Caregiving and Shared Decision Making in Breast and Prostate Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

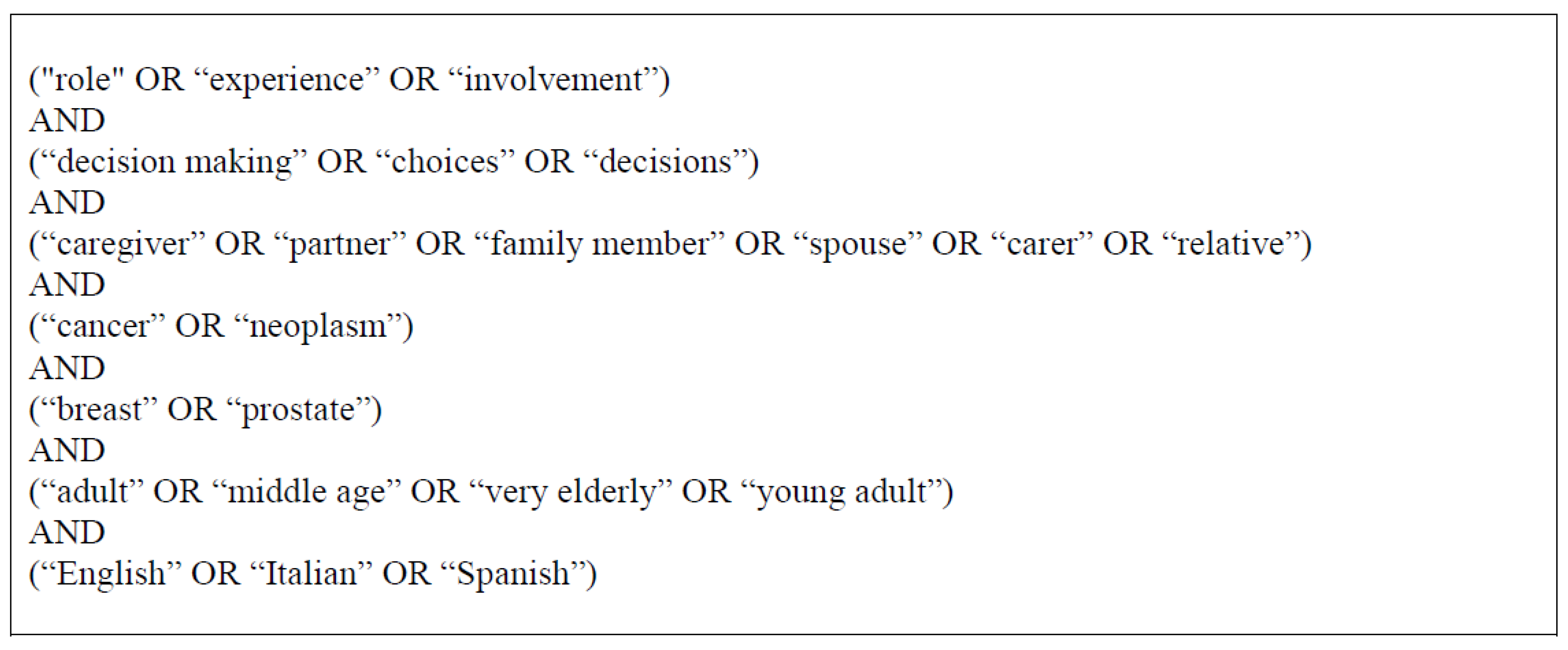

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

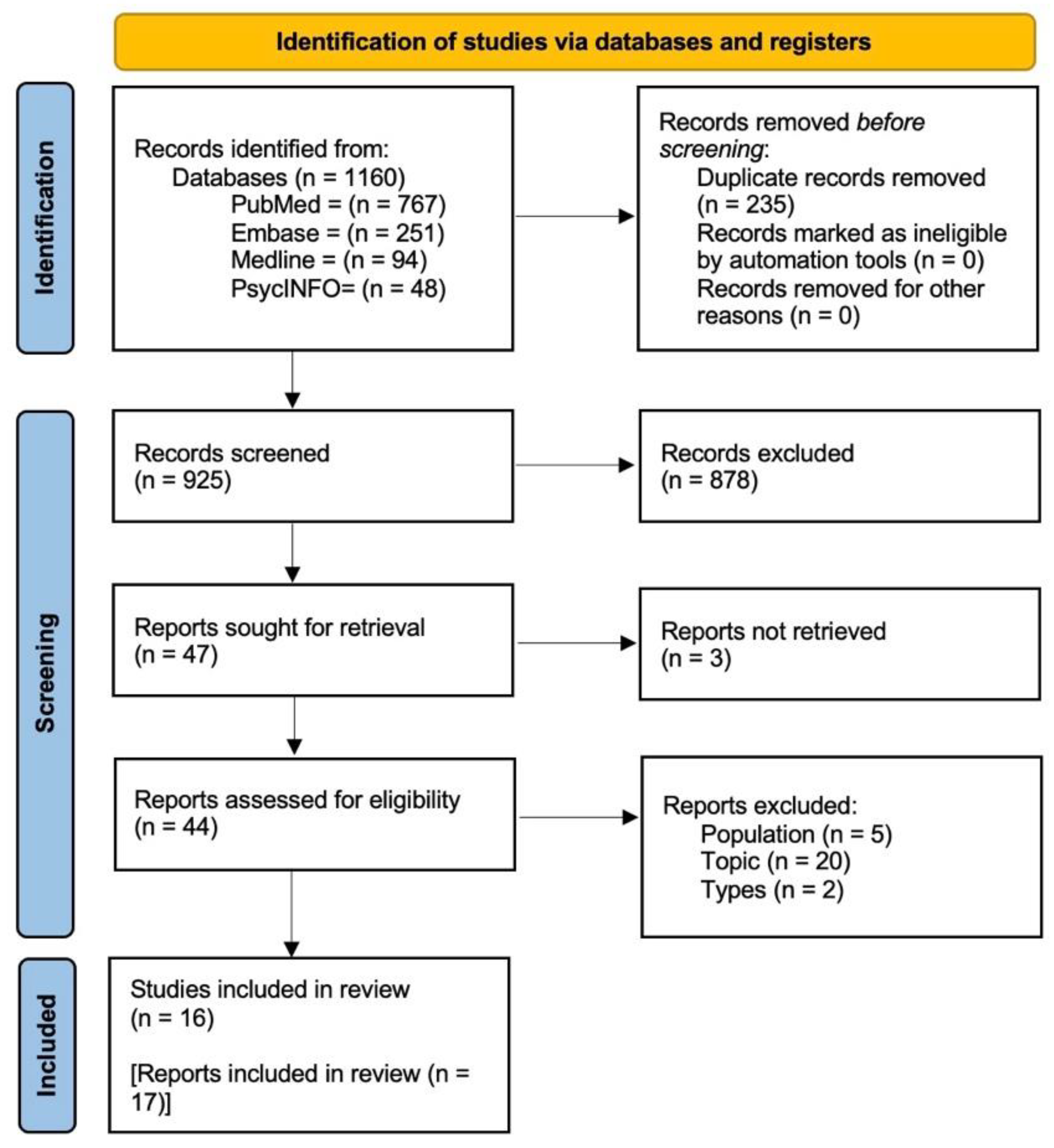

2.3. Screening Procedure

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Selected Reports

3.2. Shared Decision-Making between Patients and Caregivers

3.3. Psychological Impact of Cancer on Patient-Caregiver Dyads

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Strategy for Scientific Literature | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search Engine: | Search String: | Hits | Relevant a | Included b |

| Pubmed | (“role” OR “experience” OR “involvement”) AND (“decision making” OR “choices” OR “decisions”) AND (“caregiver” OR “partner” OR “family member” OR “spouse” OR “carer” OR “relative”) AND (“cancer” OR “neoplasm”) AND (“breast” OR “prostate”) AND (“adult” OR “middle age” OR “very elderly” OR “young adult”) AND (“english” OR “italian” OR “Spanish”) | 767 | 66 | 15 |

| Embase | (‘role’/exp OR role OR ‘experience’/exp OR experience OR ‘involvement’/exp OR involvement) AND ((‘decision’/exp OR decision) AND making OR ‘choice’/exp OR choice OR ‘decision’/exp OR decision) AND ((‘caregiver’/exp OR caregiver OR ‘partner’/exp OR partner OR ‘family’/exp OR family) AND member OR ‘spouse’/exp OR spouse OR ‘carer’/exp OR carer OR ‘relative’/exp OR relative) AND (‘cancer’/exp OR cancer OR ‘neoplasm’/exp OR neoplasm) AND (‘breast’/exp OR breast OR ‘prostate’/exp OR prostate)) AND ([adult]/lim OR [aged]/lim OR [middle aged]/lim OR [very elderly]/lim OR [young adult]/lim) AND ([english]/lim OR [italian]/lim OR [spanish]/lim)) AND [embase]/lim | 251 | 76 | 2 |

| 1. role.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] (103414) 2 experience.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] (26523) 3 involvement.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] (14510) 20 4 and 8 and 15 and 16 and 19 (8) | ||||

