The Role of Environmental Accounting in Mitigating Climate Change: ESG Disclosures and Effective Reporting—A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- In what ways do environmental accounting practices support organizations’ climate change mitigation efforts?

- (2)

- How do ESG disclosure frameworks and practices enhance transparency and accountability regarding climate change, and what evidence exists of their impact on corporate behavior or performance?

- (3)

- What are the global approaches to ESG climate disclosures, and what challenges affect effective reporting?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Review Approach

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

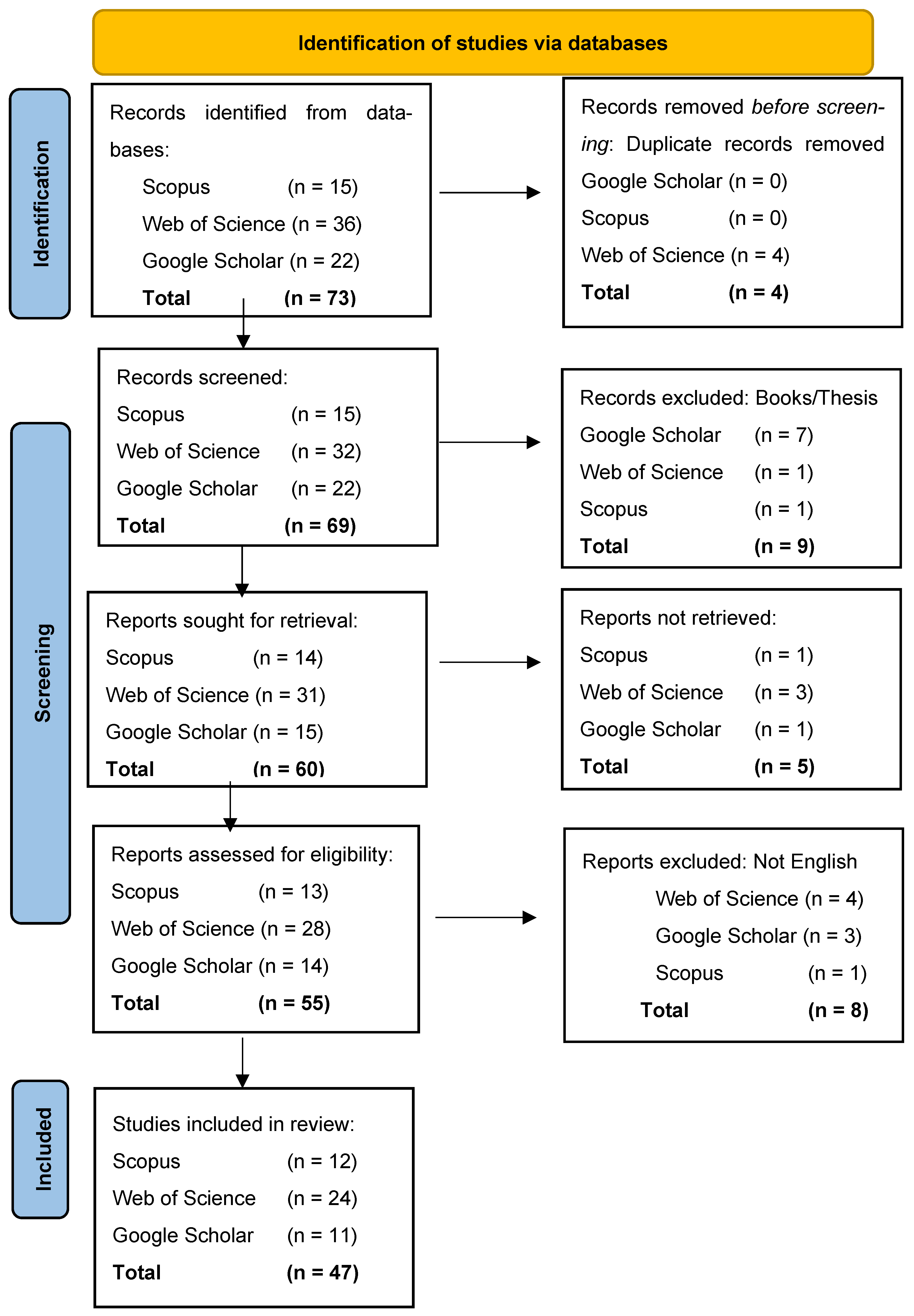

Selection Process (PRISMA Flow)

