STAT2 Promotes Tumor Growth in Colorectal Cancer Independent of Type I IFN Receptor Signaling

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Survival Analysis

2.2. Cell Lines

2.3. Establishment of STAT2 and IFNAR1 Knockouts for Comparative Functional Studies

2.4. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.5. In Vivo Tumor Studies

2.6. Antibodies and Cytokines

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

2.8. RNA Extraction and qPCR Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. High STAT2 mRNA Expression Predicts Poor Survival in TCGA Colon Cancer Cohort

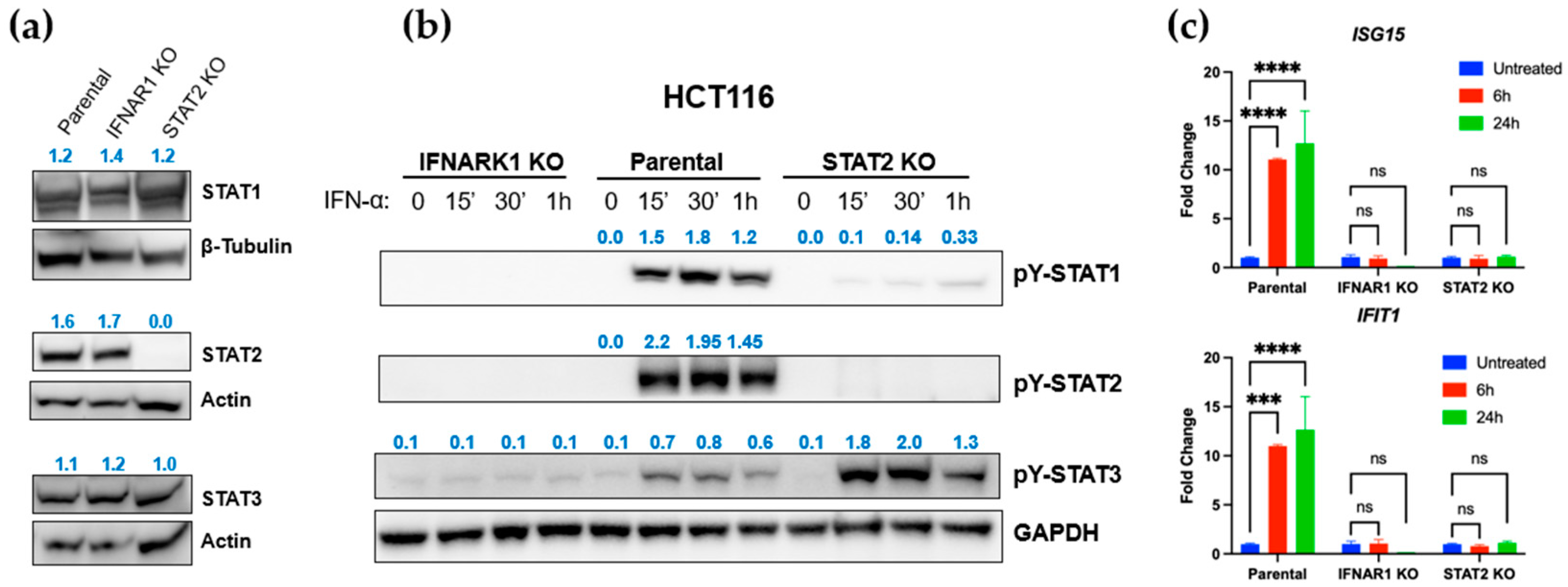