| PsycINFO | 1 ((role or experience or involvement) and (decision making or choices or decisions) and (caregiver or partner or family member or spouse or carer or relative) and (cancer or neoplasm) and (breast or prostate)).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, Search Strategy of contents, key concepts, original title, tests and measures, mesh] (65) 2 limit 1 to (adulthood <18+ years> and (“300 adulthood <age 18 yrs and older > “ or 320 young adulthood <age 18 to 29 yrs> or 360 middle age <age 40 to 64 yrs > ) and (english or italian or spanish)) (48) | 48 | 7 | 0 |

| Subtotal | 1160 | 150 | 17 | |

| Duplicates | 239 | |||

| Excluded due to missing data | 3 | |||

| Total | 918 | 150 | 17 | |

References

- Woźniak, K.; Iżycki, D. Cancer: A family at risk. Menopausal Rev. 2014, 4, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minuchin, S. Families and Family Therapy; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Given, B.A. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors. Cancer 2008, 112, 2556–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northouse, L.L.; Mood, D.W.; Schafenacker, A.; Montie, J.E.; Sandler, H.M.; Forman, J.D.; Hussain, M.; Pienta, K.J.; Smith, D.C.; Kershaw, T. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer 2007, 110, 2809–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, C.; Badger, T.A. Psychological distress in different social network members of breast and prostate cancer survivors. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saita, E.; Acquati, C.; Molgora, S. Promoting Patient and Caregiver Engagement to Care in Cancer. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorros, S.M.; Card, N.A.; Segrin, C.; Badger, T.A. Interdependence in women with breast cancer and their partners: An interindividual model of distress. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manne, S.; Sherman, M.; Ross, S.; Ostroff, J.; Heyman, R.E.; Fox, K. Couples’ Support-Related Communication, Psychological Distress, and Relationship Satisfaction Among Women With Early Stage Breast Cancer. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, P.A. Psychological and social aspects of breast cancer. Oncology 2008, 22, 642–646, 650; discussion 650, 653. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri, S.; Marton, G.; Vergani, L.; Cutica, I.; Gorini, A.; Spinella, F.; Pravettoni, G. Genetic Testing Consumers in Italy: A Preliminary Investigation of the Socio-Demographic Profile, Health-Related Habits, and Decision Purposes. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, S.; Durosini, I.; Cutica, I.; Cincidda, C.; Spinella, F.; Baldi, M.; Gorini, A.; Pravettoni, G. Health orientation and individual tendencies of a sample of Italian genetic testing consumers. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020, 8, e1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincidda, C.; Oliveri, S.; Sanchini, V.; Pravettoni, G. The role of caregivers in the clinical pathway of patients newly diagnosed with breast and prostate cancer: A study protocol. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 962634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincidda, C.; Pizzoli, S.F.M.; Pravettoni, G. Remote Psychological Interventions for Fear of Cancer Recurrence: Scoping Review. JMIR Cancer 2022, 8, e29745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, A.; Sonavane, S.; Mehta, J. Psychological aspects of prostate cancer: A clinical review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012, 15, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzzatti, B.; Bomben, F.; Flaiban, C.; Piccinin, M.; Annunziata, M.A. Quality of life and psychological distress during cancer: A prospective observational study involving young breast cancer female patients. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.; Clarke, V. The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis on families: The influence of family functioning and patients’ illness characteristics on depression and anxiety. Psychooncology 2004, 13, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, L.J.; Humphris, G.M.; Macfarlane, G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenberg, U.; Ruland, C.M.; Miaskowski, C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology 2010, 19, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandgren, A.K.; Mullens, A.B.; Erickson, S.C.; Romanek, K.M.; McCaul, K.D. Confidant and breast cancer patient reports of quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, S.; Cincidda, C.; Ongaro, G.; Cutica, I.; Gorini, A.; Spinella, F.; Fiorentino, F.; Baldi, M.; Pravettoni, G. What people really change after genetic testing (GT) performed in private labs: Results from an Italian study. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waks, A.G.; Winer, E.P. Breast Cancer Treatment. JAMA 2019, 321, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherr, K.; Delaney, R.K.; Ubel, P.; Kahn, V.C.; Hamstra, D.; Wei, J.T.; Fagerlin, A. Preparing Patients with Early Stage Prostate Cancer to Participate in Clinical Appointments Using a Shared Decision Making Training Video. Med. Decis. Mak. 2022, 42, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaboldi, P.; Oliveri, S.; Vergani, L.; Marton, G.; Guiddi, P.; Busacchio, D.; Didier, F.; Pravettoni, G. The clinical-care focused psychological interview (CLiC): A structured tool for the assessment of cancer patients’ needs. Ecancermedicalscience 2020, 14, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravettoni, G.; Cutica, I.; Righetti, S.; Mazzocco, K. Decisions and involvement of cancer patient survivors: A moral imperative. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2016, 8, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, G.; Pizzoli, S.F.M.; Vergani, L.; Mazzocco, K.; Monzani, D.; Bailo, L.; Pancani, L.; Pravettoni, G. Patients’ health locus of control and preferences about the role that they want to play in the medical decision-making process. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, G.A.; Oliveri, S.; Cincidda, C.; Guiddi, P.; Pravettoni, G. Exploring public attitude toward biofeedback technologies: Knowledge, preferences and personality tendencies. J. Public Health Res. 2020, 9, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ejem, D.; Wells, R.; Barnato, A.E.; Taylor, R.A.; Rocque, G.B.; Turkman, Y.E.; Kenny, M.; Ivankova, N.V.; Bakitas, M.A.; et al. How family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer assist with upstream healthcare decision-making: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Butow, P.; Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Entwistle, V.; Epstein, R.; Juraskova, I. The TRIO Framework: Conceptual insights into family caregiver involvement and influence throughout cancer treatment decision-making. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 2035–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullrich, A.; Theochari, M.; Bergelt, C.; Marx, G.; Woellert, K.; Bokemeyer, C.; Oechsle, K. Ethical challenges in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer–a qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Vírseda, C.; de Maeseneer, Y.; Gastmans, C. Relational autonomy in end-of-life care ethics: A contextualized approach to real-life complexities. BMC Med. Ethics 2020, 21, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Piccolo, L.; Goss, C.; Bottacini, A.; Rigoni, V.; Mazzi, M.; Deledda, G.; Ballarin, M.; Molino, A.; Fiorio, E.; Zimmermann, C. Asking questions during breast cancer consultations: Does being alone or being accompanied make a difference? Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Butow, P.; Bu, S.; Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Fisher, A.; Juraskova, I. Family involvement in cancer treatment decision-making: A qualitative study of patient, family, and clinician attitudes and experiences. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; McCannon, J.; Greer, J.A.; Jackson, V.A.; Rn, P.O.; Pirl, W.; Lynch, T.J.; Billings, J.A. Aggressiveness of care in a prospective cohort of patients with advanced NSCLC. Cancer 2008, 113, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBenske, L.L.; Gustafson, D.H.; Shaw, B.R.; Cleary, J.F. Web-Based Cancer Communication and Decision Making Systems: Connecting Patients, Caregivers, and Clinicians for Improved Health Outcomes. Med. Decis. Mak. 2010, 30, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBenske, L.L.; Chih, M.-Y.; Gustafson, D.H.; Dinauer, S.; Cleary, J.F. Caregivers’ participation in the oncology clinic visit mediates the relationship between their information competence and their need fulfillment and clinic visit satisfaction. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 81, S94–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, E.A.G.; DeFuentes-Merillas, L.; de Weert, G.H.; Sensky, T.; van der Staak, C.P.F.; de Jong, C.A.J. Systematic Review of the Effects of Shared Decision-Making on Patient Satisfaction, Treatment Adherence and Health Status. Psychother. Psychosom. 2008, 77, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, G.S.; Landrum, M.B.; Arora, N.K.; Ganz, P.A.; van Ryn, M.; Weeks, J.C.; Mack, J.W.; Keating, N.L. The role of families in decisions regarding cancer treatments. Cancer 2015, 121, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Butow, P.; Bu, S.; Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Lam, W.; Jansen, J.; McCaffery, K.; Shepherd, H.; Tattersall, M.; et al. Physician–patient–companion communication and decision-making: A systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 91, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longacre, M.L.; Miller, M.F.; Golant, M.; Zaleta, A.K.; Buzaglo, J.S. Care and Treatment Decisions in Cancer: The Role of the Family Caregiver. J. Oncol. Navig. Surviv. 2018, 9, 354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Longacre, M.L.; Applebaum, A.J.; Buzaglo, J.S.; Miller, M.F.; Golant, M.; Rowland, J.H.; Given, B.; Dockham, B.; Northouse, L. Reducing informal caregiver burden in cancer: Evidence-based programs in practice. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, C.M.; Wallner, L.P.; Abrahamse, P.H.; Janz, N.K.; Katz, S.J.; Hawley, S.T. Understanding the engagement of key decision support persons in patient decision making around breast cancer treatment. Cancer 2019, 125, 1709–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccio, F.; Renzi, C.; Crico, C.; Kazantzaki, E.; Kondylakis, H.; Koumakis, L.; Marias, K.; Pravettoni, G. Development of an eHealth tool for cancer patients: Monitoring psychoemotional aspects with the family resilience (FaRe) questionnaire. Ecancermedicalscience 2018, 12, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrocchi, S.; Marzorati, C.; Masiero, M. “We-Diseases” and Dyadic Decision-Making Processes: A Critical Perspective. Public Health Genom. 2022, 25, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.L. Family Communication About Cancer Treatment Decision Making A Description of the DECIDE Typology. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2014, 38, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkman, B.L.; Luttik, M.L.; van der Wal-Huisman, H.; Paans, W.; van Leeuwen, B.L. Factors influencing family involvement in treatment decision-making for older patients with cancer: A scoping review. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraun, L.; de Vliegher, K.; Vandamme, M.; Holtzheimer, E.; Ellen, M.; van Achterberg, T. Older peoples’ and informal caregivers’ experiences, views, and needs in transitional care decision-making: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 134, 104303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, J.B.; Brown, J.C.; Okamoto, I.; Addington-Hall, J.M. The Effectiveness of Patient-Family Carer (Couple) Intervention for the Management of Symptoms and Other Health-Related Problems in People Affected by Cancer: A Systematic Literature Search and Narrative Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2012, 43, 111–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, L.L.; Katapodi, M.C.; Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Mood, D.W. Interventions with Family Caregivers of Cancer Patients: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010, 60, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symmons, S.M.; Ryan, K.; Aoun, S.M.; E Selman, L.; Davies, A.N.; Cornally, N.; Lombard, J.; McQuilllan, R.; Guerin, S.; O’Leary, N.; et al. Decision-making in palliative care: Patient and family caregiver concordance and discordance—Systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsky, J.A.; Steinhauser, K.E.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Bloom, N.; Lyna, P.R.; Riley, J.; Pollak, K.I. Triadic agreement about advanced cancer treatment decisions: Perceptions among patients, families, and oncologists. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, B.J.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Gleave, M.E.; Degner, L.F. Provision of individualized information to men and their partners to facilitate treatment decision making in prostate cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2003, 30, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, B.J.; Gleave, M.E.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Degner, L.F.; Hoffart, D.; Berkowitz, J. Assessing information and decision preferences of men with prostate cancer and their partners. Cancer Nurs. 2002, 25, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbar, R.; Gilbar, O. The medical decision-making process and the family: The case of breast cancer patients and their husbands. Bioethics 2009, 23, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, N.T.; Kuo, Y.L.; Lai, H.W.; Ko, N.Y.; Fang, S.Y. The influence of partner involvement in the decision-making process on body image and decision regret among women receiving breast reconstruction. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, U.; Babayan, R.K. A pilot study to determine support during the pre-treatment phase of early prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2005, 14, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docherty, A.; Cannon, P.; Brothwell, P.D.; Symons, M.; Pct, B. The Impact of Inadequate Knowledge on Patient and Spouse Experience of Prostate Cancer Cancer nurse specialist Experience Knowledge Patient preference Prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2007, 30, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasse, L.; Flahault, C.; Vioulac, C.; Lamore, K.; Van Wersch, A.; Quintard, B.; Untas, A. The decision-making process for breast reconstruction after cancer surgery: Representations of heterosexual couples in long-standing relationships. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.E.; Fitch, M.I.; Phillips, C.; Labrecque, M.; Klotz, L. Presurgery experiences of prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer Pract. 1999, 7, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamore, K.; Vioulac, C.; Fasse, L.; Flahault, C.; Quintard, B.; Untas, A. Couples’ Experience of the Decision-Making Process in Breast Reconstruction after Breast Cancer: A Lexical Analysis of Their Discourse. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, Y.-C.L.; McFall, S.L.; Byrd, T.L.; Volk, R.J.; Cantor, S.B.; Kuban, D.A.; Mullen, P.D. Is “Active Surveillance” an Acceptable Alternative?: A Qualitative Study of Couples’ Decision Making about Early-Stage, Localized Prostate Cancer. Narrat. Inq. Bioeth. 2016, 6, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaring, J.M.; Larkin, M.; Shaw, R.; Flowers, P. Renegotiating sexual intimacy in the context of altered embodiment: The experiences of women with breast cancer and their male partners following mastectomy and reconstruction. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliski, S.L.; Heilemann, M.V.; McCorkle, R. From “Death Sentence” to “Good Cancer”: Couples’ Transformation of a Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Nurs. Res. 2002, 51, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.; Bennett, P.; Rance, J. The experiences of giving and receiving social support for men with localised prostate cancer and their partners. Ecancermedicalscience 2019, 13, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, C.; Dryden, T.; Hyatt, A.; Brooker, J.; Burney, S.; Wootten, A.C.; White, A.; Frydenberg, M.; Murphy, D.; Williams, S.; et al. “What is this active surveillance thing?” Men’s and partners’ reactions to treatment decision making for prostate cancer when active surveillance is the recommended treatment option. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, S.H. Considering racial and ethnic preferences in communication and interactions among the patient, family member, and physician following diagnosis of localized prostate cancer: Study of a US population. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2011, 4, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bahri, A.; Al-Moundhri, M.; Al-Mandhari, Z.; Al-Azri, M. Role of the family in Treatment Decision-Making process for Omani women diagnosed with breast cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cincidda, C.; Pizzoli, S.F.M.; Oliveri, S.; Pravettoni, G. Regulation strategies during COVID-19 quarantine: The mediating effect of worry on the links between coping strategies and anxiety. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 72, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongaro, G.; Cincidda, C.; Sebri, V.; Savioni, L.; Triberti, S.; Ferrucci, R.; Poletti, B.; Dell’Osso, B.; Pravettoni, G. A 6-Month Follow-Up Study on Worry and Its Impact on Well-Being During the First Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic in an Italian Sample. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Included | Excluded | |

