Collecting Data on the Social Determinants of Health to Advance Health Equity in Cancer Care in Canada: Patient and Community Perspectives

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. SDOH Data Collection Tool

2.3. Phase 1—Patient Survey

2.3.1. Participants

2.3.2. Data Collection

2.3.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Phase 2—Community Consultation

2.4.1. Participants

2.4.2. Data Collection

2.4.3. Data Analysis

2.4.4. Data Integration

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1—Survey Findings

3.1.1. Survey Participant Characteristics

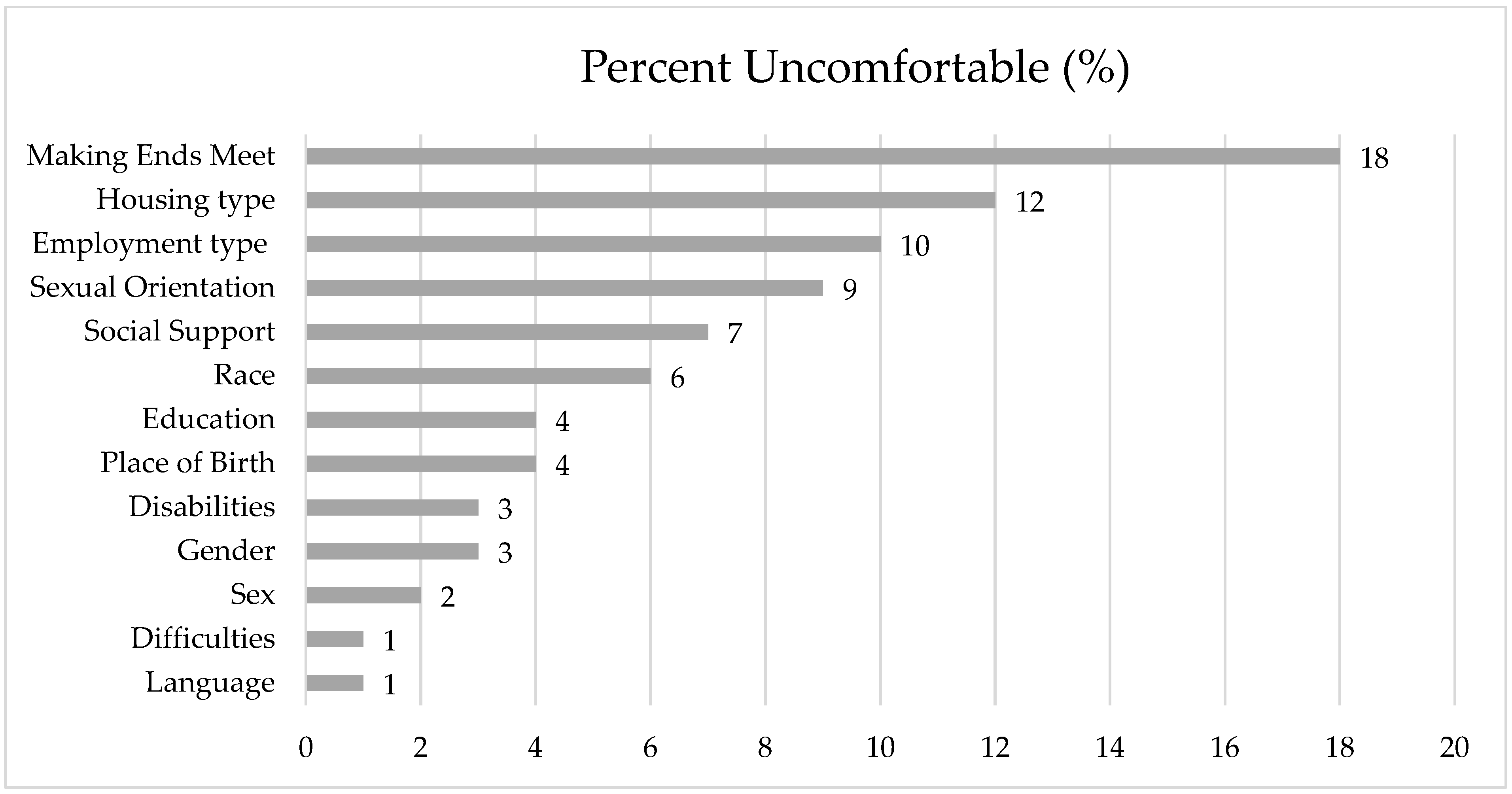

3.1.2. Comfort with SDOH Collection by the Hospital

3.1.3. Comprehensiveness of Response Options

3.1.4. Preferred Method of SDOH Data Collection

3.1.5. Comfort with Storage of SDOH in the EHR

3.1.6. Experiences with Discrimination

3.1.7. Participant Perspectives

Theme 1: Concerns About Privacy and Confidentiality

Theme 2: Concerns About Bias and Discrimination

Theme 3: Lack of Understanding About Relevance to Care

Theme 4: Accuracy of Data

3.2. Phase 2—Community Consultation Findings

3.2.1. Community Perspectives

Theme 1: Accountability

Theme 2: Transparency

Theme 3: Patient Consent

Theme 4: Data Quality

3.3. Recommendations

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary

4.2. Comfort with the Collection of SDOH That Is Less Stigmatizing

4.3. Concerns About Discrimination and Impact on Care

4.4. Preferred Method of SDOH Data Collection

4.5. Integration of SDOH in the EHR

4.6. Desire for Action

4.7. Recommendations

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDOH | Social Determinants of Health |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| HCP | Healthcare provider |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| EMPaCT | Equity-Mobilizing Partnerships in Community |

| SPARK | Screening for Poverty And Related social determinations to improve Knowledge |

