1. Introduction

The implementation and impact of inclusivity and accessibility in the banking sector are crucial to its role in achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goals 1, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 16, and 17 (

Jejeniwa et al., 2024;

Atadoga et al., 2024;

Fundira et al., 2024;

Bianchi, 2021). Financial inclusivity involves deliberate efforts to provide equal access to financial services for all individuals, regardless of socio-economic status, physical ability, or cultural background (

Shihadeh, 2022). This includes developing products and services tailored to the needs of marginalised groups such as people with disabilities, low-income earners, and culturally diverse communities.

Accessibility, on the other hand, refers to designing banking services that are usable by a broad range of individuals, especially those with disabilities and those in rural areas (

Mbodj & Laye, 2025;

Reddy, 2025;

Shylaja, 2020). It encompasses inclusive design in digital platforms—such as websites and mobile apps—as well as physical infrastructure like ATMs and bank branches, ensuring ease of use for people with varied functional needs.

The SDGs highlighted above focus on ending poverty, promoting quality education and gender equality, creating sustainable decent work and economic growth, reducing inequalities, and fostering institutional partnerships for sustainable development. As a member of the United Nations, the South African government is committed to implementing these goals, which are also reflected in the country’s National Development Plan (NDP). The NDP emphasises job creation, economic growth, and reducing inequality, objectives that align closely with the SDGs (

Hungwe & Mukonza, 2025;

Modise, 2025;

Farisani, 2022).

This study focuses on banks within the Free State Province of South Africa, chosen for its diverse population and socio-economic landscape. A sample of 208 respondents was drawn using a stratified random sampling technique to reflect the different layers within the banking sector: front-line employees, supervisors, and managers. Data were collected through a Likert-type questionnaire, administered during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although fintech has emerged as a transformative force in advancing financial inclusion and operational efficiency, its alignment with the SDGs and NDP in the South African banking sector remains underexplored. Fintech has the potential to reduce transaction costs, extend the reach of financial institutions, and empower underserved communities (

Kishor et al., 2025;

Li & Yan, 2025;

Danladi et al., 2023). However, barriers to inclusivity and accessibility, particularly for women, youth, and rural populations, continue to hinder progress.

Thus, the problem this study addresses is the limited empirical understanding of how fintech-driven banking practices in South Africa, particularly in the Free State Province, align with SDGs and the NDP, and the extent to which institutional and structural barriers inhibit inclusivity and accessibility for marginalised groups.

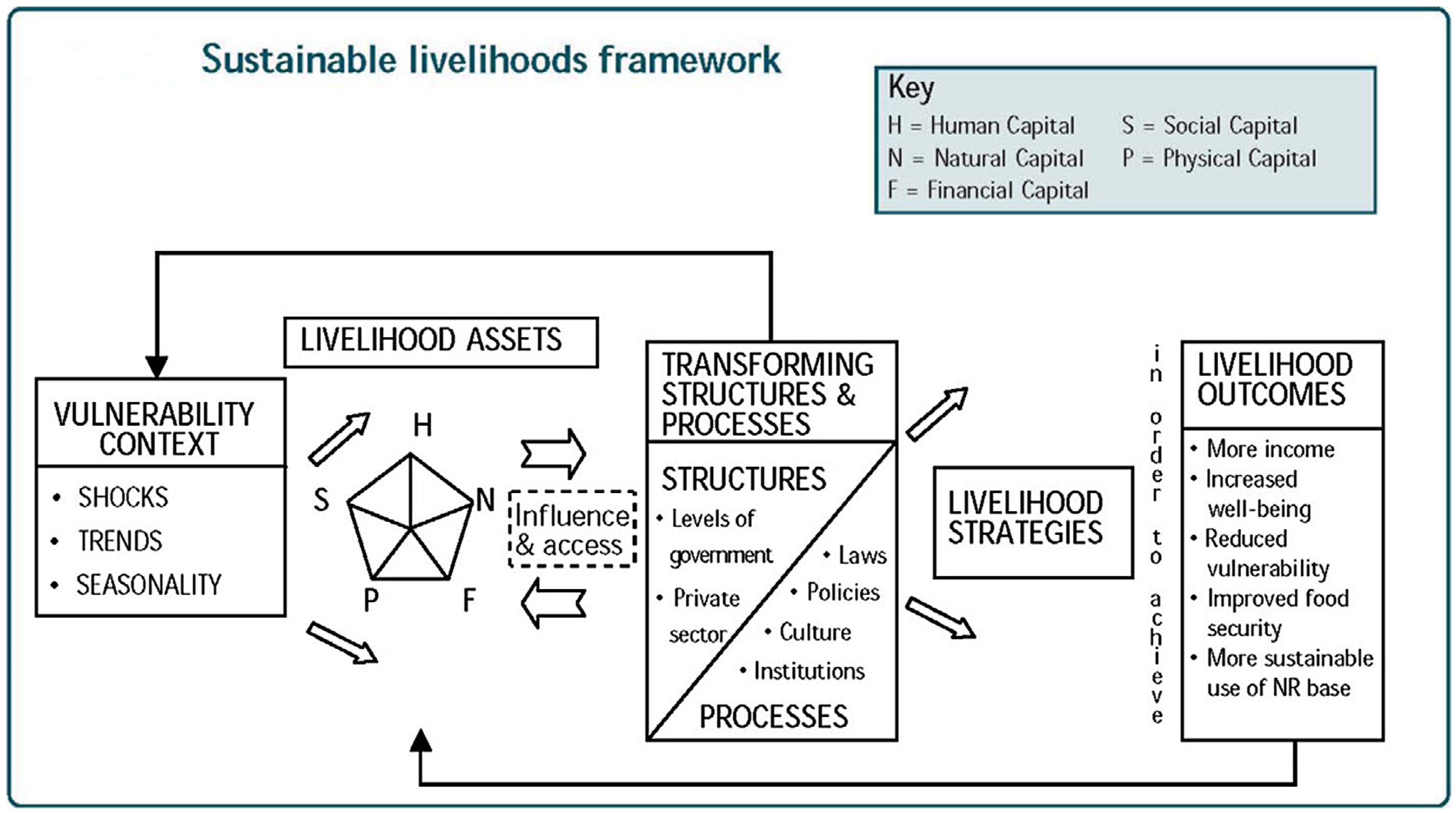

To address this problem, this study draws on the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1) and Institutional Theory. SLF provides insights into resource accessibility and sustainability in SDG implementation (

Smyth & Vanclay, 2017), while Institutional Theory helps examine the regulative and cultural dynamics that shape institutional behaviour (

Palthe, 2014;

Scott, 2013).

Accordingly, this study pursues two key objectives:

To explore the alignment of fintech banking practices with SDGs 1, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 16, and 17.

To identify barriers to inclusivity and accessibility in the banking sector, particularly for women and youth.

2. Literature Review

The literature review section is presented in line with the above-mentioned objectives: to explore the alignment of fintech banking practices with SDGs 1, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 16, and 17 discuss the relationship between SDGs, inclusivity and accessibility while, at the same time, identifying the barriers to inclusivity and accessibility in the banking sector to women and youth.

2.1. Relationships Between SDGs, Inclusivity and Accessibility

The relationships between SDGs, inclusivity and accessibility are elaborated upon below.