3.2. STAT2 and IFNAR1 Deletions Differentially Affect Downstream STAT Activation

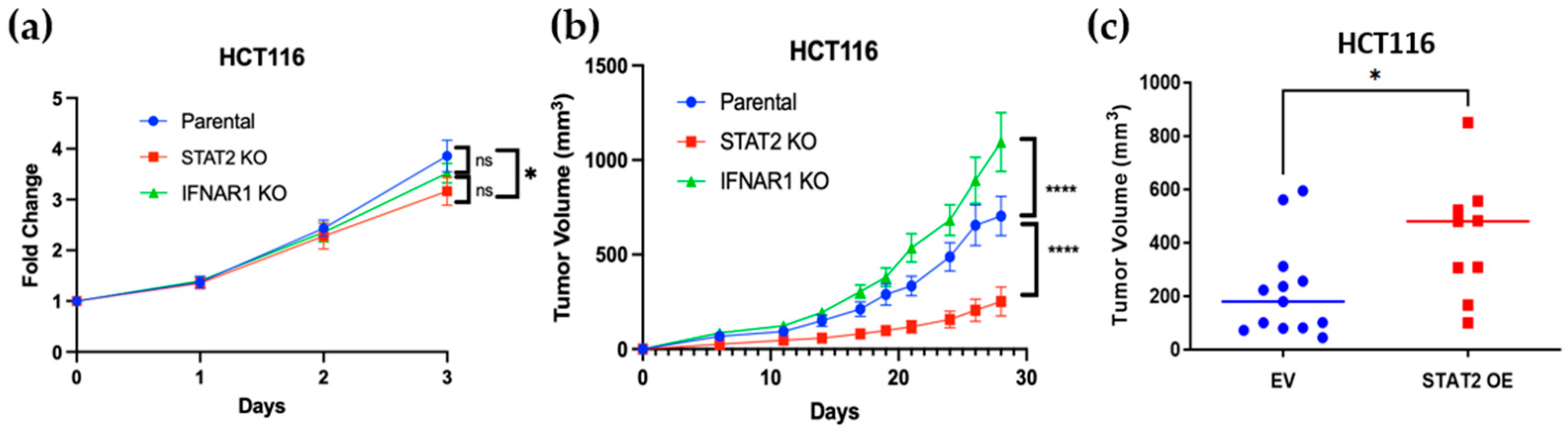

3.3. STAT2 and IFNAR1 Deletions Have Opposing Effects on Human Colon Cancer Cell Proliferation and Tumor Growth

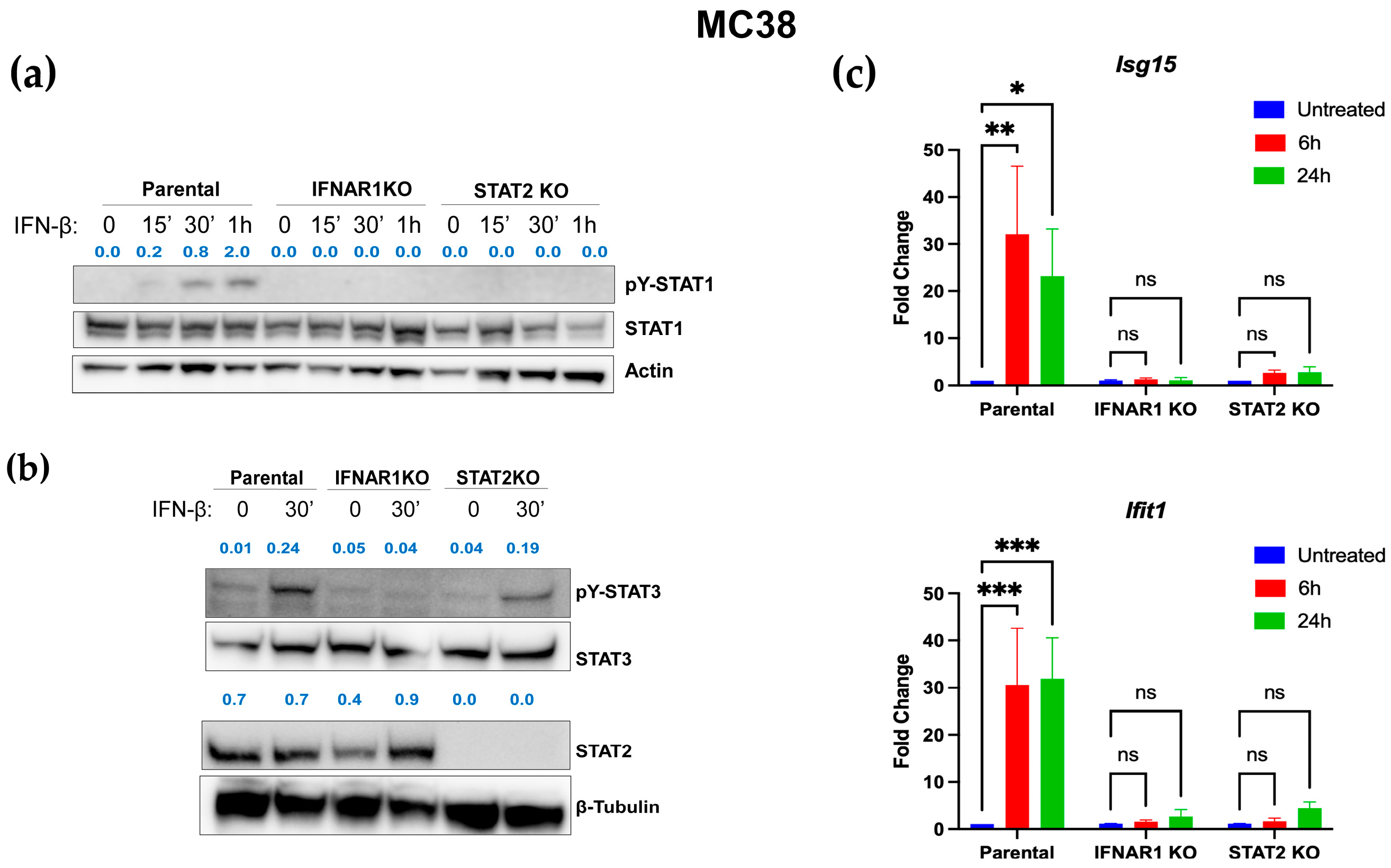

3.4. Distinct IFN-I Signaling Defects in STAT2- and IFNAR1-Deficient Murine Colon Carcinoma Cells

3.5. Reduced Proliferation and Tumorigenicity in STAT2-Deficient Murine Colon Cancer Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STAT2 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 |

| IFN | Interferon |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| COAD | Colon adenocarcinoma |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| IFNAR1 | Interferon receptor alpha chain (receptor 1) |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

Appendix A

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Ifit1 | TACAGGCTGGAGTGTGCTGAGA | CTCCACTTTCAGAGCCTTCGCA |

| Isg15 | GGTGTCCGTGACTAACTCCAT | TGGAAAGGGTAAGACCGTCCT |

| Gapdh | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

| ISG15 | GCCATGGGCTGGGACCT | TGATCTGCGCCTTCAGCTCT |

| IFIT1 | TGTCCAAGGTGGTAAAGGGTG | CCGGCGATTTAACTGATCCTG |

| GAPDH | CCAGGAAATGAGCTTCACAAAGT | CCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC |

