Contextualizing Measurement: Establishing a Construct and Content Foundation for the Assessment of Cancer-Related Dyadic Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. General Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Eligibility

3. Step 1: Materials and Methods for Construct and Content Domain Development

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Step 1: Results

4.1. Construct Development

4.1.1. Multidimensional

My partner was able to take me [to medical appointments] at whatever hour, pick me up, but was not emotionally able to sit with me. He did what he could do which was physical stuff but he’s not capable of the emotional involvement.(woman with multiple myeloma)

We have a rule that if it’s a diagnosis or a test result and it’s heavy, we’re always together. Always together. Every appointment together. The diagnosis, we were together, everything was together. And we’re just a ‘together couple’.(woman with breast cancer)

4.1.2. Consistent with Established Relational Functioning

I don’t talk about it with my husband because I don’t want to worry him but I’m also that kind of person that I keep a lot of things to myself anyways. So, I think how couples cope with this, it’s important to look at what the baseline relationship is like because I think that makes a difference in how they’re going to cope with this situation.(woman with breast cancer)

4.1.3. Distinct from Self-Efficacy

And I just said that if I had to worry about his emotions, then I’m not going to be able to deal with it. You know, if you cry, you cry for 5 minutes by yourself, but if you cry and you see someone else cry, it’s just back and forth… it’s never going to stop. So that’s why to me, I kind of had to [go alone]. Let me get through my thing, take the shot and then by the time I’m with him… I’ve pulled myself together. But if we had done it together, I think it would’ve been too hard for me.(woman with breast cancer)

4.2. Content Development

4.2.1. Illness Intrusions

Domain 1: Patients’ Physical Experience

Domain 2: Social Life

The cancer and all the treatment that goes around has a big impact on social life. I didn’t go out for 8 months… hardly. It was tough on my husband too, but I always encouraged him to meet up with the guys and put some pressure on his friends to take him out so that he can have a good time and kind of not be around thinking about the situation and the cancer.(woman with breast cancer)

Domain 3: Couple Life

I don’t think [he] realizes how it is really. It’s like I’m dead, you know. We have sex once a month, we used to have sex three, four times a week, and now we have sex every two weeks?! You gotta work very hard, it’s not the same.(woman with breast cancer)

Domain 4: The Medical System

For me, he says whatever it was I wanted to do, he was going to be standing by me and it was exactly that. He’d drive me to all my appointments. Even tonight, he’s sitting [outside] waiting for me.(woman with breast cancer)

Getting the diagnosis is like getting a big slap in the face. And then you’re bombarded with all these booklets and information. And I know for myself—I took care of everything at home and sat and read twenty-four seven (female partner). Yeah, but me, I didn’t want to know nothing about cancer. I had cancer and that’s it.(male with multiple myeloma)

Domain 5: Ongoing Responsibilities

I do recognize that in every household one person will be responsible for specific tasks. However, when one of you is ill, the person who isn’t is going to have to pick up the slack. I found that very frustrating. It’s something as simple as a meal preparation.(woman with breast cancer)

4.2.2. Patient and Partner Affect

Well, the beginning was kind of shock. I think she was more affected than I was. In a way I was kind of accepting it and moving forward and facing whatever obstacles. I was worried more about the effect on her. I could see that although she is very strong, she won’t show too much emotion. I was more worried about her than myself to be honest.(male with head and neck cancer)

4.2.3. Communication and Care for Children

I think that [having children at home] adds another dynamic because [my son is so] small, he’s eight, he doesn’t understand. I’m probably focusing more on his emotional well-being, which is also not the best thing for my husband, but I think [my son] needs more help getting through it because he is so young.(woman with breast cancer)