According to

Sil and Lenka (

2024), the trajectory toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 5 (Gender Equality), remains sluggish, with only five years left in the 2030 Agenda. Their analysis projects that gender parity in leadership roles within South Africa’s private sector may not be realised for another 140 years. This concern is echoed by

Matotoka and Odeku (

2021), who emphasise the persistent under-representation of women in corporate leadership, despite their demographic majority in the country. Such gender disparities have broader implications for other SDGs—most notably SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities)—as gender equality is a cornerstone of equitable economic development and poverty alleviation.

The emergence of financial technology (fintech) within the banking sector offers a promising avenue to mitigate these inequalities. Fintech has demonstrated potential in advancing financial inclusion, especially for underserved populations such as women, by lowering access barriers and providing customised financial solutions (

Arner et al., 2016;

Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018). As noted by

Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (

2018), digital financial platforms can significantly enhance women’s engagement in formal economic activities, thereby supporting the realisation of SDGs 1, 8, and 10. Furthermore, inclusive fintech applications can contribute to SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by facilitating access to urban financial services, and to SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) by fostering transparency and accountability through digital financial records.

Nonetheless, the persistent gender divide in digital literacy and access remains a formidable challenge. The

UN Women and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (

2023) Gender Snapshot warns that, in the absence of targeted policy interventions, over 340 million women and girls will continue to live in extreme poverty by 2030, and gender parity in leadership may not be achieved until 2050. These projections underscore the urgency of adopting a comprehensive, gender-responsive approach to fintech innovation—one that not only broadens access but also embeds inclusivity and accessibility into the design and deployment of digital financial tools.

2.2. Age and Accessibility in the Context of SDGs

The intersection of age and employment accessibility plays a pivotal role in the realisation of several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). Scholars such as

van Niekerk et al. (

2024), along with

Sumberg et al. (

2021), have extensively examined how age—especially youth status—affects access to employment opportunities and institutional stability in developing contexts. Their findings suggest that youth unemployment is intricately linked to what they term the “troublesome trio”: conflict, crime, and fragile institutions, particularly in low-income and transitional economies.

Betcherman and Khan (

2018) further argue that youth exclusion from labour markets not only perpetuates poverty but also undermines social cohesion and institutional trust, thereby impeding progress toward SDG 16.

Hungwe and Mukonza (

2025),

Modise (

2025) and

Farisani (

2022) add that structural barriers—such as limited access to digital infrastructure and financial services—disproportionately affect younger populations, especially in rural and underserved areas, exacerbating inequalities and limiting their economic participation.

In this context, enhancing accessibility—both in terms of employment and digital financial services—is essential. Fintech solutions, when designed with age-sensitive considerations, can serve as powerful tools to bridge these gaps. By offering mobile-based banking, microloans, and digital literacy programs, fintech can empower youth economically and socially, contributing to poverty reduction (SDG 1), inclusive economic growth (SDG 8), and institutional resilience (SDG 16).

2.3. Education as a Link Between SDGs, Inclusivity, and Accessibility

Education is widely recognised as a foundational enabler of sustainable development, with SDG 4 (Quality Education) serving as a critical nexus for achieving broader social and economic objectives.

Sezgin et al. (

2023) emphasise that quality education is not only a standalone goal but also a catalyst for progress across multiple SDGs, particularly those related to health, economic growth, and institutional development.

Carvalho et al. (

2024) further argue that education influences a wide spectrum of societal domains, including cultural preservation, environmental sustainability, and peacebuilding, all of which are embedded within the SDG framework.

The integration of financial technology (fintech) into educational and economic systems has introduced new dimensions to this discourse.

Noreen (

2024) highlights the synergistic relationship between fintech and the SDGs, noting that digital financial tools can enhance access to education by facilitating mobile payments, micro-scholarships, and digital learning platforms.

Zolfaghari (

2015) supports this view, contending that investing in the education of stakeholders—particularly those involved in deploying fintech solutions—is essential for the effective implementation of SDG-aligned initiatives.

The rapid digital transformation of education, catalysed by the global disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, has brought renewed attention to the imperative of ensuring inclusive and equitable access to educational technologies. As highlighted by

Matsieli and Mutula (

2024), while digital learning platforms have expanded opportunities for many, they have also exposed and, in some cases, deepened existing inequalities—particularly among students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The shift to online education during the pandemic revealed significant gaps in infrastructure, digital literacy, and institutional preparedness, which disproportionately affected marginalised populations.

Jimenez-Pitre et al. (

2022) emphasise that although digital tools helped mitigate the educational disruptions caused by lockdowns, their uneven distribution and accessibility posed serious challenges to equity in learning outcomes. Furthermore, emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence and adaptive learning systems hold promise for enhancing personalisation and inclusivity in education, but their benefits remain contingent on equitable access and institutional support.

These developments align closely with the broader objectives of SDG 4 (Quality Education), which advocates for inclusive and lifelong learning opportunities for all. Ensuring that digital education strategies are designed with accessibility and equity at their core is essential not only for educational advancement but also for achieving sustainable development across interconnected domains.

Theoretical frameworks such as the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework and Institutional Theory offer valuable lenses through which to understand the role of education in advancing SDGs. The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework emphasises the importance of human capital—of which education is a core component—in building resilient and adaptive communities. Institutional Theory, on the other hand, highlights how formal and informal structures shape access to education and financial services, influencing the inclusivity of development outcomes.

2.4. Sustainable Livelihoods Framework

“In its simplest form, the framework views people as operating in a context of vulnerability. Within this context, they have access to certain assets or poverty-reducing factors. These gain their meaning and value through the prevailing social, institutional and organizational environment.”

This conceptualisation facilitates a nuanced understanding of the interplay between implementation, inclusivity, and access. The framework’s design, characterised by interconnected components and directional arrows, visually represents the dynamic relationships among its elements.

The SLF comprises five interrelated components: the vulnerability context, livelihood assets, transforming structures and processes, livelihood strategies, and livelihood outcomes. Each component plays a critical role in shaping sustainable development trajectories. For instance, the vulnerability context is particularly relevant to this study as it encompasses emerging trends such as the proliferation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) within the financial technology (fintech) sector.

The livelihood asset component enables an assessment of the resources required to respond effectively to these technological shifts. These resources are typically mobilised through transforming structures and processes, which include institutions such as banks, government agencies, and regulatory bodies. Consequently, the SLF offers a strategic framework for leveraging fintech innovations as catalysts for achieving targeted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), contingent upon the implementation of appropriate livelihood strategies.

The SDGs under consideration, namely, Goals 1, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 16, and 17, focus on eradicating poverty, promoting inclusive and equitable education, advancing gender equality, fostering sustainable economic growth and decent work, reducing inequalities, and enhancing institutional partnerships for sustainable development. The directional arrows within the SLF diagram underscore the interconnectivity among trends, institutional structures, and resource flows, thereby highlighting the imperative of inclusivity and accessibility in the pursuit of these goals.

In summary, the SLF illustrates that the successful implementation of the SDGs necessitates the active involvement of all relevant structures and equitable access to essential resources. This framework thus serves as a valuable guide for aligning technological advancements in fintech with broader sustainable development objectives. Relationships between relevant structures/institutions necessitate the use of Institutional Theory.

