Financial Literacy as a Catalyst for Women’s Economic Empowerment in the MENA Region: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Does financial literacy positively impact women’s financial performance in the Middle East?

- Does autonomy play a stronger role than parental and spousal support in mediating the positive relationship between financial literacy and financial performance?

- Do male partners and employment type moderate the relationship between financial literacy and autonomy, influencing the extent to which financial literacy translates into higher autonomy and improved financial outcomes?

2. Literature Review: Characteristics of Successful Women

2.1. Financial Literacy and Financial Performance

2.2. Factors Affecting Women’s Professional Success

2.2.1. Parental Influences

2.2.2. Spousal Support

2.2.3. Autonomy

2.2.4. Male Partners

3. Research Methodology

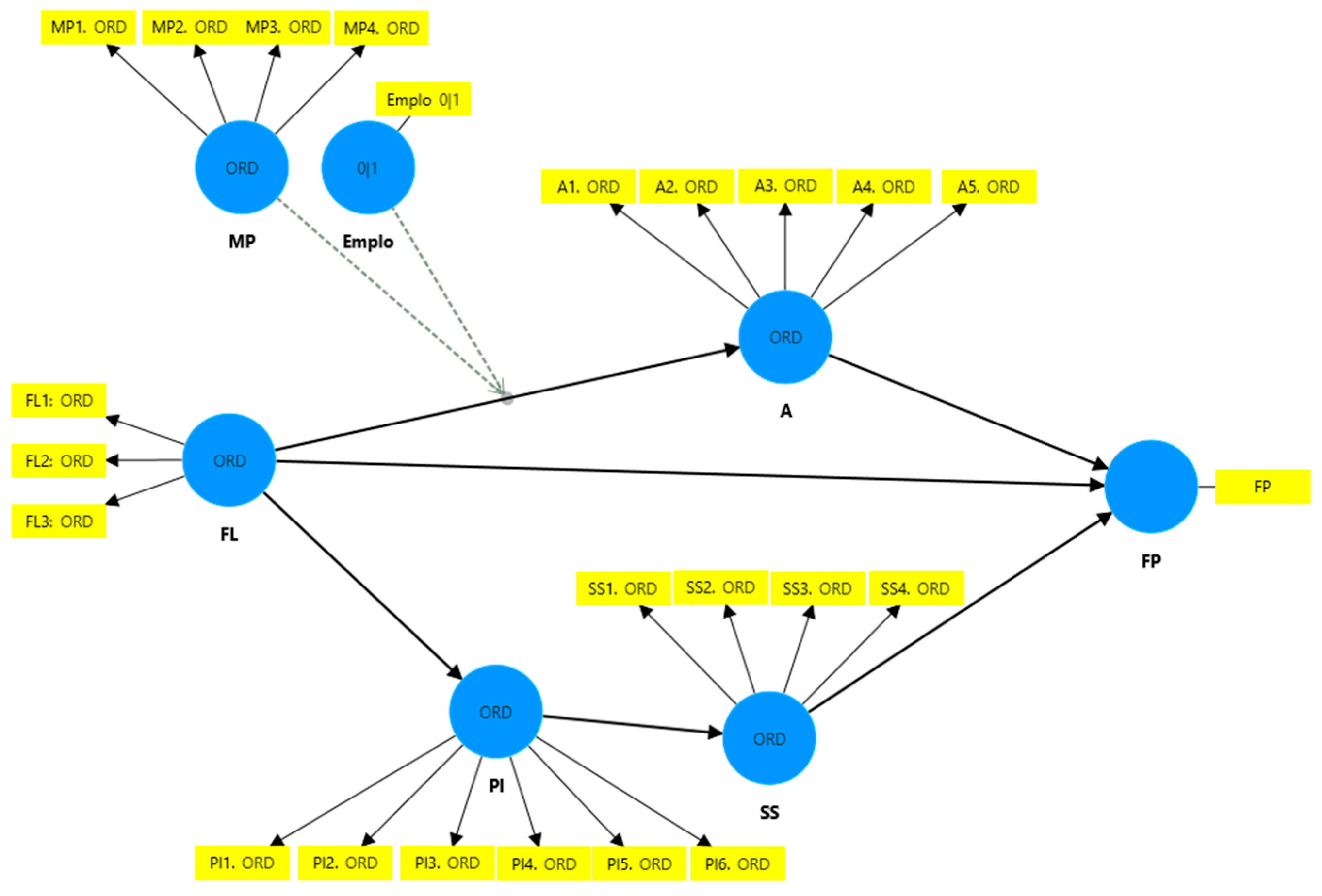

3.1. Analytical Approach