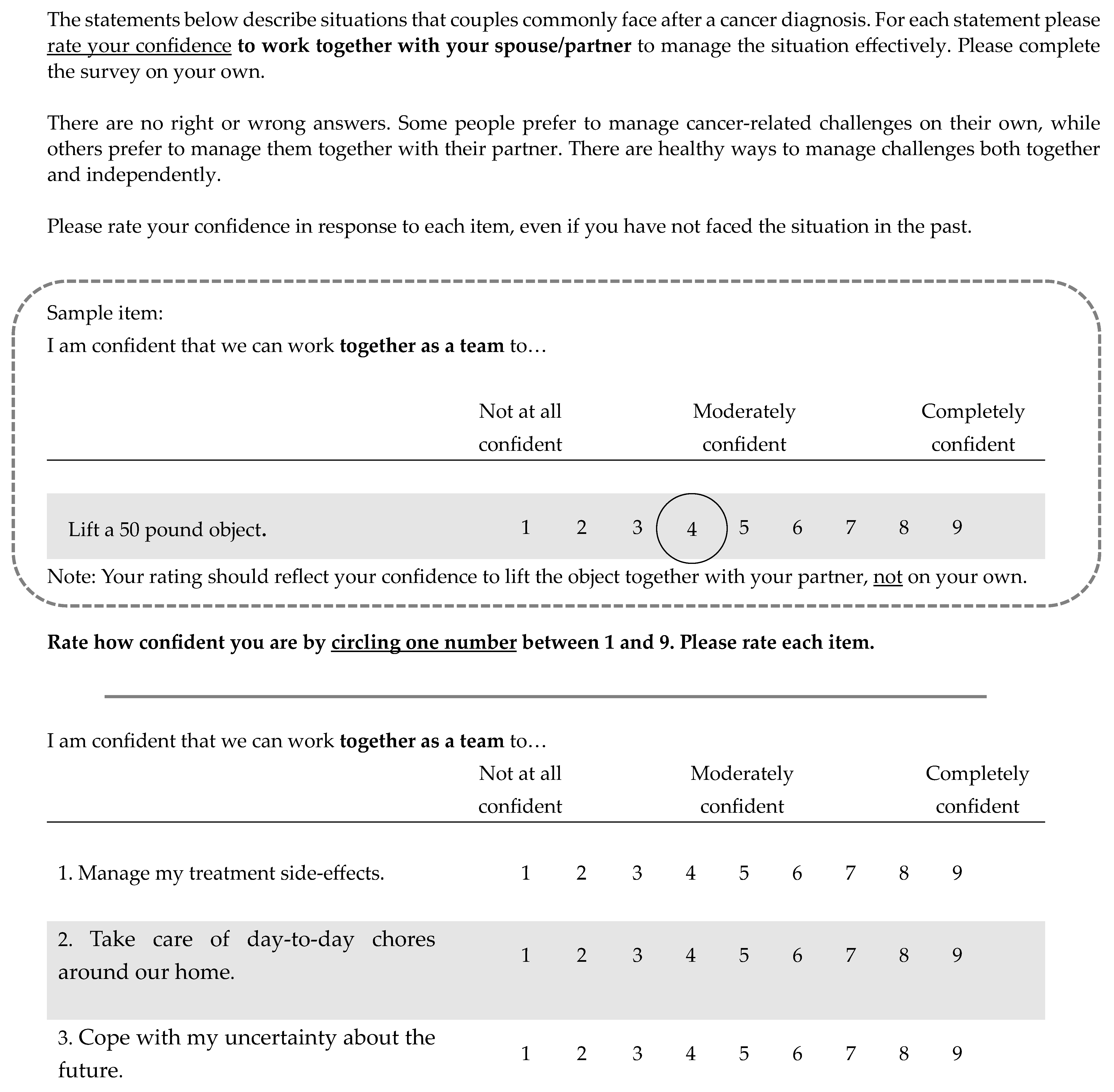

5. Step 2: Materials and Methods for Item Generation and Evaluation

5.1. Participants

5.2. Procedures

5.3. Item Generation and Selection

5.4. Expert Review

5.5. Target Population Review

6. Step 2: Results

6.1. Item Generation and Selection

6.2. Expert Review

6.3. Evaluation by Target Population

7. Discussion

Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Original a | Revised |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deal with your arthritis frustrations? | Deal with your cancer-related frustrations |

| 2 | Help you keep a positive attitude about living with arthritis? | Help you keep a positive attitude throughout your cancer experience? |

| 3 | Rearrange your/her activities when you are having a bad day? | – |

| 4 | Decide how best to tackle your course of treatment? | – |

| 5 | Keep up your activity level? | – |

| 6 | Help you avoid pain? | – |

| 7 | Keep your arthritis from interfering with your sleep | Keep your cancer from interfering with your sleep |

