Financially Savvy or Swayed by Biases? The Impact of Financial Literacy on Investment Decisions: A Study on Indian Retail Investors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Theoretical Background: From Rationality to Behavioural Finance

2.2. Financial Literacy and Investment Decisions

2.3. Behavioural Biases in Investment Decisions

2.4. Mediating Role of Behavioural Biases

2.5. Research Gap

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Non-Response Bias

4.2. Measurement of Behavioural Biases and Financial Literacy

4.3. Reliability Assessment

4.4. Pearson’s Correlation Matrix

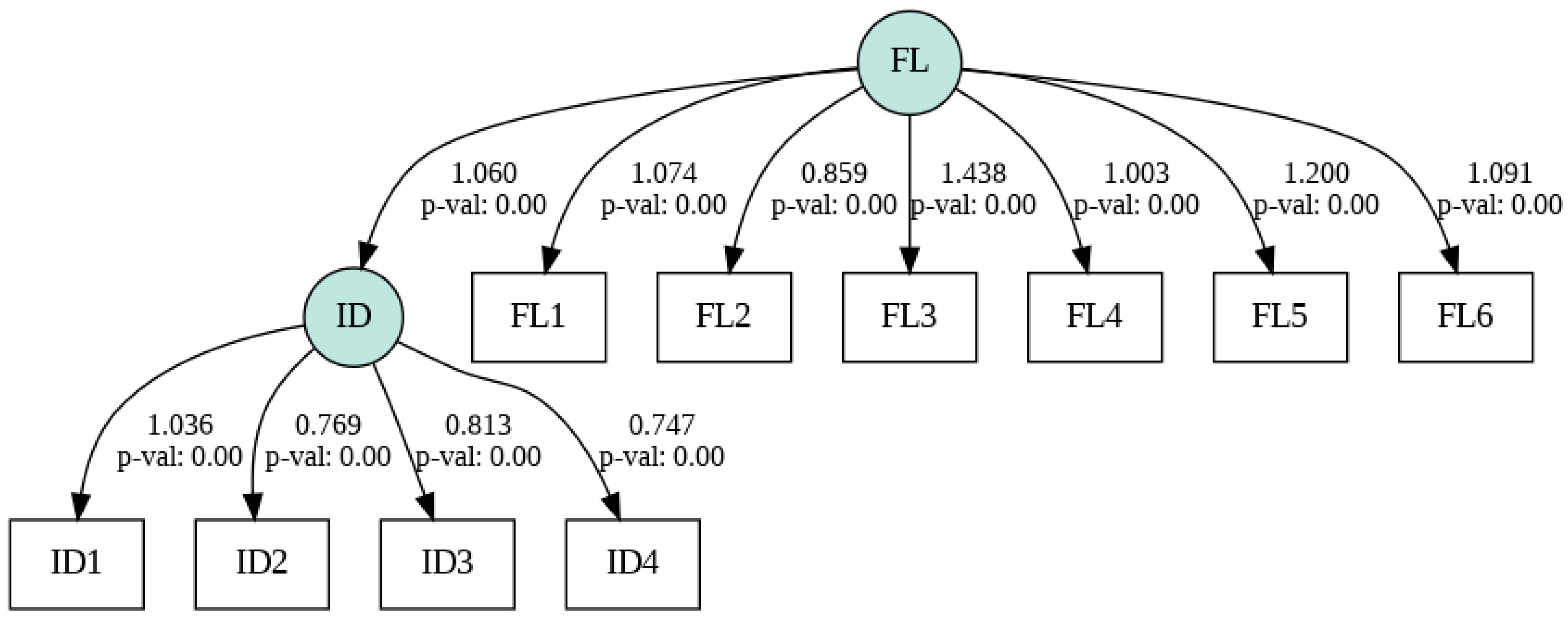

4.5. Model Fit

4.6. Direct Impact of Financial Literacy on Investment Decision

4.7. The Mediating Role of Cognitive Biases

5. Conclusions

6. Implications

7. Limitations and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adil, M., Singh, Y., & Ansari, M. S. (2021). How financial literacy moderate the association between behaviour biases and investment decision? Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 7, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquraan, T., Alqisie, A., & Al Shorafa, A. (2016). Do behavioural finance factors influence the stock investment decisions of individual investors? (Evidences from Saudi Stock Market). Journal of American Science, 12(9), 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Amagir, A., Groot, W., Maassen van den Brink, H., & Wilschut, A. (2018). A review of financial-literacy education programs for children and adolescents. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 17(1), 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianti, B. F. (2018). The influence of financial literacy, financial behaviour and income on investment decision. Economics and Accounting Journal, 1(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, S., Coşkun, A., Şahin, M. A., & Demircan, M. L. (2016). Impact of financial literacy on the behavioural biases of individual stock investors: Evidence from Borsa Istanbul. Business & Economics Research Journal, 7(3), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baihaqqy, M. R. I., Disman, N., Sari, M., & Ikhsan, S. (2020). The effect of financial literacy on the investment decision. Budapest International Research and Critics Institute-Journal (BIRCI-Journal), 3(4), 3073–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H. K., Kumar, S., Goyal, N., & Gaur, V. (2019). How financial literacy and demographic variables relate to behavioural biases. Managerial Finance, 45(1), 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H. K., & Ricciardi, V. (2014). How biases affect investor behaviour. The European Financial Review, 7–10. Available online: https://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/how-biases-affect-investor-behaviour/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N., & Thaler, R. (2003). A survey of behavioral finance. Handbook of the Economics of Finance, 1, 1053–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Barberis, N. C. (2013). Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(1), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S., & Sharma, S. (2000). Herd behaviour in financial markets. IMF Staff Papers, 47(3), 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteska, A., Harasheh, M., & Abedin, M. Z. (2023). Revisiting overconfidence in investment decision-making: Further evidence from the US market. Research in International Business and Finance, 66, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairunnisa, A., & Dalimunthe, Z. (2021). Indonesian stock’s influencer phenomenon: Did financial literacy on millennial age reduce herding behaviour? Journal Akuntansi Dan Keuangan, 23(2), 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Kim, K. A., Nofsinger, J. R., & Rui, O. M. (2007). Trading performance, disposition effect, overconfidence, representativeness bias, and experience of emerging market investors. Journal of behavioural Decision Making, 20(4), 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., & Volpe, R. P. (1998). An analysis of personal financial literacy among college students. Financial Services Review, 7(2), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G., & Kudryavtsev, A. (2012). Investor rationality and financial decisions. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 13(1), 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bondt, W. (2020). Investor and market overreaction: A retrospective. Review of Behavioral Finance, 12(1), 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, I. E., & Fraser-Mackenzie, P. A. (2008). Cognitive biases in human perception, judgment, and decision making: Bridging theory and the real world. In Criminal investigative failures (pp. 79–94). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E. F. (1970). Efficient capital markets. Journal of Finance, 25(2), 383–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L., & Seasholes, M. S. (2005). Do investor sophistication and trading experience eliminate behavioural biases in financial markets? Review of Finance, 9(3), 305–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischhoff, B. (1975). Hindsight is not equal to foresight: The effect of outcome knowledge on judgment under uncertainty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 1(3), 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan Al-Tamimi, H. A., & Anood Bin Kalli, A. (2009). Financial literacy and investment decisions of UAE investors. The Journal of Risk Finance, 10(5), 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J. S., Madrian, B. C., & Skimmyhorn, W. L. (2013). Financial literacy, financial education, and economic outcomes. Annual Review of Economics, 5(1), 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A. O., & Post, T. (2014). Self-attribution bias in consumer financial decision-making: How investment returns affect individuals’ belief in skill. Journal of Behavioural and Experimental Economics, 52, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iram, T., Bilal, A. R., Ahmad, Z., & Latif, S. (2023). Does financial mindfulness make a difference? A nexus of financial literacy and behavioural biases in women entrepreneurs. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 12(1), 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J., Walia, N., & Gupta, S. (2019). Evaluation of behavioral biases affecting investment decision making of individual equity investors by fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. Review of Behavioral Finance, 12(3), 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J., Walia, N., Kaur, M., Sood, K., & Kaur, D. (2023). Shaping investment decisions through financial literacy: Do herding and overconfidence bias mediate the relationship? Global Business Review. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janor, H., Yakob, R., Hashim, N. A., Zanariah, Z., & Wel, C. A. C. (2016). Financial literacy and investment decisions in Malaysia and United Kingdom: A comparative analysis. Geografia, 12(2), 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jappelli, T., & Padula, M. (2013). Investment in financial literacy and saving decisions. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(8), 2779–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, S., Söderberg, I. L., & Wilhelmsson, M. (2017). An investigation of the impact of financial literacy, risk attitude, and saving motives on the attenuation of mutual fund investors’ disposition bias. Managerial Finance, 43(3), 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Riepe, M. W. (1998). Aspects of investor psychology. Journal of Portfolio Management, 24(4), 52-+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1972). Subjective probability: A judgment of representativeness. Cognitive Psychology, 3(3), 430–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 99–127). World Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra Sahi, S., & Pratap Arora, A. (2012). Individual investor biases: A segmentation analysis. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 4(1), 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasoga, P. S. (2021). Heuristic biases and investment decisions: Multiple mediation mechanisms of risk tolerance and financial literacy—A survey at the Tanzania stock market. Journal of Money and Business, 1(2), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., & Goyal, N. (2015). Behavioural biases in investment decision making–a systematic literature review. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 7(1), 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A. (2019). Financial literacy and the need for financial education: Evidence and implications. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 155(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2007). Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial education: The problems are serious, and remedies are not simple. Business Economics, 42, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011). Financial literacy around the world: An overview. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10(4), 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. American Economic Journal: Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). How ordinary consumers make complex economic decisions: Financial literacy and retirement readiness. Quarterly Journal of Finance, 7(3), 1750008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., & Curto, V. (2010). Financial literacy among the young. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, H., Samantaray, A. K., Panigrahi, R. R., & Jena, L. K. (2025). Financial literacy in predicting investment decisions: Do attitude and overconfidence influence? International Journal of Social Economics, 52(2), 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkiel, B. G. (1989). Efficient market hypothesis. In Finance (pp. 127–134). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, K. C., & Metilda, M. J. (2015). A study on the impact of investment experience, gender, and level of education on overconfidence and self-attribution bias. IIMB Management Review, 27(4), 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S. K. (2022). Behaviour biases and investment decision: Theoretical and research framework. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 14(2), 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NE India Broadcast. (2025). India has officially become the world’s fourth-largest economy in 2025, overtakes Japan. NE India Broadcast. Available online: https://neindiabroadcast.com/2025/05/08/india-has-officially-become-the-worlds-fourth-largest-economy-in-2025-overtakes-japan/#google_vignette (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Nunnaly, J. C., Jr., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). Mc-Graw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu, S. P., & Laryea, E. (2023). The impact of anchoring bias on investment decision-making: Evidence from Ghana. Review of Behavioural Finance, 15(5), 729–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D. L., & John, O. P. (1998). Egoistic and moralistic biases in self-perception: The interplay of self-deceptive styles with basic traits and motives. Journal of Personality, 66(6), 1025–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompian, M. M. (2006). Behavioral finance and wealth management: How to build optimal portfolios that account for investor biases. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Prosad, J. M., Kapoor, S., Sengupta, J., & Roychoudhary, S. (2017). Overconfidence and disposition effect in Indian equity market: An empirical evidence. Global Business Review, 19(5), 1303–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R. K. (2020). Past behaviour, financial literacy and investment decision-making process of individual investors. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 15(6), 1243–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmat, I., Khan, A. A., Hussain, M., & Khurshid, S. (2023). An examination of behavioral factors affecting the investment decisions: The moderating role of financial literacy and mediating role of risk perception. Journal of Innovative Research in Management Sciences, 4(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J. R. (2003). Behavioral finance. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 11(4), 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A., Usman, M., & Bashir, Z. (2023). Behavioral biases, financial literacy, and investment decision: A case of individual investors in Pakistan. Business Review, 18(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M., Khan, B., Khan, S. Z., & Khan, R. U. (2021). The impact of heuristic availability bias on investment decision-making: Moderated mediation model. Business Strategy & Development, 4(3), 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U. (2000). Research methods for business (3rd ed). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sekita, S., Kakkar, V., & Ogaki, M. (2022). Wealth, financial literacy and behavioural biases in Japan: The effects of various types of financial literacy. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 64, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. Z. A., Ahmad, M., & Mahmood, F. (2018). Heuristic biases in investment decision-making and perceived market efficiency: A survey at the Pakistan stock exchange. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 10(1), 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefrin, H. (2010). Behavioralizing finance. Foundations and Trends® in Finance, 4(1–2), 1–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (1985). The disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance, 40(3), 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, S. J., Paliwal, U. L., & Dewasiri, N. J. (2024). Unraveling the impact of financial literacy on investment decisions in an emerging market. Business Strategy & Development, 7(1), e337. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, A., Rushdi, N. J., & Katiyar, R. C. (2020). Impact of behavioral biases on investment decisions: A systematic review. International Journal of Management, 11(4), 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Statman, M. (2005). Martha Stewart’s lessons in behavioural finance. Journal of Investment Consulting, 7(2), 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, G. (2024). Impact of financial literacy and behavioural biases on investment decision-making. FIIB Business Review, 13(1), 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekçe, B., Yılmaz, N., & Bildik, R. (2016). What factors affect behavioral biases? Evidence from Turkish individual stock investors. Research in International Business and Finance, 37, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 1(1), 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Think with Niche. (2024). The rise of retail investors and domestic funds in India: A new era of investment. Think with Niche. Available online: https://www.thinkwithniche.com/blogs/details/the-rise-of-retail-investors-and-domestic-funds-in-india-a-new-era-of-investment (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Timmermann, A., & Granger, C. W. (2004). Efficient market hypothesis and forecasting. International Journal of Forecasting, 20(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourani-Rad, A., & Kirkby, S. (2005). Investigation of investors’ overconfidence, familiarity, and socialization. Accounting & Finance, 45(2), 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011). Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(2), 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörös, Z., Szabó, Z., Kehl, D., Kovács, O. B., Papp, T., & Schepp, Z. (2021). The forms of financial literacy overconfidence and their role in financial well-being. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(6), 1292–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, R., Sembel, R., & Malau, M. (2023). How heuristics and herding behaviour biases impacting stock investment decisions with financial literacy as moderating variable. South East Asia Journal of Contemporary Business, Economics and Law, 29(1), 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yanti, F., & Endri, E. (2024). Financial behavior, overconfidence, risk perception and investment decisions: The mediating role of financial literacy. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 14(5), 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulianis, N., & Sulistyowati, E. (2021). The effect of financial literacy, overconfidence, and risk tolerance on investment decision. Journal of Economics, Business, and Government Challenges, 4(01), 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahera, S. A., & Bansal, R. (2018). Do investors exhibit behavioural biases in investment decision making? A systematic review. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 10(2), 210–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Investor Grouping | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 343 | 71.76 |