References

- Warkentin, M.T.; Ruan, Y.; Ellison, L.F.; Billette, J.-M.; Demers, A.; Liu, F.-F.; Brenner, D.R. Progress in site-specific cancer mortality in Canada over the last 70 years. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R. Disparity in Cancer Care: A Canadian Perspective. Curr. Oncol. 2012, 19, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Examining Disparities in Cancer Control in Canada: A Story of Gaps, Opportunities and Successes; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kerner, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Fung, S.; Landry, C.; Lockwood, G.; Zitzelsberger, L.; Mai, V. Canadian Cancer Screening Disparities: A Recent Historical Perspective. Curr. Oncol. 2015, 22, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwee, J.; Bougie, E. Do cancer incidence and mortality rates differ among ethnicities in Canada? Health Rep. 2021, 32, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. What Makes Canadians Healthy or Unhealthy?—Canada.ca. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health/what-makes-canadians-healthy-unhealthy.html (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. 2016 Cancer System Performance Report: Lower Income Patients Less Likely to Survive Cancer. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeife, D.A.; Padmore, G.; Vaska, M.; Truong, T.H. Ensuring equitable access to cancer care for Black patients in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2022, 194, E1416–E1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comeau, D.; Johnson, C.; Bouhamdani, N. Review of current 2SLGBTQIA+ inequities in the Canadian health care system. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1183284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalonde, M. A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians: A Working Document; Minister of Supply and Services Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/action-on-the-social-determinants-of-health-for-advancing-equity/world-report-on-social-determinants-of-health-equity/commission-on-social-determinants-of-health (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Pinto, A.D.; Glattstein-Young, G.; Mohamed, A.; Bloch, G.; Leung, F.-H.; Glazier, R.H. Building a Foundation to Reduce Health Inequities: Routine Collection of Sociodemographic Data in Primary Care. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2016, 29, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Tan, X.; Padman, R. Social determinants of health in electronic health records and their impact on analysis and risk prediction: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1764–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Bergen, N.; Schlotheuber, A. Promoting health equity: WHO health inequality monitoring at global and national levels. Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 29034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofters, A.; Schuler, A.; Slater, M.; Baxter, N.; Persaud, N.; Pinto, A.; Kucharski, E.; Davie, S.; Nisenbaum, R.; Kiran, T. Using self-reported data on the social determinants of health in primary care to identify cancer screening disparities: Opportunities and challenges. BMC Fam. Pract. 2017, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petkovic, J.; Duench, S.L.; Welch, V.; Rader, T.; Jennings, A.; Forster, A.J.; Tugwell, P. Potential harms associated with routine collection of patient sociodemographic information: A rapid review. Health Expect. 2018, 22, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabet, C.; Hammond, A.; Ravid, N.; Tong, M.S.; Stanford, F.C. Harnessing big data for health equity through a comprehensive public database and data collection framework. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthie, S.; Peacey, V.; Evans, S.; Phillips, V.; Roman-Urrestarazu, A.; Brayne, C.; Lafortune, L. A Scoping Review of Approaches to Improving Quality of Data Relating to Health Inequalities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, S.B.; Pitts, S.B.J.; Iasiello, J.; Mejia, C.; Quinn, A.W.; Popowicz, P.; Mitsakos, A.; Parikh, A.A.; Snyder, R.A. A Mixed-Methods Study to Evaluate the Feasibility and Acceptability of Implementing an Electronic Health Record Social Determinants of Health Screening Instrument into Routine Clinical Oncology Practice. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 7299–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Raymond, G. A deprivation index for health planning in Canada. Chronic Dis. Can. 2009, 29, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, A.; Warsame, K.; Naik, H.; Byrne, W.; Parnia, A.; Siddiqi, A. Identifying gaps in COVID-19 health equity data reporting in Canada using a scorecard approach. Can. J. Public Health 2021, 112, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Public Health Association. CPHA Calls for Culturally Safe Collection and Use of Socio-Demographic and Race-Based Data. Available online: https://www.cpha.ca/cpha-calls-culturally-safe-collection-and-use-socio-demographic-and-race-based-data (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Government of Ontario. Ontario Health Data Council Report: A Vision for Ontario’s Health Data Ecosystem. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-health-data-council-report-vision-ontarios-health-data-ecosystem (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Government of Nova Scotia. Action for Health A Strategic Plan. (2022–2026). Available online: https://actionforhealth.novascotia.ca/sites/default/files/2023-09/action-for-health-strategic-plan-for-nova-scotia.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Government of British Columbia. B.C. Social Determinants of Health Value Set—Province of British Columbia. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/health-information-standards/standards-catalogue/bc-social-determinants-of-health-standards (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Gold, R.; Cottrell, E.; Bunce, A.; Middendorf, M.; Hollombe, C.; Cowburn, S.; Mahr, P.; Melgar, G. Developing Electronic Health Record (EHR) Strategies Related to Health Center Patients’ Social Determinants of Health. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2017, 30, 428–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, M.N.; Thorpe, L. Integrating Data on Social Determinants of Health into Electronic Health Records. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofters, A.K.; Shankardass, K.; Kirst, M.; Quiñonez, C. Sociodemographic Data Collection in Healthcare Settings. Med. Care 2011, 49, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirst, M.; Shankardass, K.; Bomze, S.; Lofters, A.; Quiñonez, C. Sociodemographic data collection for health equity measurement: A mixed methods study examining public opinions. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.W.; Hasnain-Wynia, R.; Kandula, N.R.; Thompson, J.A.; Brown, E.R. Attitudes Toward Health Care Providers, Collecting Information About Patients’ Race, Ethnicity, and Language. Med. Care 2007, 45, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandula, N.R.; Hasnain-Wynia, R.; Thompson, J.A.; Brown, E.R.; Baker, D.W. Association Between Prior Experiences of Discrimination and Patients’ Attitudes Towards Health Care Providers Collecting Information About Race and Ethnicity. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, T.; Sandhu, P.; Aratangy, T.; Devotta, K.; Lofters, A.; Pinto, A.D. Patient perspectives on routinely being asked about their race and ethnicity Qualitative study in primary care. Can. Fam. Physician 2019, 65, E363–E369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Davis, V.H.; Dainty, K.N.; Dhalla, I.A.; Sheehan, K.A.; Wong, B.M.; Pinto, A.D.; Ramalho, A. “Addressing the bigger picture”: A qualitative study of internal medicine patients’ perspectives on social needs data collection and use. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adekoya, I.; Delahunty-Pike, A.; Howse, D.; Kosowan, L.; Seshie, Z.; Abaga, E.; Cooney, J.; Robinson, M.; Senior, D.; Zsager, A.; et al. Screening for poverty and related social determinants to improve knowledge of and links to resources (SPARK): Development and cognitive testing of a tool for primary care. BMC Prim. Care 2023, 24, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ontario Health. Equity, Inclusion, Diversity and Anti-Racism|Ontario Health. Available online: https://www.ontariohealth.ca/system/equity/framework (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- University Health Network. Welcome to the Princess Margaret. Available online: https://www.uhn.ca/PrincessMargaret (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Graham, I.D.; Logan, J.; Harrison, M.B.; Straus, S.E.; Tetroe, J.; Caswell, W.; Robinson, N. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2006, 26, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayani, A.; Maybee, A.; Manthorne, J.; Nicholson, E.; Bloch, G.; Parsons, J.A.; Hwang, S.W.; Shaw, J.A.; Lofters, A. Equity-Mobilizing Partnerships in Community (EMPaCT): Co-Designing Patient Engagement to Promote Health Equity. World Health Popul. 2022, 24, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: The Checklist for reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’CAthain, A.; Murphy, E.; Nicholl, J. The Quality of Mixed Methods Studies in Health Services Research. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2008, 13, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, R. We Ask Because We Care: The Tri-Hospital and Toronto Public Health Health Equity Data Collection Research Project; Toronto Public Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, R.; Damba, C.; Bryant, S. Measuring Quality at a System Level. World Health Popul. 2013, 16, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University Health Network. Sexual & Gender Diversity in Cancer. Available online: https://www.uhn.ca/PrincessMargaret/PatientsFamilies/Specialized_Program_Services/Pages/sexual_gender_diversity.aspx (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayani, A.; Monteith, L.; Shahil-Feroz, A.; Srinivasan, D.; Amsdr, I.; Awil, F.; Cordeaux, E.; Garcia, V.; Hinds, R.; Jeji, T.; et al. Mobilizing the Power of Lived/Living Experiences to Improve Health Outcomes for all. Health Expect. 2025, 28, e70212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nong, P.; Raj, M.; Creary, M.; Kardia, S.L.R.; Platt, J.E. Patient-Reported Experiences of Discrimination in the US Health Care System. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2029650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, D.M.; Meyer, I.H. Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 51, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Medical Association. CMA 2021 National Physician Health Survey; Canadian Medical Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://digitallibrary.cma.ca/link/digitallibrary17 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Wark, K.; Cheung, K.; Wolter, E.; Avey, J.P. “Engaging stakeholders in integrating social determinants of health into electronic health records: A scoping review”. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2021, 80, 1943983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caicedo, N.M.A.; Parry, E.; Arslan, N.; Park, S. Integration of social determinants of health information within the primary care electronic health record: A systematic review of patient perspectives and experiences. BJGP Open 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SDH Card Study Implementation Team; Lewis, J.H.; Whelihan, K.; Navarro, I.; Boyle, K.R. Community health center provider ability to identify, treat and account for the social determinants of health: A card study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, R.C.; Proser, M.; Jester, M.; Li, V.; Hood-Ronick, C.M.; Gurewich, D. Collecting Social Determinants of Health Data in the Clinical Setting: Findings from National PRAPARE Implementation. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2020, 31, 1018–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretz, P.; Shapiro, A.; Santos, L.; Ogaye, K.; Deland, E.; Steel, P.; Meyer, D.; Iyasere, J. Social Determinants of Health Screening and Management: Lessons at a Large, Urban Academic Health System. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2023, 49, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baines, D.; Clark, N.; Bennett, B. Doing Anti-Oppressive Social Work: Rethinking Theory and Practice; Fernwood Publishing: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, J.L.; Akinnibosun, R.; Puri, N.; D’aGostino, N.; Drake, E.K.; Tsimicalis, A.; Howard, A.F.; Garland, S.N.; Chalifour, K.; Gupta, A.A. A comparison of the sociodemographic, medical, and psychosocial characteristics of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer recruited in-person and online: A Canadian cross-sectional survey. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Ethnocultural Diversity in Canadian Cities—Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/7238-ethnocultural-diversity-canadian-cities (accessed on 29 June 2025).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Participant (n = 454) | |

