Diabetes, Obesity, and Endometrial Cancer: A Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Classification of EC

1.2. Pathophysiology of EC

1.3. Diagnosis of EC

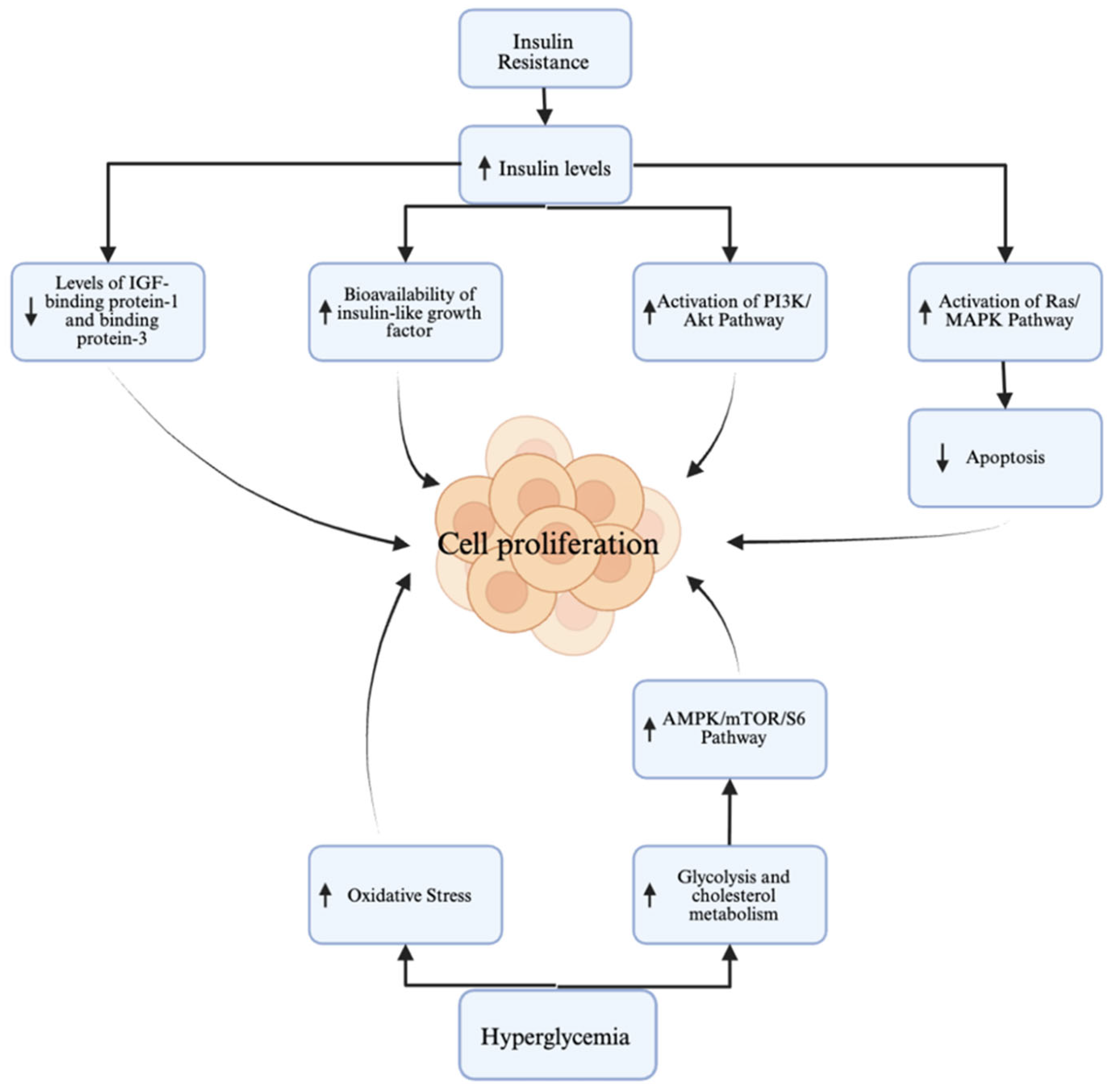

2. Overview of Diabetes in EC