| Female | 139 | 28.84 | |

| Age | 18–25 years | 89 | 18.46 |

| 25–40 years | 245 | 50.83 | |

| 40–55 years | 94 | 19.5 | |

| Over 55 years | 54 | 11.2 | |

| Education | Up to Senior Secondary (12th) | 47 | 9.75 |

| Graduate | 224 | 46.47 | |

| Postgraduate | 122 | 25.31 | |

| PhD or Other | 89 | 18.46 | |

| Occupation | Self-employed | 124 | 25.73 |

| Private sector employee | 198 | 41.08 | |

| Public sector employee | 87 | 18.05 | |

| Retired | 93 | 15.15 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 179 | 37.14 |

| Unmarried | 274 | 56.85 | |

| Other | 29 | 6.02 | |

| Annual Income | Up to 250,000 | 106 | 21.99 |

| 250,001–600,000 | 168 | 34.85 | |

| 600,001–1,000,000 | 147 | 30.50 | |

| Above 1,000,000 | 61 | 12.66 | |

| Investment Experience | 1–3 years | 212 | 43.98 |

| 3–6 years | 137 | 27.80 | |

| 6–10 years | 83 | 17.22 | |

| More than 10 years | 53 | 11 |

| Variable | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| SA | 0.959 | 0.338 |