3.2. Data Description

3.3. The Variables and Conceptual Model

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Univariate Analysis

4.2. Bootstrap Results

4.2.1. Pre-Estimation Tests

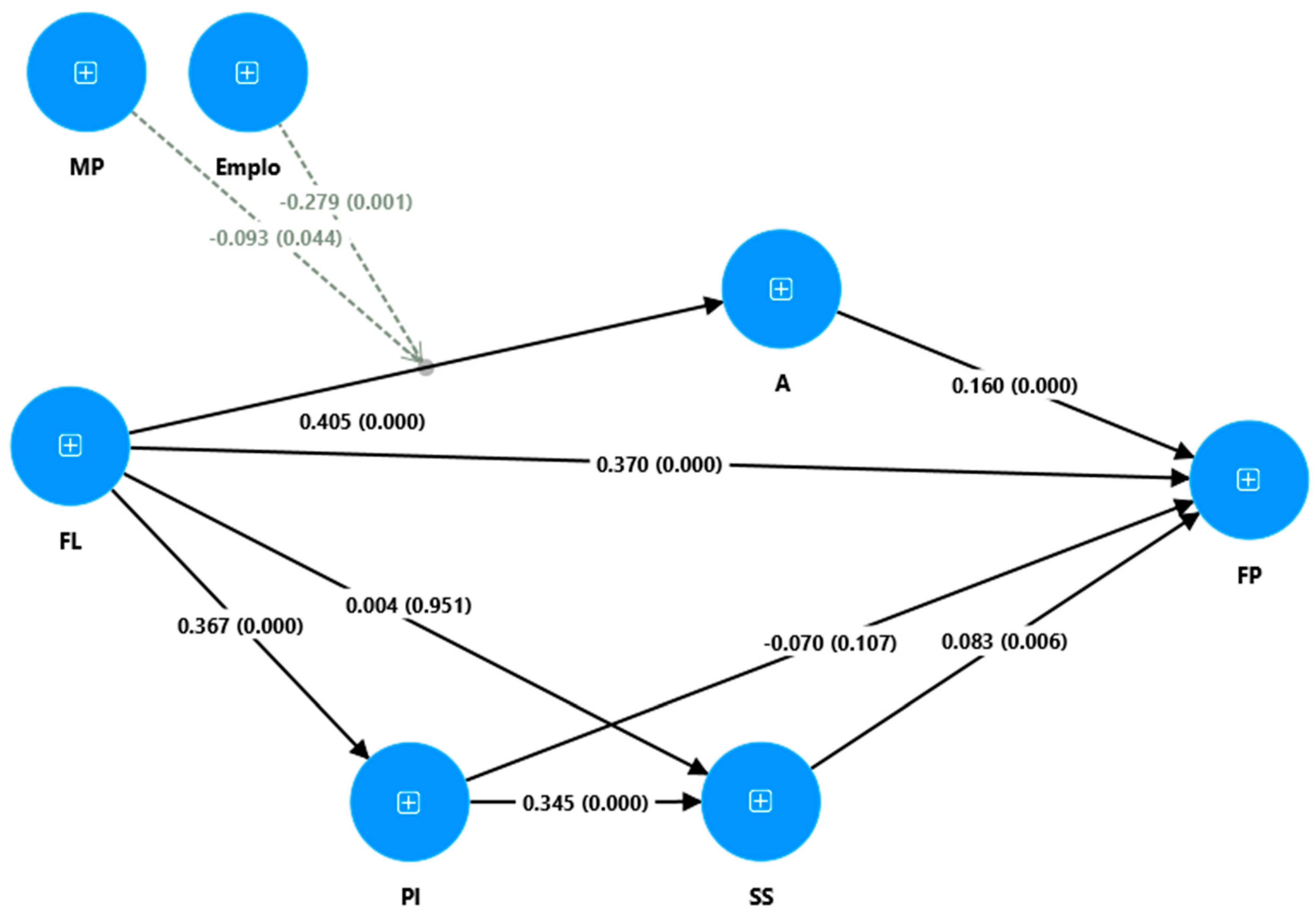

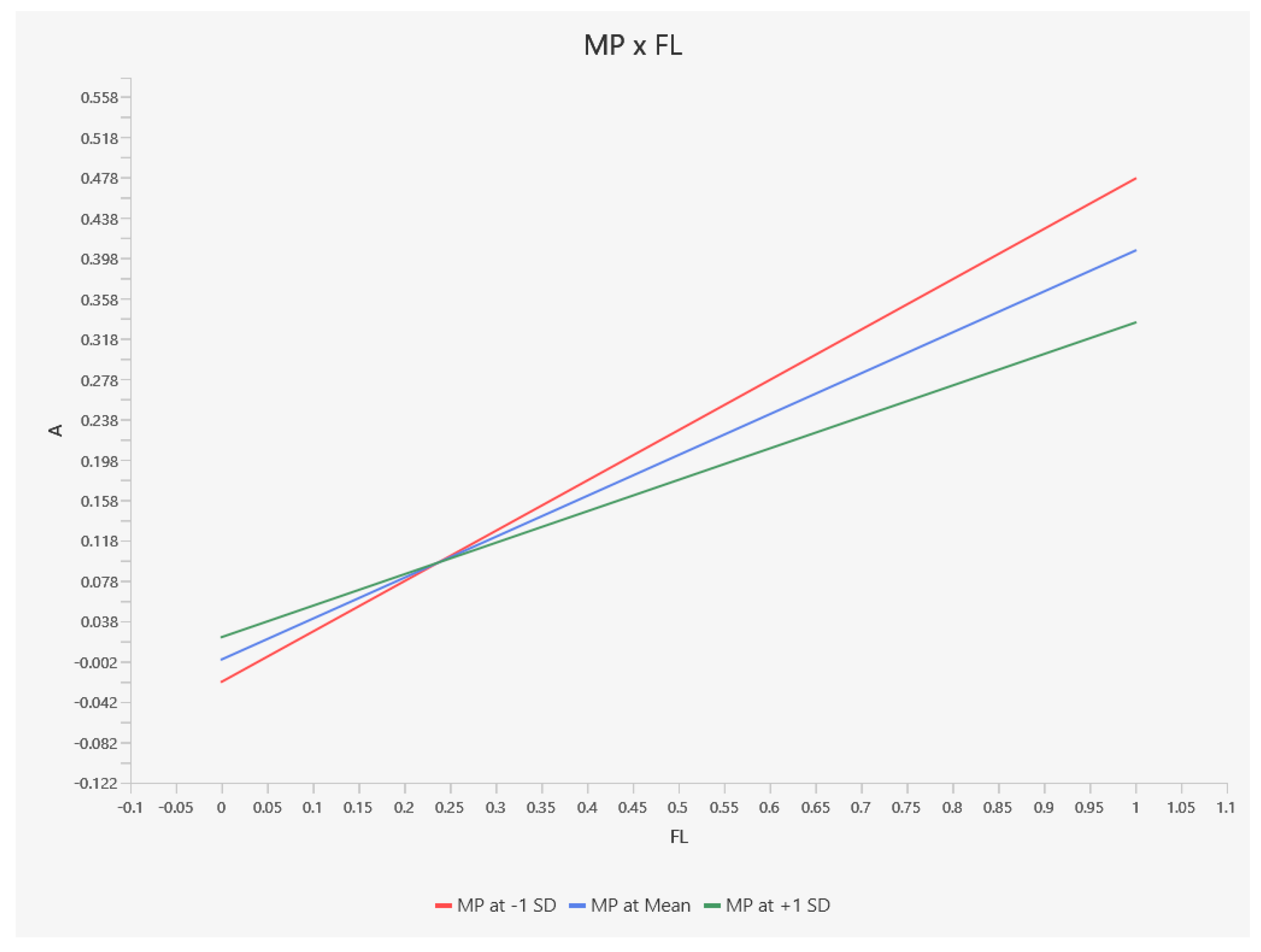

4.2.2. Results and Discussion

4.3. Discussion of Findings

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Fostering autonomy: policies should focus on empowering women’s autonomy in working environments and society.