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Profile of Included Studies

3.2. Environmental Accounting as a Tool for Climate Change Mitigation

3.3. ESG Disclosures and Effective Climate Reporting

3.4. Global Approaches and Regulatory Initiatives

3.5. Challenges and Ongoing Issues in Environmental Accounting and ESG Reporting

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdalla, A. A. A., Salleh, Z., Hashim, H. A., Zakaria, W. Z. W., & Rahman, M. S. A. (2024). The effect of corporate governance best practices on the quality of carbon disclosures among Malaysian public listed companies. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, 19(2), 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H. I., & Mansour, M. S. M. (2018). Solid waste issue: Sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum, 27(4), 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, E. M., Khallaf, A., Abdallah, A. A. N., Zoubi, T., & Alnesafi, A. (2024). Blockchain-driven carbon accountability in supply chains. Sustainability, 16(24), 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, E. (2023). Accelerating sustainability through better reporting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 14(4), 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmana, R. K., You, H. W., & Razali, M. W. M. (2016). Climate change mitigation and the cost of equity: Evidence from Malaysia. International Journal of Green Economics, 10(3–4), 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Zhou, X., Luo, H., & Wang, H. (2025). Climate change exposure and corporate employment: Evidence from China. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P., Betrò, S., & Janiri, L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, S., Principale, S., & Venturelli, A. (2022). Sustainable governance and climate-change disclosure in European banking: The role of the corporate social responsibility committee. Corporate Governance, 22(6), 1345–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, V., D’Ecclesia, R., & Levantesi, S. (2021). Fundamental ratios as predictors of ESG scores: A machine learning approach. Decisions in Economics and Finance, 44(2), 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva Lokuwaduge, C. S., Smark, C., & Mir, M. (2022). The surge of environmental, social, and governance reporting and sustainable development goals: Some normative thoughts. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 16(2), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, A., Sanderford, A., & Wang, C. (2024). Sustainability and private equity real estate returns. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 68(2), 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A. I., Pinheiro, P., & Fernandes, S. (2024). Gender diversity and climate disclosure: A TCFD perspective. Environment, Development and Sustainability. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, P. F. A., Harris, P., & Caykoylu, S. (2023). Climate change and corporate governance-did we get it all wrong? Preprints, (1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, P. F. A., Harris, P., & Caykoylu, S. (2024). The impact of corporate characteristics on climate governance disclosure. Sustainability, 16(5), 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, E. (2024). Thirty years of sustainability reporting: Insights, gaps and an agenda for future research through a systematic literature review. Sustainability, 16(23), 10750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elidrisy, A. (2024). Examining the Impact of ESG on organizational performance: The literature review on investment sectors of the middle East and North Africa (MENA). American Journal of Economics and Business Innovation, 3(1), 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, L. T., Atawnah, N., Yeboah, R., & Zhou, Y. (2024). Firm-level climate risk and accounting conservatism: International evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 95(PC), 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferjančič, U., Ichev, R., Lončarski, I., Montariol, S., Pelicon, A., Pollak, S., Sitar Šuštar, K., Toman, A., Valentinčič, A., & Žnidaršič, M. (2024). Textual analysis of corporate sustainability reporting and corporate ESG scores. International Review of Financial Analysis, 96, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabr, D. H., & ElBannan, M. A. (2025). Is it worth it to go green? ESG disclosure, carbon emissions, and firm financial performance in emerging markets. Review of Accounting and Finance, 24(2), 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J., Hauptmann, C., & Serafeim, G. (2021). Material sustainability information and stock price informativeness. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(3), 513–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazami-Ammar, S. (2024). Institutional investors and corporate social responsibility reporting: A systematic literature review in accounting and corporate governance. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 0123456789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V. H. (2022). Modernizing ESG disclosure. University of Illinois Law Review, 2022(1), 277–356. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, H. V. (2024). Environmental, social, and governance disclosure in response to climate policy uncertainty: Evidence from US firms. In Environment, development and sustainability (Vol. 26, Issue 2). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, M. N., Khatib, S. F., & Bazhair, A. H. (2023). Sustainability reporting in Africa: A systematic review and agenda for future research. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(5), 2081–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R., Gupta, S., & Tiwari, A. K. (2024). Decoding the mood of the Twitterverse on ESG investing, opinion mining, and key themes using machine learning. Management Research Review, 47(8), 1221–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., & Tang, Q. (2023). Mandatory carbon reporting, voluntary carbon disclosure, and ESG performance. Pacific Accounting Review, 35(4), 534–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H., Cho, J. H., Kim, B. J., & Lee, W. E. (2024). Machine learning approach for carbon disclosure in the Korean market: The role of environmental performance. Science Progress, 107(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C., Keeley, A. R., Takeda, S., Seki, D., & Managi, S. (2025). Investor’s ESG tendency probed by pre-trained transformers. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32(2), 2051–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Qamruzzaman, M. (2023). Nexus between environmental degradation, clean energy, financial inclusion, and poverty: Evidence with DSUR, CUP-FM, and CUP-BC estimation. Sustainability, 15(19), 14161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaleno, M., Vieira, E., Magueta, D., & Nogueira, M. (2023). Sustainability reporting and climate change energy requirements: The role of companies and their governance—A review. Preprint, 1(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahieux, L., Sapra, H., & Zhang, G. (2025). Measuring greenhouse gas emissions: What are the costs and benefits? Journal of Accounting Research, 63(3), 1063–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszak-Flejszman, A., Łukaszewski, S., & Banach, J. K. (2024). ESG reporting of commercial banks in poland in the aspect of the new requirements of the directive on corporate reporting in the field of sustainable development (CSRD). Sustainability, 16(20), 9041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meqbel, R., Dwekat, A., Zaid, M. A. A., Alta’any, M., & Abukhaled, A. M. (2025). Governance for a greener Europe: Audit committee and carbon emissions. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, G., Patro, A., & Tiwari, A. K. (2024). Does climate governance moderate the relationship between ESG reporting and firm value? Empirical evidence from India. International Review of Economics and Finance, 91, 920–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T., Le, T., Ullah, S., & Trinh, H. H. (2023). Climate risk disclosures and global sustainability initiatives: A conceptual analysis and agenda for future research. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(6), 3705–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noja, G. G., Baditoiu, B. R., Buglea, A., Munteanu, V. P., & Cimpoieru, D. C. G. (2024). The impact of environmental, social, and governance policies on companies’ financial and economic performance: A comprehensive approach and new empirical evidence. E a M: Ekonomie a Management, 27(1), 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D. K., Al-ahdal, W. M., Moussa, F., & Hashim, H. A. (2025). Stock market reaction to mandatory climate change reporting: The case of Bursa Malaysia. Review of Accounting and Finance, 24(2), 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principale, S., & Pizzi, S. (2023). The determinants of TCFD reporting: A focus on the Italian context. Administrative Sciences, 13(2), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W., & Schaltegger, S. (2017). Revisiting carbon disclosure and performance: Legitimacy and management views. The British Accounting Review, 49(4), 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, W., Wu, S. J., & Raghupathi, V. (2023). Understanding corporate sustainability disclosures from the securities exchange commission filings. Sustainability, 15(5), 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, J. S., Feng, M., & DeMello, J. (2022). Corporate sustainability performance and informativeness of earnings. American Journal of Business, 37(3), 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A. (2022). Minimalonomics: A novel economic model to address environmental sustainability and Earth’s carrying capacity. Journal of Cleaner Production, 371, 133663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf-Addin, H. H., & Al-Dhubaibi, A. A. S. (2025). Carbon sustainability reporting based on GHG protocol framework: A Malaysian practice towards net-zero carbon emissions. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, 25, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tettamanzi, P., Gotti Tedeschi, R., & Murgolo, M. (2024). The European Union (EU) green taxonomy: Codifying sustainability to provide certainty to the markets. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(11), 27111–27136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z., Qiu, L., & Wang, L. (2024). Drivers and influencers of blockchain and cloud-based business sustainability accounting in China: Enhancing practices and promoting adoption. PLoS ONE, 19(1), e0295802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toukabri, M. (2025). Chief Sustainability Officer (CSO) power and sustainability-based compensation for climate change disclosure and carbon performance: Is it different for developed and developing nations? Society and Business Review, 20(1), 52–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. (2023). Determinants and financial consequences of environmental performance and reporting: A literature review of European archival research. Journal of Environmental Management, 340, 117916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, L. H., Giese, E. C., Ribeiro-Duthie, A. C., & Lins, F. A. F. (2021). Sustainability and the circular economy: A theoretical approach focused on e-waste urban mining. Resources Policy, 74, 101467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadiati, W., Meiryani, Lindawati, A. S. L., Wahyuningtias, D., Daud, Z. M., & Lusianah. (2024). Exploring carbon disclosure research for future research agenda: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 14(3), 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Studies explicitly addressing environmental or sustainability accounting practices (e.g., carbon accounting, ESG disclosures). | Studies not relevant to the climate context (e.g., environmental accounting without mention of climate change). |

