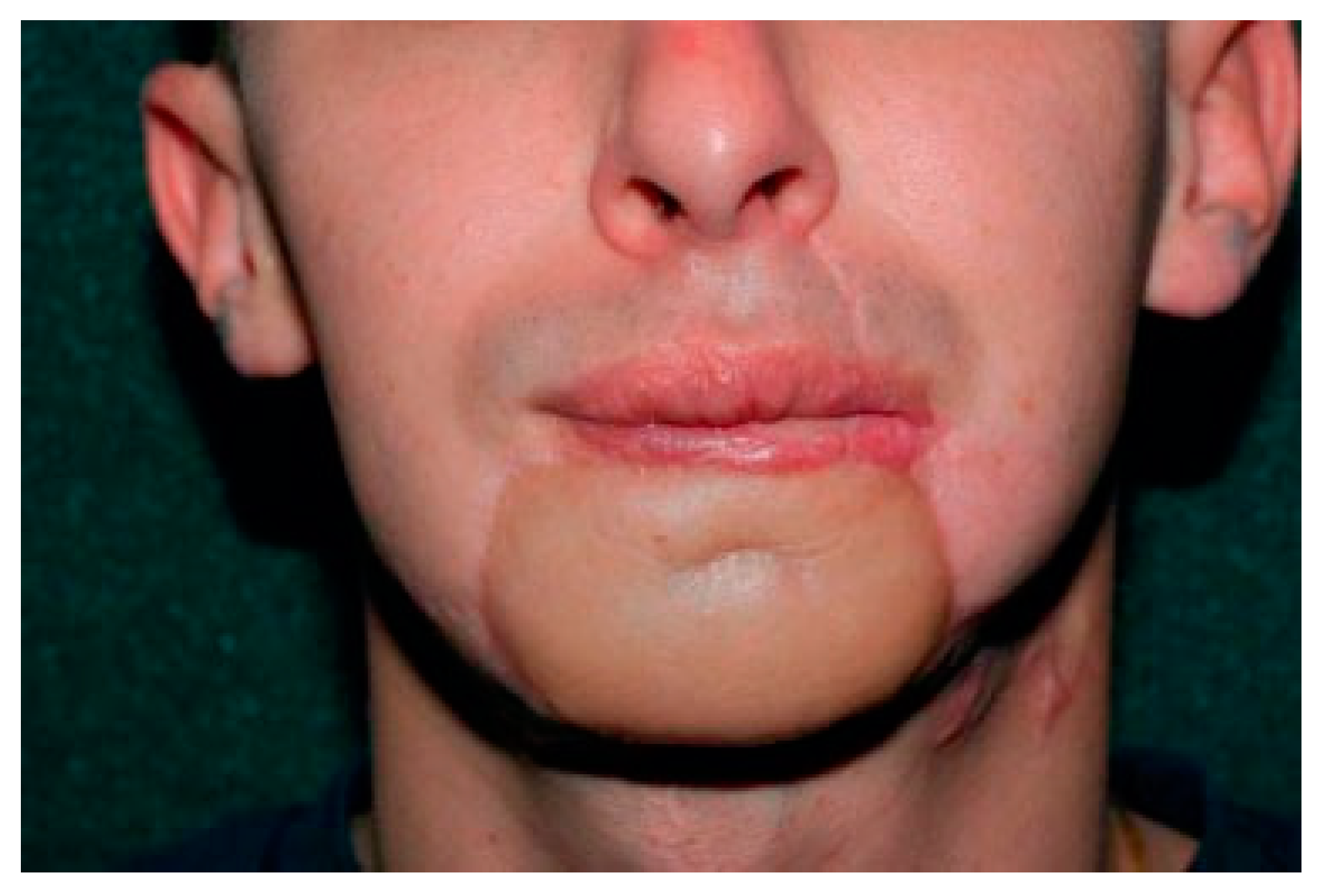

Case 5: Gunshot Loss to Lip and Chin

Problems

- Scarred lower gingivobuccal sulcus resulting in labial incompetence: excessive lower incisor show and per- sistent drooling, requiring him to wear a bib.

- No labiomental sulcus (Figure 20).

- Lack of a chin prominence (Figure 21).

- Subunits of the lower lip and chin disrupted by a patchwork appearance (Figure 19).

- Scarring on the neck and chin from prior flaps.

- Inadequate vermillion.

Reconstructive Plan

- Restoration of the sulcus lining with a thrice delayed extraoral to intraoral turnover flap from the lower-lip skin.

- Formation of a labiomental sulcus.

- Decreased bulking of the chin pad with advanced de- epithelialized submental tissue.

- Resurfacing the lower-lip skin with a second radial forearm flap.

- Restoration of vermillion bulk with a tongue flap.

Stage 1

Stage 2

Stage 3

Stage 4 (Several Procedures)

Stage 5A and B

Result

Summary

References

- Zide, B.M.; Glat, P.M.; Stile, F.L.; Longaker, M.T. Vascular lip enlargement: Part II Port-wine macrocheilia—Tenets of therapy based on normative values. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1997, 100, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boutros, S.; Zide, B. Cheek and eyelid reconstruction: The resurrection of the angle rotation flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 116, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schrudde, J.; Beinhoff, U. Reconstruction of the face by means of the angle-rotation flap. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 1987, 11, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Nakanishi, H.; Urano, Y.; Kubo, Y.; Nagae, H. Lower eyelid reconstruction with a cheek flap supported by fascia lata. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999, 103, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, T.; Yamada, A.; Ueda, K.; Asato, H.; Harii, K. Tissue expansion in facial reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994, 94, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burget, G.C.; Menick, F.J. Aesthetic restoration of one-half the upper lip. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1986, 78, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yotsuyanagi, T.; Yokoi, K.; Urushidate, S.; Sawada, Y. Functional and aesthetic reconstruction using a nasolabial orbicularis oris myocutaneous flap for large defects of the upper lip. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 101, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.C.; Celik, N.; Yang, W.G.; Chen, I.H.; Chang, Y.M.; Chen, H.C. Complications after reconstruction by plate and soft- tissue free flap in composite mandibular defects and secondary salvage reconstruction with osteocutaneous flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2003, 112, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2008 by the author. The Author(s) 2008.

Share and Cite

Flores, R.L.; Zide, B.M. Chin IX: Unusual Soft Tissue Problems of the Lower Face. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2009, 2, 141-150. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1224776

Flores RL, Zide BM. Chin IX: Unusual Soft Tissue Problems of the Lower Face. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2009; 2(3):141-150. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1224776

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlores, Roberto L., and Barry M. Zide. 2009. "Chin IX: Unusual Soft Tissue Problems of the Lower Face" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 2, no. 3: 141-150. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1224776

APA StyleFlores, R. L., & Zide, B. M. (2009). Chin IX: Unusual Soft Tissue Problems of the Lower Face. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 2(3), 141-150. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1224776