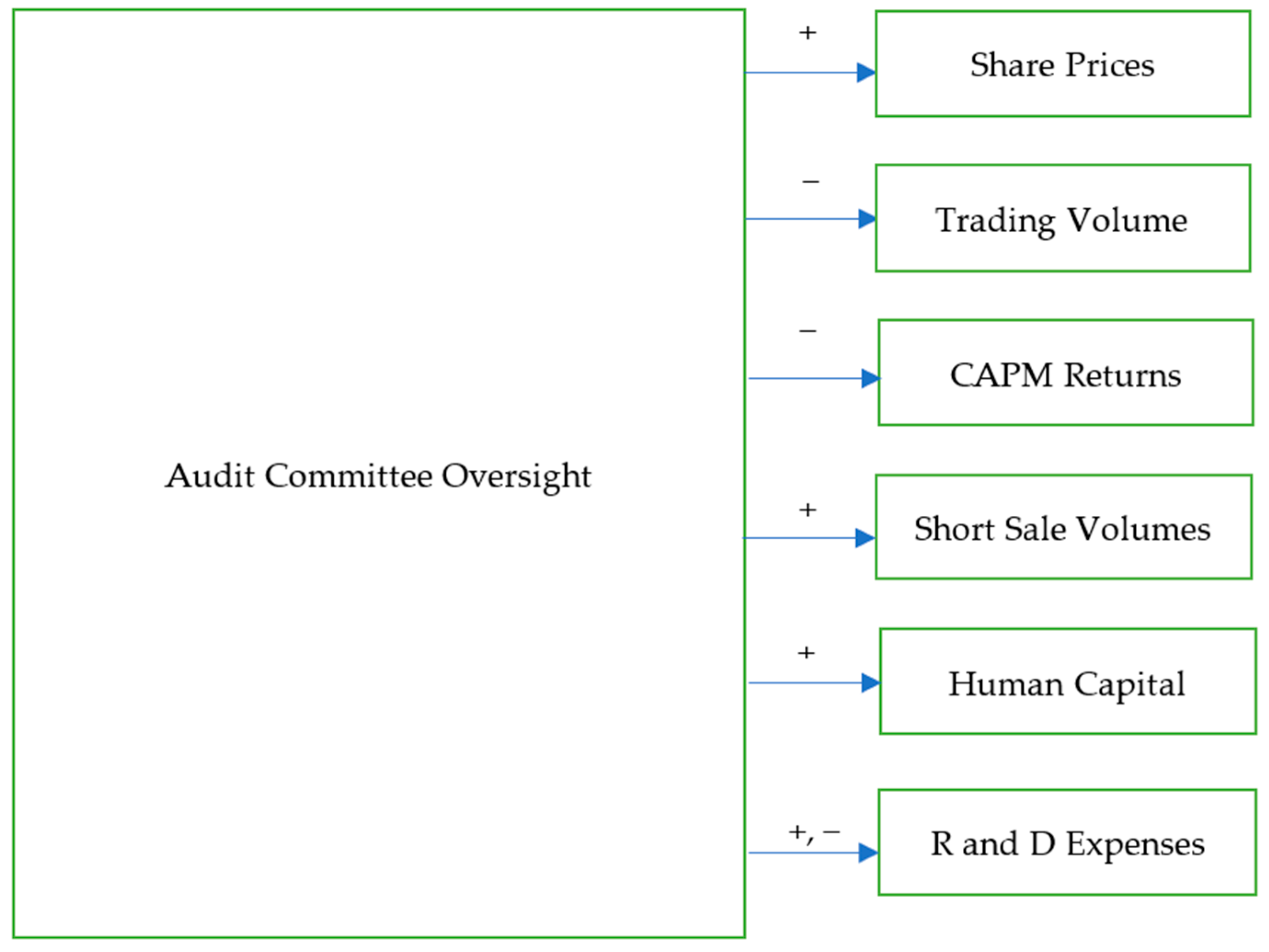

The Impact of Audit Committee Oversight on Investor Rationality, Price Expectations, Human Capital, and Research and Development Expense

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Definition of Audit Committee Oversight

“An effective audit committee has qualified members with the authority and resources to protect shareholder interests by ensuring reliable financial reporting, internal controls, and risk management through its diligent oversight efforts.”