- Financial education: setting up programs and initiatives aimed at improving financial literacy among women can help enhance their professional success.

- Support systems: Providing support systems, such as mentoring programs or networking opportunities, can help women navigate the challenges and balance personal and professional responsibilities.

- Women-friendly HR policies: to provide further autonomy and organizational support necessary for the growth and advancement of women within organizations.

- Policy changes: working on designing policies that promote gender equality and support women-owned businesses can create a more favorable environment for women entrepreneurs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdallah, W., Harraf, A., Ghura, H., & Abrar, M. (2025). Financial literacy and small and medium enterprises performance: The moderating role of financial access. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(4), 1345–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmetaj, B., Kruja, A. D., & Hysa, E. (2023). Women entrepreneurship: Challenges and perspectives of an emerging economy. Administrative Sciences, 13(4), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hakim, G., Bastian, B. L., Ng, P. Y., & Wood, B. P. (2022). Women’s empowerment as an outcome of NGO projects: Is the current approach sustainable? Administrative Sciences, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammadi, S., & Rahman, S. A. (2025). Financial bootstrapping: A case of women entrepreneurs in context of digital economy. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgood, S., & Walstad, W. B. (2016). The effects of perceived and actual financial literacy on financial behaviors. Economic Inquiry, 54, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsos, G. A., Isaksen, E. J., & Ljunggren, E. (2006). New venture financing and subsequent business growth in men-and women-led businesses. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwadi, A. K., Magableh, F. A., Tawfiq, T. T., & Shiyyab, F. (2025). Female investors and corporate performance: An empirical analysis in the Jordanian context. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2494714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamahery, A., & Qamruzzaman, M. (2022). Do access to finance, technical know-how, and financial literacy offer women empowerment through women’s entrepreneurial development? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 776844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atshan, N. A., Zaid, M. I., AL-Abrrow, H., & Abbas, S. (2024). Entrepreneurial motivations of women in the middle east. In Entrepreneurial motivations: Strategies, opportunities and decisions (pp. 151–172). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Awotoye, Y. F., & Stevens, C. E. (2023). Gendered perceptions of spousal support and entrepreneurial intention: Evidence from Nigeria. American Journal of Management, 23(2), 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baporikar, N. A., & Akino, S. (2020). Financial literacy imperative for success of women entrepreneurship. International Journal of Innovation in the Digital Economy (IJIDE), 11(3), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinger, E., Dömötör, B., Megyeri, K., & Walter, G. (2025). Financial literacy of finance students: A behavioral gender gap. International Journal of Educational Management, 39(8), 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B., & Brush, C. (2022). A gendered perspective on organizational creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(3), 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, R. J., & Nucci, A. R. (2000). On the survival prospects of men’s and women’s new business ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(4), 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, B., Loots, E., Stroet, P., & van Witteloostuijn, A. (2025). Passionately or reluctantly independent? Artistic and non-artistic self-employment compared. Journal of Cultural Economics, 49, 515–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, D., Bamberry, L., Wulff, E., & Krivokapic-SKOKO, B. (2022). “A trade of one’s own”: The role of social and cultural capital in the success of women in male-dominated occupations. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(2), 371–387. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S., Shaw, E., Lam, W., & Wilson, F. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurship, and bank lending: The criteria and processes used by bank loan officers in assessing applications. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, A., Brush, C. G., & Welter, F. (2007). Advancing a framework for coherent research on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., & Brieger, S. A. (2022). When discrimination is worse, autonomy is key: How women entrepreneurs leverage job autonomy resources to find work–life balance. Journal of Business Ethics, 177, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaa, N. M., Abidin, A. Z. U., & Roller, M. (2024). Examining the relationship of career crafting, perceived employability, and subjective career success: The moderating role of job autonomy. Future Business Journal, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, M. C., & Brush, C. (2012). Gender and business ownership: Questioning “what” and “why”. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 18, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W. G., Dyer, W. J., & Gardner, R. G. (2013). Should my spouse be my partner? Preliminary evidence from the panel study of income dynamics. Family Business Review, 26, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpe, I. (2011). Women entrepreneurs and economic development in Nigeria: Characteristics for success. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(1), 287–291. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Isidore-Ekpe/publication/268177390_Women_Entrepreneurs_and_Economic_Development_in_Nigeria_Characteristics_for_Success/links/555b1f2908ae6fd2d828ce30/Women-Entrepreneurs-and-Economic-Development-in-Nigeria-Characteristics-for-Success.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Elsaman, H. A., El-Bayaa, N., & Kousihan, S. (2022). Measuring and validating the factors influenced the SME business growth in Germany—Descriptive analysis and construct validation. Data, 7(11), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, F., Antoni, D., & Suwarni, E. (2021). Mapping potential sectors based on financial and digital literacy of women entrepreneurs: A study of the developing economy. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 10(2), 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graña-Alvarez, R., Lopez-Valeiras, E., Gonzalez-Loureiro, M., & Coronado, F. (2024). Financial literacy in SMEs: A systematic literature review and a framework for further inquiry. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(1), 331–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., Wasti, S. A., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J., Salia, S., & Karim, A. (2018). Is knowledge that powerful? Financial literacy and access to finance: An analysis of enterprises in the UK. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 25(6), 985–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iram, T., Bilal, A. R., Ahmad, Z., & Latif, S. (2023). Does financial mindfulness make a difference? A Nexus of financial literacy and behavioural biases in women entrepreneurs. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 12(1), 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Iram, T., Bilal, A. R., & Latif, S. (2024). Is awareness that powerful? Women’s financial literacy support to prospects behaviour in prudent decision-making. Global Business Review, 25, 1356–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwatsubo, K., Araki, C., & Yamori, N. (2025). Gender gap in financial literacy—Numeracy, financial concepts and retirement financial planning. Finance Research Open, 1(4), 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, E. J., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? The Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, M. M., Perez-Fuentes, M. C., Atria, L., Ruiz, N. F. A., & Linares, J. J. G. (2019). Burnout, perceived efficacy, and job satisfaction: Perception of the educational context in high school teachers. BioMed Research International, 55(4), 505–515. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. A., Noreen, S., & Shahzadi, A. (2024). International trade, economic development, and inflation: Panel data analysis from South Asian economies. Journal of Development and Social Sciences, 5, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L., Wong, P. K., Der Foo, M., & Leung, A. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of organizational and individual factors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Lin, P. Y., Chien, C. Y., Fang, F. M., & Wang, L. J. (2018). A comparison of psychological well-being and quality of life between spouse and non-spouse caregivers in patients with head and neck cancer: A 6-month follow-up study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14(10), 1697–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M., Brush, C., & Hisrich, R. (1997). Israeli women entrepreneurs: An examination of factors affecting performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 315–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, M., Mawad, J. L., & Lalkovska, N. (2024, September 27–29). Towards sustainable green transition in Lebanon and Syria. FEMISE 2023 Annual Conference, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Mawad, J. L. (2022). Does good financial behavior reduce the negative impact of financial fragility on individuals’ financial optimism? The never-ending Lebanese crisis case. International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies, 6(3), 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawad, J. L., Athari, S. A., Khalife, D., & Mawad, N. (2022). Examining the impact of financial literacy, financial self-control, and demographic determinants on individual financial performance and behavior: An Insight from the Lebanese crisis period. Sustainability, 14, 15129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawad, J. L., & Freiha, S. (2024). Entrepreneurial intentions in the absence of banking services: The case of the Lebanese in crises. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawad, J. L., & Makki, M. (2023). Reflections on the initiatives of NGOs, INGOs, and UN organizations in eradicating poverty in Lebanon through the case study of RMF. Arab Economic and Business Journal, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D., Agarwal, N., Sharahiley, S., & Kandpal, V. (2024). Digital financial literacy and its impact on financial decision-making of women: Evidence from India. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkini Lugalla, I., Jacobs, J. P., & Westerman, W. (2023). What drives women entrepreneurs in tourism in Tanzania? Journal of African Business, 25(2), 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordi, C., & Okafor, C. (2010). Women entrepreneurship development in Nigeria: The effect of environmental factors. Petroleum-Gas University of Ploiesti Bulletin, 62(4), 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moudrý, D. V., & Thaichon, P. (2020). Enrichment for retail businesses: How female entrepreneurs and masculine traits enhance business success. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M., Shahzad, F., & Misbah Shabana, M. (2024). Digital entrepreneurship among Egyptian women: Autonomy, experience and community. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 31(7), 1378–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadgrodkiewicz, A. (2011). Empowering women entrepreneurs: The impact of the 2006 trade organizations ordinance in Pakistan. Center for International Private Enterprise. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. H. H., Ntim, C. G., & Malagila, J. K. (2020). Women on corporate boards and corporate financial and non-financial performance: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Review of Financial Analysis, 71, 101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2018). G20/OECD–INFE policy guidance on digitalisation and financial literacy. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Poggesi, S., Mari, M., & De Vita, L. (2017). Women entrepreneurs and work-family conflict: Analysis of the antecedents. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 44(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, E. G., & Nagarajan, K. V. (2005). Successful women entrepreneurs as pioneers: Results from a study conducted in Karaikudi, Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 18(1), 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, A., & Wright, R. E. (2024). When does the gender gap in financial literacy begin? Economic Record, 100(328), 44–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, I., Zubair, A., & Anwar, M. (2019). Role of perceived self-efficacy and spousal support in psychological well-being of female entrepreneurs. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 34, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, V., Barry, D., & Ketchen, D. J., Jr. (2009). Entrepreneuring as emancipation. Academy of Management Review, 34, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2024). SmartPLS. (Version 4) [Computer software]. SmartPLS.