|---|---|---|

| Topic | Caregiver involvement in breast and prostate cancer patients’ decision-making along their cancer care path. | |

| Research domain | Application to the specific field of clinical psychology (broadly understood). | |

| Population | Competent breast or prostate cancer patients and their caregivers (e.g., parents, partners/spouses, sons, other loved ones, or close friends). | Breast or prostate cancer patients and/or caregivers that are not competent due to cognitive impairment or coma. Patients with other cancers than breast and prostate. |

| Language | Publications in English, Italian, or Spanish. | Publications in other languages than English, Italian, and Spanish. |

| Types (research methodology) | Publications are one of the following types of literature: (a) qualitative literature (e.g., in-depth interview, semi-structured interview, focus group); (b) quantitative literature (e.g., survey, standardized questionnaire); (c) mixed methods literature. | Editorials, conferences, commentaries, book chapters, guidelines, and literature reviews |

| Authors, Year, Country | Data Collection Technique | Samples Time Points | Measurement Time-Point and Treatment | Significant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davison et al. 2003 Canada [53] | Control Preferences Scale (CPS) State Anxiety Inventory (STAI–Y Form) The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). | 148 participants: 74 PCp (μage = 62.2; 41–79) 74 Partners (μage = 58.1; 29–76) | At the time of diagnosis and 4 months later Treatment = 75% radical prostatectomy | Shared decision-making Most patients wanted to share the decision with their partner or to decide after consulting them and assumed a more active role in TDM than originally intended Almost all the partners preferred to play either a collaborative or passive role in the TDM and assumed a more passive role in the TDM than originally preferred. Psychological impact Patient and caregiver levels of psychological distress did not influence the role that they assumed vs. the roles they originally had preferred in TDM. |

| Davison et al. 2002 Canada [54] | Control Preferences Scale (CPS) regarding their physician and their partner Information Survey Questionnaire. | 160 participants 80 PCp (μage = 61.3; 41–79) 80 caregivers (Partners) (μage = 57.2; 29–76) | After their initial treatment consultation Treatment = Not yet decided | Shared decision-making Most patients preferred to play either an active or a collaborative role in TDM. Partners preferred to play a collaborative role or passive role in TDM. |

| Gilbar and Gilbar 2009 Israel [55] | doctor–patient/spouse relationships decision making regarding medical treatment | 114 participants n = 57 BCp (μage = 53; 34–69) n = 57 (husband) (μage = 54.42; 37–75) | 3 to 12 months after diagnosis Treatment = under medical treatment | Shared decision-making Almost all the patients preferred to decide by themselves, but their decision should be in accord with that of their husband’s. Most of the patients thought that their husbands should participate in the TDM. Significant high correlation between patients and their husbands regarding participants in the decision-making, and who the important parties are in the decision-making process. |

| Kuo et al. 2019 China [56] | The Involvement in the Breast Reconstruction Decision-Making Process Scale The Body Image Scale The Decision Regret Scale | 210 participants n = 105 BCp (μage = 48.3; 32–64) n = 105 (Partner) (μage = 50.59; 32–74) | 16 months since breast reconstruction Treatment = Mastectomy | Shared decision-making Patients’ and partners’ decision involvements were significantly correlated. The dyadic decision involvement was significantly inversely related to decision regret |