2.1. Diabetes as a Risk Factor

2.2. Diabetes as a Prognostic Factor

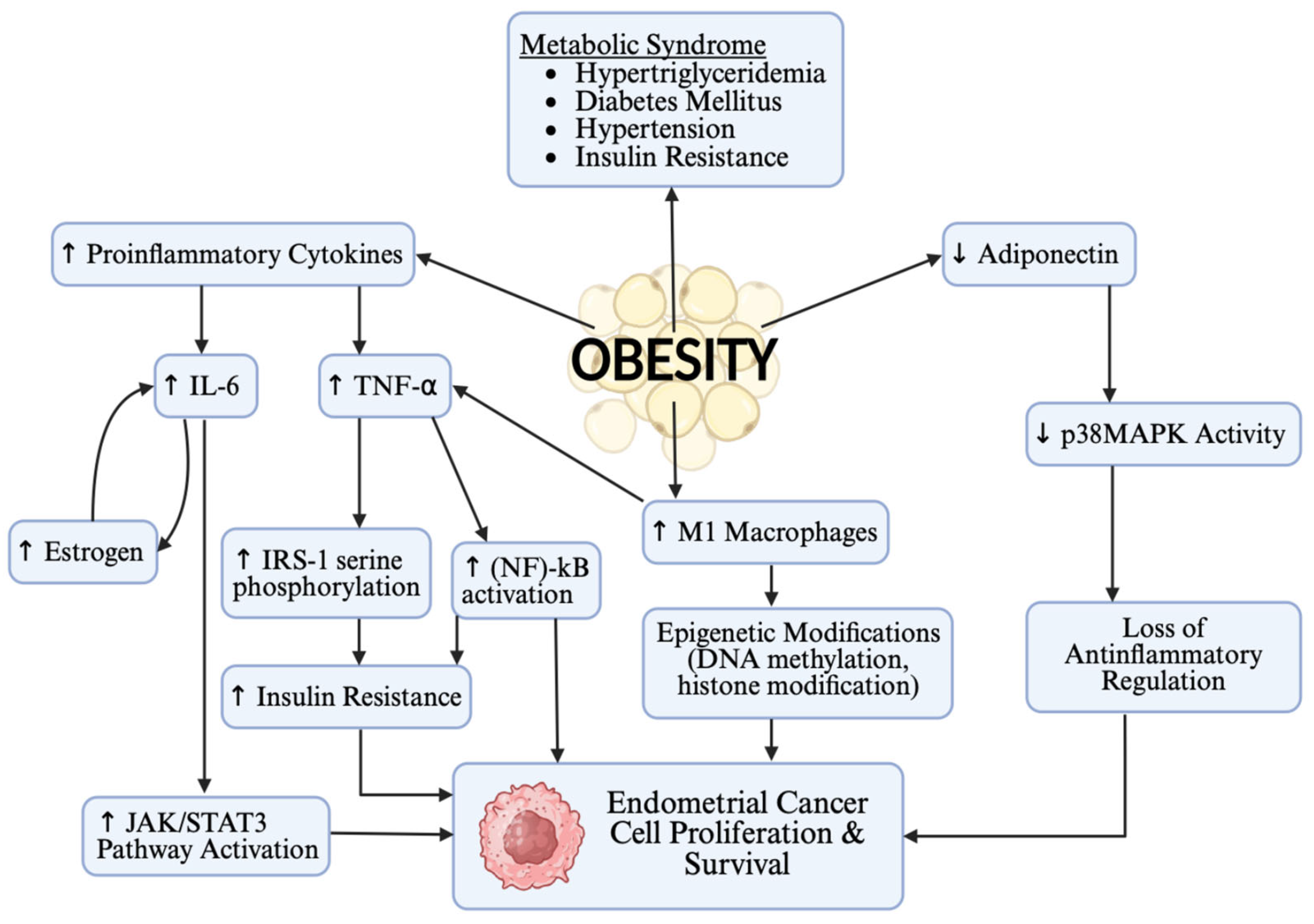

3. Overview of Obesity in EC

3.1. Obesity as a Risk Factor

3.2. Obesity as a Prognostic Factor

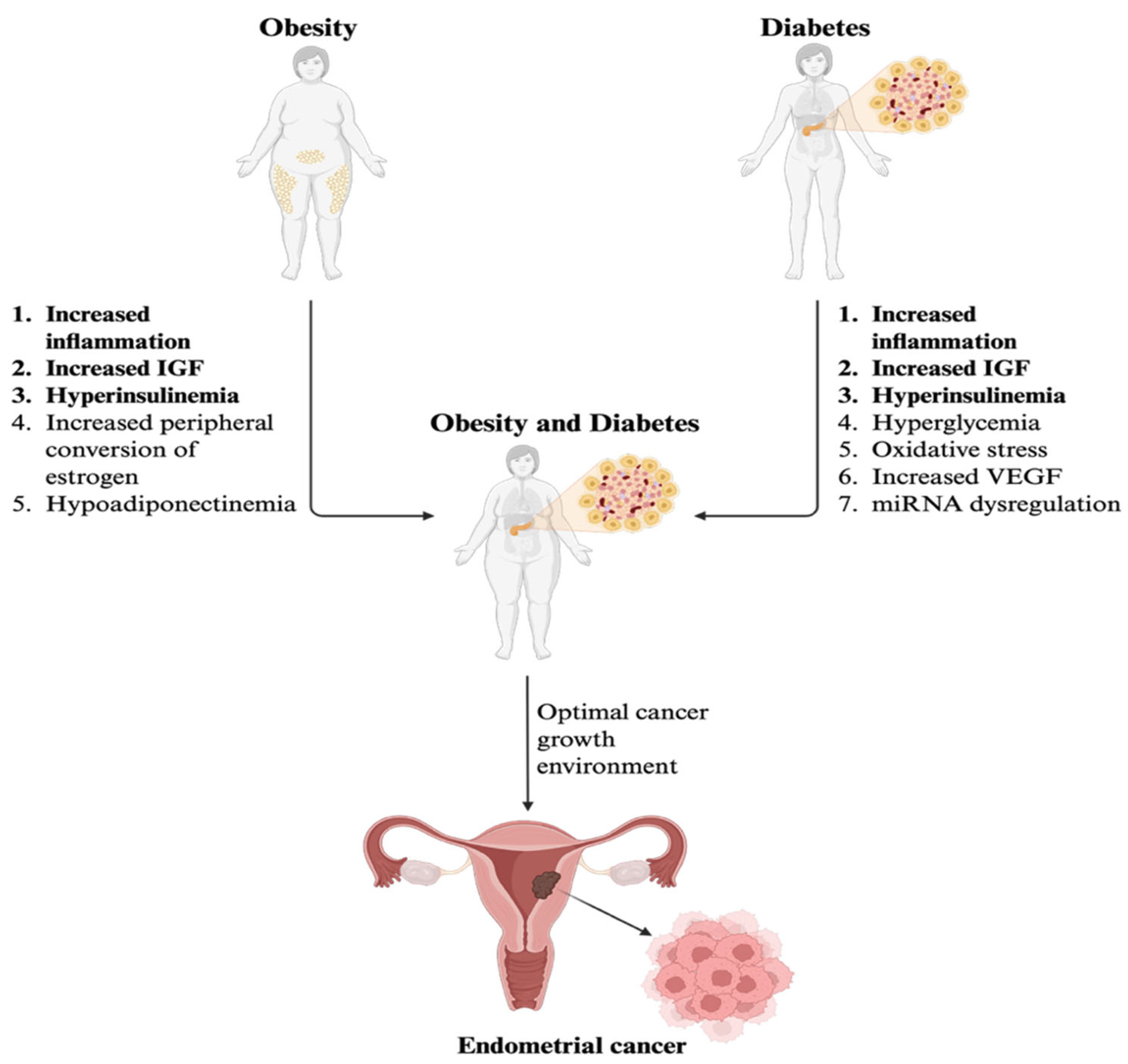

4. Overview of Diabetes and Obesity as Comorbidities in EC

| References | Primary Findings |

|---|---|

| Baker-Rand [3] | Co-morbidities increase surgical candidacy limitations and post-operation and treatment-related complications. |