| 8 | Decrease your pain | |

| 9 | Manage your arthritis symptoms? | Manage your cancer symptoms? |

| 10 | Control your pain with methods other than taking medication? | – |

| 11 | Maintain positive attitudes? | – |

| 12 | Encourage each other? | |

| 13 | Deal together with the unpredictable nature of arthritis? | Deal together with the unpredictable nature of cancer? |

| 14 | Work around the difficulties of arthritis? | – |

| 15 | Keep each other’s spirits high | – |

| 16 | Focus together on the good things in your life | – |

References

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing Validity: Basic Issues in Objective Scale Development. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing Validity: New Developments in Creating Objective Measuring Instruments. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, R. Doing Focus Groups; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2007; pp. xvii, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlbach, H.; Brinkworth, M.E. Measure Twice, Cut down Error: A Process for Enhancing the Validity of Survey Scales. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2011, 15, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, D.S.; King, D.W.; King, L.A. Focus Groups in Psychological Assessment: Enhancing Content Validity by Consulting Members of the Target Population. Psychol. Assess. 2004, 16, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado, F.F.R.; Meireles, J.F.F.; Neves, C.M.; Amaral, A.C.S.; Ferreira, M.E.C. Scale Development: Ten Main Limitations and Recommendations to Improve Future Research Practices. Psicol. Reflexao E Crit. Rev. Semest. Dep. Psicol. UFRGS 2017, 30, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjersing, L.; Caplehorn, J.R.; Clausen, T. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Research Instruments: Language, Setting, Time and Statistical Considerations. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterba, K.R.; DeVellis, R.F.; Lewis, M.A.; Baucom, D.H.; Jordan, J.M.; DeVellis, B. Developing and Testing a Measure of Dyadic Efficacy for Married Women with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Their Spouses. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Philip, E.J.; Heitzmann Ruhf, C.A.; Liu, H.; Yang, M.; Conley, C. Self-Efficacy for Coping with Cancer: Revision of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (Version 3.0). Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; Merluzzi, T.; Alivernini, F.; Laurentiis, M.D.; Botti, G.; Giordano, A.A. Meta-Analytic Review of the Relationship of Cancer Coping Self-Efficacy with Distress and Quality of Life. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36800–36811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebdon, M.C.T.; Coombs, L.A.; Reed, P.; Crane, T.E.; Badger, T.A. Self-Efficacy in Caregivers of Adults Diagnosed with Cancer: An Integrative Review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2021, 52, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, W.K. Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Dimensions of Cancer Perception: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Cancer Experience and Efficacy Scale (CEES). Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Lopez, F.G. Cognitive Ties That Bind: A Tripartite View of Efficacy Beliefs in Growth-Promoting Relationships. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 21, 256–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterba, K.R.; Rabius, V.; Carpenter, M.J.; Villars, P.; Wiatrek, D.; McAlister, A. Dyadic Efficacy for Smoking Cessation: Preliminary Assessment of a New Instrument. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011, 13, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badr, H.; Acitelli, L.K. Re-Thinking Dyadic Coping in the Context of Chronic Illness. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revenson, T.A.; Griva, K.; Luszczynska, A.; Morrison, V.; Panagopoulou, E.; Vilchinsky, N.; Hagedoorn, M. Caregiving as a Dyadic Process. In Caregiving in the Illness Context; Revenson, T.A., Griva, K., Luszczynska, A., Morrison, V., Panagopoulou, E., Vilchinsky, N., Hagedoorn, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2016; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.S.; Lee, C.S. The Theory of Dyadic Illness Management. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, K.; Watson, L.E.; Andrade, J.T. Cancer as a “We-Disease”: Examining the Process of Coping From a Relational Perspective. Fam. Syst. Health 2007, 25, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, A.J.; Bartels, L.; Bertschi, I.C.; Mahler, F.; Grotzer, M.; Konrad, D.; Leibundgut, K.; Rössler, J.; Bodenmann, G.; Landolt, M.A. Assessing We-Disease Appraisals of Health Problems: Development and Validation of the We-Disease Questionnaire. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ştefǎnuţ, A.M.; Vintilǎ, M.; Tudorel, O.I. The Relationship of Dyadic Coping With Emotional Functioning and Quality of the Relationship in Couples Facing Cancer-A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 594015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosseau, D.C.; Braeken, J.; Carmack, C.L.; Rosberger, Z.; Körner, A. We Think We Can: Development of the Dyadic Efficacy Scale for Cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2021, 3, e066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergen, K.J. Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. xxix, 418. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P. Focus Group Methodology: Principle and Practice, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Poland, B.D. Handbook of Interview Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To Saturate or Not to Saturate? Questioning Data Saturation as a Useful Concept for Thematic Analysis and Sample-Size Rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devins, G.M. Using the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale to Understand Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronic Disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Nairn, R.C.; Hegde, K.; Martinez Sanchez, M.A.; Dunn, L. Self-Efficacy for Coping with Cancer: Revision of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (Version 2.0). Psychooncology 2001, 10, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Martinez Sanchez, M.A. Assessment of Self-Efficacy and Coping with Cancer: Development and Validation of the Cancer Behavior Inventory. Health Psychol. 1997, 16, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Philip, E.J.; Vachon, D.O.; Heitzmann, C.A. Assessment of Self-Efficacy for Caregiving: The Critical Role of Self-Care in Caregiver Stress and Burden. Palliat. Support. Care 2011, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flesch, R.A. New Readability Yardstick. J. Appl. Psychol. 1948, 32, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kincaid, J.; Fishburne, R.; Rogers, R.; Chissom, B. Derivation Of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count And Flesch Reading Ease Formula) For Navy Enlisted Personnel. Inst. Simul. Train. 1975, 56. Available online: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1055&context=istlibrary (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Posluszny, D.M.; Dougall, A.L.; Johnson, J.T.; Argiris, A.; Ferris, R.L.; Baum, A.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Dew, M.A. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptoms in Newly Diagnosed Head and Neck Cancer Patients and Their Partners. Head Neck 2015, 37, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, B.S.; Miaskowski, C.; Given, B.; Schumacher, K. The Cancer Family Caregiving Experience: An Updated and Expanded Conceptual Model. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2012, 16, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perz, J.; Ussher, J.M.; Gilbert, E. Constructions of Sex and Intimacy after Cancer: Q Methodology Study of People with Cancer, Their Partners, and Health Professionals. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devins, G.M. Illness Intrusiveness and the Psychosocial Impact of Lifestyle Disruptions in Chronic Life-Threatening Disease. Adv. Ren. Replace. Ther. 1994, 1, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Born, A. Optimistic Self-Beliefs: Assessment of General Perceived Self-Efficacy in Thirteen Cultures. World Psychol. 1997, 3, 177–190. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Focus Groups | Pilot Testing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Role | ||||