| OC | 0.130 | 0.896 |

| H | 1.732 | 0.084 |

| DP | 1.082 | 0.279 |

| R | 0.622 | 0.534 |

| FA | 0.766 | 0.444 |

| AN | 0.382 | 0.70 |

| AV | 0.751 | 0.452 |

| FL | 1.745 | 0.082 |

| ID | 0.764 | 0.445 |

| Behavioural Biases | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| H | 3.44 | 1 |

| SA | 3.40 | 2 |

| DP | 3.38 | 3 |

| AV | 3.32 | 4 |

| R | 3.29 | 5 |

| OC | 3.16 | 6 |

| FA | 2.91 | 7 |

| AN | 2.87 | 8 |

| Statistic | Transformed Value | Financial Literacy Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 4.69 | 58.73% |

| Median | 5.03 | |

| Minimum | 0 | |

| Maximum | 8 | |

| Standard Deviation | 1.88 |

| Factor | No. of Items | Mean | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | 2 | 3.40 | 1.021 | 0.602 |

| OC | 3 | 3.16 | 1.040 | 0.715 |

| H | 5 | 3.44 | 0.954 | 0.774 |

| DP | 5 | 3.38 | 1.042 | 0.723 |

| R | 5 | 3.29 | 0.926 | 0.744 |

| FA | 5 | 2.91 | 1.087 | 0.728 |

| AN | 4 | 2.87 | 1.001 | 0.778 |

| AV | 4 | 3.32 | 1.125 | 0.761 |

| FL | ID | H | OC | SA | DP | FA | A | R | AN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL | 1 | |||||||||

| ID | 0.559 | 1 | ||||||||

| H | −0.419 | 0.443 | 1 | |||||||

| OC | −0.389 | −0.269 | 0.323 | 1 | ||||||

| SA | −0.353 | −0.401 | 0.859 | 0.271 | 1 | |||||

| DP | −0.387 | −0.419 | 0.953 | 0.304 | 0.814 | 1 | ||||

| FA | −0.413 | −0.463 | 0.902 | 0.298 | 0.789 | 0.940 | 1 | |||

| A | −0.345 | −0.384 | 0.867 | 0.253 | 0.696 | 0.900 | 0.879 | 1 | ||

| R | −0.366 | −0.427 | 0.769 | 0.235 | 0.670 | 0.773 | 0.894 | 0.774 | 1 | |

| AN | −0.279 | −0.338 | 0.789 | 0.225 | 0.811 | 0.803 | 0.791 | 0.779 | 0.723 | 1 |

| Fit Indices | Recommended Value | Measurement Model | Structural Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 1235 | 1244 | |

| χ2 p-value | 0.06 | 0.08 | |

| RMSEA | <0.05 (good fit) <0.08 (fair fit) | 0.05 | 0.054 |

| CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.96 | 0.945 |

| GFI | >0.80 | 0.96 | 0.844 |

| AGFI | >0.80 | 0.92 | 0.842 |

| NFI | <0.90 | 0.95 | 0.910 |

| TLI | ≥0.90 | 0.95 | 0.904 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agarwal, A.; Rao, N.V.M.; Nogueira, M.C. Financially Savvy or Swayed by Biases? The Impact of Financial Literacy on Investment Decisions: A Study on Indian Retail Investors. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060322

Agarwal A, Rao NVM, Nogueira MC. Financially Savvy or Swayed by Biases? The Impact of Financial Literacy on Investment Decisions: A Study on Indian Retail Investors. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(6):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060322

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgarwal, Abhilasha, N. V. Muralidhar Rao, and Manuel Carlos Nogueira. 2025. "Financially Savvy or Swayed by Biases? The Impact of Financial Literacy on Investment Decisions: A Study on Indian Retail Investors" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 6: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060322

APA StyleAgarwal, A., Rao, N. V. M., & Nogueira, M. C. (2025). Financially Savvy or Swayed by Biases? The Impact of Financial Literacy on Investment Decisions: A Study on Indian Retail Investors. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(6), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060322