References

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: From bench to clinic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, H.C.; Gamero, A.M. The role of signal transducer and activator of transcription-2 in the interferon response. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012, 32, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazewski, C.; Perez, R.E.; Fish, E.N.; Platanias, L.C. Type I Interferon (IFN)-Regulated Activation of Canonical and Non-Canonical Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 606456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holicek, P.; Guilbaud, E.; Klapp, V.; Truxova, I.; Spisek, R.; Galluzzi, L.; Fucikova, J. Type I interferon and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 321, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Taghi Khani, A.; Swaminathan, S. Type I interferons: One stone to concurrently kill two birds, viral infections and cancers. Curr. Res. Virol. Sci. 2021, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, H.; Wang, Y.; Wightman, S.M.; Jackson, M.W.; Stark, G.R. How cancer cells make and respond to interferon-I. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S.A.; Audsley, K.M.; Newnes, H.V.; Fernandez, S.; de Jong, E.; Waithman, J.; Foley, B. Type I interferon subtypes differentially activate the anti-leukaemic function of natural killer cells. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1050718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busselaar, J.; Sijbranda, M.; Borst, J. The importance of type I interferon in orchestrating the cytotoxic T-cell response to cancer. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 270, 106938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.B.; Kacha, A.K.; Kline, J.; Woo, S.-R.; Kranz, D.M.; Murphy, K.M.; Gajewski, T.F. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8α+ dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 2005–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katlinski, K.V.; Gui, J.; Katlinskaya, Y.V.; Ortiz, A.; Chakraborty, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Carbone, C.J.; Beiting, D.P.; Girondo, M.A.; Peck, A.R.; et al. Inactivation of Interferon Receptor Promotes the Establishment of Immune Privileged Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aricò, E.; Castiello, L.; Capone, I.; Gabriele, L.; Belardelli, F. Type I Interferons and Cancer: An Evolving Story Demanding Novel Clinical Applications. Cancers 2019, 11, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Donnelly, C.R.; Heath, B.R.; Bellile, E.; Donnelly, L.A.; Taner, H.F.; Broses, L.; Brenner, J.C.; Chinn, S.B.; Ji, R.-R.; et al. Cancer-specific type-I interferon receptor signaling promotes cancer stemness and effector CD8+ T-cell exhaustion. OncoImmunology 2021, 10, 1997385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Teo, J.M.N.; Yau, S.W.; Wong, M.Y.; Lok, C.N.; Che, C.M.; Javed, A.; Huang, Y.; Ma, S.; Ling, G.S. Chronic type I interferon signaling promotes lipid-peroxidation-driven terminal CD8(+) T cell exhaustion and curtails anti-PD-1 efficacy. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, A.M.; Young, M.R.; Mentor-Marcel, R.; Bobe, G.; Scarzello, A.J.; Wise, J.; Colburn, N.H. STAT2 contributes to promotion of colorectal and skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010, 3, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, M.T.; Hracsko, Z.; Becker, C.; Neurath, M.F. STAT2 Controls Colorectal Tumorigenesis and Resistance to Anti-Cancer Drugs. Cancers 2023, 15, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-J.; An, H.-J.; Kim, S.-M.; Yoo, S.-M.; Park, J.; Lee, G.-E.; Kim, W.-Y.; Kim, D.J.; Kang, H.C.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. FBXW7-mediated stability regulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 in melanoma formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Lu, Y. High expression of STAT2 in ovarian cancer and its effect on metastasis of ovarian cancer cells. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2020, 40, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, K.; Su, F. Expression profile and prognostic values of STAT family members in non-small cell lung cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 4866–4880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Dai, H.Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.L.; Hu, H. Signal transducer and activator of transcription family is a prognostic marker associated with immune infiltration in endometrial cancer. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, W.; Zuo, L.; Xu, M.