| Travaglino [13] | Meta-analysis of six studies identified 3132 endometrial cancer cases, a RR of 1.89 for those with obesity, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. |

| Lucenteforte [29] | Two case–control studies with 777 cases of EC and 1550 controls (OR for diabetes only = 1.4, diabetes + obesity = 5.1) |

| Friedenreich [32] | In those with obesity, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, an OR of 1.53 was identified for EC. |

| Friberg [54] | Risk of developing EC: Diabetes alone increases the risk by 2-fold, diabetes combined with obesity by 6.5-fold, and diabetes combined with obesity and physical inactivity by 9.5-fold. |

| Nagle [57] | Hazard ratio for EC-specific mortality in patients with diabetes and obesity was 2.65 [95% CI 1.60–4.40] |

| Qiang [58] | Diabetes and obesity led to a higher risk of anesthesia-related complications and respiratory distress perioperatively. |

| Bouwman [59] | Morbidly obese patients were at the highest risk of wound infections and antibiotic use in open EC surgery. |

| Yin [60] | Patients with diabetes and obesity had an increased length of hospital stay (6.2 days vs. 4.5 days, p < 0.03) and a higher incidence of venous thromboembolic events (p < 0.01) compared to the control group. |

5. Treatment Considerations in EC

6. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Endometrial Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/endometrial-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Rand, H.; Kitson, S.J. Recent advances in endometrial cancer prevention, early diagnosis and treatment. Cancers 2024, 16, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund. Endometrial Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/endometrial-cancer-statistics/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Uterine Corpus Cancer Statistics. 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2025/2025-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Bokhman, J.V. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 1983, 15, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, R.; Soslow, R.A.; Weigelt, B. Classification of endometrial carcinoma: More than two types. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e268–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Yendluri, V.; Wenham, R.M. The molecular biology of endometrial cancers and the implications for pathogenesis, classification, and targeted therapies. Cancer Control 2009, 16, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzic, M.; Aimagambetova, G.; Kunz, J.; Bapayeva, G.; Aitbayeva, B.; Terzic, S.; Laganà, A.S. Molecular basis of endometriosis and endometrial cancer: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.; The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013, 497, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhouk, A.; McConechy, M.K.; Leung, S.; Yang, W.; Lum, A.; Senz, J.; Boyd, N.; Pike, J.; Anglesio, M.; Kwon, J.K.; et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: A simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer 2017, 123, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travaglino, A.; Raffone, A.; Stradella, C.; Esposito, R.; Moretta, P.; Gallo, C.; Orlandi, G.; Insabato, L.; Zullo, F. Impact of endometrial carcinoma histotype on the prognostic value of the TCGA molecular subgroups. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berek, J.S.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Creutzberg, C.; Fotopoulou, C.; Gaffney, D.; Kehoe, S.; Lindemann, K.; Mutch, D.; Concin, N.; Endometrial Cancer Staging Subcommittee; et al. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 162, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 149: Endometrial cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 1006–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giardiello, F.M.; I Allen, J.; E Axilbund, J.; Boland, R.C.; A Burke, C.; Burt, R.W.; Church, J.M.; A Dominitz, J.; A Johnson, D.; Kaltenbach, T.; et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: A consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1159–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, Y.M.; Wagner, A.; Morreau, H.; Menko, F.; Stormorken, A.; Quehenberger, F.; Sandkuijl, L.; Møller, P.; Genuardi, M.; van Houwelingen, H.; et al. Cancer risk in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer due to MSH6 mutations: Impact on counseling and surveillance. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.H.; Mester, J.L.; Ngeow, J.; Rybicki, L.A.; Orloff, M.S.; Eng, C. Lifetime cancer risks in individuals with germline PTEN mutations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 734 Summary: The role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 945–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, E.J.; Kitson, S.J.; McAlpine, J.N.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Powell, M.E.; Singh, N. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 2022, 399, 1412–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.; Clarke, M.A.; Morillo, A.D.M.; Wentzensen, N.