| Link to climate | Studies linking practices to climate change mitigation or adaptation (e.g., discussing impacts on emission reductions). | Papers dealing with ESG or sustainability in a broad sense, without a specific connection to climate change. |

| Evidence | Studies providing analysis or evidence rather than purely opinion. | Non-academic reports and news articles, unless they provide valuable data or context. |

| Geographic diversity | The global literature focusing on varying geographic contexts (single-country or multi-country studies). | None |

| Screening Process | Titles and abstracts were screened to eliminate irrelevant items, followed by full-text review for final inclusion. | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nyakuwanika, M.; Panicker, M. The Role of Environmental Accounting in Mitigating Climate Change: ESG Disclosures and Effective Reporting—A Systematic Literature Review. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090480

Nyakuwanika M, Panicker M. The Role of Environmental Accounting in Mitigating Climate Change: ESG Disclosures and Effective Reporting—A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(9):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090480

Chicago/Turabian StyleNyakuwanika, Moses, and Manoj Panicker. 2025. "The Role of Environmental Accounting in Mitigating Climate Change: ESG Disclosures and Effective Reporting—A Systematic Literature Review" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 9: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090480

APA StyleNyakuwanika, M., & Panicker, M. (2025). The Role of Environmental Accounting in Mitigating Climate Change: ESG Disclosures and Effective Reporting—A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090480