2.2. Audit Committee Oversight: Relationship with Prior Studies

2.3. Audit Committee Oversight and Investor Rationality

2.3.1. Audit Committee Oversight and Security Prices

2.3.2. Audit Committee Oversight and Trading Volume

2.4. Audit Committee Oversight and Price Expectations

2.4.1. Audit Committee Oversight and CAPM Returns

2.4.2. Audit Committee Oversight and Short Sale Volumes

2.5. Audit Committee Oversight and Human Capital

2.6. Audit Committee Oversight and Research and Development Expense

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Results of Hypotheses Testing

4.2. Robustness Check

4.3. Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, R. (2006). An exploration of earnings whispers forecasts as predictors of stock returns. Journal of Economic Studies, 32, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R., El-Chaarani, H., & Deari, F. (2024). Does audit oversight quality reduce bankruptcy risk, systematic risk, and ROA volatility?: The role of institutional ownership. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadasi, A. A. (2024). The power of institutional investors: Empirical evidence on their role in investment in the internal audit function. Managerial Auditing Journal, 39, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, E. S. S. (2019). Audit committee, internal audit function and earnings management: Evidence from Jordan. Meditari Accounting Research, 27, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, A., Elder, R., Beasley, M., III, & Hogan, C. (2010). Auditing and assurance services: An integrated approach. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P., & Cottor, J. (2009). Audit committee and earnings quality. Accounting and Finance, 49, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bens, D., Cheng, W. J., & Huang, S. (2019). The association between the expanded audit report and financial quality. Working Paper. Singapore National University. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, B., & Brough, T. (2012). Concentrated short selling activity: Bear raids or contrarian trading? International Journal of Managerial Finance, 8, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, S., Carcello, J., Hollingsworth, C., & Neal, T. (2009). Are fully independent audit committees really necessary? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 28, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A. (2018). Audit committee characteristics: An empirical investigation of the contribution to intellectual capital efficiency. Measuring Business Excellence, 22, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtbayaz, M. L., Salehi, M., Mirzaei, A., & Nazaridaraji, H. (2020). The impact of corporate governance on intellectual capital’s efficiency in Iran. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 13, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeZoort, T., Hermanson, D. R., Archambeault, D. S., & Reed, S. A. (2002). Audit committee effectiveness: A synthesis of the empirical audit committee literature. Journal of Accounting Literature, 21, 38–75. [Google Scholar]

- Diether, K. B., Malloy, C. J., & Scherbina, A. (2002). Differences of opinion and the cross section of stock returns. Journal of Finance, 57, 2113–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarzoukhy, M., Hussainey, K., & Abdulfattah, T. (2023). The key audit matters and the audit cost: Does governance matter? International Journal of Accounting and Information Management, 31, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A., Serea, A., & Peyaci, S. (2013). The impact of audit committee characteristics on the performance: Evidence from Jordan. International Management Review, 19, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hoi, C.-K., Ashok, R., & Tessoni, D. (2007). Sarbanes-Oxley: Are independent auditors up to the task? Managerial Auditing Journal, 22, 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS). (2025). Available online: https://www.issgovernance.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Jegadeesh, N., & Titman, S. (2001). Profitability of momentum strategies: An evaluation of alternative explanations. Journal of Finance, 56, 699–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, J., & Aggestam, M. (2001). Corporate governance and intellectual capital; some conceptualisations. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 9, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisic, L. L., Neal, T., & Zhang, Y. (2011). Audit committee financial expertise and restatements: The moderating effect of CEO power. School of Management, George Mason University. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, J. M. (2010). Reporting independent directors after Sarbanes-Oxley. Business Law Today, 19, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mavridis, D. (2004). The intellectual capital performance of Japanese banking sector. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. (1977). Risk, uncertainty, & divergence of opinion. Journal of Finance, 32, 1151–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Porumb, V. A., Zengin-Karairaghimoglu, Y., & Lobo, P. H. (2021). Expanded auditors’ report disclosures and loan contracting. Contemporary Accounting Research, 38, 3214–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B., & Tian, G. (2012). The impact of audit committees personal characteristics on earnings management: Evidence from China. Journal of Applied Business Research, 28, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratu, D. M., & Rahjang, D. K. (2024). Anti-corruption policy and earnings management: Do women in monitoring roles matter? Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 9, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, W. (1964). Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. Journal of Finance, 19, 425–442. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., Sidhu, J., Joshi, M., & Karnsal, M. (2016). Measuring intellectual capital performance of Indian banks: A public and private sector performance. Managerial Finance, 42, 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-H., Chung, H., & Liu, C.-L. (2011). Committee independence and financial institution performance during the 2007–2008 credit crunch: Evidence from a multi-country study. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 19, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Predictors | |