| Patient | 507 (93) |

| Caregiver | 36 (7) |

| Born in Canada (n = 519) | 324 (62) |

| Sex assigned at birth (n = 541) | |

| Male | 272 (50) |

| Female | 269 (49) |

| Gender (n = 544) | |

| Man | 270 (50) |

| Women | 267 (49) |

| Non-binary/Two-spirit | 2 (0) |

| Not listed | 5 (1) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Straight (heterosexual) | 451 (90) |

| Lesbian/gay/bisexual/queer/questioning | 32 (6) |

| Asexual | 20 (4) |

| Not listed | 1 (0) |

| Indigenous * (n = 528) | 7 (1) |

| Race ** | |

| White | 425 (77) |

| East Asian | 40 (7) |

| Black | 27 (4) |

| South Asian/Indo-Caribbean | 18 (3) |

| Southeast Asian | 14 (3) |

| Latin American | 10 (2) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (1) |

| Indigenous | 3 (1) |

| Not listed | 15 (3) |

| Language translation preferred (n = 468) | 25 (5) |

| Highest level of education (n = 536) | |

| Less than high school | 15 (3) |

| Completed high school | 43 (8) |

| Trades certificate/diploma | 29 (5) |

| College/University | 449 (84) |

| Difficulty making ends meet (n = 475) | 73 (15) |

| Physical, mental or emotional functional limitations * | 373 |

| Disabilities * | 396 |

| Housing (n = 518) | |

| Own home | 385 (74) |

| Renting home | 113 (22) |

| Shelter/couch surfing | 7 (1) |

| Retirement home/long-term care | 3 (1) |

| Not listed | 10 (2) |

| Casual, short-term, temporary employment (n = 521) | 42 (8) |

| Available social support (n = 516) | 474 (92) |

| Covariate Comparisons | Race | Sexual Orientation | Finance | Housing | Employment | Social Support | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | |

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Not born in Canada vs. born in Canada | 2.11 (0.77–5.81) | 3.68 (0.81–16.65) | 0.65 (0.34–1.26) | 0.99 (0.33–2.98) | 1.20 (0.74–1.94) | 1.11 (0.53–2.31) | 1.00 (0.56–1.78) | 1.10 (0.42–2.84) | 0.93 (0.50–1.72) | 0.85 (0.32–2.29) | 0.81 (0.39–1.70) | 0.58 (0.17–1.99) |

| White vs. Visible Minority | 1.11 (0.40–3.13) | 2.87 (0.69–11.99) | 0.67 (0.29–1.54) | 0.27 (0.03–2.33) | 1.18 (0.70–2.00) | 1.25 (0.53–2.95) | 1.37 (0.75–2.50) | 1.66 (0.58–4.72) | 0.93 (0.45–1.94) | 1.17 (0.37–3.76) | 1.15 (0.50–2.64) | 1.29 (0.32–5.26) |

| Man vs. Woman vs. Non-Binary | 0.79 (0.35–1.78) 3.02 (0.34–26.86) | 0.45 (0.15–1.41) | 1.45 (0.79–2.68) | 1.18 (0.46–3.01) | 2.00 (1.26–3.19) 4.69 (0.75–29.10) | 2.31 (1.23–4.35) | 1.58 (0.92–2.71) 3.21 (0.32–32.06) | 1.42 (0.65–3.14) | 1.12 (0.62–2.02) | 0.93 (0.40–2.13) | 1.46 (0.72–2.96) 4.48 (0.47–42.80) | 0.76 (0.26–2.26) |

| Heterosexual vs. Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Queer/Questioning | 0.72 (0.17–3.17) | 0.50 (0.06–4.20) | 1.41 (0.47–4.22) | 2.13 (0.58–7.86) | 0.66 (0.29–1.52) | 0.54 (0.16–1.84) | 1.79 (0.82–3.89) | 2.62 (0.96–7.13) | 1.82 (0.80–4.14) | 2.35 (0.79–7.01) | 0.84 (0.25–2.86) | 1.18 (0.24–5.72) |