2.5. Institutional Theory

Institutional Theory offers a valuable lens through which to examine the relationships among key institutional actors and to identify optimal strategies for implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As

Ramabodu et al. (

2024) emphasise, the relevance of Institutional Theory lies in its capacity to illuminate the processes of implementation across collaborating institutions. This perspective is further supported by

Khomo et al. (

2023), who highlight the theory’s foundational elements, namely, the regulative, normative, and cultural–cognitive dimensions (see

Table 1).

Recent research has underscored the particular significance of the cultural–cognitive element in the context of SDG implementation amid the growing influence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) in the fintech sector (

Noreen, 2024;

Carvalho et al., 2024).

Table 1, adapted from the work of

Palthe (

2014), provides a comparative overview of these three elements, with a focused analysis on the cognitive dimension.

From the vantage point of the cultural–cognitive element, which encompasses system transformation drivers and sustainers, it becomes possible to assess the feasibility of SDG implementation by banking institutions in an era dominated by AI and 4IR technologies. This assessment hinges on a deeper understanding of stakeholder behaviour, particularly the reasoning processes, transformation values, and identity constructs of bank employees and other key actors.

Three critical factors emerge in this regard:

Internalisation of transformation values: the extent to which stakeholders embrace and integrate values aligned with sustainable development and technological innovation.

Social identification with AI and 4IR: the degree to which stakeholders perceive alignment between their professional roles and the technological paradigms shaping fintech.

Motivational desire to implement SDGs: the willingness of stakeholders to actively pursue SDG-related initiatives as part of their institutional mandate, recognising the strategic advantage this confers in a competitive fintech landscape.

Therefore, Institutional Theory, particularly its cognitive dimension, provides a robust framework for evaluating the institutional readiness and strategic alignment necessary for effective SDG implementation in technologically advanced financial environments.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study was guided by a quantitative research framework, underpinned by a deductive approach within the positivist paradigm. This design was selected to facilitate the examination of relationships and patterns through numerical data, enabling generalisation of findings to a broader population. The deductive strategy aligns with the use of structured instruments, such as surveys and questionnaires, which are effective in capturing quantifiable data (

Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

3.2. Population and Sampling Strategy

This research was conducted within a retail banking institution in the Free State province of South Africa. The target population comprised 419 employees, categorised into three organisational strata: 125 managers, 69 supervisors, and 225 front-line employees. Due to ethical constraints imposed by the institution, only employees were included in this study, excluding customers from participation. To ensure proportional representation across the organisational hierarchy, a stratified random sampling technique was employed. This method, appropriate for heterogeneous populations, involves dividing the population into distinct subgroups and randomly selecting participants from each stratum (

Taherdoost, 2016). A sample size of 208 was determined to ensure sufficient statistical power for analysis.

3.3. Data Collection

Primary data were collected using a Likert-type questionnaire, designed to measure attitudes and perceptions across multiple constructs. The instrument was developed, piloted, and refined before full deployment. The survey method facilitated efficient data collection from the selected sample, aligning with the study’s quantitative orientation.

3.4. Sample Composition

The final sample consisted of 64% front-line staff, 24% managers, and 12% supervisors, reflecting the operational structure of the institution. The predominance of front-line employees is particularly noteworthy, given their frequent engagement with customers and their pivotal role in service delivery. Insights from this group are therefore essential for understanding customer-facing dynamics within the organisation.

3.5. Data Analysis

Data were processed and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 21. This software enabled the application of appropriate statistical techniques to examine the data and draw valid inferences.

3.6. Validity and Reliability

To ensure the validity of the research instrument, both content validity and construct validity were assessed. Content validity was established through expert review, ensuring comprehensive coverage of this study’s conceptual dimensions. Construct validity was evaluated to confirm alignment between the questionnaire items and the theoretical constructs under investigation (

Kumar, 2014).

Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, a widely recognised measure of internal consistency in social and organisational research (

Bonett & Wright, 2014). This test confirmed the reliability of the instrument by evaluating the consistency of responses across related items.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in full compliance with the ethical clearance protocols established by the Central University of Technology. Accordingly, informed consent was obtained from all participants, who engaged in this research voluntarily. The participants were permitted to temporarily suspend interviews to attend to professional obligations, such as assisting customers, with the researcher accommodating such interruptions as needed. Confidentiality was rigorously maintained, and the participants were assured that all data collected would be used exclusively for scholarly purposes.

4. Results and Analysis

This section presents the findings of this study in alignment with its overarching aim: to assess the implementation and impact of inclusivity and accessibility within the South African banking sector. The analysis is guided by two core objectives: (1) to explore the alignment of fintech banking practices with selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically Goals 1, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 16, and 17; and (2) to identify barriers to inclusivity and accessibility for women and youth within the sector. To achieve these objectives, the findings are contextualised within the frameworks of South Africa’s National Development Plan (NDP) and the United Nations SDGs, with particular attention to the theoretical underpinnings of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1) and Institutional Theory. The SLF’s emphasis on human and social resources—two of the five core livelihood assets—provides a lens through which the capacity of banking stakeholders to implement inclusive and sustainable practices is assessed. These resources are critical in understanding how individual and institutional capabilities influence the adoption of fintech solutions and the realisation of developmental goals in the era of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR).

The analysis focuses on key demographic and institutional variables, including education, gender, age, nationality, and training of respondents. These dimensions are instrumental in evaluating the extent to which inclusivity and accessibility are embedded in banking operations and policy implementation. By examining these human resource attributes, this study seeks to uncover structural and operational barriers that may hinder equitable participation and service delivery, particularly for marginalised groups such as women and youth. The results are presented thematically, corresponding to this study’s objectives and theoretical framework, thereby offering a comprehensive understanding of the current state of inclusivity and accessibility in the Free State’s banking sector.

4.1. Gender and Inclusiveness

Gender representation is a critical dimension in evaluating inclusivity within the South African banking sector, particularly in the Free State province. This study considered binary gender categories (male and female) as no respondents identified outside these classifications during data collection. The analysis of gender distribution offers valuable insights into the sector’s alignment with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5, which advocates for gender equality, as well as other interconnected goals such as SDGs 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), 10 (Reduced Inequalities), 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

The findings, as illustrated in

Table 2 and

Figure 2, reveal a female-majority workforce, with 58.1% of respondents identifying as female, compared to 41.9% male. This gender composition suggests that the banking sector in the Free State is making notable strides toward gender inclusivity, positioning itself as a potential benchmark for other industries that continue to face challenges in achieving equitable gender representation.

Moreover, in a national context marked by persistent inequalities and limited employment opportunities, the predominance of women in this sector reflects a proactive effort to advance the principles of inclusivity and accessibility. The data indicate that the sector is not only aware of its role in promoting gender equity but is also actively contributing to the implementation of relevant SDGs through its employment practices.

This gender distribution also aligns with the human resource dimension of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1), which emphasises the importance of demographic factors, such as gender and age, in shaping institutional capacity and developmental outcomes. The presence of a significant proportion of female employees enhances the sector’s potential to foster inclusive growth and equitable service delivery in the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR).

The results in

Figure 2 show that this research is dominated by female respondents (58.1%) compared to male respondents (41.9%).