- Sadaf, F., Bano, S., & Rahat, R. (2024). First-generation female professors from low-income families in Pakistan: The influence of parents on access to and involvement in higher education. Sociological Inquiry, 94(4), 1025–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, D., Youssef, D., EL-Bayaa, N., Alzoubi, Y. I., & Zaim, H. (2023). The impact of diversity on job performance: Evidence from private universities in Egypt. Acta Innovations, 49, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhi, Z. S. (2024). Striving for autonomy and feminism: What possibilities for Saudi Women? Diogenes, 65, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, A. E., Barbieri, C., & Jakes, S. (2023). Cultivating success: Personal, family and societal attributes affecting women in agritourism. In Gender and tourism sustainability. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, Y. A., Ali, M., Yaqub, M. Z., Ali, I., & Badghish, S. (2024). Financial education is more precious than money-examining the role of financial literacy in enhancing financial wellbeing among Saudi women. International Journal of Business Performance Management, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniewski, M. W., Awruk, K., Leonardi, G., & Słomski, W. (2024). Family determinants of entrepreneurial success-The mediational role of self-esteem and achievement motivation. Journal of Business Research, 171, 114383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D. M., & Meek, W. R. (2012). Gender and entrepreneurship: A review and process model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27, 428–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadnjal, M. (2018). The influence of parents on female entrepreneurs in three career development phases. Management, 13, 18544223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2021). The world bank in lebanon overview. Available online: https://worldbank.org (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Yan, D., Wang, C. C., & Sunindijo, R. Y. (2024). Framework for promoting women’s career development across career stages in the construction industry. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 150, 04024062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Ishtiaq, M., & Anwar, M. (2018). Enterprise risk management practices and firm performance, the mediating role of competitive advantage and the moderating role of financial literacy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 11(3), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country of Residence | Lebanon | 473 | 91.8 |

| UAE | 23 | 4.5 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 11 | 2.1 | |

| Egypt | 4 | 0.8 | |

| Turkey | 4 | 0.8 | |

| Education Level | Undergraduate | 146 | 28.4 |

| Graduate | 369 | 71.6 | |

| Employment Type | Entrepreneur | 277 | 53.8 |

| Employee | 238 | 46.2 | |

| Marital Status | Married/In a Relationship | 389 | 75.5 |

| Single | 126 | 24.5 | |

| Business Sector | Education | 65 | 12.6 |

| Consulting and Training | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Arts and Design | 20 | 3.9 | |