| Veenstra et al. 2019 USA [41] | Questionnaire on decision support persons concerning 3 domains of engagement in decision making. | 2406 participants n = 1203 BCp (μage = /) n = 1203 (43% Husband/Partner, 23% daughter. 23% other family members, 10% friends or other non-family members) (μage = /) | 7 months after their diagnosis Treatment =31% CT, 50% RT, 62% lumpectomy, 38% mastectomy | Shared decision-making Partners were significantly more engaged than other types of decision support persons. Having a highly informed decision support person was associated with higher odds of greater patient-reported subjective decision quality Having a highly aware decision support person was associated with higher odds of a more deliberative decision. |

| Authors, Year, Country | Data Collection Technique | Sample Time Points | Measurement Time-Point and Treatment | Significant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boehmer and Babayanc, 2005 USA [57] | Face to face or telephone interview | 39 participants: 21 PCp (μage = 59.57; 37–70) 18 Caregiver = 14 F (12 wife, 1 partner, 1 daughter, 1 relative, 3 friends) (μage = 55.28; 39–70) | Patients had decided on a treatment modality, but had not yet started Treatment = 66.7% Surgery, 19% Brachytherapy, 14.29% RT | Shared decision-making Men received from their partners emotional and informational support (emerged as being significant during the pre-treatment phase) and involved them in medical appointments Psychological impact Spousal support depended on the diagnosed partner’s willingness to accept emotional and/or informational support. |

| Docherty et al., 2007 UK [58] | Focus group | 12 participants 9 PCp (μage = 71; 54–79) 3 Partners (μage = 71; 54–79) | Time since treatment ranged from 6 months to 5 years Treatment = RT, orchidectomy, and HT | Shared decision-making Patients made their decision using their spouse’s support (often wife contacted the staff to gain information). Couples appreciated being involved in decisions and faced it as a team |

| Fasse et al., 2007 France [59] | Semi-directive interviews | 18 participants n = 9 BCp (μage = 54; 33–66) n = 9 Partners (μage = 59; 40–76) | The time from diagnosis varied between 2 and 8 years Treatment = mastectomy | Shared decision-making The DM on BR did not entirely depend on patients’ and caregivers’ wishes and expectations. Some women and a few partners argued that the TDM was something decided by someone else, not necessarily causing distress or upset for the participants. |

| Gray et al., 1999 Canada [60] | Interview | 68 participants n= 34 PCp (μage = 60.6; 50–68) n = 34 Partners (μage = 57; 42–72) | Waiting for surgery / | Shared decision-making Some couples took time to make decisions, investigating together different conventional and unconventional options along the way. Psychological impact The PC diagnosis came as a shock for all the couples, experiencing it as a shared one. It was frequently accompanied with a partial retreat from normal life. The absence of any sense of reconnection between the partners seemed to create dissonance in the relationship. Sometimes couples felt it was important to discuss what scared them and how they felt, and then to reassure each other |

| Lamore et al., 2020 France [61] | Semi-structured interview | 18 participants n = 9 BCp (μage = 54; 39–66) n = 9 Partner (μage = 59; 40–76) | After mastectomy Treatment = Surgery | Shared decision-making The DM for BR seems linked to the family history of cancer, and temporality is important. Couples needed to talk together, or with other people about the mastectomy and the BR. Psychological impact Participants were concerned about treatments and their effects on their relationship. |

| Le et al., 2016 USA [62] | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 30 participants n = 15 PCp (μage = 61.5; 49–72) n = 15 Wife (μage = 59.3; 45–71) | Within 6–18 months of the decision Treatment = 10 AS, 3 RT, 2 Surgery | Shared decision-making Most of the couples perceived the DM to be collaborative. PCp shared responsibility and partners reported that patients made the decision after considering their point of view. Men who chose AS were more likely to make the decision on their own than those who chose active treatment. Psychological impact Couples reported high dyadic adjustment, finding their marital interactions satisfying and their relationships cohesive All couples described similar sequences of a highly emotional initial reaction and desire to be rid of the cancer, information seeking, and decision making. |

| Loaring et al., 2015 UK [63] | Interviews | 8 participants n = 4 BCp (μage = /; 37–55) n = 4 Partners (μage = /; 37–55) | At least 6 months post treatment Treatment = Mastectomy | Shared decision-making Patients were seen by men as decision-makers. Partners wanted to be part of TDM, but they put their wives’ needs or preferences first and supported whatever decision they made. Husbands were active and involved in TDM. Psychological impact There was a sense of “being together” and having a shared understanding of cancer. The diagnosis and the decisions regarding treatment could be overwhelming. Patients were concerned about their bodies and they did not believe that their husbands could find them attractive, even if partners found their wives as attractive as they did before breast cancer. |