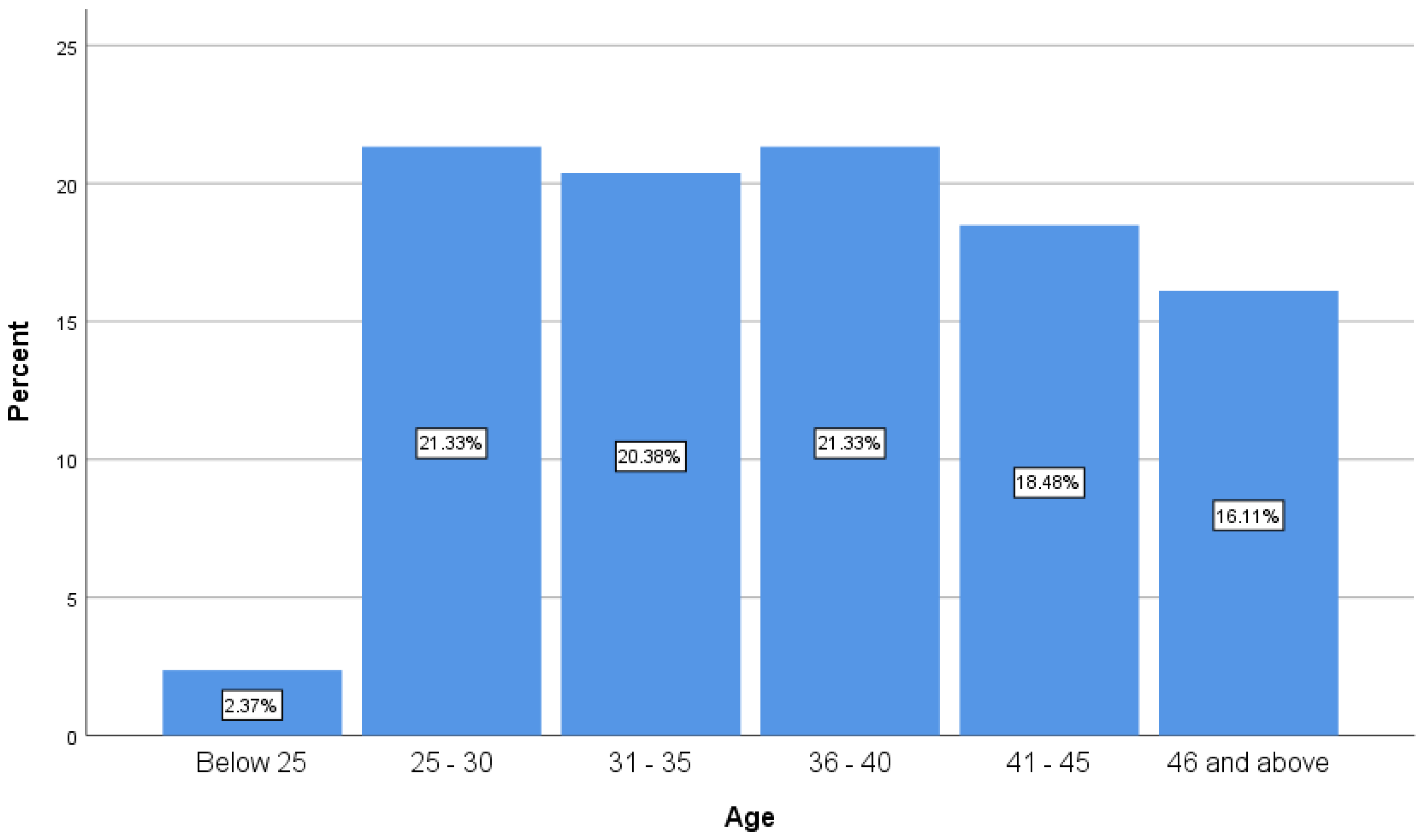

4.2. Age and Accessibility

Age is a critical factor in assessing accessibility to economic opportunities, particularly in a country like South Africa, which faces persistently high levels of youth unemployment. Within the context of this study, age serves as a proxy for evaluating the banking sector’s contribution to the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably Goal 1 (No Poverty), Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and Goal 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). These goals are interconnected, as youth unemployment is often linked to social instability, crime, and weakened institutional structures.

The findings, presented in

Figure 3, indicate that the 25–30 and 36–40 age groups were equally represented, each comprising 21.3% of the sample. The 31–35 age group followed closely at 20.4%. This distribution suggests that the workforce in the Free State banking sector is predominantly composed of young and middle-aged employees, with a significant proportion falling within the youth category.

This demographic profile reflects a deliberate effort by the sector to enhance accessibility to employment for younger individuals, thereby supporting the implementation of SDG 8. The presence of youth in formal employment also contributes to SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) as economic inclusion fosters urban stability and resilience.

Furthermore, the emphasis on age within this analysis aligns with the human capital dimension of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1). By integrating younger individuals into the workforce, the banking sector strengthens its institutional capacity and promotes inclusive growth in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven transformation.

4.3. Education as a Link Between SDGs

Education serves as a foundational element in the pursuit of multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including Goal 1 (No Poverty), Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), Goal 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), and Goal 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). It enhances individual capabilities, institutional effectiveness, and societal resilience, making it a critical factor in assessing inclusivity and accessibility within the banking sector. The findings, as illustrated in

Figure 4, reveal that most respondents (56.4%) possess tertiary qualifications, while 41.7% have attained matric-level education. A small minority reported educational attainment below the matric level. These results indicate that the Free State banking sector has strategically invested in an educated workforce, particularly among the youth, thereby positioning itself as a key enabler of sustainable development.

This educational profile reflects the sector’s capacity to implement and support the SDGs mentioned above. By employing individuals with higher education credentials, the sector enhances its ability to deliver quality services, foster innovation, and maintain institutional integrity—especially in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and the increasing integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in financial services. Moreover, the emphasis on education aligns with the human capital component of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1), which underscores the role of knowledge and skills in enabling individuals and institutions to pursue sustainable and inclusive development pathways.