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; et al. The Fibrillin-1/VEGFR2/STAT2 signaling axis promotes chemoresistance via modulating glycolysis and angiogenesis in ovarian cancer organoids and cells. Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Qiao, L.; Jin, L.; Chen, Y.; Wen, X.; Wang, H. OGT-regulated O-GlcNAcylation promotes the malignancy of colorectal cancer by activating STAT2 to induce macrophage M2: OGT protein macromolecule action. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 144057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Fang, Y.; Chang, L.; Bian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pu, J.; Wang, K. STAT2-induced linc02231 promotes tumorigenesis and angiogenesis through modulation of hnRNPA1/ANGPTL4 in colorectal cancer. J. Gene Med. 2023, 25, e3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogony, J.; Choi, H.J.; Lui, A.; Cristofanilli, M.; Lewis-Wambi, J. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1) overexpression enhances the aggressive phenotype of SUM149 inflammatory breast cancer cells in a signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 (STAT2)-dependent manner. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Greten, F.R. The inflammatory pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, D.; Shen, M. Tumor Microenvironment Shapes Colorectal Cancer Progression, Metastasis, and Treatment Responses. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 869010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, A.P.; Ferretti, V.; Agrawal, S.; An, M.; Angelakos, J.C.; Arya, R.; Bajari, R.; Baqar, B.; Barnowski, J.H.B.; Burt, J.; et al. The NCI Genomic Data Commons. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Bashel, B.; Balasubramanya, S.A.H.; Creighton, C.J.; Ponce-Rodriguez, I.; Chakravarthi, B.; Varambally, S. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.L.; Ferreira, L.M.; Alvarez-Moya, B.; Buttiglione, V.; Ferrini, B.; Zordan, P.; Monestiroli, A.; Fagioli, C.; Bezzecchi, E.; Scotti, G.M.; et al. Continuous sensing of IFNalpha by hepatic endothelial cells shapes a vascular antimetastatic barrier. Elife 2022, 11, e80690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Xu, J.; Tan Estioko, M.D.; Kotredes, K.P.; Lopez-Otalora, Y.; Hilliard, B.A.; Baker, D.P.; Gallucci, S.; Gamero, A.M. Host STAT2/type I interferon axis controls tumor growth. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spandidos, A.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Seed, B. PrimerBank: A resource of human and mouse PCR primer pairs for gene expression detection and quantification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, D792–D799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.C.; Kotredes, K.P.; Cremers, T.; Patel, S.; Afanassiev, A.; Slifker, M.; Gallucci, S.; Gamero, A.M. Targeted Stat2 deletion in conventional dendritic cells impairs CTL responses but does not affect antibody production. Oncoimmunology 2020, 10, 1860477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Klement, J.D.; Ibrahim, M.L.; Xiao, W.; Redd, P.S.; Nayak-Kapoor, A.; Zhou, G.; Liu, K. Type I interferon suppresses tumor growth through activating the STAT3-granzyme B pathway in tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-C.; Fan, C.-W.; Tseng, W.-K.; Chein, H.-P.; Hsieh, T.-Y.; Chen, J.-R.; Hwang, C.-C.; Hua, C.-C. IFNAR1 Is a Predictor for Overall Survival in Colorectal Cancer and Its mRNA Expression Correlated with IRF7 but Not TLR9. Medicine 2014, 93, e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katlinskaya, Y.V.; Carbone, C.J.; Yu, Q.; Fuchs, S.Y. Type 1 interferons contribute to the clearance of senescent cell. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2015, 16, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, M.A.; Gilardini Montani, M.S.; Benedetti, R.; Santarelli, R.; D’Orazi, G.; Cirone, M. STAT3 and mutp53 Engage a Positive Feedback Loop Involving HSP90 and the Mevalonate Pathway. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz-Heddergott, R.; Stark, N.; Edmunds, S.J.; Li, J.; Conradi, L.-C.; Bohnenberger, H.; Ceteci, F.; Greten, F.R.; Dobbelstein, M.; Moll, U.M. Therapeutic Ablation of Gain-of-Function Mutant p53 in Colorectal Cancer Inhibits Stat3-Mediated Tumor Growth and Invasion. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 298–314.e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Lee, D.-S.; Jeon, M.-S.; Kwon, S.W.; Song, S.U. Gene expression profile reveals that STAT2 is involved in the immunosuppressive function of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Gene 2012, 497, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, D.; Shao, Y.; Shan, Z.; Liu, Q.; Weng, J.; He, W.; Zhang, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; et al. circCAPRIN1 interacts with STAT2 to promote tumor progression and lipid synthesis via upregulating ACC1 expression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Commun. 