| Fashion and Retail | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Finance and Financial Advisory | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Marketing and Media | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Fitness and Wellness | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Food and Agriculture | 30 | 5.8 | |

| Hospitality and Tourism | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Legal and Law Firms | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Health and Medical | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Engineering and Architecture | 5 | 1.0 | |

| Humanitarian and Non-Profit | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Entrepreneurship and Small Business | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Trade and Commerce | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Insurance and Investments | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Events and Performance Venues | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Jewelry and Handicrafts | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Transportation and Logistics | 10 | 1.9 | |

| Miscellaneous (Other Sectors) | 50 | 9.7 |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Kurtosis | Skewness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 24 | 53 | 40.392 | 6.322 | −0.351 | −0.395 |

| A | 3 | 5 | 4.443 | 0.578 | −0.274 | −0.698 |

| FL | 1 | 5 | 3.942 | 0.954 | 0.231 | −0.719 |

| PI | 1 | 5 | 4.262 | 0.997 | 1.618 | −1.484 |

| SS | 1 | 5 | 4.101 | 1.092 | 1.172 | −1.397 |

| MP | 1 | 5 | 3.125 | 1.277 | −0.863 | −0.276 |

| FP | 0 | 4 | 2.584 | 0.988 | −0.482 | −0.23 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | N of Items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.833 | 0.857 | 0.882 | 0.6 | 5 |

| FL | 0.822 | 0.848 | 0.892 | 0.735 | 3 |

| MP | 0.933 | 1.072 | 0.934 | 0.781 | 6 |

| PI | 0.851 | 0.885 | 0.889 | 0.575 | 4 |

| SS | 0.748 | 0.767 | 0.842 | 0.575 | 4 |

| A | Emplo | FL | FP | MP | PI | SS | MP × FL | Emplo × FL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||||||||

| Emplo | 0.45 | ||||||||

| FL | 0.336 | 0.144 | |||||||

| FP | 0.28 | 0.434 | 0.426 | ||||||

| MP | 0.118 | 0.136 | 0.118 | 0.108 | |||||

| PI | 0.138 | 0.249 | 0.408 | 0.086 | 0.269 | ||||

| SS | 0.149 | 0.093 | 0.186 | 0.134 | 0.256 | 0.429 | |||

| MP × FL | 0.109 | 0.093 | 0.177 | 0.039 | 0.155 | 0.089 | 0.119 | ||

| Emplo × FL | 0.124 | 0.087 | 0.811 | 0.303 | 0.108 | 0.363 | 0.13 | 0.147 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Original Sample (O) | p Values | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effects | ||||

| Direct path | FL -> FP | 0.42 | 0 | Significant at 5% |

| Specific indirect effects | ||||

| Simple Mediation | FL -> A -> FP | 0.065 | 0.002 | Significant at 5% |

| Moderated Mediation (MP × FL) | MP x FL -> A -> FP | −0.015 | 0.059 | Insignificant at 5% |

| Moderated Mediation (Emplo × FL) | Emplo x FL -> A -> FP | −0.045 | 0.018 | Significant at 5% |

| Serial Mediation | FL -> PI -> SS -> FP | 0.011 | 0.012 | Significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mawad, J.L.; El-Bayaa, N.; Salameh-Ayanian, M. Financial Literacy as a Catalyst for Women’s Economic Empowerment in the MENA Region: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110607

Mawad JL, El-Bayaa N, Salameh-Ayanian M. Financial Literacy as a Catalyst for Women’s Economic Empowerment in the MENA Region: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(11):607. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110607

Chicago/Turabian StyleMawad, Jeanne Laure, Nourhan El-Bayaa, and Madonna Salameh-Ayanian. 2025. "Financial Literacy as a Catalyst for Women’s Economic Empowerment in the MENA Region: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 11: 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110607

APA StyleMawad, J. L., El-Bayaa, N., & Salameh-Ayanian, M. (2025). Financial Literacy as a Catalyst for Women’s Economic Empowerment in the MENA Region: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(11), 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110607