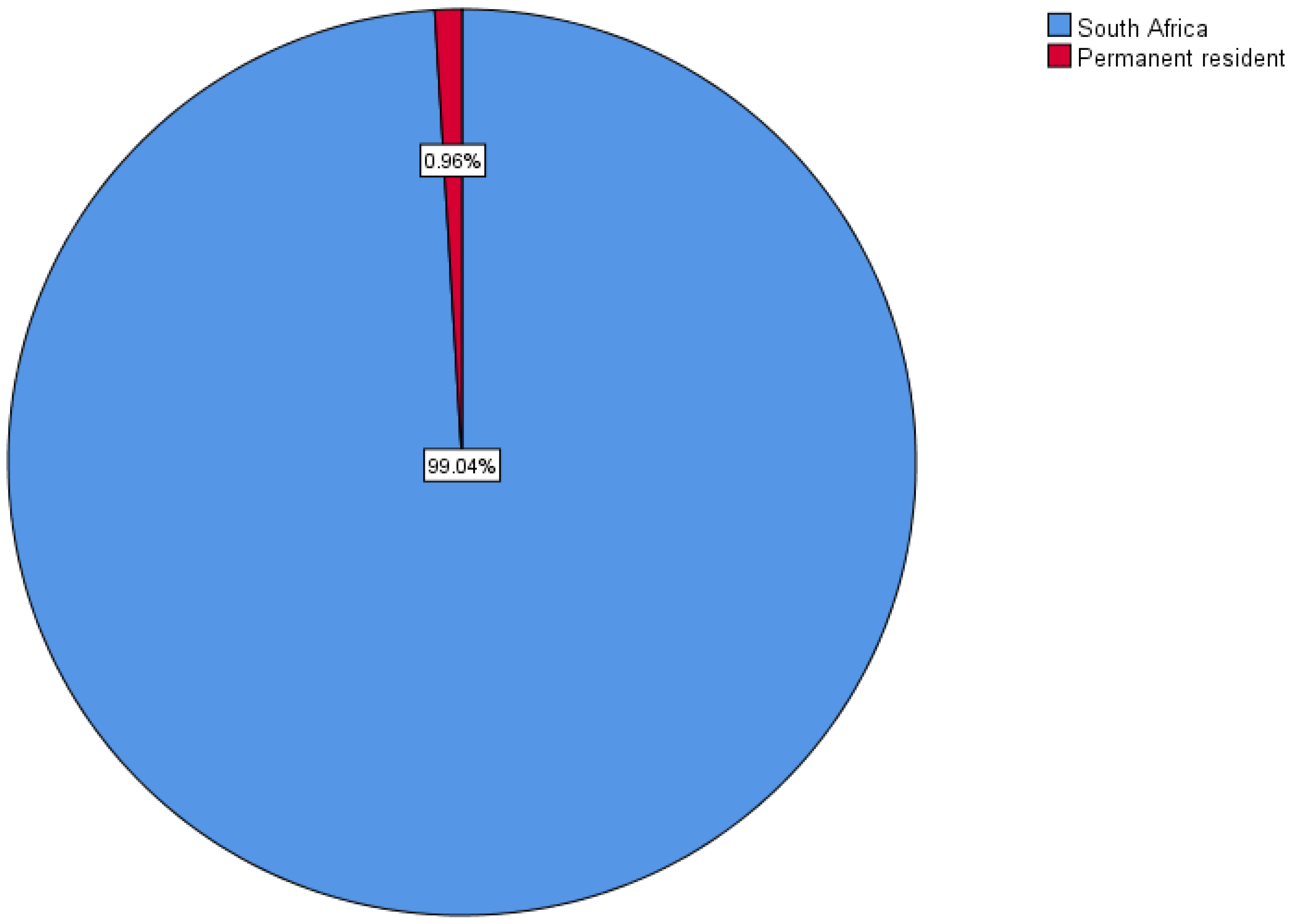

4.4. Nationality as an Indicator of Progress in NDP and SDGs

Nationality is a significant variable in assessing the extent to which South Africa is advancing its national development priorities in alignment with global frameworks such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 1 (No Poverty), Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and Goal 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). Understanding the national composition of the workforce provides insight into the localisation of development efforts and the inclusivity of employment practices.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, most respondents (99%) identified as South African nationals, with a marginal proportion (0.96%) being permanent residents. These findings suggest that the Free State banking sector is predominantly staffed by individuals of South African descent, indicating a strong national orientation in employment practices.

This demographic profile reinforces the sector’s role in contributing to domestic development objectives, particularly in addressing poverty and unemployment among South African citizens. It also reflects the sector’s potential to foster national partnerships and institutional stability, as envisioned in SDG 17. By prioritising local human capital, the banking sector demonstrates its commitment to inclusive growth and sustainable livelihoods within the national context.

4.5. Training of Key Stakeholders on the Use of Fintech and Implementation of SDGs

In alignment with Institutional Theory, particularly its cultural–cognitive dimension, this section evaluates the values, beliefs, and assumptions held by key stakeholders regarding their training in fintech and the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The analysis focuses on perceptions of training adequacy, organisational support, and individual readiness, which collectively influence institutional capacity for transformation.

The findings presented in

Table 3 indicate that a substantial majority of respondents (75.6%) believed they were adequately trained to perform their roles involving fintech and SDG-related responsibilities. Furthermore, 80.9% of participants reported feeling valued and prioritised for fintech training, suggesting that the sector actively supports capacity-building initiatives aligned with SDG implementation.

Additionally, 79.4% of respondents assumed that training opportunities were equitably distributed across their organisations, reinforcing the perception of inclusive learning environments. These results reflect a positive institutional culture that promotes accessibility to knowledge and skills necessary for sustainable development.

This study also examined three key constructs derived from the cultural–cognitive dimension:

System transformation drivers: represented by the statement “I always embrace the training/learning I am given for my career growth”, with 81.9% agreement, indicating strong individual motivation and openness to learning.

System transformation sustainers: captured by the response to “What I have been learning is relevant to my job”, with 85.1% agreement, suggesting that training content is perceived as practical and applicable.

Behavioural reasoning: reflected in the statement “I take learning/training opportunities every time”, with 88.5% agreement, highlighting a proactive attitude toward continuous professional development.

These findings collectively suggest that the Free State banking sector possesses the institutional and human resource capacity to advance fintech integration and SDG implementation. The positive perceptions of training adequacy and relevance underscore the sector’s readiness to adapt to the demands of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven transformation.

The next section discusses the results and findings in this section.

5. Discussion of Results and Findings

This section discusses the findings in relation to this study’s aim: to assess the implementation and impact of inclusivity and accessibility in the South African banking sector, with a specific focus on the Free State province. The discussion is guided by two core objectives: 1, to explore the alignment of fintech banking practices with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 16, and 17; 2, to identify barriers to inclusivity and accessibility in the banking sector, particularly for women and youth.

The analysis is framed by the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1) and Institutional Theory, which together offer a multidimensional lens for understanding how human and social resources influence institutional capacity and developmental outcomes in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

5.1. Gender and Inclusiveness

Despite global and national commitments to gender equality, progress remains slow.

Sil and Lenka (

2024) project that gender parity in leadership within South Africa’s private sector may take up to 140 years to achieve.

Matotoka and Odeku (

2021);

Oosthuizen et al. (

2019) further highlight the systemic under-representation of women in managerial roles, attributing this to race-based recruitment and limited advancement opportunities for qualified women. However, the findings of this study present a positive deviation from these trends. In the Free State banking sector, 58.1% of respondents were female, suggesting a workforce that is not only inclusive but also actively contributing to the realisation of SDG 5 (Gender Equality). This demographic composition also supports the implementation of SDGs 1, 8, 10, 11, and 16, as gender equity is foundational to poverty reduction, economic growth, and institutional stability.

Recent national data reinforce the relevance of these findings.

Statistics South Africa (

2024b) reports that the unemployment rate for women remains disproportionately high at 33.9%, with Black African women experiencing the highest rate, at 38.0%. This underscores the significance of female representation in formal employment sectors such as banking, where operational roles offer pathways to economic empowerment and career progression.

The presence of women in operational roles aligns with the human resource dimension of the SLF, indicating that gender representation enhances institutional capacity for inclusive service delivery. Moreover, it reflects a sectoral commitment to the principles of the

South Africa Government (

1998) and the National Development Plan (NDP), reinforcing the role of policy in shaping equitable employment practices.

5.2. Fintech and Accessibility

The integration of financial technology (fintech) within the banking sector offers transformative potential for advancing inclusivity. Fintech solutions can reduce traditional barriers to financial access, particularly for women and youth, by offering tailored services and expanding reach through digital platforms (

Li & Yan, 2025;

Danladi et al., 2023;

Arner et al., 2016;

Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018). These innovations support the implementation of SDGs 1, 8, 10, 11, and 16, by promoting financial inclusion, urban accessibility, and institutional transparency.