| Maliski et al., 2002 USA [64] | Interview | 40 participants n = 20 PCp (μage = 58.9; 51–71) n = 20 Wife (μage = 54.3; 28–70) | Between 3- and 11-months post prostatectomy Treatment = Prostatectomy | Shared decision-making Patients made their decision searching information on outcomes and complications of each treatment. The final choice of treatment was made by the PCp, even if they discussed treatment with their wives. Psychological impact The wives’ goal was to support their husbands’ decision, but they were concerned about their ability to do so. The diagnosis of PC represented a loss of control. Cancer was a shock, trauma, disbelief, and couples were scared. |

| Nelson et a., 2019 USA [65] | Semi-structured interviews | 36 participants n = 18 PCp (μage = 11.1% 50–59, 50% 60–69, 37.5% 70–70; /) n = 18 Partners (μage = 44.4% 50–59, 44.4% 60–69, 11.1% 70–70; /) | At 3 time-points following diagnosis Treatment = Active surveillance 5 Radical prostatectomy 6 Hormone/radiotherapy 7 | Shared decision-making Men on AS preferred not to discuss their cancer once treatment decisions had been made. Psychological impact Throughout the illness trajectory, partners provided emotional, instrumental, and appraisal support and they reported being happy to provide support. Partners helped patients to deal with treatment-related side effects (sexual dysfunction). Men receiving treatment spoke favorably about the support they had received from their partner. Some partners mentioned a perception that much of the support on offer was superficial and found it difficult to accept support from their wider network. |

| O’Callaghan et al., 2014 Australia [66] | Interview | 35 participants n = 21 PCp (μage 4.76% ≤50, 28.57% 51–60, 52.38% 61–70, 14.29 >71; /) n = 14 Partners (μage = 28.57% ≤50, 14.29% 51–60, 50% 61–70, 7.14% >71; /) | / Treatment = 11 still on AS, 7 RP after ≥3 months on AS, 1 EBRT after ≥3 months on AS, 1 BT after ≥3 months on AS, 1 RP immediately after diagnosis | Shared decision-making Men’s TDM were informed by perspectives from medical staff and caregivers and affected by their emotional reactions, cancer-related memories, and lifestyle factors. Partners supported men’s final decisions, who usually felt the support provided by caregivers. Psychological impact Men and partners’ strategies for coping: positive self-talk, living as normally as possible, distraction, thinking of PC survivors, rationalizing that one could die of something else, hope for new PC treatments, denial, educating others about PC, acquiring information, continuing a healthy lifestyle, seeking reassurance, and humor. |

| Rim et al., 2011 USA [67] | Focus Group | 433 participants n = 240 PCp (μage = less than 60–more than 70) n = 193 Caregivers (93% Wife/Partner, 5% Daughter/Son, 3% Other/Unknown) (μage = less than 60- more than 70) | At diagnosis / | Shared decision-making Some patients found partners’ preference for a particular treatment “very important” Family members reported discussing treatment options with patients “very often”. Nearly all family members “strongly agreed” their role was to listen and provide emotional support, to help obtain information about cancer and treatment options, to arrange meetings with physicians and other health professionals, and to help patients make a treatment decision. |

| Authors, Year, Country | Data Collection Technique | Sample Time Points | Measurement Time-Point and Treatment | Significant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Bahri et al., 2019 Oman [68] | CanCORS questionnaires | 158 participants: 79 BCp (μage = 45; 26–75) 79 Caregiver (39.2 % spouses, 17.7% siblings, 34.2% parents, 8.9% others) (μage = 36; 18–65) | Two years after treatment Treatment = 59.5% surgery; 40.5% other treatments | Shared decision-making More family members than the patients reported equally-shared the TDM and high levels of family control in the TDM. Most of the BC patients shared the TDM with more than one family member. Most patients reported that their families usually come together to discuss and finalize the TDM, which occurred when there was full agreement between their family members. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cincidda, C.; Pizzoli, S.F.M.; Ongaro, G.; Oliveri, S.; Pravettoni, G. Caregiving and Shared Decision Making in Breast and Prostate Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 803-823. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30010061

Cincidda C, Pizzoli SFM, Ongaro G, Oliveri S, Pravettoni G. Caregiving and Shared Decision Making in Breast and Prostate Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(1):803-823. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleCincidda, Clizia, Silvia Francesca Maria Pizzoli, Giulia Ongaro, Serena Oliveri, and Gabriella Pravettoni. 2023. "Caregiving and Shared Decision Making in Breast and Prostate Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review" Current Oncology 30, no. 1: 803-823. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30010061

APA StyleCincidda, C., Pizzoli, S. F. M., Ongaro, G., Oliveri, S., & Pravettoni, G. (2023). Caregiving and Shared Decision Making in Breast and Prostate Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Current Oncology, 30(1), 803-823. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30010061