2023, 43, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.; Pelzel, C.; Begitt, A.; Mee, M.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Scott, D.J.; Vinkemeier, U. STAT2 Is a Pervasive Cytokine Regulator due to Its Inhibition of STAT1 in Multiple Signaling Pathways. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e2000117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, K. Unraveling the complexity of STAT3 in cancer: Molecular understanding and drug discovery. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargalionis, A.N.; Papavassiliou, K.A.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Targeting STAT3 Signaling Pathway in Colorectal Cancer. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Luo, S.-N.; Dong, L.; Liu, T.-T.; Shen, X.-Z.; Zhang, N.-P.; Liang, L. Interferon regulatory factor family influences tumor immunity and prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; He, L.; Regev, A.; Struhl, K. Inflammatory regulatory network mediated by the joint action of NF-kB, STAT3, and AP-1 factors is involved in many human cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9453–9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Stark, G.R. IRF9 and unphosphorylated STAT2 cooperate with NF-kappaB to drive IL6 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 3906–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosenko, I.; Fryknas, M.; Forsberg, S.; Johnsson, P.; Cheon, H.; Holvey-Bates, E.G.; Edsbacker, E.; Pellegrini, P.; Rassoolzadeh, H.; Brnjic, S.; et al. Cell crowding induces interferon regulatory factor 9, which confers resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E51–E61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Fu, Z.; Gao, L.; Zeng, J.; Xiang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Tong, X.; Wang, X.-Q.; Lu, J. Increased IRF9–STAT2 Signaling Leads to Adaptive Resistance toward Targeted Therapy in Melanoma by Restraining GSDME-Dependent Pyroptosis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 2476–2487.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazawi, W.; Heath, H.; Waters, J.A.; Woodfin, A.; O’Brien, A.J.; Scarzello, A.J.; Ma, B.; Lopez-Otalora, Y.; Jacobs, M.; Petts, G.; et al. Stat2 loss leads to cytokine-independent, cell-mediated lethality in LPS-induced sepsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8656–8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, C.; Martin-Fernandez, M.; Ailal, F.; Qiu, X.; Taft, J.; Altman, J.; Rosain, J.; Buta, S.; Bousfiha, A.; Casanova, J.L.; et al. Homozygous STAT2 gain-of-function mutation by loss of USP18 activity in a patient with type I interferonopathy. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20192319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Badonyi, M.; Franklin, L.; Seabra, L.; Rice, G.I.; Anne Boland, A.; Deleuze, J.-F.; El-Chehadeh, S.; Anheim, M.; de Saint-Martin, A.; et al. Type I Interferonopathy due to a Homozygous Loss-of-Inhibitory Function Mutation in STAT2. J. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 43, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucciol, G.; Moens, L.; Ogishi, M.; Rinchai, D.; Matuozzo, D.; Momenilandi, M.; Kerrouche, N.; Cale, C.M.; Treffeisen, E.R.; Al Salamah, M.; et al. Human inherited complete STAT2 deficiency underlies inflammatory viral diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e168321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canar, J.; Bono, M.; Alvarado, A.; Slifker, M.; Sitia, G.; Gamero, A.M. STAT2 Promotes Tumor Growth in Colorectal Cancer Independent of Type I IFN Receptor Signaling. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120707

Canar J, Bono M, Alvarado A, Slifker M, Sitia G, Gamero AM. STAT2 Promotes Tumor Growth in Colorectal Cancer Independent of Type I IFN Receptor Signaling. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):707. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120707

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanar, Jorge, Madeline Bono, Amy Alvarado, Michael Slifker, Giovanni Sitia, and Ana M. Gamero. 2025. "STAT2 Promotes Tumor Growth in Colorectal Cancer Independent of Type I IFN Receptor Signaling" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120707

APA StyleCanar, J., Bono, M., Alvarado, A., Slifker, M., Sitia, G., & Gamero, A. M. (2025). STAT2 Promotes Tumor Growth in Colorectal Cancer Independent of Type I IFN Receptor Signaling. Current Oncology, 32(12), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120707