| Audit Oversight Measure 1 | Total frequency of the term ‘audit committee’ in annual reports and Form 10Ks |

| Audit Oversight Measure 2 | Frequency of the term ‘audit committee’ in 300-word or longer paragraphs in annual reports and Form 10Ks |

| Audit Oversight Measure 3 | Frequency of the term ‘audit committee’ in 150-word or fewer paragraphs in annual reports and Form 10Ks |

| Criteria | |

| Share Price | Three-period moving average of share prices |

| Trading Volume | Trading volume per year/Total number of shares issued |

| CAPM Return | CAPM return on a security rj = risk-free rate+beta x (market risk premium) |

| Short Sales as a Percentage of Float | Short sales/Float |

| Short Sales as a Percentage of Shares Outstanding | Short sales/Number of shares outstanding |

| Human Capital | Salary expenses |

| Research and Development Expenses/Assets | Research and development expenses |

| Control Variables | |

| Leverage | Debt/Assets |

| Firm Size | Total assets |

| Firm Tangibility | Fixed assets/Total assets |

| COVID Dummy | Dichotomous variable with values of 1 during 2020–2021 and 0 for remaining years from 2010 to 2022. |

| Robustness Check | |

| Governance | Global measure of governance from a proprietary database |

| Panel A: Descriptive Statistics | |||||||||||||

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Maximum | Minimum | Skewness | Kurtosis | |||||||

| Audit Oversight Measure 1 | 1390 | 31.54 | 77,041 | 0.00 | 7.44 | 128.00 | |||||||

| Audit Oversight Measure 2 | 1.97 | 0.03 | 74 | 0.00 | 6.73 | 89.66 | |||||||

| Audit Oversight Measure 3 | 75.88 | 1.90 | 4775 | 0.00 | 7.43 | 126.78 | |||||||

| Share Price Moving Average | $11.24 | $0.32 | $612.04 | $0.00 | 6.93 | 84.34 | |||||||

| Trading Volume | $1.35 million | $0.35 million | $948.96 million | $0.00 | 24.56 | 616.88 | |||||||

| CAPM Return | 12.87% | 0.16% | −39.13% | 58.55% | −0.43 | −0.05 | |||||||

| Short Sales as a Percentage of Float | 3.65% | 0.09% | 32.40% | 0.02% | 8.12 | 101.87 | |||||||

| Short Sales as a Percentage of Sales Outstanding | 3.00% | 0.07% | 19.64% | 0.02% | 10.82 | 162.35 | |||||||

| Human Capital | $124,000 | $1000 | $397,000 | $40,000 | 23.54 | 889.88 | |||||||

| Research and Development Expenditures | $1.76 billion | $13.16 million | $2.25 billion | $0.00 million | 8.78 | 89.66 | |||||||

| Panel B: Correlation Matrix of Predictors and Criteria | |||||||||||||

| Variable | A1 | A2 | A3 | Price | Volume | Short 1 | Short 2 | CAPM | Human | R&D | |||

| A1 | 1 | 0.74 *** | 0.71 *** | 0.31 ** | 0.005 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.39 *** | 0.08 | |||

| A2 | 1 | 0.61 *** | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.47 *** | 0.07 | ||||

| A3 | 1 | 0.31 ** | 0.005 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.37 *** | 0.12 | |||||

| Price | 1 | 0.002 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.33 *** | 0.34 *** | ||||||

| Volume | 1 | 0.008 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.0004 | |||||||

| Short 1 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Short 2 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| CAPM | 1 | 0.49 | 0.09 | ||||||||||

| Human | 1 | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| R&D | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Variable | Moving Average of Share Prices | Moving Average of Share Prices | Moving Average of Share Prices | Trading Volume | Trading Volume | Trading Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.98 *** | 6.22 *** | 5.02 *** | 1.28 | 1.23 | 1.28 |

| Audit Oversight Measure 1 | 0.001 *** | −0.0001 * | ||||

| Audit Oversight Measure 2 | 0.43 *** | −0.06 | ||||

| Audit Overnight Measure 3 | 0.03 *** | −0.002 * | ||||

| Leverage | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Tangibility | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.009 | −0.01 |

| Firm Size | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| COVID Dummy | 1.24 | 1.46 | 1.31 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| N | 7745 | 7631 | 7631 | 7751 | 7631 | 7631 |