However, challenges persist. The

UN Women and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (

2023) Gender Snapshot warns that without targeted interventions, over 340 million women and girls will remain in extreme poverty by 2030, and gender parity in leadership may not be achieved until 2050. These projections underscore the need for gender-responsive fintech strategies that embed inclusivity into both design and deployment. This study’s findings suggest that the Free State banking sector is making meaningful progress in this regard. The respondents reported high levels of training and perceived support for fintech adoption, indicating institutional readiness to leverage digital tools for SDG implementation. This aligns with the cultural–cognitive dimension of Institutional Theory, which emphasises the role of shared values and beliefs in shaping organisational behaviour.

5.3. Age and Accessibility in the Context of SDGs

The intersection of age and access to employment is a critical factor in the realisation of several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). In the South African context, where youth unemployment remains alarmingly high, age serves as a meaningful proxy for evaluating institutional inclusivity and economic accessibility. Recent national data reinforce these concerns. According to

Statistics South Africa (

2024a), youth aged 15–34 continue to experience the highest unemployment rates, with limited absorption into formal sectors such as banking.

The extant literature underscores the urgency of addressing youth exclusion from formal labour markets.

van Niekerk et al. (

2024) and

Sumberg et al. (

2021) highlight the link between youth unemployment and the “troublesome trio” of conflict, crime, and institutional fragility, particularly in transitional economies.

Betcherman and Khan (

2018) argue that the marginalisation of youth not only perpetuates poverty but also erodes social cohesion and trust in institutions, thereby impeding progress toward SDG 16.

Hungwe and Mukonza (

2025),

Modise (

2025) and

Farisani (

2022) add that structural barriers, such as limited access to digital infrastructure and financial services, disproportionately affect younger populations, especially in rural and underserved areas.

In this context, fintech innovation emerges as a promising tool to enhance accessibility for youth. When designed with age-sensitive considerations, fintech can offer mobile banking, microloans, and digital literacy programs that empower young people economically and socially. These interventions directly support the achievement of SDGs 1, 8, and 16 by promoting financial inclusion, reducing poverty, and strengthening institutional resilience.

The findings of this study, as presented in

Figure 3, reveal that the 25–30 and 36–40 age groups were equally represented, each comprising 21.3% of the sample, followed closely by the 31–35 age group at 20.4%. This distribution indicates that the Free State banking sector is largely composed of young and middle-aged employees, with a significant proportion falling within the youth category. This demographic profile reflects a deliberate institutional effort to enhance employment accessibility for younger individuals, thereby contributing to the implementation of SDG 8. Moreover, the inclusion of youth in formal employment supports SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by fostering urban stability and resilience through economic participation.

The emphasis on age also aligns with the human capital dimension of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1), which recognises age as a determinant of livelihood strategies and institutional capacity. By integrating younger individuals into the workforce, the banking sector strengthens its ability to adapt to the demands of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven transformation while promoting inclusive and sustainable growth.

5.4. Education as a Link Between SDGs, Inclusivity, and Accessibility

Education is widely recognised as a cornerstone of sustainable development and a critical enabler of multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While SDG 4 (Quality Education) is a standalone goal, it also catalyses achieving broader objectives such as SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). Scholars such as

Sezgin et al. (

2023) and

Carvalho et al. (

2024) affirm that education influences a wide spectrum of societal domains, including health, cultural preservation, environmental sustainability, and institutional resilience.

The integration of financial technology (fintech) into educational and economic systems has further expanded the role of education in advancing the SDGs.

Noreen (

2024),

Schleicher (

2024) and

Zolfaghari (

2015) highlight the synergistic relationship between fintech and education, noting that digital financial tools—such as mobile payments, micro-scholarships, and e-learning platforms—can enhance access to education and empower stakeholders to implement SDG-aligned initiatives. However, as

Matsieli and Mutula (

2024) caution, the digital transformation of education, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has also exposed deep inequalities in infrastructure, digital literacy, and institutional readiness, particularly among disadvantaged populations.

In this context, the Free State banking sector demonstrates a strategic investment in human capital, particularly among youth. The findings, illustrated in

Figure 4, show that 56.4% of respondents possess tertiary qualifications, while 41.7% have attained matric-level education. A small minority reported educational attainment below the matric level. This educational profile reflects the sector’s capacity to support and implement SDGs through a skilled and knowledgeable workforce. National data corroborate these findings. According to

Statistics South Africa (

2022), there has been a steady increase in tertiary education attainment, particularly among younger populations.

By employing individuals with higher education credentials, the banking sector enhances its ability to deliver quality services, foster innovation, and maintain institutional integrity—especially in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and the increasing integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in financial services. This aligns with the human capital dimension of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1), which emphasises the role of education in building resilient and adaptive communities. It also resonates with Institutional Theory, which underscores how formal and informal structures shape access to education and financial services, thereby influencing the inclusivity of development outcomes.

Moreover, the sector’s emphasis on education supports this study’s second objective: identifying barriers to inclusivity and accessibility for women and youth. By prioritising educational attainment in its workforce, the Free State banking sector positions itself as a key enabler of inclusive economic growth and institutional development, contributing meaningfully to the realisation of SDGs 1, 4, 8, 16, and 17.

5.5. Nationality and Workforce Composition

Understanding the national composition of the workforce is essential for evaluating South Africa’s progress toward its national development priorities, particularly as they align with global frameworks such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this context, SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) are especially relevant, as they emphasise inclusive economic participation, employment equity, and collaborative development.

The findings, presented in

Figure 5, reveal that 99% of respondents identified as South African nationals, with only 0.96% being permanent residents. Recent census data corroborate this trend.

Statistics South Africa (

2022) reports that the formal employment sector remains predominantly composed of South African nationals, with foreign nationals and permanent residents comprising a small fraction of the workforce. This reflects both regulatory frameworks and employment equity policies that prioritise local talent in strategic sectors such as banking. This overwhelming representation of South African citizens suggests that the Free State banking sector is strongly oriented toward local employment practices, thereby contributing directly to domestic development objectives. Such localisation of human capital supports the goals of the National Development Plan (NDP), which prioritises job creation, poverty alleviation, and inclusive economic growth. From a developmental perspective, employing local citizens enhances Local Economic Development (LED) by ensuring that income, assets, and financial resources remain within the national economy. This contributes to broader economic stability and growth, reinforcing the sector’s role in advancing SDGs and national policy targets.

The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1) provides further insight into this dynamic by emphasising the importance of human, financial, and physical resources in achieving sustainable development (

Farisani & Mashau, 2025). The predominance of South African nationals in the banking workforce reflects a strategic investment in local human capital, which is essential for building resilient institutions and fostering inclusive growth.

Moreover, this demographic profile aligns with this study’s first objective: exploring the alignment of fintech banking practices with SDGs. By prioritising local talent in the implementation of fintech solutions, the sector enhances its capacity to deliver accessible and culturally relevant financial services. It also supports the second objective by demonstrating a commitment to inclusivity—ensuring that employment opportunities are accessible to South African women and youth, who are often under-represented in other sectors. Thus, the nationality composition of the Free State banking sector illustrates a strong alignment with both national and global development agendas. It reflects a deliberate effort to foster inclusive economic participation and institutional stability, thereby contributing meaningfully to the realisation of SDGs 1, 8, and 17.