| Patient | 10 | 59 | 25 | 61 |

| Partner | 7 | 41 | 16 | 39 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 10 | 59 | 17 | 41 |

| Male | 6 | 35 | 22 | 54 |

| Non-binary | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married | 9 | 53 | 34 | 83 |

| Common-law | 6 | 35 | 3 | 7 |

| Cohabiting | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Dating | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Primary school (grade 6) | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Secondary school (grade 11) | 3 | 18 | 12 | 29 |

| Vocational/technical training | 3 | 18 | 10 | 24 |

| University degree | 10 | 59 | 13 | 32 |

| Annual household income (CAD) | ||||

| <$40,000 | 3 | 18 | 7 | 17 |

| >$40,000 to <$60,000 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 15 |

| >$60,000 to <$80,000 | 6 | 35 | 3 | 7 |

| >$80,000 to <$100,000 | - | - | 5 | 12 |

| >$100,000 | 5 | 29 | 11 | 27 |

| Children ≤ 18 years old living in home | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 18 | 6 | 15 |

| No | 6 | 35 | 21 | 51 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 14 | 82 | 36 | 87 |

| Chinese | 1 | 6 | - | - |

| Asian (South/Southeast/West) | - | - | 2 | 5 |

| Self-reported other: Jewish | 2 | 12 | 2 | 5 |

| Cancer type a | ||||

| Breast | 4 | 40 | 10 | 40 |

| Gastrointestinal | - | - | 3 | 12 |

| Blood | 3 | 30 | 1 | 4 |

| Prostate | 1 | 10 | 5 | 20 |

| Gynaecological | - | - | 2 | 8 |

| Head and neck | 2 | 20 | 3 | 12 |

| Other | - | - | 1 | 4 |

| Treatment received a,b | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 6 | 60 | 13 | 52 |

| Radiation therapy | 4 | 40 | 16 | 64 |

| Surgery | 4 | 40 | 8 | 32 |

| Hormonal therapy | 4 | 40 | 5 | 20 |

| Themes and Domains | Example |

|---|---|

| Illness Intrusions | |

| Patient’s physical experience | Treatment/drug effects Pain Lack of energy |

| Social life | Communicating with friends and family Social activities |

| Couple life | Intimacy and sex Time spent together |

| Medical system | Attending appointments Dealing with information |

| Ongoing responsibilities | Work and money Day-to-day chores |

| Emotional responses | |

| Patient affect | Fear cancer will progress Feeling down |

| Partner affect | Fear partner’s cancer will progress Feeling down |

| Communication and care for children | Talking with kids about cancer Keeping up with children’s activities |

| Domain | Item a |

|---|---|

| Physical experience | manage my treatment side effects adjust to changes in my appearance (e.g., weight change, hair loss, scarring) adjust to physical limitations caused by cancer or its treatment do something to help me feel better when I am in pain cope with my tiredness |

| Social life | find help from family, friends, or other patients decide who we share news and updates with adjust our social activities as needed keep family and friends up-to-date about my health |

| Couple life | adjust to changes in our sex life engage in activities we enjoy find ways to feel close to each other resolve disagreements about how to manage cancer-related challenges accept differences in how we cope with cancer-related challenges find time to spend together |

| Medical system | navigate the healthcare system arrange transportation to and from the hospital remain patient when having to wait for results, treatment or appointments manage my schedule of medical appointments cope with a wealth of information understand my treatment plan make sense of the medical information we are given talk openly with my medical team discuss our concerns with my doctor(s) seek help from professional (e.g., nurse, doctor, psychologist, social worker, counsellor) find the support services we need |

| Ongoing responsibilities | manage the financial impact of cancer maintain a sense of normalcy maintain my independence take care of day-to-day chores around our home adjust to changes in our role(s) around our home |

| Emotional response (patient) | make sense of my feelings about cancer cope when I am feeling down maintain my hope manage my fears and worries about cancer cope with my uncertainty about the future cope with my fear that the cancer will become worse deal with my anger or frustration |

| Emotional response (partner) | make sense of my partner’s feelings about cancer cope when my partner is feeling down maintain my partner’s hope manage my partner’s fears and worries about cancer cope with my partner’s uncertainty about the future cope with my partner’s fear that the cancer will become worse deal with my partner’s anger or frustration |

| Communication and care for children | talk with our children about cancer answer our child(ren)’s questions about cancer take care of our child(ren)’s day-to-day needs keep up with our child(ren)’s social and/or leisure activities find support with childcare when needed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brosseau, D.C.; Peláez, S.; Ananng, B.; Körner, A. Contextualizing Measurement: Establishing a Construct and Content Foundation for the Assessment of Cancer-Related Dyadic Efficacy. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 4568-4588. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31080341

Brosseau DC, Peláez S, Ananng B, Körner A. Contextualizing Measurement: Establishing a Construct and Content Foundation for the Assessment of Cancer-Related Dyadic Efficacy. Current Oncology. 2024; 31(8):4568-4588. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31080341

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrosseau, Danielle C., Sandra Peláez, Bethsheba Ananng, and Annett Körner. 2024. "Contextualizing Measurement: Establishing a Construct and Content Foundation for the Assessment of Cancer-Related Dyadic Efficacy" Current Oncology 31, no. 8: 4568-4588. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31080341

APA StyleBrosseau, D. C., Peláez, S., Ananng, B., & Körner, A. (2024). Contextualizing Measurement: Establishing a Construct and Content Foundation for the Assessment of Cancer-Related Dyadic Efficacy. Current Oncology, 31(8), 4568-4588. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31080341