| ≤College/University vs. <College/University | 0.40 (0.09–1.74) | 0.36 (0.05–2.93) | 0.50 (0.18–1.45) | 1.32 (0.74–2.34) | 0.99 (0.41–2.36) | 1.14 (0.57–2.29) | 0.93 (0.30–2.84) | 1.15 (0.54–2.47) | 0.67 (0.19–2.38) | 1.82 (0.82–4.02) | 0.84 (0.18–3.94) | |

| Making Ends Meet vs. Difficulty Making Ends Meet | 1.15 (0.38–3.49) | 0.50 (0.15–1.69) | 0.52 (0.06–4.35) | 1.08 (0.52–2.24) | 0.94 (0.37–2.43) | 1.57 (0.72–3.44) | 1.01 (0.30–3.46) | 1.30 (0.52–3.29) | 1.58 (0.44–5.66) | 1.98 (0.76–5.19) | 1.05 (0.18–5.97) | |

| Own home vs. Rent/Retirement Home/Long-term care vs. Couch surfing/Shelter | 1.57 (0.63–3.96) 1.43 (0.18–11.45) | 1.45 (0.41–5.20) 4.21 (0.45–39.74) | 1.04 (0.48–2.28) 0.70 (0.09–5.42) | 0.86 (0.23–3.22) | 1.36 (0.80–2.33) 0.31 (0.04–2.38) | 1.08 (0.50–2.35) 0.58 (0.07–4.84) | 1.17 (0.58–2.33) 1.23 (0.27–5.56) | 0.57 (0.17–1.85) 1.99 (0.37–10.81) | 0.76 (0.33–1.79) 1.42 (0.31–6.46) | 0.26 (0.05–1.26) 1.76 (0.31–10.07) | 1.20 (0.49–2.90) 1.06 (0.13–8.41) | 0.62 (0.12–3.25) 1.76 (0.18–17.22) |

| Covariate Comparisons | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Not born in Canada vs. born in Canada | 0.71 (0.48–1.05) | 0.086 | 1.22 (0.70–2.11) | 0.49 |

| White vs. Visible Minority | 2.40 (1.56–3.68) | <0.001 | 2.63 (1.41–4.91) | 0.0023 |

| Man vs. Woman vs. Non-Binary | 2.11 (1.44–3.09) 3.37 (0.66–17.12) | <0.00 0.14 | 1.82 (1.15–2.86) | 0.0099 |

| Heterosexual vs. Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Queer/Questioning | 1.75 (1.00–3.06) | 0.051 | 1.94 (0.99–3.83) | 0.055 |

| ≤College/university vs. <College/University | 0.52 (0.30–0.91) | 0.022 | 0.66 (0.34–1.28) | 0.22 |

| Making Ends Meet vs. Difficulty Making Ends Meet | 1.91 (1.14–3.22) | 0.014 | 1.14 (0.58–2.28) | 0.7 |

| Own Home vs. Rent/Retirement home/Long-term care vs. Couch surfing/Shelter | 1.42 (0.91–2.22) 1.51 (0.54–4.26) | 0.13 0.43 | 0.92 (0.51–1.66) 1.23 (0.32–4.71) | 0.78 0.76 |

| Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Concerns about privacy and confidentiality | |

| Subtheme: Concerns about data security | “My only concerns would be: 1. Providing security against hackers. 2. Providing security against anyone accessing this information who is not authorized to do so. 3. Providing these information records to the patient if requested and having a process to correct any information that is wrong or misleading.” (P134) |

| Subtheme: Concerns about linking data to personal health record | “I support the anonymous collection of personal information however I would not want any of my answers to be tied to my identity.” (P113) |

| Subtheme: Concerns about data collection methods | “There is no privacy when hospital staff repeats personal information orally. There should be a screen they can show for patient to review and verify without everyone in the room hearing where you live and other personal info.” (P472) |

| Theme 2: Concerns about bias and discrimination | |

| Subtheme: Bias | “It may be perceived negatively by some staff who would be unconsciously biased regarding the client.” (P241) |