5.6. Training of Key Stakeholders on the Use of Fintech and Implementation of SDGs

In alignment with Institutional Theory, particularly its cultural–cognitive dimension (

Scott, 2013;

Palthe, 2014), this section evaluates the values, beliefs, and assumptions held by key stakeholders regarding their training in financial technology (fintech) and the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Institutional Theory posits that organisational behaviour is shaped not only by formal structures but also by shared norms and cognitive frameworks, which influence how individuals perceive and respond to institutional change.

The findings presented in

Table 3 reveal a strong institutional commitment to capacity-building. A substantial majority of respondents (75.6%) reported feeling adequately trained to perform their roles involving fintech and SDG-related responsibilities. Furthermore, 80.9% indicated that they felt valued and prioritised for fintech training, suggesting that the sector actively supports inclusive learning environments. Additionally, 79.4% of respondents believed that training opportunities were equitably distributed across their organisations, reinforcing perceptions of fairness and accessibility in professional development.

To further assess institutional readiness, this study examined three constructs derived from the cultural–cognitive dimension of Institutional Theory:

System transformation drivers, represented by the statement “I always embrace the training/learning I am given for my career growth”, with 81.9% agreement. This reflects strong individual motivation and openness to learning, which are essential for institutional adaptability.

System transformation sustainers, captured by the response “What I have been learning is relevant to my job”, with 85.1% agreement. This suggests that training content is perceived as practical and aligned with professional responsibilities.

Behavioural reasoning, reflected in the statement “I take learning/training opportunities every time”, with 88.5% agreement. This indicates a proactive attitude toward continuous professional development and institutional engagement.

These findings collectively suggest that the Free State banking sector possesses both the human resource capacity and the institutional culture necessary to advance fintech integration and SDG implementation. The positive perceptions of training adequacy, relevance, and inclusivity underscore the sector’s readiness to adapt to the demands of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven transformation.

Moreover, the alignment between stakeholder perceptions and institutional support mechanisms reflects a conducive environment for achieving this study’s objectives: exploring the alignment of fintech practices with SDGs and identifying barriers to inclusivity and accessibility for women and youth. The evidence suggests that staff members are not only well equipped but also willing partners in advancing the goals of the National Development Plan (NDP) and the SDGs, positioning the sector as a model for inclusive and sustainable development.

5.7. Policy and Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer several important implications for policy and practice within the South African banking sector, particularly in relation to the National Development Plan (NDP) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The evidence suggests that the Free State banking sector is making meaningful progress in promoting inclusivity, accessibility, and digital transformation through fintech adoption. However, to sustain and scale these efforts, targeted policy interventions are necessary.

Policy implications: strengthening gender-inclusive employment policies, strengthening gender-inclusive employment policies, and youth employment and skills’ development.

The predominance of female employees in the Free State banking sector demonstrates progress toward SDG 5 (Gender Equality). However, broader sectoral policies must address persistent under-representation of women in leadership roles. This calls for enhanced implementation of the Employment Equity Act and gender-sensitive recruitment and promotion strategies.

The sector’s youthful workforce aligns with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), yet national policies must further support youth employment through targeted digital skills training, internship programs, and fintech literacy initiatives, especially in underserved regions.

The high level of educational attainment among banking employees supports the implementation of SDGs 4, 8, and 16. Policymakers should incentivise continued investment in lifelong learning, professional development, and AI-related training to ensure workforce adaptability in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR).

The near-exclusive employment of South African nationals reflects alignment with SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) and the NDP’s emphasis on local economic development. Policies should continue to prioritise local hiring while fostering partnerships with educational institutions and fintech innovators.

Positive stakeholder perceptions of training adequacy and relevance indicate strong institutional readiness. This supports the need for regulatory frameworks that promote inclusive fintech adoption, data protection, and digital financial literacy.

5.8. Recommendations

The Free State Banking sector, provincial government and relevant Non-Government Organisations should establish a standardised, inclusive training framework for fintech competencies across the banking sector, with modules tailored to different demographic groups, including women and youth.

Local municipalities should invest in digital infrastructure in rural and underserved areas to ensure equitable access to fintech services and digital education platforms.

The national government, in collaboration with provincial governments and relevant stakeholders, should implement mentorship and leadership development programs specifically targeting women and young professionals to address gaps in representation at senior levels.

Encourage collaboration between government, financial institutions, academia, and civil society to co-create solutions that align fintech innovation with SDG implementation.

All above-mentioned stakeholders should introduce sector-wide monitoring tools to track progress on inclusivity and accessibility indicators, ensuring accountability and continuous improvement.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study set out to assess the implementation and impact of inclusivity and accessibility in the South African banking sector, with a particular focus on the Free State province. Guided by two core objectives—(1) to explore the alignment of fintech banking practices with selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and (2) to identify barriers to inclusivity and accessibility for women and youth—this research employed a quantitative approach grounded in the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (see

Figure 1) and Institutional Theory.

The findings reveal that the Free State banking sector demonstrates meaningful progress toward several SDGs, notably SDGs 1, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 16, and 17. The sector is characterised by a female-majority workforce, a youthful and educated employee base, and a strong national orientation in employment practices. These attributes reflect a deliberate institutional effort to foster inclusive growth, reduce inequalities, and promote sustainable livelihoods.

Moreover, this study highlights the sector’s readiness to embrace fintech innovation, with stakeholders reporting high levels of training adequacy, relevance, and accessibility. These perceptions suggest that the sector possesses both the human resource capacity and the institutional culture necessary to adapt to the demands of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven transformation.

Despite these positive developments, this study also underscores the need for continued policy support to address persistent structural barriers—particularly those affecting women and youth in leadership and digital access. The integration of inclusive fintech strategies, equitable training frameworks, and targeted development programs will be essential to sustaining progress and achieving the broader goals of the National Development Plan (NDP) and the SDGs.

In conclusion, the Free State banking sector stands as a promising model of inclusive and accessible development within South Africa. Its practices offer valuable insights for other sectors seeking to align institutional transformation with global sustainability agendas.

While this study provides valuable insights into the alignment of fintech banking practices with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the barriers to inclusivity and accessibility for women and youth in the Free State banking sector, several avenues for future research remain open, such as Comparative Sectoral Analysis, Impact of AI and 4IR on Workforce Transformation and Cross-Provincial or Regional Studies.

Future studies could expand the scope beyond the banking sector to include other industries such as insurance, telecommunications, or retail finance. A comparative analysis would help determine whether the trends observed in the Free State banking sector are unique or reflective of broader national patterns.

As the banking sector continues to evolve under the influence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), future studies should examine how these technologies are reshaping job roles, training needs, and inclusivity dynamics.