| R2 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Variable | CAPM Return | CAPM Return | CAPM Return | Short Sales, % of Float | Short Sales, % of Float | Short Sales, % of Float | Short Sales, % of Shares Issued | Short Sales, % of Shares Issued | Short Sales, % of Shares Issued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.12 | 0.02 | −0.23 | 3.71 *** | 3.81 ** | 3.6 *** | 3.07 ** | 3.14 ** | 3.04 ** |

| Audit 1 | −0.0001 * | 0.00004 * | 0.00002 | ||||||

| Audit 2 | −0.19 *** | −0.02 | −0.02 * | ||||||

| Audit 3 | −0.001 | 0.001 ** | 0.0007 * | ||||||

| Leverage | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.0009 | 0.0009 | 0.0007 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| Tangible | 0.0004 | −0.00001 | 0.0009 | −0.005 | −0.0005 * | −0.004 | −0.003 ** | −0.004 | −0.003 ** |

| Firm Size | −0.0002 | −0.00001 | −0.0006 | 0.002 *** | 0.003 ** | 0.002 | 0.002 ** | 0.002 *** | 0.002 *** |

| COVID Dummy | 11.57 *** | 11.60 *** | 11.57 *** | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| N | 7751 | 7631 | 7631 | 7751 | 7631 | 7631 | 7751 | 7631 | 731 |

| R2 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Variable | Human Capital | Human Capital | Human Capital |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.50 *** | 1.51 *** | 1.50 *** |

| Audit Oversight Measure 1 | 0.00002 *** | ||

| Audit Oversight Measure 2 | 0.009 *** | ||

| Audit Oversight Measure 3 | 0.0003 *** | ||

| Leverage | −0.0001 | −0.0009 | −0.0001 |

| Tangibility | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

| Firm Size | 0.0008 | 0.0008 | 0.0008 |

| COVID Dummy | −0.25 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.25 *** |

| N | 7695 | 7575 | 7575 |

| R2 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Variable | Research and Development Expenses | Research and Development Expenses | Research and Development Expenses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 8.79 *** | 7.74 *** | 8.43 *** |

| Audit Oversight Measure 12 | 0.00 | ||

| Audit Oversight Measure 1 | −0.0003 | ||

| Audit Oversight Measure 22 | −0.003 | ||

| Audit Oversight Measure 2 | 0.04 | ||

| Audit Oversight Measure 32 | 0.000003 ** | ||

| Audit Oversight Measure 3 | −0.011 *** | ||

| Leverage | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| Tangibility | −0.009 * | −0.005 | −0.008 |

| Firm Size | 0.005 * | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| COVID Dummy | −3.42 *** | −3.16 *** | −3.06 *** |

| N | 7724 | 7611 | 7582 |

| R2 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Variable | Moving Average of Share Prices | Trading Volume | CAPM Return | Short Sales, % of Float | Short Sales, % of Shares Issued | Human Capital | Research & DevelopmentExpenses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.49 | 1.28 | −0.27 | 1.58 *** | 1.69 *** | 1.51 *** | −60.00 |

| Governance2 | 5.31 * | ||||||

| Governance | 1.86 *** | −0.08 *** | −0.01 | 0.90 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.01 *** | −16.06 |

| Leverage | 0.01 ** | 0.002 | −0.004 | 0.001 | −0.002 | −0.00007 | −0.48 |

| Tangibility | −0.04 | −0.009 | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.18 * |

| COVID Dummy | 1.52 | 0.31 | 11.58 *** | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.25 *** | 19.39 |

| Firm Size | 0.02 | 0.005 | −0.0006 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.0009 | −0.08 |

| N | 7757 | 7757 | 7757 | 7757 | 7757 | 7701 | 7708 |

| R2 | 0.23 | 0.002 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.64 | 0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abraham, R.; Bhimavarapu, V.M.; El-Chaarani, H. The Impact of Audit Committee Oversight on Investor Rationality, Price Expectations, Human Capital, and Research and Development Expense. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060321

Abraham R, Bhimavarapu VM, El-Chaarani H. The Impact of Audit Committee Oversight on Investor Rationality, Price Expectations, Human Capital, and Research and Development Expense. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(6):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060321

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbraham, Rebecca, Venkata Mrudula Bhimavarapu, and Hani El-Chaarani. 2025. "The Impact of Audit Committee Oversight on Investor Rationality, Price Expectations, Human Capital, and Research and Development Expense" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 6: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060321

APA StyleAbraham, R., Bhimavarapu, V. M., & El-Chaarani, H. (2025). The Impact of Audit Committee Oversight on Investor Rationality, Price Expectations, Human Capital, and Research and Development Expense. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(6), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060321