| Subtheme: Concern about mandated data collection | “There would need to be understanding for those who are not comfortable. Measures taken to help everyone believe it doesn’t harm them or their care.” (P629) |

| Theme 3: Lack of clarity about relevance to care | |

| Subtheme: Equity vs. equality | “The hospital needs only to know these topics for medical reasons. Race, age, and sex and emotional support structure affect health. Identifying these characteristics to ensure some equity for race, gender, or whatever is ridiculous. Equality of treatment is good. Equity in outcome is not attainable.” (P118) “This has nothing to do with the obligation of hospitals to provide the same healthcare irrespective of who you are, what you look like and whether you cuddle up to your cat, dog or partner at night. Who cares?” (P421) |

| Subtheme: Concerns about data use | “I don’t really see the need for an assessment of that level of detail. The submission of personal information should only be requested if clear purpose is provided. These broad questions don’t really help to understand why this information is needed and how it’ll be used. Without that clarity I would be uncomfortable.” (P629) |

| Theme 4: Accuracy and currency of information | |

| “Concern about possible data collection errors and outdated or changing information. I’d like to know if the data stored is ever changeable in terms of my beliefs which may change over time, my trust in the institution’s security, etc.” (P211) “Since this information will change continuously having it as part of a permanent record has little value with more possibility of damage.” (P15) | |

| Recommendations | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Establish a data stewardship council of diverse patient partners to provide oversight |

| 2 | Co-design data collection and use policies and procedures that prioritize patient needs |

| 3 | Clearly communicate who will access the data, for what purposes, for what duration, and the potential benefits and risks of data collection |

| 4 | Clearly explain each question, why it is being asked, and how the data will be used |

| 5 | Prioritize plain language to improve health literacy and resource accessibility |

| 6 | Minimize the potential for harm by ensuring that all staff involved in data collection and interpretation have been trained in culturally sensitive, anti-oppressive, trauma-informed practice |

| 7 | Provide supports and culturally appropriate services to help manage any potential harm from data collection |

| 8 | Establish protocols, processes, and infrastructure to protect patient privacy during data collection (e.g., in a private space, using secure online methods) and confidentiality during data storage and use (e.g., data security, authorized access) |

| 9 | Establish procedures to allow patients the opportunity to provide ongoing consent and the autonomy to update, revise or remove data |

| 10 | Mitigate bias in reporting based on false or missing data by identifying and addressing inaccuracies to ensure accurate and valid data. |

| 11 | Ensure data collection includes strategies to improve patient care and address patient social needs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bender, J.L.; Tong, E.; An, E.; Liu, Z.A.; Shapiro, G.K.; Avery, J.; Chu, A.; Schulz-Quach, C.; Hales, S.; Maybee, A.; et al. Collecting Data on the Social Determinants of Health to Advance Health Equity in Cancer Care in Canada: Patient and Community Perspectives. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070406

Bender JL, Tong E, An E, Liu ZA, Shapiro GK, Avery J, Chu A, Schulz-Quach C, Hales S, Maybee A, et al. Collecting Data on the Social Determinants of Health to Advance Health Equity in Cancer Care in Canada: Patient and Community Perspectives. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(7):406. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070406

Chicago/Turabian StyleBender, Jacqueline L., Eryn Tong, Ekaterina An, Zhihui Amy Liu, Gilla K. Shapiro, Jonathan Avery, Alanna Chu, Christian Schulz-Quach, Sarah Hales, Alies Maybee, and et al. 2025. "Collecting Data on the Social Determinants of Health to Advance Health Equity in Cancer Care in Canada: Patient and Community Perspectives" Current Oncology 32, no. 7: 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070406

APA StyleBender, J. L., Tong, E., An, E., Liu, Z. A., Shapiro, G. K., Avery, J., Chu, A., Schulz-Quach, C., Hales, S., Maybee, A., Sayani, A., Pinto, A., & Lofters, A. (2025). Collecting Data on the Social Determinants of Health to Advance Health Equity in Cancer Care in Canada: Patient and Community Perspectives. Current Oncology, 32(7), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070406