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N. Ultrasound detection of endometrial cancer in women with postmenopausal bleeding: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 157, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, N.H.; Shaw, J.E.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; da Rocha Fernandes, J.D.; Ohlrogge, A.W.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 138, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, A.H.; Stedman, M.; Davies, M.; Livingston, M.; Alshames, R.; Lunt, M.; Rayman, G.; Gadsby, R. Estimating life years lost to diabetes: Outcomes from analysis of National Diabetes Audit and Office of National Statistics data. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 9, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, K.M.; Boyle, J.P.; Thompson, T.J.; Sorensen, S.W.; Williamson, D.F. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA 2003, 290, 1884–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabuliene, L.; Kaceniene, A.; Steponaviciene, L.; Linkeviciute-Ulinskiene, D.; Stukas, R.; Arlauskas, R.; Vanseviciute-Petkeviciene, R.; Smailyte, G. Risk of endometrial cancer in women with diabetes: A population-based retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, V.M.; Newcomb, P.A.; Trentham-Dietz, A.; Hampton, J.M. Obesity, diabetes, and other factors in relation to survival after endometrial cancer diagnosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2007, 17, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamani, M.; Stuart, C.A. Specific binding and growth-promoting activity of insulin in endometrial cancer cells in culture. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 179, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H.; Wysham, W.Z.; Roque, D.R.; Willson, A.K.; Sheng, X.; Zhou, C.; Bae-Jump, V.L. Glucose promotes cell proliferation, glucose uptake and invasion in endometrial cancer cells via AMPK/mTOR/S6 and MAPK signaling. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 138, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucenteforte, E.; Bosetti, C.; Talamini, R.; Montella, M.; Zucchetto, A.; Pelucchi, C.; Franceschi, S.; Negri, E.; Levi, F.; La Vecchia, C. Diabetes and endometrial cancer: Effect modification by body weight, physical activity and hypertension. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 97, 995–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.V.; Pasupuleti, V.; Benites-Zapata, V.A.; Thota, P.; Deshpande, A.; Perez-Lopez, F.R. Insulin resistance and endometrial cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 2747–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Sun, C. Association of abnormal glucose metabolism and insulin resistance in patients with atypical and typical endometrial cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 2173–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenreich, C.M.; Morielli, A.R.; Lategan, I.; Ryder-Burbidge, C.; Yang, L. Physical activity and breast cancer survival-epidemiologic evidence and potential biologic mechanisms. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 717–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fader, A.N.; Arriba, L.N.; Frasure, H.E.; von Gruenigen, V.E. Endometrial cancer and obesity: Epidemiology, biomarkers, prevention and survivorship. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 114, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, M.J.; Hoover, D.R.; Yu, H.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Manson, J.E.; Li, J.; Harris, T.G.; Rohan, T.E.; Xue, X.; Ho, G.Y.F.; et al. A prospective evaluation of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I as risk factors for endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008, 17, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nead, K.T.; Sharp, S.J.; Thompson, D.J.; Painter, J.N.; Savage, D.B.; Semple, R.K.; Barker, A.; Australian National Endometrial Cancer Study Group (ANECS); Perry, J.R.; Attia, J.; et al. Evidence of a causal association between insulinemia and endometrial cancer: A Mendelian randomization analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morielli, A.R.; Kokts-Porietis, R.L.; Benham, J.L.; McNeil, J.; Cook, L.S.; Courneya, K.S.; Friedenreich, C.M. Associations of insulin resistance and inflammatory biomarkers with endometrial cancer survival: The Alberta endometrial cancer cohort study. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 1701–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVicker, L.; Cardwell, C.R.; Edge, L.; McCluggage, W.G.; Quinn, D.; Wylie, J.; McMenamin, Ú.C. Survival outcomes in endometrial cancer patients according to diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Lopez, F.R.; Pasupuleti, V.; Gianuzzi, X.; Palma-Ardiles, G.; Hernandez-Fernandez, W.; Hernandez, A.V. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of metformin treatment on overall mortality rates in women with endometrial cancer and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Maturitas 2017, 101, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, K.; Cvancarova, M.; Eskild, A. Body mass index, diabetes and survival after diagnosis of endometrial cancer: A report from the HUNT-Survey. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achara, K.E.; Iyayi, I.R.; Erinne, O.C.; Odutola, O.D.; Ogbebor, U.P.; Utulor, S.N.; Abiodun, R.F.; Perera, G.S.; Okoh, P.; Okobi, O.E. Trends and patterns in obesity-related deaths in the US (2010–2020): A comprehensive analysis using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) Data. Cureus 2024, 16, e68376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, E.E.; Rodriguez, C.; Walker-Thurmond, K.; Thun, M.J. Overweight, Obesity, and Mortality from Cancer in a Prospectively Studied Cohort of U.S. Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K.K. Obesity as a risk factor for certain types of cancer. Lipids 1998, 33, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, A.; Ryan, K.J. Aromatization of androgens by human abdominal and breast fat tissue. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1975, 40, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, J. The role of metabolic syndrome in endometrial cancer: A review. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalliala, I.; Markozannes, G.; Gunter, M.J.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Gabra, H.; Mitra, A.; Terzidou, A.; Bennett, P.; Martin-Hirsch, P.; Tsilidis, K.K.; et al. Obesity and gynaecological and obstetric conditions: Umbrella review of the literature. BMJ 2017, 359, j4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omiyale, W.; Allen, N.E.; Sweetland, S. Body size, body composition and endometrial cancer risk among postmenopausal women in UK Biobank. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wu, W.; Cheng, X.; Chen, X.; Ren, F. Association between metabolic disorders and clinicopathologic features in endometrial cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1351982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Xue, Y.; Xu, Z.; Guan, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Ren, Y. Deep cervical stromal invasion predicts poor prognosis in patients with stage II endometrioid endometrial cancer: A two-centered retrospective study. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1450054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clontz, A.D.; Gan, E.; Hursting, S.D.; Bae-Jump, V.L. Effects of weight loss on key obesity-related biomarkers linked to the risk of endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers 2024, 16, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, A.; MacKintosh, M.L.; Derbyshire, A.E.; Tsakiroglou, A.-M.; Walker, T.D.J.; McVey, R.J.; Bolton, J.; Fergie, M.; Bagley, S.; Ashton, G.; et al. The impact of obesity and bariatric surgery on the immune microenvironment of the endometrium. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 46, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.K.; Roncancio, A.M.; Shah, N.R.; Davis, M.-A.; Saenz, C.C.; McHale, M.T.; Plaxe, S.C. Bariatric surgery decreases the risk of uterine malignancy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 133, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; Yamagami, W. Immunotherapy for endometrial cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 30, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Banoy, N.; Ortiz, E.J.; Jiang, C.S.; Dagher, C.; Sevilla, C.; Girshman, J.; Pagano, A.M.; Plodkowski, A.J.; Zammarrelli, W.A.; Mueller, J.J.; et al. Body mass index and adiposity influence responses to immune checkpoint inhibition in endometrial cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2024, 134, e180516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, E.; Orsini, N.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Wolk, A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of endometrial cancer: A meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Martínez, E.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.C.; Lira-Lira, G.G.; Ríos, P.E.-D.L.; Salmerón-Castro, J.; Larrea, F.; Hernández-Avila, M. Case–control study of diabetes, obesity, physical activity and risk of endometrial cancer among Mexican women. Cancer Causes Control 2000, 11, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Dai, Y. Metabolic reprogramming and interventions in endometrial carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagle, C.; Crosbie, E.; Brand, A.; Obermair, A.; Oehler, M.; Quinn, M.; Leung, Y.; Spurdle, A.; Webb, P. The association between diabetes, comorbidities, body mass index and all-cause and cause-specific mortality among women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 150, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, J.K.; Lipscombe, L.L.; Lega, I.C. Association between diabetes, obesity, aging, and cancer: Review of recent literature. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 5743–5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, F.; Smits, A.; Lopes, A.; Das, N.; Pollard, A.; Massuger, L.; Bekkers, R.; Galaal, K. The impact of BMI on surgical complications and outcomes in endometrial cancer surgery—An institutional study and systematic review of the literature. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.H.; Jia, H.Y.; Xue, X.R.; Yang, S.Z.; Wang, Z.Q. Clinical analysis of endometrial cancer patients with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 736–743. [Google Scholar]