Expanding the geographical scope to include other provinces or regions within South Africa could help identify regional disparities and best practices in promoting inclusive and accessible banking services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: J.S.T., P.K.H. and T.R.F.; methodology, J.S.T., P.K.H. and T.R.F.; software, J.S.T.; validation, J.S.T., P.K.H. and T.R.F.; formal analysis, J.S.T., P.K.H. and T.R.F.; investigation, J.S.T.; resources, P.K.H.; data curation, J.S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.T., P.K.H. and T.R.F.; writing—review and editing, T.R.F.; visualization, T.R.F.; supervision, P.K.H.; project administration, P.K.H.; funding acquisition, P.K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted following CUT guidelines and ethical clearance (reference no: FMSEC05/21) was obtained (Date: 7 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arner, D. W., Barberis, J., & Buckley, R. P. (2016). The evolution of fintech: A new post-crisis paradigm? Georgetown Journal of International Law, 47(4), 1271–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atadoga, J. O., Nembe, J. K., Mhlongo, N. Z., Ajayi-Nifise, A. O., Olubusola, O., Daraojimba, A. I., & Oguejiofor, B. B. (2024). Cross-border tax challenges and solutions in global finance. Finance & Accounting Research Journal, 6(2), 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betcherman, G., & Khan, T. (2018). Jobs for Africa’s expanding youth cohort: A stocktaking of employment prospects and policy interventions. IZA Journal of Development and Migration, 8(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M. (2021). Hybrid organizations: A micro-level strategy for SDGs implementation: A positional paper. Sustainability, 13(16), 9415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, D. G., & Wright, T. A. (2014). Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L., Almeida, D., Loures, A., Ferreira, P., & Rebola, F. (2024). Quality education for all: A fuzzy set analysis of sustainable development goal compliance. Sustainability, 16(12), 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Danladi, S., Prasad, M. S. V., Modibbo, U. M., Ahmadi, S. A., & Ghasemi, P. (2023). Attaining sustainable development goals through financial inclusion: Exploring collaborative approaches to Fintech adoption in developing economies. Sustainability, 15(17), 13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Farisani, T. R. (2022). Assessing the impact of policies in sustaining rural small, medium and micro enterprises during COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 14(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farisani, T. R., & Mashau, P. (2025). South African rural municipalities’ innovation lessons in anti-poverty policy formulation, assessment and implementation. E-Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, 6(7), 1173–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundira, M., Edoun, E. I., & Pradhan, A. (2024). Evaluating end-users’ digital competencies and ethical perceptions of AI systems in the context of sustainable digital banking. Sustainable Development, 32(5), 4866–4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haida, M. (2009). Sustainable livelihood approaches. The framework, lessons learnt from practice and policy recommendations. Drylands Development Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Hungwe, N. A., & Mukonza, P. R. M. (2025). Assessing South Africa’s progress on sustainable development goal 8: Economic growth and inequality in rural communities post-apartheid. African Journal of Development Studies (formerly AFFRIKA Journal of Politics, Economics and Society), 15(2), 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jejeniwa, T. O., Mhlongo, N. Z., & Jejeniwa, T. O. (2024). AI solutions for developmental economics: Opportunities and challenges in financial inclusion and poverty alleviation. International Journal of Advanced Economics, 6(4), 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Pitre, A., Molina-Bolivar, J. A., & Gamez Pitre, J. (2022). Digital education and equity in Latin America: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Development, 92, 102627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomo, S. M., Farisani, T. R., & Mashau, P. (2023). The financial legislative role and capacity of municipal councillors at Ulundi Municipality. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 11(1), 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomo, S. M., Farisani, T. R., & Mashau, P. (2025). The gap between public finance legislation and local economic development in South Africa. Journal of Local Government Research and Innovation, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor, K., Bansal, S. K., & Kumar, R. (2025). The role of fintech in promoting financial inclusion to achieve sustainable development. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 16, 5664–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmair, M., & Gamper, S. (2002). The sustainable livelihood approach. Development Study Groups, University of Zurich (IP6). [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. (2014). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., & Yan, L. (2025). Bridging the financial access gap: The empowering potential of fintech. International Interdisciplinary Business Economics Advancement Journal, 6(07), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Matotoka, M. D., & Odeku, K. O. (2021). Untangling discrimination in the private sector workplace in South Africa: Paving the way for Black African women progression to managerial positions. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 21(1), 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsieli, M., & Mutula, S. (2024). COVID-19 and digital transformation in higher education institutions: Towards inclusive and equitable access to quality education. Education Sciences, 14(8), 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbodj, A., & Laye, S. (2025). Reducing poverty through financial growth: The impact of financial inclusion and development in emerging economies. Journal of Business and Economic Options, 8(1), 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Modise, J. M. (2025). The South African we want: A vision shaped by current challenges. MRS Journal of Arts, Humanities and Literature, 2(7), 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Noreen, U. (2024). Mapping of fintech ecosystem to sustainable development goals (SDGs): Saudi Arabia’s landscape. Sustainability, 16(21), 9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosthuizen, R., Tonelli, L., & Mayer, C. H. (2019). Subjective experiences of employment equity in South African organisations. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Palthe, J. (2014). Regulative, normative, and cognitive elements of organizations: Implications for managing change. Management and Organizational Studies, 1(2), 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramabodu, B., Mashau, P., & Farisani, T. R. (2024). Assessing innovation and entrepreneurship transformations in two South African universities amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(14), 9139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K. J. (2025). Accessibility and affordability of technologies. In Innovations in neurocognitive rehabilitation: Harnessing technology for effective therapy (pp. 285–304). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher, A. (2024). Toward the digital transformation in education. Frontiers of Digital Education, 1(1), 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, identities. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, F. H., Tekin Turhan, G., Sart, G., & Danilina, M. (2023). Impact of financial development and remittances on educational attainment within the context of sustainable development: A panel evidence from emerging markets. Sustainability, 15, 12322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihadeh, F. H. (2022). The links between banking theories and financial inclusion: A theoretical framework. In Sustainable finance, digitalization and the role of technology (pp. 251–257). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Shylaja, H. N. (2020). Financial inclusion with reference to access to banking services: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 9(1), 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sil, N., & Lenka, U. (2024). Strategies for gender inclusion in organizations. Strategic HR Review, 24(3), 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E., & Vanclay, F. (2017). The social framework for projects: A conceptual but practical model to assist in assessing, planning and managing the social impacts of projects. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 35(1), 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Africa Government. (1998). Employment equity act 55 of 1998. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/employment-equity-act (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. (2022). Census dissemination. Stats SA. Available online: https://census.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. (2024a). ISIbalo data portal. Stats SA. Available online: https://isibaloweb.statssa.gov.za/idatweb.php (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. (2024b). Youth in South Africa 2024 (Report No. 03-00-21). Stats SA. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/03-00-21/03-00-212024.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Sumberg, J., Fox, L., Flynn, J., Mader, P., & Oosterom, M. (2021). Africa’s “youth employment” crisis is actually a “missing jobs” crisis. Development Policy Review, 39(4), 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. (2016). Sampling Methods in Research Methodology; How to Choose a Sampling Technique for Research. International Journal of Academic Research in Management (IJARM), 5, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women & United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2023). Progress on the sustainable development goals: The gender snapshot 2023. UN Women. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/09/progress-on-the-sustainable-development-goals-the-gender-snapshot-2023 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- van Niekerk, L., Claassens, N., Fish, J., Foiret, C., Franckeiss, J., & Thesnaar, L. (2024). Support factors contributing to successful start-up businesses by young entrepreneurs in South Africa. Work, 79(1), 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolfaghari, A. (2015). The necessity and importance of education for social and cultural development of societies in developing countries. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Fen Edebiyat Fakültesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi, 36, 3380–3386. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).