- Legge, F.; Restaino, S.; Leone, L.; Carone, V.; Ronsini, C.; Di Fiore, G.L.M.; Pasciuto, T.; Pelligra, S.; Ciccarone, F.; Scambia, G.; et al. Clinical outcome of recurrent endometrial cancer: Analysis of post-relapse survival by pattern of recurrence and secondary treatment. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegenthaler, F.; Lindemann, K.; Epstein, E.; Rau, T.; Nastic, D.; Ghaderi, M.; Rydberg, F.; Mueller, M.D.; Carlson, J.; Imboden, S. Time to first recurrence, pattern of recurrence, and survival after recurrence in endometrial cancer according to the molecular classification. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 165, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morice, P.; Leary, A.; Creutzberg, C.; Abu-Rustum, N.; Darai, E. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 2016, 387, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodolakis, A.; Scambia, G.; Planchamp, F.; Acien, M.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Farrugia, M.; Grynberg, M.; Pakiz, M.; Pavlakis, K.; Vermeulen, N.; et al. ESGO/ESHRE/ESGE Guidelines for the fertility-sparing treatment of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2023, 2023, hoac057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.; Johnson, N.; Kitchener, H.C.; Lawrie, T.A. Adjuvant radiotherapy for stage I endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, Cd003916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sovak, M.A.; Hensley, M.L.; Dupont, J.; Ishill, N.; Alektiar, K.M.; Abu-Rustum, N.; Barakat, R.; Chi, D.S.; Sabbatini, P.; Spriggs, D.R.; et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin in the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk stage III and IV endometrial cancer: A retrospective study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2006, 103, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidaka, T.; Nakamura, T.; Shima, T.; Yuki, H.; Saito, S. Paclitaxel/carboplatin versus cyclophosphamide/ adriamycin/ cisplatin as postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced endometrial adenocarcinoma. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2006, 32, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anca-Stanciu, M.-B.; Manu, A.; Olinca, M.V.; Coroleucă, C.; Comandașu, D.-E.; Coroleuca, C.A.; Maier, C.; Bratila, E. Comprehensive Review of Endometrial Cancer: New Molecular and FIGO Classification and Recent Treatment Changes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.R.; Chase, D.M.; Slomovitz, B.M.; Christensen, R.D.; Novák, Z.; Black, D.; Gilbert, L.; Sharma, S.; Valabrega, G.; Landrum, L.M.; et al. Dostarlimab for primary advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muley, A. Keytruda Receives 40th FDA Approval; Cancer Research Institute: New York City, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hooks, O.; Jhumkhawala, V.; Sibson, K.; Shrontz, A.; Krishnan, S.S.; Ahmad, S. Diabetes, Obesity, and Endometrial Cancer: A Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120672

Hooks O, Jhumkhawala V, Sibson K, Shrontz A, Krishnan SS, Ahmad S. Diabetes, Obesity, and Endometrial Cancer: A Review. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):672. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120672

Chicago/Turabian StyleHooks, Olivia, Vama Jhumkhawala, Kristen Sibson, Abbigail Shrontz, Syamala Soumya Krishnan, and Sarfraz Ahmad. 2025. "Diabetes, Obesity, and Endometrial Cancer: A Review" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120672

APA StyleHooks, O., Jhumkhawala, V., Sibson, K., Shrontz, A., Krishnan, S. S., & Ahmad, S. (2025). Diabetes, Obesity, and Endometrial Cancer: A Review. Current Oncology, 32(12), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120672